Written and illustrated by Violetta Zein

This part covers the life of Shoghi Effendi from the age of 54 in 1951 to the age of 55 in 1952.

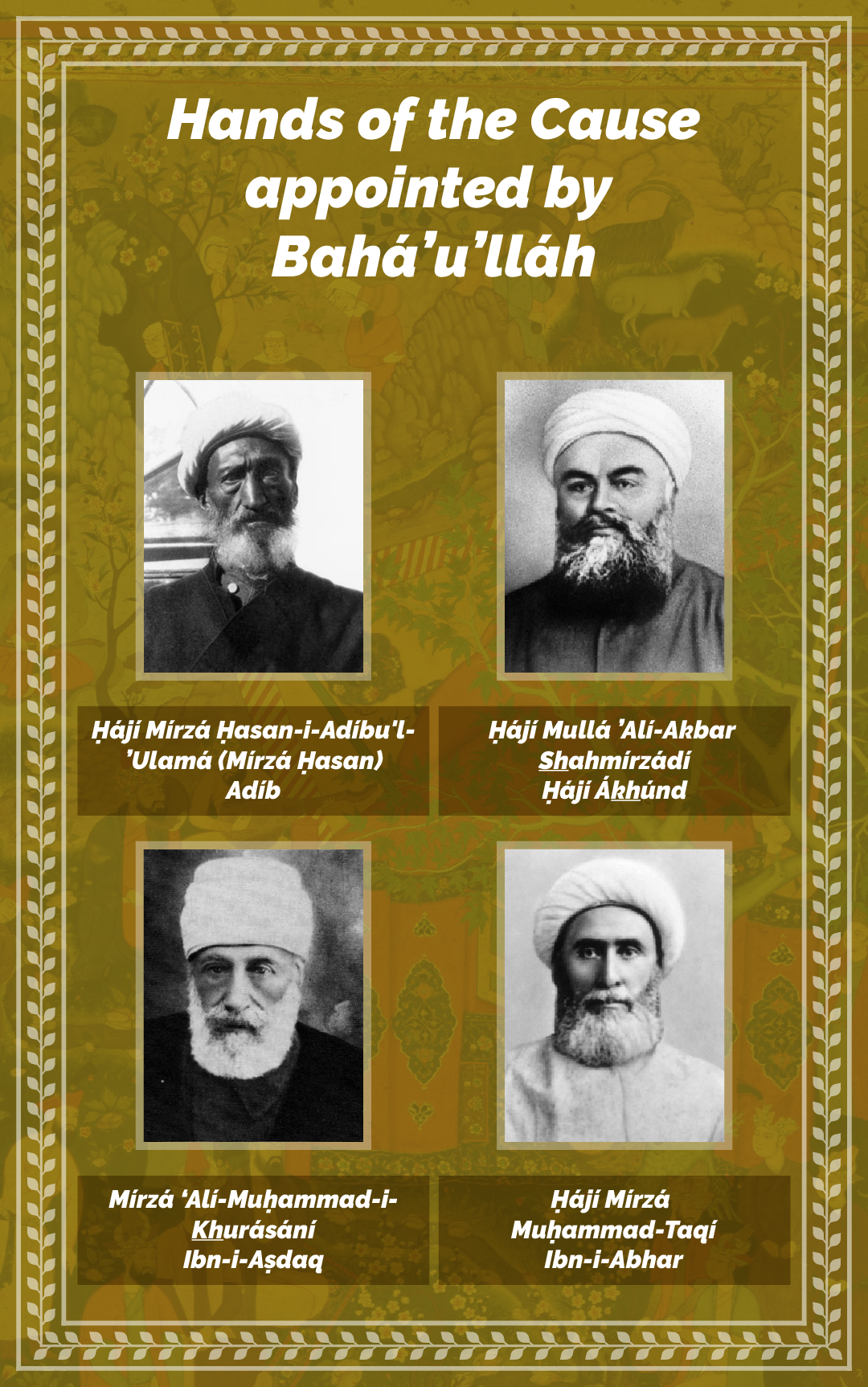

The four Hands of the Cause whom Bahá'u'lláh appointed during His lifetime. Background image: Persian miniature from The British Museum.

The station of Hand of the Cause was established by Bahá’u’lláh during in the Kitáb-i-Aqdas:

In this holy cycle the “learned” are, on the one hand, the Hands of the Cause of God, and, on the other, the teachers and diffusers of His Teachings who do not rank as Hands, but who have attained an eminent position in the teaching work.

and He Himself appointed four living Hands of the Cause—extraordinary believers—who carried out their dual task of propagating the Faith and protecting it:

- Ḥájí Mírzá Ḥasan-i-Adíbu'l-ʻUlamá, also called Mírzá Ḥasan, but better known as simply Adíb

- Ḥájí Mullá ʻAlí-Akbar S͟hahmírzádí, known as Ḥájí Ákhúnd

- Mírzá ʻAlí-Muḥammad-i-K͟hurásání, known as Ibn-i-Aṣdaq

- Ḥájí Mírzá Muḥammad-Taqí, known as Ibn-i-Abhar

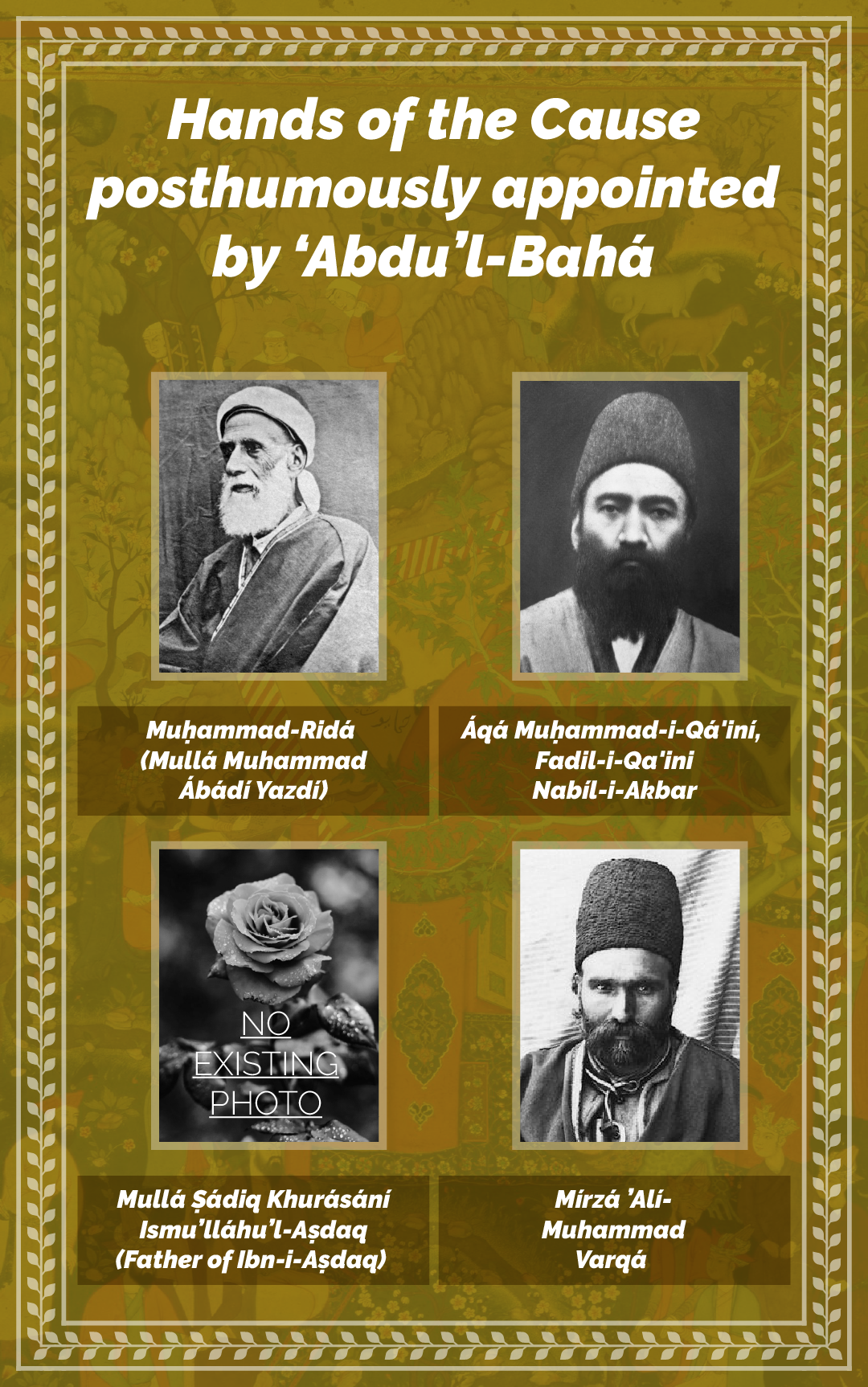

The four Hands of the Cause whom 'Abdu'l-Bahá appointed during posthumously in 1915. Background image: Persian miniature from The British Museum.

'Abdu'l-Bahá Himself did not appoint living Hands of the Cause. He appointed four Hands of the Cause posthumously in the course of giving the talks in 1915 that were eventually published as Memorials of the Faithful:

- Muḥammad-Ridá (Mullá Muhammad Ábádí Yazdí)

- Áqá Muḥammad-i-Qá'iní, also called Fadil-i-Qa'ini, but better known as Nabíl-i-Akbar

- Mullá Ṣádiq Khurásání, known as Ismu’lláhu’l-Aṣdaq

- Mírzá ʻAlí-Muhammad, known Varqá

In His Will and Testament, 'Abdu'l-Bahá stated that only the Guardian could elevate a believer to the rank of Hand of the Cause of God:

O friends! The Hands of the Cause of God must be nominated and appointed by the Guardian of the Cause of God. All must be under his shadow and obey his command.

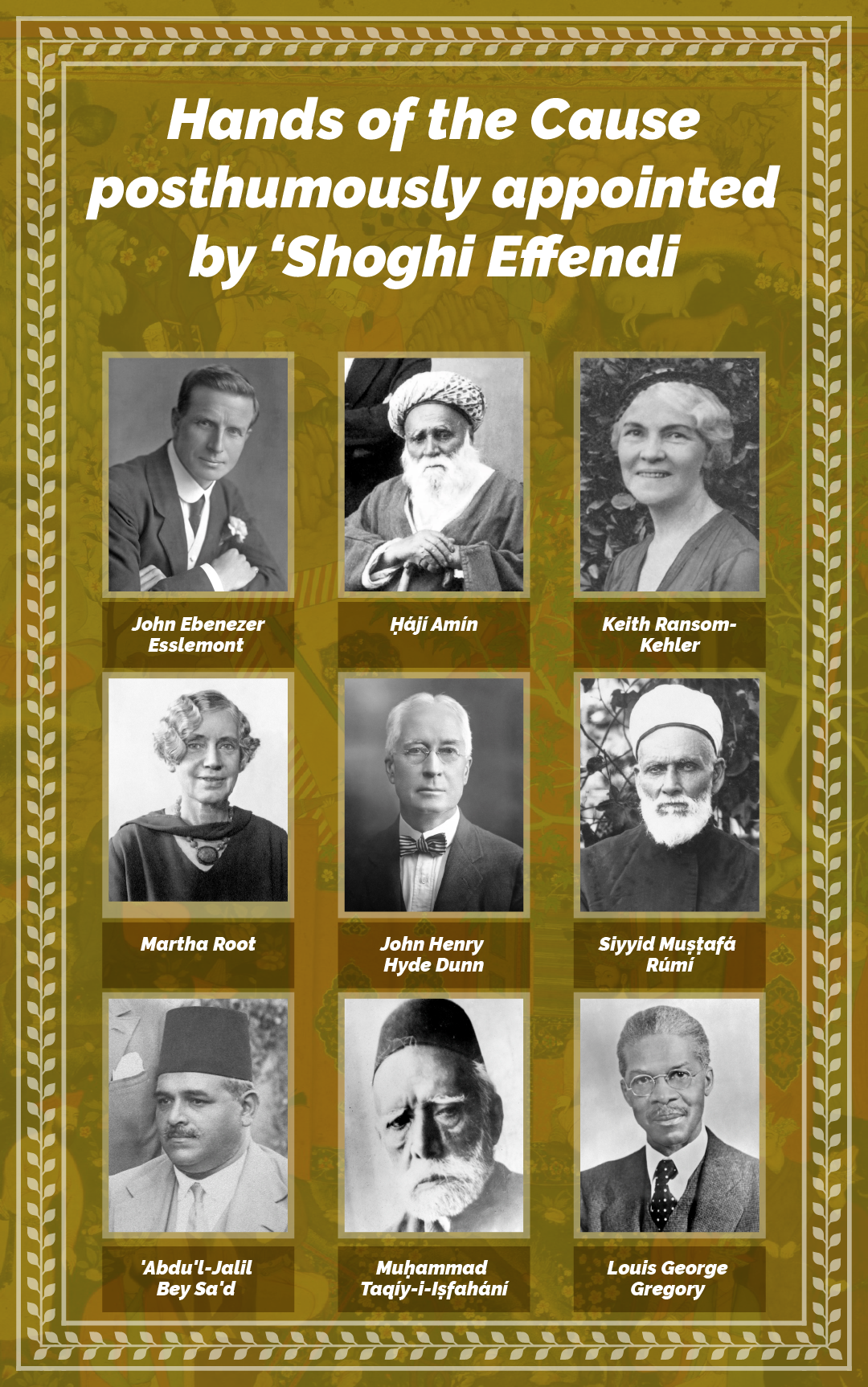

The nine Hands of the Cause whom Shoghi Effendi appointed posthumously during the first 30 years of his ministry, from 1925 to 1951. Background image: Persian miniature from The British Museum.

The station of Hand of the Cause was the highest honor that the Guardian could ever bestow on any Bahá'í, living or dead.

