Written and illustrated by Violetta Zein

This part covers the life of the Greatest Holy Leaf from the age of 50 in 1896 to the age of 59 in 1905.

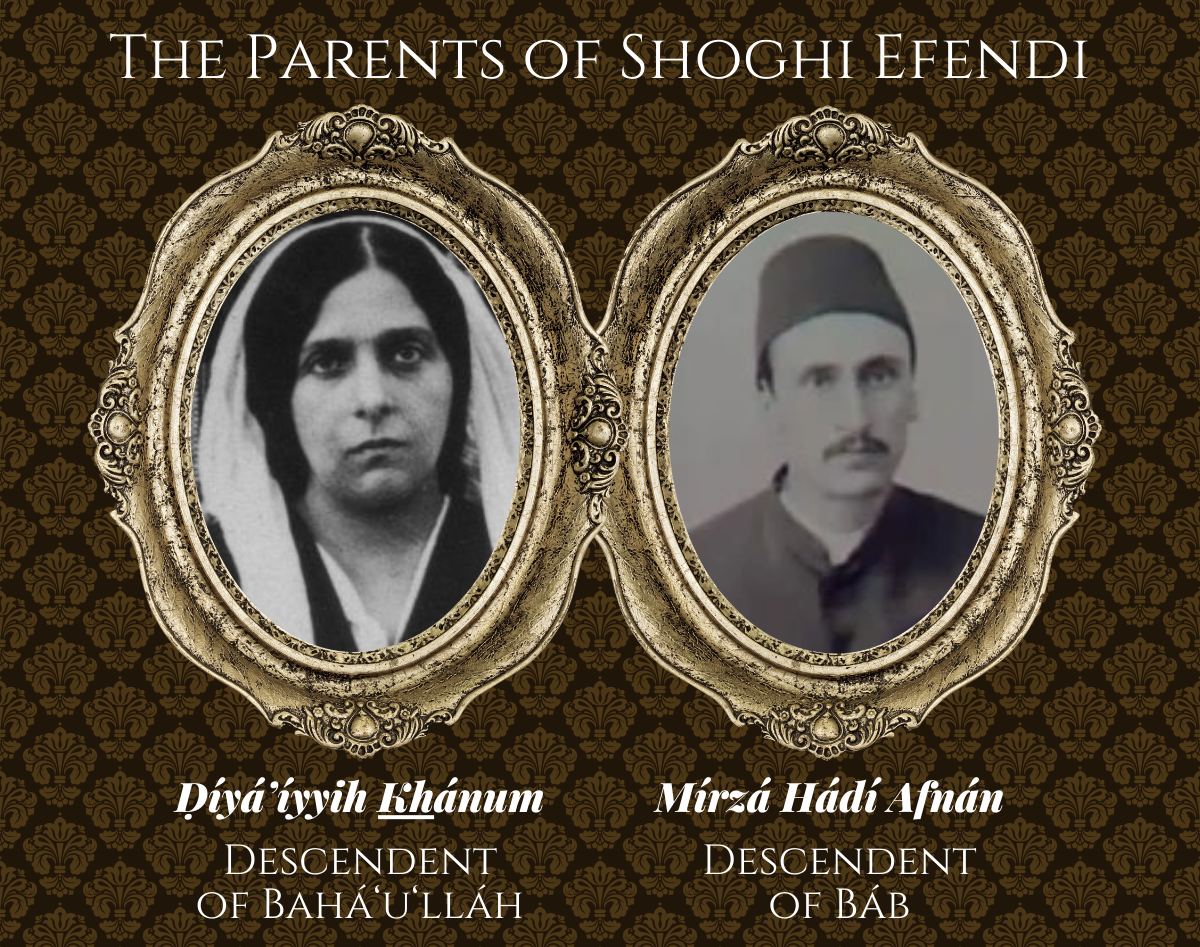

Left: Ḍíyá’íyyih Khánum, 'Abdu'l-Bahá's eldest daughter, mother of Shoghi Effendi. Source: Bahaipedia.

Right: Mírzá Hádí Afnán, the father of Shoghi Effendi. Source: Bahá'í Culture.

Khadíjih Bagum, the widow of the Báb, had asked Bahá'u'lláh for the honor of uniting the families of the Báb and Bahá'u'lláh in marriage, and Bahá'u'lláh had consented.

Khadíjih Bagum’s young nephew, Mírzá Hádí Shírází—who is sometimes also referred to as Mírzá Hádí Afnán—was interested in Bahá'u'lláh’s eldest granddaughter, Ḍíyá‘íyyih Khánum.

Bahá'u'lláh liked Mírzá Hádí. Bahá'u'lláh had once asked the Greatest Holy Leaf to tell 'Abdu'l-Bahá:

This young man Áqá Mírzá Hádí Afnán, is very good indeed, I think most highly of him.

Mírzá Hádí Shírází came on pilgrimage the year Bahá'u'lláh passed away in 1892 with his mother, and they returned to Shíráz.

After the Ascension of Bahá'u'lláh, Mírzá Hádí Shírází and his mother constantly wrote letters to 'Abdu'l-Bahá begging for the favor of the union, and expressing their desire for the marriage, with the mother emphasizing how much she loved Ḍíyá‘íyyih Khánum.

Mírzá Hádí Shírází had returned to 'Akká in 1896, after his pilgrimage four years before in 1892. He had come hoping to finalize his marriage with Ḍíyá‘íyyih Khánum.

Unfortunately, Mírzá Hádí Shírází arrived in 'Akká while 'Abdu'l-Bahá was away on a retreat in Tiberias, on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee, 45 kilometers (28 miles) away.

In 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s absence, there was no male head of the household.

The Greatest Holy Leaf was the one in charge of all matters related to the Holy Family.

For a household filled with women at the end of the 19th century with no male relatives to rely on was an enormously difficult task, as they were not free to move about. The Greatest Holy Leaf wrote to 'Abdu'l-Bahá in Tiberias requesting his consent for the wedding which Bahá'u'lláh Himself had approved of four years before.

'Abdu'l-Bahá responded from Tiberias, granting permission for the wedding, but He sent additional instructions that the wedding should be very simple, being so close to the Ascension of Bahá'u'lláh. He also revealed a special Tablet in Arabic for the wedding.

The wedding of Ḍíyá‘íyyih Khánum—granddaughter of Bahá'u'lláh—and Mírzá Hádí Shírází Afnán—the Báb’s nephew by marriage—united the families of the Twin Manifestations of God of the Bahá'í Dispensation.

It was also the wedding of the parents of Shoghi Effendi, the future Guardian of the Cause of Bahá'u'lláh, of whom 'Abdu'l-Bahá would write:

[The] primal branch of the Divine and Sacred Lote-Tree, grown out, blest, tender, verdant and flourishing from the Twin Holy Trees; the most wondrous, unique and priceless pearl that doth gleam from out the Twin surging seas…

Mírzá Hádí Shírází and Ḍíyá’íyyih Khánum were wed in a simple ceremony which took place under Bahíyyih Khánum's supervision, bringing joy to the hearts of the Holy Family.

In a gesture of kindness, Mírzá Muḥammad ‘Alí's family was invited to the simple wedding. They came and mocked the simplicity of the wedding with so much ridicule that none of the friends of the Holy Family were aware this was a day of celebration.

The house of ‘Abdu’lláh Páshá, 1920s. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2024.

Shortly after 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s return from His retreat in Tiberias and 4 years after Bahá'u'lláh's Ascension, the Holy Family moved to larger and more spacious quarters.

The house of 'Abbúd had become too small to accommodate the needs of a growing family and 'Abdu'l-Bahá had found the perfect solution.

'Abdu'l-Bahá arranged to rent the main building of the former Governorate of 'Abdu'lláh Pashá in the northwestern Mujádalih neighborhood of 'Akká.

The new house was adjacent to the army barracks where Baha'u'llah and His family had been imprisoned for two years between 1868 and 1870.

An antique 17th century dish of fine blue and white Chinese porcelain from the Ethnological Museum, Berlin. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Two years before the arrival of the first group of western pilgrims, 'Abdu'l-Bahá had a deeply significant dream.

Bahá'u'lláh appeared to Him and said:

I have guests that have never been here before. I want you to receive them most befittingly.

'Abdu'l-Bahá told His sister about the dream and together, He and the Greatest Holy Leaf retrieved the Holy Family’s fine dishes from the storage area and prepared them. These dishes had been sent to the Master by Ḥájí Mírzá Muḥammad ‘Alí-i-Afnán all the way from China.

'Abdu'l-Bahá shared the meaning of His dream with a Bahá'í named Hájí Muḥammad-Ismá‘il-i-Yazdí:

The standard of the Faith has been raised in America. A number in that country have embraced the Faith and will come here soon for pilgrimage to the Sacred Shrine of Bahá’u’lláh. These friends have never outwardly been here and will now come and share in this blessing.

Within two years, the first group of 15 western pilgrims, mostly from America, would arrive at the shores of 'Akká.

Background photo by Alina Sofia S. on Unsplash.

In an exceptional excerpt from one of His undated letters to His beloved sister, 'Abdu'l-Bahá offers a prayer in the name of Bahíyyih Khánum. It is a prayer for steadfastness and protection:

Grant, O Thou my God, the Compassionate, that that pure and blessed Leaf may be comforted by Thy sweet savours of holiness and sustained by the reviving breeze of Thy loving care and mercy. Reinforce her spirit with the signs of Thy Kingdom, and gladden her soul with the testimonies of Thy everlasting dominion.

Comfort, O my God, her sorrowful heart with the remembrance of Thy face, initiate her into Thy hidden mysteries, and inspire her with the revealed splendours of Thy heavenly light. Manifold are her sorrows, and infinitely grievous her distress. Bestow continually upon her the favour of Thy sustaining grace and, with every fleeting breath, grant her the blessing of Thy bounty.

Her hopes and expectations are centred in Thee; open Thou to her face the portals of thy tender mercies and lead her into the ways of thy wondrous benevolence. Thou art the Generous, the All-Loving, the Sustainer, the All-Bountiful

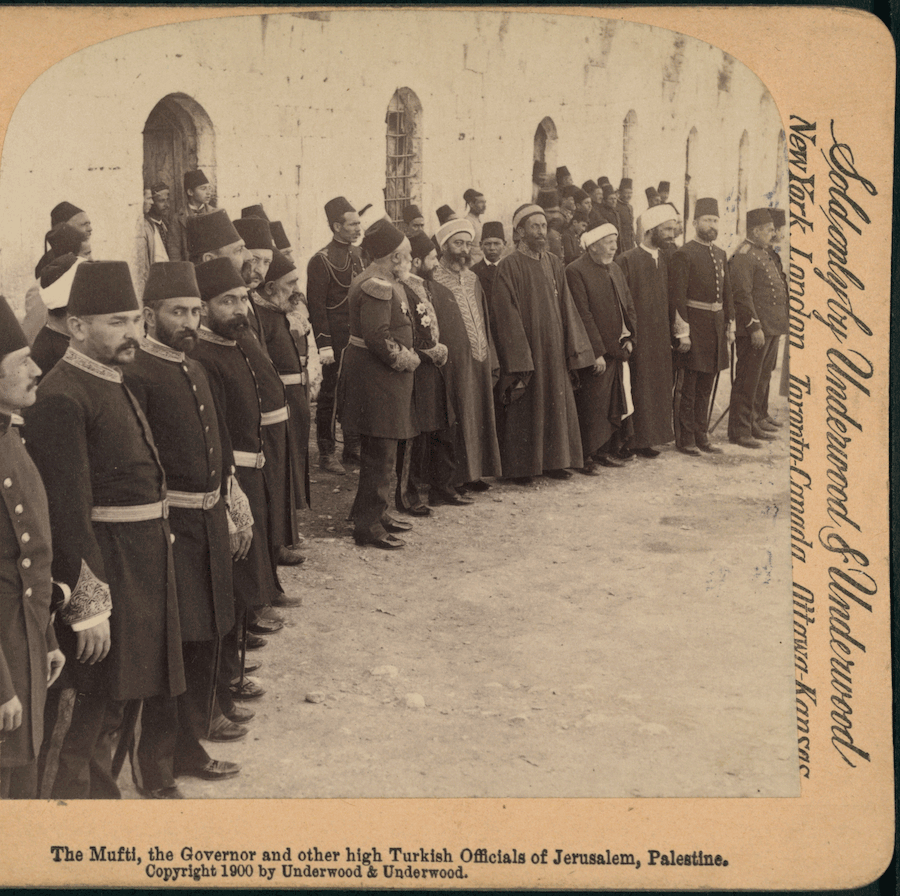

This photograph of the Mufti, the Governor and other high Ottoman officials of Jerusalem, Palestine circa 1900 probably closely resemble, in their dress and bearing, the authorities 'Abdu'l-Bahá would have met with in 'Akká, and whose wives the Greatest Holy Leaf would have visited in their homes. J.F. Jarvis, publishers. Library of Congress.

It is not very well-known that the Greatest Holy Leaf was fluent in three languages.

In addition to Persian, the Greatest Holy Leaf spoke fluent Turkish and Arabic.

Bahíyyih Khánum’s mastery of these three languages was an undeniable asset in 'Akká, where most of the population spoke Arabic, and because it was in the Ottoman Empire, most of the prominent people would have spoken Turkish.

Her language skills no doubt were instrumental in one of the Greatest Holy Leaf’s most important responsibilities, her contact with women of the higher social class in ‘Akká and later in Haifa.

Zeenat Khánum, the aunt of ‘Alí Nakhjávání who served the Greatest Holy Leaf for many years, said that whenever prominent persons such as the Mufti of ‘Akká, the Governor, or other high officials of the government called upon ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, He would ask the Greatest Holy Leaf, rather than His daughters or His wife, to visit the women in their homes while He entertained the men in His home.

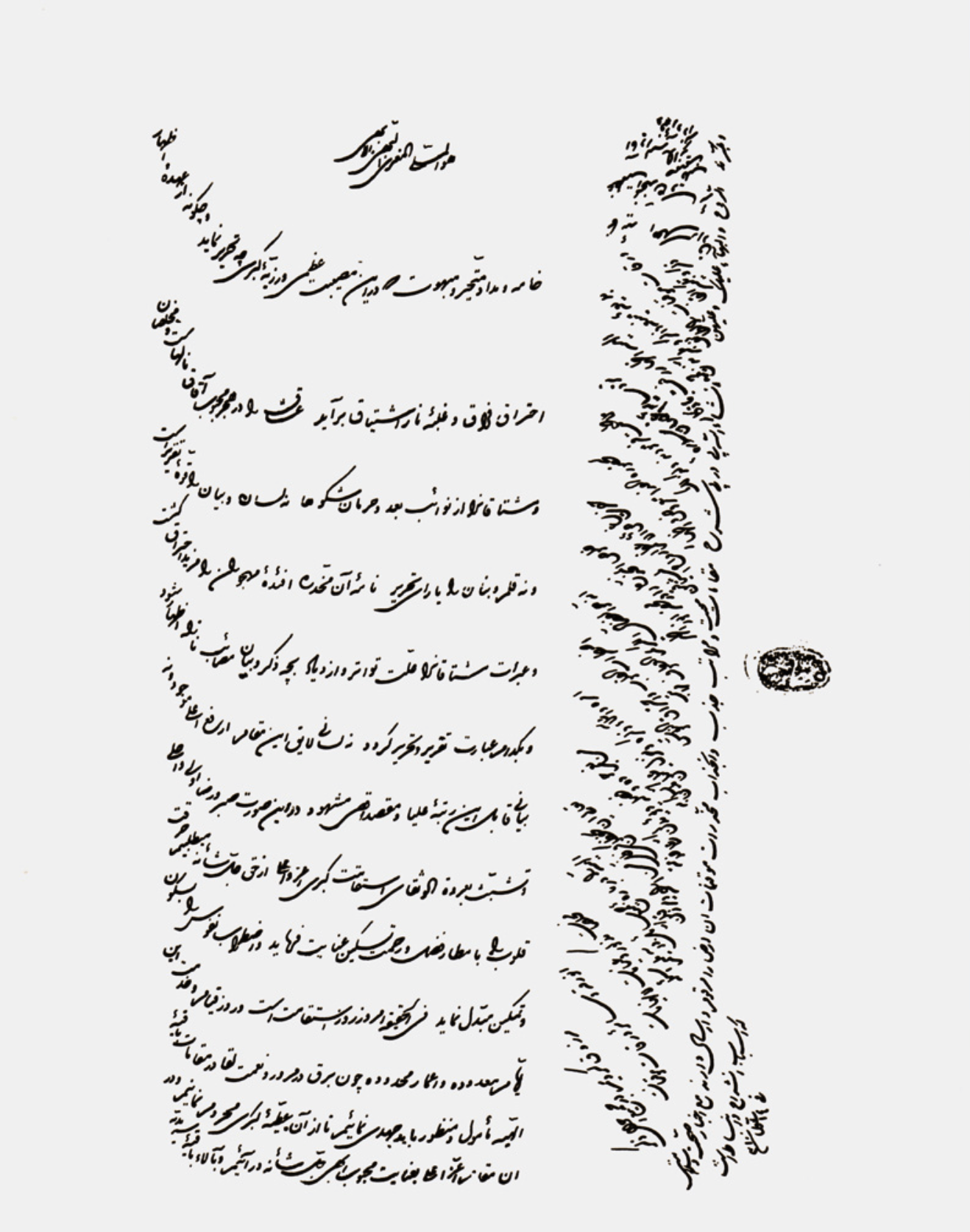

Facsimile of a letter written by the Greatest Holy Leaf. Dr. Bijan Masumian examined the letter and provides this detailed caption: “There is no date on the letter and no mention of an addressee(s). However, it is clearly shortly after the Ascension of Bahá’u’lláh. The Greatest Holy Leaf is inviting the recipient or recipients to steadfastness and calmness and encourages them not to worry.” Source: Bahá'í Sacred Relics.

