Written and illustrated by Violetta Zein

This part covers the life of Shoghi Effendi from the age of 40 in 1937 to the age of 41 in 1938.

As with all books by Bahá'í authors on the subject of Shoghi Effendi—or in this case, his extended family—we would like to pay a tribute to the research of our fellow historians and introduce you two precious books which should be in your library.

These books certainly fit that description.

Violette Nakhjávání is a Bahá'í author. She was the travel companion and assistant of Hand of the Cause Amatu’l-Bahá Rúḥíyyih Khánum for 37 years, but she is also the daughter of Hand of the Cause and one of the first pioneers to Kampala, Uganda, Músá Banání, and she is the wife of ‘Alí Nakhjávání, member of the Universal House of Justice for 40 years since its inception in 1963. She passed away in 2011 in France.

In 2011 the late Violette Nakhjávání published two extraordinary, historical books of great importance: The Maxwells of Montreal: Early Years 1870 – 1922 and The Maxwells of Montreal: Middle Years 1923 – 1937 Late Years 1937 – 1952.

The Maxwells of Montreal is the biography of three people: May Maxwell, William Sutherland Maxwell, and their daughter, Amatu’l-Bahá Rúḥíyyih Khánum. Two Hands of the Cause and one Martyr, one family, bonded together by their love for each other and for the Guardian.

Volume 1: The Maxwells of Montreal: Early Years 1870 – 1922, covers the respective birth, childhood, youth, of May Bolles and William Sutherland Maxwell, May’s pioneering in Paris, May and William Sutherland Maxwell’s marriage, their pilgrimage to the Holy Land in 1909, the visit of 'Abdu'l-Bahá to their home in 1912, and the Ascension of 'Abdu'l-Bahá.

The Maxwells of Montreal: Middle Years 1923 – 1937 Late Years 1937 – 1952 completes the story of the Maxwell Family, covering the story of May and Mary Maxwell’s 1923 – 1924 pilgrimage, their extensive teaching activities in North America and Europe, the marriage of Shoghi Effendi and Rúḥíyyih Khánum, the death of May Maxwell, the life of William Sutherland Maxwell in the Holy Land as the architect of the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb, his elevation as a Hand of the Cause and his passing.

Both volumes draw on over 1,600 personal letters between May, Sutherland and Mary Maxwell (Amatu’l-Bahá Rúhíyyih Khánum), as well as 1,400 letters which the three Maxwells exchanged with their relatives and some of the early Bahá’ís. Included in this incredible collection are the last Tablet May Maxwell received from ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, cables from Shoghi Effendi, excerpts from Rúhíyyih Khánum’s notebooks, sketches made by her father, and articles and photographs related to the period.

All this primary source material was personally gathered by Hand of the Cause, Amatu’l-Bahá Rúḥíyyih Khánum.

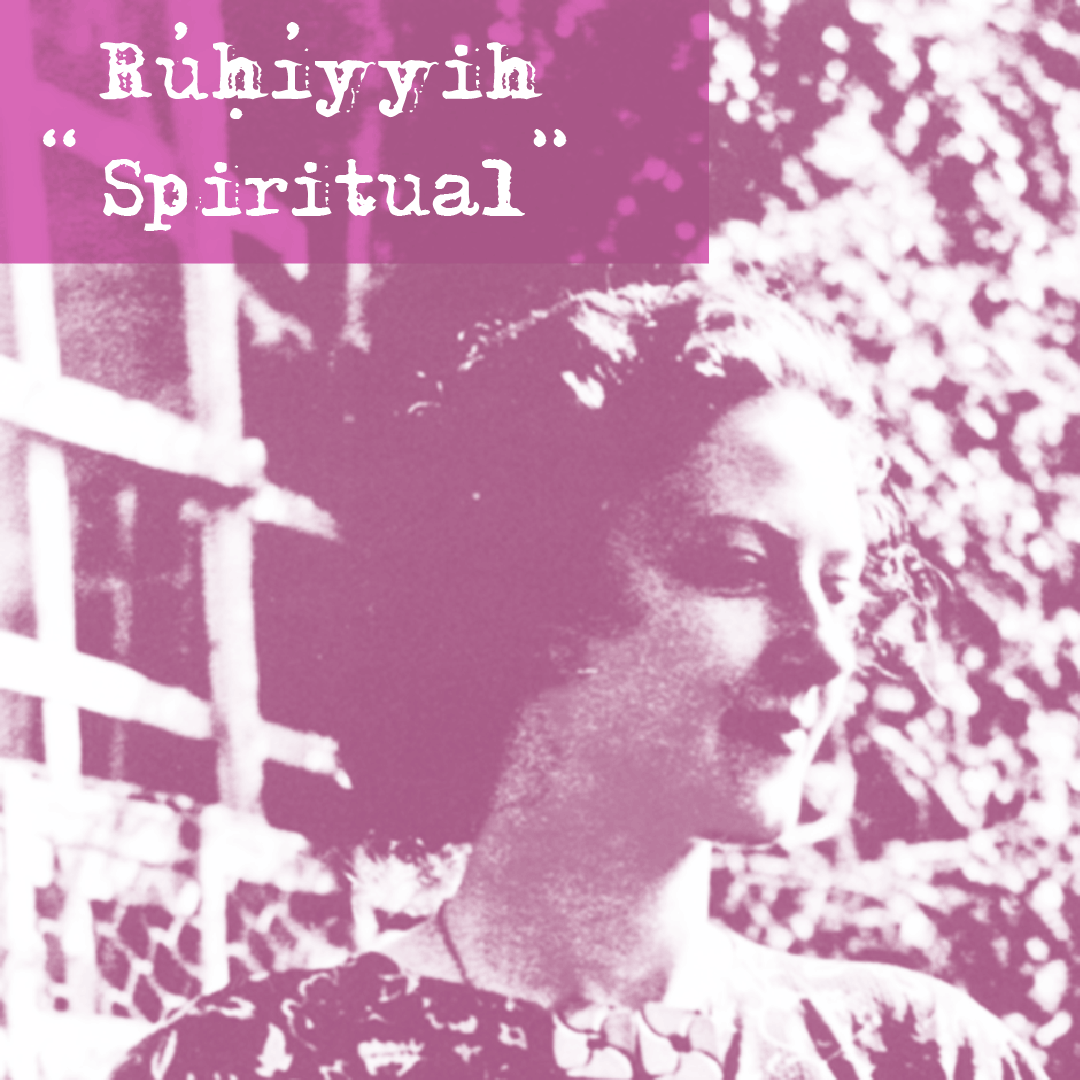

Mary Maxwell in Green Acre in 1934, at the age of 24. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

After leaving Haifa in 1924, young Mary Maxwell had blossomed into an enkindled, active, and very talented servant of the Faith.

She had a natural ability for writing, and developed her talents by writing books, articles, plays, and poetry. Her dearest wish and highest hope were to one day become an author. Mary was also a born speaker and, with the encouragement of Shoghi Effendi, she developed her eloquence by lecturing. Mary’s ardent, youthful enthusiasm informed the lectures she gave on the Heroic Age of the Faith in Montreal, Green Acre, Louhelen, and Esslingen, Germany.

From Haifa, Shoghi Effendi closely followed the development and spiritual training of this remarkable young woman, and noted her progress in service to Bahá'u'lláh with keen interest. Shoghi Effendi wrote to her mother, May Maxwell enclosing precious advice for Mary’s personal and spiritual growth:

I feel that she should, while pursuing her studies, devote her energies to an intensive study of, & vigorous service to, the Cause, of which I hope & trust she will grow to become a brilliant and universally honoured exponent. I am sure, far from feeling disappointed or hurt at my suggestion, she will redouble in her activities & efforts to approach & attain the high standard destined for her by the beloved Master. Your plan of travelling with her throughout Canada in the service of the Cause is a splendid one & highly opportune. Kindly assure her & her dear father of my best wishes & prayers for their happiness welfare & success.

Over the next 15 years, Mary continued to develop a myriad of rare and precious skills that transformed her into what she would become after her marriage to Shoghi Effendi: a perfect instrument of service in the hands of her beloved Guardian.

Mary studied The Dawn-Breakers intensely, and wrote a marvelous article—which was covered in this chronology in a story in 1932—which was published in The Bahá'í World Volume 5 called The Re-florescence of Historical Romance in Nabíl.

In 1934 Mary Maxwell gave talks on The Dawn-Breakers at the Bahá’í summer schools in Green Acre and Louhelen. In this picture she is taking part in the pageant The Gate of Dawn, presented by the newly-formed Green Acre Committee for Plays and Pageants; this is the last scene in which, dressed as an angel, she recites the farewell message of the Báb. Source: The Maxwells of Montreal: Middle Years 1923-1937 Late Years 1937-1952. Violette Nakhjavani, Kindle Edition, Location 4203.

Bahá’ís at the Esslingen Summer School, Germany, 1936. May Maxwell and Marion Jack are standing on either side of the Greatest Name; seated on the ground in the front row are Mary Maxwell and her cousin Jeanne Bolles. Source: The Maxwells of Montreal: Middle Years 1923-1937 Late Years 1937-1952. Violette Nakhjavani, Kindle Edition, Location 4857.

May and William Sutherland Maxwell left Montreal and arrived in Europe in September 1935, and William Sutherland Maxwell left a few weeks later to return to work. Mary had sailed one month before her parents and had traveled to Esslingen, participated in the Bahá'í Summer School, and fallen in love with the country.

Between October 1935 and January 1936, Mary Maxwell and Shoghi Effendi exchanged letters constantly about her service to the Faith. The letters are passionate with love for Bahá'u'lláh, service, the destiny of Germany, questions and requests for prayers from Mary, and, on the part of the Guardian, guidance, advice, and suggestions. One feels through this exchange of letters the bond already binding Mary Maxwell and Shoghi Effendi, not a bond of romantic love, but a stronger, more unbreakable bond: dedication to the Covenant of Bahá'u'lláh, and passion for service.

Sometime in November 1935, Mary received a long letter dated 28 October 1935 on behalf of the Guardian’s secretary, warmly encouraging her in her efforts and responding to her 3 October letter with precious advice regarding learning German, keeping Germany as her focus for teaching, and putting the emphasis on consolidation:

Shoghi Effendi feels very much encouraged & gratified to realize that you are developing great interest in the Cause in Germany. Your visit to Esslingen, Stuttgart & various other Bahá’í centres seems to have left a strong impression upon you. Germany, indeed, stands to-day as the largest, most active & promising Bahá’í community in Europe. And the Guardian cherishes the highest hopes for its future, and feels convinced that, as clearly promised by the Master, it will gradually develop into one, if not the most, of the leading Bahá’í countries throughout the world. In view of that, he would certainly encourage you to study German & to get in touch with the German believers, so that you may get well prepared for teaching the Cause in Germany in the near future. He would even advise you to make that country the main field of your teaching work in Europe. For although general conditions in Germany are, at present, not very favourable to the expansion of the Movement, yet the future of the Cause there seems to be very bright, & rich in all sorts of possibilities. Now, the main task facing the German friends is the consolidation of the Administration. The era of intensive teaching has not yet dawned upon them. But once their communities are fully organized internally, it will then be easy for them to effectively teach the Cause to the outside public.

Shoghi Effendi added a few words in his own handwriting in the postscript of this 28 October letter, delighted at Mary’s praiseworthy work and showering her with encouragement:

Dear & valued co-worker: I have, in my recent cable addressed to your dear & distinguished mother, expressed my delight in learning of the progress you have made in learning German & of the efforts you are exerting to teach the Cause in Germany. I have also expressed my full approval of the inclination you feel to work for our beloved Faith in that land, & I cannot but feel that your collaboration with the German believers will reinforce the foundation of your future international services & will serve to ennoble the work you are destined to achieve in the days to come. I will be soon writing to your mother, & I trust that the cable, assuring her of my prayers for her brother’s family has reached her & relieved her anxieties.

Conference of the North German Bahá’í centres, at Diedrichshagan, a village near Rostock, Spring of 1936. Mary Maxwell is standing 5th from left. Source: The Maxwells of Montreal: Middle Years 1923-1937 Late Years 1937-1952. Violette Nakhjavani, Kindle Edition, Location 4751.

Writing on the first day of Ridván, 21 April 1936, from the Hotel Nordland in Rostock— the largest coastal and most important port city in East Germany—Mary submitted a lengthy report to the Guardian about the difficulties in prewar Europe, particularly racial prejudice and fear—one senses the imminent cataclysm of war in her letter. Tensions were high in Germany:

My beloved Shoghi Effendi, One of the obvious problems here is that of the combinations of race prejudice, fearsomeness, intense championing of the Policy & Government, at present. When a Bahá’í with Jewish blood hears one without it rail against this part of his racial antecedents, it does not help the love or happiness of the community spirit…I must say truthfully I have found more fear of almost any kind of free action among the Bahá’ís as among the other many German friends I have contacted. They say their fear of really getting busy and doing something is so that they will not jeopardize the Cause in general and I can well understand this standpoint, but even so I feel they are much more timid than is warranted from the builders of a new and Divine Order with all the power that lies behind it to be drawn upon! In other words I have no sympathy with a scared Bahá’í…I mean in little ways such as teaching an individual or saying ‘what would we do if a Jew became a Bahá’í?’ (this in places where there are none!)…I am trying to write a book in German with the help of a wonderful boy I have met, only 19 years old. My bad German he puts into good German! Please, if it be within the Grace of God, pray I may succeed…I visited and read a speech in German on the Administration, in Dresden, Leipzig, Berlin, Rostock, Warnemünde and Hamburg (one night in each place) then was too tired to go on and stayed over a month in Hamburg to try and help them get going. I will stay a week or two here again in Rostock–Warnemünde.

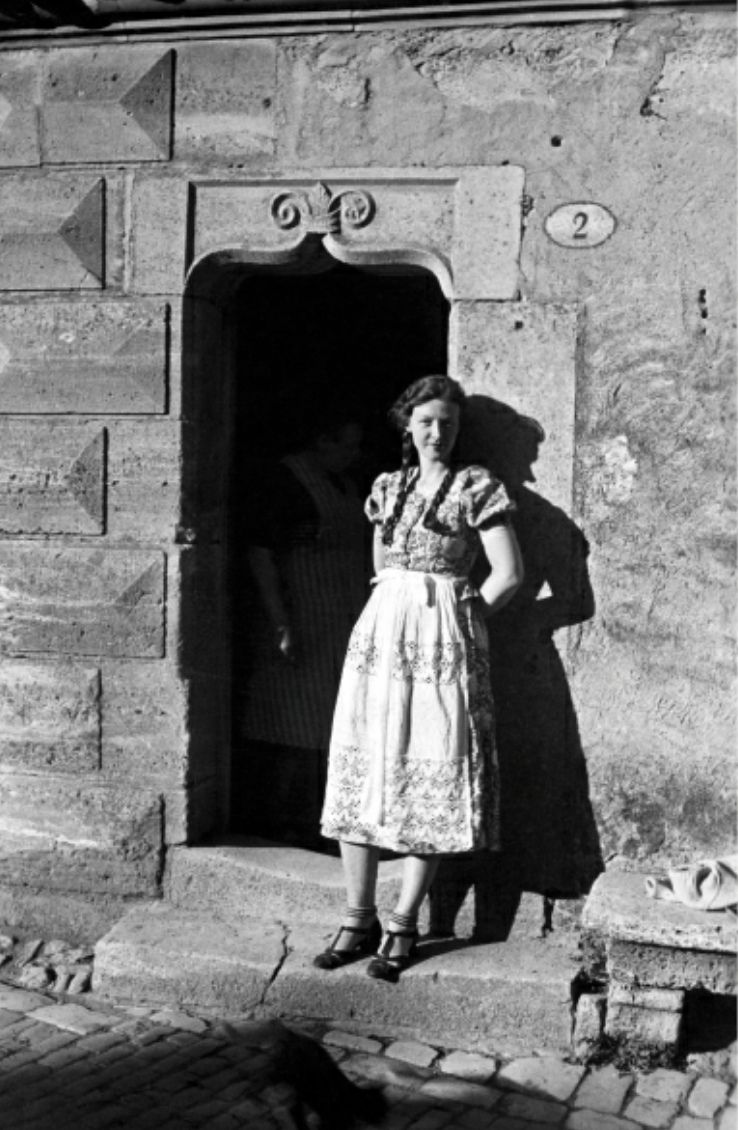

Two cousins: Mary Maxwell (on the right) and Jeanne Bolles (on the left) wearing traditional German dress, the dirndl, Stuttgart, 1936. Source: The Maxwells of Montreal: Middle Years 1923-1937 Late Years 1937-1952. Violette Nakhjavani, Kindle Edition, Location 4903.

Soon after, Mary Maxwell received a letter, written on behalf of the Guardian, dated 1 May 1936, expressing his gratitude at her precious service:

But, as you rightly state, there is great need for suitable literature on the Cause that would appeal to the great public outside, & particularly to the modern youth. In this connection the Guardian feels he must express his deep gratification & also his grateful thanks & appreciation to you for your efforts for the preparation of an introductory book on the Cause in German…

And in Shoghi Effendi’s handwriting, a postscript filled with admiration, hope, gratitude and, as usual, the Guardian’s own very special brand of encouragement that set the hearts of all Bahá'ís, and especially Mary’s, on fire with love for Bahá'u'lláh:

Dear & valued co-worker: I am delighted with your accomplishments. My heart is filled with hope & gratitude. I have sent you a cable of appreciation which I trust you have received. Your recent services will never be forgotten. Rest assured & be happy. Your true brother, Shoghi.

Mary Maxwell in Rothenburg, Germany, circa 1936. Source: The Maxwells of Montreal: Middle Years 1923-1937 Late Years 1937-1952. Violette Nakhjavani, Kindle Edition, Location 4705.

