Written and illustrated by Violetta Zein

This part covers the life of the Báb from the age of 28 in 1847 to the age of 29 in 1848.

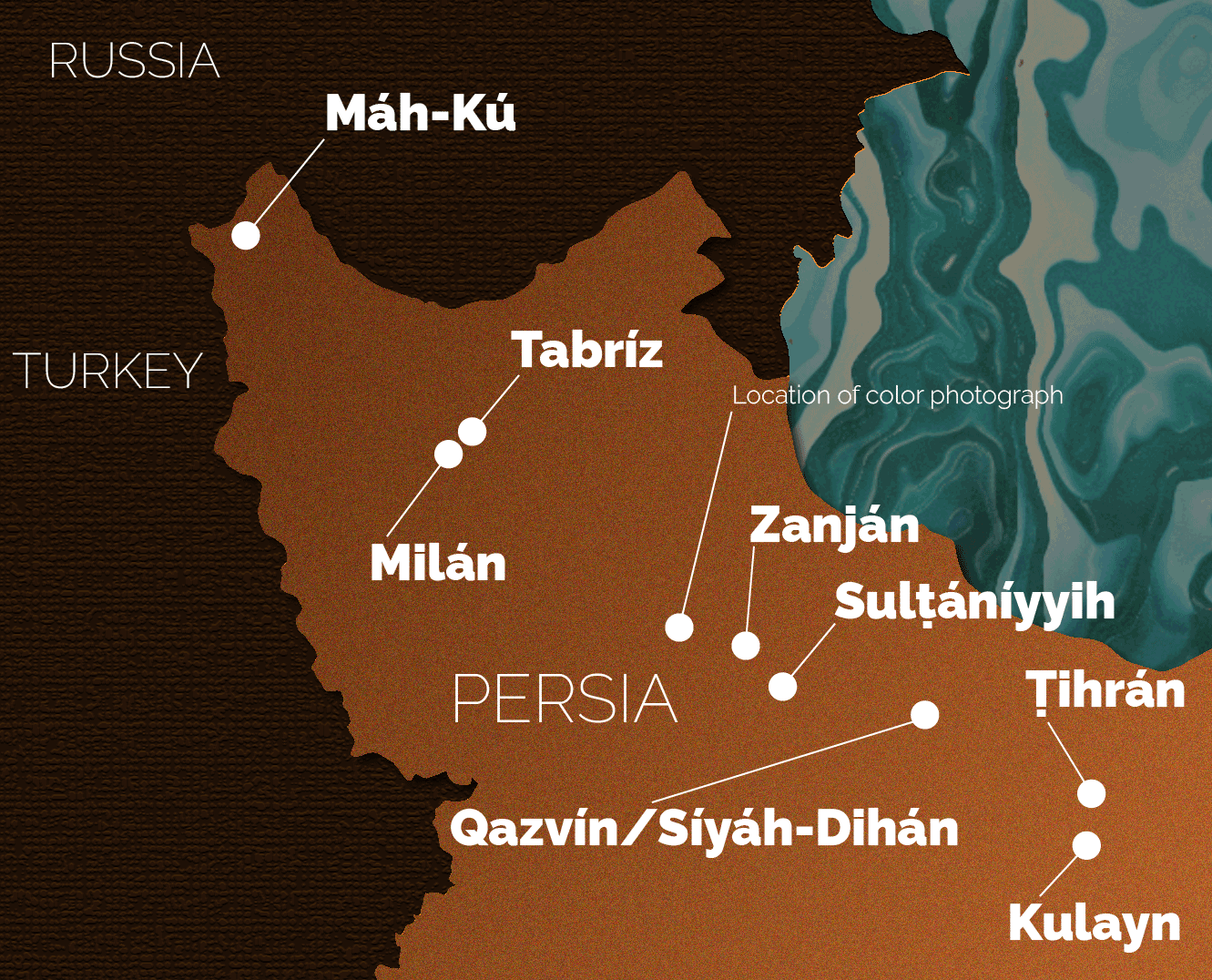

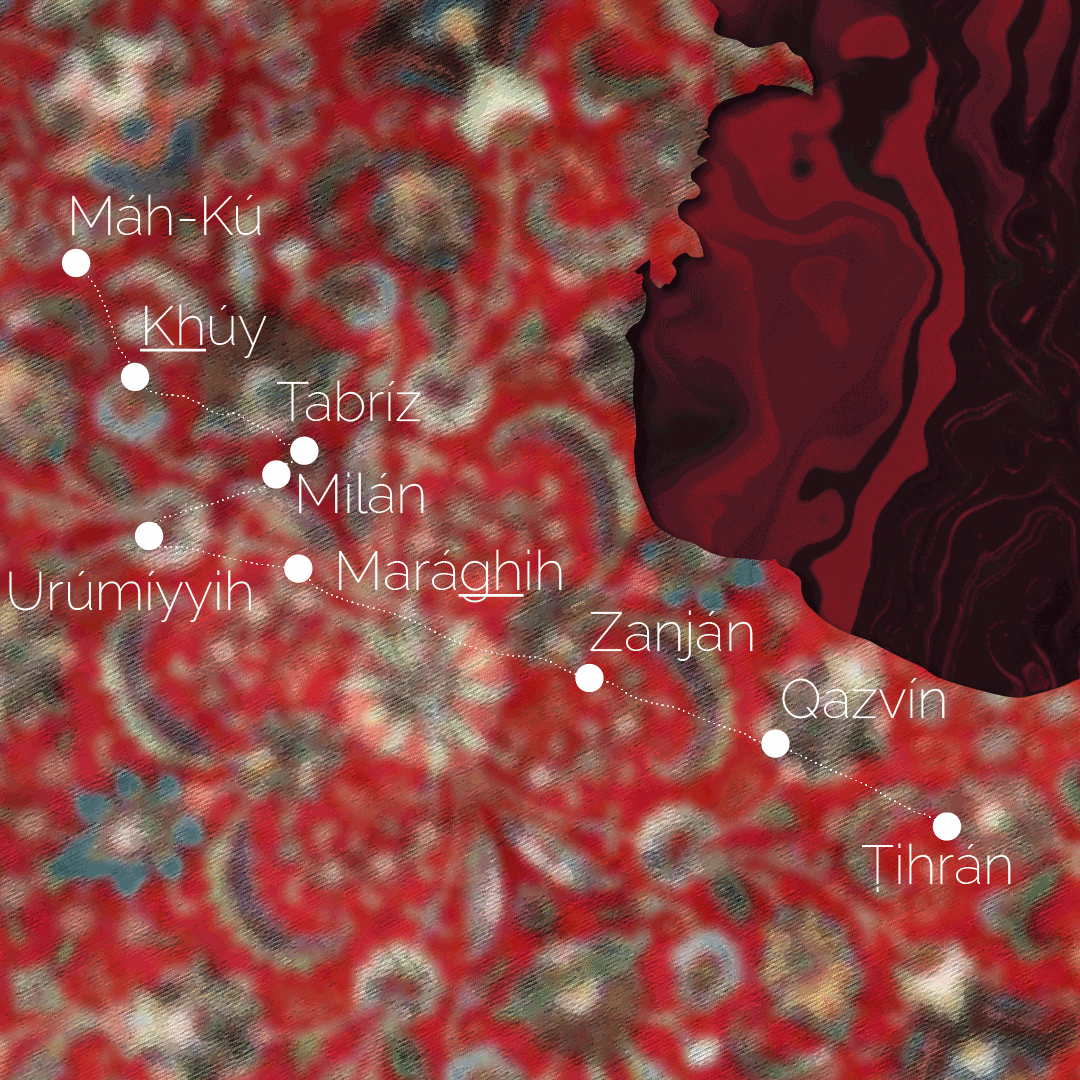

Map of the Báb’s journey to Ádhirbáyján including all the stopping points mentioned in this section and the location of the breathtaking photograph in the last story of the section. © Violetta Zein

Ḥájí Mírzá Áqásí had manipulated the Sháh and obtained that the Báb be banished to the remotest northwest corner of Persia, a town called Máh-Kú in Ádhirbáyján, on the border between the Russian, Ottoman and Persian empires, in an attempt to quell His influence.

In Máh-Kú there was a bleak fortress, perched on a mountain peak, and this was where the Báb would spend the next nine months of His life.

Muḥammad Big and his troops, who had by then become completely captivated by the Báb and devoted to Him, were ordered to take Him from Kulayn to Máh-Kú, and two of the Báb’s followers were permitted to accompany Him: Siyyid Ḥusayn-i-Yazdí, His amanuensis, and his brother, Siyyid Ḥasan.

