Written and illustrated by Violetta Zein

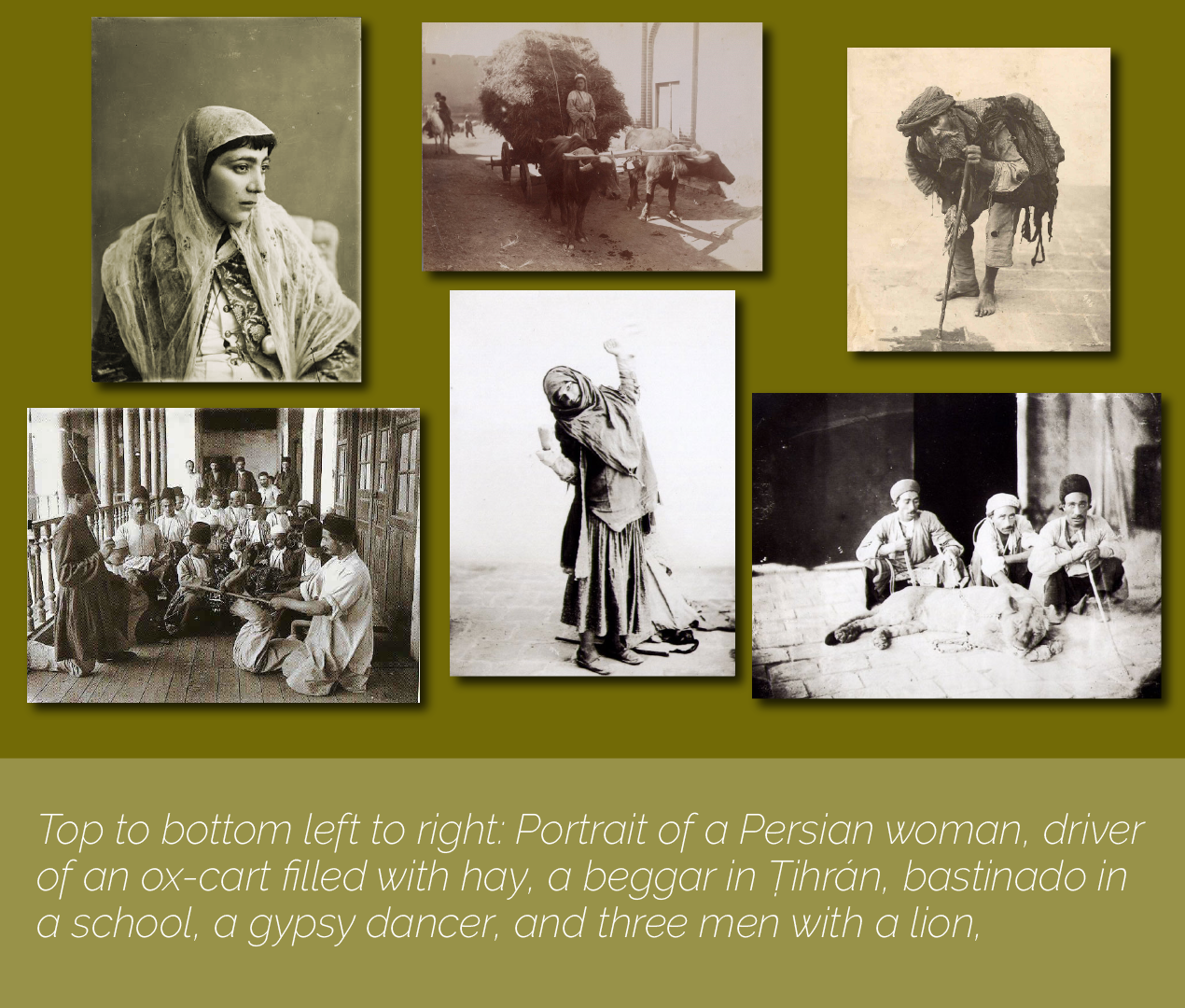

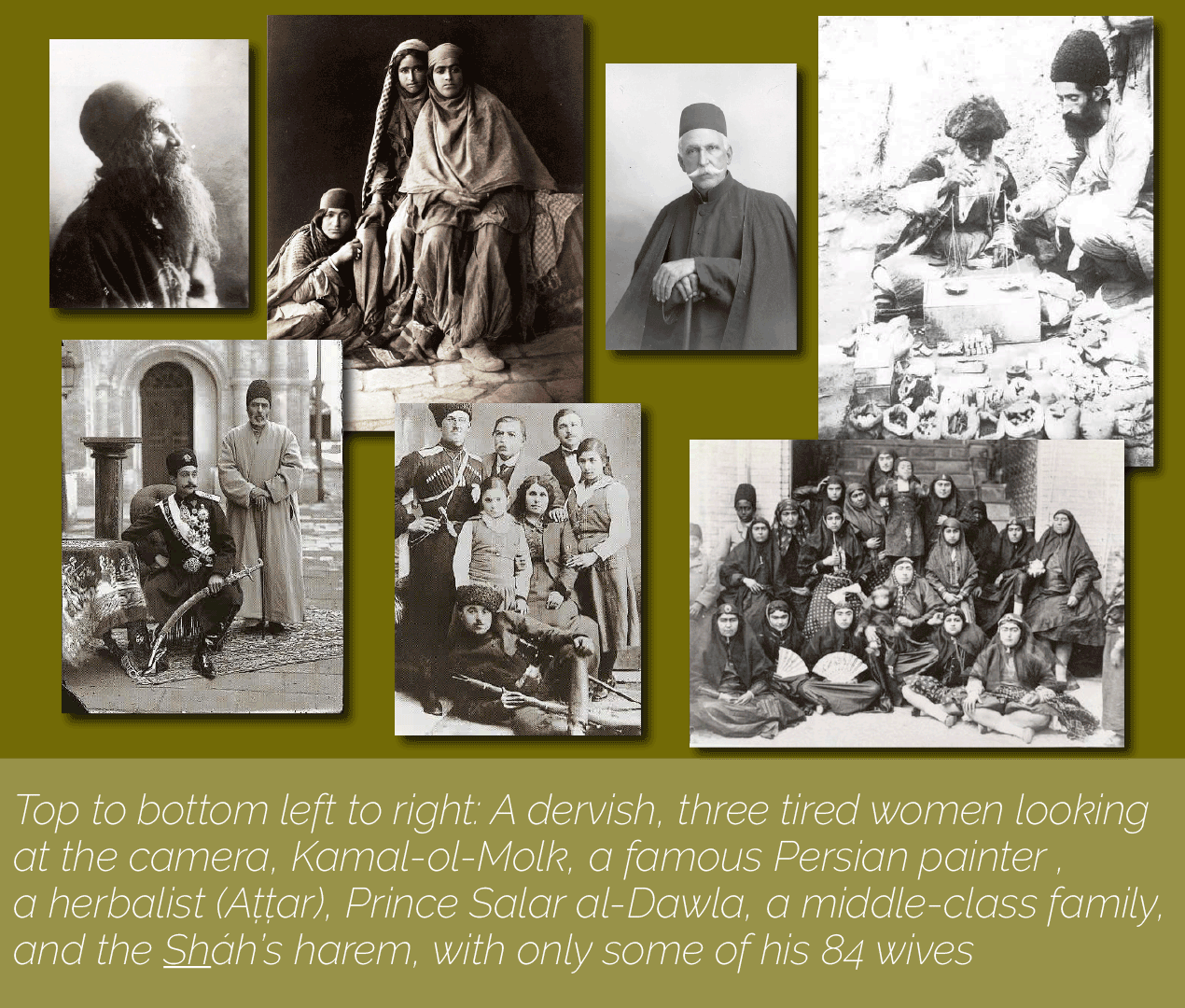

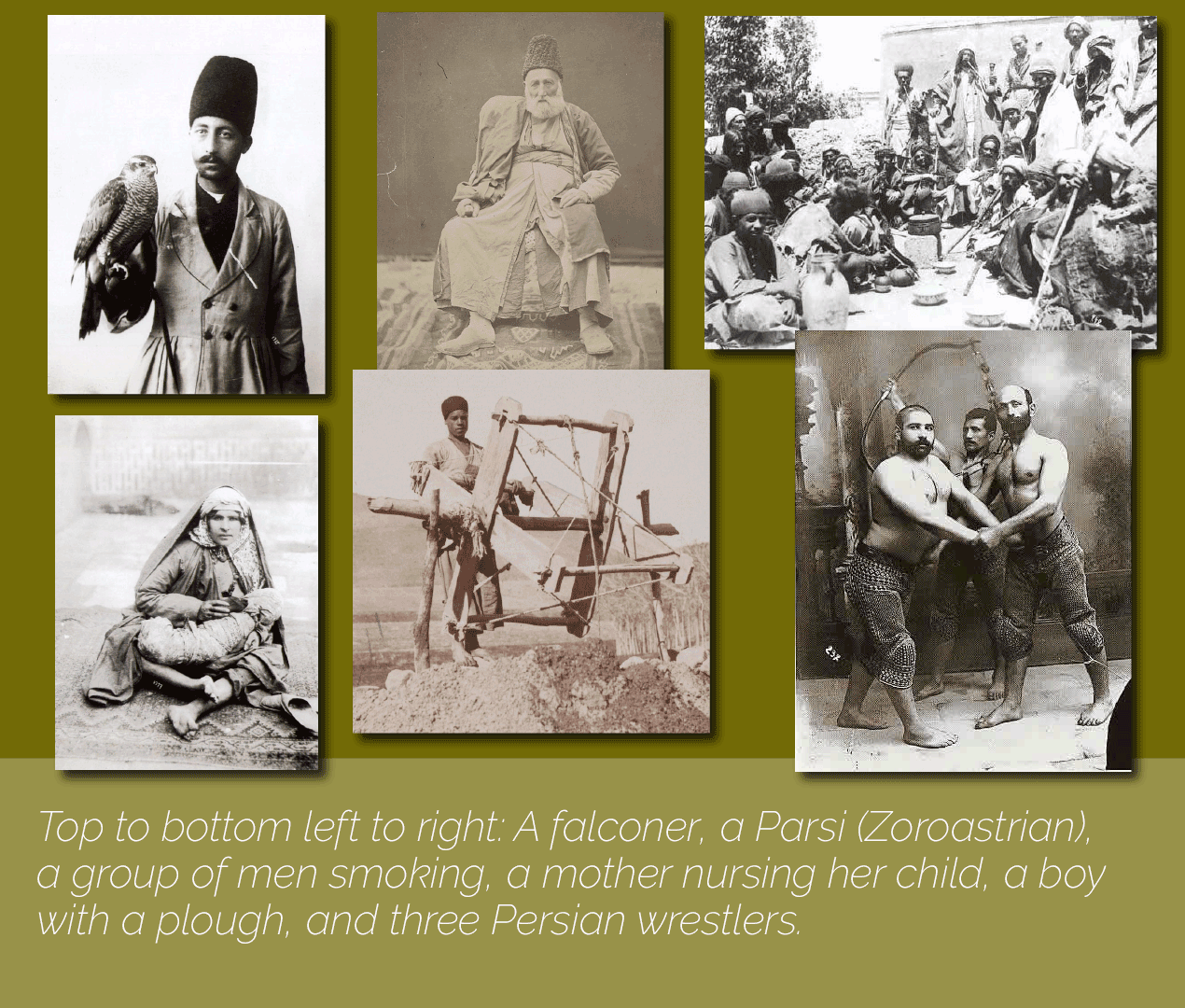

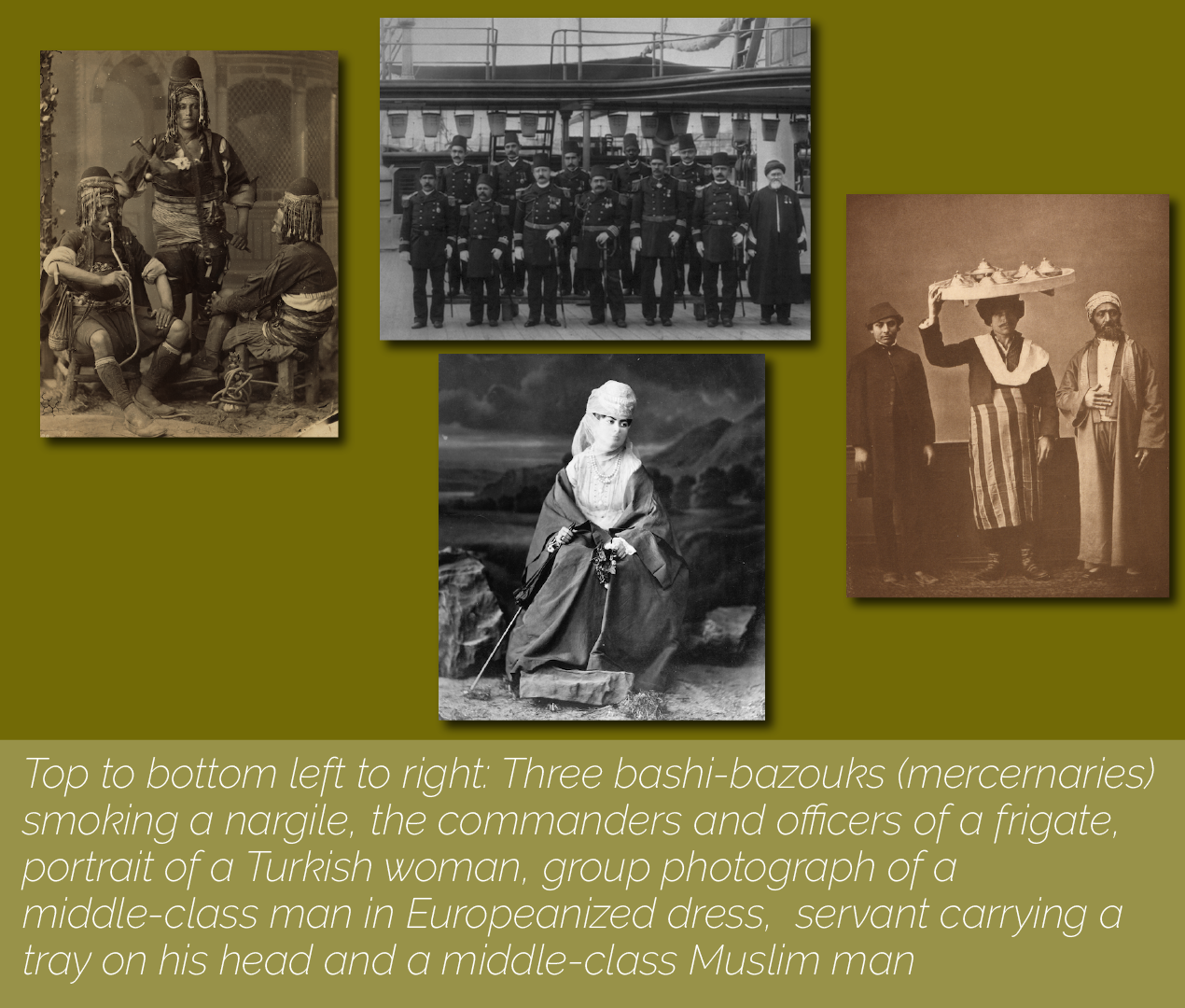

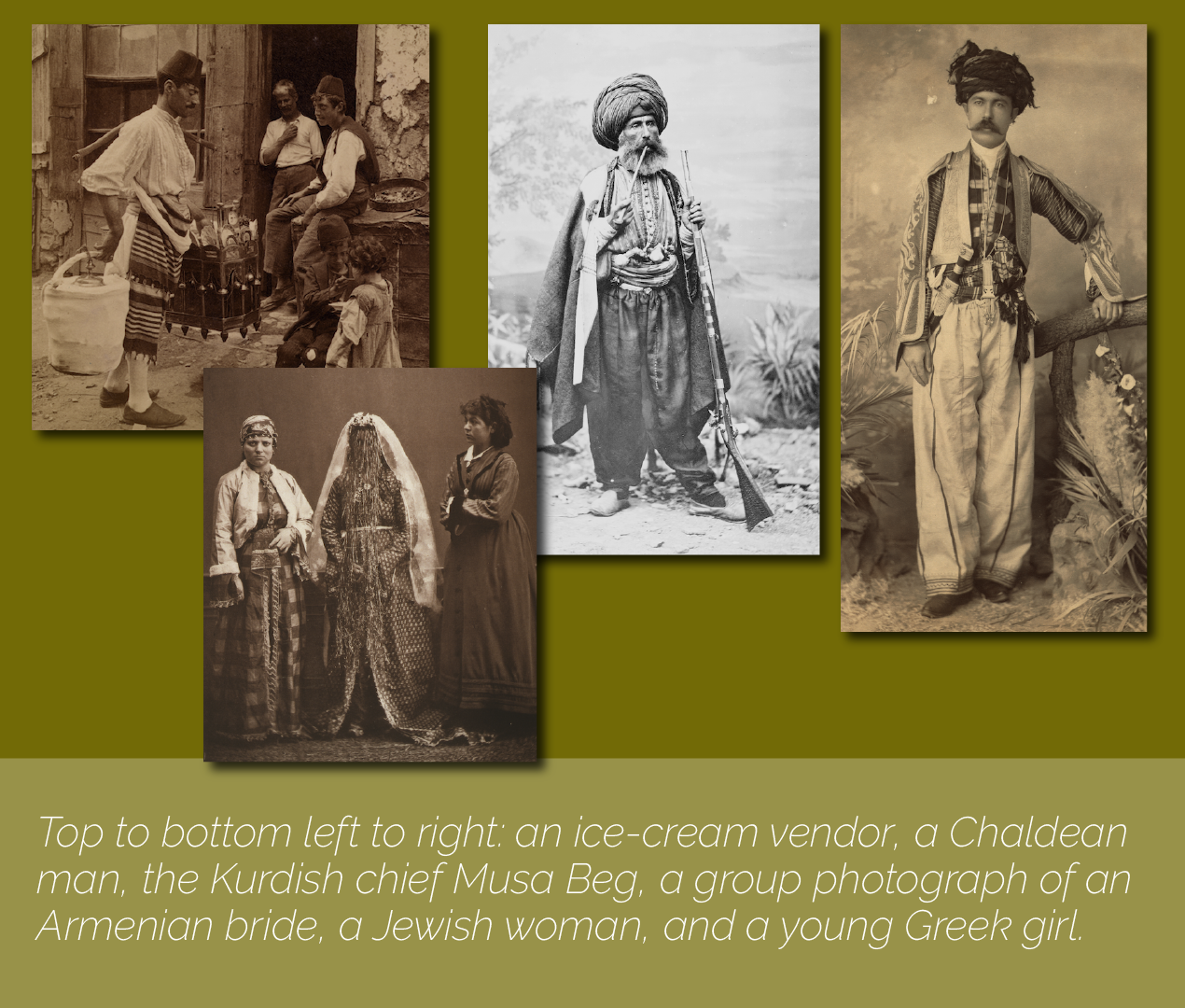

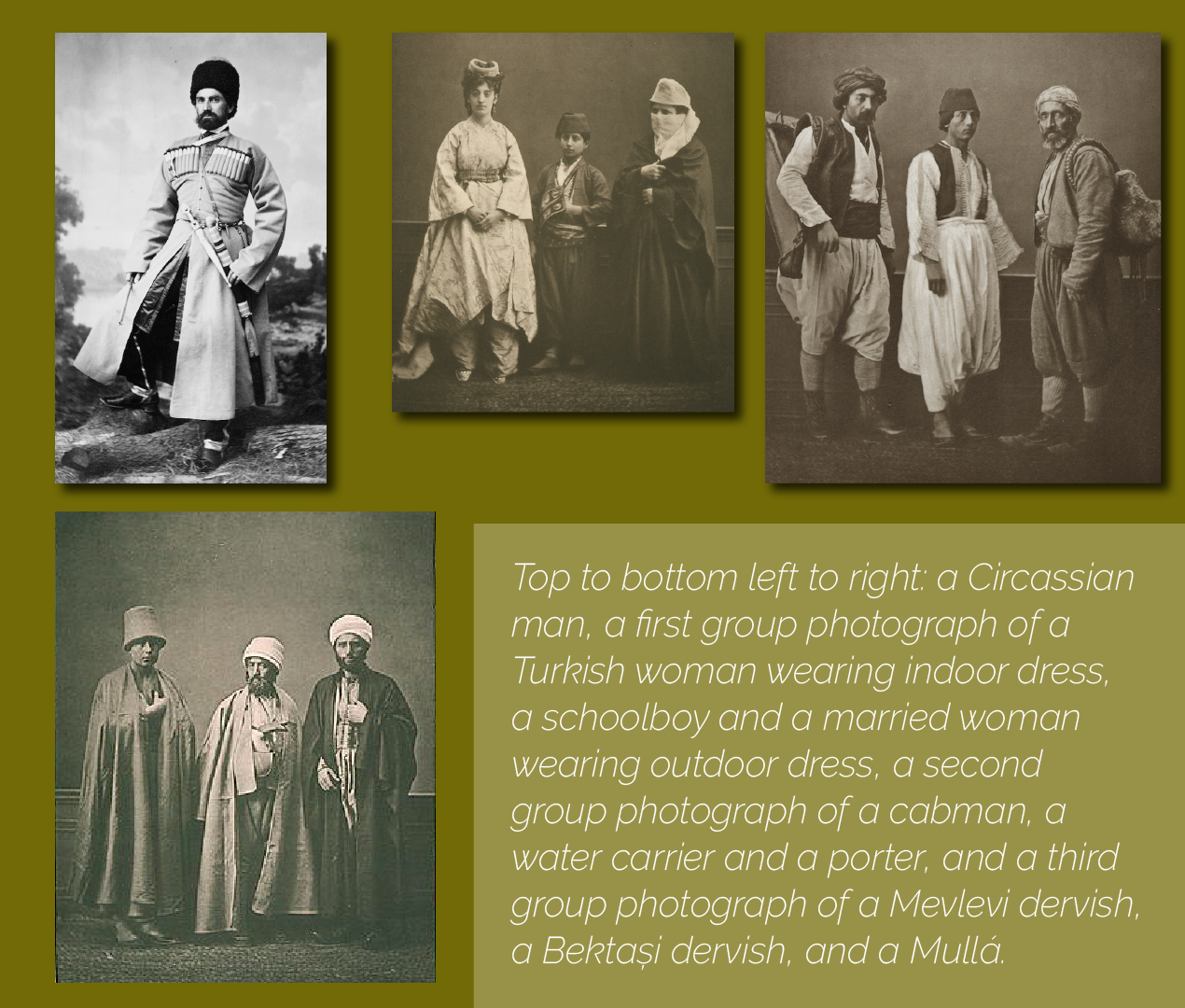

This Part covers the life of Bahá’u’lláh between the age of 46 in 1863 to the age of 51 in 1868.

