Written and illustrated by Violetta Zein

This part covers the life of Shoghi Effendi from the age of 45 in 1942 to the age of 48 in 1945.

“100 years.” Most God Passes By graphics will use this custom-made background composed of every one of the 150 photographs in The Dawn-Breakers, and every black and white pre-1940 photograph on the website Bahá'í Media Bank, a total of 225 images in a 15 x 15 grid.

When Shoghi Effendi conceived the idea of what was to become God Passes By, the most befitting tribute for the Centennial—the triple centenary of the Bábí Dispensation, the first 100 years of the Bahá'í Cycle and the 100th anniversary of the birth of 'Abdu'l-Bahá—it was never his intention to write a detailed history of these awe-inspiring, thrilling first hundred years.

What the Guardian had in mind was a review.

In fact, in some of Rúḥíyyih Khánum’s diary entries for the years when Shoghi Effendi was writing God Passes By, she called the manuscript “this Centennial Review.” In his letters to his collaborator, George Townshend, Shoghi Effendi referred to the unnamed manuscript as the “survey.”

What Shoghi Effendi understood by “review,” was a sweeping panorama of the noteworthy, important features of the birth of the Bahá'í Faith and its rise, from Persia to the confines of the Ottoman Empire and Central Asia during the ministry of Bahá'u'lláh, to North America, Europe, Australia and South-east Asia during the ministry of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, and around the entire planet during the first two decades of the Formative Age—during the ministry of Shoghi Effendi, in fact, though he would never mention his name in the book.

Shoghi Effendi also intended to clearly delineate a very central theme to the entirety of God Passes By, namely the series of internal and external crises that, through the mysterious, spiritual release of Divine power within it, propelled the Faith forward from victory to victory.

The Guardian intended to cast his unerring eye on the majestic panorama of the Bahá'í Faiths’ first—dramatic, momentous, extraordinary, majestic—hundred years, and, in the way only the Expounder of the faith of Bahá'u'lláh could, interpret what had just happened.

Shoghi Effendi was planning to lift the curtain and shine the spotlight on the first four periods in the history of the Bahá'í Faith: the successive ministries of the Báb, Bahá'u'lláh, 'Abdu'l-Bahá, and the first epoch of the Formative Age. As Shoghi Effendi explains in the Foreword to God Passes By:

These four periods are closely interrelated, and constitute successive acts of one, indivisible, stupendous and sublime drama, whose mystery no intellect can fathom, whose climax no eye can even dimly perceive, whose conclusion no mind can adequately foreshadow.

After twenty years of interpreting Bahá'u'lláh’s Holy Writings in translation, Shoghi Effendi was going to interpret the history of the Faith of Bahá'u'lláh. As the year 1944 was approaching, Shoghi Effendi, exhausted and overburdened in his 23rd year as Guardian of the Cause, found himself with an immensely daunting task ahead of him: how to befittingly mark the first century of the Bahá'í Era.

Shoghi Effendi’s self-imposed task was herculean, the conditions he would work under stressful beyond belief, the deadline he imposed on himself almost impossible, the occasion of the Centennial, never to be repeated.

The pressure on Shoghi Effendi was immense.

God Passes By would be the last major work the Guardian ever wrote. For the next thirteen years Shoghi Effendi neither translated nor wrote any more books.

God Passes By would be his grand opus, his masterpiece.

And yet despite all these pressures, for the first year of his work on the monumental project of God Passes By, Shoghi Effendi kept working.

He began to write his first and only book: God Passes By.

For the first year, Rúḥíyyih Khánum explained that Shoghi Effendi sat down and read every book.

Every book of the Bahá'í Holy Writings in Persian and English, published or unpublished, in manuscript form.

Every book written about the Faith by Bahá'ís.

Every single significant reference to the Bahá'í Faith he could find in regular books.

The Guardian read at least 200 books.

As Shoghi Effendi read, he made notes in his small notebooks, and as he made notes, he organized and structured his facts. Historical research is painstaking, it is grinding, repetitive, methodical work that requires constant attention and self-discipline, but also work that requires wisdom and discernment.

Often, the Guardian had to interpret history. He had to decide between two dates for the same event in two different sources which was the likeliest.

And then, once he had read all the sources, and taken all his notes, the real work of brining his brilliant idea to life began: the writing process.

The circumstances under which Shoghi Effendi wrote God Passes By were a living nightmare.

It was the middle of World War II and danger—as we will see in the next story—sometimes directly threatened Shoghi Effendi, but beyond his personal safety, the years of the war were an almost unbearable stress for the Guardian, who worried for six years about the Bahá'í communities which were cut off from him, and he felt a great deal of anxiety about their safety, worries that would only be allayed once the war was over and communication was reestablished with the entire worldwide Bahá'í community.

Shoghi Effendi’s work environment was a pressure-cooker, as Rúḥíyyih Khánum describes the stress he was under, working to meet a hard deadline of 23 May 1944, the Centennial:

There was no possibility of working at a slower pace. he was racing against time to present the Bahá'ís of the West with this inimitable gift on the occasion of the one hundredth anniversary of the inception of their Faith.

Shoghi Effendi was exhausted after 20 years of Guardianship.

His family had all turned against him, Covenant-breakers one and all, and, in Rúḥíyyih Khánum’s words, they crushed “every ounce of spirit out of the Guardian.” Covenant-breaking was the only thing that ever made the Guardian truly physically ill.

At the same time as he was undertaking this herculean literary project, Shoghi Effendi was also planning the worldwide celebrations for the Centennial—in those countries that were able to hold celebrations—and making crucial regarding the design of the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb.

So much pressure resting on the Guardian’s shoulders were at times unbearable, even to him. The Guardian could not delegate. He had to withstand the pressure, and do the work. No one else could, no one could help him or relieve his burden.

A Hawker Hurricane. Two of these planes crashed in the sky above Haifa and could have killed the Guardian. The debris of the plane landed 100 meters from the House of the Master. Both pilots were killed. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

On 20 March 1942, Shoghi Effendi was working on God Passes By when two Hawker Hurricane single-seat fighter planes of the 127 Squadron collided in mid-air over Haifa during training exercises. The planes lost control, crashed and burned.

One of the planes, as it was crashing, narrowly missed the Master’s house, where Rúḥíyyih Khánum and Shoghi Effendi were, and crashed at the lower end of their street, bursting into flames less than 100 meters away.

The Guardian could easily have been killed.

Both pilots, Second Lieutenant Charles Henry Gielink of the South African Air Force, 24, and Flying Officer John Lewis Ward of the British Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve, 26, died in the crash.

One day, Shoghi Effendi was translating out loud and Rúḥíyyih Khánum was in the room with him. It was a lifelong habit of the Guardian to always have another person in the room when he wrote or translated, it was something he loved to have. Rúḥíyyih Khánum had the bounty of being in the Guardian’s room while he wrote or translated for 20 years.

Suddenly, the Guardian read to Rúḥíyyih Khánum the words he had just stumbled upon:

If the Bahá’ís had been occupied with that which we had commanded, now the entire world would be clothed in the robe of faith

Rúḥíyyih Khánum was horrified and asked Guardian:

Shoghi Effendi, did Bahá’u’lláh mean it?

Shoghi Effendi responded:

Well, if he said it, if he wrote it, he must have meant it.

When did he write it?

In Baghdad.

This was something that was very much on the Guardian’s mind, and he despaired about it. He would often say to Rúḥíyyih Khánum, lamenting over the condition of the world:

Do you realize is over 100 years since Bahá’u’lláh appeared in this world and what has been the response to His message?

Rúḥíyyih Khánum, trying to cheer Shoghi Effendi up would quote his statistics back to him:

Oh Guardian just think of it there are 12 Spiritual Assemblies, National Assemblies, think of it, 12! ...And there are Bahá’ís in so many countries!

But the Guardian would look at Rúḥíyyih Khánum and say:

There are millions of people in the world. What has been the response to Bahá’u’lláh?

After this conversation, Rúḥíyyih Khánum stated that she never again felt comfortable. Bahá'u'lláh and the Guardian were, in essence, stating categorically that humanity had failed Bahá'u'lláh. It was a universal failure. And he stated it in Baghdad, which means, sometime between 1983 and 1863. The historical aspect of this devastating quote was what made Rúḥíyyih Khánum uncomfortable. If Bahá'u'lláh had said this during His own ministry, what would he say of humanity’s failure today?

Bahá'ís can never be complacent about their service. It is never enough.

The Guardian wove his notes and research together into a brilliantly-hued tapestry of the first 100 years of the Bahá'í Faith, a work which would become the foundation of all future Bahá'í histories and would forever be known as the crowning literary achievement of his ministry.

After the one year research process, Shoghi Effendi’s one year writing process was just as painstaking, methodical, and excruciating. He spent day after day, month after month, writing the manuscript out in longhand on his notebooks while he spoke it out loud, Rúḥíyyih Khánum in the room at all times, present for the birth of this work of genius.

Then, the Guardian wrote out a clean copy.

Almost a year later, in January 1943, Shoghi Effendi was still slaving over God Passes By. He was frustrated with his work when he entered Rúḥíyyih Khánum’s room, who tried to be helpful and suggested he read other historical books to find inspiration. Shoghi Effendi responded:

I have no time, no time. For twenty years I have had no time!

On 26 June 1943, George Townshend paid Shoghi Effendi a spiritually perceptive compliment:

I enclose the 7th instalment of the Survey. The work impresses me immensely and I foresee it will arouse great public interest and will be of the highest value in strengthening the faithful and stimulating their teaching work.