Except for one exception—Amelia Collins, which we looked at on 22 November 1946—for the first three decades of his ministry, Shoghi Effendi followed 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s example and only appointed Hands of the Cause posthumously, either immediately after their death or shortly thereafter:

- John Ebenezer Esslemont (1874–1925) – Posthumously appointed on 30 November 1925

- Ḥájí Amín (1831–1928) – Posthumously appointed in July 1928

- Keith Ransom-Kehler (1876–1933) – Posthumously appointed on 28 October 1933

- Martha Root (1872–1939) – Posthumously appointed on 2 October 1939

- John Henry Hyde Dunn (1855–1941) – Posthumously appointed on 26 April 1952

- Siyyid Muṣṭafá Rúmí (1846–1945) – Posthumously appointed on 14 July 1945

- 'Abdu'l-Jalil Bey Sa'd (d. 1942) – Posthumously appointed on 25 June 1942

- Muhammed Taqíy-i-Iṣfahání (1860–1946) – Posthumously appointed shortly after 13 December 1946

- Roy C. Wilhelm (1875–1951) – Posthumously appointed on 23 December 1951

- Louis George Gregory (1874–1951) – Posthumously appointed on 6 August 1951

William Sutherland Maxwell’s home at 1548 Pine Avenue in Montreal, now the only Bahá'í Shrine in North America. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

All the Hands of the Cause received private messages informing them of their elevation to rank of Hand of the Cause, but because William Sutherland Maxwell was the father of Shoghi Effendi’s wife, his cable is shared here.

Sutherland had left for Montreal after his serious illness, and on 23 December 1951, 24 hours before it was publicly announced to the world, he received a life-changing cable from the Guardian:

Moved convey glad tidings your elevation rank Hand Cause stop appointment officially announced public message addressed all National Assemblies stop may sacred function enable you enrich record services already rendered faith Bahá'u'lláh.

Four days later, on 27 December 1951, Rúḥíyyih Khánum sent this proud cable to her beloved father:

Congratulations Daddy dearest on your appointment by beloved Guardian station Hand Cause all my love Mary

Eleven months after the first thunderclap cable the Guardian sent regarding the International Bahá'í Council, the Bahá'í world saw its worldview regarding its Administrative Order change overnight.

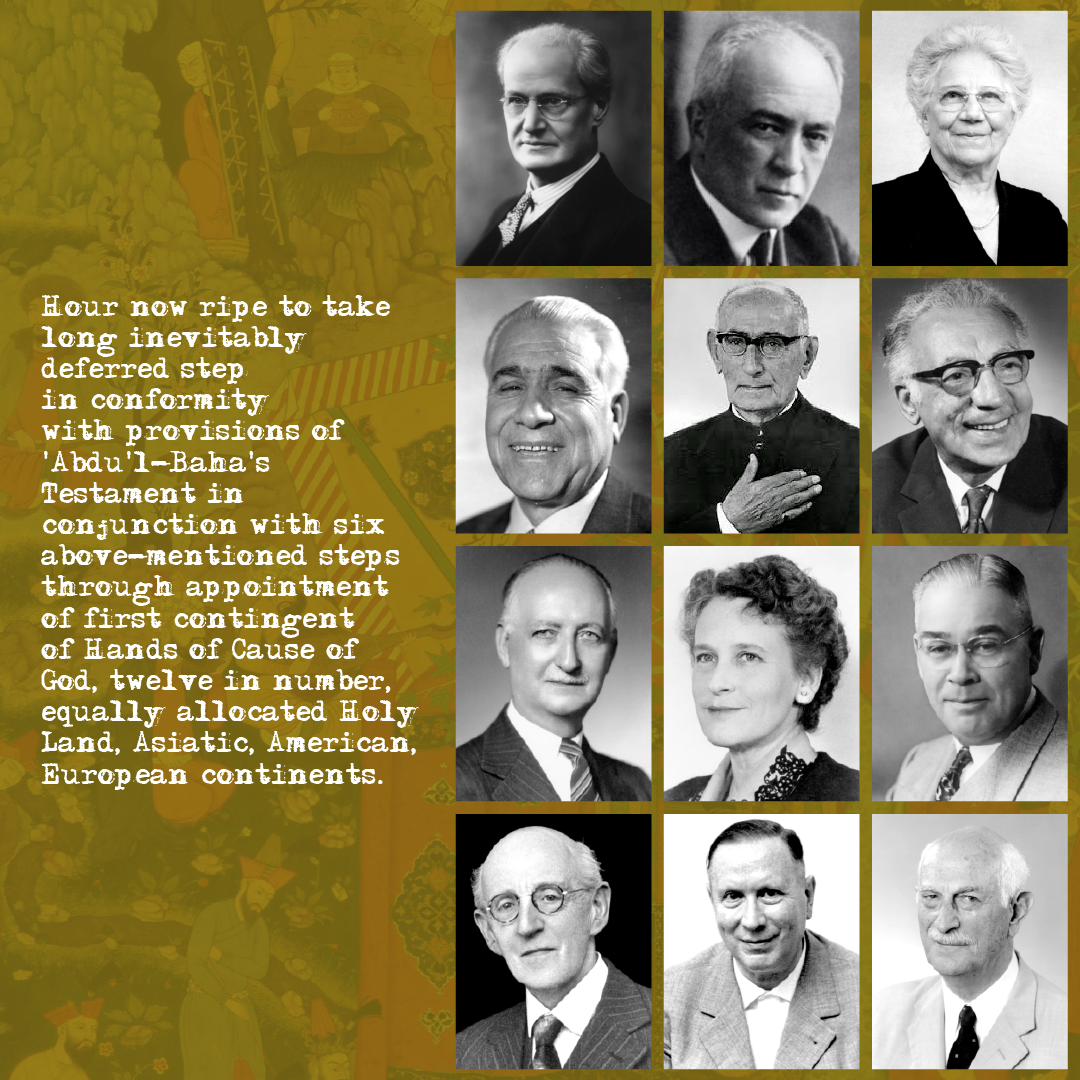

On 24 December 1951, the Guardian suddenly thrust into being the entire appointed arm of the Administrative Order of the Faith, in one fell swoop:

Hour now ripe to take long inevitably deferred step in conformity with provisions of 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s Testament in conjunction with six above-mentioned steps through appointment of first contingent of Hands of Cause of God, twelve in number, equally allocated Holy Land, Asiatic, American, European continents.

But before he did this, in this very long and complex message of 24 December 1951, the Guardian did several things.

Between 1921 and 1946, over the course of the first 25 years of the Formative Age, inaugurated with the ministry of Shoghi Effendi, two of the greatest developments in the history had taken place: One, the local and national institutions of Bahá'u'lláh’s Administrative Order had grown and strengthened, and two, the First Seven Year Plan, at long last, after 20 years, inaugurating the prosecution of 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s Divine Plan.

By late 1951, explained Shoghi Effendi, the Bahá'í world was still in the early years of the second epoch of the formative age.

It was now time for the third “vast majestic fate-laden process,” the crown of Bahá'u'lláh’s embryonic World Order: six nascent institutions at the heart of the Bahá'í World Centre. These institutions, in the order listed by the Guardian himself were:

- First, the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb, in and of itself the institution at the heart of the Bahá'í World Centre;

- Second, the formation of the International Bahá'í Council in Haifa, the forerunner of the Universal House of Justice, itself the legislative organ of Bahá'u'lláh’s divinely-conceived, worldwide Bahá'í Administrative Order.

- Third, the purchase, legal protection, and restoration of further Holy Places in the Holy Land;

- Fourth, the initiation of formal talks with Israeli authorities to protect the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh, and further properties around the Shrine of the Báb;

- Fifth, the design of the future Bahá'í House of Worship on Mount Carmel;

- Sixth, the organization of four intercontinental conferences which would take place during the Holy Year in 1953.

The remainder of the Guardian’s 24 December 1951 message was concerned with explaining the institution of the Hands of the Cause and appointing the Hands themselves.

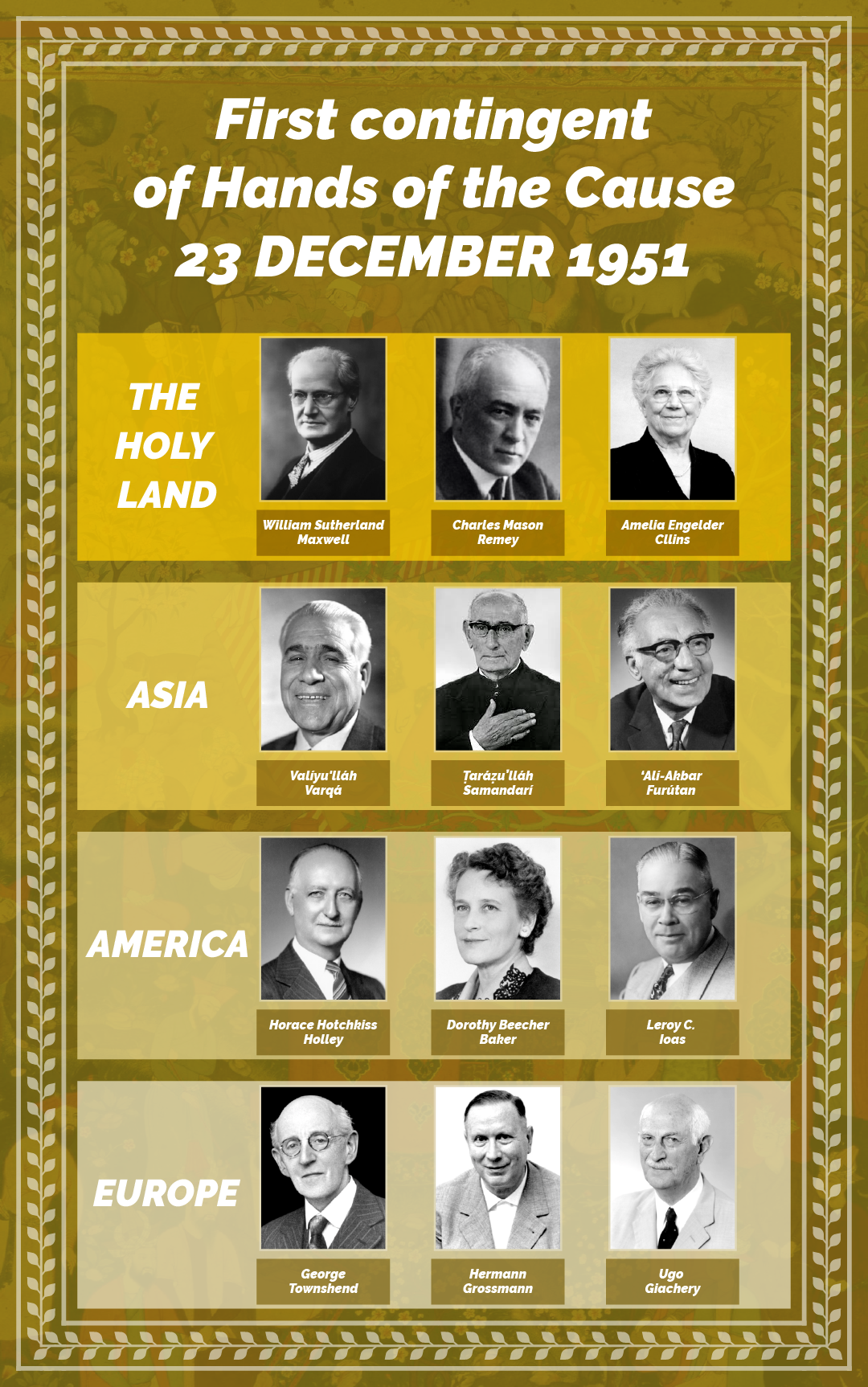

The Guardian appointed three Hands of the Cause for each continent: the Holy Land, Iran, America, and Europe as the nascent appointed arm of Bahá'u'lláh’s Administrative Order, and 12 people’s lives changed forever.

On 23 December they were 12 exceptional Bahá'ís, talented speakers, skilled administrators, peerless teachers of the Cause and relentless defenders of the Faith.

On 24 December, these 10 men and 2 women and became an Institution: The Institution of the Hands of the Cause.

The Guardian explained that, just like the International Bahá'í Archives was a forerunner of the Universal House of Justice—the elected arm of Bahá'u'lláh’s Administrative Order—the Institution of the Hands of the Cause was a forerunner for the appointed branch—which we know today as the International Teaching Centre.

The Guardian did three things when he appointed the Hands of the Cause: He listed their names and continent assignments, he advised the 9 Hands of the Cause outside the Holy Land to not resign from their current positions, and lastly, he encouraged all the Hands of the Cause to attend as many of the upcoming intercontinental conferences during the Holy Year.

Nominated Hands comprise, Holy Land, Sutherland Maxwell, Mason Remey, Amelia Collins, President, Vice-President, International Bahá'í Council; cradle Faith, Valíyu'lláh Varqá, Ṭaráẓu'lláh Samandarí, `Alí-Akbar Furútan; American continent, Horace Holley, Dorothy Baker, Leroy Ioas; European continent, George Townshend, Hermann Grossmann, Ugo Giachery.

Nine elevated to rank of Hand in three continents outside Holy Land advised remain present posts and continue discharge vital administrative, teaching duties pending assignment of specific functions as need arises.

Urge all nine attend as my representatives all four forthcoming intercontinental conferences as well as discharge whatever responsibilities incumbent upon them at that time as elected representatives of national Bahá'í communities.