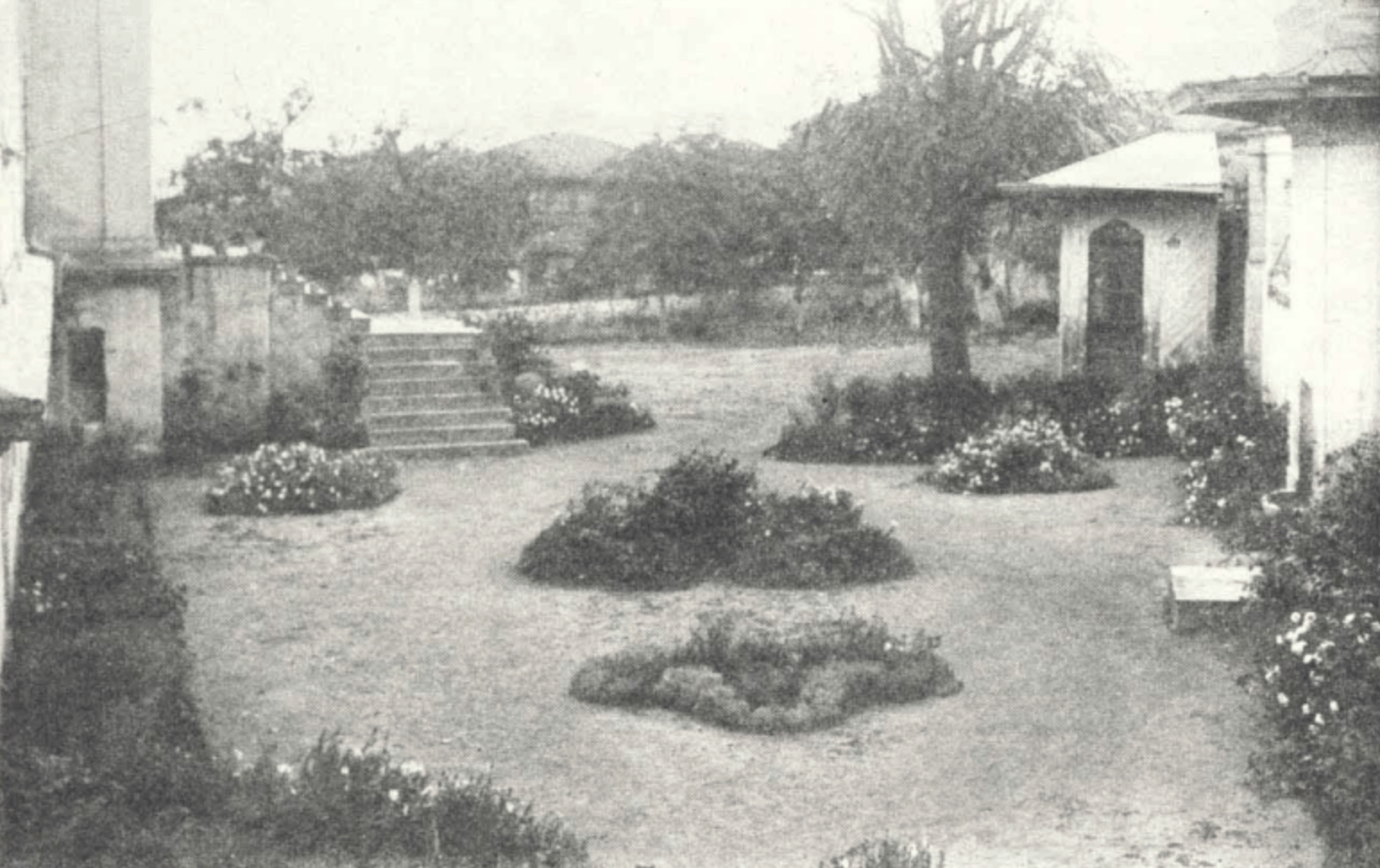

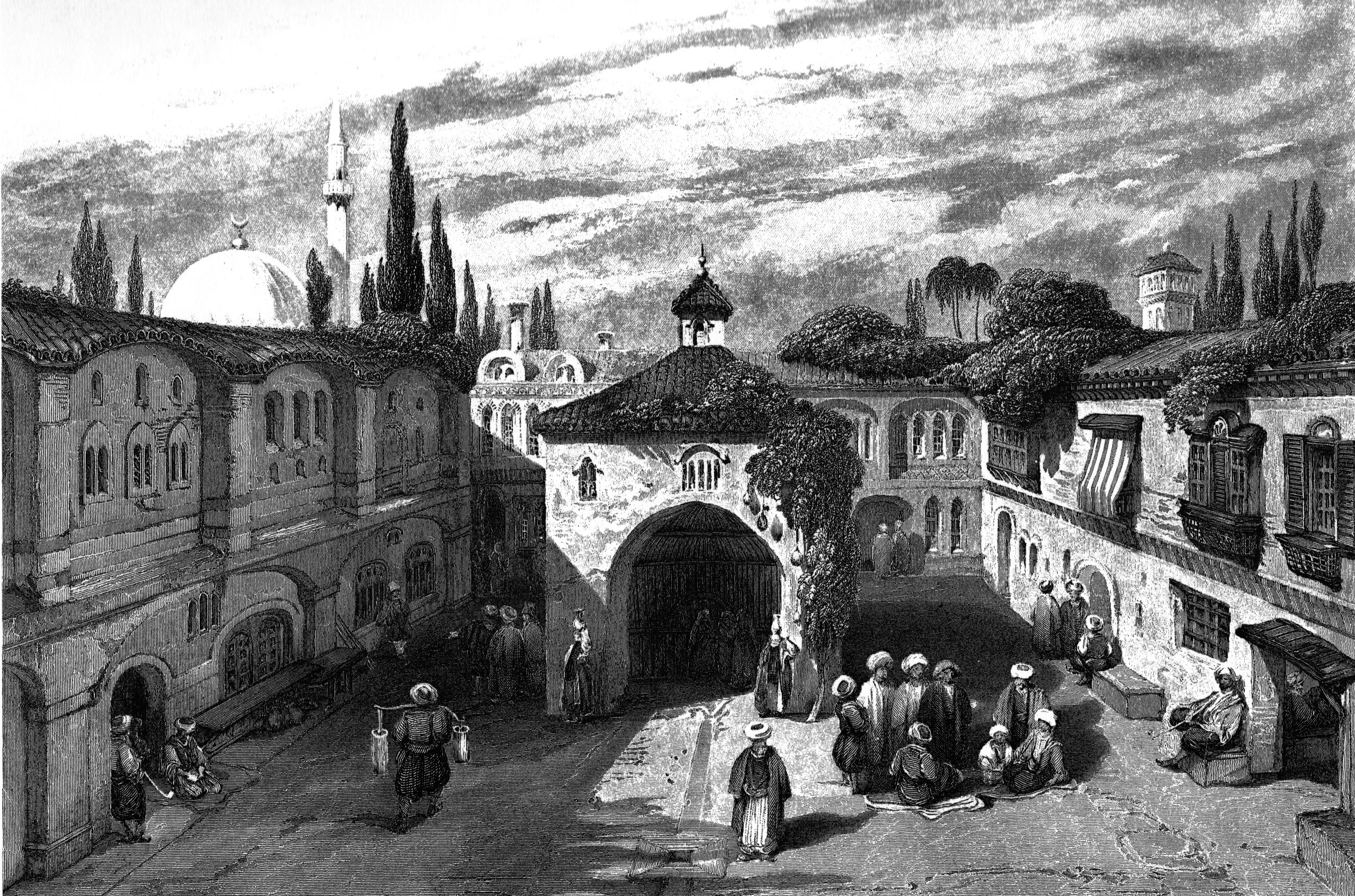

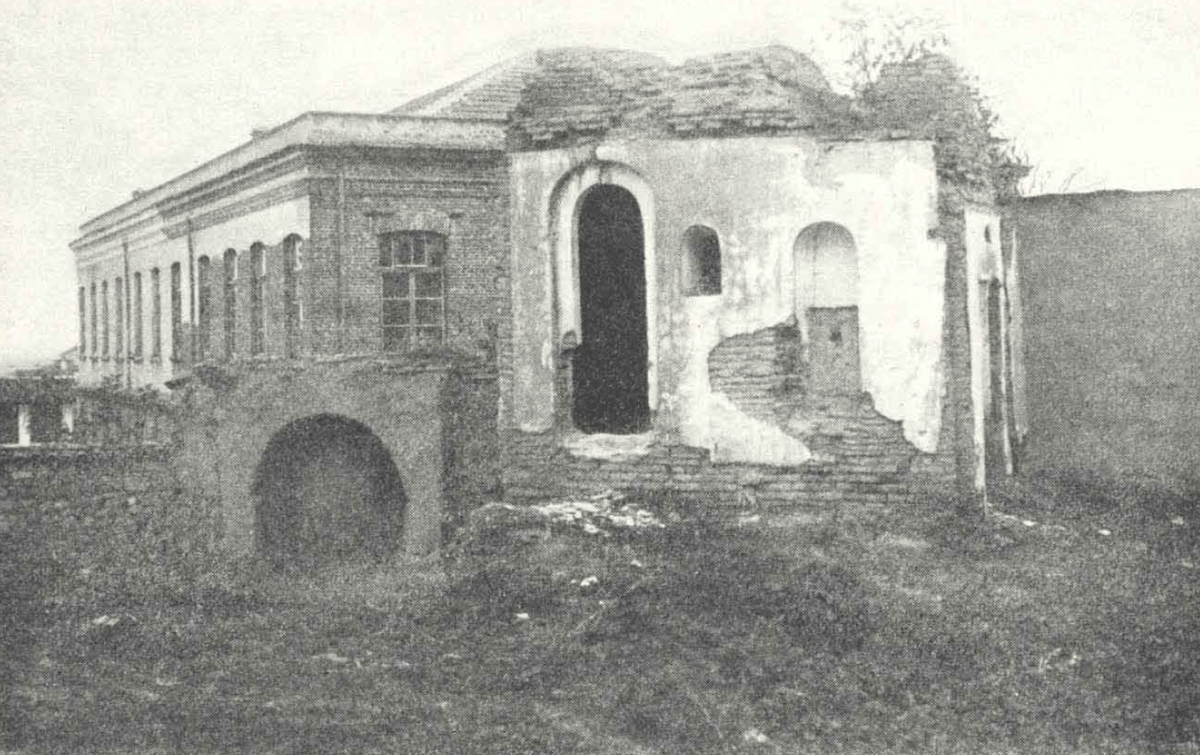

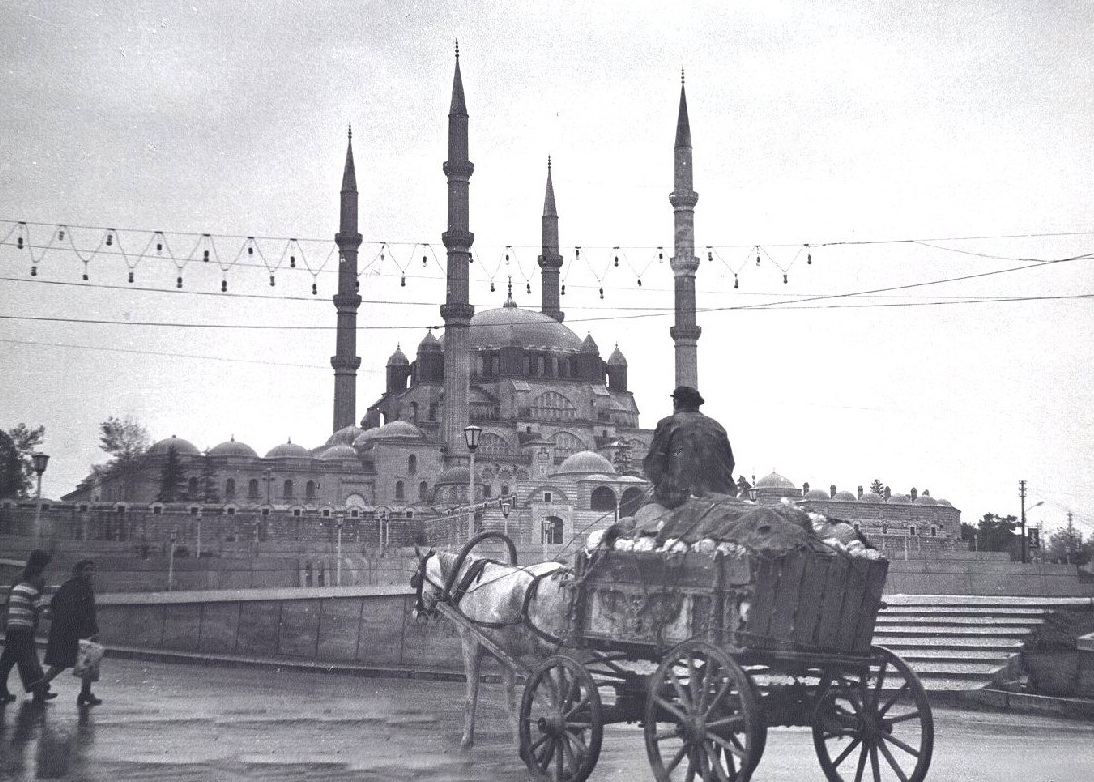

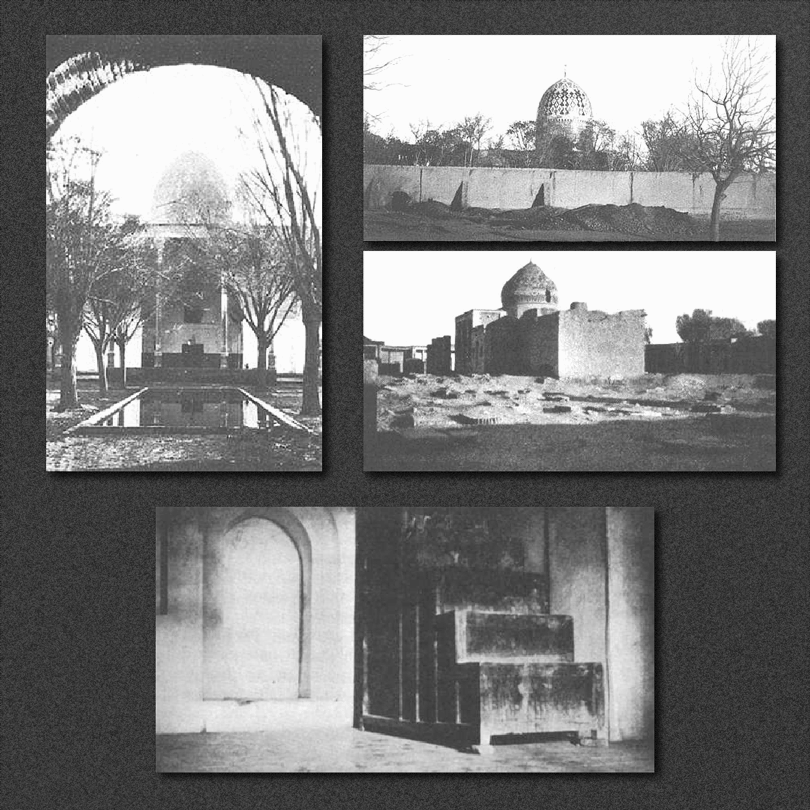

Site of the old Khán-i-'Arab Caravanserai in Adrianople. Source Bahá'í Media, originally from The Bahá'í World, Volume V (1932-1934), A Visit to Adrianople by Martha Root page 589.

Upon arrival, the exiles spent three days huddled together in the Khán-i-‘Arab, a two-story caravanserai near the house of ‘Izzat-Áqá. The accommodation in the caravanserai was poor and quarters were tight.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 218.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868: APPENDIX II: A Visit to Adrianople from an article by Martha L. Root, page 436.

Ottoman army uniforms from 1850 - 1896 were dark blue and red, inspired by both the French zouave uniforms, and the Imperial German Army dunkelblau uniform. This general staff officer Ottoman uniform is the closest to 'Alí Big's Yüzbaşı uniform we could find. Source: The New York Public Library.

'Alí Big Yúz Báshí, the Turkish centurion who had been in charge of the journey from Constantinople to Adrianople, came to Bahá'u'lláh before taking his leave and begged for a promotion. He was older, had been a centurion too long, and longed for the rank of Big-Bashí in Adrianople. What he was asking for was essentially the promotion from Captain to Lieutenant-Colonel.

Baha'u'llah assured 'Alí Big that all would be well with him, and before long 'Alí Big was back in Adrianople, promoted to the rank he desired. Some time later, 'Alí Big returned to Bahá'u'lláh for another promotion, and he received it. Later still, he arrived wearing the badge of Mír-Áláy (Brigadier), but it wasn't enough and he asked Bahá'u'lláh to attain the rank of Páshá, to which Bahá'u'lláh responded:

“How long do you want to live?”

Shortly thereafter, Brigadier 'Alí Big passed away.

Wikipedia: Template: Ottoman Military Ranks.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 219.

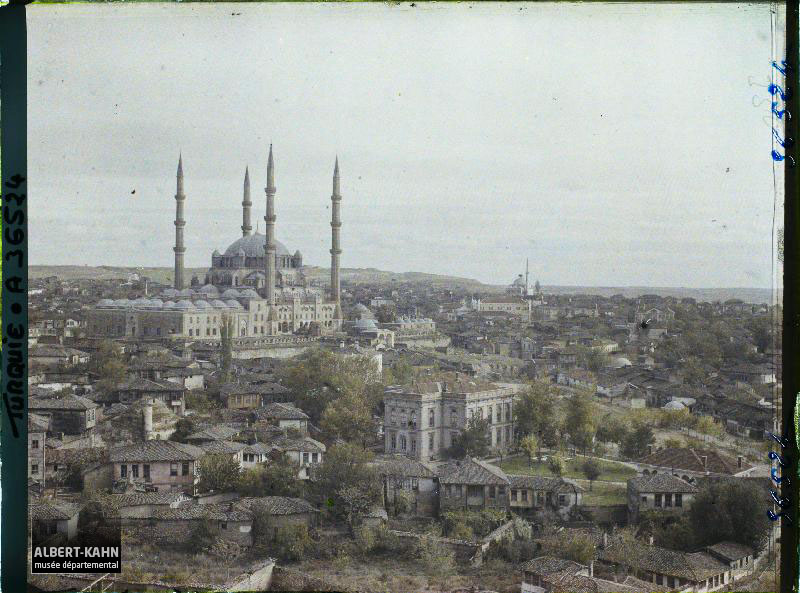

1922 Panorama of the city of Erdine and view of the Selimiye Mosque. Photographer: Frédéric Gadmer, Source: Archives de la Planète - Collection Albert Kahn.

Bahá'u'lláh and His Family were moved to a summer house, in the Murádíyyih quarter, near the Takyiy-i-Mawlaví, a Ṣúfí meeting-place adjacent to the Murádíyyih mosque.

The house was too small for Bahá'u'lláh and His family and inadequate for the harsh winter weather, and the Family moved again a week later.

Their first winter in Adrianople was bitterly cold, the coldest in living memory, and the exiles, who did not have winter clothes, suffered greatly. Water froze in earthen jars and copper vases, breaking them to pieces. One morning, 'Abdu'l-Bahá tried to open the door of His room, but the cold froze His fingers to the iron bar, and when He pulled His hand back, the skin tore off. In order to drink a glass of water, the exiles had to light a fire and melt the ice and people froze to death in the streets.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 218.

Lady Blomfield, The Chosen Highway, page 62.

The Diary of Ahmad Sohrab, 5 May 1913.

Click to listen to a recitation of Lawḥ-i-Anta'l-Káfí (Long Healing Prayer) in Arabic, with subtitles in English, produced by the Utterance Project.

Lawḥ-i-Anta'l-Káfí (Long Healing Prayer), also known as the Lawḥ-i-Shifá or Lawḥ al-Shafá-al-Tawíl, is a healing prayer of very special potency revealed in Arabic by Bahá'u'lláh during His early years in Adrianople. In the original Arabic, the prayer rhymes throughout, with 39 repetitions of the verse “Thou the Sufficing, Thou the Healing, Thou the Abiding, O Thou Abiding One!” and 39 invocations calling on God and His various attributes. The overall effect of the prayer is akin to the waves of the sea, rhythmic and meditative in nature, as can be heard in the above recitation in the original Arabic, produced by the Utterance Project.

Partial Inventory ID: BH00870

Bahá'u'lláh, The Long Healing Prayer.

Directives from the Guardian: 160: PRAYERS (Daily Obligatory).

The Utterance Project: The Long Healing Prayer by Bahá’u’lláh.

Letter from the Universal House of Justice dated 28 September 2008 addressed to Mr. Robert Yoder.

Wikipedia: Long Healing Prayer.

Digital recreation of a vintage postcard showing the neighborhood around the Murádíyyih mosque in the early 20th century.© Violetta Zein.

After a week, Bahá'u'lláh and His Family were moved again in the same northeastern neighborhood of Edirne, close to the Murádíyyih mosque, which is still standing. Although this house was more spacious and on higher ground, offering a good view of the entire city, it was too small and difficult to access.

The exiles, who were still living in the Khán-i-‘Arab caravanserai, moved into the house Bahá'u'lláh had just vacated in Murádíyyih. A third house was rented for Mírzá Músá, Mírzá Yaḥyá, and their families. All three houses were old, draughty, and badly constructed, and keeping the cold out was a constant problem.

Ruins of the house of Murádíyyih at the time of Martha Root and Marion Jack's visit to Adrianople in 1932. Source: The Bahá'í World, Volume V (1932-1934), A Visit to Adrianople by Martha Root page 591.

No matter how harsh the winter, Bahá'u'lláh’s station and the constant emanations of His pen brought joy to the hearts of the sincere Bahá'ís who lived through that first horrific winter in utter bliss: they were near the Blessed Beauty, their Beloved, and could listen, day or night, to Bahá'u'lláh’s majestic voice revealing the Word of God. All the difficulties that surrounded them disappeared in light of their one great blessing.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 218-221.

Digitally-transformed still of drone footage showing the neighborhood to the north-west of the mosque of Sulṭán Salím (in the top left-hand corner of the painting).

The Holy Family had lived for six months in the second house in the Murádíyyih quarter, but it was isolated and cramped. A better house needed to be found, and one day, Bahá'u'lláh said to Áqá Mírzá Maḥmúd-i-Káshání: “'You are a tall man and nearer to God. Pray that He may give Us a better house.”

Within a few days, they found the house of ‘Amru’lláh (House of God's Command), in the heart of the city. The house was located northwest of the 16th century Mosque of Sulṭán Salím, the glory of Adrianople, and it was perfect.

The house of ‘Amru’lláh was a spacious, magnificent mansion with its own Turkish bath and a kitchen with running water. Its private andárúní (the inner quarter, for the women and the immediate family) was three stories high and had 30 rooms. The more public bírúní (the men’s side of the house) had four or five beautiful rooms on the upper floor for reception or housing, and for preparing and serving the refreshments.

Although their living conditions had improved, there were financial difficulties as well. Áqá Ḥusayn-i-Áshchí, the cook (Áshchí means “maker of broths"), sometimes only had bread and cheese available for lunch. But he was a resourceful man, and managed to save up meat and oil, storing them aside until he had enough to offer Bahá'u'lláh a small feast.

Áqá Ḥusayn-i-Áshchí also counted the coals that went in each brazier, something Bahá'u'lláh noticed and complimented him on, and his constant attention to saving allowed him to purchase two cows and a goat in order to keep Bahá'u'lláh supplied with milk and yoghurt.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 217 and 221.

Bahá'u'lláh, The Tablet of Aḥmad.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868, pages 169-170.

* REGARDING THE TIME SPENT IN THE SECOND HOUSE IN MURÁDÍYYIH:

H.M. Balyuzi in Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory states on page 221 that Bahá'u'lláh spent 10 months in this house, according to the memoirs of Áqá Riḍá, but Shoghi Effendi in God Passes By states that Bahá'u'lláh spent six months in the house before moving to the house of Amru’lláh. We have abided by Shoghi Effendi’s timetable, as God Passes By is the backbone inspiring this chronology.

Sitting from left to right: Díyá'u'lláh (half-brother of 'Abdu'l-Bahá), Mírzá Muḥammad-Qulí (half-brother of Bahá'u'lláh), Mírzá Muḥammad-'Alí (half-brother 'Abdu'l-Bahá), Mírzá Músá (brother of Bahá'u'lláh). Standing from left to right : Mírzá Áqá Ján (behind Mírzá Muḥammad-'Alí). Originally published in Ustád Muḥammad-'Alíy-i-Salmání, the Barber, My Memories of Bahá'u'lláh, page 56.. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

While Bahá'u'lláh was living in the house of Amru'lláh, He advised those of His companions who could, to start engaging in trade, telling them one night they were all gathered:

“We commanded you to follow a trade so that you may be usefully occupied and not get bored, and may earn money and invite Us to feasts.”

Some became silk-weavers, carpenters, tobacconists, tailors or shopkeepers, others opened confectioner's shops, and some served Bahá'u'lláh in the house of Amru’lláh. The Bahá'ís now plied a trade during the day, and gathered together in the evenings, a delightfully happy state that lasted a year, from 1864 to 1865.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 221-222.

A late 19th century painting of a coffee House in Tophane, Istanbul by Megerdich Jivanian (from Thomas Allom). Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Every day, a retired Ottoman officer belonging to the Baktashí Ṣúfí order came to sit in a coffee house across the street from the house of Bahá'u'lláh. The officer was joyful and generous, inviting a new person to share his lunch and coffee each day. The man had heard about Bahá’u’lláh and knew something about the Faith, but always refused the Bahá'ís’ invitations to enter Bahá'u'lláh's presence, saying:

“How can I, the essence of sin, stand in the Presence of the Essence of Holiness! I am not worthy of this privilege. Whenever I find that I have deserved such an honor, I will go; but not now, not now!”

One day, the Baktashí arrived at the mosque with a mat under his arm, and 'Abdu'l-Bahá was among those present. He joyfully saluted everyone and said:

“Today I am going to start on a long journey; therefore, I beg you to forgive all my past shortcomings!”

Then, he walked toward the court of the Mosque, laid down on one half of his mat, covered himself with the other half, and passed away. This kind and generous man's funeral was a testament to his life, He died in a state of joy, having recognized Bahá'u'lláh.

The Diary of Ahmad Sohrab, 22 August 1913.

In a visual homage to the story of the grapes of Bahá'u'lláh below, a 1923 photograph of a man selling grapes in Istanbul (cropped). Photographer: Frank G. Carpenter. Source: Library of Congress.

Muṣṭafá Big had been Bahá'u'lláh's neighbor as a child, when He lived in the house of Amru’lláh. He carried yoghurt to Bahá'u'lláh and in return, Bahá'u'lláh always gave him pilau rice to carry home in exchange.

Much later, when he was 85 years old, Muṣṭafá Big, in speaking to Martha Root, would describe to her Bahá'u'lláh's nobility in His demeanor and His walk, the dignity and power He evinced, and how everyone revered and saluted Him when He walked the streets of Adrianople. He also recalled that, even though they had little money, Bahá'u'lláh's home still had a kitchen for the poor.

Not far from the house of Amru’lláh was a large garden, which Bahá'u'lláh often visited. It was about a seven-minute walk from either the Mosque of Sulṭán Salím or the Muradíyyih Mosque, and spanned three city blocks. Bahá'u'lláh would come to this spot in the late afternoons, rejoined by His followers. Mírzá Músá’s home was close to the garden, and Bahá'u'lláh would sometimes stop to visit His younger brother before returning home.

The garden boasted grapevines and Muṣṭafá Big remembered that Bahá'u'lláh, whom they called "Bahá'í Big," would always give them so many grapes from His own hand.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 225-227.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868: APPENDIX II: A Visit to Adrianople from an article by Martha L. Root, pages 434-436.

A photograph of Muṣṭafá Big, 85 years old at the time of Martha Root's visit in 1933. can be found in The Bahá'í World, Volume V (1932-1934), A Visit to Adrianople by Martha Root page 589.

Click on the graphic above to listen to the Tablet of Aḥmad recited in Arabic with subtitles in English, produced by the Utterance Project.

The Lawḥ-i-Aḥmad (Tablet of Aḥmad) is one of the most well-known Tablets of Bahá'u'lláh. It was revealed by Bahá'u'lláh in Arabic around 1865 in honour of Aḥmad, a native of Yazd, before the attempt on His life.

Aḥmad attained the presence of Bahá'u'lláh in Baghdád and remained there, installing his small cloth-making machine. Two years after Bahá'u'lláh was exiled, Aḥmad set out on foot, and found the Tablet of Aḥmad waiting for him in Constantinople. Realizing that Bahá'u'lláh desired him to teach in Persia, he did not continue to Adrianople, and, instead, traveled through the regions of Persia, and brought many people into the Bahá'í Faith.

Partial Inventory ID: BH02022

Bahá’í Reference Library: Tablet of Aḥmad.

Bahá’í Library Online: Chronology: Life of Bahá’u’lláh.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868, pages 107, 116 and 126.

Faizi, A Flame of Fire: The Story of the Tablet of Aḥmad Part I, Published in Bahá'í News number 432, March 1967.

Faizi, A Flame of Fire: The Story of the Tablet of Aḥmad Part II, Published in Bahá'í News number 433, April 1967.

