Written and illustrated by Violetta Zein

This part covers the life of Bahá’u’lláh from the age of 36 in 1853, to the age of 39 in 1856.

Bahá'u'lláh and the Holy Family's first journey in exile, lasting three months in the depths of winter and over a distance of 1000 kilometers (over 600 miles) from Ṭihrán to Baghdád. The thirty-two stops between the family's departure and arrival were plotted on Google Maps from Muḥammad Labib's 1968 Map of Stages in Baha'u'llah's Successive Exiles from Ṭihrán to 'Akká commemorating the centenary of Bahá'u'lláh's arrival in 'Akká, and approved by the National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá'ís of Italy. Correctly transliterated place names were obtained from Mike Thomas' 1991 Map of the Travels of Bahá'u'lláh, approved by the National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá'ís of the Hawaiian Islands. Many thanks to Adib Masumian for editing the transliterations of place names. © Violetta Zein.

In preparation for the long journey ahead, the government had provided nothing. Ásíyih Khánum sold almost all that remained of her marriage treasures, jewels, embroidered garments and other belongings for four hundred tumans, which enabled her to make provisions.

None of the Holy Family’s friends or relations came to their help or to say goodbye, except Ásíyih Khánum’s grandmother. They had been abandoned by their government and everyone else.

Accompanying Bahá'u'lláh were Ásíyih Khánum, in the early stages of her seventh pregnancy, ‘Abdu'l-Bahá and Bahíyyih Khánum, eight and six years old, and Bahá'u'lláh’s brothers, Mírzá Músá, and Mírzá Muḥammad-Qulí.

Mírzá Mihdí was about three years old, but he was too young and delicate for the arduous winter journey, which would have endangered his life, and Ásíyih Khánum was persuaded to leave her child behind in Ṭihrán in the care of her grandmother. Ásíyih Khánum suffered greatly from her separation with Mírzá Mihdí.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 102.

Baharieh Rouhani Ma'ani, Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees, pages 100-101.

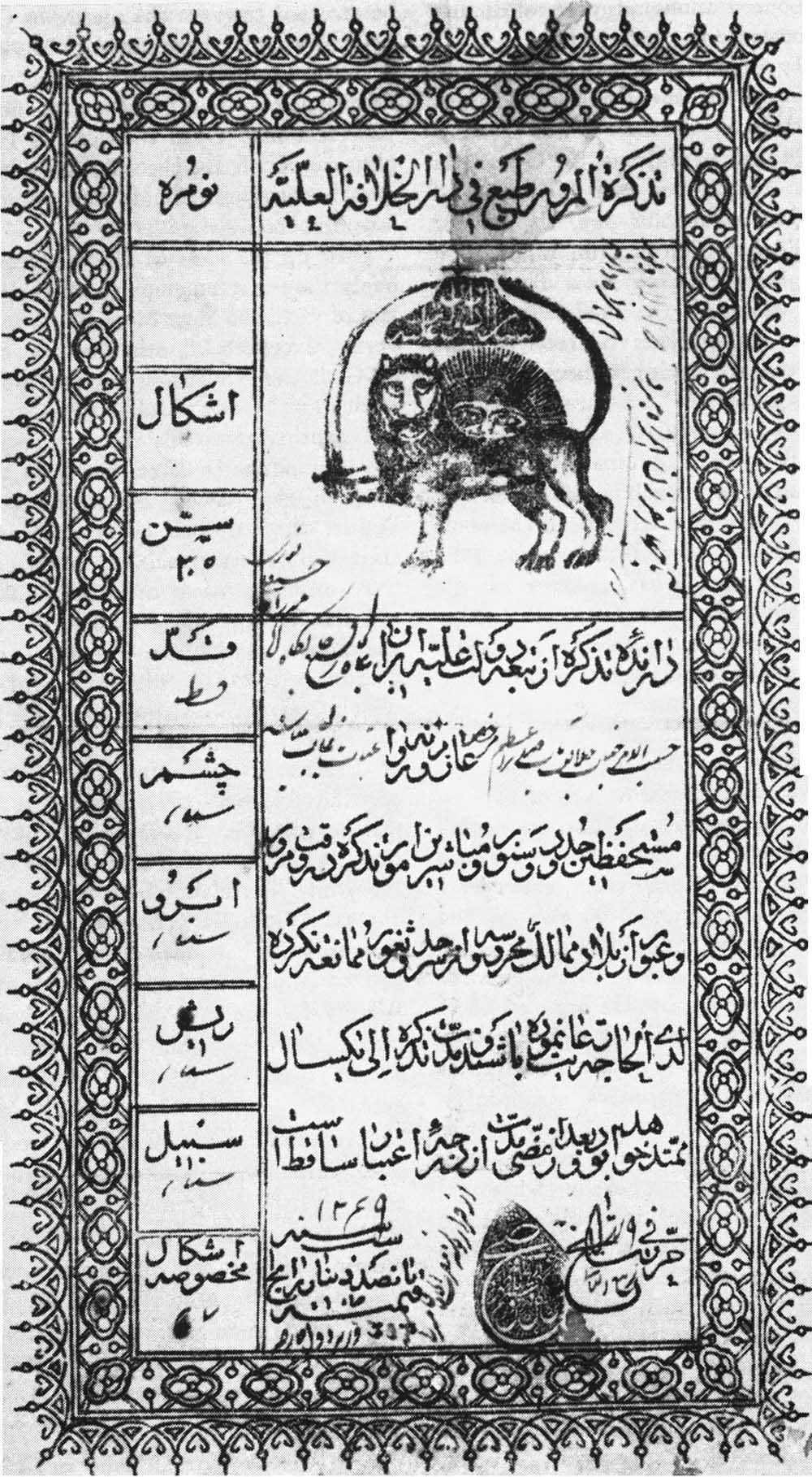

Bahá'u'lláh's passport, dated January 1853. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

On 12 January 1853, less than nine months after His return from Karbilá, Bahá'u'lláh began His return journey to Iráq, this time in exile from His native land forever and accompanied by His family.

They left accompanied by a representative of the Imperial Government of Persia, and an official from the Russian Legation, which Prince Dolgorukov had promised Bahá'u'lláh.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 102.

Baharieh Rouhani Ma'ani, Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees, pages 100-101.

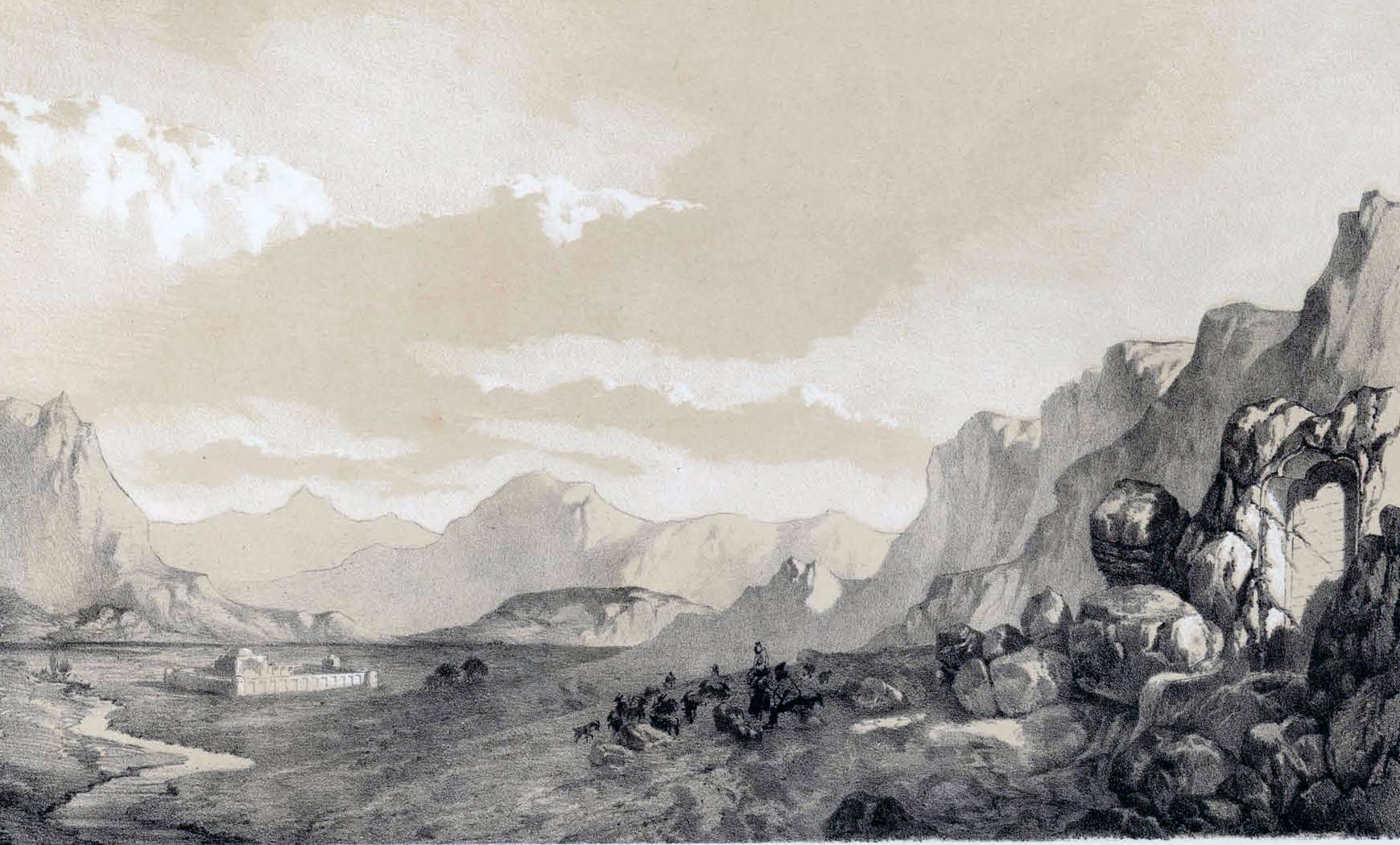

The Zagros Mountains between Iran and Iraq. © Livius.org | Jona Lendering. Used with permission.

The journey lasted three months. Bahá'u'lláh, in a prayer He revealed describing His ordeal in the Siyáh-Chál, speaks about the hardship of this winter voyage, when He was forced to leave Persia, “accompanied by a number of frail-bodied men and children of tender age, at this time when the cold is so intense that one cannot even speak, and ice and snow so abundant that is impossible to move.”

As testified by Bahá'u'lláh Himself, the journey to ‘Iráq was taxing and difficult. Bahá'u'lláh was still recovering from four months of imprisonment in the Siyáh-Chál which had been akin to torture, and the family traveled by horse and mule in the depth of winter, crossing the Zagros mountains passes that marked the border between western Persia and eastern ‘Iráq.

They traveled on frozen and snow-covered ground, shaken and jolted on mules during the day, and when night fell, they often had to camp in the icy wilderness, for which they were all sorely unprepared. None of them had any experience with hardship of this magnitude, and there were no servants to help, few provisions and very little money left. Along the way, Ásíyih Khánum would sell the jewel-encrusted buttons from her marriage chest for provisions.

Ásíyih Khánum never once complained. She always thought of something kind to do for someone, always thoughtful and full of sympathy for those around her. When they approached a city, Ásíyih Khánum would wash the laundry at the public baths, where everyone could also bathe. Then she would carry the nearly frozen wet clothes back to attempt to dry them. Her delicate hands, unused to such hard labor became very painful.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Prayer by Bahá'u'lláh quoted from Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Baharieh Rouhani Ma'ani, Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees, pages 100-101.

An 1840 engraving by Eugène Flandin of the caravanserai at Bísutún. We know Bahá'u'lláh stopped in Bísutún, but we have no references indicating that He stopped in this caravanserai. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The journey of the Holy Family from Ṭihrán to Baghdád lasted 86 days from 12 January to 8 April 1853. They stopped every night after having traveled all day, which means they either camped or stayed in a caravanserai overnight 85 times, no doubt pausing at times in caravanserais or rest areas during the day, adding to the number of stops.

We currently know of only 32 of these stops between Ṭihrán and Baghdád, but even that list, plotted on the map in the previous story, is heartbreaking to contemplate on, as we remember that Bahá'u'lláh was exhausted and recovering from His taxing imprisonment, Ásíyih Khánum was pregnant, and 'Abdu'l-Bahá and Bahíyyih Khánum, were only eight and six years old.

It is also painful to imagine all these stops when we know the Holy Family traveled so uncomfortably on pack animals, roughly jostling them over most of the 1,000 kilometers (over 600 miles) of steep mountainous terrain at elevations ranging between 1,000 and 2,000 meters (3,300 and 6,500 feet) until they reached Sorkhih-Dízih and their last eight stops to Baghdád, close to early spring 1853.

The Holy Family would either camp in the wilderness overnight or stay in caravanserais, travelers’ inns with accommodations for both people and pack animals, in which they were only allowed a single room. These rooms had no beds, and no light was allowed at night. The family sometimes managed to find tea, a few eggs, coarse bread and a little cheese.

