Written and illustrated by Violetta Zein

This part covers the life of Shoghi Effendi from the age of 33 in 1930 to the age of 35 in 1932.

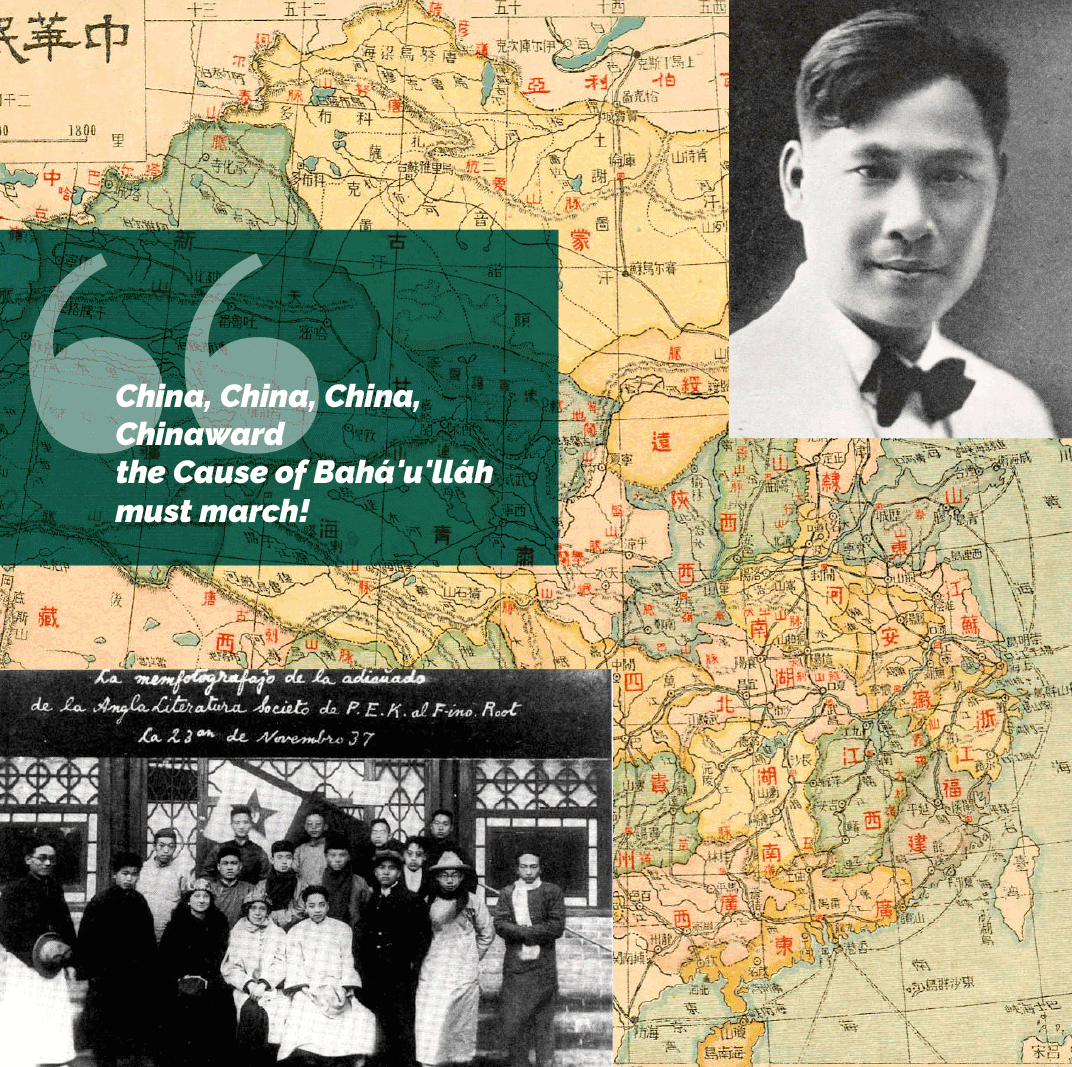

'Abdu'l-Bahá had such a deep, profound love for China that he wrote a Tablet about it, published in Star of the West, where he expounds on the importance of China and the Chinese people, a Tablet which informed the Guardian’s priority to send eminent travel teachers like future Hands of the Cause Martha Root and Keith Ransom-Kehler on travel teaching trips to China:

China, China, China, Chinaward the Cause of Bahá'u'lláh must march! Where is that holy sanctified Baha’i to become the teacher of China! China has most great capability. The Chinese people are most simple hearted and truth seeking. The Baha’i teacher of the Chinese people must first be imbued with their spirit; know their sacred literature; study their national customs and speak to them from their own standpoint, and their own terminologies. He must entertain no thought of his own, but ever think of their spiritual welfare. In China one can teach many souls and train and educate such divine personages each one of whom may become the bright candle of the world of humanity. Truly, I say they are free from deceit and hypocrisies and are prompted with ideal motives. “Had I been feeling well, I would have taken a journey to China myself! China is the country of the future. I hope the right kind of teacher will be inspired to go to that vast empire to lay the foundation of the Kingdom of God, to promote the principles of divine civilization, to unfurl the banner of the Cause of Baha’u’llah, and to invite the people to the Banquet of the Lord!”

Martha Root met Ling Liu and Chan Liu, a Chinese sister and brother in the United States, and they became Bahá'ís through her while they were pursuing their university studies in the United States. Chan Liu was educated at the College of Wooster and at Wellesley College got a Master in education at Columbia University and was one of the earliest Chinese women to attend graduate school.

Keith Ransom-Kehler arrived in Shanghai on 12 August 1931, and was welcomed by the resident Bahá'ís with huge bouquets of flowers. She gave interviews and attended an evening of traditional Chinese theater, then on 15 August, she sailed south along the rugged coast of the China See and docked in Kowloon, Hong Kong, greeted by Ling Liu and Chan Liu, who now each headed a university. Ling Liu was the first dean of the Women's College of Lingnan University, and Chan Liu was the president of the College of Agriculture at Sun Yat-sen University.

The next day, August 16, the Liu family took Keith to see the Flower Pagoda. At one point during her stay, Chan Lui shyly asked if Shoghi Effendi had ever spoken about China, and Keith was absolutely thrilled to answer positively: Shoghi Effendi spoke often of the vast importance of the Bahá'í teaching work in China, and of how pleased he had been when Martha Root visited China for 2 months from 22 August 1930 to 22 October 1930. Martha Root’s first visit to China had lasted almost a year from June 1923 to March 1924.

The Guardian loved China with a passion equal to his Grandfather’s, and mentioned the country frequently in his letters and writings:

In The Unfoldment of World Civilization, a letter written on 11 March 1936, the Guardian listed China poetically as one of the farthest reaches of the Faith: “From Iceland to Tasmania, from Vancouver to the China Sea spreads the radiance and extend the ramifications of this world-enfolding System.”

In God Passes By in 1944, he listed China as a place to which the immortal Martha Root had traveled and had visited nearly 100 universities, colleges and schools and had interviewed the Chinese Foreign Minister and Minister of Education, as well as one of the languages in which Bahá'í literature had been translated.

On 29 April 1953, the Guardian listed China as one of the second objectives for consolidation of the Faith during the Ten Year Crusade.

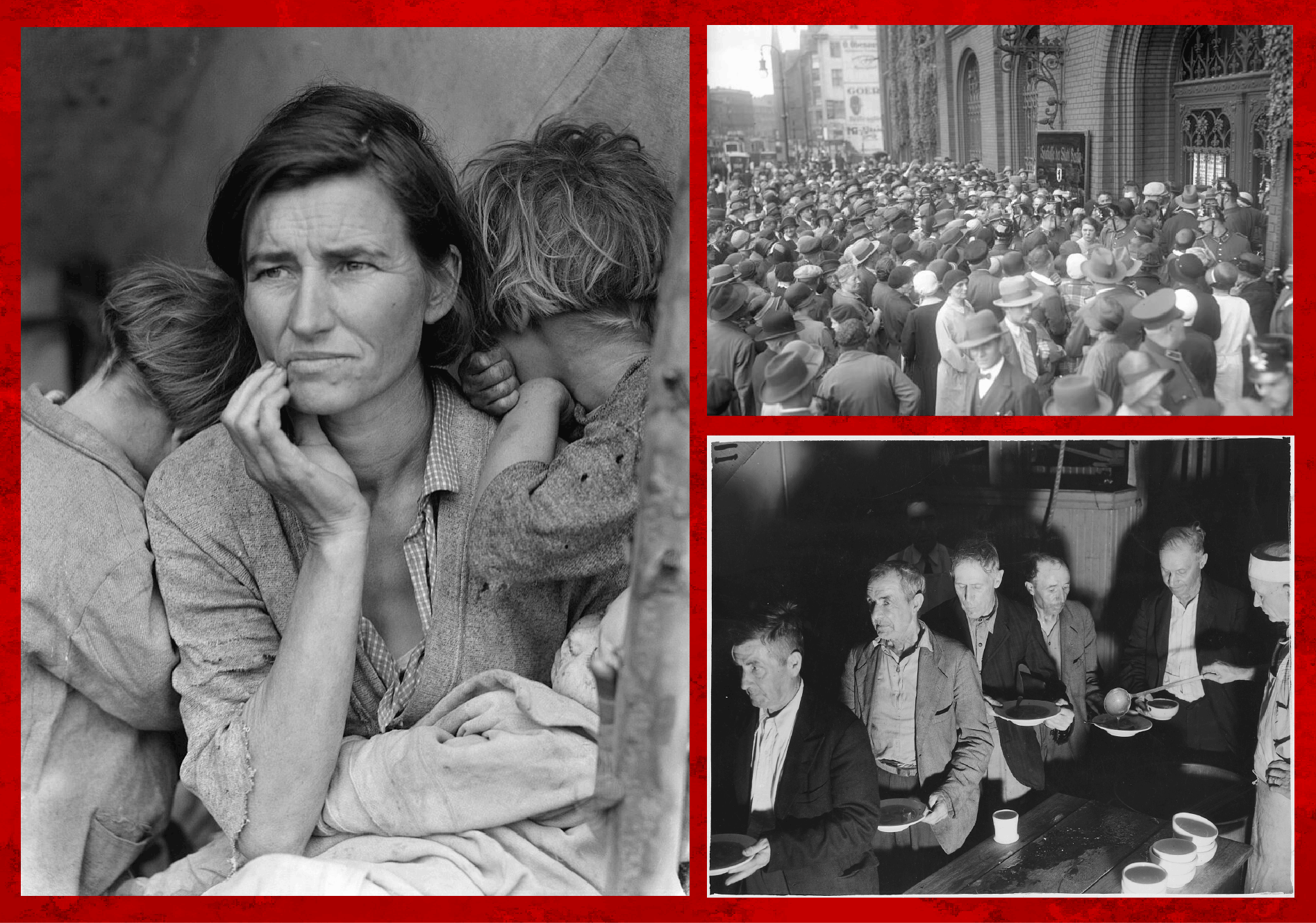

Some of the political and economic events and crises that shook the world in 1930 and 1931: The Great Depression was a global economic downturn that began in 1929 and continued into the early 1930s, affecting economies worldwide: unemployment soared, industrial production declined, and international trade contracted. Photograph on the left: The Dust Bowl was an ecological disaster that occurred in the Great Plains of the United States during the 1930s: it caused widespread soil erosion and dust storms and greatly exacerbated the crisis caused by the Great Depression in America (Photo of migrant mother. Source: Wikimedia Commons. Top right photograph: Millions depended on soup kitchens to survive. Source: Wikimedia Commons. The crisis was global. Bottom right photograph: In July 1931, there was a banking crisis in Germany caused by the collapse of the Darmstädter und Nationalbank, which paved the way for Hitler and his Nazi party to power (Bank run at the Sparkasse on Mühlendamm, Berlin, 13 July 1931: Wikimedia Commons).

On 28 November 1931, the tenth anniversary of the Ascension of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, Shoghi Effendi wrote a letter called The Goal of a New World Order, addressed to the worldwide Bahá’í community.

Shoghi Effendi wrote The Goal of a New World Order because he felt it timely that the public learn and understand the attitude of the Bahá'í Faith towards all the problems of the world, both economic and political, in order for them to understand the real aim of Bahá'u'lláh’s Teachings.

In The Goal of a New World Order, the Guardian carefully explains that humanity as a whole—both individuals in their moral conduct and countries—has strayed so far and fallen so low that it is beyond saving.

There was no man-made fix.

Shoghi Effendi is so adamant about this point, that he outlines what can no longer save humanity, and it is a very, very comprehensive list:

No diplomacy.

No economic theory.

No set of principles.

No commitment to mutual tolerance.

No organized international cooperation.

There is only one hope of a humanity that does not yet know it is dying: Bahá'u'lláh’s simple yet unbelievably powerful promise for a Divine Civilization, with its end goal a Divinely-appointed New World Order, and that humanity’s unqualified acceptance of Bahá'u'lláh’s solution is its only hope.

In this letter, the Guardian offers a series of excerpts from the Writings of Bahá'u'lláh and 'Abdu'l-Bahá that amply demonstrate the urgency for humanity to let go of nationalism and embrace an international world government at the executive, legislative and judicial levels, the only solution to divisive ethnocentrism, and the beginning of world citizenship. Shoghi Effendi clarifies that the Oneness of Mankind—the central principle of the Bahá'í Faith—is a completely, organically new creation.

Shoghi Effendi also emphasizes the duty of every individual believer to propagate the message of Bahá'u'lláh. In a letter written on his behalf in January 1932, Shoghi Effendi encouraged Bahá'ís to share The Goal of a New World Order with the general public, but to observe wisdom:

… the friends should spread the message it conveys to the public. It should undoubtedly be done in a very judicious way lest the people think that we have entered the arena of politics with rather drastic programmes of reform. But we should at the same time show the lead that the teachings take towards the realization of the international ideal.

“Let there be no mistake.” Background photo: Joakim Nådell on Unsplash.

Here is a beautiful eye-opening excerpt from The Goal of a New World Order on the central tenet of our Faith, the Oneness of Humanity:

Let there be no mistake. The principle of the Oneness of Mankind – the pivot round which all the teachings of Bahá’u’lláh revolve – is no mere outburst of ignorant emotionalism or an expression of vague and pious hope. Its appeal is not to be merely identified with a reawakening of the spirit of brotherhood and good-will among men, nor does it aim solely at the fostering of harmonious cooperation among individual peoples and nations. Its implications are deeper, its claims greater than any which the Prophets of old were allowed to advance. Its message is applicable not only to the individual, but concerns itself primarily with the nature of those essential relationships that must bind all the states and nations as members of one human family. It does not constitute merely the enunciation of an ideal, but stands inseparably associated with an institution adequate to embody its truth, demonstrate its validity, and perpetuate its influence. It implies an organic change in the structure of present-day society, a change such as the world has not yet experienced. It constitutes a challenge, at once bold and universal, to outworn shibboleths of national creeds – creeds that have had their day and which must, in the ordinary course of events as shaped and controlled by Providence, give way to a new gospel, fundamentally different from, and infinitely superior to, what the world has already conceived. It calls for no less than the reconstruction and the demilitarization of the whole civilized world – a world organically unified in all the essential aspects of its life, its political machinery, its spiritual aspiration, its trade and finance, its script and language, and yet infinite in the diversity of the national characteristics of its federated units.

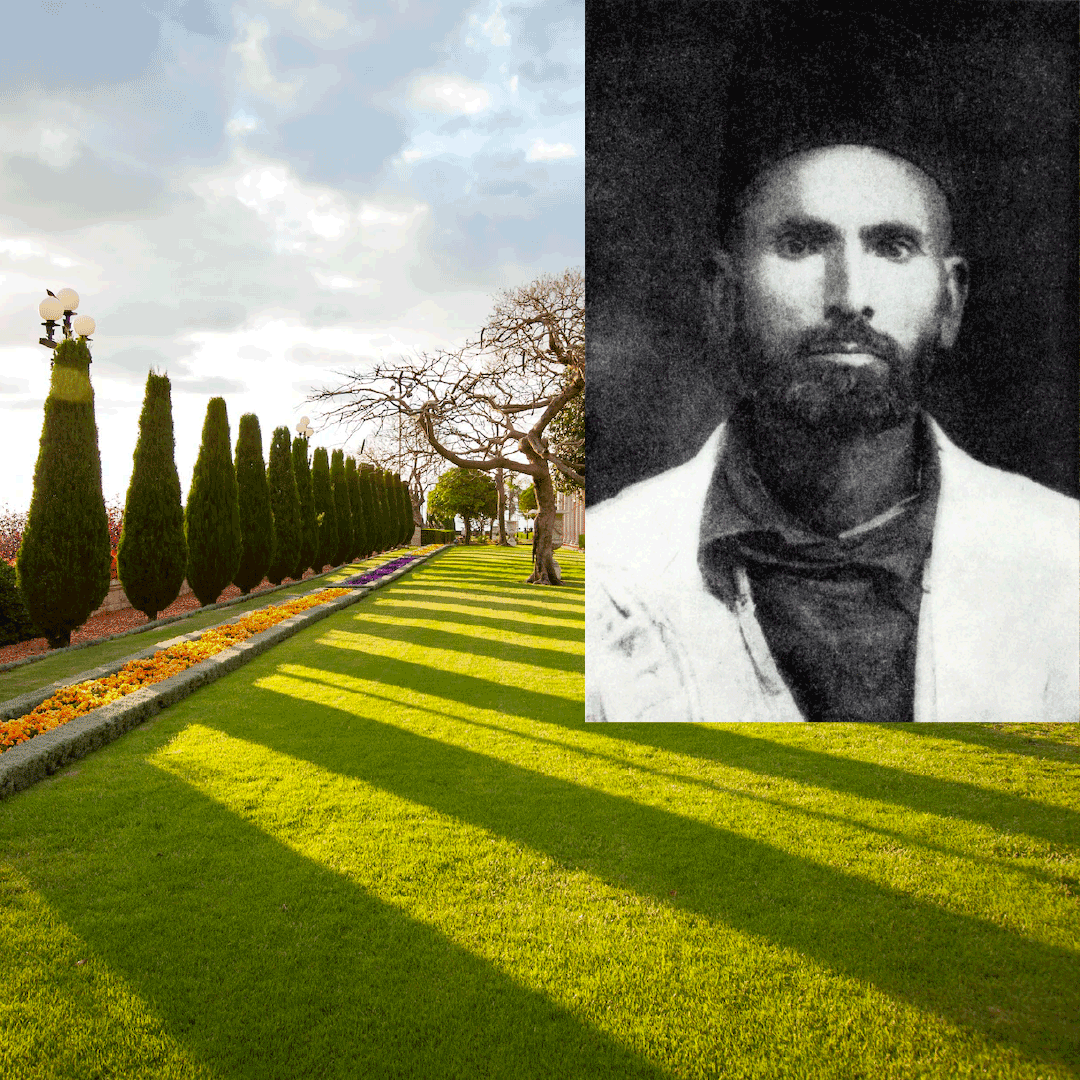

Abu’l-Qásim Khurásání (Bahaipedia) on a background of the gardens around the Shrine of the Báb (Bahá'í Media Bank), for which he was the gardener, along with being the custodian of the Shrine and the International Bahá'í Archives

Abu’l-Qásim Khurásání was a very talented gardener, and when he left the gardens of the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh to begin working on the green spaces around the Shrine of the Báb, the gardens showed their appreciation. Abu’l-Qásim had a green thumb. He was also the Custodian of the International Bahá'í Archives, which, at the time, were in three rooms at the back of the Shrine of the Báb.

When he had been Custodian at the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh, Abu’l-Qásim never left the Shrine to sleep in a cozy bed, but kept watch. He kept the same habit when he became Custodian of the Shrine of the Báb, no doubt because of the priceless relics in the Archives. On 26 February 1932, Áqá suddenly and unexpectedly died near the Shrine of the Báb.

The Guardian was a deeply sensitive and loyal friend, and was so deeply grieved by his friend’s passing that he did not eat for three days. There is a small cement room, on the terrace in front of the Shrine of the Báb, so small, it is almost more a box than a room. This was Abu’l-Qásim’s room.

On 25 February 1932, the night before Abu’l-Qásim died, Shoghi Effendi had two puzzling but significant dreams in which the greenery around the Shrine had withered away as if it had been singed off. A few hours later, Shoghi Effendi learned that Abu’l-Qásim had passed away, and he understood the significance of his dreams.

Shoghi Effendi sent a cable to the Bahá'í world about this wonderful man whom he so dearly loved for his devotion and beautiful character.:

Profound sorrow preoccupations occasioned by unexpected passing of Abu'l-Qasim custodian International Archives and caretaker gardens Bab's Holy Shrine causing unavoidable delay preparation manuscript "Bahá'í World." Urge emphasize in "Bahá'í News" his marvelous self-abnegation and trustworthiness as outstanding qualities of a remarkable character.

The Guardian’s love for Abu’l-Qásim, and his deep sensitivity are evident in the fact that, although he was forced to demolish Abu’l-Qásim’s shed several times over a period of decades, when he was building the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb, and extending the terraces, he rebuilt the room, each time, a little further west, because of its association with Abu’l-Qásim. Shoghi Effendi never forgot a friend.

