Written and illustrated by Violetta Zein

This part covers the life of Shoghi Effendi from the age of 41 in 1938 to the age of 45 in 1942.

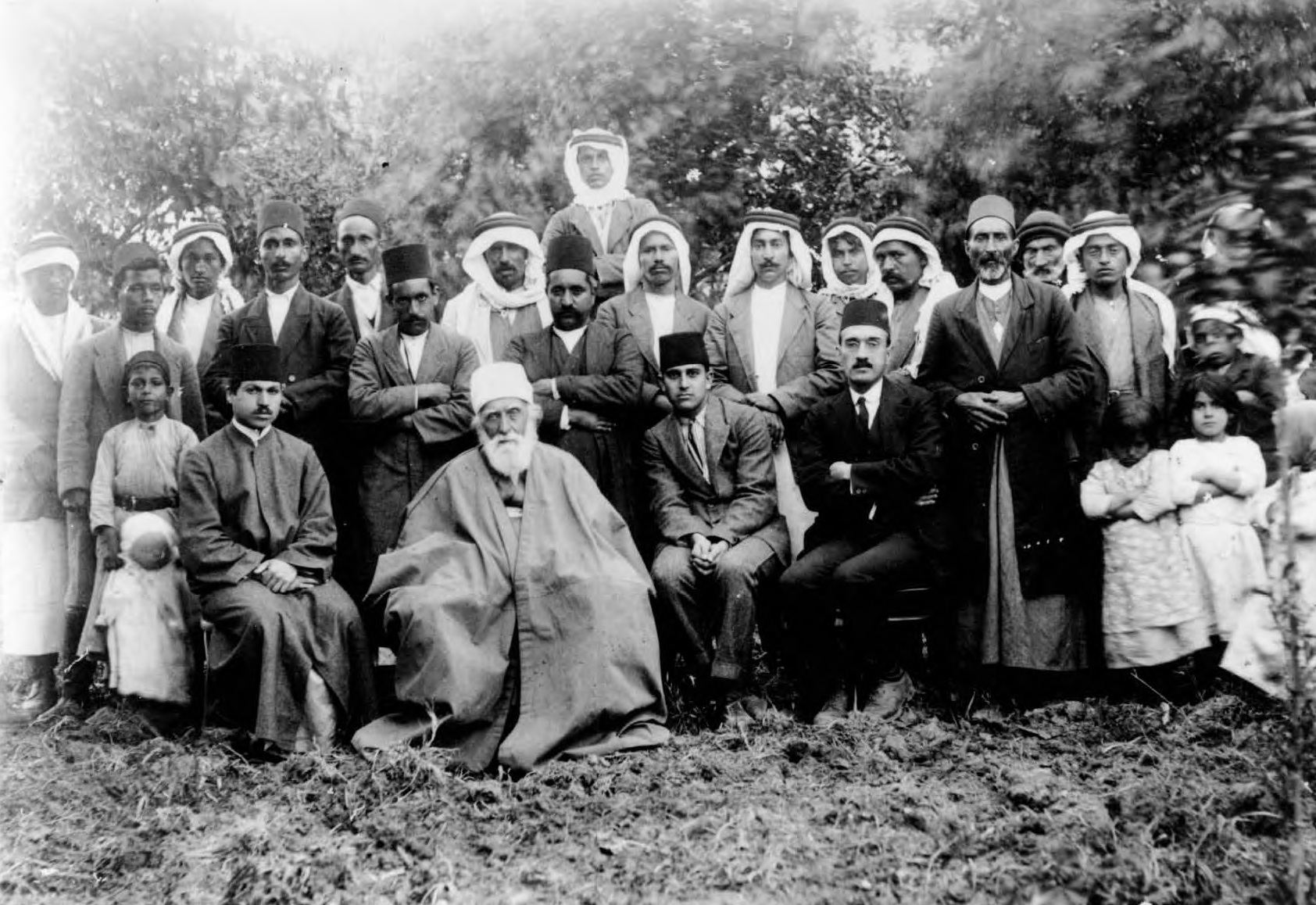

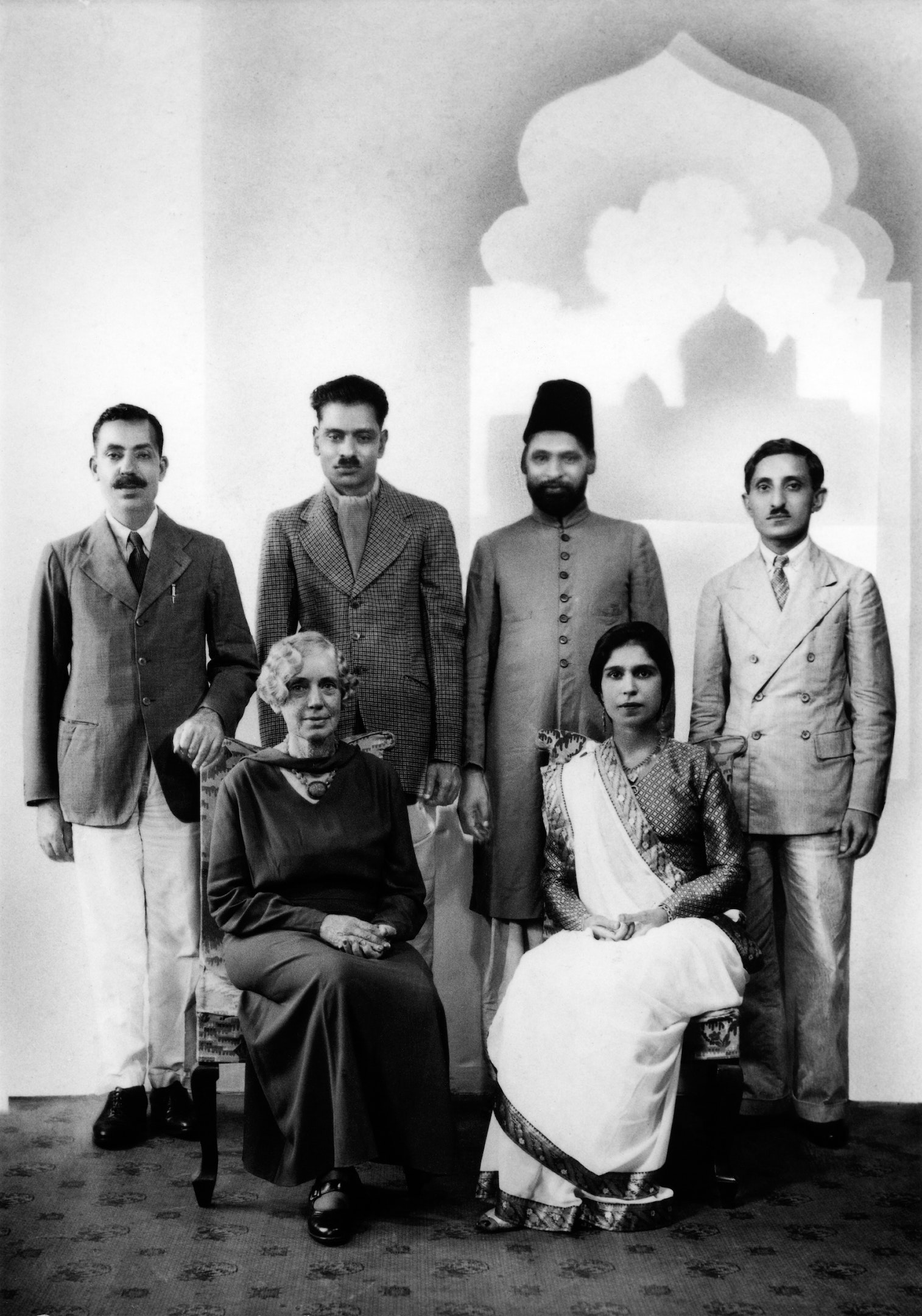

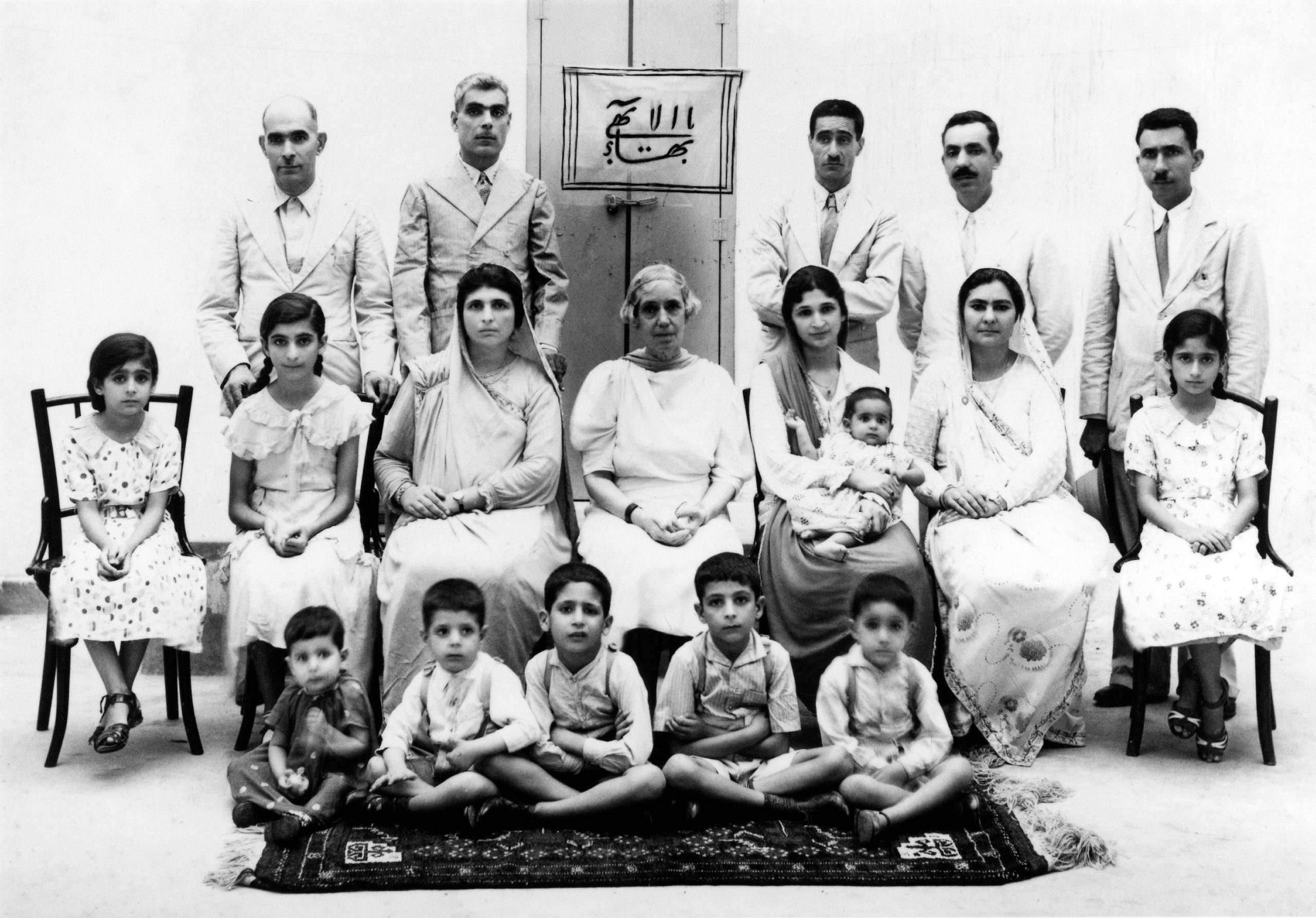

Photograph of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá with some of the Baha’i farmers of 'Adasiyyíh on Naw Rúz 1916. The farmers of ‘Adasiyyíh hired a professional photographer from Tiberias to take pictures of the event. Seated left to right: Subhi, ‘Abdu’l-Baha, Jalal Azal, `Azizu’llah Bahadur. Standing left to right: Rustam Mihragani (picture faint), Khusraw (cook), Rustam Firaydun (standing in front of Khusraw with a small child in front of him, Nuru’llah Mihragani, Bahram Firaydun, Shahriyar Mihragani, Rustam Bihmardi, Tirandaz Shah-Kavus, Bahram Bihmardi, Bahram Shah-Kavus (standing behind Bahram Bihmardi), Shahriyar Bihmardi, Mihraban Jamshid, a non-Baha’i named Shitaywi (behind), Isfandiyar Bihmardi,Jamshid Mihraban, ‘Ali Yazdi (behind), ‘Azizu’llah Shah-Kavus with child Homa Shahriar Behmardi in front, Isfandiyar Shah-Kavus (child blurred) with Shah-Jihan Hindi in front. Source: ’Adasiyyah: A Study in Agriculture and Rural Development (2010) by Iraj Poostchi, page 76.

In 1939, the Local Spiritual Assembly of ‘Adasiyyíh took steps to protect the holy places of ‘Adasiyyíh, following an instruction that 'Abdu'l-Bahá had given them. These holy places were places 'Abdu'l-Bahá had blessed with His presence on His many visits to the farming village.

On 21 February 1939, the Local Spiritual Assembly of ‘Adasiyyíh transferred a local Bahá'í, Mr. Bihmardi a new house they had built for him, and turned his former home into a holy place. 'Abdu'l-Bahá had often stayed there visiting ‘Adasiyyíh.

“Shades night descending.” A photograph of Interlaken by Josef Ivan Jimenea on Unsplash overlaid with a photograph of German mechanized troops entering Saaz, Chech Republic. The streets are decorated with swastika flags and banners (Wikimedia Commons). War is imminent.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum and Shoghi Effendi had left Haifa on 8 August 1939, and were in Switzerland when the long shadow of war began falling on Europe. Rúḥíyyih Khánum started experiencing a palpable feeling of catastrophe when Shoghi Effendi sent a somber cable, powerful and at the same time deeply poetic, to the American Bahá'í Community on 30 August 1939:

Shades night descending imperilled humanity inexorably deepening. American believers, heirs Bahá’u’lláh’s Covenant, prosecutors ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s Plan, confronted supreme opportunity vindicate indestructibility Faith, inflexibility resolution, incorruptibility sanctity for the appointed task. Anxiously, passionately entreat them, whatever obstacles march tragic events may create, however distressing barriers which the predicted calamities raise between them and sister communities, and possibly Faith’s World Center, unwaveringly hold aloft Torch whose infant Light heralds the birth effulgent World Order destined supplant disrupting civilization.

It was the Guardian’s task to constantly focus the Bahá'ís and keep their eyes on the spiritual conquest of the planet while everyone around them was trying to destroy each other. Bahá'ís could not be distracted from everlasting victories, and it was the Guardian who would consistently and systematically keep them calm, focused, enkindled, and resistlessly marching forward to win epoch-making victories for Bahá'u'lláh.

World War II began two days later and Shoghi Effendi and Rúḥíyyih Khánum were back in Haifa on 6 September 1939 after an exhausting sleepless return journey. They passed through blackened towns, saw troop trains moving, but they passed safely through.

