Written and illustrated by Violetta Zein

This part covers the life of Bahá’u’lláh from the age of 51 in 1868, to the age of 53 in 1870.

An 1890s photograph showing carriages for travelers between the town of Chtaura, Lebanon, and the cities of Beirut and Damascus. These carriages perhaps help imagine what those Bahá'u'lláh traveled in 24 years earlier, in another part of the Ottoman empire might have resembled. Source: Ottoman Imperial Archives Twitter account.

The news of Bahá'u'lláh’s imminent exile profoundly shook the Bahá'í community, and Mírzá Jaf’ár, not on the list of exiles, and terrified at the idea of being separated from Bahá’u’lláh, attempted to take his own life. Two Bahá'ís were forced to divorce their wives because their families would not allow their daughters to be banished with their husbands, and pilgrims who arrived in Adrianople at that time, were instructed to leave for Gallipoli upon arriving.

Bahá'u'lláh paced His garden, the only place He walked in Adrianople, and Bahá'ís crowded around Him weeping, refusing to be comforted, all of them determined not to be wrenched from their Beloved.

Bahá'u'lláh’s companions began the week-long complex preparations for their arduous journey, bringing in several carts to carry the luggage, which were sent ahead, along with several Bahá'ís and at least two Azalís, Mírzá Yaḥyá and Siyyid Muḥammad-i-Iṣfahání.

HOW THE DATE WAS CALCULATED

The memoirs of Áqá Riḍá state that a week of preparations preceded the departure on 12 August 1868, seven days were counted backwards from 12 August which gave us 6 – 12 August for the week of preparation.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Lady Blomfield, The Chosen Highway, page 62.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 257-259.

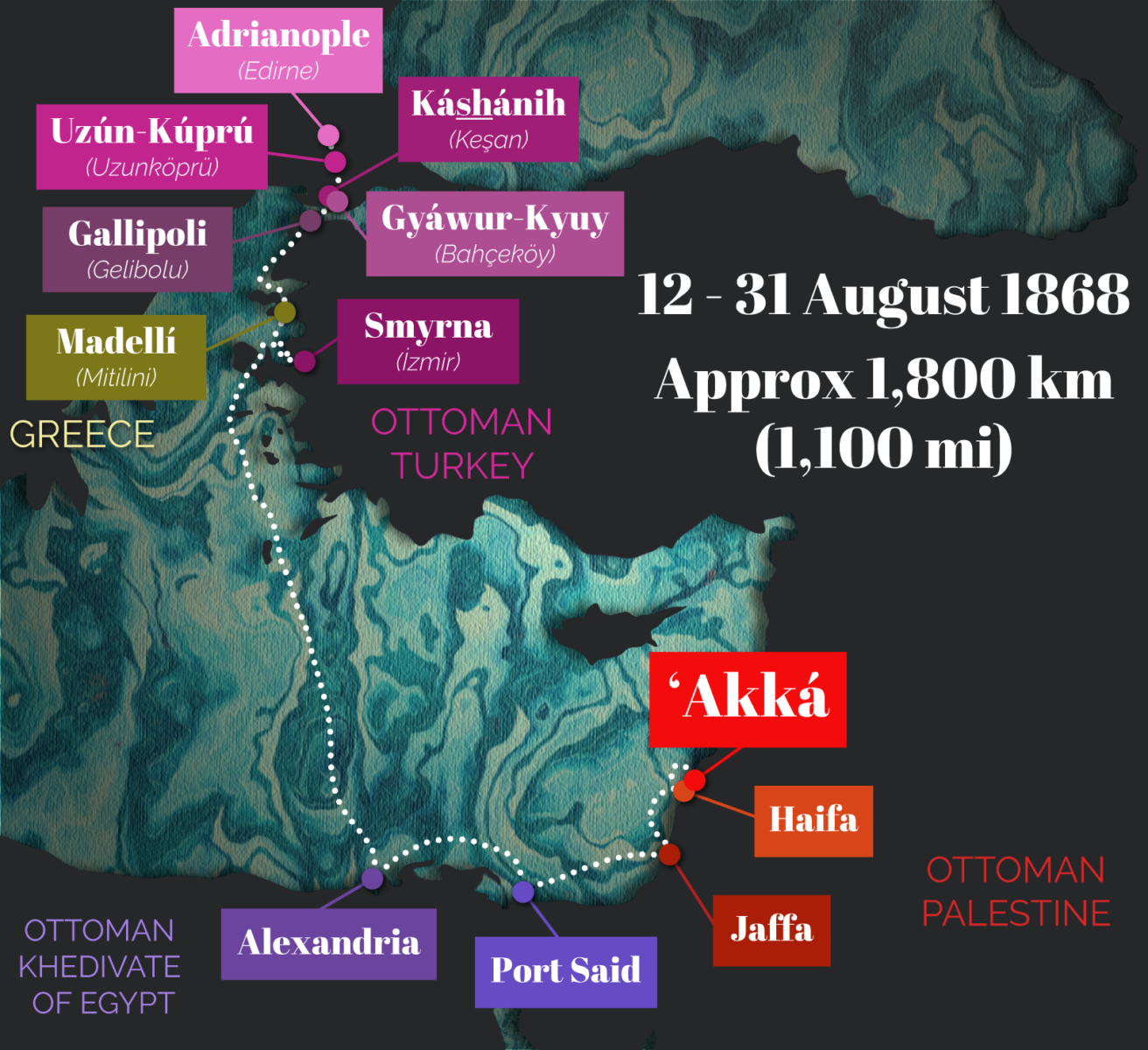

Hand-drawn map showing locations of Bahá'u'lláh's land and sea journey to His final exile in 'Akká mentioned by Shoghi Effendi in God Passes By. Map traced from the 1860 map of Persia, Turkey in Asia, Afghanistan, and Beloochistan by Samuel Augustus Mitchell; Source: Wikimedia Commons. © Violetta Zein.

Travel in the 1860s throughout the sprawling Ottoman Empire was uncomfortable, to say the least. The development of railroads was so slow that sea and overland voyages by horses, mules, oxen, and camels, carts, carriages, and howdas were the main modes of travel.

Almost none of the roads in the Ottoman Empire were paved, except for cities, and in most areas, these soon gave way to packed dirt roads, which turned into country roads, pocked with holes and strewn with rocks, and very uncomfortable to travel on. It sometimes took dozens of hours to cover distances that could be covered in three or four hours on European roads, with a difficult climate, sweltering hot in the summer and below freezing in the winter, when the roads froze or became muddy and sticky. The roads were all unmarked, and unlit at night, and a significant number of travelers got lost on caravan routes.

The journey to 'Akká from Adrianople was nearly 1,800 kilometers (1,100 miles), one-tenth of the voyage overland, and the rest by steamer. Bahá'u'lláh moved through four countries during this journey: Ottoman Turkey until Gallipoli, Greece with a brief stop in Madellí, Egypt, and Ottoman Palestine.

The voyage was emotionally stressful for Bahá'u'lláh’s family and companions, because threat of separation hovered over the entire trip until Palestine. Added to this almost unbearable stress, food was scarce, sailing conditions were horrifying, and most of the companions fell ill.

Archeologists & Travelers in Ottoman Lands: Travel in the Ottoman Empire.

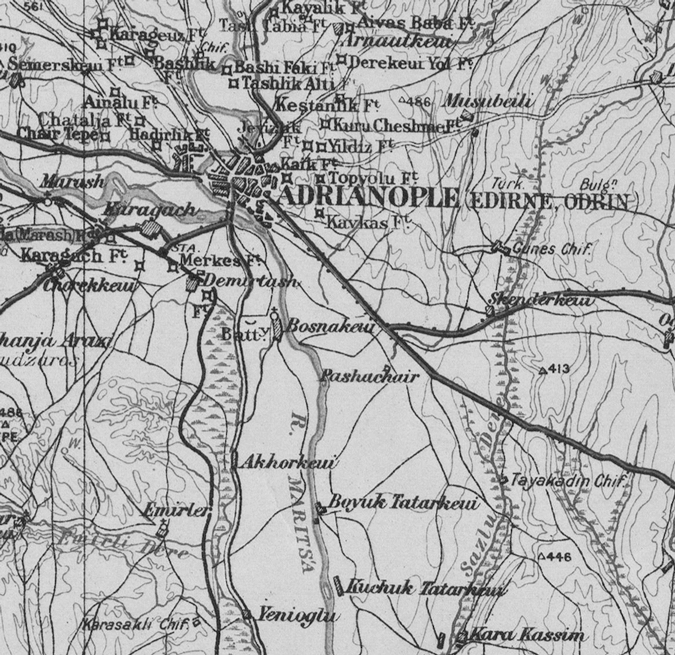

Detail from a 1906 British War Office map of Adrianople focusing on the road south from the city, taken by Bahá'u'lláh overland towards Gallipoli. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

On Wednesday 12 August 1868, the horse-drawn wagons arrived at the house of ‘Izzat Áqá in the morning, and the last of the luggage had been gathered and loaded around noon. Bahá'u'lláh exited the house and showered His love on Mírzá Jaf’ár, the young man who had tried to take his own life, entrusting him to the care of his doctor and the landlord, then turned His loving attention to His gathered followers.

A crowd of Muslims and Christians had come to bid Bahá'u'lláh farewell, and expressed their profound sorrow and regret at His departure and their grief at being deprived of His presence, some kissing His hands and the hem of His robe. By the time Bahá'u'lláh left, most of them were crying, most noticeably the Christians.

Their escort for the journey was an Ottoman captain named Ḥasan Effendi, leading soldiers appointed by the government of Adrianople, and leaving Adrianople, their home for nearly five years, Bahá'u'lláh and His companions started their journey south.

In the Súriy-i-Ra’ís, composed nearly halfway to Gallipoli, Bahá'u'lláh tells ‘Alí Páshá about His departure from the “Remote Prison, stating that, as He left He “deposited beneath every tree and every stone a trust, which God will erelong bring forth through the power of truth.”

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

1915-1920 photograph depicting a family traveling the desert in a caravan in the Middle East during the Arab Revolt. The image is offered as a symbolic visual illustration of carriage travel, since we know so little about the types of carriages Bahá'u'lláh and His family traveled in, and so few images of Ottoman carriages from that time are available online. Source: Library of Congress.

Bahá'u'lláh and His family arrived at the first of five stages in their journey, three hours away from Adrianople, as the night fell on 12 August 1868, they set up camp and stayed the night before resuming their journey the next morning.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 259.

The long bridge (Uzunköprü) that gave the town its name, and most probably crossed by Bahá'u'lláh on 13 August 1868 when He entered the town, the second stage of His journey to Gallipoli. Photograph by Dosseman - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

On 13 August 2868, Bahá'u'lláh and His companions arrived in Uzún-Kúprú, the second largest city in the province of Adrianople and a strategically important border town at the crossroads of western routes to Europe and the Balkans and southern destinations such as Egypt and the Middle East. The exiles stayed over night in this city named after its iconic 15th century “long bridge,” perhaps the largest stone bridge in the world.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 259.

Wikipedia: Uzunköprü.

Wikipedia: Uzunköprü bridge.

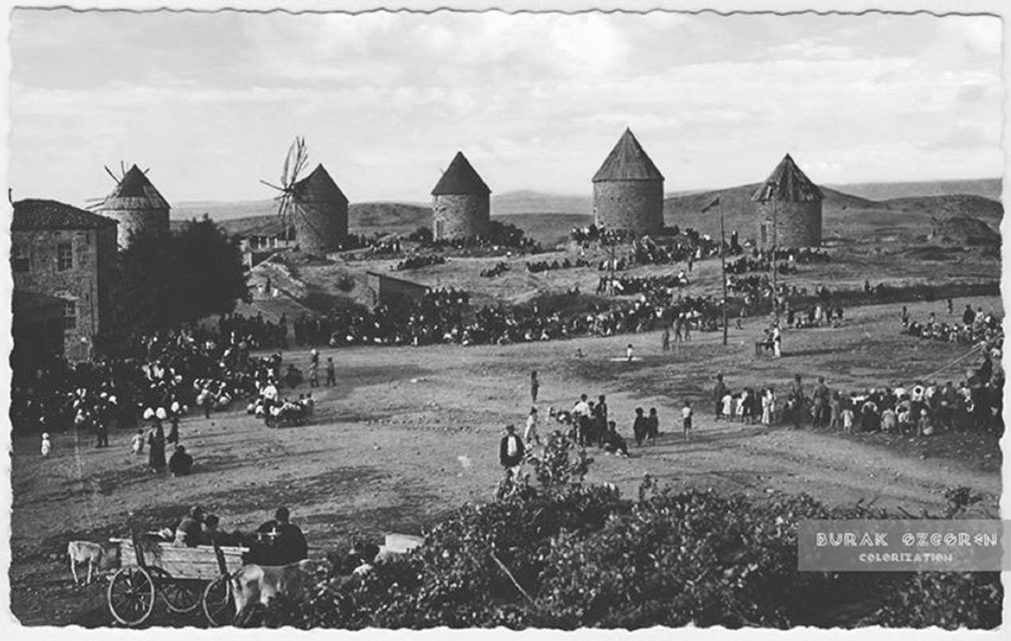

Undated colorized photograph depicting Keşan’s famous windmills. Source: KEŞAN (ZERLANİS).

Arriving in Káshánih, Bahá'u'lláh resumed the first phase of His public Proclamation begun in Adrianople by revealing a significant Tablet, the Súriy-i-Ra’ís (Surah to the Chief), addressed to the Sulṭán’s Grand Vizir.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 259.

Wikipedia: Keşan.

Trakyanet: Tahiri.

Keşan's Digital Photography Museum Facebook Page, KEŞAN (ZERLANİS): Keşan'in tarihi fabrikalari : yel değirmenleri (Historical factories of Keşan : Wind mills) (in Turkish).

Keşan's Digital Photography Museum Facebook Page, KEŞAN (ZERLANİS): Kisaca; Keşan tarihi (A brief history of Keşan) (in Turkish)

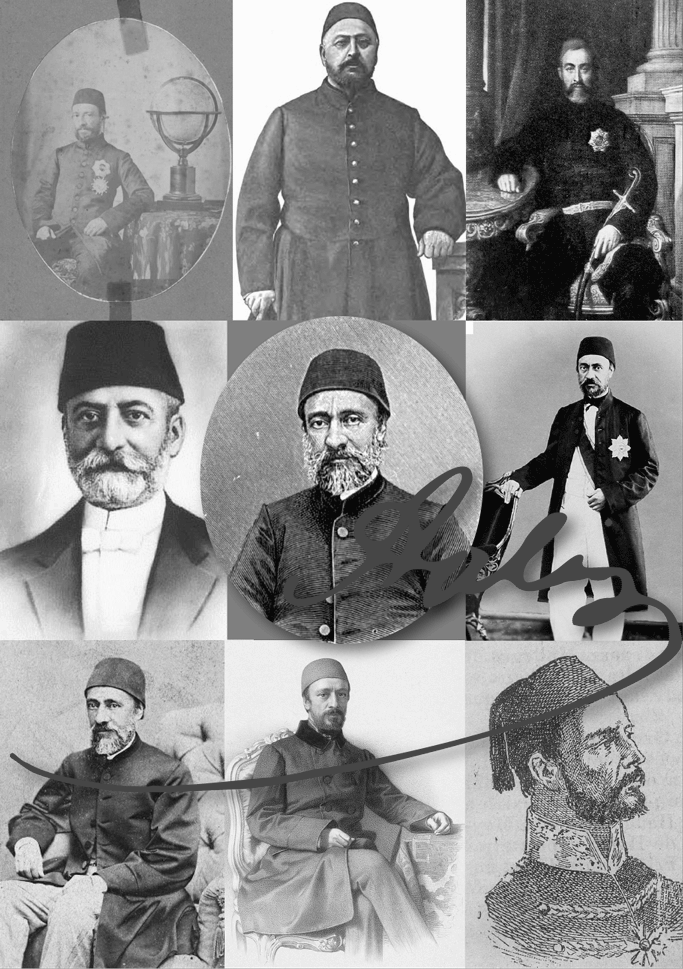

Collage of every photograph or engraving of Mehmet Emin 'Alí Páshá (1813 - 1871), five times Prime Minister (Grand Vizier) to Sulṭán 'Abdu'l-Azíz, apostrophized in the Súriy-i-Ra'ís. Source: All photos and signature from Wikimedia Commons.