The list below, broken down first by continent, and then by Hand of the Cause follows exactly the order in which Shoghi Effendi lists the newly-appointed Hands in his message above:

THE HOLY LAND

William Sutherland Maxwell (1874–1952)

Charles Mason Remey (1874–1974)

Amelia Engelder Collins (1873–1962)

ASIA

Valíyu'lláh Varqá (1884–1955)

Ṭaráẓu’lláh Samandarí (1874–1968)

ʻAlí-Akbar Furútan (1905–2003)

AMERICA

Horace Hotchkiss Holley (1887–1960)

Dorothy Beecher Baker (1898–1954)

Leroy C. Ioas (1896–1965)

EUROPE

George Townshend (1876–1957)

Hermann Grossmann (1899–1968)

Ugo Giachery (1896–1989)

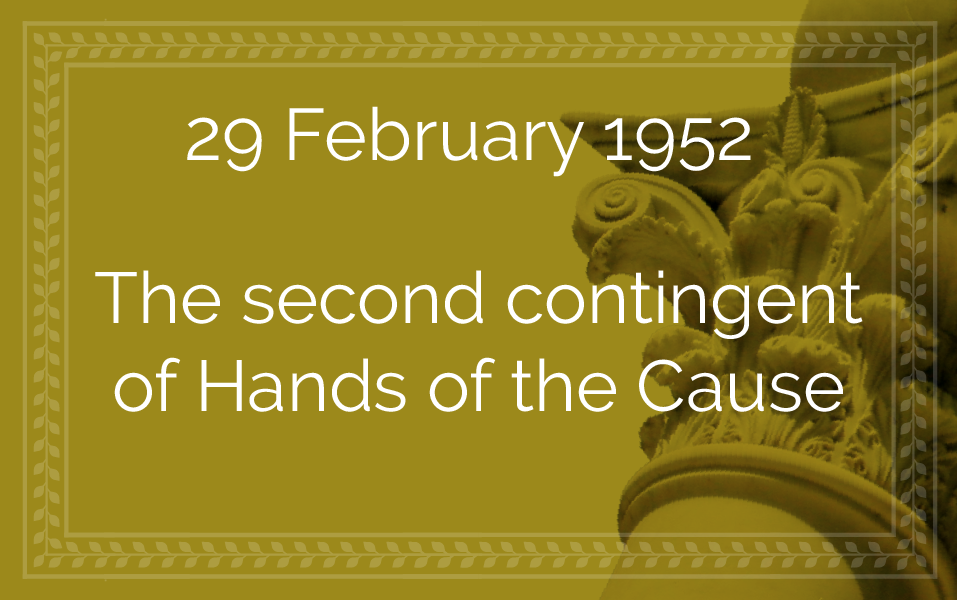

The second contingent of Hands of the Cause appointed by the Guardian on 29 February 1952. Background image: Persian miniature from The British Museum.

Exactly two months after the announcement of the first contingents of Hands of the Cause, the Guardian sent a second announcement on 29 February 1952, elevating seven more Bahá'ís to the rank of Hand of the Cause and bringing the total number of Hands of the Cause worldwide to 19.

The Guardian also announced that the institution of the Hands of the Cause was invested, in conformity with 'Abdu'l-Bahá's Testament, with the two-fold sacred duty of the propagation of the Faith and the preservation of its unity:

Announce friends East and West, through National Assemblies, following nominations raising the number of the present Hands of the Cause of God to nineteen. Dominion Canada and United States, Fred Schopflocher and Corinne True, respectively. Cradle of Faith, Dhikru’lláh Khadem, Shu’á’u’lláh ‘Alá’í. Germany, Africa, Australia, Adelbert Mühlschlegel, Músá Banání, Clara Dunn, respectively.

Members august body invested in conformity with ‘Abdu'l-Bahá's Testament, twofold sacred function, the propagation and preservation of the unity of the Faith of Bahá'u'lláh, and destined to assume individually in the course of time the direction of institutions paralleling those revolving around the Universal House of Justice, the supreme legislative body of the Bahá'í world, are now recruited from all five continents of the globe and representative of the three principal world religions of mankind.

After this announcement, the Guardian informed the Bahá'ís that Hands of the Cause for Canada and Africa had been instructed to take steps to establish national Bahá'í Centers. The list below, broken down first by continent, and then by Hand of the Cause follows exactly the order in which Shoghi Effendi lists the newly-appointed Hands in his message above:

CANADA AND THE UNITED STATES

Fred Schopflocher (1877-1953)

Corinne Knight True (1861-1961)

IRAN

Dhikru'lláh Khádim (1904-1986)

Shu'á'u'lláh ʻAlá’í (1889-1984)

GERMANY

Adelbert Mühlschlegel (1897-1980)

AFRICA

Músá Banání (1886-1971)

AUSTRALIA

Clara Dunn (1869-1960)

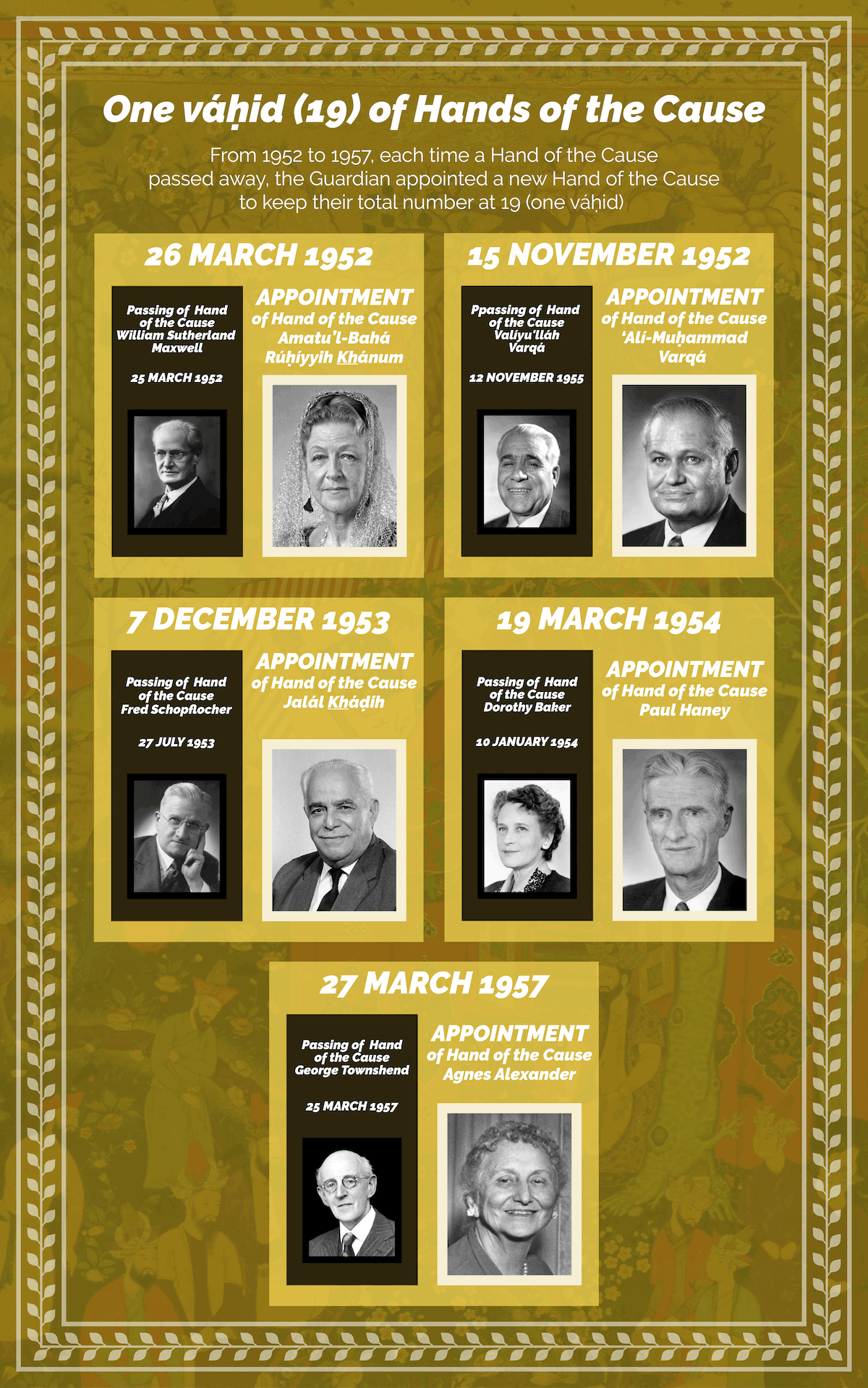

In a two-month period between December 1951 and February 1952, the Guardian appointed 19 Hands of the Cause. In Bahá'í terminology, the number 19 represents one Vaḥíd. One Vaḥíd is considered a unit.

The Guardian, considered this one Vaḥíd (19 Hands of the Cause) as a unit as well.

As far was the 19 living Hands of the Cause between 1952 and 1957, whenever a Hand of the Cause passed away, the Guardian appointed a Hand of the Cause to replace him or her and keep the number of Hands of the Cause to 19.

The Guardian raised two Hands of the Cause to the position which had been occupied by their respective fathers:

- On 26 March 1952, The Guardian appointed Amatu’l-Bahá Rúḥíyyih Khánum as a Hand of the Cause, after the death of her father, Hand of the Cause William Sutherland Maxwell on 25 March 1952.

- On 15 November 1955, ‘Alí-Muḥammad Varqá was appointed to succeed his father, Valíyu'lláh Varqá, who passed away on 12 November 1955. The Guardian also made ‘Alí-Muḥammad Varqá the trustee of the Ḥuqúqu’lláh—as his father had been before him.

Three Hands of the Cause passed away between 1953 and 1957, and the Guardian raised three individuals to the rank of Hand of the Cause after their deaths.

- Following the passing of Fred Schopflocher on 27 July 1953, the Guardian appointed Jalál Kháḍih as Hand of the Cause on 7 December 1953;

- After Dorothy Baker was killed in a plane crash on 10 January 1954, the Guardian made Paul Haney a Hand of the Cause on 19 March 1954;

- Shortly after George Townshend’s death on 25 March 1957, the Guardian appointed Agnes Alexander a Hand of the Cause on 27 March 1957.

The living Hands of the Cause would remain at 19 until 1957, when, with the addition of 8 new Hands of the Cause, their number rose to 27.

Four far-reaching changes in the international institutions of the Bahá'í Faith which the Guardian instituted in a short period of 13 months between January 1951 and March 1952.

Between January 1951 and March 1952, the Guardian set in motion four far-reaching changes at the Bahá'í World Centre in rapid succession:

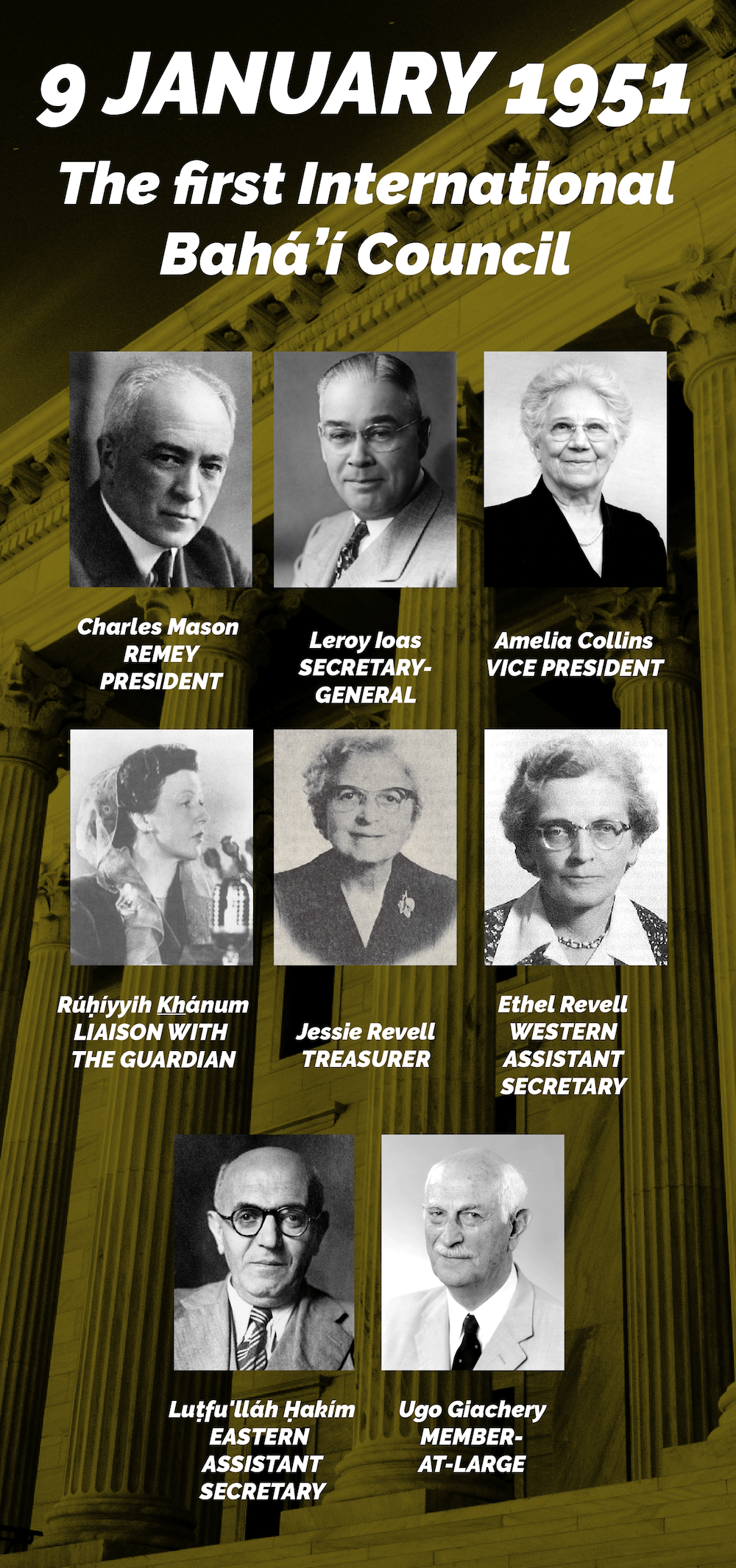

- On 9 January 1951, he announced the formation of the first International Bahá'í Council;

- On 24 December 1951, he appointed the first contingent of 12 Hands of the Cause;

- On 29 February 1952, he appointed the second contingent of 7 Hands of the Cause;

- On 8 March 1952, he enlarged the membership of the International Bahá'í Council.

