Written and illustrated by Violetta Zein

This part covers the life of the Báb from the age of 26 in 1845 to the age of 27 in 1846.

The Citadel of Shíráz, where the Báb was interrogated. Source: Freepik premium.

The Báb had returned from pilgrimage and was in Shíráz.

His family was alarmed.

They had heard rumors that the Báb had been arrested. In His large family, only His uncle Ḥájí Mírzá Siyyid ‘Alí and His wife Khadíjih Bagum believed in His Divine Mission and supported Him. The rest of the family, including His mother was skeptical, and one or two family members were against Him, but the family stood by Him nonetheless.

Upon the Báb’s arrival in Shíráz, He was brought straight to the citadel, where Ḥusayn Khán lived, and the Governor received the Báb with patronizing and disrespectful arrogance:

Upon the Báb’s arrival in Shíráz, He was brought straight to the citadel, where Ḥusayn Khán lived, and the Governor received the Báb with patronizing and disrespectful arrogance:

“Do you realise what a great mischief you have kindled? Are you aware what a disgrace you have become to the holy Faith of Islám and to the august person of our sovereign? Are you not the man who claims to be the author of a new revelation which annuls the sacred precepts of the Qur'án?”

The Báb replied with verse 49:6 from Súriy Al-Hujurat (The Inner Apartments) of the Qur’án:

“O believers, if an ungodly man comes to you with a tiding, make clear, lest you afflict a people unwittingly, and then repent of what you have done.”

The Báb’s reply enraged Ḥusayn Khán who ordered an attendant to strike the Báb's face. The Báb was hit so violently that His green turban, the sign of the descendent of the house of the Prophet Muḥammad fell to the ground.

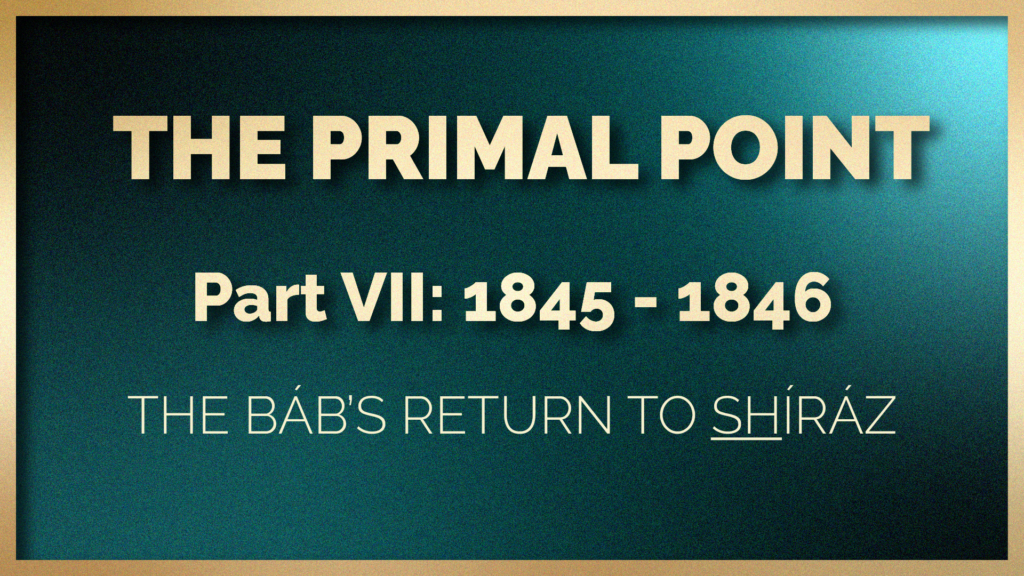

Inside the Citadel of Shíráz, where the scene below takes place. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

In the meantime, Fáṭimih Bagum also pleaded with her brother Ḥájí Mírzá Siyyid ‘Alí to help her Son. He hurried to the citadel and demanded his Nephew’s release. Ḥusayn Khán agreed to let the Báb go home if Ḥájí Mírzá Siyyid ‘Alí promised it would be under conditions of house arrest: no one could meet with the Báb.

Ḥájí Mírzá Siyyid ‘Alí protested that this would be impossible. He explained that because he was a well-known merchant in Shíráz with many friends, connections and acquaintances, many of them would wish to visit the Báb who had just completed His pilgrimage to the holy cities of Mecca and Medina.

Ḥusayn Khán agreed to give the family three days to entertain visitors before banning any further visits, but he had an additional condition:

“We shall require a person of recognised standing to give bail and surety for him, and to pledge his word in writing that if ever in future this youth should attempt by word or deed to prejudice the interests either of the Faith of Islám or of the government of this land, he would straightway deliver him into our hands, and regard himself under all circumstances responsible for his behaviour.”

Ḥájí Mírzá Siyyid ‘Alí agreed to pay the Báb’s bail and act as His guarantor. In his own handwriting, he wrote out the pledge, and affixed his personal seal to it, witnesses confirmed the document, which was then handed to Ḥusayn Khán who remanded the Báb into Ḥájí Mírzá Siyyid ‘Alí’s custody on the condition that His uncle would hand Him back at whatever time the Governor deemed necessary.

Shaykh Abú-Turáb, the leader of Friday Prayer in Shíráz, made a compromise with the family of the Báb. He arranged for the Báb to recant His claim from the pulpit of the Vakíl Mosque, and declare publicly that he was neither the representative of the promised Qá’im, nor an intermediary between the Promised One and the believers.

“Three Days in July”: An artistic interpretations of the three days of freedom the Báb was granted in July 1845 before His months of house arrest. Three panels in transparency over a sunlight interpretation of a photograph of His house in Shíráz. © Violetta Zein

Khadíjih Bagum and Fáṭimih Bagum were at last reunited with the Báb after a separation of almost a year. The first three days of the Báb’s return home were, as His uncle had warned Ḥusayn Khán, filled with visits from friends and relatives, anxious to attain the presence of the Ḥajjí (one who has completed pilgrimage).

These three days were days of joy for the family and friends and the followers of the Báb, basking in joyful reunion. During this time, divine verses kept streaming from the Báb’s lips like a continuous rain, which He recorded Himself on large sheets of cashmere paper and offered the guests visiting Him.

After three days, all visits were denied and no one was allowed to enter the Báb’s presence, but the inventive believers still found a way to communicate with Him through letter writing. They would lay down on paper their religious questions, their requests for guidance and yearning for salvation, and the Báb would respond to each according to their capacity.

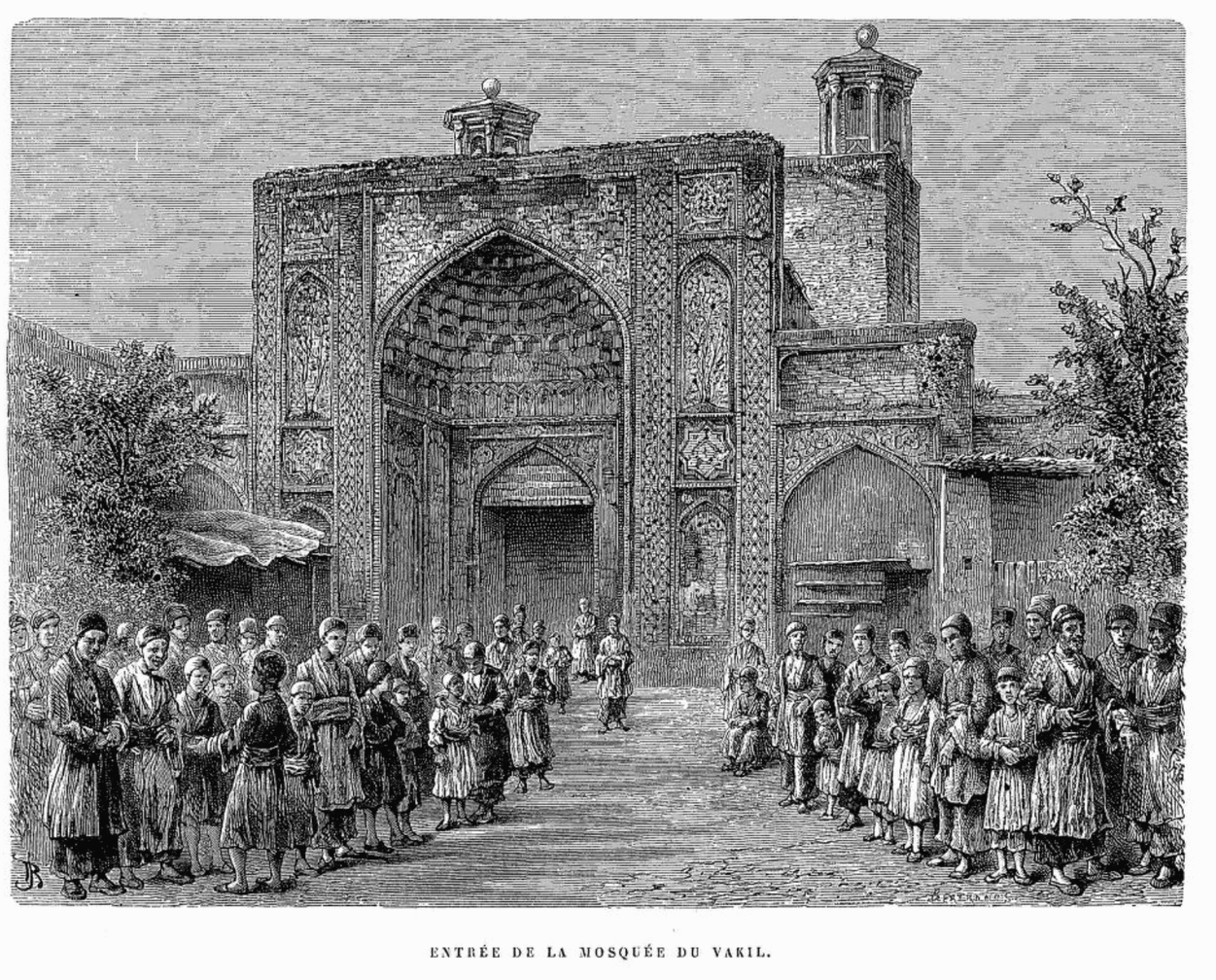

Entrance of Vakil mosque in Shíráz from Jane Dieulafoy, La Perse, la Chaldée et la Susiane, page 422. Source : Archive.org.

With the return of the Báb to Shíráz, the people were wild with excitement.