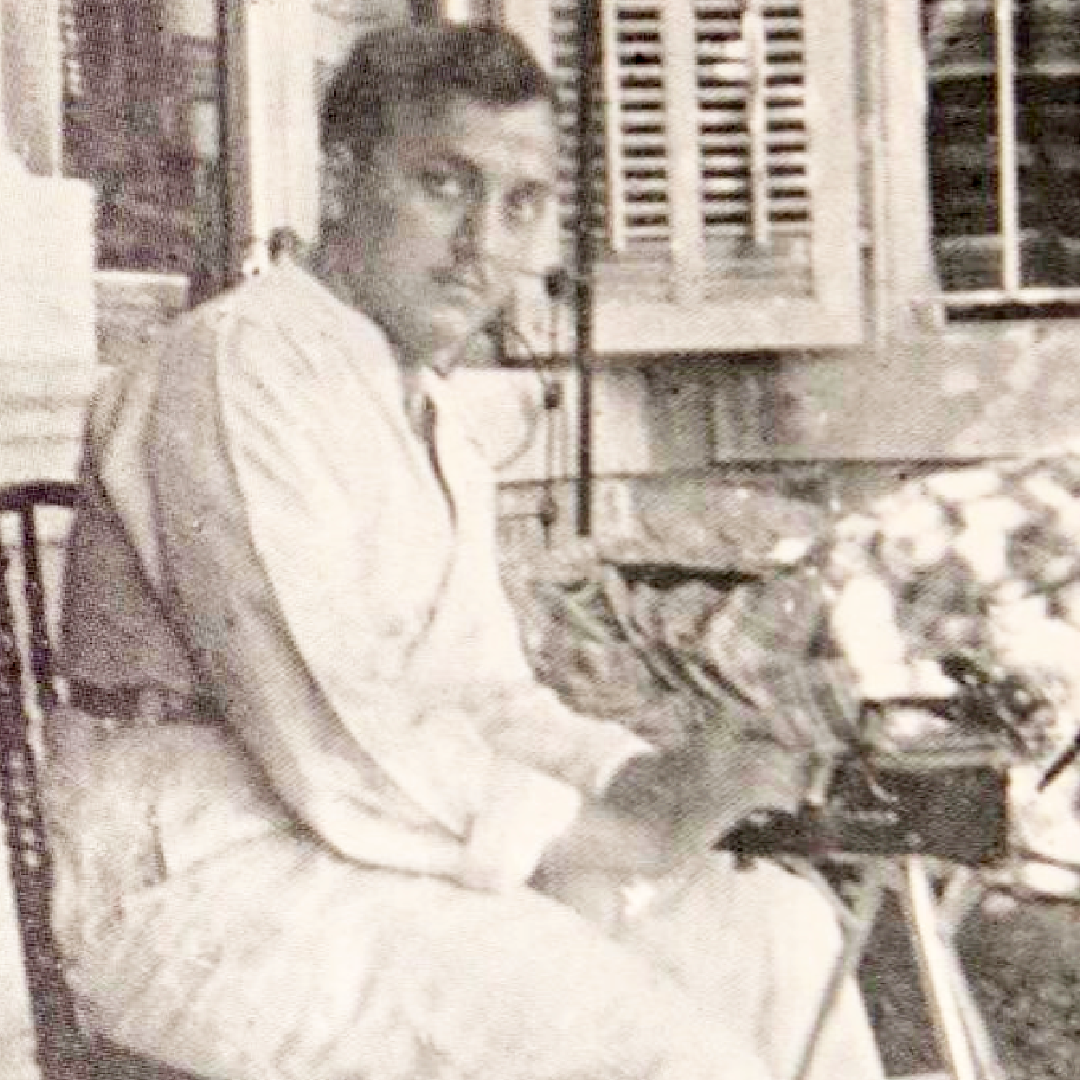

George Townshend, precious collaborator. Source: George Townshend by David Hofman, between pages 326 and 327.

The first time George Townshend heard of Shoghi Effendi’s new project was in a letter the Guardian wrote him dated 27 February 1942:

The Guardian has instructed me to write you on his behalf and to forward to you the enclosed pages for your perusal. He has been working for quite some time on a book to be published in conjunction with the Centenary Celebrations of our Religion in May 1944, and which would give, in relatively brief form, an outline of the most important phases and events in the evolution of our beloved Faith during its first hundred years.

The Guardian and George Townshend had a well-oiled literary partnership. The Guardian sent George Townshend typewritten pages, described their content and requested George Townshend focus his attention on certain issues or aspects.

George Townshend would live, breathe—and probably also dream—God Passes By for an entire and very intense year, from February 1943 to February 1944. He worked through very intense pain from arthritis in both his arms, and often could only work with his left hand. He made light of it in a lot of his letters from that time, telling his correspondents: “Not so bad with the left hand, is it?”

The Guardian wrote George Townshend 20 letters between 27 February and 11 August 1943 in which he included the typed pages of God Passes By as they became available, not in strict chronological order, and without correcting the typos. He was working alone, with no help, no typist, and no time. George Townshend offered Shoghi Effendi his editorial suggestions with his legendary tact and kindness.

The war-time delay between sending letters and batches of the manuscript back and forth were horrific, and Shoghi Effendi and George Townshend were forced to constantly send each other cables to determine which instalments had been sent and not yet received, in order to decide if they needed to send the package again. It made work very difficult.

On 26 June 1943, George Townshend paid Shoghi Effendi a spiritually perceptive compliment:

I enclose the 7th instalment of the Survey. The work impresses me immensely and I foresee it will arouse great public interest and will be of the highest value in strengthening the faithful and stimulating their teaching work.

Shoghi Effendi asked George Townshend to write an Introduction to God Passes By, and George’s essay was a marvel. It is not included in current editions of God Passes By, but can be found online—here is a link. The entire introduction is beautiful, but George’s lyrical English shines in the opening sentence:

Here is a history of our times written on an unfamiliar theme a history filled with love and happiness and vision and strength, telling of triumphs gained and wider triumphs yet to come: and whatever it holds of darkest tragedy it leaves mankind at its close not facing a grim inhospitable future but marching out from the shadows on the high road of an inevitable destiny towards the opened gates of the Promised City of Eternal Peace.

NOTE: Current editions of God Passes By do not contain the introduction of George Townshend, beginning instead with the Guardian’s own Foreword. You can read George Townshend’s original introduction to the first edition of God Passes By here on Bahá'í Library Online.

A closeup of a Corona, the same kind of typewriter the Guardian typed all his letters and translations on, as well as the entire manuscript of God Passes By. Photo by Johnny Briggs on Unsplash.

Bahá'ís coming on pilgrimage often brought gifts. An Indian once brought six banana shuckers which 'Abdu'l-Bahá gave specific instructions to plant in ‘Adasiyyíh. The Bahá'ís were the first to successfully cultivate bananas in the Holy Land, and they are now a major crop in the region. Persian believers often brought priceless carpets, other Bahá'ís brought clothing, jewels or home furnishings, but 'Abdu'l-Bahá did not allow His family to keep any of these gifts.

There was one gift, however, 'Abdu'l-Bahá did accept.

On 16 November 1919, the Randall family—Harry, Ruth, and their 12-year-old daughter Bahíyyih—arrived on pilgrimage with a trunk filled with gifts for 'Abdu'l-Bahá, which included a typewriter for Shoghi Effendi, a pocket watch for 'Abdu'l-Bahá, yards of soft wool fabric for the Greatest Holy Leaf to sew into a coat for the Master.

The small, portable Corona brand typewriter would go down in Bahá'í history.

It was on this typewriter that Shoghi Effendi began typing his manuscript letters as 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s secretary in 1919-1920 using carbon paper to make multiple copies, and typing using his signature two-finger method.

The two-finger method is also called the “hunt and peck” approach. Touch-typing is the method by which you use all the fingers of your hand on allocated keys and can type up to 100 words a minute. Outwardly, of course, touch-typing seems preferable, because with the two-finger method, your attention is divided between your typed sheet and looking at your fingers. Over the long run, though, for someone who did as much typing as Shoghi Effendi, the two-finger method is less stressful on the tendons of your hand, specifically because it is much slower.

Shoghi Effendi used his Corona typewriter to type the translations of 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s Tablets to the West, and it was on this same Corona typewriter that he wrote all his letters to the Bahá'ís of the West from 1922 to 1957.

Every lengthy letter—Bahá'í Administration, Advent of Divine Justice, The Promised Day is Come—all his translations—the Kitáb-i-Íqán, Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá'u'lláh, Epistle to the Sone of the Wolf—all his books—The Dawn-Breakers and God Passes By—were typed on the Corona the Randalls offered him in 1919.

Shoghi Effendi was running out of black ribbons for his typewriter at one point in his early ministry, and he immediately cabled his brother in Beirut to send him some:

Send with sister ten Corona ribbons colour black.

When Shoghi Effendi was writing God Passes By he spent ten hours on end hammering out his masterpiece, converting it from longhand to multiple typed copies.

That Corona typewriter was the instrument that connected Shoghi Effendi to the world. Once the handwritten draft of God Passes By was completed, Shoghi Effendi began hammering away the typescript of the manuscript and his “majestic procession of chapters” with his signature two-finger method on his small, portable typewriter, sometimes 10 hours on end. When Shoghi Effendi was at full speed, Rúḥíyyih Khánum stated that he would type with four fingers. In the end, Shoghi Effendi would type up six carbon copies of God Passes By.

Shoghi Effendi burned through the summer of 1943, working so hard on the book that Rúḥíyyih Khánum felt she had never seen him work this hard during a vacation.

By November 1943, Shoghi Effendi had been working on the manuscript for almost two years, and repeatedly said to Rúḥíyyih Khánum:

This book is killing me.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum invariably answered:

Me too.

Finally, by the end of December 1943, an end was in sight.

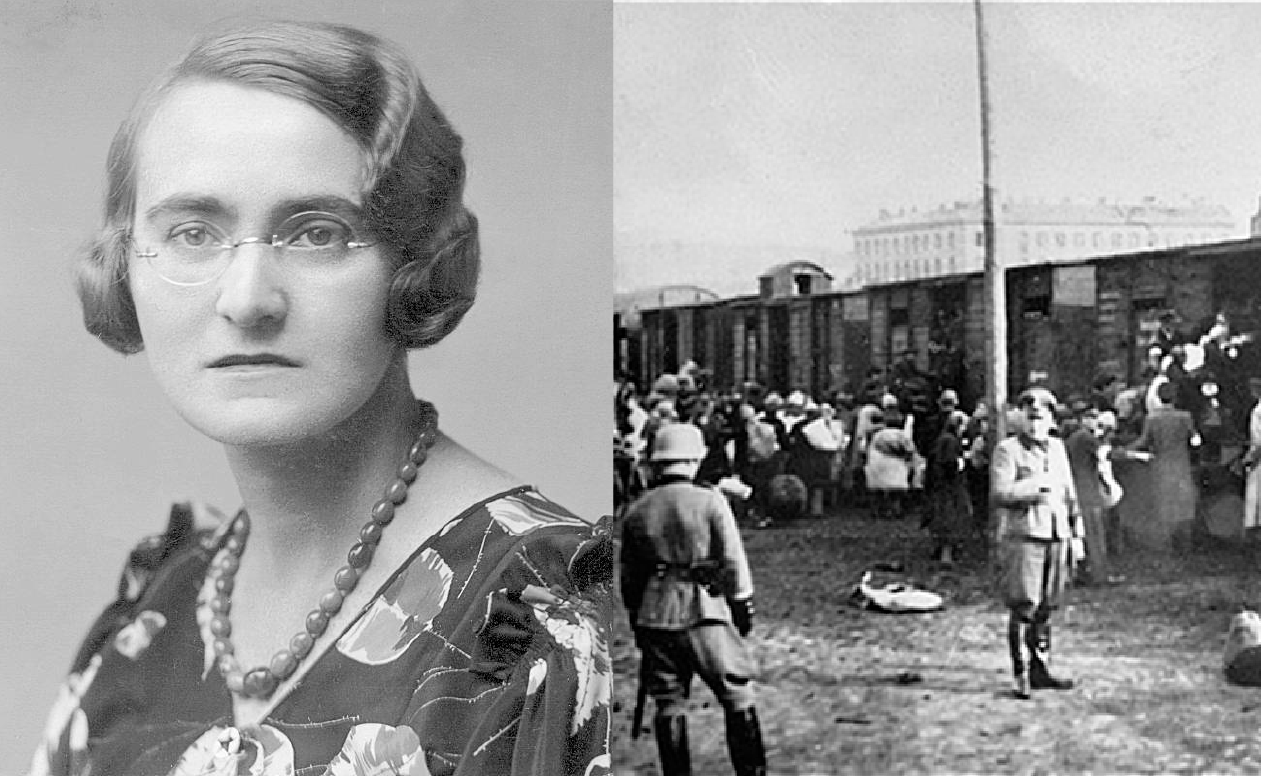

Lidia Zamenhof (1904–1942), youngest daughter of Ludwig Zamenhof, the creator of Esperanto. Source: Wikimedia Commons. Jews being loaded onto trains headed for the Treblinka extermination camp—the camp where Lidia Zamenhof was murdered—at the Umschlagplatz in Warsaw during the German occupation of Poland, sometime between 1942 and 1943. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Lidia Zamenhof, born on January 1904, was a writer, publisher and the youngest daughter of L. L. Zamenhof, the inventor of Esperanto.