The Guardian described this evolution in the Administrative Order of the Faith as the erection of "the machinery of its highest institutions", "the supreme Organs of its unfolding Order" which were now, in their "embryonic form" developing around the Holy Shrines.

The Guardian had explained to the Bahá'í world that Bahá'u'lláh’s Administrative Order was guided by the directives and spiritual powers released in the three Charters of the Administrative Order:

- The Tablet of Carmel, revealed by Bahá'u'lláh on Mount Carmel;

- 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s Will and Testament;

- The Tablets of the Divine Plan, revealed by 'Abdu'l-Bahá;

The charter of the Tablet of Carmel embodied the development of the Bahá'í World Centre in the Holy Land, which, as he stated was "geographically, spiritually and administratively, constitutes the heart of the entire planet," "the Holy Land, the Centre and Pivot round which the divinely appointed, fast multiplying institutions of a world-encircling, relentlessly marching Faith revolve," "the Holy Land, the Qiblih of a world community, the heart from which the energizing influences of a vivifying Faith continually stream, and the seat and centre around which the diversified activities of a divinely appointed Administrative Order revolve."

The theater of operations of the Charter of the Tablet of Carmel was the Bahá'í World Centre on Mount Carmel, and the hub around which the Tablet of Carmel was itself centered were these words of Bahá'u'lláh: "ere long will God sail His Ark upon thee and will manifest the people of Baha who have been mentioned in the Book of Names."

The People of Bahá, the Guardian explained, were none other than the members of the Universal House of Justice.

The Charter of the Will and Testament of 'Abdu'l-Bahá was directed the erection of the administrative institutions of Bahá'u'lláh’s Administrative Order: the National Spiritual Assemblies, Local Spiritual Assemblies, the Institution of the Hands of the Cause and the Auxiliary Board Members. The theater of operations of this Charter was the world itself.

The Charter of the Tablets of the Divine Plan was the spiritual conquest of the entire planet, the propagation of the teachings of Bahá'u'lláh in every corner of the globe. Same was with the Will and Testament of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, the Charter of the Tablets of the Divine Plan was the entire world.

The house of 'Abdu'l-Baha in Haifa where Shoghi Effendi lived for half a century and whence, for thirty-six years as Guardian he administered the affairs of the Baha'i Faith. The two rooms where the Guardian lived and worked were added on to the roof; in 1937 three more were added. Originally printed in The Bahá'í World Volume 13, page 150. Source: Bahaimedia.

In the course of a talk in Johannesburg, South Africa in 1978, Leroy Ioas gave a detailed description of what a day in the life of the Guardian was like. These were his days for weeks on end, and they go a long way in explaining why Shoghi Effendi could not rest in Haifa, and why he had to seek solace, once a year, in his beloved Bernese Alps in Switzerland.

Shoghi Effendi usually woke up around 5:30 AM, and after his morning devotions and meditation, he turned his attention to piles and piles of letters, cables and telegrams, sometimes from the day before, along with those which had just arrived that morning.

As he went through his mail, a process that took hours every single day, Shoghi Effendi made notes on each letter regarding how it should be addressed. The Guardian opened every single letter that was addressed to him, he never delegated this task to anyone.

Sometimes Shoghi Effendi gave the letters either to Rúḥíyyih Khánum or to Leroy Ioas to respond, and those that needed to be answered in Persian, he gave to his Persian secretary, Dr. Luṭfu’lláh Ḥakím.

One evening, he told Leroy Ioas:

Today I received 700 pages of minutes and records from different parts of the world, and I had to read them all.

Of course that volume was unusual, but what was a daily occurrence were the hours and hours of reading the Guardian had to do, not just personal letters or letters from National Spiritual Assemblies but minutes of various committees and Assemblies.

Every afternoon, Shoghi Effendi went up to the gardens of the Shrine of the Báb on Mount Carmel, and met the eastern Pilgrims, walking with them in the gardens, speaking with them, having tea with them, and answering their questions. The Guardian spoke to them in Persian or Arabic about the Faith and its worldwide progress, particularly in the east. Then, the Guardian would accompany them to the Shrine of the Báb, and chant the Tablet of Visitation. And after this, he would drive back down the mountain to the House of the Master, and continue his work with his voluminous correspondence, answering the cables that streamed in throughout the day as they came.

Every evening, Shoghi Effendi would have dinner with the western pilgrims in the Western Pilgrim House, and the members of the International Bahá'í Council, and he would speak to them about the progress of the Faith in their countries, speaking to them in English. The Guardian would ask a pilgrim from Canada, for example:

Well, how is the Cause developing in Canada? How is it progressing? How many centers do you have? How many spiritual assemblies do you have? And how many groups do you have?

The pilgrims would invariable answer:

Well, Shoghi Effendi, I don’t know.

And the Guardian would respond:

It didn’t matter which country, Canada, or Swaziland, the Guardian carried the most recent, most up-to-date statistics in his mind at all times. He could rattle off the exact number of Local Spiritual Assemblies, the number of centers were Bahá'ís lived, or the spiritual condition of the Bahá'í community, at any point, for any part of the world.

So he would talk to each and every one about their own country, about the conditions there, about the social conditions, about the problems under which they worked, and give them hope and encouragement and guidance and instructions.

Shoghi Effendi didn’t have secrets, he spoke with the members of the International Bahá'í Council about the affairs of the Council in front of the pilgrims. And the advice the Guardian gave the members of the International Bahá'í Council was infallible. If they couldn’t solve a problem, he would advise to talk to a certain person, and when they did, the issue was immediately resolved.

After dinner, the Guardian would return to his office to do a few more hours of work, sleeping around midnight each night. This was a typical day for the Guardian, from Monday to Sunday, from 5:30 in the morning to 11:30 at night and sometimes even 3:00 AM, continually burdened, constantly under pressure, always snowed under a mountain of hundreds of letters, day after day, week after week, month after month, for a year.

Colorized portrait of 'Abdu'l-Bahá taken in Paris. In October 1911. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

Two of Shoghi Effendi’s most distinctive qualities were his humility and his reverence towards the Central Figures of the Faith. This story illustrates both.

Shoghi Effendi never spoke of himself, and never, ever, made reference to his ministry or his Guardianship. He would never say in the time of the Guardianship, but rather in the days after 'Abdu'l-Bahá. When he wrote God Passes By, he never mentioned himself, although the part of God Passes By on the Formative Age of the Faith is equivalent to the time of his Guardianship.

One day, Leroy Ioas was speaking to Shoghi Effendi and made a grave mistake. He mentioned Shoghi Effendi’s name in the same sentence and in the same vein almost as 'Abdu'l-Bahá, and the Guardian stopped him in his tracks, immediately saying:

Don’t ever do that. Don’t ever mention my name in the same breath as you mention the Master. The Master was like the ocean; I am like a drop. The Master was like the sun; and I am like an atom. So don’t ever, ever mention my name in the same theme or same trend of thought as that of the Master. There is a vast gulf between Abdu’l-Bahá and all the rest of creation, and between the Guardian.

June 1843 Reproduction of Plan of Environs of 'Akká by Lieutenant Symonds & Skyring, showing Bahjí at the top center of the map. Source: Archives of Israel.

The Guardian, from the very beginning of his ministry, had always considered protecting and beautifying the Bahá'í Holy Shrines as one of his sacred tasks, but his most preoccupying issue was that the Bahá'í Faith did not own any of the land around Bahjí.

The piece of land the Guardian desperately needed was a 40-acre plot of land owned by the Baydún family, Muslims with close ties to the Covenant-breakers. Their hatred was so entrenched that the Baydún family would not even entertain the possibility of selling land to the Guardian and the Bahá'í Faith. Over time, the Baydúns even dug ditches around the Shrine and planted trees blocking its view.

In the 1880s, Bahá'u'lláh, then still a Prisoner in 'Akká, had directed 'Abdu'l-Bahá to purchase properties near the Sea of Galilee and the Jordan River, including one 35-acre piece of land registered to the name of a descendent of Mírzá Músá’s, Dhikru’lláh, and which was now in the hands of his eldest son, a faithful Bahá'í.

After 1948 and Israel’s independence, the Baydún family was among the 700,000 Arabs who fled the new country, and the Bahjí property they left behind reverted to the state of Israel.

By 1952, the Dhikru’lláh property had become immensely valuable.

It was strategically located between Syria and the West Bank, and the State of Israel was desperate to purchase these 35 acres. Initially, Shoghi Effendi refused to sell the property because 'Abdu'l-Bahá had asked the Bahá'ís to keep the land, but someone suggested exchanging this valuable property for the abandoned Baydún land around the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh.

A vintage postcard of Kampala and Nakasero, Uganda. Source: Northwestern Libraries and Digital Collection.

18 years after their first pilgrimage and one year after settling in Kampala, Uganda, Músá and Samíhíh Banání returned for a second pilgrimage in February 1952. Before leaving Kampala, they had agreed with the Bahá'í pioneers that they would hold a special meeting with African seekers while the Banánís were in Haifa, a meeting that would coincide with the appointed time during which Shoghi Effendi visited the Shrines.

The teaching work in Africa was growing exponentially, and Shoghi Effendi was so thrilled with their work and the work of Violette and ‘Alí Nakhjávání, that their reunion with their Guardian was an especially joyful one, and during each day of their pilgrimage, the Guardian gave the Banánís detailed instructions for the development and growth of the Faith in Africa.

At the same time the meeting in Kampala was being held with the African seekers, Shoghi Effendi and Músá Banání prayed together at the Shrines for the progress of the Faith. The next morning was when Enoch Olinga declared his belief in Bahá'u'lláh. By 21 April 1952, there were enough Bahá'ís in Kampala to elect the first Local Spiritual Assembly, and six months later, by October 1952, there were 100 Bahá'ís in Uganda.

Hand of the Cause Músá Banání (seated third from left in the second row) at a deepening school in Kabras, Kenya in 1960. Originally published in Baha'i News Issue 335, page 5. Source: Bahaimedia.

On 29 February 1952, the last day of his pilgrimage, the Guardian informed Músá Banání that he had been elevated to the rank of Hand of the Cause and called him “the spiritual conqueror of Africa” in the cable he had sent the Bahá'í world.

Músá Banání, who was illiterate, protested with his characteristic humility:

I am not worthy. I cannot read or write. My tongue is not eloquent. Give this mantle to ‘Alí Nakhjávání who is doing the lion's share of teaching in Africa.

Shoghi Effendi replied:

It is your arising that has conquered the continent ‘Alí’s turn will come.

Colonel Jalál Kháḍih. Source: Bahaimedia.

Jalál Kháḍih was born into a Bahá'í family in Ṭihrán on 24 February 1897—the same year as the Guardian—and lost his father at the age of 7 because of complications from torture and persecution he had endured in his hometown of Sidih, near Iṣfahán. Jalál Kháḍih completed his compulsory military service in the Persian Army and studied veterinary science at Military Academy.

By the time Jalál Kháḍih was 19, had earned the rank of Lieutenant and married Jamálíyyih Kashání. Together, Jalál and Jamálíyyih had five children, two sons and three daughters, and the family traveled all around Iran for Jalál Kháḍih’s military career, as he was stationed in many cities like Qazvín, Hamadán, Kirmánsháh, Sanandaj, Khurramabád, Burujird, and Ahvaz.

When he retired at the age of 46 in 1943, Jalál Kháḍih was a Colonel, and the next year, in 1944, he was elected on the National Spiritual Assembly of Iran. And then, Jalál Kháḍih went on pilgrimage and met the Guardian. His life would change forever.

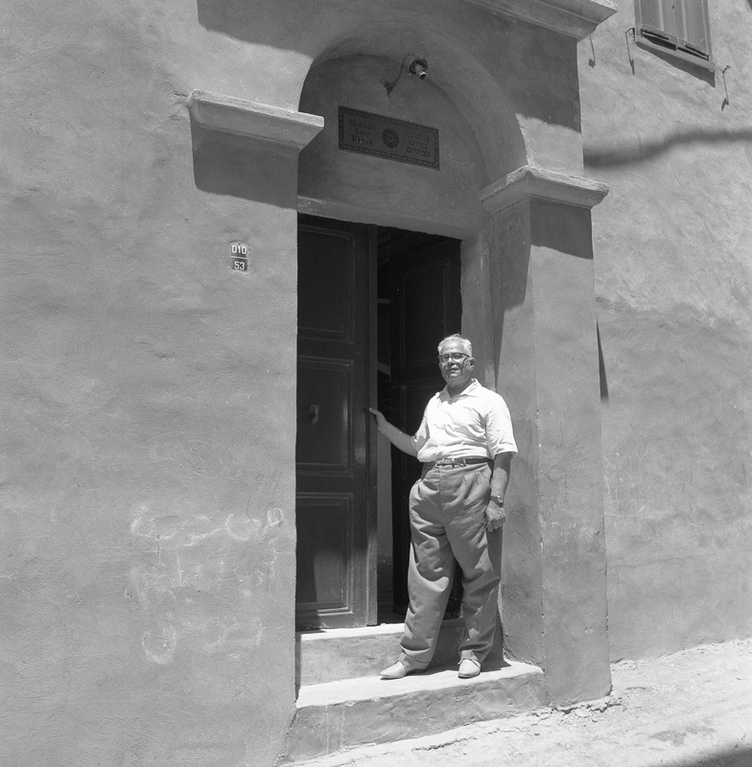

Jalál Kháḍih at the House of ‘Abbúd. Source: Bahaimedia.

The first time Jalál Kháḍih met Shoghi Effendi was during his pilgrimage in March 1952. Jalál Kháḍih, often described himself as a “new creation,” after meeting the Guardian. Entering into Shoghi Effendi’s presence and learning from him for the duration of his pilgrimage was a watershed event in his life: there was a before-the-Guardian Jalál Kháḍih, and an after-the-Guardian Jalál Kháḍih. The following story is one Hand of the Cause Jalál Kháḍih himself used to tell at summer schools.