Bahá'u'lláh was still so ill that He could not eat coarse food and He was growing weaker from not eating. This distressed Ásíyih Khánum greatly, who exerted herself to try and find food Bahá'u'lláh could eat. Once, Ásíyih Khánum had managed to find a little flour, attempted to make a cake for Bahá'u'lláh. But baking in the dark, she had used salt instead of sugar and the cake was inedible.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Lady Blomfield, The Chosen Highway, pages 45-47.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 104-105.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 1: Baghdád 1853 - 1863, pages 13-16 and page 51.

An 1840 engraving by Eugène Flandin of the mountains region of Kirmánsháh, a place named Tagh-i-Bustán. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Shaken by the news of the Báb’s martyrdom on 9 July 1850, Mírzá Yaḥyá, His 19-year-old nominee and Bahá'u'lláh’s half-brother, had lived in hiding, scared for his life, for almost three years. He moved from place to place, adopting different names, avoiding Bábís, for almost three years, moving farther west until he arrived in Kirmánsháh. There, he took a job as a shroud vendor to blend in more discreetly, when Bahá'u'lláh came through the city on His journey to Iráq.

Mírzá Yaḥyá overcame his fear and contacted Bahá'u'lláh, telling Him that he wanted to live near Him in Baghdád, but wanted to start a trade while living in his own house, but he needed some funds. Bahá'u'lláh gave Mírzá Yaḥyá a sum of money, with which Mírzá Yaḥyá purchased several bales of cotton, and, disguised as an Arab merchant, headed for Baghdád by way of Mandalíj.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 1: Baghdád 1853 - 1863, pages 53-54.

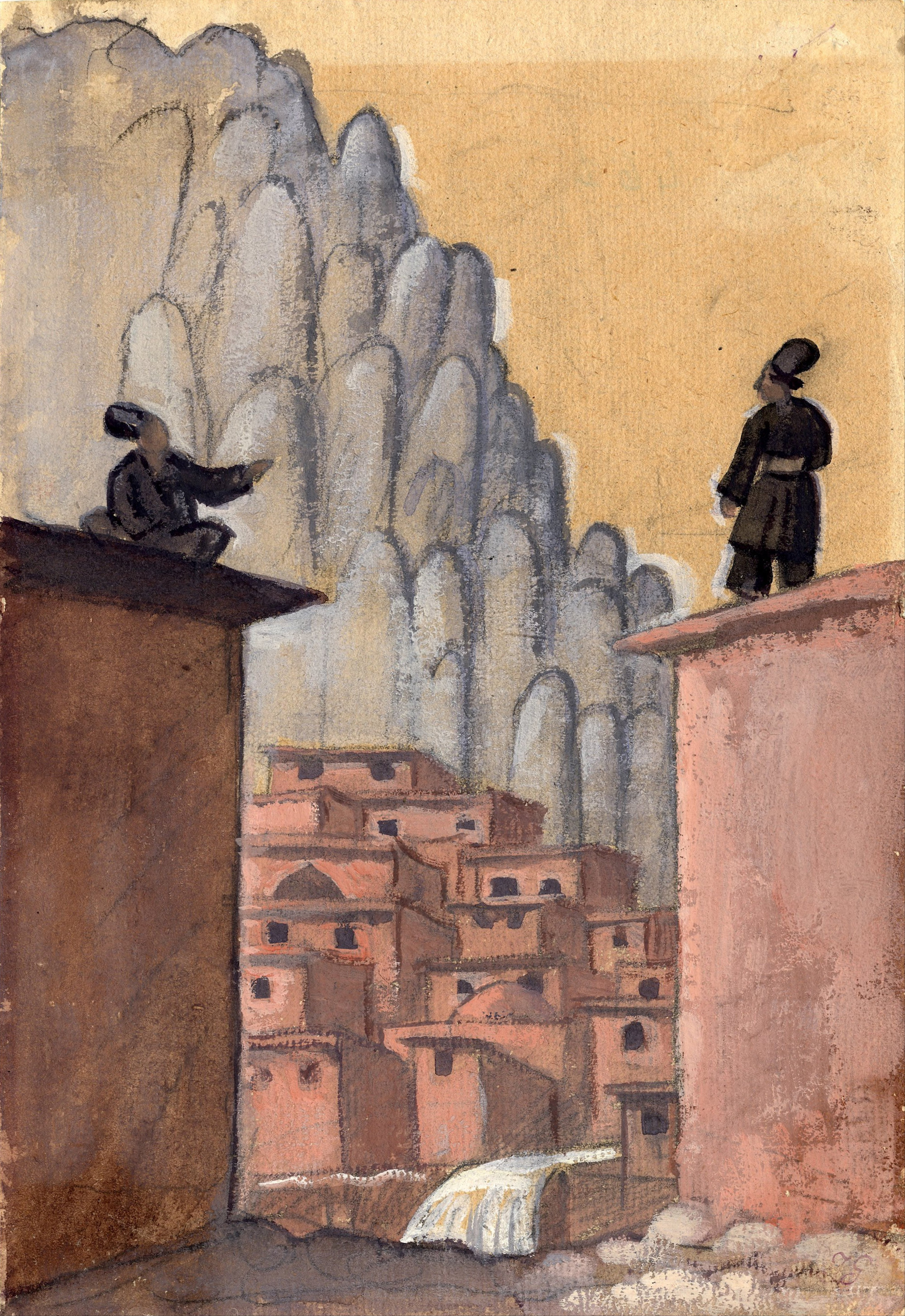

Bahá'u'lláh and His family were now entering a region populated by Kurds, who offered them a warm welcome. In homage to this stage of their journey in Karand, we offer a 1916 painting titled Kurds on the Roof, by Jāzeps Grosvalds, British first lieutenant of the British Expeditionary Group, painted as he crossed Karand. The stunning steep rocks painted by Grosvalds are an exact representation of the landscape of Karand. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

In Karand, the fifth stop before leaving Persia, Bahá'u'lláh and His family received a warm and enthusiastic reception on the part of the Governor, who was shown such kindness by Bahá'u'lláh that the entire village was affected. Long after Bahá'u'lláh’s departure, the people of Karand continued to extend warm hospitality to any of Bahá'u'lláh’s followers passing through their village, and the people of Karand would come to have a reputation for being Bábís.

When Bahá'u'lláh and His family arrived at the border of the Ottoman Empire, Ottoman soldiers took over from the Imperial soldiers and escorted the Family to Baghdád.

The frozen ordeal had lasted three months in the depths of an exceptionally severe winter, the air so cold at times they could not speak, and ice and snow so abundant, at times it was impossible to move.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 105.

First snow on a section of the Alborz Mountain range in Iran, from November 2010. Bahá'u'lláh and His Family would have been traveling two months after the first snowfall. Photograph by Mehdi Kalhor. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Around the time Bahá'u'lláh arrived in Karand, before crossing the border with ‘Iráq and leaving behind His homeland, He revealed a prayer on leaving Persia, from which we previously excerpted a line. This prayer, revealed in Persian and Arabic, is one of the very rare pieces of Bahá'u'lláh’s Revelation we have from Persia, a few months after receiving His Divine summons in the Siyáh-Chál.

Bahá'u'lláh acknowledges that God has destined for Him “trials and tribulations which no tongue can describe,” and recounts the past years during which “afflictions have, like showers of mercy, rained upon” Him, and describe in great detail His sufferings in the Siyáh-Chál, where the galling weight of the chains and fetters prevented Him from sleeping, how He was denied any peace or tranquility, deprived even of bread and water, how they inflicted upon Him “the things they refused to inflict upon such as have seceded from Thy Cause,” before, at last, banishing Him in the depths of a harsh winter, in the previously quoted excerpt.

Partial Inventory ID: BH00951

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 1: Baghdád 1853 - 1863, pages 51-52.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

1876 Wood engraving of "The thrones and palaces of Babylon and Nineveh" by John Philip Newman, page 105. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

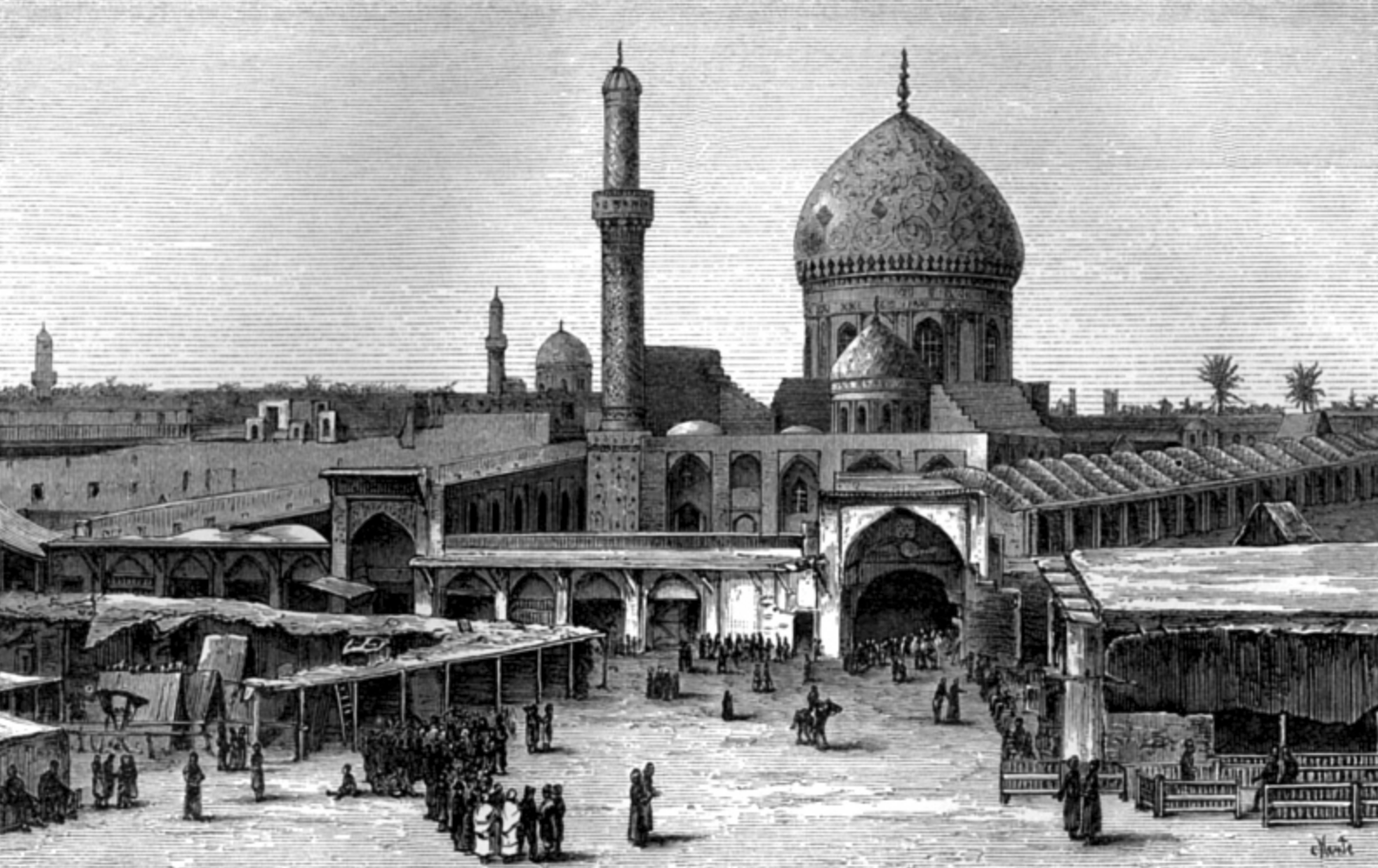

Bahá'u'lláh and His family arrived in Baghdád, the capital city of the Ottoman province of ‘Iráq on 8 April 1853. Throughout the history of religion, Manifestations of God had been forced to journey: Abraham’s banishment from ‘Iráq, the Exodus of Moses from Egypt, the Prophet Muḥammad's flight from Mecca to escape persecution, the Báb’s banishment and imprisonment in Ádhirbáyján, and Bahá'u'lláh’s first of four exiles, from Ṭihrán to Baghdád. Each time a Manifestation of God was banished, exiled, or forced to move across land, far-reaching spiritual victories arose from those journeys, consequences arose from that journey, and Bahá'u'lláh’s forty-year ministry and four exiles would manifest this spiritual truth time and time again.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Bahá'í Teachings: Abraham: Banished for Believing in God.

Wikipedia: Moses.

History: Muhammad completes Hegira.