“…one of the most dramatic episodes in the ministry of Bahá’u’lláh… the most turbulent and critical period of the first Bahá’í century…”

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By

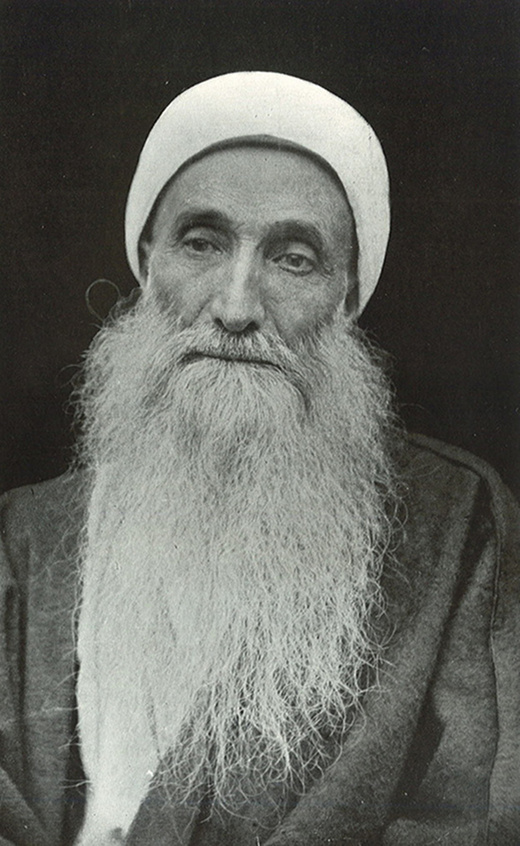

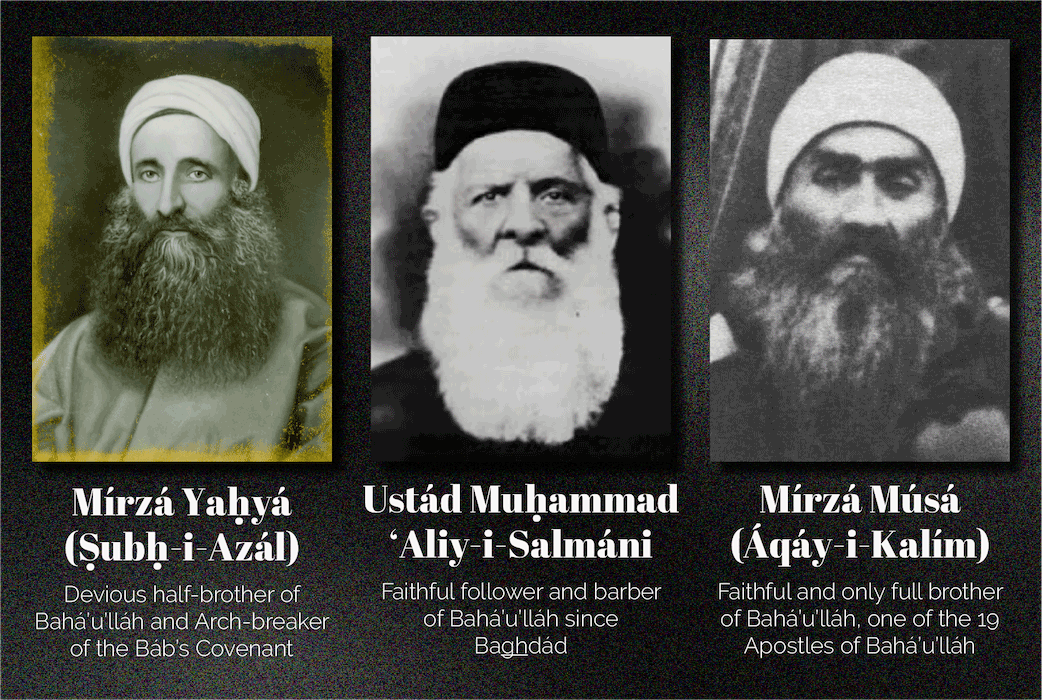

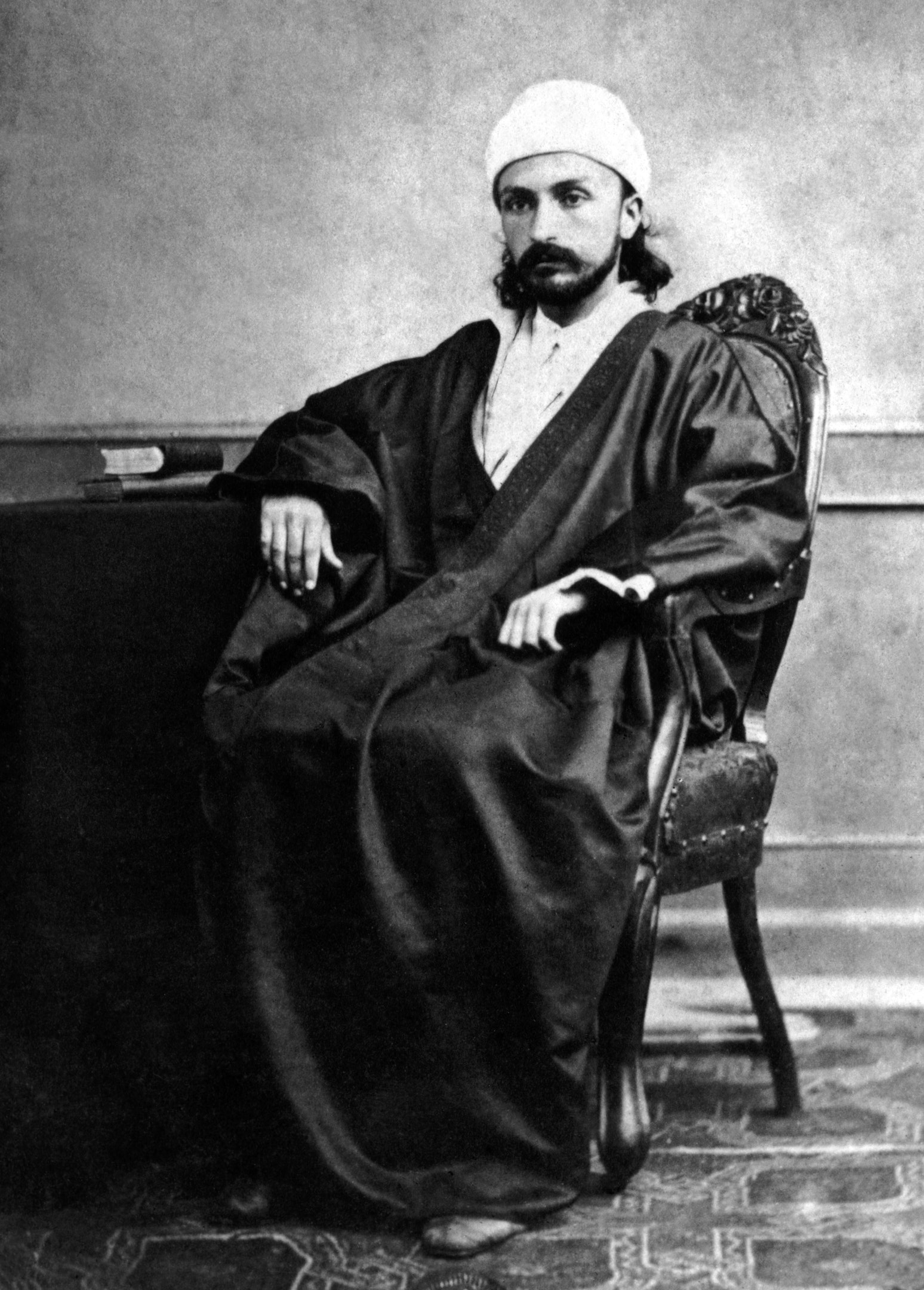

Mírzá Yaḥyá, Ṣubḥ-i-Azál (Morning of Eternity), in 1888, twenty-three years after the events depicted in this chapter. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Mírzá Yaḥyá was Bahá'u'lláh’s half-brother, and the figurehead nominee of the Báb. Ever since Bahá'u'lláh’s return from Kurdistán, he had lived in hiding, posing as a shoe merchant, or barricaded in his own house, terrified of any danger to himself. His jealousy at the marks of high honor Bahá'u'lláh received and the utter devotion of His followers raged in his heart.

Mírzá Yaḥyá had been corrupted beyond salvation by his constant association with Siyyid Muḥammad-i-Iṣfahání, the Antichrist of the Bahá'í Revelation, who had promised him unchallenged leadership of the community. Siyyid Muḥammad, was the very personification of evil, greed and deceit. He had committed unspeakable acts, corrupting the text of the Báb’s Holy Writings, modifying the obligatory prayer to include a reference to himself as the Godhead, named himself and his children as descendants of the Báb. Siyyid Muḥammad had played a hand in the murders of Dayyán, and the Báb’s cousin, and had married, a few days after Mírzá Yaḥyá, the second wife of the Báb.

There came a point in 1865 when Mírzá Yaḥyá could no longer be reasoned and he started down his evil path and His open rebellion began, he would go down in Bahá'í history as the Arch-breaker of the Covenant of the Báb.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

“Nor can this subject be dismissed without special reference being made to the Arch-Breaker of the Covenant of the Báb, Mírzá Yaḥyá…” quoted from Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Ustád Muḥammad-'Alíy-i-Salmání, the Barber, My Memories of Bahá'u'lláh, pages 46-48.

“…allowing himself [Mírzá Yaḥyá] to be duped by the enticing prospects of unfettered leadership held out to him by Siyyid Muḥammad, the Antichrist of the Bahá’í Revelation, even as Muḥammad Sháh had been misled by the Antichrist of the Bábí Revelation…” quoted from Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

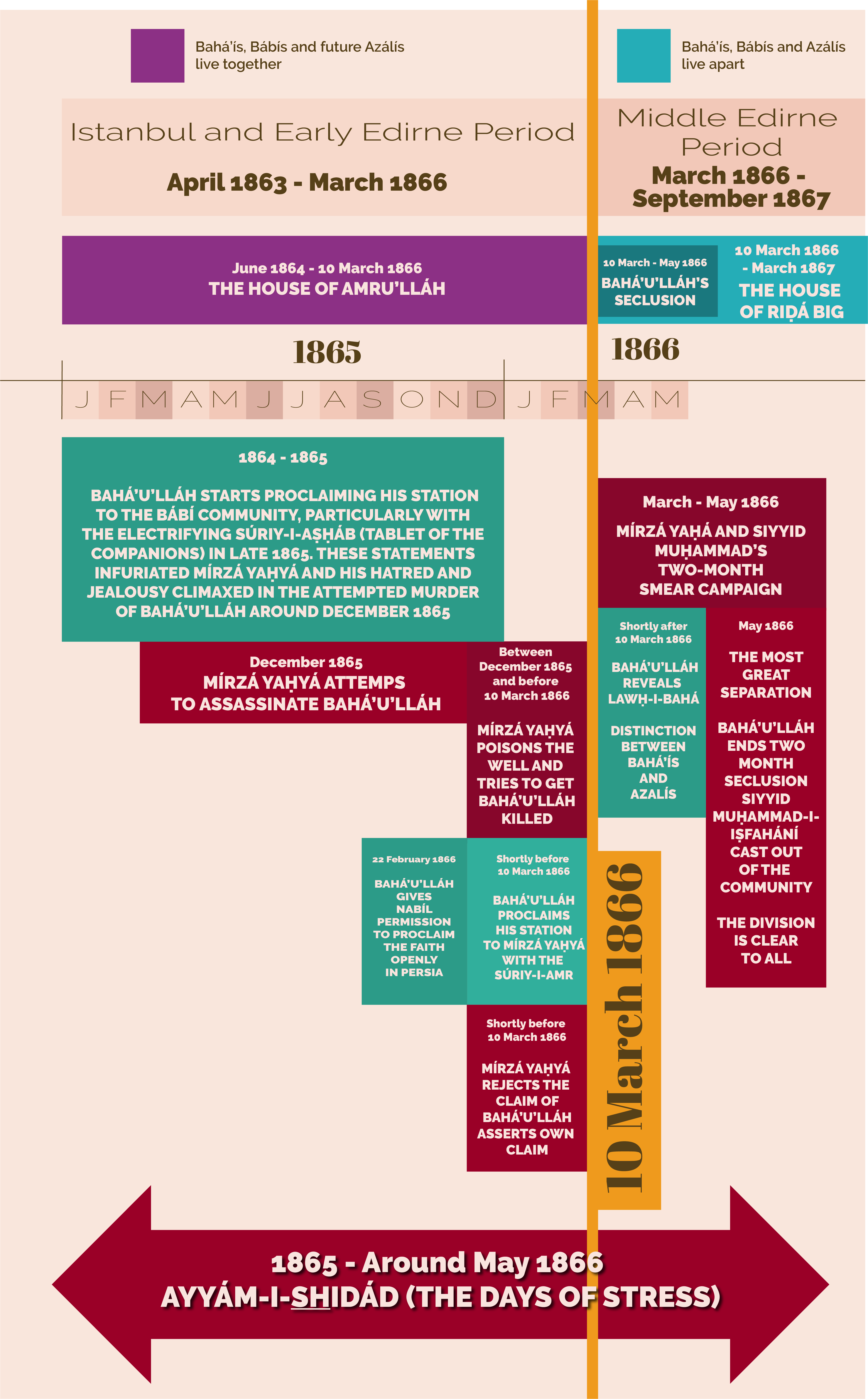

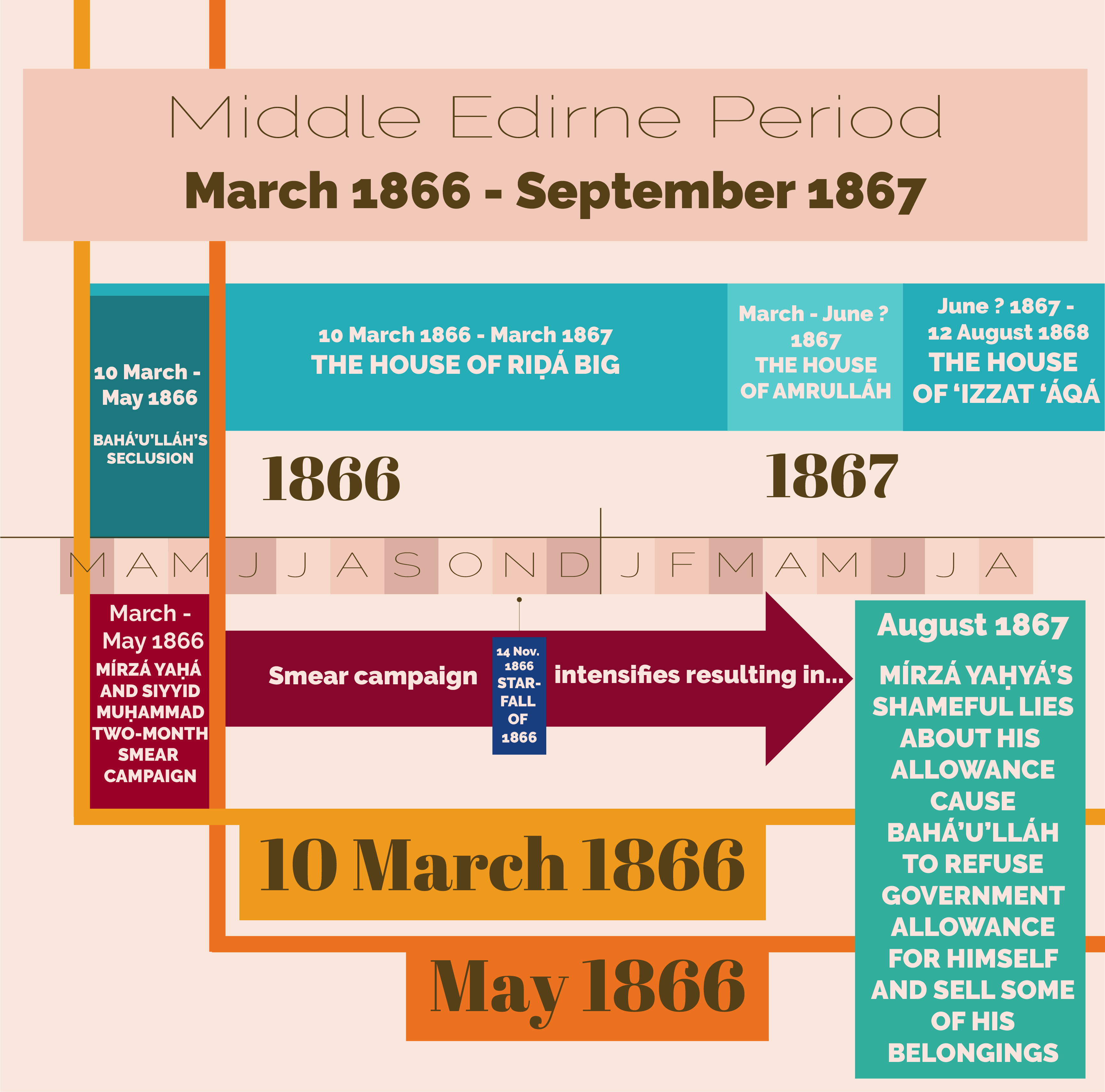

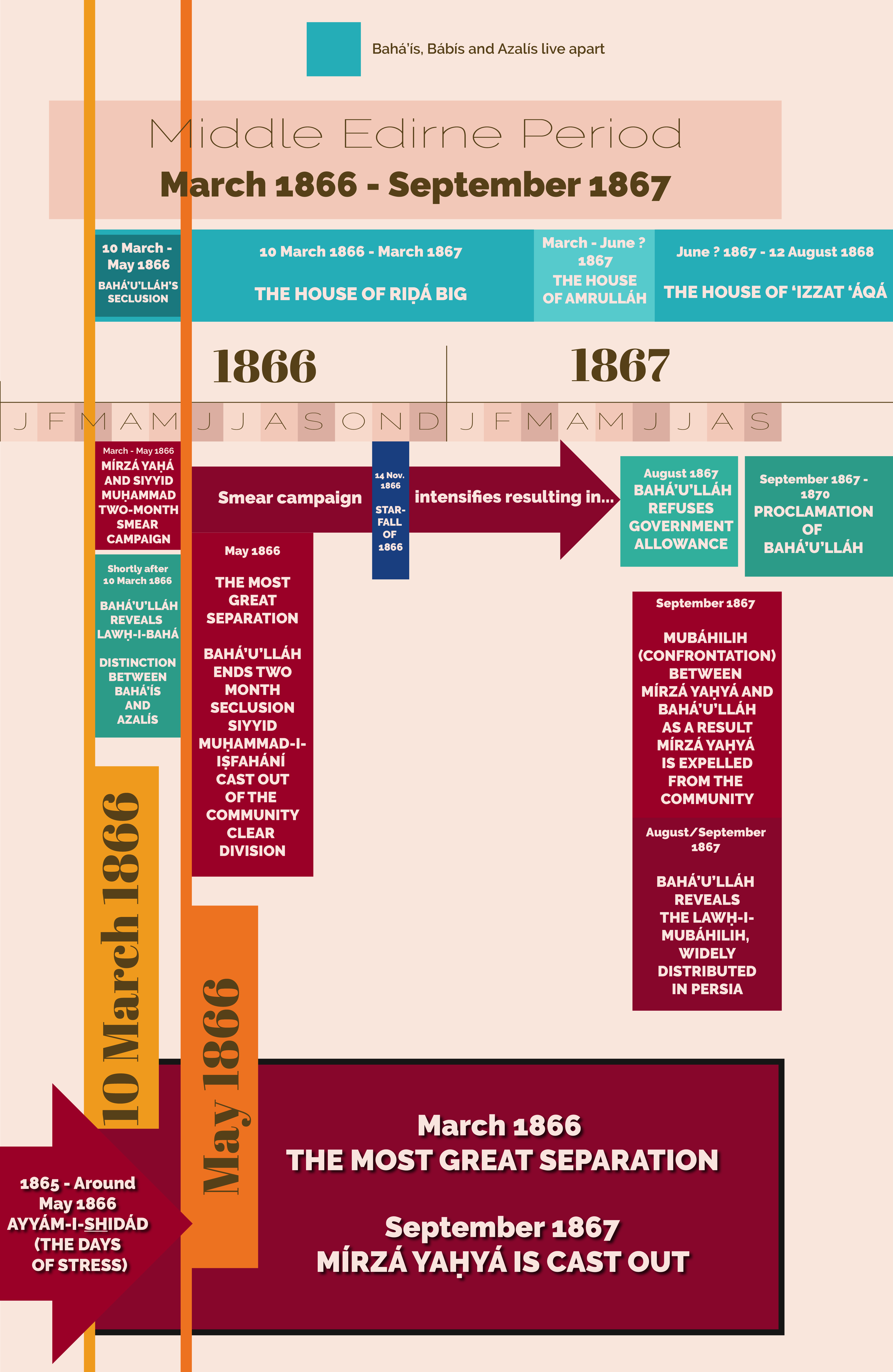

Timeline showing the tensions which led up to the Most Great Separation. © Violetta Zein.

Bahá'u'lláh referred to the period of approximately one year from 1865 to about May 1866 as the Days of Stress (Ayyám-i-Shidád), and sometimes the Year of Stress, that would tear apart “the most grievous veil” and eventually cause “the most great separation.”

Engineered by the evil whisperings of Siyyid Muḥammad and his permanent twisted intrigues and plottings, Mírzá Yaḥyá, would unleash such monstrous chaos on the Faith that it would leave its mark for 50 years, bring incalculable sorrow to Bahá'u'lláh, play into the hands of the Faith’s enemies, confuse and bewilder the Bahá'ís, and damage the prestige of the Faith..

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Bahá'u'lláh, Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá'u'lláh, N° CLII.

Ḥájí Mírzá Ḥaydar-‘Alí of Iṣfahán, on whom the Súriy-i- Aṣḥáb had a profound lifelong effect. Source: Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868, page 144.

Bahá'u'lláh revealed the lengthy Súriy-i- Aṣḥáb (Surah of Companions) in Arabic in honor of Mírzá Áqáy-i-Muníb, the faithful companion who had carried a lantern in front of His howdah from Baghdád to Constantinople. This powerful proclamatory Tablet, revealed before Mírzá Yaḥyá's attempt on His life, played a pivotal role in unveiling the station of Bahá'u'lláh to the Persian Bábís and converting them to the Bahá'í Faith, which, no doubt, would have further enraged Mírzá Yaḥyá.

Shaykh Káẓim-i-Samandar recounts the explosive effect of the Súriy-i- Aṣḥáb among the Bábís of Qazvín, saying it "precipitated a great upheaval and created a severe convulsion [among the community]." They organized several meetings to explain, clarify, and understand the weighty Tablet, and everyone became a Bahá'í.

As for Ḥájí Mírzá Ḥaydar-‘Alí, a hero of the Faith, he describes reading the Súriy-i- Aṣḥáb for the first time, saying that, with each verse he read, he "felt as if a world of exultation, of certitude and insight was created within me was enraptured and set aglow." In fact, he was so affected by the Tablet that simply thinking about it fifty years later would make him enter an almost unbearable heightened state of joy.

Partial Inventory ID: BH00076

Translation of excerpts: Shoghi Effendi, The World Order of Bahá’u’lláh, pages 108-109.

Date of revelation from Bahá'í Library Online: Juan Cole, Introduction to the Tablet of Ashab, published in Bahá'í Studies Bulletin, 5:34-6:1, pages 4-74.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868, pages 65-106.

© Violetta Zein.

Approximately a year after arriving in Adrianople, Mírzá Yaḥyá became obsessed with poisoning Bahá'u'lláh to gain control of the community. He knew Bahá'u'lláh's faithful brother, Mírzá Músá, was very knowledgeable about medicine, and, under false pretenses, asked him about the effects of herbs and poisons.

Then, unusually for him, Mírzá Yaḥyá began to invite Bahá'u'lláh to his home, and on one of His visits, Mírzá Yaḥyá served Bahá'u'lláh tea in a cup he had smeared with a toxic substance he had concocted, and he poisoned Bahá'u'lláh.

Bahá'u'lláh was seriously ill for a month, with severe pains and high fever, and the aftermath of the poisoning would leave Him with a shaking hand until the end of His life. His condition was so severe that the family called on a foreign Christian doctor named Shíshmán. The doctor was so shocked by Bahá'u'lláh’s livid skin tone that he fell to his feet, declared His case was hopeless, and left Bahá'u'lláh’s bedside without prescribing a remedy.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 225.

© Violetta Zein.

After his attempt at killing Bahá'u'lláh had failed, Mírzá Yaḥyá had the temerity to accuse Bahá'u'lláh of trying to poison him and accidentally ingesting it Himself.

Bahá'u'lláh had done everything He could to save Mírzá Yaḥyá from himself, but all His kindness and generosity had been repaid with more jealousy, more hatred, and more venom.

During Bahá'u'lláh’s convalescence, 'Abdu'l-Bahá, His half-brother Muḥammad-‘Alí, and most of the exiles had been invited to Mírzá Músá’s house for dinner. It was on this evening that Bahá'u'lláh sat up in His bed and called them over, asking them to sit. He spoke to them, telling them how weak He felt. Shortly after that, Bahá'u'lláh was able to rise and walk on His own, and came to visit His followers.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 225-227.

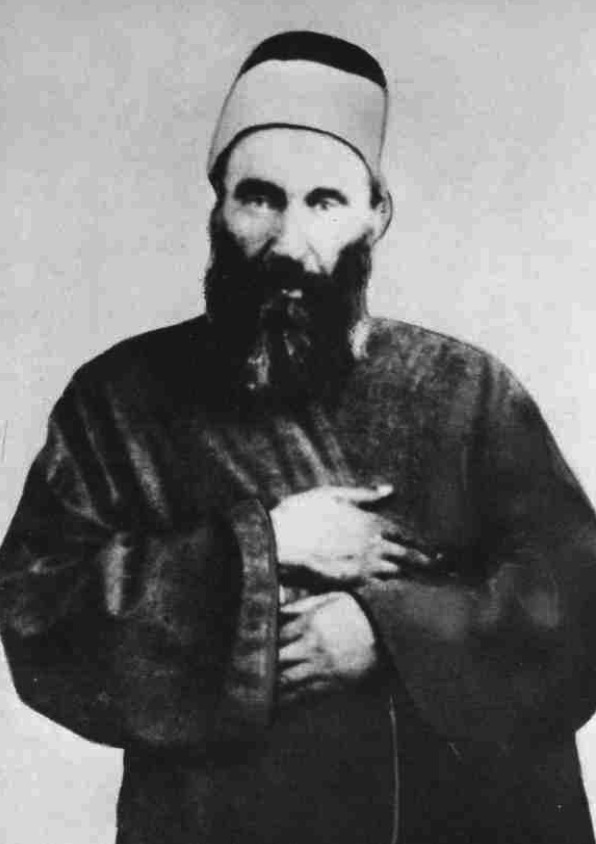

Mullá Muḥammad-i-Zarandí (29 July 1831 – 1892), also known as Nabíl-i-Aʻẓam (the Great Nabíl) or Nabíl-i-Zarandí (Nabíl of Zarand). Nabíl was an eminent Baháʼí historian, author of the The Dawn-Breakers, one of 19 Apostles of Bahá'u'lláh, distinguished teacher of the Faith sent on many missions by Bahá'u'lláh. Source: We are Bahá'ís: Nabil-i-A'zam: An Apostle of Baha'u'llah and the author of Dawn-Breakers.

Yet another example of crisis and victory in the life of Bahá'u'lláh, is that, a few weeks after He had recovered from Mírzá Yaḥyá's assassination attempt, Bahá'u'lláh sent a Tablet to Nabíl in Persia, giving him permission to proclaim the Bahá'í Faith openly. Bahá'u'lláh also permitted Nabíl to speak about Mírzá Yaḥyá and Siyyid Muḥammad's actions in Baghdád, something He had previously asked Nabíl to conceal. It is estimated that almost all the Bábís in Ṭihrán became Bahá'ís as a result. It was during this historic proclamation trip, that Nabíl instituted "Alláh'u'Abhá" as a greeting among Bahá'ís.

Date from Bahá'í Library Online: Chronology of Nabíl based on Moojan Momen's The Baha'i Communities of Iran: 1851-1921 Volume 1: The North of Iran, pages 14-15.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 1: Baghdád 1853 - 1863, pages 203-204.

Encyclopaedia Iranica: Nabil-e-A'ẓam Zarandi.

For the story of Alláh'u'Abhá see Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

For his full name see Wikipedia: Nabíl-i-Aʻzam.

Adrianople well square around 1835. After a painting by F. Hervé. Drawing by W.L. Leitch, engraving by J. Tingle. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Mírzá Yaḥyá continued his plotting to kill Bahá'u'lláh, and poisoned the well of the house of Amru'lláh, the source of water for the Holy Family and Bahá'ís who lived there. This attempt was not successful, and only made a few people fall ill with strange symptoms.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868, page 159-161.

Ustád Muḥammad-'Alíy-i-Salmání, the Barber, My Memories of Bahá'u'lláh, pages 49-53.