Exactly 20 years later, Ugo Giachery was on pilgrimage and stayed overnight in the Mansion of Bahjí. The Guardian asked him what he had first noticed upon entering the Mansion, and was looking at Ugo intently, waiting for his answer, with an air of expectation on his beautiful face.

Ugo Giachery—as he always did—gave his Guardian the right answer. He told Shoghi Effendi that the first thing he had noticed was the framed photograph of an interesting Persian man’s face at the top of the staircase.

The Guardian’s’ face glowed with joy and he told Ugo:

Oh, I am glad you did see it, how observant you are. I placed that picture there myself for everyone to see. It is our remarkable and celebrated gardener Abu'l-Qasim, whose services to the Master and myself will never be forgotten.

From the moment Shoghi Effendi had placed Abu’l-Qásim’s photograph at the top of the Mansion’s staircase, the humble and devoted gardener would be the first face to welcome every pilgrim, forever and he would keep watch on Bahjí forevermore as he had when he was alive.

Top, left and right: A Tablet in Bahá'u'lláh’s own handwriting (Bahá'í Sacred Relics). A Tablet in the Báb’s handwriting addressed to His wife, Khadíjih Bagum and sent from Búshihr before His departure for His pilgrimage to Mecca (Bahá'í Sacred Relics). Bottom, from left to right: A tablet in 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s handwriting to the Bahá'ís in America regarding Dr. Zia Baghdádí and his wife (Bahá'í Sacred Relics). A letter in Persian in the writing of Shoghi Effendi addressed to Star of the West concerning his temporary absence from the Holy Land (Bahá'í Sacred Relics). A letter in English in the handwriting of Shoghi Effendi addressed to the Bahá'ís of Canada (Bahá'í Historical Facts).

The Báb, Bahá'u'lláh, 'Abdu'l-Bahá, and the Guardian all wrote letters—but they were called Tablets for the three Central Figures. Essentially, because many of them were addressed to individuals, they were, in fact “letters.” And some of these Tablets were strikingly important.

The Tablet to Mullá Báqir—which is considered by Dr. Nader Saiedi to be the mystical and theological will and testament of the Báb—was a letter from the Báb to the Thirteenth Letter of the Living.

Bahá'u'lláh’s Súriy-i-Damm (Surah of Blood)—a vastly important Tablet on His station and His Declaration which was responsible for most Persian Bábís converting to the Bahá'í Faith—was revealed for Nabíl.

One of the most important Tablets of 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s entire ministry was a letter to an eminent entomologist: The Tablet to Dr. Auguste Forel.

The way Shoghi Effendi wielded the letter format was disruptive, novel, ground-breaking. The Guardian was a genius at using the tools he had at his disposal in a way no one had ever thought of using them before.

The Guardian was the most effective communicator there ever was. By the sheer power of his pen, the hundreds, thousands of Bahá'ís arose and planted the banner of the Faith of Bahá'u'lláh in every single territory and every single island in the world. In ten years.

There are rules to write successful books: short sentences, short paragraphs, words your reader does not need to look in the dictionary.

Shoghi Effendi’s letters were the opposite: they ran up to 140 pages, with some paragraphs spanning two full pages, containing sentences that sometimes were three-quarters of a page long, with sometimes four pages in a row of quotation after quotation, some containing 14th century words, others containing the third or fourth definition of a polysemous word—meaning a word that has many meanings, like the word “bank.”

If the Guardian wanted to convey a rush of urgency, he would send cables in his perfect cable-English, clipped, alliterated or rhyming. But again, the Guardian did not obey convention. His cables were not always short: some ran several pages.

The content of Shoghi Effendi’s letters is first and foremost concerned with the Administrative Order of Bahá'u'lláh, deepening the Bahá'í community, providing a historical analysis of the state of the world, raising the awareness of Bahá'ís as to their responsibilities, educating the believers on Bahá'u'lláh’s New World Order, ensuring the protection and propagation of the Faith, and prosecuting 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s Tablets of the Divine Plan.

Shoghi Effendi was a man of action, constantly doing, never wasting time, always efficient, and, endowed with infallibility. The Guardian cast his unerring glance backward into the past to analyze historical events and provide a view of the Heroic of the Faith, but he also fix his glance firmly into the future, towards the victories of the Ten Year Plan and the distant Golden Age of the Cause of Bahá'u'lláh.

The Guardian came to master English to such a degree that he could blend modern words and ancient turns of phrases, navigate in tone between warmth and authority, elevate, astonish, move profoundly, and even inspire reverence. In effect, the Guardian seamlessly moved between formal and intimate language, wrote in a dignified yet loving tone, addressed a dual historical and futuristic perspective, and ranged in scope from the personal to the world-encompassing.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum stated that Shoghi Effendi’s English had a double effect on the Bahá'í world: not only did it elevate the reader, but it simultaneously fed their mind and soul with truth. The Guardian was a writer. But unlike most writers, he was not telling stories or stating facts. He was using his words to transform the world, and that is the main reason the Guardian’s English is like no one else’s: because no one else had the destiny of the planet at the forefront of their preoccupations for 36 years. That is why the Guardian’s style is inimitable.

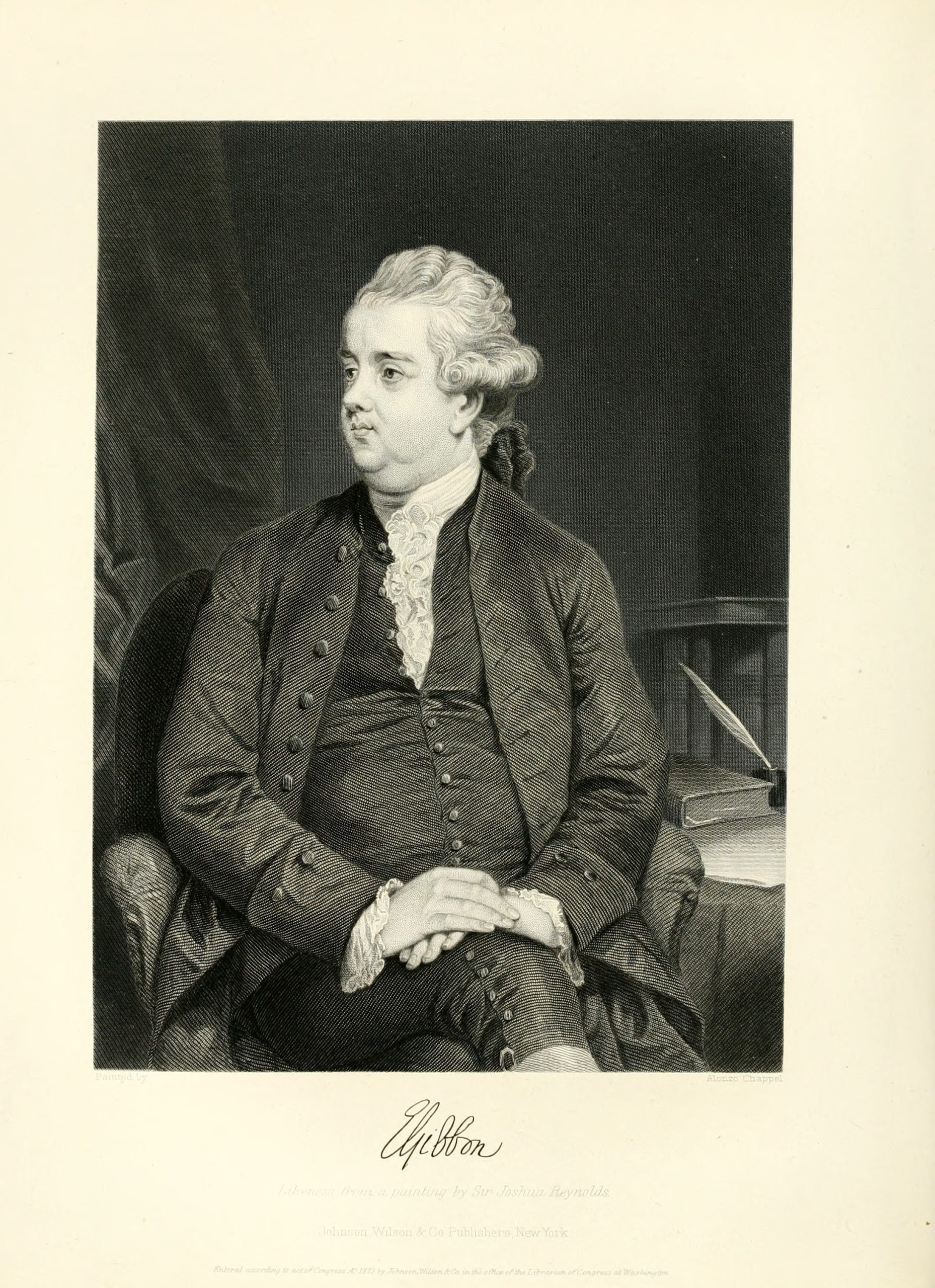

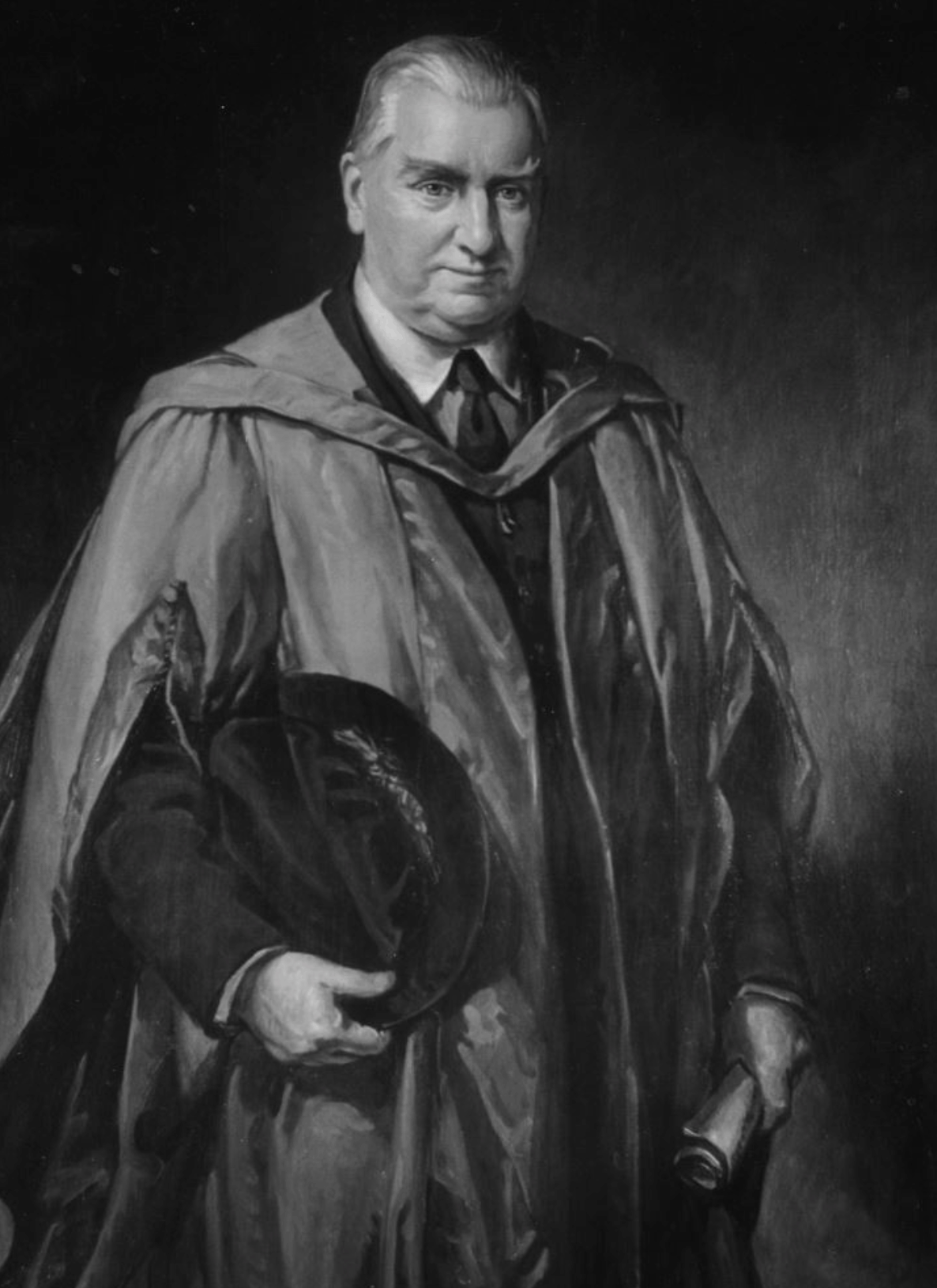

Edward Gibbon. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

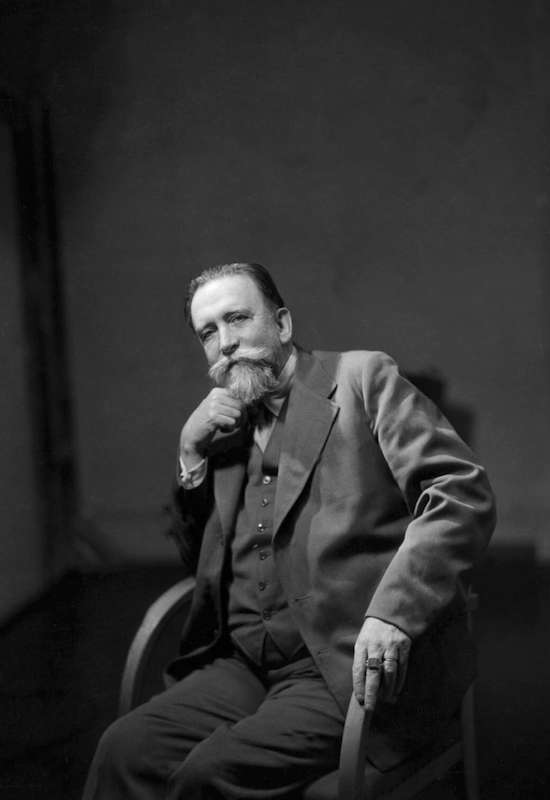

Edward Gibbon was an 18th century English essayist, historian, and politician, most famous for his historical masterpiece, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, published in six volumes between 1776 and 1788. Gibbon was well-known for his irony.

Shoghi Effendi’s love for Edward Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire was a real thing. Shoghi Effendi loved Gibbon his entire life. When he took his beloved wife to London, they sat on a park bench and Shoghi Effendi read Rúḥíyyih Khánum Gibbon out loud. When he died, Shoghi Effendi had a copy of Gibbon’s masterpiece nearby.

The Guardian loved few things and he loved them passionately, and Gibbon’s English was one of those things. Dr. Ann Boyles, who is the foremost expert on the Guardian’s epistolary style, points out characteristics of Gibbon’s style which Shoghi Effendi sublimated to a degree Gibbon could not have dreamt of.

In particular, Dr. Boyles speaks about Gibbon’s lengthy yet balanced sentences, his careful construction of long paragraphs that cannot be taken apart without losing an essential meaning.

These are present in the Guardian’s writings, but because his subject is Bahá'u'lláh and the Bahá'í Faith, an alchemy operates that has a profound effect on the soul—Gibbon, of course was writing about Cruelty, Follies, and Murder of Commodus or Rome is Thrice Besieged and at Length Pillaged by the Goths.

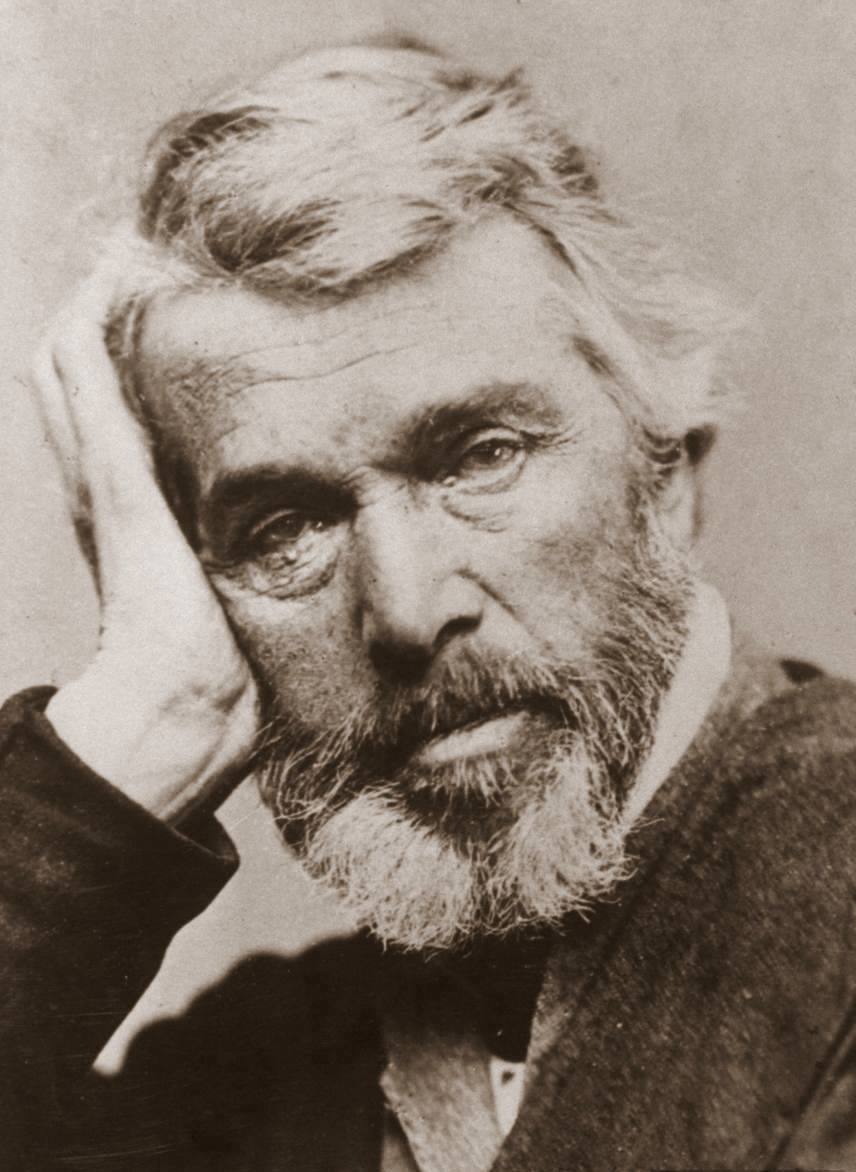

Thomas Carlyle. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

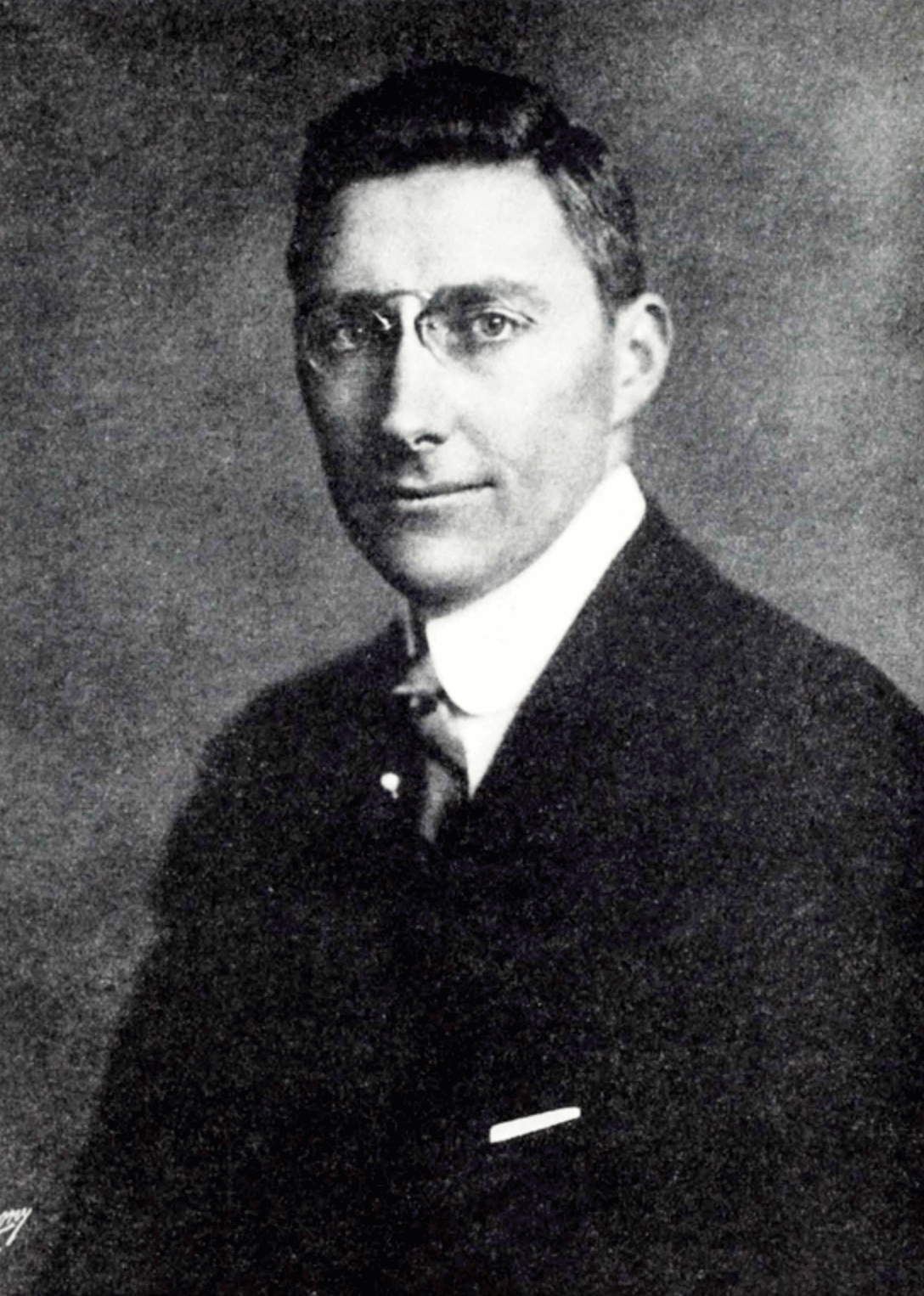

To a lesser degree, the Guardian also admired the style of Thomas Carlyle, a very influential 19th century Scottish essayist, historian, and philosopher.