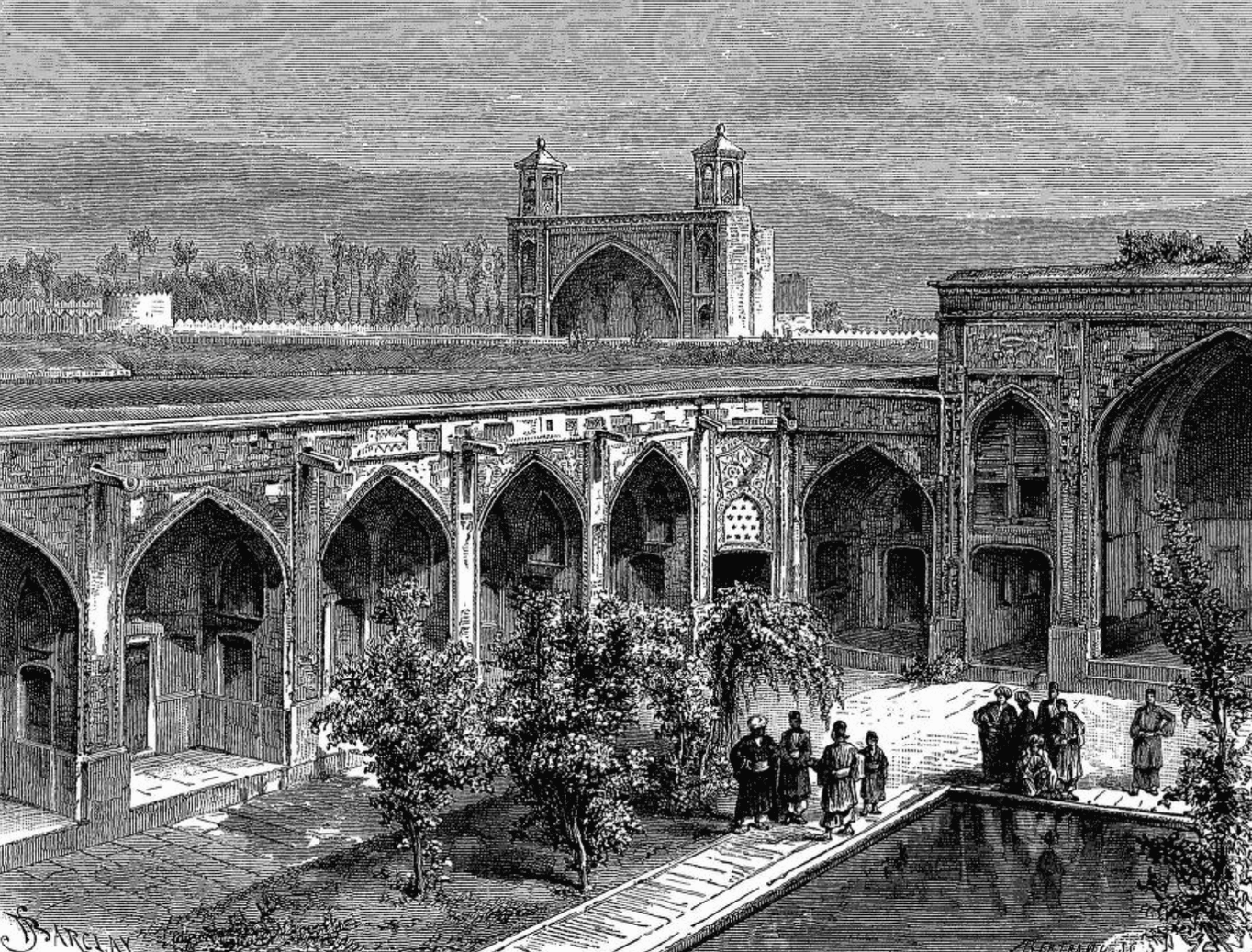

The Governor of Shíráz called all the inhabitants of the city to gather at the mosque of Vakil on a Friday, sometime between July 1845 and March 1846 to hear the Báb renounce His claims.

From morning to three hours before sunset, throngs of people started filling the mosque, with the overflow climbing the roofs and the minarets, and others massing in the courtyard.

The Governor, clerics, merchants, and notables were sitting in the cloisters near the pulpit, comprising of 14 steps and carved entirely out of a single piece of marble. Suddenly, whispers ran through the crowd:

“He is coming!”

The Báb came through the gate accompanied by His uncle, Ḥájí Mírzá Siyyid ‘Alí, and escorted by ten guards. He entered the mosque exuding an indescribable power and dignity just as Shaykh Abú-Turáb, the leader of Friday Prayers had climbed the pulpit and was getting ready to deliver his Friday sermon.

The Báb addressed Ḥusayn Khán and the clerics:

“What is your intention in asking Me to come here?”

They answered:

“The intention is that you should ascend this pulpit and repudiate your false claim so that this commotion and unrest will subside.”

Shaykh Abú-Turáb invited the Báb to join Him on the pulpit and address the congregation.

The one-piece marble pulpit from which the Báb addressed the congregation in the Mosque of Vakíl. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The Báb moved towards him and climbed on the first step of the pulpit to begin addressing those present. The Imám-Jumih interrupted Him and said:

“Come up higher.”

The Báb climbed two more steps, and began prefacing what He was intending to say with some introductory remarks.

The Báb started:

“'Praise be to God, who hath in truth created the heavens and the earth…”

At that moment, He was rudely interrupted by one of the Imám’s assistants who shouted:

“Enough of this idle chatter! Declare, now and immediately, the thing you intend to say.”

Shaykh Abú-Turáb firmly reprimanded the man and put him back in his place:

“Hold your peace and be ashamed of your impertinence.”

Turning to the Báb, Shaykh Abú-Turáb asked Him to be brief, in order to lessen the crowd’s excitement. Shaykh Ḥusayn, the Báb’s enemy spoke to Him harshly, saying:

“Go to the top of the pulpit so that all may see and hear you.”

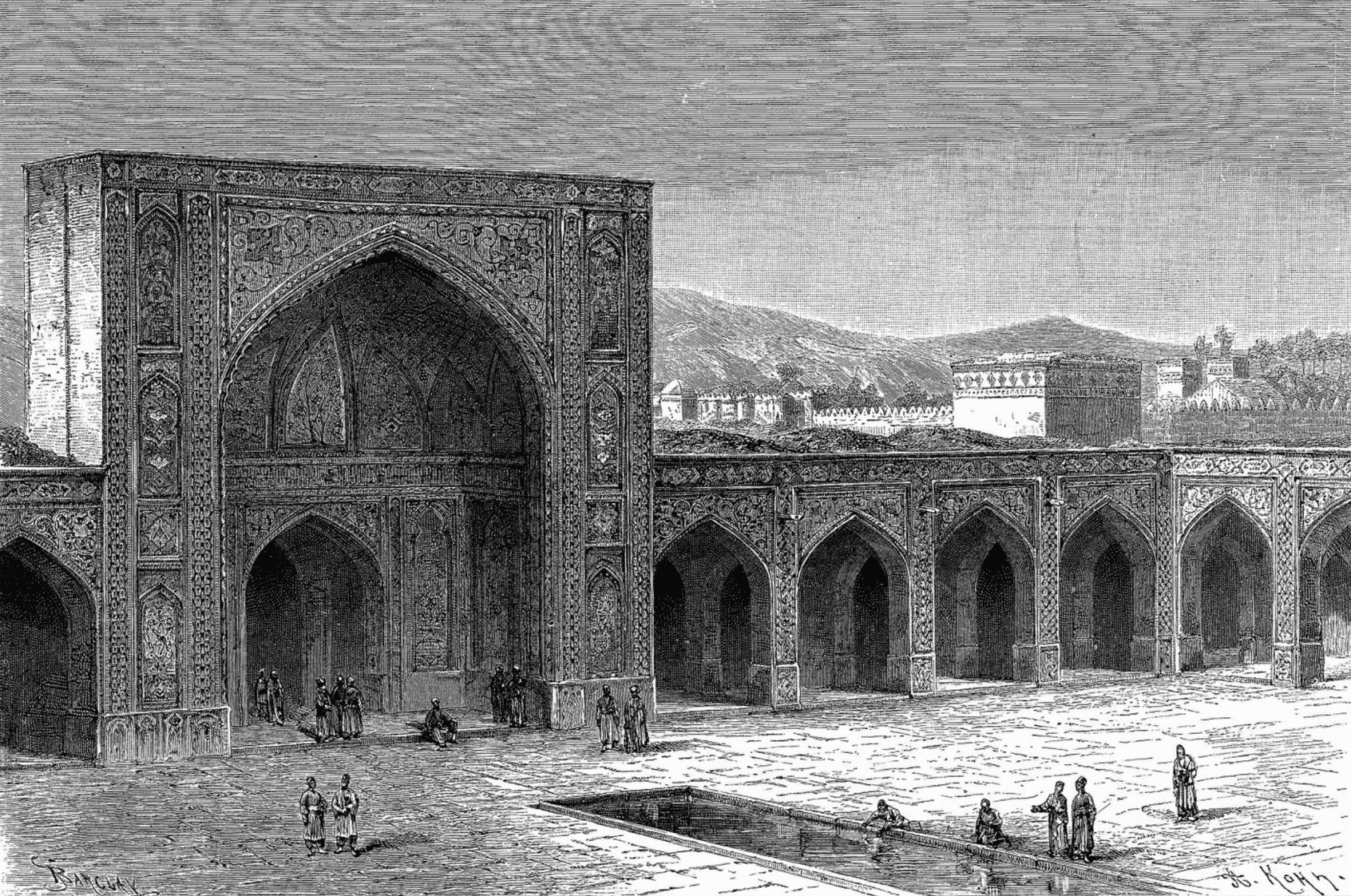

The Báb climbed the rest of the steps to the marble pulpit and sat down at the top. Utter silence fell on the crowd, to the point where it seemed the mosque was totally empty.

Everyone was straining to hear.

Mosque of Vakil where the Báb spoke from the pulpit. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

The Báb began to recite a prayer in Arabic on Divine Unity with such eloquence and majesty that the entire congregation, high and low alike, erudite or illiterate, listened attentively, fascinated.

His address lasted half an hour, and included this passage:

“The condemnation of God be upon him who regards me either as a representative of the Imám or the gate thereof. The condemnation of God be also upon whosoever imputes to me the charge of having denied the unity of God, of having repudiated the prophethood of Muḥammad, the Seal of the Prophets, of having rejected the truth of any of the messengers of old, or of having refused to recognise the guardianship of ‘Alí, the Commander of the Faithful, or of any of the imáms who have succeeded him.”

Instead of the Báb’s expected recantation, His words to the congregation on that Friday silenced and subdued the hostile crowd and strengthened the Faith of His followers. Shaykh Ḥusayn was furious. He turned to Ḥusayn Khán:

“Did you bring this Siyyid here, into the presence of all these people, to prove His Cause, or did you bring Him to recant and renounce His false claim? He will soon with these words win over all these people to His side. Tell Him to say what He has to say. What are all these idle tales?”

Ḥusayn Khán asked the Báb to say what He had to say.

To put into perspective the importance of the Báb’s proclamation from the pulpit of the Mosque of Vakíl, a panorama showing the scale of this mosque. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The Báb was silent for a moment, then addressed the crowd:

“O people! Know this well that I speak what My Grandfather, the Messenger of God, spoke twelve hundred and sixty years ago, and I do not speak what My Grandfather did not. What Muḥammad made lawful remains lawful unto the Day of Resurrection and what He forbade remains forbidden unto the Day of Resurrection and according to the Tradition that has come down from the Imáms, ‘Whenever the Qá'im arises that will be the Day of Resurrection’”

The Báb embraced Shaykh Abú-Turáb, then descended from the pulpit.

Shaykh Ḥusayn-i-‘Arab, the Tyrant, one of the Báb’s fellow pilgrims from the previous year, the man who would have been thrown overboard on the ship to Jiddah if the Báb had not intervened on his behalf, tried to strike the Báb with his walking stick. Someone stepped in, however, and protected the Báb, cushioning the blow with his shoulder.

The Báb then prepared to join in with the congregation for the Friday prayer, but Shaykh Abú-Turáb, fearing the Báb’s life could be in danger after the crowd dispersed, asked his uncle to accompany the Báb home for his protection and safety, saying:

“Your family is anxiously awaiting your return. All are apprehensive lest any harm befall you. Repair to your house and there offer your prayer; of greater merit shall this deed be in the sight of God.”

An engraving of the school inside the Mosque of Vakíl, showing men and clerics speaking, to illustrate the story below where clerics discuss the Báb’s fate and issue a fatwá. Source: Jane Dieulafoy, La Perse, la Chaldée et la Susiane, page 425. Source : Archive.org.

Shaykh Ḥusayn continued to attack the Báb physically and verbally.

The Báb was interrogated and treated with disdain, and at the instigation of Ḥájí ‘Abdu’l-Ḥusayn, a brother of the wife of Ḥájí Mírzá Siyyid Muḥammad, the Báb’s uncle in Shíráz, three Muslim clerics signed the Báb’s death warrant, so that, in their words, they could “finish off this Siyyid.”

Panorama of the Vakil mosque in Shíráz from Jane Dieulafoy, La Perse, la Chaldée et la Susiane, page 423. Source : Archive.org.

By now Fáṭimih Bagum had heard of how her Son had been abused by Shaykh Ḥusayn and Ḥusayn Khán and had become alarmed when she heard about the conspiracy to execute Him.

Fáṭimih Bagum, the sister of Khadíjih Bagum, and a third woman persuaded Shaykh Abú-Turáb, who was a close friend of the family, to find a way out of this impossible situation.

The kind and fair Shaykh Abú-Turáb refused to signed the execution order for the Báb, that the three clerics had brought him. He threw the paper to the ground, angrily, and stated:

"Have you gone out of your minds? I will never put my seal on this paper, because I have no doubts about the lineage, integrity, piety, nobility and honesty of this Siyyid. I see that this young Man is possessed of all the virtues of Islám and humanity and of all the faculties of intellect. There can be only two sides to this question: He either speaks the truth, or He is, as you allege, a liar. If He be truthful I cannot endorse such a verdict on a man of truth, and if He be a liar, as you aver, tell me which one of us present here is so strictly truthful as to sit in judgment upon this Siyyid. Away with you and your false imaginings, away, away!"