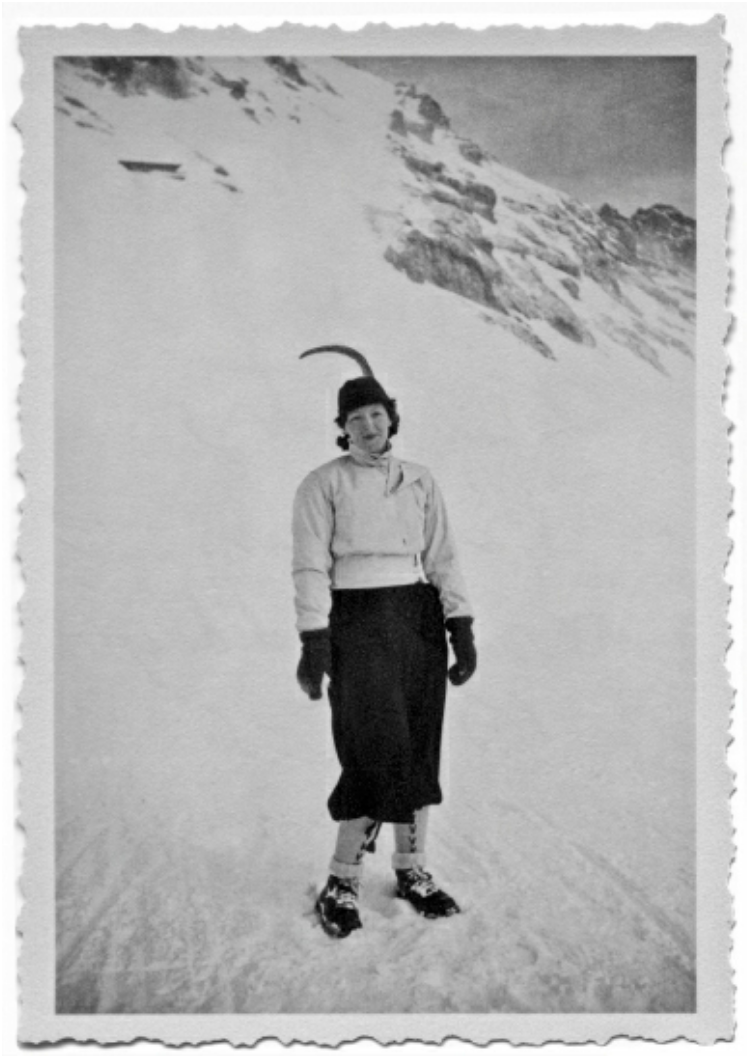

PHOTOGRAPH: 1935 – 1936: Mary Maxwell skiing in Bavaria

Photo of Trieste. Photo by Joshua Rondeau on Unsplash.

Mary and May Maxwell had been teaching in Germany for a year, and had received at least 2 invitations for pilgrimage on the part of the Guardian, if not more. Shoghi Effendi wrote to invite May and Mary Maxwell on pilgrimage on 28 October 1935, and again in January 1936. By 29 May 1936, May and Mary wanted to come, but the Guardian was too exhausted. Finally, seven months later, the Guardian returned from Switzerland fully revitalized and sent May and Mary a nine-word telegram on 8 December 1936:

Heartily approve your decision sail from Trieste love both.

They had absolutely no inkling of what was about to happen, something that would change the Maxwell family’s life and destiny forever.

An aerial photograph of Haifa taken on 20 June 1937. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

May and Mary Maxwell sailed into Haifa on 12 January 1937, after traveling by train from Hamburg to Italy and leaving by ship on 3 January. They signed their names in the Pilgrim Book as May Bolles Maxwell and Mary Sutherland Maxwell.

This would be May Maxwell’s fifth and last pilgrimage. Her first, as a young woman of 29 was in 1898, she had returned with her husband William Sutherland Maxwell in 1909, and her third and fourth pilgrimages were in 1923 and 1924, on either end of the Guardian’s Switzerland retreat in the summer of 1923.

They spoke at length to the Guardian about their activities around Europe, and Shoghi Effendi was very happy, and encouraged them. During the first ten days of their pilgrimage, the Guardian became more acquainted with Mary Maxwell’s talents. Mary was 27 years old, stunningly beautiful, extraordinarily witty and deeply intelligent. She was following in the footsteps of her mother as a deepened, talented teacher of the Cause, a powerful speaker, and to add to all her talents, she was a deeply gifted writer.

May Maxwell noticed that the more Shoghi Effendi came to know Mary Maxwell, the more he asked about William Sutherland Maxwell, and asked May Maxwell to invite him. The Guardian had long been impressed with Mary Maxwell’s character and her devotion to the Faith. Four months before she came for her second pilgrimage, Shoghi Effendi had written a letter to May Maxwell thanking her for a generous donation, expressing the wish that “Mary fulfil your fondest hopes and become in time a most radiant light in the firmament of the Cause,” and he had ended the letter sending his love to May, Sutherland Maxwell, and Mary, for whom, he said “I have the greatest admiration and affection.”

May and Mary spent a heavenly night in Bahjí on 22 January, ten days after their arrival, which May described in a letter written on the stationery of Bahjí as “an eternity of beauty, wonder and love.”

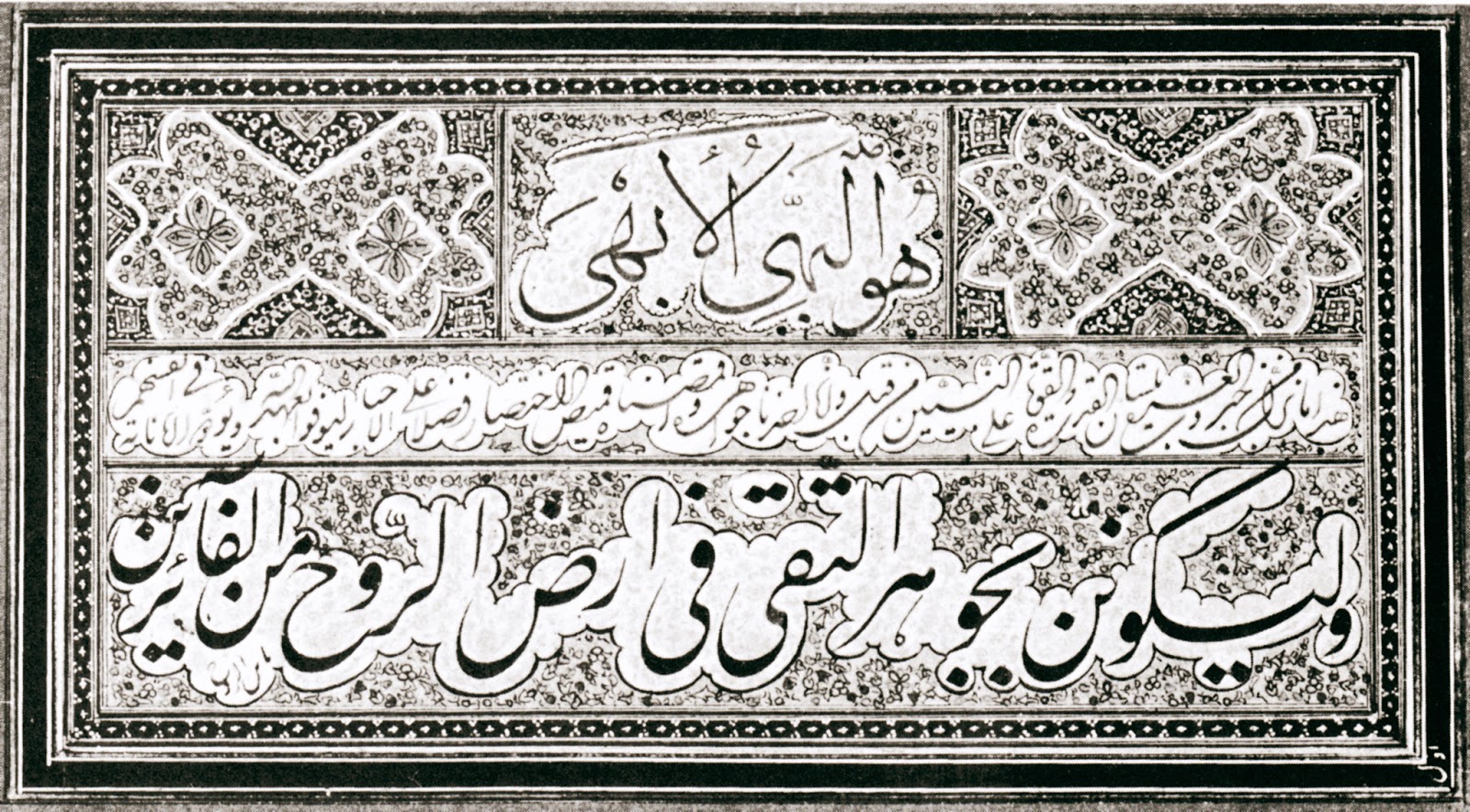

The first verse of Bahá'u'lláh’s Hidden Words in Arabic arranged and written in three different styles of calligraphy by Mishkín-Qalam, as in the story below where Shoghi Effendi gives three types of calligraphy to Mary Maxwell for practice. Originally published in The Baha’i World 1968-1973. Source: Bahá'í Points of Interest.

A few weeks after Mary’s arrival in the Holy Land, Shoghi Effendi, in the course of unforgettable evenings, when he gave her a set of reed pens, black ink, and special mulberry papers and gently tutored her in Persian calligraphy. Shoghi Effendi gave Mary a set of cards to copy from: these notes— the Hidden Words of Bahá’u’lláh in three different calligraphy styles—had been calligraphied by Mishkín-Qalam himself. Rúḥíyyih Khánum kept her calligraphy exercise books from this lovely period for the rest of her life.

The Guardian also gave special attention to Mary’s general training and education, showing her a deep kindness, and understanding.

May Maxwell, for her part, gradually, gently learned that a marriage proposal was in the workings, mainly through a confidential conversation which Shoghi Effendi’s mother had with her, in true eastern fashion.

“Your presence here” The Maxwell home—now a Bahá'í Shrine—in Montreal, Canada at 1548 Pine Avenue. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá stayed in this home during his six-day visit to Montréal. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

Then, on 26 February 1937, May Maxwell sent her husband William Sutherland Maxwell in Montreal a momentous cable which was delivered to their home on Pine Avenue:

Your presence here by march twenty first essential in connection Mary’s future happiness great destiny complete secrecy absolutely essential mention to no one if necessary use pretext visit to Randolph you can sail Berengaria on March third and catch Triestino March tenth Trieste arriving Haifa fifteenth make Florida money available cable reply our devoted love May.

The next day, on 27 February 1937, Mary sent her father an extraordinary telegram, asking for consent:

Daddy – Ask your consent for my marriage confirm my great happiness absolute secrecy required until after wedding and official announcement longing for your arrival bring originals Masters tablets please cable consent immediately Your devoted loving Mary

William Sutherland Maxwell replied the very same day he received her telegram:

Surprised and overjoyed consent granted deepest love and devotion Shoghi mother you. leave Berengaria Wednesday go via brindisi arrive fifteenth Daddy.

William Sutherland Maxwell boarded the Santa Maria del Casale in Brindisi on 11 March and arrived in the port of Haifa on 15 March 1937, on the lunar date of the Birthday of Bahá’u’lláh.

Background image: Shrine of Bahá’u’lláh, Mansion of Bahjí and surrounding area, 1930s. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

That same day, 15 March 1937, May wrote a very touching note to Shoghi Effendi on the stationery of the Pilgrim House:

Beloved Guardian,

Today I realize more profoundly than ever in my life the deep meaning of the Master’s Words to me in Montreal—"God has perfected all His bounties in you” and this, despite my utter unworthiness.

Now it is you, who take my dear husband to Bahjí, and my thankfulness is overflowing. May I humbly beg, on this blessed day your prayers for all my near and dear ones in the seen and in the unseen worlds; for all those with whom my “heart is vitally connected,” for whom the Master made me such wonderful promises…

With deepest love and humble devotion, I am yours, May M.

Windsor station in Montreal, around 1900. This is the train station at which 'Abdu'l-Bahá arrived at 8:40 p.m. on Friday, on 30 August 1912, where He was welcomed with two carriages by William Sutherland Maxwell and brought to the Maxwell home on Pine Street, where May and a 2-year-old Mary Maxwell were waiting for Him. This is the station that we chose to illustrate Shoghi Effendi’s dream about a train station in Montreal. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

At some point before his wedding, Shoghi Effendi had a dream, which confirmed to him that Mary Maxwell was his future wife.

He dreamt that he was in a large ship sailing for North America. The Captain of the ship was 'Abdu'l-Bahá. They reached the shores of America, then boarded a train, and when the train stopped at a station, the Guardian looked at the sign.

It read “Montreal.”

Mary Maxwell (Rúḥíyyih Khánum) in the garden of the Western Bahá'í Pilgrim House in Haifa, shortly before her marriage to Shoghi Effendi, 1937. Source: Bahá'í Points of Interest.

Mary Maxwell had revered, almost worshipped the Guardian of the Faith, since she had come on her second pilgrimage in 1926, at the age of 15, and shared the same devotion to Shoghi Effendi as her mother did. She had fully and completely given her heart and soul, her entire being to her Guardian.

Mary Maxwell herself knew nothing about her upcoming marriage until a week or two later, when one day, as the mimosa trees were in full bloom with their miniature golden suns, Shoghi Effendi’s younger sister Mihrangíz told Mary:

Shoghi Effendi wants to see you in his room.

The Guardian always wore a simple Bahá'í ring in the shape of a heart which the Greatest Holy Leaf had given him, engraved with the symbol of the Greatest Name. On the afternoon when he chose Mary Maxwell to be his wife, he took the precious, meaningful ring off his ring finger, and placed it on the same ring finger of Mary Maxwell’s hand telling her:

Now no one must see that you are wearing it.

It would be Shoghi Effendi himself who would sustain Mary Maxwell as she received the most overwhelming news of her life: that she, Mary Sutherland Maxwell, was to become the wife of the Guardian. The 15 minutes of their engagement was the only time they were alone together before their marriage on 24 March. Mary Maxwell kept the ring hidden inside her blouse, hanging around her neck from a chain.

After their marriage, Rúḥíyyih Khánum had another copy of the exact same ring made for the beloved Guardian. Both Rúḥíyyih Khánum and Shoghi Effendi were buried with this ring on their fingers.

Views of the outer Shrine of Bahá’u’lláh at Bahjí. The door pictured on the photograph at the right of the imag is the inner sanctum of the Shrine. This photograph was originally published in The Bahá’í World Volume 3, page 11. Source: Bahaimedia.

As we have learned to get to know Shoghi Effendi, it will come as no surprise that his wedding was utterly simple, profoundly spiritual, and perfect in its beauty and simplicity, truly a wedding to admire, and an example to aspire to instead of the complications of the usual eastern and western convoluted dos, weighed down by the expensive trappings of tradition.

Speaking of this most important aspect of the Guardian’s wedding, Rúḥíyyih Khánum later stated, drawing a parallel between the Guardian’s own simple wedding and 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s equally simple wedding 64 years before:

Surely the simplicity of the marriage of Shoghi Effendi—reminiscent of the simplicity of 'Abdu'l-Bahá's own marriage in the prison-city of Akká—should provide a thought-provoking example to the Bahá'ís everywhere.

No one knew about the Guardian’s upcoming wedding.

The only people who were informed were the Guardian’s parents, Mary Maxwell’s parents, and three of Shoghi Effendi’s siblings—one brother and two sisters.

The Guardian strongly urged everyone to keep the wedding a secret, knowing from his past painful experiences how much trouble major events in the Faith could stir up.

Because essentially no one was informed about the wedding, it was a surprise to the servants and the local Bahá'ís when they saw Shoghi Effendi drive away, alone with Rúḥíyyih Khánum in the car. They arrived at the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh in Bahjí on the afternoon of 24 March 1937.

The heart of the Guardian had drawn him to the most Sacred Spot on the planet at this important moment in his personal life.

“This is the reality of marriage.” Photograph of the inmost Shrine of Bahá’u’lláh at Bahjí, where the story below takes place. This photograph was originally published in The Bahá’í World Volume 3, page 5. Source: Bahaimedia.

When they arrived at Bahjí, Shoghi Effendi asked Mary Maxwell to give him his ring—the Greatest Holy Leaf’s ring he had given her when he chose her to be his wife—and which she had been wearing concealed around her neck since that day.

Shoghi Effendi placed the ring on Mary Maxwell’s ring-finger, the same finger on which he had always worn the ring himself.

This was the only gesture he made.

Shoghi Effendi entered the inner Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh, beneath the floor of which Bahá'u'lláh’s Sacred Remains are interred, and gathered up in a handkerchief all the dried petals and flowers that the custodian of the Shrine used to take from the threshold and place in a silver receptacle at the feet of Bahá'u'lláh.

The Guardian and Rúḥíyyih Khánum were alone in the inner sanctuary in the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh. Shoghi Effendi chanted two prayers, and he later told Rúḥíyyih Khánum that that was the reality of the marriage. Nothing else apart from the prayers was said, everything was silent.

When they returned to Haifa, the Guardian’s. mother took Shoghi Effendi and Rúḥíyyih Khánum into the room of the Greatest Holy Leaf.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum was dressed very simply, all in black—a black skirt suit, black shoes, a black bag, and a small black turb—except for a white lace blouse.

Just as Fáṭimih Khánum had been given a new name by Bahá'u'lláh shortly before her marriage to 'Abdu'l-Bahá, the Guardian bestowed a new name on Mary Maxwell the day they were married.

From this moment on, Mary Maxwell would be known as Rúhíyyih Khánum. Rúhíyyih meaning “spiritual” and Khánum indicating that she was a Lady.

House of the Master. Source: Bahaimedia.

To Rúḥíyyih Khánum, the fact that Shoghi Effendi chose to get married in the Greatest Holy Leaf’s own bedroom was the most revealing gesture of the intense love he had for Bahíyyih Khánum, his Great-Aunt who had passed away just 5 years ago.

Everything in the Greatest Holy Leaf’s room had been perfectly preserved, just as it was in her days.

As Rúḥíyyih Khánum and Shoghi Effendi stood beside her bed, hand in hand, they had the simple Bahá'í marriage ceremony, each repeating the marriage verse in Arabic:

First the verse pronounced by Shoghi Effendi:

inná kullun li'lláh ráḍún (We will all, verily, abide by the Will of God)

Then the verse pronounced by Rúḥíyyih Khánum:

inná kullun li'lláh ráḍíyát (We will all, verily, abide by the Will of God)

That was the marriage of the Guardian. As Rúḥíyyih Khánum beautifully stated:

There was no celebration, no flowers, no elaborate ceremony, no wedding dress, no reception.

To illustrate a story about a Persian wedding tradition, a 19th century Persian wedding scene portrayed in a Qajar Persian pottery tile. Source: © Anavian Gallery, used with permission.

After the recital of the marriage vows in the room of the Greatest Holy Leaf, Ḍíyá‘íyyih Khánum, the mother of Shoghi Effendi, placed Rúḥíyyih Khánum’s hand in the hand of her son, according to the old Persian tradition of “dast be dast.”

In traditional Persian culture, only a husband and wife could hold hands. When Ḍíyá‘íyyih Khánum placed Rúḥíyyih Khánum’s hand in Shoghi Effendi’s, it was a solemn act in Persian culture, signifying that they were now husband and wife.