A month after their arrival in Haifa, from 26 September to 5 October 1939, Shoghi Effendi was seriously ill for ten days with one of the most serious illnesses of his life. His fever spiked to 40 degrees Celsius several times and Rúḥíyyih Khánum lived through hell. She was all alone with the Guardian of the Faith who was seriously ill, and their doctor was, in her words, “strange.” For an entire week, Rúḥíyyih Khánum and Shoghi Effendi did not sleep more than 4 hours a night.

Comet Lovejoy, hurtling through space at about 500 kilometers per second. Source: Source: Wikimedia Commons.

In this magnificent excerpt of Rúḥíyyih Khánum’s diary, she returns to the theme of the power inherent in Shoghi Effendi’s unstoppable energy, comparing him at first to an object hurtling through space at insurmountable speed, then to a chemical, successively created through the agency of both Bahá'u'lláh and 'Abdu'l-Bahá:

The strongest impression I always get of Shoghi Effendi is of an object travelling uni-directionally with terrific force and speed. If Bahá'u'lláh shone like the sun, and the Master gently went on radiating His light, like the moon, Shoghi Effendi is an entirely different phenomenon, as different as an object hurtling towards its goal is from something stationary and radiating. Or one could liken him to a chemical. Bahá'u'lláh assembled everything that we needed, the Master mixed everything together and prepared it; then God adds to it "one "element, a sort of universal precipitant, needed to make the whole clarify and go on to fulfil its nature—this is the Guardian ...he is made exactly to fulfill the needs of the Cause—and consequently of the planet itself—at this time.

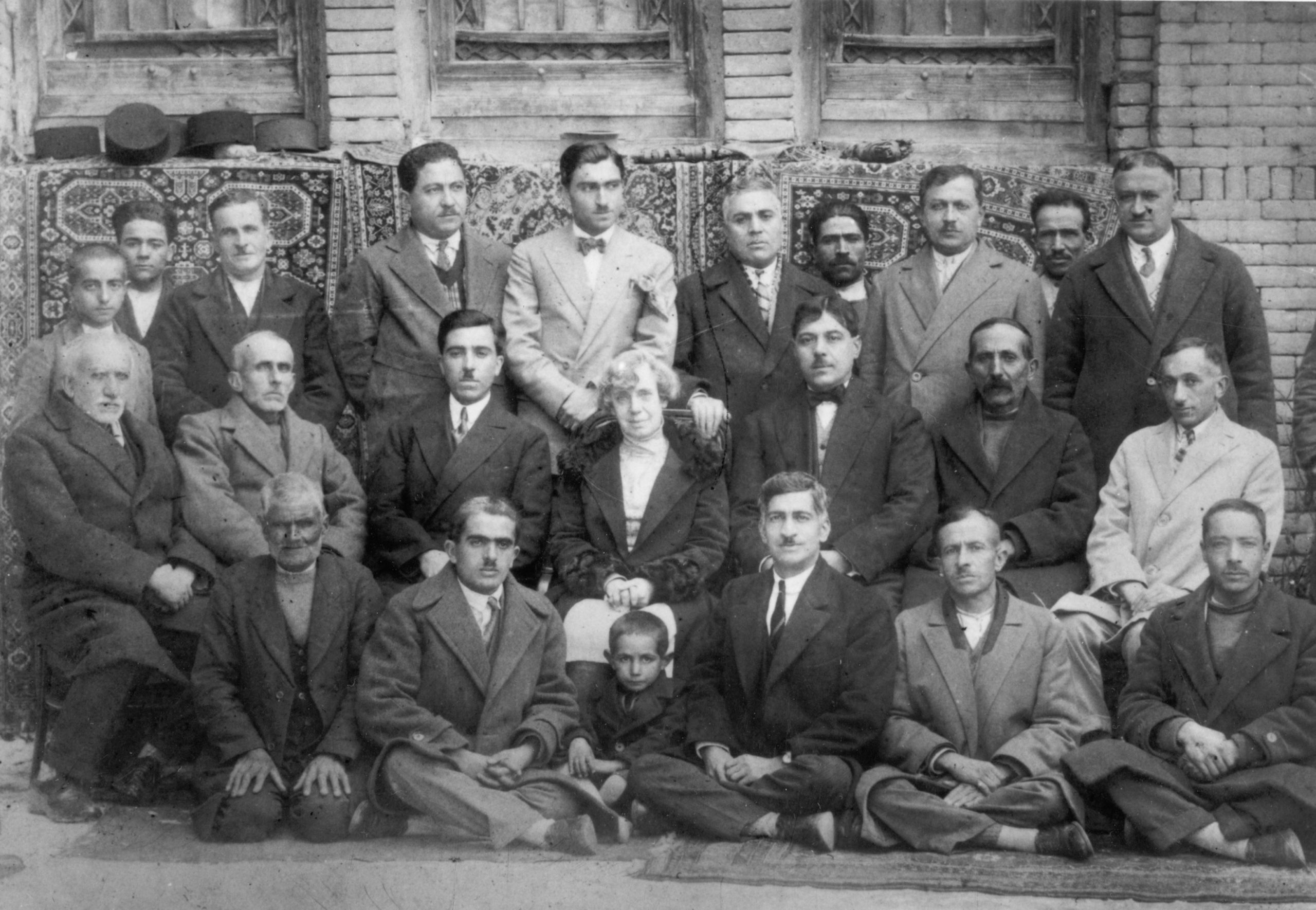

Hand of the Cause Martha Root in Kirmánsháh, Persia, February 1930, standing at the center of the photograph in a white dress. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

Martha Root was one of the handful of Bahá'ís of the Formative Age named by Shoghi Effendi in God Passes By. But the Guardian didn’t just name Martha Root. He would later single her out for “special reference” and proceed to carefully, meticulously, lovingly, pay his foremost teacher of the Faith a five-page-long tribute in God Passes By, the only book he would ever author during his lifetime, a book on the first century of the Faith, a century that was blinded by the radiance of Martha Root’s shining exploits.

Speaking in the present tense of his beloved friend and Hand of the Cause who by the time he was writing God Passes By had been dead four years, Shoghi Effendi states that Martha Root “has covered herself with a glory that has not only eclipsed the achievements of the teachers of the Faith among her contemporaries the globe around, but has outshone the feats accomplished by any of its propagators in the course of an entire century.”

This is so extraordinary it bears repeating.

Martha Root—alone, lowly, and single-handedly—eclipsed the achievements of ALL the Bahá'í teachers of her TIME, and if that was not enough, her feats in teaching the faith outshone those of ANY teachers of the Faith since the birth of the Faith, over the course of the 100 years the Faith has existed.

Martha Root’s service to the Faith is “without parallel in the entire history of the first Bahá'í century.”

The Guardian called described Martha Root as an “immortal heroine,” whose radiant acquiescence to the Head of the Faith, her unflinching obedience and loyalty should not only be considered with pride by current and future generations, but should also be emulated.

Shoghi Effendi gives Martha Root several titles in this tribute, calling her not only the “archetype of Bahá’í itinerant teachers” but also the “foremost Hand raised by Bahá'u'lláh since 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s passing” and “Leading Ambassadress of His Faith” and “Pride of Bahá'í teachers.”

Hand of the Cause Martha Root with a group of women in Melbourne, Australia, around 1924. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

Martha Root was the first person in Bahá'í history to arise and turn 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s Tablets of the Divine Plan into reality, the very year they were unveiled in New York. While scores of Bahá'ís were reading the Tablets and trying to understand them, Martha Root was 6,000 kilometers away, teaching the Faith in Brazil.

Martha Root forgot about herself, her body, her mind, her comfort. For 20 years, she constantly circled the globe, traveling around the world FOUR TIMES. She visited China four times, India three times, visited every important city in South America, and shared the Bahá'í message with the entire world, indiscriminately.

Hand of the Cause Martha Root at the English Literary Society in Beijing, China, c. 1937. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

Martha Root taught intellectuals, and people who were illiterate. She taught formally and informally to royalty and beggars. She brought her message to kings, queens, princes and princesses, presidents of republics, ministers and statesmen, publicists, professors, clergymen and poets.

She attended countless religious and social congresses, was a member of countless peace societies, Esperanto associations, Theosophical societies, and women's clubs.

Shoghi Effendi made an astounding statement. That by virtue of the character of her teaching, her selflessness and sacrificial uninterrupted efforts and the caliber of her victories, she set a record “that constitutes the nearest approach to the example set by `Abdu'l-Bahá Himself to His disciples in the course of His journeys throughout the West.”

According to Shoghi Effendi, Martha Root’s teaching, in its style and results was the closest any person had ever come to the example set by 'Abdu'l-Bahá. That is a phenomenally mind-blowing thing to think about when thinking about Martha Root.

Martha Root made an impression on royalty and world leaders. Prince Paul and Princess Olga of Yugoslavia invited her to the Royal Palace in Belgrade three times. During her 3-month stay in Geneva in 1932, she met with the statesmen of more than 50 countries. She presented books to learned personalities and kept in touch with them through a vast correspondence.

One of Martha Root’s distinguishing features was her stamina. She delivered lectures to 400 universities worldwide, visiting all the universities in Germany not once, but TWICE, and visiting 100 colleges and universities in China.

She was also an indefatigable writer and radio personality. It would be unfeasible to count the number of articles she published in newspapers and magazines in practically every country she visited, nor the radio interviews she gave.

Taking her cue from her beloved Guardian, Martha Root placed emphasis in her travels on placing countless books in private and state libraries worldwide. She also supervised the translation and publication of a large number of versions of Bahá'u'lláh and the New Era.

Martha Root visited the Holy Places of Bahá'u'lláh’s life. She went on pilgrimage to Iran and visited the sites associated with the martyr heroes of the Heroic Age of the Faith. She also traveled to Edirne, searching out the houses of Bahá'u'lláh.

She also lent a helping hand to fledgling Bahá'í institutions around the world.

Hands of the Cause Agnes Alexander (left) and Martha Root (right) in Japan, c. 1930. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

No less impressive is the list of the names of those whom she interviewed in the course of the execution of her mission, including, in addition to those already mentioned, such royal personages and distinguished figures as King Haakon of Norway;

- King Feisal of Iraq;

- King Zog of Albania and members of his family;

- Princess Marina of Greece (now the Duchess of Kent);

- Princess Elizabeth of Greece;

- President Thomas G. Masaryk of Chechoslovakia

- President Eduard Benes of Czechoslovakia;

- The President of Austria;

- Sun Yat Sen, Chinese revolutionary statesman, physician, and political philosopher;

- Nicholas Murray Butler, President of Columbia University;

- Professor Bogdan Popovitch of Belgrade University;

- The Foreign Minister of Turkey, Tawfíq Rushdí Bey;

- The Chinese Foreign Minister and Minister of Education;

- The Lithuanian Foreign Minister;

- Prince Muhammad-`Alí of Egypt;

- Stjepan Radić, a Croat politician and founder of the Croatian People's Peasant Party;

- The Maharaja of Patiala;

- The Maharaja of Benares;

- The Maharaja of Travancore;

- The Governor and the Grand Muftí of Jerusalem;

- Erling Eidem, Archbishop of Sweden;

- Sarojini Naidu, Sarojini Naidu was an Indian political activist and poet who served as the first Governor of United Provinces, after India's independence;

- Sir Rabindranath Tagore, a Bengali polymath who was active as a poet, writer, playwright, composer, philosopher, social reformer, educationist and painter during the age of Bengal Renaissance;

- Madame Huda Sha'raví, the Egyptian feminist leader;

- K. Ichiki, minister of the Japanese Imperial Household;

- Tetrujiro Inouye, Professor Emeritus of the Imperial University of Tokyo;

- Baron Yoshiro Sakatani, member of the House of Peers of Japan;

- Mehmed Fuad, Doyen of the Faculty of Letters and President of the Institute of Turkish history.

Hand of the Cause Martha Root with a group of Bahá’ís in Bombay (now Mumbai), India, 1937. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

Martha Root had 6 private audiences with Queen Marie of Romania—in 1926, 1927, 1929, 19302, 1933, and 1934—meetings during which Martha Root shared the Holy Writings of Bahá'u'lláh, taught Queen Marie his teachings, and gave the Queen small, thoughtful, humble gifts.

In his tribute to Martha Root, Shoghi Effendi kept Martha Root’s crowning achievement for last:

Of all the services rendered the Cause of Bahá'u'lláh by this star servant of His Faith, the most superb and by far the most momentous has been the almost instantaneous response evoked in Queen Marie of Rumania to the Message which that ardent and audacious pioneer had carried to her during one of the darkest moments of her life, an hour of bitter need, perplexity and sorrow. "It came," she herself in a letter had testified, "as all great messages come, at an hour of dire grief and inner conflict and distress, so the seed sank deeply."

Hand of the Cause Martha Root (center) with a group of Bahá’ís in Tabríz, Iran, May 1930. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

Nothing could get Martha Root down. Nothing, in Shoghi Effendi’s words, “could damp the zeal or deflect the purpose of this spiritually dynamic and saintly woman.”

She was the incarnation, the embodiment of one of 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s most fervent desires, and most often-repeated prayers:

O that I could travel, even though on foot and in the utmost poverty, to these regions, and, raising the call of “Yá Bahá’u’l-Abhá” in cities, villages, mountains, deserts and oceans, promote the divine teachings! This, alas, I cannot do. How intensely I deplore it! Please God, ye may achieve it.

She was the incarnation of Bahá'u'lláh’s most famous teaching advice:

Be unrestrained as the wind, while carrying the Message of Him Who hath caused the Dawn of Divine Guidance to break. Consider, how the wind, faithful to that which God hath ordained, bloweth upon all the regions of the earth, be they inhabited or desolate. Neither the sight of desolation, nor the evidences of prosperity, can either pain or please it. It bloweth in every direction, as bidden by its Creator.

Hand of the Cause Martha Root with a group of Bahá’í in Hamadan, Iran, around 1930. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

'Abdu'l-Bahá’s dearest wish in His Will and Testament was this:

O ye the faithful loved ones of ‘Abdu’l‑Bahá! It is incumbent upon you to take the greatest care of Shoghi Effendi, the twig that hath branched from and the fruit given forth by the two hallowed and Divine Lote-Trees, that no dust of despondency and sorrow may stain his radiant nature, that day by day he may wax greater in happiness, in joy and spirituality, and may grow to become even as a fruitful tree.

Many Bahá'ís failed, and many Covenant-breakers. stained Shoghi Effendi’s radiant nature with the dust of despondency and sorrow. Martha Root was one of the only Bahá'ís who made 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s dreams and instructions a reality, fulfilled the Guardian’s most ardent hopes and desires and brought him countless victories, illuminating his radiant nature day by day. Through Martha Root’s exploits, Shoghi Effendi saw what the world could be like if one person was truly enkindled.

Martha Root helped the Guardian wax greater in happiness, in joy and spirituality.