If Shaykh Abú-Turáb had signed the verdict, the Báb would have been executed in Shíráz in 1845.

“House arrest”: An artistic interpretation of the futile attempt of the Persian Government to restrain the influence of the Bábí Faith by imprisoning the Báb in His own home. © Violetta Zein

The Báb’s return to His native land after pilgrimage was the spark for a commotion that rocked the entire country.

The fire of the Báb’s Declaration had been lit, and those flames were being fanned as the Letters of the Living and Báb’s followers dispersed throughout the land.

It was during the time that the Báb was under surveillance and house arrest in Shíráz, that the Bábí Faith spread through Persia and the Bábí community was born. This period of time was the most productive of the Báb’s ministry.

The only other time during His ministry that the Báb had been surrounded by disciples was the first few months after His Declaration when the Letters of the Living were being enrolled.

Now again, between 1845 and 1846, significant numbers of Bábís were able to enter His presence, and receive Tablets and instructions from the Báb. It was during this time, for example, that Ḥájí Siyyid Javád-i-Karbilá'í, who had known the Báb from His childhood and visited him in Búshihr, also hurried into His presence and became one of His ardent disciples.

The implications of the Bábí Revelation thrust on the degenerate and inflammable inhabitants of such a corrupt country as Persia could only have the consequences of huge emotions: fear, hate, rage, and envy.

For a story about the Báb’s last Naw-Rúz in the intimacy of His wife and mother, a photomontage of intimate, precious relics of the Báb. The Báb's prayer beads; Cap worn by the Báb beneath His turban; The Báb's signet ring; Dress worn under the jubbih, worn by the Báb; Background: Detail of the arches in the room that the Báb declared. Source for all images: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023. Photomontage design: © Violetta Zein

The Báb celebrated Naw-Rúz 1846 with His wife and mother, and knowing that it would be the last time He would be with both of them in this world, the Báb made the celebration particularly memorable.

He showered Khadíjih Bagum and Fáṭimih Bagum with His love and affection, cheered their hearts with His wise counsels and His tender affection, and dispelled their worries.

During this time, the Bábís of Karbilá had been eagerly awaiting the Báb’s arrival. When they learned that he had been arrested and would not be coming, it shook the faith of a few of them.

The Báb sent instructions to the Bábís of Karbilá and those of Shíráz to leave for Iṣfahán. On the way, in Kangávar, they met Mullá Ḥusayn, who had been headed for 'Iráq, and turned around to accompany them to Iṣfahán.

A modern, joyful image of Zanjan under a double rainbow, for a story of the arrival of the Bábí Faith in that city. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The story of how the Bábí Faith arrived in Zajnán is an indication of how fast and how intensely the Faith of the Báb was spreading between 1845 and 1846 in all of Persia.

In Zanján, there was a scholarly cleric named Mullá Muḥammad ‘Alí, a man of great knowledge, who is better known to us by his title, Ḥujjat (“The Proof”), and was destined to play an unforgettable role in the history of the Bábí Faith. When Ḥujjat heard what had happened in the mosque in Shíráz, he sent a trusted envoy named Mullá Iskandar to investigate carefully.

Mullá Iskandar returned to Zanján with some of the Báb’s writings and found all the leader clerics assembled. Ḥujjat asked Mullá Iskandar whether he believed the Báb’s claim, and Mullá Iskandar made the mistake of answering that whatever Ḥujjat believed, he would also believe.

This angered Ḥujjat:

“How dare you consider matters of belief to be dependent upon the approbation or rejection of others?”

Then Ḥujjat took the copy of the Qayyúmu'l-Asmá' that Mullá Iskandar was handing him, read a single page, and fell to his knees:

“I bear witness that these words which I have read proceed from the same Source as that of the Qur'án. Whoso has recognised the truth of that sacred Book must needs testify to the Divine origin of these words, and must needs submit to the precepts inculcated by their Author. I take you, members of this assembly, as my witnesses: I pledge such allegiance to the Author of this Revelation that should He ever pronounce the night to be the day, and declare the sun to be a shadow, I would unreservedly submit to His judgment, and would regard His verdict as the voice of Truth.”

Ḥujjat had always been passionate, emphatic, and forthright in expressing his views. He announced:

“The season of spring and wine has arrived.”

Then, he climbed the pulpit of his mosque, made his declaration of Faith, and directed the entire congregation to embrace the Faith of the Báb. After this, He wrote his letter of declaration to the Báb.

The rest of the clerics of Zanján tried to quell the effects of Ḥujjat’s declaration, they rose up and passionately admonished the inhabitants but they had no effect, and eventually traveled to Ṭihrán to complain about the Báb to Muḥammad Sháh, asking him to summon Ḥujjat to Ṭihrán.

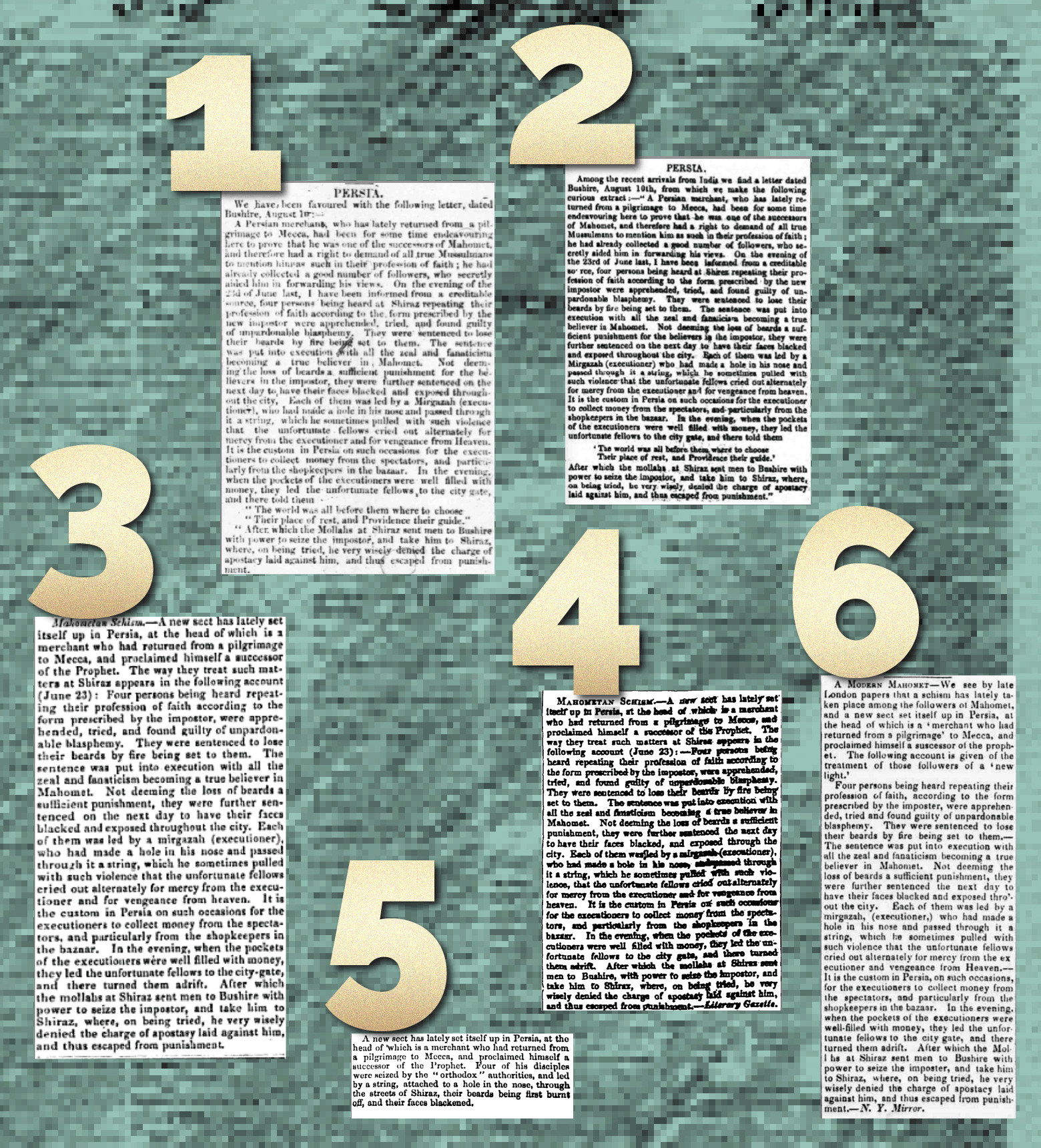

Collage of the first six newspaper articles mentioning the Bábí Faith in England and in the United States. For details on publications and dates of print, see the list of six articles at the bottom of the story below. © Violetta Zein

The period of time that coincides with the Báb’s house arrest and the growth of the Bábí Faith also coincides with the first six mentions of the Bábí Faith in the Western press.

Sometime in late 1845, British merchants reported news of the Báb’s claim to being the Qá’im, Quddús and Mullá Ṣádiq-i-Muqaddas’ change of the call to prayer at the Báb’s request, the Báb’s arrest on His way to Shíráz, and His examination once arrived in His native city.

This is the text of the first article which was published on 1 November 1845 in The Times of London, on page 5, column 6.

This article was reprinted and published in at least 35 articles, in full or in part between November 1845 and July 1846 (see next story):

“We have been favored with the following letter, dated Bushire, August 10:

A Persian merchant, who has lately returned from a pilgrimage to Mecca, had been for some time endeavoring here to prove that he was one of the successors of Mahomet, and there had a right to demand of all true Mussulmans to mention him as such in their profession of faith; he had already collected a good number of followers, who secretly aided him in forwarding his views. On the evening of the 23d of June last, I have been informed from a creditable source, four persons being heard at Shiraz repeating their profession of faith according to the form prescribed by the new impostor were apprehended, tried, and found guilty of unpardonable blasphemy. They were sentence to lose their beards by fire being set to them. The sentence was put into execution with all the zeal and fanaticism becoming a true believer in Mahomet. Not deeming the loss of beards a sufficient punishment for the believers in the impostor, they were further sentenced on the next day to have their faces blacked and exposed throughout the city. Each of them was led by a Mirgazah (executioner), who had made a hole in his nose and passed through it a string, which he sometimes pulled with such violence that the unfortunate fellows cried out alternatively for mercy from the executioner and for vengeance from Heaven. It is custom in Persia on such occasions for the executioners to collect from the spectators, and particularly from the shopkeepers in the bazaar. In the evening, when the pockets of the executioners were well filled with money, they led the unfortunate fellows to the city gate, and there told them:

‘The world was all before them where to choose

Their place of rest, and Providence their guide.’After which the Mollahs at Shiraz sent men to Bushire with power to seize the impostor, and take him to Shiraz, where, on being tried, he very wisely denied the charge of apostasy laid against him, and thus escaped from punishment.”

The report is mainly accurate, although it does contain some errors, but it is significant because it is the very first mention of the Báb in the Western press.

The remaining five mentions which were published between November 1845 and April 1846 also mention the Bábí Faith as a Muslim “schism.”

NOTE: The numbers refer to the clippings in the collage of newspaper clips above the story.

- The Times, London, England, 1 November 1845, page 5, column 6;

- Bradford Observer, London, England, 6 November 1845, page 7;

- Literary Gazette and Journal of the Belles, London, England, 15 November 1845, page 13;

- Patriot, London, England, 20 November, 1845, page 7;

- London Nonconformist, London, England, 26 November 1845, page 11;

- Boon's Lick Times, Fayette, Missouri, 4 April 1846, page 1.