When Jalál Kháḍih was on pilgrimage, the Guardian himself took the pilgrims to the Shrine of the Báb. The Guardian went forward and placed his head on the threshold, and after a while, he stood up and started walking backwards out of the Shrine. Jalál Kháḍih did not know the protocol for this situation: should he face the Guardian of the Cause of God, walking backwards out of the Shrine or should he face the threshold of the Shrine, and, as one person remembers him saying it, he “half-halfed it,” fumbling and turning somewhere in between the Guardian and the threshold of the Shrine.

When Jalál Kháḍih finally came out of the Shrine, the Guardian was standing there, looked at him and told him:

All of the messengers of God, all the prophets of old are circumambulating this sacred spot.

Jalál Kháḍih realized that he should have faced the threshold. After a short while, the Guardian turned and started walking, the pilgrims following behind. As Shoghi Effendi was walking, Jalál Kháḍih began to think

If all the of the messengers of God, the prophets of old are circumambulating here, then what is happening in Bahjí?

Jalál Kháḍih always said that the very moment that thought entered his head, the Guardian turned around, looked at him straight in the eye and said:

And all of the messengers of God, all the prophets of old, and the soul of the Báb, in turn, are circumambulating the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh.

Before leaving the Guardian, Jalál Kháḍih secured his approval regarding his plan to resign from the Local Spiritual Assembly of Ṭihrán after having served on it for three years, and travel Iran full time to teach the Faith.

This is the first Baha’i institution in Italy, the Local Spiritual Assembly of Rome, in 1948. Hand of the Cause of God Ugo Giachery is standing on the far right and was a member of the Local Spiritual Assembly. Source: Bahá'í World News Service.

As the Guardian’s legal trial against the Covenant-breakers brought against him after his destruction of a worthless dilapidated building approached, Shoghi Effendi called Ugo Giachery on pilgrimage to assist him during the time of the trial. Unfortunately for Ugo Giachery, this meant that he would be an eyewitness to the shameful behavior of the Covenant-breakers.

Ugo Giachery met Shoghi Effendi for the first time when he arrived for his first pilgrimage and consultation on 4 March 1952, a little over two months after having been appointed a Hand of the Cause. The custom was to let the newly-arrived pilgrim precede everyone else into the dining room of the western Pilgrim House, an oval-shaped room, and Ugo Giachery saw the Guardian for the first time.

Shoghi Effendi was sitting at the far end of the table—never the head of the table, which he reserved for guests he wished to honor—and he was wearing a dark steel-grey coat and a. a black fez. He lifted his head and met Ugo Giachery’s eyes with a luminous, penetrating gaze, rose to greet his Hand of the Cause with a broad smile, illuminating his face. At dinner, Shoghi Effendi told everyone at the table:

We are very glad to have such a Bahá'í friend, to whom the whole world is indebted.

Then, addressing Ugo Giachery, he added:

The service you have rendered is not sufficiently appreciated today, but it will be fully appreciated in the future…You see, you worked for so long all alone; and no one appreciates this more than I, myself. When you are alone, you have such a big weight to carry. Single-handed, you have rendered an historic service to the Cause…This evening when I went to the Shrine, I remembered you, and I have come to the decision that we shall have a “Giachery” door for the Shrine—one of the doors.

The Guardian gave a little background regarding how 'Abdu'l-Bahá had purchased land for the Shrine of the Báb, and how much He had suffered building it, and the difficulties Jamál Pashá had caused, then, he turned to Ugo Giachery again and said:

You are one of the three—Sutherland [William Sutherland Maxwell], myself and you. Sutherland rendered services in connection with the Shrine which are most meritorious - more meritorious than anything I have done - more meritorious than anything Ugo has done.

Jasmine flowers, Shoghi Effendi’s favorite scent. Photo by Dagmara Dombrovska on Unsplash. Lilies of the Valley, Shoghi Effendi’s favorite flower. Photo by Océane George on Unsplash.

One night in early spring—we do not know the year—Ugo Giachery had the privilege of staying one night in the Mansion of Bahjí at the same time as Shoghi Effendi was there. In the Mansion of Bahjí there is a small garden, bordered by a stone wall which is so beautiful it is like a small corner of paradise here on earth.

It had sorely been neglected during the 40 years the Covenant-breakers had sullied Bahjí, but Shoghi Effendi had revived the garden and planted trees, shrubs, and flowers all around, and when you entered it, you could smell loveliness coming from all directions: the exquisite scent of orange blossoms, the earthy smell of the geraniums, sweet roses, and several varieties of jasmine.

When Ugo Giachery entered the garden, he was almost overtaken by the fragrances, which he described as a “heavenly nectar.” Before leaving Bahjí that day, Ugo Giachery gathered some jasmine blossoms and put them in a small vase which he placed in front of the Guardian’s seat at the dinner table.

The Guardian didn’t speak. He was not only pleased but deeply moved, and searched Ugo Giachery’s eyes with his luminous gaze, then smiled, raised the jasmine bouquet to his nose and inhaled the heavenly scent with visible delight.

Ugo Giachery later learned that jasmine was the Guardian’s favorite scent. Interestingly, lilies of the valley, those beautiful, tiny, bright-white bell-shaped fragrant wildflowers, were Shoghi Effendi’s favorite flower.

No drawings were found of Shoghi Effendi’s planned superstructure for the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh, but his descriptions of a monumental, exquisite monument brought to mind another monumental timeless structure: The Taj Mahal of Agra, India. Photo by Shamees Cm on Unsplash.

When Ugo Giachery was visiting the room used by 'Abdu'l-Bahá at the Pilgrim house in Bahjí, he was shown a large number of architectural drawings and other papers, contained in a wooden coffer which had been untouched for 50 years.

Many of the papers and drawings were written and illustrated in Italian, and they concerned the project of a monumental final Shrine for Bahá'u'lláh, the work of an Italian engineer and architect, Henry Edward Plantagenet— a descendant of the English Royal Family which ruled from 1154 to 1485. Henry Edward Plantagenet was born and lived in Florence, Italy, and he had been commissioned by the Ottoman Government to build the Syrian railroad, and so had lived in Syria for a number of years.

The plans indicated that a member of Bahá'u'lláh’s family had sked him to draw the plans for the superstructure of the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh, and he had obviously been inspired by Bábí concepts because the monument was a large, five-pointed star, the symbol of the Báb. This was not 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s plan, the Master had a different concept in mind for the final Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh.

At dinner that night, Ugo Giachery spoke of the Italian designs with Shoghi Effendi, and praised the facades of the current Shrine, very happy to hear from the Guardian that he, too, had no intention of altering the natural, simple beauty of the current Shrine, but explaining to Ugo Giachery what 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s vision was:

The building as fortified by Abdu'l-Bahá will not be touched; it will remain as the core of the new structure to surround the whole area, an inestimable gem representing the focal point of adoration for all the present and future followers of Bahá'u'lláh.

Shoghi Effendi called the superstructure of the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh a mere ornamentation, saying it was “only an embellishment,” as the great Shrine, “of untold magnificence, would be erected in future decades.”

Shoghi Effendi was considering different ways of making 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s vision a reality, including surrounding the original Shrine with a colonnade of 95 monolithic Doric columns of Carrara marble surmounted by exquisite Doric capitals. He envisioned the columns arrayed in pairs, one on each side of a walkable pathway on a platform of Carrara marble, accessible by five steps, and he described his vision of the colonnade as “arms stretching ready to embrace.”

For several nights, Shoghi Effendi spoke about the superstructure to the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh. He asked Ugo Giachery about various types of statuary marble—of course the Guardian’s preference was the best of the best, the king of all marbles, the glowing white Carrara marble used since Roman times. Shoghi Effendi also asked Ugo Giachery about the logistics for producing immense monolithic columns out of marble, and questioned Ugo Giachery—who had phenomenal knowledge—about the various types of historic triumphal commemorative or honorific monuments.

The Guardian explained that the 95 columns should be 6 meters tall, each supporting a carved capital, the total weight of which would be close to a ton, and with the height of the column base, each column would soar 7 meters into the air, not including the five steps, which would add to the height. In the Guardian’s mind, it was a formidable complex of brilliant majesty, that would glorify and enshrine the current precious Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh.

It was important for the Guardian that Ugo Giachery to secure an architectural plan based on his detailed descriptions as soon as possible.

Shoghi Effendi describes his vision for the gardens at Bahjí to Ugo Giachery on 4 March 1952. A photograph of the completed gardens transformed into a drawing using the website Picsart. Image inspiration: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

When Ugo Giachery was on pilgrimage between March and July 1952, the Guardian had spoken to him at length regarding his plans to embellish the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh and beautify the land around it, the Ḥaram-i-Aqdas. Shoghi Effendi commissioned Ugo Giachery to secure drawings and estimates of these plans as soon as he was back in Italy. On their first dinner, the first evening of Ugo Giachery’s pilgrimage, Shoghi Effendi turned to him and said:

When the dome [of the Báb's Shrine] is finished, your work is not finished. We cannot hope to build the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh now - that is impossible - but we can do something intermediate. The Master added a wall around to reinforce the original room. We cannot leave it for an indefinite time in this manner.

Then, turning to Larry Hautz—an American pilgrim who would stay to assist Leroy Ioas for 90 days with purchasing land for the Guardian— he added:

If you succeed in getting this land around the Shrine - it is very extensive - it will be a great blow to the Covenant-breakers. You will not only have dealt them a terrible blow, but you will have paved the way for the construction of what is going to be the intermediate stage between the present structure of the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh and the final building, which will be on a scale far greater than the Shrine of the Báb.

Towards the end of the evening, the Guardian returned to the subject of land, and spoke of extending Bahjí:

We expect to get fifty acres at Bahjí [permitting] avenues one hundred metres long, all smooth paths converging; we shall keep on building it, we shall build around it: a semicircular, double colonnade with columns all of marble. Preferably ninety-five in number, white, with ornaments, flower-beds, lawns and hedges.

“Apathy.” Background image by Danielle-Claude Bélanger on Unsplash.

Shoghi Effendi was at times saddened by the actions of individual believers, and suffered deeply from what he perceived to be the inertia or the apathy that came over Bahá'ís at times. The Guardian could only do so much, and pilgrims often remembered the Guardian saying what he told Ugo Giachery one night:

I have told them to do this; now it is no longer in my power, it is in their hands, and they must accomplish it.

One night at dinner, Shoghi Effendi, speaking about world events at a very tumultuous time in history, the post-War period, the newly-created State of Israel—and he said:

If I should be influenced by the chaotic condition which exists in the world, I would remain passive and accomplish nothing.

“A thousand scorpions.” Scorpion vintage black and white drawing from Freepik.

The Guardian spoke to Ugo Giachery alone for many hours one evening during his pilgrimage between 4 March and July 1952. The Covenant-breakers—the old guard from the time of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, and the new Covenant-breakers from the ministry of the Guardian—were active, and Shoghi Effendi related to Ugo Giachery the suffering and anguish of 'Abdu'l-Bahá caused by the provocations, the evil machinations, the defiant and open hostility of the Covenant-breakers.

At the time, the two generations of Covenant-breakers were emboldened by the newly-created State of Israel and were trying to devise ways in which to take from the Guardian all the Bahá'í properties in the Holy Land through contesting the Will and Testament of 'Abdu'l-Bahá.

What they intended to accomplish was to drag the Guardian to court and publicly humiliate him. The entire affair lasted three months and ended with the Guardian’s victory, of course, but his suffering was unimaginable and very difficult for Ugo Giachery to describe. The sacredness of the Institution of the Guardianship had been attacked for the purpose of creating confusion among the ranks of the believers, and the greatest suffering of the Guardian came from the insult to the Institution of the Guardianship, and it made him so physically ill, he told Ugo Giachery it was as if “a thousand scorpions had bitten him.”

During the most crucial days of this sorrowful experience, the Guardian’s indignation was at its height, and he reviewed for Ugo Giachery the tragic history of the Faith from its inception in the Heroic Age, how Bahá'u'lláh had been betrayed by Mírzá Yaḥyá—the Arch-Breaker of the Covenant of the Báb—how Mírzá Muḥammad-'Alí—the Arch-breaker of the Covenant of Bahá'u'lláh—had inflicted unmentionable sufferings on 'Abdu'l-Bahá, and the Covenant-breaking in his own ministry, by 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s immediate family, all their acts of treachery and disobedience.

The Guardian was filled with anxiety and visibly grieved and told Ugo Giachery repeatedly that evening:

You must know these things, I want you to know these things.

Gradually, Ugo Giachery realized something important: the Guardian was in mortal danger and no Bahá'í outside of the room he was in—the closest Bahá'ís to Shoghi Effendi in his service—knew about it:

I became conscious that the Divine Covenant was assailed with vehemence by ruthless, satanic people, and that while the mass of the believers throughout the world were unaware of this grave danger, he, Shoghi Effendi, single and alone, was its defender, protected only by the armour and shield of his faith in God and His Covenant. The image passed rapidly through my mind of this new David battling single-handed against a ferocious, deadly monster, with all the terrors of the wilderness around him. He mentioned to me by name, one by one, the unfaithful members of his immediate family, their disobedience and obstinacy.

The Guardian also told Ugo Giachery about Covenant-breakers begging for his forgiveness with pathetic excuses, and said:

I am only the Guardian of the Cause of God and I must show justice. God only can show them mercy, if not in this world, in the next.

The Guardian paused, looked at Ugo Giachery silently for a while, and added:

But if they repent the Guardian would know their sincerity and pardon them.

In the course of this very lengthy conversation, Ugo Giachery had seen shadows of sorrow and dismay pass over the Guardian’s luminous face, like dark, heavy storm clouds pass through the sky. The entire time the Guardian was speaking, Ugo Giachery could feel the inner agony of the Guardian’s soul and the sufferings of his body, and that realization caused a huge surge of boundless love for the Guardian to swell up inside Ugo Giachery.

What would I have given to restore his happiness and tranquility! How much I loved this Defender of the Covenant, this Sign of God on earth, the inspirer of every noble thought among the children of men! I had to control myself not to take him in my arms, to shield him from any further suffering, to assure him that for every Covenant-breaker there were thousands and thousands of believers who, like me, were ready to shed their blood if that were demanded!