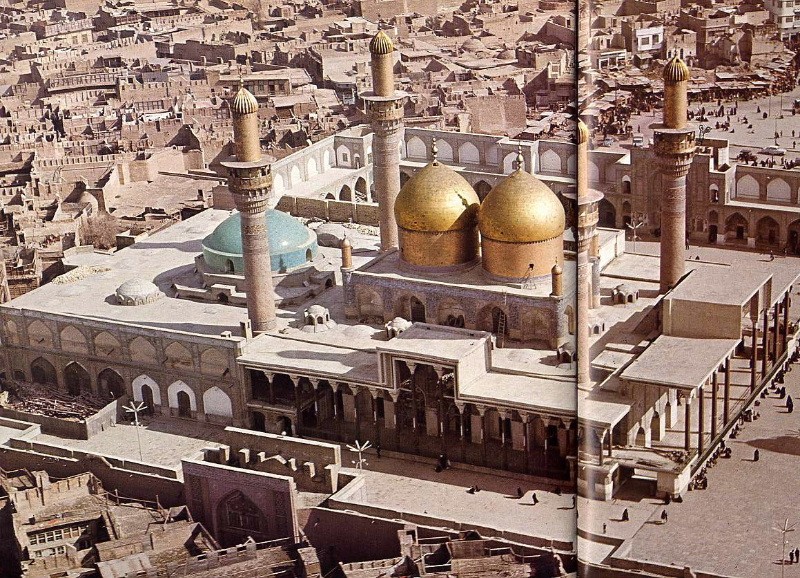

1920s Postcard by Royal Air Force Official, Baghdad, Al-Kadhimiya Mosque (Káẓimayn). Source: Wikimedia Commons.

A few days after arriving in Baghdád, Bahá'u'lláh left for Káẓimayn, about five kilometers (three miles) north of the city. Káẓimayn was the home of the Shrine of the Káẓims, the seventh and the ninth Imáms, populated mainly by Persians. Soon after His arrival, the Persian Consul-General called on Bahá'u'lláh and suggested He establish His residence in Old Baghdád rather than Káẓimayn, a center of pilgrimage with a fanatical Muslim population. Bahá'u'lláh consented, and a search began for a suitable house for Him and His family.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 106.

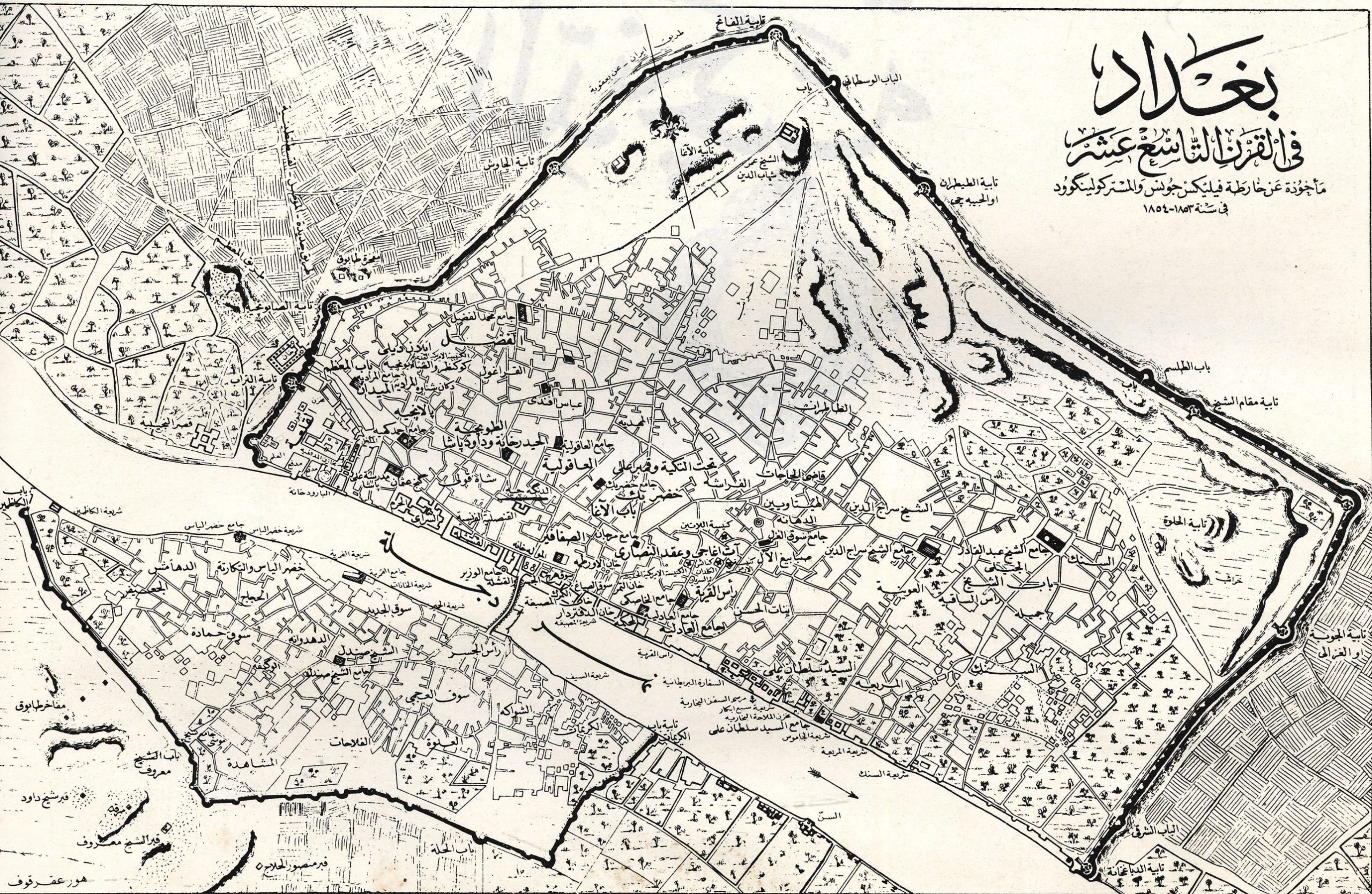

Old map of Bagdhád in Arabic showing the Tigris river. When Bahá'u'lláh and His family first arrived, they settled in Old Baghdád, in the northern part of the city. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

While Bahá'u'lláh had been in the Siyáh-Chál, all His homes had been plundered, and the family was virtually penniless. Early in their stay in Baghdád, they received proceeds from the sale of some of ‘Ásíyih Khánum’s wedding treasures in Persia, jewelry, cloth of gold and other valuable articles, and the money alleviated their situation considerably.

About a month after arriving in Baghdád, Bahá'u'lláh rented the small house of Ḥájí ‘Alí Madad, in an old quarter of the city, and moved with His family. During His ten-eyar exile in Baghdád, Bahá'u'lláh would occasionally visit nearby Káẓimayn, and the holy cities of Najaf and Karbilá about 60-50 kilometers (40-50 miles) from Baghdád.

At the time, Baghdád was a provincial center of the Ottoman Empire, with a population of around 60,000. When Bahá'u'lláh arrived, only a few bewildered Bábís remained in the city. They came to Him for advice, guidance and protection. The one who had been designed to fill this role was Mírzá Yaḥyá, the nominee of the Báb, but his three-year absence had deprived the Bábís of clear leadership.

Date from God Passes By as "A month later, towards the end of Rajab." The month of Rajab in 1269 A.H. ended on 9 May 1853, therefore it was before this date that Bahá'u'lláh settled in Old Baghdád.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 106.

Baharieh Rouhani Ma'ani, Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees, page 133.

EXTINGUISHED © Violetta Zein.

Between 1850 and 1853, the Bábí Faith had almost disappeared. The Báb was martyred in July 1850, the Bábí community was widely massacred in 1849 – 1850, and further decimated in the summer of 1852, as retribution for the attempt on the life of the Sháh. During this time, the one who had been designated to provide leadership, Mírzá Yaḥyá had disappeared for three years, and Bahá'u'lláh, the fountain of guidance and unity for the community was first imprisoned, then exiled. The Bábís were leaderless.

Traveling through Persia, Nabíl surveyed the condition of the Bábí Faith and stated that “The fire of the Cause of God had been well-nigh quenched in every place. I could detect no trace of warmth anywhere.” In some places, the Bábí community was split into as many as four factions, but the situation was worse in ‘Iráq, a smaller, distant, and isolated Bábí community.

The Bábí Faith had lost its prestige. The numbers of the Bábí community had dwindled, and the morals and character of the remaining Bábís had sharply declined. Such was their “waywardness and folly,” according to Bahá’u’lláh, that His first decision upon being released from the Siyáh-Chál was “to arise … and undertake, with the utmost vigor, the task of regenerating this people.”

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By Excerpt 1 and God Passes By Excerpt 2.

ANTICHRIST © Violetta Zein.

Forced to abandon his theological studies in Iṣfahán, Siyyid Muḥammad-i-Iṣfahání had emigrated, filled with shame and remorse, to Karbilá, where he became a Bábí. Immediately after the Báb’s martyrdom, Siyyid Muḥammad began showing signs of a shallow faith and weak convictions, and began to take advantage of the deteriorating situation in the Bábí community.

During His stay in ‘Iráq in 1851 – 1852, Bahá'u'lláh was showered with reverence, love, and admiration on the part of the most distinguished Bábís of the city, and Siyyid Muḥammad developed an insane jealousy towards Him, only made worse by Bahá'u'lláh’s patience and kindness towards him.

Siyyid Muḥammad was an inordinately ambitious, uncontrollably jealous and blindly stubborn man, a master manipulator who pulled Mírzá Yaḥyá’s strings and led him astray, and he would become infamous as the Antichrist of the Bahá'í Revelation. Bahá'u'lláh described him as the “source of envy and the quintessence of mischief.”

With Siyyid Muḥammad plotting mischief in Karbilá, promising Mírzá Yaḥyá, his lever in Baghdád, unchallenged leadership of the Bábí community, the two men began sowing dissension in the Bábí community that had gathered around Bahá'u'lláh.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By Excerpt 1 and God Passes By Excerpt 2.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 1: Baghdád 1853 - 1863, pages 53-54.

COWARDICE © Violetta Zein.

Two months after Bahá'u'lláh’s arrival, the 19-year-old Mírzá Yaḥyá established himself in the street of the Charcoal Dealers, in a run-down quarter of Baghdád, and donned a turban, adopted the name Ḥájí ‘Alíy-i-Lás-Furúsh, and went about his trade. Mírzá Yaḥyá was still in a state of panic, at being discovered as the “leader” of the Bábí community that he threatened to excommunicate any Bábí who recognized or greeted him in the bazaars of the city.

Mírzá Yaḥyá was a cowardly and gullible young man, but had been chosen by the Báb as His nominee as a symbolic figurehead leader of the community because he was closely related to Bahá'u'lláh and because his nomination would, for some years, divert attention from “Him Whom God shall make manifest,” whom the Báb had heralded, and His true successor, Bahá'u'lláh. It was nonetheless Bahá'u'lláh, whose unobtrusive hand, had led and directed the affairs of the Bábí community after the martyrdom of the Báb, while Mírzá Yaḥyá was in hiding.

Upon his arrival in Baghdád, Bahá'u'lláh had instructed Mírzá Yaḥyá to return to Persia with Mírzá Músá. Neither of them was bound by the decree of exile, and Bahá'u'lláh Himself would never be able to return to the Bábí Persian community. Mírzá Yaḥyá never left.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 1: Baghdád 1853 - 1863, pages 54-55.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 107-108.

DISCORD © Violetta Zein.

After the series of devastating persecutions heaped on the Bábí community since 1849 by its external enemies, Mírzá Yaḥyá and Siyyid Muḥammad would unleash a more devious devastation from the inside.

When Mírzá Yaḥyá resurfaced in Baghdád in 1853, his three-year absence had eroded his position and elevated Bahá'u'lláh’s, and, in parallel, the character of the leaderless Bábís in Baghdád had declined while their confusion had deepened. The situation was primed for Siyyid Muḥammad and Mírzá Yaḥyá to exploit with an unhinged audacity.

Mírzá Yaḥyá began claiming he was not just the nominee but the successor of the Báb, and brandished his titles of Mir’átu’l-Azalíyyih (Everlasting Mirror), Ṣubḥ-i-Azal (Morning of Eternity), and Ismu’l-Azal (Name of Eternity).

Siyyid Muḥammad encouraged him from Karbilá, and exalted Mírzá Yaḥyá to the rank of the first among the “Witnesses” of the Bayán. The two men’s actions endangered the prestige of the Bábí Faith into question and threatened its future.

Bahá’u’lláh, who could not yet share the secret of His Divine Revelation in the Siyáh-Chál, nonetheless had words of warning for the Bábís: “The days of tests are now come. Oceans of dissension and tribulation are surging, and the Banners of Doubt are, in every nook and corner, occupied in stirring up mischief and in leading men to perdition.…”

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Bahá'u'lláh, quoted by Shoghi Effendi in God Passes By.