Dr. Boyles’ analysis of Thomas Carlyle’s style is interesting because he shares a commonality with Gibbon in that his writing is complex because it expresses complex thoughts. Carlyle, however had a talent that Gibbon lacked, which was to rouse people to action, to inspire them and elevate them, praise their achievements, challenge them to respond to their appeals, a capacity which the Guardian came to master to perfection.

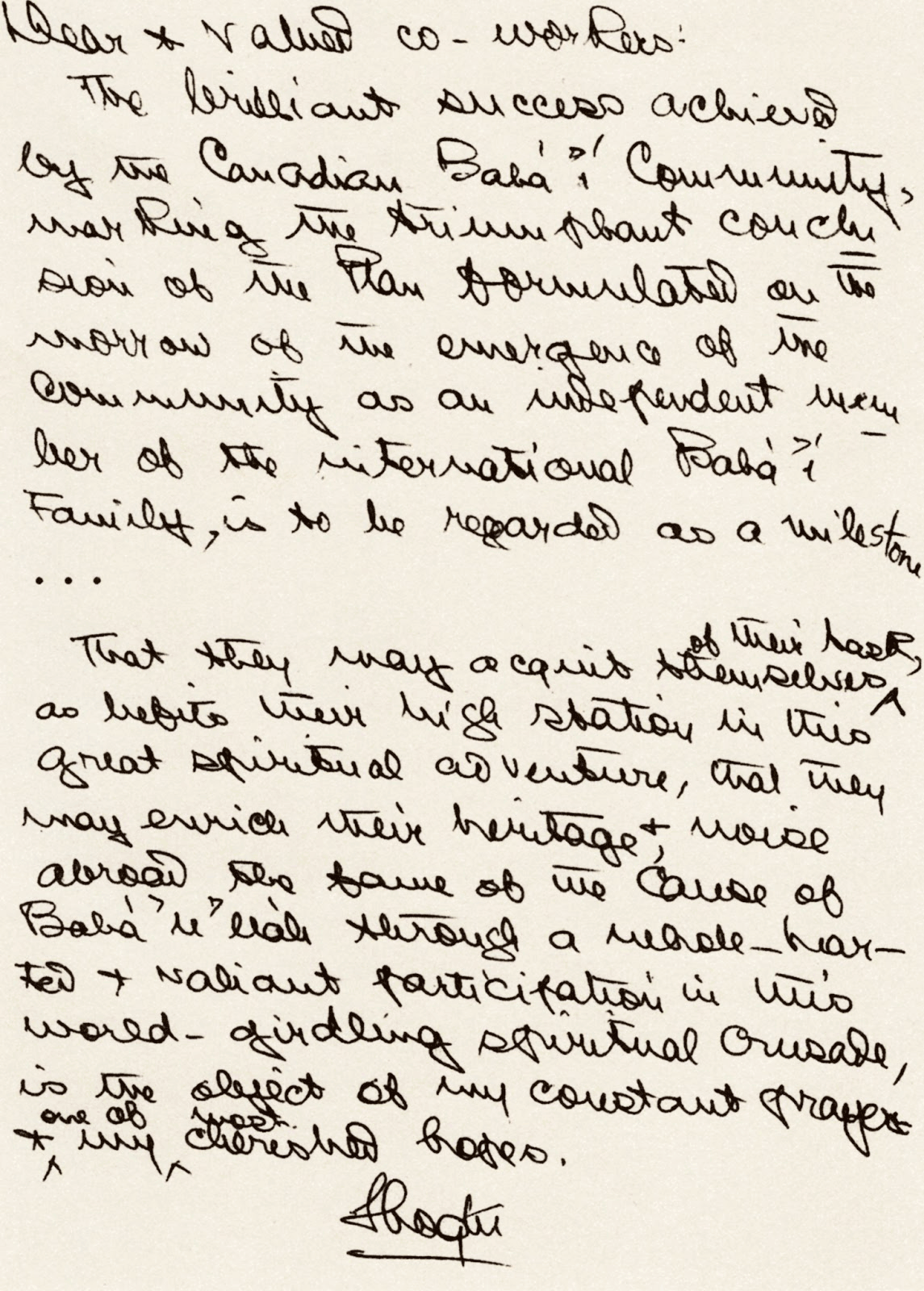

Letter from Shoghi Effendi published in Messages to Canada. Source: Bahá'í Historical Facts.

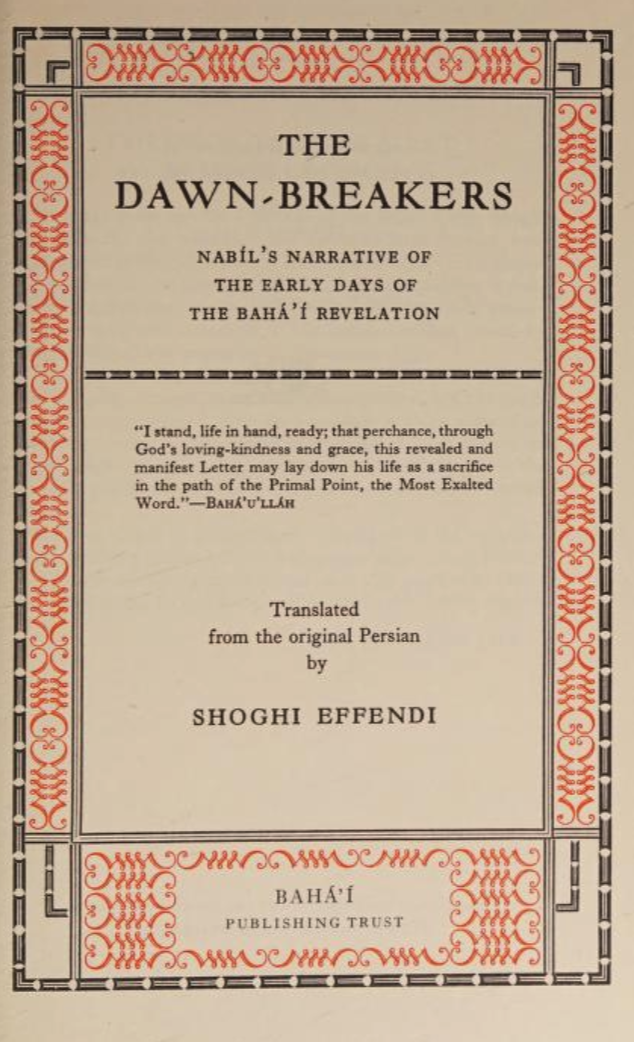

During his lifetime, Shoghi Effendi only wrote one book, God Passes By, published in 1944, although it is not only unfair but inaccurate not to include The Dawn-Breakers as a book authored by Shoghi Effendi. Outwardly, it is indeed a translation of Nabíl’s Narrative, but Shoghi Effendi re-created the book in English to such an extent that it cannot justly be considered a straight translation.

It is estimated that the Guardian wrote a total of 34,000 letters and cables during his ministry with 16,370 letters currently in The Center for the Study of the Sacred Texts, at the Bahá'í World Centre.

The shortest cable Shoghi Effendi ever sent was one word long—“Welcome”—inviting the first Bahá'í on pilgrimage to the Holy Land after World War II, although there are no doubt many more examples of Shoghi Effendi’s delightful conciseness in one-word telegrams and cables.

The longest letter Shoghi Effendi ever wrote was the 136-page The Promised Day Is Come, written in 1941, a general letter to the Bahá'ís of the West.

For Rúḥíyyih Khánum, the fact that the Guardian wrote The Promised Day is Come in the form of a letter, is a profound indication of his deep modesty.

The main letters he wrote are below, those marked with an asterisk can be found on the official website, the Bahá'í Reference Library:

- 1929: The World Order of Bahá’u’lláh*

- 1930: The World Order of Bahá’u’lláh: Further Considerations*

- 1931: The Goal of a New World Order*

- 1932: Bahíyyih Khánum: Eulogy for the Greatest Holy Leaf

- 1932: The Golden Age of the Cause of Bahá’u’lláh*

- 1933: America and the Most Great Peace*

- 1934: The Dispensation of Bahá’u’lláh*

- 1936: The Unfoldment of World Civilization* (in the World Order of Bahá'u'lláh)

- 1939: The Advent of Divine Justice*

- 1941: The Promised Day Is Come*

- 1947: The Challenging Requirements of the Present Hour (in Citadel of Faith)*

Many of his letters have been compiled in geographical compilations—those available on the official Bahá'í Reference Library are marked with an asterisk:

- Alaska: High Endeavors: Letters to Alaska

- Australia and New Zealand: Messages to the Antipodes

- Canada: Messages to Canada

- Germany and Austria: Light of Divine Guidance, Volumes 1 and 2

- India, Pakistan, and Myanmar: Messages of Shoghi Effendi to the Indian Subcontinent

- Japan: Japan Will Turn Ablaze

- New Zealand: Arohanui: Letters to New Zealand

- Messages to the Bahá’í World: 1950–1957

- The United Kingdom: The Unfolding Destiny of the British Bahá’í Community

- The United States: Citadel of Faith*

If you would like to learn more about these geographical compilations of the Guardian’s letters and cablegrams, you can download the 23-page document below or click on this link:

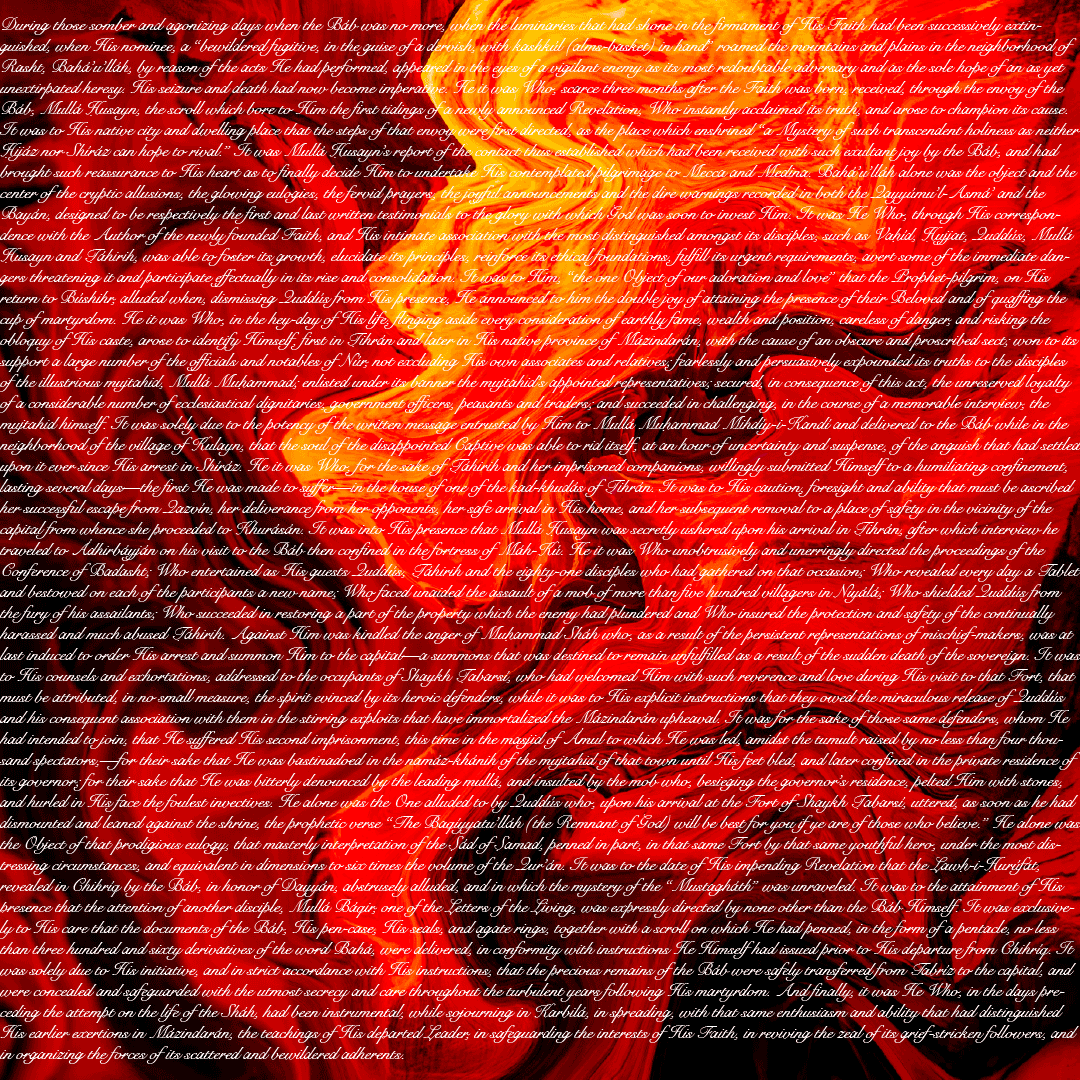

A single, four-page paragraph in God Passes By, during the. Ministry of the Báb, which begins with “During those somber and agonizing days when the Báb was no more” and can be found starting here on Bahá'í Reference Library. Photo by DAVE NETTO on Unsplash

When Rúḥíyyih Khánum was reading God Passes By, she came across one of Shoghi Effendi’s distinctive long paragraph—Shoghi Effendi’s long sentences were equally distinctive. But this wasn’t just long. It was immense, it was a cathedral of a paragraph.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum looked at Shoghi Effendi and said:

Guardian, you know that is rather long paragraph. It's two and a half pages long.

Shoghi Effendi looked at Rúḥíyyih Khánum, with a look on his face which she describes as, ”if he weren't the Guardian of the Faith I'd say sheepishly.”

But Shoghi Effendi did not change the paragraph, and in fact, there are several paragraphs in God Passes By that run over three or four printed pages, the first one of which is in the Foreword and goes from pages 7 to 10, but there is another four-page paragraph in the first section of the Ministry of the Báb between pages 65 and 68. There are many others.

Shoghi Effendi’s paragraphs, if one analyzes God Passes By, for example, are perfectly thematic. Each paragraph contains an idea, and one can give each paragraph its own, distinctive title. If what the Guardian wanted to express in that paragraph is a relatively simple idea, the paragraph itself is very short.

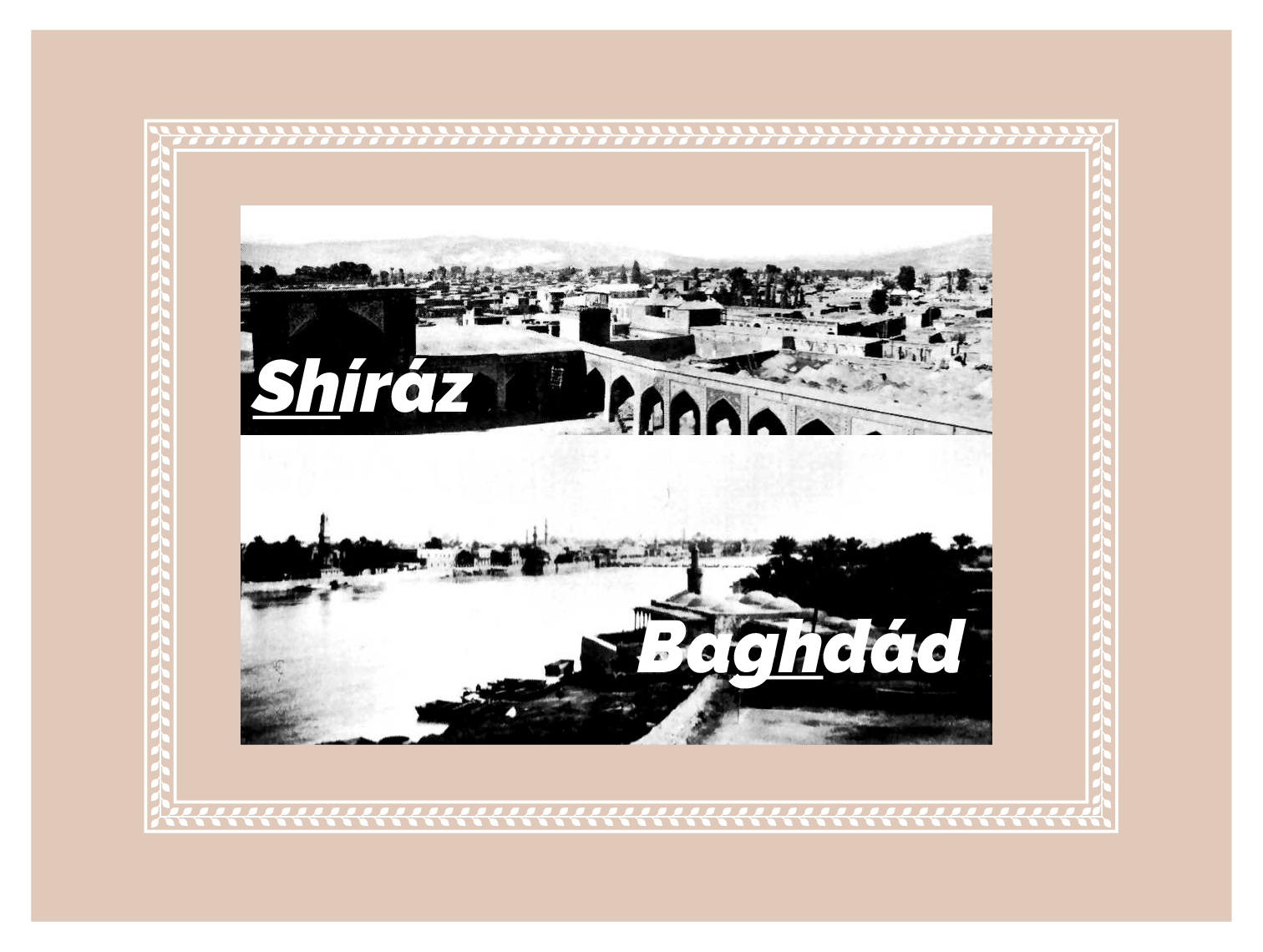

For example, there is a very short paragraph on page 141 dedicated to explaining how Baghdad came to be the place of Bahá'u'lláh’s first exile: it was chosen by Him.

Every monumental multi-page paragraph written by Shoghi Effendi should immediately be considered vital. The paragraph is so long because it contains a very complex chain of interrelated concepts or events that form a single unit. It is long because it expresses Shoghi Effendi’s idea perfectly. The Guardian always used his words sparingly, and there is no excess “fat” in any of his sentences or paragraphs.

The Guardian’s long sentences follow the same idea. If an idea is simple, the sentence is short, like this three, dynamic, clipped sentences on page 52, describing the actors of the Conference of Badasht:

The Captain of the host was Himself an absentee, a captive in the grip of His foes.

The arena was a tiny hamlet in the plain of Badasht on the border of Mázindarán.

The trumpeter was a lone woman, the noblest of her sex in that Dispensation, whom even some of her co-religionists pronounced a heretic.

If the idea contained in the sentence is extraordinary complex, the Guardian writes a long sentence.

Shoghi Effendi at Syrian Protestant College. Source: The Priceless Pearl, between pages 56 and 57.