The symbolism of “dast be dast” is that the husband wife’s hands were now joined together forever, for the rest of their lives and under the protection of God.

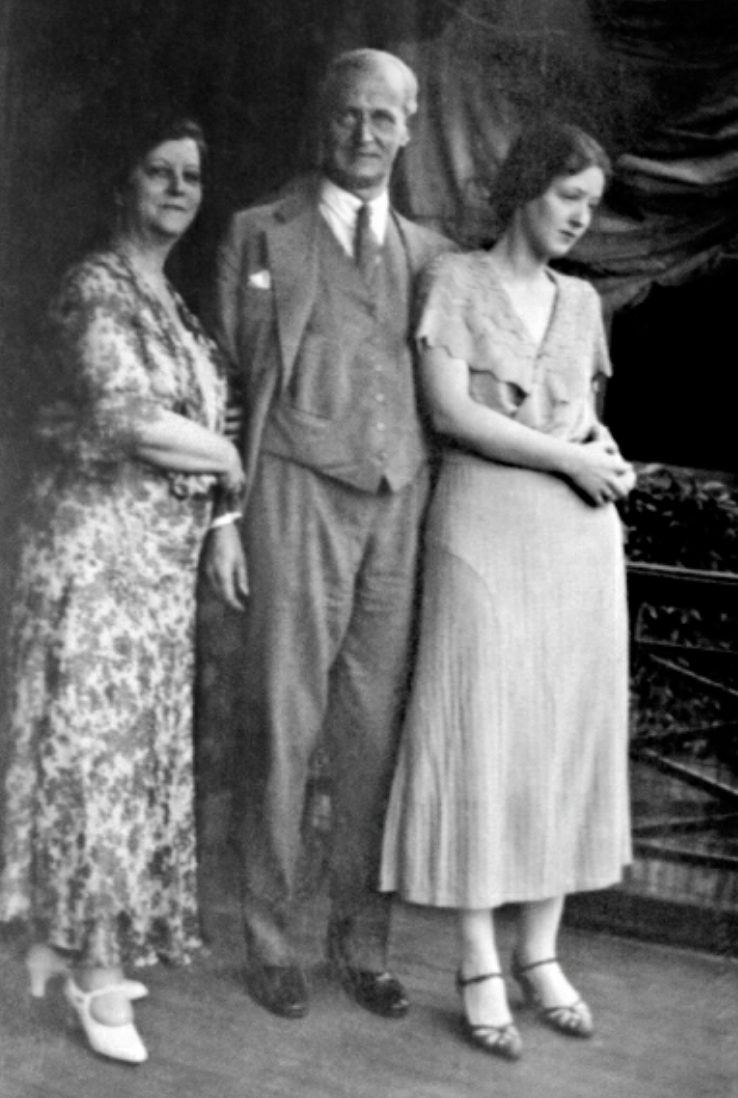

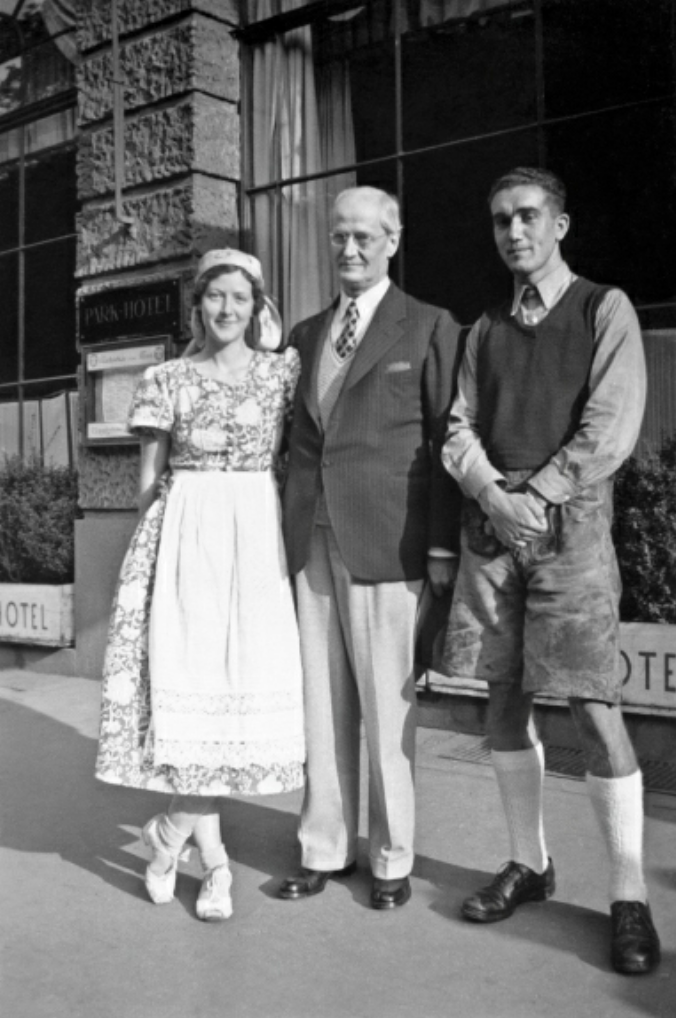

The only known photograph of the three Maxwells of Montreal: May, Sutherland Maxwell and Mary Maxwell. Source: The Maxwells of Montreal: Middle Years 1923-1937 Late Years 1937-1952. Violette Nakhjavani, Kindle Edition, Location 1651.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum recorded the historic event of her marriage in her father’s Daily Memorandum book – a beautiful album made of red and black leather with letters tooled in gold:

Mary Sutherland Maxwell, daughter of William Sutherland and May Ellis Maxwell was married to Shoghi Effendi, the First Guardian of the Bahá’í Faith, on March 24th, 1937 at Haifa, Palestine.

The same day as her wedding, Rúḥíyyih Khánum wrote this moving short letter to her parents, addressed “to Mother and Daddy” and written on the letterhead stationery of the Bahá’í Pilgrim House:

My dearest, dearest ones, On this most glorious day of my life how can I ever thank you both enough and express my love to you – for the life you gave me? For all your devotion to me; the example of your own happy marriage that gave me an ideal in life; the beauty of our home which has enriched my very soul.

From you both I have woven into me so many characteristics that I hope now will be of service to the Guardian and [the] Cause. Surely no child ever had two better, more loving parents than I! And as you have always been my pride and my dearests and my joy – so in my new life you will always continue to be!

Your own Faithful Mary

Shoghi Effendi would later refer to his wife Rúḥíyyih Khánum, as his “helpmate,” “shield” and “tireless collaborator in the arduous tasks I shoulder.”

The Western Pilgrim House at 4 Haparsim, across the street from Rúḥíyyih Khánum’s new home, the Master’s House, where they have dinner on the first night of their marriage. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

After the marriage ceremony, Rúḥíyyih Khánum and Shoghi Effendi exited the Greatest Holy Leaf’s room and both families greeted and embraced them. Later Shoghi Effendi and Rúḥíyyih Khánum, his new Canadian wife stopped by the Pilgrim House and were embraced by the pilgrims, utterly overwhelmed with joy.

May Maxwell dwelt on the spiritual honour and responsibility which this marriage had bestowed upon the Maxwell family and offered her prayers to Rúḥíyyih Khánum, begging Bahá'u'lláh to bestow on her daughter—now the Guardian’s wife—the strength of spirit to overcome all spiritual tests.

Shoghi Effendi’s parents signed their marriage certificate at this time, and afterwards, Shoghi Effendi returned to his work, and Rúḥíyyih Khánum went back to the western Pilgrim House with some of 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s family. Shoghi Effendi rejoined them at dinner time, when he showered his love and congratulations on William Sutherland and May Maxwell. During dinner, Fujita carried Rúḥíyyih Khánum’s suitcases to her new home with the Guardian, the house of 'Abdu'l-Bahá.

He took the handkerchief filled with precious flowers he had gathered earlier that day and gave them to May Maxwell, telling her he had brought them for her from the inner sanctum of the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh.

William Sutherland and May Maxwell signed the marriage certificate after dinner, and Shoghi Effendi and Rúḥíyyih Khánum crossed the streets to the House of the Master, where they sat for a while with the Guardian’s family before retiring to his two rooms—his apartment and his office—built for him with immense love by the Greatest Holy Leaf 15 years ago during the first months of his ministry.

Shortly after their marriage, while Rúḥíyyih Khánum’s parents were still in Haifa, Shoghi Effendi would tell May Maxwell over dinner one night that one of the reasons he had chosen her daughter Mary as his wife was because she was the daughter of May Maxwell.

A photograph of the House of the Master, Rúḥíyyih Khánum’s new home. Source: Bahá'í World News Service.

The first people to receive news of Shoghi Effendi and Rúḥíyyih Khánum Rabbání’s wedding were the family members.

The Maxwell and Bolles families received a cable from William Sutherland Maxwell to his sister, Amelia Maxwell Hutchison on the day of the wedding, 24 March 1937:

Shoghi Effendi married Mary Wednesday notify family. Love, Willie.

May Maxwell sent two cables on the same day to the Bolles in Connecticut and Washington with the same message:

Beloved Guardian married Mary Wednesday new name Rúḥíyyih Khánum. All our love.

Four days later, on 28 March 1937, Libbie Maxwell, William Sutherland Maxwell’s brother’s widow, sent a reply on behalf of the entire Maxwell family:

Loving congratulations to all. Libbie and family.

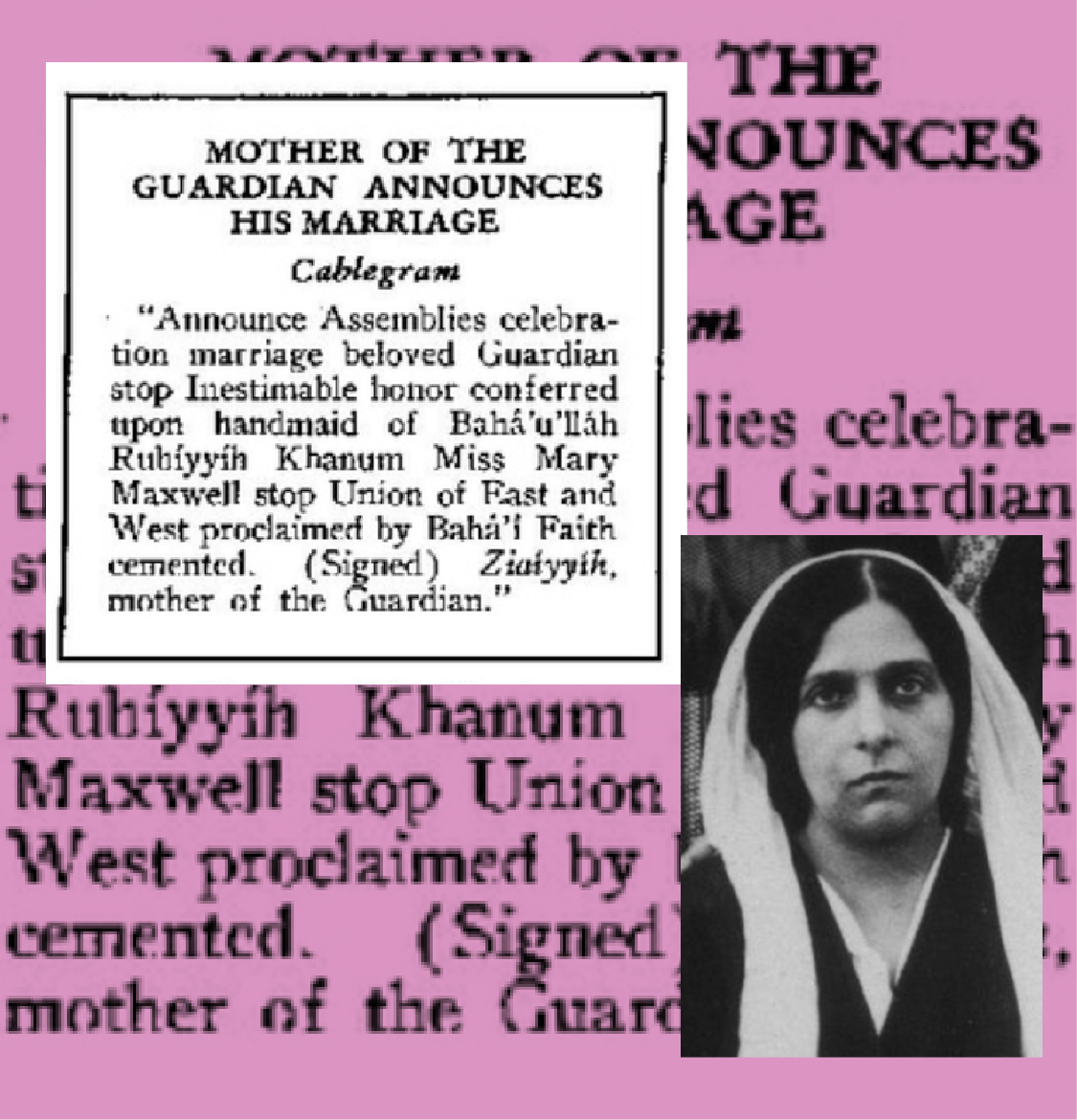

Publication of the official announcement by Ḍíyá‘íyyih Khánum—the mother of Shoghi Effendi—of the Guardian’s marriage in Bahá'í News Number 107 (April 1937). Photograph of Ḍíyá‘íyyih Khánum at a younger age. Source: Bahaipedia.

Three days after the wedding had taken place, on 27 March 1937, the Guardian informed the Bahá'í world of the happy news.

The first to be informed was the National Spiritual Assembly of the United States and Canada in a message written and sent by the Guardian himself but in which, out of propriety, he had signed his mother’s name—Ḍíyá‘íyyih Khánum:

Announce Assemblies celebration marriage beloved Guardian. inestimable honour conferred upon handmaid of Bahá’u’lláh Rúḥíyyih Khánum Miss Mary Maxwell. Union East and West proclaimed by Bahá’í faith cemented

A very similar cable was sent to the Friends in Iran.

The Bahá'í world was electrified. Responses poured in immediately.

This long-awaited and dearly-cherished news, so long awaited, brought immense joy to the entire Bahá'í world, to individuals and institutions alike and loving congratulations began flooding into Haifa from all parts of the world, carried by ‘Alí-Aṣghar Qazvíní.

The National Spiritual Assembly of the United States and Canada responded:

Assemblies will rejoice your heart stirring announcement beseech divine blessings.

Shoghi Effendi responded:

Joyously acclaim historic event so auspiciously uniting in eternal bond destiny East and West.

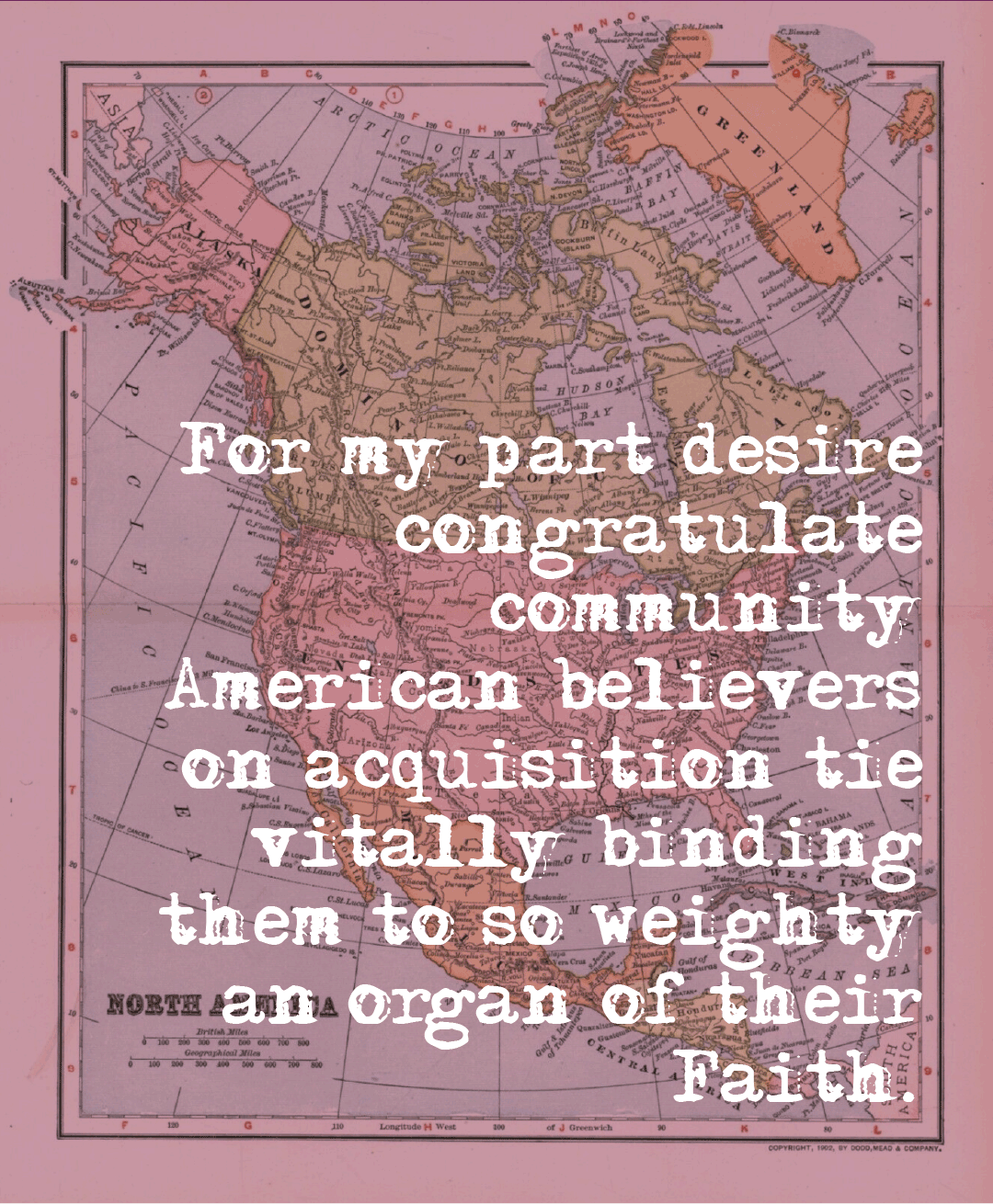

Three days later, on 30 March 1937, the Guardian sent a longer message to the National Spiritual Assembly of the United States and Canada, emphasizing this most important point of the direct association of East and West in his own marriage:

Deeply moved your message. Institution Guardianship, head cornerstone Administrative Order Cause Bahá'u'lláh, already ennobled through its organic connection with Persons of Twin Founders Bahá'í Faith, is now further reinforced through direct association with West and particularly with American believers, whose spiritual destiny is to usher in World Order of Bahá'u'lláh. For my part desire congratulate community American believers on acquisition tie vitally binding them to so weighty an organ of their Faith.