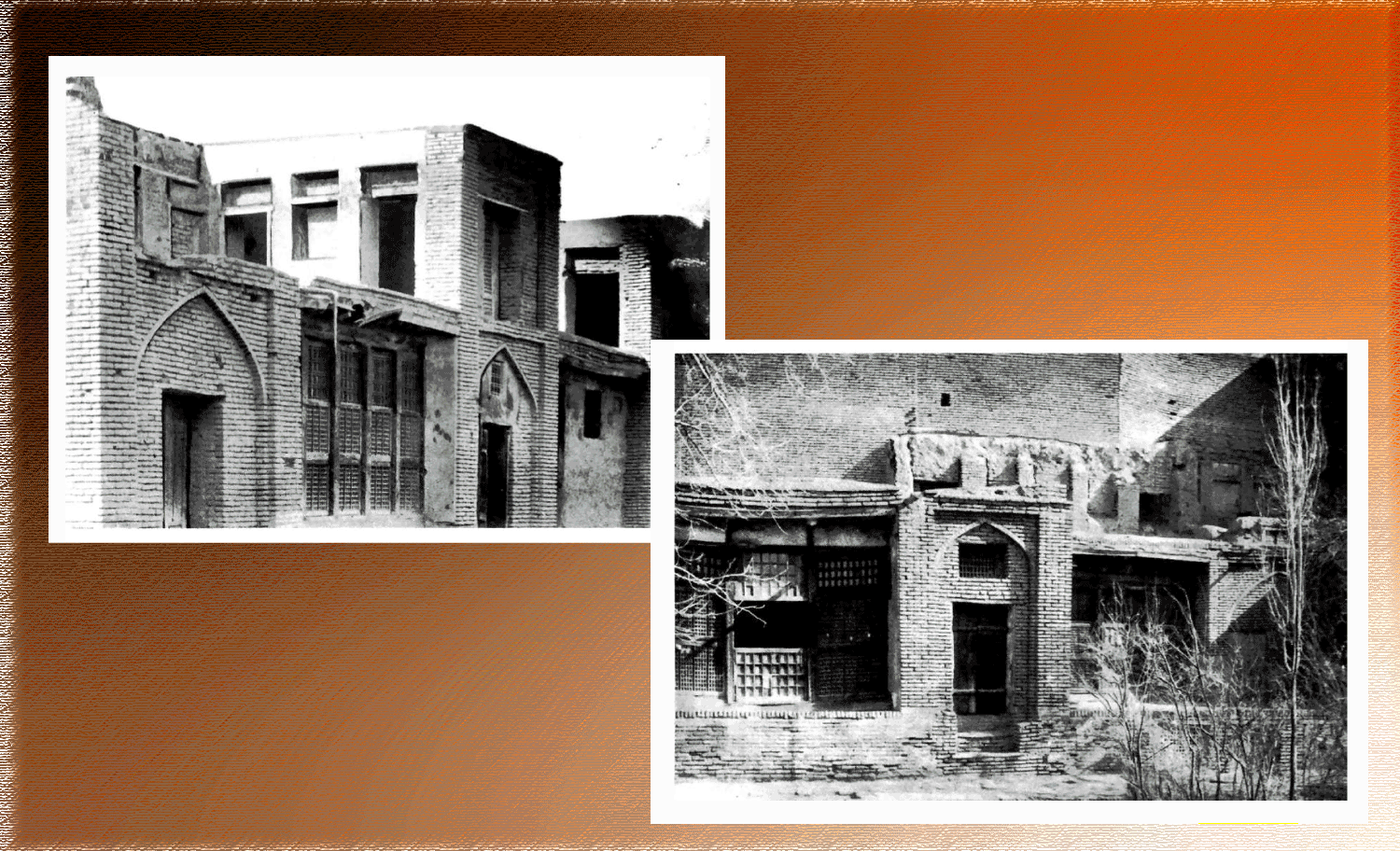

Two houses belonging to the male relatives of Ṭáhirih in Qazvín. The Báb addressed letters to Ṭáhirih’s father and uncle during His stay in Síyáh-Dihán, a village very close to Qazvín. Source: Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, page 274.

As the escort made its way north, they passed by a village called Síyáh-Dihán, near Qazvín. From Síyáh-Dihán, the Báb wrote Tablets to Ḥájí Mírzá Áqásí, and to Ṭáhirih’s father and uncle. A number of Bábís attained His presence in that village, including Mullá Iskandar, who had been Ḥujjat’s envoy to Shíráz to report back on the Báb.

The Báb asked Mullá Iskandar to deliver His Tablet to Ḥájí Sulaymán Khán-i-Afshár in Qazvín, a devout disciple of Siyyid Káẓim-i-Rashtí, a Tablet which contained this majestic declaration of His station and a clear call to action:

“He whose virtues the late siyyid unceasingly extolled, and to the approach of whose Revelation he continually alluded, is now revealed. I am that promised One. Arise and deliver Me from the hand of the oppressor.”

Three days later, Ḥájí Sulaymán Khán received the Báb’s Tablet but ignored His call and left for Ṭihrán, where Ḥujjat was.

“The mountains have their claim”: Decorated quote of the Báb’s response to the Bábís who have come to free Him. © Violetta Zein Background digital painting of the mountains behind Máh-Kú.

As soon as Ḥujjat learned of the Báb’s message, he mobilized the Bábís of Zanján to march and deliver the Báb. Together with a large number of Bábís of Qazvín, the Bábís of Zanján planned to deliver the Báb with a daring scheme.

At midnight, they arrived at the Báb’s campsite, and although His guards were asleep, the Báb told them He would not run away:

“The mountains of Adhirbáyján too have their claims.”

It may seem contradictory that the Báb would ask Ḥájí Sulaymán Khán to “arise and deliver Me” yet refuse to go with the Bábís who had come to do just that, however, the Báb knew full well that His divinely fore-ordained destiny was in Máh-Kú, Chihríq and Tabríz.

This large number of Bábís from two cities who had organized and mobilized themselves, consulted and planned the Báb’s almost successful rescue had learned valuable skills in the process that would come to their aid during the uprisings in the coming years. This event can be construed as an increase in capacity for the fledgling Bábí community of Persia.

After Síyáh-Dihán, the Báb’s escort stopped in many different towns, villages, and caravanserais on the way to Tabríz. We do not have a full list of the Báb’s stops, but we know that He stopped briefly in in a town called Sulṭáníyyih, the stage before Zanján, and also stopped in Zanján at a caravanserai where many Bábís came to meet Him.

A breathtaking photograph of the landscape around Andabad-e Olya, in Zanjan province. This is a symbolic photograph, as we do not know the exact route the Báb’s escort took to bring Him from Kulayn to Tabríz, but this landscape lies on a probable route of the Báb’s journey and is offered as an illustration of how taxing His journey on horseback must have been through such a mountainous region. Photo by Hossein Rezaei on Unsplash.

When the Báb and His escort arrived in Mílán, many of the inhabitants came to see Him, and were filled with wonder at the majesty and dignity of His bearing.

When they left Milán the next morning, an old woman brought a child who had been scalded and whose head was covered with scabs to the neck, and she begged the Báb to heal her boy.

The Báb called the boy to Him, took out a handkerchief, and waved it over its head while reciting verses. The child was instantly healed and 200 of the inhabitants of Milán who had witnessed this instantly became Bábís.

After the troop had left behind Milán, the Báb threw His horse into such a fast gallop that no one could keep up with Him, no matter how hard they pushed their horses. When they had finally caught up with Him, and only because He had reined in His horse, the Báb said to the men with a smile:

“Were I desirous of escaping, you could not prevent me.”

The journey to Ádhirbáyján was incredibly taxing. All the men accompanying the Báb, Muḥammad Big and his troops and the two Bábís, although most of them were practiced horsemen, and used to arduous travel conditions, had a difficult time keeping up and staying in their saddles.

The Báb, however, showed no sign of tiredness or fatigue. From the moment he took His seat on the saddle when they set off in the morning, to the moment He dismounted when they broke for camp, the Báb would not even shift in His saddle, or adjust His posture. His resistance was superhuman.