She dedicated her life to promoting Esperanto, the hope for a universal language in the world, a manmade language that was the easiest language to learn. She was a close friend of Martha Root, and became a Bahá'í in 1925 in Geneva, when Martha Root organized the Esperanto Congress in the offices of the International Bahá'í Bureau.

Lidia taught Esperanto around the world, in Europe and America until December 1938, when she returned to Poland.

Under the German occupation regime of 1939, her home in Warsaw became part of the Warsaw Ghetto. She was first arrested under the charge of having gone to the United States to spread anti-Nazi propaganda, but was released, and began providing others in the ghetto with food and medicine. She never accepted offers to help her escape, and faced her fate with great courage and remained firm in her Faith to the end.

In her last letter, she wrote to a friend:

Do not think of putting yourself in danger; I know that I must die but I feel it is my duty to stay with my people. God grant that out of our sufferings a better world may emerge. I believe in God. I am a Bahá’í and will die a Bahá’í. Everything is in His hands.

Lidia was exterminated at the Treblinka camp in the summer of 1942.

Four years after her murder, on 23 January 1946, the Guardian sent this message to the Bahá'ís in America:

Heartily approve nationwide observance for dauntless Lidia Zamenhof. Her notable services tenacity modesty unwavering devotion fully merit high tribute American believers. Do not advise however designate her martyr.

The completed monument, designed by W. S. Maxwell. The wings were Rúḥíyyih Khánum’s suggestion, for which she made the models. Source: Bahaimedia.

May Maxwell died in Buenos Aires, Argentina on 1 March 1940. After her Martyrdom, Shoghi Effendi invited William Sutherland Maxwell to come and live with him and Rúḥíyyih Khánum in Haifa. They left the Holy Land in the spring of 1940 and after a seven-month journey spanning three continents, they were back in December of that year.

One year after his return, still grieving his catastrophic loss, William Sutherland Maxwell had completed the design for her monument. The Guardian asked Amelia Collins to supervise its construction.

William Sutherland Maxwell had not designed a family monument. The memorial he had created was for a heroine of the Faith whose entire body and soul, her life from the moment she became a Bahá'í, was dedicated to Bahá'u'lláh. William Sutherland Maxwell did not create this magnificent tribute alone. It was Rúḥíyyih Khánum who designed the wings, because she always believed her mother’s grave should be adorned with wings, and it was Shoghi Effendi’s contribution to add vases on the sides of the memorial because he felt it was too bare.

Four years after May Maxwell’s martyrdom, Shoghi Effendi remembered her in his 1944 masterpiece on the first century of the Bahá'í Faith, God Passes By:

Nor was this gigantic enterprise destined to be deprived, in its initial stage, of a blessing that was to cement the spiritual union of the Americas – a blessing flowing from the sacrifice of one who, at the very dawn of the Day of the Covenant, had been responsible for the establishment of the first Bahá’í centers in both Europe and the Dominion of Canada, and who, though seventy years of age and suffering from ill-health, undertook a six thousand mile voyage to the capital of Argentina, where, while still on the threshold of her pioneer service, she suddenly passed away, imparting through such a death to the work initiated in that Republic an impetus which has already enabled it, through the establishment of a distributing center of Bahá’í literature for Latin America and through other activities, to assume the foremost position among its sister Republics.

The House of ‘Abbúd, which the Guardian allowed the city of Haifa to use as a temporary location for a school in 'Akká during the War, free of charge. Source: Bahaimedia.

Throughout his Guardianship, Shoghi Effendi followed in the footsteps of Bahá'u'lláh and 'Abdu'l-Bahá, who were both known as “The Father of the Poor,” Bahá'u'lláh in Ṭihrán in the first nine years of his marriage to Ásíyih Khánum, and 'Abdu'l-Bahá in for his 40 years of service to the residents of 'Akká.

Whenever the district commissioner under the British mandate, or the municipalities of 'Akká and Haifa, in the time of the State of Israel, needed either cooperation or financial assistance, the Guardian offered it generously.

In the early days of his ministry, on 7 February 1923, the Guardian spontaneously offered a contribution of £20—£1,500 today—for the poor in Haifa.

Two years later on 16 February 1925, the Guardian offered the same generous amount to Colonel Symes for the establishment of the Haifa Charitable Fund.

In April 1926, Shoghi Effendi offered £30 as his contribution for the poor and homeless of the Northern District of Palestine.

On 7 May 1929, Shoghi Effendi contributed £50 for the prevention of begging in Haifa, with an explanation that begging was prohibited in the Bahá'í Faith.

In 1934, the District Commissioner for the northern District thanked Shoghi Effendi for his "most generous contribution towards the relief of distress in Tiberias" and for his kind message of sympathy.

In 1950, the Guardian offered £500—the value of £21,000 in today’s currency—for the relief of the poor and needy in Haifa.

Between 1940 and 1952, the Guardian donated over $10,000—$116,000 in today’s currency—to charitable causes, and to alleviate the hardships and living conditions of the poor, even contributing money to a charity connected to a mosque in Haifa, the government psychiatric hospital in 'Akká, located in the former barracks of the Most Great Prison, or a spontaneous contribution towards the construction of the Institute of Physics.

In 1952, Aba Khoushy, the Mayor of Haifa, wrote the Guardian that a country-wide symposium on Problems of Illuminations was going to take place at the Technical College in Haifa, and, because it coincided with Hanukkah, the Jewish Feast of Lights, he asked if Shoghi Effendi would consider illuminating the Shrine of the Báb on Mount Carmel between 12 and 19 December 1952.

The Guardian replied he would be “happy to co-operate in making the city of Haifa luminous and beautiful, in connection with the Symposium to be held at the Hebrew Technical College,” and gave instructions for the period of illumination of the Shrine to be extended during the days of the conference. He also invited the participants to visit the Shrine of the Báb and its gardens.

Perhaps the most significant charitable contribution was not a financial one, but a gesture of deep empathy on the Guardian’s behalf, connected to a cherished Holy Place of our Faith.

In 1943, the 'Akká District Commissioner wrote to Shoghi Effendi that he could not find a place to house a school, and was willing to pay rent and lease eight rooms in the House of ‘Abbúd, in the heart of 'Akká, a home where Bahá'u'lláh had lived and revealed the Kitáb-i-Aqdas, where 'Abdu'l-Bahá had lived for decades, and where Ásíyih Khánum had passed away.

The Guardian allowed the school to use the rooms.

He refused to take payment.

The extraordinarily delicate, lace-like exterior ornamentation of the House of Worship of North America, completed as one of the main goals of the First Seven Year Plan. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

During World War II, more than 50 countries deployed over 100 million soldiers and laid waste to entire swaths of the planet, massacring millions of innocent civilians.

During the same time, Shoghi Effendi, aided by a handful of devoted Bahá'ís won everlasting spiritual victories on an entire continent, bringing happiness to thousands, and achieving all three of the Guardian’s goals for the first Seven Year Plan, all in a time of world conflict.

American Bahá'ís doubled the number of Local Spiritual Assemblies in North America, established at least one Local Spiritual Assembly in each of the states of the United States, and each province of Canada, and completed the very expensive exterior ornamentation of the North American House of Worship.

And they reached these two goals 16 months ahead of time.

In terms of the third goal, they established a strong Bahá'í group in each of the 20 countries in Central and South America, as well as 15 Local Spiritual Assemblies in the region.

Shoghi Effendi generously showered his pride, admiration, and gratitude on the Bahá'ís of the United States and Canada in a letter called “Unconquerable Power,” dated 12 August 1941.

In this letter, the Guardian expresses his gratitude at three accomplishments, the completion of the North American House of Worship, the steady expansion and consolidation of the Faith, and the spirit with which the Bahá'í community has faced and resisted its enemies.

The letter begins with this majestic sentence:

As I survey the activities and accomplishments of the American believers in recent months, and recall their reaction to the urgent call for service, embodied in the Seven Year Plan, I feel overwhelmed by a threefold sense of gratitude and admiration which I feel prompted to place on record, but which I cannot adequately express. Future generations can alone appraise correctly the value of their present services, and the Beloved, Whose mandate they are so valiantly obeying, can alone befittingly reward them for the manner in which they are discharging their duties.

Leroy Ioas standing next to some of the exquisite panels for the ornamentation of the Baha'i House of Worship in Wilmette, Illinois during its construction. Source: Brilliant Star Magazine.

As soon as the Guardian completed his monumental achievement of God Passes By, his very first thought was for the Bahá'ís in Iran, Bahá'u'lláh’s long-suffering and persecuted followers in His native land.

Shoghi Effendi began composing a one-hundred-year survey of the history and achievements of the Bahá'í Faith in Iran, the cradle of the Faith in the form of a lengthy and momentous letter to the Iranian Bahá'í community on the occasion of Naw-Rúz 101 B.E. (1944). The Tablet, however was not sent to the Bahá'ís in Iran on Naw-Rúz, but rather solemnly read at Riḍván, in a solemn pilgrimage ceremony at the House of the Báb in Shíráz. That story can be found in the section on the Centennial commemoration in Shíráz, on 23 May 1944

This letter has become known by Bahá'ís as Lawḥ-i-Qarn (لوح قرن), which means "Tablet of the Centennial,” which is how we will refer to it, but it is important to know that this was not a title Shoghi Effendi gave to his Naw-Rúz letter. The Guardian’s written Persian was high, classical, and sprinkled with Arabic and as different to spoken Persian as spoken English is to Shakespeare.

Shoghi Effendi would chant passages of Tablet of the Centennial to Rúḥíyyih Khánum, in his plaintive, painfully beautiful voice, and, like in English, his words flowed majestically, and their perfection and power was obvious to her, even if she only understood three words of out ten.

Sometimes, Shoghi Effendi hit a block, a word he couldn’t gracefully fit into the sentence, for example, and he would stop chanting. Then, he would start chanting that sentence from the start, and would continue, repeat, chant and chant again until he found a way to fit the word or express the end of the thought, and then he would continue.

This is Rúḥíyyih Khánum describes this beautiful process of the Guardian chanting while composing:

It was like some wonderful bird trying out its melodies to itself, lost in its own world.

Two of the greatest contemporary scholars of Persian literature, Badiozzaman Forouzanfar (Wikimedia Commons) and Saeed Nafisi (Wikimedia Commons) who considered Shoghi Effendi’s Tablet of the Centennial an achievement in Persian literature.

The Tablet of the Centennial, like God Passes By, addresses the stunning 100 years of the history of the Bahá'í Faith, a history that defied persecution and oppression with tales of victory after victory, a history of spiritual joy, love and the growth of the Faith from a small band of Persian believers to a world-embracing four-continent-spanning vibrant community with worldwide Administrative Order.

Like its English counterpart, God Passes By, the Tablet of the Centennial was a vehicle showcasing the Guardian’s extraordinary interpretive capacity applied to the history of the Faith of Bahá'u'lláh, and to its Mission and apogee: the establishment of the Kingdom of God on earth.