The unstoppable Martha Root (1876 – 1939). Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

Nothing stopped Martha Root. Not age—when she turned 50, or 60—not when she was ill, not when she was diagnosed with cancer, not when the only available Bahá'í literature was inadequate, or non-existent, not her meager resources, not the extremes of weather she encountered, not wars or conflicts.

Martha Root had first been diagnosed with breast cancer in 1912, which had then been in remission for 9 years, and began causing her great pain again in 1921. This cancer became Martha Root’s nemesis in her service. It caused her recurrent pain and debilitating weariness, By 1933, the cancer was advancing and causing Martha Root pain in her head and neck. The merciless progression of the cancer caused lesions Martha Root’s paper-thin and she was in excruciating pain shortly before he passing.

She was felled in her path in Honolulu, Hawaii, on 28 September 1939, succumbing to the breast cancer she had fought for 27 years.

There in that symbolic spot between the eastern and western Hemispheres, in both of which she had labored so mightily, she died, on September 28, 1939, and brought to its close a life which may well be regarded as the fairest fruit as yet yielded by the Formative Age of the Dispensation of Bahá'u'lláh.

Aziz Yazdi (seated left) with Hand of the Cause Martha Root (center) and Esperanto students, Cairo, Egypt. Aziz Yazdi was the brother of ‘Alí Yazdí, Shoghi Effendi’s childhood friend. He was born in Egypt and later served as one of the inaugural Counselor members of the International Teaching Centre from 1973 to 1988. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

When Princess Olga of Yugoslavia—who had entertained Martha Root three times—heard of her passing, she paid her a genuinely touching tribute of love and friendship:

I am deeply distressed to hear of the death of good Miss Martha Root, is the royal tribute paid to her memory by Princess Olga of Yugoslavia, on being informed of her death, as I had no idea of it. We always enjoyed her visits in the past. She was so kind and gentle, and a real worker for peace. I am sure she will be sadly missed in her work.

Hand of the Cause Martha Root with a group of Bahá’ís in Karachi, Pakistan, July 1938. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

The day Martha Root died, Shoghi Effendi was very sick with Phlebotomus fever and he was burning with a high temperature of 40 degrees Celsius. Rúḥíyyih Khánum received the news of Martha Root’s passing and could not withhold it from the Guardian, because it was Martha Root, his fearless, heroic partner in the field of service for 18 long and victorious years, and in Shoghi Effendi’s own words, the "leading ambassadress of Bahá'u'lláh's Faith."

When Shoghi Effendi was informed, he listened to no one, sat up in bed, extremely pale, very weak, and terribly upset by the sudden news, and dictated a long cable to America announcing Martha Root’s passing.

The entire Bahá'í world was waiting to hear what the Guardian had to say.

The Guardian’s touching tribute to his most beloved spiritual foot soldier was sent 4 days after her passing on 2 October 1939 to the Bahá'ís of the world. It was in this message that the Guardian raised Martha Root to the rank of Hand of the Cause and called her “The Foremost Hand which 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s Will has raised in the first Bahá'í Century”:

Martha’s unnumbered admirers throughout Bahá’í world lament with me earthly extinction her heroic life. Concourse on high acclaim her elevation rightful position galaxy Bahá’í immortals. Posterity will establish her as foremost Hand which ‘Abdu’l-Bahá Will has raised up first Bahá’í century. Present generation her fellow-believers recognize her first finest fruit formative age faith Bahá’u’lláh has as yet produced. Advise hold befitting memorial gathering temple honor one whose acts shed imperishable luster American Bahá’í community. Impelled share with national assembly expenses erection monument symbolic spot meeting-place East West to both which she unsparingly dedicated full force mighty energies.

This is a dual story of the invulnerability of the Guardian and the Bahá'í Faith to Covenant-breaking, and a cautionary tale on how Covenant-breaking can manifest itself in an instant.

On the night of 22 January 1940 a man, born and raised in the Faith for many years, walked into the house of 'Abdu'l-Bahá.

He entered a Bahá'í and left a Covenant-breaker.

He had flatly refused to obey the Guardian.

When he left, he stood at the gate of the house for a long time.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum wanted to cry out to him:

Do you leave your soul behind so easily?

During the Guardianship, it was the Bahá'ís only salvation to follow the Guardian through thick and thin, to cleave to him through heaven and hell, through dark or light, but some individuals, out of arrogance, ego, or jealousy, could not obey and put their souls in mortal danger.

Bahá'u'lláh, 'Abdu'l-Bahá, and the Guardian had all suffered from the perversity of Covenant-breakers and their innate disobedience, from their attacks, but they protected the Faith and the body of the believers through their action and their invulnerability.

This doesn’t mean that Covenant-breaking did not affect them. When someone was weak in the Covenant, they physically attacked the very body of the Head of the Faith. It was not an emotional reaction at all, it was physical.

In the Guardian’s case, Rúḥíyyih Khánum describes its organic effect on him as that of a poison. The Guardian recovered, but it caused him untold suffering, just as the Master had described Himself in His Will and Testament as a “broken-winged bird.”

But the Guardian of the Faith and the Cause of Bahá'u'lláh were never permanently affected by individual Covenant-breakers, not even when they launched full-scale attacks. In fact, every attack made the Head of the Faith more resilient. The Covenant-breakers were engaged in a forever-losing battle. Light would always overcome.

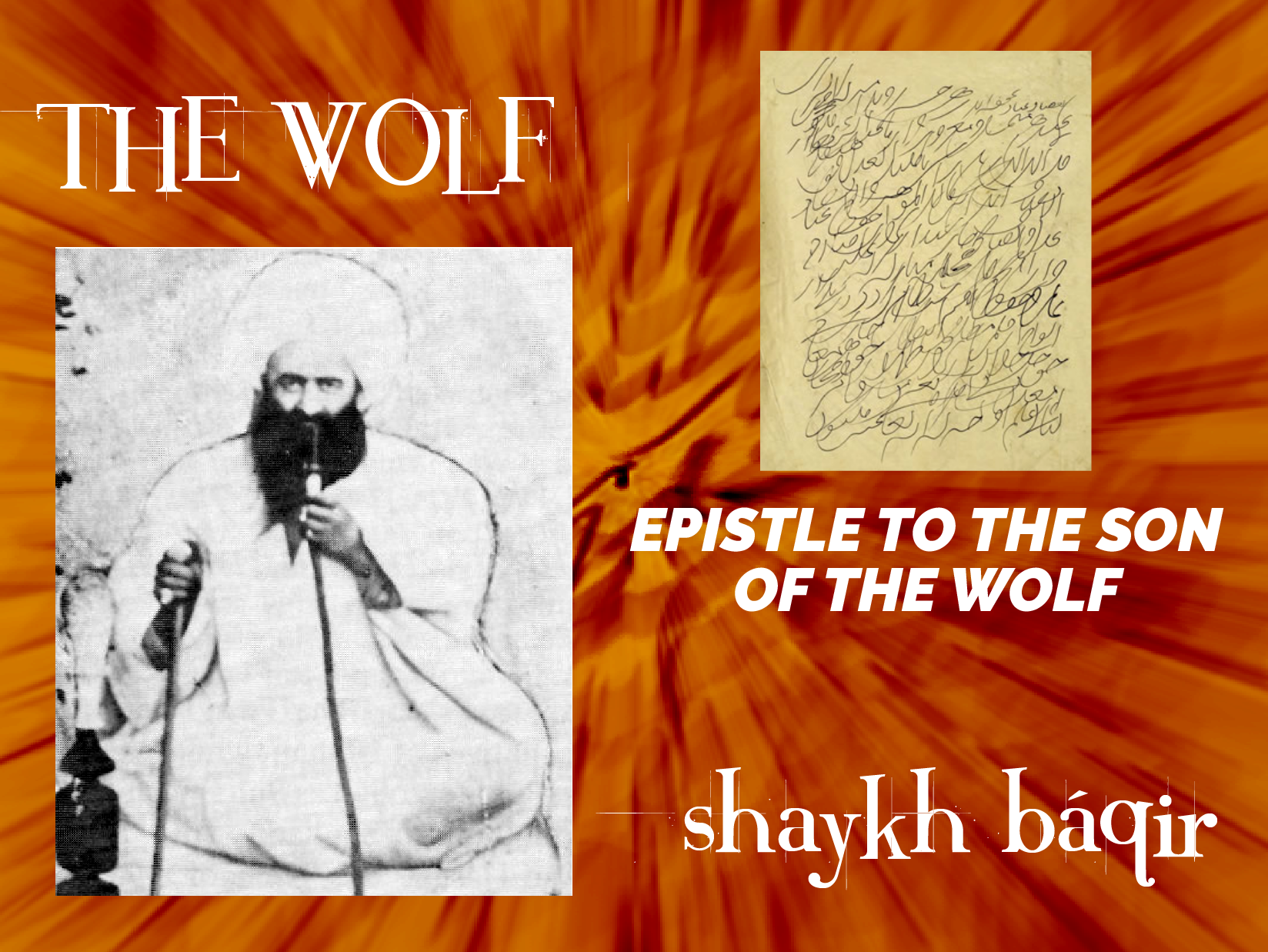

Shaykh Muḥammad-Taqí, known as Áqá Najafí, and addressed to as the “Son of the Wolf,” of the sons of Shaykh Báqir (the Wolf), responsible for the deaths of the King and Beloved of martyrs. Source: Wikimedia Commons. Leaf from Lawḥ-i-Ibn-i-Dhi’b (The Epistle to the Son of the Wolf), addressed to this same Shaykh, in the "Revelation" handwriting of Mírzá Áqá Ján, Bahá’u’lláh’s amanuensis. Source: The Life of Bahá'u'lláh: A Photographic Narrative, © Bahá'í International Community.

L

Lawḥ-i-Ibn-i-Dhi’b (Epistle to the Son of Wolf) was Bahá'u'lláh’s last major work, revealed in the last full year of His life, sometime between February and July 1891, while He was living in the Mansion of Bahjí. In the 181 pages of this challenging and sublime Epistle, Bahá'u'lláh calls on an inveterate enemy of the Faith and one of His most formidable opponents, Shaykh Muḥammad-Taqí, known as Áqá Najafí, the “son of the Wolf.”

The Wolf himself was Muhammad-Báqir, responsible for the deaths of the King and Beloved of Martyrs. His son, Shaykh Muḥammad Taqí, not only supported his father’s monstrous, tyrannical acts, but was often willing to participate in the execution of his father’s oppressive religious decrees.

In Epistle to the Son of the Wolf, Bahá'u'lláh calls on the Shaykh to repent for his role in the persecution and massacre of Bahá'ís, frequently quoting from some of the most celebrated passages from His own Writings, and establishing the incontrovertible truth of the Bahá'í Faith. In one particularly moving passage, Bahá'u'lláh gives Áqá Najafí the words to beg God's forgiveness for his wicked deeds:

Alas, alas, for my waywardness, and my shame, and my sinfulness, and my wrong-doing...alas, alas! and again alas, alas! for my wretchedness and the grievousness of my transgressions!

The Shaykh was absolutely furious when he received Bahá'u'lláh’s Tablet.

The Guardian’s translation of Lawḥ-i-Ibn-i-Dhi’b—Epistle to the Son of the Wolf—begun in the winter of 1939-1940, one of the most dangerous periods of his life. It would be his fifth and last book of translations of the Writings of Bahá'u'lláh, and the Guardian mailed it to America for publication shortly before leaving for Europe in the May 1940.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum described Epistle to the Son of the Wolf has having a special place of its own among the Bahá'í Holy Writings, something supported by a cable Shoghi Effendi sent to the Bahá'ís of the United States and Canada on 26 November 1940 regarding his hopes for the study of this book:

Translation Epistle Son Wolf completed; mailing remainder manuscript. Devoutly hope its study may contribute further enlightenment deeper understanding verities on which effectual prosecution teaching administrative undertakings ultimately depends. Deepest love.

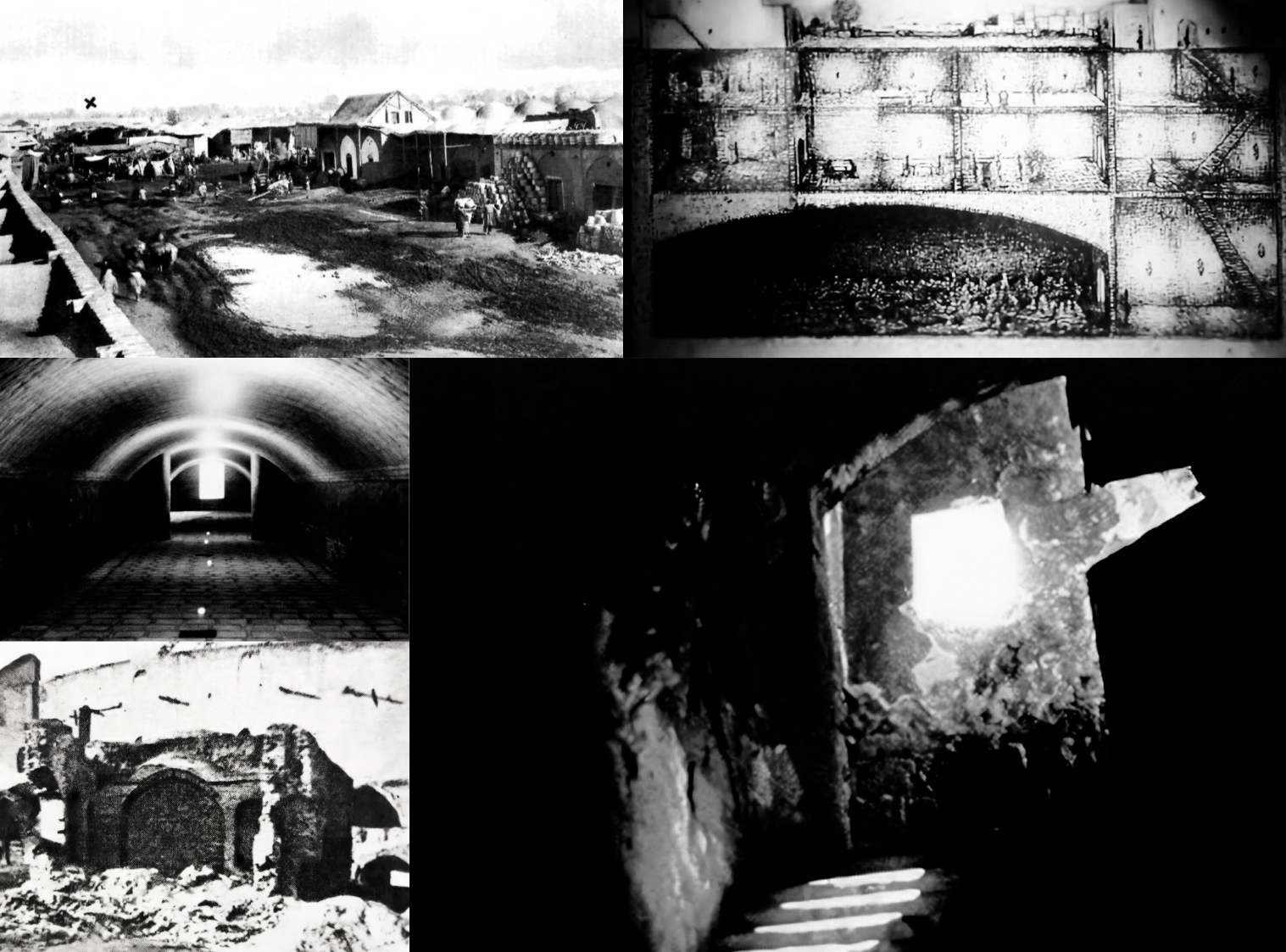

The Síyáh-Chál (Black Pit) the unspeakably horrific underground water cistern-turned-dungeon in which Bahá'u'lláh was kept for four freezing winter months between August and December 1952, and of which He speaks in the excerpt from the Epistle to the Son of the Wolf in the story below. The images are from left to right in the top row: The location of the Síyáh-Chál in the southern part of Ṭihrán where criminals and murderers were executed. (The Dawn-Breakers) and an engraving depicting a section of the Síyáh-Chál. (Bahá'í Historical Facts). On the left side of the image, top and bottom pictures: Inside the Síyáh-Chál (Supporting the Core Activities) and the outside entrance of the Síyáh-Chál (Wikimedia Commons). Large image on the right: Entrance to the Síyáh-Chál, showing the steps leading to the underground cistern, steps which 'Abdu'l-Bahá, then 8 years old began descending before Bahá'u'lláh saw Him and stopped Him. (Bahá'í Historical Facts).