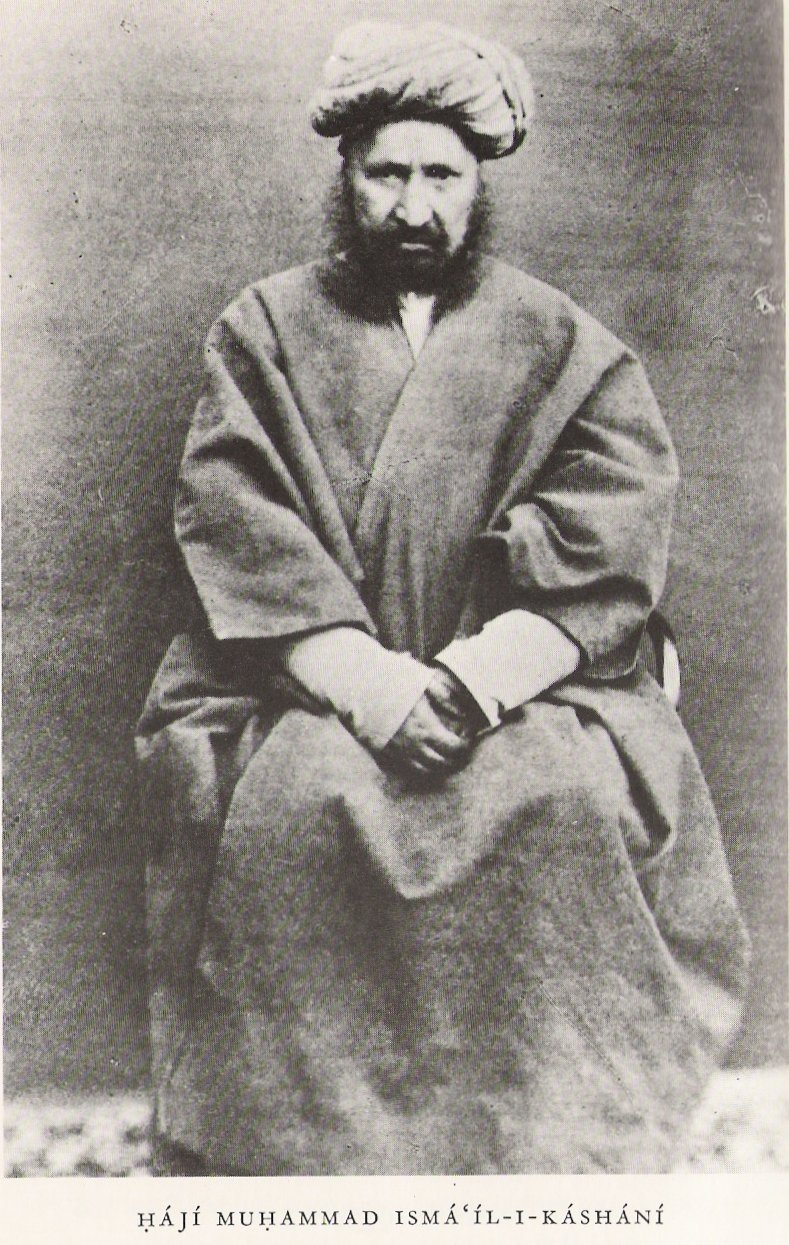

Ḥájí Muḥammad Ismá'íl-i-Káshání (Dhabíḥ), in whose honor the Súriy-i-Ra'ís was revealed. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Bahá'u'lláh began revealing the Súriy-i-Ra’ís, in the village of Káshánih (Keşan), at the third stage of His journey towards Gallipoli (Gelibolu), in honor of Dhabíḥ, a faithful believer who had hosted the Báb in his home. Three quarters of this Tablet are addressed to Dhabíḥ, and the last quarter is addressed to ‘Alí Páshá.

Muḥammad Amín ‘Alí Páshá (Mehmet Emin Ali Pasha) was a career politician, who had climbed to the highest rungs of power from humble beginnings as the son of a doorkeeper. At 26 he was the Ottoman ambassador for France, held the posts of Foreign Minister and Grand Vizir five times each. ‘Alí Páshá was part of a small group of dedicated Ottoman statesmen determined to modernize their country, but he was authoritarian, overbearing, and unfair in his judgment.

Addressing him as “Chief,” Bahá'u'lláh rebukes ‘Álí Páshá with the language of might and power, declaring that neither his “grunting,” nor the “barking” of those around him, nor “the hosts of the world” would be capable of hindering God from achieving His purpose. Bahá'u'lláh proclaims the greatness of His revelation and His purpose to “quicken the world and unite all its peoples,” foreshadow that His Revelation would soon “encompass the earth and all that dwell therein,” and prophesying that Adrianople and the rest of Ottoman land would “pass out of the hands of the King, and commotions shall appear, and the voice of lamentation shall be raised, and the evidences of mischief shall be revealed on all sides.”

In the part of the Tablet addressed to Dhabíḥ, Bahá'u'lláh speaks of the youth who had tried to take his own life in Adrianople, and makes a powerful statement about adversity and the Covenant: “Say: Adversity is the oil which feedeth the flame of this Lamp and by which its light is increased, did ye but know.” A particularly astounding part of this Tablet is when Bahá'u'lláh speaks as the Prophet Muḥammad, Abraham and Moses, declaring their allegiance to the Bahá'í Faith, here is the first section, where Bahá'u'lláh speaks in the voice of the Prophet Muḥammad: “Had Muḥammad, the Apostle of God, attained this Day, He would have exclaimed: 'I have truly recognized Thee, O Thou the Desire of the Divine Messengers!'”

Highlighted area of the journey from Adrianople to Gallipoli showing the two villages where the Súriy-i-Ra'ís was revealed. Source for the base map, a 1907 Ottoman map of the Adrianople Vilayet: Wikimedia Commons. © Violetta Zein.

Partial Inventory ID: BH00260

Steven Phelps "The Writings of Bahá'u'lláh" in Routledge World: The World of the Bahá'í Faith, First Edition, Edited By Robert H. Stockman, page 64.

Bahá’u’lláh, Súriy-i-Ra’ís.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868, pages 411-421.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, Appendix V: Biographical Notes: ‘Alí Páshá, Muḥammad Amín, page 469.

Wikipedia: Mehmed Emin Âli Pasha.

DATE

The five-day journey to Gallipoli began on 12 August and Káshánih was the third stage, we estimate Bahá'u'lláh arrived on 14 August 1868. Bahá'u'lláh left the next morning for Gyáwur-Kyuy 9 kilometers (5.5 miles) away, so we estimate Bahá'u'lláh completed the revelation of this Tablet on 15 August 1868.

Digital interpretation of a Google Maps user photograph for Bahçeköy, on the outskirts of Keşan, where Bahá'u'lláh stopped briefly around 15 August 1868. The artwork shows a flock of birds flying over rich wheat fields under a clear blue sky. The region was agricultural even at the time of Bahá'u'lláh and He traveled in summer, so perhaps this vista would have been close to what Bahá'u'lláh saw. Inspiration. © Violetta Zein.

The next day, Bahá'u'lláh completed the Revelation of the Súriy-i-Ra’ís in the village of Gyáwur-Kyuy (Bahçeköy), 9 kilometers (5,5 miles) away from Káshánih.

Source for this stage: own research and Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

The region of Eastern Thrace is one of panoramas of low hills and cultivated cereal fields. As we were not able to find any information on the location of this stop in Bahá'u'lláh's journey, this composite of agricultural lands in the region is a symbolic illustration of the vistas Bahá'u'lláh crossed on His way south to Gallipoli. Source: Photo by Tim Mossholder from Pexels.

It stands to reason that the last stop in the overland journey occurred approximately halfway between Káshánih and Gallipoli, their destination, which would be reached the next day. This last stage probably occurred at the northern top of the narrow peninsula of Gallipoli, between the sea of Marmara and the Thracian sea.

During the journey, Bahá'u'lláh had evinced the same loving-kindness and concern towards His fellow-exiles as He had during His three-month march to Constantinople five years prior, immediately stopping the caravan and sending out horsemen in every direction if a believer strayed or fell asleep and was left behind, refusing to move forward until he was found.

Source for this stage: own research

Source for the story of lost companions: 'Alí-Akbar Furútan, Memories of Bahá'u'lláh, page 41.

This stunning photograph of the northern approach towards Gallipoli depicts World War I fortifications that would of course not been present at the time of Bahá'u'lláh, but the photograph is taken from a spot EXACTLY on the route the caravan took to arrive in Gallipoli, and therefore perhaps depicts a scene not unlike the one the eyes of Bahá'u'lláh may have witnessed on 16 August 1868. Photograph by Julian Nyča, Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0. SOURCE: Wikimedia Commons.

On the morning of 16 August 1868, Bahá'u'lláh and His companions traveled approximately 30 kilometers (19 miles) south from the east Thracian wheatfield plains down the narrow Gallipoli peninsula, jutting out between the seas of Marmara and the Thracian sea, traveling through spectacular landscape surrounded by two seas to the east and the west. Once they arrived in Gallipoli, the easiest and shortest part of the journey was ended. Soon, the arduous sea journey would begin.

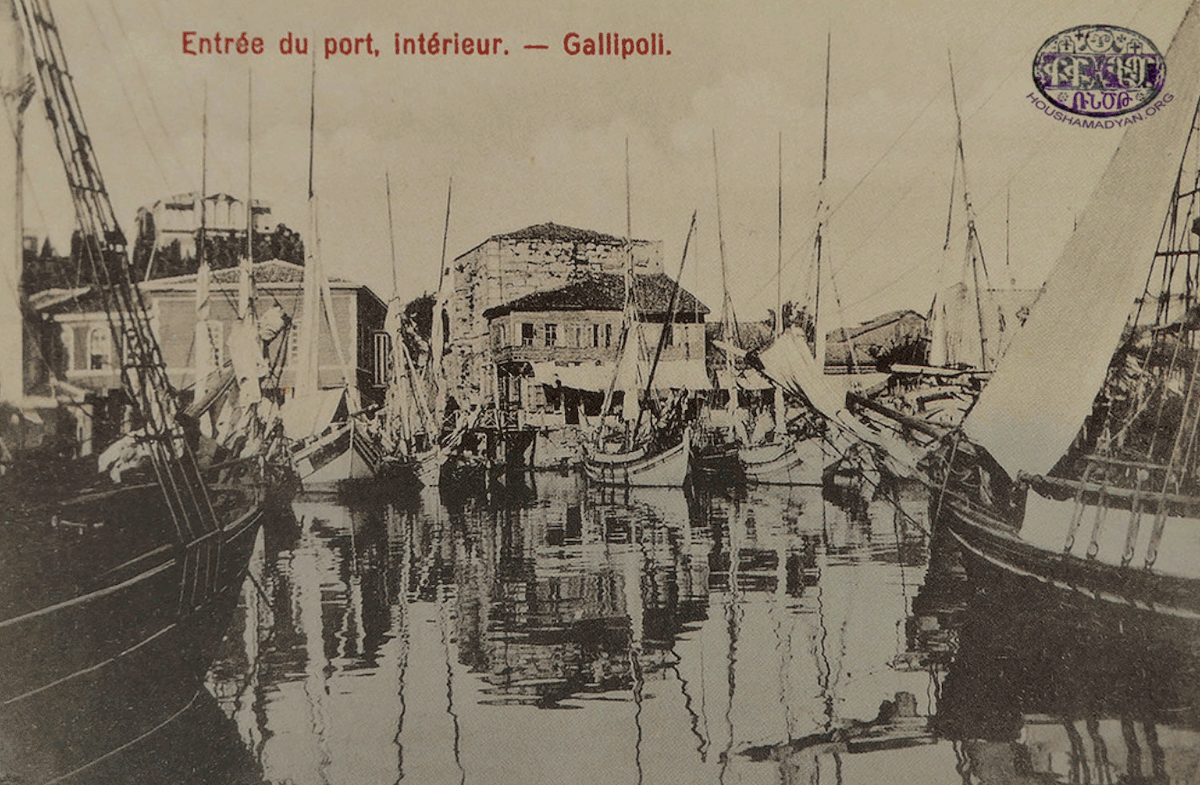

Postcard with a view of the Captan Malahessi neighborhood, near the port in Gallipoli (Gelibolu). Houshamadyan Website.

Apprehension and uncertainty loomed in Gallipoli. The Governor of Gallipoli informed the exiles they were to be separated in four separate groups, each sent to several different locations with no knowledge of each other’s whereabouts. Bahá'u'lláh and a man-servant were to be banished to one location, 'Abdu'l-Bahá and another servant exiled somewhere else, the Holy Family would be directed to Constantinople, and the rest of the believers would be split up and sent to various places.

'Abdu'l-Bahá told the Governor: “Do this, take us out on a steamer and drown us in the ocean. You can thus end at once our sufferings and your perplexities, but we refuse to be separated.” The Governor took a liking to Bahá'u'lláh and 'Abdu'l-Bahá, and helped them, sending many telegrams to Constantinople on their behalf. Most of the time the exiles were in Gallipoli was spent anxiously waiting for answers to those telegrams.

Another troubling uncertainty was that no one knew what Bahá'u'lláh’s final destination was. Many rumors floated around, that Bahá'u'lláh, Mírzá Músá, and Mírzá Muḥammad Qulí would be exiled together, that everyone would be extradited back to Persia, or that they would all be executed.

Three days after their arrival in Gallipoli, on 19 August 1868, the Ottoman major, 'Umar Effendi finally confirmed that the exiles would not be separated. The Sulṭán’s edict for their separation had been revoked a second time, a success due to in large part to Bahá'u'lláh’s insistence, 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s eloquence and willpower, and the aid of sympathetic Ottoman officials.

The exiles were to be split into two groups: 72 people including Bahá'u'lláh, His immediate family, the Bahá'ís and two Azalís, Siyyid Muḥammad-i-Iṣfahání and Kaj-Kuláh, would remain together, while Mírzá Yaḥyá, the Azalís, and four Bahá'ís would be sent to Cyprus. The Ottoman government would cover the fees only of those individuals on the register, the rest would have to pay their own way.

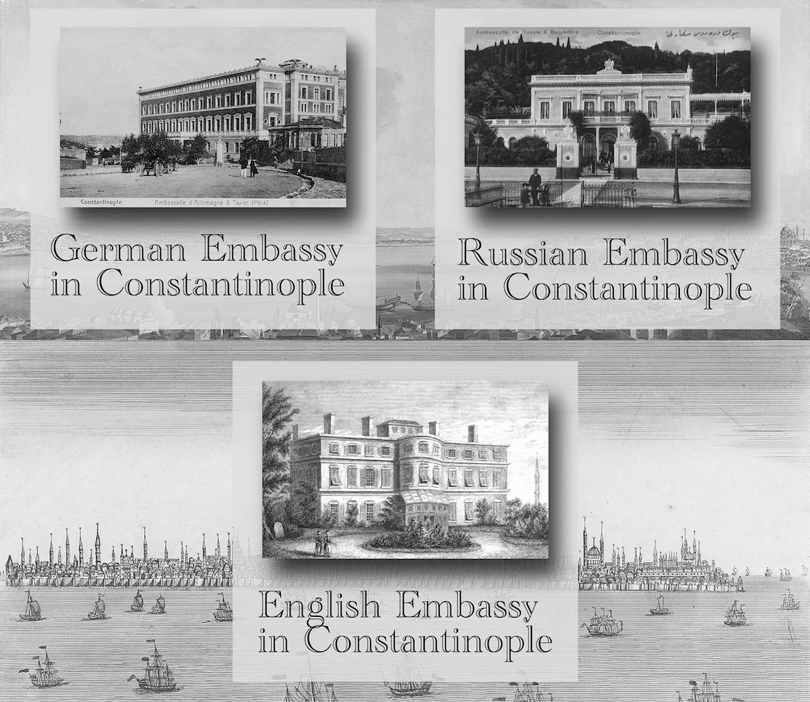

As a tribute to the three consuls that reached out to Bahá'u'lláh in Gallipoli, the embassies of Germany, Russia, and England, all from Wikimedia Commons, linked to the country name. Background composed of 18th century paintings of Constantinople, also from Wikimedia Commons, top and bottom. © Violetta Zein.

A house had been set aside for the exiles in Gallipoli. Bahá'u'lláh, His family and the women exiles occupied the upper floor, while several Bahá'ís were housed on the ground floor, and the rest of the exiles were lodged in a caravanserai, where they found some of the Bahá'ís from Constantinople, including Mishkín-Qalam and Ustád Muḥammad-'Alíy-i-Salmání.

Ḥájí Muḥammad Ismá'íl-i-Káshání, known as Dhabíḥ (Sacrifice), in whose honor Bahá'u'lláh had revealed the Súriy-i-Ra'ís a few days ago, attained His presence in the public bath in Gallipoli.

The German, Russian and English consuls called on Bahá'u'lláh and offered a safe haven for Him and His family in a Western European country. Bahá'u'lláh’s response was the same as it always was, when consuls were offering an escape to His trials: He declined gracefully, stating He had no intention of going against Sulṭán ‘Abdu’l-Azíz’s will, and that He would never abandon His followers. Bahá'u'lláh affirmed He had nothing to fear, as His sole desire was only to summon the people of the world to God.

An 1870 photograph of Ottoman soldiers in an exercise. This photograph was taken two years after the story below involving a Major in the Ottoman Army. Source: The New York Public Library Digital Collections.

Bahá'u'lláh sent a verbal message to Sulṭán ‘Abdu’l-Azíz through ‘Umar Effendi, the Ottoman major who had accompanied the exiles to Gallipoli, and was returning to Constantinople. Umar Effendi listened meekly as Bahá'u'lláh gave him the message for the Sulṭán, in a voice that resonated with so much power and vehemence that it seemed as though the foundations of the house had shaken: “Tell the king that this territory will pass out of his hands, and his affairs will be thrown into confusion…Not I speak these words, but God speaketh them…”

Bahá'u'lláh rebuked the Sulṭán for not investigating the matter before banishing Him and for not calling on Him to present him with proofs of His Cause, and reprimanded him for listening to his ministers instead of investigating the truth, stating with great authority “He should not have allowed such wrong-doing, such enmity, such injuries, without reason, solely by following the behest of authors of mischief." ‘Umar Effendi listened carefully and promised to relay the message to the Sulṭán‘Abdu’l-Azíz.