The differences between God Passes By and the Tablet of the Centennial lie in their presentation. First, of course, the language. God Passes By was in English, and the Tablet of the Centennial was written in mixed Persian and Arabic. Second, the length. The Tablet of the Centennial ran nearly 28,000 words, one sixth of the word count of God Passes By. Third, the form. God Passes By was a published book, and the Tablet of the Centennial was a letter written to the Bahá'ís of Iran on the occasion of Naw-Rúz 1944, the first Naw-Rúz immediately following the 100 years of the Bahá'í Faith, the Bahá'í Year 101.

The Tablet of the Centennial is a masterpiece, acclaimed by two of the greatest contemporary scholars of Persian literature, Badiozzaman Forouzanfar and Saeed Nafisi, who considered Shoghi Effendi’s Tablet of the Centennial an achievement in Persian literature.

The Tablet of the Centennial is to Persian literature what God Passes By is to English literature. The eminent Bahá'í scholar ʻAbdu'l-Ḥamíd Ishráq-Khávari devoted two volumes of commentary on the Lawḥ-i-Qarn (Tablet of the Centennial).

The Tablet of the Centennial is composed of a preamble, the body of the letter, and closing remarks.

The Guardian wrote the preamble to the Tablet of the Centennial entirely in Arabic, three pages of rare and exceptional beauty and poetic eloquence, in which Shoghi Effendi—in an homage to traditionally eastern etiquette of deep respect—first begins expressing salutation and praise to the names and attributes of God.

Shoghi Effendi’s preamble in Arabic is rhythmic, and, when read aloud, emits what Hand of the Cause Muḥammad Varqá describes as “a musical vibration,” beckoning the reader not to peruse the passage silently, but rather to chant it, and when chanted, the musicality of Shoghi Effendi’s Arabic, in Mr. Varqá’s words, becomes “a symphony that fills heart and soul, and when one begins to read them, one relishes, one savours every word..”

After this initial section, Shoghi Effendi lists not only The Báb’s, Bahá'u'lláh’s and 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s titles in the Bahá'í tradition, but also the titles and characterizations that apply to them from the prophecies of past religious Dispensations. These characterizations are short, and most of them are only two or three words long. In total, the Guardian characterizes Bahá'u'lláh with 36 titles and attributes, the Báb with 29, and 'Abdu'l-Bahá with 16.

Shoghi Effendi concludes the preamble by offering his wishes to the Iranian Bahá'í community and all those who arise to serve and assist the Faith of Bahá'u'lláh.

The content of the body of the letter is six pages in which the Guardian describes the importance of the first century of the Bahá'í Dispensation, including 8 paragraphs which begin with the same blessing:

How great the blessedness that pertains to this wondrous, this most marvellous century.

The next section of the Tablet of the Centennial recalls Shoghi Effendi’s writing in God Passes By: he draws a skillful and magisterial panorama of the history and development of the faith of Bahá'u'lláh, a magnificent procession of the events unfolding over the period of a hundred years.

The Guardian briefly draws a sketch of the key events of the ministries of the Báb, Bahá'u'lláh, and 'Abdu'l-Bahá.

Some of the events the Guardian mentions in the Báb’s Ministry are His Declaration, the Letters of the Living, their missions, the Báb’s pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina, his return and subsequent persecutions, His imprisonment in Máh-Kú and Chihríq, and finally His martyrdom.

The Guardian then describes Bahá’u’lláh’s ministry and His persecutions, His efforts to reunite and guide the disciples of the Báb, His imprisonment, His Revelation in the Siyáh-Chál, His exile to Baghdad, His self-imposed seclusion in Sulaymáníyyih, His return to Baghdad and His Declaration in the Garden of Riḍván, the inauguration of the Bahá'í Dispensation, and His last three exiles to Istanbul, Edirne and 'Akká, the intrigues of the Covenant-breakers, and His Revelation of the Kitáb-i-Aqdas.

When describing the ministry of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, the Guardian speaks about His Station as the Centre of the Covenant and His superhuman efforts in the expansion of the Faith of his Father throughout the globe, as well as His legacy-defining Journeys to the West.

Shoghi Effendi also details the tragic fate which all the enemies of the Bahá'í Faith suffered in the end.

At the end of this message, the beloved Guardian gave instructions for the pilgrimage of the Bahá'í friends in Iran, which took place at the exact time of the centennial, and in the exact room the Declaration took place.

The Guardian closes the Tablet of the Centennial with a beautiful prayer he revealed addressed to the Báb, Here is a provisional translation of this prayer by Dr. Khazeh Fananapazir:

O God, the Most High! We implore Thee by Thy Name and by Thy blood spread over the earth to grant our prayers and to enable us to nest under the shelter of Thy protecting wings and to shower upon us the rain of Thy generosity and Thy bounty. Assist and aid us to follow Thy path for love of Thee and draw us nigh unto the chord of Thy faithfulness and confirm us in Thy love and in the promulgation of Thy Message.

Preserve us from the darts of them that have denied Thee. Aid us to follow the pathway of Thy Will and to proclaim the Faith of Thy Best-Beloved, the Most Glorious, He in Whose path thou hast sacrificed Thyself, and for the sake of Whose love Thou hast wished for martyrdom.

Deliver us, O our Best Beloved, the Exalted, the Most High. Encourage us and make firm our steps. Forgive us our sins and expiate our trespasses, unloose our tongues, so that we may lift our voices and from our lips may flow Thy praise. Crown our deeds and our labours with the diadem of Thy grace. Make the end of our lives like unto that which Thou didst bestow on the faithful among Thy servants. We supplicate unto Thee to count us among them who have turned their faces unto Thee and have arisen in Thy service.

Intoxicate us with the glory of Thy presence, and render us immortal in the gardens of Thy holiness. Grant us the grace and bountiful favours of Thy heavenly Kingdom, O Thou Saviour of the world.

The servant at His threshold,

Shoghi

This is a perfect example of the difference between Shoghi Effendi’s eastern and western literary style. Please note this is a provisional translation by Dr. Khazeh Fananapazir.

In the following two paragraphs, the Guardian addresses himself to the night of the Báb’s Declaration herself in the most eloquent, love-filled invocations, expressions of mystical joy and communion, unlike anything the Guardian ever wrote in English:

O sacred and holy Night! Upon thee be the most perfect and most glorious greetings! Upon thee be the purest and most radiant salutations!

O solace of the Eye of Creation! O joyous Commencement of the Days of God! O Dawn of the most glorious and honoured Age and inception of the sacred and majestic Century!

Because of thy revelation, O Night, the most great portals were opened unto the face of creation, the most concealed Mystery did reveal Itself, the Most Pre-existent Light did shine forth. Through Thee the Straight Path was outstretched, and the breezes of life-giving Spirit were wafted forth unto all the nations.

Because of remembering Thee, Abraham, the Friend of God would rejoice in His inmost heart, and Moses the Interlocutor would be glad in His inmost being, and Jesus Christ the Spirit of God would be enthralled with His entire being, and Muḥammad the loved One would bestir Himself.

Because of Thy Advent the Concourse on High were joyous, and hallelujah’s of joy were raised from the cherubim, the saints, and the angels nigh unto God. Through Thee all earth and all the heavens were illumined, and in Thee all nights were resurrected, and from Thee all days sought light. The Night of Power circumambulated Thee. Because of thy advent, O Night, the Countenance of Existence wreathed into a smile!

During Shoghi Effendi’s ministry, there were three major centenaries which were celebrated throughout the world: the triple centenary of the Declaration of the Báb in 1944, the centenary of the Martyrdom of the Báb in 1950, and the centennial of Bahá'u'lláh’s Revelation in 1952.

The first centenary, was celebrated on 23 May 1844 and it was a triple centennial:

- It was the one-hundredth anniversary of the Declaration of the Báb.

- It was also the centenary of the birth of 'Abdu'l-Bahá.

- And lastly, it was the 100 years of the inception of the Bahá'í Cycle.

In the next few sections, we will honor the Bahá'í communities that were able to celebrate the Centennial:

First, of course at the Bahá'í World Centre, in the Holy Land.

Second, in Iran, in the cradle of the Faith, where the Guardian planned elaborate commemorations for the Centennial and the previous evening. Large and small communities in Iran organized marvelous celebrations, and we will also be looking briefly at those.

The seven other stalwart Bahá'í communities that had the privilege of organizing Centennial celebrations were of course first the two oldest Bahá'í communities in the West, the United States and Canada and the United Kingdom, and in alphabetical order: Australia, Egypt, India, Iraq, and Latin America.

A rare and sacred photograph of the inner sanctum at the heart of the Shrine of the Báb. Source: The Bahá'í World, Volume 10, frontispiece.

The Guardian had personally overseen all of the details of the celebration of the Centennial in the Holy Land, particularly the arrangement, design, decoration and arrangement of the interior of the Shrine of the Báb.

On 23 May 1944, over 150 Bahá'ís visited the International Bahá'í Archives. The commemoration began shortly after dusk, and the pilgrims visited the Shrines of the Báb in Haifa and of Bahá'u'lláh in Bahjí. They then gathered in the Eastern Pilgrim House and listened to the recording of 'Abdu'l-Bahá chanting a prayer, and watched the short film of the Master shot in 1912 in New York, which was followed by a spectacular color slide show of the completed House of Worship in Wilmette—the Mother Temple of North America—and activities around it.

During the Centennial, the Guardian announced for the first time that he had approved the design for the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb.

Members of the National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá'ís of Iran, elected during the Centennial Annual Convention. Source: The Bahá'í World Volume 1o, page 250.

‘Alí-Akbar Furútan read the Tablet of the Centennial to the Bahá'ís, Convention delegates, and National Spiritual Assembly gathered in the House of the Báb in Shíráz on the evening before the commemoration.

Dr. Adel Shafipour’s grandfather was present at this historic event, and stated that many of the delegates loudly responded with “amr javán shud!” [The Cause has been rejuvenated!]. This comment about the rejuvenation of the Faith is directly related to the event commemorating the Faith’s first 100 years.

The next evening, they gathered again and all those present performed the rites of pilgrimage around the House of the Báb as prescribed by Bahá'u'lláh.

At exactly two hours and eleven minutes after sunset, the precise moment of the Báb’s Declaration one hundred years ago, the opening chapter of the Qayyúmu'l-Asmá', the commentary of the Súrih of Joseph was chanted, in the same room and at the same time as the Báb had first chanted it as He revealed it to Mullá Ḥusayn, at the time the only Bábí in the entire world.

The All-American commemoration of the Centenary of the Bahá'í Faith: a view of Bahá'ís gathered in the auditorium at 8:00 PM on 22 May 1944, after the seats in the Foundation Hall were completely filled. A public address system reproduced the program for the overflow audience. The Bahá'í World Volume 10, page 180.

The Central and South American countries which were able to send a representative to the All-American Centennial were: Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Jamaica, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, San Domingo, Uruguay, Venezuela.

The program was a week long and included many public events and conferences. The Bahá'í program for the evening of the Centennial on Monday 22 May 1944 began with four talks at 8:00 PM. Then came the Dedication of the Bahá'í House of Worship, with prayers and readings and an excerpt from 'Abdu'l-Bahá on the importance of the Mashriqu’l-Adhkár.

The Commemoration of the Declaration itself took place 20 minutes after the Dedication of the Temple, at 10:00 PM, and began with prayers from the Báb, the words of f Jesus Christ, and one from the Prophet Muḥammad.