On 8 March 1952, a year after its inception, the Guardian enlarged the membership of the International Bahá'í Council, adding three new members, all Hands of the Cause: Ugo Giachery, Leroy Ioas, and Luṭfu’lláh Ḥakím. The new International Bahá'í Council was composed of: Hand of the Cause Mason Remey—President; Hand of the Cause Leroy Ioas—Secretary-General; Hand of the Cause Amelia Collins—Vice-President; Amatul'Bahá Rúḥíyyih Khánum—Liaison between the Guardian and the Council; Jessie Revell, Treasurer; Ethel Revell—Western Assistant Secretary; Luṭfu’lláh Ḥakím—Eastern Assistant Secretary and Hand of the Cause Ugo Giachery—Member-at-large. The background of the graphic is a stunning photograph by Chaud Mauger of the columns of the Universal House of Justice, which the International Bahá’í Council was meant to foreshadow. Source: Chad Mauger’s Flickr page, © Chad Mauger, used with permission.

Fourteen months after he announced the formation of the first International Bahá'í Council, the Guardian announced its enlargement on 8 March 1952 in a long cable.

The new membership of the International Bahá'í Council included:

- Amatu’l-Bahá Rúḥíyyih Khánum—Liaison between the Guardian and the Council;

- Hand of the Cause Mason Remey—President;

- Hand of the Cause Amelia Collins—Vice-President;

- Hand of the Cause Ugo Giachery—Member-at-large;

- Hand of the Cause Leroy Ioas—Secretary-General;

- Jessie Revell, Treasurer;

- Ethel Revell—western Assistant Secretary;

- Luṭfu’lláh Ḥakím—eastern Assistant Secretary.

The International Bahá'í Council was finally functioning according to the Guardian’s vision, three decades earlier.

The members of the International Bahá'í Council received their instructions from the Guardian individually, in the informal atmosphere of dinners at the Pilgrim House.

All the members of the Council were busy with tasks the Guardian allotted to them, and the functioning of the International Bahá'í Council as a whole successfully conveyed the image that the Guardian had so long yearned for: that of an international body managing the affairs of the Bahá'í Faith in Israel in the minds of the authorities.

The public and the Bahá'í world, through this International Bahá'í Council appointed and guided in its every steps by Shoghi Effendi, began to see the image of an international governing body for the Bahá'í Faith, that, in the fullness of time, would evolve into the Universal House of Justice.

On 4 May 1955 the Guardian announced that he had raised the number of members of the International Bahá'í Council to nine through the appointment of Sylvia Ioas, wife of Hand of the Cause Leroy Ioas.

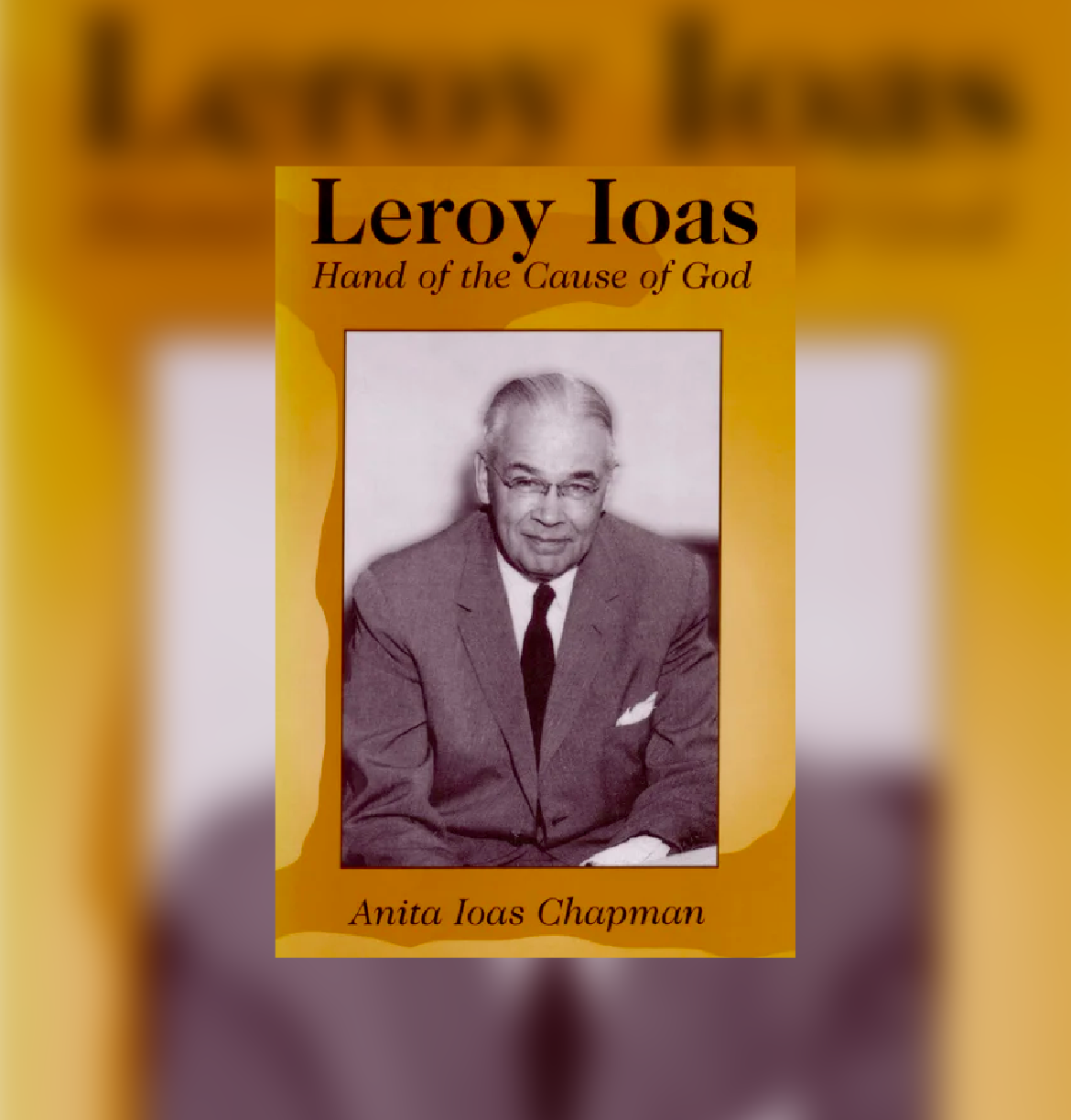

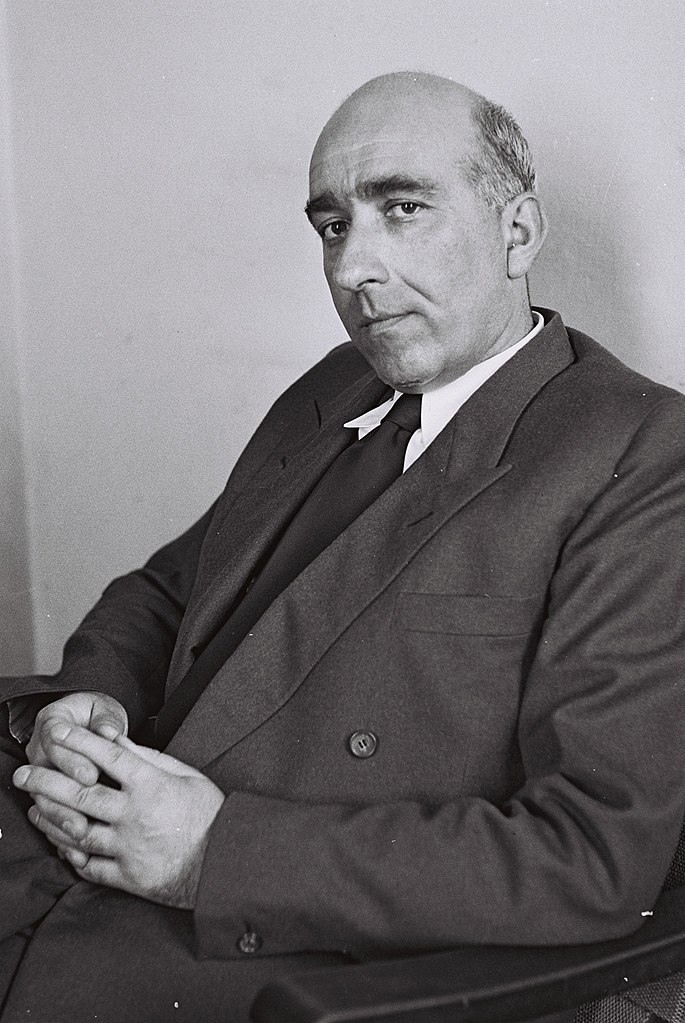

Leroy Ioas: Hand of the Cause of God is the perfect complement to Ugo Giachery’s Shoghi Effendi: Recollections, because in essence, they address the overlapping 5 years during which Ugo Giachery and Leroy Ioas was his Hercules both served the Guardian, assisting him in the developments of the International Bahá'í Endowments in the Holy Land.

Ugo Giachery began serving the Guardian five years Leroy Ioas but both Hands of the Cause were Shoghi Effendi’s rock, two men on which Shoghi Effendi could not only count on at any moment and for any service, but also trust blindly that the work they did would be beyond perfect. Their biographies are complementary because Ugo Giachery served in Italy and Leroy Ioas was at the Guardian’s side in Haifa.

Anita Ioas Chapman’s biography of her father is a scintillating work filled with so many intimate snapshots of the Guardian, so many insights into his work—Leroy Ioas was not only Secretary-General of the Bahá'í International Community, but he was also Shoghi Effendi’s secretary and both of his roles offer rare glimpses into a relatively unknown aspect of Shoghi Effendi’s life.

Leroy Ioas: Hand of the Cause of God is one of the best-written, most eloquent Bahá'í biographies you will find. Reading it is not only a tremendous pleasure, but an honor.

Leroy C. Ioas (1896-1965). Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

Leroy Ioas was one of the most eminent American Bahá'ís in the Formative Age of the Bahá'í Faith, the son of German immigrants to the United States. When he was 16 years old, 'Abdu'l-Bahá visited the United States and Canada, and Leroy Ioas met Him in Chicago, and he was present when 'Abdu'l-Bahá laid the cornerstone for the House of Worship in Wilmette.

Being in the presence of 'Abdu'l-Bahá was a transformative experience for Leroy Ioas, one that shaped his life, and he would later say that what photographs of 'Abdu'l-Bahá did not show was “the vibrant spirit that was coursing through Him at all times.” As a teenager, Leroy Ioas was enveloped in the powerful presence of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, and that presence stayed with him throughout his life, which he dedicated to service to the Bahá'í Faith.

Leroy Ioas married Sylvia Kuhlman in 1919, was elected to the National Spiritual Assembly of the United States and Canada in 1932, and had a brilliant 40-year career with the southern Pacific Lines, rising from the lowest ranks of the company to the Passenger Traffic Manager for the eastern United States.

The Guardian appointed Leroy Ioas as a Hand of the Cause in the first contingent on 24 December 1951, and on 15 February 1952, the Guardian’s secretary invited Leroy Ioas to move to Haifa and act as the Secretary-General of the International Bahá'í Council, adding:

If you will accept to do this it would be rendering [the Guardian] and the Faith an invaluable service.

Leroy Ioas had never left the United States, and he was about to begin the greatest and most exciting adventure of his life: six years as the right-hand man of the Guardian, who referred to Leroy Ioas affectionately as “my Hercules.”

Leroy Ioas arrived in Haifa at 2:00 PM on 10 March 1952, just in time to meet Dr. Giachery, who had just arrived from Italy a couple of weeks earlier and met the Guardian for the first time. Together, they were about to embark on the last, most exciting phase of the construction work: The building of the drum and the dome of the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb.

Leroy Ioas and Ugo Giachery in Jerusalem. Two Hands of the Cause closely associated with the Guardian between 1947 and 1957, and who both left profoundly moving pen portraits of Shoghi Effendi. Source: Leroy Ioas: Hand of the Cause of God by Anita Ioas Chapman, between pages 274 and 275.

Leroy Ioas was an American, and he had never seen the Guardian before he arrived in Haifa on 10 March 1952. Being American, he expected such a towering figure as the Ugo Giachery to be very tall and imposing with big shoulders, but he was shocked to discover that Shoghi Effendi was in fact small in stature, refined, and delicate.

All of his features were exquisitely refined: his nose, his eyes, his delicate small hands. And Leroy Ioas realized that the majesty and greatness of the Guardian, his imposing stature for Bahá'ís across oceans was not his physical size, towering over every person in the room, but the power of the Spirit that flowed through him. The Guardian was a channel used by God, he did not need to be 2 meters high. He needed to be the Guardian.

When the Guardian spoke about the power of the Cause, it seemed to Leroy Ioas as if the building shook from the power of his words, and in the five years that he served him, Leroy Ioas never ceased to marvel at the way God used the Guardian to do his work on this earth.

In fact, Shoghi Effendi was smaller than 'Abdu'l-Bahá, closer in his physical stature to Bahá'u'lláh. All three of them, Bahá'u'lláh, 'Abdu'l-Bahá, and Shoghi Effendi, were small in size. Shoghi Effendi some of the same facial features as 'Abdu'l-Bahá, he had the hands of Bahá'u'lláh, and he had the eyes of the Báb.

Although the Guardian was always very serious, he had a twinkle in his eye and a delightful sense of humor.

The Regional Spiritual Assembly for Switzerland and Italy for the year 1955-1956. Originally published in Baha'i News Issue 294, page 11. Source: Bahaimedia.

The Guardian appointed Ugo Giachery member-at-large of the International Bahá'í Council, and told him he would name the last remaining door of the Shrine of the Báb after him. Then, the Guardian told Ugo:

Your full station is not yet revealed, but I shall see that it is.