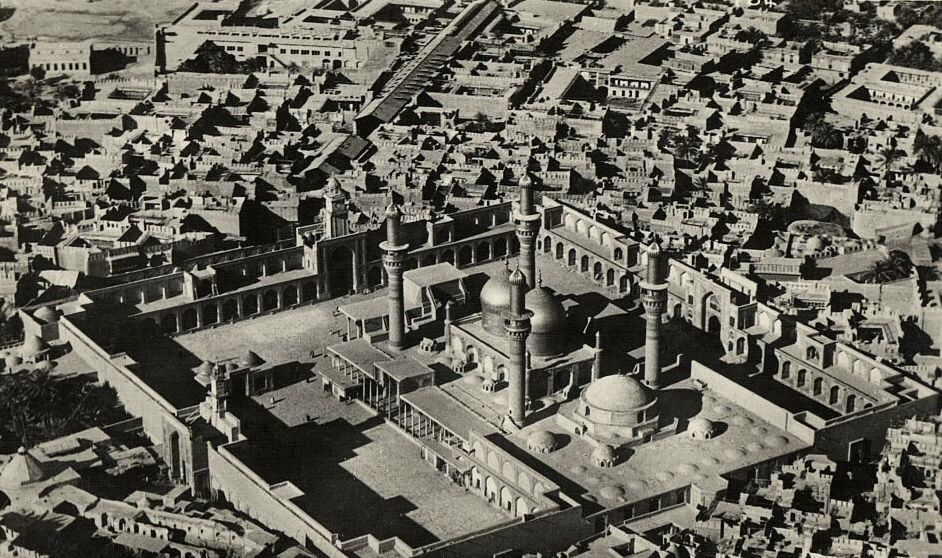

1920-1934 aerial photograph of the Old City of Baghdád, taken by the American Colony of Jerusalem. Source: Library of Congress.

The house of Ḥájí ‘Alí Madad, had two rooms, one for Bahá'u'lláh and one for Ásíyih Khánum and the children, which served as the reception room for Bábís visiting Bahá'u'lláh, and Arab ladies taught by Ṭáhirih, who came to call on Navváb.

One day, seven-year-old Bahíyyih Khánum had been asked to prepare the tea, and she had just carried the very heavy samovár upstairs. An Iráqí woman who was visiting exclaimed: "One proof that the Bábí teaching is wonderful is that a very little girl served the samovár!" Bahá'u'lláh, amused, turned to His only daughter with an instant and witty retort: "Here is the lady converted by seeing your service at the samovár!"

'Ásíyih Khánum, dainty, refined, gentle, was in delicate health, her strength diminished by the hardships of the journey, and close to the end of her pregnancy. She exerted herself constantly and without complaint, and Bahá'u'lláh Himself helped her with cooking. A few months after their arrival in Iráq, Bahá'u'lláh and Ásíyih Khánum’s fourth child was born, a baby boy they named 'Ali-Muḥammad.

Over time, the faithful Arab and Persian Bábís began to recognize that Bahá'u'lláh embodied the hopes of the Bábí community, but a crisis was about to unfold, as Mírzá Yaḥyá had arrived in Baghdád sometime around June 1863.

Baharieh Rouhani Ma'ani, Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees, pages 101-103.

Lady Blomfield, The Chosen Highway, page 47.

1919 photograph showing a flat adobe stone roof in Karbilá, as in the story in the vignette below. © Aikaterini Laskaridis Foundation, used with permission.

Mírzá Áqá Ján was a sixteen-year-old Bábí with an elementary-level, who worked as a soap-maker and seller in Káshán. After dreaming of the Báb, and reading some of Bahá'u'lláh’s Writings, he abandoned his home and traveled to Iráq, where he met Bahá'u'lláh in Karbilá in September 1853.Bahá'u'lláh was staying with a man named Ḥájí Mírzá Ḥasan-i-Ḥakím-Báshí, and usually slept on the roof of the house, where it was cooler. One night when Bahá'u'lláh had gone to sleep, Mírzá Áqá Ján began saying his prayers when he saw Bahá'u'lláh walking towards him.

Bahá'u'lláh began to reveal verses, pacing back and forth on the roof, chanting in the moonlight, and Mírzá Áqá Ján witnessed spiritual worlds unfolding before him, later recalling “with every step He took and every word He uttered thousands of oceans of light surged before my face, and thousands of worlds of incomparable splendor were unveiled to my eyes, and thousands of suns blazed their light upon me!”

Each time Bahá'u'lláh approached Mírzá Áqá Ján, He would pause and say to him in a tone “so wondrous that no tongue can describe it:” “Hear Me, My son. By God, the True One! This Cause will assuredly be made manifest. Heed thou not the idle talk of the people of the Bayán, who pervert the meaning of every word.” Bahá'u'lláh paced, chanted, and continued to address Mírzá Áqá Ján with those words until the first lights of dawn streaked through the sky. The stunned teenager removed Bahá'u'lláh’s bedding to His room, prepared His tea and left.

Mírzá Áqá Ján had been transformed by what he had witnessed from Bahá'u'lláh, an unexpected and direct contact with the spirit of a newborn Revelation. Bahá'u'lláh called Mírzá Áqá Ján “the first to believe” in Him, and bestowed on him the title Khádimu’lláh (Servant of God), instructing him not to reveal what he had seen and knew to be the truth.Though he was not educated, Bahá'u'lláh took the Mírzá Áqá Ján as His amanuensis, companion, and attendant for the duration of His ministry, where the man would have a front-seat for forty years to the unfoldment of the Dispensation of Bahá'u'lláh.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Covenant of Bahá’u’lláh, Chapter 15.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 1: Baghdád 1853 - 1863, page 111.

A 2008 aerial photograph of the Al-Khadimiya mosque and its surroundings taken by Ligadier Truffaut. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

During Bahá'u'lláh's first year in ‘Iráq, He visited Káẓimayn again. During the course of this visit, as Mírzá Áqá Ján and a Bábí by the name of Áqá Muḥammad-Ḥasan-i-Iṣfahání were in the presence of Baha'u'llah, in the home of another believer, named Ḥájí 'Abdu'l-Majíd-i-Shírází. Bahá'u'lláh chose to disclose to the men in His company, an infinitesimal degree of the splendor of His Revelation.

He asked Ḥájí 'Abdu'l-Majíd whether he wished to hear the Badí' (Unique) language used by the inhabitants of one of the worlds of God, then began to chant in that spiritual language, which Mírzá Áqá Ján described as having a wonderful effect on the listener. One day, Bahá'u'lláh told Ḥájí 'Abdu'l-Majíd, "Ḥájí, you have heard the Badi' language, and witnessed God's supremacy over His worlds. Render thanks for this bounty and appreciate its worth."

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 113-114.

Between late 1853 and 10 April 1854 - REVELATION - The Lawḥ-i-Kullu'ṭ-Ṭa'ám (The Tablet of All Food)

A photograph of Lake Dukan in the district of Sulaymáníyyih, in ‘Iráqí Kurdistán, located only 23 kilometers (14 miles) from Sár-Galu, the mountain where Bahá'u'lláh would spend His first year in seclusion. There is no indication that Bahá'u'lláh visited Lake Dukan, but this image is offered as an homage to His stated desire to depart from the midst of Baghdád, and to illustrate the stunning natural beauty that would have warmed Bahá'u'lláh’s heart after the pain He endured at the hands of Mírzá Yaḥyá and Siyyid Muḥammad. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Ḥájí Mírzá Kamálu'd-Dín, a knowledgeable Bábí from Naráq, had traveled to Baghdád to meet the nominee of the Báb and asked Mírzá Yaḥyá for a commentary on verse 3:93 of the Qur’án which had been puzzling him, and which stated, in part, “All food was allowed to the children of Israel except what Israel made unlawful for itself”

Mírzá Yaḥyá’s woefully inadequate and superficial answer disappointed Ḥájí Mírzá Kamálu'd-Dín who turned to Bahá'u'lláh for enlightenment on this verse. In response, Bahá'u'lláh revealed a Tablet in Arabic called the Lawḥ-i-Kullu’ṭ-Ṭa’ám (Tablet of All Food), one of the first emanations of His Pen in ‘Iráq.

Upon receiving the Tablet, Ḥájí Mírzá Kamálu'd-Dín was filled with a new spirit, and illumined with a new light. He had found, through Bahá'u'lláh’s explanations, the source of all knowledge and had recognized Bahá'u'lláh’s station. Bahá'u'lláh encouraged him to share the Tablet with the friends in Naráq but never to disclose the truth of what he had learned about His station.

In the Lawḥ-i-Kullu’ṭ-Ṭa’ám, Bahá'u'lláh describes in heartbreaking detail the suffering He endured at the hands of His enemies in Baghdád : “Oceans of sadness have surged over Me, a drop of which no soul could bear to drink. Such is My grief that My soul hath well nigh departed from My body....”

This Tablet was revealed at a time when Bahá'u'lláh was already contemplating leaving for the wilderness of Kurdistán, as Bahá'u'lláh describes Himself as a "lowly, forsaken ant, that hath hid itself in its hole, and whose desire is to depart from your midst, and vanish from your sight."

Partial Inventory ID: BH00267

Approximate date from The Leiden List.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 1: Baghdád 1853 - 1863, pages 55-56.

Excerpts from the Lawḥ-i-Kullu'ṭ-Ṭa'ám from Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

JEALOUSY © Violetta Zein.

Bahá'u'lláh could not contain His majesty, His all-encompassing knowledge, His matchless utterance. In His first year in Baghdád, Bahá'u'lláh had effected profound transformation on a number of individuals, including Mírzá Áqá Ján, and His revelation of the Lawḥ-i-Kullu’ṭ-Ṭa'ám had astounded Ḥájí Mírzá Kamálu'd-Dín, and renewed His faith. His circle of admirers grew steadily in Baghdád, and included officials of the city and the Governor, as well as Siyyid Káẓim’s former companions, all of whom spontaneously offered Bahá'u'lláh sincere marks of respect.

By contrast, Mírzá Yahyá was in a more precarious position than ever before. Since coming out of hiding, he had undermined himself with his shallow knowledge, his cowardice, his constant disguises and new names, and unflattering reports on his character.

Siyyid Muḥammad exploited this cleft in reputation between Bahá'u'lláh and Mírzá Yaḥyá to craft a permanent breach between them. Thanks to his relentless and malevolent efforts, the more Bahá'u'lláh’s prestige grew and the more Mírzá Yaḥyá’s dwindled, the more Mírzá Yaḥyá’s pent-up resentment and envy threatened to break out in full force.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 1: Baghdád 1853 - 1863, pages 54-55.

ATTACKS © Violetta Zein.

By 1854, Mírzá Yaḥyá and Siyyid Muḥammad had built up a clandestine opposition in Baghdád which aimed at sabotaging Bahá'u'lláh’s efforts and frustrating His plans to revive the Bábí community of Baghdád.

Mírzá Yaḥyá and Siyyid Muḥammad made insinuations and planted seeds of doubts in the hearts of the Bábís who were attracted to Bahá'u'lláh. They hinted that Bahá'u'lláh was not the lawful leader of the community, that He overthrew laws proclaimed by the Báb, and that He wrecked the Bábí Faith. They indirectly criticized, challenged and misrepresented Bahá'u'lláh’s Writings and even set in motion plans to injure Him physically, but the plan fell apart.

Bahá'u'lláh had made every effort to remedy this worsening situation, to no avail. Day by day and hour by hour, as a result of Mírzá Yaḥyá and Siyyid Muḥammad's malicious plotting, Bahá'u'lláh was in a constant state of sorrow, attacked and assailed without respite, and His pain and suffering were extreme.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 1: Baghdád 1853 - 1863, pages 54-55.

WOE © Violetta Zein.

Bahá'u'lláh spoke at length about the sadness and sorrow that filled His soul in the days preceding His seclusion in Kurdistán, describing this period as “tribulation upon tribulation,” and “woes at their blackest,” and speaking about His “sighs and lamentations,” His “powerlessness, poverty and destitution,” His “injuries,” and His “abasement.”

Bahá'u'lláh testifies weeping to such a degree that He could no longer prayer: “So grievous hath been My weeping, that I have been prevented from making mention of Thee and singing Thy praises,” or weeping with such intensity “that every mother mourning for her child would be amazed, and would still her weeping and her grief.”

After the chains and fetters He was subjected to in the Siyáh-Chál, says Bahá'u'lláh, He was exiled to Baghdád, where “We were afflicted with the perfidy of Our friends…I have borne what no man, be he of the past or of the future, hath borne or will bear.”

After His seclusion in Kurdistán, Bahá'u'lláh would look back upon His first year in Baghdád, and its root cause: “In these days, such odors of jealousy are diffused, that … from the beginning of the foundation of the world … until the present day, such malice, envy and hate have in no wise appeared, nor will they ever be witnessed in the future.”

DIFFICULTIES © Violetta Zein.

Towards Bahá'u'lláh’s last days in Baghdád, He was so sad that the limbs of his body trembled. One night, shortly before His departure, Mírzá Áqá Ján saw Bahá'u'lláh suddenly come out of His home in the middle of the night, with His night-cap still on His head. Bahá'u'lláh was perturbed and angry, and spoke about Mírzá Yaḥyá and Siyyid Muḥammad, saying:

“These creatures are the same creatures who for three thousand years have worshipped idols, and bowed down before the Golden Calf. Now, too, they are fit for nothing better. What relation can there be between this people and Him Who is the Countenance of Glory? What ties can bind them to the One Who is the supreme embodiment of all that is lovable?”