Shoghi Effendi most certainly did NOT respond to each message in this way.

His mostly universal answer was an expression of loving appreciation for their congratulations, but deeply attuned to the quality and the sincerity of the sender.

For example, when an individual the Guardian neither liked nor trusted cabled his congratulations, the Guardian did not express appreciation but rather responded:

Praying for you Holy Shrines.

The Bahá'ís of ‘Ishqábád sent their congratulations and Shoghi Effendi replied through an intermediary:

Kindly wire ‘Ishqábád Bahá'ís greatly value message praying continually protection.

John and Louise Bosch—two dedicated, faithful, and capable early believers from the time of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, who had been present during His Ascension—cabled the Guardian:

Illustrious nuptial thrilled the universe.

In his reply, Shoghi Effendi revealed how touched he was by so many expressions of love, including theirs, that were pouring in to Haifa:

Inexpressibly appreciate thrilling message, Deepest love.

The Guardian sent another particularly warm reply to the Antipodes:

Assure loved ones Australia New Zealand profound abiding appreciation.

The National Convention of the United States and Canada sent another congratulatory message to Shoghi Effendi on 29 April 1937:

American Convention gratefully celebrates dual gift, Master’s historic visit and consummation unique union East West. Pledges undying loyalty renewed vigor extend World Order throughout Americas and all lands. Profound dedicated felicitations.

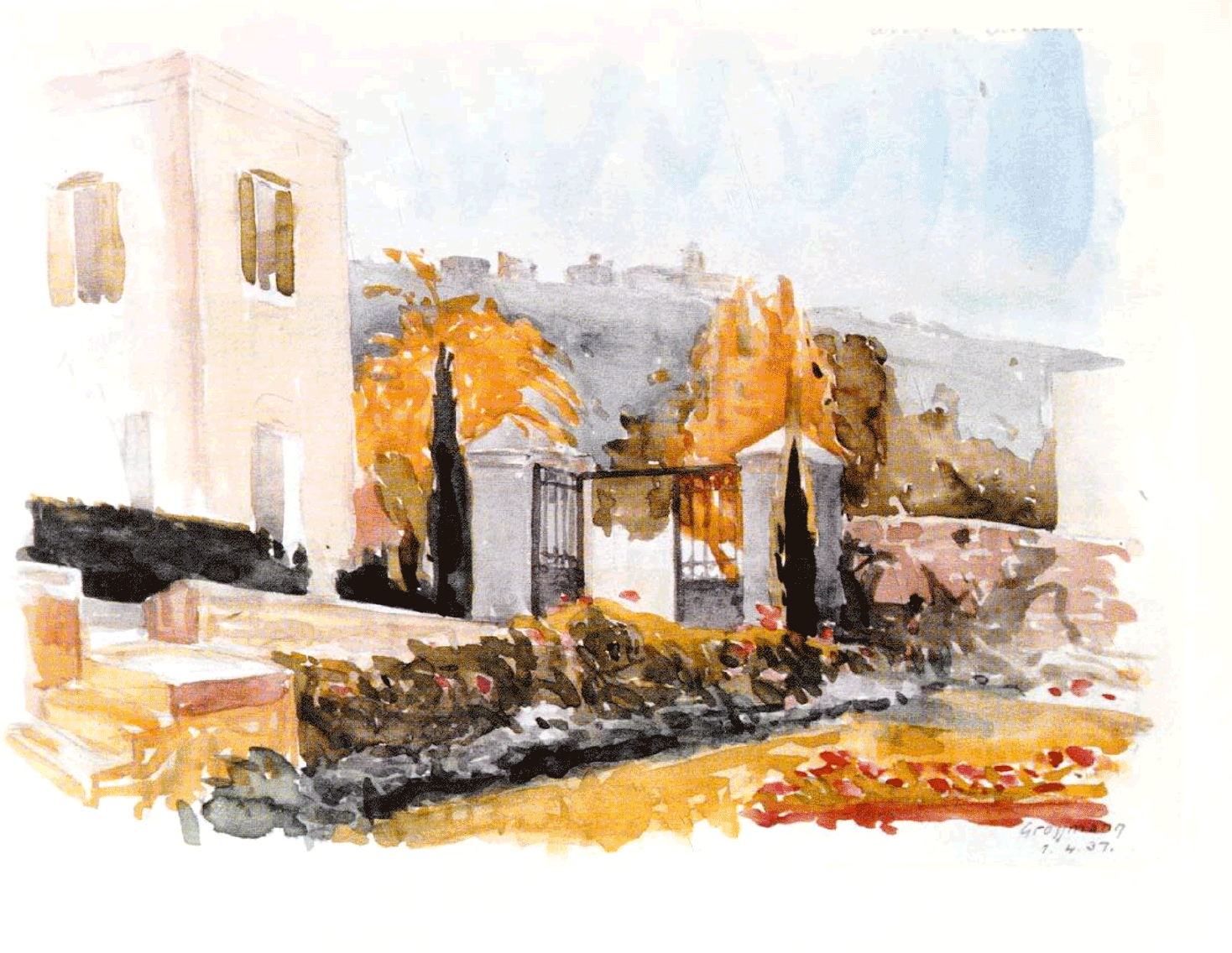

A watercolor of the garden of the House of the Master by Hermann Grossmann from his pilgrimage with his family in 1937. Source: Hermann Grossmann: Hand of the Cause of God: A Life for the Faith by Susanne Pfaff-Grossmann, between pages 52-53.

On 29 March, the Grossmann family, future Hand of the Cause Hermann, his wife Anna, their daughter Susanne, and Hermann’s sister Elsa Maria arrived in Haifa after a five-day sailing journey from Trieste, Italy.

They arrived 5 days after the marriage of Shoghi Effendi and Rúḥíyyih Khánum, and were the first pilgrims to do so. On the evening of their arrival, Shoghi Effendi joined the Grossmanns in the Western Pilgrim House in the company of his young and beautiful wife, Rúḥíyyih Khánum.

To the Grossmanns, Rúḥíyyih Khánum was like a close friend. They had become friends during her year of service in Germany, immediately before coming to the Holy Land, and Rúḥíyyih Khánum had bonded with the German Bahá'ís. She not only loved Germany and Germans and their mentality, but she wrote and spoke the language.

When the Grossmanns congratulated Shoghi Effendi on his recent marriage, the Guardian responded that he had wanted to unite East and West through his marriage and hoped that through Rúḥíyyih Khánum, the bond with the German Bahá'ís would grow especially strong.

The Guardian asked the Grossmanns whether they believed the German friends would be pleased to hear the news of his marriage.

In a letter in German Rúḥíyyih Khánum wrote to Anna and Elsa maria Grossmann after their pilgrimage, she said:

I have prayed for you all, for Germany and its people, in Bahá'u'lláh’s room. May God in His Holiness bless you all. It seems like a privilege to be ablet to say the prayers in German for you—for us!

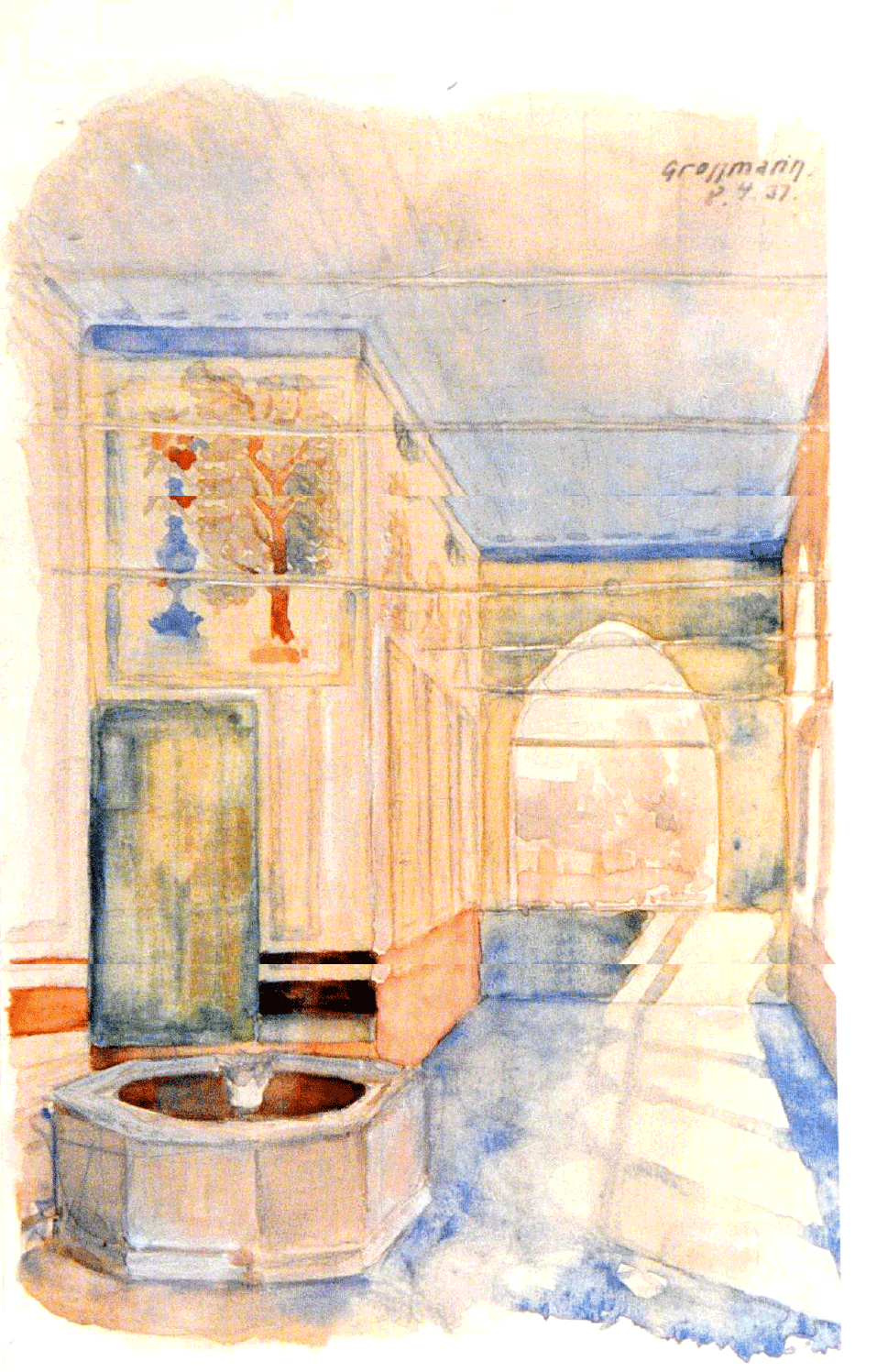

A watercolor of the mansion of Bahjí by Hermann Grossmann, from his pilgrimage in April 1937. Source: Hermann Grossmann: Hand of the Cause of God: A Life for the Faith by Susanne Pfaff-Grossmann, between pages 52-53.

Immediately after his previous masterpiece of translation—Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá'u'lláh—Shoghi Effendi began work on what Rúḥíyyih Khánum considers a companion volume to Gleanings, comparable in its great wealth of spiritual gems and in its content, the translation of a collection of 184 prayers and meditations revealed in Persian and Arabic by Bahá'u'lláh throughout His forty-year ministry.

The Guardian called this next bouquet of devotional utterances, “Prayers and Meditations by Bahá'u'lláh” and Rúḥíyyih Khánum poignantly described the work as “a diamond-mine of communion with God.”

This work of superlative translation, which would become a solace for Bahá'ís, demonstrates in the course of its 339 pages, the wealth of the Bahá'í Revelation in terms of prayers revealed by the Manifestation of God Himself, something that sets the Bahá'í Dispensation apart from all religions of the past.

In late 1936, Shoghi Effendi sent George Townshend the first installment of Prayers and Meditations for his usual editing and reviewing. George Townshend was so overwhelmed by the beauty of Shoghi Effendi’s translations and the exquisite uniqueness of the devotional Writings that he immediately wrote back to the Guardian:

It is very wonderful. Nothing like it in the world.

George Townshend had finished reviewing Prayers and Meditations 6 April 1937, and the book was published soon after.

Bayard Dodge, Shoghi Effendi’s former professor at the American University of Beirut, thanked him for the copy of Prayers and Meditations, showing how keenly he understood the work that had been involved in bringing the volume to light, with a compliment that must surely have touched the Guardian’s heart:

The translation of deep and poetic thoughts, such as those in the Prayers and Meditations, requires an enormous amount of hard work…I have told you before how much I marvel when I see the quality of English that you use.

Background image by Ravi Sharma on Unsplash.

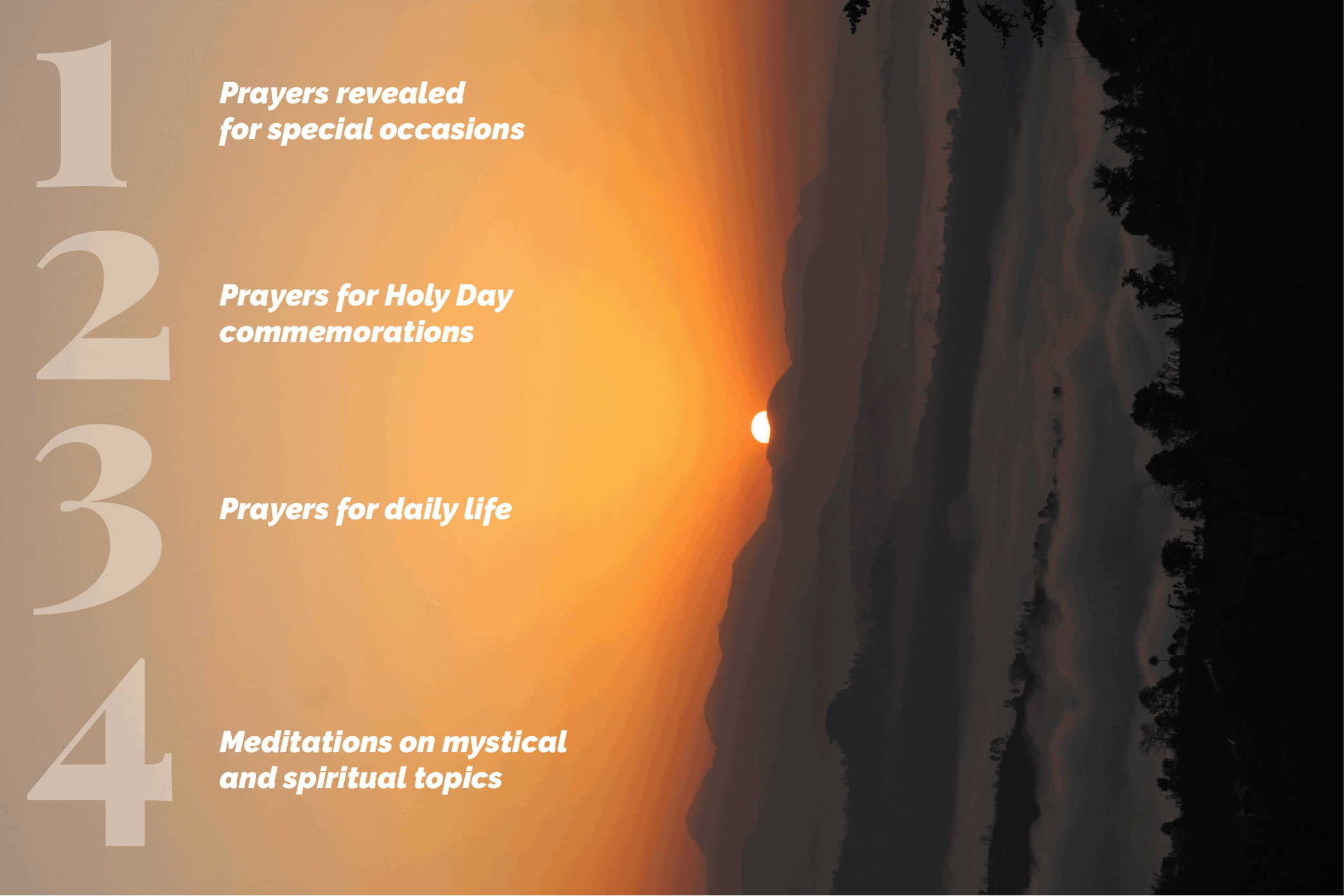

Rúḥíyyih Khánum suggested that the works in Prayers and Meditations by Bahá'u'lláh can be divided into four categories:

- Prayers revealed for special occasions—The Obligatory Prayers, the Prayer for the Dead, prayers for Riḍván and Naw-Rúz, for the Fast, and for the Intercalary Days.

- Prayers for Holy Day commemorations—such as the Tablet of Visitation.

- Prayers for daily life—morning and evening prayers, prayers for children, protection, traveling, thanksgiving, detachment, praise of and nearness to God, obedience, unity, steadfastness, assistance, teaching, victory of the Faith, forgiveness, spiritual progress, healing and the departed.

- Meditations on mystical and spiritual topics—God’s bountiful grace, Bahá'u'lláh’s sufferings, Bahá'u'lláh’s evanescence in the face of God’s Will. The longest of these meditations is 22 pages long, and the purpose of this category is to encourage the Bahá'ís to practice personal reflection.

After Shoghi Effendi published Prayers and Meditations by Bahá'u'lláh, stories emerged that people who had previously not had the capacity or perhaps even the desire to believe in God, found Faith in the exquisite pages of Prayers in and Meditations.

Below is a magnificent excerpt from Prayers and Meditations by Bahá'u'lláh, Selection No. VIII, which features a mystical conversation between Bahá'u'lláh and His blood on the subject of His sufferings:

Glorified be Thy name, O Lord my God! Thou beholdest my dwelling-place, and the prison into which I am cast, and the woes I suffer. By Thy might! No pen can recount them, nor can any tongue describe or number them. I know not, O my God, for what purpose Thou hast abandoned me to Thine adversaries. Thy glory beareth me witness! I sorrow not for the vexations I endure for love of Thee, nor feel perturbed by the calamities that overtake me in Thy path. My grief is rather because Thou delayest to fulfill what Thou hast determined in the Tablets of Thy Revelation, and ordained in the books of Thy decree and judgment.