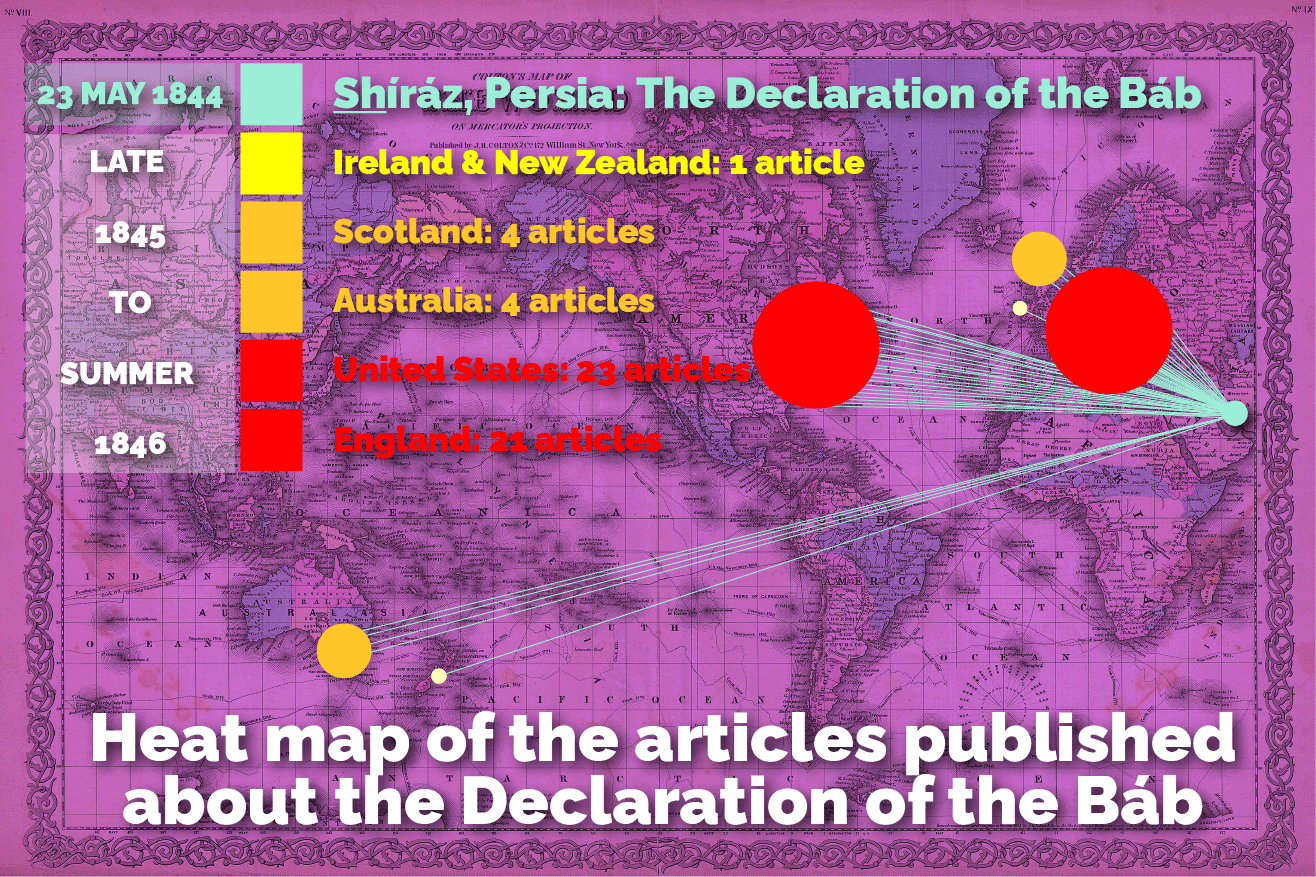

A “heat map” of the 48 articles printed about the Báb between 1845 and 1846 (not an exhaustive list), described in the story below. Original map: 1855 Colton Map of the World on Mercator Projection. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

It is estimated by media expert Steven Kolins (see references) that the 1 November 1845 article by The Times of London was published at least 100 times in English and other languages.

Below is a list of 48 publications—which continues the list of the first six in the previous story—of the article under the title “Muhamedan Schism” that Mr. Kolins has currently identified, between 1 November 1845 and 15 July 1846.

The list of places the article was published covers counties all over England, Ireland, and Scotland, in the states of Kentucky, Maine, Massachusetts, Michigan, Missouri, New Hampshire, New York, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Vermont, Washington DC, and Wisconsin in the United States, Melbourne, Sydney, and Adelaide in Australia, and Wellington in New Zealand, and this listing is far from exhaustive. It is believed this article was published in several languages other than English.

The Báb’s declaration, His claim to be the Qá’im, the change He made to the call to prayer, His arrest and interrogation in Shíráz, made news in every English-speaking country in the world at the time.

These clippings show that the Bábí Revelation and the Báb’s declaration—although not fully understood as an independent world religion—was nonetheless widely reported in the Western Press, from Persia to England and the Antipodes, all the way to New Zealand, 15,000 kilometers (9,300 miles) away.

- Morning Post, London, England, 18 November 1845;

- London Times and London Standard, 19 November 1845;

- Stamford Mercury, Lincolnshire, England, 21 November 1845;

- Newcastle Courant, Tyne and Wear, Newcastle, England, 21 November 1845;

- Leamington Spa Courier, Warwickshire, England, 22 November 1845;

- The Era, London, England, 23 November 1845, page 8;

- Kentish Gazette, Kent, England, 25 November 1845, page 2;

- Freeman's Journal, Dublin, Republic of Ireland, 25 November 1845m, page 4;

- Blackburn Standard, Lancashire, England, 26 November 1845;

- Hereford Journal, Herefordshire, England, 26 November 1845;

- Fife Herald, Fife, Scotland, 27 November 1845, page 4;

- Royal Cornwall Gazette, Cornwall, England, 28 November 1845;

- West Kent Guardian, West Yorkshire, England, 29 November 1845;

- Northern Star, Hereford Times, Herefordshire, England, 29 November 1845, page 9;

- Sherborne Mercury, Dorset, England, 29 November 1845;

- Western Times, Devon, England, 29 November 1845;

- Northern Star and National Trades Journal, Leeds, England, 29 November 1845;

- Liverpool Mercury, Merseyside, England, 5 December 1845;

- New-York Observer, December 27, 1845 New York, New York, 27 December 1845, page 2;

- Boston Courier, Boston, Massachusetts, 29 December 1845, Page 4;

- Christian Intelligencer, New York, New York, 1 January 1846, Page 3;

- Caledonian Mercury, Midlothian, Scotland, 5 January 1846;

- Dundee Courier, Angus, Scotland, 6 January 1846;

- New Hampshire Sentinel, Keene, New Hampshire, 7, January 1846, page 2;

- Dumfries and Galloway Standard, Dumfriesshire, Scotland, 14 January 1846;

- Daily National Intelligencer, Washington DC, January 20, 1846, page 2;

- Boston Evening Transcript, Boston, Massachusetts, 21 January 1846, page 4;

- Evening Post, New York, New York, 22 January 1846, page 1;

- Alexandria Gazette, Alexandria, Virginia, 22 January 1846, page 4;

- Christian Witness and Church Advocate, Boston, Massachusetts, 23 January 1846, page 2;

- Troy Daily Whig, Troy, New York, 26 January 1846;

- Christian observer of Louisville, Kentucky, 30 January 1846;

- Philadelphian, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 30 January 1846, page 4;

- Massachusetts Spy, Wednesday, 4 February 1846, Worcester, Massachusetts, page 2

- Christian Journal, Exeter, New Hampshire, 5 February 1846, page 3;

- Milwaukee Weekly Sentinel, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 6 February 1846, page 3;

- Milwaukee Sentinel, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 6 February 1846, page 2;

- Michigan Argus, Ann Arbor, Michigan, 18 February 1846, page 3;

- Vermont Watchman and State Journal, Montpelier, Vermont, 19 February 1846, page 4;

- Gospel Banner, Augusta, Maine, 21 February 1846 page 4;

- Signal of Liberty, Ann Arbor, Michigan, 23 February 1846, page 3;

- January/February issue of The Eclectic Magazine of Foreign Literature, Science, and Art, New York, New York, February 1846;

- Southern Patriot, Charleston, South Carolina, Volume LV Issue 8305, 24 March 1846, page, 2;

- Port Phillip Herald, Melbourne, Australia, 31 March 1846;

- Morning Chronicle, Sydney, Australia, page 4, 4 April 1846;

- South Australian, Adelaide, Australia, 7 April 1846, page 3;

- South Australian Register, Adelaide, Australia, 11 April 1846, page 3;

- New Zealand Spectator and Cook's Strait Guardian, Wellington, New Zealand; 15 July 1846, page 3.

An illustration of the first Bábís of Shíráz with a 15th century miniature illustrating a poem by one of Shíráz’s most famous sons, Ḥafiẓ, showing Ṣúfís or mystics dancing, two groups of men, sharing the ecstasy of Faith four centuries apart. Source: The Met.

It was during this time that the first real Bábí community in Persia was established in Shíráz. Several Bábís converged to the city where the Báb was under house arrest.

Other Bábís, natives of Shíráz, pledged their allegiance to the Báb after His Declaration in the mosque of Vakil. These first Bábís in Shíráz came from such varied and interesting backgrounds that they deserve mention.

They included the following individuals:

- Shaykh Ḥasan-i-Zunúzí;

- Ḥájí Abu'l-Ḥasan, the Báb’s fellow pilgrim;

- Shaykh-‘Alí Mírzá, the young nephew of the kind leader of Friday prayers, Shaykh Abú-Turáb;

- Ḥájí Muḥammad-Bisát, a close friend of ShaykhAbú-Turáb;

- Mírzá-Áqáy-i-Rikáb-Sáz, the stirrup-maker;

- Luṭf-‘Alí Mírzá, a descendant of the Afshár kings;

- Áqá Muḥammad-Karím, a merchant who eventually had to leave his native city because of intense persecution;

- Mírzá Raḥím, a baker;

- Mírzá ‘Abdu'l-Karím, a key-holder for the Sháh-Chirágh (King of the Lamp) shrine;

- Mashhadí Abu'l-Qásim-i-Labbáf the quilt-maker;

- Mihdí, a renowned poet known by his pen name Ṣábir (“Patient”);

- And Mihdí’s son, Mírzá ‘Alí-Akbar.

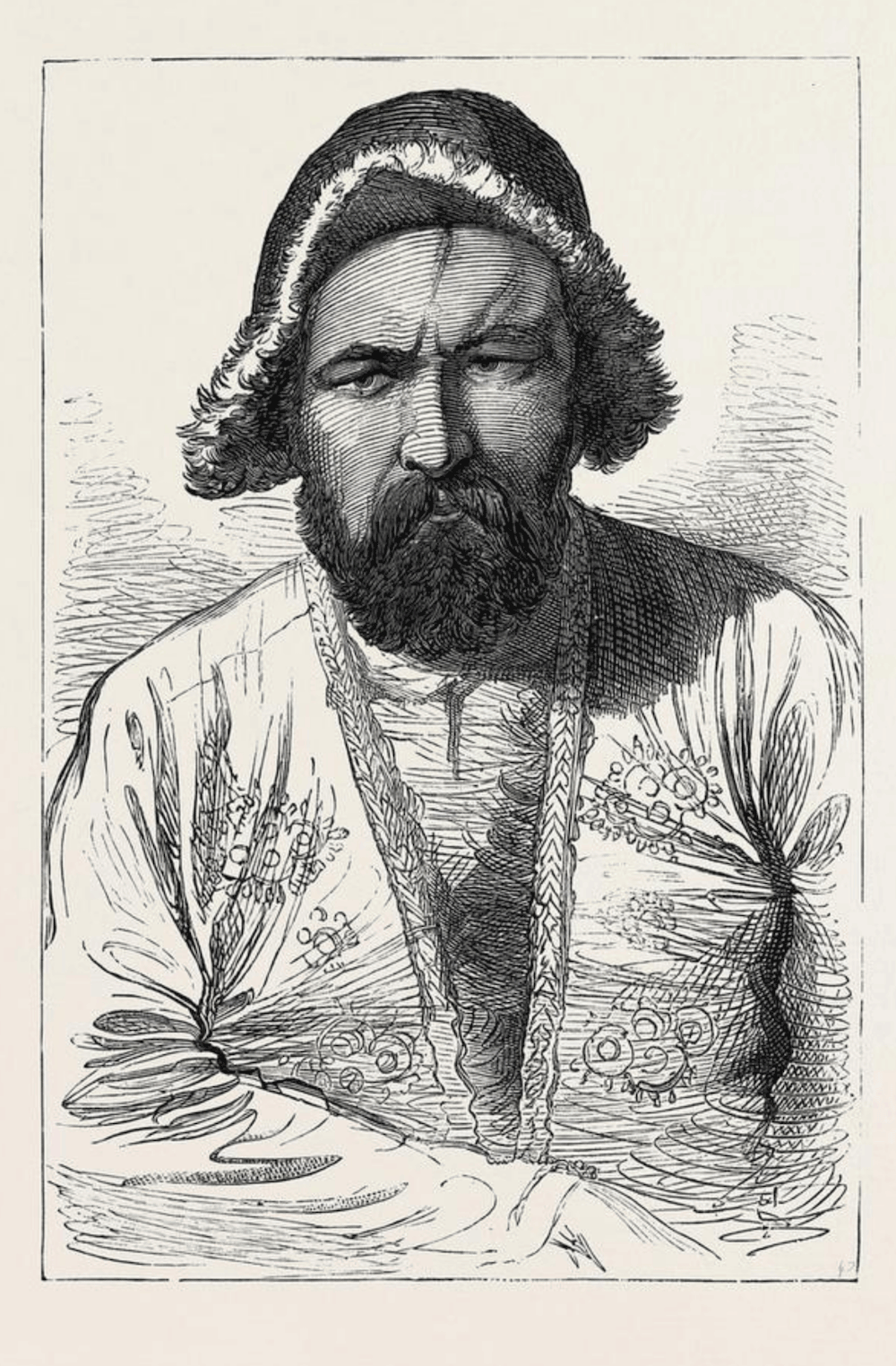

1879 engraving of a Hizárih man from Afghanistan. Mullá Ḥusayn adopted the disguise of this Persian hill tribe from the far Western part of Khurásán, which borders with Afghanistan, to see the Báb in Shíráz. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

When Mullá Ḥusayn arrived in Iṣfahán, he received news the Báb was under arrest in Shíráz, so he discarded his clerical robes and turban and disguised himself as a horseman from the Hizárih tribe.