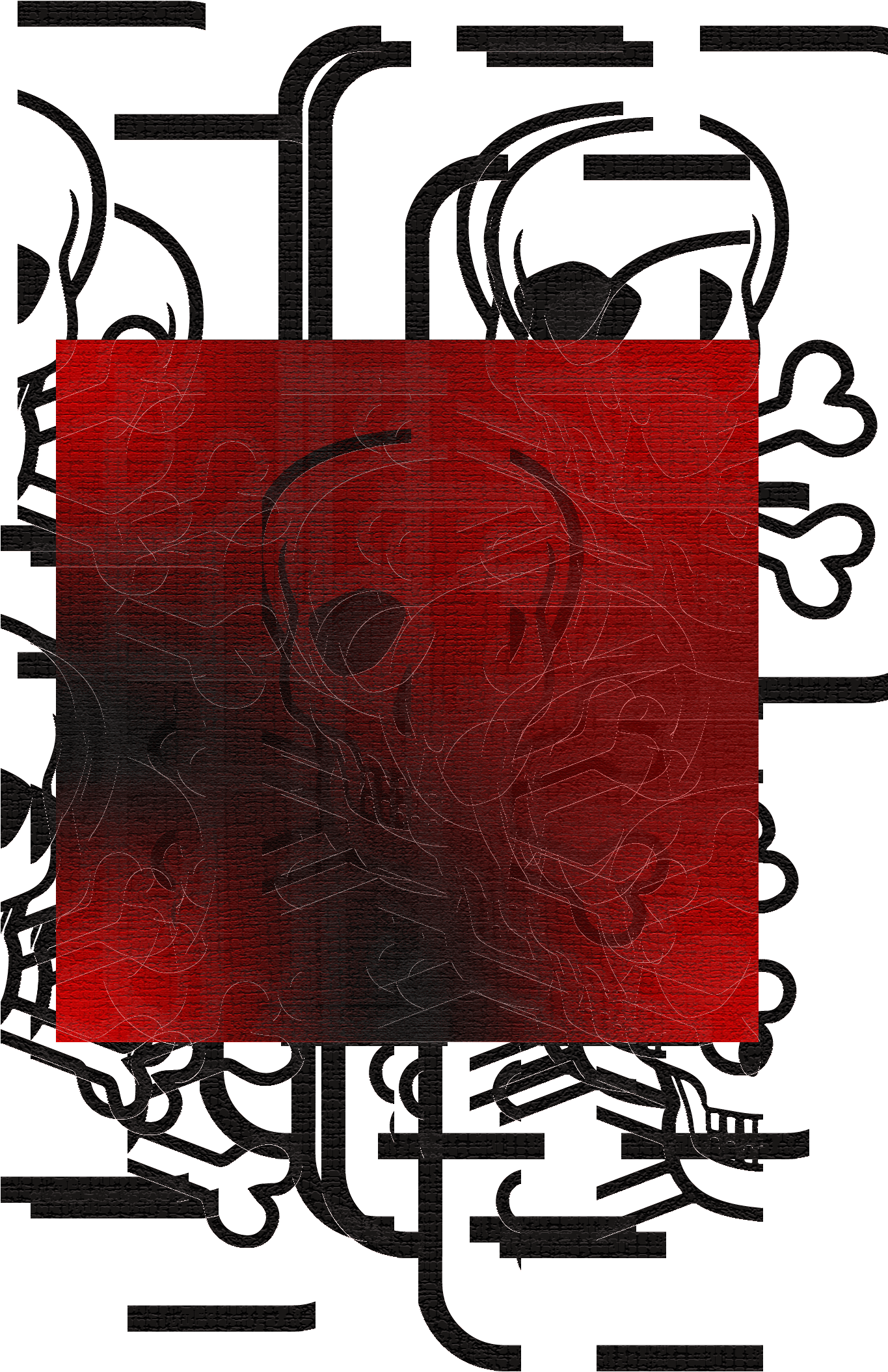

Photo montage of three three individuals mentioned in the story below. Photo of Mírzá Yaḥyáh source: Wikipedia German; Photo of Ustád Muḥammad 'Alíy-i-Salmáni source: Bahá'í Media; Photo of Mírzá Músá source: Bahai-biblio Dans la gloire du Père, chapitres 5 à 32.

In another bolder and desperate attempt, Mírzá Yaḥyá asked Bahá'u'lláh’s loyal barber, Ustád Muḥammad-‘Alí, to murder Bahá'u'lláh, using manipulation and insinuation. When Ustád Muḥammad finally understood what Mírzá Yaḥyá was hinting at, he almost killed Mírzá Yaḥyá then and there. Instead, he went straight to Mírzá Músá, who suggested he keep the matter to himself and try to forget it, the same advice he received from 'Abdu'l-Bahá, and Bahá'u'lláh, but he simply could not, and the news spread rapidly.

The Bahá'í community was now officially divided.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868, page 159-161.

Ustád Muḥammad-'Alíy-i-Salmání, the Barber, My Memories of Bahá'u'lláh, pages 49-53.

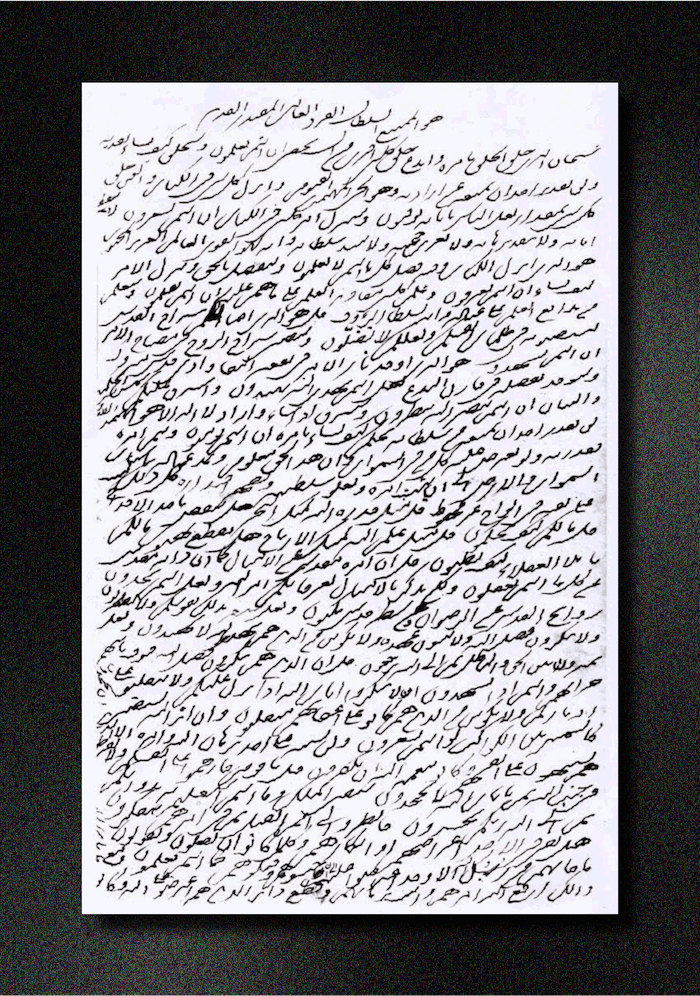

The first page of the Suri-i-Amr in Baha’u’llah’s handwriting which was affected by the poisoning that left his hand trembling, and which was revealed three months after the attempt on His life, around March 1866. Source: Bahá'í Sacred Relics: A Tablet in Baha'u'llah's own hand after He was poisoned by His half-brother.

Three months after He survived the poisoning, Bahá'u'lláh decreed the time had finally come for Him to formally acquaint Mírzá Yaḥyá with His station as “Him Whom God shall make manifest.” Bahá'u'lláh did by revealing a major proclamatory Tablet in Arabic known as the Súriy-i-Amr (Surah of Command). This Tablet was revealed in both the voice of God and in the voice of Bahá'u'lláh and officially stated His claim to Prophethood and the character of His mission, calling the entire creation for witness.

Bahá'u'lláh instructed Mírzá Áqá Ján to deliver and read the Tablet aloud to Mírzá Yaḥyá, and to wait for his response. Bahá'u'lláh was effectively summoning Mírzá Yaḥyá to embrace the Bahá'í Faith, pay allegiance to Him, and He requested an immediate answer.

When he was read the Súriy-i-Amr, Mírzá Yaḥyá became angry and irrational, criticizing Bahá’u’lláh’s choice of Arabic instead of Persian, and repudiating the Tablet. He asked for a delay of one day to formulate his answer, which Bahá'u'lláh granted.

The following day, Mírzá Yaḥyá’s response was outrageous and disgraceful: he made a counter-declaration, stating the hour and minute when he had received divine Revelation, and ordained the peoples of the world to submit to him unconditionally. He had effectively rejected Bahá'u'lláh's claim without bothering to articulate it, and had irretrievably broken the Covenant.

Shoghi Effendi would later call this final rupture between Bahá'u'lláh and Mírzá Yaḥyá “one of the darkest dates in Bahá’í history.”

Partial Inventory ID: BH00084

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Steven Phelps "The Writings of Bahá'u'lláh" in Routledge World: The World of the Bahá'í Faith, First Edition, Edited By Robert H. Stockman, page 59.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868, pages 161-162.

Lady Blomfield, The Chosen Highway, page 60.

Ustád Muḥammad-'Alíy-i-Salmání, the Barber, My Memories of Bahá'u'lláh, page 45.

The house of Riḍá Big in the 1960s. Source: Bahá'í Media.

After the Most Great Separation, Bahá'u'lláh retired from the Bahá'í community, removing Himself from a situation of disunity and allowing believers the freedom in choosing to follow Him or Mírzá Yaḥyá.

Bahá'u'lláh left the house of ‘Amru’lláh on 10 March 1866, moving His immediate family to the house of Riḍá Big, in another neighborhood of Adrianople. He instructed His brother Mírzá Músá to divide all the furniture, bedding, clothing and utensils in the house of ‘Amru’lláh, giving half to Mírzá Yaḥyá’s household and dividing the rest among the believers.

He asked Mírzá Músá to give Mírzá Yaḥyá some relics he had coveted for a long time, such as the seals, rings, and manuscripts the Báb had entrusted to Him shortly before His martyrdom. He also required Mírzá Músá to ensure Mírzá Yaḥyá received the full share of his government allowance, to have his mail delivered directly to him, and to assign one of the exiles to serve in his household.

Bahá'u'lláh’s seclusion was total. For two months, He refused to associate with followers friend, stranger or foe, and He remained in the house of Riḍá Big for approximately one year, until Mírzá Yaḥyá and Siyyid Muḥammad’s abominable actions forced Him out of retirement.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 232.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868, pages 162 and 164-165.

For the full story on the Báb’s personal effects entrusted to Bahá'u'lláh, go to Part II: 9 July 1850 - The Martyrdom of the Báb and July 1850 - Bahá'u'lláh receives the Báb's seals and personal effects

The back garden of the house of Riḍá Big in 1959. Source: Bahá'í Media.

Forbidden access to the house of Riḍá Big, Bahá'u'lláh’s companions were distressed and heartbroken, cut off from His light and guidance. Inconsolable, they cut off all ties with the followers of Mírzá Yaḥyá and his evil influence.

'Abdu'l-Bahá and Mírzá Músá shouldered many responsibilities during Bahá'u'lláh’s absence. Mírzá Músá later qualified this difficult period as "a most great commotion," and one of Bahá'u'lláh's companions described the "tumult and confusion" in the hearts of the believers, who feared they might never see Bahá'u'lláh again.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868, page 163-164.

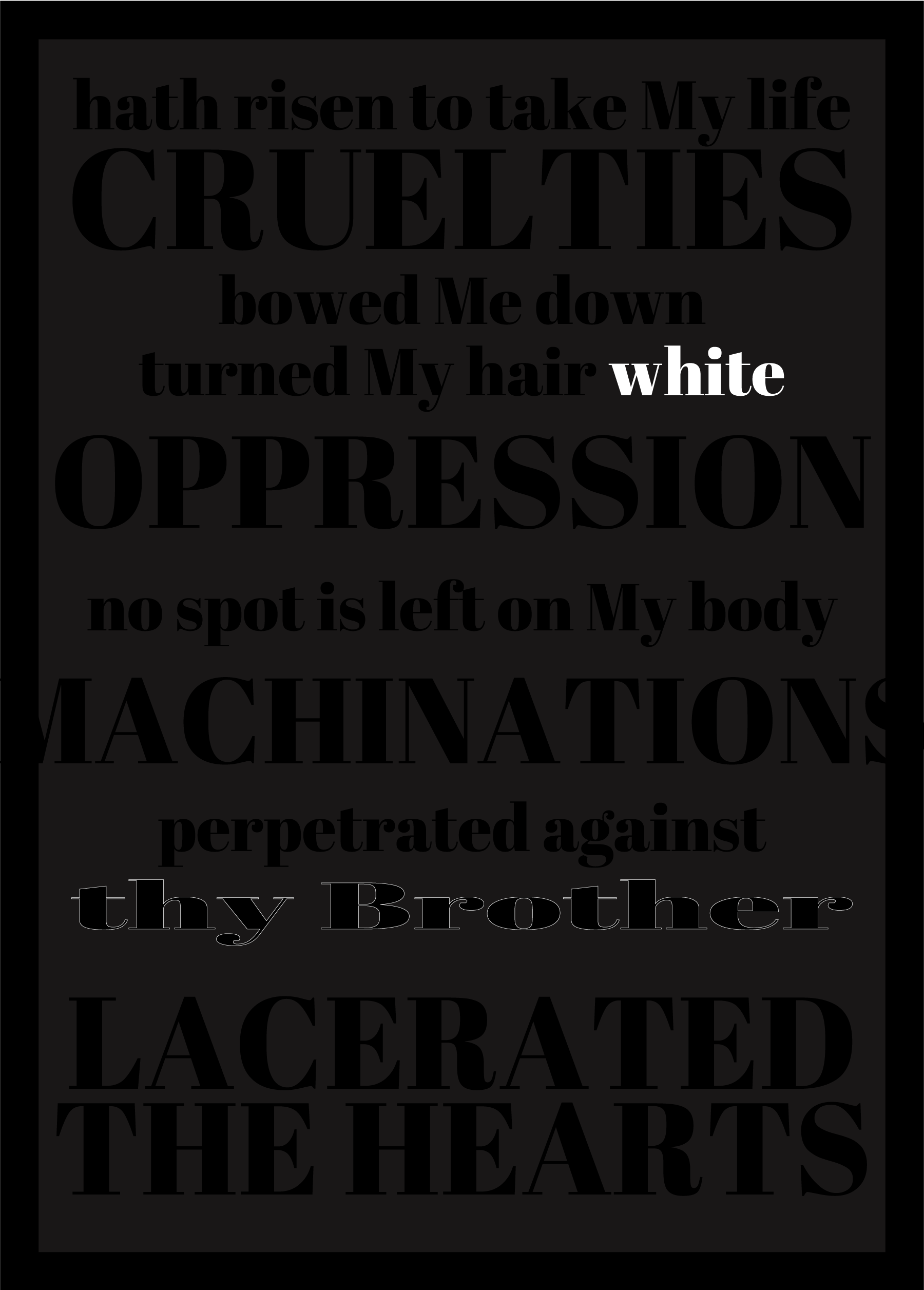

Bahá'u'lláh's words about the effect the Most Great Separation had on Him, quoted by Shoghi Effendi in God Passes By. © Violetta Zein.

The Most Great Separation broke Bahá'u'lláh's heart, plunging Him in a state of “acute anguish," according to Shoghi Effendi. Excerpts from the heart-rending Tablets Bahá'u'lláh revealed at this time are found in God Passes By, where Bahá'u'lláh describes in detail the effect of Mírzá Yaḥyá and Siyyid Muḥammad’s cruelties and betrayals on His body and soul.

Bahá'u'lláh states that Mírzá Yaḥyá, whom He raised with loving kindness for years "hath risen to take My life," that the cruelties "inflicted" by His "oppressors" have "bowed me down", "turned My hair white," and altered the freshness of His countenance and faded His brightness.

Bahá'u'lláh swears by God that "No spot is left on My body that hath not been touched by the spears of thy machinations" and qualifies that Mírzá Yaḥyá perpetrated against his own Brother "what no man hath perpetrated against another,” and that the evil machinations and treachery of the Covenant-breakers caused unspeakable pain to the denizens of Paradise, lacerating their hearts, tearing the Veil of Grandeur, and causing the Holy Ones to prostrate upon the dust.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 241.

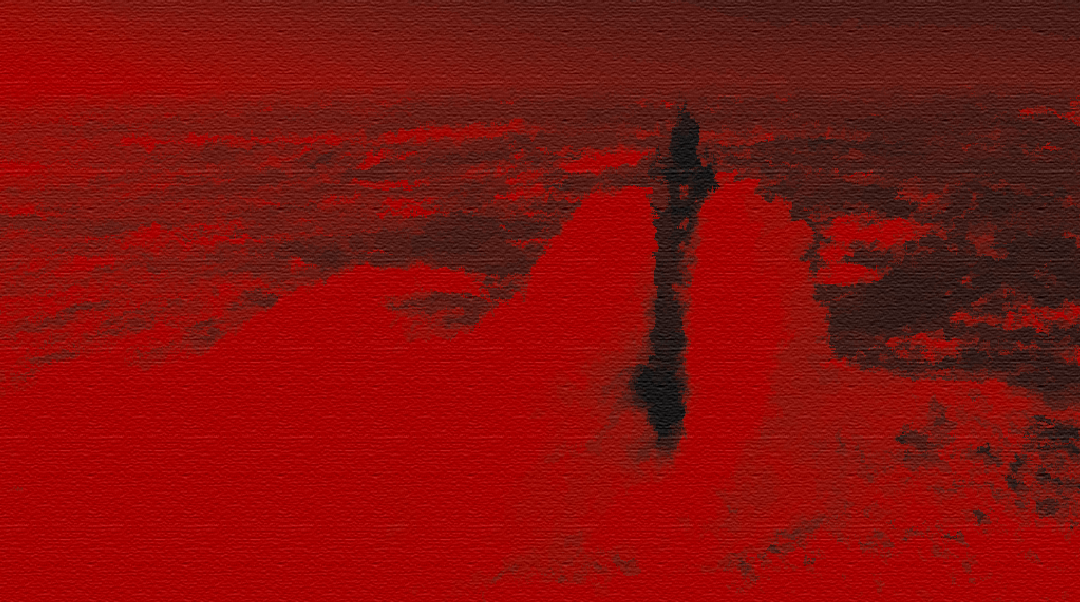

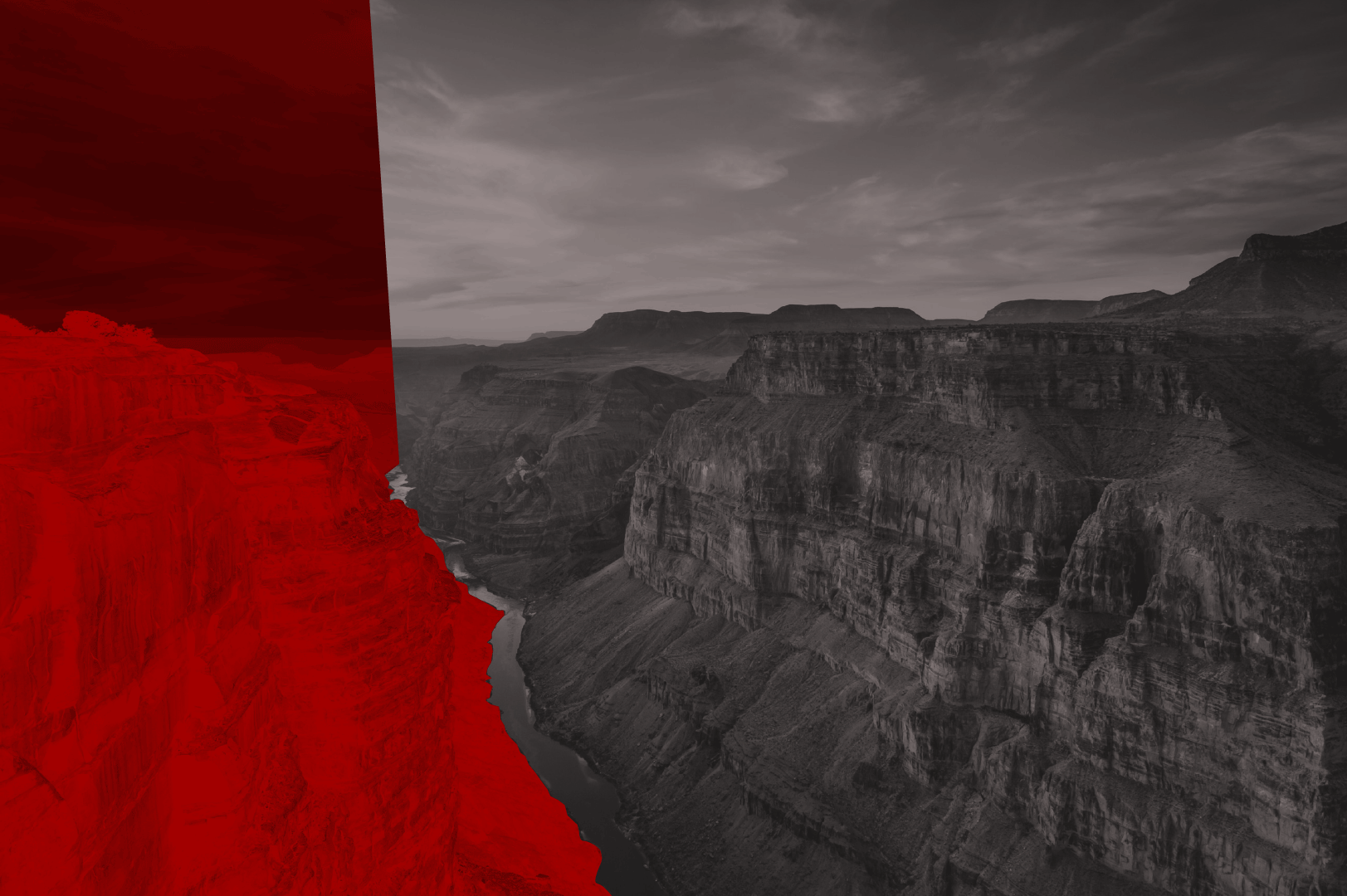

A symbolic painting of the successive mounting attacks against Bahá'u'lláh by Mírzá Yaḥyá and Siyyid Muḥammadf in 1865-1866, like the fierce, violent waves crashing against a lighthouse in the middle of a stormy ocean, unable to move the immovable, no matter the virulence of their attacks. © Violetta Zein.

During Bahá'u'lláh’s two-month seclusion, Mírzá Yaḥyá and Siyyid Muḥammad embarked on such a ferociously ill-willed smear campaign that the Bahá'ís were stunned. They wrote letters filled with vile slander, misrepresenting Bahá'u'lláh and accusing Him of everything Mírzá Yaḥyá had done, and distributed these poisonous letters widely among the believers in ‘Iráq and Persia.

Their letters caused so much confusion and division in the Bahá'í community that some lost their faith, others wrote to Bahá'u'lláh for guidance to which He responded, and still others, like Nabíl, rose up to defend the Bahá'í Faith.

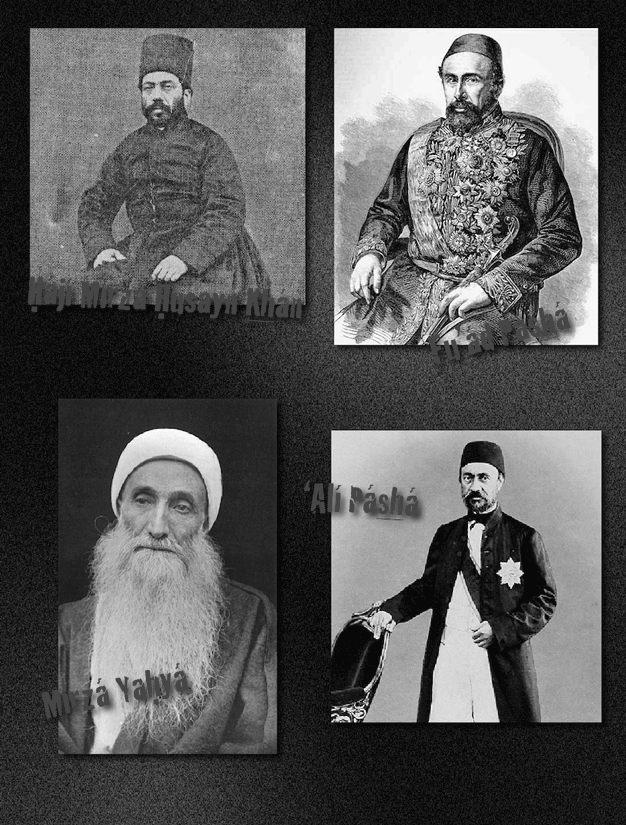

Mírzá Yaḥyá sent calumniating letters to Khurshíd Páshá, the Governor of Adrianople. Siyyid Muḥammad threw himself completely into a campaign of character assassination against Bahá'u'lláh, traveling to Constantinople and attempting to discredit Him in everyone’s eyes, especially those of the Persian ambassador.

Then, he accused Bahá'u'lláh, who had ensured he and Mírzá Yaḥyá were receiving their monthly government allowance, of withholding it and of hiring an assassin to kill Náṣiri’d-Dín Sháh.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 232-233.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868, pages 165-167.

An artistic interpretation of that final straw, the actions that ended Bahá'u'lláh's two-month seclusion © Violetta Zein.

Around May 1866, Mírzá Yaḥyá sent one of his wives to the government house complaining that Bahá'u'lláh had cut off her husband’s allowance, and that she and her children were on the verge of starvation. Siyyid Muḥammad made the same complaint to a Ṣúfí seminary, and was given tea, sugar, and necessities. This happened at the exact time that Mírzá Yaḥyá had received 2,000 túmáns from Qazvín. He and his malevolent entourage had never wanted for either food or money.

Mírzá Yaḥyá’s bold-faced lie about his allowance became a subject of heated discussions and insults directed at Bahá'u'lláh by the same people in Constantinople who had been so impressed with Him in 1863.

The final acts of Mírzá Yaḥyá were so shameful that Bahá'u'lláh decided to end His seclusion, saying: “We secluded ourselves, that perchance the fire of hostility might be quenched, and such disgraceful acts be averted, but they have resorted to measures more extreme than before.”

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 232-234

This graphic of three ravens, representing Mírzá Yaḥyá, Siyyid Muḥammad, and Kaj Kuláh, was inspired by a beautiful Tablet revealed by Bahá'u'lláh in Adrianople shortly after the Most Great Separation in May 1866, therefore around the time the events in the sections above and below take place. The Tablet is called Zágh va Bulbul (The Raven and the Nightingale). In Zágh va Bulbul, Bahá'u'lláh paints a delightful setting where a drama unfolds in which several figures dialogue. One the one had are the rose and the nightingale, symbolizing Bahá'u'lláh Himself, and on the other are birds disguised as nightingales, the unfaithful. Mírzá Yaḥyá and one of his followers appear respectively as the raven and the owl. References: Partial Inventory ID: BH01361; Adib Taherzadeh, The Covenant of Bahá’u’lláh, Chapter 9. Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868, pages 241-245. © Violetta Zein.

Soon after Bahá'u'lláh retired to the house of Riḍá Big following the Most Great Separation, Siyyid Muḥammad-i-Iṣfahání intensified his smear campaign against Bahá'u'lláh. He went to Constantinople and met with Ottoman officials and the Persian ambassador, Ḥájí Mírzá Ḥusayn-Khán, spinning a toxic web of lies, slander, and conspiracy theories. These despicable fabrications made their way in the hearts of those who listened, and played a significant role in Bahá'u'lláh's final, and strictest, exile to ‘Akká.

Siyyid Muḥammad's most loyal evil associate was Áqá Ján Big Kaj Kuláh, known as Kaj Kuláh (skew-cap), a Persian defector who had retired from the Ottoman army with the rank of Colonel in 1866. He had fallen under Siyyid Muḥammad's malignant spell, and would remain a disturbingly faithful ally to the bitter end.

Kaj Kuláh sent two petitions to the Prime Minister, ‘Alí Páshá and accompanied Siyyid Muḥammad to the Foreign Office to convince the Ottoman government that the monthly government allowance for the exiles should go to Mírzá Yaḥyá instead of Bahá'u'lláh.

Their deluge of petitions on the same subject had a surprising effect: when Bahá'u'lláh became aware of them, He never again perceived His share of the allowance, even selling some of His belongings to provide for the most basic necessities for His Family.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868, pages 325-328.