SOURCES FOR THE LAST FOUR STORIES IN THIS SECTION

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By excerpt 1, and excerpt 2.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 260-264.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868, page 412.

Myron H. Phelps, The Master in ‘Akká, pages 69-70.

Lady Blomfield, The Chosen Highway, pages 62-63.

View of the entrance of the port of Gallipoli from inside the port. Source: Osman Köker (editor), 100 Yıl Önce Türkiye'de Ermeniler: Orlando Carlo Calumeno Koleksiyonu'ndan Kartpostallarla, Birzamanlar Yayıncılık, Istanbul). Houshamadyan.

As soon as the believers found they could travel with Bahá'u'lláh if they paid their own way, several people who were not on the official list, including Ḥájí ‘Alí-Askar, a believer from the time of the Báb, joyfully bought their passage on the steamer. 'Umar Effendi and other Ottoman officials must have wondered, probably not for the first time, who were those Bahá'ís, radiantly choosing a life of exile and imprisonment without even knowing their final destination.

In the evening of 20 August 1868, the exiles’ luggage was taken aboard the Ottoman government’s ship, an Austrian-Lloyd steamer, and the next morning, 21 August 1868, the exiles were hurried aboard. They were so rushed, no one thought of purchasing provisions for the five-day journey to Alexandria, except the believer in charge of meals. He bought a single box of bread, which would be the exiles’ only food until the reached Egypt, along with the nearly-inedible prisoners’ rations provided by the Ottoman government.

Aboard the rowboat taking Him to the ship, Bahá'u'lláh, bid a kind farewell to His sorrowful followers on the quay, then took His seat amidst the exiles on the boat, and began revealing verses, comforting and consoling His fellow travelers. Once onboard, the 72 Bahá'ís exiles were crowded together on the already-packed ship and began an ordeal in unspeakable conditions, which Bahíyyih Khánum described as “eleven days of horror.”

Before leaving Gallipoli, Bahá'u'lláh spoke to His family and followers in a way He previously had not, warning them in no uncertain terms about the dangers and trials facing Him, and cautioning them that “this journey will be unlike any of the previous journeys.” Bahá'u'lláh told them that whoever did not feel himself “man enough to face the future” should “depart to whatever place he pleaseth, and be preserved from tests, for hereafter he will find himself unable to leave.” It was fair warning and an opportunity to avoid an otherwise impossible situation, but the exiles unanimously remained aboard.

Among the passengers was the new Persian Consul to Smyrna (İzmir) and his entourage, heading to his posting. Bahá'u'lláh remained on the secluded and spacious upper deck of the ship and spoke to no one.

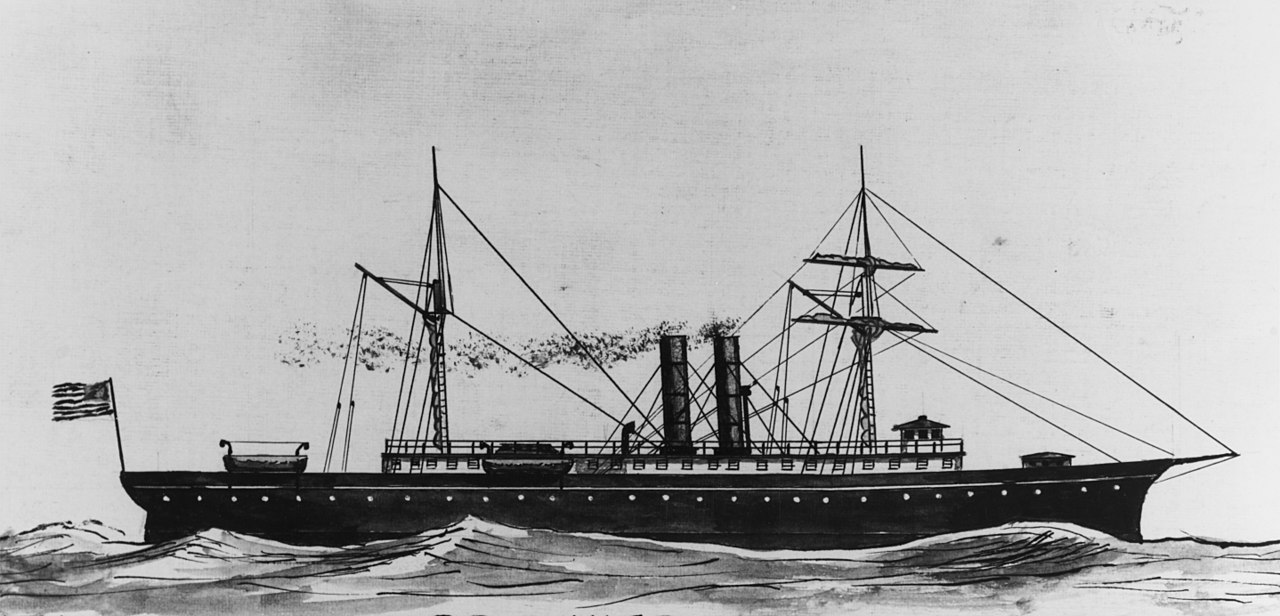

The steamship R. R. Cuyler, built in New York in 1860 for commercial service along the United States east coast. From an original watercolor by Heyl, Erik (1955). This watercolor of a steamship is an accurate depiction of the ship Bahá'u'lláh and the Holy Family would have sailed on from Gallipoli to Alexandria in 8 years' time. Image contributed by Johannes Rosenbaum. Wikimedia Commons.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 264.

Myron H. Phelps, The Master in ‘Akká, page 70.

Lady Blomfield, The Chosen Highway, pages 62-63.

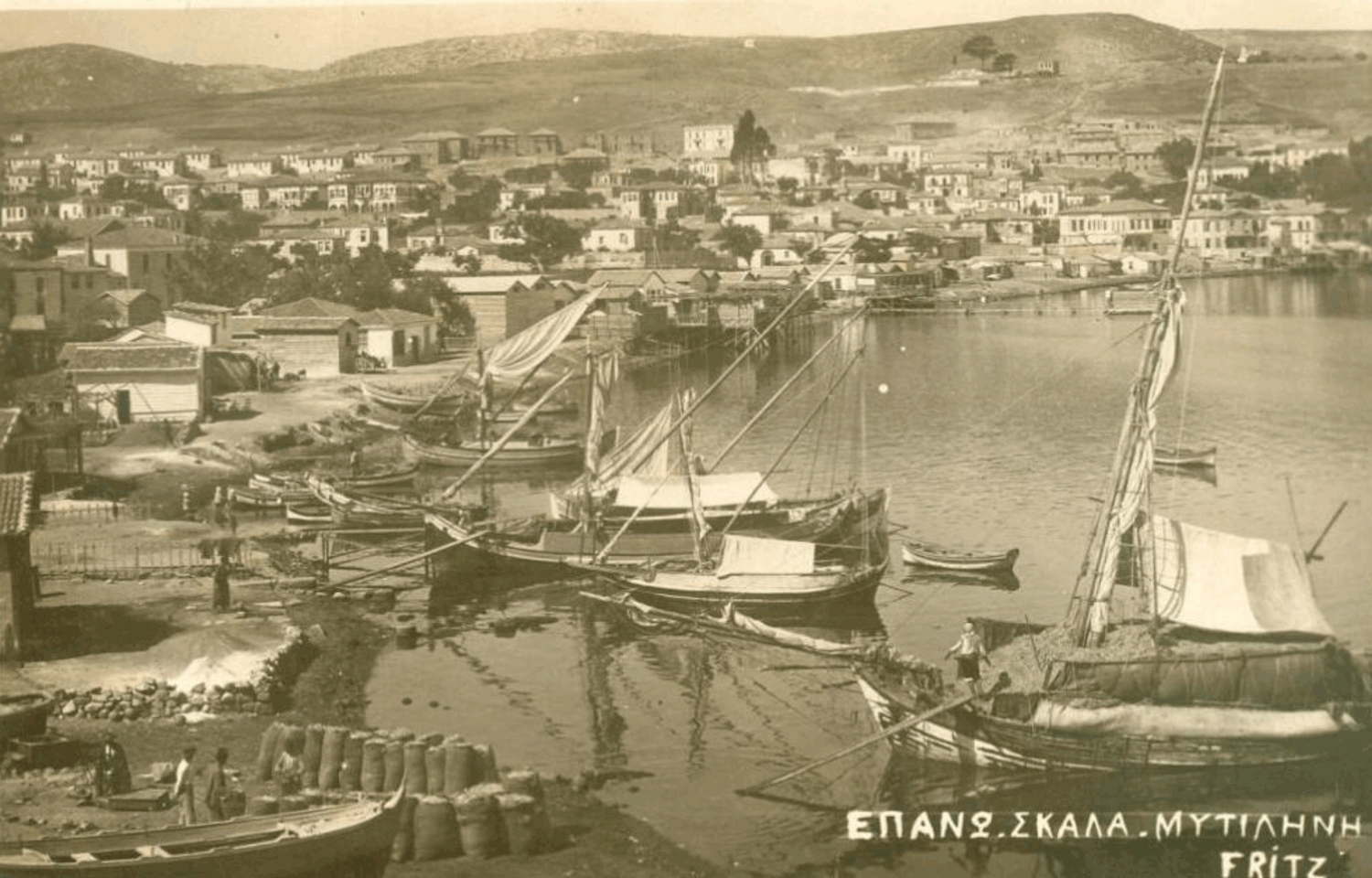

The bay of Madellí (Mitilini/Μυτιλήνη). Lesvos News Website.

Towards sunset of 21 August 1868, the steamship arrived in Madellí, on the island of Lesbos in Greece. They stopped in Madellí for a few hours, then sailed on towards Smyrna (İzmir, Turkey).

One of the exiles who had accompanied Bahá'u'lláh from Constantinople, Jináb-i-Muníb, the one who had carried a lantern in front of Bahá'u'lláh’s howdah from Baghdád, fell ill in Adrianople but refused to be left behind. His condition had worsened, and he had become so weak, that when he was brought aboard in Gallipoli, the captain had insisted he be left ashore. The exiles pleaded with the captain to let Jináb-i-Muníb travel as far as Smyrna, and he agreed.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Myron H. Phelps, The Master in ‘Akká, page 70.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 264.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Memorials of the Faithful: Jináb-i-Muníb.

Smyrna (Izmir) around 1870, just two years after Bahá'u'lláh and the Holy Family stopped in this port for two days. The ships would be similar to the ship they were on or encountered. Source: Ottoman Imperial Archives Facebook Page.

The steamer reached Smyrna (İzmir, Turkey) in the early morning of 22 August 1868, and the devoted Jináb-i-Muníb was so ill and weak that the captain spoke to Colonel ‘Umar Bayk, the government agent accompanying the Bahá'ís to ‘Akká, and insisted he be left ashore.

The Ottoman officials allowed 'Abdu'l-Bahá and His companions one hour off-ship to take Jináb-i-Muníb to the hospital. They laid him on the bed, resting his head on a pillow, held him and kissed him goodbye before being dragged away. Bahíyyih Khánum recalls that 'Abdu'l-Bahá left Jináb-i-Muníb’s bedside to go buy him a melon and some grapes, but returned to find the wise and modest man had died, an event that would stay with 'Abdu'l-Bahá until the end of His life.

The ship was anchored in Smyrna for two days, and Persian residents came onboard to escort the new Persian Consul, oblivious of Bahá'u'lláh and His followers. They set sail for Alexandria the second night, in the evening of 23 August 1868.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 264-265.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Memorials of the Faithful: Jináb-i-Muníb.

Myron H. Phelps, The Master in 'Akká, page 65.

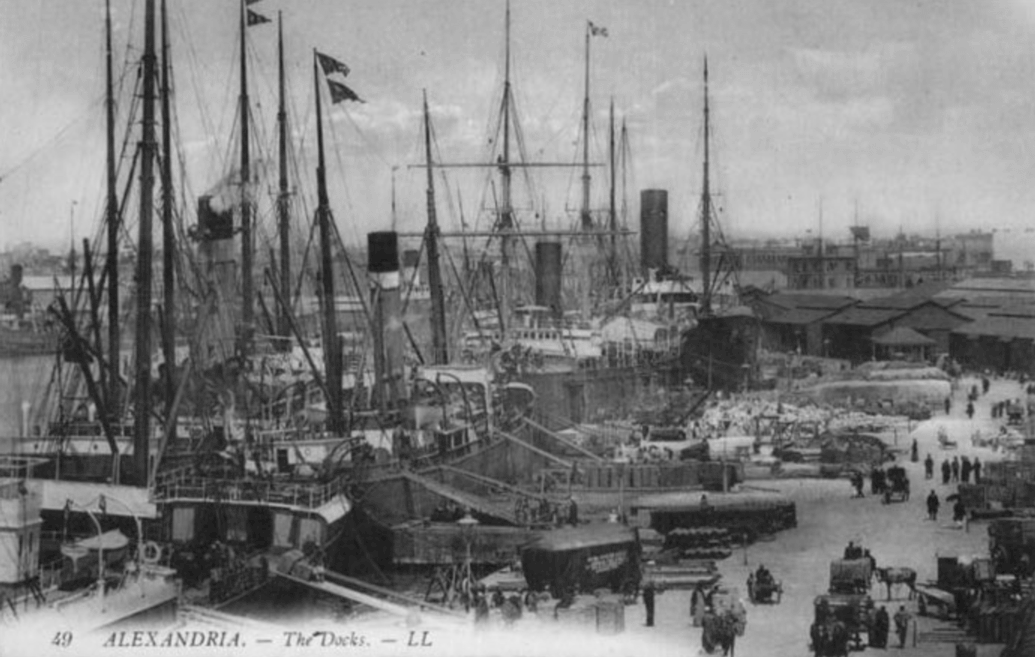

A late 19th/early 20th century postcard of the docks at the port of Alexandria, Egypt. From Levantine Heritage, all rights reserved, used with permission. For more information about the Levantine Heritage Foundation, visit their website, levantineheritage.com.

The exhausted and famished exiles arrived in Alexandria on the morning of 26 August 1868, two full days after leaving Smyrna, having traveled in nightmarish conditions, and boarded another Austrian-Lloyd steamer. The threat of separation loomed for a third time over the believers, who were by now bent over with illness, weak from hunger, and crushed by these repeated blows. Terrified of being left behind, no one dared to leave the ship to buy food, but they still managed to obtain grapes and mineral water for the next stage of the journey.

One of the believers tried to end his life by throwing himself in the Mediterranean, and was mercifully saved. A number of Persians came aboard at Alexandria to pay their respects to Bahá'u'lláh, among them a famous Ṣúfí seer named Ḥájí Pírzádih.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Myron H. Phelps, The Master in ‘Akká, pages 70-72.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 265-268.

Lady Blomfield, The Chosen Highway, page 65.

The Port of Alexandria in 1870, two years after the Holy Family stopped there, shown from the vantage point of a roof, in homage to the story of Nabíl below, watching Bahá'ulláh's ship from the roof of his prison. Antranik Tutundjian Pinterest Account.

Bahá'u'lláh had sent Nabíl on a mission to Egypt to advocate for Ḥájí Mírzá Ḥaydar ‘Alí and the six Bahá'ís who had been incarcerated. Nabil himself was soon thrown in prison, and this news had reached Bahá'u'lláh in Adrianople, but Nabíl’s exact whereabouts were unknown. It so happened Nabíl was now in an Alexandrian jail, whose roof had a view of the port.

During his detention, Nabíl had dreamt of Bahá'u'lláh several times, and in a dream he had around 6 June 1868, Bahá'u'lláh had told him: “Within the next eighty-one days, to thee will come some cause of rejoicing.” On Thursday 27 August 1868 around sunset, the eighty-first day after the dream, Nabíl was standing on the roof of the prison, and saw Áqá Muḥammad Ibráhím-i-Náẓir, the steward of the Holy Family, walking by. Áqá Muḥammad climbed up to meet Nabíl, and informed him that Bahá'u'lláh, His Family and the exiles were on their way to ‘Akká.

While in prison, Nabíl had taught the Faith to a Syrian Christian physician called Fáris Effendi, who had become a devout Bahá'í. Nabíl and Farís could not leave the prison to enter Bahá'u'lláh’s presence, so they both wrote letters to Him, and asked a friend, a young Christian watch-maker named Constantine, to deliver them to Bahá'u'lláh aboard the ship.

Nabíl set down on paper the entire story of his experience and included poems he had composed in prison. Fáris Effendi wrote a very long devoted and perceptive letter to Bahá'u'lláh. Nabíl and Fáris Effendi watched from the rooftop and were heartbroken when the ship sailed away before Bahá'u'lláh received their letters, but suddenly, the ship hove to. Constantine, aboard a rowboat, was able to board the steamship and handed the envelope to one of the attendants who gave it to Bahá'u'lláh.