Ugo Giachery, in his memoirs, described what must have been the most profound experience of his life:

[The Guardian’s] eyes poured love upon me, and his tender attentions have rent my heart.

There were two more reasons why Shoghi Effendi had called Ugo Giachery to Haifa. The first was to consult with him about work in Bahjí, more specifically, the preliminary steps for the construction of the final Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh—the current one being the initial stage, as the original Shrine of the Báb built by 'Abdu'l-Bahá had been before the completion of the superstructure.

The second topic the Guardian wished to consult with Ugo about was the establishment of a Regional Spiritual Assembly for Switzerland and Italy which the Guardian described to Ugo in the following way:

Another great pillar to support the dome of the Bahá'í Administration. I want you to be independent and original, and I know that the Italians and the Swiss are capable of striving for achievements.

Ugo Giachery saw Shoghi Effendi nearly every evening for dinner at the western Pilgrim House, and every time Shoghi Effendi arrived, he brought with him a feeling of ecstatic excitement which affected the hearts of every pilgrim. Ugo Giachery was very deeply affected:

Whenever he came to the table he brought with him a feeling of ecstatic excitement which replenished my soul. Invariably I was filled with a wondrous sensation of continuity and safety…

Every night at dinner, Ugo Giachery felt the towering spiritual perception and vision of Shoghi Effendi, his spiritual strength, his refreshing and stimulating frankness. Shoghi Effendi’s natural curiosity was invigorating, he asked questions of everyone around the table, listening carefully to the answers. When he was asked questions, Shoghi Effendi would answer, sometimes elaborating beyond the scope of the limited question, displaying his immense knowledge with incredible meekness and humility.

This pilgrimage—but more so meeting Shoghi Effendi—changed Ugo Giachery’s life.

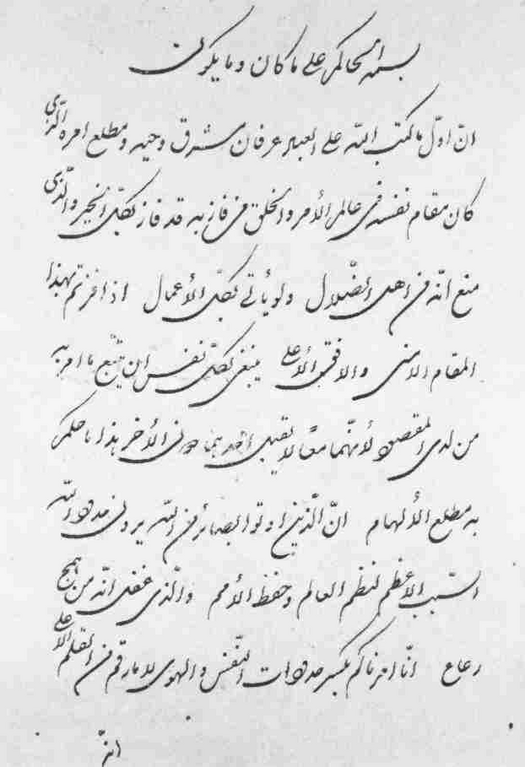

No images could be found of the Kitáb-i-Íqán in 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s handwriting. The image above is the first page of the Kitáb-i-Aqdas in 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s handwriting, which was originally published as the frontispiece of Adib Taherzadeh’s Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 3. Source: Bahaimedia.

One evening, as I entered the dining-room, the Guardian was already seated at his place at the table, his face shining with an inner jubilation which he could neither control nor conceal.

At his side, upon the table, stood a small bundle, an object wrapped in a colored silk handkerchief, typical of the East and of Iran in particular. As soon as we were all seated and attentive, even before dinner was served, he said that a pilgrim had that day arrived from Ṭihrán, bringing with him one of the most precious documents to be placed in the archives.

He untied the handkerchief and with great reverence lifted out a manuscript in book form, and, placing it in a position that everyone could see, added that it contained two original Tablets in the handwriting of 'Abdu'l-Bahá. One was the Kitáb-i-Íqán (The Book of Certitude) and the other was a Tablet.

Shoghi Effendi explained to the pilgrims that these manuscripts had been transcribed by Abdu'l-Bahá in His beautiful calligraphy, when He was about 18 years old. Beyond this fact—astounding on its own—both manuscripts contained notes written by Bahá'u'lláh in His Own hand on the margins of many of the pages, as he had reviewed them.

These precious documents were deeply significant for Shoghi Effendi, because until that night, he had never seen the original text of the Kitáb-i-Íqán and he was astonished to discover that the verse from the Kitáb-i-Íqán he had chosen to place on the epigraph page of The Dawn-Breakers was not in the original text of the Kitáb-i-Íqán as originally revealed by Bahá'u'lláh, but was, in fact, an after-reflection of Bahá'u'lláh’s in one of His handwritten notes in the margins of the manuscript transcribed by 'Abdu'l-Bahá. This was the verse in question:

I stand, life in hand, ready; that perchance, through God’s loving-kindness and grace, this revealed and manifest Letter may lay down his life as a sacrifice in the path of the Primal Point, the Most Exalted Word.

That evening, according to Ugo Giachery, the Guardian was not only astonished but overjoyed with the divine confirmation that through the operation of mysterious, mystical processes he had been inspired to pick out that particular verse from the Kitáb-i-Íqán as the eternal testimonial of Bahá'u'lláh’s deep yearning to sacrifice His life for the Báb’s.

Everyone seated around the table that night was awed and deeply moved to literally witness the evidence of the Guardian’s infallibility and be present to observe and feel the spiritual link between the Guardian and the invisible worlds of God, and his connection to the Báb, Bahá'u'lláh, and 'Abdu'l-Bahá in a single incident.

Facsimile of the Báb’s Tablet to Quddús, the Eighteenth Letter of the Living, and according to the Báb “The first in rank.” From The Dawn-Breakers. Source: The Covenant Library: The Dawn-Breakers.

On other occasions at dinner during Ugo Giachery’s pilgrimage, Shoghi Effendi told the pilgrims stories of how some of the most precious relics in the Archives came to be in his possession, such as the sword of Mullá Ḥusayn, the rings of the Báb, some of the Báb’s garments, and many other relics which he had placed in the International Bahá'í Archives in the three rooms of the Shrine of the Báb.

The Guardian was always eager to educate any Bahá'í that entered his gravitational pull, and spared no effort to reveal and explain episodes from the Heroic Age of the Faith or facts that formed part of the Bahá'í community’s collective heritage and culture, particularly when it came to anything relating to Bahá'í history and the unfoldment of the Faith.

One example was the evening when Shoghi Effendi described for the astonished pilgrims how the priceless Tablets revealed by the. Báb to the Letters of the Living were found by asking the question himself then answering it:

Where did the original Tablets come from, and how is it we have them all in the archives? When the Master passed away, we found the whole set of these Tablets, in the original, twenty in all. They must have been in the papers of the secretary of Bahá'u'lláh, Mírzá Áqá Ján, and must have been given to Bahá'u'lláh years ago.

The Bahá'ís had no knowledge of them during the days of the Master. One Tablet is addressed to the Báb, Himself; the last one, written on blue paper, is addressed to Bahá'u'lláh, "Him Whom God has manifested and will manifest," these last two bear three seals each. In addition we found in the Master's papers Tablets of Bahá'u'lláh addressed to the Master.

It was obvious, with so many priceless relics, that the time had come for the Guardian to build the International Bahá'í Archives. This story is told in full starting in October 1952.

An example of stone carved detail which Ugo Giachery was supervising in Italy for the Guardian. All the details relating to the design and construction of the superstructure to the Shrine of the Báb will be covered in detail in the next part of the chronology. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

William Sutherland Maxwell, Shoghi Effendi’s father-in-law, had passed away on 25 March 1952, and it was after this tragic event in his personal life, that Ugo Giachery had the opportunity to work with the Guardian at the Shrine of the Báb.

Shoghi Effendi had the habit—confirmed by Saichiro Fujita who even said it was like clockwork at 4 PM—of interrupting his administrative work in Haifa in the early afternoon and being driven to the Eastern Pilgrim House right next to the Shrine of the Báb on Mount Carmel.

Because of William Sutherland Maxwell’s passing and the building contractor being ill, the construction work on the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb was progressing very slowly and Ugo Giachery seized the welcome opportunity to assist the head-mason in many details of the construction work, which were intimately familiar to him, as he was the one who had supervised the carving of the marble in Italy.

Ugo Giachery spent hours at the Shrine, and noticed that the Guardian would pace the entire length of the northern gardens, engrossed in his thoughts, then enter the Shrine for prayers, staying quite a long time, then slowly retrace his steps back to his car and driver to return home to his work. It came to Ugo Giachery’s mind that even to the Guardian, the heavenly atmosphere of peace and calm of the Shrine’s gardens offered momentary comfort from physical distress and exhaustion, and provided him with a source of inspiration.

Then, at dinner, Shoghi Effendi would share his day, to Ugo Giachery’s delight:

At night, when at dinner, his dear face, like an open book, would reveal the process undergone during the day, and his warm and enthusiastic conversation would confirm, without any doubt, the new heights scaled in the world of realities.

Shoghi Effendi’s eldest sister Rúhangíz—who had studied in Scotland when Shoghi Effendi was in Oxford—married the eldest son of Ḥájí Siyyid ‘Alí and Furúghíyyih Khánum, Nayyír and they had two daughters.

Nayyír, the son of Abdu'l-Bahá's great enemy, and the man who had married Shoghi Effendi's eldest sister, died in 1952. Shoghi Effendi's cable announcing his death on 5 April 1952 summed up the heart-breaking events of the previous years.

The cable was addressed to the National Spiritual Assembly of the United States for the Bahá'ís of the world.

This cable is significant because the Guardian outlines the depth and breadth of Nayyír’s Covenant-breaking, calling him the “pivot of machinations” and the “connecting link between old and new Covenant-breakers.” The Guardian also states that the spiritual havoc he wrecked on the Faith for over 20 years will take time to comprehend and to assess the damage. But Shoghi Effendi also outlines the misdeeds of Bahá'u'lláh’s third wife, and the grievous sins of the husband of Bahá'u'lláh’s youngest daughter.

(Note, the underlined names are explained below the cable.)

Inform National Assemblies that God's avenging wrath having afflicted in rapid succession during recent years two sons brother and sister-in-law of Archbreaker of Bahá'u'lláh's Covenant, has now struck down second son of Siyyid Ali, Nayer [Nayyír] Afnán, pivot of machinations, connecting link between old and new Covenant-breakers. Time alone will reveal extent of havoc wreaked by this virus of violation injected, fostered over two decades in Abdu'l-Bahá's family. History will brand him [Nayyír] one whose grandmother, wife of Bahá'u'lláh, joined breakers of His Covenant on morrow of His passing, whose parents lent her undivided support, whose father openly accused Abdu'l-Bahá as one deserving capital punishment, who broke his promise to the Bab's wife to escort her to Holy Land, precipitating thereby her death, who was repeatedly denounced by Centre of the Covenant as His chief enemy, whose eldest brother through deliberate misrepresentation of facts inflicted humiliation upon defenders of the House of Bahá'u'lláh in Baghdad, whose sister-in-law is championing the cause of declared enemies of Faith, whose brothers supported him attributing to Abdu'l-Bahá responsibility for fatal disease which afflicted their mother, who himself [Nayyír] in retaliation first succeeded in winning over through marriage my eldest sister, subsequently paved way for marriage of his brothers to two other grandchildren of the Master, who was planning a fourth marriage between his daughter and grandson of Abdu'l-Bahá, thereby involving in shameful marriages three branches of His family, who over twenty years schemed to undermine the position of the Centre of the Faith through association with representatives of traditional enemies of Faith in Persia, Muslim Arab communities, notables and civil authorities in Holy Land, who lately was scheduled to appear as star witness on behalf of daughter of Badí’u’lláh in recent lawsuit challenging the authority conferred upon Guardian of Faith in Abdu'l-Bahá's Testament.

In this cable, Shoghi Effendi speaks of several major Covenant-breakers without stating their names. It is a very important message the Guardian sent the Bahá'í world and in order to understand it fully, these individuals need to be named.

- The “two sons…of Archbreaker of Bahá'u'lláh's Covenant” mentioned by Shoghi Effendi are the following children of Mírzá Muḥammad-'Alí—also known as the Arch-breaker of the Covenant of Bahá'u'lláh, Shu‘á‘u’lláh and Músá;

- The “brother…of Archbreaker of Bahá'u'lláh's Covenant” is Mírzá Muḥammad-'Alí’s brother, Badí’u’lláh.

- “Siyyid Ali…parents…father…mother”: These terms refer to Nayyír’s parents, Ḥájí Siyyid ‘Alí and Bahá'u'lláh’s youngest daughter, Furúghíyyih Khánum;

- “one whose grandmother, wife of Bahá'u'lláh”: Here, Shoghi Effendi is speaking about Bahá'u'lláh’s third wife, Gawhar Khánum, the mother of Furúghíyyih Khánum and grandmother of Nayyír;

- “brothers”: Faydí and Ḥasan Afnán, Nayyír’s brothers: Ḥasan Afnán married Mihrangíz Rabbání, Shoghi Effendi’s’ younger sister and granddaughter of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, and Faydí Afnán married Thurayyá, another one of 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s granddaughters;

- “my eldest sister”: Rúhangíz, Shoghi Effendi’s eldest sister who married Nayyír;

- “two other grandchildren of the Master”: the two other grandchildren of 'Abdu'l-Bahá whom Nayyír conspired to marry to his Covenant-breaking brothers Ḥasan and Faydí: Shoghi Effendi’s younger sister Rúhangíz, and Thurayyá—'Abdu'l-Bahá’s granddaughter from His daughter Túbá Khánum;

- “his daughter and grandson of Abdu'l-Bahá”: Nayyír and his wife Rúhangíz conspired to marry his daughter Bahíyyih—a great-granddaughter of 'Abdu'l-Bahá—to Ḥasan Shahíd—the grandson of 'Abdu'l-Bahá from his daughter, Túbá Khánum.