These were the titles of Shoghi Effendi, bestowed on him by 'Abdu'l-Bahá in His Will and Testament:

- The Guardian of the Cause of God

- The Sign of God on Earth

- The primal branch of the Divine and Sacred Lote-Tree, grown out, blest, tender, verdant and flourishing from the Twin Holy Trees

- The most wondrous, unique and priceless pearl that doth gleam from out the Twin surging seas

- The blest and sacred bough that hath branched out from the Twin Holy Trees

- The sacred and glorious Being… branched from the Sadratu’l-Muntahá

- The blest and sacred bough that hath branched out from the Twin Holy Trees

- The youthful branch branched from the two hallowed and sacred Lote-Trees

- The fruit grown from the union of the two offshoots of the Tree of Holiness

- The Chosen Branch

- The Interpreter of the Word of God

- The sacred and youthful branch

- And the twig that hath branched from and the fruit given forth by the two hallowed and Divine Lote-Trees

Nothing is more significant, more telling of Shoghi Effendi’s love for Bahá'ís than the fact that he—the object of such prophecy, the descendent a direct line from the Báb’s grandfather, the great-grandson of Bahá'u'lláh, the grandson of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, the Guardian of the Faith—would choose to sign his letters to individual Bahá'ís and youth, ever so humbly as:

Your true brother, Shoghi.

It is particularly touching that the Guardian signs “Shoghi,” given the fact that when he was a child, 'Abdu'l-Bahá had forbidden even his parents to call him by his first name, instead instructing everyone to refer to him as Shoghi Effendi.

Here are some of Shoghi Effendi’s closings with this signature:

May the Almighty bless your efforts, guide your steps, and enable you to further the interests, and consolidate the foundations, of this noble institution which has already rendered such notable services to our beloved and glorious Faith,

Your true brother, Shoghi.

May the Spirit of Bahá'u'lláh guide, sustain and bless you in your meritorious endeavours, enable you to deepen your knowledge of the essential verities of His Faith, and aid you to promote effectively, in the days to come, the vital interests of its institutions,

Your true brother, Shoghi..

Assuring you of my loving prayers for your success in the service of our beloved Faith.

Your true brother, Shoghi.

May the Almighty bless, guide and sustain you always, remove all obstacles from your path, and enable you to further the vital interests of His Faith in the days to come.

Your true brother, Shoghi.

May the Almighty bless, guide and sustain you always, and aid you to render notable services in the days to come,

Your true brother, Shoghi.

Assuring you of my fervent prayers for the success of your valued activities in the service of our beloved Faith,

Your true brother, Shoghi.

May the Almighty guide your steps, aid you to acquire a fuller knowledge of the essentials of His Faith, and render effective service to its institutions in the days to come

Your true brother, Shoghi.

May the Almighty bless your continued and meritorious endeavours, guide every step you take, and fulfil every wish you cherish, for the promotion of His glorious Faith,

Your true brother, Shoghi.

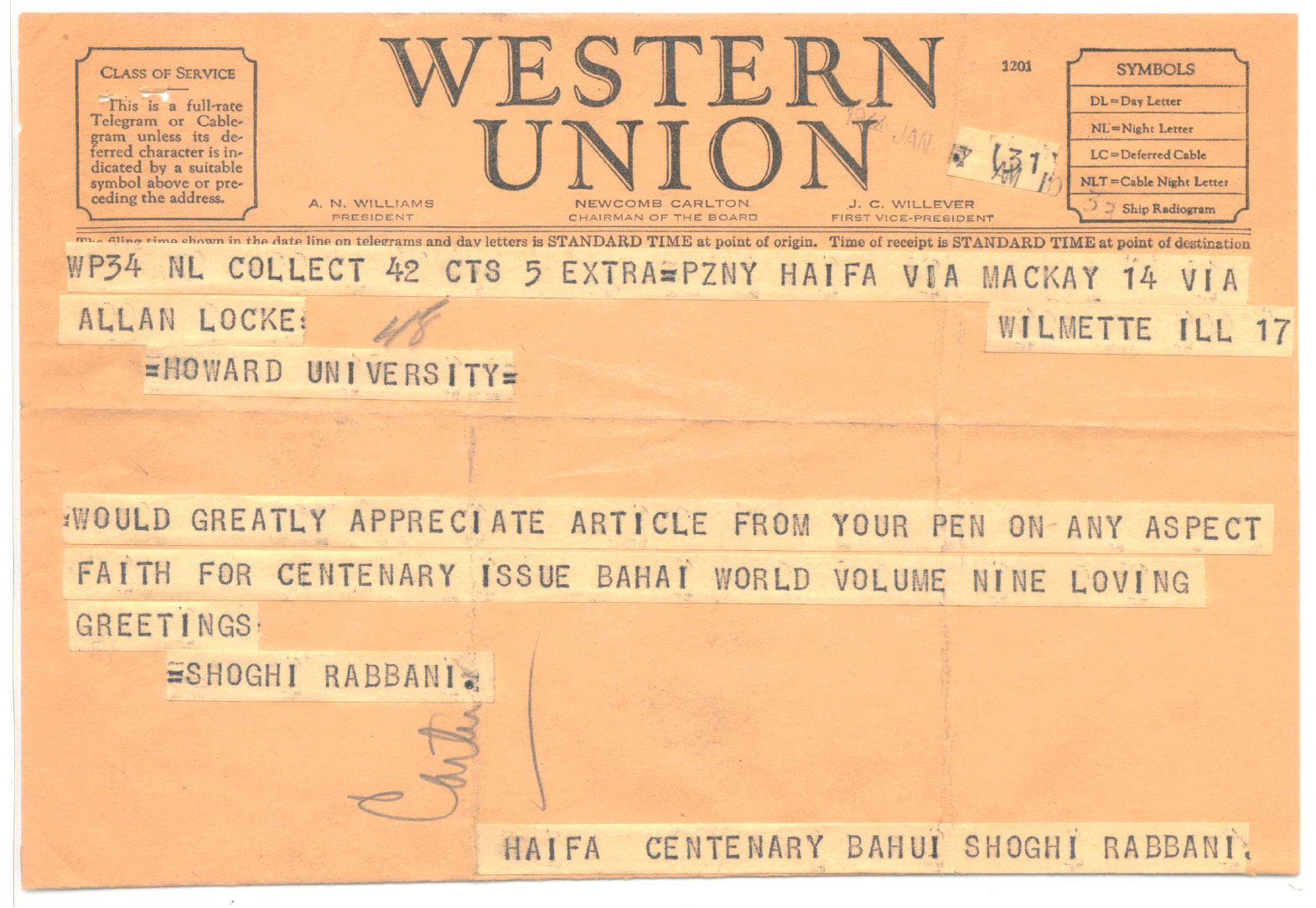

17 January 1944 Western Union cablegram from Shoghi Effendi to Alain Locke, cablegram: Source: Alain Locke Papers, Box 164-12, Folder 3 (Bahá’í World). This cablegram was first published in “Alain Locke: Bahá'í Philosopher," p. 39, republished in Alain Locke: Faith and Philosophy, p. 189. Source: Bahá'í Library Online.

Shoghi Effendi once explained to Rúḥíyyih Khánum that he didn’t use cables and telegrams because they saved time, but because they carried with them a psychological effect and conveyed a sense of urgency and drama that helped drive home the message they contained.

It is fair to say that Shoghi Effendi elevated the language of cables and telegrams to such a degree that, wielded by the Guardian of the Faith, they became something of a literary achievement.

Shoghi Effendi was completely unimpeded by any preconceptions in his use of cables. They weren’t always short, the way other peoples’ were. Some of Shoghi Effendi’s cable are a page long, the length of letters, and not inexpensive, which was why cables were generally short: they had a per-word cost.

The way cables worked in the 1930s and 1940s, was that there was a minimum of ten words for a fixed cost. Between Palestine and London, it cost 2 shillings and 6 pence (30 pence) for the minimum ten words. After the ten-word minimum, each additional word cost 3 pence.

By comparison, sending a letter was only 2.5 pence.

Shoghi Effendi wrote telegrams and cablegrams differently than he wrote anything else, because he thought in the abbreviated form when he composed them. This is important because most people sending cables and telegrams wrote normally, then removed all the words they could remove and retain the essential meaning.

Shoghi Effendi actually composed his cables and telegrams as they were sent, he did not edit them, which explains why his cables are so graphic, powerful, and dramatic, and why they read perfectly without the need to insert words.

Photo by Chirag Nayak on Unsplash.

The Guardian’s cables are a time capsule of his personality, his feelings, his reactions, his instructions. Sometimes they were sweet and loving and tender, and at other times they were sharp, edgy, and dry. Shoghi Effendi was a talented writer, who knew how to fashion emotions and elicit reactions out of mere words.

The Guardian had a few close friends. In his cables to these dear ones, his love just pours through. Once, the Guardian had been ill, and Philip Sprague expressed concern over his health, ending his cable with’

…heart full of love.

Shoghi Effendi cabled back:

Have recovered. Fully reciprocate your great love.

Shoghi Effendi was very close to Dr. Ugo Giachery, who collaborated with him from Italy for Shoghi Effendi’s construction needs. Their cables are also filled with sentiment. Once, the Guardian wrote to Dr. Giachery:

Kindly order twenty-four additional lamp posts identical those ordered love.

But these cables were very, very unusual for the Guardian. He did not have many friends with whom he was this intimate. It was a rarity, indeed.

Shoghi Effendi knew how to carve cables out of hard words, and some of the ones he wrote when he was not satisfied with an individual or an institution were sharp and powerful.

Expecting frequent comprehensive reports…

Beware disobedience my wishes.

Warn you again

beware neglect…

Shoghi Effendi enjoyed saying what he had to say in the least amount of words, and when the first Bahá'í asked for permission to come on pilgrimage after World War II, Shoghi Effendi cabled:

Welcome.

Photo: TOMOKO UJI on Unsplash.

A mere four months after The Goal of a New World Order, Shoghi Effendi wrote a 17-page message addressed to the friends in the United States and Canada on Naw-Rúz—21 March 1932—titled The Golden Age of the Cause of Bahá'u'lláh.

Shoghi Effendi begins The Golden Age of the Cause of Bahá'u'lláh with praise for the accomplishments of the believers, the protection and resilience of the Faith of Bahá'u'lláh, its victory over its enemies and the progress made in rearing its Administrative Order. Shoghi Effendi also speaks about the preeminent station of the Báb. One principle that Shoghi Effendi develops in this letter is the importance of the Bahá'í principle of non-involvement in politics.

This letter is a superb exposition of the divine, mystical aspects of the Bahá'í Faith, and in it, at a time when the world is welcoming springtime, he also speaks about the spiritual springtime ushered into the world with the Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh.

Shoghi Effendi once again clarifies the process of Progressive Revelation and the relationship of the Bahá'í Dispensation to those of the past, but also offers Bahá'u'lláh’s solutions to the current problems of an ailing world.

Photo: Mark Tegethoff on Unsplash.

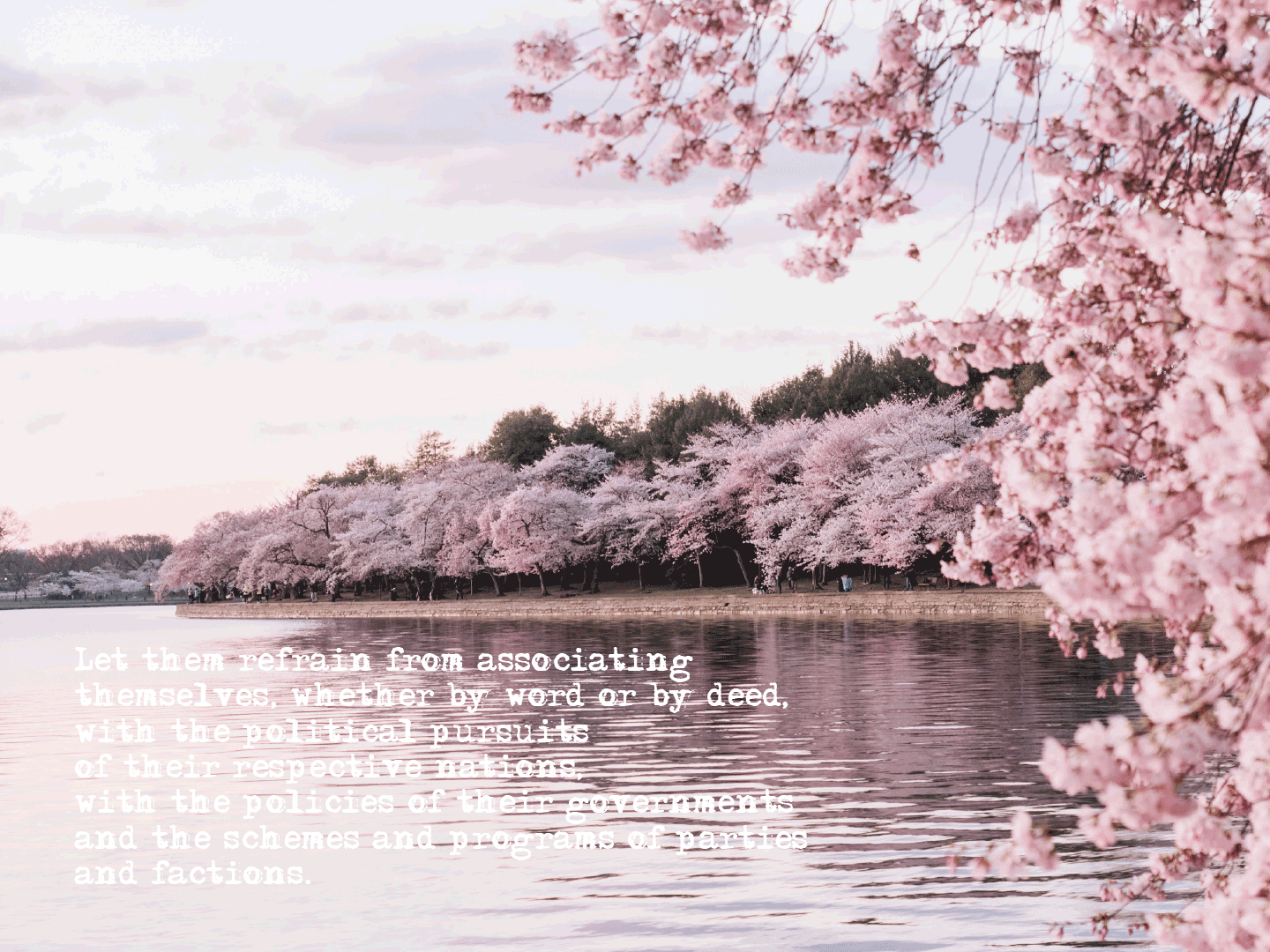

In this exquisite excerpt from The Golden Age of the Cause of Bahá'u'lláh, rhythmic and almost poetic in its eloquence, the Guardian cautions Bahá'ís against division, partisan politics, prejudice, the manipulation of political parties and the media. It is a timeless message that we need now more than ever, and we would all do well to not only meditate on it but even memorize it:

Let them refrain from associating themselves, whether by word or by deed, with the political pursuits of their respective nations, with the policies of their governments and the schemes and programs of parties and factions. In such controversies they should assign no blame, take no side, further no design, and identify themselves with no system prejudicial to the best interests of that worldwide Fellowship which it is their aim to guard and foster. Let them beware lest they allow themselves to become the tools of unscrupulous politicians, or to be entrapped by the treacherous devices of the plotters and the perfidious among their countrymen. Let them so shape their lives and regulate their conduct that no charge of secrecy, of fraud, of bribery or of intimidation may, however ill-founded, be brought against them. Let them rise above all particularism and partisanship, above the vain disputes, the petty calculations, the transient passions that agitate the face, and engage the attention, of a changing world. It is their duty to strive to distinguish, as clearly as they possibly can, and if needed with the aid of their elected representatives, such posts and functions as are either diplomatic or political from those that are purely administrative in character, and which under no circumstances are affected by the changes and chances that political activities and party government, in every land, must necessarily involve. Let them affirm their unyielding determination to stand, firmly and unreservedly, for the way of Bahá’u’lláh, to avoid the entanglements and bickerings inseparable from the pursuits of the politician, and to become worthy agencies of that Divine Polity which incarnates God’s immutable Purpose for all men.

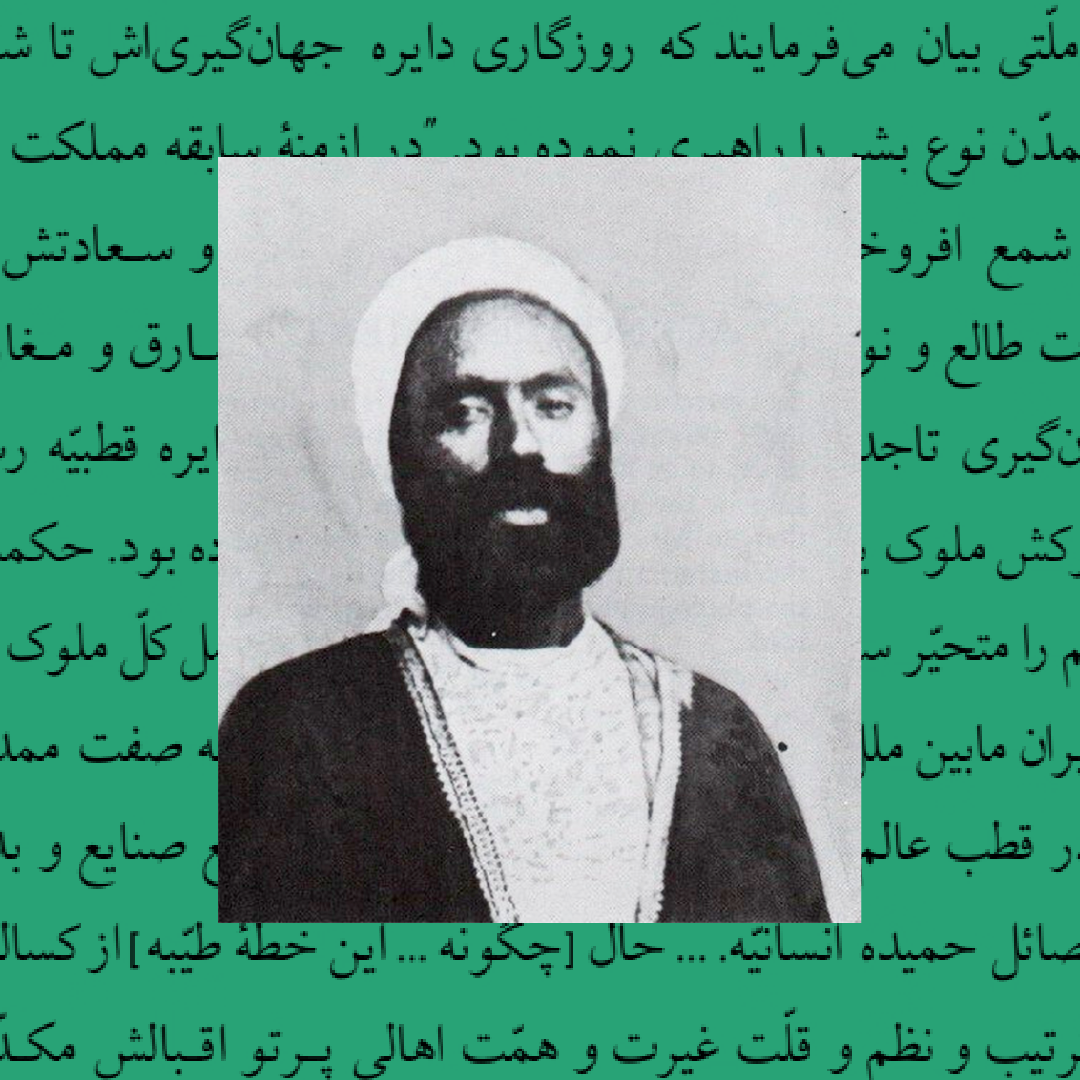

Nabíl—born Yar-Muḥammad son of Gulam, known as Nabíl-i-Zarandí and surnamed Nabíl-i-A‘ẓam by Bahá'u'lláh—author of The Dawn-Breakers (Bahá'í Blog). Background: Page 50 of Taríkh-i-Nabíl—Nabíl’s Narrative (Afnán Library).

Muḥammad Zarandí, titled by Bahá'u'lláh Nabíl-i-A’ẓam, was, according to Shoghi Effendi, the “Poet-Laureate” of the Blessed Beauty. From the moment he became a Bábí, he lived a life of service to Bahá'u'lláh, and spent all his time on teaching and proclamation missions for Him until he moved to the Holy Land and lived the rest of his life in the shadow of Bahá'u'lláh.

Nabíl was a historian, and he kept meticulous notes of his interviews with witnesses to the Dispensation of the Báb and the early decades of the Heroic Age of the Faith for 40 years, and Bahá'ís began encouraging him to use these notes to write a chronicle of the history of the Faith.

But Nabíl refused to begin without Bahá'u'lláh’s blessing.

After Bahá'u'lláh expressed His pleasure at the project, Nabíl sat down and wrote for 18 months, between 1887 and 1888, and Bahá'u'lláh encouraged Nabíl in his important work, revealing two Tablets in his honor which gave Nabíl clear instructions about the narrative, advising him to neither exaggerate nor understate, and neither expand descriptions needlessly nor minimize the importance of certain events.

Nabíl completed his manuscript, Táríkh-i-Nabíl (Nabíl’s Narrative) around 1888 and submitted it to Bahá'u'lláh, receiving His approval ten months later, most probably sometime in 1889.