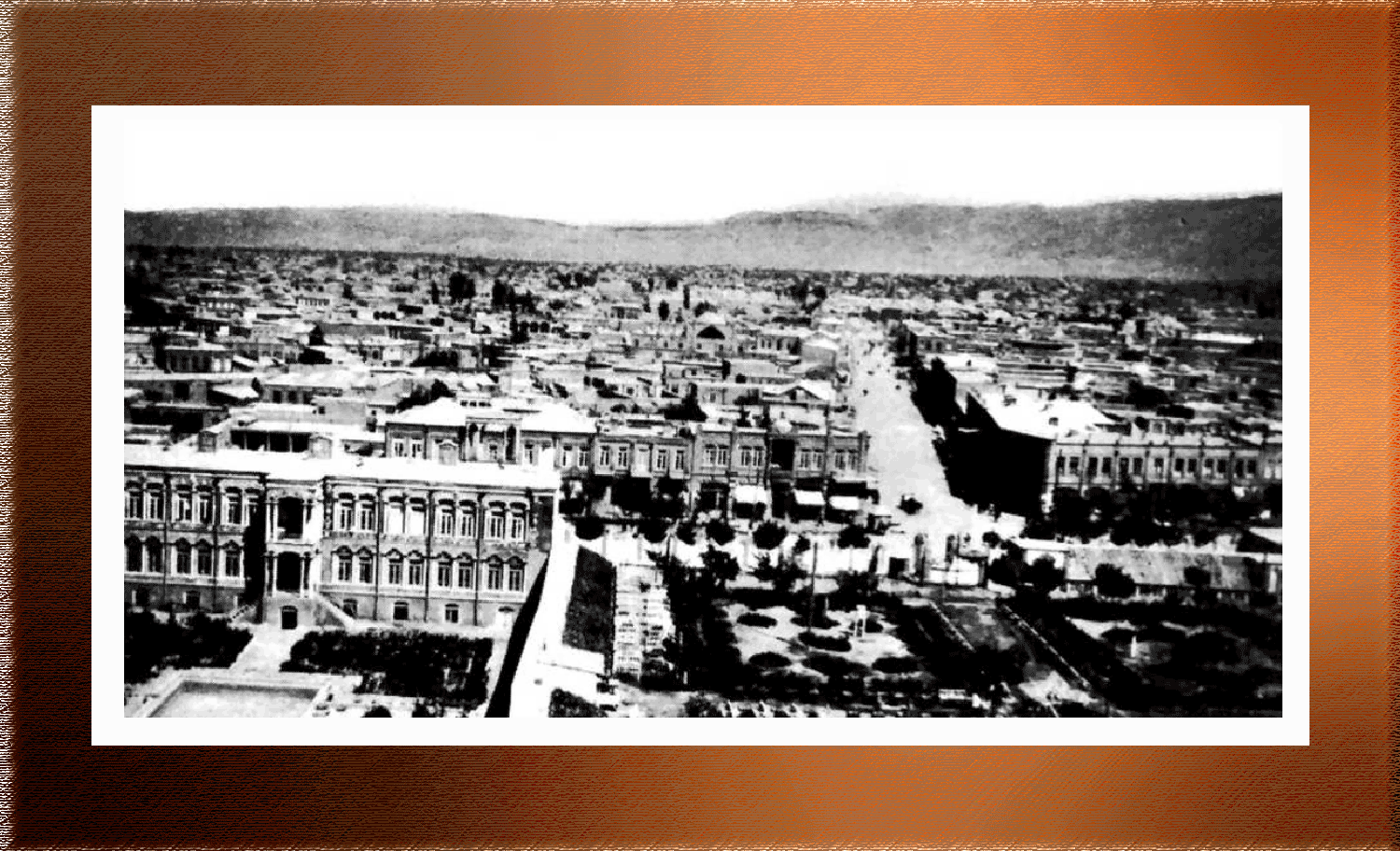

Panorama of Tabríz. Source: Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, page 237.

By their arrival in Tabríz, Muḥammad Big had become a Bábí.

Utterly heart-broken, he begged the Báb to forgive him:

“The journey from Iṣfahán has been long and arduous. I have failed to do my duty and to serve You as I ought. I crave Your forgiveness, and pray You to vouchsafe me Your blessings.”

The Báb replied with His characteristic and touching loving-kindness:

“Be assured. I account you a member of My fold. They who embrace My Cause will eternally bless and glorify you, will extol your conduct and exalt your name.”

Entrance to Tabríz from Abraham Valentine Williams Jackson, Persia Past and Present: A Book of Travel and Research, page 38. Source: Internet Archive.

After Milán, the Báb’s escort reached Tabríz. The Bábís of Tabríz tried to go out of the city to meet Him but they were turned back.

Only a youth managed to break through the cordon of guards and soldiers. He ran more than mile barefoot, and mad with ecstasy, threw himself in the path of one of the mounted guards, catching the man’s cloak and fervently kissing his stirrup.

The enkindled youth cried out to all the horsemen:

“Ye are the companions of my Well-Beloved. I cherish you as the apple of my eye.”

When the boy entered the Báb’s presence, he fell to the ground and could not stop weeping. The Báb dismounted, and raised him up, embracing him and wiping his tears.

The tears of this youth, welcoming the Báb into the city that would be the theater of His violent martyrdom in three years’ time, was moving and majestic. As the Báb entered the city, its narrow streets crowded with teeming masses, cries rang out from every direction:

“Alláh-u-Akbar” (“God is the Greatest”)

resonating from every direction.

Tabríz officials were alarmed by this wonderful and unprecedented reception, and sent town criers to warn the people against trying to see or visit the Báb.

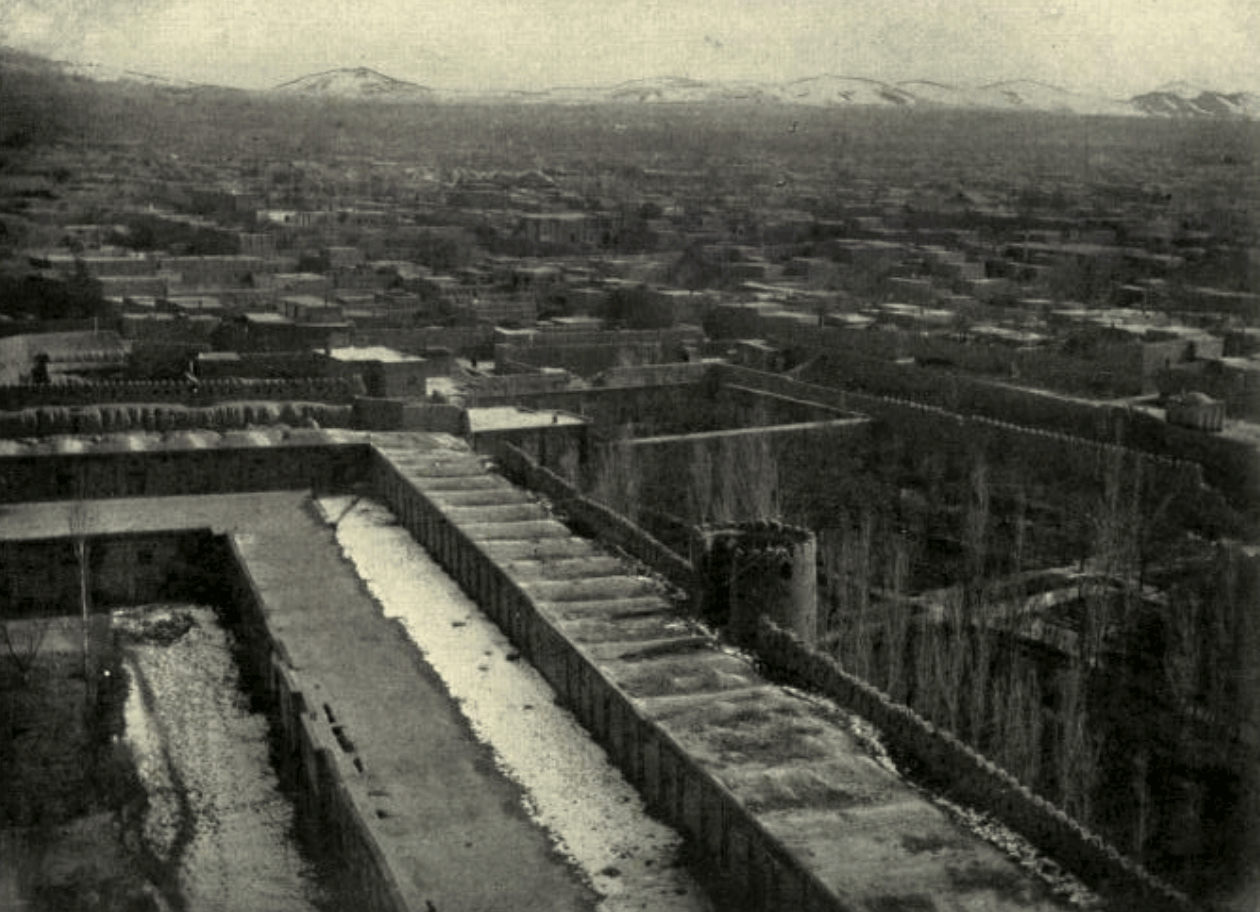

Modern-day photograph of the Citadel (Arg) of Tabríz. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The Báb was kept in Tabríz for 40 days, and His stay in the city was marked by such intense excitement on the part of the population that no one, not the public or His followers, were allowed to meet with Him.

The Báb was strictly secluded in a guarded house. His only visitors were Ḥájí Muḥammad-Taqíy-i-Mílání, a well-known merchant, and Ḥájí ‘Alí-‘Askar, a Bábí of Tabríz.

Muḥammad-Taqíy-i-Mílání had a two-hour visit with the Báb, and when he left, the Báb gave him two cornelian ringstones, instructing him to have them engraved with verses He had revealed for him, have them mounted and brought back to Him as soon as they were ready. Ḥájí ‘Alí-‘Askar entered the Báb’s presence several times to get clarifications on the commission of the ringstones.

Ḥájí ‘Alí-‘Askar had once lamented to Mullá Ḥusayn that he had not had the chance to enter the Báb’s presence in Shíráz, but Mullá Ḥusayn confidently told him he would one day enter the Báb’s presence seven times. When Ḥájí ‘Alí-‘Askar had completed his seventh visit to the Báb in Tabríz, the Báb turned to him and spoke:

“Praise be to God, who has enabled you to complete the number of your visits and who has extended to you His loving protection.”

After 40 days, the order came down to take the Báb to Máh-Kú, Ḥájí Mírzá Áqásí’s birthplace.