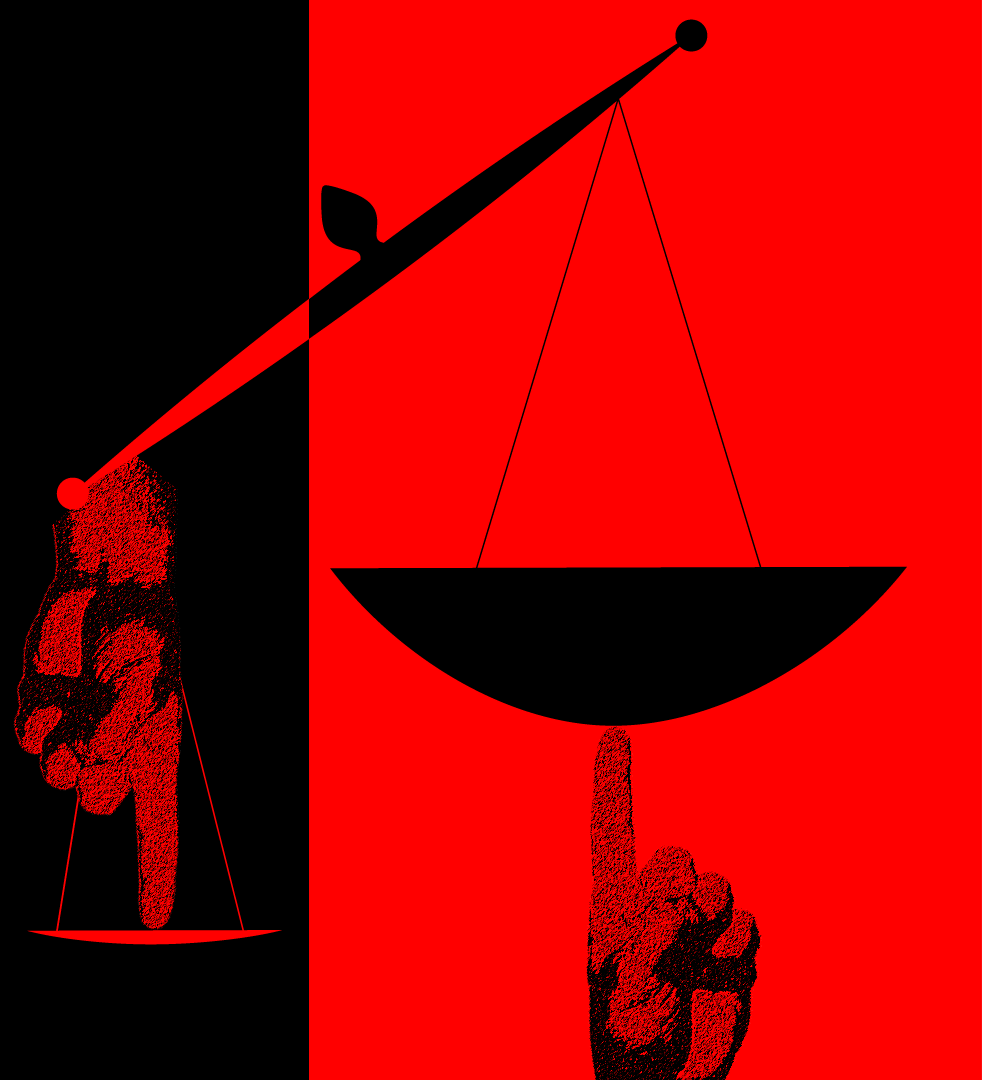

An artistic interpretation of the rift in the community, separating the Bahá'ís from the Azalís. © Violetta Zein.

When Bahá'u'lláh came out of seclusion, one of His first actions was to expel Siyyid Muḥammad-i-Iṣfahání from the gatherings of His followers. The Most Great Separation between Bahá'u'lláh and Mírzá Yaḥyá which had taken place in March 1866 was now an official division between the Bahá'ís, the followers of Bahá'u'lláh, and the Azalís, the followers of Mírzá Yaḥyá. The rift between the two communities became public knowledge.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868, page 170.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Covenant of Bahá’u’lláh, Chapter 4, paragraph [4-25].

Timeline showing the period between Bahá'u'lláh's seclusion from March to May 1866 and Mírzá Yaḥyá's lies about the government allowance in August 1867. © Violetta Zein.

Ásíyih Khánum had been so deeply concerned about Bahá'u'lláh’s safety since Mírzá Yaḥyá’s poisoning attempt, that the Most Great Separation was almost a relief. His evil presence would be kept at bay now that he had his own community.

Bahíyyih Khánum’s lovely form was worn away to a shadow because of the intense sorrow and oppressive trials of that year. Her immovable faith was a pillar of strength for the community and her sacrifice and exertion to serve at all times softened hardened hearts. The intense physical, spiritual and emotional hardships of the Most Great Separation would leave their mark on her angelic face until her passing.

Baharieh Rouhani Ma'ani, Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees, pages 106-107.

An abstract interpretation of diverging spiritual destinies, the choice Muḥammad 'Alí always had to develop spiritual capacities instead of sinking deeper into His faults. At a time when Bahá'u'lláh had declared and proclaimed His station as the Supreme Manifestation of God, Muḥammad 'Alí claimed the station of prophethood while ‘Abdu'l-Bahá claimed the mantle of servitude and refused to pick up a pen and answer in His own hand while Bahá'u'lláh was alive and Revealing divine verses. © Violetta Zein.

In his childhood, Bahá'u'lláh conferred upon His son from His second wife, Mírzá Muḥammad ‘Alí the power of utterance as a proof of His own power and glory. Muḥammad ‘Alí would corrupt this divine bounty from an early age, choosing to use his power to further his personal ambitions instead of furthering the Cause of God, its intended goal. In Adrianople, when he was around 13 to 15, Muḥammad ‘Alí composed and widely distributed a series of extremely lengthy passages in Arabic advancing blasphemous claims, referring to himself as “the King of the spirit,” calling on the believers to “hear the voice of him who has been manifested to man,” rebuking those who deny his childhood verses, elevating His revelation as “the greatest of God's revelations,” affirming that “all have been created through a word from him,” painting himself as “the greatest divine luminary before whose radiance all other suns pale into insignificance,” and appointing himself “the sovereign ruler of all who are in heaven and on earth.”

During this same time, 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s behavior was diametrically opposite to that of His unfaithful half-brother. Out of respect to Bahá'u'lláh, whose outpour of Revelation was constant, He never responded to letters addressed directly to Him unless ordered to do so by Bahá'u'lláh, generally after complaints from Persian believers who were not receiving an answer.

Muḥammad ‘Alí’s prominent display of personal ambition provoked Bahá'u'lláh’s wrath, Who vehemently rebuked His unfaithful son and chastised him with His own hands. Muḥammad ‘Alí’s claims also created great controversy and disunity in the Bahá'í community of Qavín, weakened and divided thanks to Mírzá Yaḥyá’s efforts, and one of the Bahá'ís, Khalíl, wrote to Bahá'u'lláh begging for clarification regarding His station and that of His sons. Bahá'u'lláh responded by revealing the Lawḥ-i-Ibná (Tablet of the Sons), in which He makes His own station perfectly clear and alludes to 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s in exalted terms as the One “from Whose tongue God will cause the signs of His power to stream forth,” and Whom “God hath specially chosen for His Cause,”

In two untranslated Tablets revealed around this time, Bahá'u'lláh leaves no doubt as to Muḥammad ‘Alí’s rank: "He, verily, is but one of My servants…should he for a moment pass out from under the shadow of the Cause, he surely shall be brought to naught,” and more emphatically: “By God, the True One! Were We, for a single instant, to withhold from him the outpourings of Our Cause, he would wither, and would fall upon the dust.”

Fueled by his intense jealousy of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, itself exacerbated by his enormous ambition and complete lack of spiritual qualities, Muḥammad ‘Alí would spend the rest of his life trying to undermine 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s position as Center of the Covenant only gaining himself a place in Bahá'í history as the Arch-breaker of the Covenant of Bahá'u'lláh.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Covenant of Bahá'u'lláh, Chapter 8: The Arch-breaker of Bahá'u'lláh's Covenant.

Wikipedia: Mírzá Muhammad ʻAlí.

SOURCES FOR TABLETS

Lawḥ-i-Ibná

Partial Inventory ID: BH00431

An excerpt from this Tablet was translated by Shoghi Effendi and can be found in Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá'u'lláh selections N° LXXVII.

Two untranslated Tablets about Muḥammad ‘Alí

Partial Inventory ID: BH06114

Partial Inventory ID: BH00941

The two verses, one from each Tablet, quoted in the story above were translated by Shoghi Effendi in God Passes By, page 251.

DATE

Muḥammad ‘Alí was born in 1853 and was 10-15 years old in Adrianople. Adib Taherzadeh states that this episode with Muḥammad ‘Alí occurred in Adrianople in Muḥammad ‘Alí’s early teenage years, a period which starts at the age of 13. Taking into consideration 14 was considered the age of maturity at the time, it is likely this took place sometime between 1866 and 1868 when Muḥammad ‘Alí was 13-15 years old.

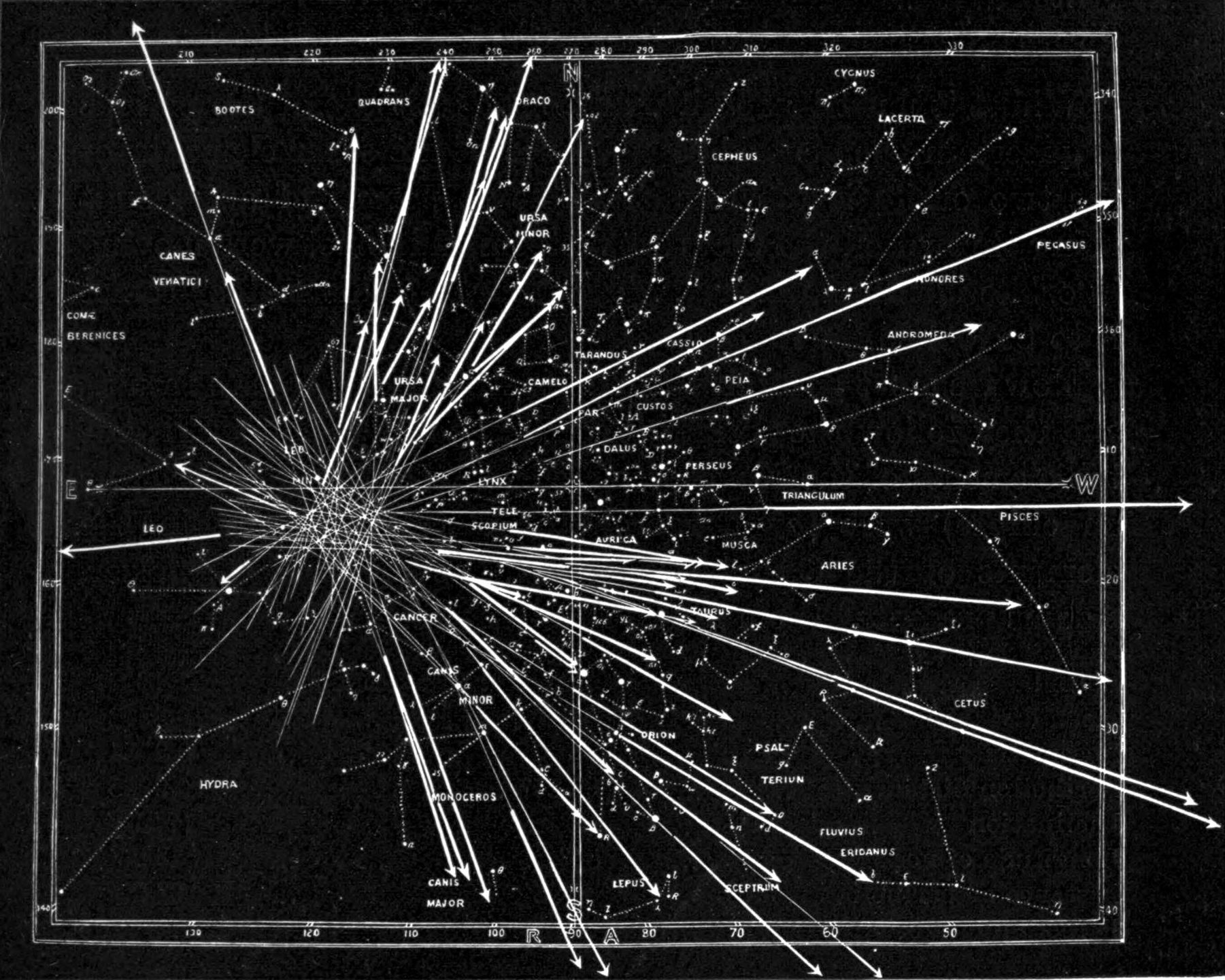

The Star-fall of 14 November 1866: Tracks of meteors seen at Greenwich, England. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

One day after Bahá'u'lláh’s birthday, from around 11 PM on 13 November 1866 to the early morning hours of 14 November, the “stars” fell in the skies above Europe and Asia. Thousands of observers from all walks of life—astronomers, noblemen, common folk, officers, the clergy, laymen, clerks and even Queen Victoria in London and Bahá'u'lláh in Adrianople, gathered on rooftops, in fields, lanes, thoroughfares, and open spaces, to look up at the night-sky and witness the spectacular Leonid meteor shower, dubbed the "Star-fall of 1866."

It was the first time in history that astronomers had correctly predicted the spectacle of the Leonid meteor shower. By 1 in the morning, the meteors were falling at a rate of two per second, too fast for anyone to keep count of.

The Illustrated London News commented in its Editorial of 17 November 1866:

“Myriads…will look back to the great night of 1866, when the heavens were full of fiery shapes, and from around the Lion the mystic bolts shot fierce and fast, and a sense of something preternatural silenced the least reverent into awe.”

The event was watched by millions in the East and in the West, and for many of those observers, the experience was truly terrifying. One of the prophecies of the Gospels is that the falling of the stars is one of the signs of the second coming of Christ, in the glory of the Father. Many of those watching these thousands of shooting stars, more than any had ever seen in their lives, did not know if it was the end of an era or a sign from heaven.

The Star-fall of November 1866 followed the Most Great Separation and was prophesied in the Bible, in Matthew 24: 29-31:

"Immediately after the tribulation of those days shall the sun be darkened, and the moon shall not give her light, and the stars shall fall from heaven, and the powers of the heavens shall be shaken: And then shall appear the sign of the Son of man in heaven: and then shall all the tribes of the earth mourn, and they shall see the Son of man coming in the clouds of heaven with power and great glory. And he shall send his angels with a great sound of a trumpet, and they shall gather together his elect from the four winds, from one end of heaven to the other."

And Bahá'u'lláh Himself speaks of this Star-fall's significance in two passages in Epistle to the Son of the Wolf:

“O King! The stars of the heaven of knowledge have fallen, they who seek to establish the truth of My Cause through the things they possess, and who make mention of God in My Name…This is, truly, that which the Spirit of God (Jesus Christ) hath announced, when He came with truth unto you…”

And again:

"’Have the stars fallen?’ Say: ‘Yea, when He Who is the Self-Subsisting dwelt in the Land of Mystery (Adrianople). Take heed, ye who are endued with discernment!’ All the signs appeared when We drew forth the Hand of Power from the bosom of majesty and might."

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868, pages 270-272, and Appendix I: The Star-Fall of 1866, pages 422-426.

Ḥájí Mírzá Ḥayar-‘Alí, Stories from the Delight of Hearts, page 87.

Brandon Jackson, Looking Up At The Falling Stars of 1866, pages 1, 2, and 15.

Wikipedia: Leonids.

The Bible, King James Version, Matthew 24: 29-31.

Bahá'u'lláh, Epistle to the Son of the Wolf: The stars of the heaven of knowledge have fallen, Have the stars fallen?

The house of Riḍá Big in Adrianople (now Edirne). This is the house of Bahá'u'lláh in Edirne which Bahá'ís can now visit. Source: Bahaipedia.

Bahá'u'lláh lived in the house of Riḍá Big during His retirement from the community for about a year, from 10 March 1866 to March 1867, pulled out of His seclusion by Mírzá Yaḥyá's actions.

The house of Riḍá Big, like the house of Amru’lláh, had a bírúní which was smaller than the andáruní but had a large courtyard and a garden planted with a variety of trees and flowers, where Bahá'u'lláh would pace and speak with His followers. Bahá'u'lláh would also sometimes visit the rented Murádíyyih garden for an hour or two.

A modern view of the garden in the house of Riḍá Big. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 235-236.

The ruins of the house of Amru'lláh taken in 1933. At the present time there are buildings where the house partially covering where the house used to stand. Caption details provided by Mr. Mohssen Madjidi. Source: The Bahá'í World Volume V (1932-1934), Martha Root: A visit to Adrianople, page 587.

Leaving the house of Riḍá Big, Bahá'u'lláh lived for about three months in the house of ‘Amru’lláh, which had just been vacated, until about September 1867.

When Bahá'u'lláh ended His seclusion, the Bahá'ís rented a house near Him. Their house had a well with good water and a large courtyard with plenty of flowers. The believers took turns with the chores each day, doing all the gardening, cooking, preparing the tea, washing the dishes for their housemates. 'Abdu'l-Bahá and Mírzá Mihdí regularly visited them and Bahá'u'lláh sometimes came, speaking at their gatherings and even at times revealing Tablets in their house.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 235-236.

1933 photograph showing the ruins of the Turkish bath belonging to the house of 'Izzat 'Áqá. The house itself is on the right side of the picture. The long building to the left, extending towards the background is a school building and not part of the House of 'Izzat 'Áqá. Caption details provided by Mr. Mohssen Madjidi.Source: The Bahá'í World Volume V (1932-1934), Martha Root: A visit to Adrianople, page 587.

Bahá'u'lláh and the Holy Family moved into the house of 'Izzat Áqá after three months in the house of Amru’lláh, possibly around June 1867. This was a newly-built house, and boasted a beautiful view of the river and the southern orchards of Adrianople.

The rooms in the house were vast, the bírúní was smaller than the andáruní, but they were both large enough and each had a large tree-filled courtyard with flower beds.

During this time, the outpour of Bahá'u'lláh’s Revelation was so prolific, that Mírzá Áqá Ján and the sons of Bahá'u'lláh spent long days and nights copying Tablets. Again, Bahá'u'lláh’s companions soon moved into a house nearby that was large enough to accommodate them all and equipped with a Turkish bath, where they were able to host Bahá'í pilgrims.

A modern view of the garden of the house of 'Izzat Áqá. Photo courtesy of Mr. Mohssen Madjidi.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 241 and 249.

Anthony A Reitmayer, Adrianople: Land of Mystery, page 42.

An abstract representation of the feeling of loss, in honor of Bahá'u'lláh's great loss recounted below. This digital composite painting was created sampling portions of two 19th century public domain paintings from The Met: Beach Scene by James Hamilton (ca. 1865) and The Lake of Zug by Joseph Mallord William Turner (1843). © Violetta Zein.

In the midst of so much turmoil and tribulation, Bahá'u'lláh suffered a very great personal tragedy. His dearly beloved cousin Maryam, who had nursed Him back to health after the Siyáh-Chál, passed away in Ṭihrán on 7 August 1867, at the age of 42.

After Bahá'u'lláh left Persia, Maryam served the Faith with intense devotion and kept in regular contact with Him for 14 years through correspondence. Bahá'u'lláh revealed many significant Tablets to Maryam, and poured His heart out to her, in Tablets that have a unique tone of intimacy and affection. They were extremely close, and she was almost able to come and visit her beloved Cousin in Baghdád, when malevolent family members prevented her from leaving. It is believed Maryam made several more attempts to visit Bahá'u'lláh, the last one shortly before her passing.

Bahá'u'lláh revealed a Tablet of Visitation for Maryam, addressing her as Varaqatu'l-Baqá'íyyih (Leaf of Eternity) and Maryam as Al-Mustashhad fï sabíli'l Bahá (The one who died as a martyr in the path of Bahá), recounting her life and sufferings and shedding light on her very great station: “We concealed her station during her lifetime. When she ascended to the Highest Horizon, God removed the veil and made her known to His servants.”

Baharieh Rouhani Ma'ani, Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees, pages 296-305.

DATE

Ishráq-i-Khávarí notes 6 Rabí'uth-Thání 1284 A.H. as the date for Maryam’s passing, converted on Habibur Islamic Hijiri Calendar, this gives a Gregorian date of 7 August 1867.

The original mubáḥilih (or mubahala), the confrontation between Christians from Najran and the prophet Muḥammad, in the month of Dhu'l-Hijja, 10 AH (October 632). Source: Kuntshistorisches Institut in Florenz.

In September 1867, when Bahá'u'lláh was living in the house of Izzat Áqá, an extremely important event took place.

Mír Muḥammad-i-Mukarí (driver of beasts of burden) was a Bábí from Shíráz, and simply could not imagine that Mírzá Yaḥyá, the nominee of the Báb, had broken the Báb’s Covenant. He begged Bahá'u'lláh to enlighten him, and Bahá'u'lláh responded that if Mírzá Yaḥyá came face to face with Him in a public meeting, a mubáhilih, then his claim could be considered the truth. Satisfied with the fairness of this proposition, Mír Muḥammad arranged the meeting.

Mubáhilih (the literal meaning is imprecation, or spoken curse) is a historical meeting between the Prophet Muḥammad and a Christian delegation to determine the truth of His claim. Mubáhilih can also mean withdrawing mercy from someone who lies or deceives.

Thinking that Bahá'u'lláh would never come to such a meeting, Mírzá Yaḥyá set the meeting place at the mosque of Sulṭán Salím for Friday, at the time of the congregational prayer, when the mosque would be filled with a large number of people.

Wikipedia: Event of Mubahala.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868, pages 295-596.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Covenant of Bahá’u’lláh, Chapter 5.

Aerial view of the mosque of Sulṭán Salim (Selimiye mosque) showing the general area that Bahá'u'lláh walked through like a king on his way to publicly confront Mírzá Yaḥyá. Source: Research Gate.

The date and time of the mubáhilih (public confrontation) between Bahá'u'lláh and Mírzá Yaḥyá leaked to the general public, and everyone was impatient for the standoff between “His Holiness Shaykh Effendi” (Bahá'u'lláh) and “Mírzá ‘Alí” (another one of Mírzá Yaḥyá’s fake names), who had rejected Him.

On Friday, the crowd’s impatience was palpable. From morning until noon, a huge crowd of Muslims, Christians, and Jews lined the streets from the house of Amru’lláh to the mosque of Sulṭán Salím. The crowd was so large, it was difficult to move about.

Bahá'u'lláh emerged from the house of 'Izzát Áqá around noon, and as He passed under the mid-day sun, accompanied by Mír Muḥammad, people showed Him reverence fit for a King. They greeted Him with salutations and bowed, opening the way for Him to advance through the crowd. Many kneeled to kiss His feet, and Bahá'u'lláh, radiating divine majesty and power, greeted the people by raising His hands and offering His good wishes, as He made His way to the Mosque of Sulṭán Salim.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868, pages 295-596.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Covenant of Bahá’u’lláh, Chapter 5.

© Violetta Zein.

During His long walk to the mosque, Bahá'u'lláh recited verses in a voice and in a manner that astonished those who heard Him. As testified by Bahá'u'lláh Himself, one of the verses He revealed on this critical day was an excerpt from the Lawḥ-i-Mubáhilih (Tablet of the Confrontation), revealed sometime between August and September 1867, and which states: "Say: Were all the divines, all the wise men, all the kings and rulers on earth to gather together, I, in very truth, would confront them, and would proclaim the verses of God, the Sovereign, the Almighty, the All-Wise. I am He Who feareth no one, though all who are in heaven and all who are on earth rise up against me."

The Lawḥ-i-Mubáhilih had a profound effect on Persian believers and caused wavering souls to fully recognize and accept Bahá'u'lláh's power and majesty.

Partial Inventory ID: BH00457

Bahá’u’lláh, Lawḥ-i-Mubáhilih (Tablet of the Confrontation) (Only translated in God Passes By), originally addressed to Mullá Sádiq-i-Khurásání, this Tablet praises the station of Quddús but more importantly narrates the circumstances of the public challenge with Mírzá Yaḥyá.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868, pages 295-596.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Covenant of Bahá’u’lláh, Chapter 5.

© Violetta Zein.

At last, Bahá'u'lláh and Mír Muḥammad reached the mosque of Sulṭán Salím. As soon as Bahá'u'lláh entered the mosque, the imám who was delivering his discourse became speechless. Bahá'u'lláh came forward, sat down, and asked the imám to continue. Once the afternoon prayer had ended, it was clear Mírzá Yaḥyá would not show, and he sent word that he felt ill, and requested a delay of a day or two for the meeting.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868, pages 295-596.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Covenant of Bahá’u’lláh, Chapter 5.

The devotional dances of the Mawlvís, more commonly known as "whirling dervishes" inside the Temple at Pera in Constantinople in 1796, engraving by Calvert Frederick. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

As Bahá'u'lláh was about to leave the mosque, He said: “We owe a visit to the Mawlavís. We had better go to their takyih.” The Mawalvís, more commonly known as the “whirling dervishes” were a Ṣúfí community, followers of Mawlavi, also known as Rúmí, the 13th century Ṣúfí poet and author of the Masnavi.

As Bahá'u'lláh started heading to the takyih, the Ṣúfí center, the Shaykhu'l-Islám (head of the Muslim ecclesiastical institution in Adrianople), ulámá (learned Muslim divines) and other dignitaries, accompanied Him, walking a few steps behind, out of respect.

When Bahá'u'lláh arrived, the Shaykh of the whirling dervishes was standing in the center of the takyih, and the dervishes were circling around him, chanting. As soon as they saw Bahá'u'lláh, they instantly stopped their Friday service, they bowed respectfully and became absolutely silent. Bahá'u'lláh took a seat, and asked others to be seated as well, then gave the Shaykh permission to resume his service.

Wikipedia: Mevlevi Order.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868, pages 296-297.

© Violetta Zein.

These events were widely circulated in Adrianople at the time. It was reported in the news that, when “Shaykh Effendi” (Bahá'u'lláh) had entered the mosque, the preacher had been unable to continue delivering his sermon, and when He had entered the takyih, the speechless dervishes had stopped their service.

The very next evening, Bahá'u'lláh’s companions gathered around Him and Bahá'u'lláh made the following remark: “When We entered the crowded mosque, the preacher forgot the words of his sermon, and when We arrived inside the takyih, the dervishes were suddenly filled with such awe and wonder that they became speechless and silent. However, since people are brought up in vain imaginings, they foolishly consider such events as supernatural acts and regard them as miracles!'"

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868, pages 296-297.

© Violetta Zein.

When Bahá'u'lláh had returned to the house of Izzat Áqá, He revealed a Tablet addressed to Mírzá Yaḥyá and transcribed down by 'Abdu'l-Bahá, recounting what had just happened, and fixing a date and time for a new meeting.

Bahá'u'lláh sealed the Tablet with His seal and asked Nabíl to deliver it to one of the new believers, a shopkeeper, who was to hand it to Siyyid Muḥammad. Upon receiving it, Siyyid Muḥammad had been instructed to provide a sealed pledge from Mírzá Yaḥyá stating that if he did not appear at the second meeting, his claims to Revelation were false.

Siyyid Muḥammad refused delivery of Bahá'u'lláh’s Tablet, promising to produce the pledge the next day but he never returned and Bahá'u'lláh’s Tablet was never delivered.

Mírzá Yaḥyá would later claim that Bahá'u'lláh had never shown up to the first meeting, but he had lost face in front of the crowd of witnesses that saw Bahá'u'lláh at the mosque.