Here is perhaps one of the most achingly beautiful paragraphs—rendered into luminous English by Shoghi Effendi—from Epistle to the Son of the Wolf:

During the days I lay in the prison of Ṭihrán, though the galling weight of the chains and the stench-filled air allowed Me but little sleep, still in those infrequent moments of slumber I felt as if something flowed from the crown of My head over My breast, even as a mighty torrent that precipitateth itself upon the earth from the summit of a lofty mountain. Every limb of My body would, as a result, be set afire. At such moments My tongue recited what no man could bear to hear.

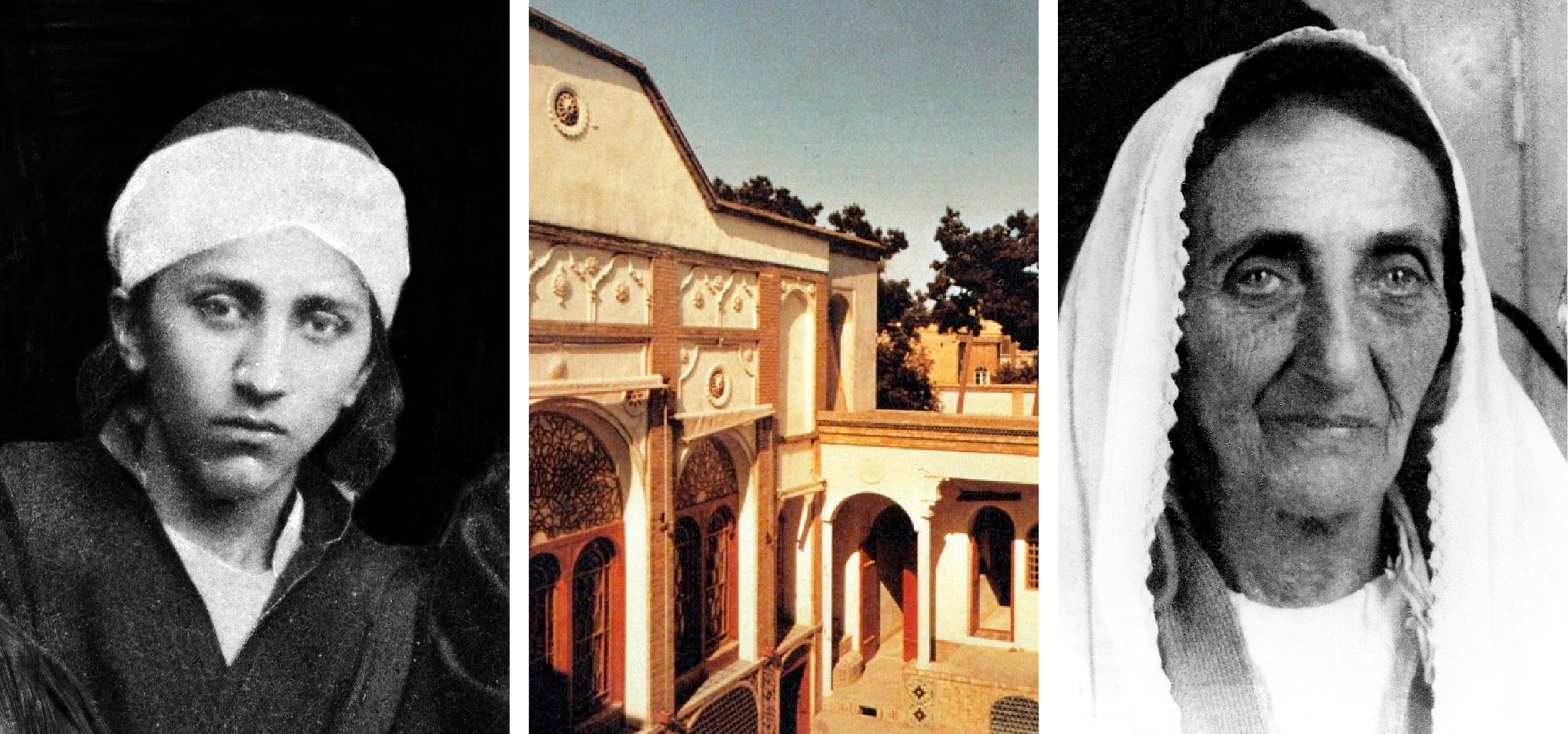

In order of their passings, Mírzá Mihdí, who was martyred at the age of 22 on 23 June 1870 when he fell from an open skylight in the barracks roof of the Most Great Prison in 'Akká. (Bahá'í Media Bank) Ásíyih Khánum, passed away in the House of ‘Abbúd in 'Akká at the age of 66 in 1886, after falling from a great height. There are no photographs of Ásíyih Khánum so an image of the first house where she lived when she was married with Bahá'u'lláh is used in place, it is the house of Mírzá Buzurg, Bahá'u'lláh’s father. Ásíyih Khánum (Uplifting Words). And lastly, Bahíyyih Khánum, the Greatest Holy Leaf, who passed away at the age of 86 on 15 July 1932 in Haifa (Bahá'í Media Bank).

Mírzá Mihdí, Bahá'u'lláh and Ásíyih Khánum’s youngest son had died on 23 June 1870 after falling through a skylight in the Most Great Prison. Sixteen years later, his mother, Ásíyih Khánum, died after a fall from a great height in the House of Abbúd, in 1886. Both Mírzá Mihdí and Ásíyih Khánum were buried in two different Arab cemeteries in 'Akká.

On 15 July 1932, Bahíyyih Khánum, the Greatest Holy Leaf, the daughter of Bahá'u'lláh and Ásíyih Khánum, passed away in Haifa, at the age of 86.

Shoghi Effendi was in Switzerland when the Greatest Holy Leaf passed away, and he immediately left for Italy where he ordered a breathtaking monument made out of marble: a round stepped base, on which columns rested, topped by a beautiful dome.

The Greatest Holy Leaf was the only member of Bahá'u'lláh’s and 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s family to have been befittingly buried on Mount Carmel with a monument above her grave.

It had been the Greatest Holy Leaf’s cherished desire, for many years, to be buried close to her mother.

The Monument Gardens in the late 1930s, the two monuments for Ásíyih Khánum and Mírzá Mihdí are to the left of the photograph, similar in style to the monument for the resting place of Bahíyyih Khánum, the Greatest Holy Leaf, which is on the right. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

The Guardian set out to remedy these situations—to befittingly bury the Holy Family together, and for the Greatest Holy Leaf to rest close to her saintly mother.

Re-interring the remains of Ásíyih Khánum and Mírzá Mihdí had been a long and profoundly cherished hope for Shoghi Effendi, and he had conceived an elegant plan to re-inter their remains very close to those of the Greatest Holy Leaf. In this way, the remains of the family of Bahá'u'lláh and 'Abdu'l-Bahá would be befittingly laid to rest, and the Greatest Holy Leaf’s cherished desire of resting close to her mother would be fulfilled.

In 1939, Shoghi Effendi ordered two monuments similar in style to the marble monument of the Greatest Holy Leaf.

As with every single thing the Guardian had ever, or would ever create, the monuments he ordered in Italy for the tombs of Mírzá Mihdí and Navváb were exquisite and their sense of proportion absolutely impeccable.

Italian stonemasons carved out the different pieces of the monument out of white Carrara marble according to the specific instructions of Shoghi Effendi.

Despite World War II, the monuments reached Haifa safely.

Column detail from the Monument Gardens, processed to represent an architectural drawing. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

Unsurprisingly, given everything he accomplished, Shoghi Effendi was a very tenacious person. He was profoundly determined, resolute, persistent, relentless, but he was never unreasonable. That is a very important factor to keep in mind.

The Guardian never changed the objectives he set for himself.

But he could change the course, the direction, the path to reach them.

A good example is the objective that the Guardian set himself of moving the remains of Ásíyih Khánum and Mírzá Mihdí from 'Akká to Haifa and interring them on Mount Carmel near the resting place of Bahíyyih Khánum.

Initially, the Guardian intended to put Ásíyih Khánum and Mírzá Mihdí on either side of the monument for the Greatest Holy Leaf, and, as he was absent from Haifa, he requested architectural drawings of this placement to be made.

When Shoghi Effendi returned to Haifa, he looked at the drawings, and didn’t like the harmony. Immediately, on the spot, he decided to place Ásíyih Khánum and Mírzá Mihdí together, as a pair by themselves but on the same axis as the monument to the Greatest Holy Leaf.

The objective never changed, but Shoghi Effendi altered course, aided by his never-failing intuition and inspiration.

Gate entrance to the Monument Gardens. In the picture above, you can see the monuments of Ásíyih Khánum and Mírzá Mihdí past the gate from above. From this vantage point, the monument of the Greatest Holy Leaf is on your right, and the monument of Munírih Khánum is also on your right but lower on Mount Carmel than those of the Greatest Holy Leaf and Ásíyih Khánum and Mírzá Mihdí. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

Shoghi Effendi was working on two fronts: in Haifa and in 'Akká.

In Haifa, Shoghi Effendi was directing workers to excavate the location of the new tombs of Ásíyih Khánum and Mírzá Mihdí on Mount Carmel.

In 'Akká, he was organizing the exhumation of the graves of 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s mother and brother. During this process, the Covenant-breakers had the gall to protest to the authorities that they were relatives of the deceased. The civil authorities, immediately upon learning that these Covenant-breakers had been the arch-enemies of 'Abdu'l-Bahá and His family, issued the necessary paperwork to Shoghi Effendi for the exhumation of the bodies.

Two days after receiving official permission, Shoghi Effendi arrived in 'Akká at dawn, removed the Purest Branch and Navváb from the cemetery, one after the other, broke open the caskets, gently and reverently placed the remains into new caskets, loaded them in the car, and brought the remains with them to Haifa. This took many hours and was a nerve-racking ordeal at every step of the way because of the very real dangers that the Covenant-breakers would show up and decide to forcibly prevent the exhumation.

When they had dug up the grave of Ásíyih Khánum, they found that the wood of the coffin was still intact aside from the bottom part. When they removed the top at Shoghi Effendi’s instruction, the face of Bahá'u'lláh’s wife’s was so clearly outlined by her burial shroud that one could almost see her features, but it disintegrated into dust at the first touch.

At dusk that night, a group of men waited by the gate beneath the steps of a small house close to the resting-place of the Greatest Holy Leaf. The Guardian arrived, assisted by pall-bearers, carrying the casket of Mírzá Mihdí on their shoulders.

The casket containing its precious trust was placed in a room, prepared with a rug and a candelabra from the Holy Shrines, and was placed facing Bahjí and the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh.

Shoghi Effendi and the men returned to the car to retrieve the coffin containing the sacred remains of Ásíyih Khánum, and placed it next to the casket of Mírzá Mihdí in the room. The remains of Munírih Khánum were also re-interred at this time.

As soon as the holy remains of Ásíyih Khánum and Mírzá Mihdí were safe in Haifa, the Guardian sent a cable to the Bahá'í World on 5 December 1939:

Blessed remains Purest Branch and Master's mother safely transferred hallowed precincts Shrines Mount Carmel. Long inflicted humiliation wiped away. Machinations Covenant-breakers frustrate plan defeated. Cherished wish Greatest Holy Leaf fulfilled. Sister brother mother wife 'Abdu'l-Bahá reunited one spot designed constitute focal centre Bahá'í Administrative Institutions at Faith's World Centre. Share joyful news entire body American believers.

Column detail from the monuments of Ásíyih Khánum and Mírzá Mihdí. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

The precious remains of Mírzá Mihdí and Ásíyih Khánum would lay in the house on Mount Carmel for three weeks while Shoghi Effendi made all the necessary preparations for their re-interment.

Shoghi Effendi had two vaults built next to each other, their floor paved in marble and carpeted. Once the vaults were ready, on 24 December 1939, the coffins were reverently carried to their place of burial held aloft on the hands of faithful Bahá'ís, Shoghi Effendi leading the procession, never once laying his burden down.

Both coffins circumambulated around the Shrines of the Báb and 'Abdu'l-Bahá before being placed in their vaults. Shoghi Effendi himself entered the carpeted vault of Mírzá Mihdí and eased the coffin to its perfect, planned position. It was Shoghi Effendi himself who strew flowers on the casket, and his hands were the last to touch it.

The Guardian did the same for the casket of Ásíyih Khánum in the neighboring vault.

Masons were called in to seal the tombs, flowers were heaped on the vaults and Shoghi Effendi sprinkled a vial of attar of rose, and chanted the Tablets of Visitation revealed by Bahá'u'lláh for His wife and His son, which are to be read at their graves.

Three weeks after the remains of Navváb and the Purest Branch had reached Haifa, Shoghi Effendi announced to the world two days later, on 26 December 1939 that they had finally been befittingly interred near the tomb of Bahíyyih Khánum:

Christmas eve beloved remains Purest Branch and Master's mother laid in state Bab's Holy Tomb. Christmas day entrusted Carmel's sacred soil. Ceremony presence representatives Near eastern believers profoundly moving. Impelled associate America's momentous Seven Year enterprise imperishable memory these two holy souls who next twin founders Faith and perfect Exemplar tower together with Greatest Holy Leaf above entire concourse faithful. Rejoice privilege pledge thousand pounds my contribution Bahíyyih Khanum Fund designed inauguration final drive insure placing contract next April last remaining stage construction Mashriqu’l-Adhkár. Time pressing opportunity priceless potent aid providentially promised unfailing.