My blood, at all times, addresseth me saying: “O Thou Who art the Image of the Most Merciful! How long will it be ere Thou riddest me of the captivity of this world, and deliverest me from the bondage of this life? Didst Thou not promise me that Thou shalt dye the earth with me, and sprinkle me on the faces of the inmates of Thy Paradise?” To this I make reply: “Be thou patient and quiet thyself. The things thou desirest can last but an hour. As to me, however, I quaff continually in the path of God the cup of His decree, and wish not that the ruling of His will should cease to operate, or that the woes I suffer for the sake of my Lord, the Most Exalted, the All-Glorious, should be ended. Seek thou my wish and forsake thine own. Thy bondage is not for my protection, but to enable me to sustain successive tribulations, and to prepare me for the trials that must needs repeatedly assail me. Perish that lover who discerneth between the pleasant and the poisonous in his love for his beloved! Be thou satisfied with what God hath destined for thee. He, verily, ruleth over thee as He willeth and pleaseth. No God is there but Him, the Inaccessible, the Most High.”

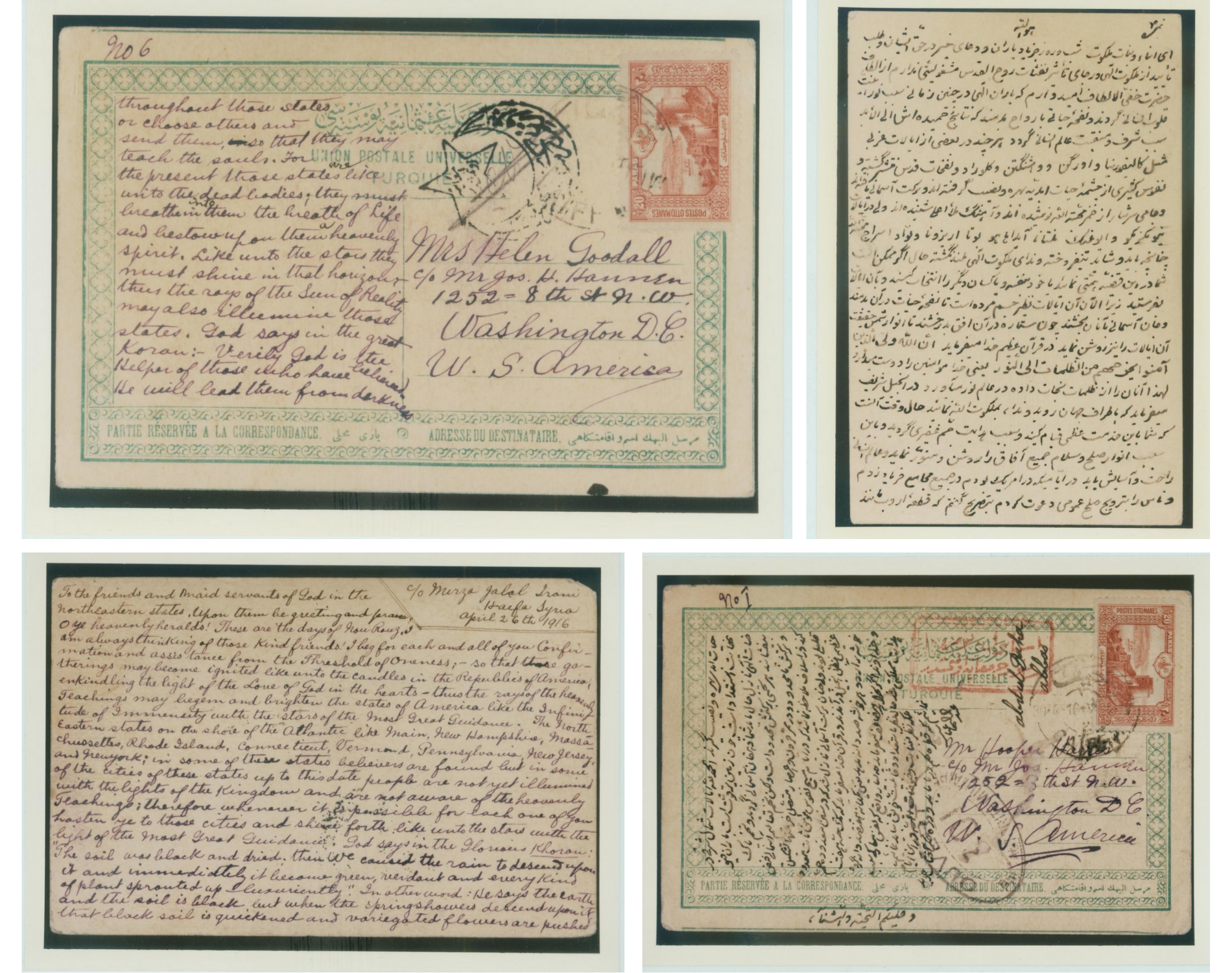

In 1937, Shoghi Effendi inaugurated the first epoch in the implementation of 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s Divine Plan, revealed in 14 Tablets addressed to the Bahá'ís of the United States and Canada in 1916 and 1917.

From the moment 'Abdu'l-Bahá passed away and he became the Guardian of the Faith, the sole aim and object of Shoghi Effendi’s life and work became to set into motion on the surface of the planet 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s grand design as outlined in the Tablets of the Divine Plan.

The first Tablets of the Divine Plan were sent to various individuals (Helen Goodall in the West, Joseph Hannen in the East) on series of postcards (sometimes up to eight) that contained the Persian and Arabic originals and the English translations. Top row: English front postcard and Persian back postcard for the first (1916) Tablet to the Western States. Bottom row: English back postcard and Persian front postcard for the first (1916) Tablet to the Northeastern States. National Bahá'í Archives of the United States. Source: Brent Poirier's website: Tablets of the Divine Plan.

The Tablets of the Divine Plan were a watershed moment: they were the very first teaching plan in Bahá'í history. It would be the Guardian who would make all Bahá'ís understand this, calling the Tablets of the Divine Plan the Bahá'í Faith’s charter for the spread of the Bahá'í Faith in every corner of the Planet.

This is the subject of the story that follows, the Guardian’s launch of the First Seven Year Plan, the first of his three Teaching Plans to prosecute 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s Tablets of the Divine Plan.

Shoghi Effendi did not just interpret translations, he interpreted Bahá'í and secular history, recasting events in the exact perfect light to allow all Bahá'ís to understand what had happened, what was currently unfolding in front of their eyes, and what would later occur.

The reason Shoghi Effendi had to wait 16 years after the start of his Guardianship before inaugurating the prosecution of 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s plan set forth in the Tablets of the Divine Plan was because the local and national institutions of the Bahá'í world were not yet mature enough.

Before spiritually conquering the planet, the Administrative Order of the Faith had to first be created, then evolved, and finally, it had to be perfected into an administrative machinery that could cohesively implement a Teaching Plan.

Only a solid Administrative Order could prosecute the Divine Plan envisioned by 'Abdu'l-Bahá and implemented by the Guardian in a systematic way and ensure ultimate victory.

It took 16 years until the Guardian was confident that the Bahá'í Administrative Order was mature enough to begin implementing the divine counsels in 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s Tablets of the Divine Plan.

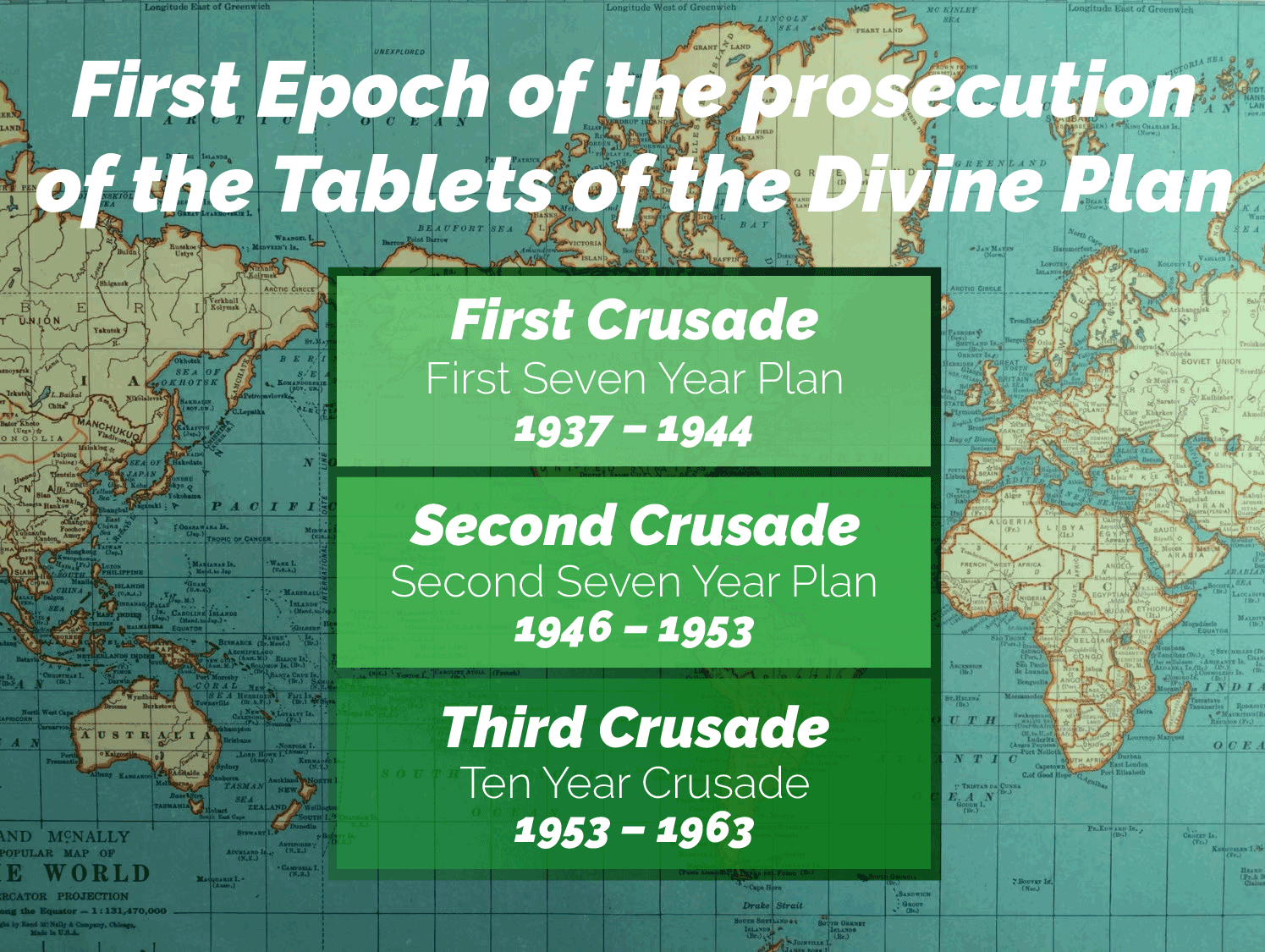

At Riḍván 1937, 16 years after the Ascension of 'Abdu'l-Bahá and the start of his own ministry, the Guardian inaugurated the first of three Teaching Plans aimed at realizing 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s vision in The Dispensation of Bahá'u'lláh into reality. These three plans are the first three phases of the first epoch of the Divine Plan or the three spiritual. Crusades, as Shoghi Effendi called them:

- The First Seven Year Plan from 1937 to 1944;

- A two-year period of respite towards the end of the Second World War between 1944 and 1946;

- The Second Seven Year Plan from 1946 to 1953;

- The Ten Year Crusade beginning in 1953 and ending in 1963, itself divided into four phases and its conclusion coinciding with the Centenary of the Declaration of Bahá'u'lláh in the Garden of Riḍván in Baghdad, the Centennial of the first century of the Bahá'í Dispensation..

The Second Epoch of the Divine Plan would begin in 1963.

The last 20 years of the Guardian’s ministry, from 1937 to 1957 were focused on conquering the planet from north to south and east to west with the light of 4,200 Local Spiritual Assemblies in 251 territories, and 230 languages.

For the last 20 years of his Guardianship, Shoghi Effendi was at the head of a spiritual conquest to plant the banner of Bahá'u'lláh in every corner of the earth.

With the first Seven Year Plan beginning in 1937 when he was forty years old, the Guardian stepped out, in Rúḥíyyih Khánum’s words, “as the general leading an army - the North American Bahá'ís - and marched off to the spiritual conquest of the western Hemisphere.”

With the first Seven Year Plan beginning in 1937 when he was forty years old, the Guardian stepped out, in Rúḥíyyih Khánum’s words, “as the general leading an army - the North American Bahá'ís - and marched off to the spiritual conquest of the western Hemisphere.”

In the same analogy of the First Seven Year Plan, with the Guardian as its general, its chief of staff was the National Spiritual Assembly of the United States, and its soldiers the American Bahá'ís.

Shoghi Effendi never forgot the rank and file of believers, and in his messages to them, he was their brother, speaking so intimately and knowledgeably to them, it was as if he lived amongst them.

For four years prior to the launch of the Second Year Plan, Shoghi Effendi sent rumblings of a new era about to dawn, a new stage, and the year prior to his earth-shattering announcement, he initiated the next year’s Plan:

Would to God every state within American Republic every Republic American continent might ere termination this glorious century embrace light Faith Bahá'u'lláh establish structural basis His World Order.

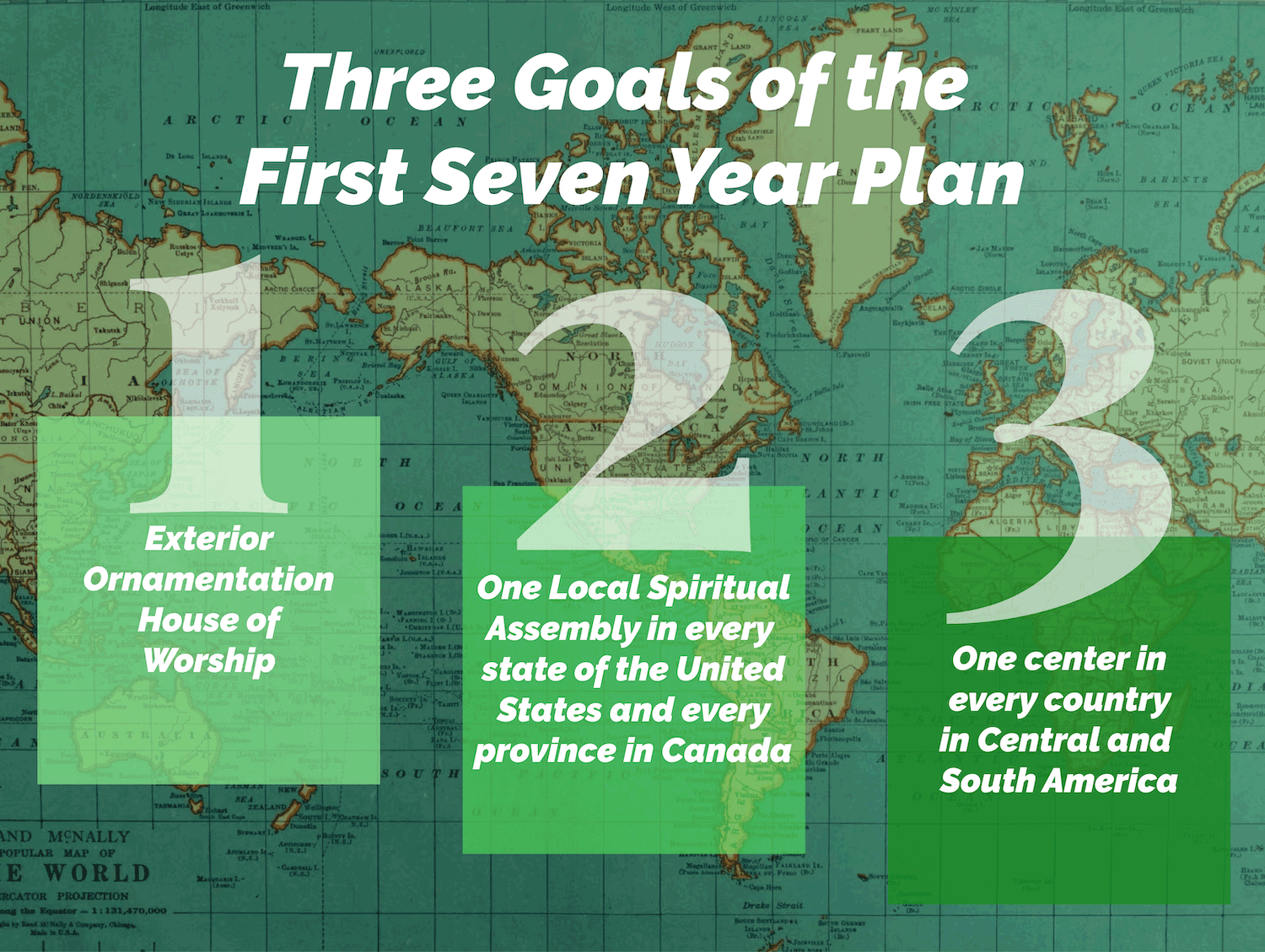

The first Seven Year Plan had three major goals:

- To complete the exterior ornamentation of the first House of Worship in the western World in Wilmette, Illinois;

- To establish one local Spiritual Assembly in every state of the United States and every province in Canada;

- To create one center in every country in Central and South America.

Two years after the Plan was launched, World War II erupted, and two years after that, the entire world was embroiled in the conflict, including the United States.

Shoghi Effendi kept in close touch with Bahá'ís involved in achieving the goals of the first Seven Year Plan.

What they achieved together was nothing short of miraculous. The end of this story takes place in 1944, with the achievements of the first Seven Year Plan.