He arrived in Shíráz and managed to meet the Báb, despite having been recognized by his enemies.

The Báb directed Mullá Ḥusayn to Yazd first, then Khurásán. Around the same time, the Báb also asked other Bábís to leave Shíráz, and He only kept Mullá ‘Abdu'l-Karím as His amanuensis, to record the torrent of Revelation which was daily flowing from His lips.

While the Báb was in Shíráz in 1845/1846, He revealed an epistle called Ṣaḥífiy-i-A‘mál-i-Sanih (Epistle on the Devotional Deeds of the Year), consisting of 14 chapters in which the Báb provides prayers and Tablets of Visitation related to the 12 months of the Islamic lunar calendar.

Partial Inventory ID: BB00025

This commentary may not have been revealed after the Báb’s return from pilgrimage, but since it was revealed sometime before January 1846, its placement at this point in the chronology is symbolic.

In this highly interpretive work, the Báb reveals a detailed commentary on the opening phrase of the Qurán, “In the name of God,” where He discusses the four stations of mystery and analyzes each of the nineteen letters of the opening phrase of the Qur’án as references to the four levels of the divine covenant and equating each of the letters with the sacred figures of the Islamic covenant.

Below is an excerpt from this Commentary on the four levels or stations of mystery:

“Verily God, glorified be He, hath ordained for His revelation unto His creation, through His creation, four stations, which are referred to symbolically within the writings of the Family of God, peace be upon Them, as Mysteries. These stations are Mystery (Sirr), the Mystery of Mystery (Sirru’s-sirr), the Hidden Mystery (Sirru’l-mustasirr), and the Mystery veiled by Mystery (Sirru’l-muqanna’-i-bi’s-sirr). Likewise, they allude to the First Station as the Point, which is the Pivot of the Book of God in both Creation and Revelation.”

Partial Inventory ID: BB00022

In early January 1846, the Báb revealed a commentary known to us by three names: the Sharḥ-i-Du‘á’-i-Ghaybat (Commentary on the Occultation Prayer), also called Tafsír-i-Há’ (Interpretation of the Letter Há’) and Ṣaḥífiy-i-Ja‘faríyyih (Epistle of Ja‘far).

The Sharḥ-i-Du‘á’-i-Ghaybat is an interpretation of a prayer which the Sixth Imám, Ja’far aṣ-Ṣádiq, encouraged believers to recite during the occultation of the Qá’im, composed of 14 chapters.

The occultation of the Qá’im (or Ghayba) is the Shí’ah belief that the Promised One, a descendant of Prophet Muḥammad, had already been born, and was concealed until the moment He reappeared in the last days to establish justice and peace on earth.

The Báb identifies occultation in the Sharḥ-i-Du‘á’-i-Ghaybat with the existential station of forgetting the divine revelation thus requiring prayer in order to regain true self-consciousness. Nine chapters deal with the Báb’s interpretation of various concepts such as the preconditions of true prayer, and in the last three chapters the Báb interprets Imám Ja’far aṣ-Ṣádiq’s occultation prayer.

Because the letter Há’ is often discussed and interpreted, this work is also sometimes referred to as Tafsír-i-Há’ (Interpretation of the Letter Há’).

Partial Inventory ID: BB00012

We are by now familiar with the long epistle the Báb started revealing while He was on pilgrimage in Mecca and Medina in early 1845, the Ṣaḥífiy-i-Raḍavíyyih (Epistle of Riḍá’), which is composed of 14 sermons, most of which were revealed in Saudi Arabia. We saw, earlier on 21 June 1845, that the second sermon of this book was revealed in Búshihr.

The first sermon, Khuṭbiy-i-Dhikríyyih (Sermon of Remembrance), is deeply significant, as it is the first of two listings the Báb made of His own Revelation, and, also significantly, it is one of the last works revealed during the first, interpretive stage of the Báb’s Revelation.

This is highly important because the Khuṭbiy-i-Dhikríyyih, like the Kitábu’l-Fihrist, the second sermon in the Ṣaḥífiy-i-Raḍavíyyih, are both listings of the Báb’s Holy Writings, produced by the Báb Himself, the first covering the first 13 months of His Revelation, and the second covering the first 18 months.

The Khuṭbiy-i-Dhikríyyih, the first of the 14 sermons of the Ṣaḥífiy-i-Raḍavíyyih, lists 14 of the Báb’s Own Writings: 4 books and 10 epistles, identifying the Ṣaḥífiy-i-Raḍavíyyih as number 6.

Partial Inventory ID: BB00137 (First sermon)

Two simultaneous processes begin occurring, starting in January 1846: the Báb put an end to His withdrawal from His followers, and He began to willingly answer questions in Persian.

This period marks the beginning of the second stage of the Báb’s Revelation, from January 1846 to April 1847, the philosophical stage, characterized by the Báb’s use of Persian, innovative after the first Arabic-language stage.

The second stage of the Báb’s Revelation contains its fair share of interpretive works, the overarching theme of the first stage, but the majority of the works revealed by the Báb in the second stage, lasting a little more than a year, are complex philosophical explanations of metaphysical and mystical subjects, such as being, creation, prophethood.

Sometime in late January 1846, halfway through His last sojourn in His native city of Shíráz, the Báb revealed the Ṣaḥífiy-i-‘Adlíyyih (Epistle of Justice: Root Principles), sometimes also called Ṣaḥífiy-i-Uṣúl-i-‘Adlíyyih (Epistle of the Principles of Justice) or The Book of Justice.

This work is important, as it is one of the first Holy Writings revealed by the Báb in the second stage of His Revelation, the Philosophical stage. In the Epistle of Justice: Root Principles, the Báb expounds on the fundamental, root principles of Religion, and in particular, the concept of Justice.

This work is entirely dedicated to the topic of the metaphysics of the Primal Will of God, and is a discourse on the root principles of true Islám.

The Epistle of Justice: Root Principles is also significant because it is the first major work the Báb revealed in Persian.

At the end of the Epistle of Justice: Root Principles, the Báb introduces the subject of the branches of religion as a topic for a future philosophical epistle. That work, revealed after the end of January 1846, is called Epistle of Justice: Branches and is addressed below.

One of the focal points of the Báb’s Epistle of Justice: Root Principles is the fact that the Primal Will of God is both its own Cause and the Cause of all created things. This deeply complex mystical point goes against any duality in traditional philosophy and is one of the Báb’s main arguments in this work in which He expounds upon the false unity proclaimed by those who are deprived of understanding:

“The advocates of the doctrine of the unity of existence are joining partners with God by virtue of the testimony of the idea of existence itself. For the “unity” affirmed by them is derivative of the existence of duality; otherwise why would they deny the duality and affirm the unity? Likewise, those who advocate that the cause of the existence of the contingent beings is the Essence of God, and thus believe in some form of relation between the two, are disbelievers. For causation is dependent on the association with the effect, and relation is dependent on the existence of duality, whereas both conditions are utterly false.”

Partial Inventory ID: BB00017

Sometime after the Ṣaḥífiy-i-‘Adlíyyih (Epistle of Justice: Root Principles), in which He had prefaced the current topic, the Báb revealed another philosophical epistle called the Ṣaḥífiy-i-Furú‘-i-‘Adlíyyih (Epistle of Justice: Branches) in which He discusses various branches and main laws of Islám and states unequivocally the end of Holy War with the advent of His Dispensation.

Partial Inventory ID: BB00039

1840 Mezzotint portrait of Muḥammad Sháh Qajár by J. H. Twigg/ Honorary painter to His Majesty. Source: The British Museum © The Trustees of the British Museum, authorized non-commercial use under a Creative Commons License.

The fire of the Báb’s Declaration caused a commotion that rocked the entire country. The people of Shíráz were wild with excitement and the fever of Bábí passion spread to the members of the clergy and the merchant classes, invading the higher circles of society.

Once Muḥammad Sháh had read the report of what had happened at the Mosque of Vakil, he could no longer ignore the situation and sent his most trusted envoy.

The man’s name was Siyyid Yaḥyá-i-Dárábí, and he was the son of the same greatly-revered Siyyid Ja’fari-Kashfí, who had been one of the Báb’s fellow-pilgrims. We know him better as Vaḥíd.

At the time Vaḥíd lived in Ṭihrán, and was associated with the court of Muḥammad Sháh. He was a highly respected cleric, one of the most learned in all of Persia, famous for having memorized 30,000 Ḥadíths, and he was confident that he could easily overcome the Báb in debate.

Vaḥíd had a very open-minded, highly imaginative, passionate nature, and he had wanted to investigate the claims of the Báb personally, so he rose to the opportunity and set out for Shíráz from Ṭihrán. On the way to Shíráz, Vaḥíd came up with the questions he wanted to ask the Báb, questions that, to his mind, would determine the truth of His Mission.

Vaḥíd arrived in Shíráz, sometime between the end of April and the end of May 1847. He was the guest of the Governor, and Ḥájí Siyyid Javád-i-Karbilá'í arranged a meeting between the Báb and Vaḥíd in the house of Ḥájí Mírzá Siyyid ‘Ali.

Vaḥíd Part II: Arrogance Decorated quote © Violetta Zein. Background: Processed still from The House of the Bab: The Declaration Chamber YouTube video by Oscar Gomez. Design: © Violetta Zein

Arriving in Shíráz, Vaḥíd encountered an old friend, Azim, who advised him to be of the utmost courtesy when speaking to the Báb

During this first meeting, Vaḥíd showed off his knowledge of mysterious traditions, brought up one obscure passages of the Qur’án and abstruse point of theology and learned references to Islamic law after another and asked questions that the Báb answered very briefly but also very convincingly.

Vaḥíd began to feel both humiliated by his own arrogance and in awe and admiration at the Báb’s conciseness and lucidity and even told his friend ‘Aẓím:

“I have in His presence expatiated unduly upon my own learning. He was able in a few words to answer my questions and to resolve my perplexities. I felt so abased before Him that I hurriedly begged leave to retire.”

‘Aẓím reminded Vaḥíd of his initial piece of advice, and begged him not to forget his courtesy in his second interview with the Báb.

He told Ḥájí Siyyid Javád-i-Karbilá'í that if only the Báb would show forth a miracle, his lingering doubts would vanish, to which Ḥájí Siyyid Javád replied that to demand the performance of a miracle, when faced with the brilliance of the Sun of Truth, was tantamount to seeking light from a flickering candle.