A modern photograph of the monuments for Ásíyih Khánum and Mírzá Mihdí. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

The monuments for the resting places of Ásíyih Khánum and Mírzá Mihdí were constructed in the two months between 24 December 1939 and February 1940, and the Guardian dedicated them on 9 February 1950, which in the Muslim calendar is 1 Muharram, the Muslim date on which the Báb was born in 1817.

On 9 February 1950, the Guardian gathered all the petals from the Shrines of the Báb and 'Abdu'l-Bahá, and spread them on two big white sheets. The sheets were then taken to the tombs and spread over the monuments. With great tenderness, Shoghi Effendi placed a rose over each tomb, then chanted their Tablets of Visitation.

After this ceremony, the Guardian walked to the resting place of the Greatest Holy Leaf and recited the Tablet of Visitation in her honor, before sharing verses from Isaiah 54 referring to Ásíyih Khánum. Many times, 'Abdu'l-Bahá had said that the entirety of Isaiah was dedicated to Ásíyih Khánum and verse 2 reads:

Thy Maker is thine husband; the Lord of hosts is His name.

The buildings on the Arc, showing how they are centered on the Monument Gardens, with paths radiating from the resting places of the family of 'Abdu'l-Bahá: His beloved saintly sister, the Greatest Holy Leaf, His mother, Ásíyih Khánum, His martyred younger brother, Mírzá Mihdí, and His wife, Munírih Khánum. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

For many years before 1940, Shoghi Effendi had envisioned a “focal centre,” as he called it, of the mightiest instructions of the Faith. His vision was that the Universal House of Justice and its agencies would be erected around this center and above the Shrine of the Báb on Mount Carmel.

This spot, as conceived by Shoghi Effendi, was the place where the mother, sister and brother of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, those "three incomparably precious souls," as he called them, were laid to rest, souls, who he stated categorically "next to the three Central Figures of our Faith, tower in rank above the vast multitude of the heroes, Letters, martyrs, hands, teachers and administrators of the Cause of Bahá'u'lláh."

The gardens where the remains of Bahíyyih Khánum, Ásíyih Khánum, Mírzá Mihdí, and Munírih Khánum are laid to rest are known by the name of “Monument gardens.”

It is around the Monument Gardens that all the world’s international Bahá'í Institutions at the World Center are centered: the International Teaching Centre, the Universal House of Justice, the Center for the Study of the Texts and the International Bahá'í Archives.

May Maxwell with her niece Jeanne Negar Bolles (later Chute), probably in Rio de Janeiro in February 1940. Source: The Maxwells of Montreal: Middle Years 1923-1937 Late Years 1937-1952. Violette Nakhjavani, Kindle Edition, Location 7234.

May Maxwell was serving and teaching the Faith incessantly, but she wanted more, she longed to give more of herself, expend more of her means, and her physical energies for her beloved Cause. She found a way to express her undying love for the Guardian at the height of the First Seven Year Plan, and decided to travel to Argentina for a few months. She asked her daughter, Rúḥíyyih Khánum if the Guardian would approve, and Rúḥíyyih Khánum responded on 13 December 1939:

Guardian heartily approves winter visit Buenos Aires providing Daddy and physician consent dearest love both, Rúhíyyih Rabbání.

On 22 January 1940, Shoghi Effendi responded with two separate cables to a message from May Maxwell announcing her departure in two days’ time:

Proud noble resolve prayers accompany you both safeguard health, Shoghi

Profoundly appreciate noble sacrifice dearest love. Shoghi

On 24 January 24 1940, May Maxwell left for her heroic journey, despite her poor health, and sailed to Buenos Aires with her niece, Jeanne Negar Bolles on the S.S. Brazil, and arrived in Buenos Aires, Argentina on 27 February, after more than a month at sea.

May Maxwell woke at 5:00 AM on 1 March 1940, with severe pain in her chest, and had a heart attack at 2:15 PM. She passed away before the doctor arrived.

May Maxwell, shortly before her passing, 1940. Source: The Maxwells of Montreal: Middle Years 1923-1937 Late Years 1937-1952. Violette Nakhjavani, Kindle Edition, Location 7504.

In the Holy Land, Rúḥíyyih Khánum was panicking. Three cables had arrived in quick succession and Rúḥíyyih Khánum handed them to her husband. Rúḥíyyih Khánum describes the shock of her life and a rare intimate moment between her and her husband that she was willing to share in The Priceless Pearl:

As he read them I saw his face change and he looked at me with an expression of intense anxiety and concern. Then of course, gradually, he had to tell me she was dead. I cannot conceive that any human being ever received such pure kindness as I did from the Guardian during that period of shock and grief. His praises of her sacrifice, his descriptions of her state of joy in the next world, where, as he said in his cable to the Iraq National Assembly informing the friends of her death, "the heavenly souls seek blessings from her in the midmost paradise", his vivid depiction of her as she wandered about the Abhá Kingdom making a thorough nuisance of herself because all she wanted to talk about was her beloved daughter on earth! - all combined to lift me into a state of such happiness that many times I would find myself laughing with him over the things he seemed to be actually divining.

Her mother’s sudden death was a terrible shock for Rúḥíyyih Khánum. The two had been indescribably close their whole lives. After the Guardian had broken the awful news to Rúḥíyyih Khánum, he told her with such sweetness: “Now I will be your mother” and comforted her with infinite compassion and patience.

Friends at the funeral of May Maxwell, 13 March 1940, Quilmes, Argentina. Source: The Maxwells of Montreal: Middle Years 1923-1937 Late Years 1937-1952. Violette Nakhjavani, Kindle Edition, Location 7622.

Two days after her death, on 3 March 1940, Shoghi Effendi sent a cable that stunned the Bahá'í world, where he elevated May Maxwell to the rank of Martyr:

‘Abdu’l‑Bahá’s beloved handmaid distinguished Disciple May Maxwell gathered glory Abhá kingdom. Her earthly life so rich eventful incomparably blessed worthily ended. To sacred tie her signal services had forged priceless honour martyr’s death. Double crown deservedly won. Seven Year Plan particularly south American campaign derive fresh impetus example her glorious sacrifice. Southern outpost faith greatly enriched through association her historic resting-place destined remain poignant reminder resistless march triumphant army Bahá’u’lláh. Advise believers both Americas hold befitting memorial gatherings.

On the same day, Shoghi Effendi wrote a deeply touching condolence message to his beloved father-in-law:

Grieved profoundly yet comforted abiding realization befitting one so noble such valiant exemplary service cause Bahá'u'lláh stop Rúhíyyih though acutely conscious irreparable loss rejoices reverently grateful immortal crown deservedly won her illustrious mother stop advise interment Buenos Aires stop her tomb designed by yourself erected by me spot she fought fell gloriously will become historic centre pioneers Bahá'í activity stop most welcome arrange affairs reside Haifa stop be assured deepest loving sympathy. Shoghi

May Maxwell was laid to rest in Quilmes, Argentina.

Committee for May Maxwell Memorial construction. Caption: Wilfrid E. Barton, Salvador Tormo, Mrs. Amelia E. Collins, Emilio Barros, Baha'i Committee representing the National Spiritual Assembly in the construction of the memorial to Mrs. May Maxwell in Quilmes Cemetery, Buenos Aires, with Mariano Viciano, the sculptor chosen to carry out William Sutherland Maxwell's design. Source: Bahaimedia.

After May Maxwell’s martyrdom, Shoghi Effendi cabled William Sutherland Maxwell on 2 March 1940—the day after her passing:

Grieve profoundly yet comforted abiding realization befitting end so noble career valiant exemplary service Cause Bahá'u'lláh. Rúḥíyyih though acutely conscious irreparable loss rejoices reverently grateful immortal crown deservedly won her illustrious mother. Advise interment Buenos Aires. Her tomb designed by yourself erected by me spot she fought fell gloriously will become historic centre pioneer Bahá'í activity. Most welcome arrange affairs reside Haifa. Be assured deepest loving sympathy.

The Guardian’s message was what brought William Sutherland Maxwell to Haifa and to his destiny, his everlasting masterpiece: designing the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb under the guiding hand of the Guardian.

Buenos Aires, Argentina in 1940. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Philip Sprague—a prominent American Bahá'í who would later be appointed to the National Spiritual Assembly—was on pilgrimage shortly after May Maxwell's passing on 1 March 1940. Inspired by May Maxwell's example, Philip had planned to leave Haifa for a teaching trip in South America starting with Buenos Aires, Argentina where he would spend six months.

When he left Haifa, he carried a small box to Buenos Aires, a large Persian silk handkerchief, with still-fragrant flowers wrapped inside. Shoghi Effendi had written Philip a note to lay the bouquet on May Maxwell's grave, along with the contents of an envelope inscribed from Rúḥíyyih Khánum to her mother. Inside the envelop was a tiny, delicate wreath of pressed roses and jasmine flowers.

The Italian liner SS Rex in 1933, 7 years before William Sutherland Maxwell boards it to travel on 11 May 1940 to sail from Montreal to New York before transferring to another Italian vessel bound for Naples. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

After May Maxwell’s martyrdom, on 1 March 1940, Shoghi Effendi invited her grieving husband, Rúḥíyyih Khánum’s father, William Sutherland Maxwell, to leave Montreal as soon as he could settle his affairs and come live with him and Rúḥíyyih Khánum in Haifa. William Sutherland Maxwell would sail from Canada and meet Shoghi Effendi and Rúḥíyyih Khánum in Italy.

William Sutherland Maxwell sailed from Montreal on 11 May 1940 on the S.S. Rex, to New York. In New York City, William Sutherland Maxwell was met by Ugo Giachery and his wife Angeline who assisted him with his transfer from the S.S. Rex to an Italian ship which would sail to Naples, where he would to meet Shoghi Effendi and Rúḥíyyih Khánum.

Ugo and Angeline Giachery accompanied William Sutherland Maxwell to the pier and onto the steamer, asking the ship’s staff to ensure his comfort and pay special attention to him during the sailing.

An American seaplane from 1939, probably quite similar to the Italian seaplane aboard which Shoghi Effendi and Rúḥíyyih Khánum left Haifa on 15 May 1940. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Around the same time as he had invited William Sutherland Maxwell to come and live in Haifa, Shoghi Effendi decided—for reasons unknown, until now, to anyone but himself—to travel to England. The plan was to meet Rúḥíyyih Khánum’s father half-way in Italy.

It is almost impossible to explain how impossible the Guardian’s journey was at that point in history, at that stage in the unfolding World War II. There are no words to convey the impossibility of that trip.

For starters, the Guardian and Rúḥíyyih Khánum, could not get a visa for England in Palestine. Their visa application was forwarded to London, and even though Shoghi Effendi appealed to his old friend Lord Lamington, he and Rúḥíyyih Khánum had to leave the Holy Land without receiving a response, or they would never have been able to leave.

Shoghi Effendi made the decision to leave for Italy, a country for which they were able to obtain a visa. They sailed to Rome on 15 May 1940, in a small and smelly Italian seaplane, with water sloshing under their feet. The journey took several days, from Haifa to Heraklion, in Crete and then on to Reggio, Italy, before arriving in Rome.

A few days after arriving in Rome, Rúḥíyyih Khánum traveled to Genoa to welcome her father, William Sutherland Maxwell, who had sailed in on the S.S. Rex.

In Rome, Sutherland and Rúḥíyyih Khánum went to the British Consul at Shoghi Effendi’s request, but there was no news on their visa applications because communication to London had been interrupted.

When they returned with the news, Shoghi Effendi sent them back to the Consul.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum and Sutherland found themselves sitting across from the Consul again, and Rúḥíyyih Khánum had the inspiration to mention that Shoghi Effendi was the Head of the Bahá'í Faith.

The Consul looked at her and said:

I remember 'Abdu'l-Bahá…

He had met 'Abdu'l-Bahá and was still deeply touched by the encounter twenty years later.

The Consul took their passport, stamped a visa for England in it, and said the act was meaningless, but it was all he could do. They would be entering England at their own risks.

As soon as they had received their visa, Shoghi Effendi, Rúḥíyyih Khánum and William Sutherland Maxwell traveled to France, traveling through Menton on 25 May 1940, and arriving in Marseille.

Italy entered the war a few days later on 10 June 1940, against the Allies.

Nazi soldiers parade on the Champs Élysées on 14 June 1940, at the time when Shoghi Effendi is in Saint-Malo trying to leave, just 400 kilometers away to the west. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Everything that followed was, in Rúḥíyyih Khánum’s own words, “like a brilliantly lit nightmare - a personal nightmare for us and a giant nightmare in which the whole of Europe was involved.”

Shoghi Effendi, Rúḥíyyih Khánum and William Sutherland Maxwell boarded a train to Paris, and were faced, at every station, with the ravages of war. Thousands of refugees were escaping the Allied front in the North, which was quickly disintegrating.

It was absolute chaos.

There were no reliable sources of information.

Once they arrived in Paris, they realized that the only port left from which they could sail to England was in Saint-Malo, in Brittany. When they arrived, they found hundreds of refugees trying to go home, back to England.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum never saw the Guardian in the state he was in during that week in Saint-Malo.

Shoghi Effendi would sit perfectly still, almost like a stone, giving Rúḥíyyih Khánum the impression he was being consumed with suffering from the inside, burning away. The Guardian of the Bahá'í Faith was in war-torn Europe, with nowhere to go. If he fell into the hands of the Nazis, he would be imprisoned or killed, and the Faith would be left leaderless in a time of world chaos.

It was exactly the situation the Faith had been in when 'Abdu'l-Bahá came close to death in 'Akká in 1905. During this time, the Nazi army was marching through France, and no less than 6 million French fled their own country, to avoid falling in German hands. The Nazis were working their way south starting at the French border with Belgium, and time was running out for Shoghi Effendi.

Twice a day, Shoghi Effendi would send Rúḥíyyih Khánum and William Sutherland Maxwell to the boat company in the port, and twice a day, they returned with no news of arriving ships.

Two ships finally arrived in the night of 2 June 1940 to evacuate those stranded in Saint-Malo. Shoghi Effendi, Rúḥíyyih Khánum, and William Sutherland Maxwell boarded the first ship that arrived, sailed in total darkness and arrived the next morning in Southampton.

The Nazis marched into Saint-Malo on 20 June 1940, 18 days after Shoghi Effendi left. They had occupied two-thirds of the territory of France.

Shoghi Effendi, Rúḥíyyih Khánum and William Sutherland Maxwell spent nearly two months in England. They found it was as difficult to leave England as it had been to enter it.

They had arrived in England at a very chaotic time. The government had initiated "Operation Pied Piper” in September 1939, with the aim to evacuate civilians and children into the countryside, and limit innocent casualties. By June and July 1940, "Operation Pied Piper" had expanded to the south and east coasts, because they feared a seaborne invasion.