‘Alí Nakhjávání in his recollections of the Greatest Holy Leaf makes a fascinating point. The Research Department of the Universal House of Justice made a study and review of the documents available to the at the Bahá'í World Centre and found that the Greatest Holy Leaf maintained an extensive personal correspondence throughout her life, and during the ministries of Bahá'u'lláh, 'Abdu'l-Bahá, and the Guardian.

The Research Department found letters written by the Greatest Holy Leaf during the last six years of Bahá'u'lláh’s life, between 1886, the year her beloved mother Ásíyih Khánum passed away, and 1892.

Likewise, the Research Department found letters which the Greatest Holy Leaf had written during the ministry of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, and more specifically, during the Master’s three-year extensive journeys to the west.

Late 19th century Chemist's shop formerly owned by N.F. Tyler. View of interior showing shelving and counters, and bottles in position. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Khalíl Shahídí was born in 1894 and spent four decades in the Holy Land, spending a great deal of time with 'Abdu'l-Bahá, the Greatest Holy Leaf, and Shoghi Effendi. He, his mother and other siblings were entrusted by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá as the custodians of the House of ‘Abbúd.

In his memoirs, he recounts the Greatest Holy Leaf’s healing abilities.

Bahíyyih Khánum used to prepare a simple drop for eye ailments, and whenever anyone came to her with a problem in their eye, when the drop was administered, their illness would be cured.

'Abdu'l-Bahá had the habit of saying:

Khánum must apply the drop with her own hands.

To Khalíl, the point 'Abdu'l-Bahá was making was that the reason for the cure was the Greatest Holy Leaf herself, not the remedy.

Khalíl also recounted that whenever any pregnant woman came to see the Greatest Holy Leaf, she would place her hands on the woman’s belly and, with a smile, tell her whether it was a boy or a girl, and suggest a name for the baby.

According to Khalíl, the Greatest Holy Leaf was always right.

After the Ascension of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, the Greatest Holy Leaf stopped naming children, telling the Bahá'ís:

Henceforth, parents should name their own children.

African grey parrot as a symbolic illustration of the Greatest Holy Leaf’s parrot, as we do not know which type of parrot it was. Photo by Ebrahim on Unsplash.

Zeenat Khánum, ‘Alí Nakhjávání’s aunt, worked in the house of 'Abdu'lláh Pashá and spent a great deal of time with the Greatest Holy Leaf.

According to Zeenat, the Greatest Holy Leaf had a parrot.

Bahíyyih Khánum would hold up a mirror to the parrot, and beckon the bird to say:

Ya Iláhí va Maḥbúbí! (O my God and my Beloved!)

And

Shoghi ján! (Shoghi dear!)

Early in the mornings at the house of 'Abdu'lláh Pashá, the entire household and Holy Family could hear the Greatest Holy Leaf’s parrot crying out in its high-pitched voice:

Ya Iláhí va Maḥbúbí! (O my God and my Beloved!) Shoghi ján! (Shoghi dear!)

Tutti the Parrot on the staircase of the Western Pilgrim House, as an illustration for the Greatest Holy Leaf’ parrot in the house of 'Abdu'lláh Pashá. Photograph taken by Arthur L. Dahl, and part of the © Gregory C. Dahl collection, used with permission for non-commercial purposes. Source: Gregory C. Dahl.

One morning, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was pacing in the courtyard of the house of 'Abdu'lláh Pashá and the parrot said:

Áqá! (Master!)

'Abdu'l-Bahá responded:

Yes?

Then the parrot replied:

Say, ‘Yá Bahá’!

Later, 'Abdu'l-Bahá went to the Greatest Holy Leaf and told her:

Khánum, we were about to give away this parrot, but he bought himself.

The Greatest Holy Leaf had saved her parrot by teaching him the right manners, and perhaps, also, the only right things to say!

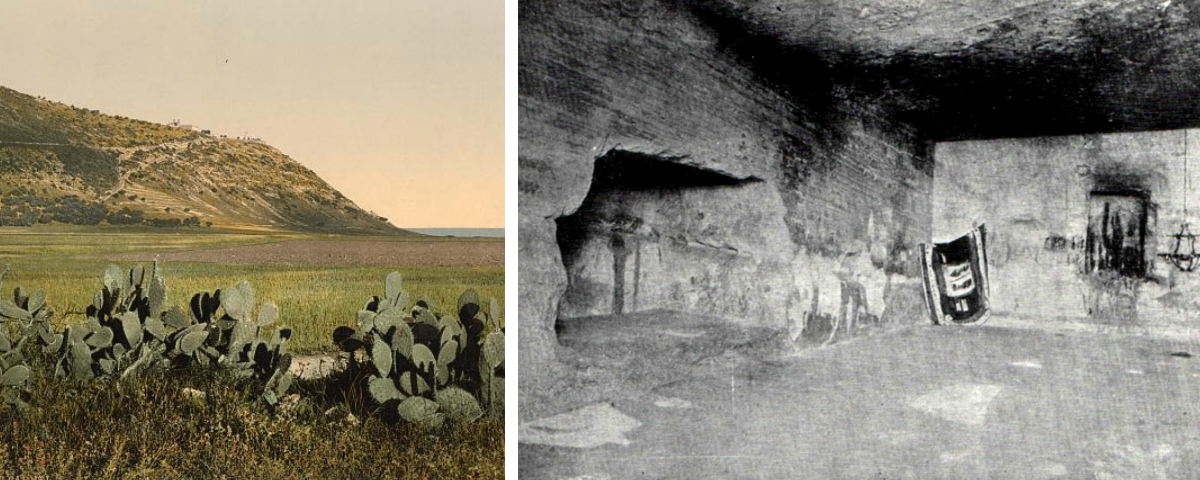

Left: A view of Mount Carmel, where the Cave of Elijah is located, photograph taken between ca. 1890 and 1900. Source: Library of Congress.

Right: The Cave of Elijah in 1893, at the time 'Abdu'l-Bahá visited it. Source: Ventura Daniel Wiki.

Between November 1896 and January 1897, the constant scheming and evil intentions of the Covenant-breakers had steadily intensified and had caused 'Abdu'l-Bahá and Bahíyyih Khánum deep sorrow and concern. For the third time in the early years of His ministry, 'Abdu'l-Bahá found Himself with no other choice but to retire to the lower Cave of Elijah on Mount Carmel in Haifa.

Once again, 'Abdu'l-Bahá entrusted the affairs of the Faith into the hands of His beloved and competent sister Bahíyyih Khánum, who acted as His deputy during His two-month absence.

This is a letter 'Abdu'l-Bahá wrote to Bahíyyih Khánum during His two-month absence:

My sister and beloved of my soul!

Here on the slopes of Mount Carmel, by the cave of Elijah, we are thinking of that Most Exalted Leaf, and the beloved and handmaids of the Lord.

We pass our days in writing and our nights now in communion with God, now in bed to overcome failing health. And although, to outward seeming, we are absent from you all, and far away, still our thoughts are with you always.

I can never, never forget thee.

However great the distance that separates us, we still feel as though we were seated under the same roof, in one and the same gathering, for are we not all under the shadow of the Tabernacle of God and beneath the canopy of His infinite grace and mercy?

Returning in January 1897, 'Abdu'l-Bahá arrived two months before a very happy event.

Shoghi Effendi was about to be born.

Shoghi Effendi as a young infant. Source: Bahaimedia

Shoghi Effendi was born on the first day of the month of fasting, 1 March 1897, in an upper room of the south wing of the house of 'Abdu'lláh Pashá in 'Akká.

He was 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s eldest grandson, the son of Mírzá Hádí Shírází and Ḍíyá‘íyyih Khánum, 'Abdu'l-Bahá and Munírih Khánum’s eldest daughter.

His name, Shoghi means “one who longs.”

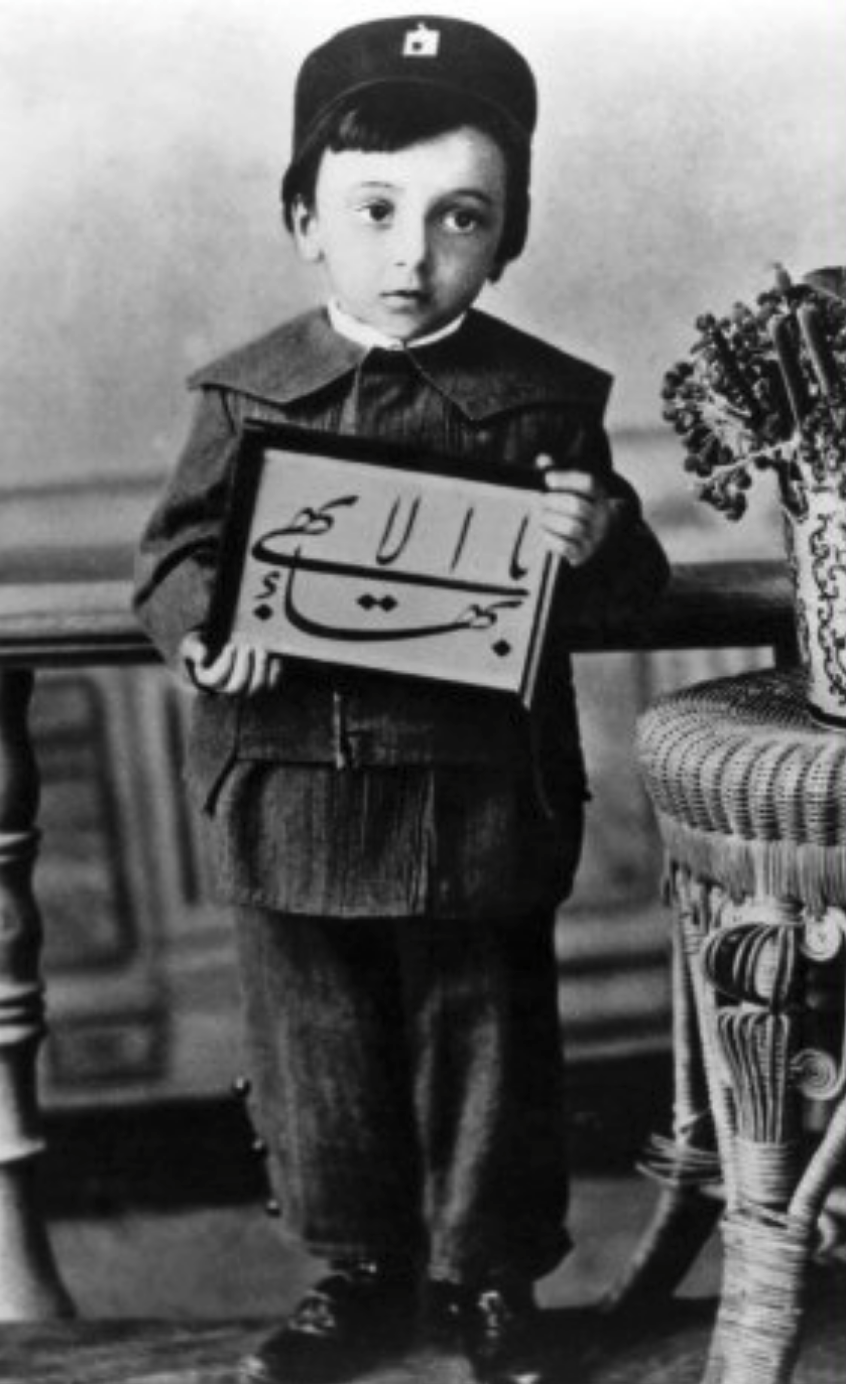

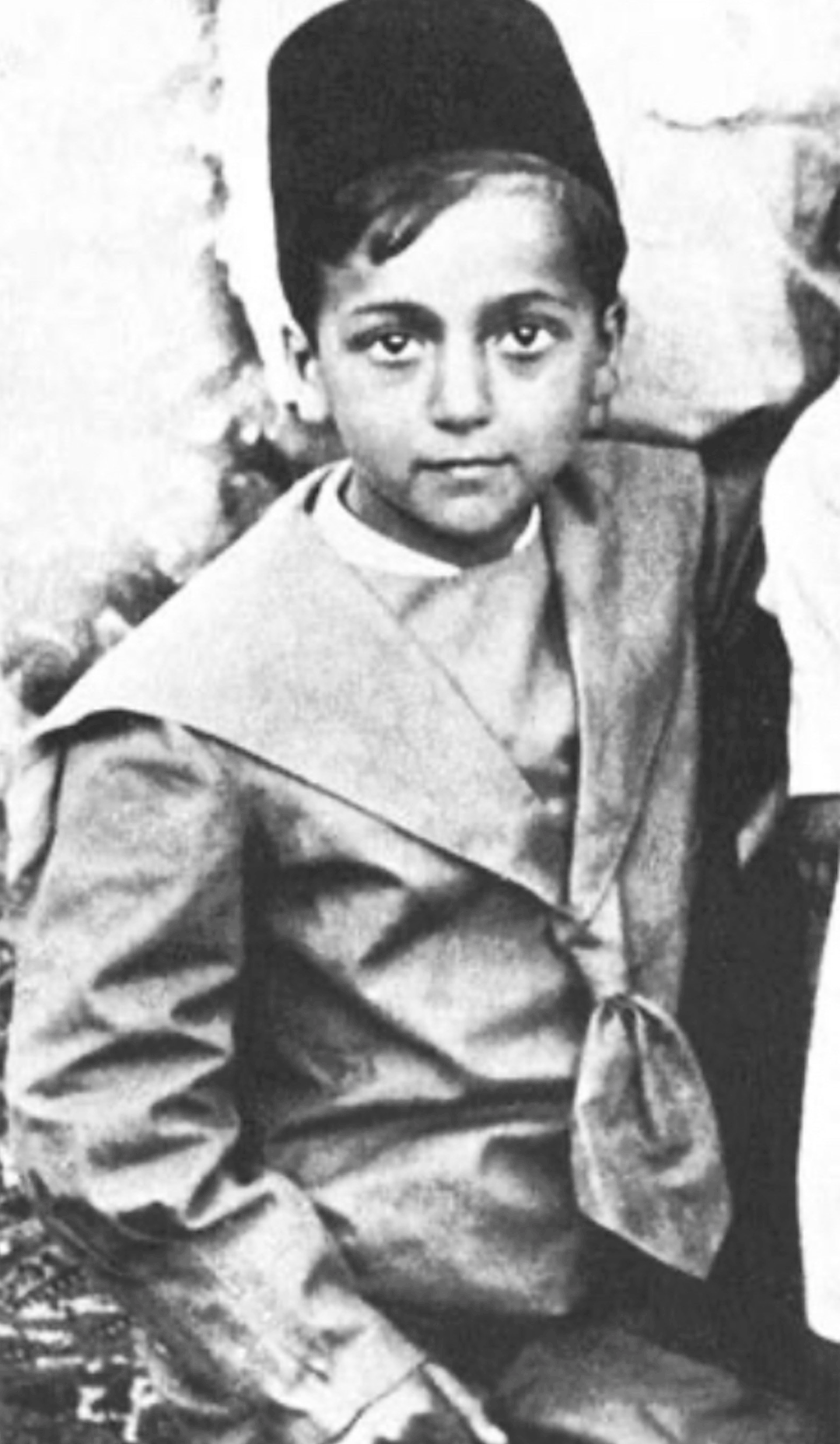

Shoghi Effendi in his very early childhood. Source: The Priceless Pearl.