Vaḥíd Part III: Astonishment Decorated quote © Violetta Zein. Background: Processed still from The House of the Bab: The Declaration Chamber YouTube video by Oscar Gomez. Design: © Violetta Zein

When Vaḥíd arrived for his second meeting at the home of Ḥájí Mírzá Siyyid ‘Alí, he found that every single question he had wanted to ask the Báb had simply vanished from his mind, but to his utter surprise, he soon realized that the Báb was answering all the questions he had forgotten, in the same clear, concise and convincing manner that was characteristic of Him.

Vaḥíd was too agitated to collect his thoughts and asked permission to leave the Báb’s presence.

Thinking back to the second interview later, Vaḥíd would say:

“I seemed to have fallen fast asleep. “His words, His answers to questions which I had forgotten to ask, reawakened me. A voice still kept whispering in my ear: ‘Might not this, after all, have been an accidental coincidence?’”

When he met ‘Aẓím that night, his friend received him coldly and spoke harshly:

“Would that schools had been utterly abolished, and that neither of us had entered one! Through our little-mindedness and conceit, we are withholding from ourselves the redeeming grace of God, and are causing pain to Him who is the Fountain thereof. Will you not this time beseech God to grant that you may be enabled to attain His presence with becoming humility and detachment, that perchance He may graciously relieve you from the oppression of uncertainty and doubt?”

Vaḥíd Part IV: Belief Decorated quote © Violetta Zein. Background: Processed still from The House of the Bab: The Declaration Chamber YouTube video by Oscar Gomez. Design: © Violetta Zein

Vaḥíd decided that, in the course of his third interview with the Báb, he would ask Him in his innermost heart to reveal a commentary on the Surih of Kawthar, but never to speak his request, and he decided that if the Báb revealed the commentary spontaneously, it would be proof of His Divine Mission, and that Vaḥíd would happily embrace His Cause.

As soon as Vaḥíd entered the presence of the Báb, he was seized with a sense of fear. His arms and legs shook, and he was so shaken with awe and terror that he could not stand. The Báb, witnessing his sad plight, arose, walked towards Vaḥíd, and taking hold of his hand, seated him beside Him, then spoke:

“Seek from Me, whatever is your heart’s desire. I will readily reveal it to you.”

Vaḥíd was speechless with wonder, and as powerless to speak or respond as a newborn baby. The Báb smiled and gazed at him saying:

“Were I to reveal for you the commentary on the Surih of Kawthar, would you acknowledge that My words are born of the Spirit of God? Would you recognise that My utterance can in no wise be associated with sorcery or magic?”

Vaḥíd was so overwhelmed that all he could do was utter a verse from the Qur’án:

“O our Lord, with ourselves have we dealt unjustly: if Thou forgive us not and have not pity on us, we shall surely be of those who perish.”

It was still early afternoon when the Báb asked Vaḥíd to fetch Him His pen-case and some paper, after which He began revealing the commentary on the Surih of Kawthar with astounding lightning-fast speed.

Vaḥíd was bewildered by the incredible speed of His writing, the soft and gentle murmur of His voice, the majesty of His style, and the Báb kept on revealing for hours into the night, after which He chanted the sublime, matchless commentary back to Vaḥíd in a voice of unbearable sweetness.

Vaḥíd was so entranced that, at one point, the Báb sprinkled rose water on his face to revive him.

The Báb revealed the Tafsír-i-Súriy-i-Kawthar (Commentary on the Súrih of Abundance) in answer to Vaḥíd’s unvoiced desire to hear Him dissertate on this theme, towards the end of their interviews, meaning sometime in May 1846.

The Súrih of Abundance is the shortest one of the Qur’án, consisting of only three verses:

“We verily have conferred upon Thee the Kawthar fountain of abundance. Therefore pray unto Thy Lord, and sacrifice. Verily, it is Thine enemy who will be without posterity.”

In His commentary, the Báb addresses the Prophet Muḥammad, defending His everlasting legacy against the taunts of His enemies who had claimed He would be left without posterity because one of His sons had died in infancy.

The Báb’s long commentary interprets the Qur’ánic Súrih of Abundance on various levels of meaning, in a deeply complex interpretation of the Kawthar fountain, and the symbolism of water. The Báb interprets the Kawthar fountain, which flows in paradise as the creative force of the Prophet Muḥammad and the source of His everlasting legacy, not only through His daughter Fáṭimih, but through the Báb Himself, a direct descendent of the Prophet Muḥammad.

In this sense this commentary is an affirmation of the station of the Báb.

Another aspect of the Kawthar fountain, something unique to the Báb’s Writings is His interpretation of its origination of the four rivers and springs of paradise mentioned in the Qur’án, filled with crystal water, fresh milk, pure honey, and delicious red wine, and rivers which are the source of creativity, the origin of a new divine civilization, ushered in by the Báb Himself.

In this touching excerpt of the Tafsír-i-Súriy-i-Kawthar, the Báb relates His Proclamation by the celestial Bird with the sufferings of the Prophet Muḥammad at the hands of His enemies:

“Verily, that which We sprinkled upon thee out of the ocean of Names and Attributes is due to the sweet melodies of This Bird, Who hath first soared in the air of the Supreme Cloud of Subtlety and then warbled in the inner depths of these allusions; thereby it shone forth and was manifest, circled around and revolved, rose up and stood upright,…sighed and bemoaned, cried and wept, then fell with anguish upon the earth, trembling like unto a fish out of water, proclaiming the words of His Lord, as permitted by God: O My God! I plead My grief solely unto Thee. Ennoble My Cause, and fulfill that which Thou hast promised Me…”

Partial Inventory ID: BB00007

Vaḥíd Part V: Certitude Decorated quote © Violetta Zein. Background: Processed still from The House of the Bab: The Declaration Chamber YouTube video by Oscar Gomez. Design: © Violetta Zein

After He had finished the recitation, the Báb left Vaḥíd in the care of Ḥájí Mírzá Siyyid ‘Alí, and the two of them spent three days transcribing the commentary with perfect accuracy. Vaḥíd had reached a state of certitude in his Faith that he stated:

“Such was the state of certitude to which I had attained that if all the powers of the earth were to be leagued against me they would be powerless to shake my confidence in the greatness of His Cause.”

The Báb’s conquest of Vaḥíd was complete.

When he returned to Ḥusayn Khán’s home, the Governor was curious to know if he had fallen victim to the Bab’s magic influence, and Vaḥíd silenced them with his response:

“No one but God, who alone can change the hearts of men, is able to captivate the heart of Siyyid Yaḥyá. Whoso can ensnare his heart is of God, and His word unquestionably the voice of Truth.”

Vaḥíd Part VI: Enkindlement. Decorated quote © Violetta Zein Background: Processed still from The House of the Bab: The Declaration Chamber YouTube video by Oscar Gomez. Design: © Violetta Zein

Ḥusayn Khán could say nothing to Vaḥíd, but he wrote to Muḥammad Sháh and denounced him. The Sháh defended Vaḥíd and reprimanded Ḥusayn Khán, saying:

“It is strictly forbidden to any one of our subjects to utter such words as would tend to detract from the exalted rank of Siyyid Yaḥyáy-i-Dárábí. He is of noble lineage, a man of great learning, of perfect and consummate virtue. He will under no circumstances incline his ear to any cause unless he believes it to be conducive to the advancement of the best interests of our realm and to the well-being of the Faith of Islám.”

The Sháh was also reported to have said, after he had been informed of Vaḥíd’s conversion:

“We have been lately informed that Siyyid Yaḥyáy-i-Dárábí has become a Babi. If this be true, it behoves us to cease belittling the cause of that siyyid.”

Vaḥíd wrote down his account of his interviews with the Báb and submitted them to the Sháh before traveling throughout Persia at the request of the Báb.

Vaḥíd, one of the most prominent clerics of his time, gave up his eminent social position and his hard-won prestige, utterly won over through and through by the Cause and Person of the Báb, who would declare him to be one of the two witnesses of the Cause. Note: The second witness is Quddús, see Part VI: The Letters of the Living, at the end of the biography of Quddús.

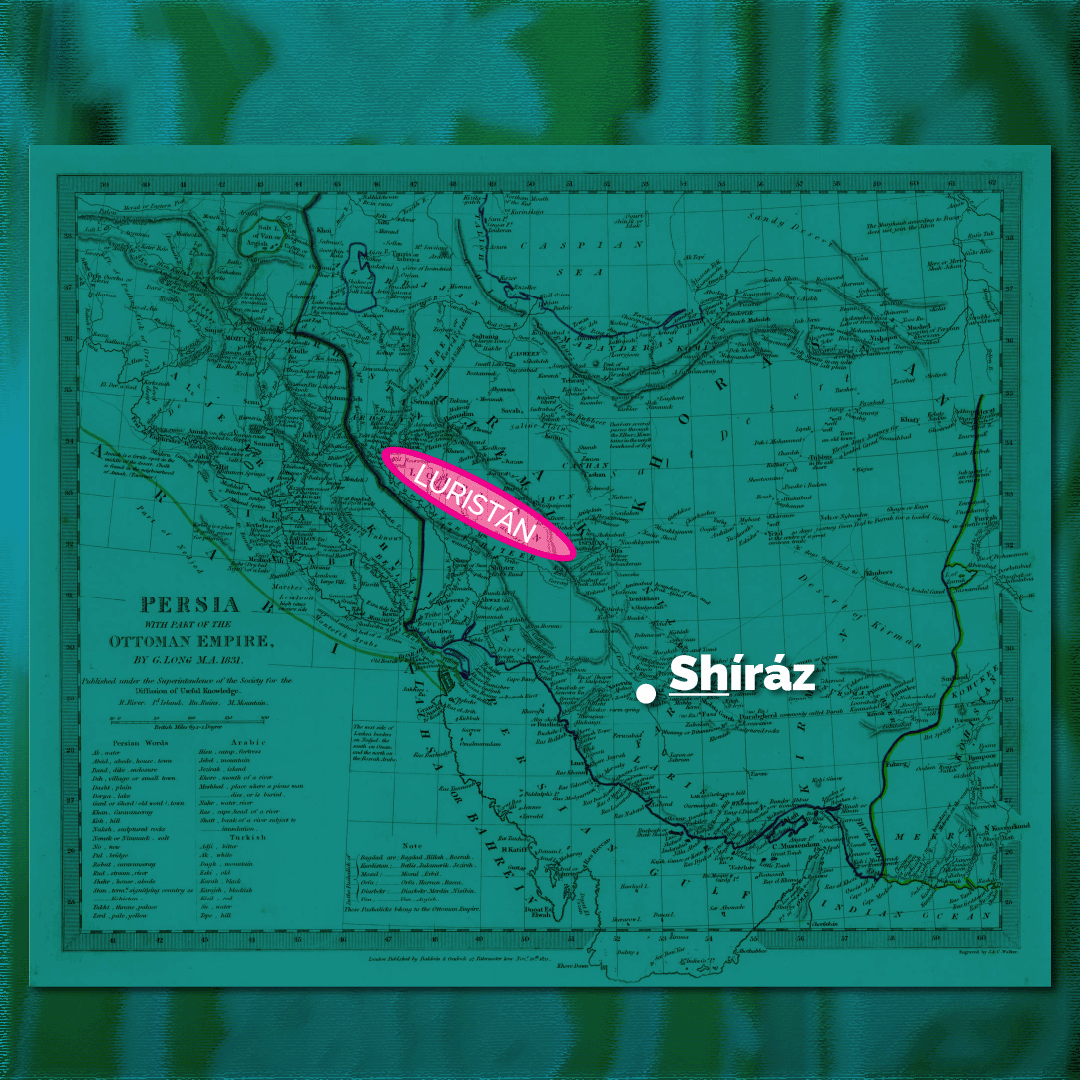

Vaḥíd Part VII: Map of Luristán in relation to Shíráz, the mission the Báb sends Vaḥíd on © Violetta Zein Map source: Luristan in 1831, Persia with part of the ottoman Empire, by G. Long M.A.1831, Wikimedia Commons. Background: Processed still from The House of the Bab: The Declaration Chamber YouTube video by Oscar Gomez.

It was the Báb who gave Siyyid Yaḥyáy-i-Dárábí his new name, Vaḥíd (“the Unique One”).

This story began when Siyyid Yaḥyá-i-Dárábí was sent to Shíráz on a mission by Muḥammad Sháh, the most powerful man in Persia. After his complete conversion and enkindlement, this story ends with the Báb, a Manifestation of God infinitely more powerful than any terrestrial sovereign, sending Vaḥíd on a new, spiritual mission.