After receiving the approved manuscript, Nabíl composed a preface, displaying the pure spirit of devotion in which he wrote his masterpiece, in complete submission to Bahá'u'lláh’s good pleasure:

I render thanks to God for having assisted me in the writing of these preliminary pages, and for having blessed and honoured them with the approval of Bahá'u'lláh, who has graciously deigned to consider them and who signified, through His amanuensis Mírzá Áqá Ján, who read them to Him, His pleasure and acceptance.

Mírzá Muḥammad-‘Alí stole two cases of Bahá'u'lláh’s personal effects which contained seals like these—which are in the International Bahá'í Archives—His Tablets, pens, and His corrections to Nabíl’s Narrative. Source: The Life of Bahá'u'lláh: A Photographic Narrative.

Unfortunately, Nabíl’s original manuscript containing Bahá'u'lláh’s corrections was among the papers in Bahá'u'lláh’s two cases stolen by Mírzá Muḥammad-'Alí on the very morning of Bahá'u'lláh’s Ascension, 29 May 1892, and they were never recovered.

From 1889 until 17 April 1930—the first dated letter we have from the Guardian mentioning his work on The Dawn-Breakers—the gems contained in Nabíl’s epic narrative existed only in Persian in Nabíl’s original, uncorrected draft, and had never left the Bahá'í World Centre in Haifa.

Very few Bahá'ís were aware of the history contained in Nabíl’s Narrative. The only real history books available were Bahá'u'lláh and the New Era, and 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s A Traveller’s Narrative.

That was all about to change.

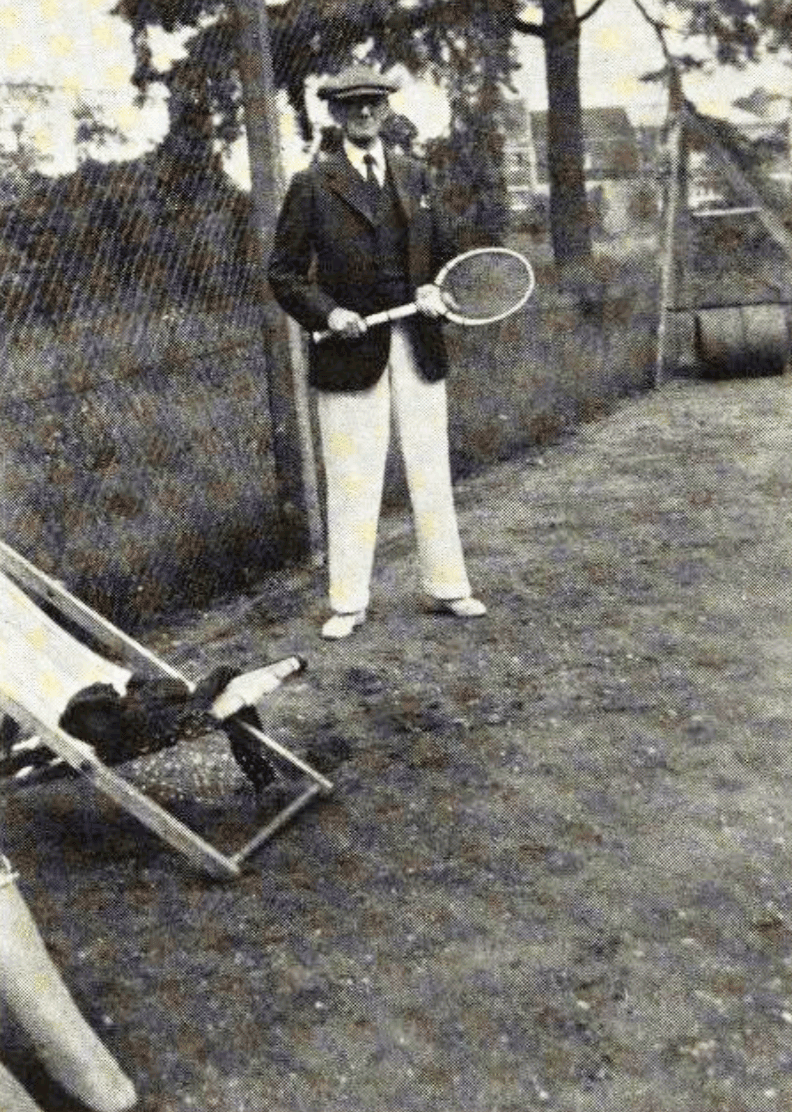

George Townshend, Shoghi Effendi’s literary partner and a lover of tennis like the Guardian, in Hoddesdon, England in 1939. Source: George Townshend by David Hofman, between pages 164-165.

George Townshend was still completing his review of the translation of the Kitáb-i-Íqán on 17 April 1930 when he received the first letter from Shoghi Effendi mentioning his new project: the translation into English of Nabíl’s Narrative:

[Shoghi Effendi] is now working on the translation into English of Nabil’s history. This is the most extensive, detailed and interesting history of the Cause still in M.S. form and as the author, a Bahá’í poet translated by E. G. Browne, was in close association with Mirza Musa, Bahá’u’lláh’s only true brother, it carries a good deal of authority also. Shoghi Effendi would be grateful if you would go over his translation of Nabil and make suggestions and alterations like the ‘Ighan’. Of course in this case you need not be as literal as with sacred writings. Shoghi Effendi wishes me also to suggest to you that with your desire to write Bahá’í plays and tableaus you had better wait for this translation, for in it you will find an embarrassing wealth of material for what you have in mind. I am sure you will find his history quite interesting, as the author was a man of great imagination.

From April to September 1930, Shoghi Effendi sent George Townshend his translation of Nabíl’s Narrative in installments of 100 or more pages, each time with cover pages.

By 5 November 1930, George Townshend had read the entire book, and he had the reaction Shoghi Effendi hoped all Bahá'ís would have. He was heart-broken at the terrible descriptions of martyrdoms, events he knew nothing about. He was shocked by the physical, thrilling character of the history: the heroism, the sacrifices, the sincerity, the steadfastness.

By far the most important aspect of his feedback to the Guardian was that, after reading Nabíl’s Narrative, he felt that it had an immeasurable effect on him, and that the world around him felt less real. He was stimulated at the thought the Faith’s early history was so rich, its heroes so splendid, and he felt imbued with more energy, more courage and more determination.

Now that Nabíl’s Narrative was translated, it needed a title.

And it needed to be published.

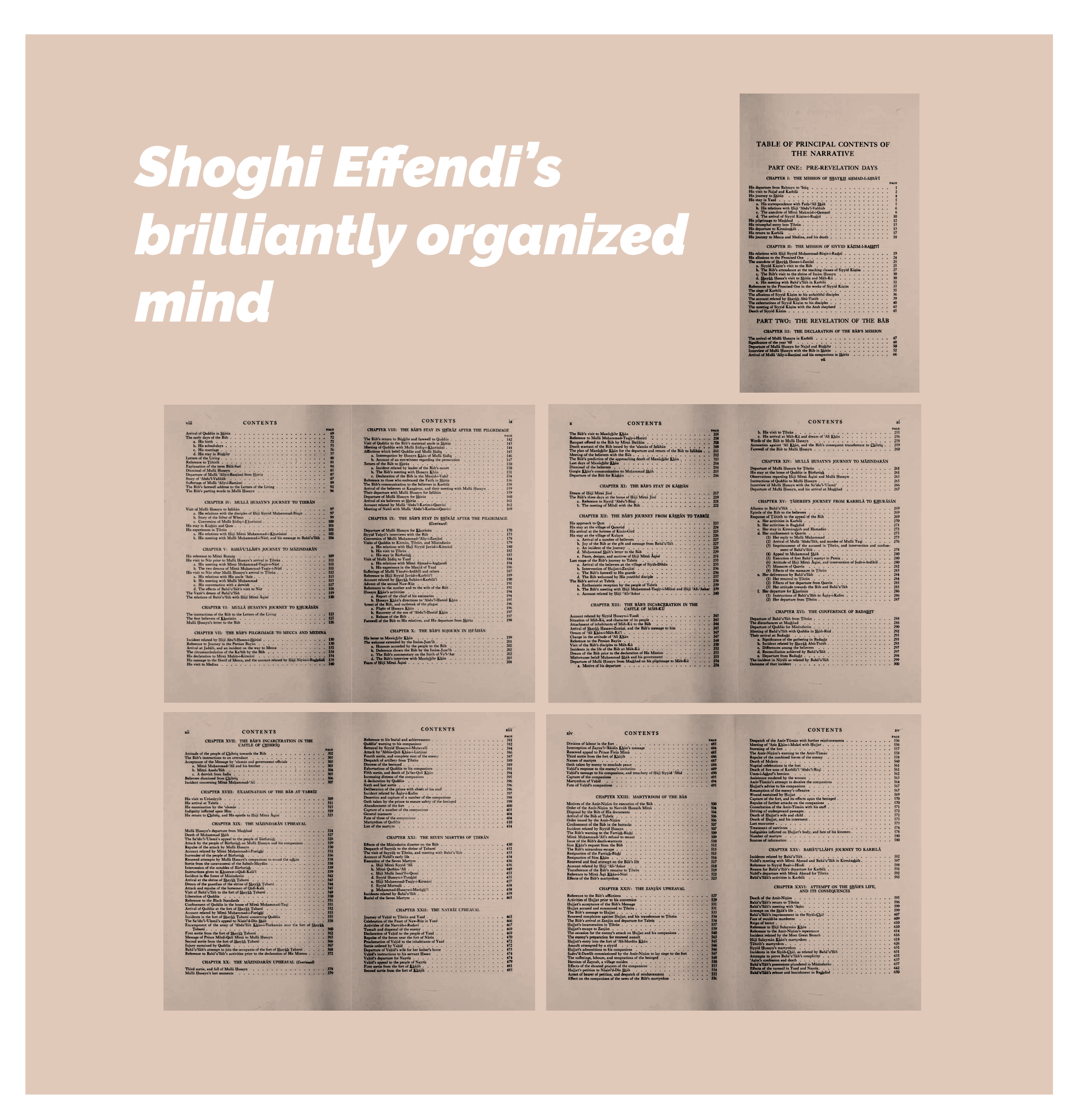

Shoghi Effendi’s brilliantly organized mind, which turned a continuous narrative into 26 chapters and no less than 390 subsections.

Tarikh-i-Nabil, Nabil's Narrative in the original Persian was a literary masterpiece.

In Persian.

But it could not simply be translated in English and published as is.

The original work was a single, continuous uninterrupted story, with several hundred named characters and perhaps even as many perspectives of narration, in classic middle-eastern Russian doll structure, the story starts with one character who encounters another, who continues telling his story until he meets another character and so on and so forth.

Shoghi Effendi would need to completely re-create Nabíl's history for publication—adding chapters, for example—and this is what he expressed in a letter written on his behalf to George Townshend by his secretary from Oxford, England on 14 October 1930:

There are quite a number of questions to consider before we can give this book to the public. The first is its division into chapters with proper indexes, maps, footnotes, etc. that make such a book comprehensible to the public at large. This part of the work Shoghi Effendi has already done and he is in the process of completing.

Back in Haifa on 4 November 1930 Shoghi Effendi continued the list of what a proper English publication of Nabíl’s Narrative needed:

I always maintained that such a book could not be published without a detailed introduction which would give the reader the proper outlook on the subject…the introduction should stress the fact that the followers of the Báb were only seeking to protect themselves from the repeated and fierce attacks of the enemy.

In the same letter, Shoghi Effendi hints at providing historical context for the events in Persia from leading historians such as Lord Curzon.

Title page of the 1953 edition of The Dawn-Breakers. Source: Internet Archive.

The Guardian initially thought of calling the English book “Idylls of the Immortals: Nabíl’s Narrative of the Early Days of the Bahá’í Revelation” but he asked George Townshend for other suggestions.

After struggling with the task, George Townshend eventually came up with the final title, “The Dawn-Breakers,” and the Guardian found it “very appropriate,” but appended a subtitle and the book became “The Dawn-Breakers: Nabíl’s Narrative of the Early Days of the Bahá’í Revelation.”

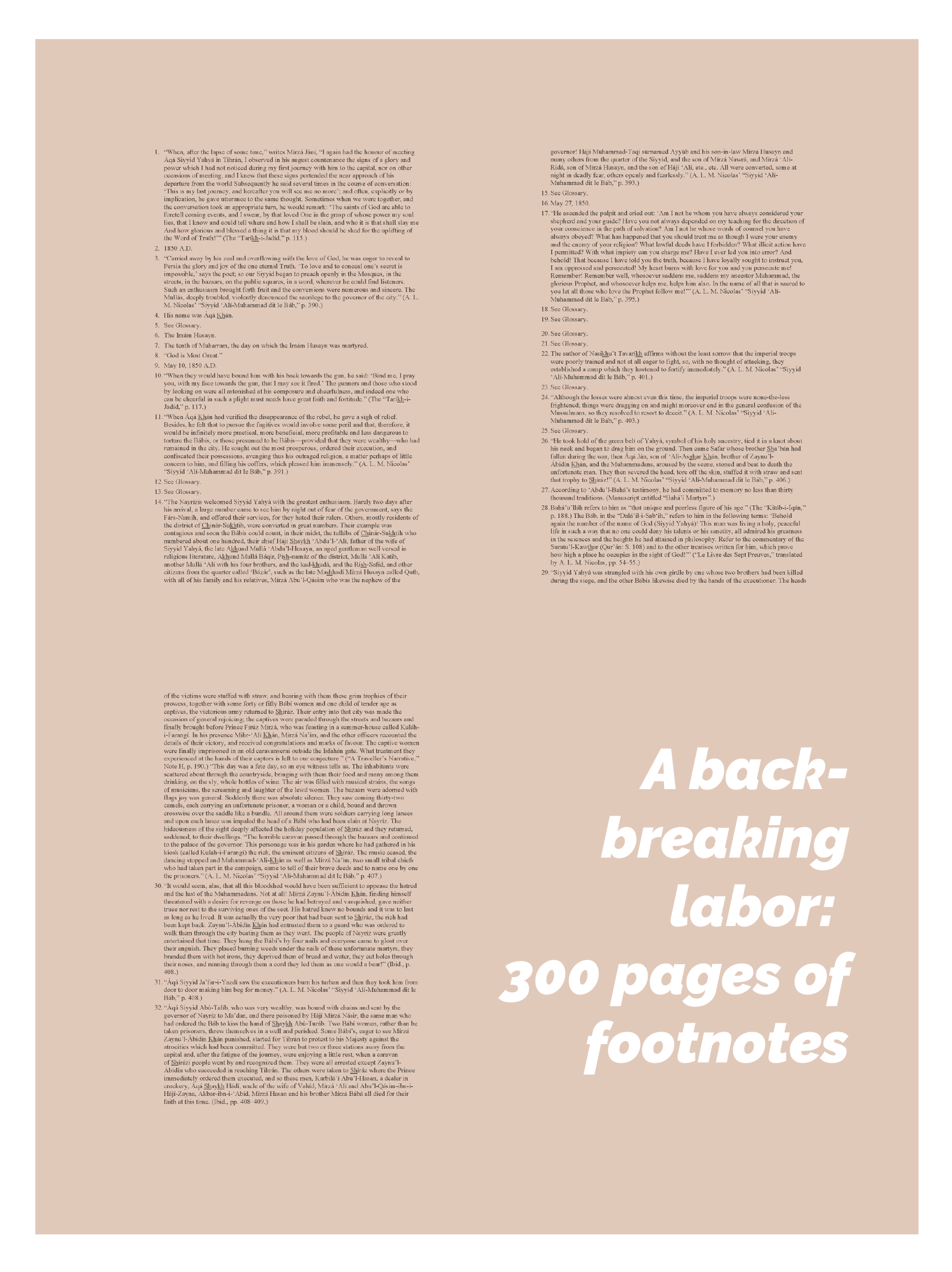

“Back-breaking labor”: Shoghi Effendi worked alone to compile nearly 300 pages of lengthy and detailed historical footnotes. Here are the footnotes for a single chapter, Chapter XII: The Mázindarán uprising.

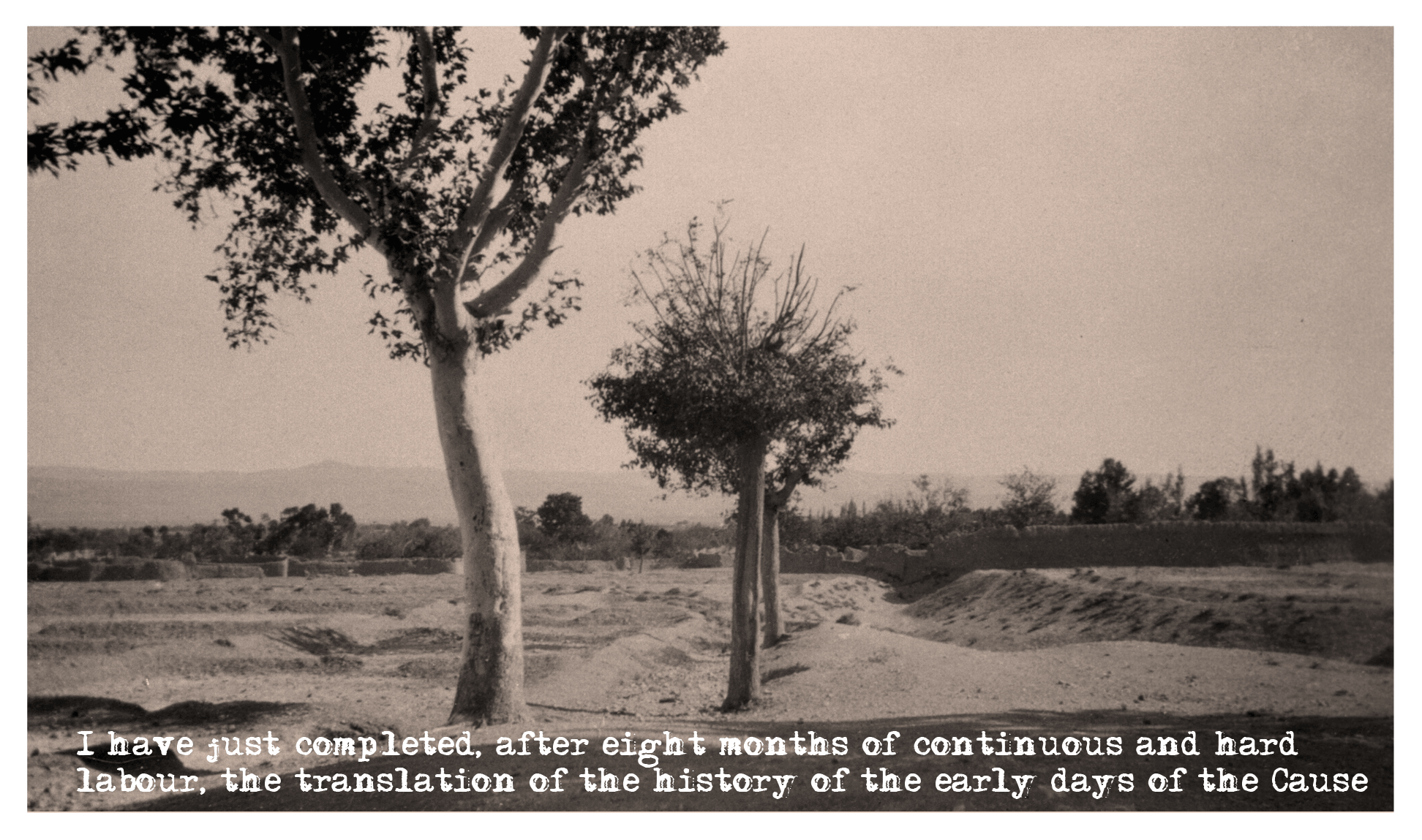

It took Shoghi Effendi almost eight months of continuous, back-breaking work to translate, edit, annotate, illustrate, and prepare The Dawn-Breakers for publication from the summer of 1930 to March 1931.

One of the most arduous tasks for Shoghi Effendi was the compilation of the footnotes.

This is how Shoghi Effendi himself described the process of creating The Dawn-Breakers, in a letter he sent to the National Spiritual Assembly of the United States and Canada, when he was sending them the finished manuscript:

…the translation of Nabíl’s Narrative and the reading of the books (quoted in the footnotes) and arrangement of the notes have taken a great deal of time and have entailed a considerable amount of labour and effort.

For Shoghi Effendi to say that something had been hard, it must have, in fact, been excruciatingly so.

The village of Badasht, where in 1848, Bahá’u’lláh hosted a gathering of the most eminent followers of the Báb, known as Bábís. The meeting established for the growing number of believers the independent character of the Bábí religion, c. 1930, Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

Shoghi Effendi wrote to Martha Root on 3 March 1931, shortly after he had finished preparing The Dawn-Breakers for publication and he described in vivid detail the arduous process of producing the volume, and his state of physical burn-out:

I have just completed, after eight months of continuous and hard labour, the translation of the history of the early days of the Cause and have sent the manuscript to the American National Assembly. The work comprises about 600 pages and 200 pages of additional notes that I have gleaned during the summer months from different books. I have been so absorbed in this work that I have been forced to delay my correspondence... I am now so tired and exhausted that I can hardly write...The record is an authentic one and deals chiefly with the Bab. Parts of it have been read to Bahá'u'lláh and been revised by 'Abdu'l-Bahá... I am so overcome with fatigue caused by the long and sever strain of the work I have undertaken that I must stop and lie down."