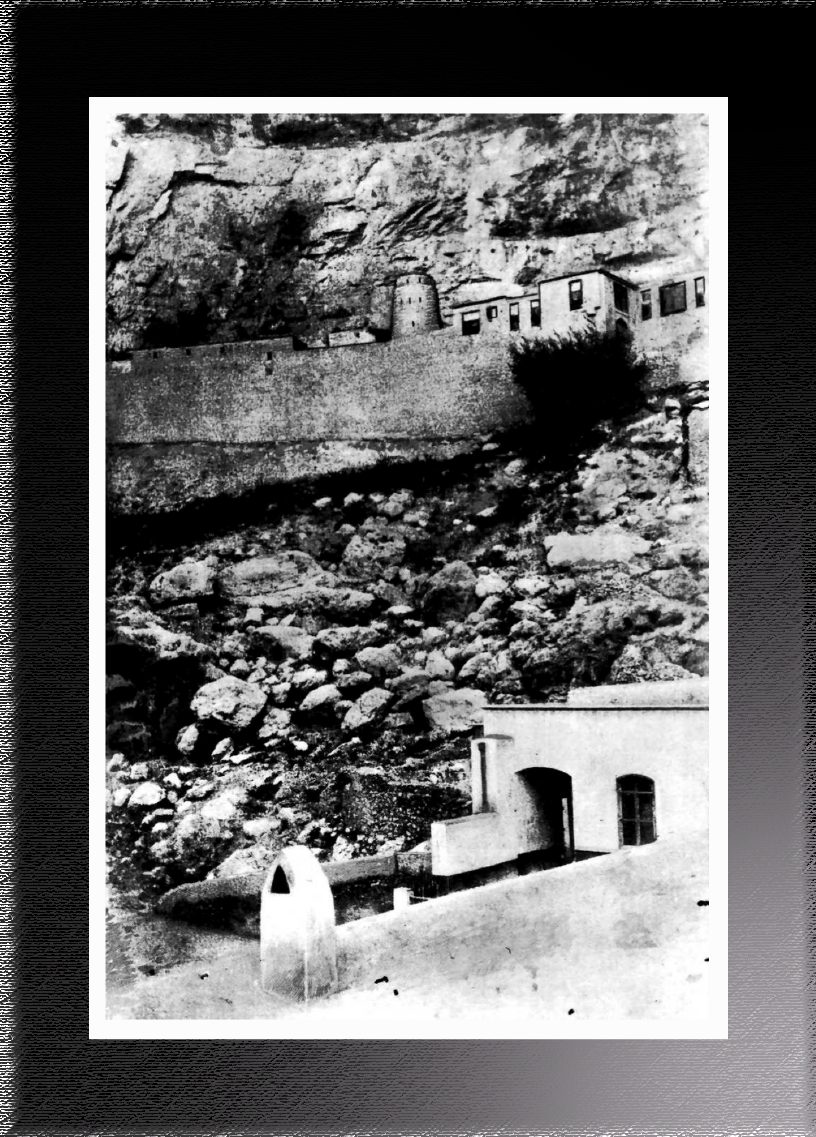

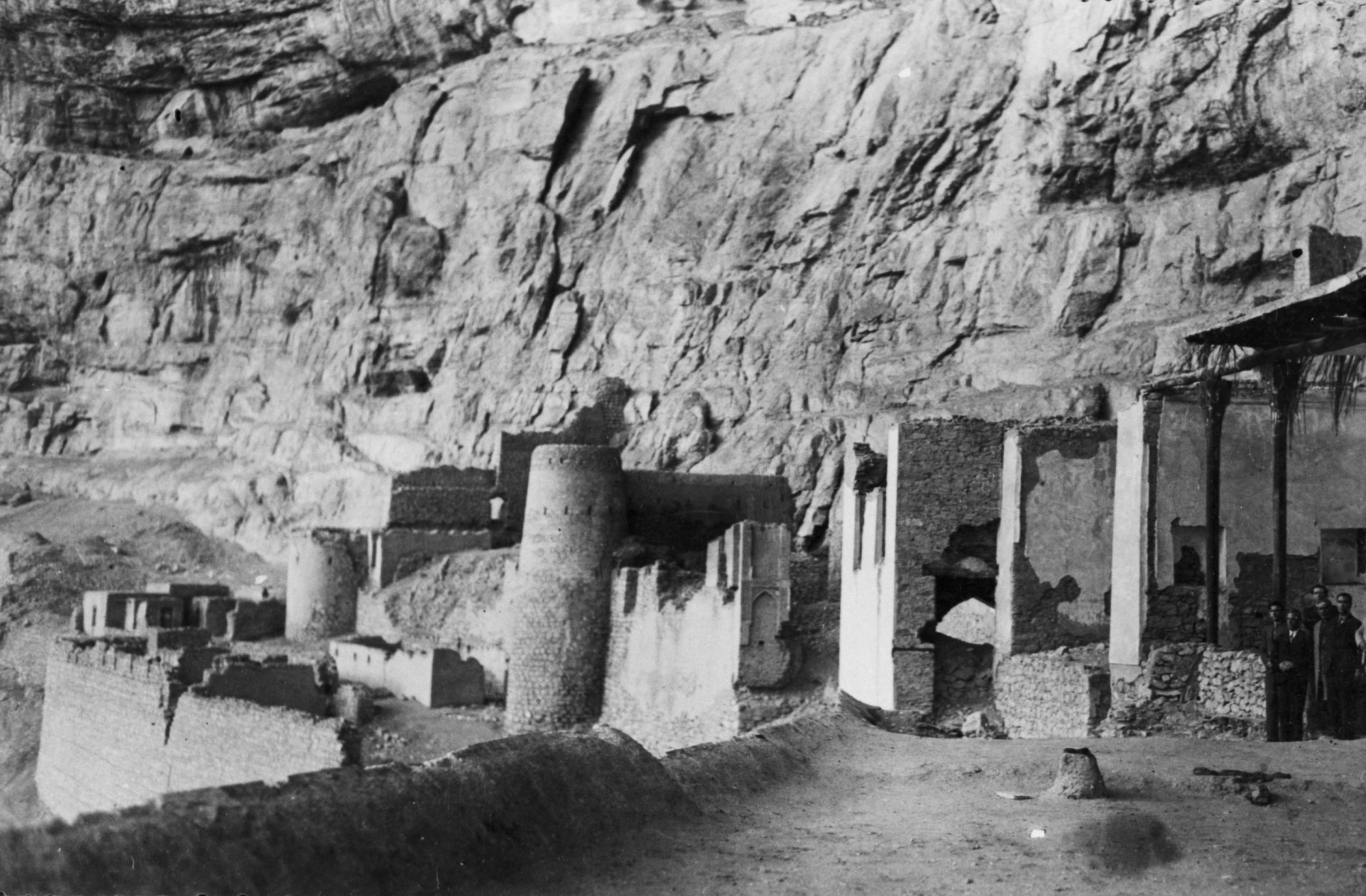

The castle of Máh-Kú. Source: Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, page 243.

Máh-Kú was a town populated by Sunní Kurds. Only one road led from the fortress of Máh-Kú to the town, and the castle itself was bordered to the west by the river Aras (also called Araxes), and to the south by the Ottoman empire, and it sat in a remote, vast, inhospitable, and turbulent region of Persia.

The warden of the castle of Máh-Kú was a rough and rude man named ‘Alí Khán Máh-Kú’í, extremely strict at the beginning of the Báb’s incarceration.

‘Alí Khán had refused to allow any Bábí to stay in the town of Máh-Kú overnight, but he failed to prevent the people of Máh-Kú to gather at the foot of the mountain to try and obtain a glimpse of the Báb.

The Kurds of Máh-Kú had been so won over by the Báb that even the severe warden could not stop them from gathering daily below the fortress in the hope of receiving the Báb’s blessing.

When Shaykh Ḥasan-i-Zunúzí, one of the earliest converts of the Báb from Shíráz after the Letters of the Living, finally arrived in Máh-Kú, he only found shelter in a mosque outside city limits.

Eventually, Shaykh Ḥasan found a clever way to communicate with Siyyid Ḥasan, the brother of Siyyid Ḥusayn, the Seventh Letter of the Living and the Báb’s amanuensis, who came into town each day from the castle to buy provisions escorted by a guard, by exchanging letters and messages.

For a while Shaykh Ḥasan-i-Zunúzí was the only direct link of communications between the Báb and His followers.

The Báb gave Máh-Kú the title Jabal-i-Básiṭ (the Open Mountain). During His first two weeks in Máh-Kú, the Báb was forbidden to meet with anyone other than His His amanuensis, Siyyid Ḥusayn, and his brother, Siyyid Ḥasan.

The Báb later stated that the conditions of His imprisonment in in the four-towered fortress of Máh-Kú were so severe that He did not have a lamp and His cell lacked a door.

The castle of Máh-Kú. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

One day, the Báb told Siyyid Ḥasan that he would have to stop communicating with Shaykh Ḥasan secretly, as He intended to tell ‘Alí Khán that His visitors should be allowed to come and go in peace from the fortress.

Very early the next morning, ‘Alí Khán was at the gate of the fortress, knocking furiously, and shouting at the guards to let him in to see the Báb. Siyyid Ḥasan brought the request to the Báb, who admitted ‘Alí Khán to His presence. The warden was visibly shaken, and extremely emotional and threw himself at the Báb’s feet, begging to be put out of his misery.