Shoghi Effendi was the child of prophecy:

He was the “priceless pearl that doth gleam from out the twin surging seas,” the twin descendent of the family of the Báb, on his father’s side and of Bahá'u'lláh on his mother’s side.

But Shoghi Effendi was also born a prisoner.

At the time of his birth, 'Abdu'l-Bahá and His entire family were still prisoners of the Ottoman Sulṭán, ‘Abdu'l Hamid.

Shoghi Effendi was designated the Ghuṣn-i-Mumtáz, the Chosen Branch, and was descended from the families of two Manifestations of God, Bahá'u'lláh, on his mother Ḍíyá‘íyyih Khánum’s side, and the Báb, on his father Mírzá Hádí Afnán Shírází’s side.

This is why, in His Will and Testament, 'Abdu'l-Bahá emphasized his double divine heritage three times—speaking about the Twin surging seas, the Twin Holy Trees, and the fruit of the two offshoots of the Tree of Holiness—calling Shoghi Effendi: “the most wondrous, unique and priceless pearl that doth gleam from out the Twin surging seas,” “the blest and sacred bough that hath branched out from the Twin Holy Trees,” and “the youthful branch branched from the two hallowed and sacred Lote-Trees and the fruit grown from the union of the two offshoots of the Tree of Holiness.”

Shoghi Effendi was of the most distinguished and royal lineage.

On the side of his mother, he was the great-grandson of Bahá'u'lláh a Manifestation of God, and was descended from two additional Manifestations of God: Zoroaster and Abraham. He was also of royal Persian blood, a descendent of the Sásáníyán kings of Persia.

On the side of his father, he was born a Siyyid, a direct descendent of a yet a fourth Manifestation of God, the Prophet Muḥammad Himself.

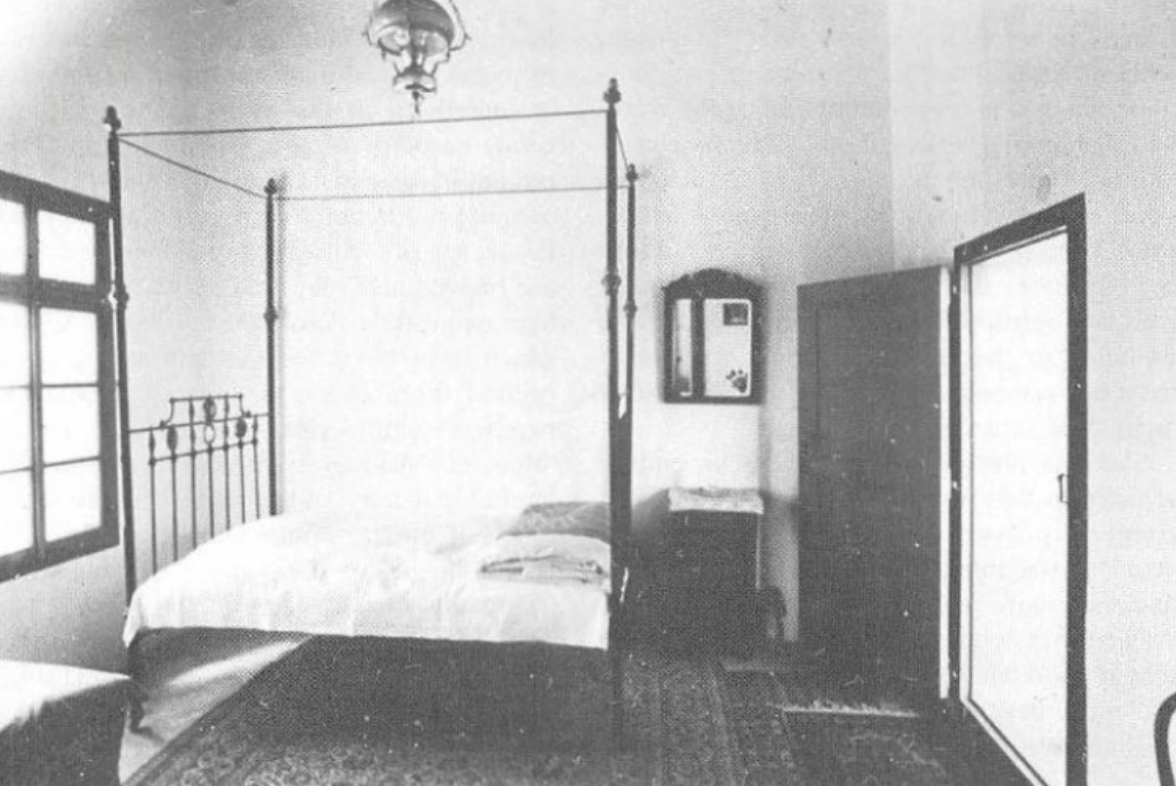

'Abdu'l-Bahá's room in 'Abdu'lláh Páshá. Bahá'í World Volume 18, page 95.

One night, while still an infant, Shoghi Effendi woke up crying and His loving Grandfather, 'Abdu'l-Bahá, asked his nurse to bring Shoghi Effendi to Him so that He could comfort him.

'Abdu'l-Bahá said to His sister, the Greatest Holy Leaf:

See, already he has dreams!

Background photo by Lauris Rozentals on Unsplash.

Bahíyyih Khánum, much like Bahá'u'lláh, 'Abdu'l-Bahá, and later Shoghi Effendi, felt physical pain and anguish when Covenant-breakers attacked the Faith.

Her intense sadness, as well as the depth of her knowledge of the situation are clear in this short excerpt from a letter she wrote sometime in 1897:

Should you enquire about these bereaved ones, through the grace of the Lord and the bounties of His divine Mystery, we are all well, but our grief knows no bounds.

We supplicate at the Threshold of the Eternal and Almighty Beloved that He may unlock before us the doors of delight, awaken the heedless and those deep in slumber, and grant the exponents of violation a sense of justice, so that its dust may settle down, that this dissension be wiped out, and once again we may taste the sweetness of the days of bliss.

This historical photo of some of the members of the group that made the first Western Pilgrimage in 1898. Wikimedia Commons.

Back row, left to right: Robert Turner, Anne Apperson, Julia Pearson.

Front row, left to right: One daughter of Ibrahim Khayrulla from his first marriage

Marian Khayrulla, his second wife, Ibrahim Khayrulla. Lua Getsinger, Ibrahim Khayrulla’s second daughter from his first marriage.

A year after Shoghi Effendi was born, another event of great significance in the history of the Faith occurred: the arrival of the very first western pilgrims, coming to 'Akká to visit 'Abdu'l-Bahá and perform their pilgrimage at the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh.

'Abdu'l-Bahá was at the time still a prisoner of the Ottoman Empire, and this large group of westerners were in essence, coming to visit a prisoner, so they had to come in different groups as a precaution.

The very first western pilgrims to arrive on 11 November 1898 was Ibrahim Kehiralla, who brought the Bahá'í Faith to the United States and raised up the American Bahá'í community before succumbing to his ego and eventually breaking the Covenant.

After Kheirallah, Lua and Edward Getsinger arrived on 8 December 1898.

One week after the Getsingers, probably sometime around 15 December 1898, Phoebe Elizabeth Apperson Hearst arrived in 'Akká. Phoebe Hearst had organized this pilgrimage and she was an American philanthropist, feminist and suffragist married to George Hearst, the patriarch of the Hearst dynasty.

Also arriving in 'Akká with Phoebe Hearst in mid-December 1898 were Amelia (Emily) Bachrodt, Phoebe Hearst’s maid, and Mary Virginia Thornburgh-Cropper, the daughter of Harriet Thornburgh, an American who became one of the first Bahá'ís in the United Kingdom.

Marian Kheiralla, Ibrahim Kheiralla’s wife arrived in late December 1898.

On 13 February 1899, two women arrived: May Bolles, a young American woman who had heard of the Bahá'í Faith through Lua Getsinger in Paris, and Harriet Thornburgh, a close friend of Phoebe Hearst and the mother of Mary Virginia Thornburgh-Cropper.

Seven days later, on 20 February 1899, three more pilgrims arrived: Anne Apperson, Phoebe Hearst’s niece, the daughter of her only brother Elbert, Julia L. Pearson, a young teacher working for Agnes Lane, the young cousin of Phoebe Hearst, and Robert Turner, Phoebe Hearst’s butler who would be the first African American to become a Bahá'í.

The last group of pilgrims arrived in early March 1899, one week after the previous group and included Helen Hillyer, one of Phoebe Hearst’s protégées and Ella Goodall.

Of these 15 pilgrims, 13 were women, with only 2 men.

Phoebe Apperson Hearst (1842-1919), first woman Regent of the University of California. Wife of George Hearst and mother of William Randolph Hearst, and the organizer of the very first Western pilgrimage to the presence of 'Abdu'l-Bahá in 'Akká in 1898. Photo taken prior to 1919. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

For Bahíyyih Khánum, the arrival of these women was an immense and very happy change in her life. The pilgrims stayed in the house of 'Abdu'lláh Pashá, and the women associated closely with the Greatest Holy Leaf and other members of 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s family.

By the time the western pilgrims arrived, 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s younger daughters were grown and spoke enough English to serve as translators for the pilgrims.

For the pilgrims, 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s sister Bahíyyih Khánum was the archetype of the perfect Bahá'í, and they were deeply touched and transformed by her self-effacement and sacrifice.

The arrival of the first Western pilgrims in the prison-city of 'Akká marked the opening of a new epoch in the development of the Faith in the West.

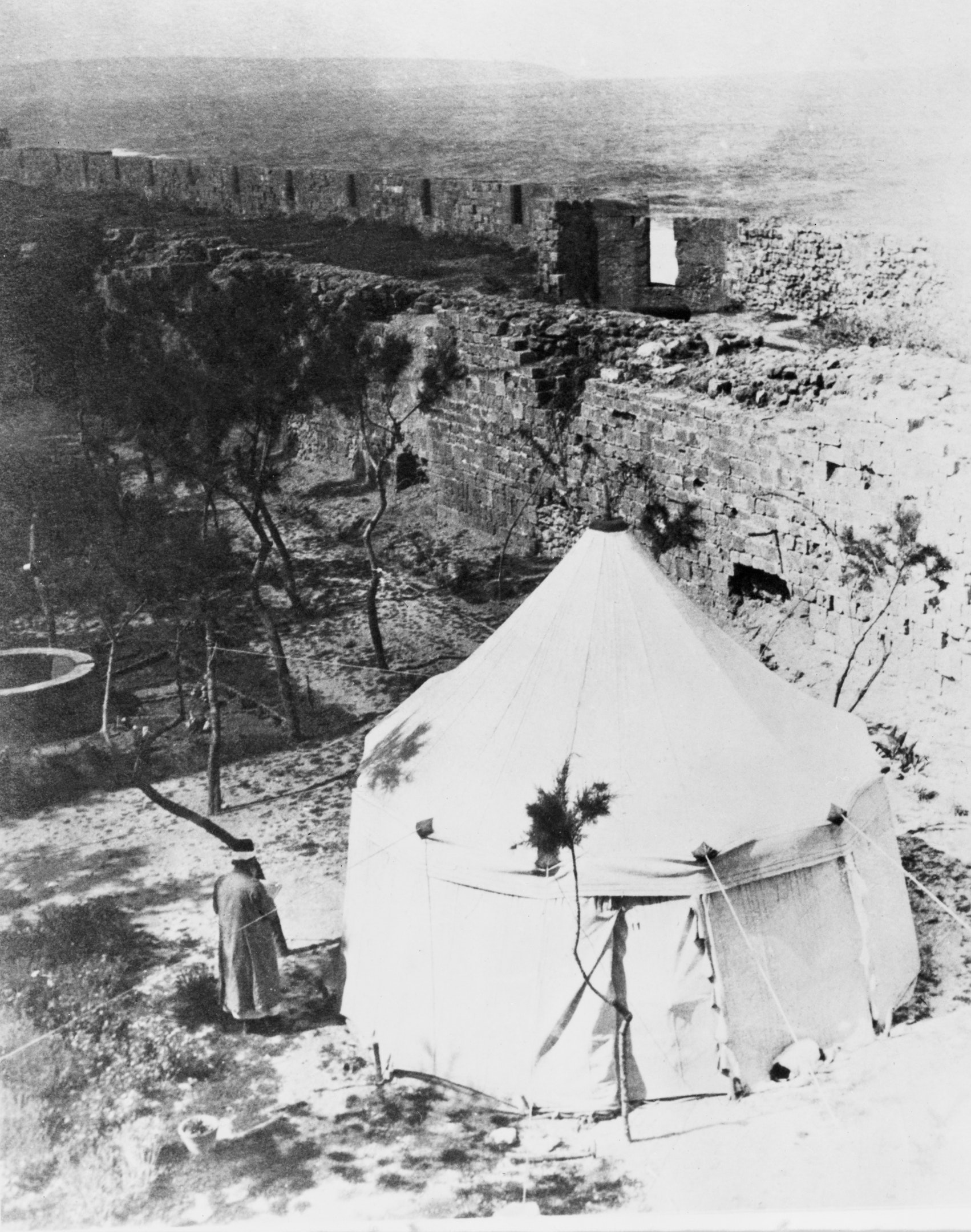

The tent of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá pitched in the courtyard of the House of ‘Abdu’lláh Páshá. Bahá'í Media Bank.

The arrival of the first Western pilgrims in the prison-city of 'Akká marked the opening of a new epoch in the development of the Faith in the West, and it had a profound and transformational impact on the pilgrims themselves.

Once the pilgrims had arrived in 'Akká, they experienced an intimate spiritual bond with 'Abdu'l-Bahá as the Center of Bahá’u’lláh’s Covenant. 'Abdu'l-Bahá Himself brought them to the innermost chamber of the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh. Although their visit was brief, 'Abdu'l-Bahá enfolded them in His loving-kindness, and powerfully infused them with a profound passion and dedication to the Faith and to Bahá'u'lláh through not only His inspiring words and counsels, but His example and love.

After their pilgrimage, these first western Bahá'ís would lead the way in establishing the Faith of Bahá'u'lláh in the western hemisphere.

Shoghi Effendi explained the worldwide impact of this extraordinary episode in the history of the Cause:

The return of these God-intoxicated pilgrims, some to France, others to the United States, was the signal for an outburst of systematic and sustained activity, which, as it gathered momentum, and spread its ramifications over Western Europe and the states and provinces of the North American continent, grew to so great a scale that ‘Abdu’l-Bahá Himself resolved that, as soon as He should be released from His prolonged confinement in ‘Akká, He would undertake a personal mission to the West.