It was in 1940, while Shoghi Effendi, Rúḥíyyih Khánum, and William Sutherland Maxwell were briefly in London, waiting for ship to sail, that the Guardian first placed an order for vases from the Shrines. This would become a great passion for the Guardian, in the post-War years. The vases were delivered to the Holy Land later on.

A week before Shoghi Effendi sailed from England in July 1940, he had cabled via Haifa (through which all his cables and letters were invariably relayed during his absence from home) in which he faced the world conflict beginning to ravage Europe, but called Bahá'ís to look further, steel their resolve, and never stop the work of the Faith:

Long-predicted world-encircling conflagration essential prerequisite world unification inexorably moving appointed climax. Its fires first lit far east subsequently ravaging Europe enveloping Africa now threaten devastation both near east far west respectively enshrining world center and chief remaining citadel Faith Bahá’u’lláh. Divinely appointed plan must will likewise pursue undeflected predestined course. Time pressing…Refuse believe community so richly endowed greatly envied repeatedly honored will suffer slightest relaxation its resolution jeopardize spiritual prizes painstakingly deservedly won throughout states provinces republics western hemisphere.

After Italy’s entry into the war, the Mediterranean was closed to all Allied vessels. The only way for Shoghi Effendi, Rúḥíyyih Khánum, and William Sutherland Maxwell to return to Haifa was by sailing from England to South Africa, crossing the entire continent of Africa until Egypt, where they could then rejoin the Holy Land.

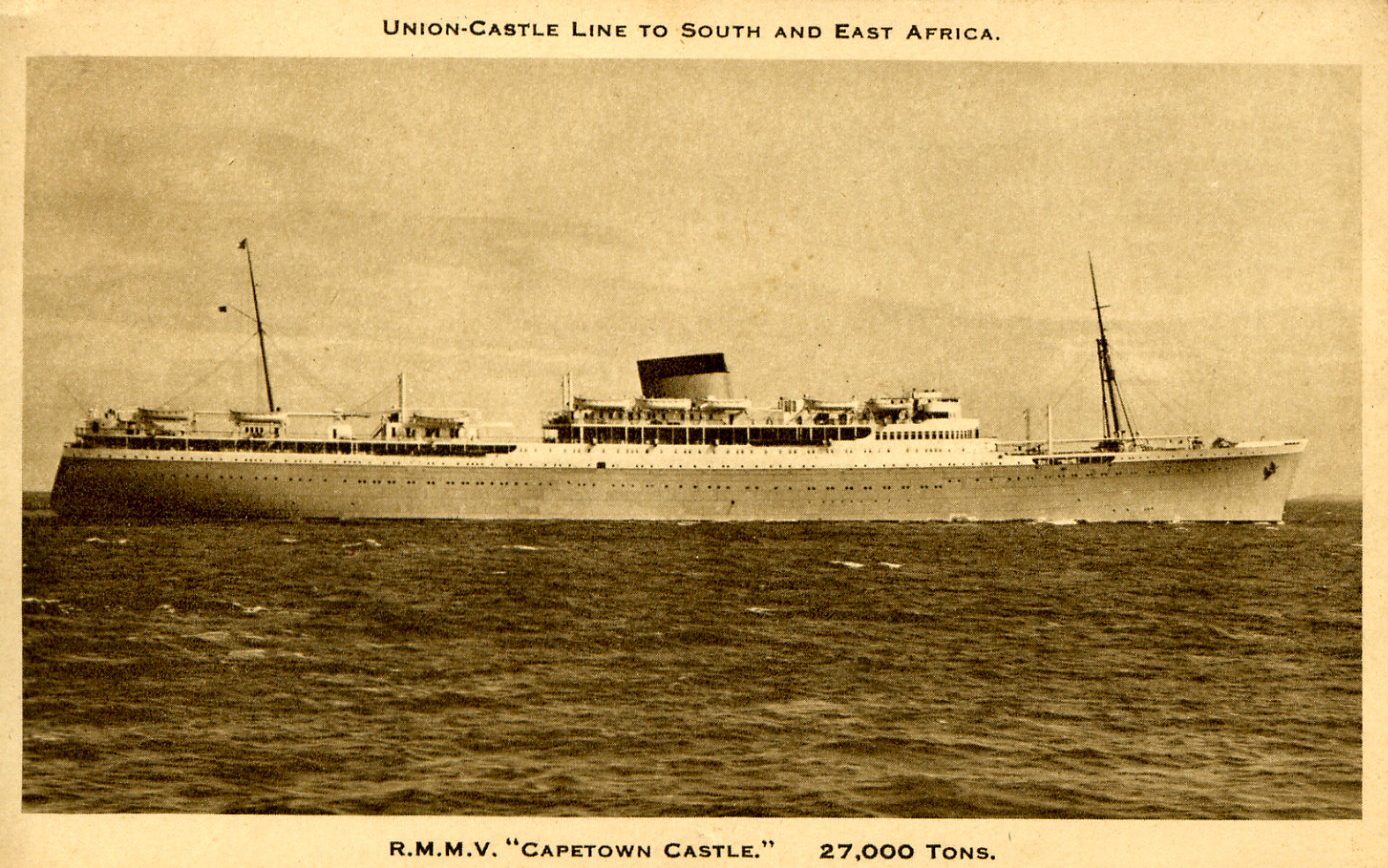

It was only because if the Guardian’s high position, and William Sutherland Maxwell’s friendship with Vincent Massey, the Canadian High Commissioner in London that they managed to get passage on the R.M.M.V. Capetown Castle, and left Europe on 28 July 1940.

It was only because of the Guardian’s high position, and William Sutherland Maxwell’s friendship with Vincent Massey, the Canadian High Commissioner in London that they managed to get passage on the R.M.M.V. Capetown Castle, and left Europe on 28 July 1940.

The Guardian was safe.

He had escaped the first Blitz on London by a month.

The R.M.M.V. Capetown Castle was a fast ship, and it made irregular course changes, to evade any potential German U-boat submarine attacks, leaving in its wake a strange zigzag on the sea.

Shoghi Effendi was returning to Africa, for the second time in his life.

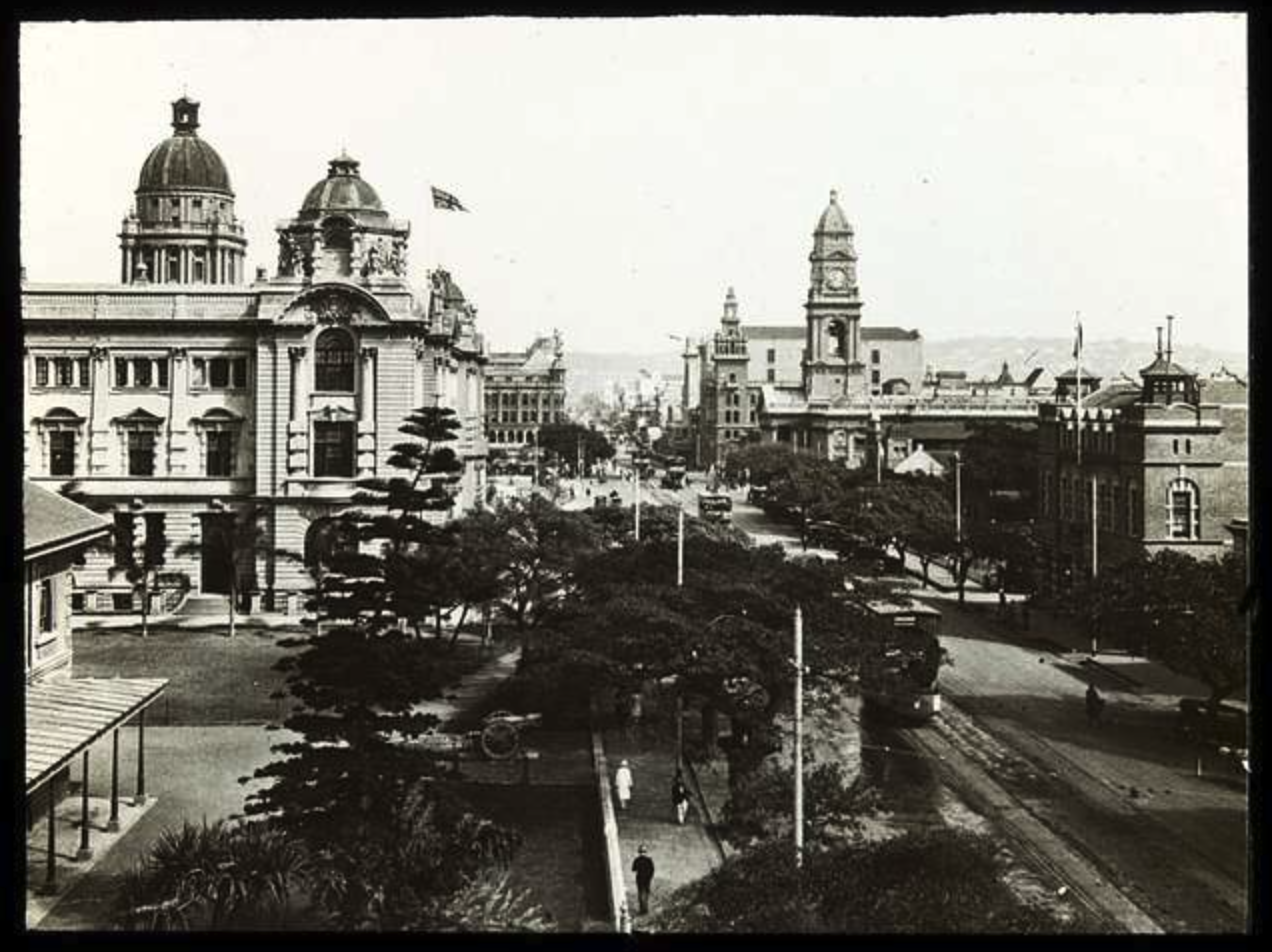

West Street in Durban, South Africa between 1920 – 1929. Photograph in the public domain from State Library of Victoria via Picryl.

Shoghi Effendi, Rúḥíyyih Khánum and William Sutherland Maxwell arrived in Durban, and, in the middle of World War II, they managed through some extraordinary miracle, to get a visa for the Belgian Congo, now the Democratic Republic of Congo.

There was absolutely no question in Shoghi Effendi’s mind that William Sutherland Maxwell would not accompany him and Rúḥíyyih Khánum overland to Cairo. William Sutherland Maxwell was 66 years old and in frail health, so he stayed behind, safely in Durban, and waited to follow Shoghi Effendi’s instructions: wait for an airplane, fly to Palestine, go to a hotel in Nazareth and wait for Shoghi Effendi and Rúḥíyyih Khánum to meet him there in order to return to Haifa together.

During the few weeks he was in South Africa, William Sutherland Maxwell designed his beloved wife, May Maxwell’s tombstone, incorporating the Guardian’s suggestions.

This map traces the approximate journey taken by Shoghi Effendi and Rúḥíyyih Khánum through Africa from their arrival in Durban, their journey to Johannesburg where they separated from William Sutherland Maxwell, their train journey on the Cape Town to Cairo railway from Johannesburg to Bulawayo, Victoria Falls, and arriving in the Belgian Congo in Lubumbashi—then Elizabethville.

Shoghi Effendi and Rúḥíyyih Khánum then traveled by road through the Belgian Congo to Kisangani in the northeast, as Shoghi Effendi searched for the flowering jungle. After Kisangani, they traveled through the village of Nia-Nia, leaving the Belgian Congo behind and entering the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan.

Shoghi Effendi and Rúḥíyyih Khánum arrived in Khartoum, where they unexpectedly met up with William Sutherland Maxwell again, and separated again, with Shoghi Effendi and Rúḥíyyih Khánum sailing up the Nile to Cairo where they boarded a train for Haifa, and finally rejoined William Sutherland Maxwell in the Holy Land.

The entire journey is described below.

A black and white lantern slide of a steam locomotive pulling cargo on the Cape to Cairo Railway line, the same railway which Shoghi Effendi and Rúḥíyyih Khánum used to travel from Durban to Lubumbashi. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Shoghi Effendi and Rúḥíyyih Khánum left Durban for Johannesburg, where they stayed over and boarded the Cape Town to Cairo railway.

The railway line was a project of politician and diamond magnate Cecil Rhodes, who had envisioned the railway crossing Africa from Cape Town to Cairo in an attempt to connect all British territories in Africa but the project was never completed in its entirety, with lines missing between northern Sudan and Uganda.

A stunning photograph of Victoria Falls, clearly showing why they are the largest waterfall in the world. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Shoghi Effendi and Rúḥíyyih Khánum traveled through what was then the Union of South Africa, through Southern Rhodesia—now Zimbabwe—and stayed over in Bulawayo. Shoghi Effendi wanted to show Rúḥíyyih Khánum Victoria Falls, one of the wonders of the natural world on the border Between Zimbabwe and Zambia.

. Shoghi Effendi wanted to show Rúḥíyyih Khánum Victoria Falls, one of the wonders of the natural world on the border Between Zimbabwe and Zambia.

The Guardian had first experienced the majesty of the Falls 11 years earlier in 1929, and while Victoria Falls are not the highest or the widest, they are the world’s largest waterfall, spanning nearly 2 kilometers. It must have been a breathtaking site for Rúḥíyyih Khánum to discover.

The Elizabethville—Lubumbashi—train station in the early 1910s. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

After Victoria Falls, Shoghi Effendi and Rúḥíyyih Khánum continued their train journey through Southern Africa, and crossed Northern Rhodesia—today’s Zambia—entering what was then the Belgian Congo and disembarking at the SNCC train station in Elizabethville—now Lubumbashi, in the Democratic Republic of Congo—sometime in the summer of 1940.

Some beautiful malachite objects as an abstract illustration of the malachite works Shoghi Effendi admired in Lubumbashi. The eggs, small boxes and small shallow bowls were manufactured in Kinshasa, in the Democratic Republic of Congo, in what used to be the Belgian Congo at the time of Shoghi Effendi’s visit. Photo by Kamal Zein.

Shoghi Effendi and Rúḥíyyih Khánum were the very first Bahá'ís to ever step foot in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Lubumbashi was—and still is—a major copper mining center. One of the fascinating things about copper is that an exquisitely beautiful mineral named malachite is also found near copper deposits, and Lubumbashi was famous for its malachite.

When Shoghi Effendi and Rúḥíyyih Khánum arrived in Lubumbashi, they visited a shop connected to the Catholic Mission where students and artisans carved objects from malachite, a stunning stone of swirling bands of green hues from very pastel to dark forest green, which Shoghi Effendi had liked very much. Rúḥíyyih Khánum took the opportunity to purchase a number of exquisitely carved objects for the International Bahá'í Archives.

Shoghi Effendi and Rúḥíyyih Khánum spent one night at the Hôtel Albert—now Hôtel du Globe. The next day, they headed north, towards Kisangani.

Digital painting of the Congolese man on a bicycle reaching Rúḥíyyih Khánum, having wandered off in the forest.