He had been riding through the wilderness, and approaching the gate of Máh-Kú when he had seen the Báb, standing by the side of the river, praying:

“With outstretched arms and upraised eyes, You were invoking the name of God. I stood still and watched You. I was waiting for You to terminate Your devotions that I might approach and rebuke You for having ventured to leave the castle without my leave. In Your communion with God, You seemed so wrapt in worship that You were utterly forgetful of Yourself. I quietly approached You; in Your state of rapture, You remained wholly unaware of my presence. I was suddenly seized with great fear and recoiled at the thought of awakening You from Your ecstasy. I decided to leave You, to proceed to the guards and to reprove them for their negligent conduct. I soon found out, to my amazement, that both the outer and inner gates were closed. They were opened at my request, I was ushered into Your presence, and now find You, to my wonder, seated before me. I am utterly confounded. I know not whether my reason has deserted me.”

The castle-fortress prison under its great cliff, the town of Máh-Kú. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

The Báb confirmed what the warden had seen, and accepted his declaration of Faith:

“What you have witnessed is true and undeniable. You belittled this Revelation and have contemptuously disdained its Author. God, the All-Merciful, desiring not to afflict you with His punishment, has willed to reveal to your eyes the Truth. By His Divine interposition, He has instilled into your heart the love of His chosen One, and caused you to recognise the unconquerable power of His Faith.”

The warden’s arrogance was wiped away, replaced with humility and devotion.

His first words to the Báb were:

“A poor man, a shaykh, is yearning to attain Your presence. He lives in a masjid [mosque] outside the gate of Máh-Kú. I pray You that I myself be allowed to bring him to this place that he may meet You. By this act I hope that my evil deeds may be forgiven, that I may be enabled to wash away the stains of my cruel behaviour toward Your friends.”

The Shaykh ‘Alí Khán was talking about was Shaykh Ḥasan-i-Zunúzí, whom he personally escorted into the fortress and brought into the Báb’s presence.

Modern-day sunny photograph of the fortress of Máh-Kú to illustrate a vignette taking place in the summer months, with Bábís visiting the Báb. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Over time, ‘Alí Khán grew so captivated by the Bab’s innocence and prophet-like behavior that he lifted the initial strict constraints of His confinement in Máh-Kú, and became a Bábí.

After ‘Alí Khán’s conversion, his devotion to the Báb increased daily, and he did everything he could think of to alleviate the Báb’s incarceration, and even helped Bábís when they needed it.

The prison gates no longer barred the Báb from His followers, and an increasing number of Bábís from all over Persia came to visit Him in Máh-Kú like a never-ending stream of eager and devoted pilgrims. Each pilgrim was allowed three days in the Báb’s presence, after which He dismissed every loving follower, each with specific instructions and regions of service, but all working to consolidate the Bábí Faith in Persia.

By allowing these visits, ‘Alí Khán brought a tremendous aid to His Prisoner, and facilitated the spread and strengthening of the Báb’s Cause, but he never lost his ardent devotion and paid a visit every Friday to the Báb to offer Him his respect, and to assure Him of his loyalty, often giving the Báb the gift of rare, delicious fruits, and any food he thought the Báb would enjoy.

Bábís came from everywhere to attain the presence of their Lord, among them Mullá Ḥusayn, the Bábu'l-Báb. The Báb received him at the gate of the castle and celebrated the Feast of Naw-Rúz with him. Before he took his leave, the Báb instructed Mullá Ḥusayn to visit Tabríz and other towns of the province of Ádharbáyján, and then head to Zanján, Qazvín, Ṭihrán, and finally to the province of Mázindarán.

These were the pleasant conditions in which the Báb spent the months of Summer and Autumn of 1847.

“Fortress of Stone”: Digital art piece to convey the grim surroundings of the Báb during nine months in Máh-Kú, a mineral fortress built of stone, surrounded by stone, on a stone mountain. © Violetta Zein. Source of photo 1: Wikimedia Commons; Source of photo 2: Wikimedia Commons.

Despite the conversion of ‘Alí Khán, the Báb’s nine months in Máh-Kú were dominated by His resignation and willingness to die, both recurrent themes in His Revelation during this period of time.

Although He had some access to His followers, and ‘Alí Khán was a loyal disciple, Máh-Kú was a deserted fortress, and the Báb’s life was deeply solitary, at the top of the massive stone castle, located just beneath a huge hanging cliff, looking across a vast, lonesome plain.

It seems during these lonely nine months, that grief and joy followed each other in the Báb’s life at rapid intervals, often precipitated by the recitation of religious tragedies of reading from books of elegies.

A few months after His arrival in Máh-Kú, in late 1847, the Báb expressed His disillusionment with the people of Persia:

“Let us not bother with people’s opinion. Although their cries of ‘Hurry up! Hurry up! [i.e., pleas for the Advent of the Promised One] have filled the earth, they are not sincere. We have tested them. Now nothing for us is more expedient than leaving them to themselves to read their prayers…but remain ignorant of the real lord.”

During this period of time, the Báb’s Writings also reverberated these emotional impulses, and the nine months in Máh-Kú would prove to be one of the most prolific periods of Revelation in the Báb’s entire ministry.

“Frozen winter”: Digital painting of the fortress of Máh-Kú under heavy snow. © Violetta Zein

After a pleasant Summer and Autumn came a very harsh winter, starting in December 1847. The cold was so intense it affected even the copper utensils and when the Báb did His ablutions, the drops shone as they froze on His face.

That winter, at the end of His prayers, the Báb always called Siyyid Ḥusayn, and asked him to read aloud from the Muhriqu’l-Qulub, a book praising the virtues, laments the death, and narrating the circumstances of the martyrdom of the Imám Ḥusayn.

The Báb was moved so deeply by the tales of the Imám’s agonizing pain, inflicted by such a devious enemy that streams flowed down His face as He listened.

The tears the Báb shed were not only for past sufferings, but for future ones. He wept for the persecutions He knew Bahá'u'lláh would soon endure at the hands of His enemies.

To the Báb, past atrocities were a sign of future calamities endured by Bahá'u'lláh, humiliations and trials to which even the Imám Ḥusayn had not been subjected to.

“Naw-Rúz dream”: Digital painting imagining the town of Máh-Kú at sunrise in Spring, and the bridge over the river where ‘Alí Khán meets Mullá Ḥusayn. © Violetta Zein Original image inspiration: Panorama of Máh-Kú from Wikimedia Commons.

Mullá Ḥusayn had been walking from Mashhád, accompanied by his servant Qambar-‘Alí, to visit the Báb in Máh-Kú. On his long journey, they had stopped in Ṭihrán and Mullá Ḥusayn had met with Bahá'u'lláh.

The night before he arrived, ‘Alí Khán, the warden of the fortress, had a dream that the Prophet Muḥammad would soon arrive at Máh-Kú, and that He would immediately direct His steps to the fortress and visit with the Báb to wish Him a happy Naw-Rúz.

In his dream, ‘Alí Khán rushed out, filled with joy, to meet and welcome the Prophet on foot in the direction of the river, and arrived at a bridge, when he saw two men walking towards him. He threw himself at their feet, and bent to kiss the hem of their robes when he woke up from his dream.

‘Alí Khán felt flooded with joy, as if heaven and all its delights were crowded in his heart. He was so convinced his dream was real, that he performed his ablutions, said his prayer, wore his best clothes, perfumed himself and walked out alone, at sunrise, to the spot he had seen in his dream. He had given instructions that his three fastest horses be brought to the bridge ahead of him.

When ‘Alí Khán arrived at the bridge, he was amazed to find the two men he had seen in his dream walking, one behind the other, towards him. He fell to the ground of the one he thought was the Prophet Muḥammad, and kissed his feet, but when he begged the men to mount the horses he had prepared for them, Mullá Ḥusayn replied:

“Nay, I have vowed to accomplish the whole of my journey on foot. I will walk to the summit of this mountain and will there visit your Prisoner.”

This extraordinary experience deepened ‘Alí Khán’s Faith and increased His reverence and devotion towards the Báb. He humbly followed Mullá Ḥusayn until they reached the gate of the fortress of Máh-Kú.

For a story where the Báb shares quinces, apples, and other declicacies with His followers an 1885 – 1887 painting by Paul Cézanne: Still Life With Quince, Apples, and Pears. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Once inside the fortress of Máh-Kú, Mullá Ḥusayn saw the Báb, who had been standing at the gate. Mullá Ḥusayn immediately stopped, and bowed deeply, motionless. The Báb extended His arms and embraced Mullá Ḥusayn affectionately, and, taking him by the hand, led him to His chamber.

The Báb then summoned His followers to His presence and they celebrated the third Naw-Rúz of His Dispensation together with dishes of confectionary and the best of fruits. The Báb distributed the delicacies to His assembled friends himself, and offered some quinces and apples, sent to Him from Milán, and picked especially for the Báb, to Mullá Ḥusayn.