Once his masterpiece was finished, the Guardian finally had a worthy gift entirely his own to bestow upon one who had lived through all the events, one who had been a pillar for 'Abdu'l-Bahá, and was now his shield and shelter, and the most important person in his life, the Greatest Holy Leaf.

This is the dedication of The Dawn-Breakers:

To

The Greatest Holy Leaf

The last Survivor of a Glorious and Heroic Age

I Dedicate This Work

In Token of a

Great Debt of Gratitude and Love

Shoghi Effendi completely re-created Nabíl’s Narrative’s.

In the Maestro’s hands, it was transformed into an entirely new type of historical novel.

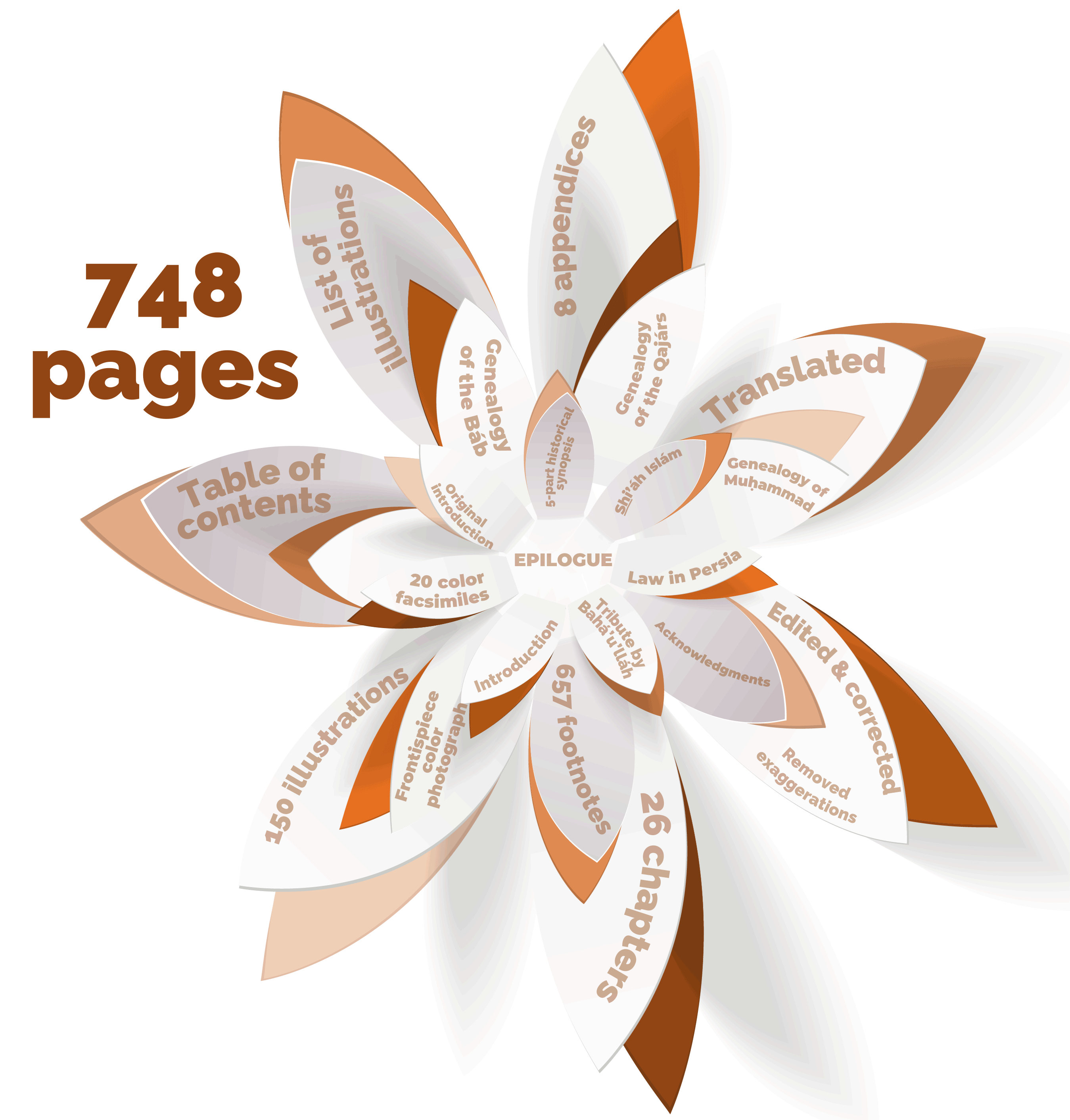

Shoghi Effendi had changed an original Persian manuscript written as a single flowing story into a structured historical work, but he added so much to the original, that it is worth it to enumerate his additions:

- Shoghi Effendi edited and corrected the original manuscript in his role as Interpreter, given that Bahá'u'lláh’s own original corrections had been stolen;

- He removed exaggerations and overstatements;

- 26 Chapters;

- 646 footnotes totaling 200 pages, or one-third of the entire book; two-thirds of the footnotes are in English and one-third are in French; 50% of the footnotes are very elaborate, and several are over 100 lines long;

- 150 illustrations including maps and diagrams and photographs of historic sites in Persia relating to the narrative; the photographs were specially commissioned from an Australian Bahá'í photographer, Effie Baker;

- 20 full-color facsimiles of Tablets to the Letters of Living and to Bahá'u'lláh in the Báb’s own handwriting;

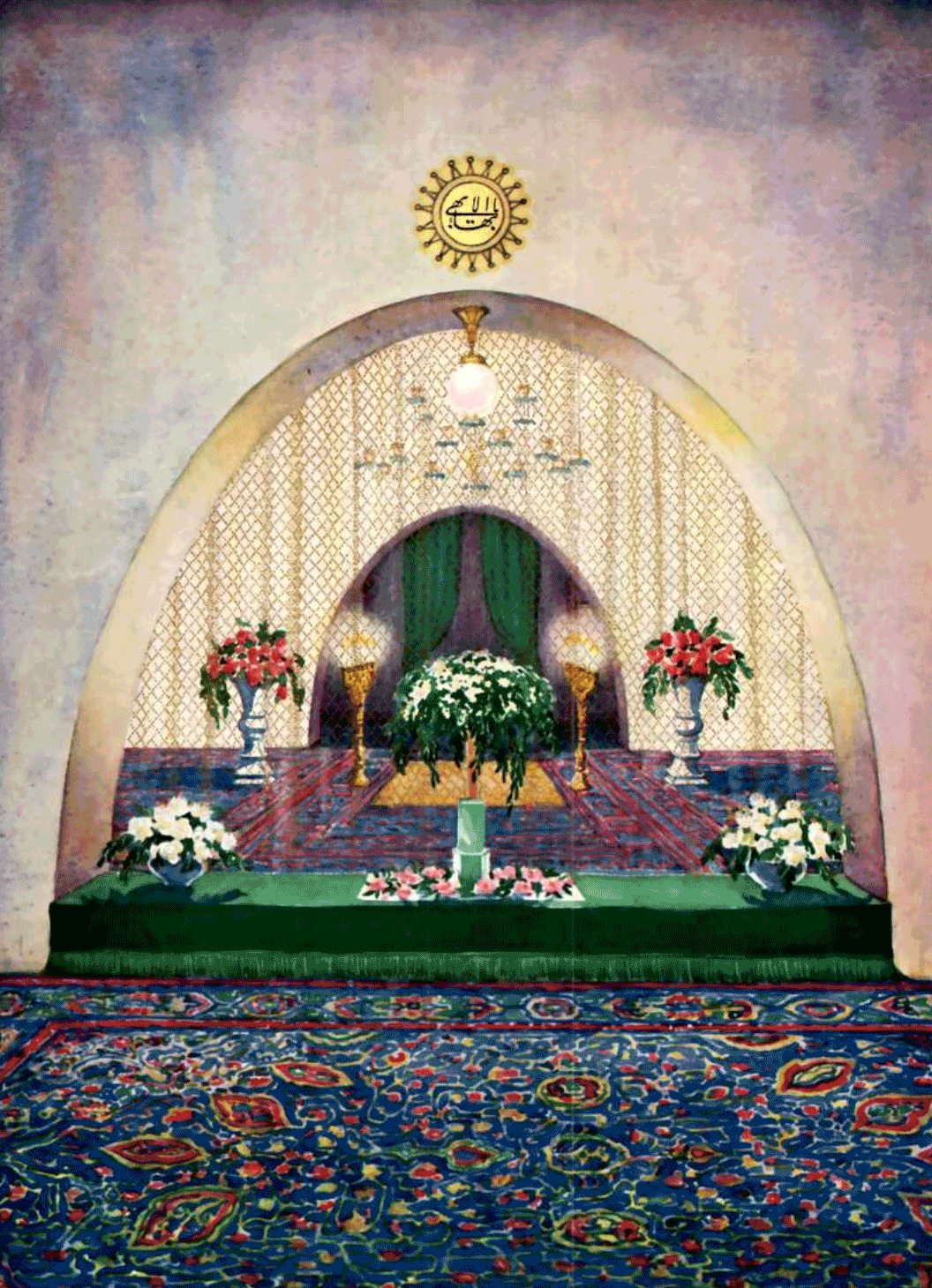

- As the frontispiece, Shoghi Effendi placed a full-color reproduction of the interior of the Shrine of the Báb;

- A table of Contents;

- A list of illustrations;

- George Townshend’s 14-page introduction, which the Guardian not only requested, and inspired, but guided, and provided extensive historical references for; At George Townshend’s request, his name does not appear as author of the introduction;

- A five-part historical synopsis of Persia’s state of decadence in the middle of the nineteenth century excerpted from Lord Curzon’s “Persia and the Persian Question” which includes sections on the Qájár sovereigns, The Persian government, the Persian people, the ecclesiastical order in Persia, and a conclusion;

- A tribute by Bahá’u’lláh’s tribute to the Báb and his chief disciples from the Kitáb-i-Íqán;

- The Distinguishing features of Shí’ah Islám, excerpted from 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s “A Traveller’s Narrative”;

- A genealogy of the prophet Muhammad;

- Theory and administration of law in the middle of the nineteenth century, excerpted from Lord Curzon’s “Persia and the Persian Question”;

- A detailed fold-out genealogy of the Báb drawn in Shoghi Effendi’s own hand;

- A fold-out genealogy of the Qájár Dynasty;

- Acknowledgment;

- The original introductory note to Nabíl-i-A’ẓam’s narrative, dated 1887–8;

- 8 appendices:

- A List of the Báb’s best-known works;

- A list of works Shoghi Effendi consulted; There are 50 titles in this list in English, French, Persian, and Arabic, including 11 authored by Bahá'u'lláh, the Báb, and 'Abdu'l-Bahá;

- Administrative divisions of Persia in the nineteenth century;

- Larger provinces or districts;

- British and Russian envoys to the court of Persia, 1814–1855;

- List of months of the Muhammadan calendar;

- Guide to the pronunciation of the proper names transliterated in the narrative;

- A Glossary;

- An epilogue.

The world now had two masterpieces: one in Persian—Nabíl’s Narrative—and one in English—The Dawn-Breakers: Nabíl’s Narrative of the Early Days of the Bahá’í Revelation.

Hand of the Cause Amatu’l-Bahá Rúḥíyyih Khánum called The Dawn-Breakers “a literary masterpiece and one of [Shoghi Effendi’s] most priceless gifts for all time,” which, she says, “deserves to be counted as a classic among epic narratives in the English tongue,” and this is how she explains its re-creation:

Although ostensibly a translation from the original Persian Shoghi Effendi may be said to have re-created it in English, his translation being comparable to Fitzgerald's rendering of Omar Khayyam's Rubaiyat which gave to the world a poem in a foreign language that in many ways far exceeded the merits of the original.

In the words of Bahíyyih Nákhjávání, the eminent Bahá'í author and daughter of ‘Alí Nakhjavani, Shoghi Effendi “has not only translated and interpreted Nabíl, but re-invented the literature of East and West in the Dawn-Breakers.”

The Guardian had accomplished a literary feat that would reshape Bahá'í identity for untold generations.

Shoghi Effendi absolutely loved Gibbon’s The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Between 1834 and 1836. A painter by the name of Thomas Cole painted a series of 5 paintings called The Course of Empire, depicting the inevitable 5 stages of civilization. This is an homage to the Guardian’s love of Roman history, and of history in general. It is fascinating to read the descriptions of the artist for each of these five stages of civilization, and you can learn more here. The Course of Empire 1: The Savage State he Commencement of Empire by Thomas Cole (1834). Source: Wikimedia Commons. The Course of Empire 2: The Arcadian or Pastoral State by Thomas Cole (1834). Source: Wikimedia Commons. The Course of Empire 3: The Consummation of Empire by Thomas Cole (1836): Destruction. Source: Wikimedia Commons. The Course of Empire 4: Destruction by Thomas Cole (1836). Source: Wikimedia Commons. The Course of Empire 5: Desolation by Thomas Cole (1836). Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Shoghi Effendi’s passion for history began when he was a youth, and he kept that interest throughout his entire life, not just Bahá'í history, but world history, once cabling a relative in Beirut to ascertain the population of Rome in the early days of Christianity.

Night after night at pilgrim dinners in the Western Pilgrim House, Shoghi Effendi would pour out the most exact details of history from early Biblical times to current events, which he kept abreast of with eagerness by reading the newspaper every day, without fault.

Time and again, the Guardian would demonstrate to pilgrims how he interpreted history, the conclusions he came to as they related to his analysis of demography, statistics, nations, races, creeds, traditions, arts, and world events. And he always spoke in very precise terms, with exact figures.

The Guardian’s well of knowledge was not only wide, it was deep. And his thoughts on historical subjects were profound and well-thought-out, and he had spent countless hours learning about the decline and fall of great civilizations, particularly that of the Roman Empire, through reading his favorite writer, Edward Gibbon.

Of course, nowhere was Shoghi Effendi’s knowledge about history more masterful than in the field of Bábí and Bahá'í history. And the link to Ugo Giachery was very clear: Shoghi Effendi had mastered secular history—which he calls pragmatic history—and the Guardian offered up Bahá'í history as the cure to secular history’s ails:

As a master of pragmatic history, he indicates in all his writings the way to correct mankind's errors of the past by applying Bahá'u'lláh's regenerating remedies, and he foretells the difficulties that would result from neglecting to apply these remedies.

The Guardian’s skill as a historian is nowhere more evident than in The Dawn-Breakers: he includes 300 pages of detailed footnotes—his footnotes are so precise, they are beyond academic—as well as summaries of Islam, analyses of 19th century Persia, the genealogy of the Báb. The attention to historical detail is astounding.

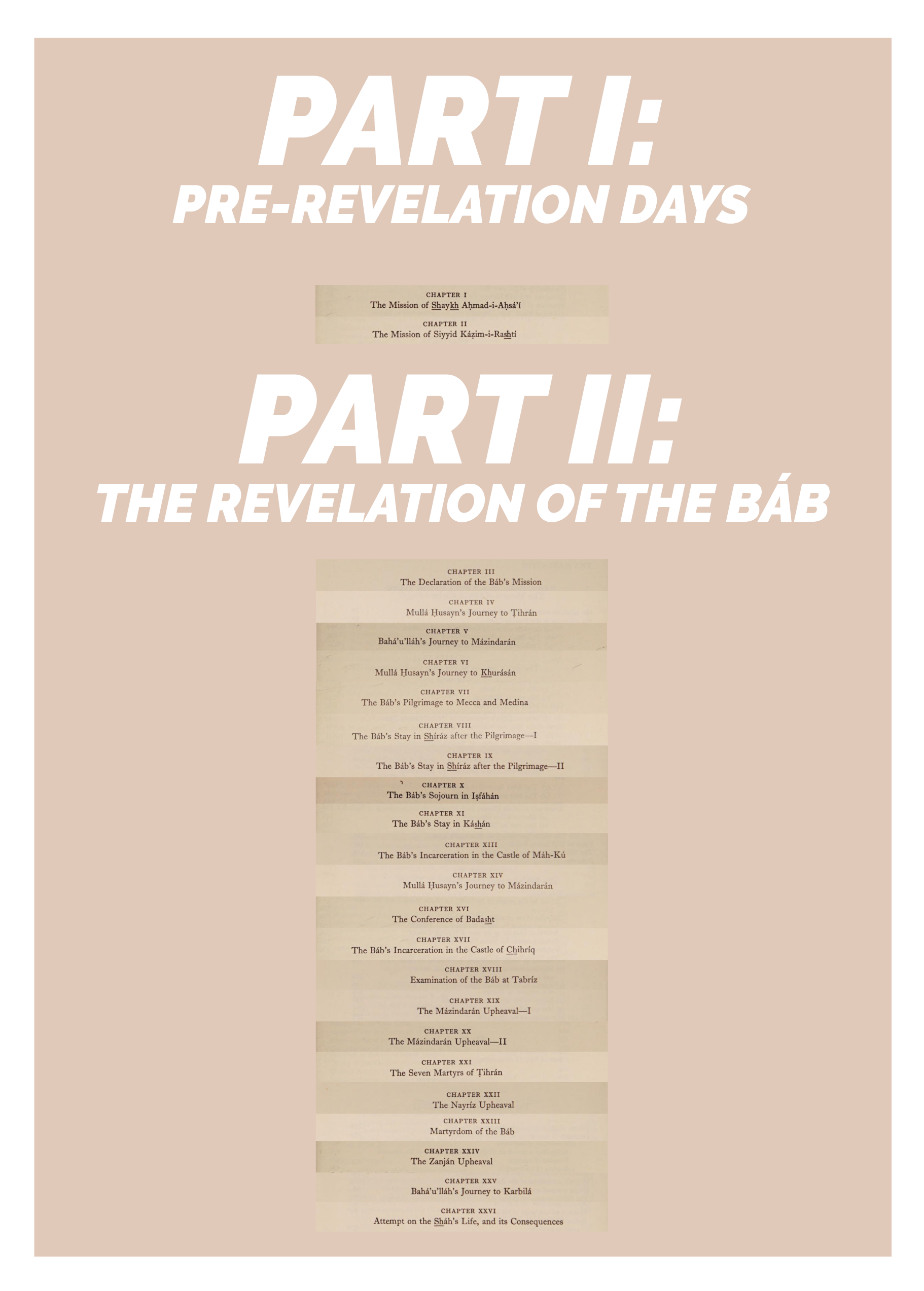

Shoghi Effendi divided The Dawn-Breakers into two parts: he called the first part “Pre-Revelation days” and the second part, “The Revelation of the Báb.”

The first part is short, and comprises just two chapters: one on the life and missions of Shaykh Aḥmad-i-Aḥsá’í and Siyyid Káẓim-i-Rashtí, the heralds of the Báb.

The second part is, essentially, the entire rest of The Dawn-Breakers, i.e. the other 24 chapters.

It may seem basic to address the content of The Dawn-Breakers but, in fact, it is an exercise in marvel at the wealth, and texture of Bahá'í history, and we can always use more amazement.

Graphics from the Chronology The Primal Point: The illustrated chronology of the life and Revelation of the Báb Part 4: The Declaration of the Báb.

In his narrative, Nabíl paints a detailed, ornate picture of the Báb’s childhood and youth, his work as a merchant in Búshihr, his Declaration, His mission, the story of all the Letters of the Living, the Báb’s pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina where He publicly proclaimed His mission at the Kaaba and to the Sherif of Mecca, His return to Shíráz under house arrest, His public proclamation from the pulpit of the Mosque of Vakil, his forced stay in Iṣfahán, in Káshán, and the last three years of His ministry in the two fortresses of Máh-Kú and Chihríq. After this, Nabíl covers the Báb’s examination in Tabriz in detail, and the circumstances leading up to His martyrdom, and the events that followed.

Scattered in a story firmly anchored on the Báb’s life and Revelation, are jewels of inestimable value. We have stories of Ṭáhirih in Iraq, Mullá Ḥusayn’s journey to find Bahá'u'lláh in Ṭihrán relying only on God and his own intuition, his journey to Khurásán, and then to Mázindarán.

There are also heartbreaking chapters of massacres and martyrdoms: the upheavals of Mázindarán (Shaykh Ṭabarsí), Nayríz, and Zanján, the Seven Martyrs of Ṭihrán, the martyrdom of Ṭáhirih, the Bábí holocaust of the summer of 1852.

Nabíl also talks about Bahá'u'lláh in his narrative. In fact, Mírzá Músá, Bahá'u'lláh’s faithful brother was one of Nabíl’s most trustworthy sources, and Nabíl even thanked him in his original introduction. Nabíl provides a great amount of detail regarding Bahá'u'lláh’s instant conversion to the Bábí Faith, how He immediately left home—Ásíyih Khánum and a two-month-old 'Abdu'l-Bahá—to go teach the Faith of the Báb in his home province of Nur in the summer of 1844, Bahá'u'lláh’s three imprisonments in Persia, his torture in Amul, his rescue of Ṭáhirih from Qazvín, His organization of the Conference of Badasht, His 8-month journey to Karbilá between 1851-1852, His return immediately before the attempt on the life of the Sháh by the three misguided and crazed Bábís, His imprisonment in the Síyáh-Chál, His Revelation from God during that imprisonment, His release from prison and His banishment to Baghdád.