After reading parts of Fáris Effendi to the believers which caused great excitement throughout the ship, Bahá'u'lláh revealed a Tablet for Nabíl in which He bestowed His bounties and blessings on Fáris, ensuring Nabíl he would soon be released from prison. Bahá'u'lláh handed the Tablet to Constantine, and 'Abdu'l-Bahá and Mírzá Mihdí gave him some gifts for Nabíl, including some nuq’l almond candy wrapped in paper.

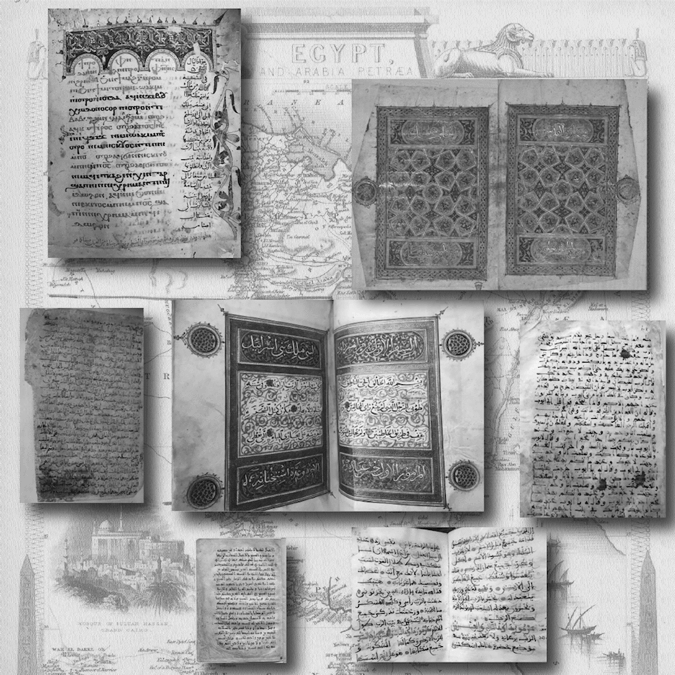

As a tribute of love to the first Christian to become a Bahá'í who was also a native Arabic speaker, Fáris Effendi, this photomontage of precious early Arabic-language Bibles. Source: Christian Arabic Bible Translations in the British Library Collections. The background of the work is a 19th century map of Egypt and Arabia petræa, published in 1851 by JK. & F. Fallis. Source: Library of Congress.

Fáris Effendi is considered to be the first Christian to embrace the Bahá'í Faith. The letter he wrote to Bahá'u'lláh in Arabic was very significant. It showed not only the depth of his faith and devotion expressed with profound feeling, but his keen spiritual perception of the station of Bahá'u'lláh, and demonstrated the enkindlement of a man recreated by embracing the Bahá'í Faith. In his letter, Fáris Effendi equated Bahá'u'lláh’s suffering to that of Jesus Christ, expressed the desire to form part of the ship Bahá'u'lláh was sailing on, and addressed the unaware city Bahá'u'lláh was leaving, saying “O Alexandria! art thou grief-stricken because He who is the Ever-living, the All-wise, is leaving thy shores?”

When Constantine, returned to his friends, he was overwhelmed and awestruck by Bahá'u'lláh, handed Nabíl the envelope and gifts and exclaimed: “By God, I have seen the face of the Heavenly Father.” In a state of ecstasy, Fáris Effendi kissed the eyes that had seen Bahá'u'lláh and told Constantine: “Our lot was the fire of separation, yours was the bounty of gazing upon the Beloved of the World.”

The Tablet Bahá'u'lláh revealed for Nabíl and Fáris Effendi had a profound effect on both men, and kindled the fire of Fáris Effendi’s Faith, imbuing him with newfound love and dedication. Upon his release from prison three days later, armed with his newfound zeal and his profound knowledge of Arabic and the Bible, he became a great teacher of the Faith.

Bahá'u'lláh would later say that, while anchored in Alexandria, He had received a mighty letter from which He could inhale the fragrance of holiness, written by one who was detached from the world, and had fully embraced His Cause. Bahá'u'lláh circulated parts of Fáris Effendi’s letter among Persian believers, stating that God had transformed his heart and re-created him entirely.

SOURCE FOR THE LETTER OF FÁRIS EFFENDI

In The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 3, pages 8-9, Adib Taherzadeh has summarized four full paragraphs of Fáris Effendi’s magnificent letter.

SOURCES FOR THE PREVIOUS TWO SECTIONS

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 265-268.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 3: ‘Akká, the Early Years 1868-1877, pages 5-11.

Lady Blomfield, The Chosen Highway, page 65.

DATE

Fáris, the physician who suggests Nabíl and he write letters to be delivered to Bahá'u'lláh mentions that the next day is Friday. On the week of 26 August 1868, the Friday is 28 August 1868, meaning the encounter with Nabíl took place on Thursday 27 August 1868. Source: 1868 Calendar. This is also confirmed in Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 3: ‘Akká, the Early Years 1868-1877, page 5.

View of a quay of Port Said with rowing boats in the foreground. Hippolyte Arnoux, Wikimedia Commons

The exiles reached Port Said the following morning, 29 August 1868, waiting a full day for the summer heat to dissipate, and cast off at midnight, on Sunday 30 August 1868. By this point in the journey, there was almost no food left, several exiles started falling ill because of unsanitary conditions. The ship was filled with an appalling stench, and was so crowded there was no place to lie down or rest.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 268.

Lady Blomfield, The Chosen Highway, pages 65-66.

Myron H. Phelps, The Master in ‘Akká, pages 70-72.

Ships in the Port of Jaffa, 1916. Tel Aviv Municipal Encyclopedia.

The steamer arrived in Jaffa at sunset on 30 August 1868, pausing for a few hours before resuming its journey at midnight towards Haifa.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 268.

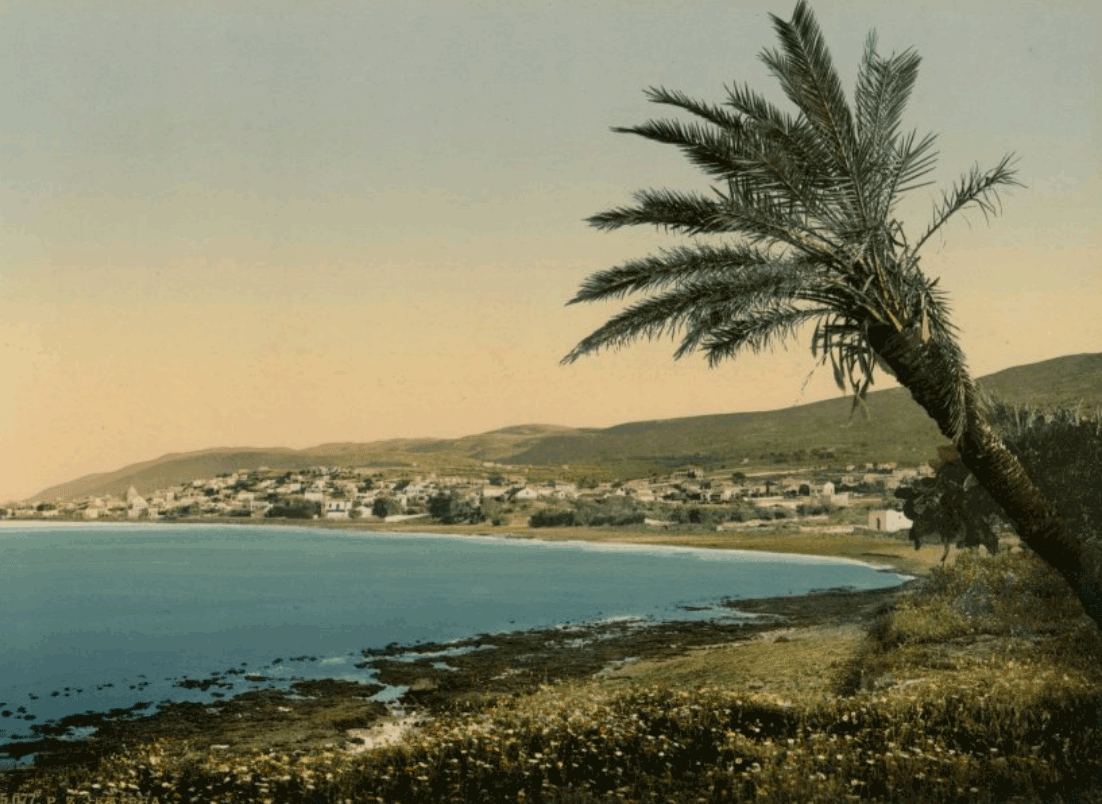

Panorama of Haifa, Photochrome Zurich circa 1895 of the Bay of Haifa. Musée de la Photographie (Online Photography Museum) Exposition: Journey to the Holy Land through the Photochromes from 1880 to 1895.

The battered exiles arrived in Haifa, and were carried ashore in row-boats and chairs. ‘Abdu’l-Ghaffár, one of the four Bahá'ís condemned to go to Cyprus, tried to end his life by flinging himself out to sea, but was revived, and forced to continue his journey. Bahá'u'lláh and His companions only spent a few hours in Haifa as the final preparations were taking place for the journey of Mírzá Yaḥyá, his family (he had several wives and children), his followers, and the four companions of Bahá'u'lláh who were to accompany him, including Mishkín-Qalam. Their separation from the rest of the believers was a moment of great distress for everyone.

At last, after hours spent waiting in the heat of Haifa, the exiles, boarded a sailboat for ‘Akká, their final destination for an utterly miserable journey. Almost every one was now sick, and they sailed on a windless day for eight hours under the scorching sun with no shade. Bahíyyih Khánum would later recall that she had been a healthy young woman until this sea journey, but was never fully well after it.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 269.

Lady Blomfield, The Chosen Highway, page 66.

Myron H. Phelps, The Master in ‘Akká, page 75.

“The arrival of Bahá’u’lláh in ‘Akká marks the opening of the last phase of His forty-year long ministry, the final stage, and indeed the climax, of the banishment in which the whole of that ministry was spent.”

Bahá’u’lláh, The Hidden Words, From the Persian

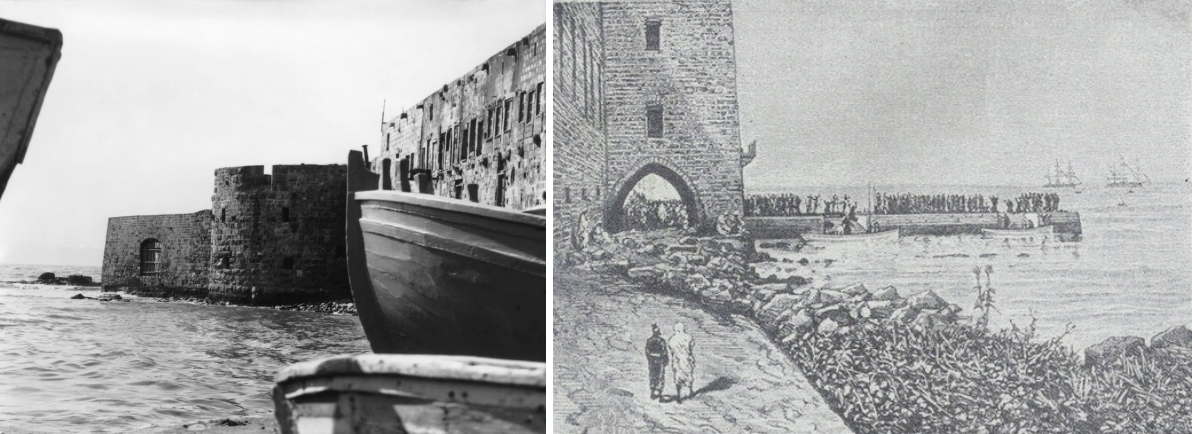

Left: The sea gate where Bahá'u'lláh and His companions entered ‘Akká in 1868, c. 1920. Bahá'í Media Bank. Right: Engraving of the government building in Haifa and the Russian pier, which was built in 1854. Igal Graiver, of the Haifa Historical Society, explains that Baha’u’llah likely walked on that pier to the government building when he stopped in Haifa for a few hours on 31 August 1868. Bahá'í World News Service.

'Akká had no landing stage or dock, only a sea-gate, and passengers had to wade ashore in the shallow sea to land in the city. The Governor of ‘Akká ordered that the 23 women in the party, nearly one-third of all the exiles, be carried ashore on the backs of the men. 'Abdu'l-Bahá categorically refused this order. The women included Navváb, and the Greatest Holy Leaf, the wife and daughter of Bahá'u'lláh, so 'Abdu'l-Bahá was one of the first passengers to wade ashore, He procured a chair and organized the logistics of carrying all the women ashore while they were seated on a chair, in a dignified manner. Through this gesture, 'Abdu'l-Bahá managed to wordlessly convey that, despite their exile, they treated women with respect.

The ship was bound for Cyprus, but Bahá'u'lláh was not allowed to disembark until the last member of His family had landed. They were then counted, and led through the streets of the penal colony.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 271.

Lady Blomfield, The Chosen Highway, page 66.

Myron H. Phelps, The Master in ‘Akká, pages 75-76.

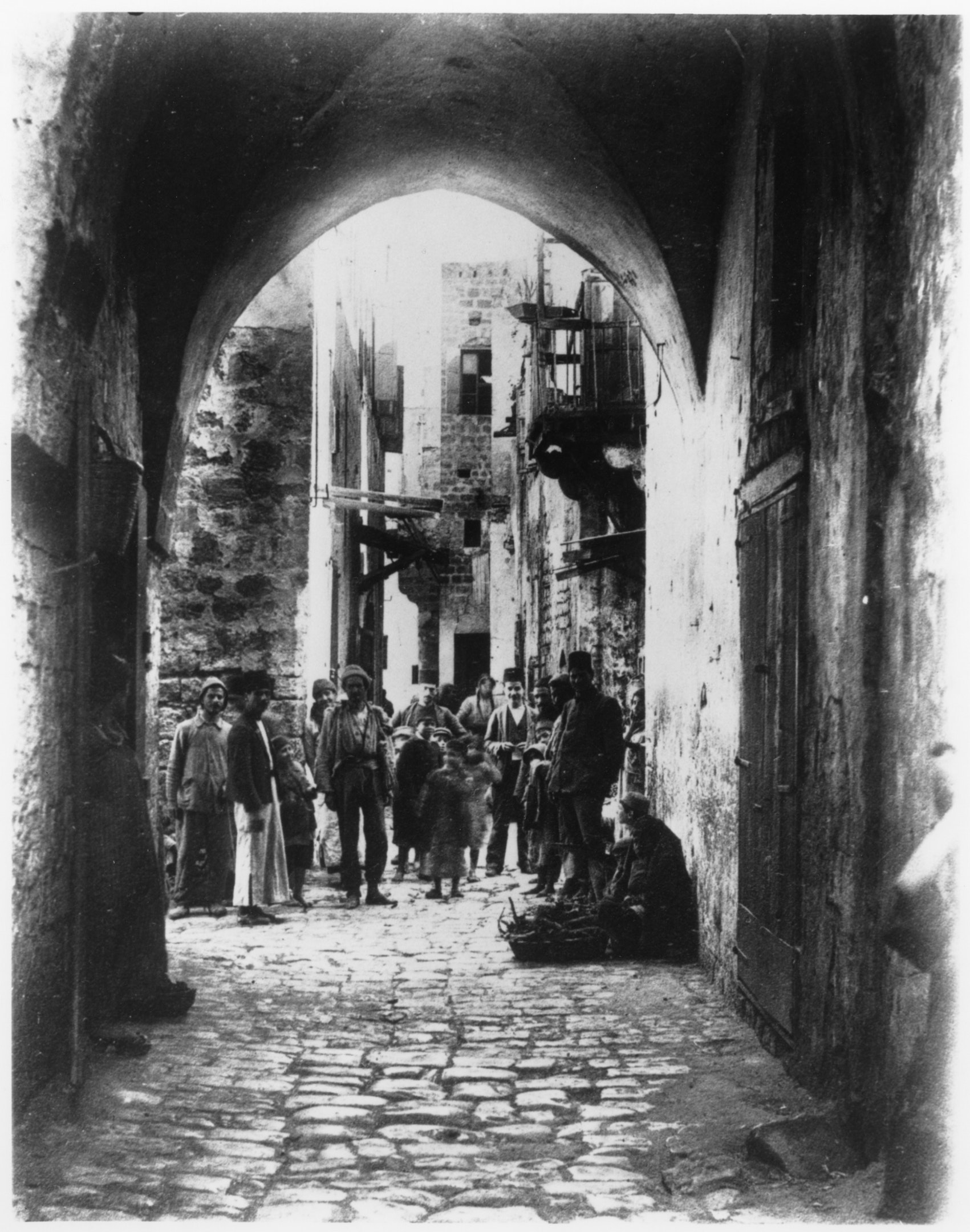

A street scene in ‘Akká, c. 1914. Bahá'í Media Bank.

At the time Bahá'u'lláh and the Bahá'ís arrived in ‘Akká it was a city with a population of close to 9,000 people. A large crowd of ‘Akká residents had assembled to watch the exiles and the “God of the Persians” arrive. Wild rumors had preceded the Bahá'ís’ arrival, and the townspeople had been told the followers of Bahá'u'lláh were infidels, criminals, and sowers of sedition, evil men and women, all deserving to be treated cruelly. The attitude of the crowd was callous, aggressive, and disrespectful, but also curious and confused.