An extraordinary impact of the western pilgrimages is shared with us by Shoghi Effendi, who states that the pilgrims’ presence in the Holy Land deeply affected Bahíyyih Khánum and the members of the Holy Family. It was through their arrival alone that the gloom that had enveloped the grieving members of 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s family was finally dispelled.

The visit of these first western pilgrims, according to Shoghi Effendi, had a lifelong healing and comforting effects on the Greatest Holy Leaf, which consoled and sustained her until the end of her life.

The pilgrims’ intimate personal contact with 'Abdu'l-Bahá, the Center of Bahá’u'lláh’s Covenant, transformed them all, except for the ambitious and combative Khayrulla who broke the Covenant upon his return to New York.

The returning Bahá'í pilgrims would teach and promulgate the Faith of Bahá'u'lláh in their homes and inspire other believers to travel and teach the Cause as well.

May Bolles after her first pilgrimage, around 1899. Source: We are Bahá'ís: May Ellis Bolles.

Female pilgrims had the bounty and honor of spending time with Bahíyyih Khánum and the women of the Holy Family, and this experience had a deep impact on them.

After they had disembarked at the port of Haifa, the pilgrims were taken by horse-drawn carriage to 'Akká, where 'Abdu'l-Bahá was still a prisoner of the Ottoman Empire.

May Maxwell remembered meeting 'Abdu'l-Bahá for the first time.

After they had stepped through a large stone doorway of the house of 'Abbúd which opened onto a square court and climbed the stairs to the upper floor.

There, by the window of a small room with a view of the deep blue Mediterranean Sea, they met 'Abdu'l-Bahá for the first time, immediately after which they had the bounty of meeting the Greatest Holy Leaf, Munírih Khánum and 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s daughters.

May Bolles (later May Maxwell) on the left and Edith McKay (later Edith de Bons) on the right. Source: Bahaimedia.

Bahíyyih Khánum and the women of 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s family welcomed the female pilgrims with love and tears of joy, as if they were welcoming old friends. They had given the pilgrims their own rooms, and provided them with every comfort, anticipated their every need, surrounded them with infinite care and attention.

It was a spiritual experience for the western women, to come into contact with such a celestial love. May Maxwell describes the experience:

…through it all shone the light of wonderful spirituality, through these kindly human channels their divine love was poured forth and their own lives, their own comfort, were as a handful of dust; they themselves were utterly sacrificed and forgotten in love and servitude to the divine threshold.

It is fascinating, through pilgrim notes such as May Maxwell’s, to be afforded a glimpse into the role of Bahíyyih Khánum and the women of the Holy Family with regards to western—and eastern, of course—female pilgrims.

For example, during their first visit to the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh, 'Abdu'l-Bahá led the pilgrims inside, and as they entered, the ladies of the Holy Family came in through a door on the other side of the Shrine and greeted the female pilgrims tenderly.

Ella Goodall. Source: Uplifting Words: Ella Goodall Cooper.

For Ella Goodall, after meeting 'Abdu'l-Bahá, her greatest privilege was meeting—in her own words—“His glorious sister” Bahíyyih Khánum.

One day, Ella Cooper joined the ladies of the Holy Family in the room of the Greatest Holy Leaf for early morning tea. 'Abdu'l-Bahá was there, sitting in His favorite corner of the couch which ran along the wall, and He was looking through the window on His right. The window looked over the ramparts of the city and to the blue of the Mediterranean Sea.

'Abdu'l-Bahá was revealing Tablets, and the room was filled with a quiet peace, punctuated by the lovely sound of the bubbling samovar, where one of the young maids of the household was brewing tea.

Ella Cooper found Bahíyyih Khánum’s personality unforgettable, and indelibly imprinted upon her memory. She describes the Greatest Holy Leaf as tall and slender with a noble bearing and provides a fascinating description of Bahíyyih Khánum’s energy:

…her body gave the impression of perfect poise between energy and tranquility, between wiry endurance and inward composure, imparting to the beholder a sense of security, comfort and reliance, impossible to describe.

Background photo by Michał Bielejewski on Unsplash.

To Ella Cooper, Bahíyyih Khánum’s beautiful face was the counterpart of her older Brother’s, 'Abdu'l-Bahá. The lines on her face, betraying a lifetime of suffering deprivations were softened by the patient sweetness of her mouth. The Greatest Holy Leaf’s dominating brow indicated to Ella a strong will and intelligence, illuminated by her wonderful and understanding deep blue eyes.

Bahíyyih Khánum’s face was deeply expressive, changing expressions from concerned and profound sympathy to sparkling laughter and joy, and the range of her emotions only served to deepen the irresistible spiritual attraction that the women felt in her presence.

Ella Cooper was very affected by the deep bonds of love with Bahíyyih Khánum and the women of the Holy Family, established in such a short time.

The last face she remembered from her momentous pilgrimage was that of the Greatest Holy Leaf, calm, gentle, radiant, her deep understanding eyes shedding the light of the Love of God upon the departing pilgrims, a light, she stated “which only glows brighter with the passing of the years.”

Ella Cooper’s pilgrimage memories are a testament to the spiritual presence and power of the Greatest Holy Leaf, who, even without speaking a word, imprinted herself on the consciousness and the soul of the pilgrims who had attained her presence.

Shoghi Effendi as a child. Source: The Priceless Pearl, between pages 40 and 41.

'Abdu'l-Bahá was occupied with revealing Tablets, and the room was quiet, with just the sound of the bubbling samovar, and the soft sounds of a young woman brewing tea. 'Abdu'l-Bahá looked up and asked Shoghi Effendi’s mother, Ḍíyá‘íyyih Khánum to chant a prayer. When she finished, the two-year-old Shoghi Effendi appeared in the doorway, immediately opposite His Grandfather, and Ella described the fascinating moment between Grandfather and grandson:Having dropped off his shoes [Shoghi Effendi] stepped into the room, with his eyes focused on the Master's face. 'Abdu'l-Bahá returned his gaze with a look of loving welcome it seemed to beckon the small one to approach Him.

Shoghi, that beautiful little boy, with his cameo face and his soulful appealing, dark eyes, walked slowly toward the divan, the Master drawing him as by an invisible thread, until he stood quite close in front of Him.

As he paused there a moment 'Abdu'l-Bahá did not offer to embrace him but sat perfectly still, only nodding His head two or three times, slowly and impressively, as if to say— "You see? This tie connecting us is not just that of a physical grandfather but something far deeper and more significant."

While we breathlessly watched to see what he would do, the little boy reached down and picking up the hem of 'Abdu'l-Bahá's robe he touched it reverently to his forehead, and kissed it, then gently replaced it, while never taking his eyes from the adored Master's face.

The next moment he turned away, and scampered off to play, like any normal child...At that time he was 'Abdu'l-Bahá's only grandchild... and, naturally, he was of immense interest to the pilgrims.

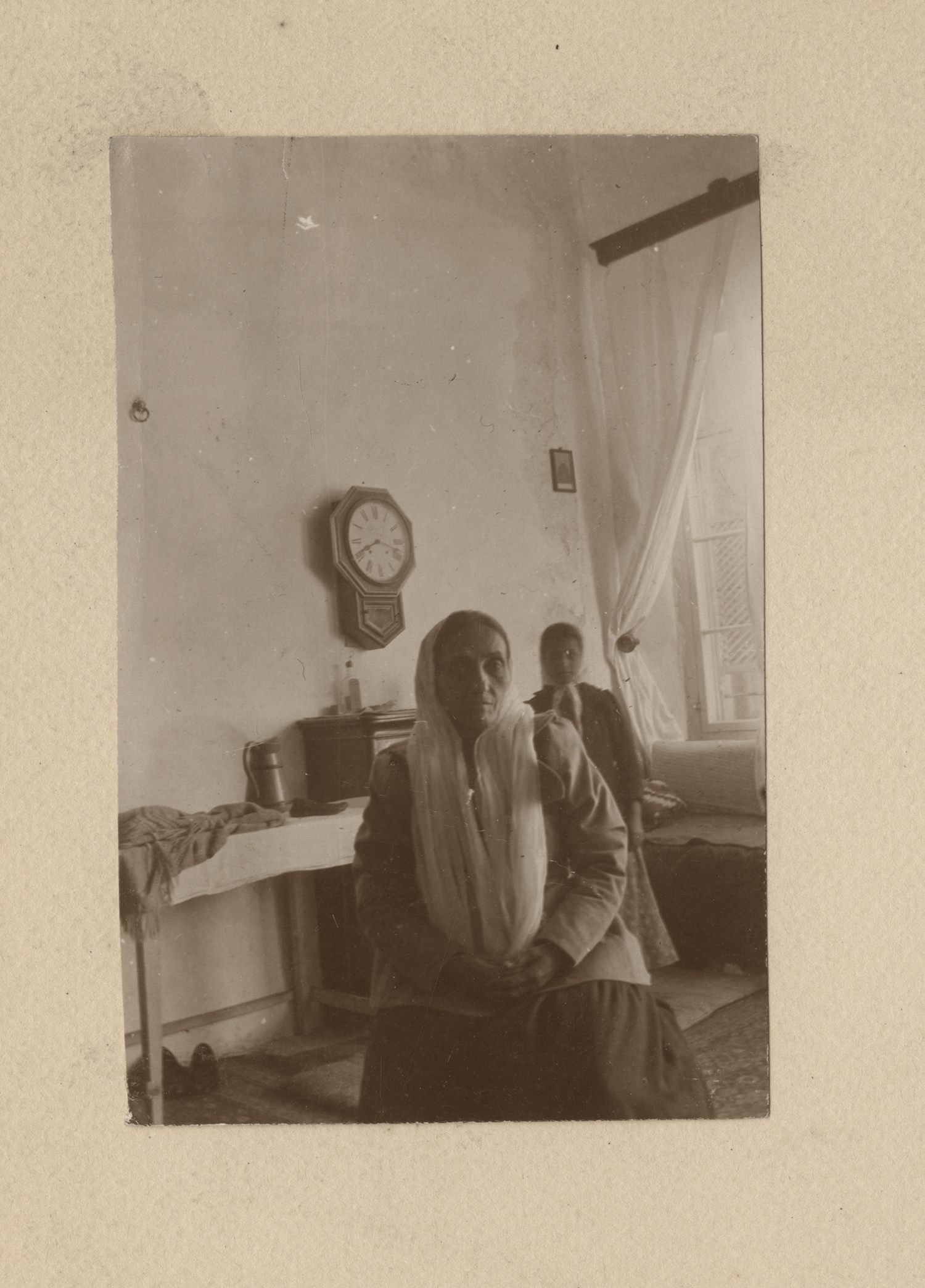

Original handwritten caption on the back of this photograph reads:

“The Greatest Holy Leaf, Bahíyyih Khánum, taken at her request 1899 'Akká. [Signed] E.C. Getsinger [Edward Christopher Getsinger]”NOTE: Two identical photographs are found in the United States National Bahá'í Archives, both captioned and signed by Edward Getsinger. One photograph is dated March 1901, and the other 1899. © United States National Bahá'í Archives, used with permission.

Lua and her husband Edward Getsinger arrived in 'Akká on 8 December 1898. They were the very first two North American Bahá’ís to come on pilgrimage to the Holy Land and meet 'Abdu'l-Bahá. The rest of the 13 Bahá'ís forming this first group of western pilgrims arrived over the course of several weeks.

Lua and Edward would stay in the Holy Land for more than 3 months, leaving around the middle of March 1899.

Her pilgrimage to the Holy Land, and most particularly being in the presence of 'Abdu'l-Bahá completely transformed Lua Getsinger. Before her pilgrimage, she had been a relatively carefree young woman and a passionate disciple of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, but after her pilgrimage, she was enkindled and on fire, and would serve the Faith until the very end of her life, expending all her energies in teaching the Faith and going on several special missions for 'Abdu'l-Bahá.

During her pilgrimage, 'Abdu'l-Bahá gave Lua a new name, Liva, meaning “Banner.” She would be a banner for the Faith of Bahá'u'lláh.

Some of Lua Getsinger’s most touching pilgrimage experiences involved Bahíyyih Khánum. When she first met 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s saintly sister, the Greatest Holy Leaf took her in her arms and kissed her sweetly on both cheeks. Lua was taken with Bahíyyih Khánum’s beautiful blue eyes.

Lua was moved by the Greatest Holy Leaf’s firm and loving presence, by her seemingly tireless energy and her immense inner strength. From Lua’s pilgrimage notes it is clear that Bahíyyih Khánum had a very powerful physical and spiritual presence and a deeply magnetic personality which made a profound impression on the women pilgrims.

For Lua, fully understanding that the Greatest Holy Leaf stood in rank second only to 'Abdu'l-Bahá was incredibly awe-inspiring. During her pilgrimage, Lua was told that Bahá'u'lláh once said of the Greatest Holy Leaf’s spirit that it was so pure, all her prayers found acceptance in the eyes of God.

Not surprisingly, the western pilgrims revered Bahíyyih Khánum and implored her to pray for them, certain beyond a doubt that all her prayers would find answers.

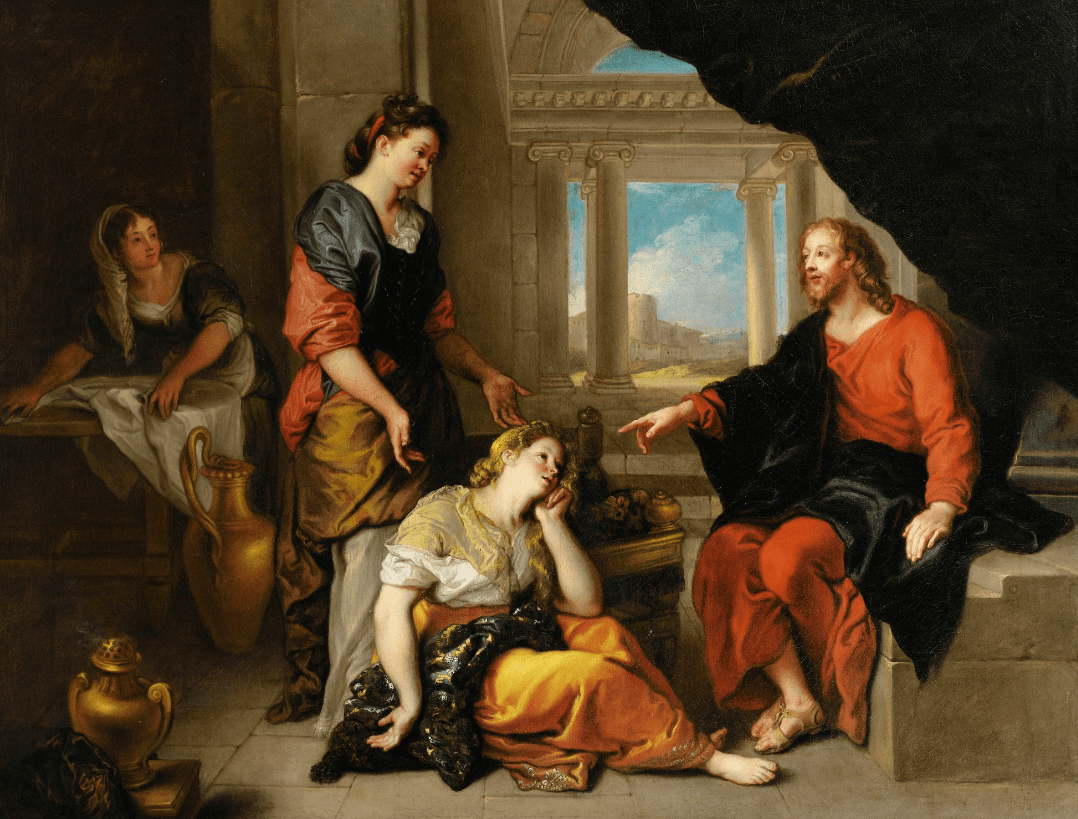

17th century painting by Charles de La Fosse of Jesus Christ at the home of Mary (Seated) and Martha (standing). Source: Wikimedia Commons.