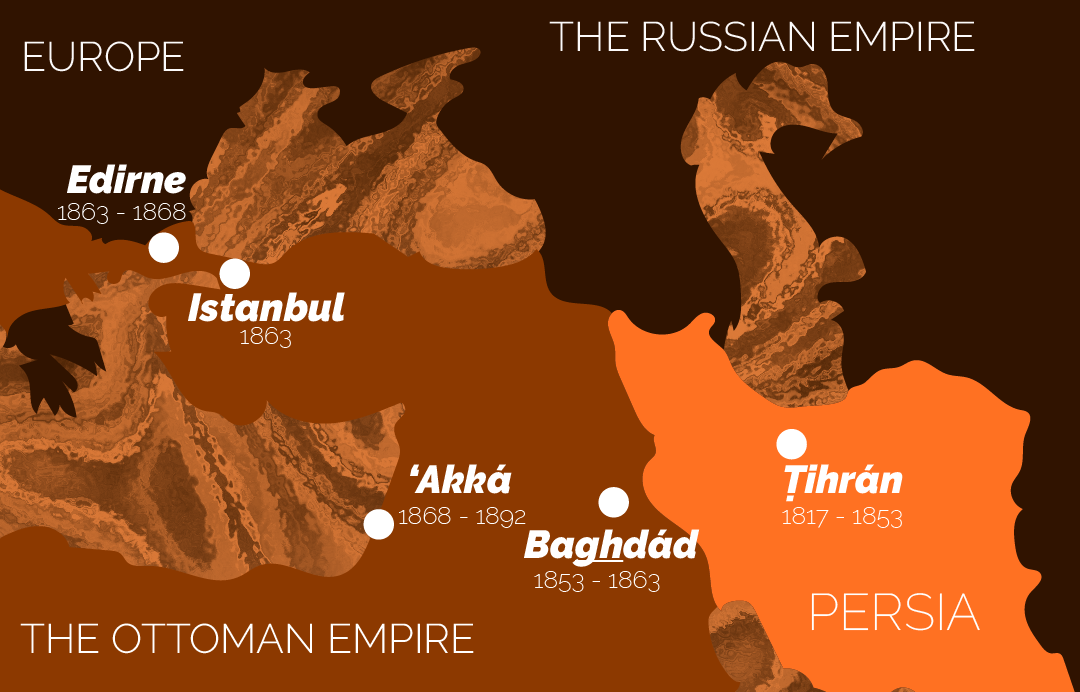

Bahá'u'lláh’s four exiles, the result of Naṣiri'd-Dín Sháh’s exiling Him from His homeland forever, which set in motion the full and perfect execution of God’s Divine Plan for the Dispensation of Bahá'u'lláh.

At the end of The Dawn-Breakers is an Epilogue, in actuality a 17-page statement by the Guardian giving an overview of the Báb’s Ministry, praising the heroes of the Bábí Dispensation, commenting on the apathy of Náṣiri’d-Dín Sháh and his vain and empty hopes of uprooting the Faith. In fact, Naṣiri'd-Dín Sháh’s act of banishing Bahá'u'lláh from His native land forever only furthered the full and perfect execution of God’s design by spreading the Faith to the rest of the world, starting with Iraq, Turkey, and Palestine, in the Ottoman Empire. The Guardian goes on to say that little did Nabíl know that just four decades after he had written his narrative, the Faith of Bahá'u'lláh would have completely encircled the planet.

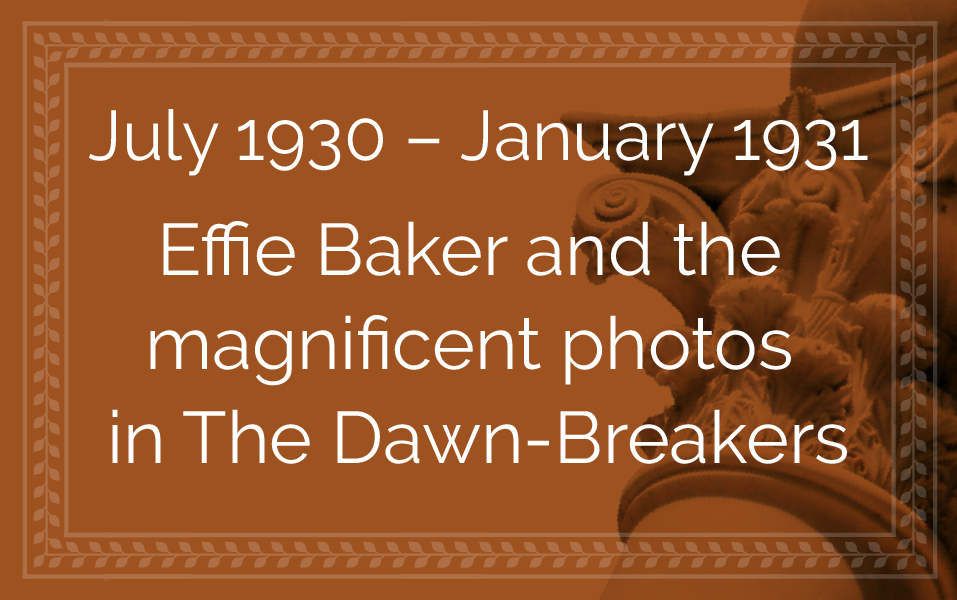

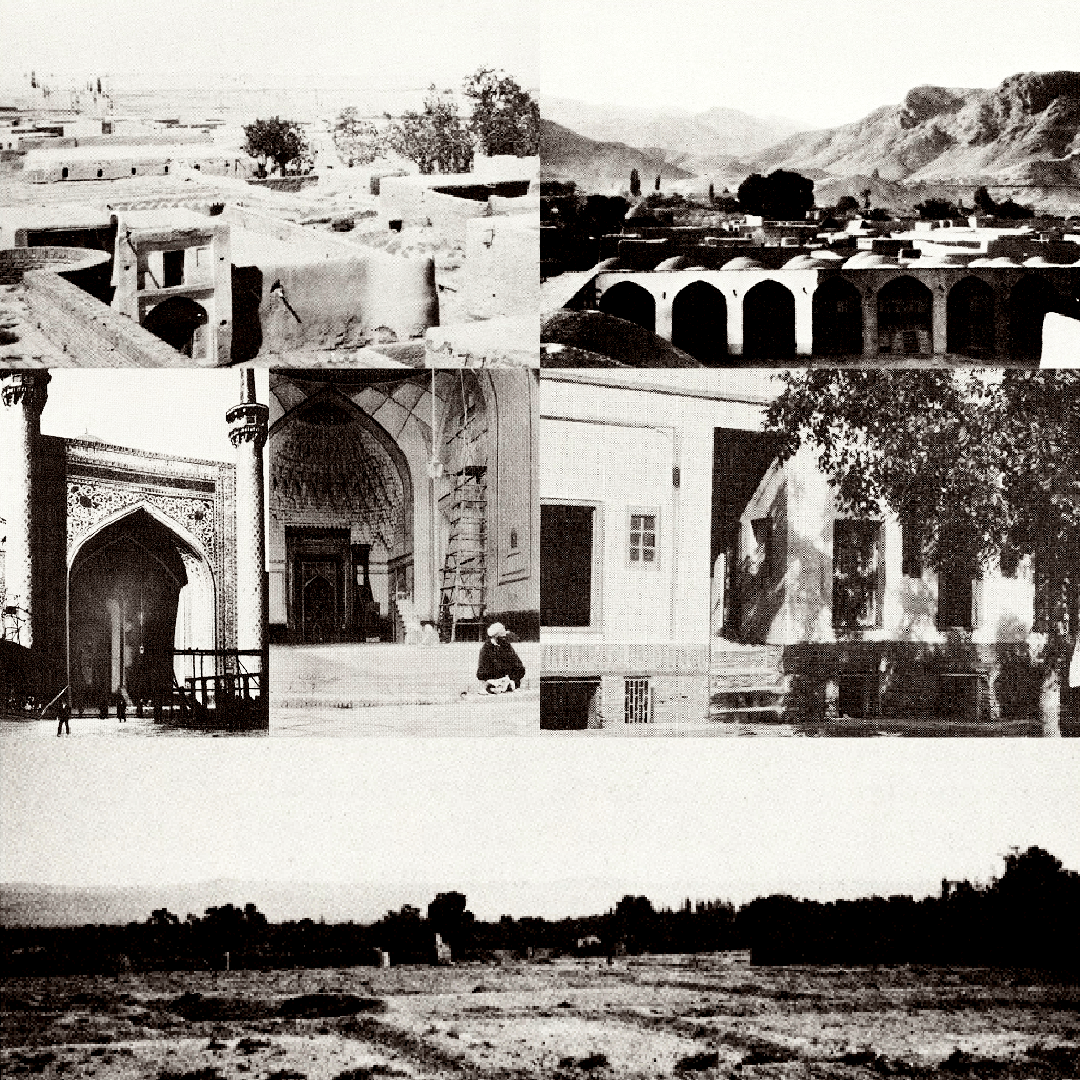

Reza Shah at the TransIranian railway construction site in the late 1920s. These were exactly the types of modernization initiatives that would later destroy Bahá'í Holy and historical sites, and the reason Shoghi Effendi sent Effie Baker on her historic photographic mission to Persia. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Reza Shah initiated modernization in Persia in the 1920s. By 1925, he was modernizing the army, the government, the economy, the judiciary, agriculture, he was secularizing Persia and he was building. He was building 22,000 kilometers of roads and highways.

Shoghi Effendi immediately realized that all the sites associated with the Heroic Age of the Faith in Persia would disappear under concrete and asphalt, and he acted immediately. He asked Persian Bahá’ís to photograph these places, but they were not reactive enough, so the Guardian changed tactics. Instead of asking the Persian Bahá'ís, he asked Effie Baker, an Australian photographer who had been living at the World Center and serving as the hostess to the Western Pilgrim House for six years since 1925..

On 18 July 1930, the Guardian sent Effie to Persia with a very special mission: she was to photograph as many sites as she could which were associated with the Báb, His Life, His family, and His Dispensation, Bahá'u'lláh, the Letters of the Living, the heroes and martyrs of the Cause and all the historic events of the first epoch of the Heroic Age. Shoghi Effendi also asked Effie to photograph as many of the Báb’s relics as she could find.

One of the main reasons the Guardian needed these photographs, other than for their historical and archival importance, was to illustrate and complement his translation of Dawn-Breakers with photographs of the original sites.

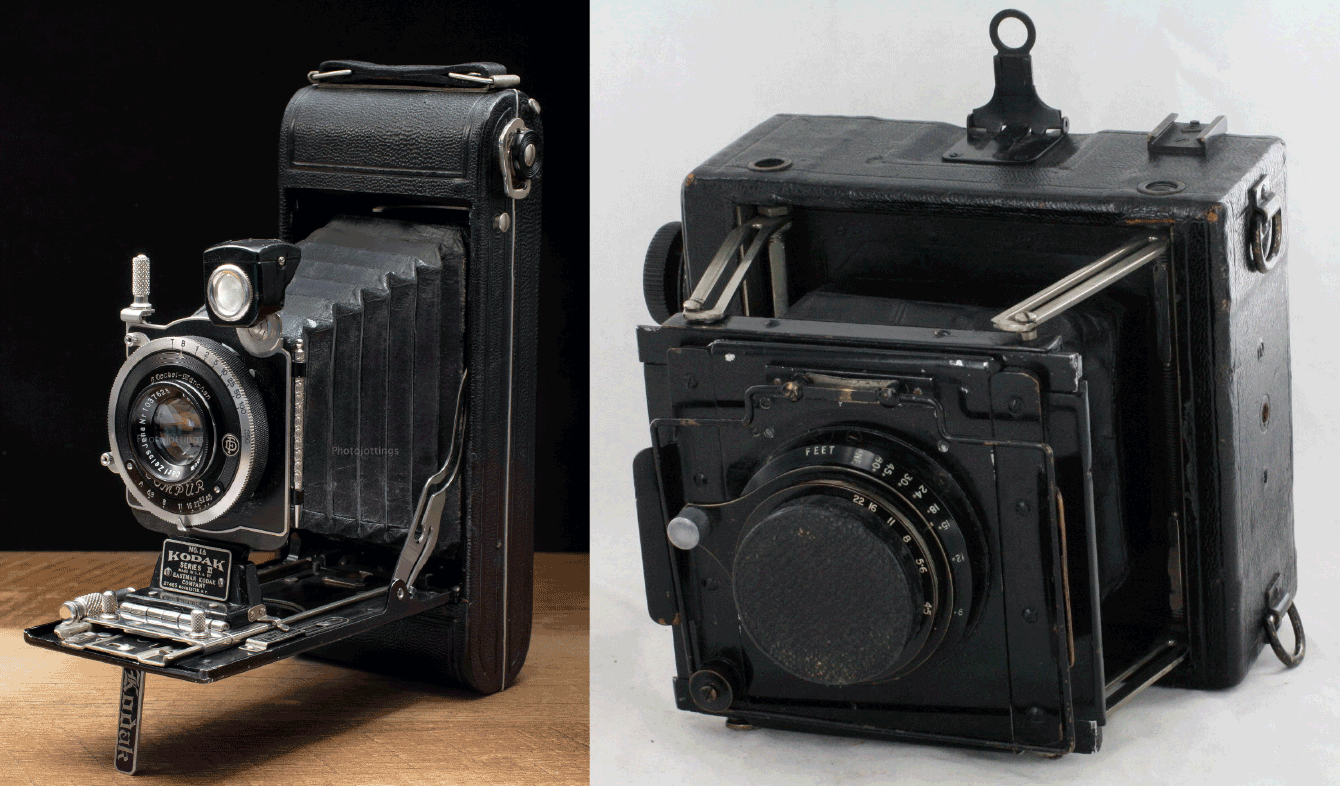

Two models of camera which Effie Baker used to take photographs in Persia. On the left, a No. 1A Autographic Kodak folding camera, and on the right, a Thornton Pickard camera.

Effie Baker left Haifa armed with a No. 1A Autographic Kodak folding camera which was equipped with a wide-angle lens, the perfect type of lens for photographing landscapes, a folding glass half plate camera, perfect for photographic relics, a Thornton Pickard camera and other cameras and equipment securely beside her in an old canvas bag. Faithfully following the Guardian’s very wise advice, she purchased all the film she could find in Haifa. Once Effie arrived in Persia, she found the government had banned the selling of all photographic supplies.

Effie Baker traveled through Syria to Baghdad, where she arrived on 26 July 1930, arrived in Persia and traveled through Kirmánsháh, Hamadan, and arrived in Ṭihrán on 5 August 1930, where she spent two weeks. The next stage of her journey —to the provinces of Persia— would be a very risky journey for Effie Baker on three counts: she was European, she was a woman, and she was a Bahá'í.

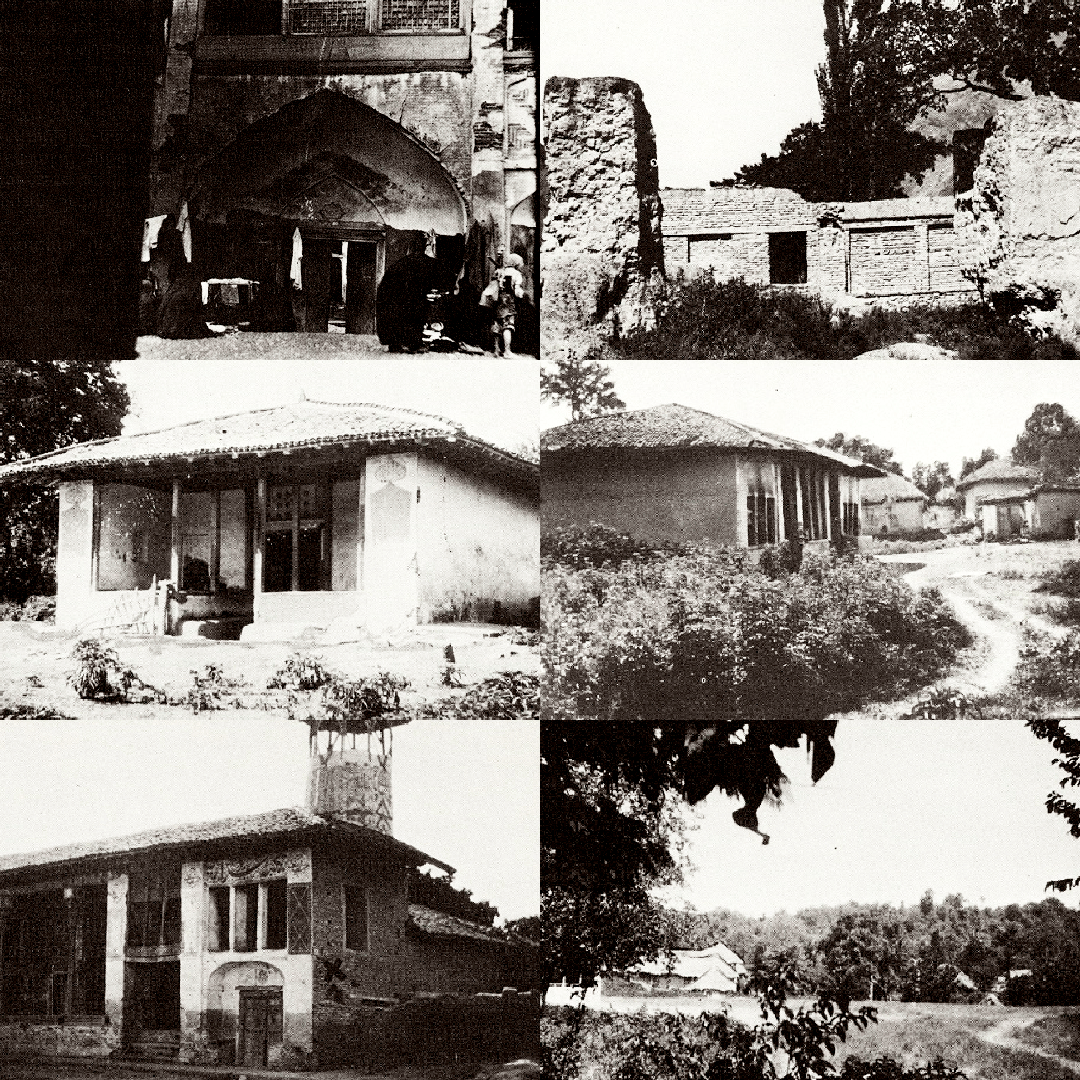

Top left: The resting-place of Quddús. Top right: The ruins of Bahá'u'lláh’s original home in Takúr. Middle left: The Shrine at the Fort of Shaykh Ṭabarsí. Middle right: The village of Afra. Bottom left: The Mosque in Ámul,where Bahá'u'lláh was tortured. Bottom right: The village of Dizva.

Effie Baker began taking photographs for her assignment on 18 August 1930, in Takúr, Mázindarán. In order to make sure her photographs were good, Effie had to develop them at the end of each day, and this, for the entirety of her journey.

On her first journey into the provinces, Effie Baker traveled to Mázindarán and took photos in Sárí Takúr, Dhakala, Amul the resting place of Quddús, the house of the Sa'ídu'l-Ulamá', the house of Quddús' father, Khafagarkolah, villages in between, Fort Ṭabarsí, Mafroosak, back to Ṭihrán

Top left: One of the houses in which Ṭáhirih lived in Qazvín. Top right: Mosque built for Hujjat in Zanján. Midde left: Milán in Ádhirbáyján. Middle right: The Namaz-Khanih of Shaykhu'l-Islám of Tabríz, showing the corner (X) where the Báb was tortured. Bottom left: The Barrack-Square in Tabríz, where the Báb suffered Martyrdom. The pillar on the right marked X is the place from which the Báb was suspended and shot. Bottom right: Site of the old moat that used to surround Tabríz, where the Báb's remains were thrown.

Her second journey led Effie Baker from Ṭihrán to Qazvín, Zanján, and Tabriz, where she photographed the Barrack-Square where the Báb was martyred, the Namáz-Khánih of Shaykhu'l-Islám, where the Báb was tortured, the ruins of the House of Mullá Muhammad-i-Mámáqání, the Mujtahid of Tabriz, views of the city, the prison cell where the Báb was kept, the town of Milán, and she visited Saysán, a blossoming Bahá'í community before returning to Ṭihrán.

Top left: Views of the Village of Miyamay, showing the mosque where Mullá Ḥusayn and his companions prayed. Top right: The village of Sháh-Rud. Middle left: Views of the mosque of Gawhar-Shád in Mashhad, showing the pulpit where Mullá Ḥusayn preached. Middle right: View of the "Bábíyyih" in Mashhad. Bottom: The hamlet of Badasht.