They surrounded the Bahá'ís and spoke to them threateningly and loudly in Arabic, saying that they should be thrown into dungeons and chained, or thrown into the sea. They hurled insults, they swore at them, mocked them, and yelled out curses, which added to the profound misery the exiles were already feeling, sent to the worst penal colony in the Ottoman empire. The people imprisoned in 'Akká were the Ottoman Empire’s most dangerous or most troublesome criminals: murderers, political detainees, troublemakers, and the inhabitants were little better, but two individuals, Khalíl Aḥmad ‘Abdú and ‘Abdu’lláh Ṭu’zih, were able to perceive Bahá'u'lláh’s majesty as they gazed on His countenance.

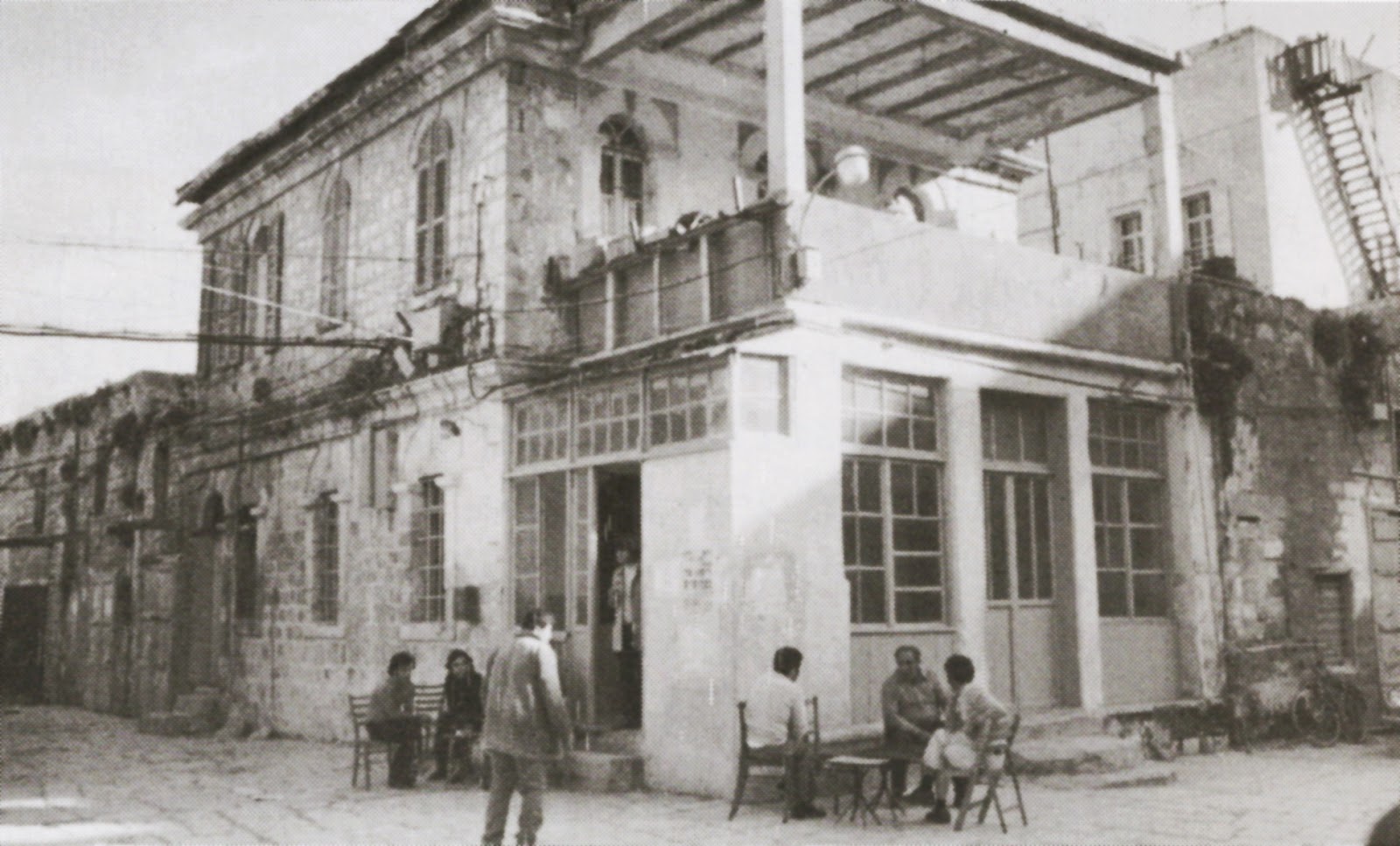

The location of the old police station in the center of 'Akká, where Bahá'u'lláh and the exiles briefly paused before proceeding to the citadel. When the photograph was taken the building had been greatly altered and was serving as a coffee shop. Source: Bahá'í Historical Facts, originally from David Ruhe, Door of Hope, page 23.

Bahá'u'lláh and His party entered ‘Akká through the sea gate, a narrow portal under heavy cannons guarding the entrance of the port, in the late afternoon. The gate itself was made of massive wood with overlapping iron bands, and opened into a courtyard stacked with merchandise, and was located south of the caravanserai known as the Khán-i-'Avámíd.

At first, the authorities tried to confine Bahá'u'lláh and the 67 exiles in the police station pictured above, as 'Abdu'l-Bahá testified: "They first wanted to confine us here, but we did not accept. Then they took us to the barracks." The exiles were then led through the narrow twisting streets of the filthy city, through the busy market streets, past the White Súq (the White Market), and the Mosque of Al-Jazzár, until they finally reached, miserable and exhausted, the strongly-fortified walls of the citadel of ‘Akká which had been repurposed into Ottoman army barracks. They climbed the steep stairs, and were ushered into the prison-fortress through the eastern gateway. The massive door was shut behind them with a great clanging of huge iron bolts. They had entered the Most Great Prison, which was to be their home for the next two years.

When Bahá'u'lláh had arrived in 'Akká, He told ‘Abdu'l-Bahá: "Now I concentrate on My work of writing commands and counsels for the world of the future, to thee I leave the province of talking with and ministering to the people. Servitude is the essence of worship. I have finished with the outer world, henceforth I meet only the disciples."

SOURCES FOR THE PREVIOUS TWO SECTIONS

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 3: ‘Akká, the Early Years 1868-1877, pages 12-16.

Lady Blomfield, The Chosen Highway, pages 64 and 66.

Myron H. Phelps, The Master in ‘Akká, pages 75-76.

Bahá'u'lláh, Lawḥ-i-Sulṭán.

David S. Ruhe, Door of Hope: The Bahá’í Faith in the Holy Land, pages 22-24 and 221.

© Violetta Zein.

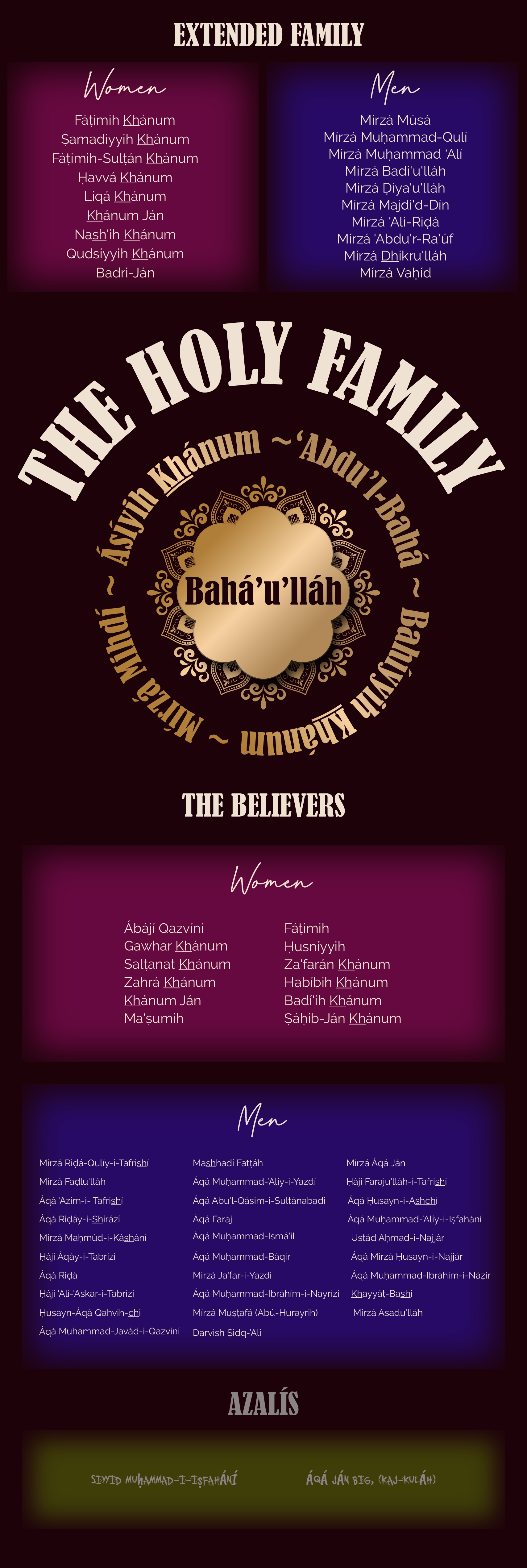

After the exiles who were sent to Cyprus went on their way, 66 exiles remained with Bahá'u'lláh, and entered the Most Great Prison with Him on 31 August 1868. The infographic above is a visual representation of the various groups in this large band of exiles, who, by choice or by force, joined Bahá'u'lláh on His last banishment.

A small, core group consisted of the Holy Family and Bahá'u'lláh’s two faithful brothers, with Bahá'u'lláh’s extended family, His second wife and their children, and the families of both of His brothers, as well as the family of Mírzá Yaḥyá, His brother-in-law, comprising a second group. Bahá'ís, men, women and children, were the largest contingent, and finally, the two Azalís, Siyyid Muḥammad, and Kaj-Kuláh were part of an entirely different universe.

These 66 people entered the Most Great Prison with a Manifestation of God, and though some were unfaithful, and some later broke the Covenant, their names are inscribed in history. To learn more about each and every one of these men and women, please click on the graphic below to download a supplementary PDF about these exiles.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 277-279.

All biographical information completed from sources in Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory and own knowledge, the list is as ordered by Mr. Balyuzi

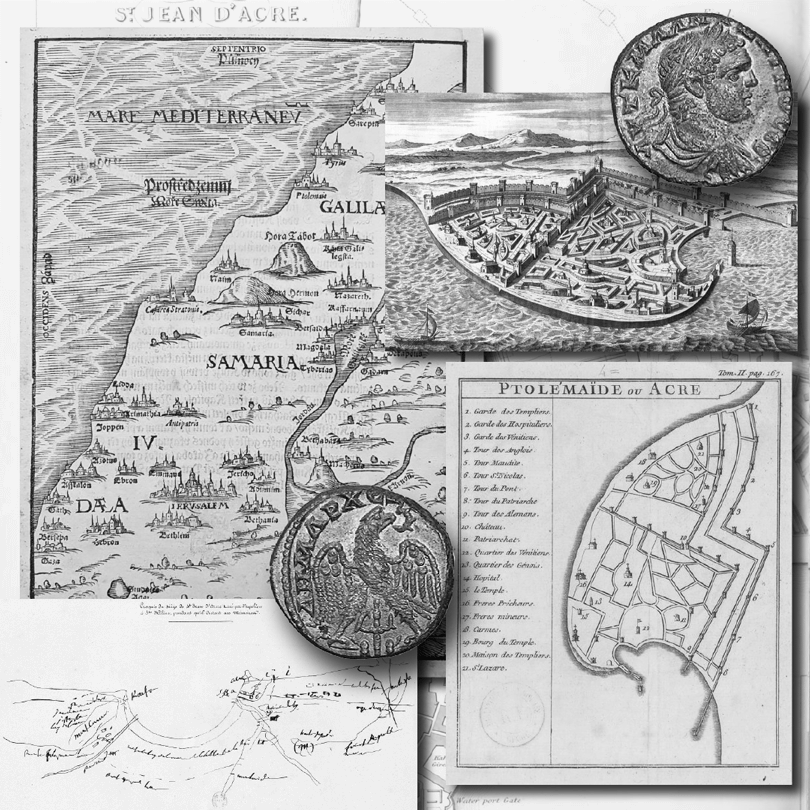

Graphic art collage piece: 'Akká through the ages on a background of an 1840 French map of 'Akká, featuring roman coins from the time 'Akká was called Ptolemais and was located in Phoenicia, and maps from the 15-17th centuries. On the bottom is a hand-drawn sketch of the siege of 'Akká by Napoleon Bonaparte. © Violetta Zein.

In the Roman Empire, 'Akká, was known as Ptolemais, then Saint Jean-d’Acre, or Acre during Crusades, and is one of the oldest continuously-inhabited cities in the world, as well as one of the most fought-over, due to its strategic location, halfway between two cradles of civilization, Egypt and Mesopotamia, on the best natural harbor on the eastern Mediterranean coast. For 4,000 years, 'Akká was occupied by the Egyptians, the Assyrians, the Persians, the Greeks, the Romans, the Arabs, the Crusaders, and finally the Ottomans.

On 31 August 1868, when Bahá'u'lláh finally set foot in 'Akká, its four millennia of strategic regional importance had faded, and ‘Akká was nothing but a prison city for political agitators, and an assortment of criminals. It was an indescribably gloomy town with a detestable climate and foul water, filthy narrow winding streets, lined by ugly houses. It was infested with vermin and fleas, and its air was so filled with rot and stench, that, according to a proverb, a bird flying over ‘Akká would simply drop dead.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

David S. Ruhe, Door of Hope: The Bahá’í Faith in the Holy Land, pages 4, 13-14 and 18-19.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 271-276.

Wikipedia: Acre, Israel.

Wikipedia (French): Saint-Jean-d’Acre.

A gouache and ink painting from between 1539 and 1543 by Sultan Muhammad depicting the ascent of the Prophet Muḥammad to heaven (mir'áj) the second part of His Night Journey after His journey to the Holy Land (Isrá'). Source: Wikimedia Commons.

When Bahá'u'lláh set foot in 'Akká, He set foot on sacred soil. A Manifestation of God had once again graced the Holy Land, promised by God to Abraham, the land that had borne the Revelation of Moses, seen the birth, ministry and crucifixion of Jesus Christ, and was the cradle of Christianity, where Zoroaster had spoken with the prophets of Israel, which the Prophet Muḥammad had visited during His Night-Journey in 621.

There are so many prophecies about Bahá'u'lláh finally arriving in 'Akká and the Holy Land, from Shí’ah traditions, to Old Testament verses, and even prophecies about Bahá'u'lláh Himself before He was exiled. In Ecclesiastes, it is said “For out of prison he cometh to reign,” and Shaykh Ibnu’l-‘Arabí, the celebrated Sunní Ṣúfí thinker prophesied that all the companions of the Herald of the Messiah would be slain “except One, Who shall reach the plain of ‘Akká, the Banquet-Hall of God.”

Shortly before His exile in mid-1868, Bahá'u'lláh affirmed in the Lawḥ-i-Sulṭán, “Erelong shall the exponents of wealth and power banish Us from the land of Adrianople to the city of ‘Akká. But perhaps no testimony about Bahá'u'lláh’s arrival in 'Akká can surpass His own mystical description of the welcome He alone witnessed from the Concourse on High: “Upon Our arrival We were welcomed with banners of light, whereupon the Voice of the Spirit cried out saying: “Soon will all that dwell on earth be enlisted under these banners.””

In the downloadable PDF below, you can read all the prophecies about 'Akká and the Holy Land, from Bahá'u'lláh’s Writings, the Old Testament, Shaykh Ibnu’l-‘Arabí, along with eight prophecies about 'Akká ascribed to Muḥammad, and revealed by Bahá'u'lláh in Epistle to the Son of the Wolf:

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Encyclopedia Britannica: Isrá’.

Wikipedia: Isra and Miraj.

Wikipedia: Ibn Arabi.

Wikipedia: Al-Futuhat al-Makkiyya.

William Sears, Thief in the Night or the Strange Case of the Missing Millennium, PDF pages 123, 124, 128, 154, 159, and 164.

“Know thou, that upon Our arrival at this Spot, We chose to designate it as the ‘Most Great Prison.”

Bahá’u’lláh, The Hidden Words, From the Persian

View of the stairway leading to the ‘Akká prison within the citadel, c. 1901, where the exiles would have entered the barracks. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank.

The citadel of 'Akká functioned as barracks for the Ottoman army. It was high and spacious but filthy, and its only source of drinking water was a pool fetid water in the courtyard, which had already been used for washing. Ten soldiers were posted at the gate to guard the prisoners.

The north-west part of the barracks, where Bahá'u'lláh and the Holy Family were brought, had four or five good rooms, and a bírúní, a reception room with a verandah. The rest of the believers were split across the northwest, north, south and east of the barracks. Siyyid Muḥammad and Kaj-Kuláh were soon moved, at their request to a room looking over the second city gate where they could spy for the Ottoman authorities.