The Báb sent Vaḥíd to Burújird in the province of Luristán, where his father lived. His father, Siyyid Ja’far-i-Kashfí, had been one of the Báb’s fellow pilgrims in the winter of 1844, and the Báb asked Vaḥíd to give his father the news of the new Revelation. The Báb expressly instructed Vaḥíd to treat his father with great gentleness.

Although Siyyid Ja’far-i-Kashfí did not reject the Bábí Faith, he also showed no interest in associating with it. Vaḥíd did not insist, and continued on his journey.

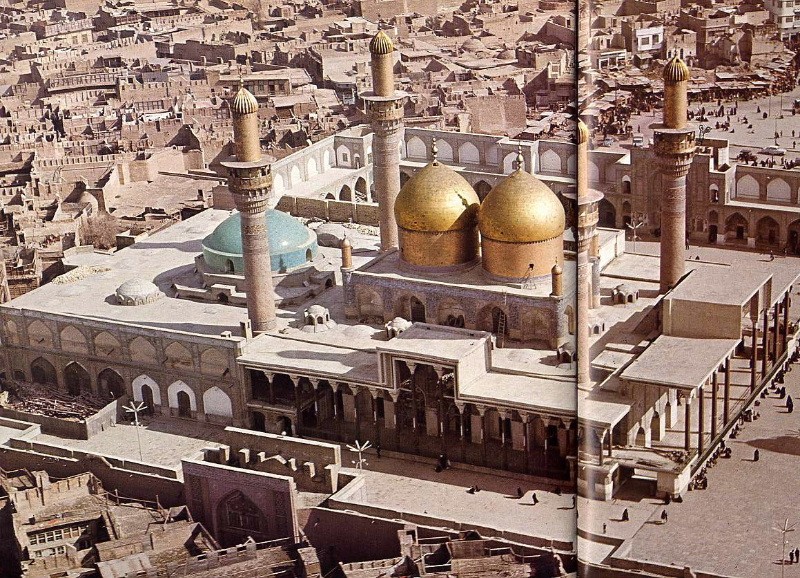

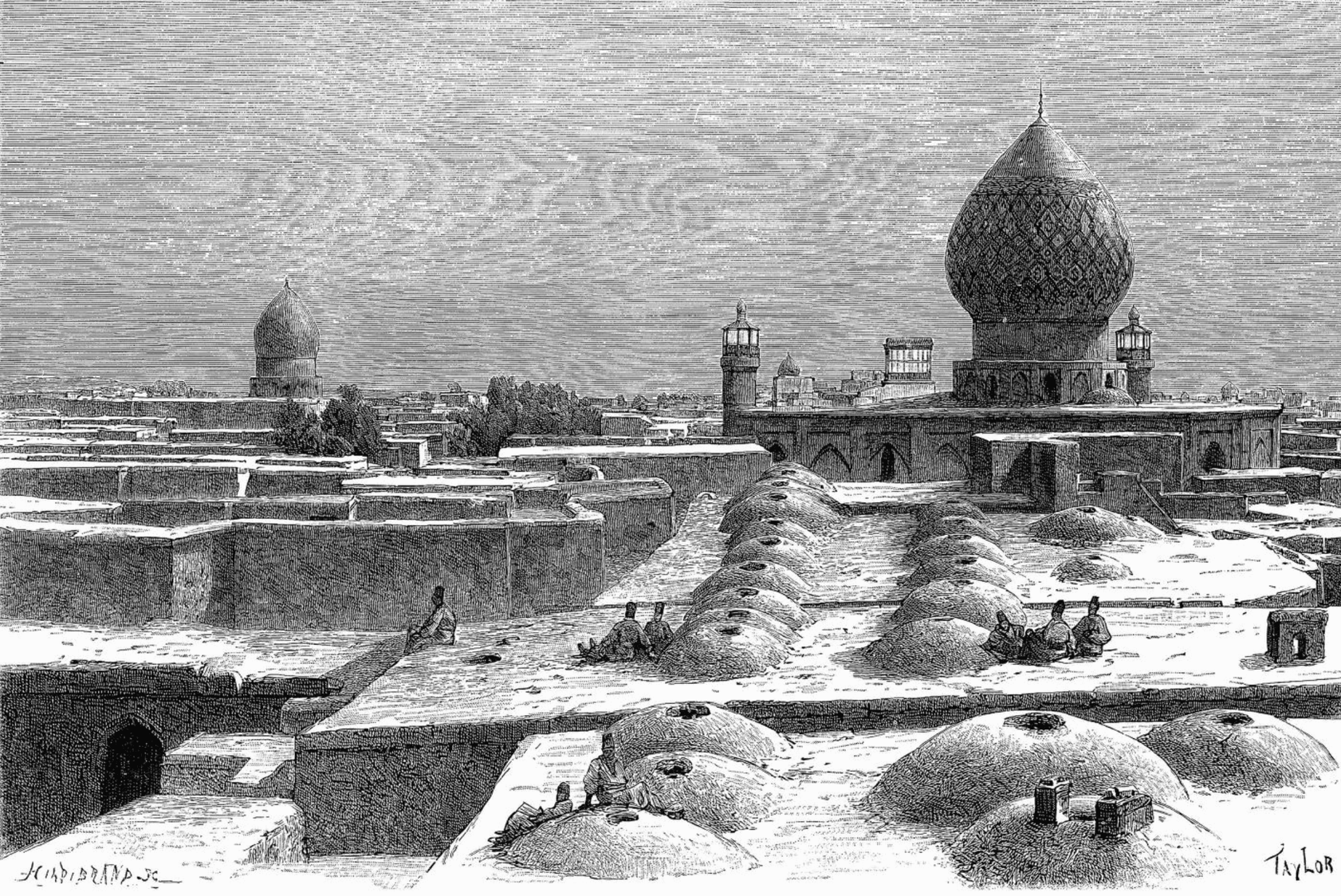

Káẓimayn, the mosque of twin shrines of the Seventh and Ninth Imáms. This is where Ṭáhirih was when the Báb wrote Tablets in her defense from Shíráz. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Because of so much opposition against her in Karbilá, Ṭáhirih, the Seventeenth Letter of the Living, spent six months in Káẓimayn, near Baghdád, between August 1846 and February 1847, fearlessly continuing her very public teaching, calling the people to the Bábí Faith.

Jealous Shaykhís wrote to the Báb, asking if they should respect her opinions, and enquiring what her station was. This was the Báb’s response:

“Concerning what you have inquired about that mirror which has purified its soul in order to reflect the word by which all matters are solved: she is a righteous, learned, active, and pure woman; and do not dispute al-Ṭáhirih in her command for she is aware of the circumstances of the cause and there is nothing for you but submission to her since it is not destined for you to recognize the truth of her status.”

The Báb’s letter was read aloud to 70 Bábís in Káẓimayn. Some were satisfied, but others refused to believe the Báb. In this anti-Ṭáhirih scandal, another of her enemies wrote directly to the Báb, who, in His response, called Ṭáhirih “the pure leaf,” and where He confirmed Ṭáhirih’s claim that she was proof of God’s liberating greatness, adding:

“Let none of those who are my followers repudiate her, for she speaks not save with evidence that has shown forth from the people of sinlessness (the Imams)…”

Despite the fact she was a Letter of the Living, despite even the fact that the Báb had repeatedly defended her and taken her side, despite the fact He gave her a new title, Ṣiddíqih, (“The Truth”), and despite her constant offers of conciliation and cooperation, her enemies never let up, and kept on criticizing and badmouthing her.

Revealed after the Tafsír-i-Súriy-i-Kawthar, the Tafsír-i-Há’ (Commentary on the Letter Há’), revealed in honor of Abu’l-Ḥasani’l-Ḥusayní, a prominent notable of Shíráz.

The Commentary on the Letter Há ’is devoted to disclosing the structure of spiritual reality through an interpretation of the letter Há’.

In this Commentary, the Báb affirms that the seven stages of divine creative Action are identical with the seven stages of the hierarchy of spiritual stations, all diverse reflections of the reality of the Báb.

This complex Commentary identifies the letter Há’ with the word Báb. The Báb’s argumentation is that the word “Báb” is the “lightest” word, a reference to the “good word” of the Qur’án, and related to the Word of divine Revelation and representing the inner and outer truth of Divine Unity: divinity and servitude, represented by its simple structure of an upright Alif (A) between two Bá’s (Bs).

The Báb expounds on this concept in the following passage of the Commentary on the Letter Há’:

“Verily, the letter Há’ is the essence of all the letters and the utmost remembrance of servitude for the Best Beloved. In the realm of the letters, verily it referreth to the Letter of the Crimson Elixir, which purifieth all the words, tokens, signs, and allusions. By virtue of this letter, Divine Unity is affirmed and the realm of pluralities is negated. Verily, those endued with true understanding recognize the truth of all the worlds through the symbolism of this letter, for that which is there cannot be known except through that which is here.

The letter Há’ is the number of that word which is the lightest Word revealed by God in the Qur’án. That letter is identical with that Word in all its outward manifestations and inward meanings. For, verily, the root principle of letters is the point, and when the point unfoldeth, it appeareth as the letter Alif (A), and when the letter Alif submitteth unto its Lord, gate of the heart it becometh the letter Bá’ (B), which is the same as the very letter of Alif, and thus the point is set beneath the letter Bá’.Verily that Word is naught but the upright Alif between the two Bá’s. That referreth to the Cause of God between the Twin Names… Thus God hath not ordained for this Word, unlike the other words, any half, third, or fourth measure, for it is the Manifestation of the everlasting Light, and naught proceedeth from it.”

Partial Inventory ID: BB00021

Revealed shortly after the previous Tablet, Tafsír-i-Sirr-i-Há’ (Commentary on the Mystery of Há’) represents the completion of Tafsír-i-Há’.

In the Commentary on the Mystery of Há’, the Báb emphasizes the incontrovertible testimony of His own writings and identifies recognition of His true station with recognition of the divine revelation that is present within all beings, as the ultimate mystery and truth of all reality.

In both the Commentary on the Letter Há’ and the Commentary on the Mystery of Há’, the Báb explains that any true spiritual journey depends on adopting the perspective of the heart.

This perspective contains two conflicting realities: on the one hand, every created thing reflect the Primal Will of God, but on the other, the Primal Will of God is only reflected in every created thing according to its limited station.

In essence, the truth that the human mind can access and understand is only a faint shadow of the truth that the Manifestation of God perceives. In this sense, the revealed Word of God, the Gospel, the Qur’án, and the Báb’s Holy Writings are the gate of true understanding.

Partial Inventory ID: BB00029

“In the hour of your perplexity”: Decorated words of the Báb to Khadíjih Bagúm. © Violetta Zein

The Báb had written to His followers in Karbilá and explained He had not been able to travel through their city on His return from His pilgrimage and gave them specific instructions:

“Should it be deemed advisable, We shall request you to proceed to Shíráz; if not, tarry in Iṣfahán until such time as God may make known to you His will and guidance.”

That summer, the Báb bequeathed all of His estate and property jointly to Khadíjih Bagum and Fáṭimih Bagum, and moved to the house of His uncle Ḥájí Mírzá Siyyid ‘Alí.

The Báb counselled His wife, Khadíjih Bagum, to be patient and resigned to the will of God and gave her a special prayer which He had Himself revealed and written down, but which has never been identified and gave her the following advice:

“In the hour of your perplexity, recite this prayer ere you go to sleep. I Myself will appear to you and will banish your anxiety.”

Khadíjih Bagum would remain faithful to the Báb’s advice and turned to Him in prayer unfailingly, and He, in turn, by the light of His unfailing guidance, resolved her difficulties and lit the path for her.

For a story where the Báb is taken from the roof of His house, a panorama of the rooftops of Shíráz from Jane Dieulafoy, La Perse, la Chaldée et la Susiane, page 417. Source : Archive.org.

On 23 September 1846, it came to Ḥusayn Khán’s attention that a large number of Bábís were gathering in Ḥájí Mírzá Siyyid ‘Alí’s house. He ordered the chief constable of Shíráz, ‘Abdu'l-Hamíd Khán, to arrest everyone he found there.