The mubáhilih had demonstrated Bahá'u'lláh's supremacy and Mírzá Yaḥyá's cowardice and public humiliation. Nabíl kept that unopened Tablet, the blatant proof of Mírzá Yaḥyá's failure, unsealed and fresh as the day it was penned, for 23 years.

According to Shoghi Effendi, the dramatic downfall of Mírzá Yaḥyá was, prophesied by Saint Paul in 2 Thessalonians Chapter 2, Verses 3-4 and 8: “Let no man deceive you by any means: for that day shall not come, except there come a falling away first, and that man of sin be revealed, the son of perdition; Who opposeth and exalteth himself above all that is called God, or that is worshipped; so that he as God sitteth in the temple of God, shewing himself that he is God...And then shall that Wicked be revealed, whom the Lord shall consume with the spirit of his mouth, and shall destroy with the brightness of his coming”

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868, pages 294-296.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 239-242.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Covenant of Bahá’u’lláh, Chapter 5.

The Bible, King James Version: 2 Thessalonians 2: 3-4.

The Bible, King James Version: 2 Thessalonians 2: 8.

Timeline showing the period of intense opposition after the Most Great Separation, when knowledge about the division in the community was confined to the believers to the Public Confrontation and the division becoming public knowledge, all of which immediately preceded one of the most glorious periods of Bahá'u'lláh's ministry, the first phase of His public Proclamation to the kings and rulers of the world. © Violetta Zein.

Shortly after Mírzá Yaḥyá's complete debacle in the public confrontation, it was clear the division was permanent, and Bahá'u'lláh cast Mírzá Yaḥyá, "The Most Great Idol," out of the Bahá'í community, sealing his eternal fate as the Arch-breaker of the Báb's Covenant, and marking a dramatic conclusion to the Most Great Separation.

After the events of the previous months, including His majestic bearing during the mubálihih, Bahá'u'lláh had earned the admiration and respect of the population of Adrianople and the unquestioned allegiance of the Bahá'ís.

In the life of Bahá'u'lláh, victory follows crisis, and after the fire of tests, the floodgates of Revelation were flung wide open. Immediately after the Most Great Separation, in September 1867, Bahá'u'lláh revealed the weightiest Tablet of His entire time in Adrianople: The Súriy-i-Múlúk, (Surah of Kings). Following this mighty Tablet, a downpour of Revelation flowed from Bahá'u'lláh's lips like an onrushing torrent. The Proclamation of Bahá'u'lláh to the kings and rulers of the world had begun.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Juan Cole, The Azálí-Bahá'í Crisis of September 1867.

“The curtain now rises on what is admittedly the most turbulent and critical period of the first Bahá’í century—a period that was destined to precede the most glorious phase of that ministry, the proclamation of His Message to the world and its rulers.”

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By

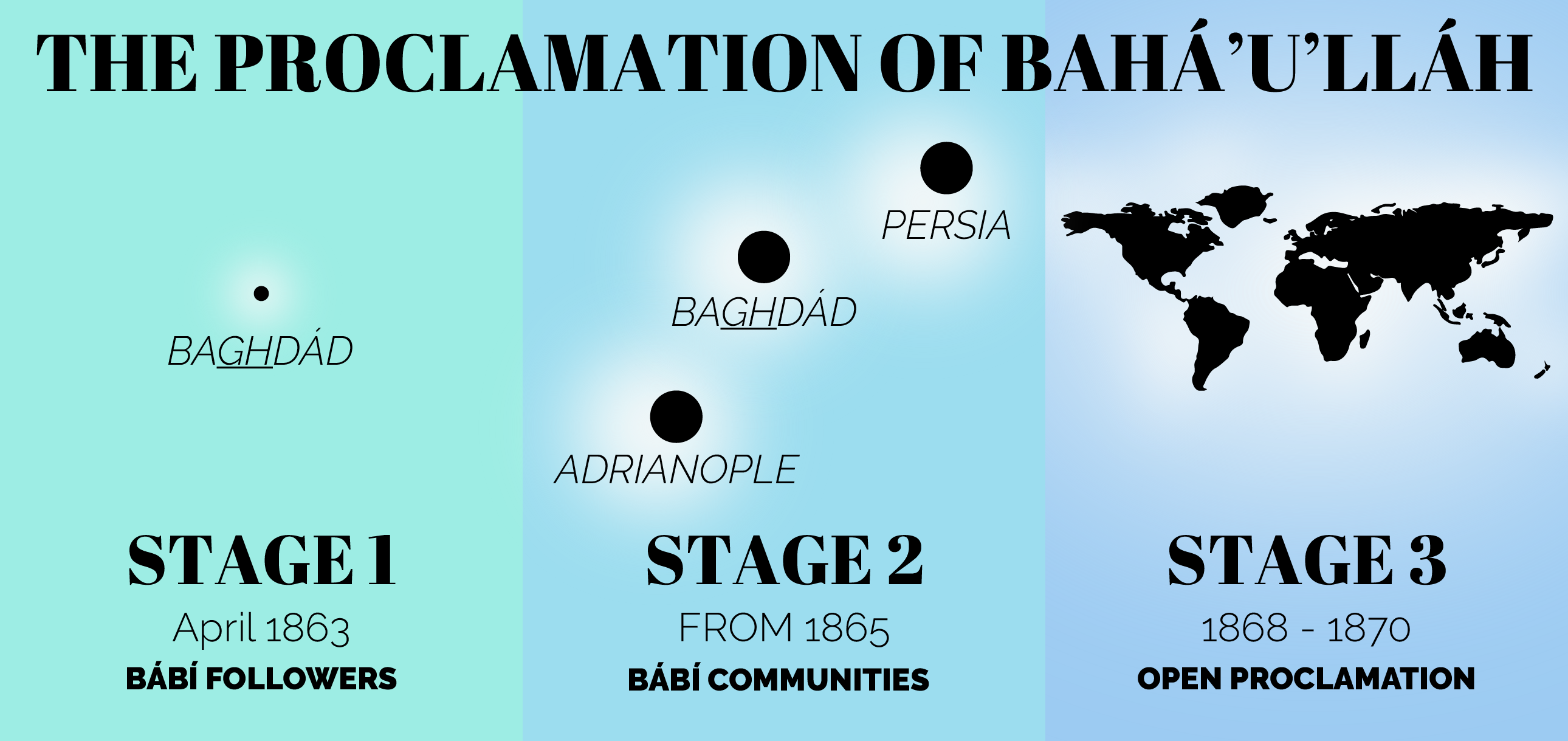

The three stages of the Proclamation of Bahá'u'lláh, from Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 2, pages 301-303. © Violetta Zein.

Bahá'u'lláh’s Proclamation as “He Whom God shall make manifest” was unfolded in three stages, with the Súriy-i-Múlúk marking the beginning of the third stage:

- The first stage, in April 1863, was Bahá'u'lláh’s Declaration in the Garden of Riḍván to His followers alone, and His announcement of the Advent of the Day of God;

- The second stage, starting in 1865, was Bahá'u'lláh’s Proclamation to the Bábí communities of Adrianople, Baghdád and Persia through various proclamatory Tablets;

- The third and final stage, Bahá'u'lláh’s Proclamation to the world at large, took place from 1868 to 1870. The first phase took place in Adrianople and Káshánih, and the second phase unfolded in the Most Great Prison. In Bahá'u'lláh’s public Proclamation, He boldly asserts His claim as the Manifestation of God for today to kings, queens, the pope, the Sháh, the Sulṭán,to the President of the United States and its Republics, to all monarchs and rulers of the world, to members of Parliament, to religious leaders of Christianity, Judaism, Islám and Zoroastrianism, to the Bábís (the Azalís), to the peoples of the world, to philosophers and academics, and to the inhabitants of individual countries or cities.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868, pages 301-303.

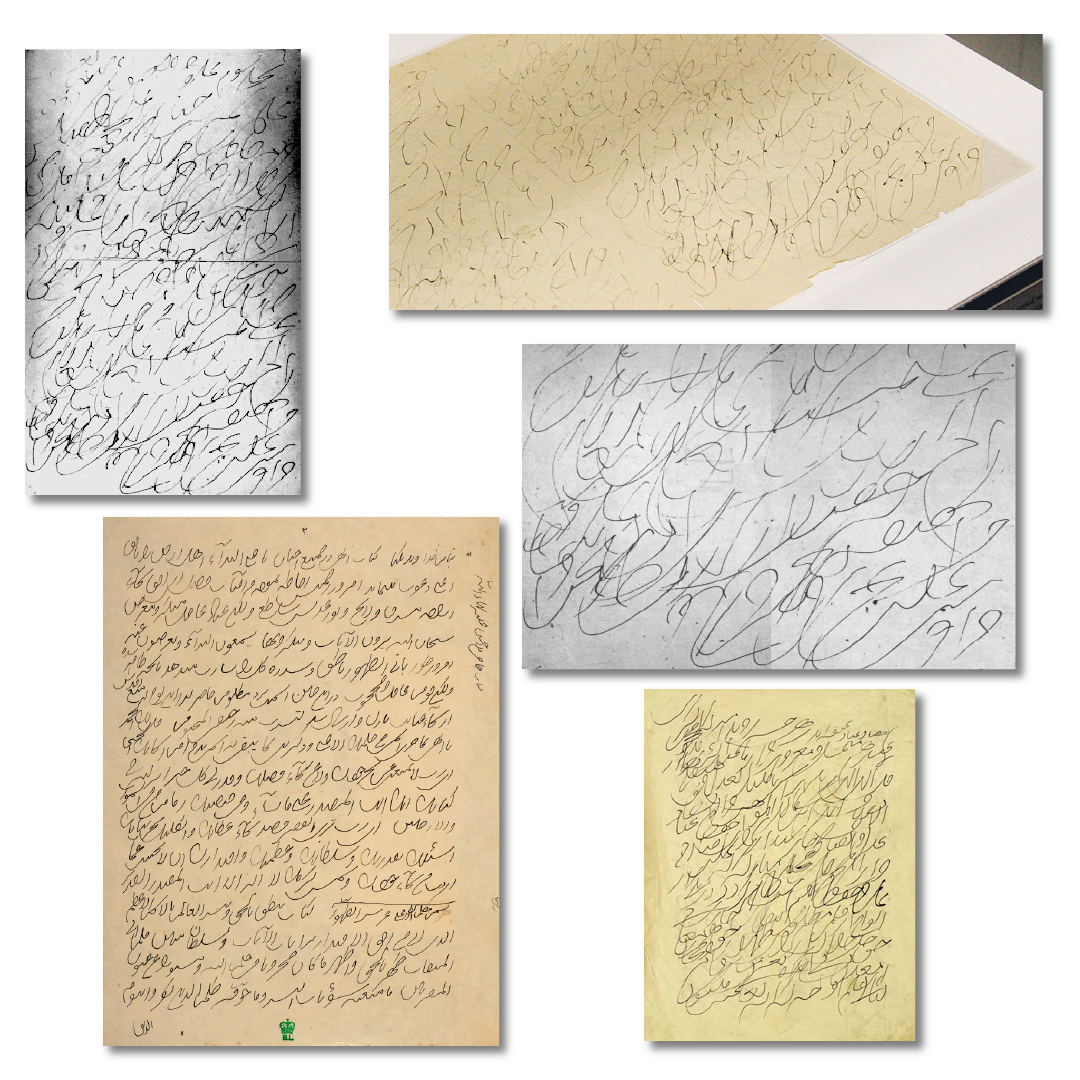

In an effort to illustrate the extraordinary outpour of divine Revelation during this fecund period in Bahá'u'lláh's ministry, a collage of five images depicting the shorthand known as "Revelation Writing", almost illegible to anyone but Bahá'u'lláh and Mírzá Aqá Ján. Details for the images are in the links provided. Sources: Bahá'í Sacred Relics, British Library, Bahá'í Teachings, Bahá'í Media, and Bahá'í Media.

Bahá'u'lláh’s eleven remaining months in Adrianople, in the house of ‘Izzat Áqá, from September 1867 to August 1868, constitute the most prodigiously prolific period in the entirety of His forty-year ministry. Tablets, epistles, and verses flowed continuously from His pen and His tongue, at times so prolific and at such speed that Bahá'u'lláh's amanuensis could not copy them down.

For six or seven months, several highly-skilled secretaries worked 24 hours a day and still could not keep up. At times, Bahá'u'lláh revealed 1,000 verses an hour. A single secretary's output in that time was 20 volumes. An eyewitness described this prolific time:

“Day and night, the Divine verses were raining down in such number that it was impossible to record them. Mírzá Áqá Ján wrote them as they were dictated, while the Most Great Branch was continually occupied in transcribing them. There was not a moment to spare.”

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 243-244.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868, page 397.