When Bahíyyih Khánum set foot in the Most Great Prison, the heat was so intense, and the air so full of the stench of the latrines, that she fainted from exhaustion. The only water that could be found for her came from a cloth dipped in a pool of water which they squeezed onto her lips to revive her, but the water was so foul that Bahíyyih Khánum heaved and fainted again. In the end, her family could only use the water to refresh her face, and she was finally revived enough to climb the stairs up to their quarters. The Holy Family’s cell was filled with mud to their ankles, preventing anyone from lying down, and what little plaster remained on the ceiling was peeling off.

'Abdu'l-Bahá had already left to help the remainder of the exiles come ashore. When He asked the soldiers to leave the barracks and return with food and water, the soldiers replied: “You cannot put a foot outside this room. If you do, we will kill you,” and refused to allow a servant, escorted by soldiers to go out for provisions in 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s place.

Breastfeeding mothers were starving, and no longer had milk to feed their babies, who could not be calmed. The older children were crying for food and water, and women were fainting. Bahá'u'lláh testified to their inhuman treatment, that first night, saying “all were deprived of either food or drink…No one gave a thought to the plight of these wronged ones. They even begged for water, and were refused.”

Faced with this tragedy, 'Abdu'l-Bahá could not sleep, and spent half the night pacing between the exiles, comforting and soothing them as best He could, while appealing to the soldier’s humanity not to let women and children suffer like this. At midnight, 'Abdu'l-Bahá was able to get a message through to the Governor and they received some water, which they gave to the children, but the rice was inedible: it was filled with grit, and smelled so bad that only those with the most solid stomachs were even able to keep it down. When the exiles unpacked their belongings, they found a few pieces of leftover bread from Gallipoli, and some sugar, which they sent to Bahá'u'lláh, who was very ill.

Bahá'u'lláh returned the bread and sugar with a message: “I command you to take this to the children.” At last, the children were fed, and quieted down.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 275-276 and 320.

Myron H. Phelps, The Master in ‘Akká, page 76-81.

Lady Blomfield, The Chosen Highway, page 66.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 3: ‘Akká, the Early Years 1868-1877, page 16.

Prison of ‘Akká, where Bahá’u’lláh was incarcerated for two years and two months. The two windows farthest right on the second floor show the room that Bahá’u’lláh occupied in the prison. Disclaimer: This is an exquisitely beautiful photograph of a greatly restored Citadel. We must keep in mind this is not the state in which the Most Great Prison was, nor the appearance it had when Bahá'u'lláh was incarcerated there for two years and two months. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank © Bahá'í International Community.

The next day, there was still no food or water, and 'Abdu'l-Bahá sent message after message to the Governor, appealing on behalf of the suffering women and children. The Governor sent water and bread, but the bread was even more inedible than the rice, as if mud had been mixed in with the flour.

Through sheer determinedness, 'Abdu'l-Bahá obtained permission for a servant, escorted by four soldiers, to go into ‘Akká and buy food, with the explicit instructions to not speak to a single person except in bargaining for supplies, or he would be impaled on the soldier’s swords. The exiles had so little money, the poor man wasn’t able to buy much food.

Bahá'u'lláh requested that their prison allowance from the Ottoman government be converted into money, in order to allow them to purchase food, once the Governor agreed, Bahá'u'lláh gave over His allowance to 'Abdu'l-Bahá for the exiles, saying “I will eat bread.”

Later, some officials from ‘Akká came to visit Bahá'u'lláh, who spoke to them with such wisdom and knowledge, that the officials began to see the exiles in a new light, one of them going so far as to say that never before had such pure and sanctified souls set foot in the city of ‘Akká.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 276.

Myron H. Phelps, The Master in ‘Akká, pages 81-82.

Aerial view of the citadel of ‘Akká, taken in May 1972, which gives a good overview of the barracks which the Governor comes to inspect in the story below. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank.

Shortly after the arrival of the exiles, the Governor of ‘Akká visited the barracks for inspection. The Governor was rude and threatened to cut their bread rations, and Áqá Ḥusayn-i-Áshchí, a devoted believer who had accompanied Bahá'u'lláh on His exiles since Baghdád, furious at the Governor’s disrespect of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, berated him for his inedible food. 'Abdu'l-Bahá immediately slapped Áqá Ḥusayn across the face in front of the Governor, and ordered him back to his room.

Trough 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s action, the Governor realized that the exiles had a leader who would not hesitate to discipline His followers, and his attitude changed. He began acting in a more humane way, and replaced the inedible rations of three black and salty bread loaves of bread with money, which the exiles used to buy food.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 3: ‘Akká, the Early Years 1868-1877, pages 17-18.

The Mosque of Al-Jazzár where the Sulṭán's edict was read, seen here against the background of the bay between Haifa and 'Akká. Photographer: Fritz Cohen. Source: Wikimedia Commons., from the National Photo Collection of Israel.

The farmán (edict) of Sulṭán ‘Abdu’l-‘Azíz, dated 26 July 1868, decreed perpetual banishment for Bahá'u'lláh and the Bahá'ís, a life-sentence in prison under the strict confinement and isolation from the inhabitants of 'Akká, with the hope it would eventually exterminate the Faith.

The text of the farmán was read publicly, three days after the exiles’ arrival, on Friday 4 September 1868, in the Mosque of Al-Jazzár. It was meant to serve as a warning to the people of ‘Akká. The message was clear: the Bahá'í exiles were untouchables, enemies of God, thieves, and murderers, who had corrupted the morals of the people, and had tried to overthrow the Sulṭán, and it naturally created an atmosphere of hatred and antagonism towards the exiles.

Bahá'u'lláh’s isolation was so complete, that the followers of Mírzá Yaḥyá in Iṣfahán, spread false rumors that He had drowned. The Bahá'ís in Iṣfahán were so perturbed by this news that they endeavored to find the truth out, and contacted a British Telegraph officer in Julfá to make enquiries for them.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 3: ‘Akká, the Early Years 1868-1877, pages 17-18.

Lady Blomfield, The Chosen Highway, page 66.

Myron H. Phelps, The Master in ‘Akká, page 82.

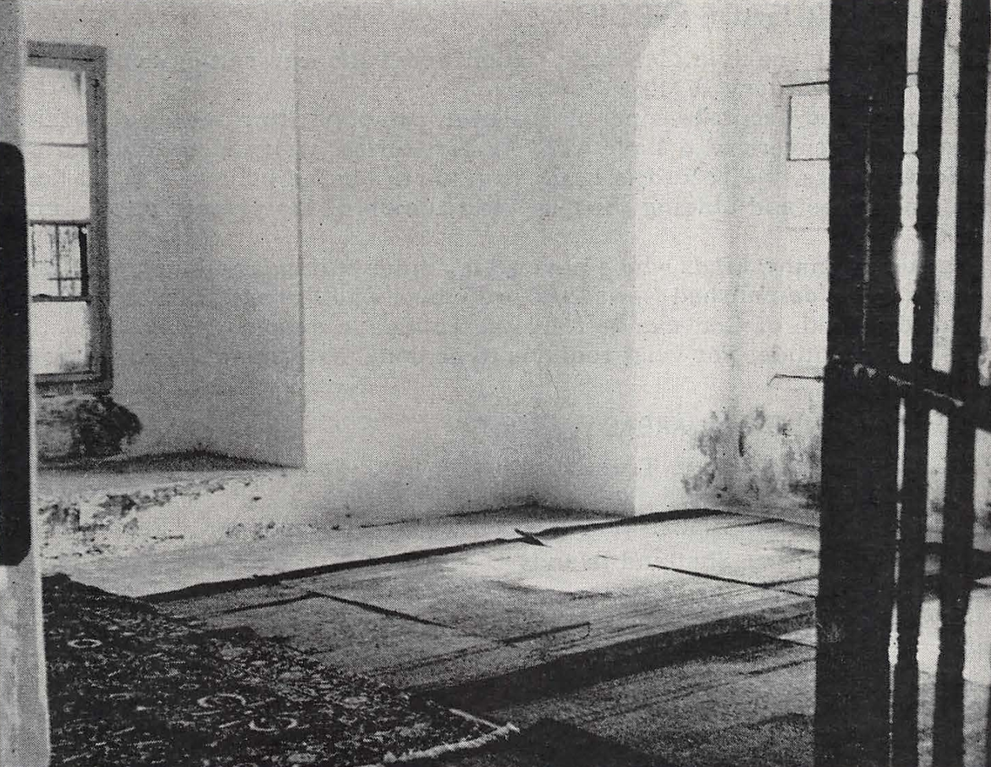

A bleak view through the window in the prison cell of Bahá'u'lláh, as an illustration of the trials He suffered during His first three months in the Most Great Prison, when He was deprived of everything from His freedom, access to His followers, sufficient food and water, medicine, and even dignity when they refused Him access to bathe. Source: David S. Ruhe, Door of Hope: The Bahá’í Faith in the Holy Land, page 28, online accessible at Bahá'u'lláh: A Photographic Narrative of His Life.

Bahá'u'lláh’s incarceration was deeply inhumane and undignified. The Ottoman authorities forbade Him to visit the public bath for three months, and when He required the services of a barber, they were forbidden to speak to each other and closely watched by a guard the entire time.

Bahá'u'lláh, speaking about Himself in the third person, testified to the harsh treatment He endured during His first months in the Most Great Prison: “He hath, during the greater part of His life, been sore-tried in the clutches of His enemies. His sufferings have now reached their culmination in this afflictive Prison, into which His oppressors have so unjustly thrown Him.”

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 285.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 3: ‘Akká, the Early Years 1868-1877, page 18.

Bahá'u'lláh, Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá'u'lláh, N° XXIII

A detail from one of the Templer houses in Haifa. The German inscription over the window “Der Herr is Nahe — 1871” translates to "The Lord is nigh — 1871." Source: The Life of Bahá'u'lláh: A photographic narrative: “The Lord is nigh – 1871”, © Bahá'í World Centre archives, 2007.

For several hundred years leading up to the 19th century, a number of Christian groups took it upon themselves to establish the “perfect” Christian religion in preparation for the Second Coming of Christ, and within a few years, a number of them determined that the Second Coming of Christ would take place around 1844. Christoph Hoffmann founded the German Templer Society in this spiritually-stimulating environment, profoundly convinced that the Second Coming of Christ was imminent and would occur in the Holy Land.

The Templers arrived in Haifa on 30 October 1868, two months to the day after Bahá'u'lláh set foot in the Holy Land, and began building the “Temple” prophesied in Zechariah, a German colony in Haifa, with attractive houses and prophetic stone carvings above their doorways reading “Der Herr ist Nahe” (The Lord is near) bordering the wide avenue leading from the Mediterranean Sea to the foot of Mount Carmel.

Unbeknownst to them, the Templers had fulfilled their mission: they were there in Jerusalem (the Holy Land), having “built the Temple” by their presence and their houses, a mere two months after Bahá'u'lláh, the Second Coming of Christ, had set foot in Haifa, on 31 August 1868, on His way to 'Akká. Unfortunately for them, the Manifestation of God for their age had passed them by, and they had not noticed.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 3: ‘Akká, the Early Years 1868-1877, page 28.

Wikipedia: Templers (Pietist sect).

Wikipedia: German Templer colonies in Palestine.

The courtyard of the barracks showing the northwest corner, where Bahá'u'lláh and His family were quartered, as well as part of the courtyard, all areas which 'Abdu'l-Bahá would have traveled to and from while He was ministering to the sick exiles, photograph taken around 1912. David S. Ruhe, Door of Hope: The Bahá’í Faith in the Holy Land, page 25.

It was a terrible conflagration of situations: the exiles had entered the Most Great Prison weak, hungry and ill from their ordeal on filthy ships, they were underfed and forbidden to bathe for months, the barracks themselves were devoid of any hygiene, and their only drinking water was dirty.

Sometime in the autumn of 1868, all the exiles, and nine out of ten of the guards, fell sick with typhoid, malaria and dysentery. The only exiles who were unaffected were 'Abdu'l-Bahá, His mother, sister, His uncle Mírzá Músá, and two other believers. The rest would say they had never experienced such violent fevers.

The exiles were denied a physician, so 'Abdu'l-Bahá nursed everyone back to health with the two medications He had: quinine and bismuth. 'Abdu'l-Bahá took great care with what He ate and drank, in order to be able to minister to everyone, constantly up and about, tending to all the sick, bringing them patiently back to health, assisted by Mírzá Músá and Áqá Riḍá.

Under 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s loving care, everyone recovered, and only three Bahá'ís died: Áqá Abu'l-Qásim-i-Sulṭánabadi, and two brothers, Áqá Muḥammad-Ismá'íl (Ismá'íl-i-Khayyát) and Áqá Muḥammad-Báqir (Ustád Báqir), who died “locked in each other’s arms,” according Bahá'u'lláh’s own testimony, testifying that never before had two brothers died and entered the realms of glory so united.

Bahá'u'lláh recounts this tragic episode: “Most of Our companions now lie sick in this prison…In the days following Our arrival, two of these servants hastened to the realms above. For an entire day the guards insisted that, until they were paid for the shrouds and burial, those blessed bodies could not be removed, although no one had requested any help from them.”

The barracks guards cruelly prevented the Bahá'ís from preparing the bodies of their dead or seeing to their funeral, and Bahá'u'lláh gave away His only luxury, the small carpet He slept on, to pay for the exorbitant expenses demanded by them to bury the three men. The carpet fetched twice the amount required for a proper burial, but the guards pocketed the money, and threw the bodies of the unwashed, unshrouded bodies of the believers into the ground and covered them with dirt.

Illness was still rampant in the barracks, but no one else died. So many of the exiles had been sick and were now recovering that for four months, a huge cauldron of soup and rice was prepared each night for the recovering exiles, and 'Abdu'l-Bahá would dole out the portions Himself. Until He fell ill, to the consternation and worry of His family and the exiles. 'Abdu'l-Bahá recovered and, gradually, so did everyone else.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Bahá'u'lláh, Lawḥ-i-Ra’ís.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 285 and 287.

David S. Ruhe, Door of Hope: The Bahá’í Faith in the Holy Land, pages 24-26.

Lady Blomfield, The Chosen Highway, page 67.

Myron H. Phelps, The Master in ‘Akká, page 83.

Pen and ink drawing of the Most Great Prison by David S. Ruhe. Source: David S. Ruhe, Door of Hope: The Bahá’í Faith in the Holy Land, page 26.

During his confinement in the barracks, Mírzá Jaf’ár-i-Yazdí became so ill, that the Christian physician. Dr. Butrus (Peter) deemed him a lost cause, and said he could not heal a dead man, exclaiming “I am not Christ!” Surrounded by his family, Mírzá Jaf’ár-i-Yazdí died, and Mírzá Áqá Ján ran to Bahá'u'lláh to tell him the news. Bahá'u'lláh said: “Go, chant the Long Healing Prayer, and he will recover swiftly.”

When 'Abdu'l-Bahá arrived at Mírzá Jaf’ár-i-Yazdí’s bedside to recite the prayer, his body had already started growing cold, but he slowly began to stir, moving his limbs, and an hour later, he was sitting up in bed, laughing and joking. When he recovered, Bahá'u'lláh gave Mírzá Jaf’ár-i-Yazdí the name “Badí’u’l-Ḥayát (Wondrous Life).

To listen to the Long Healing Prayer, recited in Arabic as it would have been at Mírzá Jaf’ár-i-Yazdí's bedside, please click on the graphic below:

'Alí-Akbar Furútan, Stories of Bahá'u'lláh, pages 42-43.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 288.