While Shoghi Effendi and Rúḥíyyih Khánum continued their cross-Africa journey by car through the Belgian Congo. At one point, their car broke down on a remote dirt road in the forest. Rúḥíyyih Khánum asked Shoghi Effendi if she could stretch her legs while the car was being repaired, and he agreed, but warned her about lions.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum walked down the deserted road soaking in the beauty of the virgin, unspoiled nature, until a man rode up to her on a bicycle and told her:

The gentleman in the car is very worried over you

Rúḥíyyih Khánum had lost track of time: she had been walking for almost two hours! She borrowed the man’s bicycle and raced back to her very worried Guardian.

In honor of Shoghi Effendi having crossed this author’s continent twice in his lifetime, and his longing to see our epic, extraordinary, lush, flowering jungle. Here is a photograph of the equatorial forest of Congo in full bloom during the rainy season, the very sight the Guardian longed to behold, and never did. Source: Congo Travel and Tours.

Shoghi Effendi and Rúḥíyyih Khánum finally arrived in Kisangani, in central-northern Belgian Congo and stayed at the Hôtel Stanley for one week. During this time, Shoghi Effendi fulfilled a dream of his, one he was not able to accomplish 11 years ago in 1929 during his first overland journey across Africa.

Shoghi Effendi had always wanted to visit Congo to experience the stunning beauty of the deep, virgin, flowering Equatorial jungle. At some point during their weeklong stay, Shoghi Effendi was able to book a tour of the jungle. The Guardian came away very disappointed, and there are two reasons for this.

First, Shoghi Effendi arrived in Kisangani during the dry season, which lasts from May September, and where nature recedes, so it would have been the worst time to see the forest. The rainy season, starting in October would have been ideal, but by then, Shoghi Effendi and Rúḥíyyih Khánum were thousands of kilometers away in the Sudan.

Second, Kisangani is not the deep forest, it is mostly tropical woodlands. The forests Shoghi Effendi was looking for would have been the Central Congolese lowland forests, in the heart of the country, thousands of kilometers out of Shoghi Effendi and Rúḥíyyih Khánum’s way—and the best time of year to see it would have been sometime between October and May.

Digital painting of a road near the Congolese village of Nia Nia.

From Kisangani, Shoghi Effendi and Rúḥíyyih Khánum reached Juba in the Sudan after a three-day drive, stopping over in the village of Nia-Nia.

Usually, when people traveled from Kisangani to Juba, they had to wait before a boat could carry them up the Nile. Once they managed to find a boat, the journey up the Nile lasted around one week, taking them 1,000 kilometers north to Kosti, Sudan, from where travelers boarded a train for the overnight journey to Khartoum.

We do not have details on how Shoghi Effendi and Rúḥíyyih Khánum arrived in Khartoum, though this likely could have been their itinerary. Once they arrived in Khartoum, they checked into a hotel, had dinner, and were sitting on the porch when a group of air passengers arrived to spend the night, and walking amongst them was William Sutherland Maxwell!

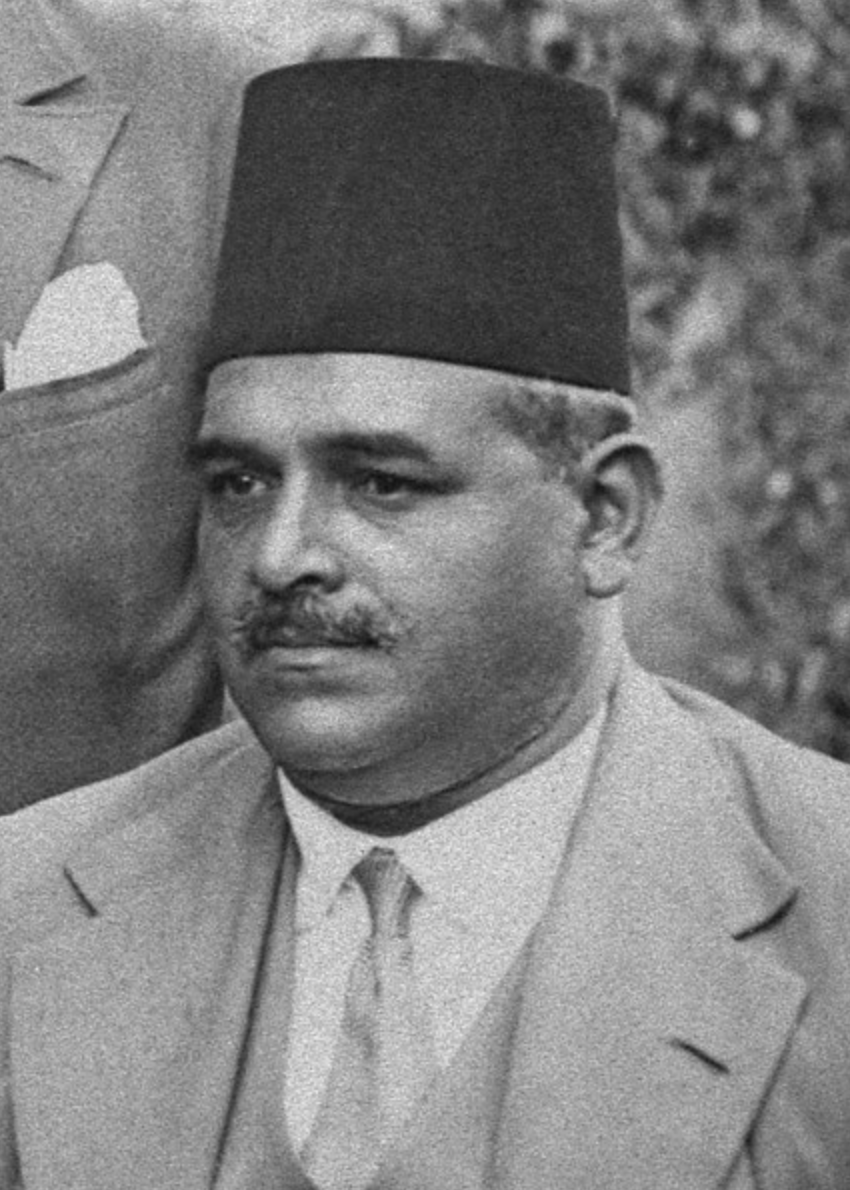

Lieutenant Colonel Sir Stewart Symes, Governor-General of the Sudan—in the center of the photograph. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

On 1 October 1940, the Governor-General of Sudan, Sir Stewart Symes, who had given an oration at 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s funeral 28 years before, invited the Guardian and Rúḥíyyih Khánum to lunch at the Palace.

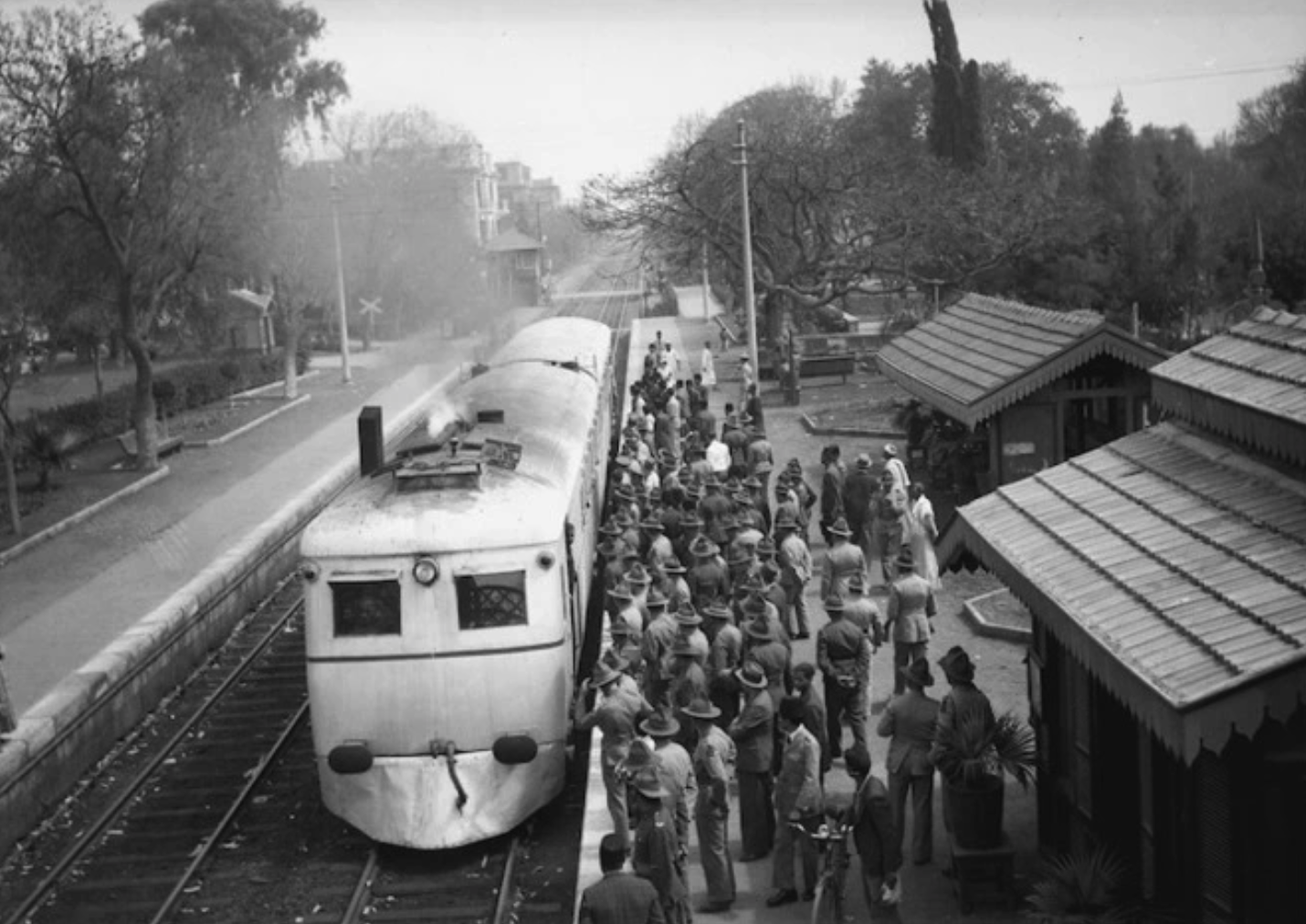

This likely would have been a scene that Shoghi Effendi and Rúḥíyyih Khánum encountered frequently on their train journeys, namely, encounters with soldiers. This photograph shows World War II soldiers alongside the Maadi-Cairo train at Maadi station, Egypt, in 1940. Maadi is a town on the main railway line from Khartoum to Cairo, and likely would have been a place that Shoghi Effendi and Rúḥíyyih Khánum stopped on their way back to the Holy Land. Source: National Library of New Zealand.

We have no details on the remainder of Shoghi Effendi’s second journey through Africa, but they would have no doubt sailed up the Nile until Cairo where they boarded a train bound for Haifa, where Shoghi Effendi arrived on 27 December 1940, seven months after leaving for England.

The trip had been filled with stress, uncertainty, suspense, danger, but also great adventure.

Map asset by Freepik.

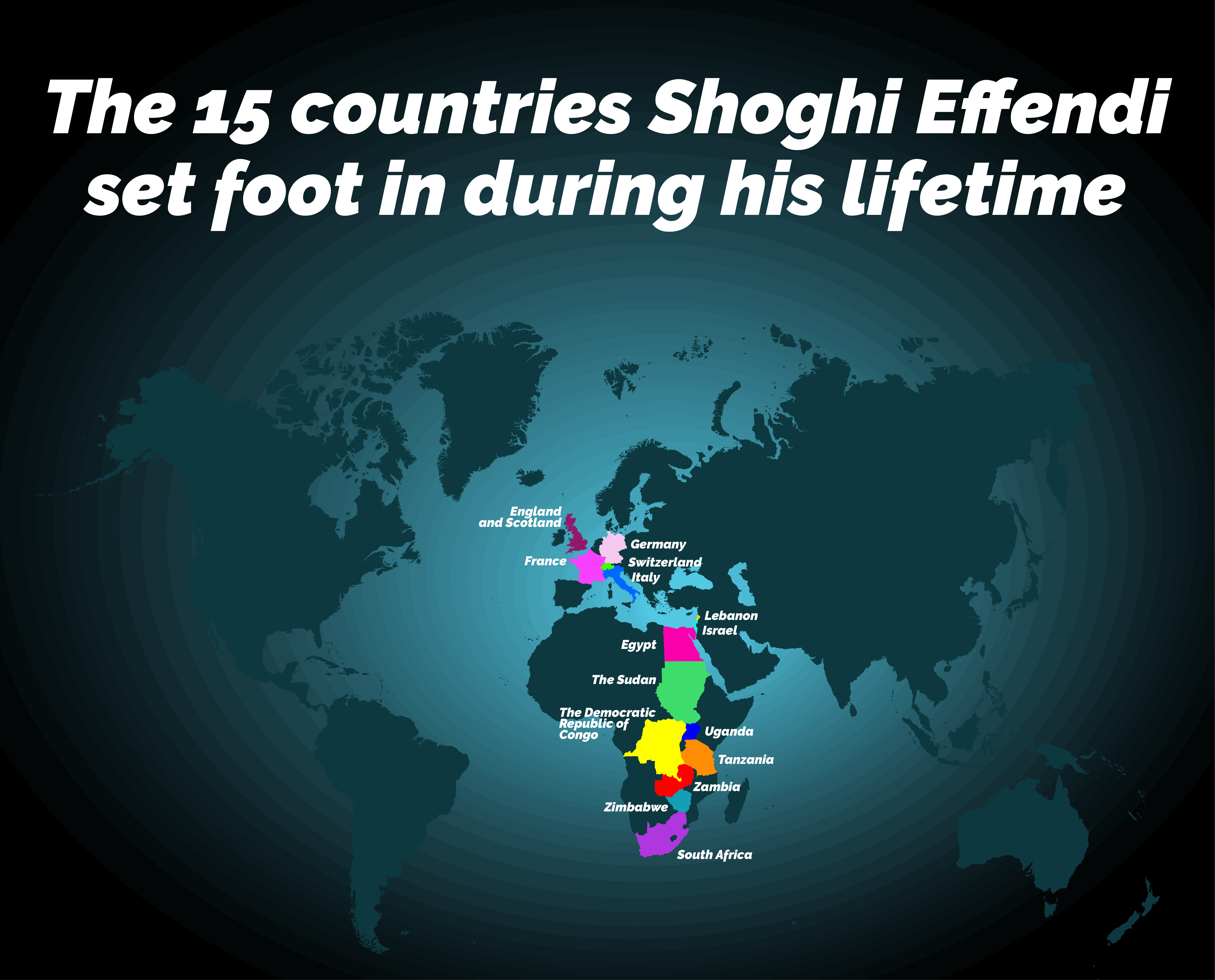

In The Priceless Pearl, Rúḥíyyih Khánum notes the following fascinating fact:

Although Shoghi Effendi never visited the Western Hemisphere and never went farther east than Damascus it is interesting to note he twice traversed Africa from south to north.