In those days, Bahá'u'lláh recited the Báb’s invocation “Is there any Remover of difficulties save God?” five hundred, a thousand times, day and night, awake and sleeping, that His enemies might see the light. Before He left Baghdád, Bahá'u'lláh often made reference to His disappearance from their midst, but no one knew at the time what He was referring to.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 115.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

SEPARATION © Violetta Zein.

There came a point when Bahá'u'lláh could no longer stay in the toxic and divided atmosphere Mírzá Yaḥyá and Siyyid Muḥammad had crafted. The only purpose of His seclusion was to no longer be a source of disunity within the Bábí community, and to avoid hurting a single soul. His hope was that, with His absence, the fires of jealousy and hatred would die down, but at the time He left, He had no plans to ever return: “Our withdrawal contemplated no return, and Our separation hoped for no reunion.”

There was another aspect in Bahá'u'lláh’s decision to leave Baghdád, and that was to save Mírzá Yaḥyá from the constant embarrassment of being compared to His greatness. Bahá'u'lláh would give Mírzá Yaḥyá the chance he had always wanted to prove himself as the leader of the Bábí community. It would be a disaster.

Before leaving Baghdád, Bahá'u'lláh commanded the Bábís to treat Mírzá Yaḥyá with consideration and respect, offering His half-brother the hospitality of the Holy Family, and on the morning of 10 April 1854, Bahá'u'lláh vanished.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 1: Baghdád 1853 - 1863, page 55.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Bahá'u'lláh, The Kitáb-i-Íqán.

Baharieh Rouhani Ma'ani, Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees, page 133.

Lady Blomfield, The Chosen Highway, page 50.

Extremely approximate photographs for the places of seclusion of the Manifestations of God. In the center: Photograph of Sargalu mountain (seclusion of Bahá'u'lláh) near Sulaymaniyah, Iraq from Daban mountain by Rebaz Mohammed Nasih. Source: Wikimedia Commons. Top Left: Photograph of the Sinai Desert (Seclusion of Moses) by Vyacheslav Argenberg. Source: Wikimedia Commons. Bottom Left: Photograph of the Judean Hills (Seclusion of Jesus Christ) by David Shankbone. Source: Wikimedia Commons. Top Right: Photograph of Bhawal National Park (the forests of the Gangic plain were the place of seclusion of Buddha) by Azim Khan Ronnie. Source: Wikimedia Commons. Bottom Right: Photograph of the Arabian Desert (Seclusion of Prophet Muḥammad) by Aidas U. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Throughout the thousands of years of religious history, Manifestations of God sought seclusion, solitude, or distance from the rest of humanity, at some point in their ministry: Moses went out into the desert of Sinai, Buddha sought the wilds of India, Jesus Christ walked the wilderness of Judaea, the Prophet Muḥammad paced the sunbaked hills of Saudi Arabia, and Bahá'u'lláh sought the solitude of the mountains in ‘Iráqí Kurdistán.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 114.

The kashkúl (alms bowl) Bahá’u’lláh used as He traveled through the mountains of Sulaymaniyyih as a dervish from 1854 to 1856. © Bahá'í International Community. Source: The Life of Bahá'u'lláh: A Photographic Narrative Website. Photo Credit: Ted Cardell, 1952.

On the morning of 10 April 1854, ‘Ásíyih Khánum and the children, the rest of Bahá'u'lláh’s relatives and companions woke up to find He had vanished, one year and two days after arriving in Baghdád.

Bahá'u'lláh was accompanied by a Muslim attendant named Abu’l-Qásim-i-Hamadání, and He gave Abu’l-Qásim some money and instructed him to act as a merchant. While on Sar-Galú, Baha'u'llah would come down from the caves into the town of Sulaymáníyyih in order to acquire food and supplies, and at first, Aqa Abu'l-Qasim also came to visit Him and bring Him provisions. At some point early on in Bahá'u'lláh's seclusion, Abu’l-Qásim had to leave Him and travel across the nearby border into Persia to obtain money and provisions. When he was returning, at the border between Persia and Iráq, he was attacked and killed either by highwaymen or frontier patrols.

Just before he died, Abu’l-Qásim was able to say his name, that he was originally from Hamadan, and that what he carried had been the property of Darvísh Muḥammad-i-Irání, who lived in the uplands of Kurdish Iráq. His last words would make it into a news item that would find its way to Baghdád and to the eyes of 'Abdu'l-Bahá and Mírzá Músá. After the death of Abu’l-Qásim, Bahá'u'lláh was left completely alone through the vast region of Iráqí Kurdistán, 260 kilometers (160 miles) from Baghdád.

Date range from Bijan Ma'sumián, Bahá'u'lláh's Seclusion in Kurdistán, Published in Deepen Magazine, Volume I, Number I, Fall 1993, page 22.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Nabíl, The Dawn-Breakers, page 585.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 1: Baghdád 1853 - 1863, page xx.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 116-118.

The mountain of Sar-Galú where Bahá’u’lláh stayed in Sulaymáníyyih between 1854 and 1856, circa 1940. © Bahá'í International Community. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank.

Bahá’u’lláh retired to the wilderness. Bahá'u'lláh spent the first year of His retirement, from April 1854 to sometime in 1855, living on a mountain called Sar-Galú, which was so remote that it was a three-day walk to the closest town and so isolated that it was only visited twice a year by the villagers of the area, at planting and harvest times. During His time on Sar-Galú, Bahá'u'lláh was completely isolated. He was a three-day walk from the closest inhabited house. During this time, He survived mostly on rice and milk, which He most probably obtained by occasionally making the journey to a nearby town, Sulaymáníyyih, about 40 kilometers (25 miles) away, where He would also take the opportunity to visit a public bath.

The people of Kurdistán had their own culture and language. They were Sunní, sturdy and belligerent, and though they shared a border with Persia, they had a centuries-old hostility to their Shí’ah neighbors, whom they considered traitors to Islám. Bahá'u'lláh was crudely dressed as a dervish, and owned nothing but a change of clothes and His alms-bowl (kashkúl). For two years, the Kurds knew Bahá'u'lláh only as Darvísh Muḥammad.

On Sar-Galú, Bahá'u'lláh lived in solitude, completely undisturbed, at times living in a caves in the mountain or in a crude stone structure, which the rare peasants who came to the mountain used during inclement weather. The wild country Bahá'u'lláh roamed was but a physical manifestation of the spiritual wilderness He found Himself in as He would later tell His beloved cousin Maryam: “I roamed the wilderness of resignation, traveling in such wise that in My exile every eye wept sore over Me, and all created things shed tears of blood because of My anguish. The birds of the air were My companions and the beasts of the field My associates.”

The days in Kurdistán were filled with profound spiritual pain and anguish but also physical suffering. Bahá'u'lláh often went hungry, as He testifies in the Kitáb-i-Íqán: “there rained tears of anguish, and in My bleeding heart surged an ocean of agonizing pain. Many a night I had no food for sustenance, and many a day My body found no rest… Alone I communed with My spirit, oblivious of the world and all that is therein.” Bahá'u'lláh lived deprived of even the most basic comforts for a full year until a certain Shaykh Ismá’íl had a dream of the Prophet Muḥammad, and this encounter would signal the second phase in Bahá'u'lláh's retirement to Kurdistán.

Date range from Bijan Ma'sumián, Bahá'u'lláh's Seclusion in Kurdistán, Published in Deepen Magazine, Volume I, Number I, Fall 1993, page 22.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Nabíl, The Dawn-Breakers, page 585.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 1: Baghdád 1853 - 1863, page xx.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 117.

A very special panel, making a link between the twin Manifestations of the Bahá'í Revelation on the theme of childhood calligraphy exercises. To illustrate the story below about Bahá'u'lláh helping a young student with his calligraphy exercises, we offer the childhood calligraphy exercises of The Báb before He was ten, in the 1820s. Source: Wikimedia Commons, this facsimile was originally published in Hand of the Cause Mr. Balyuzi's biography: The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, facing page 48.

While Bahá'u'lláh was still living isolated on Sar-Galú, above Sulaymáníyyih, He came upon a Ṣúfí seminary student who was sitting by the road and weeping bitterly. Bahá'u'lláh asked the young man why he was so sad, and the boy explained: "Today, our schoolmaster gave all the other boys a copy to practise their writing, but me he dismissed and I have no copy." Bahá'u'lláh reassured the boy, and told him: "If you will bring your paper and pen, I shall set a copy for you."

When the boy returned to his school and showed everyone Bahá'u'lláh's exquisite calligraphy, everyone was astonished, and the news spread through Sulaymáníyyih. Bahá'u'lláh's extraordinary penmanship aroused admiration and curiosity in everyone who saw it.

Nabíl, The Dawn-Breakers Part II (Bahá'u'lláh) quoted in 'Alí -Akbar Furútan, Memories of Bahá'u'lláh, page 19.

Artistic re-interpretation of the cave of Bahá'u'lláh on Sar-Galu photographed by a Kurdish artist. Inspiration: Bahá'í Views website: On Bahá'u'lláh in Kurdistan: A Kurdish Artist Visits His Cave. © Violetta Zein.

From 1854 to 1855, Bahá'u'lláh spent the complete solitude of His seclusion on Sar-Galú in a deep spiritual state of devotion, prayer, and meditation. He revealed prayers and soliloquies in poem and prose forms, and chanted them aloud to Himself at dawn and during His night watches. Bahá'u'lláh’s Revelation from that period is lost to us forever, with only the barren mountain and birds of the air as its witnesses. Shoghi Effendi has provided us with the themes Bahá'u'lláh expounded upon during this mystical period of His ministry, themes He would return to in Tablets and Writings He revealed upon His return to Baghdád.

In Sar-Galú, the Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh glorified the names and attributes of God, and the glories and mysteries of His Revelation, extolling to the Maid of Heaven who had appeared to Him in the Siyáh-Chál. He recalled the tragedy, pain and suffering of the Prophets, Chosen Ones and Manifestations of God, from Moses, Jesus, the Imám Ḥusayn and the Prophet Muḥammad, preparing Himself for the trials He was to endure in the same path, and expounding on His current loneliness and His past and future trials.

Bahá'u'lláh lamented the blindness of this generation, the treachery of His friends and perversity of His enemies, vowing His determination to arise and offer up His life for the Cause, and expounded on the essential qualities and attributes of every sincere seeker for Truth, a theme He would revisit in the Hidden Words and the Seven Valleys.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Map showing distances between the two places where Bahá'u'lláh lived in Kurdistán and Baghdád. The background of Iraq is made from the image of Sar-Galú held by the Bahá'í International Community. © Violetta Zein.

Bahá'u'lláh was on Sar-Galú, living a completely solitary life, when Shaykh Ismá‘íl of Sulaymáníyyih had a dream of the Prophet Muḥammad, directing him to seek out Bahá'u'lláh and bring Him food. Shaykh Ismá‘íl lived in Sulaymáníyyih and owned property around Sar-Galú. In Sulaymáníyyih, he was the leader of the Khálidíyyih Order, a branch of the Ṣúfí Naqsh-bandíyyih order of Sunní Islám. Shaykh Ismá‘íl visited Bahá'u'lláh several times, repeatedly requesting Him to come and live in Sulaymáníyyih, until Bahá'u'lláh finally consented, ending the first sequestered phase of His seclusion in Kurdistán, and ushering the second phase, a progressive return to society.

In the time of Bahá'u'lláh, Sulaymáníyyih was a barren town of about 500 small, dilapidated houses, and its inhabitants were poor, nomadic Kurds. Built on the base of a barren mountain range rising above it, Sulaymáníyyih was battered by constant hot winds in the summer months. When He first established residency in Sulaymáníyyih, Bahá'u'lláh was so reserved and silent, the inhabitants had no reason to consider Him other than the traveling Persian dervish He claimed He was, lodged in the local takyih, the Ṣúfí theological seminary.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 117.

Wikipedia: Naqshbandi.