- “daughter of Badí’u’lláh in recent lawsuit challenging the authority conferred upon Guardian of Faith in Abdu'l-Bahá's Testament”: Badí’u’lláh daughter Sadhijih was a notorious woman with a criminal record, a political agitator who was in prison because of her illegal activities; In 1952, collapse. Sadhijih and another Covenant-breaker still living a run-down shack against the Mansion of Bahjí sued Shoghi Effendi for having demolished another derelict building, claiming that, given they had a one-sixth interest—they should have been consulted prior to the demolition; Shoghi Effendi won the case.

Each one of these letters and cables announcing one more Covenant-breaker—and there are dozens more—were one more heartbreak for Shoghi Effendi, one more agonizing experience for the Guardian.

Covenant-breaking manifested itself through a variety of deeds: lies, plotting, theft, campaigns of defamation, opposition, betrayal, open defiance, lawsuits, Covenant-breaking marriages, misrepresentation of facts, slander, creating divisions and disunity.

In the end, except cause suffering to the Guardian, the Covenant-breakers worldwide did not accomplish anything except further strengthening the fabric of the Bahá'í community and its attachment to Shoghi Effendi and the Covenant of Bahá'u'lláh.

Adib Taherzadeh—author of the Covenant of Bahá'u'lláh—calls Covenant-breaking a “a cleansing process by which the impurities are thrown out of the body of the Cause.”

Shoghi Effendi explained the effect of Covenant-breaking on the Covenant as a strengthening dynamic:

We should also view as a blessing in disguise every storm of mischief with which they who apostatize their faith or claim to be its faithful exponents assail it from time to time. Instead of undermining the Faith, such assaults, both from within and from without, reinforce its foundations, and excite the intensity of its flame. Designed to becloud its radiance, they proclaim to all the world the exalted character of its precepts, the completeness of its unity, the uniqueness of its position, and the pervasiveness of its influence.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum spent a lifetime with Shoghi Effendi and watched him suffer from the misdeeds of his unfaithful family members. She observed that once Mírzá Yaḥyá broke the Covenant just two years after Bahá'u'lláh’s declaration, in 1865 with his attempt to poison Bahá'u'lláh, Covenant-breaking stayed. Mírzá Yaḥyá associated with Siyyid Muḥammad, then Mírzá Muḥammad-'Alí entered the folly followed by Mírzá Majdi’d-Dín, Mírzá Badí’u’lláh, then Nayyír, and all the relatives of 'Abdu'l-Bahá.

The family of 'Abdu'l-Bahá grew up in the tainted shadow of Covenant-breaking. They were reared in an atmosphere where there were spiritual storms, attacks on 'Abdu'l-Bahá, separations, reconciliations, requests for forgiveness, letters of repentance, renewed opposition, final break, public pronouncement of Covenant-breaking.

A Covenant-breaker is like a tumor that is slowly destroying a healthy body—the Bahá'í community. Removing the tumor—excommunicating the Covenant-breaker—is the only way to stop the spread of the disease, but because it is such a final step, because it is so unforgivable, the Center of the Faith tries everything else before shunning the Covenant-breaker.

Bahá'u'lláh and 'Abdu'l-Bahá both suffered through Covenant-breaking attacks, and now it was the turn of Shoghi Effendi to weather this spiritual storm.

Covenant-breaking is part of the unbearable weight carried by the Center of the Faith. Rúḥíyyih Khánum eventually understood that the reason why Covenant-breaking affected Shoghi Effendi so violently, is because, as the Guardian, he had a heightened sensitivity to people’s spiritual states, and Covenant-breaking made him ill:

Gradually I came to understand that such beings [the Centers of the Covenant—the Guardian], so different from us, have some sort of mysterious built-in scales in their very souls; automatically they register the spiritual state of others, just as one side of a scale goes down instantly if you put something in it because of the imbalance this creates. We individual Bahá'ís are like the fish in the sea of the Cause, but these beings are like the sea itself, any alien element in the sea of the Cause, so to speak, with which, because of their nature, they are wholly identified, produces an automatic reaction on their part; the sea casts out its dead.

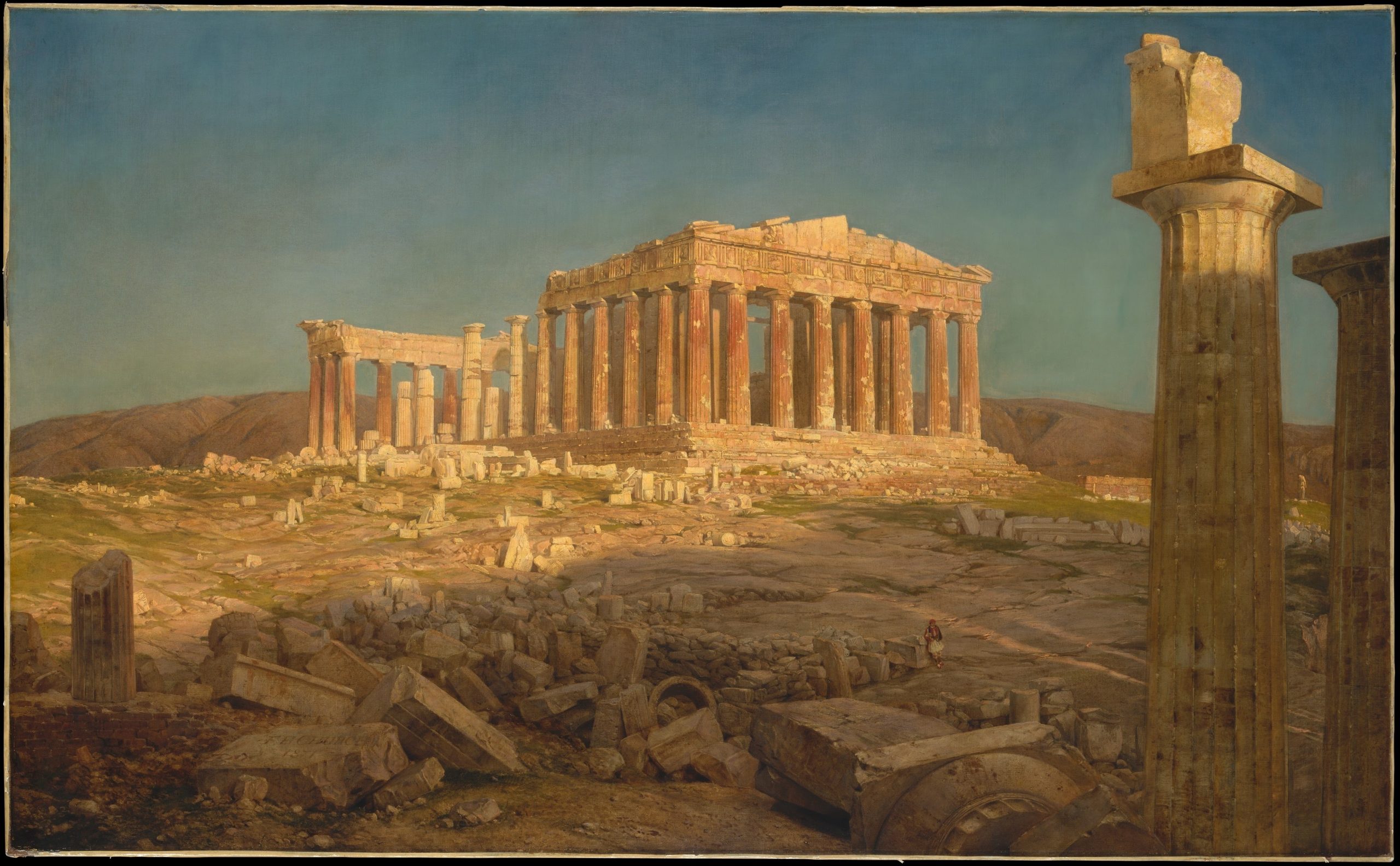

Model for the Mashriqu’l-Adhkár or House of Worship on Mount Carmel, designed by Charles Mason Remey, Hand of the Cause and architect. Source: The Bahá'í World Volume XII, page 548.

By the end of May 1952—at a time when he did not own the Temple Land—the Guardian had approved a design for the first Mashriqu’l-Adhkár—Bahá'í House of Worship—in the Holy Land, and the drawing had been sent to Florence, Italy. A model-maker in Rome produced a wooden architectural model of the design, which was taken to Chicago by Amatu’l-Bahá Ruḥíyyíh Khánum and displayed at the All-American Teaching Conference between 3 – 6 May 1953.

The model was later placed at Bahjí.

The main thing the Covenant-breakers were attached to was humiliating the Head of the Faith, and to that end, they ensured that Shoghi Effendi would be personally summoned as a witness, an act so insulting that it caused the Guardian immense distress. In Ugo Giachery’s words, Shoghi Effendi’s pain was crushing:

His great suffering was for the sacrilege being committed against this Institution of the Faith. It was so abhorrent to him that he felt physically ill, as if 'a thousand scorpions had bitten him.

The Guardian decided to directly appeal the Government to lift the case out of the Civil Court. To this end, the Guardian called in the cavalry. He summoned Ugo Giachery from Rome, Leroy Ioas arrived in Haifa on 10 March 1952. Around the same time the very first American pilgrim arrived in the Holy Land since the Guardian had suspended pilgrimages: Larry Hautz, an insurance salesman. The Guardian asked Larry to stay for three months to assist Leroy Ioas and Dr. Ugo Giachery with acquiring properties around the Holy Places.

Leroy Ioas, Larry Hautz, and Ugo Giachery arrived at a time when the Guardian was deeply worried and preoccupied with the lawsuit the two Covenant-breakers still living in a shack at Bahjí had brought against him and the Faith.

Upon his arrival, the Guardian delegated Leroy Ioas to meet the Covenant-breakers and their clever, hostile lawyer and found himself faced not with people trying tom solve a problem, but with attacks on ‘Abdu’l-Bahá dating back 60 years. Originally, the lawsuit had been filed because the Covenant-breakers had protested Shoghi Effendi’s December 1951 demolition of a run-down house, but as negotiations began, Leroy Ioas realized they had ulterior motives.

It was unclear what it was they wanted, but it was either co-custodianship—with the Guardian—of the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh, or securing their old rooms inside the Mansion of Bahjí, which they had vacated so that the Guardian could repair the dilapidated Holy Place. They wanted back in now that it was restored, which was utterly unthinkable. The Israeli Government, as per Shoghi Effendi’s official application, had changed the status of the Mansion of Bahjí from a place of residence to a place of pilgrimage and the Guardian was its only lawful custodian.

At first, Leroy Ioas found it incredibly difficult even to look at the Covenant-breakers, but the Guardian gave him strict instructions never to lower his eyes “when dealing with him, telling Leroy, to look at them “straight in the eye.” Repugnant as he found it, he learned to deal with them because he was called on to do so, even at times alone when the Guardian was absent.

Attorney General of Israel Haim Cohn. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Three Hands of the Cause called on the Attorney General Haim Cohn, the Vice-Minister of Religions, and officials of the Foreign Office and the Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion’s office.

Attorney-General Haim Cohn informed the president of the Haifa Court that in accordance with a 1924 law, the case in question was a religious matter and not to be tried by a Civil Court.

The Guardian’s brilliant instinct had paid off, but the Covenant-breakers’ devious lawyer appealed to the Supreme Court of Israel on a technicality. This was a serious mistake, because they were now not just attacking the Bahá'ís but the State of Israel.

The Hands of the Cause continued applying pressure, and the Guardian appealed directly to both the Prime Minister, David Ben-Gurion and the Minister of Foreign Affairs Moshe Sharett

The Guardian’s appeals had an immediate effect.

David Ben-Gurion’s legal adviser summoned the Vice-Minister of Religions, the Covenant-breaker’s lawyer, the lawyer for the Hands of the Cause and their clients. The Bahá'ís refused to be in the same room as Covenant-breakers, so they waited in another room of the building. The Covenant-breakers’ lawyer reiterated his clients’ claims, which were passed along to the Hands of the Cause, who rejected each one of their claims.

In the end, the Prime Minister's adviser told the Covenant-breakers that they were free to continue their appeal, but they were now fighting with the State of Israel.

This was when the Covenant-breakers dropped the case.

The Israeli Government issued the authorization to demolish the ruins.

Weeks after these events, on 11 June 1952, the Guardian cabled the Bahá'í world informing them of the successful conclusion to the painful case brought against the Faith by the "blind, uncontrollable animosity" of the Covenant-breakers.

In his message of 11 June 1952 sharing this legal victory won over the Covenant-breakers, Shoghi Effendi recounted the series of devastating failures and defeats encountered by the Covenant-breakers over the past 60 years and described their recent actions as “short-sighted action prompted by blind, uncontrollable animosity.”

As was his lifelong habit, as soon as he had received authorization, the Guardian immediately sprang into action.

A stunning and very rare photograph of Bahjí in the time of 'Abdu'l-Bahá. © United States National Bahá'í Archives, used with permission.

The night before the demolition—48 hours after permission had been granted—the Guardian asked for all available Bahá'í men to meet at Bahjí in the morning for heavy manual labor.

Shoghi Effendi leveled the house, began landscaping the approaches to the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh with eight truckloads of plants and garden ornaments which allowed him to begin embellishing the surroundings of the Shrine, erected a gate, and, as he explained in his message of 11 June 1952 he provided:

Public access to the heart of the Qiblih of the Bahá'í World is now made possible through traversing the sacred precincts leading successively to the Holy Court, the outer and inner sanctuaries, the Blessed Threshold and the Holy of Holies.

Leroy stayed in the Mansion to oversee the work and second the Guardian.

Shoghi Effendi’s chauffeur who carried a ball of string and wooden stakes, and, at the Guardian’s instructions, laid out several paths radiating out from the Shrine of Bahá’u’lláh and one path leading directly to its door. The gardeners planted hedges of thyme along paths.

The Guardian demolished the small buildings between the Mansion of Bahjí and the Shrine of Bahjí.