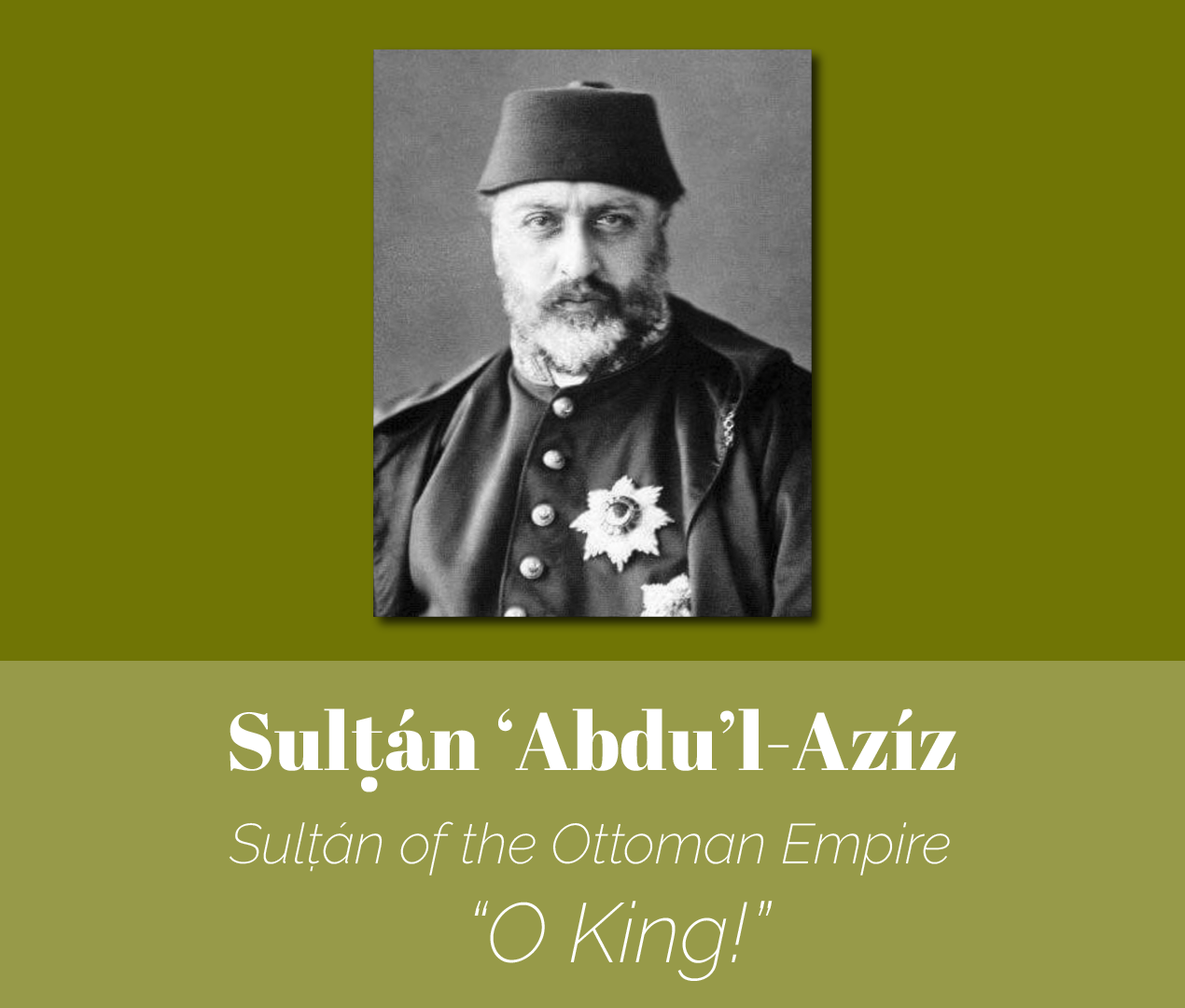

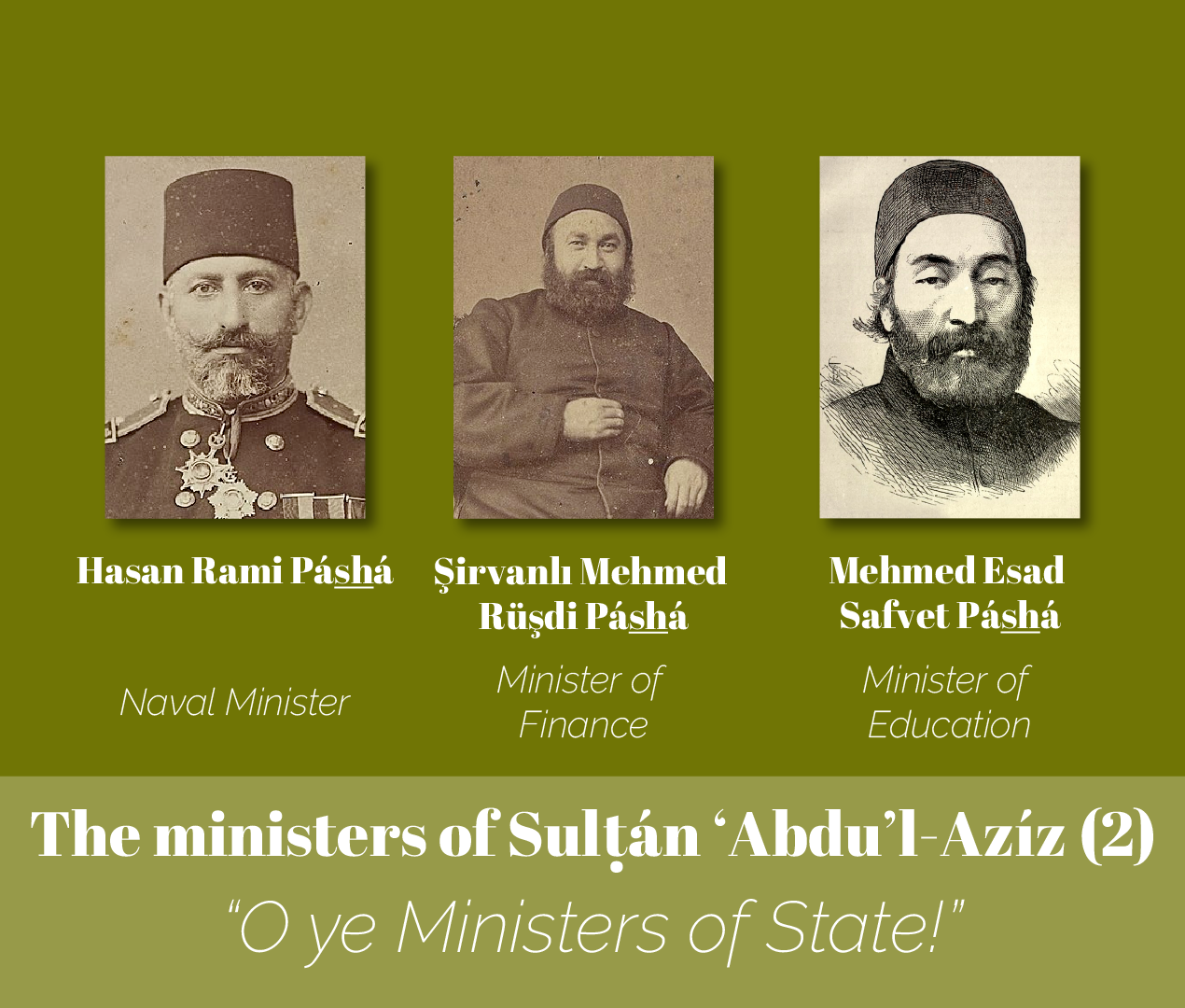

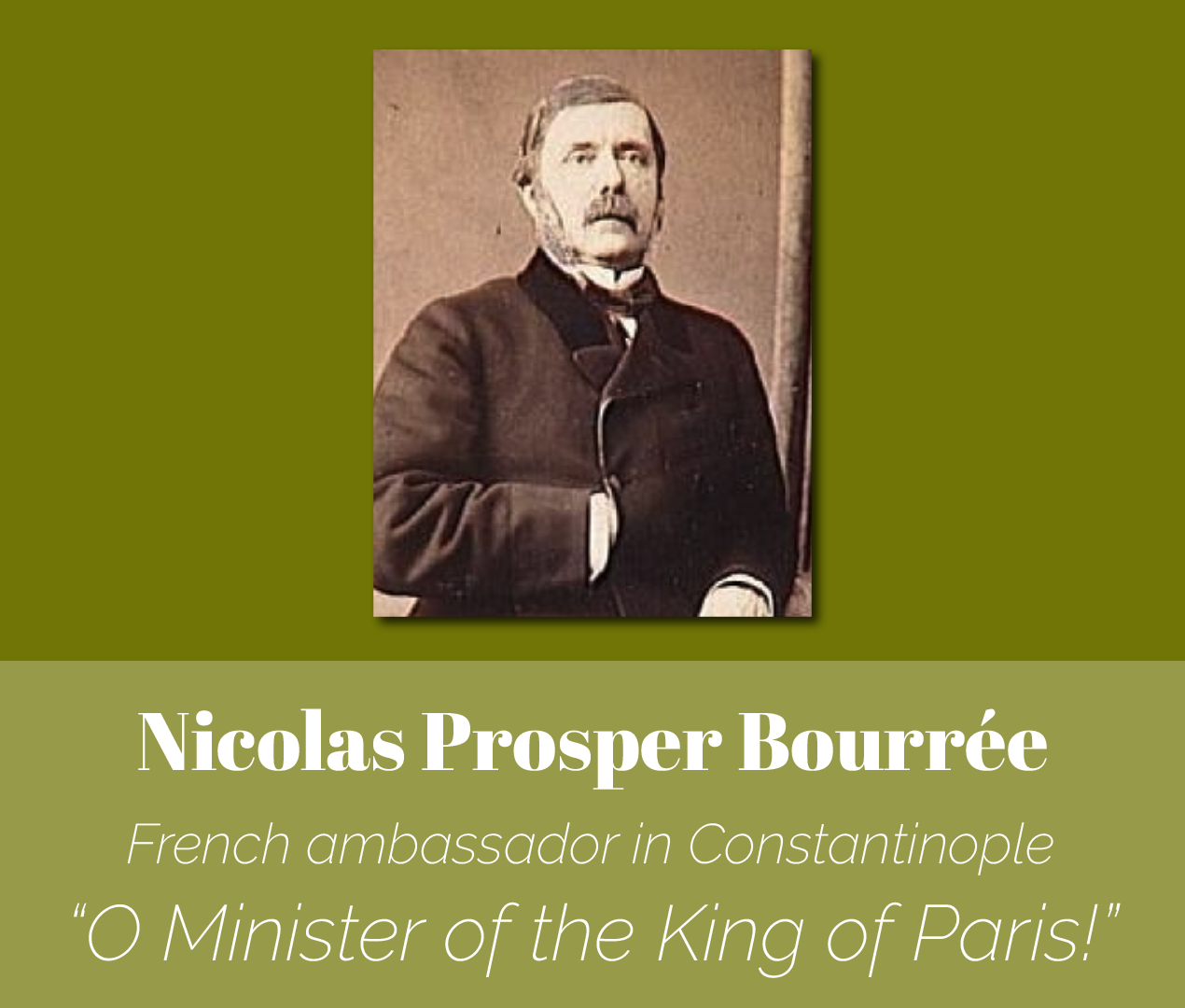

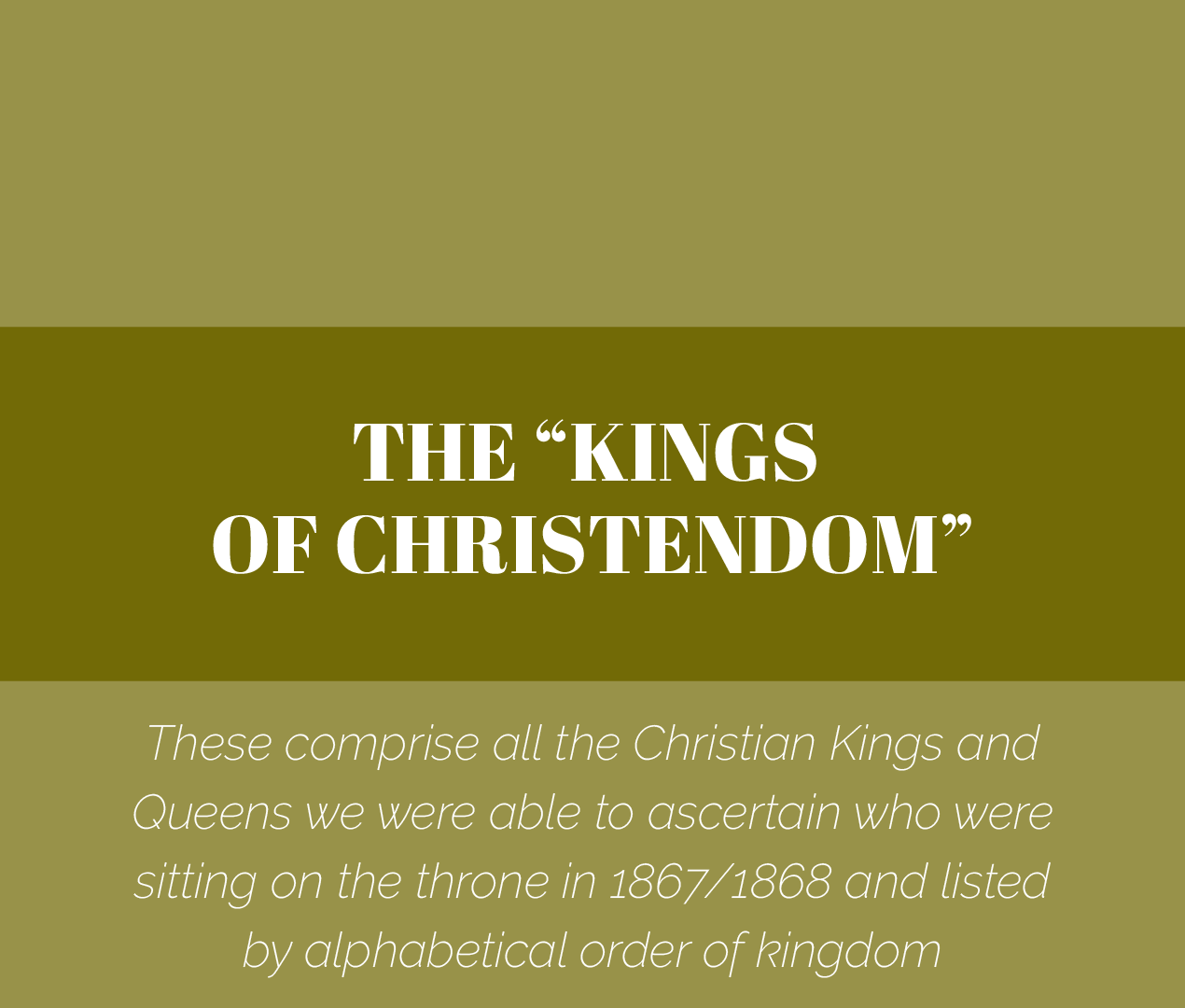

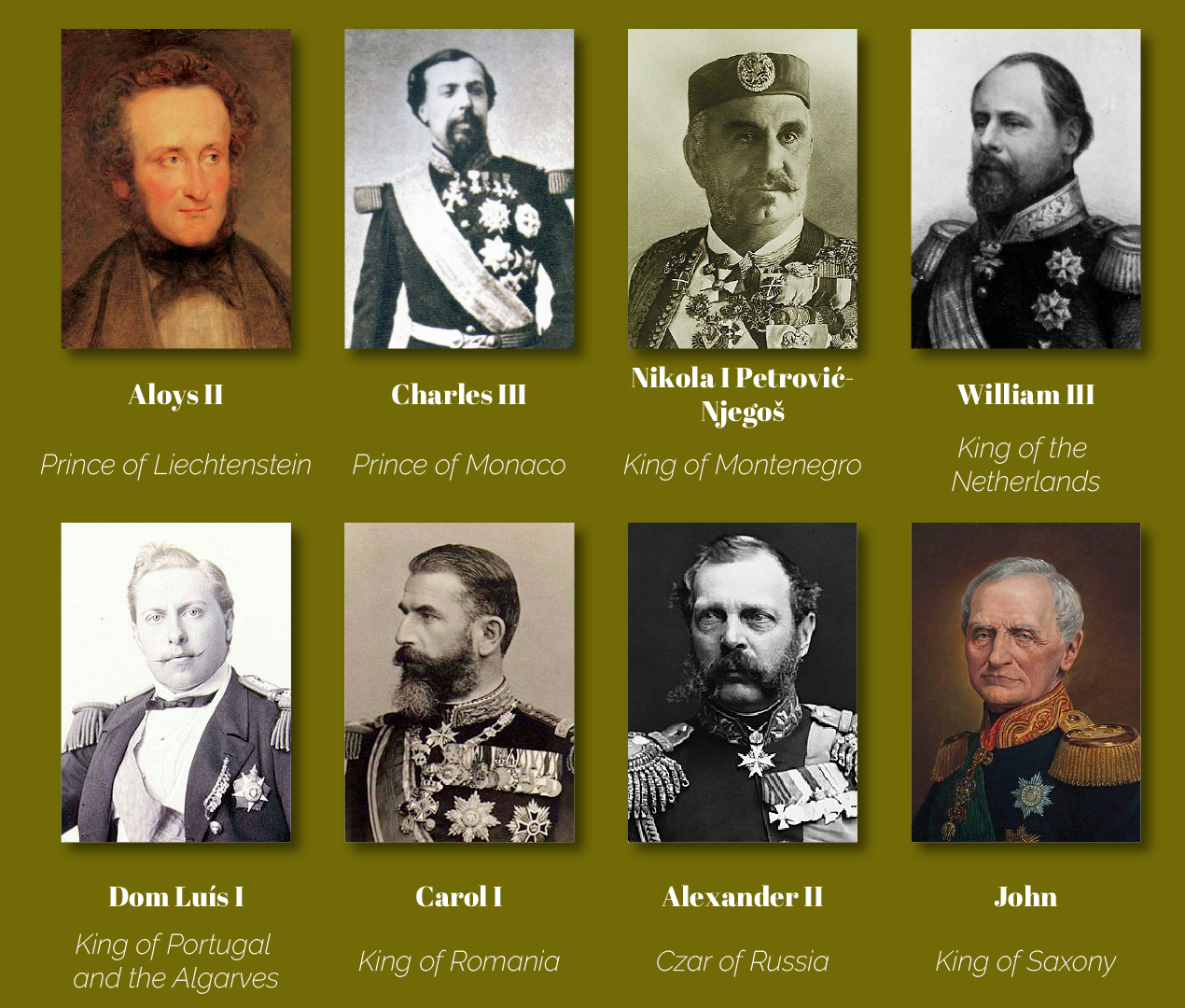

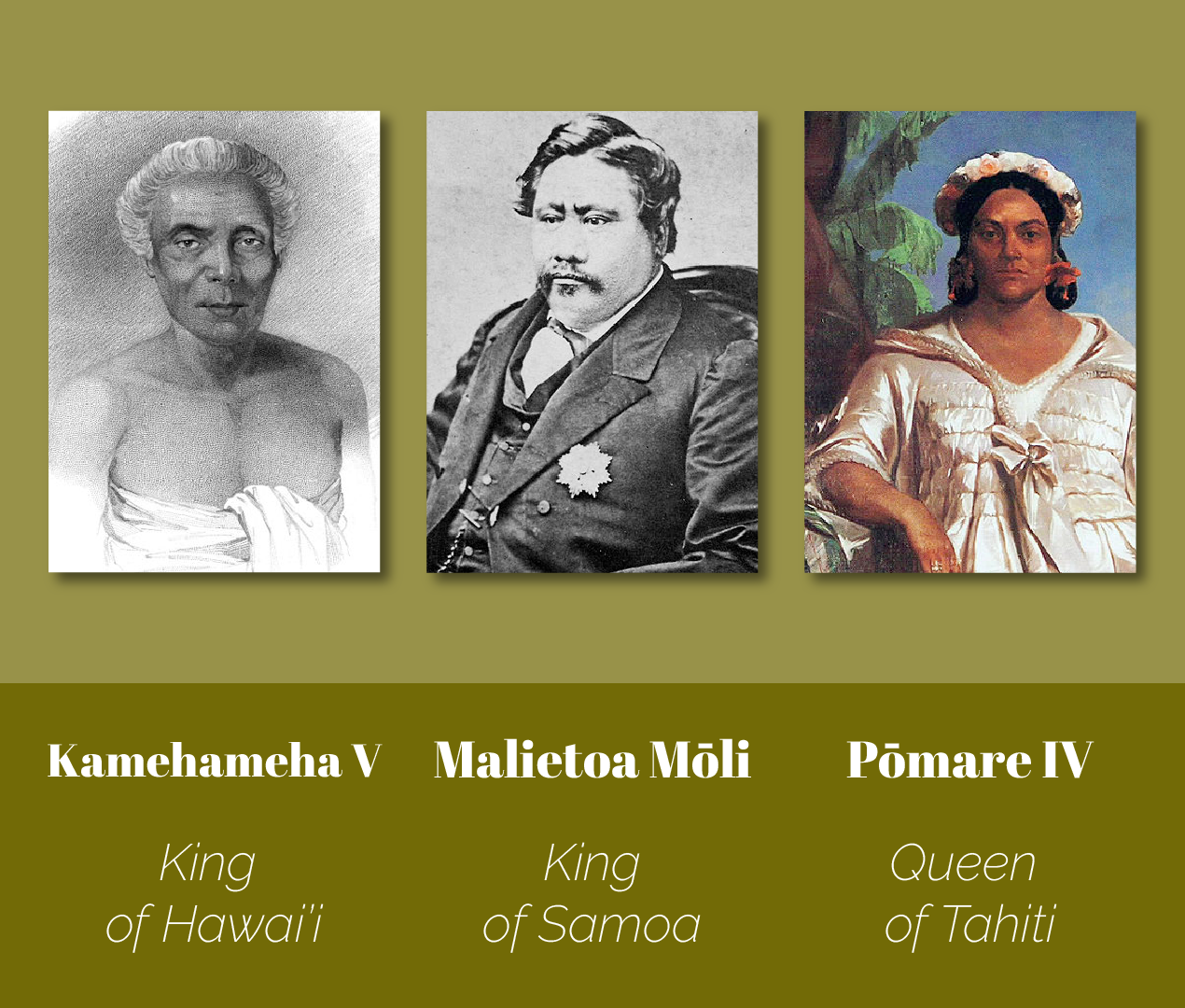

Bahá'u'lláh revealed the Súriy-i-Mulúk (Surah of Kings), His “most momentous proclamatory work,” addressed to the Kings of the earth, immediately after the darkest and most tumultuous period of His life, the Most Great Separation and the casting out of Mírzá Yaḥyá in September 1867.

In the Súriy-i-Mulúk, revealed entirely in Arabic, Bahá'u'lláh proclaims His message and reveals His station to the following individuals and groups of people:

- To the kings of the earth

- To the kings of Christendom

- To the French Ambassador in Constantinople (Nicolas Prosper Bourée)

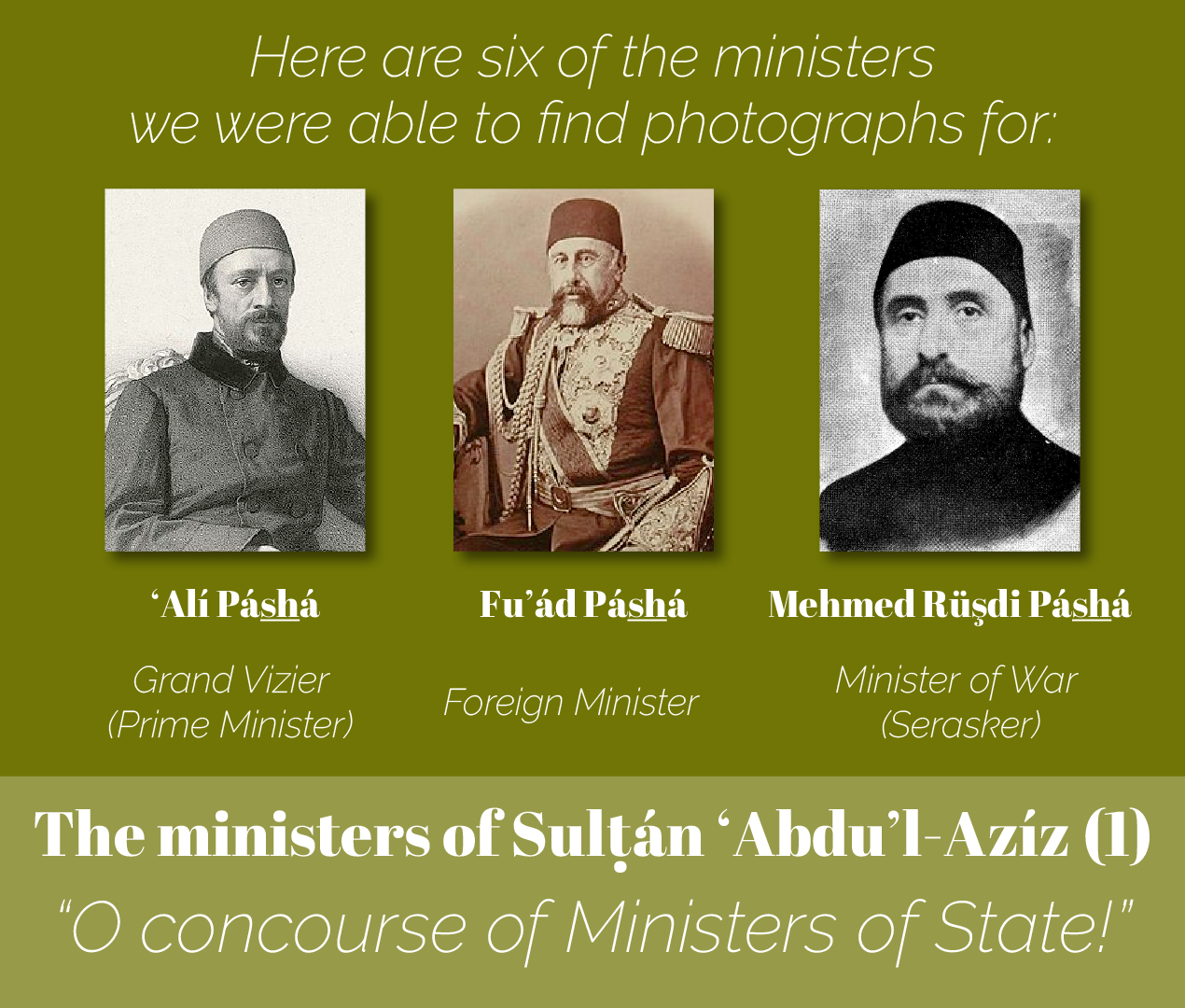

- To the ministers of Sulṭán ‘Abdu’l-Azíz

- To the citizens of Constantinople

- To Sulṭán ‘Abdu’l-Azíz

- To the Persian Ambassador in Constantinople (Ḥájí Mírzá Ḥusayn Khán)