But the Greatest Holy Leaf, despite her astonishing station and presence had a truly delightful quality of simplicity, what Lua called “the simplicity of the truly great.” This quality of Bahíyyih Khánum’s was what allowed to put anyone in her presence immediately at ease. But another important factor was her wonderful sense of humor.

In the household of the Holy Family, everything gravitated around the Greatest Holy Leaf. She always carried around with her a large set of keys and oversaw all the aspects of the domestic life in the house of 'Abbúd. Lua was struck at how the Greatest Holy Leaf seemed to always and at every moment strike the balance between practicality and spirituality.

'Abdu'l-Bahá had once been asked, between the two iconic Biblical characters Mary—deeply spiritual and always sitting at the feet of Jesus Christ listening to Him speak—and her sister Martha—profoundly practical and always busy serving—which was preferable.

His answer had been that Bahá'í women should strive to be both Mary AND Martha, and to Lua, the perfect example of this was the Greatest Holy Leaf.

What is extraordinary to meditate on is that Lua was so deeply affected by Bahíyyih Khánum, so aware of not only her station but her personality and her character, and yet she spoke no Persian and the Greatest Holy Leaf spoke no English.

The transformational relationship that affected Lua transcended human language, and was entirely the work of a more powerful spiritual language, which allowed the soul of the Greatest Holy Leaf to have an effect on this young American woman.

Lua wrote:

Each day we loved her more and drew closer to her, in spite of the fact that she spoke no English. We seemed to sense despite our own ignorance that she knew all about us, understood our spiritual needs and longings, and coming down to our level without the slightest hint of superiority, penetrated to our awakening souls and drew them forth to meet her own in the spirit of the most loving kindness, and her flashes of charming humor.

Lacquer cabinets in the International Bahá'í Archives on Mount Carmel holding the portraits of Bahá'u'lláh and the Báb. Source: The Life of Bahá'u'lláh, a photographic narrative: The portrait of Bahá'u'lláh.

Shortly before the pilgrims left the Holy Land, 'Abdu'l-Bahá arranged for them to view the portraits of Bahá'u'lláh and the Báb. It was the Greatest Holy Leaf’s special responsibility to be the custodian for the holy portraits of the twin Manifestations of God of the Bahá'í Dispensation: The photograph of Bahá'u'lláh, and the painted portrait of the Báb.

The photograph of Bahá'u'lláh was a seated photograph of Him taken in Edirne in 1868, when He was 51.

The portrait of the Báb at the age of 29 was painted in mid-end July 1848 in Urúmíyyih two years before His martyrdom as He was headed for His examination in Tabríz. The painter was Áqá Bálá Bayg, a local artist from a nearby town and was the chief painter of Malik-Qásim Mírzá, the Báb’s host in Urúmíyyih.

These holy relics were kept in a room in the house of 'Abbúd.

Before Ella Goodall, Helen Hillyer, May Bolles and the other pilgrims entered it, the Greatest Holy Leaf anointed each one of them with a drop of attar of roses on their forehead.

The sacred portraits had been placed on an eastern type of couch called a divan, and they were the very first items the pilgrims noticed. Each pilgrim slowly walked up to the pictures, kneeling down before kissing each one.

Then, in silence, they rose up and gazed at the portraits in deep reverence, praying and meditating.

Ella Goodall found the photograph of Bahá'u'lláh remarkable, His eyes holding her gaze with what she called “unmistakable power.” Ella felt that the photograph at least gave her a slight impression of what Bahá'u'lláh’s eyes might have been like in real life, and she was so entranced she could not look away.

May Bolles tears flowed while she was kneeling before the portraits and while she was standing before them. She wanted to remain in that state for the rest of her life.

None of the pilgrims wanted the sacred experience to end, but they were all brought back to the physical realm by 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s gentle touch on their shoulders, beckoning them to turn to the portrait of the Báb.

The Báb’s face in the portrait was beautiful and young.

After this moving experience, 'Abdu'l-Bahá addressed them loving parting words and guidance, and when He had finished speaking, the ladies of the Holy Family led them gently away.

They well understood that feeling of emptiness the women pilgrims were having at the thought of never seeing 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s face again, and they enfolded them in their arms, one after the other, comforting them in their time of separation from their Beloved.

May Maxwell states that experience was so powerful that it instantly changed their grief and loss into joy and radiance:

…as we drove away from the home of our Heavenly Father, suddenly His spirit came to us, a great strength and tranquillity filled our souls, the grief of bodily separation was turned into the joy of spiritual union.

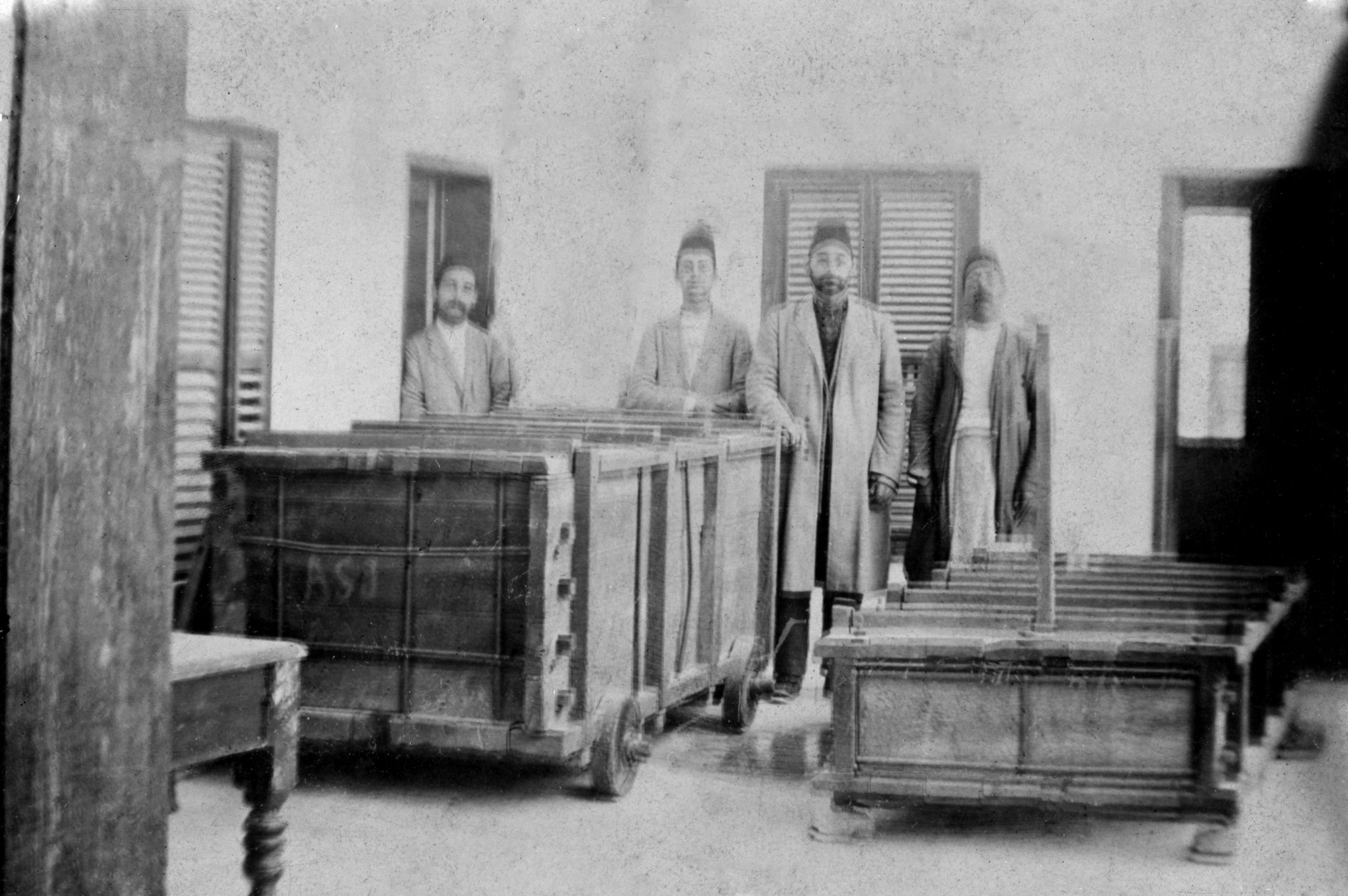

There is no photograph of the actual casket containing the remains of the Báb arriving in 'Akká but this is the large wooden crate containing the sarcophagus for the casket of the Báb in a house in Haifa some time before 1909. Source: Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2024.

In 1894, two years after a fresh wave of persecution was unleashed against the Bahá'ís in Persia in 1891-92, 'Abdu'l-Bahá had ordered the remains of the Báb moved to a new location until 1898, when 'Abdu'l-Bahá made arrangements for them to be carried to the Holy Land on foot from Ṭihrán to Beirut north of 'Akká, a distance of 1,830 kilometers (1,137 miles). Once in Beirut, they were to sail to 'Akká, a distance of 127 kilometers (19 miles).

A few days after arriving in Beirut, the Bahá'ís accompanying the casket boarded a small unscheduled Turkish boat leaving Beirut for 'Akká at the last minute and they arrived on 31 January 1899.

The Bahá'ís carried the casket containing the remains of the Báb through an empty customs office, tipped the lone guard standing watch, and the casket stayed for a few days in the home of a Bahá'í before being moved to the house of 'Abdu'lláh Pashá.

'Abdu'l-Bahá placed the casket in the room of the only person in the world He trusted with such a priceless treasure: the room of His sister, the Greatest Holy Leaf.

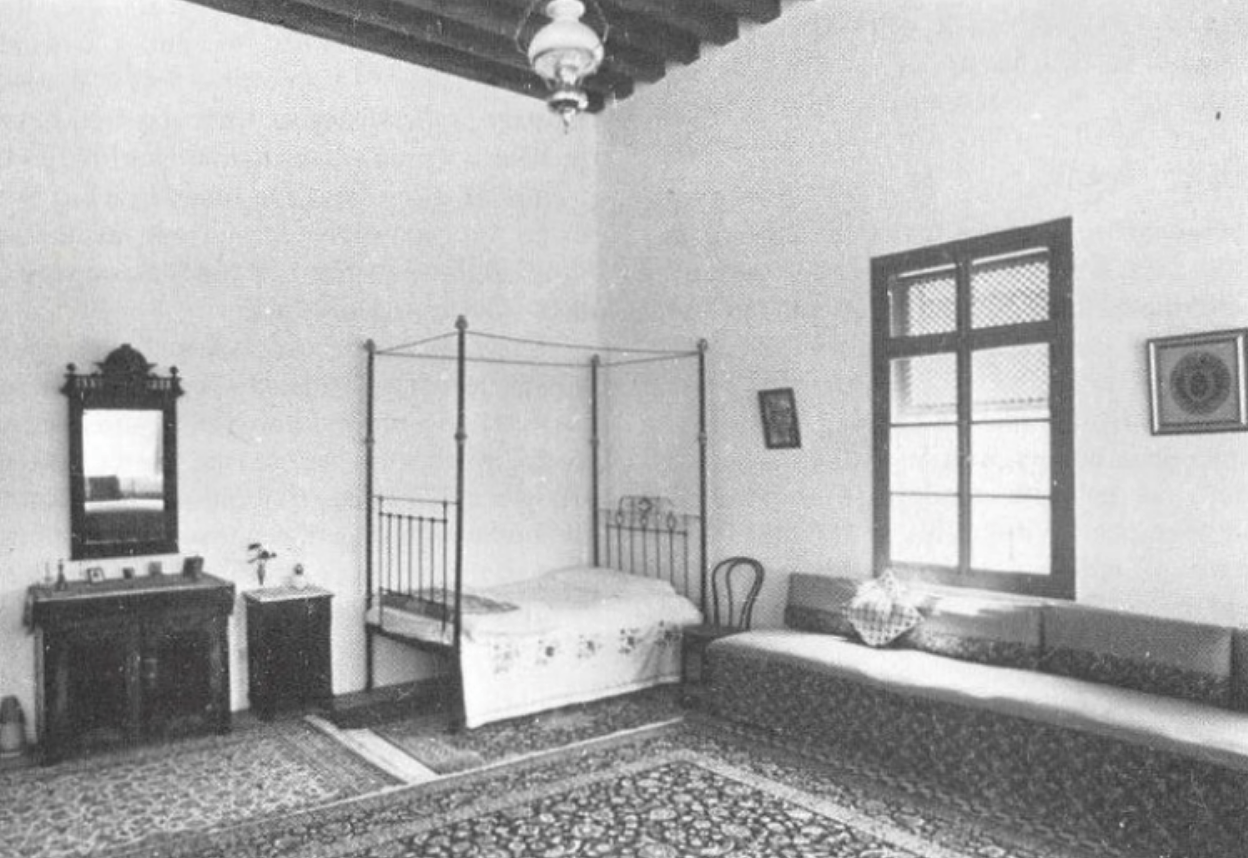

The Greatest Holy Leaf's room in the house of 'Abdu'lláh Páshá, where the remains of the Báb were stored for about a year. The Bahá'í World Volume 18, page 95.

For one year between 1899 and 1900, 'Abdu'l-Bahá kept the casket containing the remains of the Báb hidden in the room of the Greatest Holy Leaf.

In whose room, other than the room of the saintly daughter of Bahá'u'lláh, could the remains of the martyr-prophet of the Bábí Dispensation could have been kept?

There was no safer place.

There was no other person pure enough and trustworthy enough to keep watch over such a sacred trust.

Who else but the Greatest Holy Leaf already lived a life so spiritual, so reverent, that the casket containing the remains of a Manifestation of God could be kept in her room?

During the year that the Báb’s remains were hidden in her room, Bahá'ís noticed the Greatest Holy Leaf sitting in utter silence for hours on end on the divan that ran along one side of the room.

Fáṭimih Khánum, ‘Alí Nakhjávání’s mother, silent and immobile, would accompany the Greatest Holy Leaf in these moments, sitting at her feet, hour after hour.

It seems clear that, in Bahíyyih Khánum’s supremely spiritual understanding of the trust that 'Abdu'l-Bahá had placed in her, she considered her own room to have become the Shrine of the Báb for the year during which the Báb’s blessed remains were hidden there, and that she saw herself in the role of protector and custodian of such a treasure, while her beloved Brother was laying the foundation stone and building the actual Shrine on Mount Carmel.

After entrusting the remains of the Báb to His sister for about a year, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá needed to take further steps to protect the casket containing the sacred remains of the Báb.

The Master could not keep the casket in the house of 'Abdu'lláh Pashá, a house filled with so many people, resident and pilgrim Bahá'ís, family members, all coming and going constantly.

Around 1900, 'Abdu'l-Bahá moved the casket to a rented house in Haifa which 'Abdu'l-Bahá had originally intended for Western Pilgrims. 'Abdu'l-Bahá placed the casket inside the large marble sarcophagus which He had ordered from Burma for the interment of the Báb’s remains after the completion of the Shrine.

In Haifa, the casket was guarded by Bahá'í custodians 24 hours a day, and it would remain there until its interment nine years later in 1909.

Mírzá 'Abu'l-Faḍl and ‘Alí-Qulí Khán photographed in the United States in 1904, three years after ‘Alí-Qulí Khán’s stay in the Holy Land. Source: © United States National Bahá'í Archives.

‘Alí-Qulí Khán arrived from Persia in 'Akká in the spring of 1899 when he was 20 years old. He had only ever seen the youthful portrait of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, and when he arrived, and saw the Master’s face, he fainted. 'Abdu'l-Bahá had the exact face ‘Alí-Qulí Khán had always imagined Bahá'u'lláh had.