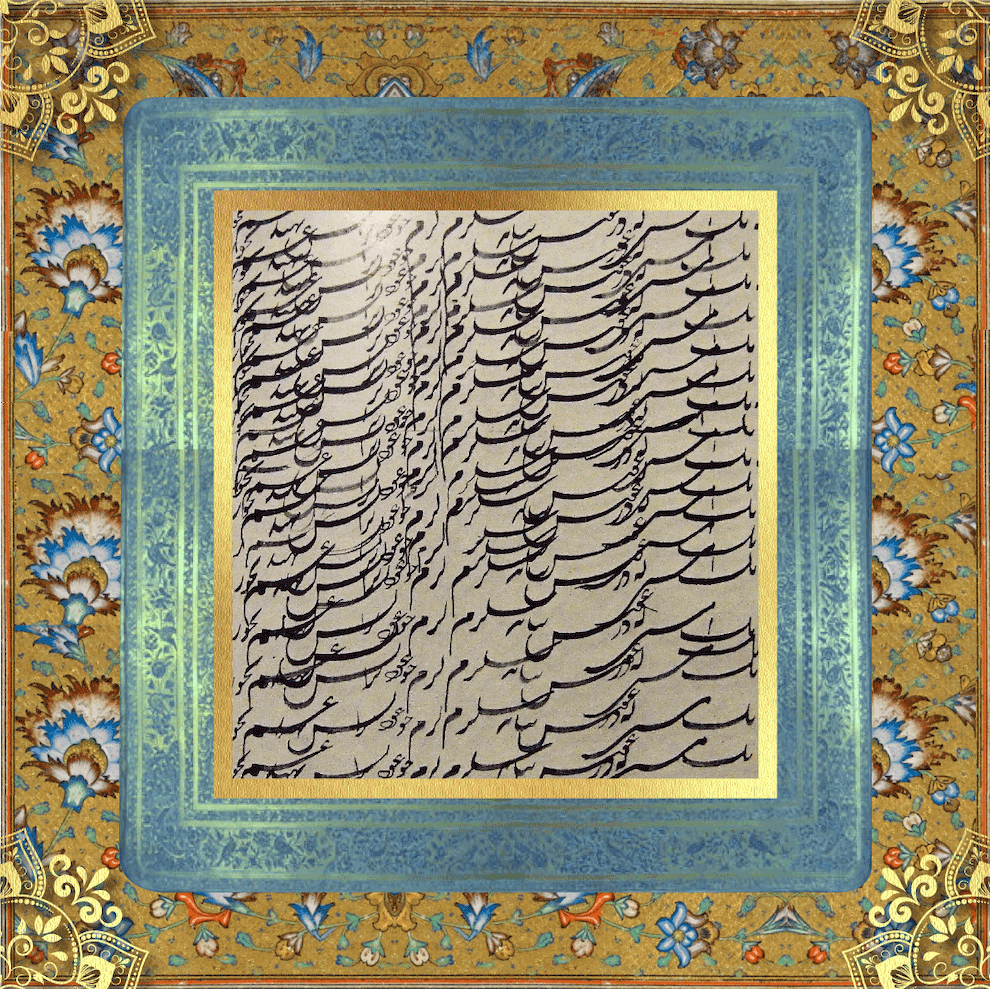

Illuminated Tablet in the beautiful and elegant calligraphy of Bahá'u'lláh, which prompted the Ṣúfí scholars to seek Him out. © Bahá'í International Community. Source: Bahai Media.

In Sulaymáníyyih, Bahá'u'lláh lived in the takyih of Mawláná Khálid, a renowned Ṣúfí theological seminary home to illustrious Sunní theologists. The takyih had been associated with the descendants of Saladin, the first Sulṭán of Egypt and Syria, for eight centuries, and possessed vast endowments. Soon after Bahá'u'lláh’s arrival in Sulaymáníyyih, a delegation of the most brilliant and distinguished doctors and students of the seminary, led by Shaykh Ismá‘íl, came to visit Bahá'u'lláh, intrigued by another piece of calligraphy He had penned. They found Bahá'u'lláh perfectly willing to answer any of their questions, and, over several interviews, they asked Him to expound on obscure passages of the 37-volume Futúḥát-i-Makkíyyih also known as the Meccan Revelations, the celebrated work of Ibnu’l-‘Arabí.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 117.

The takyih (Ṣúfí theological seminary) where Bahá'u'lláh stayed in while living in Sulaymáníyyih. Source: Bahai Biblio.

Unfamiliar with the Futúḥát-i-Makkíyyih, Bahá'u'lláh told them: “God is My witness that I have never seen the book you refer to. I regard, however, through the power of God, … whatever you wish me to do as easy of accomplishment.” Each day, page of Futúḥát-i-Makkíyyih was read aloud to Bahá'u'lláh, after which He would answer their questions. The assembled scholars were astounded. Bahá'u'lláh did not simply clarify obscure mystical passages, but would interpret Ibnu’l-‘Arabí’s mind, expound on his doctrine and explain his intent. At times, Bahá'u'lláh would question the validity of some of Ibnu’l-‘Arabí’s arguments, reframing them with proofs that completely convinced His learned audience.

The scholars were so spellbound, amazed at the depth of Bahá'u'lláh’s insight and the breadth of His understanding, that they asked Him to do something no one had done before.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 117.

Wikipedia: Al-Futuhat al-Makkiyya.

Wikipedia: Ibn Arabi.

Ibnu’l-‘Arabí was also known as Shaykh Muḥyi’d-Dín-i-‘Arabí, he was a 12th century Arab Andalusian Muslim scholar, prolific mystic, poet, and philosopher whose full name was Muhyíal-Dín Abú ʿAbd’Allāh Muḥammad ibn ʿAlí ibn Muḥammad ibn al-ʿArabí al-Ḥátimí al-Ṭáʾí al-Andalusí al-Mursí al-Dimashqí.

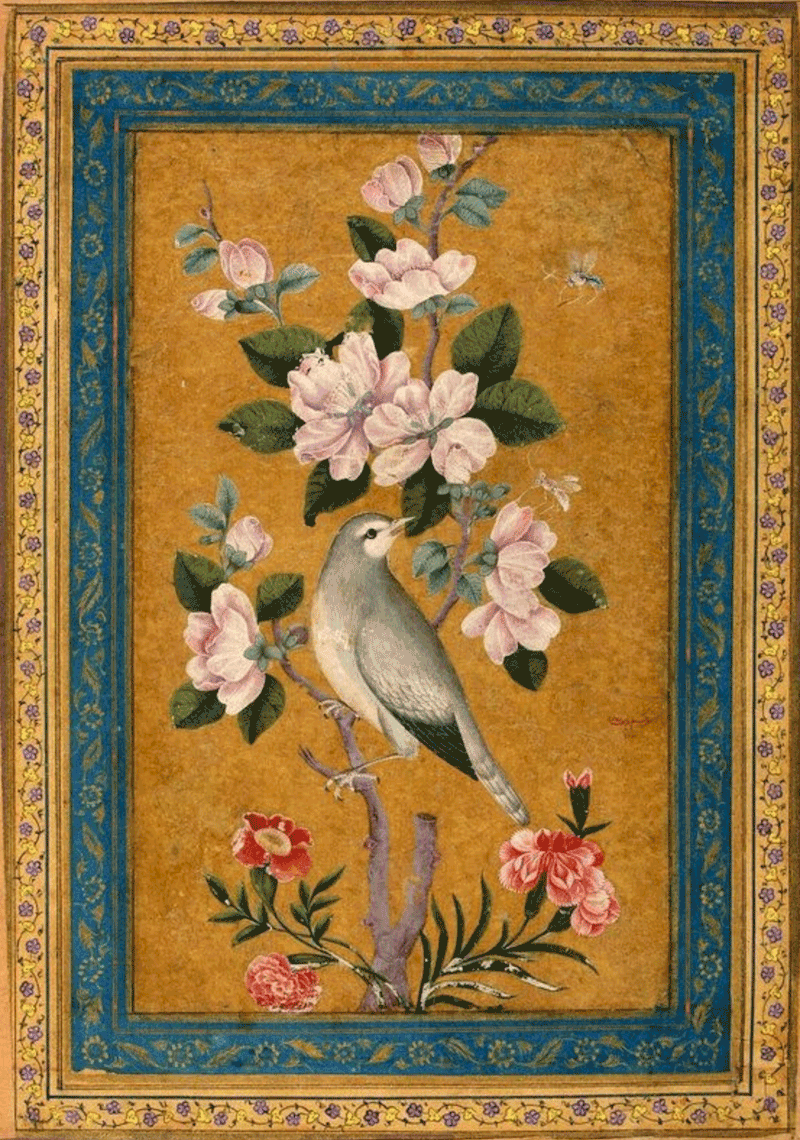

Bird perching on a flowering branch by Yusuf Zaman, originally from the State Hermitage in St. Petersburg. Source: Medium.

What the scholars in Sulaymáníyyih requested from Bahá'u'lláh was for Him to compose an entirely new poem in the same rhythm and meter as Ibn-i-Fáriḍ’s 12th century masterpiece, Qaṣídiy-i-Tá’íyyih, unanimously considered for seven centuries to be the greatest achievement in Arabic literature. Ibn-i-Fáriḍ’s triumph was a 760-verse poem in Arabic in the Ṭawíl meter, side by side couplets rhyming in “ti,” ten times the length of any other poem of the same style. Qaṣídiy-i-Tá’íyyih was an entirely new form of literature, part poem, part treatise, and all at once lyrical, dramatic, narrative, and didactic.

The learned doctors and students of Sulaymáníyyih begged Bahá'u'lláh to do the impossible: “No one among the mystics, the wise, and the learned has hitherto proved himself capable of writing a poem in a rhyme and meter identical with that of the longer of the two odes, entitled Qaṣídiy-i-Tá’íyyih composed by Ibn-i-Fáriḍ. We beg you to write for us a poem in that same meter and rhyme.” Bahá'u'lláh exceeded their expectations.

He dictated the Qaṣídiy-i-Varqá’íyyih (The Ode of the Dove), a 2,000-verse poem, nearly three times the length of Ibn-i-Fáriḍ’s work, entirely in Arabic and in identical rhyme and meter. In the end, Bahá'u'lláh only allowed them to keep 127 verses, estimating the mystical subject matter was too premature. These verses were, and continue to be, widely circulated among Arabic-speakers.

The Qaṣídiy-i-Varqá’íyyih, like the Rashḥ-i-‘Amá, praises the Maid of Heaven (Hourí Ilahí), the embodiment of the Holy Spirit. personifying the Great Spirit of God, and the Primal Will of God. The only part of the Qaṣídiy-i-Varqá’íyyih that is authoritatively translated is from Shoghi Effendi in God Passes By and speaks to Bahá'u'lláhs tests and difficulties: “Noah’s flood is but the measure of the tears I have shed, and Abraham’s fire an ebullition of My soul. Jacob’s grief is but a reflection of My sorrows, and Job’s afflictions a fraction of my calamity.”

Not only did Bahá'u'lláh reveal a poem three times longer than the original, but He rewrote grammar rules, embedded multiple mystical and theological allusions within each couplet, and imbued the poem with a messianic theme, to which He would add footnotes (see references) upon His return to Baghdád.

Partial Inventory ID: BH00115

Excerpt from Bahá'u'lláh’s Qaṣídiy-i-Tá’íyyih in Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Bahá'u'lláh's "Ode of the Dove": A Provisional Translation by John S. Hatcher, Amrollah Hemmat, and Ehsanollah Hemmat published in Journal of Bahá'í Studies, 29:3, pages 43-66 Ottawa: Association for Bahá'í Studies North America, 2019

Ode of the Dove by Bahá'u'lláh provisionally translated by Juan Cole 1997, which includes Bahá'u'lláh's own notes to this Tablet.

Foad Seddigh, The Ode of the Nightingale (Qáṣídíy-i-Varqá'íyyih): Its Significance and Similarities with Tá'íyyih Ibn-i-Fárid, presented at the Irfán Colloquia Session #128 (October 9 - 12, 204)

Britannica: Ibn al-Fāriḍ.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 1: Baghdád 1853 - 1863, pages 63-64.

Bijan Ma'sumián, Bahá'u'lláh's Seclusion in Kurdistán, Published in Deepen Magazine, Volume I, Number I, Fall 1993, pages 24-25.

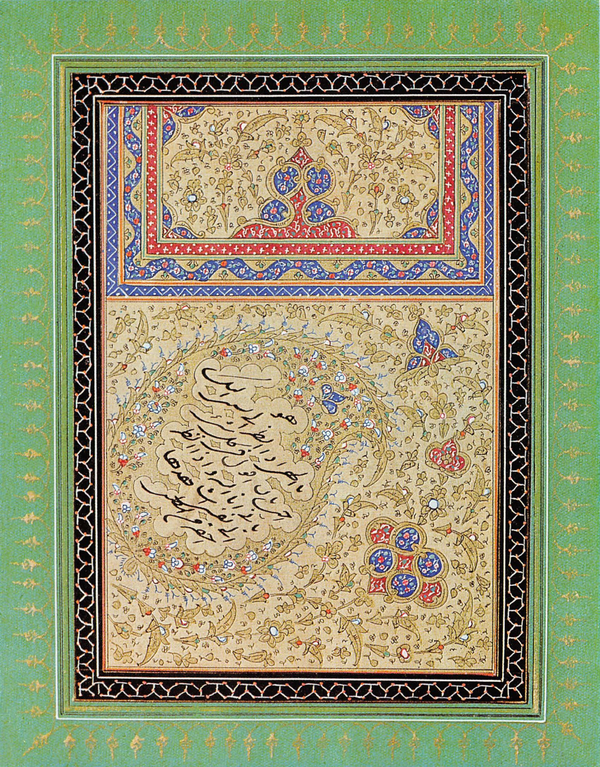

This is the prayer Bahá'u'lláh revealed in Kurdistán and brought back down the mountains to Baghdád with Him, which so affected twelve-year old 'Abdu'l-Bahá. This is a "hacked" illumination. The illuminated part of the prayer is from a 17th century Mughal (Indian) Ṣúfí painting (to keep with the Ṣúfí theme of this entire section), but the prayer and the parchment-like background were digitally-altered to match the original painting. Source of the background illumination: Jahangir Preferring a Ṣúfí Shaykh to Kings, from the St. Petersburg album (Wikimedia Commons). © Violetta Zein.