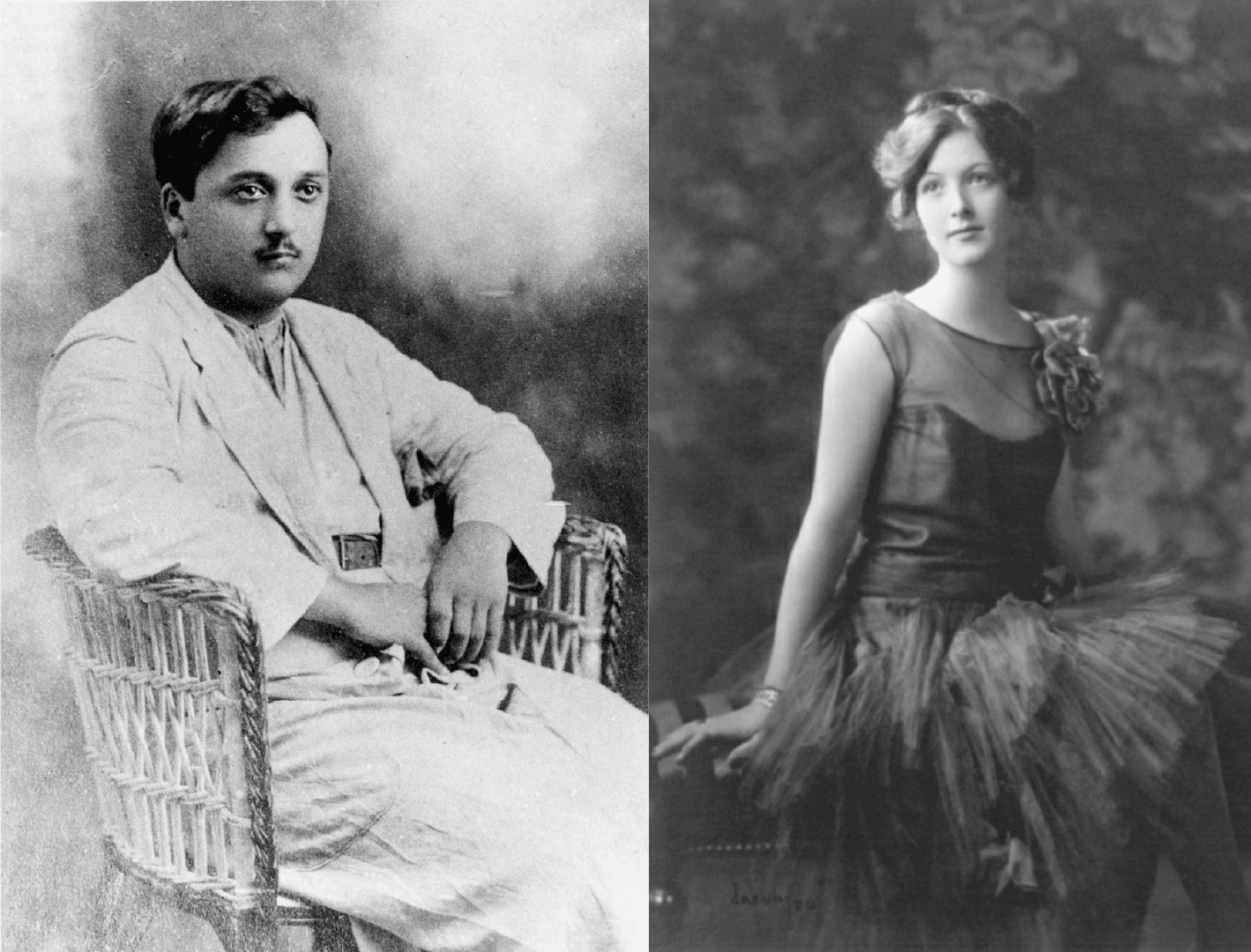

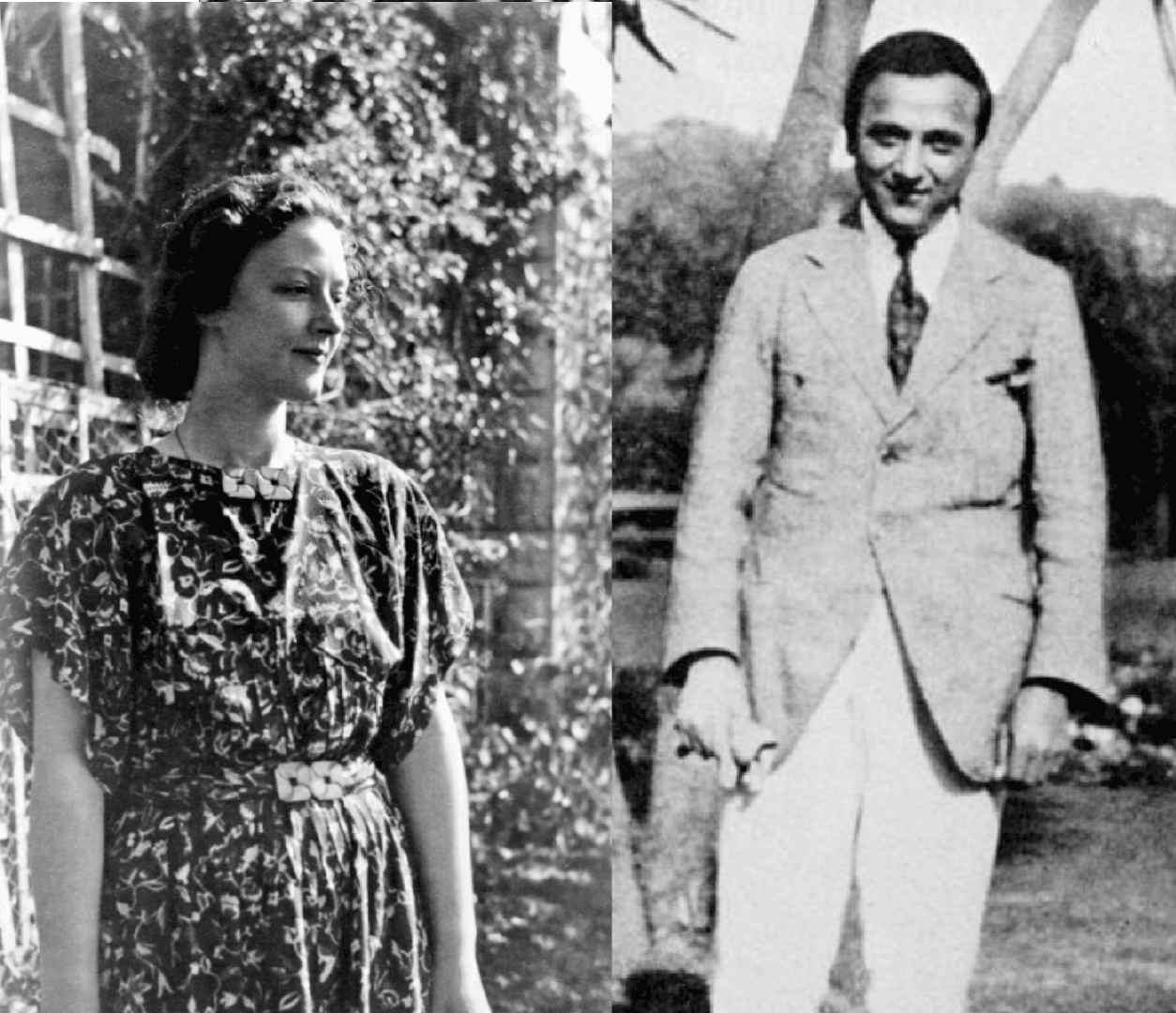

East and West. Two photographs—previously attributed in this chronology—of Shoghi Effendi—aged 22—and Mary Maxwell at the age of 16.

There are several very important points to mention regarding the Shoghi Effendi’s marriage to Mary Maxwell—now Rúḥíyyih Khánum.

First is that it was the marriage between the Guardian of the Faith and the daughter of two stalwart prominent, faithful and dedicated Bahá'ís. She herself would be elevated to the rank of Hand of the Cause, but she was also the daughter of a future Hand of the Cause—William Sutherland Maxwell—and a future Martyr—May Maxwell.

There is also a powerful connection with 'Abdu'l-Bahá in this marriage. Shoghi Effendi was the grandson of 'Abdu'l-Bahá. May Bolles Maxwell had been one of the very first handful of western Bahá'ís to ever meet the Master in 1898. It was 'Abdu'l-Bahá who had granted her wish to have a child during her 1909 pilgrimage, after she had shown Him her detachment and desire only for His good-pleasure. Mary Maxwell was born in 1910. Two years later, the Maxwell home on Pine Avenue would be the only home 'Abdu'l-Bahá would visit in Montreal. He loved and cuddled little Mary, who snuck onto the Master to sleep with Him on his chair, and she even slapped 'Abdu'l-Bahá and sent His turban flying when he wanted to plant a kiss on her cheek. To her traumatized parents who wanted to punish her, He said: “Leave her alone, she is the essence of sweetness.”

But the most important point that must be forever associated with the Guardian’s marriage to Rúḥíyyih Khánum is that it had united, at the Center of the Cause, East and West.

The union of the people of East and West was deeply cherished by Bahá'u'lláh who revealed it in one of his most celebrated verses in the Lawḥ-i-Maqṣúd (Tablet of Maqṣúd):

It is not for him to pride himself who loveth his own country, but rather for him who loveth the whole world. The earth is but one country, and mankind its citizens.

'Abdu'l-Bahá spoke openly and frequently on the union between East and West, even giving a talk on the subject in Paris, where He stated:

The East and the West must unite to give to each other what is lacking. This union will bring about a true civilization, where the spiritual is expressed and carried out in the material.

The Guardian, as with the most important statements and actions of 'Abdu'l-Bahá during His ministry, brought about the realization of his beloved Grandfather’s dearest wishes.

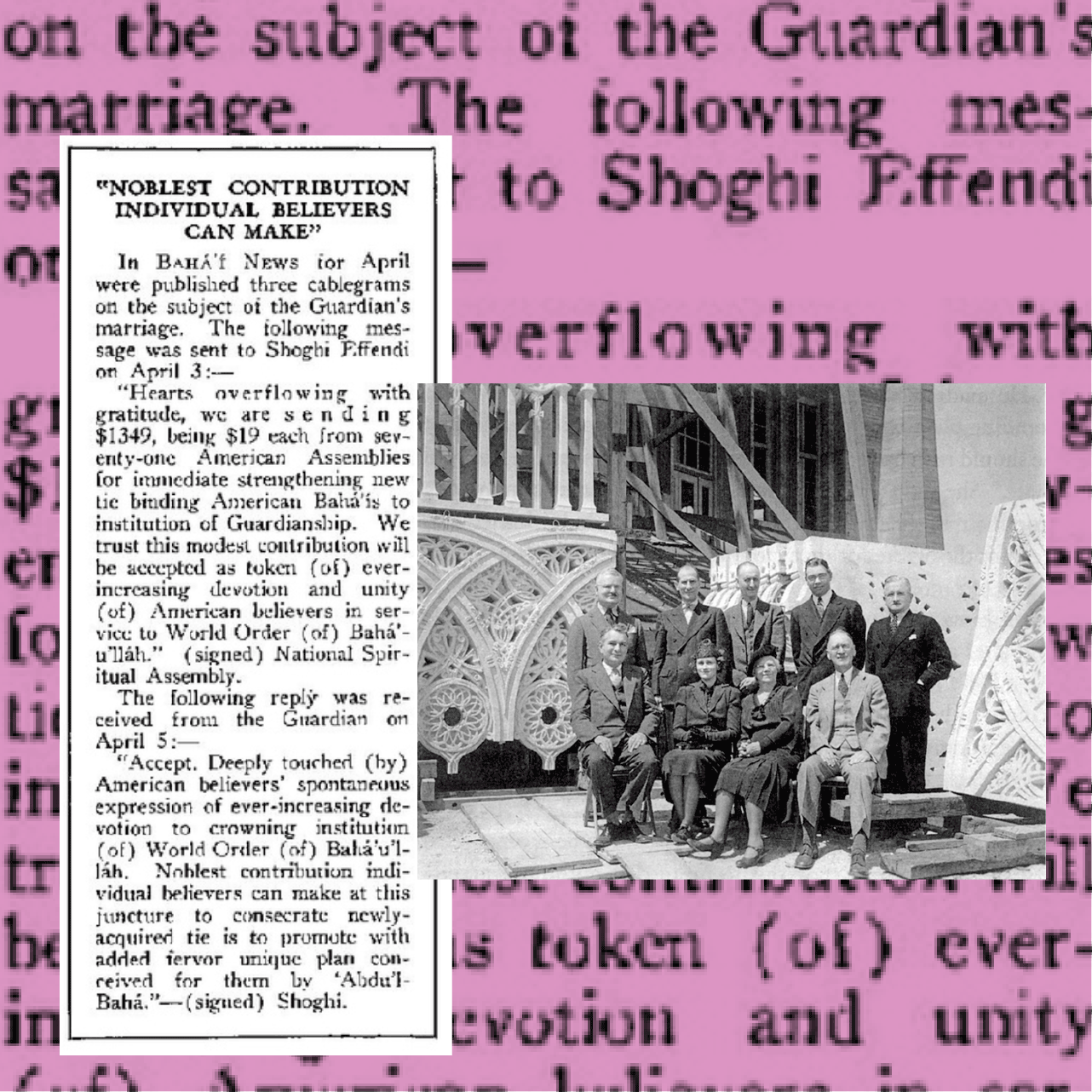

Publication of the contribution of $19 per Local Spiritual Assembly and the Guardian’s response in Bahá'í News Number 108 (June 1937). Photograph of the National Spiritual Assembly of the United States and Canada from 1938 (no photograph of the National Spiritual Assembly from 1937 was found). Source: Bahaimedia.

The Guardian’s emphasis on the honor bestowed on North America in his marriage to Rúḥíyyih Khánum and the union of East and West it represented so enthused the Bahá'ís in America that their National Spiritual Assembly informed the Guardian on 3 April 1937 that they were sending $19 from each of their 71 Local Spiritual Assemblies:

Hearts overflowing with gratitude we are sending $1349 being $19 each from seventy-one American Assemblies for immediate strengthening new tie binding American Bahá’ís to institution Guardianship. Trust this modest contribution will be accepted as token ever-increasing devotion and unity American believers in service to World Order Bahá’u’lláh.

This gesture was incredibly beautiful—and incredibly generous. $1,349 in 1937, calculated with inflation is $28,822.79 today, and $19 for each Local Spiritual Assembly today is worth $ 405.95.

Two days later, on 5 April 1937, the Guardian responded to this wonderfully touching gift, with an equally deeply sensitive message:

Accept deeply touched American believers spontaneous expression of ever-increasing devotion to crowning institution World Order Bahá’u’lláh. Noblest contribution individual believers can make at this juncture to consecrate newly-acquired tie is to promote with added fervor unique plan conceived for them by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá.

Shortly after his marriage, the National Spiritual Assembly of the United States and Canada wrote to the Guardian asking about the policy regarding making a public announcement of his nuptials. The Guardian responded:

Approve public announcement emphasize significance institution Guardianship union East West and linking destinies Persia America allude honour conferred British peoples.

By “honor conferred British peoples,” the Guardian was specifically referring to Rúḥíyyih Khánum’s father, William Sutherland Maxwell’s Scottish ancestry.

A portrait of May Maxwell, seated. Source: We are Bahá’ís.

May Ellis Bolles at the age of 14. Source: The Maxwells of Montreal: Early Years (1870 – 1922), Violette Nakhjavani, Kindle Edition, Location 974.

In marrying Rúḥíyyih Khánum, Shoghi Effendi had gained a faithful Bahá'í family, one that would comfort him for decades while his own flesh and blood broke the Covenant again and again.

First, who was May Bolles Maxwell, and why would Shoghi Effendi had told her that she was one of the reasons he had consented to marrying her daughter, Rúḥíyyih Khánum?

May Maxwell was American. She was born May Ellis Bolles in Englewood, New Jersey, on 14 January 1870, the daughter of John B. Bolles and Mary Martin Bolles. Even as a young child she was possessed of those same rare, lifelong qualities that set her so far above other people: she was deeply affectionate and had the ability to forge enduring bonds of friendship, she was eager for the truth and would follow it wherever it lead, she was devastatingly frank—a trait her daughter most definitely inherited—she had an oceanic empathy, she was utterly detached, her feelings would never get hurt, and she was immensely generous, extremely original and profoundly spiritual. One of her favorite sayings was:

By the time you finish talking about it you could have it done!

May Ellis Bolles (Photographer: Hargrave & Gubelman, West 23rd Street, New York). Source: The Maxwells of Montreal: Early Years (1870 – 1922), Violette Nakhjavani, Kindle Edition, Location 1201.

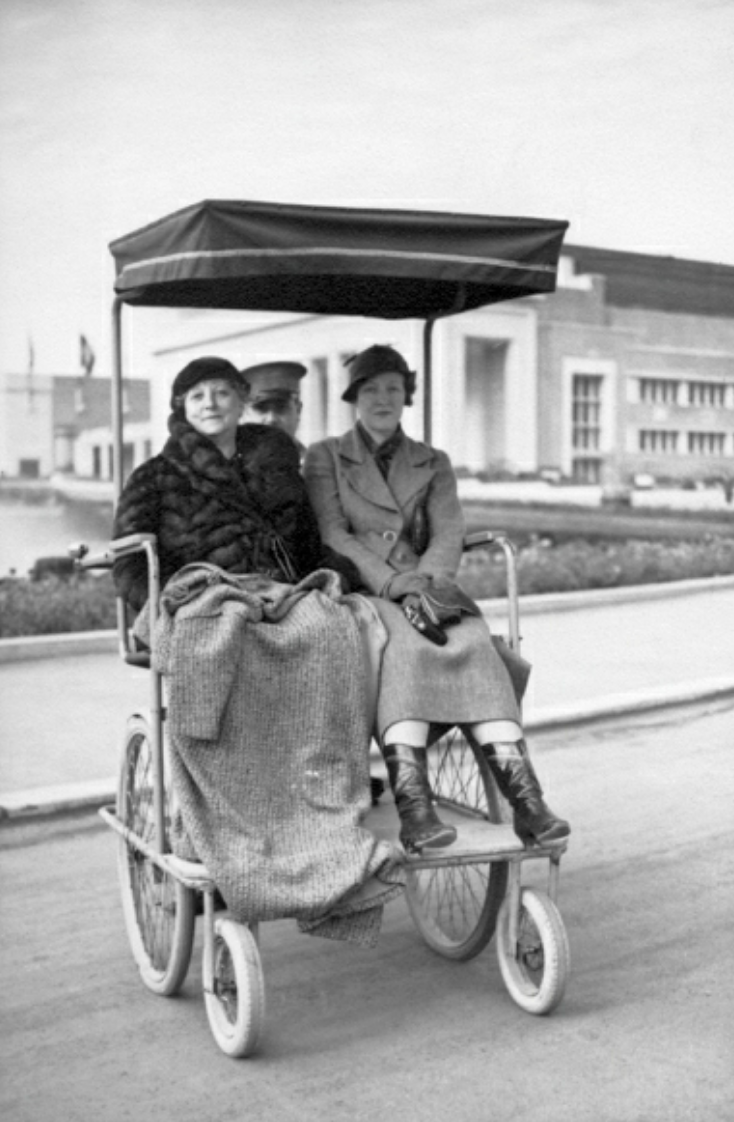

An important aspect to remember when marvelling at the life of May Maxwell, is that, from the age of 21 in 1891 until the day she died on 1 March 1940, at the age of 70, May Maxwell, in her daughter Rúḥíyyih Khánum’s own words, was, for “the large proportion of her life an invalid.” The great tragedy of May Maxwell’s life was her health.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum was never able to walk with her mother more than 100 meters.