Ḥusayn Khán had received secret instructions from the Prime Minister, Ḥájí Mírzá Áqásí to execute the Báb, and he had intended to carry out those orders that night.

That same night, starting at midnight, an epidemic of cholera of biblical proportions swept Shíráz, starting at midnight, and killing hundreds. Coffins were carried through the streets and the inhabitants of Shíráz were so terrified by the devastation of the epidemic that they fled, confused, amidst screams of pain and grief for the dead. Three of the Governor’s servants had already succumbed to the epidemic, and to save himself, Ḥusayn Khán fled the city.

‘Abdu'l-Hamíd Khán and his men scaled the wall of Ḥájí Mírzá Siyyid ‘Alí’s’ house and entered it through the roof, while the women were asleep, but only found the Báb with his uncle and one other Bábí, Siyyid Káẓim-i-Zanjání.

The Báb and His disciple were arrested, and all his books and papers confiscated, and the constable took him to his own house.

“I will again meet you”: Decorated words of the Báb to His beloved uncle Ḥájí Mírzá Siyyid ‘Alí, heartbreaking premonitory words about their martyrdom, placed on a backgrounds of painted mountains to the northeast of Tabríz. © Violetta Zein

When they arrived, the constable discovered his two sons had fallen ill to the cholera epidemic and he begged the Báb to heal them. It was, by this point, time for morning prayer, and the Báb gave ‘Abdu'l-Hamíd Khán some of the water He had used for His ablutions and instructed the constable to have his son drink it.

After his sons had recovered, ‘Abdu'l-Hamíd Khán was so grateful and happy that he begged Ḥusayn Khán to show mercy to the Báb.

Ḥusayn Khán agreed on the condition the Báb left Shíráz, never to return again.

The Báb did not have the time to say goodbye to Fáṭimih Bagum or Khadíjih Bagum, so He sent a message to his uncle, Hájí Mírzá Siyyid ‘Alí, asking him to come to see Him in the home of ‘Abdu’l-Hamíd Khán. During that farewell meeting, the Báb informed His uncle that He would be leaving Shíráz and entrusted both His mother and His wife to his care, and charged him to convey to each the expression of His affection and the assurance of God’s unfailing assistance, telling His faithful uncle:

“Wherever they may be, God’s all-encompassing love and protection will surround them. I will again meet you amid the mountains of Ádhirbayján, from whence I will send you forth to obtain the crown of martyrdom. I Myself will follow you, together with one of My loyal disciples, and will join you in the realm of eternity.”

The next day, on 24 September 1846, after nearly 15 months with His wife and mother in Shíráz, the Báb left ‘Abdu'l-Hamíd Khán’s house, accompanied by Siyyid Káẓim-i-Zanjání and headed for Iṣfahán.

“Ashamed”: Decorated excerpt from a letter from Ḥájí Mírzá ‘Abu’l-Qásim in Shíráz to Ḥájí Mírzá Siyyid Muḥammad in Búshihr, which shows the repercussions of the Proclamation of the Báb and the fire of the Bábí Faith in Persia on all of the Báb’s immediate family. Background digital painting of details fo the Vakíl mosque ceiling © Violetta Zein

Ḥusayn Khán turned his anger to the Báb’s distressed family, and he first threatened Ḥájí Mírzá Siyyid ‘Alí. After this, he ordered his men to break into the house of Ḥájí Mírzá ‘Abu’l-Qásim, Khadíjih Bagum’s brother, who was gravely ill. They dragged him out and brought him to Ḥusayn Khán’s residence, insulted him and fined him. Because he was unable to walk, porters had to carry him home.

Ḥusayn Khán warned the people of Shíráz that if anyone was caught with so much as a sheet of the Báb’s Writings, they would be severely punished. Terrified Shírázís brought bundles of the Báb’s Writings that they had and threw them into the open portico of Ḥájí Mírzá ‘Abu’l-Qásim’s house, terrified of being caught with the now incriminating papers.

So many stacks of paper were deposited that one side of the courtyard was filled with the Writings of the Báb, stacked high, all penned in His beautiful Hand, on large, exquisite sheets of cashmere paper.

Ḥájí Mírzá Siyyid ‘Alí advised his family to take these sheets of Holy Writings of the Báb and wash away the ink in large tubs by hand, and bury the blank sodden papers, a more respectful way of disposing of the Holy Writings.

During this time, Ḥusayn Khán rounded up the Báb’s followers and devotees and had them severely beaten, after which he extorted whatever money he could from them.

In the middle of this new confusion, Ḥájí Mírzá ‘Abu’l-Qásim, who wanted to settle his business affairs so he could take his family away from Shíráz to safety, wrote to Ḥájí Mírzá Siyyid Muḥammad, the Báb’s uncle who was still in Búshihr, and apprised him of the situation.

A family member, related to the Báb by marriage, was now denouncing the Báb and His uncle in Shíráz, and he asked him to come to Shíráz as soon as he could to help Ḥájí Mírzá Siyyid ‘Alí settle the family affairs. He warned his uncle:

“Some people may feel ashamed and keep within bounds when they see you.”

Ḥájí Mírzá Siyyid ‘Alí’s house was raided one or two days after the letter was sent.

REFERENCES FOR PART VII

7 July 1845: Ḥusayn Khán strikes the Báb

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, pages 88-89 and page 99.

Baharieh Rouhieh Ma’ani, Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees, page 12.

7 July 1845: The Báb’s family intervenes

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, pages 88-89 and page 99.

Baharieh Rouhieh Ma’ani, Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees, page 12.

DATE

Mírzá Habibu’llah Afnan (Translated and annotated by Ahang Rabbani), The Genesis of the Bahá’í and Bábí Faiths in Shíráz and Fárs (Translation of Táríkh Amrí Fárs Va Shíráz), published in Numen Book Series: Studies in the History of Religions (Texts and Sources in the History of Religions) Volume 122, BRILL (2008), page 35.

7 – 10 July 1845: First three days in Shíráz

Mírzá Habibu’llah Afnan (Translated and annotated by Ahang Rabbani), The Genesis of the Bahá’í and Bábí Faiths in Shíráz and Fárs (Translation of Táríkh Amrí Fárs Va Shíráz), published in Numen Book Series: Studies in the History of Religions (Texts and Sources in the History of Religions) Volume 122, BRILL (2008), page 38.

The Báb in the Masjid-i-Vakíl Part I: The arrival

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, pages 94-98.

Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, pages 151-154.

The Báb in the Masjid-i-Vakíl Part II: The sermon

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, pages 94-98.

Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, pages 151-154.

The Báb in the Masjid-i-Vakíl Part III: The prayer

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, pages 94-98.

Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, pages 151-154.

The Báb in the Masjid-i-Vakíl Part IV: The public proclamation

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, pages 94-98.

Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, pages 151-154.

The Báb in the Masjid-i-Vakíl Part V: The Fatwá

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, pages 88-89 and page 99.

Baharieh Rouhieh Ma’ani, Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees, page 12.

Fáṭimih Bagum intercedes for the Báb

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, page 89 and page 99.

Baharieh Rouhieh Ma’ani, Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees, page 12.

Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, pages 151-152.

Mírzá Habibu’llah Afnan (Translated and annotated by Ahang Rabbani), The Genesis of the Bahá’í and Bábí Faiths in Shíráz and Fárs (Translation of Táríkh Amrí Fárs Va Shíráz), published in Numen Book Series: Studies in the History of Religions (Texts and Sources in the History of Religions) Volume 122, BRILL (2008), pages 43-44.

July 1845 to September 1846: The Báb is under house arrest

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, pages 89-90.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

21 March 1846: Naw-Rúz with Khadíjih Bagúm and Fáṭimih Bagum

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, pages 89 and 104.

Baharieh Rouhieh Ma’ani, Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees, page 13.

The Faith of the Báb reaches Zanján

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, pages 99-101.

Mullá Ḥusayn arrives in Shíráz

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, page 103.

1 November 1845 – 4 April 1846: Earliest reference to the Bábí Faith in the Western press

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, pages 76-77.

Steven Kolins, First newspaper story of the events of the Bábí Faith (2013).

18 November 1845 – 15 July 1846: Wildfire: Press articles around the world

REFERENCES

Steven Kolins personal weblog: Thus it is blogged: It was in the news…, Thursday 9 February 2016, accessed Sunday, 12 March 2023.

Steven Kolins, Bahaipedia: Persia – or – Mahometan Schism.

Steven Kolins, Historical mentions of the Bábí and Bahá’í Faiths.

Steven Kolins, Travelers and scholars on the Bábí and Bahá’í Faiths.

Steven Kolins, Bahá’í period of historical mentions.

The growth of the Bábí community of Shíráz

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, page 103.

Vaḥíd Part I: Muḥammad Sháh sends an envoy to interrogate the Báb

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, page 90.

Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, pages 170-173.

Vaḥíd Part II: Vaḥíd’s first interview with the Báb: Arrogance

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, page 90.

Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, page 173.

Vaḥíd Part III: Vaḥíd’s second interview with the Báb: Astonishment

Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, page 173.

Vaḥíd Part IV: Vaḥíd’s third interview with the Báb: Belief

Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, pages 173-175.

REVELATION: May 1846: Tafsír-i-Súriy-i-Kawthar (Commentary on the Súrih of Abundance)

Nader Saiedi, Gate of the Heart: Understanding the Writings of the Báb, pages 33, 69-72, and 80.

Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, pages 175-176.

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, page 92.

Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, page 176.

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, pages 92-93.

Vaḥíd Part VII: The Báb sends Vaḥíd on a mission

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, pages 93-94.

August 1846 – Late 1846: The Báb defends Ṭáhirih

Janet Ruhe-Schoen, Rejoice in My Gladness, pages 171-172.

REVELATION: 1845/1846: Ṣaḥífiy-i-A‘mál-i-Sanih (Epistle on the Devotional Deeds of the Year)

Nader Saiedi, Gate of the Heart: Understanding the Writings of the Báb, page 31.

Nader Saiedi, Gate of the Heart: Understanding the Writings of the Báb, page 32.

Wikipedia: Occultation (Islam).

REVELATION: Before January 1846: Tafsír-i-Bismilláh (Commentary on Bismilláh)

Nader Saiedi, Gate of the Heart: Understanding the Writings of the Báb, pages 31 and 132.

REVELATION: Late January 1846: Khuṭbiy-i-Dhikríyyih (Sermon of Remembrance)

Nader Saiedi, Gate of the Heart: Understanding the Writings of the Báb, pages 23, 29, 32, and 217.

REVELATION: January 1846 – April 1847: Second stage of Revelation: Philosophical

Nader Saiedi, Gate of the Heart: Understanding the Writings of the Báb, page 27.

Nader Saiedi, Gate of the Heart: Understanding the Writings of the Báb, pages 32-33, 191-192, 217, and 219.

Nader Saiedi, Gate of the Heart: Understanding the Writings of the Báb, pages 33 and 362.

REVELATION: Between May and September 1846: Tafsír-i-Há’ (Commentary on the Letter Há’)

Nader Saiedi, Gate of the Heart: Understanding the Writings of the Báb, pages 33 and 222-223.

REVELATION: Shortly after Tafsír-i-Há’: Tafsír-i-Sirr-i-Há’ (Commentary on the Mystery of Há’)

Nader Saiedi, Gate of the Heart: Understanding the Writings of the Báb, page 34.

Summer 1846: Preparations for His departure

Nabíl, The Dawn-Breakers, pages 191-192.

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, page 103.

23 September 1846: The Báb is taken from His house

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, pages 103-105.

Baharieh Rouhieh Ma’ani, Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees, page 13-15.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, page 198.

23 September 1846: The Báb saves ‘Abdu’l-Hamíd Khán’s sons

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, pages 103-105.

Baharieh Rouhieh Ma’ani, Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees, page 13-15.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, page 198.

End of September 1846: Repercussions on the Báb’s family

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, pages 105-107.

Mírzá Habibu’llah Afnan (Translated and annotated by Ahang Rabbani), The Genesis of the Bahá’í and Bábí Faiths in Shíráz and Fárs (Translation of Táríkh Amrí Fárs Va Shíráz), published in Numen Book Series: Studies in the History of Religions (Texts and Sources in the History of Religions) Volume 122, BRILL (2008), page 47.

7 July 1845: Ḥusayn Khán strikes the Báb

7 July 1845: Ḥusayn Khán strikes the Báb