For Effie Baker’s third journey, she traveled to Feerooskov, Damghan, Shahrud, where they found the tree under which Mulla Husayn and his followers camped, then Míyamay, where Effie photographed the Masjid where Mullá Husayn and his companions prayed, and Mashhád, where she photographed the exterior of the “Bábiyyih,” and the Mosque of Gawhar-Shád, where Mullá Ḥusayn preached. After this, Effie visited Sabsuvah, Badasht. Effie was back in Ṭihrán on 1 October 1930 where she stayed 7 days before embarking on her last journey.

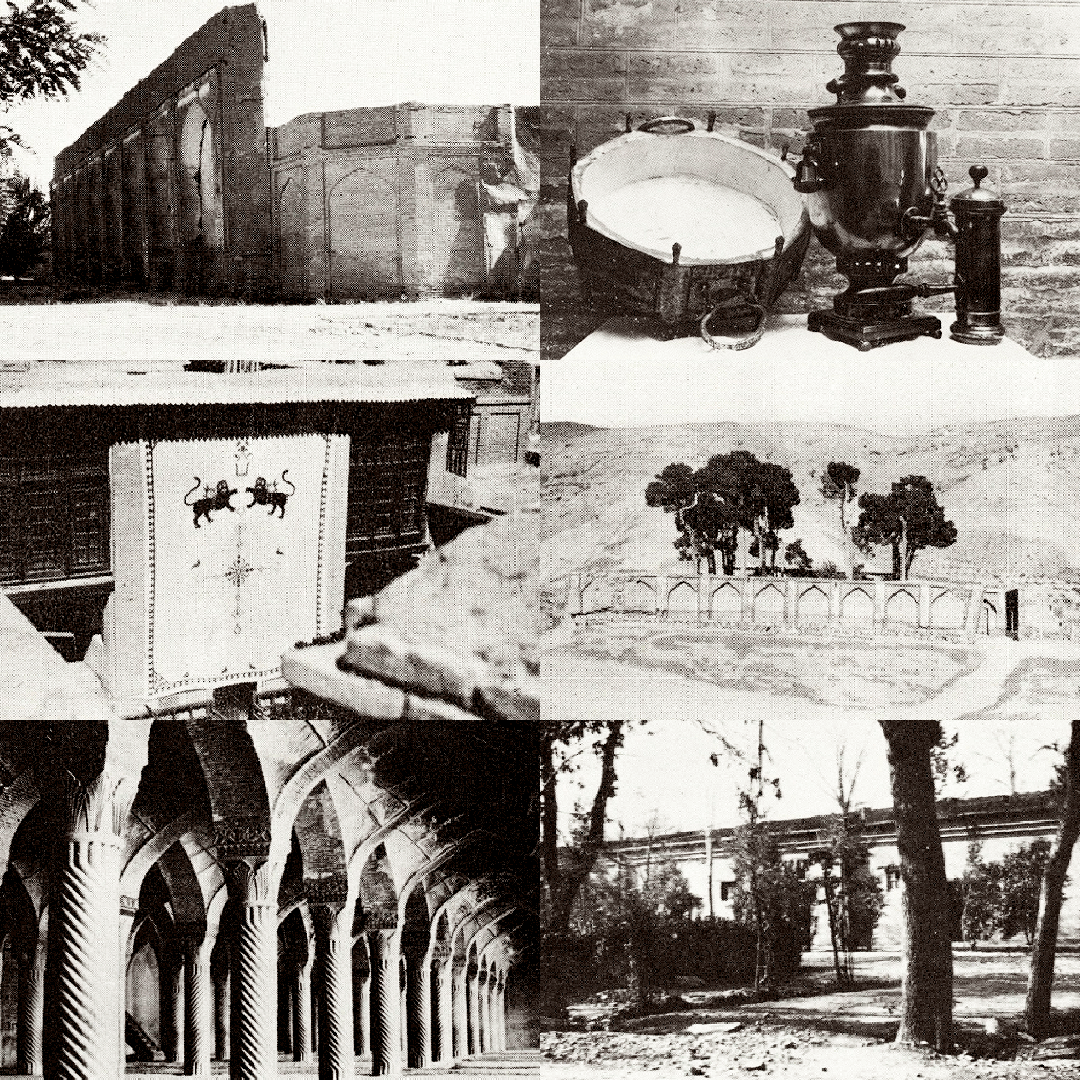

Top left: View of the Imárat-i-Khurshíd in Isfahán, showing ruins of the section the Báb occupied. Top right: The Báb’s brazier and samovar. Middle left: The room in which the Báb was born. Middle right: Outskirts of Shíráz where the Báb often went to walk. Bottom left: The mosque of Vakíl in Shíráz where the Báb addressed the congregation. Bottom right: Site of the garden of Ílkhání where Ṭáhirih was martyred.

Effie's fourth journey through Persia was to the region of Iṣfahán. In Iṣfahán Effie took photographs of the Maydani-Sháh, the homes of the "Beloved of Martyrs" and the “King of Martyrs”; the ruins of the prison where they were incarcerated and killed, and where their bodies were thrown into the square, and the pool and the stone in it, on which their bodies were placed and washed for burial; the house of the 'Imárat-i-Khurshíd, a ruin in which the Báb once stayed, the governor who kept the Báb and protected him in his home; the place known as the "forty pillars" where the mullahs met in conclave to discuss ways and means of condemning and killing the Báb; the Masjidi Shah, House of Vizier Mírzá Asadu’lláh, where the Báb's body was kept; Masjid-i-Jum'ih where he prayed; and a school, the Madrisih Ním-Avard. A short distance from Iṣfahán Effie photographed the Mosque where Jenabi Zain prayed, and the graves of martyrs. Because it was unsafe for her, Mr. Afnán took the picture of the Imam Gomeh's house and the home of “the son of the wolf.”

Effie Baker was in Shíráz from 15 to 20 October 1930, and she photographed the ruins of Persepolis, general view of the city, the Báb’s school, the Masjid-i-Vakíl, where the Báb proclaimed His mission, as well as the house of the Báb, and all its rooms and courtyard and approximately 19 relics belonging to the Báb which were in the ‘Báb’s family’s hands. Obtaining the relics to photograph them was a very arduous process for Effie. Among the relics she photographed were the Báb’s brazier and samovar, His clothing, and His signet ring.

Effie herself wasn’t able to travel to Nayríz for security reasons, but her collaborator, Muhammad Labib, traveled there and took photographs for her. Traveling to Yazd, Effie photographed Vahíd's house and the Fort of Nárín. It was bitterly cold that winter and the car’s radiator went dry so they slept outside.

On 29 November 1930, Effie returned to Ṭihrán, having completed her work in all the cities and villages in the provinces, and began taking her last series of photographs in the capital. For the next two months, she photographed the city’s important mosques and city gates, the house of the Kalantar where Tahirih was confined.

A photograph of Effie Baker taken in the 1920s. Source: The Centenary of the Australian Bahá'í Community.

Shoghi Effendi had been in regular touch with Effie throughout her journey, and by January 1931, he asked her to return to the Holy Land. It was snowing when Effie left Ṭihrán at the end of January 1931, and she travelled for eight days over snow-clad mountains, traveling through Kirmánsháh and Karand, crossing the Iraqi border and found a wonderful surprise upon arrival: the Bahá'ís of Baghdad had obtained all the photos of Bahá'u'lláh’s Most Great House that she needed, so she left the next morning.

On 27 January 1931, at 10:30 PM, after six months away and 16,000 kilometers, Effie Baker arrived in Haifa after having traveled through Tiberias, Cana, Nazareth, and other villages.

Effie had taken 1,000 photographs.

She made three copies of her work: she left one copy with the National Spiritual Assembly of Persia, sent one copy to the Guardian, and sent the third copy to Fujita with the mailing address of the eastern Pilgrim House, and she traveled with the originals back to Haifa, where she arrived, six months after she had embarked on her great adventure, at 10:30 PM on 27 January 1931. Effie spent two full weeks developing her photographs, until about mid-February 1931.

Many of the sites Effie had photographed disappeared over the next decades under the bulldozer of modernization. Had Shoghi Effendi not had the vision of sending her to document all the locations associated with the ministries of the Báb and Bahá'u'lláh, there would have been no photographic trace of early Bahá'í history left on earth.

The Guardian was deeply pleased with Effie Baker’s work, and he asked her and Emogene Hoagg to pick the photographs to be included in The Dawn-Breakers.

Frontispiece of The Dawn-Breakers, personally chosen by Shoghi Effendi. Source: The Dawn-Breakers, Afnán Library.

Shoghi Effendi spent a lot of time thinking and writing about how The Dawn-Breakers should be published. When he sent the manuscript to the Bahá'í Publishing Committee in New York, he described The Dawn-Breakers as a "priceless trust." And it was, indeed, priceless. The Guardian arranged for 20 original Tablets to the Letter of the Living and to Bahá'u'lláh in the Báb’s Own handwriting be facsimiled perfectly, and the pristine copies included in the book.

The Guardian also personally chose the full-color photograph that formed the frontispiece of the book, a colored reproduction of the inner sanctum of the Shrine of the Báb. The Guardian carefully selected the 150 photographs he wished to include in the book, and was extremely explicit about how they should be displayed, as well as what the cover should be like.

Shoghi Effendi had finished with the translation and preparation of the manuscript by March 1931 and sent it to the United States Publishing Committee in New York. By July 1931, the Publishing Committee began the herculean task of preparing The Dawn-Breakers for printing.

It took nearly almost 10 months of painstaking, ceaseless work.

The publication announcement of The Dawn-Breakers on page 8 of Bahá'í News, Issue 67 (October 1932).

Not only was the book was 748 pages long, with 150 photographs interspersed in the text with captions, but it had 20 color facsimiles and a full-color frontispiece. No Bahá'í publication had ever been this ambitious. By early May 1932, The Dawn-Breakers had just come off the press and was almost immediately distributed throughout the world.

The Dawn-Breakers was published with an initial print run of 2,000 copies, bound in green leather, with a dawning sun logo embossed in gold on the front cover. A 300-copy Deluxe edition, signed by Shoghi Effendi, numbered, and bound in Morocco, was published with the general edition. The standard edition of The Dawn-Breakers was sold for $7.50, and the signed edition for $35.00—calculated for today’s inflation, that represents $150 and $790.

The Guardian sent copies of The Dawn-Breakers to numerous eminent personalities, and enthusiastically encouraged all Bahá'ís—and especially Bahá'í youth—to study the book. Every Local Spiritual Assembly librarian in the United States and Canada received a copy of the book, and the National Spiritual Assembly instructed local Bahá'í communities to ensure that The Dawn-Breakers was included in the local public libraries, reducing the price to $5 for them.

On 7 May 1932, the Guardian wrote to Marion Little, the secretary of the Publishing Committee through his secretary, thanking the Committee for its splendid work:

I wish to reaffirm in person the cable I was moved to send to your address expressing my keen appreciation of and profound gratitude for the manner you as well as your collaborators have cooperated in producing such a splendid and impressive edition. It is a striking and abiding evidence of the efficiency and exemplary devotion which characterize your work for the Cause.

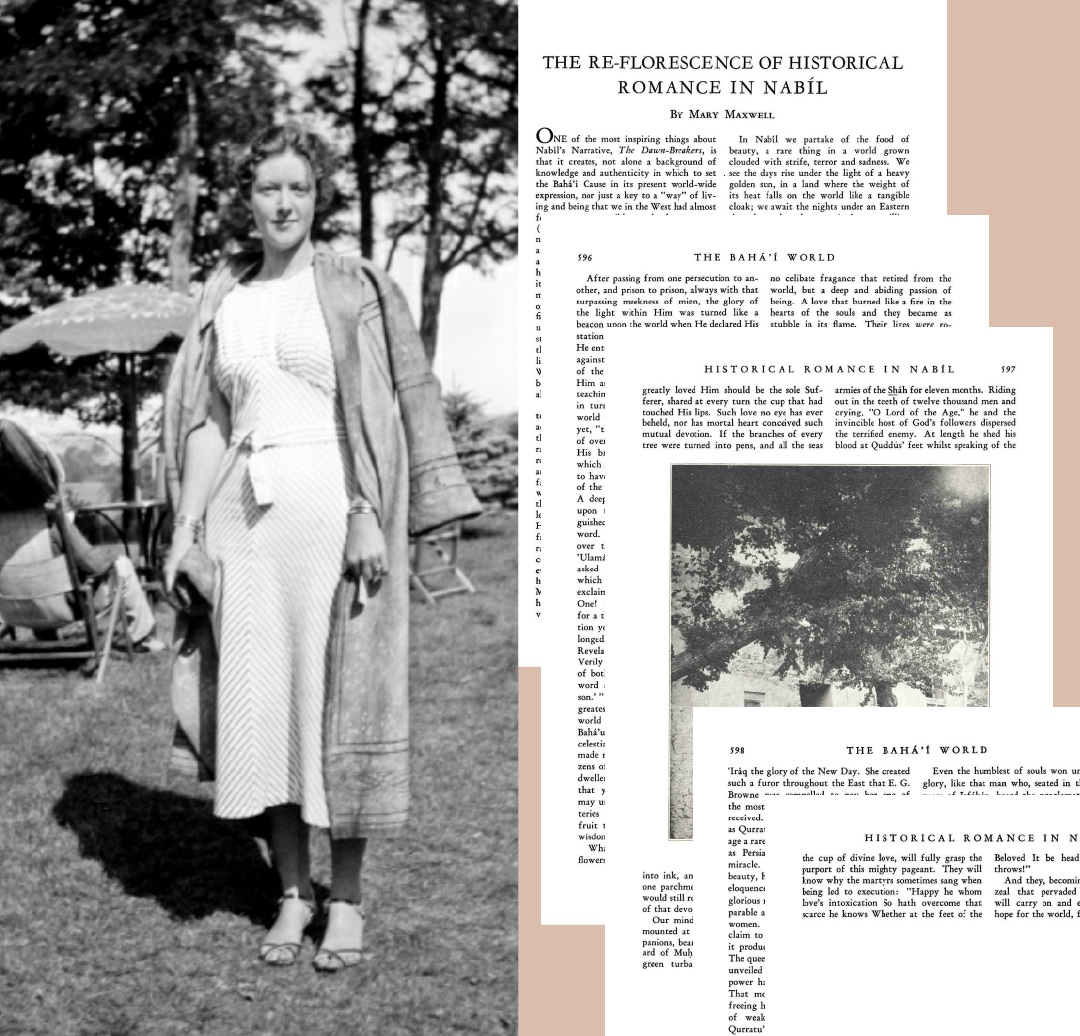

Mary Maxwell’s article in The Bahá'í World about The Dawn-Breakers. Photograph of Mary Maxwell at Green Acre, two years after the article was published. Source: The Maxwells of Montreal: Middle Years 1923-1937 Late Years 1937-1952. Violette Nakhjavani, Kindle Edition, Location 4189.

Before Mary Maxwell married the Guardian and became Amatu’l-Bahá Rúḥíyyih Khánum, she wrote an article called The Re-florescence of Historical Romance in Nabíl that was published in the 1934 edition of The Bahá’í World, when she was between 22 and 24 years old, about 5 years before her marriage to Shoghi Effendi.

This article is fascinating for her insight into the major themes and the long-term value of The Dawn-Breakers, but also because it hits on the heart and soul of the next story, namely the aspect of his translation which mattered the most to Shoghi Effendi: its inspirational value.

And Shoghi Effendi’s future wife mentions what Shoghi Effendi cared the most about as the fourth word in the opening line of her marvelous essay:

One of the most inspiring things about Nabíl’s Narrative, The Dawn-Breakers, is that it creates, not alone a background of knowledge and authenticity in which to set the Bahá’í Cause in its present world-wide expression, nor just a key to a “way” of living and being that we in the West had almost forgotten was possible to the human race, (latent indeed within their seed of humanness), but opens before us a stage which was a nation and an epoch in history, on which a pageant of romance, of adventure and heroism unequaled by any crusade plays itself before us.

The entire essay is a gem. The effect The Dawn-Breakers had on the young woman that would marry the Guardian is palpable. One senses she didn’t just read the book, she absorbed it, inhaled its fragrance, and it changed her. Mary Maxwell speaks with incandescent passion and a breaking heart about its heroes, the dusty roads of Persia, the blood of the martyrs. Mary Maxwell and her essay in The Bahá'í World the living embodiment of everything the Guardian hoped he would accomplish with his two years of back-breaking labors in translating and re-creating The Dawn-Breakers.

Mary Maxwell’s thesis for this essay is that Nabíl’s love for his subject matter, his life-long passion and dedication to recording history is inspirational because it is infused into the facts and events that he tells. It is not just history, it is history told with love, with sacrifice, with enkindlement, with joy, with heart-break, it is truth wrapped like a gift, offered like a gem, told with eloquence and elegance.

It is not secular history.

Over the course of four pages, Mary Maxwell highlights various elements that distinguish The Dawn-Breakers, elevate its content, and contribute to its effectiveness, in essence, these elements are what touched her the most about The Dawn-Breakers.

Nabíl does not dryly state names, dates, peoples, places, and events.

He creates an atmosphere, and infuses beauty into his narrative: the rocky hills and wind-swept plains of Persia appear before the reader’s eyes, Ṭáhirih teaching the Faith from her howdah as she is being extradited to Iraq, every event is told—and brilliantly translated—as if Nabíl was reliving it, and we were there with him.

Nowhere is Nabíl’s skill as a writer and historian more evident than in his descriptions of the Báb and the Letters of the Living. The Báb is so present, so well-described in the pages of this book that the reader begins to know Him, love Him, and believe in Him.

Mary Maxwell is entranced with the language of the Guardian. She quotes at length from The Dawn-Breakers, but almost always quoting dialogue, so real, so vivid, so dynamic, it creates the impression of being present at all these historic occasions, like a fly on the wall.

Towards the end of her essay, Mary Maxwell returns to her original theme, the inspirational quality of The Dawn-Breakers:

The same quality of beauty and majesty pervades all the events chronicled by Nabíl; sincerity is all that is required to become deeply and permanently inspired by the record contained in The Dawn-Breakers, for no heart who loved truth could read its history unmoved and remain unchanged. Here one tastes again those “living waters” that alone can revivify mankind and nurture in him the seed of immortality.

The very last words of Mary Maxwell’s essay promises that those who have truly understood the heart of the message enshrined in The Dawn-Breakers, “becoming fired with that same zeal that pervaded those Dawn- Breakers, will carry on and establish that vision of hope for the world, for which they died.”

It is abundantly clear from the Guardian’s cables and letters regarding The Dawn-Breakers that he considered it, first and foremost a work of inspiration, as he himself explains in the following excerpts from dated letters:

Shoghi Effendi undertook the translation of The Dawn-Breakers only after being convinced that its publication will arouse the friends to greater self-sacrifice and a more determined way of teaching. Otherwise he would not have devoted so much time to it. Reading about the life and activities of those heroic souls is bound to influence our mode of living and the importance we attach to our services in the Cause. Shoghi Effendi therefore hopes that the friends will read, nay rather, study that book, and encourage their young people to do that as well. It is also very important to hold study classes and go deep in the Teachings. A great harm is done by starting to teach without being firmly grounded in the literature. ‘Little knowledge is dangerous' fully applies to the teaching work. The friends should read the Writings and be able to quote from the Tablets when discussing subjects pertaining to the Faith.

(Letter written on behalf of Shoghi Effendi dated 9 May 1932, addressed to Mrs. Edith Hildebrand)

The history of a people is always a source of inspiration to its future generations. Nabíl’s Narrative will operate in the same manner, and remain forever a stimulus to the Bahá’ís.

(Letter dated 16 December 1932)

Shoghi Effendi found great pleasure and spiritual upliftment while working on the translation of Nabíl’s Narrative. The life of those who figure in it is so stirring that everyone who reads those accounts is bound to be affected and impelled to follow their footsteps of sacrifice in the path of Faith. The Guardian believes, therefore, that it should be studied by the friends, especially the youth who need some inspiration to carry them through these troubled days.

(Letter dated 11 March 1933)

The Guardian sincerely hopes and prays that the study of The Dawn-Breakers will inspire the friends to greater activity and more exerted energy in serving the Cause and spreading its message in that town. The life of those heroes of the Faith should teach us what true sacrifice is, and to what extent we should forego our personal and worldly interests while endeavouring to carry the divine message to the four corners of the earth.

(Letter dated 16 April 1933)

He was deeply gratified to learn that the reading of The Dawn-Breakers has deepened your knowledge of the Cause and has inflamed you with new courage and faith. The tale of these immortal heroes of God, so well narrated by the powerful pen of Nabíl, is, indeed, stimulating and spiritually uplifting. It gives the reader a new vision of the Cause and unfolds before his eyes the glory of this new Manifestation in a manner hitherto unknown. Nabíl’s narrative is not merely a narrative; it is a book of meditation. It does not only teach. It actually inspires and incites to action. It quickens and stimulates our dormant energies and makes us soar on a higher plane. It is thus of an invaluable help to the historian as well as to every teacher and expounder of the Cause.

(Letter dated 8 June 1933)