- To the people of Persia

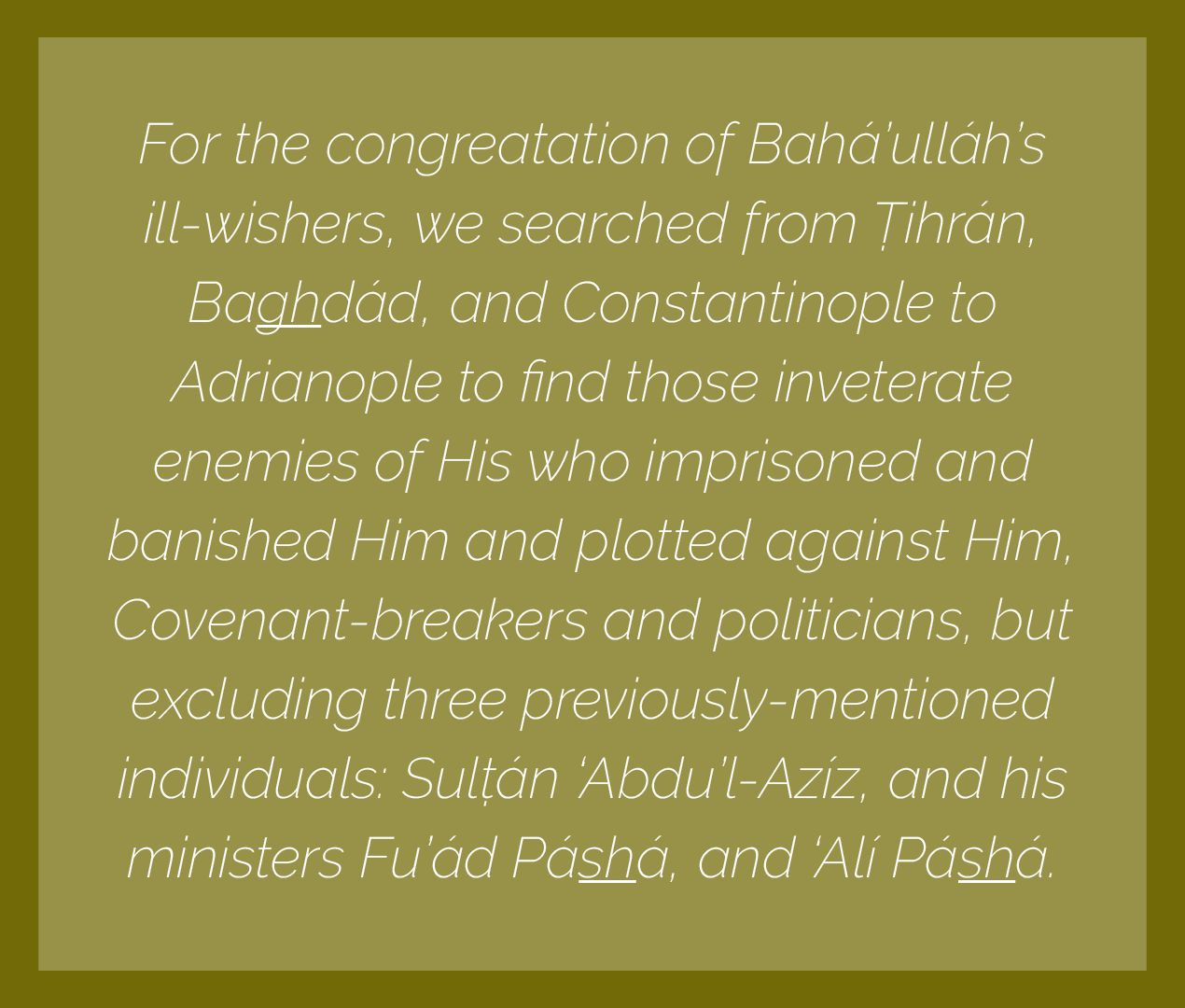

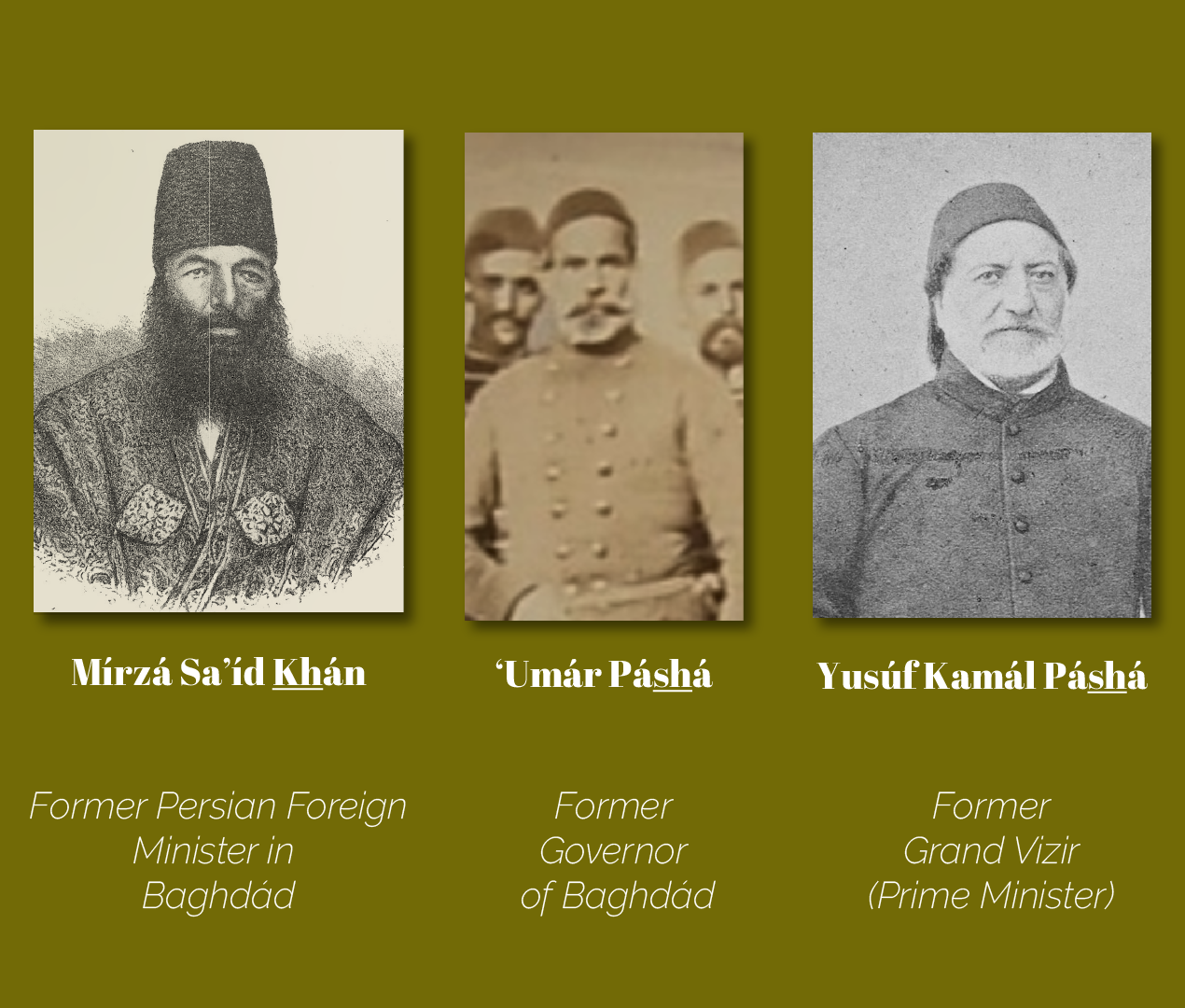

- To the congregation of Bahá'u'lláh's ill-wishers

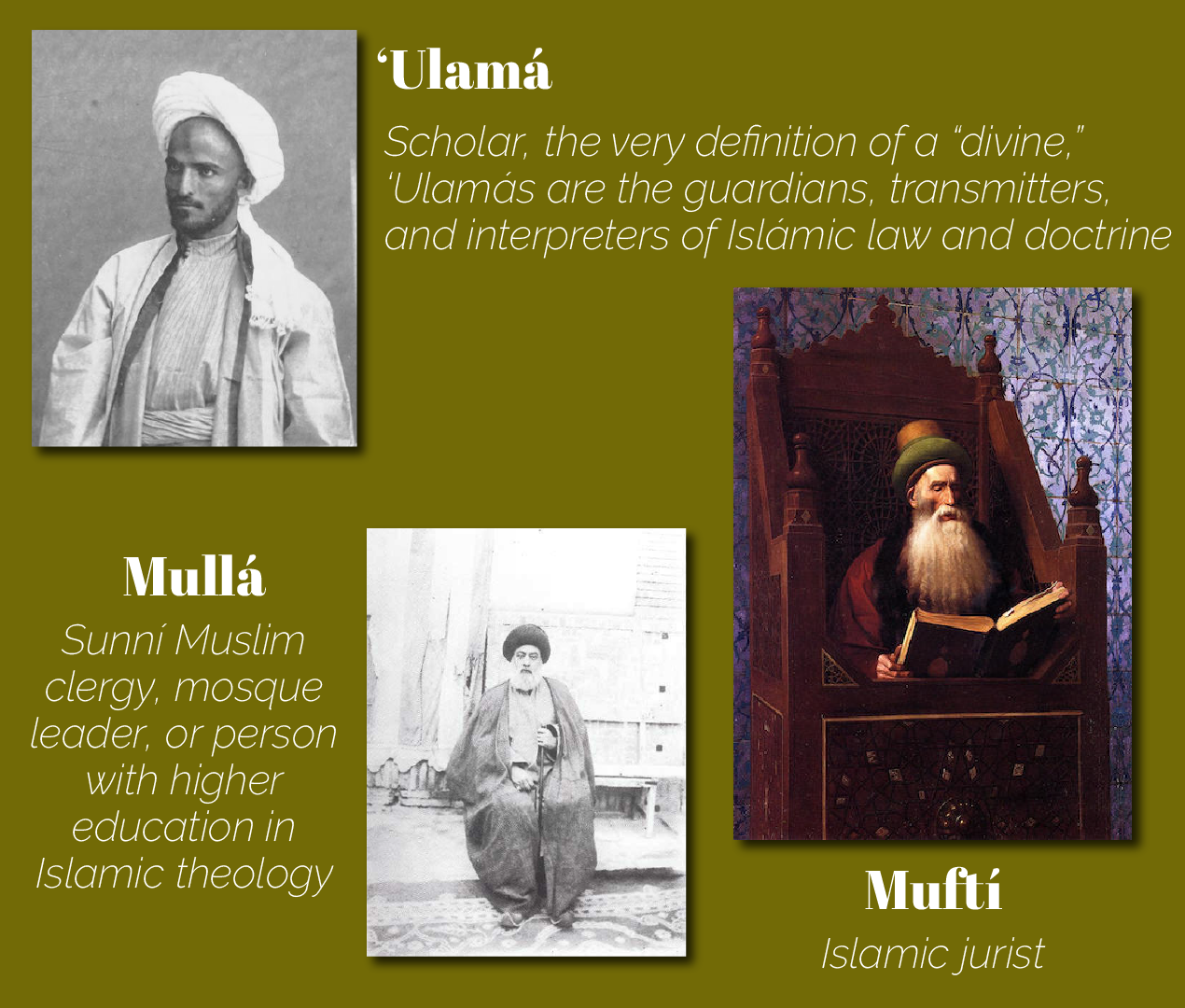

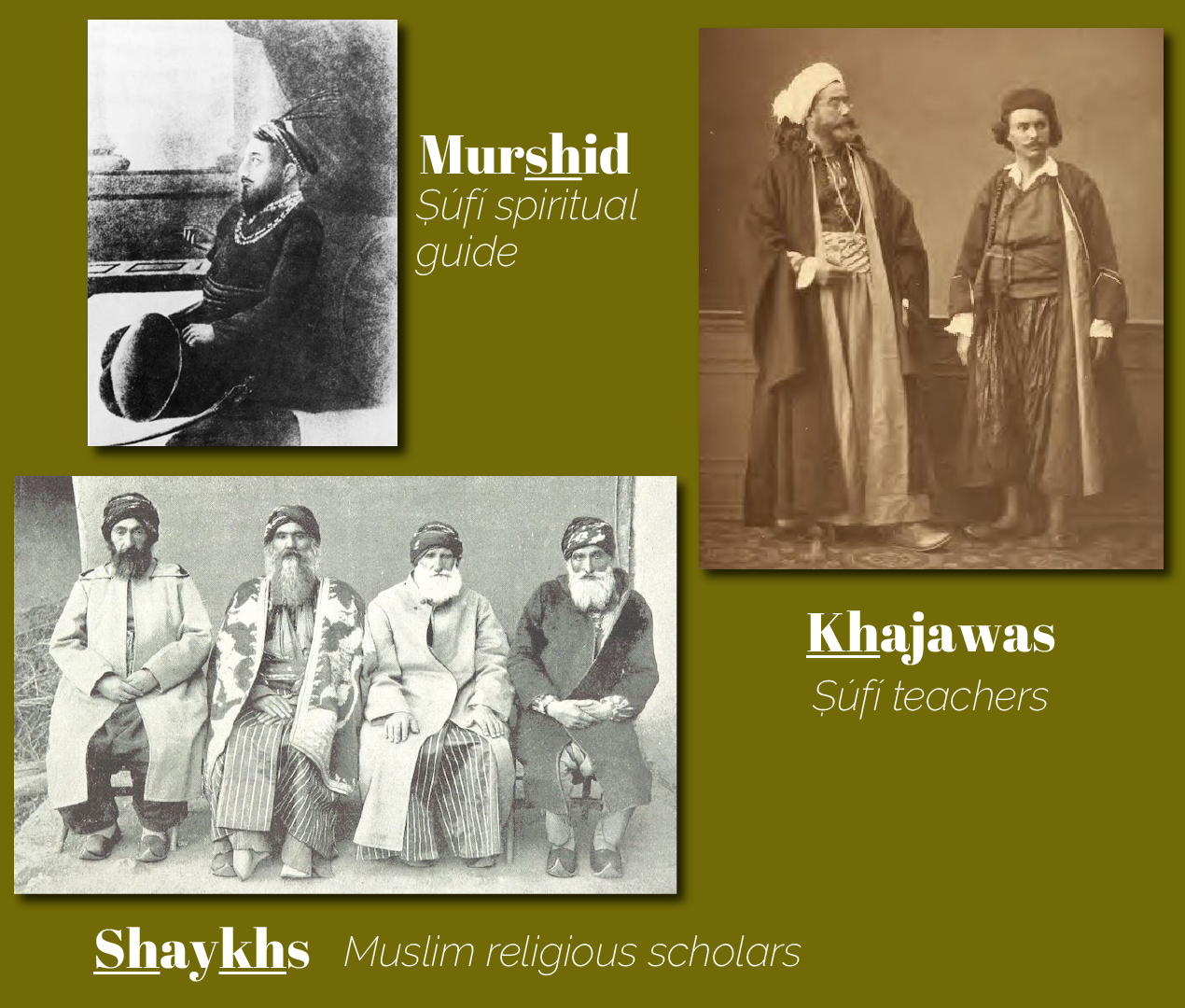

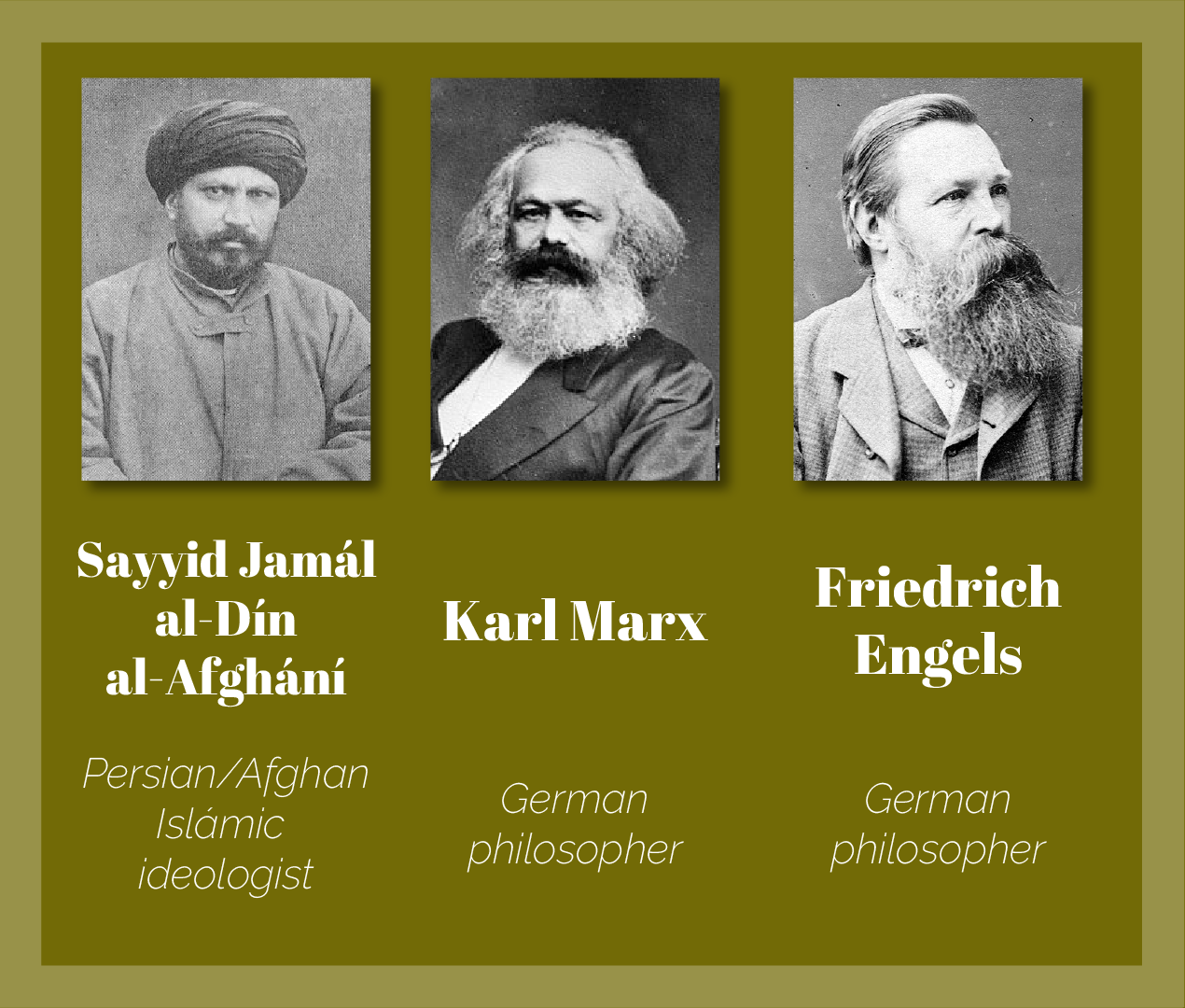

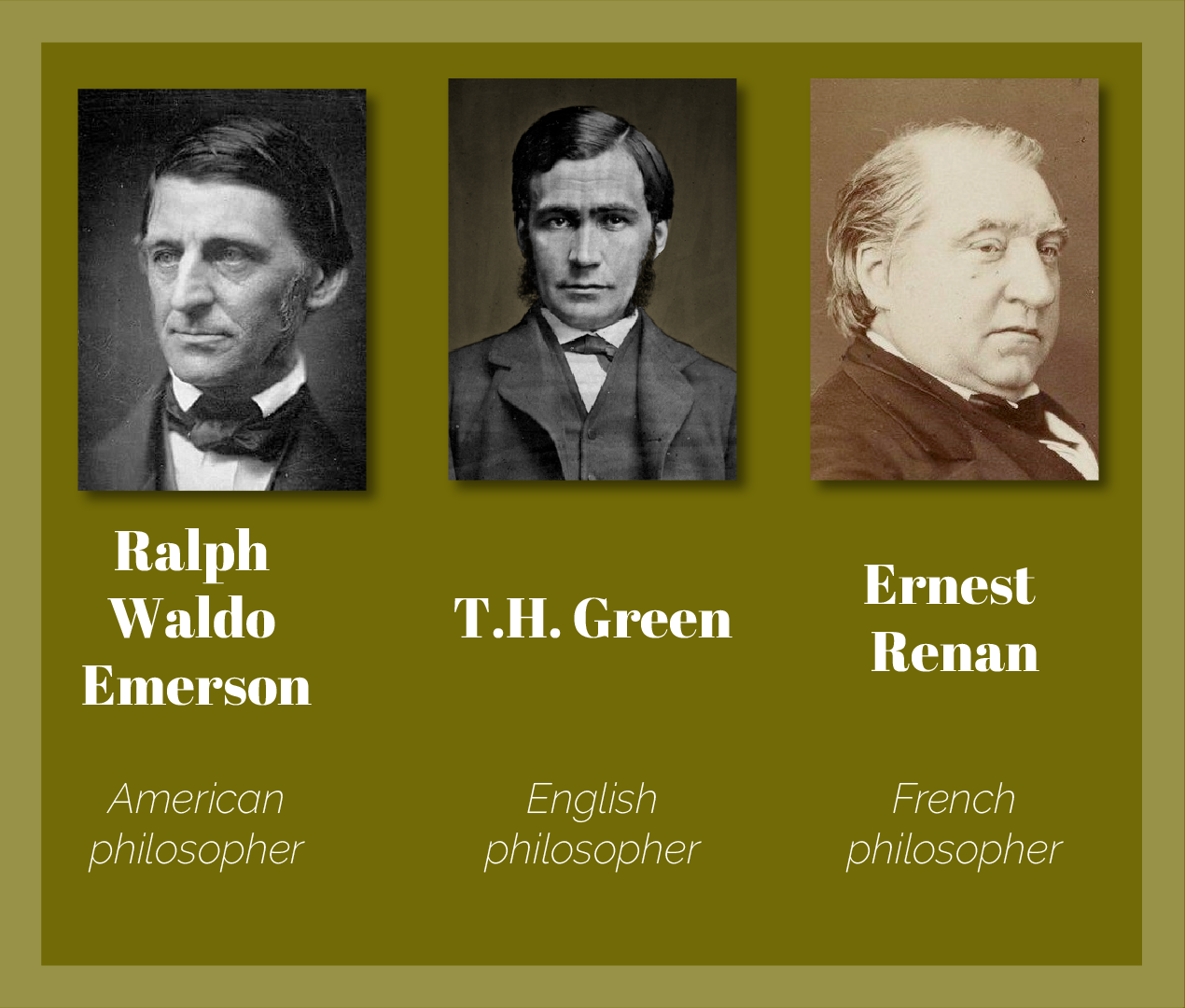

- To the wise men of Constantinople and philosophers of the world

- To the ecclesiastical leaders of Sunní Islám in Constantinople

The three main themes of the Súriy-i-Múlúk are:

- The responsibility of kings to accept the message of Bahá'u'lláh;

- General counsels and advice for kings and rulers;

- The consequences of not accepting the message of Bahá'u'lláh.

The summons of Bahá'u'lláh to the kings of the earth fell on deaf ears, and none of Bahá'u'lláh’s precious and foreshadowing advice and counsels were paid any mind.

SOURCES

Partial Inventory ID: BH00021

Steven Phelps "The Writings of Bahá'u'lláh" in Routledge World: The World of the Bahá'í Faith, First Edition, Edited By Robert H. Stockman, page 59.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Wikipedia: Summons of the Lord of Hosts: Súriy-i Mulúk "Tablet of Kings"

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868, pages 301-336.

HOW THE DATE WAS OBTAINED

The Universal House of Justice, in its Riḍván 1965 Message to the Bahá'ís of the world, made the following announcement:

" ... prepare national and local plans for the befitting celebration of the centenary of Bahá'u'lláh's proclamation of His Message in September/October 1867, to the kings and rulers of the world ..."

Source: The Universal House of Justice, Message of Riḍván 1965.

With thanks to Mr. Mohssen Madjidi for the reference.

Emperor Napoleon III, March 1860, portrait by Olympe Aguado de las Marismas. Source: The Met.

This is the First Tablet to Napoleon III, revealed in Adrianople in Arabic and Persian, and sent to the Emperor through one of his ministers. The longer Second Tablet to Napoleon III was revealed in ‘Akká and forms part of the Súriy-i-Haykal. This first Tablet has never been translated in its entirety, except a few sentences and one excerpt appearing in God Passes By and The Promised Day is Come.

Bahá'u'lláh revealed this First Tablet to Napoleon III to test the sincerity of two statements the Emperor made in response to why he had waged the Crimean War. In His statements, Napoleon III had spoken about having been awakened at dawn by the cry of the oppressed, and about our collective responsibility being to avenge the oppress and assist the helpless.

Bahá'u'lláh faces the French Emperor with the oppression, afflictions and injustices suffered by His followers and Himself over two decades, and asks him to enquire into the situation. Napoleon III did not reply.

Partial Inventory ID: BH01120

Steven Phelps "The Writings of Bahá'u'lláh" in Routledge World: The World of the Bahá'í Faith, First Edition, Edited By Robert H. Stockman, pages 63-64.

For the date of the Tablet: Ismael Velasco, Baha'u'llah's First Tablet to Napoleon III: A Research Note, published in Lights of Irfan, 4, pages 143-164.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868, pages 368-369.

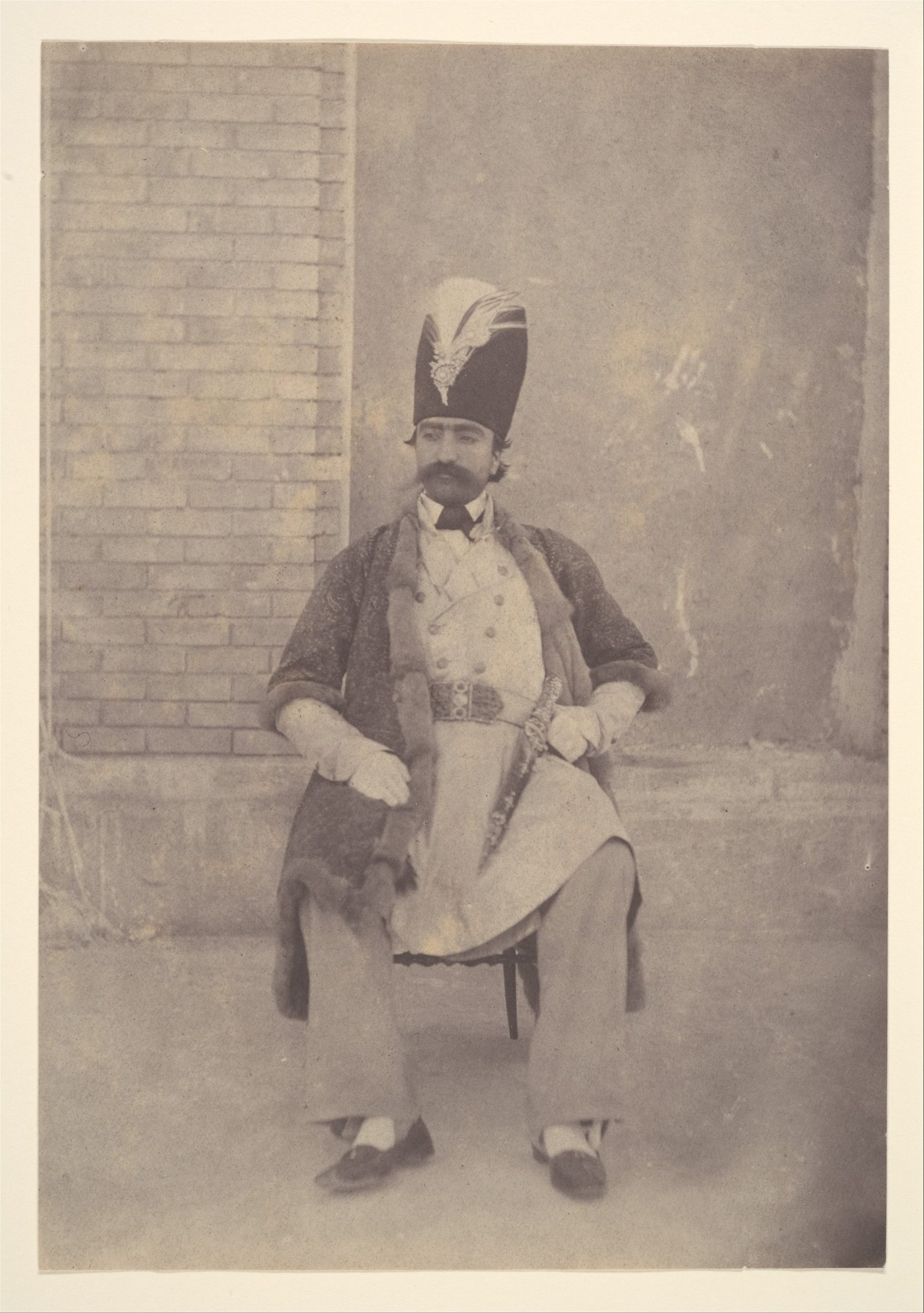

1840s–60s portrait of Naṣiri'd-Dín Sháh, possibly by Luigi Pesce. Source: The Met.

The Lawḥ-i-Sulṭán, revealed Persian and Arabic in late 1867 – mid 1868 was addressed to Naṣiri'd-Dín Sháh, and is Bahá'u'lláh’s lengthiest Tablet to any monarch. It was delivered to the Sháh by Badí'.

This Tablet is significant because it is addressed not only to the ruler of Bahá'u'lláh's native land but to the only monarch to have savagely persecuted both the Bábí and Bahá'í Faiths, almost from their inception.

In several passages of the Lawḥ-i-Sulṭán, Bahá'u'lláh majestically describes for Naṣiri'd-Dín Sháh the moment He received the Revelation of God, in one of the most celebrated passages on this theme which begins: “O king! I was but a man like others, asleep upon My couch, when lo, the breezes of the All-Glorious were wafted over Me, and taught Me the knowledge of all that hath been.”

One of the main themes of the Lawḥ-i-Sulṭán, is the relationship between Naṣiri'd-Dín Sháh and the Bahá'í Faith. Bahá'u'lláh recounts the sufferings He and His followers have endured, urges the Sháh to consider the possibility of the appearance of a new Manifestation of God in this day, and demonstrates the validity of His mission, asking the king to judge fairly.

In the Lawḥ-i-Sulṭán, Bahá'u'lláh suggests Naṣiri'd-Dín Sháh He “be brought face to face with the divines of the age, and produce proofs and testimonies in the presence of His Majesty the Sháh.”

An interesting feature of this Tablet is that some of the Arabic terms Bahá'u'lláh chooses to use are so complex and unusually difficult, that the Sháh had to seek the help of divines in reading the Tablet. When he tasked them with writing a response, they could not do it.

However the most spectacular feature of the Lawḥ-i-Sulṭán is the manner in which it was delivered to Naṣiri'd-Dín Sháh and the exalted character of the stainless hero who fearlessly handed it to the Persian despot. The immortal story of Badí', His spiritual transformation, His heroic martyrdom, God's retributive justice after his sacrifice, and the three years of Tablets Bahá'u'lláh revealed after His death are addressed in great detail in Part VII: The Most Great Prison, in a section titled Spring – Summer 1869: Badí delivers the Lawḥ-i-Sulṭán.

By clicking on the graphic below, you can listen to a passage from the Lawḥ-i-Sulṭán recited in Arabic with English subtitles. This passage is found towards the end of the Tablet and begins with the words "Whither are gone the learned men..." This particularly eloquent excerpt was the spark that eventually gave rise to the entire Utterance Project, so stirring is Bahá'u'lláh's Arabic.

An 1855–58 portrait of Naṣiri'd-Dín Sháh, possibly by Luigi Pesce. Source: The Met.

Partial Inventory ID: BH00038

Steven Phelps "The Writings of Bahá'u'lláh" in Routledge World: The World of the Bahá'í Faith, First Edition, Edited By Robert H. Stockman, page 64.

Bahá'u'lláh, Lawḥ-i-Sulṭán (Tablet to Naṣiri’d-Dín Sháh)

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868, pages 337-357.

*HOW THE DATE WAS OBTAINED

In its Introduction to the Summons of the Lord of Hosts, the Universal House of Justice states:

"Of the various writings that make up the Súriy-i-Haykal, one requires particular mention. The Lawḥ-i-Sulṭán, the Tablet to Náṣiri’d-Dín Sháh, Bahá’u’lláh’s lengthiest epistle to any single sovereign, was revealed in the weeks immediately preceding His final banishment to ‘Akká. "

With many thanks to Mohssen Madjidi for providing the source of this date.

18th century Ottoman miniature from the Surname-i Vehbi manuscript of a banquet depicting Sulṭán Ahmed III and guests eating perhaps pudding with spoons. Source: We Are Food.

In Baghdád, Bahá'u'lláh had never set foot in the house of an official, but one night during His last Ramaḍán in Adrianople, between 28 December 1867 and 25 January 1868, Bahá'u'lláh accepted a dinner invitation by Khurshíd Páshá (Mehmed Hurşid Paşa), an illustrious Ottoman statesman and vizir, who served as minister for Sulṭán ‘Abdu’l-Azíz. Bahá'u'lláh’s utterances and His demeanor captivated the distinguished guests.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 243.

City of Edirne website (in Turkish) T.C. Edirne Valiliǧi: Our Served Governors.

Biyografya (in Turkish): Mehmed Hurşid Paşa.

HOW THE DATE OF THE DINNER WAS DETERMINED:

This invitation took place after the Most Great Separation in September 1867, After the month of Ramadan for 128 A.H, the only month of Ramaḍán left was in 1284 A.H., between 28 December 1867 and 25 January 1868, see Habibur: Islamic Hijri Calendar For Ramadan - 1284 Hijri

Abstract map of the countries/regions the Bahá'í Faith has spread to in 1867-1868. "The Caucasus" is represented on this map by Armenia and Azerbaijan, but considered as one region together. © Violetta Zein.

In this last period in Adrianople, the Faith was marked by a series of internal developments.

The terms “Bábí” and “People of the Bayán” were replaced by “Bahá'í” and “People of Bahá” and “Alláh-u-Abhá” (God is the Most Glorious) replaced “Alláh-u-Akbár” (God is the Greatest).

Illustrious disciples of the Báb, including Letters of the Living, some survivors of the struggle of Ṭabarsí, and the erudite Mírzá Aḥmad-i-Azghandí, joyfully proclaimed themselves followers of Bahá'u'lláh and arose to defend their new Faith as Bahá'u'lláh had done in the Kitáb-i-Bádi.

The Bahá'í Faith reached the Caucasus, Egypt, and Syria, in addition to Persia, ‘Iráq and Turkey, bringing the total countries/regions where the banner of the Faith was unfurled to six.

Bahá'u'lláh instructed Nabíl to proceed to Shíráz and Baghdád and perform the very first Bahá'í pilgrimage in history. With this act, Bahá'u'lláh was, in essence, foreshadowing the Revelation of the Kitáb-i-Aqdas, seven years hence in 'Akká, where He would lay out the sacred duty of pilgrimage.

The two houses Nabíl visited on the first pilgrimage in Bahá'í history: The "Most Great House," the house of Bahá'u'lláh in Baghdád, and the house of the Báb in Shíráz. Sources: Taaza Khabar News and Baha'i Blog.

Nabíl was titled Nabíl-i-A‘ẓam in a Tablet where Bahá'u'lláh enjoins on him to arise and teach the Faith in the east and the west, and champion the Cause, which he Nabíl exerted himself at to the end of his life, strengthening the Faith of individuals, reinforcing cohesion in communities, and imparting his vast knowledge

During this period, Bahá'u'lláh also revealed two prayers for Fasting, in anticipation, by at least five years of the revelation of the Law of Fasting in the Kitáb-i-Aqdas in ‘Akká in 1873.

'Abdu'l-Bahá’s station was unveiled to the believers through the revelation of the Súriy-i-Ghuṣn (The Tablet of the Branch), see dedicated section below.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 249 and 251.

Encyclopaedia Iranica: ḤAYDAR ʿALI EṢFAHĀNI, Ḥājji Mirzā

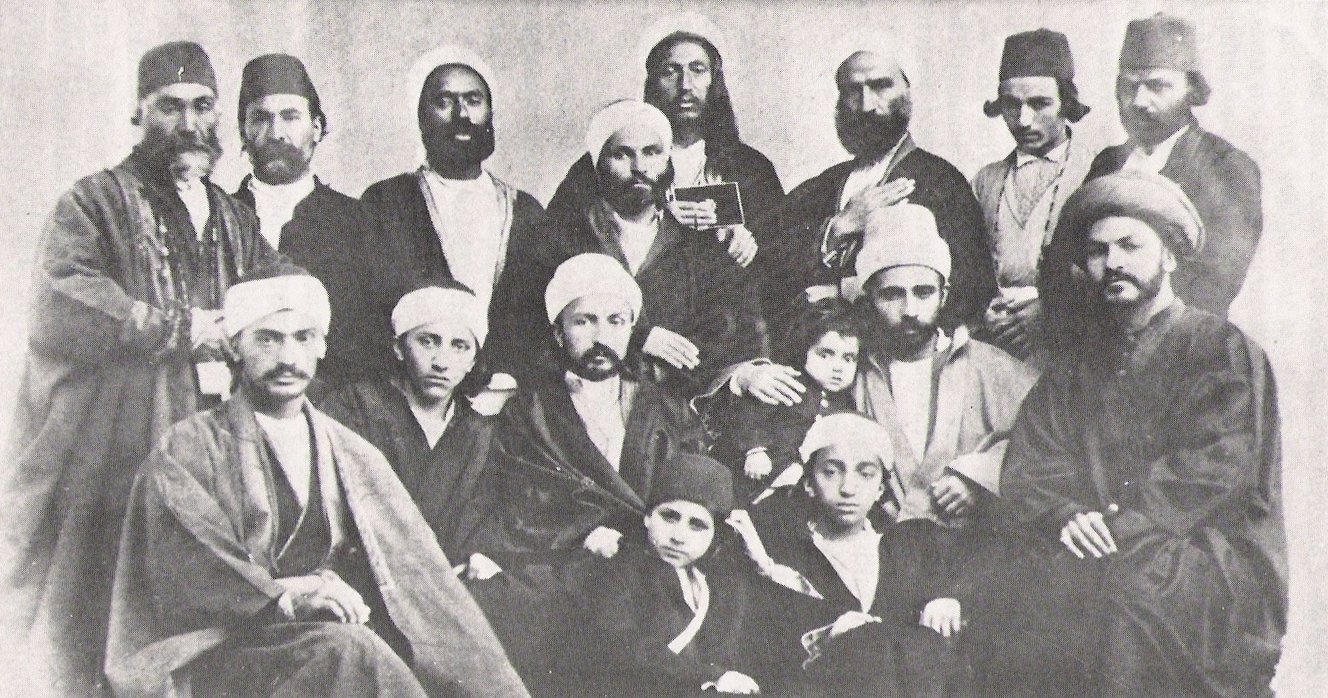

Abdu'l-Bahá in Adrianople with His brothers and companions of Bahá'u'lláh. Original photograph from H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 242. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

It is so incredibly rare to have photographs of the early believers during the time when Bahá'u'lláh was alive, and this is probably the most famous of the few we have in our possession, depicting a group of Bahá'ís in Adrianople around 1867-1868. This is the group photograph in Adrianople that includes 'Abdu'l-Bahá (then 23/24) and His younger brother Mírzá Mihdí (19/20 years old). Here we see a captured moment in time that shows us perhaps the most mature and informed local Bahá'í community in 1867/1868.

Here are all the people depicted in this photograph:

Standing, left to right: Áqá Muhammad-Qulí-i-Iṣfahání, Mírzá Naṣru'lláh-i-Tafrishí, Nabíl-i-A'ẓam, Mírzá Áqá Ján (Khádimu'lláh “Servant of God”), Mishkín-Qalam, Mírzá ‘Alíy-i-Sayyáḥ-i-Marághih’í, Áqá Ḥusayn-i-Ashchí, and Áqá 'Abdu'l-Ghaffár-i-Iṣfahání.

Seated, left to right: Mirza Muḥammad-Javád-i-Qazvíní, Mírzá Mihdí (the Purest Branch), 'Abdu'l-Bahá, Mírzá Muḥammad-Qulí (with, presumably, one of his children), and Siyyid Mihdíy-i-Dahijí.

Seated on the ground, left to right: Majdi'd-Dín (son of Mírzá Músá, Áqáy-i-Kalím) and Mírzá Muḥammad-'Alí (half-brother of 'Abdu'l-Bahá).

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 242.

A view of Adrianople in the early 1900s. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Bahá'u'lláh’s four-and-a-half-year banishment in Adrianople ensured Persian and Iráqí Bahá'ís knew where to find Him. In 1867 – 1868 alone, we have records for 14 pilgrims coming to see Bahá'u'lláh, with the real number perhaps being several times higher. The influx of pilgrims coming to the ends of the Ottoman empire to enter His presence was such, that Ottoman authorities became concerned, a situation Siyyid Muḥammad and Siyyid Muḥammad-i-Iṣfahání and Áqá Ján Big-i-Kaj-Kuláh wasted no time in weaponizing.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 243, 247 and 248.

Three views of the exterior of the Shrine of Imám-Zádih Ma‘ṣúm in Ṭihrán, and one photograph (bottom) showing the alcove where the remains of the Báb were hidden for almost two decades. Source: Crimson Academy, original source for photographs, The Bahá'í World.

Around 1867-1868, Bahá'u'lláh sent a Tablet to two Bahá'ís in Ṭihrán, Mullá ‘Alí-Akbar-i-Shahmírzádí and Jamál-i-Burújirdí, and ordered them to transfer the remains of the Báb from the Shrine of Imám-Zádih Ma‘ṣúm, where Bahá'u'lláh had instructed them to be concealed, almost two decades earlier, in the summer of 1850.

Bahá'u'lláh's instructions were to bring them, with the utmost secrecy to a new, safe location. The two men hid the sacred casket in the basement of a believers’ home, then quickly rented his house to keep watch over it. Shortly after they had been moved to a secure location, the Shrine where they had been hidden underwent renovations that would undoubtedly have uncovered the remains.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By: The Rebellion of Mírzá Yaḥyá and the Proclamation of Bahá’u’lláh’s Mission in Adrianople

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By: Entombment of the Báb’s Remains on Mt. Carmel.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 1: Baghdád 1853 - 1863, pages 402-403.

Michael Day, Journey to a Mountain, (Kindle Edition), Chapter 3: Looking for a safe place.

A portrait of 'Abdu'l-Bahá in Adrianople in 186. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, Copyright © Bahá’í International Community.