‘Alí-Qulí Khán would serve as 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s translator for two years. 'Abdu'l-Bahá was in fact—unbeknownst to the young man—training him for serving Mírzá 'Abu'l-Faḍl during his travels in Europe and North America.

The period during which ‘Alí-Qulí Khán lived in 'Akká was at the height of Covenant-breaking, and spies were everywhere. ‘Alí-Qulí Khán even believed they were being paid for each report they sent, and so had incentive to fabricate lies to send to the Ottoman government.

‘Alí-Qulí Khán worked both in 'Akká and Haifa. At the time, 'Abdu'l-Bahá had the habit of renting a house in the German Templer Colony, and sometimes Bahíyyih Khánum and the ladies of the Holy Family would also come to Haifa and care for the young man.

The young man was so eager to please 'Abdu'l-Bahá that he worked without stopping, and eventually burnt himself out. He became so weak that he could barely walk. Bahíyyih Khánum was the one who did the most for him in his time of need.

Sometime later, a young man cruelly hurt ‘Alí-Qulí Khán’s heart, telling him that the daughters of 'Abdu'l-Bahá did not like his work. His heart was broken, and he was brought back to life by the love of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, His tenderness, and His reminders of how much the Greatest Holy Leaf and the ladies of the Holy Family showered him with kindness.

Closeup of ‘Alí-Qulí Khán photographed in the United States in 1904, where he was accompanying Mírzá 'Abu'l-Faḍl. Source: © United States National Bahá'í Archives.

To ‘Alí-Qulí Khán, the Greatest Holy Leaf embodied all the perfections of a truly great woman, to him, she was a Lady.

Bahíyyih Khánum ran the household and oversaw meal preparation for crowds of visitors and pilgrims, to whom she was deeply kind and loving. For him, after 'Abdu'l-Bahá, there was no one else in the world possessed of such great dignity, majesty, humility and gentleness.

What moved ‘Alí-Qulí Khán the most was the silence of the Greatest Holy Leaf. She never spoke at length, and it was the starkest contrast with the eloquence of speech which 'Abdu'l-Bahá displayed.

'Abdu'l-Bahá’s role was to speak.

He was the Expounder of the Teachings of Bahá'u'lláh, the pilgrims came to the Holy Land to be educated, re-created, even.

And ‘Alí-Qulí Khán came to see this fascinating difference in temperament between brother and sister as a difference in station: he felt that 'Abdu'l-Bahá was the speaker and the revealer, and that Bahíyyih Khánum’s life was one of “continual silent service,” in his words.

Bahíyyih Khánum treated ‘Alí-Qulí Khán with so much kind attention, right down to very touching details. She knew that he had grown up in Persia, and knew he was probably missing the traditional summer drinks made from watermelon and other fruit, so she had some made for him.

Another time, Bahíyyih Khánum sent him a white umbrella so he could protect himself form the sun when he was walking.

During his time in the Holy Land, ‘Alí-Qulí Khán had the bounty of rendering service to the Greatest Holy Leaf by answering letters for her which had been sent from European and American pilgrims.

In 1901, he left 'Akká to perform the task 'Abdu'l-Bahá had prepared him for: to translate, interpret, and assist Mírzá 'Abu'l-Faḍl in his teaching trips to France and the United States.

Western Bahá'í pilgrims in ‘Akká in early 1901. Seated: Ethel Jenner Rosenberg, Madam Jackson, Shoghi Effendi, Helen Ellis Cole, Lua Getsinger, Emogene Hoagg; standing: Charles Mason Remey, Sigurd Russell, Edward Getsinger and Laura Clifford Barney. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

On 30 October 1900, Charlotte, Louise and Eleanor Dixon arrived on pilgrimage from Washington, D.C. and were taken to the house of 'Abdu'l-Bahá in Haifa, where they were welcomed by Lua Getsinger and Harriet Thonrburgh.

The Dixon family was introduced to Bahíyyih Khánum, the Greatest Holy Leaf, with a three-and-a-half-year-old Shoghi Effendi sitting in her lap.

Shoghi Effendi greeted the pilgrims with the only words of English he knew:

I love you very much.

Then, Shoghi Effendi chanted a prayer for them.

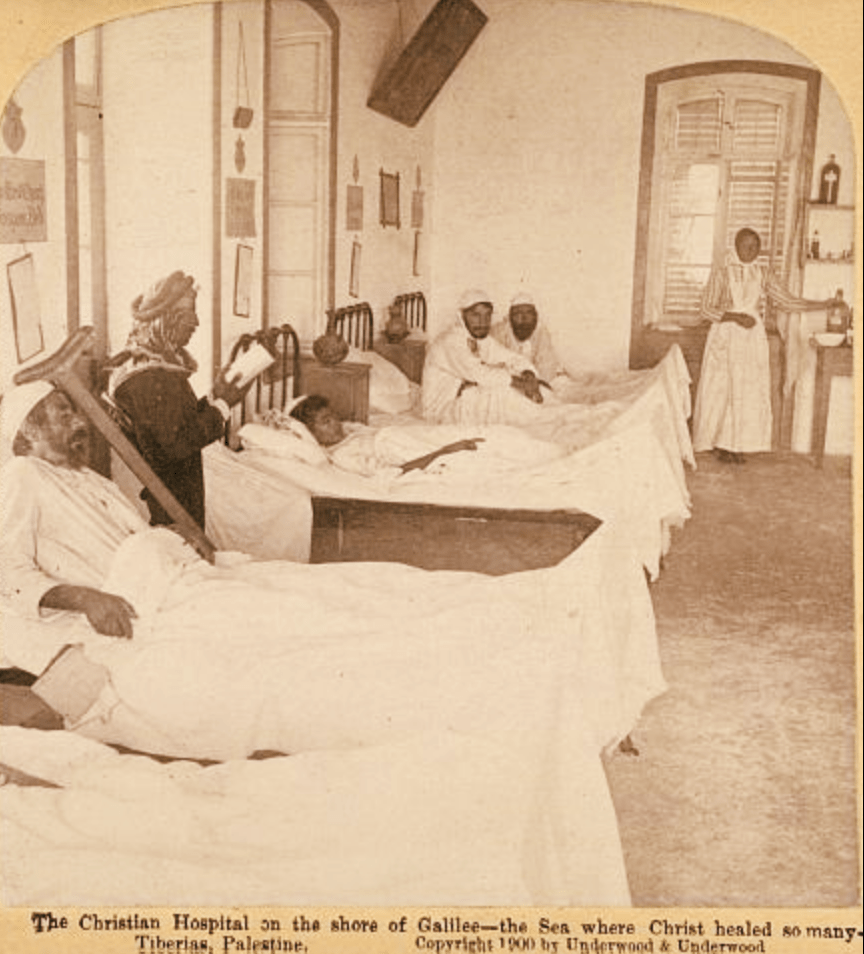

The Scottish Hospital in Tiberias, 1900, The hospital was founded by the Scottish doctor and missionary David Watt Torrance in 1894. Photograph by Underwood and Underwood. Source: Library of Congress.

'Abdu'l-Bahá had never been satisfied with the quality of physicians or medical care available in 'Akká.

Whenever a Bahá'í fell ill in the Holy Land, 'Abdu'l-Bahá always sent him to a doctor He handpicked Himself, and it was always the Master who paid for the consultation and medications.

At the time in 'Akká, people practiced medicine without degrees or formal training. The only two “real” doctors with degrees and trained abroad were the American Protestant physician who ran a missionary hospital, a Greek Cypriot from Istanbul, and two Arab doctors. But when it came to the members of the Holy Family, 'Abdu'l-Bahá never took risks and always sent them to Beirut, Lebanon for medical care.

Shortly after Dr. Youness Khan Afroukteh was called to 'Akká to serve Him in various capacities—around 1900—'Abdu'l-Bahá asked him to formally enroll in medical school, and Dr. Afroukteh left 'Akká for four months every year to complete his part-time medical degree in Beirut.

Before he left 'Akká the first time, 'Abdu'l-Bahá had told Dr. Afroukteh:

Go and get an education, maybe you can save us from these doctors. Who knows where we may be at that time?

The Greatest Holy Leaf and her niece Ḍíyá‘íyyih Khánum, the young mother of a three-year-old Shoghi Effendi, taken in Haifa in November 1900. This photograph was taken the same year that the Greatest Holy Leaf traveled to Beirut for medical care. © United States National Bahá'í Archives, used with permission.

Two months after Dr. Afroukteh had begun his medical studies, in the midst of learning the basics of anatomy and dissection, the Greatest Holy Leaf arrived in Beirut for medical treatment, accompanied by one of 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s daughters and Shoghi Effendi’s father, Mírzá Hádí Shírází.

Dr. Afroukteh rushed to the home of Muḥammad Muṣṭafá to welcome the members of 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s family and to pay his respects. Mírzá Hádí Shírází was very agitated and told Dr. Afroukteh:

[The Greatest Holy Leaf] has been visiting Dr. Debron for the last two days, but she is feeling quite poorly. She is experiencing severe dizziness and nausea and asks that you should write a prescription and give proper advice for the condition.

Dr. Afroukteh was at a loss.

He had only been in medical school two months.

He replied:

I have just begun the alphabet of medicine. How can I give any instructions when I know nothing?

Mírzá Hádí Shírází went to the Greatest Holy Leaf to convey Dr. Afroukteh’s message, and he came back with her very confident reply:

Whatever it takes, you must give some advice. It is her wish that you should prescribe medication.

Dr. Afroukteh racked his brain.

Nothing came to him.

Or rather, what came to him was doubt, helplessness, hopelessness, ignorance.

A third time, the Greatest Holy Leaf insisted that he treat her,

Mírzá Hádí Shírází pleaded with Dr. Afroukteh:

We have no power of our own. Healing comes from God. You prescribe something, maybe it is your good faith and strong devotion which she feels will properly guide you.

After this, Dr. Afroukteh threw himself instinctively into preparing a remedy.

He brewed a pinch of mint-like tea and asked that the Greatest Holy Leaf drink it with candied sugar, then waited for an hour. By that time, the Greatest Holy Leaf’s nausea was gone, and she prayed for Dr. Afroukteh with gratitude.

The next morning, Dr. Afroukteh was admitted into the presence of the Greatest Holy Leaf and he used the opportunity to offer her his best wishes for a speedy recovery.

The Greatest Holy Leaf had prepared a gift for the talented young doctor in training: it was a package of high-quality silk handkerchiefs, some candied sugar from the Holy Land, a bottle of attar of rose, and many kind words.

These gifts would be Dr. Afroukteh’s first fee for medical treatment in his long career in medicine.

A group of early western pilgrims including May Maxwell in the garden of Riḍván. Source : Bahá'í Heroes and Heroines: May Maxwell.

The love the western women pilgrims felt towards Bahíyyih Khánum was completely reciprocated.

In 1901, the Greatest Holy Leaf wrote a letter to a Bahá'í in the east, speaking about the impact of the first western pilgrims to 'Akká and the spiritual blessings their historic journey represented, as well as their enduring bond:

A number of your spiritual sisters, namely the handmaidens who have embraced His Cause, have arrived here from Paris and the United States on pilgrimage.

They recently reached this blessed and luminous Spot and have had the honour to prostrate themselves at His Holy Threshold and to behold the radiant face of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, the Centre of the Covenant of Almighty God— may my life be offered up as a sacrifice for His sake.

We have now the pleasure of their company and commune with them in a spirit of utmost love and fellowship.

They all send loving greetings and salutations to you through the language of the heart.

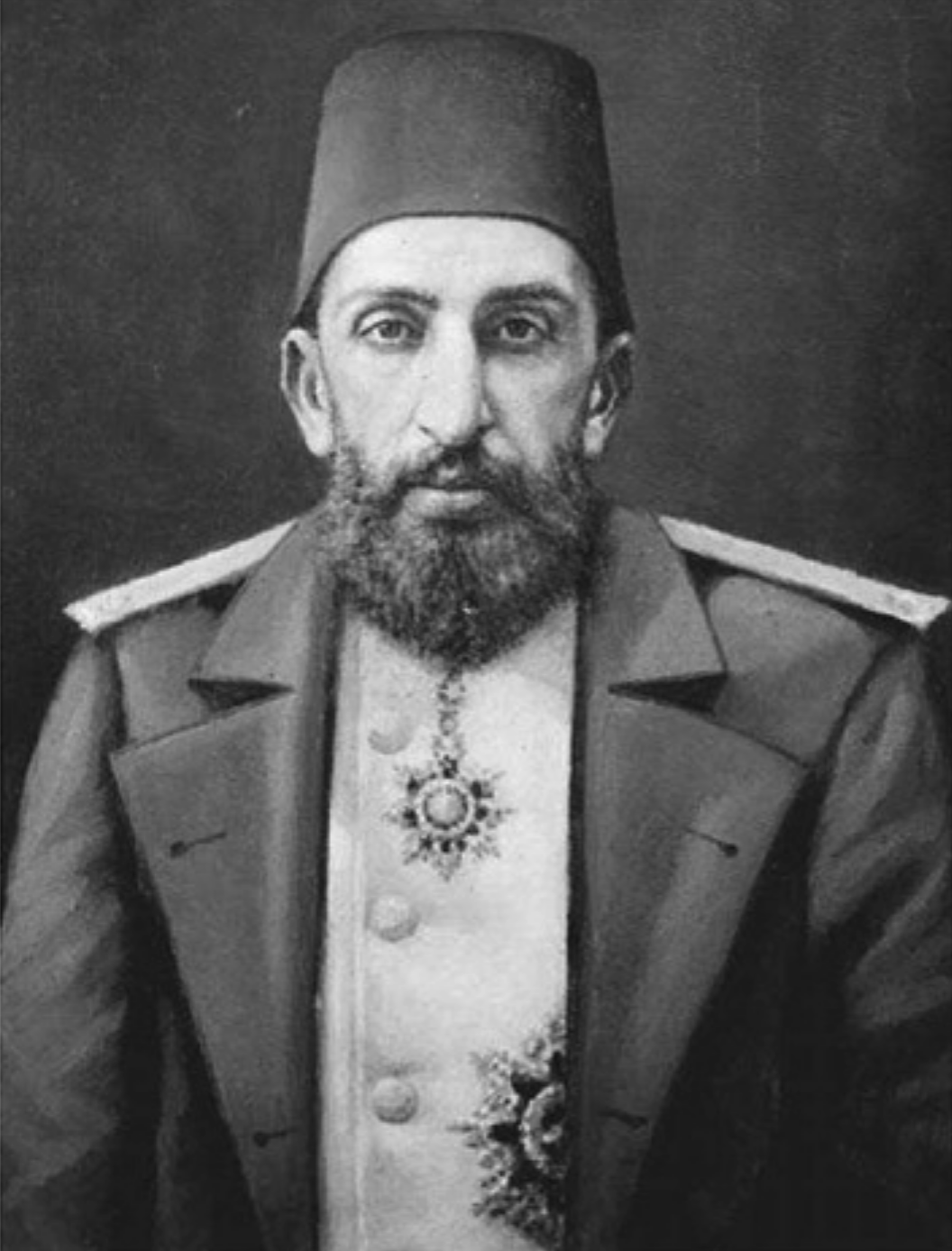

Sulṭán ‘Abdu’l-Hamíd II in January 1899. Wikimedia Commons.

Two years after the first American pilgrims left from the Holy Land in late 1898, the second major crisis of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s ministry erupted, a crisis which lasted on and off, with greater or lesser intensity for a period of 7 years until 1907.

In 1901, Sulṭán ‘Abdu’l-Ḥamíd II issued an edict ordering the reincarceration of 'Abdu'l-Bahá and the Bahá'ís in 'Akká, which went into effect in August 1901.

This edict was the direct consequence of Mírzá Muḥammad-'Alí’s incessant intrigues and monstrous representations about 'Abdu'l-Bahá and His work on erecting the Shrine of the Báb on Mount Carmel.