May Maxwell’s life—in every single other respect—was blessed and happy, but she was born with a mysterious illness that was never diagnosed. 'Abdu'l-Bahá would later confirm this to her.

May Bolles was a burst of pure energy until she became ill for the first time in her life, in 1891, at the age of 21. She later told her daughter that before that illness, she could swim in the morning, play three sets of tennis in the afternoon and dance until midnight.

If she was inside the house, May Maxwell could walk around between rooms, but outside, her back and legs would become so exhausted that she could never walk more than a short distance.

Her illness was never definitively diagnosed, and caused her lifelong pain. Although she could not go on long walks with friends and was confided to sitting on a bench while they strolled around, this did allow her to meet hundreds of people throughout her life!

May Bolles after her first pilgrimage, circa 1899. Source: The Maxwells of Montreal: Early Years (1870 – 1922), Violette Nakhjavani, Kindle Edition, Location 1867.

In 1898, May Bolles was living in Paris with her mother and brother, who was studying at the Beaux-Arts. She became a Bahá'í in 1898 when she met Lua Getsinger, and joined the group of pilgrims, organized by Phoebe Hearst who were traveling through Paris on their way to 'Akká to meet 'Abdu'l-Bahá, the first westerners to ever go on pilgrimage. May Bolles was among a very small handful of westerners to meet Shoghi Effendi as a baby.

May Bolles first met 'Abdu'l-Bahá on 17 February 1899 and with her great talent for writing, she left behind an unforgettable account of this life-altering meeting:

Of that first meeting I can remember neither joy nor pain nor anything that I can name. I had been carried suddenly to too great a height; my soul had come in contact with the Divine Spirit; and this force so pure, so holy, so mighty had overwhelmed me…And when He arose and suddenly left us we came back with a start to life: but never again, oh! never again, thank God, to the same life on this earth!

'Abdu'l-Bahá would say of May Bolles:

Her company uplifts and develops the soul.

Early Bahá'í group of Paris, 1901 or 1902: standing, left to right, Miss Elsa Bignardi, Mr Herbert W. Hopper, Miss Florence Robinson, Mr Hippolyte Dreyfus, Miss Berthalin Lexow , Mr Charles Mason Remey, unknown, Mrs Marie-Louise MacKay, Mrs Margarite Bignardi, Miss Stephanie Hanvais, Mr Sydney Sprague; seated, left to right, Miss Edith MacKay, Miss Holzbecker, Miss Edith Sanderson, Mr Sigurd Russell, Mr Thomas Breakwell, Miss May Ellis Bolles, Mrs Hanet, Miss Marie Watson. Source: The Maxwells of Montreal: Early Years (1870 – 1922), Violette Nakhjavani, Kindle Edition, Location 3196.

She returned to Paris and between 1899 and 1902 alone, she was responsible for bringing into the Faith the following people:

Edith MacKaye, Charles Mason Remey, Herbert Hopper, Marie Squires (Hopper), Helen Ellis Cole, Laura Barney, Mme. Jackson, Agnes Alexander, Thomas Breakwell, Edith Sanderson, Hippolyte Dreyfus—the first French Bahá’í—Emogene Hoagg, Mrs. Conner, Sigurd Russell, Juliet Thompson, Lillian James.

May and William Sutherland Maxwell were married in London on 8 May 1902, and May returned to North America, the place of her birth, at the age of 32. It was a marriage of mutual love and devotion. May continued teaching intensely in Montreal, and William Sutherland Maxwell became the first Canadian Bahá'í in 1903.

May Maxwell is seated in the middle in the front row in the Garden of Riḍván. To her left is Louise Bosch. Photograph by William Sutherland Maxwell during their pilgrimage to the presence of 'Abdu'l-Bahá in 1909. Source: The Maxwells of Montreal: Early Years (1870 – 1922), Violette Nakhjavani, Kindle Edition, Location 5382.

Ten years after the first time she met 'Abdu'l-Bahá in person, in 1909, she and William Sutherland Maxwell travelled to the Holy Land for a six-day pilgrimage.

It was during this pilgrimage that 'Abdu'l-Bahá told her that, at 39, she was not too old to have a child and that he would pray for her. Mary Maxwell was born a year and a half later, on 8 August 1910.

May Maxwell, and a very young Mary Maxwell with John Harris Bolles, May’s father and Mary’s grandfather. Mary is wearing a string of beads given to her by 'Abdu'l-Bahá, Who visited her home in August-September 1912. Source: The Maxwells of Montreal: Early Years (1870 – 1922), Violette Nakhjavani, Kindle Edition, Location 6543.

When Mary Maxwell was 2 years old, 'Abdu'l-Bahá came to visit the Maxwells in Montreal and formed a bond with the spirited, delightful little girl. The Maxwell’s home was the only home visited by 'Abdu'l-Bahá, who said, when He first walked in:

This is my home, all that is in it is mine. You are mine – your husband and child. This is my home.

The Maxwell home in Montreal is now the only Shrine in North America.

On 19 August 1916, May Maxwell received, directly from 'Abdu'l-Bahá, the two Tablets of the Divine Plan He had revealed for the Dominion of Canada. These Tablets became her personal charter to travel. Mary Maxwell, then 9 years old, was one of girls chosen to unveil the Tablets of the Divine Plan at the National Convention on 26 – 30 April 1919 in New York.

May and Mary Maxwell at the Brussels Exposition, Belgium, 1935. Photo taken by W. S. Maxwell. Source: Source: The Maxwells of Montreal: Middle Years 1923-1937 Late Years 1937-1952. Violette Nakhjavani, Kindle Edition, Location 42787.

On 29 November 1921, May Maxwell learned of the Ascension of 'Abdu'l-Bahá and it nearly killed her. It would be the most serious illness of her life. She knew the only thing that could save her life was to meet the Guardian of the Cause, His Own grandson, Shoghi Effendi, and on 7 March 1923, she and Mary sailed for Haifa for the first of their two pilgrimages. Rúḥíyyih Khánum stated, in no uncertain terms, the Guardian had saved May Maxwell’s life:

Shoghi Effendi…literally resurrected a woman who was so ill she could still not walk a step and could move about only in a wheel chair.

William Sutherland Maxwell. Source: Canadian Bahá’í News.

Randolph Bolles—May’s brother—William Sutherland Maxwell and May Ellis Bolles in 1900, in Pierrefonds, France. Source: The Maxwells of Montreal: Early Years (1870 – 1922), Violette Nakhjavani, Kindle Edition, Location 2493.

Who was William Sutherland Maxwell? Who was this gentle, tall, Scottish Canadian man who was the husband of the extraordinary May Maxwell, the father of Shoghi Effendi’s wife, Rúḥíyyih Khánum, and the Guardian’s “immortal architect”?

William Sutherland Maxwell was born on 14 November 14 1874 in in Montreal, Quebec, Canada to parents Edward John Maxwell and Johan MacBean. He was four years younger than his future wife, May Bolles.

On both sides of his family, William Sutherland Maxwell was originally Scottish.

Like his wife, William Sutherland Maxwell was an extraordinary human being. His daughter, Rúḥíyyih Khánum, once described him as:

…one of those souls whose nature is all goodness. This is what led the Guardian of the Bahá’í Faith to attest to his “saintly life” in his obituary cable.

William Sutherland Maxwell was upright, truthful, and never approached anyone except with courtesy, friendliness, and graciousness. Despite a very trusting nature, William Sutherland Maxwell had very sound judgement.

From a young age, William Sutherland Maxwell was interested in building, but he refused to be an engineer and moved to Boston at the age of 17, and combining his extraordinary natural ability in drawing and design, he began working for an architectural office, designing ornamental details for building. It was in Boston he discovered the Beaux-Arts architectural style, and he followed his passion to its birthplace, Paris, where he met May Bolles.

After they married in London in 1902, they returned to Montreal. May always called her husband “Sutherland,” a name no one else ever used.

William Sutherland Maxwell and his brother Edward founded an architectural firm, and soon, Edward and W. S. Maxwell became known all over Canada.

In 1907 – 1908, William Sutherland Maxwell built the Maxwell home on Pine Street in Montreal, a home that is today a Shrine.

Travelling to 'Akká along the shore of the Mediterranean Sea in two horse-drawn-carriages. Photographed but not visible are May Maxwell and Louise Bosch during their pilgrimage in 1909. Also present but not pictured was William Sutherland Maxwell. Source: The Maxwells of Montreal: Early Years (1870 – 1922), Violette Nakhjavani, Kindle Edition, Location 5382.

When he accompanied his wife May on pilgrimage in 1909, William Sutherland Maxwell told 'Abdu'l-Bahá at the dinner table one day:

The Christians worship God through Christ; my wife worships God through You; but I worship Him direct.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá smiled and said:

Where is He?

William Sutherland Maxwell replied:

Why, God is everywhere.

'Abdu'l-Bahá said:

Everywhere is nowhere.

Then, the master

'Abdu'l-Bahá explained to William Sutherland Maxwell the role of Manifestations of God, and with this explanation, He planted the seed of faith in William Sutherland Maxwell’s heart, a seed that would bloom into a mighty tree: he left the Holy Land a Bahá'í.

In 1912, when 'Abdu'l-Bahá arrived in Montreal, it was William Sutherland Maxwell who picked Him up from the train station. 'Abdu'l-Bahá told him He had been attracted to Montreal by the devotion of his wife, May Maxwell. During His stay, 'Abdu'l-Bahá told May Maxwell that her husband was “a very good man.”

Mary and William Sutherland Maxwell with Alfons Grassle in Munich, Germany, 1935. Source: The Maxwells of Montreal: Middle Years 1923-1937 Late Years 1937-1952. Violette Nakhjavani, Kindle Edition, Location 4592.

William Sutherland Maxwell served on the Montreal Local Spiritual Assembly for decades, mostly as Chairman of the Assembly.

William Sutherland Maxwell was an artist.

His innate goodness and his art were inseparable sides of who he truly was.

In one of her letters to him, May Maxwell said to her husband:

You have the charm of originality.

William Sutherland Maxwell was a living, breathing art encyclopedia, which combined with his boundless creativity to bring original new designs into the world. His masterpiece were his two expansions on a famous Montreal hotel, the Château Frontenac, which he completed in 1908–09, and 1920–24.

He designed the lines of the 20-story hotel, and every detail of the interior: wrought-iron railings, furniture, grills, lamps, ceilings, and elevator interiors. William Sutherland Maxwell was so dedicated to his work that he would take the chisel from the stonemason, the gouge from the wood-carver, and, as he said it himself, he would “sweeten the lines.” The workers working under him idolized him.

Eventually, William Sutherland Maxwell was made a Fellow of the Royal Institute of British Architects, a Fellow and past president of the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada, an Academician of the Royal Canadian Academy and its vice-president, a member and past president of the Province of Quebec Association of Architects; a founding member of both the Pen and Pencil Club and the Arts Club in Montreal. He received countless medals and honor which testified to his abilities as an architect and to his character.

William Sutherland Maxwell was a talented painter and his watercolors were often showed. and his water colors often hung in Academy shows.

On 27 February 1937, William Sutherland Maxwell received, out of the blue, a cable urging him to leave Montreal at once in order to be present for his daughter’s marriage to…Shoghi Effendi!

Agnes B. Alexander and May Maxwell, in Portland, Oregon, 3 July 1934, three years before they meet again in Haifa. Source: The Maxwells of Montreal: Early Years (1870 – 1922), Violette Nakhjavani, Kindle Edition, Location 4165.

William Sutherland and May Maxwell stayed in the Holy Land for two months after Rúḥíyyih Khánum’s wedding. And the Guardian met them almost every night for dinner, though there was no time for any deep personal intimacy to develop, as Rúḥíyyih Khánum stated.

During this time, William Sutherland Maxwell took many photographs of the members of the Holy Family, which he used to illustrate an article titled Recollections of Munírih Khánum.

Agnes Alexander arrived on 20 April 1937, and was ecstatic at the news, saying:

How marvelous are the ways of the beloved Guardian!

May Maxwell was ill for most of the time between March and May with fevers, William Sutherland Maxwell at her side, as she was in a state of emotional upheaval. She was at the same time ecstatic at the marriage of her beloved daughter and filled with sorrow at the idea of being separated from her when she left. From Nazareth, she wrote Shoghi Effendi, now her son-in-law as well as her Guardian:

I long so to see you! But the doctor said that only when I have no temperature could I get up, but you must feel the longing in my heart.

Photograph of 'Abdu'l-Bahá addressing a large gathering at the Plymouth Congregational Church, Chicago, Illinois, 5 May 1912. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

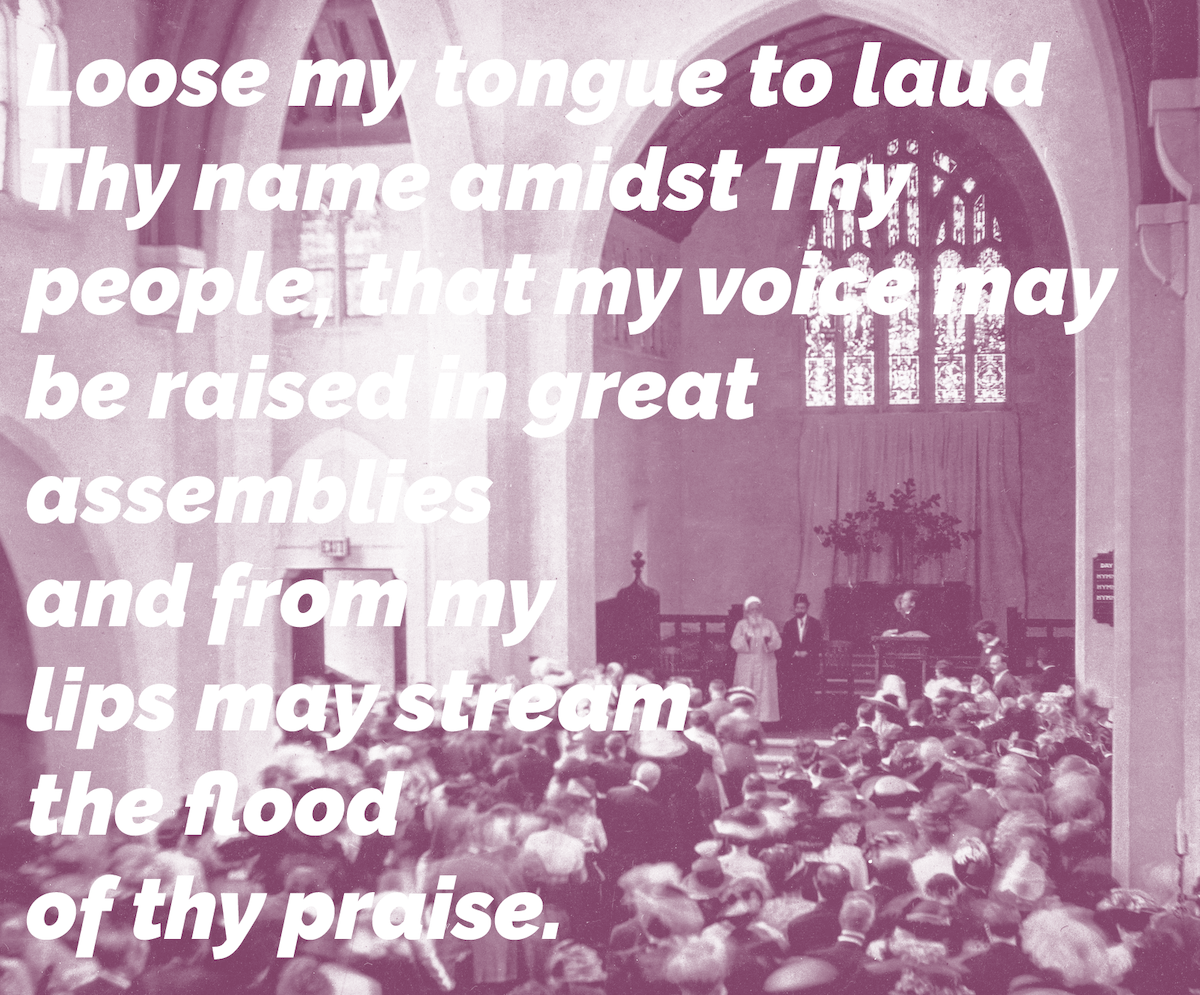

At the beginning of their marriage, Shoghi Effendi recommended to Rúḥíyyih Khánum that she memorize the prayer revealed by 'Abdu'l-Bahá which begins “O Lord, my God and my Haven in my distress! My shield and my Shelter in my woes! …” and which concludes with the poignant sentence: “Loose my tongue to laud Thy name amidst Thy people, that my voice may be raised in great assemblies and from my lips may stream the flood of thy praise.”

For the rest of her life, Rúḥíyyih Khánum, would attribute her legendary power of public speaking to Shoghi Effendi’s advice to memorize the prayer of 'Abdu'l-Bahá at the start of their marriage.