Left: Centenary Exhibition held in Bradford, Yorkshire, England in May 1944, showing the exterior view of the shop window on one of the main streets. Right: Interior view of the Bahá'í Centenary Exhibition held in Bradford England in May 1944. Dr. John E. Esslemont’s photograph can be see on the wall display on the right side of the image. Source: The Bahá'í World Volume 10, pages 191 and 193.

The Guardian himself stated that the commemoration of the Centennial in London was the second most outstanding event in the history of the Bahá'í Faith in the United Kingdom since the visits of 'Abdu'l-Bahá in 1911 and 1913.

Sir Ronald Storrs—former Military Governor of Jerusalem and current member of the London County Council—had known 'Abdu'l-Bahá personally and agreed to give the opening address of the Centennial celebration, an act the Guardian applauded as noble and courageous.

The festivities lasted a week and included several public meetings. There was an exhibition hall was decorated with large photographs of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, an exquisite specimen of calligraphy by Mishkín-Qalam—the renowned Bahá'í calligrapher—and other photographs of the Bahá'í House of Worship in North America, Dr. Esslemont, and 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s visits to England as well as an impressive display of Bahá'í literature, most notably the translation of Dr. Esslemont’s Bahá'u'lláh and the New Era in 33 languages.

The dedication of the Bahá'í National Center for Australia and New Zealand marking the opening of the Centenary Convention in Sydney, Australia on 20 may 1944. Source: The Bahá'í World Volume 10, page 227.

The National Bahá'í Center of Australia was dedicated on 21 May 1944, during National Convention, which took place from 19 to 24 May 1944. Wartime travel restrictions notwithstanding, all the Bahá'í delegates were present at Convention.

Clara Dunn spoke about her meeting ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and pioneering to Australia with her husband, Hyde Dunn—who passed away three years prior in 1941. Clara and Hyde Dunn were the first two people to bring the Bahá'í Faith to Australia in 1919, in response to 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s momentous Tablets of the Divine Plan.

On Tuesday 23 May 1944, the Convention delegates and Bahá'í friends were the guests of the Guardian at a buffet dinner at the Pickwick Club in Sydney. After dinner, photographers took pictures and there were several eloquent addresses.

The Local Spiritual Assembly of Auckland, New Zealand organized a Bahá'í Centenary Banquet attended by 300 people.

Top: Delegates attending the 21st Annual Convention of the Bahá'ís of Egypt and the Sudan held in Cairo, 20 – 21 May 1944. Bottom: Women attending the Centenary event in Cairo. Source: The Bahá'í World Volume 10, pages 209 and 210.

The National Spiritual Assembly of Egypt organized four programs of celebration for the Centennial on evening on the early and late evenings of Monday 22 May, and on the morning and evening of Tuesday 23 May 1944. The programs included prayers, messages from the Guardian including an excerpt from God Passes By on the first century of the Faith, an account of the life of Ṭáhirih, and several speeches.

Five hundred people, Bahá'ís and non-Bahá'ís, men, women, and children, rich and poor attended the wonderful celebrations. People came from all over Egypt and were housed in hotels, and in Bahá'í homes. Because so many people attended, the National Spiritual Assembly had large tents pitched on the grounds of the National Center where refreshments and banquets were served during the days of the celebrations.

Left: Delegates and Friends attending the Annual Convention of the Baha'is of India and Burma held at Bombay, May 28, 1944, following the Centenary Celebrations. Right: The Bahá'í Center of Karachi (now in Pakistan), illuminated for the Centenary between 24 – 26 May 1944. Source: The Bahá'í World Volume 10, pages 205 and 203.

The national Centennial celebrations in India took place in Bombay—today’s Mumbai— and were widely advertised in the media.

The National Spiritual Assembly sent out 5,000 invitations, posted 1,000 posters in the city of Bombay, and nine leading cinemas displayed a slide for the upcoming Centennial every day for the week preceding the event. They also printed 15,000 copies of the Guardian’s work The World Religion—this could be Shoghi Effendi’s 1933 essay “The World Religion,” an 8-paragraph introduction to the Bahá'í Faith’s aims, teachings and history—500 pamphlets about Martha Root’s services to India, 500 copies of the first 50 years of the Bahá'í Faith in India, and 5,000 copies of K.T. Shad’s Religion of the Future, which were all given away.

The Bahá'ís drummed up so much publicity for the event that a News Film of the Government of India, the India News Parade, filmed the events. On the night of the Centennial—23 May—the Bahá'ís gathered together. The National Spiritual Assembly, National Convention Delegates and Bahá'ís met at the beautifully decorated and brilliantly lit Bombay Bahá’í hall.

At 2 hours and 11 minutes after sunset, the packed hall fell silent, and the program began: a prayer by the Báb, Bahá'u'lláh’s Summons to the Lord of Hosts, the Súriy-i-Mulúk, an excerpt from the Persian Bayán, a Tablet revealed by Bahá'u'lláh on the Declaration of the Báb, and a talk on the significance of that day.

Top: The Bahá'ís of Baghdad and representatives of other centers in Iraq celebrating the Centenary of the Declaration of the Báb on 22 May 1944, held in conjunction with the Annual Convention. Bottom: The Bahá'í women of Baghdad, Iraq, celebrating the Centenary. Source: The Bahá'í World Volume 10, pages 219 and 221.

The National Bahá'í Center was a sight to behold. Its walls were decorated with priceless Persian rugs, the twelve major principles of the Faith, written in very large script on white linen sheets hung on the front walls of the guest house, welcoming the visitors. The Foundation hall was filled with sofas and chairs, and the entire center was flooded with light.

30 minutes after sunset, the opening prayer was said.

35 minutes after sunset, someone read verses from the Qur’án.

50 minutes after sunset, there was a reading from the New and Old Testament.

1 hour and 20 minutes after sunset, the Guardian’s message to the Centennial in Iraq was read in which he stated that he appreciated “their sincerity and fidelity,” took “pride in their endeavors and activities,” shared with them “in their pleasures and exhilaration,” and supplicated “unto God the Almighty to keep them in the stronghold of His protection and watchfulness and to confirm them in the diffusion of His fragrances and make their feet firm in His path, and enable them to elevate and glorify His Faith and render them victorious over their enemies and to realize their wishes in the service of His most glorious and wonderful, most holy, and most inaccessible Faith.”

1 hour and 40 minutes after sunset, Chapter III in Nabíl’s Narrative’s concerning the Declaration of the Báb was read.

2 hours and 10 minutes after sunset, everyone rose to their feet, silently, solemnly, and reverently, and these words from Nabíl’s Narrative were read:

This night, this very hour will, in the days to come, be celebrated as one of the greatest and most significant of all festivals. Render thanks 62 to God for having graciously assisted you to attain your heart’s desire, and for having quaffed from the sealed wine of His utterance.

At exactly 2 hours and 11 minutes after sunset, the Bahá'ís were solemnly seated, and utterly quiet. All the Bahá'ís of Baghdad were present, as well as all the delegates of the Fourteenth Annual Convention, and representatives from as many cities as possible: Mosul, Sulaymáníyyih, Karkfik, Khaniqayn, Ba’aqubih, Huvaydar, ‘Avéshiq, Idliybih, Laraban, Khirnabat, Abu-Saydih, ‘Aziziyyih, ‘Amarih, Mutavva’ah and Basrah.

At that exact moment, when 100 years ago that day the Báb declared His mission to Mullá Ḥusayn by beginning the revelation of the Commentary on the Súrih of Joseph of the Qur’án—the Qayyúmu'l-Asmá'—an excerpt of that same book was read to mark the occasion.

No photographs of Centennial Celebrations in Latin America were found. Here are four photographs of four communities in Central and South America. Top left: Youth of Lima, Peru. Top left: The first public meeting for youth held under the auspices of the Spiritual Assembly of Punta Arenas, Magallanes, Chile in July 1945. Bottom left: The first Bahá'í Youth Day meeting held in Guayaqui, Ecuador, 17 March 1943. Bottom right: Bahá'ís and friends of the Faith in San Salvador, El Salvador. Source: The Bahá'í World Volume 10, pages 439, 461, 465, and 553.

The Bahá’ís of Haiti organized many festivities for the Centennial from 19 to 25 May, the same span of time as the All-American Centennial. Their meetings in French included prayer, one included the singing of the Haitian National Anthem, there were talks and lectures on the life of the Báb, readings from Bahá'u'lláh and the New Era, and refreshments were served at every occasion.

The Local Spiritual Assembly of Havana did a wonderful job publicizing their events, and they organized a highly successful meeting at their Bahá'í Center.

The Local Spiritual Assembly of Buenos Aires, Argentina—the site of May Maxwell’s memorial shrined—arranged a well-publicized, beautiful program of several days of festivity. The program for the Centennial consisted of an opening address on the Báb, readings from the Báb’s writing, three further addresses on the Bahá'u'lláh, 'Abdu'l-Bahá, and the Guardian.

In Chile, Marcia Steward, an isolated pioneer in the southernmost city on earth, Punta Arenas, held a prayer vigil to mark the solemn occasion.

The Bahá’ís of La Paz, Bolivia centered their attention upon a tribute that would be both of immediate interest and of permanent contribution to the teaching work. They prepared widely distributed a commemorative booklet of prayers in Spanish carefully selected to bring comfort to young and old, to people of culture and education, and to those whose education had been limited. An article about the Centennial was published in the local newspaper. At two hours and eleven minutes after sunset, a talented Bahá'í spoke on the radio. The Bahá'ís commemorated in a reverent event that included prayers and readings from the Bahá'í Writings in honor of the Declaration of the Báb and the birthday of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, and an address titled “The Great Announcement.”

Shoghi Effendi typed three carbon copies of each page, and at night, he and Rúḥíyyih Khánum sat side by side at his large bog wood table in his bedroom, each with their own triplicate copies of manuscript pages, adding by hand all the transliterated accents: the underlined dh, kh, sh, the uderdots of ḍ, ḥ, ṣ, ṭ, and ẓ, the acute accents á and í.

Do you know how many diacritics there are in God Passes By?

There are 9,537.

The Guardian of the Faith, and the Hand of the Cause Amatu’l-Bahá Rúḥíyyih Khánum personally, manually added three times that many accents on the triplicate typed manuscripts of God Passes By, which means they added 28,611 accents by hand, late into the night, while Shoghi Effendi was reading the words out loud in Persian, so they both knew how to transliterate each one.

They added 28,611 accents until their eyes were bloodshot, until their vision was blurry, until Shoghi Effendi’s back and arms were stiff with exhaustion.

But it had to be done, and they were the only two people on the planet who could do it, so they did, and they persevered and suffered through the 173,681 words of God Passes By, until they were done.

Batch by batch, that was how the manuscript of God Passes By was typed, edited, corrected, and sent piecemeal to Horace Holley, the secretary of the National Spiritual Assembly of the United States and Canada.

Shoghi Effendi worked continuously on God Passes By for two years, from 1942 to 22 January 1944, when the last remaining pages—corrections for the section “Prospect and Retrospect”—were mailed to Horace Holley in the United States for publication.

By this point, both Shoghi Effendi and Rúḥíyyih Khánum were spent, utterly exhausted.

For two years, they had referred to Shoghi Effendi’s manuscript as “the book,” sometimes Rúḥíyyih Khánum referred to it as Shoghi Effendi’s “manuscript” or even “the Centennial Review,” Shoghi Effendi himself at times called it a “review” or a “survey,” but it did not yet have a name.

This is the story of how God Passes By got its name.