Among the Writings Bahá'u'lláh's revealed during His two-year seclusion in Kurdistán is the deeply cherished prayer "Create in me a pure heart." When He returned to Baghdád, and was reunited with His family, this was one of the prayers He brought with Him, and 'Abdu'l-Bahá, wept openly when He read it for the first time.

Another work dating to Bahá'u'lláh’s time in Kurdistán is the mystical poem Sáqí-Az-Ghayb-i-Baqá (The Cup-bearer from the Eternal Unseen), a soul-stirring ode expressing Bahá'u'lláh’s longing for the day He can at last unveil His glory to the world.

Baz-Av-i-Bidih Jámí (At Dawn the Friend Came to My Bed) is a brief poem which Bahá'u'lláh revealed in mixed Arabic and Persian, on the theme of the divine love, immortal life, and Bahá'u'lláh's longing to offer up His life in the path of God.

CREATE IN ME A PURE HEART

Partial Inventory ID: BH04421

‘Alí-Akbar Furútan, Stories of Bahá’u’lláh, page 20.

SÁQÍ-AZ-GHAYB-I-BAQÁ

Partial Inventory ID: BH03843

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 1: Baghdád 1853 - 1863, page 64.

BAZ-AV-I-BIDIH JÁMÍ

Partial Inventory ID: BH05338

From Steven Phelps, Chapter 5: The Writings of Bahá'u'lláh, in Routledge World: The World of the Bahá'í Faith, First Edition, Edited By Robert H. Stockman.

Modern view of the countryside outside Sulaymáníyyih. Photographer: Adam Jones. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Bahá'u'lláh’ live Revelation of the extraordinary Qaṣídiy-i-Varqá’íyyih was an astonishing event. After this feat, His fame spread far and wide in the region, and Bahá'u'lláh piqued the interest of all the learned Muslims in the area. ‘Ulamás, , shaykhs, and princes who were in Sulaymáníyyih and Kárkúk for seminaries, followed Bahá'u'lláh’s activities. He soon became the focal point for those hungry for true knowledge and enlightenment. Bahá'u'lláh appeared among them day after day, answering their many questions on obscure and confusing aspects of theology with clarity and eloquence.

Soon, the people of Kurdistán were magnetized by His love. Shortly after arriving in Sulaymáníyyih, Bahá'u'lláh had won over the hearts of important and powerful men, and those of the three regional Ṣúfí leaders. Shaykh ‘Uthmán was the leader of the Naqshbandíyyih Ṣúfí order, to which belonged the Ottoman Sulṭán; Shaykh ‘Abdu’r-Raḥmán was the leader of the Qádiríyyih Ṣúfí order numbering no less than 100,000 faithful followers. It was in response to his questions that Bahá'u'lláh would later reveal The Four Valleys; and Shaykh Ismá‘íl, who had sought out Bahá'u'lláh on Sar-Galú, led the Khálidíyyih Ṣúfí order.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 1: Baghdád 1853 - 1863, page 62.

This photograph of sheep grazing in a valley in Kurdistán is almost exactly halfway between Sar-Galú and Sulaymáníyyih, the mountain where Bahá'u'lláh began His self-imposed exile, and the small town where He ended His seclusion of two years. The geographical coordinates can be found on the Wikimedia page. To see the locations of the other two locations, type "Sargallu" and "Sulaymaniyah" Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The Ṣúfí seminary where Bahá'u'lláh resided in Sulaymáníyyih was part of the mosque of Mawláná Khálid. At the time Bahá'u'lláh was in Sulaymáníyyih, Mawláná Khálid was an old man, deeply-revered by the Kurds. He asked Darvísh Muḥammad (Bahá'u'lláh) to draw up a document that would safeguard the endowment of the mosque’s custodianship to his descendants. Bahá'u'lláh drew up other such documents for the inhabitants of Sulaymáníyyih during His time there, and these documents were still the property of families of Sulaymáníyyih some forty years ago when Hand of the Cause H.M. Balyuzi wrote Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory. At the time Hand of the Cause Ḥusayn Balyuzi visited Sulaymáníyyih, the documents prepared by Bahá'u'lláh were considered priceless by their owners. One man stated he would refuse to part from his document for a million pounds, certain that divine bounties would be cut off from his family should he sell the relic.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 118-119.

This is a very distant visual homage to the activities Bahá'u'lláh was engaged in while living in Sulaymáníyyih. This 16th century painting done in Shíráz represents the great Ṣúfí master Shaykh Safi al-Din interpreting for his disciples various verses by distinguished poets. This is one of the 14 paintings in the 16th century Safvat al-Safa (The Quintessence of Purity), the biography of Shaykh Safi Al-Din Ishaq Ardabili who lived in the 13th/14th centuries. Source: Aga Khan Museum.

During the remainder of His time in Sulaymáníyyih, Bahá'u'lláh gave discourses, opened new worlds to His reverent listeners with the many epistles He revealed, resolved the questions that puzzled their minds, unfolded the inner meanings of obscure passages written by poets, commentators and theologians, reconciling opposing statements in dissertations or treatises. Bahá'u'lláh conquered many hearts of many of those He met. Kurds, Arabs, and Persians, learned and illiterate, high and low, young and old, all those met Him felt reverence and a profound affection towards Bahá'u'lláh.

Bahá'u'lláh grew so much in their estimation, that the people of Sulaymáníyyih began speculating on His station, perhaps knowing, in a spiritual sense, that he was not a mere man like them. To some, Bahá'u'lláh was one of the Rijálu'l-Ghayb (Men of the Unseen), a Ṣúfí belief based on hadiths stating some people walk among humans with knowledge of the worlds of God. To others, Bahá'u'lláh was a master of alchemy and divination, others still called Him “a pivot of the universe,” and some were convinced He was a prophet of God. Out of respect, the Kurds addressed Bahá'u'lláh as ‘Íshán (They), and more highly revered than Káká Aḥmad, a Ṣúfí saint of past ages.

Perhaps the most telling sign of the Kurds’ esteem for Bahá'u'lláh was their acceptance of statements He made about His station, which, coming from another man would have provoked anger or cost him his life. In writing to His beloved cousin Maryam, Bahá'u'lláh called this chapter of His life, His seclusion in the wilderness of Kurdistán, “the mightiest testimony” to, and “the most perfect and conclusive evidence” of the truth of His Revelation.

'Abdu'l-Bahá speaking about the spiritual power in this same period of Bahá'u'lláh’s life would say “In a short time, Kurdistán was magnetized with His love. During this period Bahá’u’lláh lived in poverty. His garments were those of the poor and needy. His food was that of the indigent and lowly. An atmosphere of majesty haloed Him as the sun at midday. Everywhere He was greatly revered and loved.”

According to Shoghi Effendi, Kurdistán was the place where Bahá'u'lláh, the Supreme Manifestation of God had laid the foundations of His future greatness. After His departure, Sar-Galú, where Bahá'u'lláh had spent the first year of His seclusion, was held to be a sacred and holy place for the people of Sulaymáníyyih.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 118-119.

A 1950-1977 photograph of Baghdád from the Haidar Khana mosque by Matson Photo Service. Source: Library of Congress.

By late 1855, the fame of Darvísh Muḥammad had spread to Baghdád, 300 kilometers (185 miles) to the south, reports of a deeply revered dervish in Kurdistán who possessed innate greatness and superhuman knowledge. Around the same time, the murder of Bahá'u'lláh's servant, Abu’l-Qásim-i-Hamadání was reported in a Persian newspaper, about a year after it occured in 1854. While they were at the Persian Consulate, Mírzá Músá, and 'Abdu'l-Bahá read the article which reported Abu’l-Qásim's will mentioning Darvísh Muḥammad in Kurdistán. There was no longer any doubt in their minds, Ásíyih Khánum, Mírzá Músá, and 'Abdu'l-Bahá had finally found Bahá'u'lláh.

The situation in Baghdád had become catastrophic in Bahá'u'lláh's two-year absence, and His guidance, leadership, and presence were desperately needed. The Holy Family sent a profoundly devoted and trustworthy Arab Bábí, Shaykh Sulṭán, to Sulaymáníyyih with the mission of begging Bahá'u'lláh to return.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 121-22.

Momen, Moojan, Bahá'u'lláh, A Short Biography, page 41.

Story and reference graciously shared by Earl Redman from his historical research for The Apostles of Bahá’u’lláh and the Disciples of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, forthcoming at George Ronald.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 1: Baghdád 1853 - 1863, pages 67-68.

As we slowly arrive at the conclusion of Bahá'u'lláh's two-year retirement in the mountains of Kurdistán, it felt appropriate to pay a tribute to those Kurds who, with all their heart, so loved Bahá'u'lláh, a Persian and not a Sunní, despite their belligerent reputation for intolerance to outsiders. This is an exceptional photograph, almost contemporary, by less than twenty years, to the time Bahá'u'lláh lived among the Kurds. This 1873 portrait by the famous photographer Pascal Sebah on the occasion of the universal exposition in Vienna is part of a series showing the traditional costumes of the Ottoman Empire: On the right, a Kurd from Aljazeera in Mesopotamia; In the center, a Kurd from Mardín, a city on the Syrian border which Bahá'u'lláh would visit as He journeyed towards His second Exile; and on the left a shepherd from the province of Diyarbekir. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Shaykh Sulṭán-i-Karbilá’í, was descended from some of the most eminent ‘ulamás of Karbilá. He had been not only a loyal disciple but an intimate friend of Siyyid Kázim, had met the Báb in Shíráz and had been converted to the Bábí Faith by Ṭáhirih. Shaykh Sulṭán and his attendant Javád the Ḥaṭṭáb (Woodcutter) traveled from Baghdád to Kurdistán for two months before finding Bahá'u'lláh in Sulaymáníyyih. His mission was to convince Bahá'u'lláh to return to Baghdád, and to deliver letters and messages from believers, also begging Him to come back.

When Shaykh Sulṭán arrived in Sulaymáníyyih, Bahá'u'lláh was still living in the theological seminary and he found himself in a delicate situation. Bahá'u'lláh was so adored in Sulaymáníyyih that Shaykh Sulṭán feared the townspeople might murder him if the found out he was here to take their beloved Darvísh Muḥammad away. Shaykh Sulṭán proceed with great caution and wisdom, and did not speak openly about Bahá'u'lláh returning to Baghdád. Instead, he delivered the letters and petitions he had been entrusted with, all of which urgently beseeched Bahá'u'lláh to put an end to His seclusion, and some written by His own family, including 'Abdu'l-Bahá, devotedly attached to His Father.

Bahá'u'lláh's two-year absence had left an irreplaceable void in the leadership of the Bábí community, and even Mírzá Yaḥyá had written him a letter, begging Bahá'u'lláh insistently to return to Baghdád. After giving Bahá'u'lláh the letters, Shaykh Sulṭán returned to the caravanserai where he was staying and waited.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 121-122.

Nabíl, The Dawn-Breakers, page 189.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 1: Baghdád 1853 - 1863, pages 67-68.

Moojan Momen, Bahá’u’lláh: A Short Biography, page 41.

Reference to Moojan Momen graciously shared by Earl Redman from his historical research for The Apostles of Bahá’u’lláh and the Disciples of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, forthcoming at George Ronald.

A redrawn and traced 19th century engraving of Baghdád, heavily manipulated to show the interplay between the forces of good and evil of the city, which have been playing out throughout Bahá'u'lláh's stay in Kurdistán. When Bahá'u'lláh returns to Baghdád, He brings with Him the dawn of a new light, that will shine as resplendent as the noon-day sun in just a few years,in a verdant isle on the banks of the Tigris river. © Violetta Zein.

Bahá’u’lláh called on Shaykh Sulṭán at his caravanserai, initially unwilling to leave Sulaymáníyyih. Bahá'u'lláh pointed to the treachery and backbiting to which He had been subjected in Baghdád, contrasting it with the sincere devotion and high regard with which He was held among the Kurds in Sulaymáníyyih. Shaykh Sulṭán and Javád said that if Bahá'u'lláh was staying in Sulaymáníyyih, they would also settle in town, and before long, many other Bábís would do the same. Bahá'u'lláh saw it was time to end His two-year seclusion.

When Bahá'u'lláh had left Baghdád, it was to avoid being the cause of further discord and disunity in the community. He was now returning because without Him, the Bábí community of Baghdád would soon cease to exist. As Bahá'u'lláh told Shaykh Sulṭán: "By God besides Whom there is none other God! But for My recognition of the fact that the blessed cause of the Primal Point was on the verge of being completely obliterated, and all the sacred blood poured out in the path of God would have been shed in vain. I would in no wise have consented to return to the people of the Bayán, and would have abandoned them to the worship of the idols their imaginations had fashioned."

In the Kitáb-i-Íqán, Bahá'u'lláh gives us insight into the powerful spiritual forces that guided His decision to end His seclusion: “From the Mystic Source there came the summons bidding Us return whence We came. Surrendering Our will to His, We submitted to His injunction.”