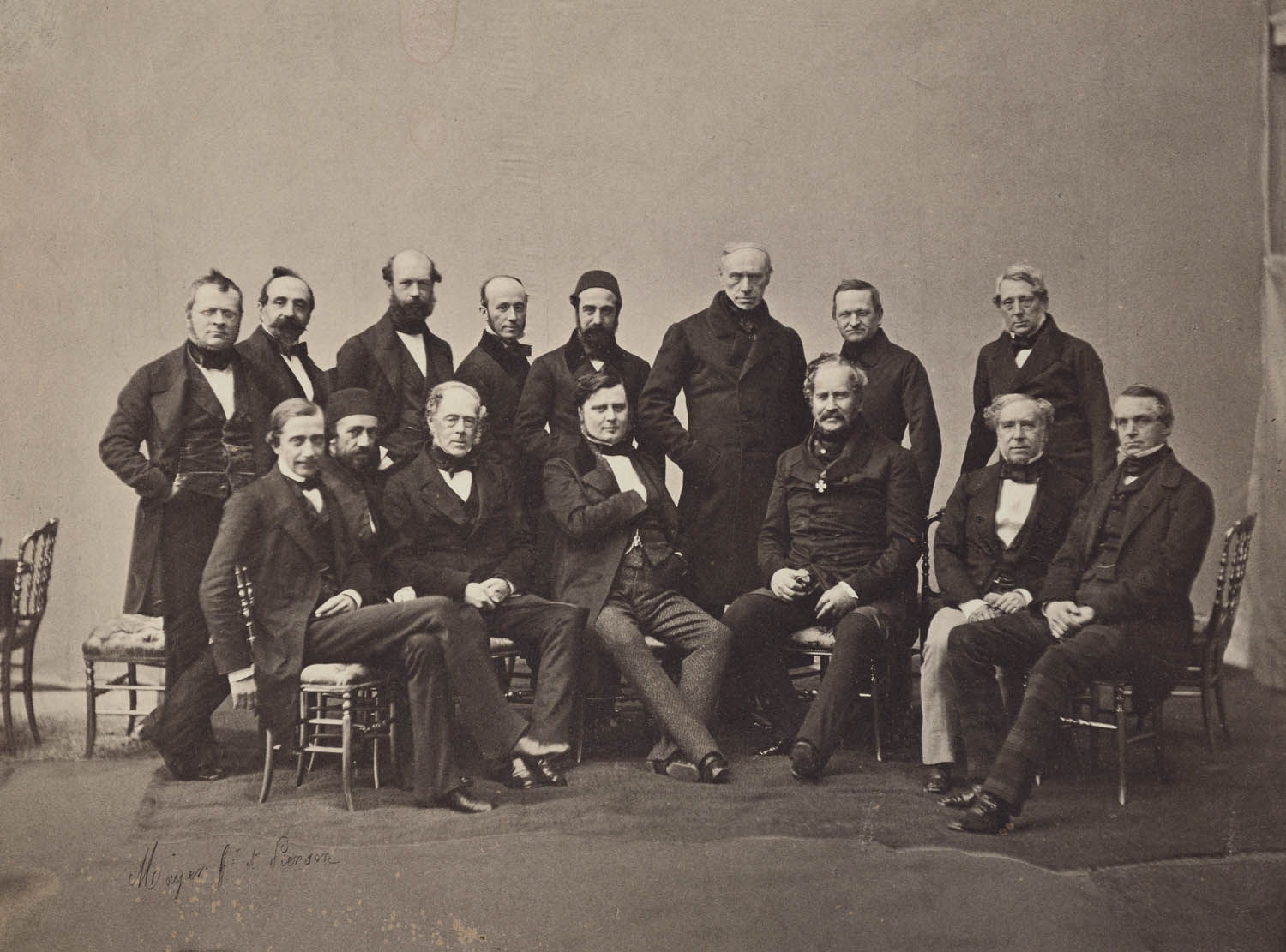

In 1856, diplomatic representatives from the nations of France, Great Britain, Russia, Austria, and Prussia, as well as from the Ottoman Empire and Sardinia-Piedmont attended what would later be called the Congress of Paris. The two main outcomes of the Congress were a pledge by all powers to guarantee the independence of the Ottoman Empire and a restoration of the Russian and Ottoman territories to their pre-Crimean War boundaries. Pictured in the photograph ('Alí Páshá is in the center-left) are, from left to right: Count Cavour, Marquis of Villamarina, Count of Hatzfeldt, Benedetti, Muḥammad Djamil Páshá, Baron of Brunnow, Baron of Manteuffel, Count of Buol, Baron of Hübner, 'Alí Páshá, Count of Clarendon, Count Walewski, Count Orloff, Baron of Bourqueney, Lord Cowley. Source for caption: Wikipedia: Congress of Paris (1856). Source for photograph: Wikimedia Commons, photographer: Mayer Pierson.

Soon after the tragedy of the death of Ismá'íl-i-Khayyát and Ustád Báqir, the two brothers, Bahá'u'lláh revealed the Lawḥ-i-Ra’ís (Tablet to the Chief), a momentous Tablet in Persian and His second epistle, after the Súriy-i-Ra’ís, addressed to ‘Alí Páshá, the Prime Minister of the Sulṭán, a sworn enemy of the Faith, and in large part responsible for Bahá'u'lláh’s fourth exile.

In this Tablet, Bahá'u'lláh rebukes to ‘Alí Páshá for having opposed Him as others opposed Manifestations of God in their day, upbraiding him for his ignorance and immaturity, and for his cruelty in subjecting women, babies and children to the indignity of their imprisonment, recounting their sufferings and deprivations in the barracks: “Ye have plundered and unjustly despoiled a group of people who have never rebelled in your domains, nor disobeyed your government, but rather kept to themselves and engaged day and night in the remembrance of God.”

In this proclamatory Tablet, Bahá'u'lláh calls upon ‘Alí Páshá to embrace the truth of His Cause, and the wholly transformative effect that choice would have on his soul and his being, and proceeds to recount in great detail the story about the puppet show from His childhood told in Part I: Before 1831 : The puppet show.

Bahá'u'lláh also gives ‘Alí Páshá a number of stern warnings: he would eventually be powerless to quench the fire of the Faith, and because he had caused the Spirit of God to lament the cruelties he inflicted on Bahá'u'lláh and His followers, Divine chastisement would rain down on him, God’s wrath would surround him, and he would never be able to make amends: “… the fury of God’s wrath hath so encompassed you that ye shall never take heed… Several times calamities have overtaken you, and yet ye failed utterly to take heed. ”

Partial Inventory ID: BH00269

Bahá'u'lláh, Lawḥ-i-Ra’ís.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 3: ‘Akká, the Early Years 1868-1877, pages 33-36.

The view from the prison cell occupied by Bahá’u’lláh in ‘Akká, early 1900s. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank © Bahá'í International Community.

Bahá'u'lláh spent His first Ninth Day of Riḍván in the Holy Land, 29 April 1869, in the barracks. This was the seventh Riḍván festival of His ministry after His Declaration in Baghdád, and He revealed a Tablet to recount the Holy Day, which is published in Days of Remembrance.

One of the Bahá'ís in the Most Great Prison invited Bahá'u'lláh to honor his room with His presence, and entertained Him with the best food he could provide. The believers present were intoxicated with the joy of Bahá'u'lláh’s presence, and in the Tablet revealed after this occasion, Bahá'u'lláh recounts those special moments: “This is the ninth day of Riḍván, O my God, and on this day one of Thy loved ones hath..invited Him Who is the Manifestation of Thy Self and the Dayspring of Thy glory to leave His room in the prison for another. There he hath spread before Thy presence such of Thy gifts as he hath been able to provide, notwithstanding that the people had plundered all his possessions and the possessions of others among Thy loved ones.”

In this Tablet, Bahá'u'lláh showers His bounties upon His companions in the barracks, those living in ‘Akká and Haifa, and those like Ustád Ismá’íl, attempting to find entry into the city, offering prayers for their steadfastness and unity: “Thou hearest, O Lord, the lamentations of the sincere amongst Thy loved ones who were hindered from meeting Thee during these days,”

Bahá'u'lláh also remembers Nabíl and His companions in Haifa: “Look Thou moreover, O my God, with the glances of the eye of Thy mercy, upon Thy loved ones who are scattered in the land of Ḥá [Haifa].”

Partial Inventory ID: BH00889

Bahá'u'lláh, Days of Remembrance N° 17: Tablet of Riḍván

Source for the story: Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 3: ‘Akká, the Early Years 1868-1877, pages 53-54.

HOW THE DATE WAS DETERMINED

Adib Taherzadeh tells us this story took place during the Ninth day of Riḍván in 1868. The website Time and Date: Solstices and Equinoxes for Acre (1850-1899) was used to determine that the Spring equinox fell on 21 march 1869 (before 1880 the dates of 8 and 9 March were used in place of the dates of 20 and 21 March) According to the document produced at the request of the Universal House of Justice entitled Badí’ Dates for 172 – 221 B.E. (downloadable in PDF format at Bahá'í Library Online), on years when Spring equinox falls on 21 March, the Holy Days for Riḍván fall respectively on 21 and 29 April and 2 May, making the Ninth Day of Riḍván 29 April 1869, in the seventh year of the Bahá'í calendar.

The prison cell of Bahá'u'lláh in the Barracks, in which He revealed all but one of the Tablets to the Kings and ecclesiastes of the world that compose the completed Súriy-i-Haykal, as the Tablet to the Sháh was revealed in Adrianople. Source: Bahá'í Media.

Approximately a year after Bahá'u'lláh arrived in the Most Great Prison, He ushered in the second phase of His Proclamation to the monarchs of the East and West, summoning them to recognize the Day of God and to acknowledge Him as the One promised in the scriptures of their religions. Regarding this extraordinary Proclamation, Bahá'u'lláh testified: “Never since the beginning of the world hath the Message been so openly proclaimed.”

'Abdu'l-Bahá acclaimed these Tablets addressed to the sovereigns of the earth as a “miracle,” and Bahá'u'lláh described them with the following words:

“Each one of them hath been designated by a special name. The first hath been named ‘The Rumbling,’ the second, ‘The Blow,’ the third, ‘The Inevitable,’ the fourth, ‘The Plain,’ the fifth, ‘The Catastrophe,’ and the others, ‘The Stunning Trumpet Blast,’ ‘The Near Event,’ ‘The Great Terror,’ ‘The Trumpet,’ ‘The Bugle,’ and their like, so that all the peoples of the earth may know, of a certainty, and may witness, with outward and inner eyes, that He Who is the Lord of Names hath prevailed, and will continue to prevail, under all conditions, over all men.”

The Summons of the Lord of Hosts, published by the Universal House of Justice in 2002, was the first full, authorized English translation of these important writings and contains five Tablets.

The first Tablet, is the complete Súriy-i-Haykal (Surah of the Temple), considered to be one of Bahá’u’lláh’s most challenging works. Bahá'u'lláh originally revealed the Súriy-i-Haykal in Adrianople, and recast it in 'Akká, effectively recreating it. It is a composite work, comprised of the Súriy-i-Haykal itself which precedes and concludes five Tablets to sovereigns, in the following order: Lawḥ-i-Páp (Tablet to Pope Pius IX), Lawḥ-i-Nápulyún II (Second Tablet to Napoleon III), Lawḥ-i-Malik-i-Rús (Tablet to Czar Alexander II), Lawḥ-i-Malikih (Tablet to Queen Victoria), and Lawḥ-i-Sulṭán (Tablet to Naṣiri'd-Dín Sháh). All these Tablets, with the exception of the Lawḥ-i-Sulṭán, revealed in Adrianople, were revealed in 'Akká.

The four other Tablets included in The Summons of the Lord of Hosts are Súriy-i-Ra’ís (Surah to ‘Alí Páshá), Lawḥ-i-Ra’ís (Tablet to Fu’ád Páshá), Lawḥ-i-Fu’ád (Tablet to Fu’ád Páshá) and Súriy-i-Mulúk (Surah to the Kings).

Shoghi Effendi surveys the contents of Bahá'u'lláh’s majestic Proclamation to the kings and rulers of the world, offering us this magnificent view:

“The magnitude and diversity of the theme, the cogency of the argument, the sublimity and audacity of the language, arrest our attention and astound our minds. Emperors, kings and princes, chancellors and ministers, the Pope himself, priests, monks and philosophers, the exponents of learning, parliamentarians and deputies, the rich ones of the earth, the followers of all religions, and the people of Bahá—all are brought within the purview of the Author of these Messages, and receive, each according to their merits, the counsels and admonitions they deserve. No less amazing is the diversity of the subjects touched upon in these Tablets. The transcendent majesty and unity of an unknowable and unapproachable God is extolled, and the oneness of His Messengers proclaimed and emphasized. The uniqueness, the universality and potentialities of the Bahá’í Faith are stressed, and the purpose and character of the Bábí Revelation unfolded.”

The Universal House of Justice, Introduction to The Summons of the Lord of Hosts.

Wikipedia: Summons of the Lord of Hosts.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Shoghi Effendi, The Promised Day is Come.

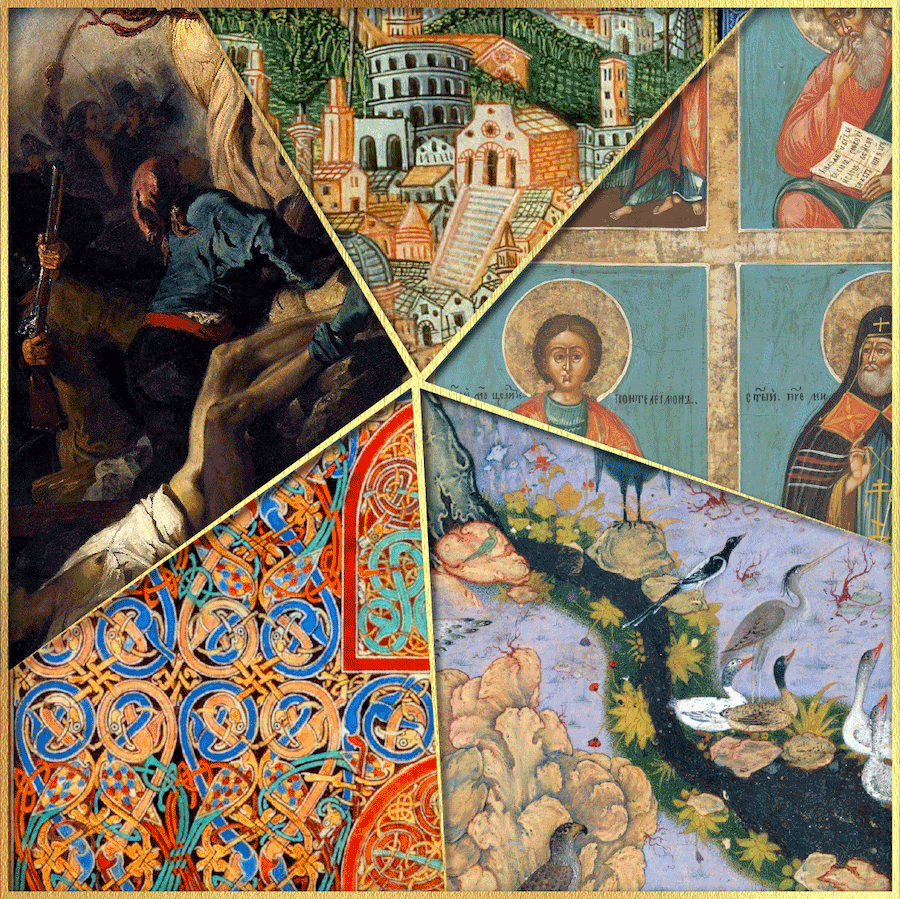

An abstract "haykal" or five-pointed star. The five thin, golden-branched star representing the Súriy-i-Haykal, and each of the five panels representing the five monarchs addressed in the Tablet with a craft from their nation: Top: Pope Pius IX, a Vatican miniature; Left: Napoleon III, Gericault's Liberty Guiding the People; Right: Czar Alexander II, a 19th century Orthodox icon; Bottom left: Queen Victoria, a page of the Book of Kells; Bottom right, Naṣiri'd-Dín Sháh, a Persian miniature. © Violetta Zein.

In the Súriy-i-Haykal, Bahá'u'lláh calls out to the “Temple” 36 times, apostrophizing its individual components, its eyes, ears, tongue, each of its four Arabic letters, and later calling on the Temple of Divine revelation, in effect building a Temple in the Tablet itself, before concluding, after the five Tablets to monarchs: “Thus have We built the Temple with the hands of power and might, could ye but know it. This is the Temple promised unto you in the Book,” creating a direct association between the Temple in the Súriy-i-Haykal, and the one prophesied by Zechariah in the Old Testament.

Bahá'u'lláh instructed that this composite Súriy-i-Haykal be calligraphed in the form of a pentacle, symbolizing the human temple. Shoghi Effendi explained that in this Tablet, it is the Pen of the Most High addressing the Person of Bahá'u'lláh as the Temple and reflecting, like a perfect mirror, the sovereignty, beauty and grandeur to mankind.

Partial Inventory ID: BH00007

Bahá'u'lláh, Súriy-i-Haykal.

Bahá'u'lláh, Introduction to Summons of the Lord of Hosts.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 3: ‘Akká, the Early Years 1868-1877, pages 133-146.

Wikipedia: Book of Zechariah.

John Walbridge, Tablet of the Temple (Suratu'l-Haykal).