The Guardian asked George Townshend to come up with a title for his manuscript.

The rest of this story comes from former member of the Universal House of Justice and eminent Bahá'í historian Adib Taherzadeh who was a member of the Irish Bahá'í community, who had a long-standing friendship Irish Hand of the Cause George Townshend, where they would discuss spiritual matters.

George Townshend told Adib Taherzadeh:

I did not know what to do.

And so, George Townshend didn’t do anything.

Shoghi Effendi sent George Townshend cables, pressuring him to title the manuscript, asking him to give it a name, asking him to expedite.

But nothing came to George Townshend. He was not inspired.

Message after message, cable after cable came from Shoghi Effendi, and finally, George thought to himself, “Well, I must send a telegram to Shoghi Effendi, give a name to this book. What shall I call it?”

George got on his bike, and started riding in Ahascragh, towards the only reliable post office, in the center of Dublin—about 16 kilometers away from his home—still with no idea what he was going to write to Shoghi Effendi. He still did not have a title for the book.

As he was biking towards the telegram he needed to send his Guardian, the Irish landscape passing him by, and inspiration finally came to him in the form of three simple words, three simple syllables.

A road passing by Ahascragh, where George Townshend was cycling, seeing the world blur past him when he thought of the title: God Passes By.

George arrived at the post office and cabled the Guardian:

GOD PASSES BY

Shoghi Effendi immediately replied

DELIGHTED TITLE. EAGERLY AWAITING LETTER.

The title God Passes By is an English gem. Its exact meaning cannot be adequately translated into any other language.

What is implied in the words God Passes By is that God moved in close proximity to us, and we didn’t notice. There is a subtlety in the title, of God having been so near to us, but we only realized it later, with the passage of time.

The French translation, Dieu passe près de nous, literally translates in English as God passes close to us.

The Spanish translation, Diós pasa, means God passes.

No translation comes close to the spiritual intimacy of the English, God Passes By.

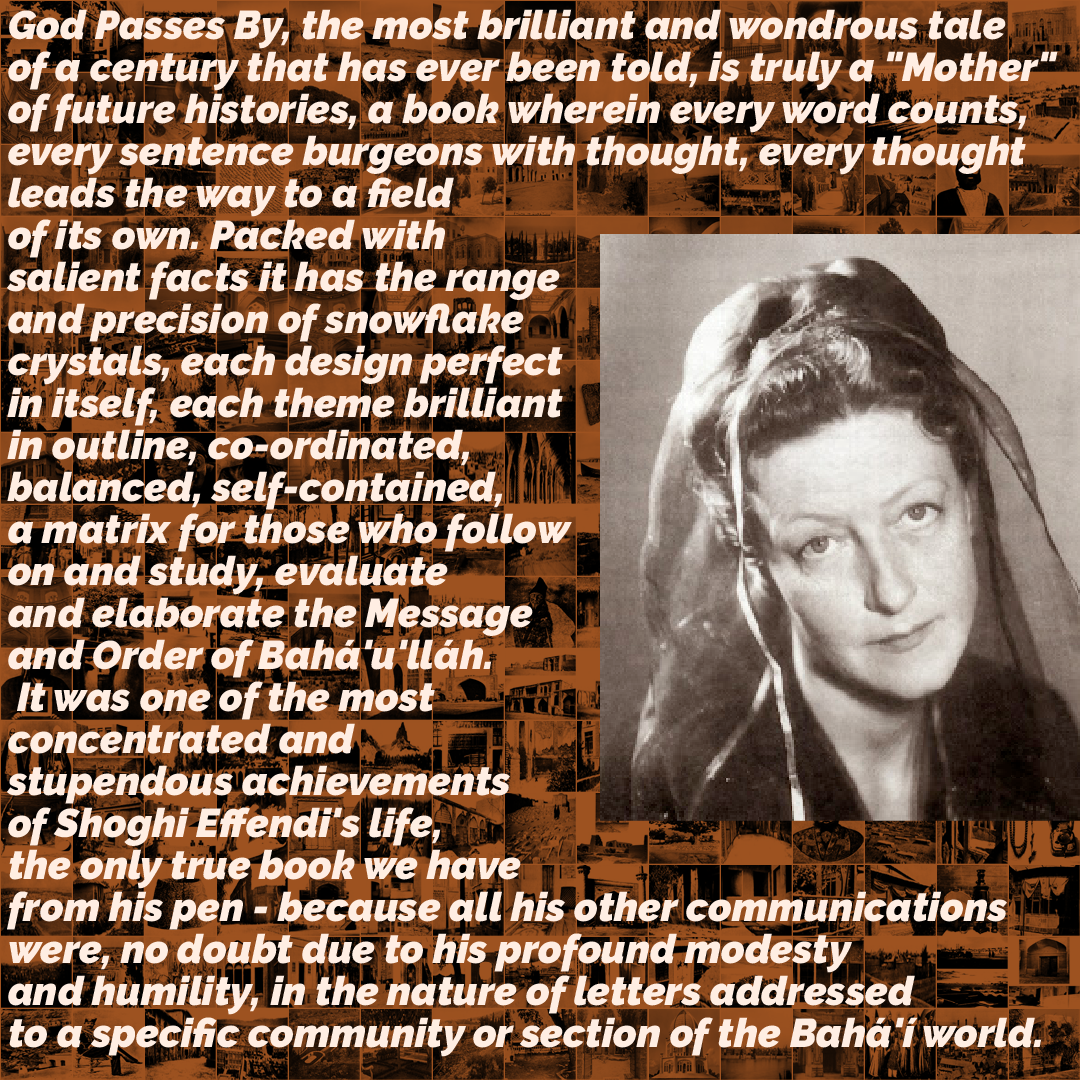

Portrait of Rúḥíyyih Khánum. Source: We are Bahá'ís.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum called God Passes By “a veritable essence of essences,” arguing that Shoghi Effendi’s masterpiece was such an ultra-condensed, super-rich distillation of Bahá'í history that 50 books on Bahá'í history could easily be written from it, every single one of them a profound, rich study of one of the aspects of the Faith.

Shoghi Effendi wrote God Passes By, a spiritual, exceedingly beautiful literary gift, at a time when Nazis were exterminating Jews, Gypsies and other minorities across Europe, at a time when the armies of the world were battling on the western, the Russian and the North African fronts, when both the United States and Japan had already entered the theater of war,

This is Rúḥíyyih Khánum’s phenomenal description of God Passes By:

God Passes By, the most brilliant and wondrous tale of a century that has ever been told, is truly a "Mother" of future histories, a book wherein every word counts, every sentence burgeons with thought, every thought leads the way to a field of its own. Packed with salient facts it has the range and precision of snowflake crystals, each design perfect in itself, each theme brilliant in outline, co-ordinated, balanced, self-contained, a matrix for those who follow on and study, evaluate and elaborate the Message and Order of Bahá'u'lláh. It was one of the most concentrated and stupendous achievements of Shoghi Effendi's life, the only true book we have from his pen - because all his other communications were, no doubt due to his profound modesty and humility, in the nature of letters addressed to a specific community or section of the Bahá'í world.

The current edition of God Passes By is 412 pages long, and Shoghi Effendi included 1,945 quotations in the book, most of them from Bahá'u'lláh and 'Abdu'l-Bahá. Of these 1,945 quotations, 41 of them run a full page or more in length

God Passes By begins with an 11-paragraph Foreword by Shoghi Effendi—George Townshend’s introduction is no longer included in current editions of the book.

In the Foreword to God Passes By, the Guardian lays out what awaits the reader, but first, he emphasizes the importance of the triple centenary of 23 May 1944, the culmination of a universal prophetic cycle:

On the 23rd of May of this auspicious year the Bahá’í world will celebrate the centennial anniversary of the founding of the Faith of Bahá’u’lláh. It will commemorate at once the hundredth anniversary of the inception of the Bábí Dispensation, of the inauguration of the Bahá’í Era, of the commencement of the Bahá’í Cycle, and of the birth of ‘Abdu’l‑Bahá.

Over the next two paragraphs, Shoghi Effendi casts a general glance at the spiritual forces generated by the first 100 years of the Bahá'í and the emergence of Bahá'u'lláh’s embryonic World Order and their effect on the world.

In paragraphs 4, 5, and 6, Shoghi Effendi explains not only his purpose for writing God Passes By, and what the book represents, but he also cautions the readers on what God Passes By is not: Shoghi Effendi did not intend it to be a detailed history of the last hundred years of the Bahá’í Faith, and he did not intend to study in detail the origins of the Faith, the social conditions in which it appeared, its character or to examine in detail its impact on human society.

Paragraphs 7 through 10 are majestic descriptions of the content of God Passes By, the first three epochs of the Heroic Age and the first epoch of the Formative Age and their descriptions, with long descriptions of each of the four parts of the book, culminating in a very long final paragraph in which the Guardian lays out the procession of historic events contained in the remainder of the book.