The Báb had spent nine months in Máh-Kú, and until this Naw-Rúz, none of His followers, except Siyyid Ḥusayn and Siyyid Ḥasan had been allowed to spend the night inside the fortress. That day, ‘Alí Khán went to the Báb and said:

“If it be Your desire to retain Mullá Husayn with You this night, I am ready to abide by Your wish, for I have no will of my own. However long You desire him to stay with You, I pledge myself to carry out Your command.”

That day, large numbers of Bábís arrived in Máh-Kú, and all were permitted to enter the Báb’s presence.

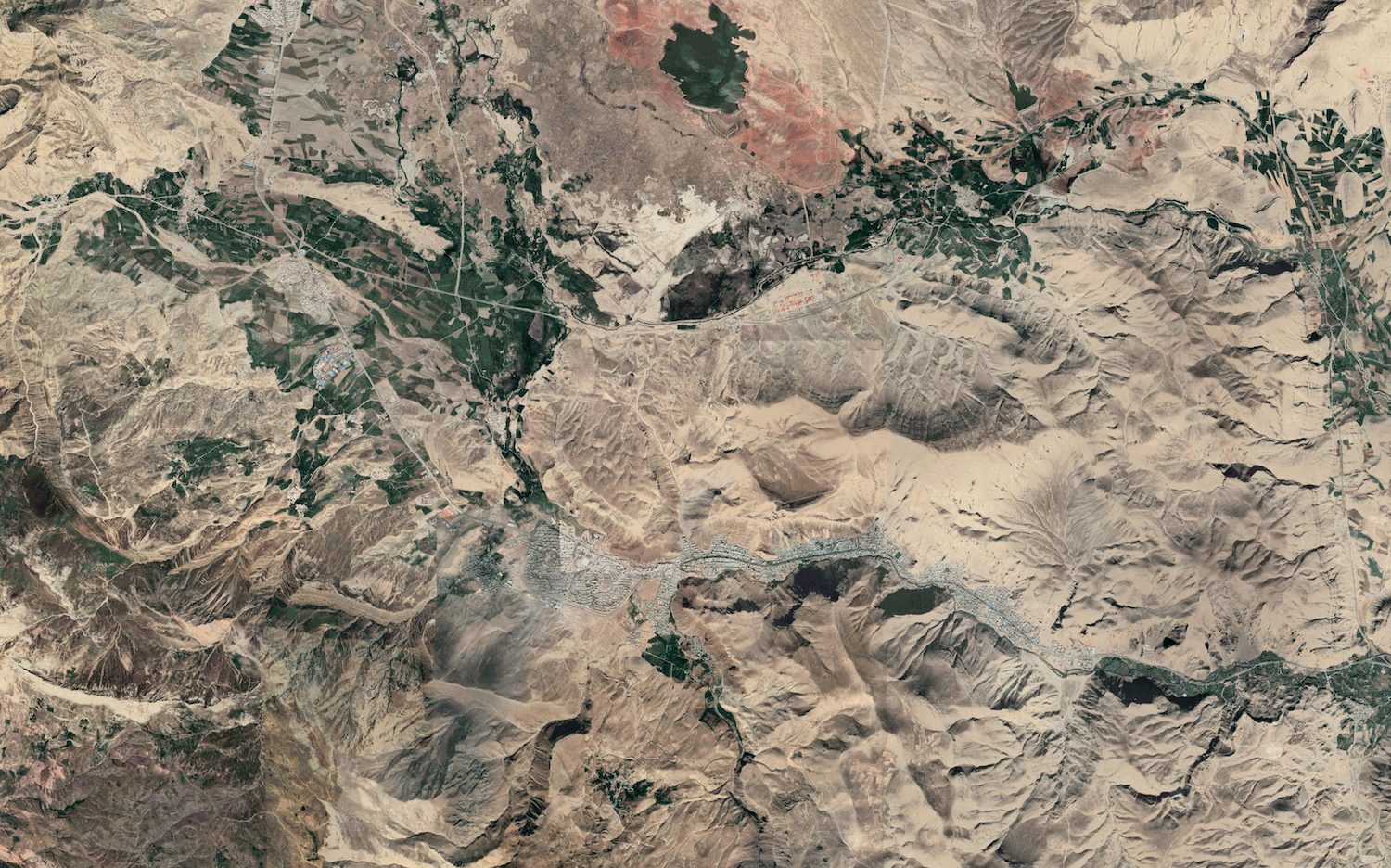

Satellite image of the region of Máh-Kú, Ádhirbáyján in northwestern Persia. Máh-Kú is in the center of the map, running lengthwise in the valley, and the river Araxes (or Aras on modern maps) is running along the mountains to the north of the map. Source: Google Earth.

One day, as the Báb stood with Mullá Ḥusayn looking out over the countryside surrounding the fortress, He looked at the Aras river winding its way below them. The Báb turned to Mullá Ḥusayn and explained to him that this was the river Ḥáfiz had spoken about in the verse:

“O zephyr, shouldst thou pass by the banks of the Araxes, implant a kiss on the earth of that valley and make fragrant thy breath. Hail, a thousand times hail, to thee, O abode of Salma! How dear is the voice of thy camel-drivers, how sweet the jingling of thy bells!”

The “abode of Salma” was a literary reference to the town of Salmas, near Chihríq, and the Báb was telling Mullá Ḥusayn He would soon be transferred:

“The days of your stay in this country are approaching their end. But for the shortness of your stay, we would have shown you the ‘abode of Salma,’ even as we have revealed to your eyes the ‘banks of the Araxes.’”

The Báb then quoted a well-known Ḥadíth to His companion:

“Treasures lie hidden beneath the throne of God; the key to those treasures is the tongue of poets.”

In their time together, looking out above the landscape, the Báb prepared Mullá Ḥusayn for what was to come, and asked him not to share His revelations with anyone else, then told him:

“A few days after your departure from this place, they will transfer Us to another mountain. Ere you arrive at your destination, the news of Our departure from Máh-Kú will have reached you.”

It is likely that the Báb’s call for the Bábís to gather in Khurásán (where the conference of Badasht would take place) was a result of Mullá Ḥusayn’s visit with Him in Máh-Kú.

“Mullá Ḥusayn’s Mission Map”: Map of all the destinations between Máh-Kú and Ṭihrán which the Báb indicates to Mullá Ḥusayn in their conversation in the story below on a background of a digitally-distressed Tabríz Persian carpet. © Violetta Zein

Mullá Ḥusayn spent nine days in the presence of the Báb. On the morning of the ninth day after Naw-Rúz, the Báb said His last farewell to Mullá Ḥusayn during which He gave him specific instructions for the next several months:

“You have walked on foot all the way from your native province to this place. On foot you likewise must return until you reach your destination; for your days of horsemanship are yet to come. You are destined to exhibit such courage, such skill and heroism as shall eclipse the mightiest deeds of the heroes of old. Your daring exploits will win the praise and admiration of the dwellers in the eternal Kingdom. You should visit, on your way, the believers of Khúy, of Urúmíyyih, of Marághih, of Milán, of Tabríz, of Zanján, of Qazvín, and of Tihrán. To each you will convey the expression of My love and tender affection. You will strive to inflame their hearts anew with the fire of the love of the Beauty of God, and will endeavour to fortify their faith in His Revelation. From Tihrán you should proceed to Mázindarán, where God’s hidden treasure will be made manifest to you. You will be called upon to perform deeds so great as will dwarf the mightiest achievements of the past. The nature of your task will, in that place, be revealed to you, and strength and guidance will be bestowed upon you that you may be fitted to render your service to His Cause.”

Qambar-‘Alí, was the fearless and faithful servant of Mullá Ḥusayn, who accompanied him on his journey to Máh-Kú all the way from Mashhád, and who followed him everywhere, even into martyrdom.

When Mullá Ḥusayn left Máh-Kú on 30 March 1848, Qambar-‘Alí left with him, and the Báb’s parting words to him were also momentous:

“The Qambar-‘Alí of a bygone age would glory in that his namesake has lived to witness a Day for which even He who was the Lord of his lord sighed in vain; of which He, with keen longing, has spoken: ‘Would that My eyes could behold the faces of My brethren who have been privileged to attain unto His Day!’”

Estimated distance map between Máh-Kú and Chihríq, taking into account the horse journey and stopping points in the 19th century. © Violetta Zein

Ḥájí Mírzá Áqásí had spies in Máh-Kú who were reporting on the Báb and ‘Alí Khán’s every movement, sending detailed reports about his devotion to the Báb:

“Day and night, the warden of the castle of Máh-Kú is to be seen associating with his captive in conditions of unrestrained freedom and friendliness.”

The spies also reported that ‘Alí Khán, who had refused to let his daughter marry one of the sons of the Sháh, had insisted, over and over again, that the Báb take his daughter in marriage. The Báb had refused, time and time again, and ‘Alí Khán had even asked Mullá Ḥusayn to intercede on his behalf in the matter, all to no avail.

All of these negative reports inflamed Ḥájí Mírzá Áqásí, who immediately ordered the transfer of the Báb to the castle of Chihríq.

It was during His imprisonment in Máh-Kú that the Báb wrote the most detailed and deeply informative of His tablets to Muḥammad Sháh, a Tablet which He opened with praises of the unity of God, His Apostles and the Twelve Imáms. This Tablet is the longest He ever revealed for a sovereign.