The map above is a map of all the countries in which Shoghi Effendi set foot in.

He went to school in Beirut, in what is now called Lebanon, and visited 'Abdu'l-Bahá four times in Egypt. He left the Holy Land in January 1921, and spent a few weeks in Neuilly, outside of Paris, France in a rest home. He then studied in England for a little less than two years, crossing the country from south top north and traveling to Scotland.

On the way to the first retreat of his Guardianship in Switzerland in 1922, Shoghi Effendi briefly visited Germany before rejoining the Bernese Alps.

In 1929, Shoghi Effendi traveled to South Africa, and what is now Zimbabwe, and Zambia. Because he was not able to enter the Belgian Congo—the Democratic republic of Congo on that journey, he went around “East Africa” and so must have crossed Tanzania and Uganda on the way to the Nile, where he boarded a ship and sailed to Egypt, meaning he crossed what is today South Sudan and the Sudan.

In 1940, Shoghi Effendi traveled from the Holy Land to Italy and France, then to England, South Africa, and this time, on his second journey across Africa, he obtained a visa and crossed the Belgian Congo from south to north before rejoining the Nile in the Sudan.

Haifa was repeatedly bombed by the Italians in 1940. This low-quality photograph shows oil tanks burning after Italian bombs have been dropped in September 1940. Source: Australian War Memorial.

World War II brought dangers and problems to the Guardian’s doorstep. He could never lay down, not for a single moment, his burden of responsibility for safeguarding the Faith in the Holy Land and worldwide, and the war made him suffer greatly, but he faced the six years of this world-engulfing conflict with the distinctive calm of Head of the Faith. A composure, dignity and assurance that Bahá'u'lláh and 'Abdu'l-Bahá had evinced before him in the face of impossible circumstances.

As Guardian of the Bahá'í Faith, Shoghi Effendi was divinely guided in his decisions. This meant that everything had to be referred to him for a final decision, even when he was ill. One day, Rúḥíyyih Khánum was frantic, and Shoghi Effendi told her that world leaders and prime ministers could delegate their powers if they had to, even for a short time, but that this was not an option for him. The Guardian, so long as he was alive, could not delegate anything to anyone else for a single moment.

World War II never actually reached the Holy Land, but they felt the imminent danger and its anxieties keenly, because for six years, they lived under the threat that the war could unfurl in Palestine at any moment.

Palestine, like the United Kingdom and many other countries in the world, enacted a complete wartime blackout. Blackouts were a protection against night air bombings. In an effort to limit the devastation, the Allies blacked out their countries so the Germans only saw black and would not know where to bomb.

Blackout regulations began the day the war started, on 1 September 1939, even before the formal declaration of war. Civilians were required to black out all their windows and doors at night with thick black material, heavy curtains or paint, to prevent any light from getting through. Street lights were switched off, cars were equipped with slotted covers to deflect their light down towards the road.

For the population, including for Rúḥíyyih Khánum and Shoghi Effendi, blackouts were one of the most unpleasant aspects of the war. Haifa was a port with a large oil refinery, and an important strategic location during the war, so, of course, a blackout was implemented in Haifa.

Shoghi Effendi and Rúḥíyyih Khánum lived in 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s house at 7, Haparsim, and because the house had over a hundred windows, they could not black them all out, so in some parts of the house, they would walk in the dark. Rúḥíyyih Khánum remembers receiving frequent calls from air-raid wardens.

Although only a few bombs were dropped around Haifa with minimal damage, Shoghi Effendi and Rúḥíyyih Khánum spent the war with frequent air raids, and experienced sprinkles of shrapnel from anti-aircraft guns. This caused the Guardian to worry excessively because even a piece of shrapnel the size of a grape could have destroyed one of the resting-places of the Holy Family in the Monument Gardens. In the end, however, all the monuments were miraculously spared.

There were so many air-raid alerts at night that the Guardian stopped even getting up to look out the window. When the siren would blare, he simply kept working.

In 1941, when the British invaded Lebanon, Shoghi Effendi and Rúḥíyyih Khánum heard heavy fire for a week, and the Vichy forces—Occupied France led by Maréchal Pétain who collaborated with the Nazis—frequently dive-bombed the port, about 800 meters from their home.

This was the greatest war activity the Guardian ever saw.

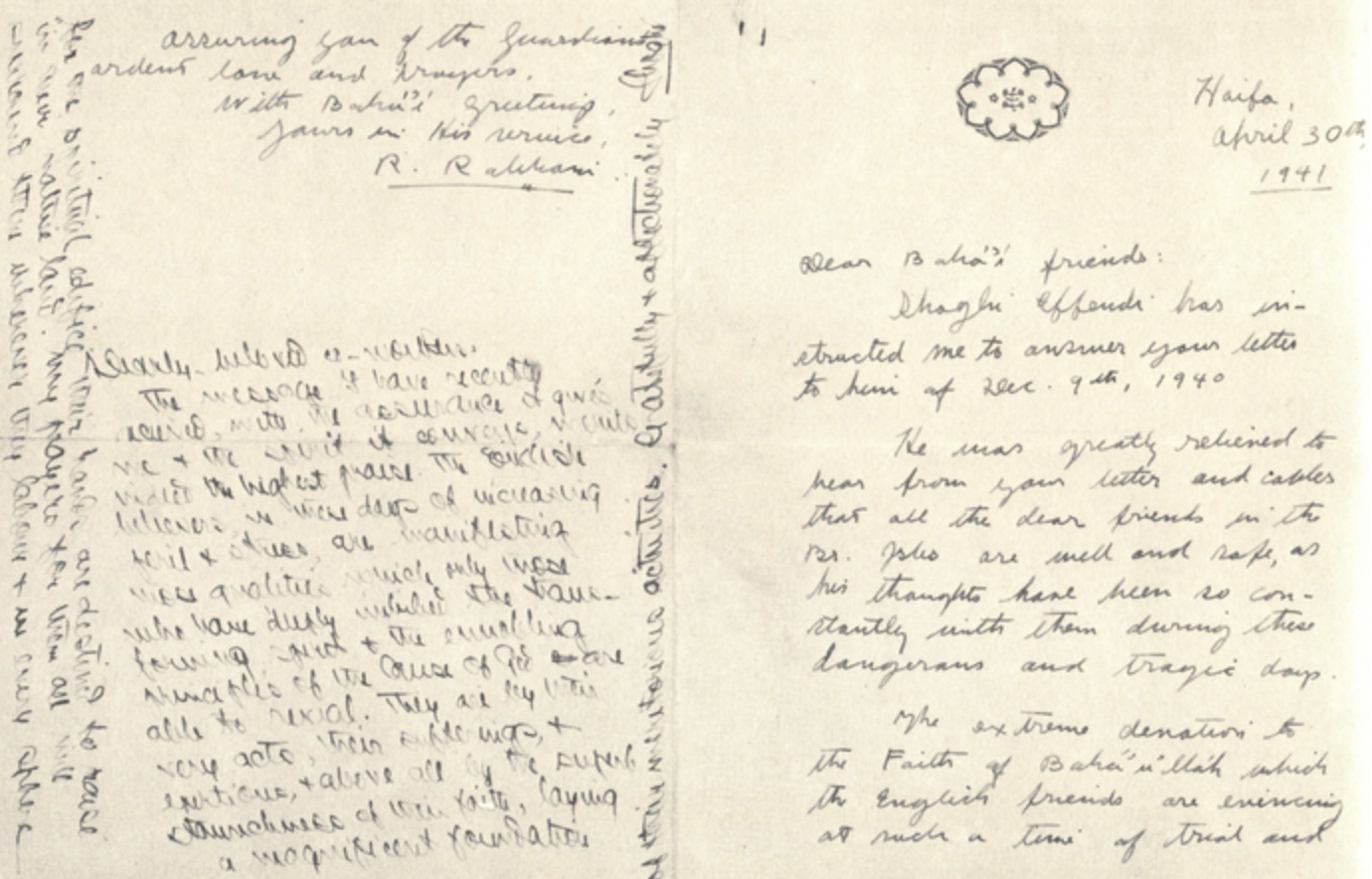

30 April 1941: Letter written by Amatul'Bahá Ruḥíyyíh Khánum as the Guardian’s secretary. The postscript is in the hand of Shoghi Effendi. Source: Bahaimedia.

In 1941, four years after their wedding, Amatu’l-Bahá Rúḥíyyih Khánum became the Guardian’s personal English secretary, a post she would occupy for the next 16 years until his passing on 4 November 1957.Acting as the Guardian’s secretary was one of Rúḥíyyih Khánum’s most outstanding services performed during his ministry, and the Guardian himself trained her.

Amatu’l-Bahá Rúḥíyyih Khánum wrote thousands of letters on Shoghi Effendi’s behalf.

In the early years of her service as the Guardian’s secretary, Shoghi Effendi would write down the points he wanted her to include in his response, but later on, when he witnessed her tremendous skill as a writer, he would simply tell her what to answer.

Amatu’l-Bahá Rúḥíyyih Khánum always stressed that the Guardian read every single letter she wrote—whether to individuals or to institutions—before sending it, adding his usual handwritten postscript, which sometimes climbed around the margins of the pages.

Gate of the House of the Master at 7 Haparsim. The proposed Bahá Street—now called Iran Street—is perpendicular to Haparsim Street. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

In January 1941, the Haifa City Council named a short street which was perpendicular to Haparsim, the street in front of 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s house, “Bahá Street.”

The Guardian was furious.

He sent his brother—who was his secretary at the time—to the municipality right away and said:

Tell him to take that down. Immediately. That this is an insult to the Bahá’í Faith to put the name of its prophet on a street. And if they don't I will tear down with my own hands. And if they want to put me in jail, let them

Rúḥíyyih Khánum remembered thinking:

What shall I do to get into jail too? They'll take him to jail and I'll have to stay here.

The City Council had a meeting and decided to change the name of the street to “Iran Street,” which still exists today.

‘Alí-Akbar Furútan, 11 years after his first pilgrimage to the Holy Land. Source: Bahaimedia.

Future Hand of the Cause ‘Alí-Akbar Furútan was able to come on pilgrimage to the Holy Land, in the middle of World War II, with his wife and their 8-year-old daughter. They traveled through Qazvín, Kirmánsháh, and Qasr-i-Shirín, stayed two days in Baghdad, and traveled overland to Haifa. When they crossed the border with British Mandate Palestine, their luggage was inspected because they were carrying two expensive silk Persian rugs—the gift of an Iranian Bahá'í—but they were released without charge as soon as they explained the rugs were for the house of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, and they arrived in Haifa in the late afternoon of 16 February 1941.

The women were taken to meet Amatu’l-Bahá Ruḥíyyíh Khánum, and the men were taken downstairs to a large basement where a radiant old man wearing a long black coat and a Persian style of fez wrote down their names on a piece of paper before leaving the room. He returned a few minutes later informing the men that the Guardian was ready to meet them.

The men tried to prostrate themselves, but the Guardian would not let them and his first question was about the health of the Iranian Bahá'í community, the situation of the Bahá'ís and the affairs of the National Spiritual Assembly. After receiving answers, the Guardian turned to ‘Alí-Akbar Furútan and said:

You are the secretary of both the National and Local Spiritual Assemblies. The affairs of the National Spiritual Assembly are conducted in a very organized manner, and I testify to your work. Your services are now local and national, and they will be international in the future.

After this the Guardian asked about the persecutions in Iran and ‘Alí-Akbar Furútan described the difficulties the Bahá'ís were having in obtaining official recognition for Bahá'í marriages. The Guardian explained these persecutions were not important and would soon pass, and that the most important factor was the steadfastness of the Iranian Bahá'ís, also emphasizing the importance of Bahá'ís participating in Nineteen Day Feasts, then he stood up and took his leave, saying:

You must be very tired. Take leave and rest in the Pilgrim House. I shall see you again tomorrow. May you be in God's protection.

The Eastern Pilgrim House in the 1950s. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

When eastern Bahá'ís came on pilgrimage, from Iran, Iraq, Egypt, North Africa, Syria, Turkey, India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Central Asia, they had specific times at which they met the Guardian, and the men and women were separated. Every day at 4:00 PM, the eastern pilgrims of both sexes would meet with the Custodian of the Eastern Pilgrim House, rent a car, and drive down to the House of 'Abdu'l-Bahá.

At this point, they separated: The women went to meet with Amatu’l-Bahá Ruḥíyyíh Khánum, and the men were led to the waiting room for the Guardian to leave his work in his office, come down the stairs, and join the men for a walk. This walk took place in the quiet afternoon streets of Haifa or in the gardens of the Shrine of the Báb and last about 40 minutes, and sometimes more, during which the Guardian would speak on a wide range of topics.

The second day of ‘Alí-Akbar Furútan’s pilgrimage, 17 February 1941, the Guardian spoke about the incomparably lofty station of the Prophet Muḥammad as Messenger of God and recipient of Divine Revelation—a theme which he would revisit during their pilgrimage—about Islam as the origin of the Bahá'í Faith, the Qur’án as the Word of God, and the infallibility of the Imáms. He also spoke about the gloriously high station of the Twelve Imáms, particularly Imám Ḥusayn.

The Guardian had a message for Iranian women: he wanted them to follow in the footsteps of Marion Jack, Martha Root, May Maxwell, and Keith Ransom-Kehler, and share equally with the men in service to the Bahá'í Faith, not allowing themselves to be left behind when it came to serving Bahá'u'lláh.

Another interesting advice the Guardian gave the Bahá'ís of the east was linguistic in nature: that they should master Persian and Arabic so well, that they could express themselves with equal ease in both languages—as Bahá'u'lláh had revealed in both Persian, Arabic, and mixed Persian and Arabic—and the Guardian said:

The Persian and Arabic languages should dissolve into each other like unto milk and sugar.

The Guardian specified that all the Ḥadíths—Islamic traditions not recorded in the Qur’án—which Bahá'u'lláh quoted were all authentic, and Bahá'ís of Christian backgrounds should accept these as principles of Islam, just as Bahá'ís of Jewish or Zoroastrian background should accept Jesus Christ as the Word of God and His utterances in the New Testament as authentic.

Often the topics addressed by the Guardian in meeting with eastern pilgrims during these walks were geared to the countries and environments they were returning to: the topics were often Islamic, geared to Muslim countries, and the Guardian had important themes to convey to them, themes and ways of speaking about Islam, the Prophet Muḥammad, the Imáms, the Qur’án, which would be of precious use to them, and themes that the western pilgrims would not be able to use, and so at dinner with the western pilgrims, the Guardian spoke about the Administrative Order and more Christian topics.

The Guardian also accompanied the men pilgrims to the Shrines of the Báb and a Bahá'í on two different days, and he would chant the Tablet of Visitation on these occasions.