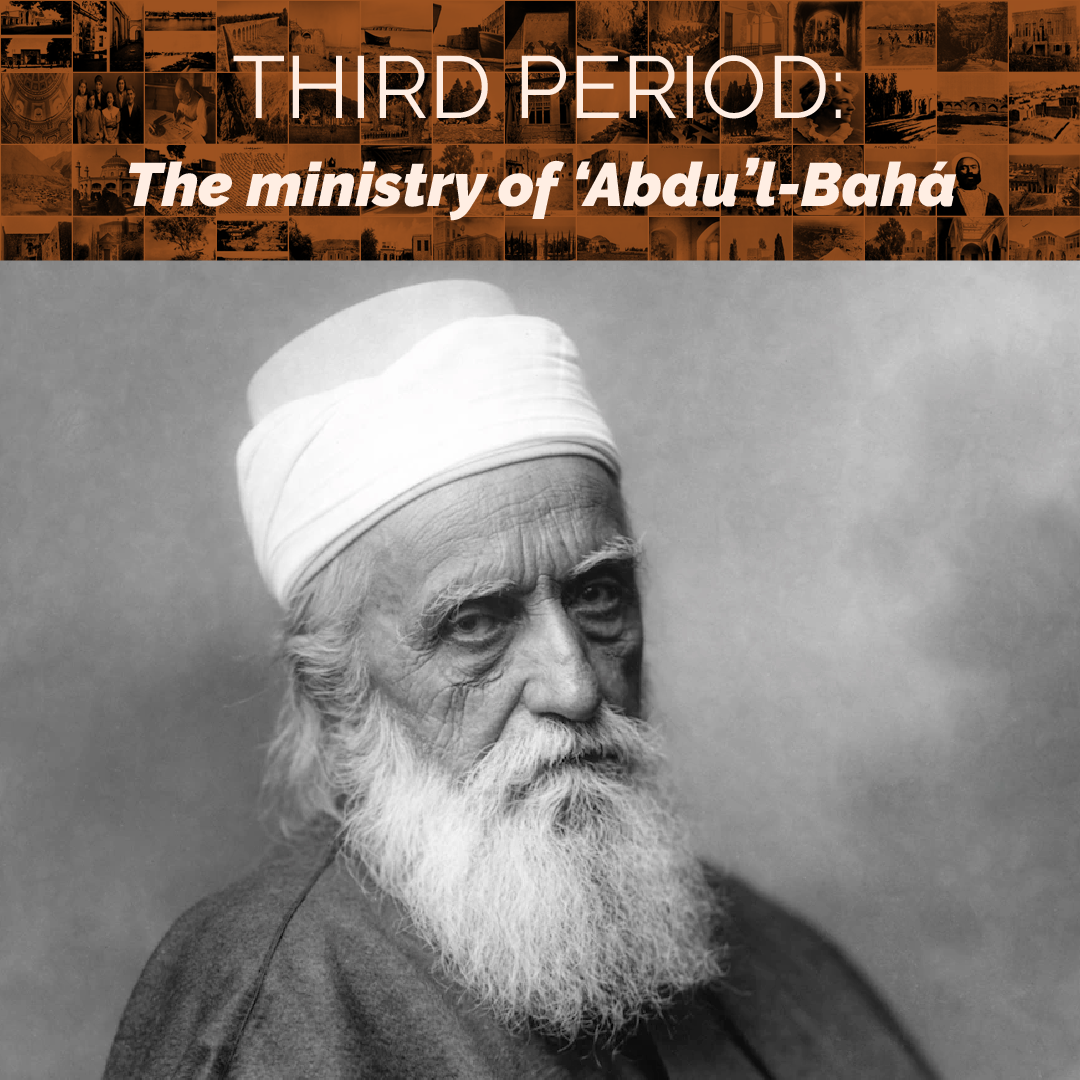

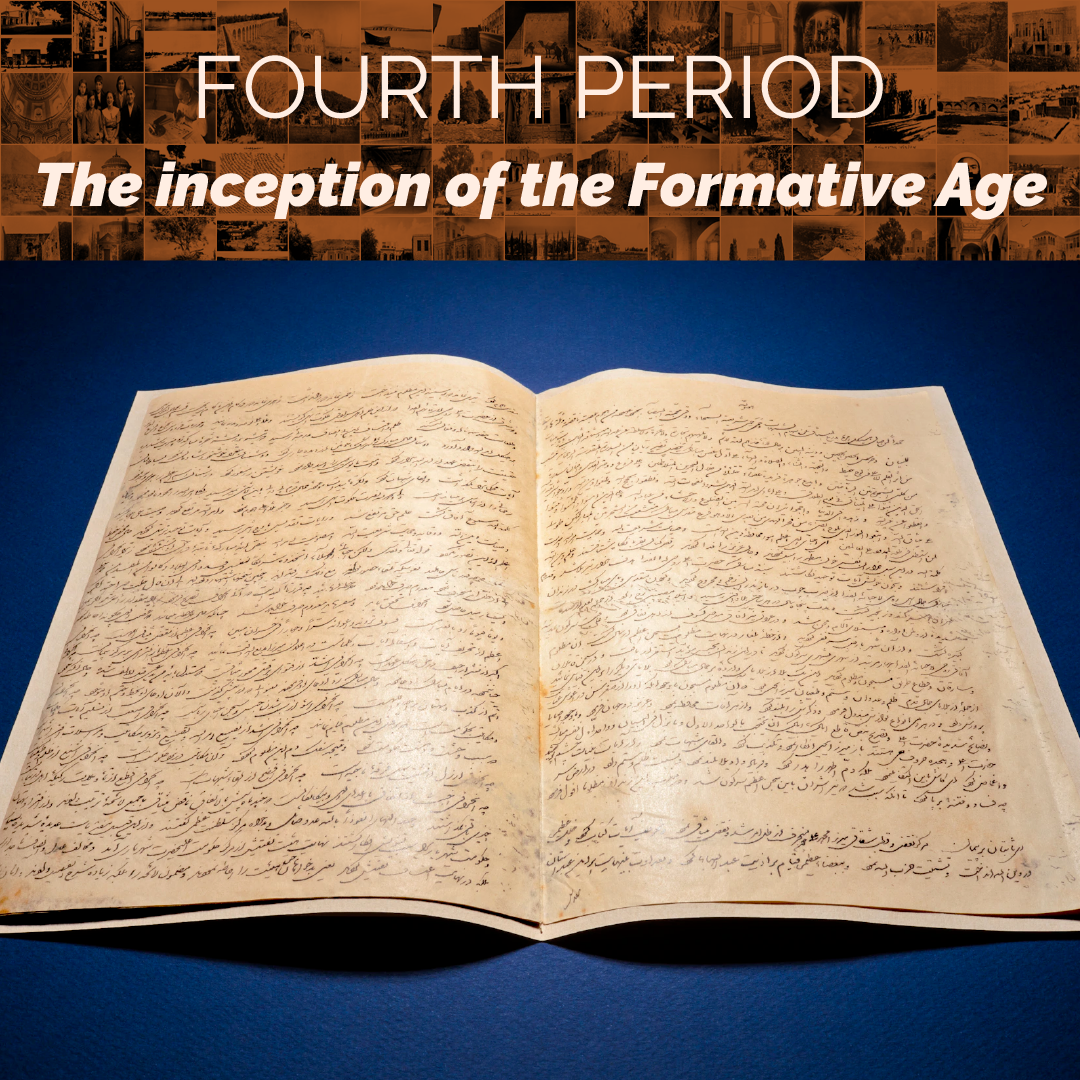

Shoghi Effendi divided the contents of the first 100 years of Bahá'í history into four periods:

- First Period: The Ministry of the Báb 1844–1853;

- Second Period: The Ministry of Bahá’u’lláh 1853–1892;

- Third Period: The Ministry of ‘Abdu’l‑Bahá 1892–1921;

- Fourth Period: The Inception of the Formative Age of the Bahá’í Faith 1921–1944.

Below are four very short summaries of each of these periods:

Shoghi Effendi begins his history of the 9 years of the Báb’s ministry with His Declaration, the story of the Letters of the Living, the Báb’s pilgrimage and public declaration in Mecca Medina, his return to Shíráz, his stay in Iṣfahán and his imprisonment in Máh-Kú and Chiríq. He also writes about the Báb’s Revelation of the Qayyúmu'l-Asmá' and the Bayán, His examination in Tabriz, and His martyrdom in that same city. Shoghi Effendi also takes time to set down in history three important things: the role Bahá'u'lláh played during the Báb’s ministry, the stunning parallels between the ministries of Jesus Christ and the Báb, and the names and tragic fates of all of the Báb’s enemies.

Shoghi Effendi begins his history of the 9 years of the Báb’s ministry with His Declaration, the story of the Letters of the Living, the Báb’s pilgrimage and public declaration in Mecca Medina, his return to Shíráz, his stay in Iṣfahán and his imprisonment in Máh-Kú and Chiríq. He also writes about the Báb’s Revelation of the Qayyúmu'l-Asmá' and the Bayán, His examination in Tabriz, and His martyrdom in that same city. Shoghi Effendi also takes time to set down in history three important things: the role Bahá'u'lláh played during the Báb’s ministry, the stunning parallels between the ministries of Jesus Christ and the Báb, and the names and tragic fates of all of the Báb’s enemies.

Shoghi Effendi also looks at the main events in the lives of the Bábí community while the Báb was imprisoned, such as the conference of Badasht and the major role Bahá'u'lláh played as its organizer. Shoghi Effendi lays out the opposition of the Shí’ah clergy to the Báb’s new teachings, describes in details the reprisals against the Bábís in 1849-1850 in Mázindarán, Nayríz, Zanján and the Seven Martyrs of Ṭihrán, and also tells the story of the three misguided Bábís attempt on the life of Naṣiri'd-Dín Sháh, the swift and bloody massacres that followed as repercussions.

Shoghi Effendi begins the second period of the Bahá'í Faith with an event that immediately followed the end of his story in the first period: the imprisonment of Bahá'u'lláh in the Siyáh-Chál as one of the repercussions of the attempt on the life of Naṣiri'd-Dín Sháh. Shoghi Effendi describes the Revelation Bahá'u'lláh received in the Siyáh-Chál, His first exile to Baghdad and how Bahá'u'lláh re-created the Bábí community of Baghdad, and his tremendous influence in Baghdad social circles.

After an extraordinary section describing the first stage of Bahá'u'lláh’s Proclamation of His Mission in the Garden of Riḍván, Shoghi Effendi describes Bahá'u'lláh’s unjustified second and third exiles, to Istanbul and Edirne. He speaks about Mírzá Yaḥyá’s attempt to assassinate Bahá'u'lláh, and describes in detail Bahá'u'lláh’s Tablets to the Kings and Rulers of the World, before speaking about Bahá'u'lláh’s fourth and final exile, in 'Akká.

Shoghi Effendi speaks about the conditions of Bahá'u'lláh’s incarceration in the Most Great Prison, the gradual relaxation of the restrictions imposed upon Him in the years when Bahá'u'lláh lived in 'Akká, until 'Abdu'l-Bahá succeeded in renting for His Father the Mansions of Mazra’ih and Bahjí, where Bahá'u'lláh spent His final years in dignity.

Shoghi Effendi speaks about many of the Holy Writings revealed by Bahá'u'lláh, explaining their importance and their influence, notably the Kitáb-i-Aqdas. Shoghi Effendi explores the influence and effect of Bahá’u’lláh’s behaviour and Writings on the minds and hearts of those around Him, describes the days and weeks preceding and following His Ascension, and ends—as he had with the Báb—with a list of Bahá'u'lláh’s enemies and the divine chastisement that defined their demise and deaths.

In his outline of the Ministry of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Shoghi Effendi mainly focuses on four aspects of the life of 'Abdu'l-Bahá”

- His role and function as Centre of Covenant and Head of the Faith;

- The distinguishing features of His career;

- The revitalizing influence of his infallible guidance on the Bahá'í community

- 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s character and His accomplishments

- The Master’s achievement in establishing the first rudimentary institutions of the Faith.

Shoghi Effendi begins his exploration of the ministry of 'Abdu'l-Bahá with an explanation of the significance of the Kitáb-i-Ahd, the Book of Bahá'u'lláh’s Covenant appointing 'Abdu'l-Bahá the Center of the Covenant. Then, Shoghi Effendi reviews 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s important role during the ministry of Bahá'u'lláh, the arrival of the first western pilgrims to 'Akká, the activities of the most infamous Covenant-breaker of 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s ministry, His half-brother, Mírzá Muḥammad-'Alí. The activities of the Covenant-breakers resulted in 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s re-incarceration in 'Akká, and a Commission of Inquiry was sent from Istanbul to investigate their malicious rumors regarding the Shrine of the Báb which 'Abdu'l-Bahá was building on Mount Carmel.

In this section, Shoghi Effendi relates the persecution of the Bahá’í community in Persia, describes the construction of the first Bahá’í House of Worship in ‘Ishqábád, the erection of the Shrine of the Báb, and the momentous event of 'Abdu'l-Bahá finally laying His remains to rest after 59 years.

Following the Young Turk Revolution, 'Abdu'l-Bahá was finally free and Shoghi Effendi describes in detail His Journeys to the West, underlining their great importance, and the effect 'Abdu'l-Bahá had throughout His travels in Egypt, France, Switzerland, the United States, Canada, England, Scotland, Germany, Hungary and Austria.

Upon 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s return to the Holy Land, Shoghi Effendi recalls His activities during World War I, and His Knighthood for services rendered to the British Crown. The two words that Shoghi Effendi highlights in his section on the Ministry of 'Abdu'l-Bahá are His Will and Testament and the Tablets of the Divine Plan. Finally Lastly, Shoghi Effendi recounts the Ascension of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, and, as in the first two section, he relates the fate of the few remaining enemies of 'Abdu'l-Bahá.