In this Tablet, the Báb unequivocally asserts the truth of His divine claim and the powers of His Revelation. The Báb quotes verses from the Qur’án and the Ḥadíths, prophecies of His Dispensation, but He also expounds upon His suffering and condemns the Sháh’s officials for their treatment of Him, particularly the sadistic Ḥusayn Khán in Shíráz.

In one of the passages of this Tablet the Báb condemns Ḥájí Mírzá Áqásí, and states He would prefer to be executed than imprisoned like a criminal:

“When I learned of your command, I wrote to the administrator of the kingdom: ‘By God! Kill me and send my head wherever you please because for me to live and be sentenced to the place of the criminals is not honorable.’ No reply was ever received since I am certain his excellence the Ḥajji [Ḥájí Mírzá Áqásí] has not fully brought the matter to your attention.”

But the Báb also movingly describes His solitude in the remote fortress:

“[I] swear by the Great Lord [The Prophet Muḥammad] that if you knew in what place I dwell, you would be the first to pity me. Amidst the mountain there is a fortress and there by your majesty’s favor I dwell. Its inhabitants are limited to two guards and four dogs.”

Partial Inventory ID: BB00079

The Báb revealed the Dalá'il-i-Sab’ih (The Seven Proofs), revealed in honor of Mullá Aḥmad-i-Kátib and Ḥujjat while He was incarcerated in Máh-Kú. The Dalá'il-i-Sab’ih is considered to be the Báb’s most important polemical work.

As the title indicates, in the Seven Proofs, the Báb discusses seven arguments according to which His Revelation is sufficient proof of the truth of His mission.

Responding to Mullá Aḥmad-i-Kátib, who had asked for proofs of His mission, the Báb answers with great clarity and precision, resting His argument on two verses of the Qur’án, putting forth new and original theological arguments of great importance, including a central argument on the unity of the Manifestations of God.

This point is central, and the Báb addresses it at the beginning of the Seven Proofs, explaining that each Manifestation of God is the return of all the past Manifestations of God, because they are all manifestations of the Primal Will of God:

“In the time of the First Manifestation the Primal Will appeared in Adam; in the day of Noah It became known in Noah; in the day of Abraham in Him; and so in the day of Moses; the day of Jesus; the day of Muḥammad, the Apostle of God; the day of the “Point of the Bayán”; the day of Him Whom God shall make manifest; and the day of the One Who will appear after Him Whom God shall make manifest. Hence the inner meaning of the words uttered by the Apostle of God, “I am all the Prophets,” inasmuch as what shineth resplendent in each one of Them hath been and will ever remain the one and the same sun.”

In the Seven Proofs, the Báb shares a prayer that was His constant supplication during His captivity in Máh-Kú about the protection of His Faith and Bahá'u'lláh:

“O my God! Grant to him, to his descendants, to his family, to his friends, to his subjects, to his relatives and all the inhabitants of the earth the light which will clarify their vision and facilitate their task; grant that they may partake of the noblest works here and hereafter! In truth, nothing is impossible to Thee. O my God! give him the power to bring about a revival of Thy religion and give life by him to what Thou hast changed in Thy Book. Manifest through him Thy new commandments so that through him Thy religion may blossom again! Put into his hands a new Book, pure and holy, that this Book may be free from all doubt and uncertainty and that no one may be able to alter or destroy it. O my God! Dispel through Thy splendor all darkness and through his evident power do away with the antiquated laws. By his preeminence ruin those who have not followed the ways of God. Through him destroy all tyrants, put an end, through his sword, to all discord; annihilate, through his justice, all forms of oppression; render the rulers obedient to his commandments; subordinate all the empires of the world to his empire! O my God! Humble everyone who desires to humble him; destroy all his enemies; deny anyone who denies him and confuse anyone who spurns the truth, resists his orders, endeavors to darken his light and blot his name!”

At the end of the prayer, the Báb added instructions to repeat it often, adding a prayer for protection for Bahá'u'lláh:

“Be awake on the day of the apparition of Him whom God will manifest because this prayer has come down from heaven for Him, although I hope no sorrow awaits Him…”

Click on the graphic below to watch an Utterance Project video of a short excerpt from the Seven Proofs in its original Arabic with English subtitles. This excerpt is a well-known prayer known as “Say: God sufficeth:”

Partial Inventory ID: BB00015

The Báb Himself affirms, while He was confined in Máh-Kú, that in the first four years of His ministry, His writings on a wide variety of subjects had amounted to more than 500,000 verses. The themes the Báb had addressed in these first four years were incredibly varied, from prayers to homilies, orations, Tablets of visitation, scientific treatises, doctrinal dissertations, exhortations, commentaries on the Qur’án and on various traditions, epistles to the highest religious and ecclesiastical dignitaries of Persia, and laws and ordinances for the consolidation of the Bábí Faith and the direction of its activities.

However, the greatest proportion of the Báb’s Writings, the emanations of His prolific mind, would see the light of day in Máh-Kú. During His nine-month confinement on the Open Mountain, and according to Bahá'u'lláh, the Báb revealed an incalculable numbers of epistles specifically addressed to the clerics of every city in Persia, as well as to those living in 'Iráq, in Najaf and Karbilá.

In these Tablets, the Báb outlined in detail where each of the cleric had committed errors.

According to the Báb’s amanuensis, Shaykh Ḥasan-i-Zunúzí, who was the one to transcribe the Báb’s Revelation in Máh-Kú, the Báb revealed at least nine commentaries on the entire Qur’án, works that are lost to us. In the words of the Báb Himself as quoted by Shoghi Effendi, one of these lost commentaries even surpassed, in some respects, the Qayyúmu'l-Asmá'.

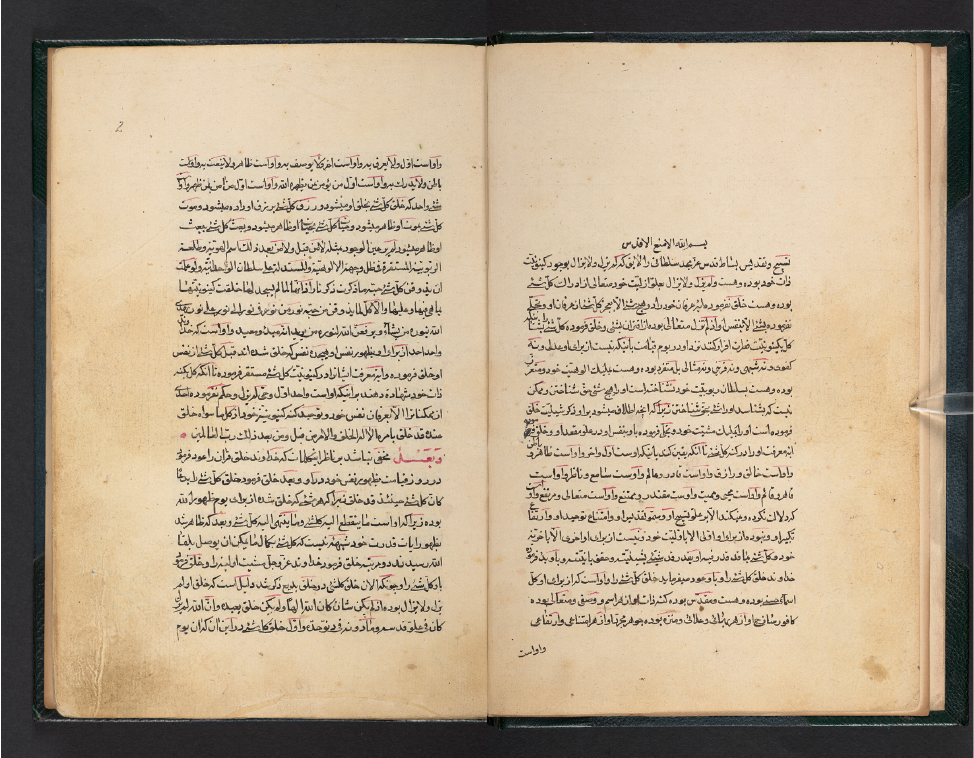

Two pages of the Persian Bayán from the manuscript held at the British Library.

Starting in July 1847, during His incarceration in Máh-Kú, and finishing sometime in 1849, in the fortress of Chihríq, the Báb devoted most of His time to the revelation of the Bayán-i-Fársí (The Persian Bayán, meaning “Exposition”), the most comprehensive and crucial of all of His Writings and the Mother Book of the Bábí Dispensation, in which He masterfully laid out the laws and ordinances of His Dispensation, and clearly foretold the advent of the Revelation of “Him Whom God shall make manifest.”

Perhaps most significantly, in the Persian Bayán, the Báb abrogates Islamic laws and traditions and sets down new laws and teachings for the Bábí Dispensation. Rather than simply abrogating and instituting laws, however, the Báb discusses laws as symbols with deep spiritual meaning, spiritual vehicles that can enable the Bábís to prepare for the advent of “Him Whom God shall make manifest.”

The Persian Bayán is a masterpiece of structure, a fine jewel of symmetry. The Báb revealed 9 units (or vaḥíds = “unities”) of 19 chapters (or bábs = “gates”), and the last vaḥíd (unit) has 10 chapters (bábs) instead of 19.