They wrote so many letters to the Ottoman Government that they succeeded in panicking officials and the Sulṭán.

The direct effect of 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s reincarceration in 'Akká was that He was deprived, for years, of the relative freedom He had experienced. The Holy Family and the Bahá'ís in the Holy Land, America, Europe, and Persia were filled with anguish and anxiety for 'Abdu'l-Bahá.

Another consequence of Mírzá Muḥammad-'Alí’s despicable actions was that he demonstrated more blatantly than ever before the degradation and infamy of his character and his actions.

In 1904 and 1905, a Commission of Inquiry would arrive from Istanbul to interrogate 'Abdu'l-Bahá.

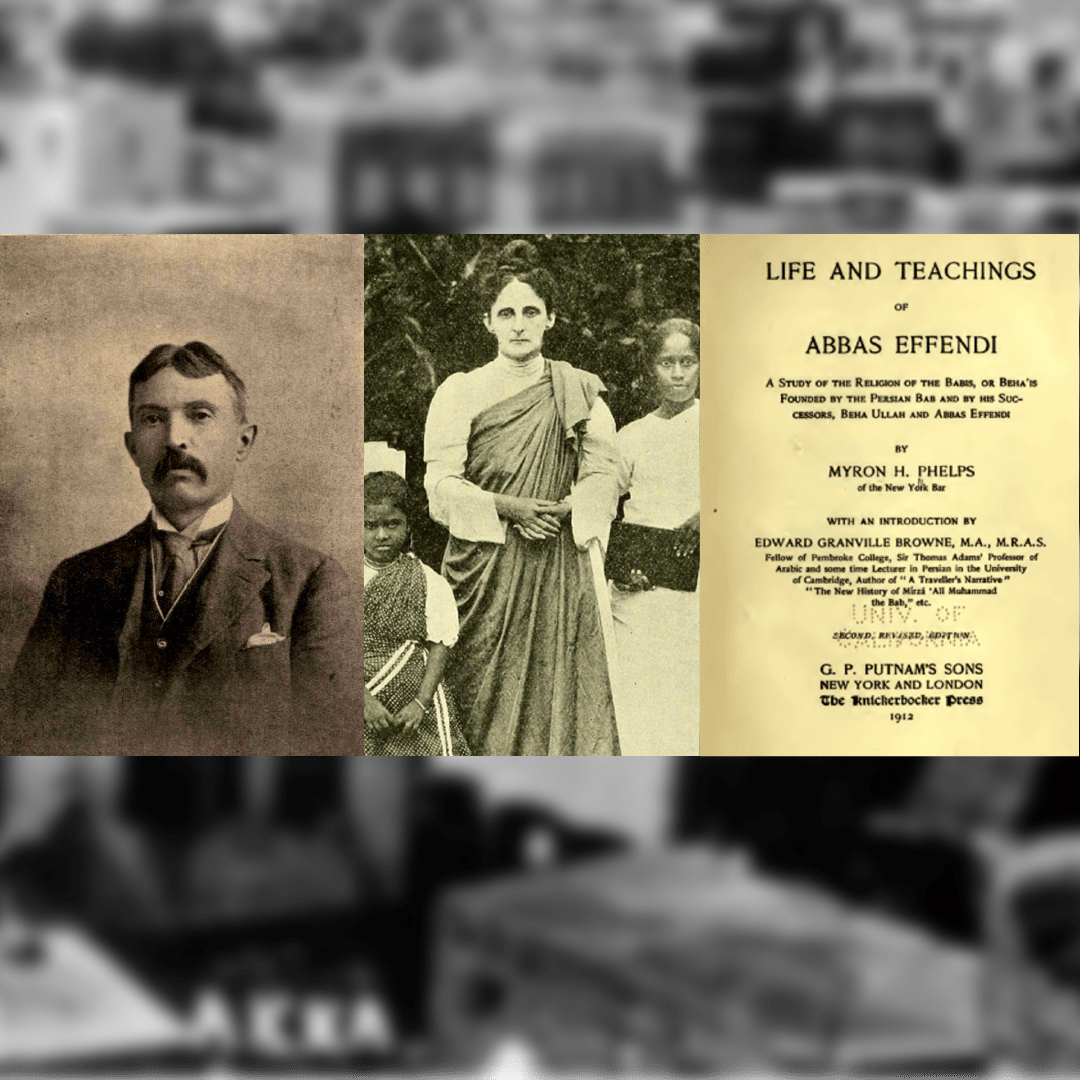

Left: Myron Henry Phelps. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Center: Countess de Canavarro towards the end of her life when she became a Buddhist nun and went by the name Sister Sanghamitta. Source: Arjunpuri in Qatar: How an American countess became a Buddhist nun and helped spread feminism in Sri Lanka.

Right: The book Myron Phelps and the Countess de Canavarro collaborated on: The Life and Teachings of ‘Abbás Effendi. Source: UC Merced: Hurqalya Publications: Center for Shaykhí and Bábí-Bahá'í Studies.

Myron Henry Phelps was a New York lawyer and religious writer. He was deeply interested in Buddhism and the Bahá'í Faith. In 1902, in the midst of 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s re-incarceration, Myron Phelps decided to investigate not only the teachings of the Bahá'í Faith but the person of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, and requested permission to travel to the Holy Land.

In December 1902, Myron Phelps and Miranda de Souza Canavarro, an American socialite, traveled to 'Akká, where they stayed for a month. Myron Phelps interviewed 'Abdu'l-Bahá extensively.

Because Mrs. Canavarro was a woman, she was able to conduct lengthy interviews of the Greatest Holy Leaf, gathering precious information Myron Phelps would not have had access to, as a man, as a westerner, and as a stranger to the family.

Mrs. Canavarro asked questions from Bahíyyih Khánum and received her answers with the help of a translator. The Greatest Holy Leaf’s answers were all transcribed within hours of each of her interviews with Mrs. Canavarro.

The book Myron Phelps published, dedicated to Mrs. Canavarro, The Life and Teachings of ‘Abbás Effendi, immediately became a precious resource for Bahá'ís specifically because of the precious nature of the Greatest Holy Leaf’s memories and recollections of her early life.

Myron Phelps published a second, very similar book in content without including the teachings content called The Master in 'Akká, also based on the testimony of the Greatest Holy Leaf.

Of particular interest in Bahíyyih Khánum’s chronicle are extraordinary details of Bahá'u'lláh and the Holy Family’s four successive exiles from Ṭihrán to Baghdad, Istanbul, Edirne, and finally to 'Akká.

Myron Phelps was ecstatic with his trip. He said, in his introduction to The Life and Teachings of ‘Abbás Effendi:

This month was one of the most memorable in my life…I made the acquaintance of Abbas Effendi who is easily the most remarkable man whom it has ever been my fortune to meet.

It is quite touching to note that Myron Phelps—though not a Bahá'í himself—understood the importance and great historical value of the work he had conducted. In his introduction, Phelps clearly states that the portion of the book comprising of the Greatest Holy Leaf’s testimony is the most precious part of his undertaking:

I shall first collect my observations and the information I have received from members of his family and others who were eye-witnesses of, or connected with, the occurrences referred to, bearing upon the life and character of Abbas Effendi. This I regard as perhaps the most important part of my present undertaking…This portion of the book will include a narrative by his sister, Behiah Khanum, of the life of Abbas Effendi and the fortunes of the family of his father, Beha Ullah, from the time when they left Teheran in 1852.

A modern photograph of an aerial view of the Shrine of Bahá’u’lláh, the Mansion of Bahjí, and surrounding gardens at night, bathed in a warm glow. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2024.

Lua Getsinger returned to the Holy Land in the Spring of 1903 to teach English to the Holy Family and took part in many Bahá'í activities.

On 28 May 1903, 11 years after the Ascension of Bahá'u'lláh, Lua had the great privilege to take part in the preparations for the solemn commemoration in the exalted company of the Greatest Holy Leaf and members of the Holy Family.

The night before the Ascension was a wonderful evening, there was no moon, but the sky was thickly studded with shining stars casting a warm mellow light.

The warm and humid Bahjí air was fragrant with roses and jasmine and they could see the dim lights of mountain villages in the distance.

Lua, the Greatest Holy Leaf and the women spent the long night walking in the garden surrounding the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh and under the stately pine trees nearby.

Later, the Greatest Holy Leaf and Lua went down below into the vault beneath the inner sanctum of the Shrine and lit all the lamps and candles around the sarcophagus containing the sacred and holy dust of Bahá'u'lláh.

As dawn began to break and the sky turned crimson and gold, they returned to the Shrine and knelt before the Holy Threshold in ardent prayer.

Lua had a profound realization:

At that moment I realized, as I never had before, what that departure meant to the inhabitants of the world and also what it meant to the angels in heaven!

Tears ran down all the women’s faces.

Overcome with deep spiritual emotion, some cried and some sobbed so intensely it shook their bodies.

Lua felt like she had received an inkling of the devastation Bahá'í’s family, friends, and mourners must have felt on the day of His Ascension, a little more than a decade before.

Ârif Bey (1882 – 1926), head of the second Ottoman commission of inquiry. Source: Wikidata.

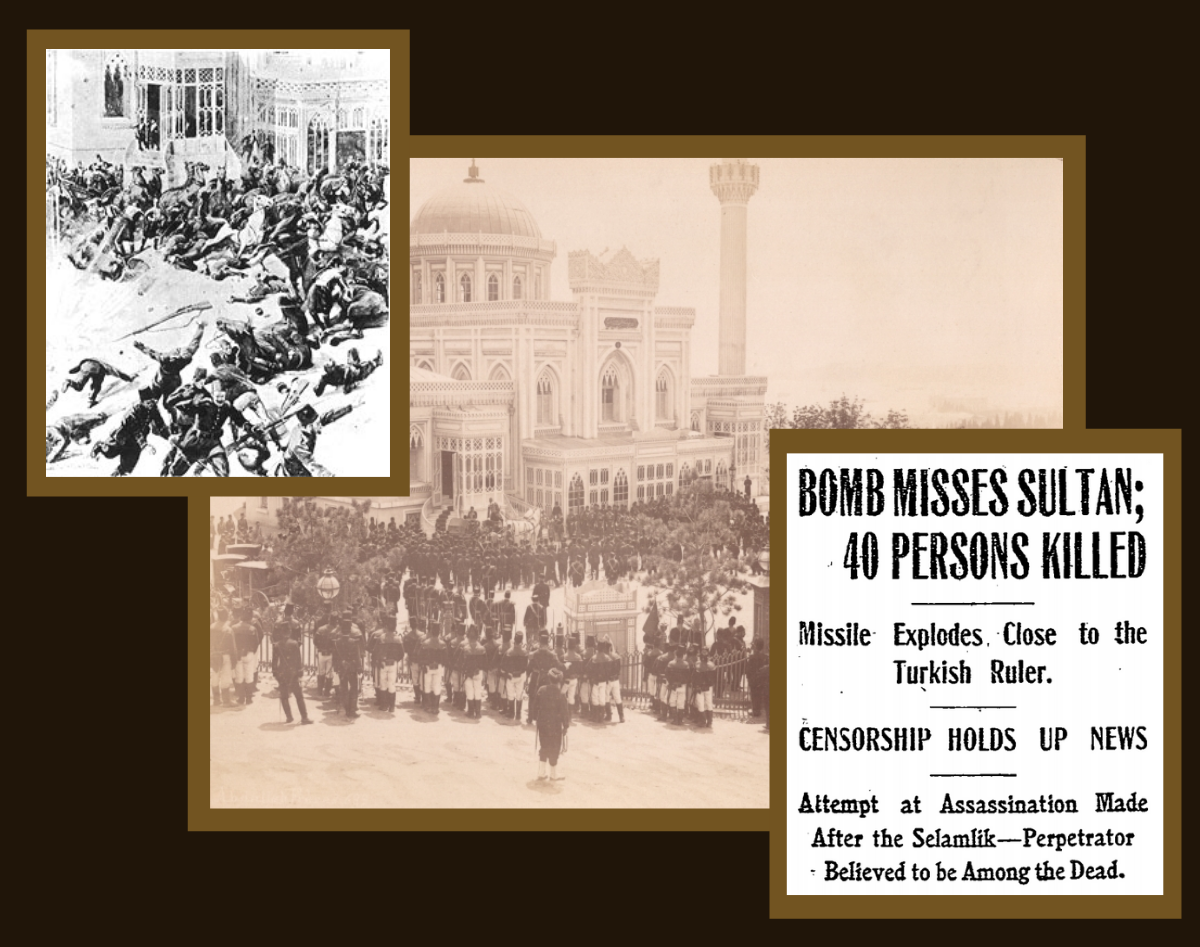

Mírzá Badí’u’lláh and Mírzá Muḥammad-'Alí, the faithless and cruel half-brothers of 'Abdu'l-Bahá had spent a lifetime undermining the Master, and, in the early 1900s, they began to send numerous, constant, malicious and baseless reports to Sulṭán ‘Abdu'l-Ḥamíd II about 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s activities alarming the Ottoman authorities and prompting the Ottoman government to dispatch appointed individuals to carry out extensive investigations of the reported claims.

In 1904, the first Commission of Inquiry arrived in 'Akká and interrogated 'Abdu'l-Bahá but accomplished little.

Mírzá Badí’u’lláh and Mírzá Muḥammad-'Alí began spreading malicious lies and rumors that 'Abdu'l-Bahá was raising an army, building a kingdom, and that the Shrine of the Báb was in fact a fortress.

In June and July 1905, a second commission of inquiry was sent to 'Akká and headed by a certain Ârif Bey, who was infuriated with 'Abdu'l-Bahá. Ârif Bey hated 'Abdu'l-Bahá so much that his goal was to secure an order from Sulṭán ‘Abdu'l-Ḥamíd II to hang the master from the gate of 'Akká.

Then, Ârif Bey’s plan changed, and he decided he would rather exile 'Abdu'l-Bahá to Fizan, in the middle of the Sahara desert, 2,400 kilometers (1,500 miles) away from 'Akká. Then, he decided he would rather throw 'Abdu'l-Bahá in the sea to drown.

It seems like Ârif Bey had a hard time making up his mind about how to put 'Abdu'l-Bahá to death.

During the investigation Mírzá Badí’u’lláh joined hands with 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s sworn enemies. The trumped-up charges against Him and the false reports culminated in the re-incarceration of 'Abdu'l-Bahá.

Photo montage illustrating the events around Sulṭán ‘Abdu'l-Ḥamíd II's attempted assassination on July 21, 1905.

Top left: Picture dramatizing the Yildiz attempt, not an actual photograph. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Center: A photograph of the type of event (not the exact event) the Sulṭán was attending, at Yıldız Hamidiye mosque during an Ottoman state ceremony in the late 19th century. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Bottom right: The New York Times headline for July 22, 1905 reporting the attempted assassination of the Sulṭán. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

'Abdu'l-Bahá was interrogated by the commission alone for several consecutive days to answer all their questions, including questions regarding the American pilgrims in 1898.

On a Friday in July 1905, members of the Commission of Inquiry inspected the Shrine of the Báb and were impressed by its size and solidity and asked one of the attendants how many vaults lay under the massive structure.

Shortly after the inspection, one day at sunset, the boat of the commission, which had been anchored off the coast of Haifa, weighed anchor and headed towards ‘Akká.

The news spread rapidly and everyone assumed the boat would stop long enough in 'Akká to take ‘Abdu’l‑Bahá on board, then head to Istanbul.

Bahíyyih Khánum and the Holy Family were anguished at the news, Bahá'ís who were present could not hold back their tears, weeping with grief at the idea of being separated from 'Abdu'l-Bahá.

At this most tragic of all hours, 'Abdu’l‑Bahá paced the courtyard of 'Abdu'lláh Páshá, alone and silent.