Momen, Moojan, Bahá'u'lláh, A Short Biography, pages 41-42.

Reference to Moojan Momen graciously shared by Earl Redman from his historical research for The Apostles of Bahá’u’lláh and the Disciples of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, forthcoming at George Ronald.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

As a last farewell to Kurdistán, and Bahá'u'lláh's restful years, a pleasant image of the idyllic scenery near the village of Kunamasi, exactly halfway between Sar-Galú and Sulaymániyyih. Photograph by Zirguezi. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

In early 1856, Bahá'u'lláh bid farewell to the shaykhs of Sulaymáníyyih, His most passionate, and later His most faithful followers. Bahá'u'lláh left behind a host of admirers and supporters who bitterly grieved His departure, but He would keep in contact with them, and some would enter His presence in Baghdád and receive momentous Tablets from His Pen.

In the company of Shaykh Sulṭán, Bahá'u'lláh retraced His steps back to His family, back to the Bábí community in shambles, and back to Baghdád, on the banks of what Bahá'u'lláh called "the River of Tribulations," ending His seclusion in Kurdistán in slow, easy stages.

In a sad moment of foretelling, Bahá'u'lláh would tell Shaykh Sulṭán that these last days of His seclusion would be “the only days of peace and tranquility” left to Him, “days which will never again fall to My lot.”

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

BETRAYAL© Violetta Zein.

While Bahá’u’lláh’s greatness was being unveiled in Kurdistán, back in Baghdád, the situation in the Bábí community was rapidly worsening. Mírzá Yaḥyá and Siyyid Muḥammad were pleased and bolstered by Bahá'u'lláh’s sudden and lengthy absence, and they busily extended the range of their wicked activities.

Devoured by paranoia, Mírzá Yaḥyá spent most of his time shuttered inside his house, directing a smear campaign aimed at discrediting Bahá'u'lláh through letters handed to Bábís he trusted.

Mírzá Yaḥyá was also incredibly scattered in his plotting. He managed to convince the young and confused Mírzá Áqá Ján to travel to Persia and attempt to assassinate Naṣiri'd-Dín Sháh. But he also wanted an eminent Bábí named Dayyán assassinated, because he felt threatened by him. And he ordered the assassination of the Báb’s cousin, Mírzá ‘Alí-Akbar, a fervent admirer of Dayyán, which was carried out.

Mírzá Yaḥyá and Siyyid Muḥammad forever stained the annals of the Faith by dishonoring the Báb in the vilest possible manner. He married the Báb’s second wife, Fáṭimih Khánum, and one month later, gave her to Siyyid Muḥammad in marriage. When Bahá'u'lláh learned of this, His grief knew no bounds and spoke about the stain on the name of the Báb calling it “the dishonor inflicted upon the Primal Point,” and stating the act had “truly overwhelmed all lands with sorrow.”

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 1: Baghdád 1853 - 1863, page 249.

Bahá'u'lláh, Epistle to the Son of the Wolf.

SHAME © Violetta Zein.

Siyyid Muḥammad was in Karbilá, and far from being outdone by Mírzá Yaḥyá in his own irrational evil deeds, he surrounded himself with a group of thugs who became his private gang. He allowed and encouraged stealing, and they snatched the turbans off the heads of wealthy pilgrims, stole their shoes, stole divans and candles from the Shrine of the Two Imáms, and robbed drinking cups from public fountains.

In the two years that Bahá'u'lláh was living in seclusion in Kurdistán, twenty-five Bábís declared themselves the Promised One foretold by the Báb.

Bábís were so humiliated by the behavior of Mírzá Yaḥyá and Siyyid Muḥammad’s followers that barely appeared in public, and when they did, they were insulted and abused equally by Kurds and Persians in the streets, and the Bábí Faith was openly berated in Baghdád.

By late 1855, the situation had gotten so tragic, and the reputation of the Faith so degraded, that even Mírzá Yaḥyá wrote to Bahá'u'lláh asking Him to return, and this was when Shaykh Sulṭán had been dispatched to Kurdistán to bring Bahá'u'lláh back.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

The absence of Bahá'u'lláh 1 of 6: Each graphic in this section represents loss, sadness, and separation, but in each graphic, a sun shines through in the north-east, symbolizing Bahá'u'lláh’s presence in Sulaymáníyyih, and His eventual return. © Violetta Zein.

On the morning of 10 April 1854, ‘Ásíyih Khánum and the children, the rest of Bahá'u'lláh’s relatives and companions woke up to find He had vanished, one year and two days after arriving in Baghdád. When Ásíyih Khánum, 'Abdu'l-Bahá, and Bahíyyih Khánum realized He was well and truly gone, their grief was so intense that they clung to each other in their sadness and in their anxiety.

Before leaving, Bahá'u'lláh had offered Mírzá Yaḥyá the hospitality of His Family and Mírzá Yaḥyá moved in with his wives, making the Holy Family’s lives a living nightmare with his impossible demands, his deep paranoia, his cynicism and his distrust of everyone.

He was so paranoid that he forbade the Holy Family from associating with anyone, and kept the house locked at all times, forbidding anyone to go out, even to the public bath. Mírzá Yaḥyá expected that he his wives be made comfortable at all times, wanting only the finest things and constantly complaining about food.

The Holy Family bore this burden and tolerated Mírzá Yaḥyá's tyrannical demands out of love for Bahá'u'lláh and because He had asked them to, for reasons and out of wisdom inscrutable to all save Him.

Lady Blomfield, The Chosen Highway, page 51.

Baharieh Rouhani Ma'ani, Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees, pages 102-103, 135.

The absence of Bahá'u'lláh 2 of 6: Each graphic in this section represents loss, sadness, and separation, but in each graphic, a sun shines through in the north-east, symbolizing Bahá'u'lláh’s presence in Sulaymáníyyih, and His eventual return. © Violetta Zein.

Between 1854 and 1856, Ásíyih Khánum was managing a household which included the tyrannical Mírzá Yaḥyá’s several wives, and raising three children, 'Abdu'l-Bahá and Bahíyyih Khánum, 10 and 8 in 1854, and her one-year-old baby, ‘Alí Muḥammad.

What little we know of Ásíyih Khánum's sufferings during Bahá'u'lláh’s seclusion in Kurdistán comes from the untranslated 25 December 1939 letter which Shoghi Effendi wrote on the occasion of laying her remains to rest on Mount Carmel. Ásíyih Khánum endured two years of blame, criticism and slander by envious Bábís, and suffered humiliation, cruelties and transgressions at the hands of the stirrers of mischief. She also suffered the loss of her baby.

Baharieh Rouhani Ma'ani, Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees, page 103.

Shoghi Effendi, 25 December 1939 letter addressed to to the Bahá’ís of the East.

The absence of Bahá'u'lláh 3 of 6: Each graphic in this section represents loss, sadness, and separation, but in each graphic, a sun shines through in the north-east, symbolizing Bahá'u'lláh’s presence in Sulaymáníyyih, and His eventual return. © Violetta Zein.

'Ali-Muḥammad, the precious son Ásíyih Khánum had carried during their three-month frozen journey from Persia to ‘Iráq was born a few months after their arrival, sometime in July 1853.

Sometime between 1854 and 1856 while Bahá'u'lláh was in Sulaymáníyyih, 'Ali-Muḥammad became seriously ill. Consumed by paranoia, Mírzá Yaḥyá, would not allow a doctor or even a neighbor to come and help Ásíyih Khánum, and 'Ali-Muḥammad passed away. His death broke Ásíyih Khánum's already grieving heart. She had lost her seven-year-old son, also named 'Ali-Muḥammad while Bahá'u'lláh was in Karbilá.

Mírzá Yaḥyá, would not allow 'Ali-Muḥammad a proper burial, refusing to allow anyone to enter to prepare the baby’s body for burial, and the child of Bahá'u'lláh, the Supreme Manifestation of God, was given to an anonymous person to bury. The family never found out where 'Ali-Muḥammad was laid to rest.

Lady Blomfield, The Chosen Highway, page 51.

Baharieh Rouhani Ma'ani, Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees, page 103.

The absence of Bahá'u'lláh 4 of 6: Each graphic in this section represents loss, sadness, and separation, but in each graphic, a sun shines through in the north-east, symbolizing Bahá'u'lláh’s presence in Sulaymáníyyih, and His eventual return. © Violetta Zein.

‘Abdu'l-Bahá had recognized Bahá'u'lláh as a Manifestation of God, recognizing the full glory of His Father’s unrevealed station, before Bahá'u'lláh’s departure from Baghdád. That recognition had prompted 'Abdu'l-Bahá, still a young child, to throw Himself at Bahá'u'lláh’s feet and spontaneously implore for the privilege of laying down His life for Bahá'u'lláh’s sake.

Separation from Bahá'u'lláh consumed 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s soul with grief and loneliness, and the shock of the sorrow from the separation had made 'Abdu'l-Bahá grow old in His boyhood.

'Abdu'l-Bahá occupied His time during Bahá'u'lláh’s absence by copying the Báb’s Tablets helping His mother as much as possible, and spending time with His uncle, Mírzá Músá, who took Him to Bábí meetings, where 'Abdu'l-Bahá spoke with marvelous eloquence despite being 11 or 12.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Esslemont, J.E., Bahá’u’lláh and the New Era.

Baharieh Rouhani Ma'ani, Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees, pages 103-104.

Lady Blomfield, The Chosen Highway, pages 51 and 53.

The absence of Bahá'u'lláh 5 of 6: Each graphic in this section represents loss, sadness, and separation, but in each graphic, a sun shines through in the north-east, symbolizing Bahá'u'lláh’s presence in Sulaymáníyyih, and His eventual return. © Violetta Zein.

Bahíyyih Khánum was eight when Bahá'u'lláh left for Kurdistán, and 10 when He returned. During those two years, she helped Ásíyih Khánum with household chores, her work significantly increased when Mírzá Yaḥyá and his wives moved in. One of her more arduous tasks was drawing water from the well with a bucket at the end of a long rope, and in her memoirs, Bahíyyih Khánum recalled that Mírzá Yaḥyá had never once offered to help her.

Bahíyyih Khánum lived these two years of Bahá'u'lláh’s absence in utter loneliness. 'Abdu'l-Bahá, as a young boy, was allowed to leave the house with Mírzá Músá, but she was a girl, and did not have the same freedoms. Two little girls her age lived next door, but Mírzá Yaḥyá forbade Bahíyyih Khánum from playing with them or from inviting them to come inside and play with her, and so she could only watch them from her house.

Baharieh Rouhani Ma'ani, Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees, page 133-135.

Myron Phelps, The Master in ‘Akká, page 22.

Lady Blomfield, The Chosen Highway, page 51.

The absence of Bahá'u'lláh 6 of 6: Each graphic in this section represents loss, sadness, and separation, but in each graphic, a sun shines through in the north-east, symbolizing Bahá'u'lláh’s presence in Sulaymáníyyih, and His eventual return. © Violetta Zein.

Mírzá Músá watched over Bahá'u'lláh's family during His absence. He also searched for Bahá'u'lláh, and spoke with Ásíyih Khánum about His whereabouts. Eventually, it was Mírzá Músá and 'Abdu'l-Bahá who located Bahá'u'lláh in Sulaymáníyyih.

Between 1854 and 1856, Mírzá Músá also kept watch on the Bábí community, doing everything in his power to protect the innocent from the fallout of Mírzá Yaḥyá and Siyyid Muḥammad's evil doings.

During Bahá'u'lláh's absence, the life of the brave, faithful, and loyal Mírzá Músá was constantly in danger. He lived on the edge of an abyss, each day worse than the next, but Mírzá Músá was fearless, and bore all his tests with courage and confidence until Bahá'u'lláh's return.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Memorials of the Faithful.

The house of Bahá'u'lláh in Baghdád, where the Holy Family moved while He was in Kurdistán. Source: Taazakh Khabar News.

The Holy Family’s life greatly improved when they moved into Mírzá Músá's home, the house of a man called Sulaymán-i-Ghannám, located in the Karkh quarter of Baghdád, on the western bank of the Tigris river. This was the home Bahá'u'lláh would return to and He would later give it the title of Bayt-i-A'ẓam (the Most Great House).

Mírzá Yaḥyá was so terrified of being discovered in a larger house, that he moved into a small house behind theirs with his wives. Now that he was no longer in their house, everyone breathed a sigh of relief, despite Mírzá Yaḥyá and his wives still depending on the hospitality of the Holy Family for their food.

The family now focused openly on their search for Bahá'u'lláh, which Ásíyih Khánum, 'Abdu'l-Bahá, and Mírzá Músá threw themselves into, investigating every clue, making every inquiry until it was certain that Bahá'u'lláh was in Sulaymáníyyih. Then, in mid-late 1855, the trusted and faithful Shaykh Sulṭán left Baghdád for Kurdistán to beg Bahá'u'lláh to return. Everything was in God’s hands.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Baharieh Rouhani Ma'ani, Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees, page 104.