Both the perfect content and form of the Persian Bayán serve to prove the Báb’s thesis of the metaphysics of unity (vaḥíd): all things are manifestation of an inner reality, and that reality is the revelation of God within each created thing.

During His Revelation of the Persian Bayán, the Báb’s voice, so beautifully chanting these life-giving new verses, flowed down the mountain and the melody that streamed from His lips filled reached the ears and affected the hearts and souls of all who listened. The mountain and valley reverberated with His chant and the hearts of the people vibrated from His utterance.

In the third Vaḥíd of the Persian Bayán, the Báb explicitly references Bahá'u'lláh by name, a prophetic verse that constitutes one of the most significant statements every recorded in any of the Báb’s Writings:

“Well is it with him who fixeth his gaze upon the Order of Bahá’u’lláh, and rendereth thanks unto his Lord. For He will assuredly be made manifest. God hath indeed irrevocably ordained it in the Bayán.”

Partial Inventory ID: BB00001

The Báb revealed the Arabic Bayán between 1847 and 1849.

In the Bayánu’l-‘Arabí (The Arabic Bayán), the Báb reveals a condensed form of the Persian Bayán, which He couches in the language of “divine verses.”

At 23,400 words, compared with the 106,000 words of the Persian Bayán, the Arabic Bayán is roughly a fourth of its length, but its structure differs. Instead of 9 unities, it consists of 11, and all 11 unities have 19 chapters.

It is interesting to note that the Báb finished revealing the Persian Bayán at the point when He had revealed the 10th gate of the 9th vaḥid in the Arabic Bayán.

Therefore, all the supplementary gates and vaḥids of the Arabic Bayán (the ones that they do not share, given that the Persian Bayán ends at the 10th gate of the 9th vaḥíd) were all revealed after the Persian Bayán and are unique to the Arabic Bayán.

As with the Persian Bayán, the use of “gates” to designate the chapters of the Arabic Bayán is a crucial part of the symbolic structure of the two Holy Books. Each of the gates in the Persian and the Arabic Bayán symbolically represent a gate into paradise. Each gate of these books leads to the resurrection of the Bábí Faith in the appearance of Bahá'u'lláh, “Him Whom God shall make manifest.”

The Báb also equates the gates of both Bayáns to one day, as a further indication, present in the structure of the Holy Books themselves that each day should be devoted to the remembrance of the one Whose Advent the Báb has prepared the way for, that perchance they may be blessed to recognize Him when He proclaimed His mission to the world.

The Báb makes this point of each gate representing a day very clear in the Arabic Bayán:

“Verily the Bayán is Our conclusive testimony unto all things…We, verily, have ordained the gates [chapters] of this religion to be according to the number of all things, even as He arranged the numbers within the year. Unto each day belongeth a gate, that all things may thereby enter His exalted paradise and thus, within each unity [nineteen gates/days], by virtue of the mention of a single Letter of the Primal Letters, become “for God,” the Lord of the heavens, the Lord of the earth, the Lord of all things, the Lord of the seen and unseen, the Lord of creation…”

Partial Inventory ID: BB00020

A screen capture of 36 pages of a partial manuscript of 481 pages of the Kitábu’l-Asmá’ (The Book of Divine Names). The completed work is nearly one thousand times the length of the pages depicted in this image. Source: Archive.org.

At some point during His imprisonment in the fortress of Máh-Kú in 1847, the Báb began revealing the Kitábu’l-Asmá’ (The Book of Divine Names), which He would not complete until 1849 in the fortress of Chihríq.

The Kitábu’l-Asmá’ is a feat of Divine Revelation: it is the largest revealed book in the history of religion. It contains half a million words (500,000 words) and it is 3,000 pages long.

The Báb revealed the Kitábu’l-Asmá’ in 19 unities of 19 gates (chapters), for a total of 361 gates. To date, we have not yet found all the parts of this immense work.

In the Kitábu’l-Asmá’, the Báb expounds on various categories of human beings as being reflections of divine names and attributes and discusses ways in which all forms of reality can be spiritualized through the recognition of the supreme Source of divine revelation.

In one section of the Book of Divine Names, the Báb expounds on the name of God, the Most Perfect (Atqan) and counsels His followers to reflect the perfection of God’s handiwork in their own work. He first reveals this counsel in the mode of divine verses, quoted here, before expounding on it in the mode of prayer:

“Say! We verily have perfected Our handiwork in the creation of the heavens, earth, whatever lieth between them, and in all things; will ye not then behold?… Perfect ye then your own handiwork in all that ye produce with your hands working through the handiwork of God. Then would this indeed be a handiwork of God, the Help in Peril, the Self- Subsisting.Waste ye not that which God createth with your hands through your handiwork; rather, make manifest in them the perfection of industry or craft, be it a large and mass product or a small and retail one. For verily one who perfecteth his handiwork indeed attaineth certitude in the perfection of the handiwork of God within his own being”

Continuing on the theme of Divine Names, the Báb discusses the name of God “the Cultivator,” and explaining that farmers are as much reflections of God’s name the Cultivator. God is the Mighty Cultivator who plants seeds in the hearts of the faithful, and farmers are worldly cultivators who plant seeds in the earth, but both seeds need to bear fruit.

Click on the graphic below to watch an Utterance Project video of a short excerpt from the Kitábu’l-Asmá’ in its original Arabic with English subtitles.

Partial Inventory ID: BB00003

REFERENCES FOR PART IX

Escort to the far ends of the kingdom

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, page 124.

Messages from the Báb in Síyáh-Dihán

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, pages 124-125.

Síyáh-Dihán: Ḥujjat organizes a rescue attempt from Ṭihrán

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, pages 124-125.

Husayn Hamadani, The New History (tarikh-i-jadid) of Mirza Ali-Muhammed the Báb: Chapter on Zaján, translated by E. G. Browne, London: Cambridge University Press, 1893 (An 1880 History of the Báb based on the 1851 account), formatted by David Merrick.

Milán: A miracle and a near-escape

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, pages 126-127.

Before the end of the journey: Muḥammad Big asks for the Báb’s forgiveness

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, pages 125-126.

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, pages 127-128.

May/ June 1847: Forty days in Tabríz

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, page 128.

Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, pages 239-240.

19 July 1847: Arrival in Máh-Kú

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, pages 128-129.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, pages 129-131.

Summer and Autumn 1847: Changed circumstances in Máh-Kú

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, pages 131-133.

Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, pages 250-252.

Fereydun Vahman (Editor),The Bab and the Babi Community of Iran (2020), Chapter 1: The Báb: A Sun in a Night Not Followed by Dawn by Fereydun Vahman.

Resignation, grief, melancholy, joy, courage

Abbas Amanat, Resurrection and Renewal: The Making of the Bábí Movement in Iran (1844-1850), pages 373-375.

December 1847: An exceptionally brutal winter

Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, pages 251-253.

20 March 1848: ‘Alí Khán’s dream

Nabíl, The Dawn-Breakers, pages 255-257.

21 – 30 March 1848, Naw-Rúz: Mullá Ḥusayn is reunited with the Báb

Nabíl, The Dawn-Breakers, page 257.

A conversation between the Báb and Mullá Ḥusayn

Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, pages 258-259.

Abbas Amanat, Resurrection and Renewal: The Making of the Bábí Movement in Iran (1844-1850), page 379

30 March 1848: The Báb’s last farewell to Mullá Ḥusayn

Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, page 260 and page 417.

Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, page 259.

REVELATION: Epistle to Muḥammad Sháh III

Abbas Amanat, Resurrection and Renewal: The Making of the Bábí Movement in Iran (1844-1850), pages 373-375.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

REVELATION: Dalá’il-i-Sab’ih (The Seven Proofs)

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, pages 132-133.

Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, Chapter XIII, note 10 and note 13.

Nader Saiedi, Gate of the Heart: Understanding the Writings of the Báb, pages 35 and 267.

To read the English translation of The Seven Proofs by Peter Terry, please visit Bahá’í Library Online.

REVELATION: Epistles to the clerics of every city in Persia

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By and excerpt 2.

There is no information as to the whereabouts of either the Tablets to the clerics or to the Báb’s nine commentaries on the Qur’án.

REVELATION: July 1847 in Máh-Kú – 1849 in Chihríq: Bayán-i-Fársí (The Persian Bayán)

Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, pages 248-249.

Nader Saiedi, Gate of the Heart: Understanding the Writings of the Báb, page 35.

To read a summary and analysis of the Persian Bayán by Peter Terry, please visit Bahá’í Library Online.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

REVELATION: July 1847 in Máh-Kú – 1849 in Chihríq: Bayánu’l-‘Arabí (The Arabic Bayán)

Nader Saiedi, Gate of the Heart: Understanding the Writings of the Báb, pages 35 and 283-284.

To read the Arabic Bayán, translated into English by Peter Terry, please visit Bahá’í Library Online.

REVELATION: July 1847 – 1849: Kitábu’l-Asmá’ (The Book of Divine Names)

Nader Saiedi, Gate of the Heart: Understanding the Writings of the Báb, pages 36 and 337-338.

Escort to the far ends of the kingdom

Escort to the far ends of the kingdom