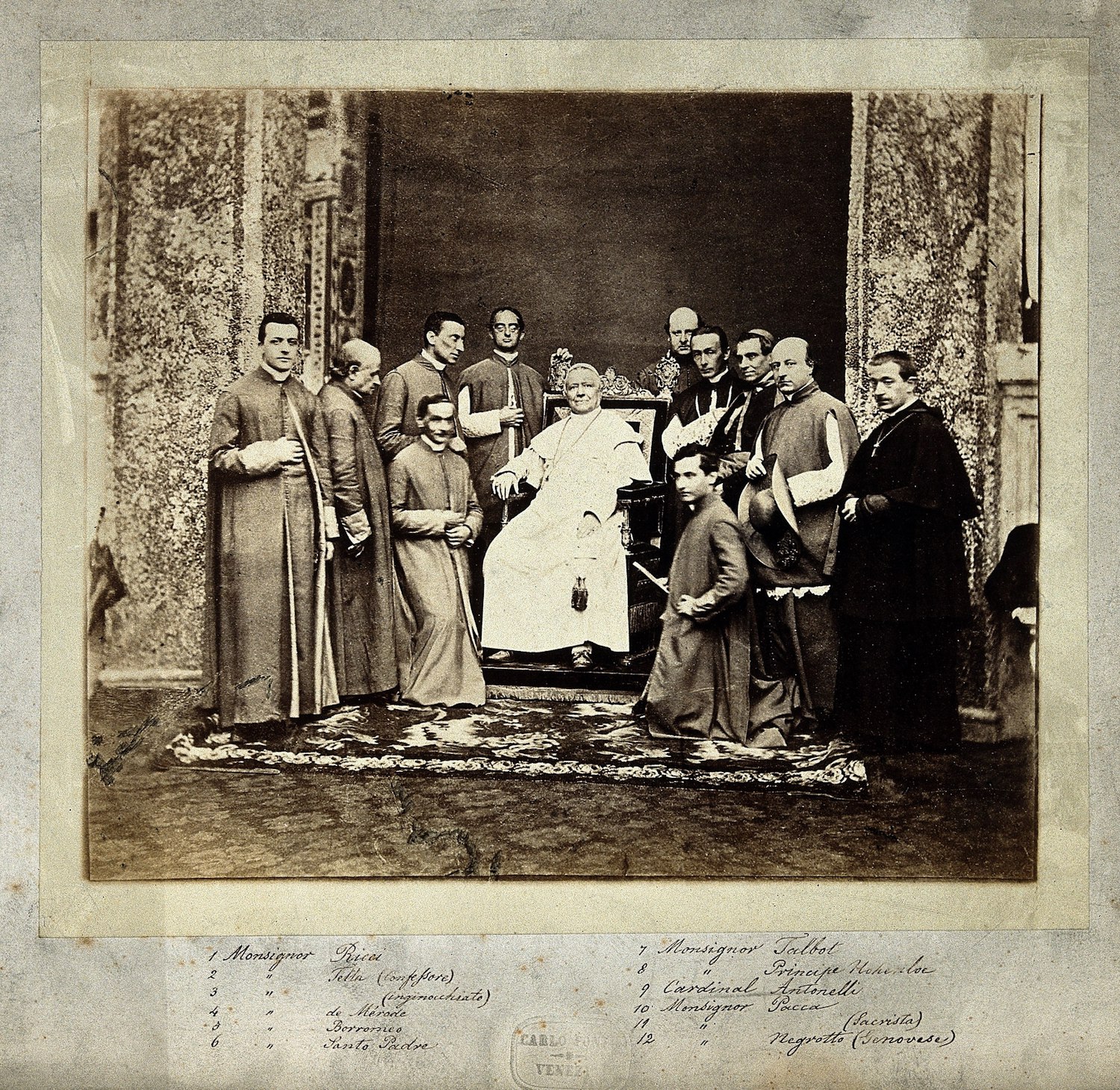

Pope Pius IX and cardinals, members of the Papal court: Monsignor Ricci, Monsignor Tella (confessore), Monsignor [name lacking] (inginocchiato), Monsignor de Mérode, Monsignor Borromeo, Monsignor Santo Padre, Monsignor Talbot, Monsignor Principe Hohenloe [sic], Cardinal Antonelli, Monsignor Pacca, Monsignor [name lacking] (Sacrista), Monsignor Negretto (Genovese). Source: Wikimedia Commons.

In His Tablet to Pope Plus IX, Bahá'u'lláh identifies Himself to the head of the Catholic church, as the promised return of Christ in the Glory of the Father. Bahá'u'lláh addresses the Pope with divine authority: “O Pope! Rend the veils asunder. He Who is the Lord of Lords is come overshadowed with clouds, and the decree hath been fulfilled by God, the Almighty, the Unrestrained...He, verily, hath again come down from Heaven even as He came down from it the first time. Beware that thou dispute not with Him even as the Pharisees disputed with Him (Jesus) without a clear token or proof...”

A few short months after Bahá'u'lláh revealed this Tablet to Pope Pius IX, King Victor Emmanuel I of Italy went to war with the Vatican and seized it. The Pope refused to accept the situation, and excommunicated those who had invaded, denounced the Italian King, but all this had been anticipated by Bahá'u'lláh, and the Pope had only brought it on himself. His last years were filled with crippling physical pain, and mental anguish and sorrow on seeing his Faith outraged in the heart of Rome.

Partial Inventory ID: BH00347

Bahá'u'lláh, Tablet to Pope Pius IX.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 3: ‘Akká, the Early Years 1868-1877, pages 116-118.

Painting depicting Bismarck et Napoléon III speaking together in Donchéry, France after Napoleon's surrender on 2 Septembre 1870 following the Battle of Sedan, approximately a year after Bahá'u'lláh's prophetic Tablet to the Emperor, warning of his demise. Artist: Wilhelm Camphausen. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Napoleon III received Bahá'u'lláh’s first Tablet, revealed in a mild tone, with disdain and discourtesy. Bahá'u'lláh’s second Tablet to the French emperor was filled with a tone of authority: “O King of Paris! Tell the priests to ring the bells no longer. By God, the True One! The Most Mighty Bell hath appeared in the form of Him Who is the Most Great Name, and the fingers of the Will of Thy Lord, the Most Exalted, the Most High, toll it out in the heaven of Immortality in His name, the All-Glorious.”

Bahá'u'lláh rebukes Napoleon III for be insincere in his words and thoughts, and prophesies that before long, “the world and all that thou possessest will perish, and the kingdom will remain unto God,” but still Bahá'u'lláh counsels the Emperor “not to conduct thine affairs according to the dictates of thy desires.”

Bahá'u'lláh’s prophecies were fulfilled less than a year later at the Battle of Sedan in September 1870, which sealed Napoleon’s fate: his army was destroyed, his empire collapsed, and the Republic proclaimed.

Partial Inventory ID: BH00259

Bahá'u'lláh, Second Tablet to Napoleon III.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 3: ‘Akká, the Early Years 1868-1877, pages 110-115.

Myron H. Phelps, The Master in ‘Akká, page 87.

Wikipedia: Battle of Sedan.

A seated portrait of Czar Alexander II, Emperor of Russia, taken between 1870 and 1886. Photographer: Levitskii, St. Petersburg. Source: Library of Congress.

In His Tablet to Czar Alexander II, Bahá'u'lláh summons him to His Cause in momentous terms: “O Czar of Russia! Incline thine ear unto the voice of God, the King, the Holy, and turn thou unto Paradise…Beware lest thy sovereignty withhold thee from Him Who is the Supreme Sovereign. He, verily, is come with His Kingdom…Arise thou amongst men in the name of this all-compelling Cause, and summon, then, the nations unto God, the Exalted, the Great.”

Bahá'u'lláh describes to the Czar the unique and unparalleled nature of His Revelation: “Say: This is an Announcement whereat the hearts of the Prophets and Messengers have rejoiced. This is the One Whom the heart of the world remembereth and is promised in the Books of God, the Mighty, the All-Wise.”

Bahá'u'lláh’s exhortation fell on deaf ears. Czar Alexander II was assassinated a little more than ten years later.

Partial Inventory ID: BH01042

Bahá'u'lláh, Tablet to Czar Alexander II.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 3: ‘Akká, the Early Years 1868-1877, pages 118-123.

An 1880 chromolithograph print of a portrait of Queen Victoria. Source: Library of Congress.

In the Lawḥ-i-Malikih, Bahá'u'lláh proclaims the coming of the Lord in His great glory and summons her to His Cause, but also dispenses counsels and exhortations, commending her on abolishing slave trade and ruling a government representative of her people. In a visionary address about the Members of British Parliament, Bahá'u'lláh extends their mandates to the people of the earth, not just to the people of the British Empire: “It behoveth them however, to be trustworthy among His servants, and to regard themselves as the representatives of all that dwell on earth.”

Partial Inventory ID: BH00662

Bahá'u'lláh, Tablet to Queen Victoria.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 3: ‘Akká, the Early Years 1868-1877, pages 123-125.

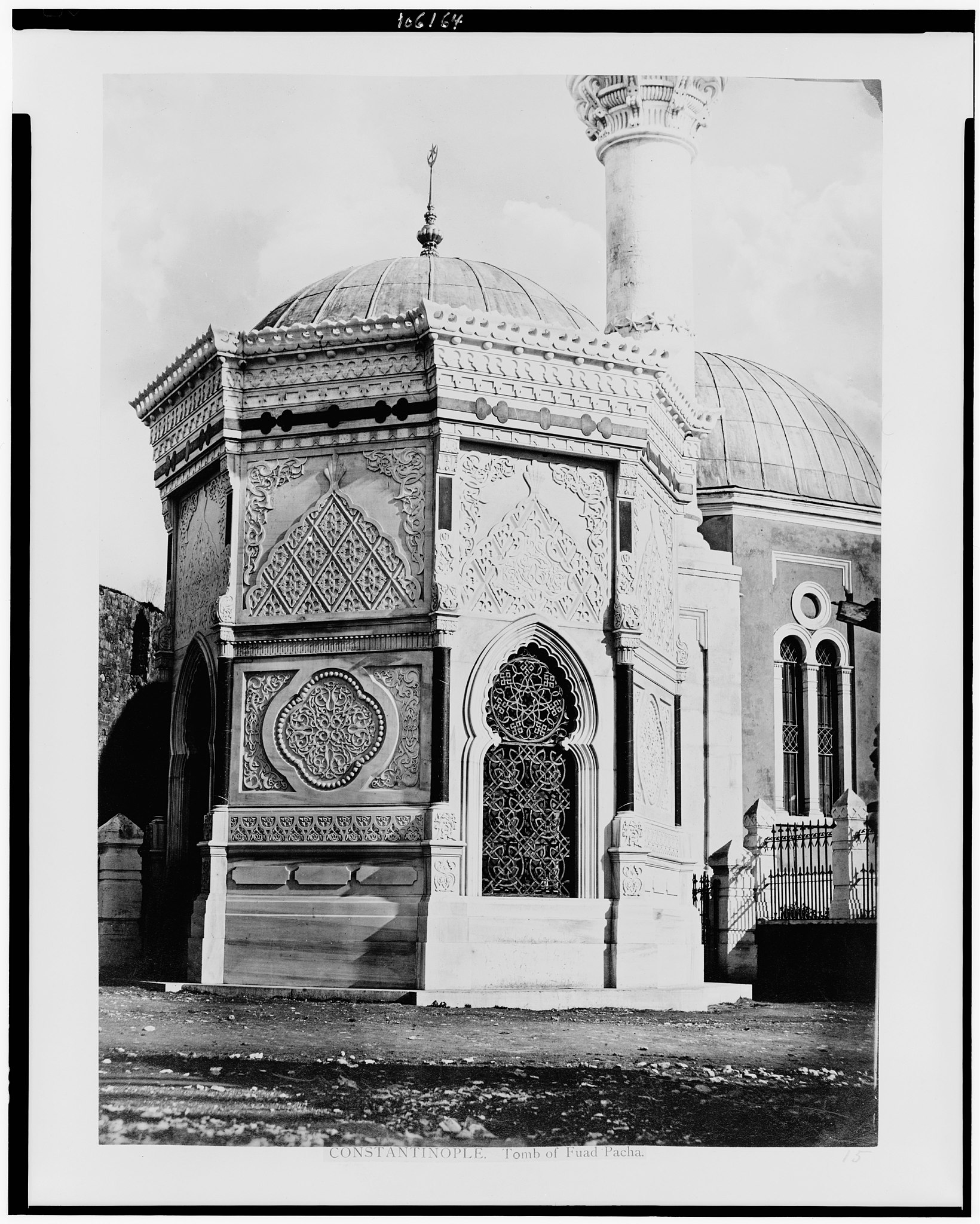

The tomb of Fu'ád Páshá in Constantinople. The former Prime Minister (Grand Vizir) and Minister of Foreign Affairs for Sulṭán 'Abdu'l-Azíz died in Nice, France in 1869. Source: Wikimedia Commons, originally from the Library of Congress.

The Lawh-i-Fu'ád was addressed to Shaykh Káẓim-i-Samandar of Qazvín, one of the 19 Apostles of Bahá'u'lláh, but also addresses the disgraced Fu'ád Páshá, who was dismissed from his post and died in Nice, France. In the Lawḥ-i-Fu’ád, Bahá'u'lláh rebukes the deceased Ottoman Minister, declaring God has taken his life in punishment and describing in powerful language the agony of his soul as it faces the wrath of God.

Bahá'u'lláh prophetically foreshadows the downfall of 'Álí Páshá and Sulṭán ‘Abdu’l-Azíz: “Soon will We dismiss the one ['Álí Páshá] who was like unto him [Fu'ád Páshá], and will lay hold on their Chief who ruleth the land [Sulṭán ‘Abdu’l-Azíz], and I, verily, am the Almighty, the All-Compelling.”

Álí Páshá was disgracefully dismissed from his post and died two years later. The process of disintegration of the Ottoman empire had spun into motion, which would lead to the Sulṭán’s dethronement and assassination, in 1896. Bahá'u'lláh’s dire prophecies were the subject of frequent speculation among Bahá'ís at the time, some even making their adherence to the Faith conditional upon their fulfillment.

Partial Inventory ID: BH01494

Bahá'u'lláh, Lawḥ-i-Fu’ád.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 3: ‘Akká, the Early Years 1868-1877, pages 87-107

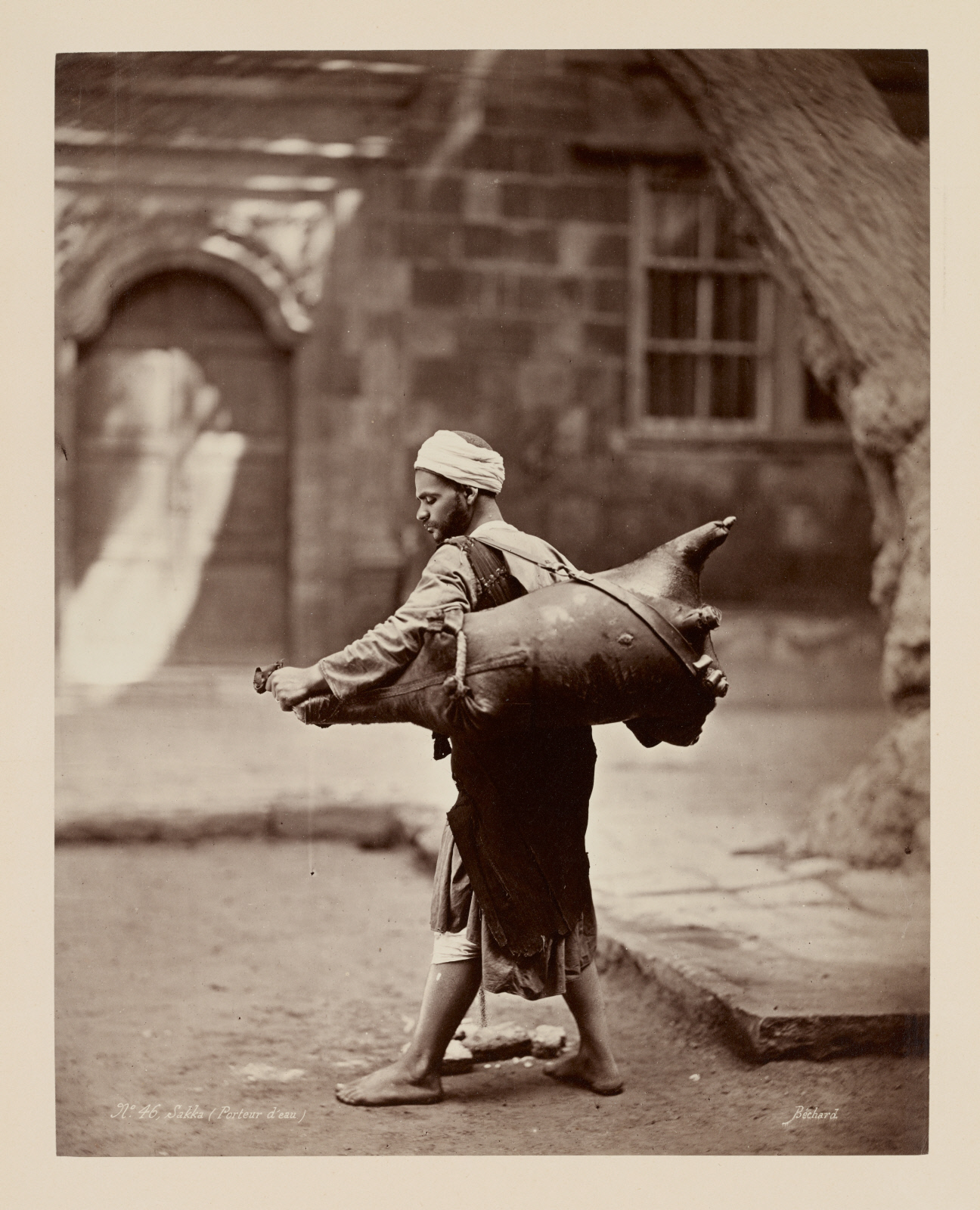

Picture of Mírzá Áqá Buzurg-Níshapúrí titled Badí', two years before these events take place. He is pictured here at the age of 15, in the Persian empire (most probably Khúrasán, where he was from) sometime in the 1860s. Originally printed on page 372 of Bahá'u'lláh, King of Glory by H.M. Balyuzi (1980). Source: Bahá'í Media, description from Wikipedia.