This period addresses the ministry of Shoghi Effendi, but in the Guardian’s characteristic humility, he does not mention his name a single time in the 412 pages of

God Passes By, if you exclude his name on the first page, as author of the book.

The very first subject Shoghi Effendi tackles in his survey of the first epoch of the Formative Age, is the rise and establishment of the Bahá'í Administrative Order, drawing its origins straight from the Will and Testament of 'Abdu'l-Bahá. Shoghi Effendi begins by detailing why the Bahá'í Administrative Order is unique in the annals of religious history, and explains that the Formative Age is a period of gradual development in which the nascent Bahá'í Institutions will grow through a period of alternating crisis and victories, laying the foundation for Bahá'u'lláh’s Golden Age.

Shoghi Effendi amply demonstrates the futility of the Covenant-breakers efforts to destabilize the Faith after the passing of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, and lists their failures.

To show the growth accomplished in just 20 years, Shoghi Effendi lists extraordinary achievements by both Bahá'í institutions and Bahá'í individuals in the field of teaching and administration, in particular, the formation of Assemblies on a sound constitutional and legal basis, and official recognitions of the Bahá'í Faith— in particular the United States and an edict issued by ecclesiastical authorities in Egypt—but also the inauguration of the Mother Temple of the West, publishing houses, summer schools.

Shoghi Effendi is generous and fair in his praise of accomplishments by individuals and national communities in the field of teaching, and he especially singles out the priceless services of Martha Root, as well as the contribution of the American Bahá’ís in spreading the Faith to all corners of the earth.

The Guardian ends God Passes By with a 14-paragraph conclusion called “Retrospect and Prospect” in which he reviews the salient episodes that marked Bahá'í history in the last 100 years (Retrospect), while he looks ahead to the future development of the Bahá'í Faith (Prospect).

Shoghi Effendi has a particularly elegant and apt description for the advancement of the Faith in this section. He not only describes the spiritual nature and characteristics of this process, but he traces it methodically from Persia to Iraq, to the Holy Land to every continent in the world, in a single, achingly beautiful sentence:

A process, God-impelled, endowed with measureless potentialities, mysterious in its workings, awful in the retribution meted out to every one seeking to resist its operation, infinitely rich in its promise for the regeneration and redemption of human kind, had been set in motion in Shíráz, had gained momentum successively in Ṭihrán, Baghdád, Adrianople and ‘Akká, had projected itself across the seas, poured its generative influences into the West, and manifested the initial evidences of its marvelous, world-energizing force in the midst of the North American continent.

Shoghi Effendi’s overarching understanding of the Faith’s history and his far-reaching vision of its future may be glimpsed in the quote provided below:

Whatever may befall this infant Faith of God in future decades or in succeeding centuries, whatever the sorrows, dangers and tribulations which the next stage in its world- wide development may engender, from whatever quarter the assaults to be launched by its present or future adversaries may be unleashed against it, however great the reverses and setbacks it may suffer, we, who have been privileged to apprehend, to the degree our finite minds can fathom, the significance of these marvelous phenomena associated with its rise and establishment, can harbor no doubt that what it has already achieved in the first hundred years of its life provides sufficient guarantee that it will continue to forge ahead, capturing loftier heights, tearing down every obstacle, opening up new horizons and winning still mightier victories until its glorious mission, stretching into the dim ranges of time that lie ahead, is totally fulfilled.

God Passes By is finally published and advertised for sale at $2,50 a copy in Bahá'í News, Issue 172: December 1944 on page 7.

The Guardian had originally intended God Passes By to be published on time for the Centennial celebrations on 23 May 1944, and he had mailed the final manuscript to the United States on time. Although it progressively became obvious to Shoghi Effendi that his intended publication date would not be met, he still urged the book be published as soon as possible.

In a letter dated 28 July 1944, the Guardian’s secretary informed George Townshend about the publication delay citing several reasons, but noting that it was a miracle God Passes By had been completed in the middle of World War II:

Owing to pressure of priority work in the States God Passes By will not be delivered by the printer until after the end of August. The Guardian was sorry the book could not be gotten out in time for the Centenary; but such things cannot be avoided in wartime, and the real miracle is that the manuscript should have gone to you and been returned and gone out again to the USA and been safely received! Proofs have been given, however, for use in special courses of the Bahá’í Summer Schools. He thought you would like to know these things, after all the pains you took with the manuscript.

God Passes By did not make it off the printing press until 15 November 1944.

The first edition of God Passes By cost was $2.50, it was 436 pages and bound in dark red fabrikoid, a synthetic leather made from coated cotton.

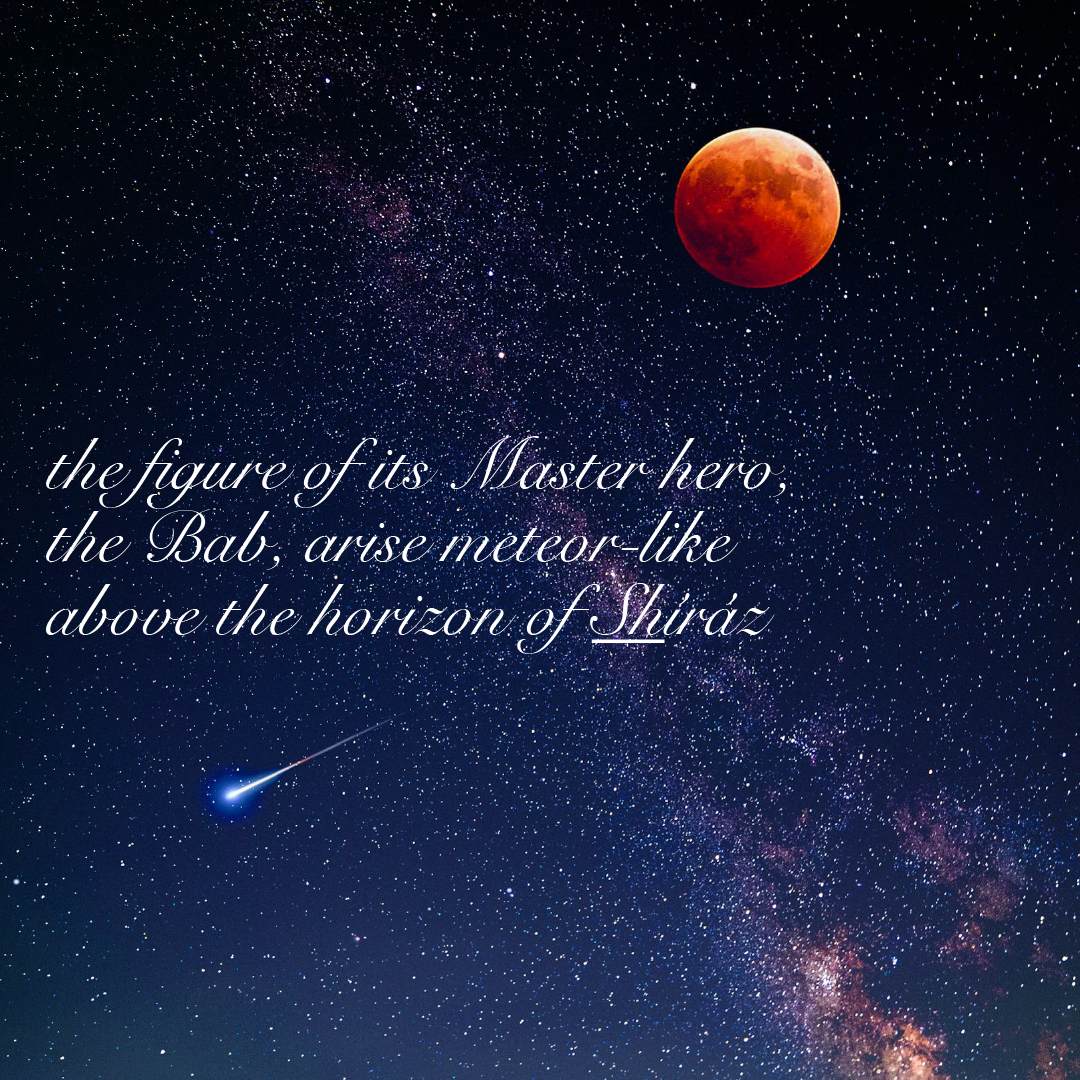

There is no more perfect example of Shoghi Effendi’s mastery of dramatic prose than the majestic opening paragraph of God Passes By, comparing the Báb to a meteor, lighting the dark skies of Persia:

May 23, 1844, signalizes the commencement of the most turbulent period of the Heroic Age of the Bahá’í Era, an age which marks the opening of the most glorious epoch in the greatest cycle which the spiritual history of mankind has yet witnessed.

No more than a span of nine short years marks the duration of this most spectacular, this most tragic, this most eventful period of the first Bahá’í century. It was ushered in by the birth of a Revelation whose Bearer posterity will acclaim as the “Point round Whom the realities of the Prophets and Messengers revolve,” and terminated with the first stirrings of a still more potent Revelation, “whose day,” Bahá’u’lláh Himself affirms, “every Prophet hath announced,” for which “the soul of every Divine Messenger hath thirsted,” and through which “God hath proved the hearts of the entire company of His Messengers and Prophets.”

Little wonder that the immortal chronicler of the events associated with the birth and rise of the Bahá’í Revelation has seen fit to devote no less than half of his moving narrative to the description of those happenings that have during such a brief space of time so greatly enriched, through their tragedy and heroism, the religious annals of mankind. In sheer dramatic power, in the rapidity with which events of momentous importance succeeded each other, in the holocaust which baptized its birth, in the miraculous circumstances attending the martyrdom of the One Who had ushered it in, in the potentialities with which it had been from the outset so thoroughly impregnated, in the forces to which it eventually gave birth, this nine-year period may well rank as unique in the whole range of man’s religious experience.

We behold, as we survey the episodes of this first act of a sublime drama, the figure of its Master Hero, the Báb, arise meteor-like above the horizon of Shíráz, traverse the sombre sky of Persia from south to north, decline with tragic swiftness, and perish in a blaze of glory. We see His satellites, a galaxy of God-intoxicated heroes, mount above that same horizon, irradiate that same incandescent light, burn themselves out with that self-same swiftness, and impart in their turn an added impetus to the steadily gathering momentum of God’s nascent Faith.

Muníb Shahíd had a Bahá'í pedigree as eminent as it gets.

His grandfather was the King of Martyrs, the most illustrious of the Apostles of Bahá'u'lláh's, who was savagely killed with his brother, the Beloved of Martyrs.

His father was Munírih Khánum’s cousin, who had come to live in the Holy Land at Bahá'u'lláh’s invitation after their father was martyred.

His mother was Rúhá Khánum, the third daughter of 'Abdu'l-Bahá and Munírih Khánum.

He was the grandson of 'Abdu'l-Bahá and the great-grandson of Bahá'u'lláh.

He became an apostate to the Bahá'í Faith when he contracted a Muslim marriage instead of a Bahá'í marriage with a woman who was great-niece of the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem—an enemy of the Faith— and so doing forced Shoghi Effendi to denounce him publicly in a 7 November 1944 cable to the National Spiritual Assembly of the United States and Canada:

Moneeb Shaheed, grandson of both ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and the King of Martyrs, married according to the Moslem rites the daughter of a political exile who is nephew of the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem. This treacherous act of alliance with enemies of the Faith merits condemnation of entire Bahá’í world.