Dusk fell, and the commission's ship's swung around, charging its course to Istanbul and not 'Akká.

The members of the commission had been urgently summoned back by cable to Istanbul to investigate the conspiracy behind the attempted assassination of Sulṭán ‘Abdu'l-Ḥamíd II on 21 July 21 1905.

'Abdu’l Bahá, still pacing His courtyard as night approached, was immediately informed. Bahá'ís who had posted themselves at various places to watch the progress of the Ottoman ship also confirmed the joyful news.

One of the gravest dangers that had ever threatened ‘Abdu’l Bahá’s precious life had just been suddenly, providentially, and definitely averted.

The first bell had tolled signaling the imminent end of the Ottoman Empire in three years’ time.

Background photo by Frederik Löwer on Unsplash.

Bahíyyih Khánum played an important role in the middle of this storm of external opposition. The more intensely the storm of violation against the Covenant blew, the brighter her pure countenance shone.

The more 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s enemies attacked her adored Brother, the more obvious her rank and value appeared.

The more the Covenant-breakers attacked the Center of the Covenant, the calmer she appeared, always steadfast, always firm, never afraid, never despaired.

During this dangerous time, the Greatest Holy Leaf exercised sleepless vigilance, tact, courtesy, an unmovable patience, and a heroic strength of character.

Throughout it all, Shoghi Effendi unequivocally states that Bahíyyih Khánum was the partner of 'Abdu'l-Bahá in all His sorrows and tribulations.

For the entirety of His ministry, the one person 'Abdu'l-Bahá could always count on for support, strength, and encouragement was His saintly sister, the Greatest Holy Leaf.

It is fair to say that her outstanding qualities, her peerless character, and the strength of her mental composure would have been a tremendous comfort for 'Abdu'l-Bahá, and would have lessened not only His heavy burden but His anxiety.

During the critical and dangerous days of the Commissions of Inquiry, Bahíyyih Khánum was 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s staunch and trusted supporter. Her utter steadfastness and complete reliance on the Covenant made her a peerless companion to 'Abdu'l-Bahá.

Her entire being was suffused with utter conviction, total assurance, and deeply-rooted Faith.

Bahíyyih Khánum also played a pivotal role during this episode as she related to women of noble rank in the wider community of 'Akká.

Bahíyyih Khánum and 'Abdu'l-Bahá both took care of the wife off an Ottoman official who had always been friendly with them, and who had been arrested and sent to Damascus. They lent her assistance and gave her money.

In 1906, a Bahá'í pilgrim came to the Holy Land and heard 'Abdu'l-Bahá say He loved the Greatest Holy Leaf and His wife Munírih Khánum so much, and they served Him so faithfully, that He did not know what He would do without them.

There is perhaps no greater testament to the role of Bahíyyih Khánum in the ministry of 'Abdu'l-Bahá that this deeply-moving pilgrim note.

SOURCES FOR PART VI

Early 1896 – Shoghi Effendi’s parents wed in a simple ceremony

The Chosen Highway, Lady Blomfield, Bahá’í Publishing Trust, Wilmette, Ill. 1975, pages 112-113.

Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees, Baharieh Rouhani Ma’ani, George Ronald, Oxford, 2013, pages 26-60 and 114.

Ruhe, David. Door of Hope: The Bahá’í Faith in the Holy Land page 56 and Maani, Baharieh Rouhani. Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees: an in-depth study of the lives of women closely related to the Báb and Bahá’u’lláh pages 162-163 and 329-331.

Will and Testament of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá.

October 1896: The house of ‘Abdu’lláh Pashá

Ruhe, David. Door of Hope: The Bahá’í Faith in the Holy Land, page 56.

Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees, Baharieh Rouhani Ma’ani, George Ronald, Oxford, 2013, page 163.

1896: ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s prophetic dream

isiting ‘Abdu’l-Bahá: Volume 1: The West Discovers the Master, 1897-1911. Earl Redman, George Ronald Publishers, Oxford, 2019, Chapter 1897 – 1898 (year).

Lighting the Western Sky: The Hearst Pilgrimage and the Establishment of the Bahá’í Faith in the West, Kathryn Jewett Hogenson, George Ronald, 2012: Preface and acknowledgements

A prayer for the Greatest Holy Leaf

Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees, Baharieh Rouhani Ma’ani, George Ronald, Oxford, 2013, page 160.

The Greatest Holy Leaf and prominent people of ‘Akká

The Greatest Holy Leaf: A Reminiscence, ‘Alí Nakhjávání, published in The Bahá’í World, Volume 18 (1979-1983), pages 59-67.

The Greatest Holy Leaf’s extensive correspondence

The Greatest Holy Leaf: A Reminiscence, ‘Alí Nakhjávání, published in The Bahá’í World, Volume 18 (1979-1983), pages 59-67.

The Greatest Holy Leaf’s healing abilities

A Lifetime with ‘Abdu’l-Bahá Reminiscences of Khalíl Shahídí, Translated and Annotated by Ahang Rabbani, Witnesses to Bábí and Bahá’í History Volume 9, pages 46 and 75.

The Greatest Holy Leaf’s parrot

The Greatest Holy Leaf: A Reminiscence, ‘Alí Nakhjávání, published in The Bahá’í World, Volume 18 (1979-1983), pages 59-67.

A Lifetime with ‘Abdu’l-Bahá Reminiscences of Khalíl Shahídí, Translated and Annotated by Ahang Rabbani, Witnesses to Bábí and Bahá’í History Volume 9, page 62.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá and the Greatest Holy Leaf’s parrot

The Greatest Holy Leaf: A Reminiscence, ‘Alí Nakhjávání, published in The Bahá’í World, Volume 18 (1979-1983), pages 59-67.

A Lifetime with ‘Abdu’l-Bahá Reminiscences of Khalíl Shahídí, Translated and Annotated by Ahang Rabbani, Witnesses to Bábí and Bahá’í History Volume 9, page 62.

Memories of My Life: Translation of Mírzá Habíbu’lláh Afnán’s Khátirát-i-Hayát, Ahang Rabbani, page 331.

Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees, Baharieh Rouhani Ma’ani, George Ronald, Oxford, 2013, pages 164-165.

1 March 1897: Shoghi Effendi is born

The Priceless Pearl, Rúḥíyyih Rabbání, Bahá’í Publishing Trust, London, 1969, page 2.

Door of Hope. David S. Ruhe, George Ronald, Oxford, 1983, pages 56-58.

The Will and Testament of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá.

Shoghi Effendi: Child of prophecy

The Priceless Pearl, Rúḥíyyih Rabbání, Bahá’í Publishing Trust, London, 1969, page 2.

Door of Hope. David S. Ruhe, George Ronald, Oxford, 1983, pages 56-58.

The Will and Testament of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá.

Sometime after August 1897: He already has dreams!

The Priceless Pearl, Rúḥíyyih Rabbání, Bahá’í Publishing Trust, London, 1969, page 9.

1897: Bahíyyih Khánum’s letter about Covenant-breakers

Prophet’s Daughter: The Life and Legacy of Bahíyyih Khánum, Outstanding Heroine of the Bahá’í Faith, Janet A. Khan, Bahá’í Publishing Trust, Wilmette, 2005, page 46.

8 December 1898 – March 1899: The first 14 western Pilgrims

Earl Redman, Visiting ‘Abdu’l-Baha: Volume 1: The West Discovers the Master, 1897-1911 (p. 31). George Ronald. Kindle Edition.

Lighting the Western Sky: The Hearst Pilgrimage and the Establishment of the Bahá’í Faith in the West, Kathryn Jewett Hogenson, George Ronald, 2012.

Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees, Baharieh Rouhani Ma’ani, George Ronald, Oxford, 2013, pages 163-164.

The women pilgrims and Bahíyyih Khánum

Earl Redman, Visiting ‘Abdu’l-Baha: Volume 1: The West Discovers the Master, 1897-1911 (p. 31). George Ronald. Kindle Edition.

Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees, Baharieh Rouhani Ma’ani, George Ronald, Oxford, 2013, pages 163-164.

8 December 1898 – 20 February 1899: The significance and impact of the first western pilgrimage

Prophet’s Daughter: The Life and Legacy of Bahíyyih Khánum, Outstanding Heroine of the Bahá’í Faith, Janet A. Khan, Bahá’í Publishing Trust, Wilmette, 2005, pages 60-62 and 66.

Earl Redman, Visiting ‘Abdu’l-Baha: Volume 1: The West Discovers the Master, 1897-1911 (p. 31). George Ronald. Kindle Edition.

Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees, Baharieh Rouhani Ma’ani, George Ronald, Oxford, 2013, pages 163-164.

May Maxwell meets ‘Abdu’l-Bahá for the first time

Prophet’s Daughter: The Life and Legacy of Bahíyyih Khánum, Outstanding Heroine of the Bahá’í Faith, Janet A. Khan, Bahá’í Publishing Trust, Wilmette, 2005, pages 62-65.

May Maxwell’s memory of the Greatest Holy Leaf’s welcome

Prophet’s Daughter: The Life and Legacy of Bahíyyih Khánum, Outstanding Heroine of the Bahá’í Faith, Janet A. Khan, Bahá’í Publishing Trust, Wilmette, 2005, pages 62-65.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s “glorious sister”

Prophet’s Daughter: The Life and Legacy of Bahíyyih Khánum, Outstanding Heroine of the Bahá’í Faith, Janet A. Khan, Bahá’í Publishing Trust, Wilmette, 2005, pages 63-65.

The Bahá’í World, Volume 16, page 104.

A light which only grows brighter

Prophet’s Daughter: The Life and Legacy of Bahíyyih Khánum, Outstanding Heroine of the Bahá’í Faith, Janet A. Khan, Bahá’í Publishing Trust, Wilmette, 2005, pages 63-65.

March 1899: Ella Goodall witnesses the spiritual bond between ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and Shoghi Effendi

The Priceless Pearl, Rúḥíyyih Rabbání, Bahá’í Publishing Trust, London, 1969, pages 5-6.

Violetta Zein, The Extraordinary Life of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá Part IV: Center of the Covenant (1892 – 1910): 8 December 1898 – 20 February 1899 – The first western Pilgrims.

Bahíyyih Khánum’s beautiful blue eyes

Lighting the Western Sky: The Hearst Pilgrimage and the Establishment of the Bahá’í Faith in the West, Kathryn Jewett Hogenson, George Ronald, 2012, pages 108-109.

Wikipedia: Lua Getsinger.

“The simplicity of the truly great”

Lighting the Western Sky: The Hearst Pilgrimage and the Establishment of the Bahá’í Faith in the West, Kathryn Jewett Hogenson, George Ronald, 2012, pages 108-109.

Wikipedia: Lua Getsinger.

Viewing the portraits of Bahá’u’lláh and the Báb

Lighting the Western Sky: The Hearst Pilgrimage and the Establishment of the Bahá’í Faith in the West, Kathryn Jewett Hogenson, George Ronald, 2012, page 162.

Bahaipedia: Photograph of Bahá’u’lláh.

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, page 138.

Bijan Masumian and Adib Masumian, The Bab in the World of Images, Bahá’í Studies Review, vol. 19, June 2013, 171–90.

Prophet’s Daughter: The Life and Legacy of Bahíyyih Khánum, Outstanding Heroine of the Bahá’í Faith, Janet A. Khan, Bahá’í Publishing Trust, Wilmette, 2005, pages 62-65.

31 January 1899: At long last, the remains of the Báb arrive in the Holy Land

Journey to a Mountain: The Story of the Shrine of the Báb, Vol 1 1850-1921, Michael V. Day, George Ronald, 2017, pages 23-28.

1899 – 1900: The Greatest Holy Leaf protects and safeguards the remains of the Báb

Journey to a Mountain: The Story of the Shrine of the Báb, Vol 1 1850-1921, Michael V. Day, George Ronald, 2017, pages 39-44.

Spring 1899 – Early 1901: ‘Alí-Qulí Khán’s memories of Bahíyyih Khánum

Summon Up Remembrance, Marzieh Gail, George Ronald, Oxford, 1987, pages 109-110, 125, 128-131, and 138.

Bahaipedia: Ali-Kuli Khan.

The perfections of a truly great woman

Summon Up Remembrance, Marzieh Gail, George Ronald, Oxford, 1987, pages 109-110, 125, 128-131, and 138.

Bahaipedia: Ali-Kuli Khan.

30 October 1900: I love you very much

Visiting ‘Abdu’l-Bahá: Volume 1: The West Discovers the Master, 1897-1911. Earl Redman, George Ronald Publishers, Oxford, 2019, Kindle Edition location 1029-1049.

The lack of decent medical care in Haifa

Memories of Nine Years in ‘Akká, Dr. Youness Afroukhteh, Dr Riaz Masrour (trans), George Ronald, Oxford, 1952/2003, pages 406-408.

Shortly after 1900: Bahíyyih Khánum travels to Beirut for treatment

Memories of Nine Years in ‘Akká, Dr. Youness Afroukhteh, Dr Riaz Masrour (trans), George Ronald, Oxford, 1952/2003, pages 406-408.

1901: Bahíyyih Khánum’s letter about western pilgrims

Prophet’s Daughter: The Life and Legacy of Bahíyyih Khánum, Outstanding Heroine of the Bahá’í Faith, Janet A. Khan, Bahá’í Publishing Trust, Wilmette, 2005, pages 65-66.

1901 – 1907: The re-incarceration of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá

Prophet’s Daughter: The Life and Legacy of Bahíyyih Khánum, Outstanding Heroine of the Bahá’í Faith, Janet A. Khan, Bahá’í Publishing Trust, Wilmette, 2005, page

December 1902: The Countess de Canavarro interviews Bahíyyih Khánum

Wikipedia: Myron Henry Phelps.

The Life and Teachings of ‘Abbás Effendi, Myron Phelps, GP Putnams Sons, New York and London, 1904, page xxxv-xxxix.

Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees, Baharieh Rouhani Ma’ani, George Ronald, Oxford, 2013, page 164.

28 May 1903: The Greatest Holy Leaf and Lua Getsinger on the Ascension of Bahá’u’lláh

Lua Getsinger: Herald of the Covenant, Velda Metelmann, George Ronald, 1977.

1904 and 1905: The two commissions of inquiry

Dissent and Heterodoxy in the Late Ottoman Empire, Dr. Necati Alkan, pages 162-163.

Balyuzi, H.M. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá: The Centre of the Covenant, pages 118-122.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees, Baharieh Rouhani Ma’ani, George Ronald, Oxford, 2013, page 166.

Memories of Nine Years in ‘Akká, Dr. Youness Afroukhteh, Dr Riaz Masrour (trans), George Ronald, Oxford, 1952/2003, page 363.

After 21 July 1905: The end of the second commission of inquiry

Dissent and Heterodoxy in the Late Ottoman Empire, Dr. Necati Alkan, pages 162-163.

Balyuzi, H.M. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá: The Centre of the Covenant, pages 118-122.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees, Baharieh Rouhani Ma’ani, George Ronald, Oxford, 2013, page 166.

Memories of Nine Years in ‘Akká, Dr. Youness Afroukhteh, Dr Riaz Masrour (trans), George Ronald, Oxford, 1952/2003, page 363.

June – July 1905: Bahíyyih Khánum’s role during the Commission of Inquiry

Prophet’s Daughter: The Life and Legacy of Bahíyyih Khánum, Outstanding Heroine of the Bahá’í Faith, Janet A. Khan, Bahá’í Publishing Trust, Wilmette, 2005, pages 69 and 75.

Dissent and Heterodoxy in the Late Ottoman Empire, Dr. Necati Alkan, pages 162-163.

Balyuzi, H.M. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá: The Centre of the Covenant, pages 118-122.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees, Baharieh Rouhani Ma’ani, George Ronald, Oxford, 2013, page 166.

![]()

Early 1896 - Shoghi Effendi's parents wed in a simple ceremony

Early 1896 - Shoghi Effendi's parents wed in a simple ceremony