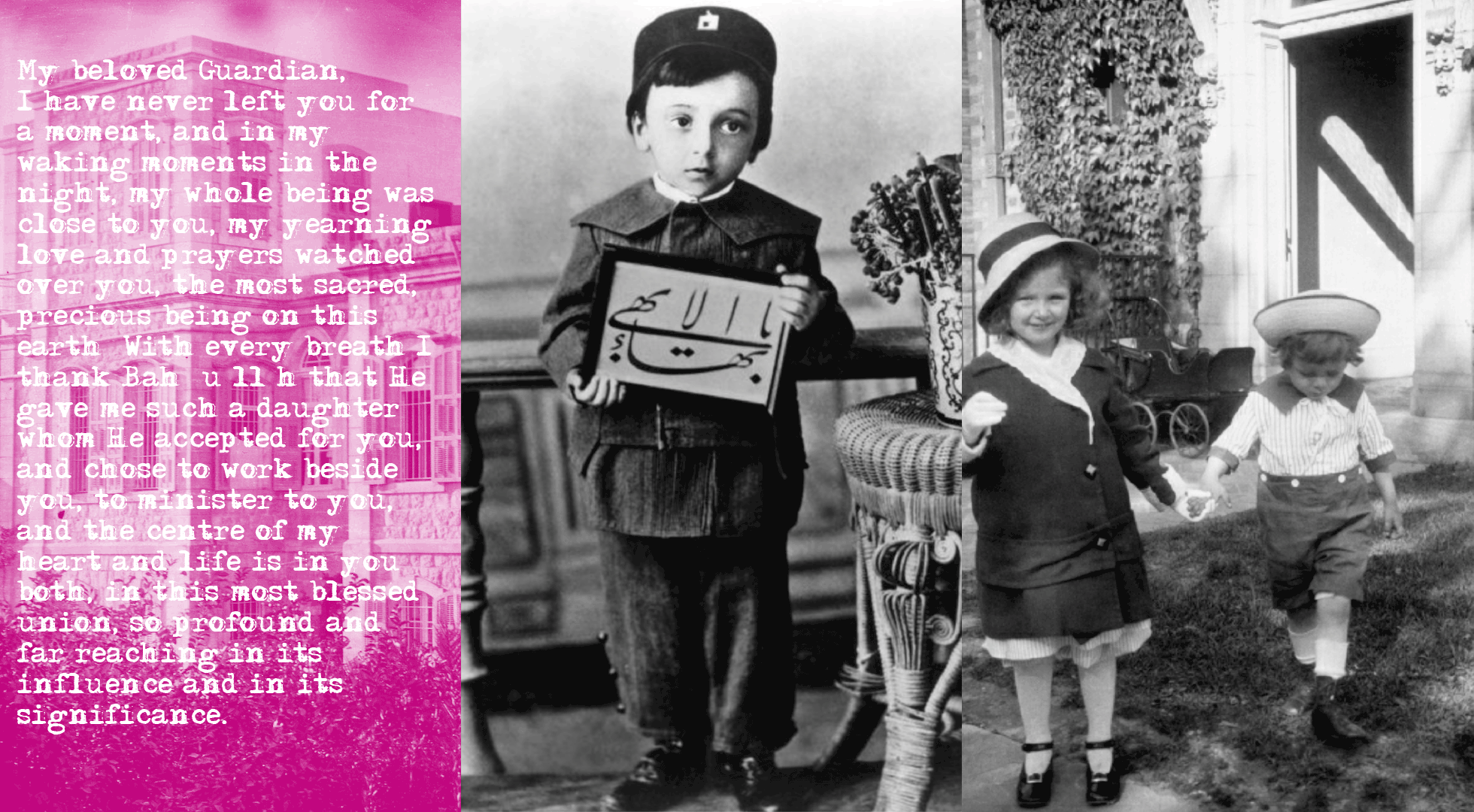

May Maxwell’s farewell letter to the Guardian. Photograph of Shoghi Effendi as a young child previously attributed in the chronology. Photograph of May Maxwell as a young child with her cousin Randolph Bolles, Jr., in front of the Maxwell home at 1548 Pine Avenue, Montreal. Source: The Maxwells of Montreal: Early Years (1870 – 1922), Violette Nakhjavani, Kindle Edition, Location 6453.

At midnight the night before she and Sutherland Maxwell left Haifa, May Maxwell had written an extremely moving letter to the Guardian, which can be found in Violette Nakhjávání’s extraordinary memoir, The Maxwells of Montreal, in full. It reads, in part:

My beloved Guardian,

I have never left you for a moment, and in my waking moments in the night, my whole being was close to you, my yearning love and prayers watched over you, the most sacred, precious being on this earth! With every breath I thank Bahá’u’lláh that He gave me such a daughter whom He accepted for you, and chose to work beside you, to minister to you, and the centre of my heart and life is in you both, in this most blessed union, so profound and far reaching in its influence and in its significance.

At the end of the letter, May Maxwell wrote a short note, in the form of a letter, informing the Guardian that she and her husband would soon be able to send him $500 for him to use as he saw fit, and she closed this second letter with a sweet note:

Please forgive this very messy letter.

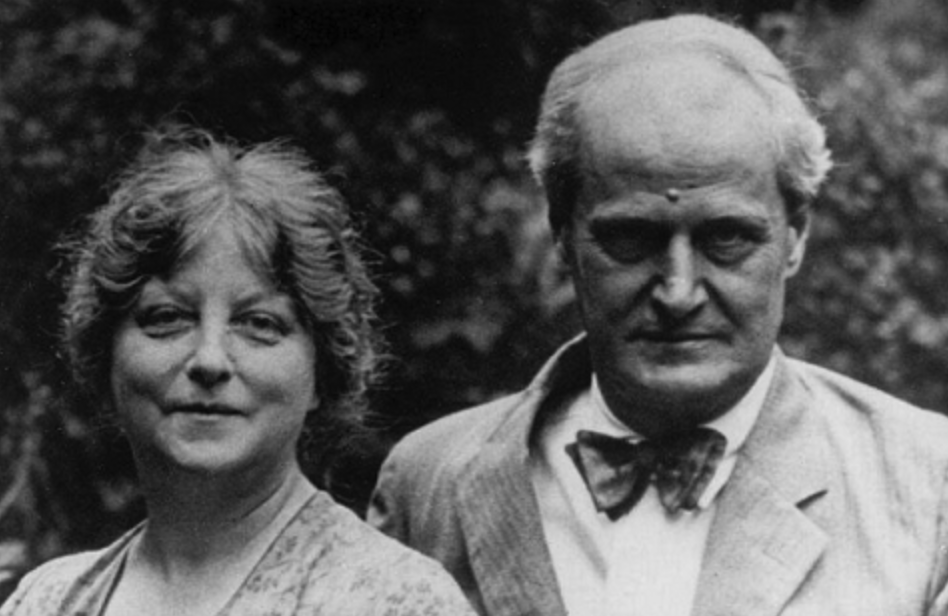

May and William Sutherland Maxwell. Source: The Bahá'í community of Ottawa.

The Maxwells left Haifa on 30 May 1937.

On the day of her departure, May Maxwell said to her daughter, Rúḥíyyih Khánum:

Mary, do you think the Guardian will kiss me good-bye?

Rúḥíyyih Khánum had never given that eventuality a thought, and she casually mentioned it to Shoghi Effendi, of course, not asking him to do anything about it.

The Maxwells were leaving in the afternoon, and after lunch, the Guardian went to see May Maxwell in her room in the Pilgrim House. After he had left, Rúḥíyyih Khánum went to her mother, who beamed, her eyes, as her daughter said, “shining like two stars,” and she told her:

He kissed me.

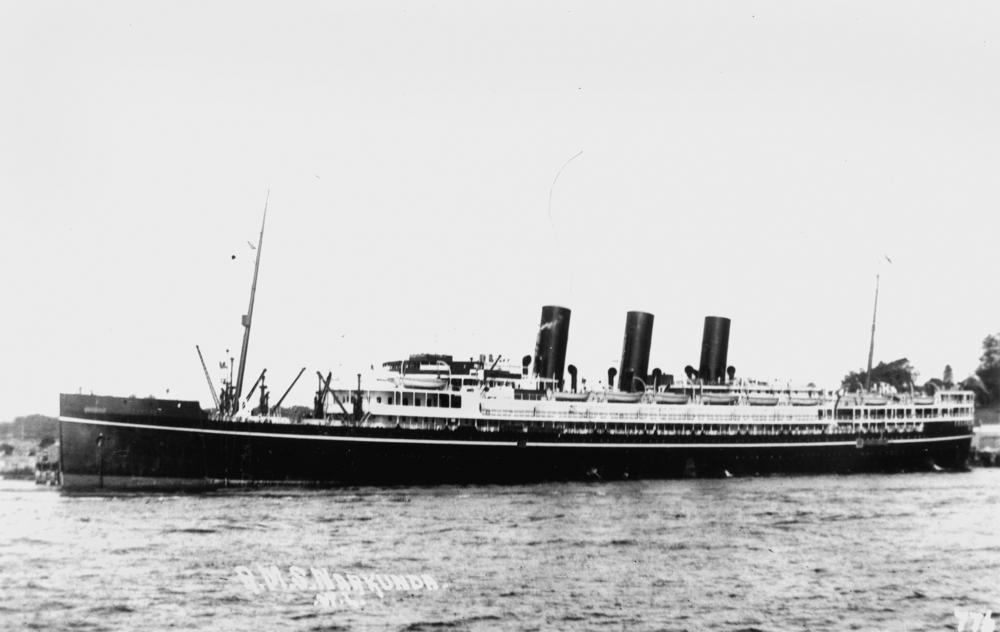

The S.S. Narkunda, the ship on which William Sutherland and May Maxwell sailed on, and to which the Guardian sent his cable. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The next day, 31 May 1937, Shoghi Effendi sent the following cable to the Maxwells, addressed to the Captain of the S.S. Narkunda:

With you both always Shoghi.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum sent her parents a cable on the next day, 1 June 1937:

Loving you both tenderly very happy our great blessings Rúhíyyih.

“On top of the world”: Shoghi Effendi’s bicycle—the poor man’s car—became a favorite of Shoghi Effendi. He sometimes climbed the heist passes in Switzerland, pushing it up and riding it down. Source: The Priceless Pearl.

When Shoghi Effendi took Rúḥíyyih Khánum to Interlaken, Switzerland for the first time, in the summer of 1937, he was greatly looking forward to introducing his new wife to Mr. Hauser, his beloved Swiss mountain guide, in whose cabin he stayed in every summer since his first as Guardian in 1922.

Shoghi Effendi had become deeply attached to Mr. Hauser, and they were close friends, often writing to each other when Shoghi Effendi was in Haifa. Mr. Hauser was a good friend, and he always listened with great interest to Shoghi Effendi’s account of his day’s hike or climb, constantly marveling at Shoghi Effendi’s endless energy and determination.

When they arrived, Shoghi Effendi learned that Mr. Hauser had passed away, and he took Rúḥíyyih Khánum with him to the peaceful mountain cemetery, so he could pay his respects to his dear friend of 15 years.

A gorgeous photograph of the area around Zermatt, showing both the famed Matterhorn mountain and the train line. Photo by Ryan Klaus on Unsplash.

The Guardian loved Switzerland with all his heart.

In all the years that Rúḥíyyih Khánum traveled with Shoghi Effendi, she noticed he never formed personal relationship during their trips, and rarely spoke to strangers. Rúḥíyyih Khánum was very sociable, and would often leave their compartment and have exciting conversations with passengers on the train.

Except for this one, memorable incident.

Once, Rúḥíyyih Khánum and Shoghi Effendi were on a train, leaving Zermatt, a Swiss town about 72 kilometers south of Interlaken.

They were seated on hard wooden seats in the third-class compartment, and a lovely youth, a descendant of Russian emigrants in the United States, was sitting facing the Guardian and Rúḥíyyih Khánum.

It was the young man’s first trip to Switzerland, and Shoghi Effendi began speaking with him enthusiastically, giving him travel advice on which places he should not miss seeing in the time he had.

Shoghi Effendi pulled out the guide to Swiss railways, showing him which trains to take, where to go, when to go there.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum sat back and watched her Guardian, speaking to this young Russian-American, and saw how the youth was so pleased with the attention. How the Guardian loved Switzerland. It had the power to bring him back to life in so many ways, and even speaking about the place he loved to a stranger he would never see again, was a joy for him.

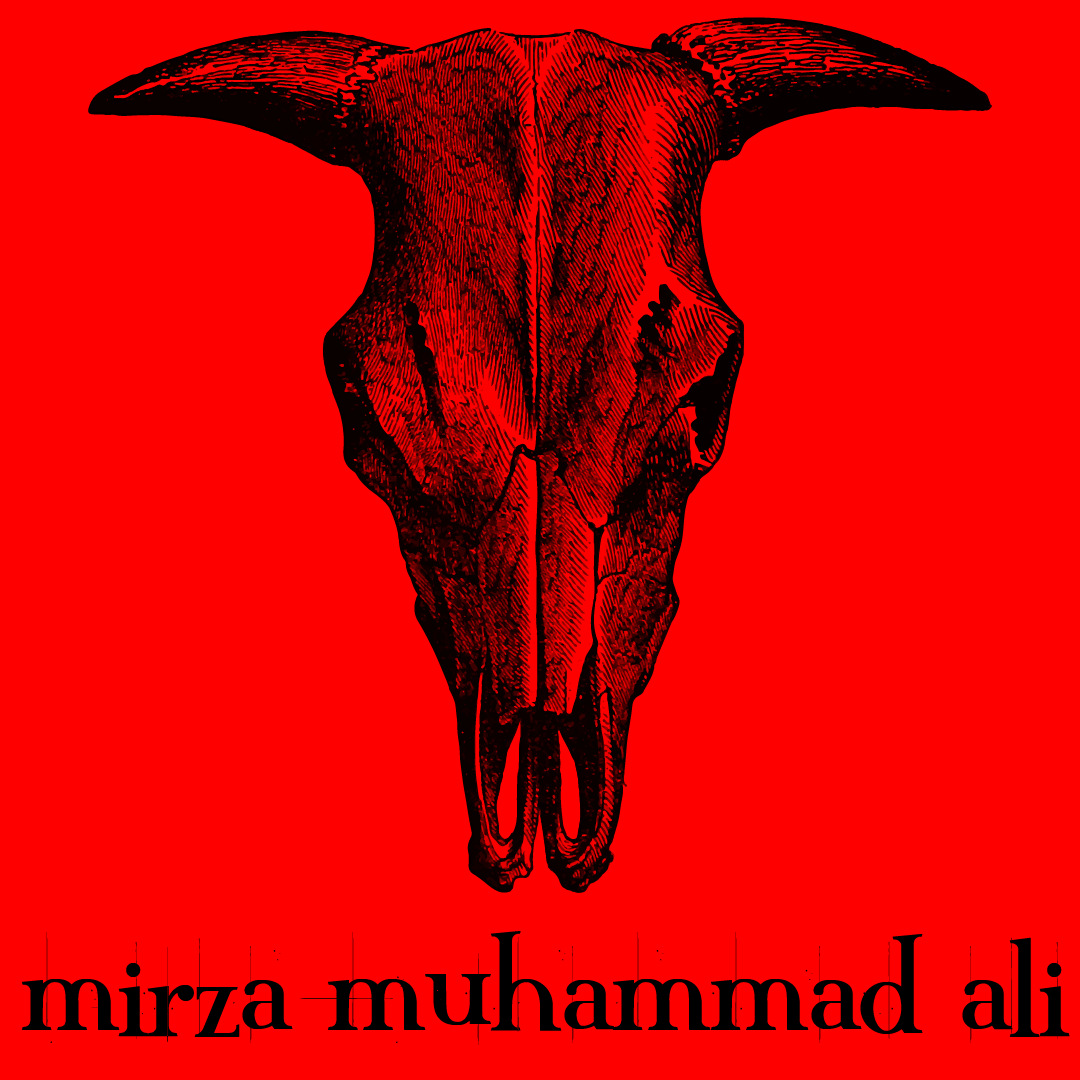

On 20 December 1937, Mírzá Muḥammad-'Alí, the Arch-Breaker of the Covenant of Bahá'u'lláh, and 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s half-brother died and Shoghi Effendi sent the following cable to Bahá'í world after his death:

The Hand of Omnipotence has removed the Archbreaker of Bahá'u'lláh's Covenant, his hopes shattered, his plottings frustrated, the society of his fellow-conspirators extinguished. God's triumphant Faith forges on, its unity unimpaired, its purpose unsullied, its stability unshaken. Such a death calls for neither exultation nor recrimination, but evokes overwhelming pity at so tragic a downfall unparalleled in religious history.

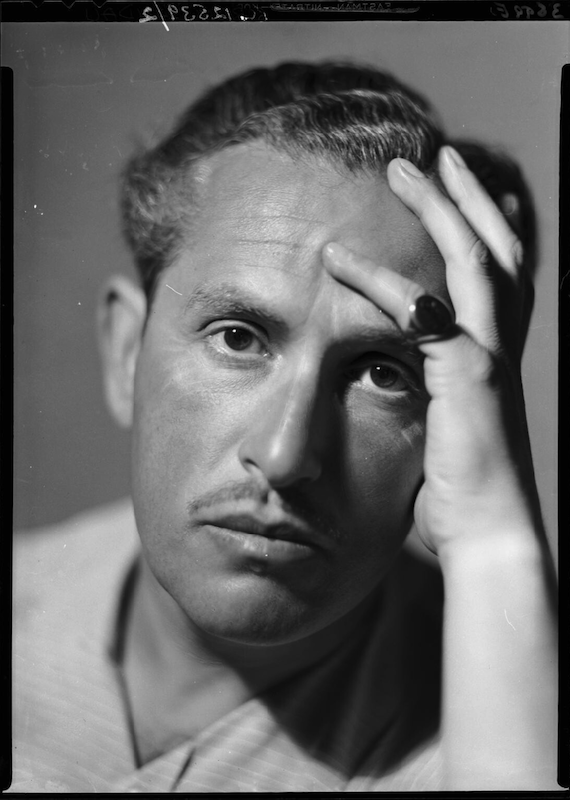

Rom Landau by Howard Coster half-plate film negative, 1937. Source: National Portrait Gallery, used according to Creative Commons License for educational non-profit purposes.

Romauld “Rom” Landau was born in Poland and studied philosophy, art, and religion at various European schools and universities notably in Germany, and spent his early years travelling and working as a sculptor. He earned a minor reputation in Europe as a writer on history, Polish biographies, and comparative religion, at the time he met the Guardian, his most well-known book was God is My Adventure, published in 1935.

In 1937 Rom Landau visited King Ibn Saud of Saudi Arabia, King Abdullah I of Jordan, and other secular and religious leaders of the Middle East, and published a book, Arm the Apostles in 1938, about his trip in which he advocated arming the Arabs so that they might aid the British and French in the coming war with Nazi Germany.

In 1938, Rom Landau visited the Middle East, and arrived in Haifa, where he met Shoghi Effendi, whom he had arranged to visit even before leaving England. Rom Landau was deeply anxious to meet Shoghi Effendi, because he considered the Bahá'u'lláh Fait to be, in his words:

It is one of the most important and most cosmopolitan of the various revivals which have emerged within the last hundred years from the womb of Islam. It is the least orthodox and most independent of them all.

His reason for being so eager to meet Shoghi Effendi was that he was eager to hear his views on religion:

…I was anxious to ascertain Shoghi Effendi's views on several subjects and to meet the Guardian of a faith which, in its Christian tolerance and its supernational and super-denominational appeal, contains some very attractive features.

Rom Landau was in shock when he first met Shoghi Effendi. He had built up Shoghi Effendi in his mind as a very impressive, formal man, and he met our sweet, friendly, loving Guardian:

Rarely has my imagination deceived me more blatantly than it did in the case of Shoghi Effendi. I imagined him a rather impressive-looking man, attractive by reason of some quality of gentleness or of a mixture of humanity and force. I expected dignity and should not have been surprised if I had met with unctuousness.

Rom Landau describes seeing Shoghi Effendi walk towards him with his distinctive, irrepressible energy: