Written and illustrated by Violetta Zein

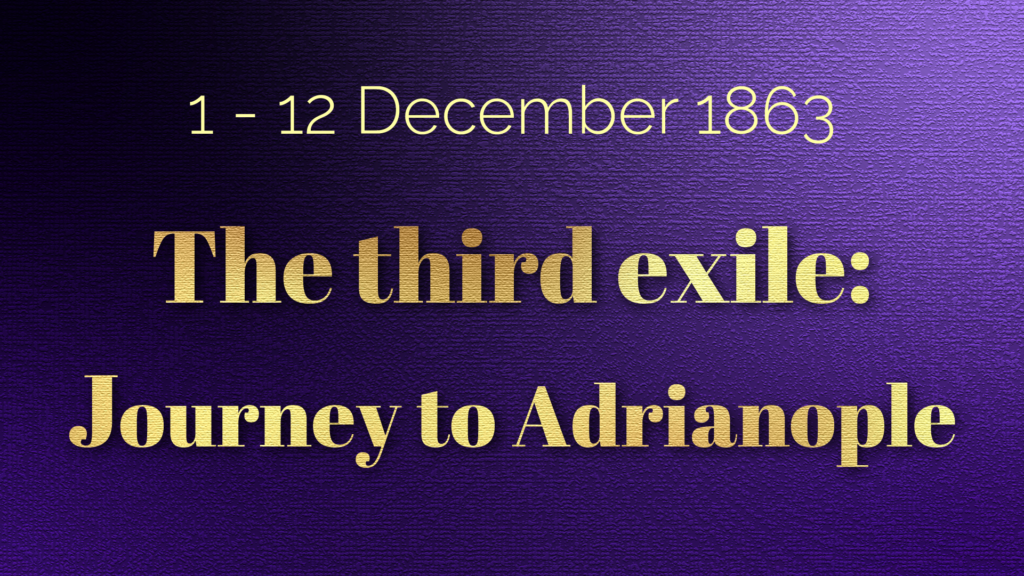

This part covers the life of Bahá’u’lláh from May to December 1863, at the age of 46.

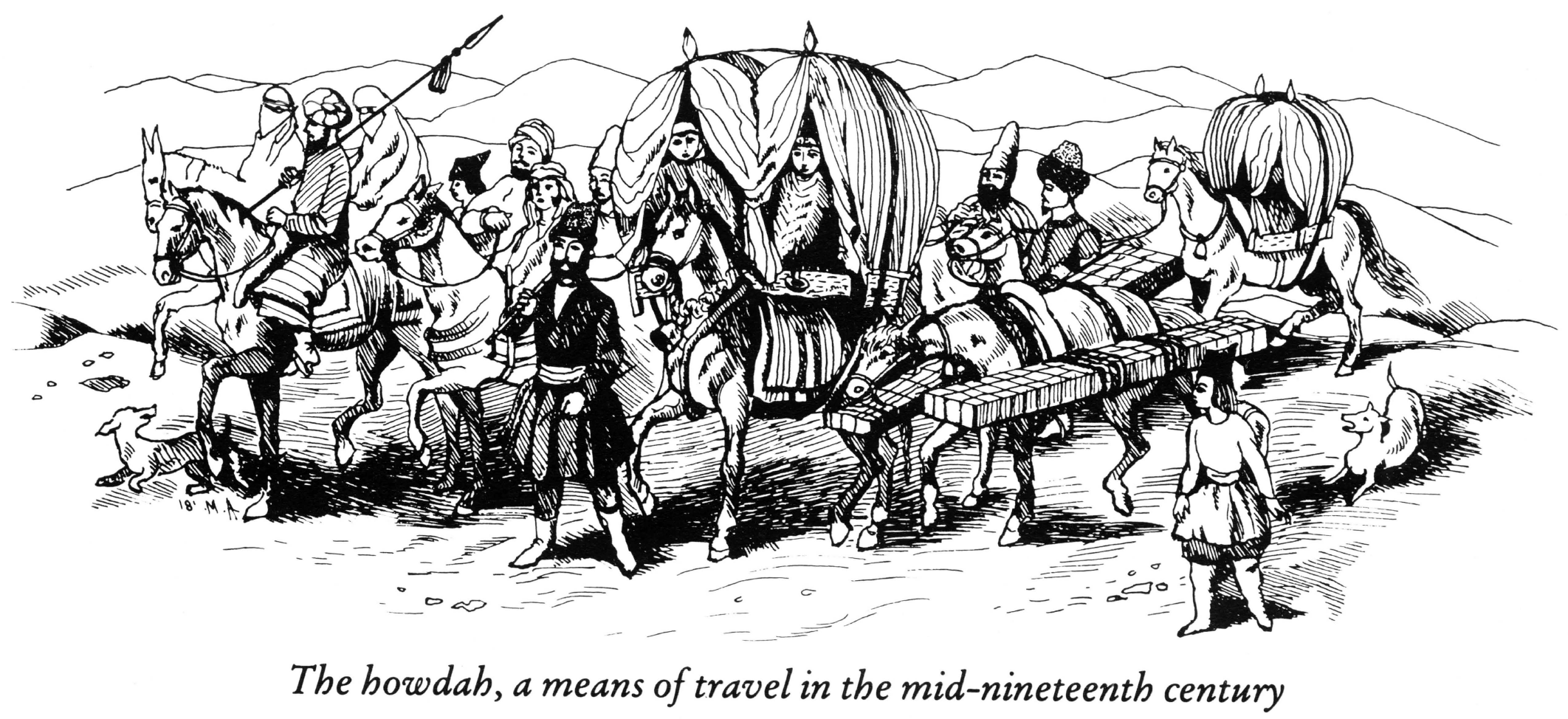

Persian howdah. You can clearly see the cloth covering and the wooden base, as well as the two compartiments seating one person each. There were seven such howdahs in Bahá'u'lláh's caravan. The Dawn-Breakers.

The caravan accompanying Bahá'u'lláh to Constantinople was large. There were 50 mules, ten guards and their officer on horses, nearly 60 animals. There were seven howdas carried on mules, topped by parasols, in which the women and children traveled. Bahá'u'lláh, 'Abdu'l-Bahá, the officers, and some men traveled on horseback, some traveled on mules, but most men walked beside the caravan.

The caravan most often stopped along the banks of Tigris and Euphrates rivers and their tributaries, where they set up their camps and the travelers could bathe, and at times in caravanserais.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 176.

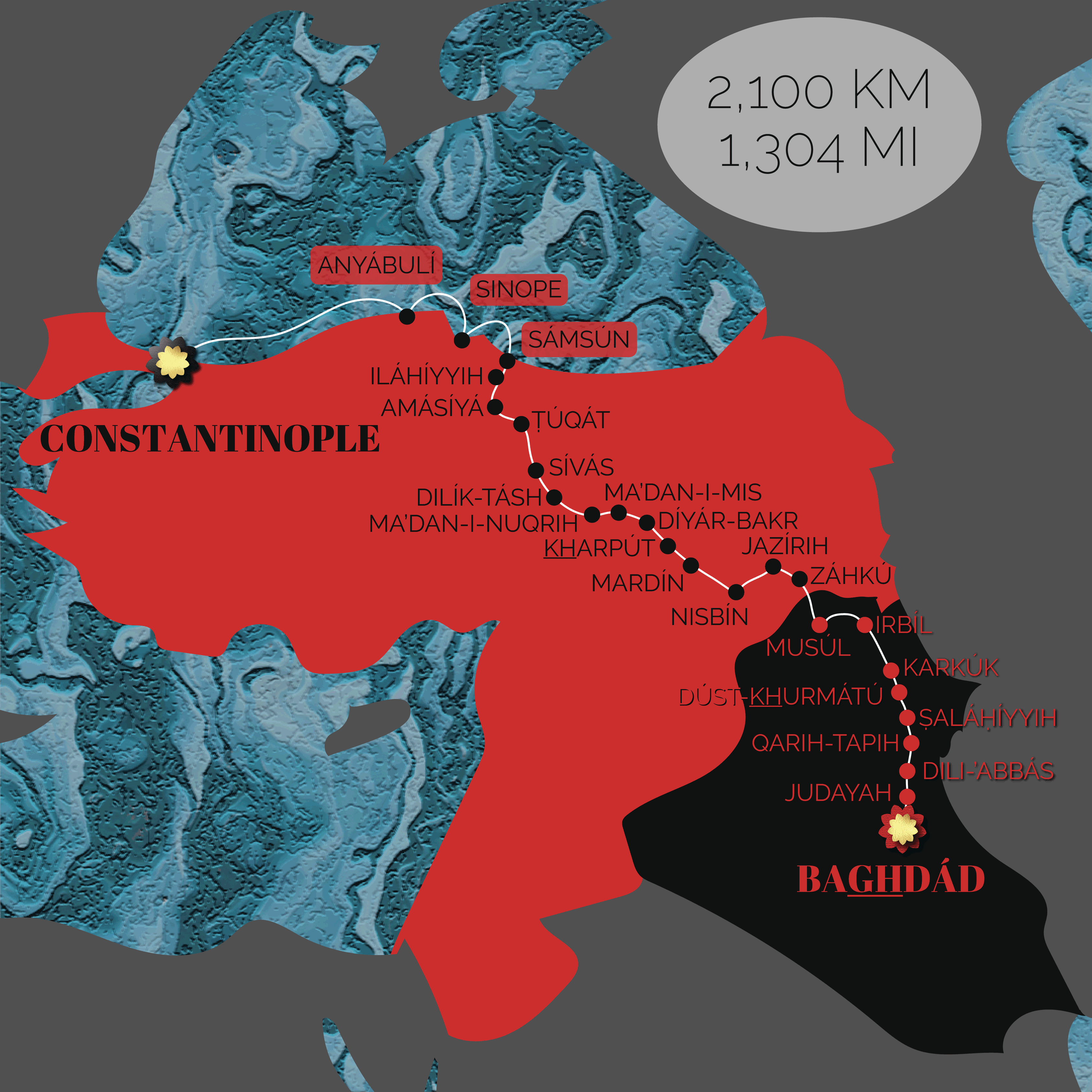

Map indicating only a small fraction of the stops made by Bahá'u'lláh's caravan between Baghdád and Constantinople, from 3 May to 16 August 1863. Source: H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 180. © Violetta Zein.

Two-thirds of Bahá'u'lláh’s journey to Constantinople was overland to Sámsún on the Black Sea, approximately 1,600 kilometers (990 miles) and the last third from Sámsún to Constantinople, or about 800 kilometers (490 miles), was by sea.

The caravan stopped, set up camp, rested, and packed up to continue their march 10 times between Mosul and Kirkúk, a distance of only 173 kilometers (107 miles). On this segment, the caravan only averaged 17 kilometers (10 miles) a day, but they usually covered 40 to 50 kilometers (25 to 30 miles) before setting up camp. Bahá'u'lláh, the Holy Family, and the exiles stopped between 60 and 65 times before Sámsún, repeating this exhausting process over, and over, again for three months over rough terrain in the full heat of the Arabian/Anatolian summer.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 179.

In the absence of a seal of Bahá'u'lláh reading "Mírzá Ḥusayn 'Alí" as in the story below, this is an illuminated seal of Bahá'u'lláh reading "Bahá'u'lláh." Some of Bahá'u'lláh's other seals are beautiful phrases in Arabic. This seal was the most straightforward we found to illustrate this touching list. Source: Bahá'í Sacred Relics.

Before leaving Baghdád, Bahá'u'lláh requested that a list be made for the Ottoman authorities of all the people in the caravan which He sealed with a seal reading "Mírzá Ḥusayn 'Alí," which He used for official documents.

Altogether, 54 people including the members of Bahá'u'lláh’s family accompanied Him to Constantinople. Along the way, one child passed away and two people, Mírzá Yaḥyá and Nabíl, would join the caravan as it traveled. Here is the translated text of that list:

Mírzá Ḥusayn 'Alí [Bahá'u'lláh]: 1

Eldest son: 1

Brothers: 2

Female members of the household: 12;

Children of all ages: 12 (less one who died)

Servants: 20

Others, with their own mules, (who would return): 7

Horses: 6

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868, pages 5-6.

An Arab horse caravan with howdahs, sometime before 1899. Our apologies for the fact the subjects in this painting appear to be warriors, but it is extremely arduous to find images (in the public domain) of howdahs mounted on horses or mules instead of camels and elephants. Painter: Albert Pasini. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Bahá'u'lláh traveled in a dignified and regal manner in His howdah shared with Ásíyih Khánum. Ḥájí Maḥmúd led the mule carrying Bahá'u'lláh’s howdah, and two believers walked on either side. On approach of a village or town, 'Abdu'l-Bahá would bring Bahá'u'lláh His horse, and take His place in the howdah with Ásíyih Khánum, reversing the process when they left a town. Bahá'u'lláh would then ride out to meet the officials and notables who invariably came out to greet Him. Námiq Páshá’s order to welcome Bahá'u'lláh was followed by local government officials all along His route.

In many of the cities and towns where He stopped, Bahá'u'lláh would be met by a delegation before His arrival, and accompanied for some distance by another similar delegation upon His departure. These delegations sometimes comprised válís (Governor), mutiṣarrifs (Administrators of larger divisions), qá’im-maqáms (Deputies representing the Sháh), mudírs (local governors), shaykhs (learned Ṣúfí allowed to teach), muftís (Islamic jurist) and qaḍís (judges), judges and other local government officials.

In some places, villagers organized festivities in His honor, prepared food, and made sure Bahá'u'lláh was comfortable, showing Him great reverence. The local inhabitants who saw Bahá'u'lláh travel stated they had never witnessed anyone like Him, majestic in His journey, generous with His bounty, and hospitable to all.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 176.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868, page 6.

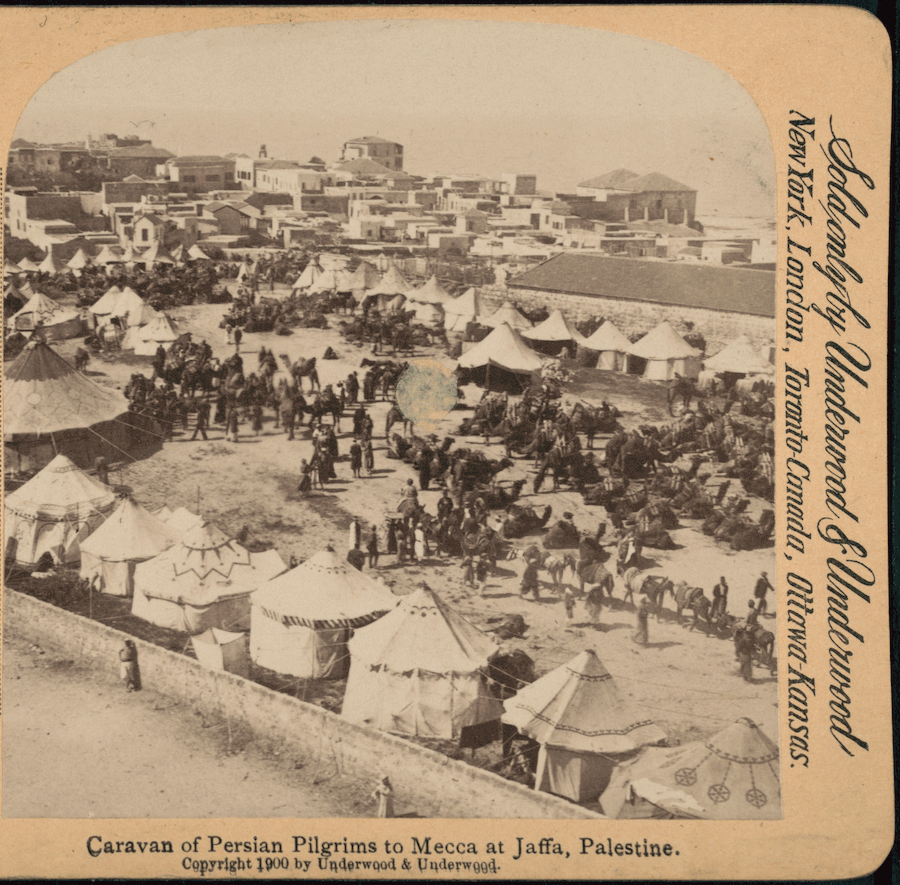

Caravan of Persian pilgrims to Mecca at Jaffa, Palestine, J.F. Jarvis, publishers, c1900. This photograph gives a good idea of the number of animals (though there were horses and no camels in the Holy Family's caravan) a few decades after the Holy Family's long exile. Library of Congress.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá was by now a handsome, gracious young man of nineteen years old, capable, firm, zealous, generous to all, and utterly devoted to Bahá'u'lláh. He made the arrangements for the difficult journey across ‘Iráq and Anatolia, was in constant attendance to Bahá'u'lláh for His every need, riding by Him the entire day, and was always the first one to reach the camp to see to the comfort of the travelers.

'Abdu'l-Bahá was the self-appointed “head of the commissariat department,” which meant that after an arduous day of riding, as soon everyone had settled down for the night, 'Abdu'l-Bahá went door to door in Arab and Kurd villages or camps, convincing them to sell him enough food for 60 animals and 72 people. 'Abdu'l-Bahá later said: “I always first thought about the feed for the animals.” Without healthy animals, the caravan would not go far.

When the provisions were scarce, or when they traveled through famine-stricken areas, 'Abdu'l-Bahá sometimes spent the whole night in search of food. Returning to camp with provisions, 'Abdu'l-Bahá was at times so exhausted He could no longer stand on His feet, but He still supervised the fair distribution of fodder among the animals, and would often go to sleep without having eaten anything.

'Abdu'l-Bahá rode a fine, very spirited Arabian horse who helped Him catch short naps through the journey: 'Abdu'l-Bahá would ride swiftly ahead of the caravan, and the horse would lie on the ground letting 'Abdu'l-Bahá take short naps, resting His head on the horse's neck. When the caravan approached, the horse would stir, waking 'Abdu'l-Bahá, who would then remount

Star of the West,Volume XIII, No. 10, pp. 277–278. “Exiled From Bagdad: A story from the words of Abdul Baha” by Mirza Ahmad Sohrab.

Myron H. Phelps, The Master in ‘Akká, page 41.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 179.

Balyuzi, H.M. 'Abdu'l-Bahá: The Centre of the Covenant of Bahá'u'lláh, page 17.

The Diary of Ahmad Sohrab, 26 April 1913, pages 19-22.

Of all the people mentioned below, we were only able to find six photographs. Photo 1: Mírzá Áqá Ján, Bahá'u'lláh's amanuensis and personal attendant. Photo 2: Áqá Riḍá, cook for the caravan. Photo 3: Mírzá Maḥmúd-i-Káshání, cook for the caravan. Photo 4: Áqá 'Abdu'l-Ghaffár, interpreter for the caravan. Photo 5: Ustád Muḥammad-'Alíy-i-Salmání, Bahá'u'lláh's barber, in charge of supplies and the howdah of the wife of Mírzá Yaḥyá. Photo 6: Áqá Ḥusayn Áshchí, a young boy, apprentice cook, porridge cook, and attendant to the ladies of the caravan.

The journey to Constantinople was a logistically complex endeavor with many people and many animals, who all had to be fed and cared for, traveling thousands of kilometers in harsh terrain. For this journey to be a success, everyone had a role to play.

Mírzá Áqá Ján (Photo 1) and Mírzá Áqáy-i-Munír were Bahá'u'lláh’s personal attendants. When they traveled at night, Mírzá Áqáy-i-Munír walked in front of Bahá'u'lláh's howdah with a lantern, and during the day, when walking besides the howdah, he would chant beautiful poems by Ḥáfiẓ.

Áqá 'Abdu'l-Ghaffár (Photo 4) a trader from Iṣfahán was the only fluent Turkish-speaker and made contacts along the journey, serving as an interpreter for everyone.

Áqá Riḍá (Photo 2) and Mírzá Maḥmúd-i-Káshání (Photo 3) were the cooks of the caravan. During the day, Áqá Riḍá and Mírzá Maḥmúd guided the horses carrying Bahá'u'lláh’s howdah, cooking the meal as soon as the caravan halted, They served everyone, washed the dishes and packed them up. 'Abdu'l-Bahá said that by that point, they were so tired, they could have slept on a hard boulder. In the morning, they had to be shaken awake, but still, they chanted prayers during the day, and they were sometimes so exhausted that they sleepwalked.

Áqá Muḥammad-Ibráhím-i-Amír and Áqá Najaf-'Alí were responsible for pitching the tents and for the security of the camp.

Darvísh Ṣidq-'Alí, Siyyid Ḥusayn-i-Kashí and Ḥájí Ibráhím groomed the horses, and Siyyid Ḥusayn was in charge of Namíq Páshá's horse.

Uthmán was the muleteer.

Áqá Muḥammad-'Alíy-i-Jilawdár was in charge of the fodder and barley for the animals.

Mírzá Ja'far-i-Yazdí, often accompanied 'Abdu'l-Bahá to the surrounding villages and purchase straw and provisions for the mules and horses.

Áqá Muḥammad-Ibráhím-i-Náẓir, and Mírzá Ja'far were responsible for the purchase of anything that was needed along the journey.

Ustád Muḥammad-'Alíy-i-Salmání (Photo 5) was Bahá'u'lláh’s barber, and also kept watch over the tents and all the belongings of the caravan, was in charge in charge of supplies, and with whatever article anyone needed, always ensuring the items were returned, but perhaps his most difficult responsibility was being in charge of the howdah belonging to Mírzá Yaḥyá's wife, a difficult and quarrelsome woman.

Áqá Muḥammad-Báqir-i-Maḥallátí was in charge of providing coffee and water pipes.

Two brothers from Káshán, Ustád Báqir and Ustád Muḥammad-Isma'íl, the tailors who had sewn the clothes for the journey, were in charge of the tea and the samovar.

Áqá Ḥusayn Áshchí, (Photo 6)a young boy, was the apprentice cook, and he also served the ladies of the caravan and was the porridge cook, his last name, Áshchí, means maker of broths.

Another young boy, Áqá Muḥammad-Ḥasan, also served the ladies.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 175, 176-177, 178-179, 186, and 192.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 1: Baghdád 1853 - 1863, pages 289-291.

Ustád Muḥammad-'Alíy-i-Salmání, the Barber, My Memories of Bahá'u'lláh, pages 25-26 and 31.

'Abdu'l-Bahá, Memorials of the Faithful: Jináb-i-Muníb, upon him be the Glory of the All-Glorious.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, Addendum V: Mírzá Áqáy-i-Munír (Jináb-i-Muníb), page 479.

A black Arabian horse named Behim in Constantinople, around 7 to 10 years after Bahá'u'lláh granted Námiq Páshá's request and accepted to bring his son's gift, a prize horse, to Constantinople. Photograph by Abdullah Frères 1880/1893. Library of Congress.

Námiq Páshá had asked Bahá'u'lláh in the Garden of Riḍván if he could send a horse for his son in Constantinople, with the caravan. Bahá'u'lláh had agreed and the horse traveled with the exiles, cared for by Siyyid Ḥusayn-i-Kashí, a kind and simple man full of jest and humor. He was so funny that he used to dance and caper about in front of Bahá'u'lláh’s horse. One day along the route, Siyyid Ḥusayn-i-Kashí went to Bahá'u'lláh to complain that 'Abdu'l-Bahá gave enough barley and fodder to the other animals, but didn't give him any for Námiq Páshá's horse, but when 'Abdu'l-Bahá entered the tent, he ran off.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 168-169 and 175.

This is a 1851/1852 photograph of an encamped tent in Egypt, headed for the Sennar, by Félix Teynard, a French photographer. The tents in the background help us form an image of the kind of tent Bahá'u'lláh and His Family were in when He cooked this sweet dish for His loved ones. Source: The Met.

One day, after a long and cold march, 'Abdu'l-Bahá found bread, rice and milk and Bahá'u'lláh used the ingredients to prepare a sort of rice pudding for His family, by boiling the ingredients together with some sugar. This was a dish Bahá'u'lláh had sometimes made for Himself during His seclusion on Sar-Galú, the only time he ate warm food.

Myron H. Phelps, The Master in ‘Akká, page 41.

Firayját is no longer a place that can be found on any map, nor is there any indication online of its contemporary name, if it has one. But this 1932 photograph by the American Colony (Jerusalem) is of the banks of the Tigris river around Baghdád, which is the setting for the first stop made by Bahá'u'lláh in His long march to Constantinople. Source: Library of Congress.

Bahá'u'lláh, His Family and their fellow-exiles reached Firayját, five kilometers (three miles) away from Baghdád as the sun was setting on 3 May 1863. Firayját was on the banks of the Tigris River, and boasted the large mansion of the ex-Valí of Baghdád, Dawúd Páshá and a verdant garden. Bahá’u’lláh stayed in the mansion in Firayját for seven days while Mírzá Músá finished tidying up their affairs in the capital, and packing and loading the remainder of their possessions.

While they were in Firayját, the horses were made to run a course to test their fitness for the journey, and everyone witnessed Bahá'u'lláh’s excellent horsemanship. Bahá'u'lláh had three horses for the long journey, the first one, which He had ridden out of Baghdád when He left the Garden of Riḍván, was a red roan stallion named Saú’dí, and the other two were named Farangí and Sa’íd.

'Abdu'l-Bahá had a wild and spirited Arab horse to ride, and there were also two donkeys for Him and Mírzá Mihdí to ride occasionally. While they stayed in Firayját, people streamed in daily from Baghdád, finding the separation from Bahá'u'lláh to be unbearable,

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 176.

Myron Phelps, The Master in ‘Akká, page 41.

An almost-contemporary photograph of the Arabs Bahá'u'lláh loved so much, and to whom He pays tribute to in the Lawḥ-i-Firayját. 1873 studio portrait by Pascal Sébah of three ‘Iráqí Arabs wearing traditional clothing of the Baghdád region from left to right: a Shammar Arab, an Arab Muslim woman of Baghdád, and a Zubaid Arab. This photograph is plate XXXVIII in the book Les costumes populaires de la Turquie en 1873. Source : Library of Congress. Background created from cutouts from one of the illustrations of al-Hariri's Maqamat by Yahya ibn Mahmud al-Wasiti, an influential 13th century ‘Iráqí painter and calligrapher. Source: Wikimedia Commons. © Violetta Zein.

On 9 May 1863, the day Bahá'u'lláh left Firayját, He marked the occasion by revealing a particularly significant Tablet in Arabic which is not well-known outside of ‘Iráq called the Lawḥ-i-Firayját (Tablet of Firayját).

That day was the day Bahá'u'lláh left ‘Iráq and its people forever, the Arabs whom He had loved and taught for ten years, the first Bahá'ís in history, the ones who had been streaming through His house, the garden of Riḍván, and every stop along the way to Firayját because they could not bear to be separated from Him.

In this Tablet, Bahá'u'lláh speaks of His departure as “this time when the accents of the dove of separation are raised from the land of 'Iráq,” begs God to send down upon Him every affliction intended for His loved ones, so that nothing could ever dampen their devotion, and implores God to “preserve Thy loved ones after I am gone,” to gather and sever them from all attachment, so they may “stand in fear of no one,” to open their eyes, allowing them to ascend to the station of a true believer, speaking praises of God continually, and return to God so completely that “naught could cause them any perturbation.”

To listen to a captivating chant of this very Tablet by singer Kawakib Hussein, click on the graphic below:

© VZ graphic with border created from cutout repeated detail from an illustration by Yahya ibn Mahmud al-Wasiti. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Partial Inventory ID: BH02467

Bahá'u'lláh, Lawḥ-i-Firayját on Bahá'í Library Online.

1950/1977 aerial color slide of the Tigris River in Iraq (ancient Babylon) showing palm groves on its banks. This is an ideal photograph to keep in mind, as Bahá'u'lláh’s caravan follows the course of rivers and streams, and we can see in this photograph that there are variegated landscapes along the course of the river. The photographer added a Bible verse reference to the description of the image: “Psalm 137”. Here is what this Psalm reads: “ By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down, yea, we wept, when we remembered Zion.” Photographer: Matson Photo Service. Source: Library of Congress.

Leaving Firayját on 9 May 1863, the caravan followed the banks of the Tigris, reaching Judayah in the late afternoon that same day. There was no garden there, but they raised tents and stayed for three days. While they were in Judaydah, more believers joined the exiles. Sháṭir-Riḍá brought with him Áqá Muḥammad-Ḥasan, a young boy whose father would soon be martyred. Áqá Muḥammad-Ḥasan would be raised in Bahá'u'lláh’s home and would serve Him faithfully until his death in extreme old age.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 177-178.

A verdant portion of the Sirwan River which flows from Iran, and throws itself into the Tigris River. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

After leaving Judaydah on 12 May 1863, the caravan made its way to Dilí-‘Abbás, in a verdant plain by the River Tigris, where they pitched tents, then left at midnight and traveled by night because of the brutal summer sun, arriving in Qarih-Tapih later that day, then continuing on to Ṣaláḥíyyih, a small town beside a mountain, situated on a tributary of the river Diyáláh.

The Qá'im-maqám and other notables of Ṣaláḥíyyih came out to greet the caravan and offer their respects, then held a festival in honor of Bahá’u’lláh. The caravan stayed in Ṣaláḥíyyih for two nights, and the officials of the town provided nightly watches against highwaymen.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 181.

A rare image of a caravan in Mesopotamia (Iraq) with mules and horses, like Bahá'u'lláh's caravan. This one features a double-cabin howdah on a mule in the foreground. Source.

The caravan left Ṣaláḥíyyih on the third night, pressing on in the darkness, despite hurricane-level winds. This was a night when poor Áqá Riḍá, the faithful cook, had a very frightening experience. Áqá Riḍá, one of the cooks, sat down and fell asleep for five hours. When he woke up, the caravan was gone!

By dawn, he had found the caravan again, occupied with morning tea and dawn prayers. Mírzá Músá told him they had just noticed his absence and were about to send some men out looking for him. It was common at the time, when caravans journeyed at night, that travelers would get lost, and this happened more then once during Bahá'u'lláh’s long march to Constantinople.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 181.

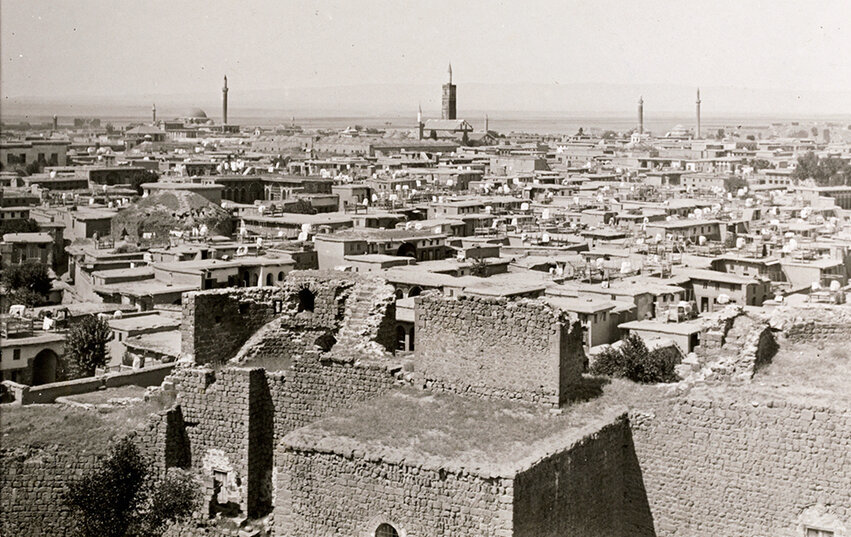

1932 photograph of the city of Karkúk, with a caravanserai (inn for travelers with pack animals) in the foreground. Photographer: American Colony (Jerusalem). Source: Library of Congress.

Later that morning, the caravan reached Dúst-Khurmátú and camped under a small grove of trees, traveling by night again and reaching Táwuq, by a hillside, where a small river flowed, and continued on their way to Karkúk, where they stayed in an orchard outside the city for two days.

In Karkúk, notables came out to welcome Bahá'u'lláh. The caravan had now entered Kurdish territory, a culture Bahá'u'lláh knew very well from His time in Sulaymáníyyih, and when a man arrived towards Him, shouting in a state of exaltation, Bahá'u'lláh stopped His followers from intervening.

Karkúk was the largest town in Lower Kurdistán, on the Khasa river. The waters of the Khasa were cold and the current was swift. A high bridge crossed the ravine, and a local man, to show his ability dove from the bridge into the river. His feat pleased Bahá'u'lláh, and when the diver entered His presence, Bahá'u'lláh gave him a little money. While Bahá'u'lláh stayed in Karkúk, some high officials came to visit Him, and Bahá'u'lláh met the son of Shaykh Muḥyi’d-Dín of Khániqayn, the man in whose honor the Seven Valleys had been revealed. The old Shaykh had died before Bahá'u'lláh arrived in Karkúk, but his son, Shaykh 'Alí entered Bahá'u'lláh’s presence with great devotion.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 181-182.

Ustád Muḥammad-'Alíy-i-Salmání, the Barber, My Memories of Bahá'u'lláh, page 28.

A stunning photo of the city of Irbíl taken by the American Colony (Jerusalem). Source: Library of Congress.

The caravan was slowly leaving leaving ‘Iráq as it wound its way to Irbíl, one of the last stops before entering Turkey. Irbíl and its hilltop castle sat on a plain opening west to the great Zab river. The day Bahá'u'lláh arrived in Irbíl was the Feast of ‘Íd al-Aḍhá (The Feast of the Sacrifice), one of the holiest days in the Islámic calendar, honoring Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice His son in obedience to God.

The prominent men of Irbíl came to greet Baha'u'llah on this holy day and, as their offering, brought meat cooked from sacrificial animals.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 182.

Wikipedia: Eid al-Adha.

HOW THE DATE WAS OBTAINED

The Islamic Holy Day of ‘Íd al-Aḍhá always falls on the 10th day of the last month of the Muslim calendar, Dhu-al-Hijjah. That day, in 1862-1863 (1279 A.H.) fell on 28 May 1863.

Habibur: Islamic Hijri Calendar For Dhu al-Hijjah - 1279 Hijri

This magnificent view of the Great Zab River near Irbíl on the way to Mosul in Iráqí Kurdistán is perhaps what Bahá'u'lláh would have seen from the caravan. Photographer: jamesdale10. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Leaving Irbíl behind, the caravan hired boats to cross the rushing waters of the Zab river, and lost two mules, carried away by the current. The caravan set up camp on the other side of the Zab, and were about to start their night march towards Mosul when high winds began to blow. They halted for a short while in a Christian village called Baraṭallíh and set up camp on the banks of the Tigris, near Nabíyu’lláh-Yunis, where some believe Jonah (Yunís) is buried.

On the opposite side of the river was Mosul, a handsome though slightly decayed city, whose houses, on the slope of the Jabal-Jubilah, formed a six-mile amphitheater.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 182-183.

A bazaar scene in Mosul, by the Tigris River, the shoe market. The cowardly Mírzá Yaḥyá, who returns to our story now, spent years of his life peddling shoes and slippers in bazaars like this one, under fake names, in hiding. Photographer: American Colony (Jerusalem), 1932. Source: Library of Congress.

Bahá'u'lláh stayed in Mosul for three days and visited the public bath and notables came to pay their respects to Bahá'u'lláh in His camp on the bank of the Tigris.

Mírzá Yaḥyá, afraid Bahá'u'lláh would be handed over to Persian authorities, had traveled to Mosul in disguise, and now, this far from Persia, finally felt comfortable showing his face, bust still disguised as a dervish with a black cord around his head and an alms bowl in his hand. He joined the caravan from Mosul onwards, but immediately started causing trouble, fighting with his future acolyte, Siyyid Muḥammad-i-Iṣfahání, and was reprimanded by Bahá'u'lláh.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 183-184.

The story below takes place between Mosul and Zákhú (Zakho), still in Iráqí Kurdistán on the last stage of the journey. The city of Duhok is exactly at that point in the journey, perhaps 3 or 4 kilometers to the east. This mountain, Girê Malta, is located between Dohuk and Sumel, which is on the road the caravan would have taken. It is offered here for a glimpse of the scenery on the way to Zákhú. Photograph taken in 2012 by MikaelF. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Bahá'u'lláh had now entered Turkey. On the way to Zákhú, stopping by the foot of a small mountain, the caravan encountered hostile and abusive Kurds who threw rocks at them, refused to sell them food and denied them night guards. The exiles themselves stood watch over the caravan through the night, intoning a call-and-response prayer, one group chanting “Whose is the dominion?” and the other responding “God’s, the All-Powerful, the All-mighty!” They left at dawn, progressing very slowly, as guiding the 14 howdas through the stony forested mountain passes and narrow gorges was dangerous and difficult.

As they approached Zákhú, the Qá’im-Maqám sent a large group of men to help maneuver the caravan, each howdah guided by four men, and when they neared the town, they found the Qá’im-Maqám and the notables of the town waiting for Bahá'u'lláh by the roadside.

They gave the travelers a warm and happy welcome, and offered Bahá'u'lláh a feast, which He graciously accepted, and Bahá'u'lláh honored His hosts as He made a reference to nearby Mount Ararat, the resting place of Noah’s Ark: “Whenever on our way they wanted to treat us as their guests and provide us with a feast, We did not accept, just as Noah's Ark rested nowhere but on the peak of Ararat.”

The Mufti of Zákhú stressed the inhabitants’ delight at Bahá'u'lláh’s presence, inviting Him to stay a few days, and the Qá’im-Maqám sent various gifts to Bahá'u'lláh, including snow, and punished the unruly Kurds of the previous night. The stay in Zákhú was pleasant but short, and the caravan proceeded towards Jazírih at nightfall, accompanied by an escort offered by the kind Qá’im-Maqám.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 185.

Wikipedia: Mount Ararat: Resting Place of Noah’s Ark.

The Bible, King James Version: Genesis 8:4 (Reference to Mount Ararat and Noah's Ark).

The ruins of the Roman Pinaca (or Finik) Castle from a region known as Corduene northwest of Jazírih (Cizre). It is possible this area is where Bahá'u'lláh's caravan camped on the banks of the Tigris. Photograph taken in 1909 by Gertrude Bell. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The caravan reached Jazírih the next day, and camped on the bank of the river near and old castle, and stayed until nightfall.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 186.

The tumultuous Jakh-Jakh (more commonly known as Çağ Çağ, but also spelled Jaghjagh) River, as it flows through the town of Niṣíbín (Nusaybin or Nisibis). Photographer: Ftkurt, 2009. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

After sunset the caravan continued its route towards Niṣíbín, an ancient Roman city. They pitched their tents in a delightful spot by the torrential Jaghjagh river, a tributary of the Euphrates. From Niṣíbín, the caravan pushed towards Márdín, two or three stages away. One of the stops, Ḥasan-‘Ághá, was located in a barren plain devoid of grazing pastures, Uthmán, the muleteer, complained that his mules were not eating enough, but the region was struck with a famine, and people were also not getting enough food.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 186.

As a joyful the-world-is-but-one-country homage to the story below, here is a photograph of a Spanish muleteer and his three (not lost) mules. Photograph take on 5 July 1899 by Eugène Trutat. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

During Bahá'u'lláh’s march from Baghdád to Sámsún, there are three stories of lost mules. This author has a particular soft spot for mules, so the stories were not cut from the chronology, though they were greatly abbreviated. This charming story is Part I.

From Ḥasan-‘Ághá, the caravan arrived in a village at the foot of Mount Márdín, a limestone cliff surmounted by an impregnable fortress, where an Arab muleteer from Damascus joined the caravan with his three mules. The man declined Bahá'u'lláh’s kind invitation to sleep near the caravan, as there were always robbers on these routes, and during the night, the man’s three mules were stolen. In the morning, as the caravan was leaving, the muleteer, beside himself with grief, rushed to Bahá'u'lláh’s howdah and holding the hem of His robe, begging Him to help him recover his animals, fully convinced only Bahá'u'lláh had the power to help him.

Touched by the man’s sincerity, Bahá'u'lláh canceled the departure of the caravan, gave orders for the mules to be recovered, and announced He would move into Firdaws (Paradise), a magnificent mansion surrounded by an orchard with running brooks, until the animals were found.

The headman of the village had no hope to find the mules again because the caravan route was swarming with thieves and no stolen property was ever recovered. Over the next two days, a constant stream of high-ranking notables from Márdín, of which half the population was Christian, came to pay their respects to Bahá'u'lláh.

The village headman offered to pay the value of the mules several times. Bahá'u'lláh refused, the Mutiṣarrif threatened to arrest the headman, Bahá'u'lláh said He would cable Constantinople for a solution if they did not find the animals, and finally, on the second day, the headman of the village returned the three mules to their distraught owner.

The people of Mardín were amazed. No stolen property on the caravan route had ever been recovered. As a reward for their efforts, Bahá'u'lláh offered the Mutiṣarrif a costly cashmere shawl, gave the Mufí an illuminated copy of the Qur'án, and the head of the horsemen received a sword with a jewel-encrusted scabbard.

On the third day, the caravan left, and perplexed men and women were heard saying in disbelief as to what had just happened: "We do not know this Personage, nor are we able to fathom the force which enabled Him to recover and return those mules to their owner. It was an act beyond the power of leaders and ministers alike."

'Alí-Akbar Furútan, Memories of Bahá'u'lláh, pages 31-34.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 186-188.

THE NUMBER OF MULES

In the unpublished memoirs of Áqá Ḥusayn-i-Áshchí, there are three mules. In Nabíl's account there were several, and Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, cites two. I made the decision to go with three mules, because it is the number cited by the story containing the most details.

ABOUT THIS STORY

The story of the lost mules is a composite of three accounts, the unpublished memoirs of Áqá Ḥusayn-i-Áshchí, the untranslated portion of the Dawn-Breakers, and Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory.

A panorama of the city of Márdín. Photographer: Ben Bender, 2013. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

After the mules were found, Bahá'u'lláh’s caravan departed Firdaws and crossed the town of Márdín, preceded by a mounted escort of government soldiers carrying their banners and beating their drums in welcome, and accompanied by the Mutiṣarrif. Men, women and children of Márdín crowded the flat roofs and the streets to watch the procession as Bahá'u'lláh crossed Márdín with the dignity and pomp of a king, escorted for a considerable distance out of the town by the mutiṣarrif, officials and notables of the city.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 188.

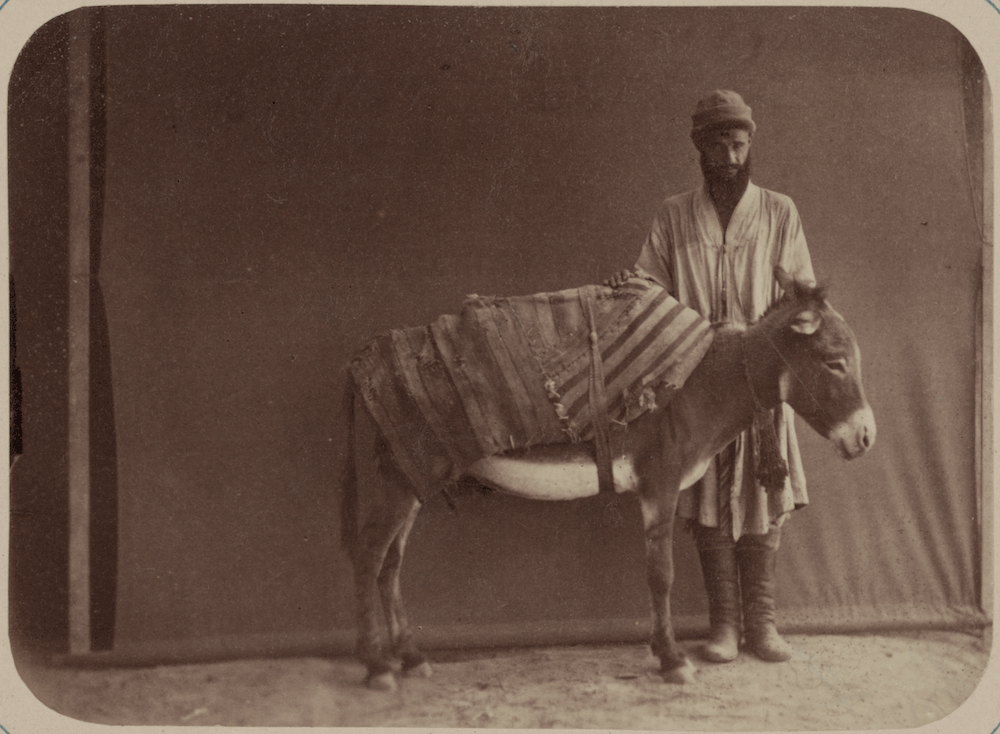

Man standing next to a mule fitted with a pack saddle. A pack saddle can be filled with items to carry, then ridden upon, making double use of the animal. Photograph taken between 1865 and 1872. Library of Congress Photographs.

As the caravan made its way towards Diyár-Bakr through a heavily-wooded area, they realized a mule had gotten lost, and the officer accompanying the caravan offered his own mule as a replacement, saying it would be impossible to recover it. This mule, however, was carrying several cases of Bahá'u'lláh's Writings and other important objects, and 'Abdu'l-Bahá requested Bahá'u'lláh's permission to set off, in the dead of night and with a few horsemen, to search for the lost animal.

'Abdu'l-Bahá split the search party into several groups to search paths in the forest, and told the men to call out or light a fire when they found the mule. 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s fine strategy worked, and by sunrise, the mule had been found. The elated search party rejoined the caravan around noon and Bahá'u'lláh commented that the “act which the Most Great Branch undertook was similar in many respects to” His own determined and confident attitude in finding the Arab muleteer’s three lost mules near Mardín.

‘Alí-Akbar Furútan, Stories of Bahá’u’lláh, page 35.

A 1900 photograph of Diyárbakr by Oscar Mann. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Diyár-Bakr was the largest Kurdish city in Turkey, where Turkish, Armenian, Kurd, and Arab territories converged, and at the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. At an altitude of 600 meters (2,000 feet), Diyár-Bakr overlooked a vast and fertile plain, but the city itself, within its black basalt walls, was humid and unhealthy, with narrow and muddy streets.

The Governor of Diyár-Bakr, Ḥájí Kiyámilí Páshá, was unfriendly towards Bahá'u'lláh, unlike his colleagues along the way, and forced the caravan to maneuver around the entire city to camp in ‘Alí-Párib, a lovely mansion surrounded by a large orchard.

Bahá'u'lláh’s caravan was refused entry to ‘Alí-Párib on the rather strange grounds that the silk cocoons on the mulberry trees would be disturbed the smell of their cooking. Bahá'u'lláh instructed His entourage to set up camp outside the orchard, which took the rest of the day. Bahá'u'lláh stayed there, just outside Diyár-Bakr, for three days, during which Mírzá Yaḥyá, emboldened to be so far from the Persian border, began to take part in the life of the caravan, accompanying others into town to make purchases.

The rude Governor, Ḥájí Kiyámilí Páshá would soon get his due. He was blamed for a bread shortage, and the people of Diyár-Bakr rioted, humiliating him so deeply that the government dismissed him from his post.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 188-190.

Wikipedia: Diyarbakir.

The landscape around Ma'dan-i-Mis (Maden, Turkey). Source: Google Maps StreetView.

From Diyár-Bakr, the caravan headed to Ma'dan-i-Mis (Copper Mine), and camped at the foot of a steep castle-topped mountain. By sunset, three believers had joined the caravan including Nabíl-i-A'ẓám and Áqá Ḥusayn-i-Naráqí.

Bahá'u'lláh received a message from a Persian who was imprisoned in Ma'dan-i-Mis, begging for His intercession to help free him, and Bahá'u'lláh promised to approach the Persian Ambassador in Constantinople on his behalf.

Please read Constantinople: The Persian prisoner Part II, in Constantinople to discover the end of the story.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 190-191.

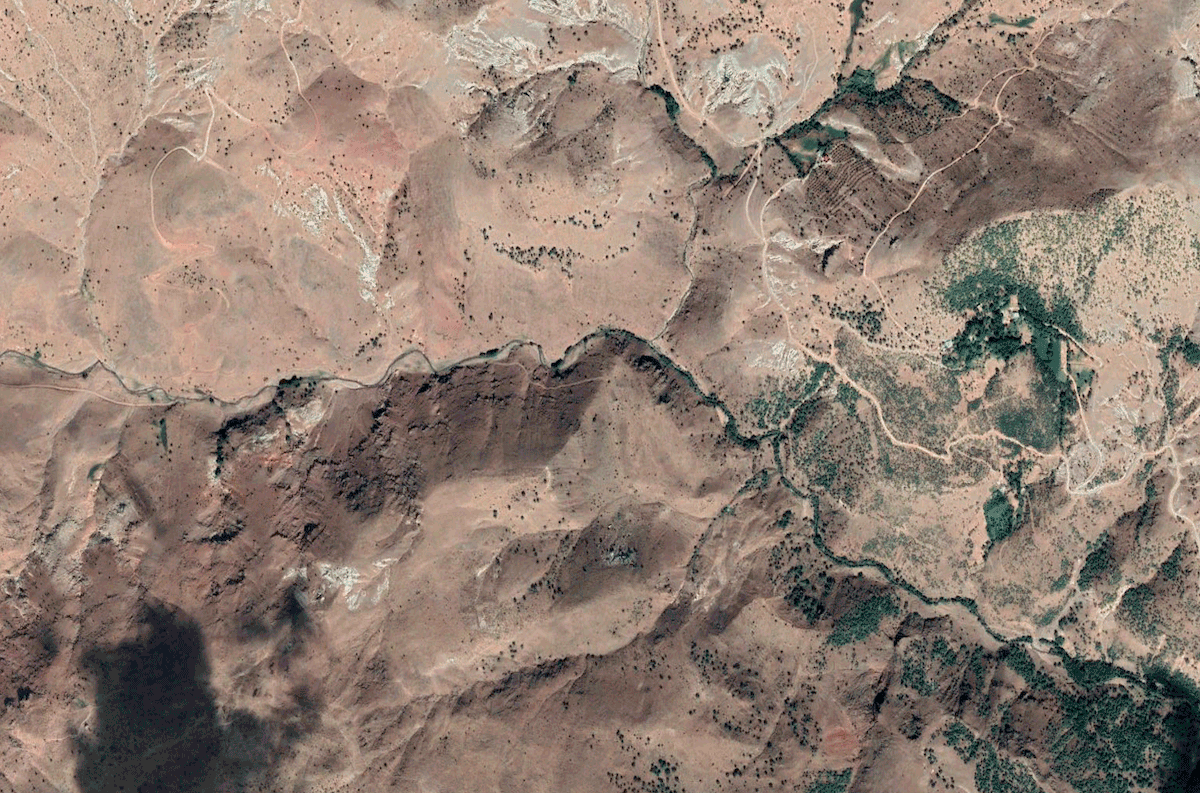

Google Earth Pro 7.3.4.8248 (2022). The mountains just outside the possible location for Ma’dan-i-Mis, offered as an illustration of the rugged landscape where Bahá'u'lláh almost died, 39.044523°, 38.182151°. Available online by following this link. [Accessed 14 January 2022]

Leaving Ma'dan-i-Mis on the way to Khárpút, the caravan navigated its way through a narrow road in a mountain pass when Ḥájí Maḥmúd lost his hold on the reins of the mule carrying Bahá'u'lláh’s howdah. The mule slipped, lost its balance and started to slide down the precipice. The accident happened in an instant, and Bahá'u'lláh’s companions watched in horror, powerless to stop the inevitable.

Suddenly, miraculously, the mule regained its balance and slowly came to a halt. As Bahá'u'lláh’s companions registered that He was safe, the sheer joy of that realization filled their eyes with tears. After the averted calamity, an extremely large container of rosewater broke, filling the air with its fragrance.

Towards sunset the caravan came upon another mountain pass with many poplar trees and a running rivulet, where they stopped for the night, and the next day, they arrived at a Christian village, setting up their tents underneath abundant trees.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 190-191.

Hazar Gölü lake in Elazığ Province, halfway between Ma'dan-i-Mis and Kharpút, on the path of the caravan and in the region the story below takes place. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

As the caravan started crossing from Eastern Anatolia to the Black Sea region of Turkey, probably sometime around early to mid-July 1863, a famine was ravaging the area, and it became very difficult for 'Abdu'l-Bahá to obtain fodder for the animals, weak and losing weight due to scarce rations.

After the caravan set up camp, 'Abdu'l-Bahá and Mírzá Jaf’ar would ride from village to village, and one Arab or Kurdish tent to another, trying to find food, straw, barley, often searching until midnight. One day, they called on a Turk who was harvesting, and when they saw his large pile of straw, they thought their search had finally come to an end.

'Abdu'l-Bahá approached the man and offered to buy some straw from him, and after a moment the Turk asked 'Abdu'l-Bahá “Open your sack,” then put in a few handfuls of straw. Amused, 'Abdu'l-Bahá told him: “Oh, my friend! What can we do with this straw? We have thirty-six animals and we want feed for every one of them!” Everywhere they went, 'Abdu'l-Bahá encountered difficulties finding food until they arrived in Khárpút.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 186.

A beautiful view of the vast plain between Kharpút and Elazığ, 5 kilometers (3 miles) southwest. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Bahá'u'lláh’s caravan reached the fortified city of Khárpút, overlooking a cultivated and fruitful plain. When the caravan was still five kilometers (three miles) away from Khárpút, they found officials and notables awaiting their arrival to welcome them.

When the caravan of Bahá'u'lláh arrived in Khárpút, they had covered around 1,000 kilometers (620 miles) and the animals were weak and exhausted. The Acting Governor-General, ʻIzzat Páshá, who loved Bahá'u'lláh and wanted to rend Him service, called on Him and offered ten car-loads of rice, ten sacks of barley, ten sheep, several baskets of rice, several bags of sugar, and many pounds of butter as a gift. After the ordeal of the harsh journey in the midst of a punishing famine, ʻIzzat Páshá’s gifts were gladly accepted as a bounty from God. Utterly spent, 'Abdu'l-Bahá slept for two full days and nights when they first arrived.

Mírzá Muḥammad-'Alí, a younger son of Baha'u'llah from His second wife, became ill in Khárpút, and the caravan stayed for a week in Khárpút until he recovered. During that week, Bahá'u'lláh and some of His entourage visited the public bath. Mírzá Yaḥyá ordered Ustád Muḥammad-'Alíy-i-Salmání, Bahá'u'lláh’s barber to shave his son bald, a custom at the time, but the barber went to Bahá'u'lláh who did not allow it. Mírzá Mihdí, the Purest Branch, then around 14 or 15, observed to Ustád Muḥammad that Mírzá Yaḥyá had begun to notice that everyone was not subservient to him.

At one point during their stay in Khárpút, Bahá'u'lláh ordered some gáz (a form of middle-eastern nougat), and divided up the pieces between everyone, sending three fine pieces to Mírzá Yaḥyá. The pieces melted together and two believers ate them, which provoked Mírzá Yaḥyá’s rage, calling them traitors and thieves and accusing them of not believing in the Báb. Mírzá Yaḥyá muttered and grumbled about his lost nougats for several stops after they left Khárpút.

Star of the West,Volume XIII, No. 10, pp. 277–278. “Exiled From Bagdad: A story from the words of Abdul Baha” by Mirza Ahmad Sohrab.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 192.

Ustád Muḥammad-'Alíy-i-Salmání, the Barber, My Memories of Bahá'u'lláh, pages 31-34.

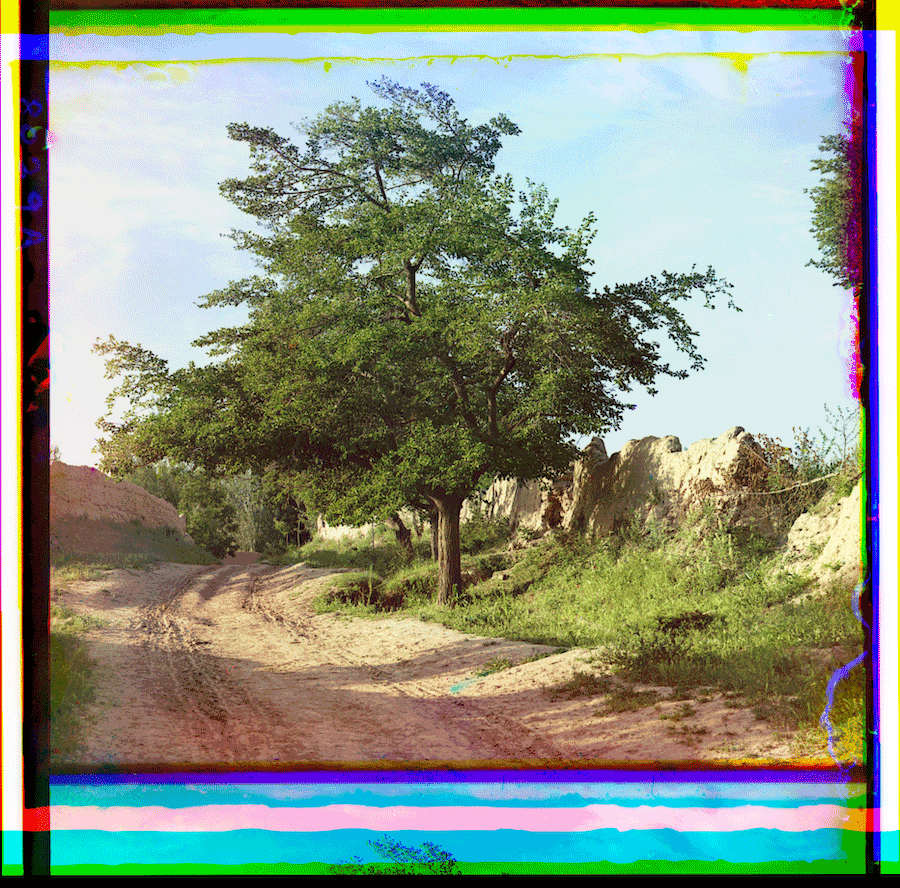

There are three reasons why this image is the illustration for the story below. The first, is that it’s a mulberry tree, and a beautiful one at that. The second is that the three-color separation digital composite from the glass negative has a surprising appearance, which mimics the surprising turn of the story. And the third is that the photographer who took this picture was born 14 days after Bahá'u'lláh arrived in Constantinople. A mulberry tree in Samarkand, Uzbekistan, taken by Sergeĭ Mikhaĭlovich Prokudin-Gorskiĭ, (1863-1944). Source: Library of Congress.

Leaving Khárpút, Bahá'u'lláh was now halfway from Baghdád to Constantinople. The caravan arrived in Ma'dan-i-Nuqrih (Silver Mine), then crossed the Euphrates River and set up their tents on the opposite bank. Some of Bahá'u'lláh’s companions had found mulberry trees, and set upon them eating mulberries voraciously. This aroused Bahá'u'lláh’s anger and He spoke sternly to His brother, Mírzá Muḥammad Qulí, before retiring to His tent. When Bahá'u'lláh emerged from His tent in late afternoon, as was His custom, all His companions including Mírzá Yaḥyá were waiting outside with bowed heads. Speaking to them and smiling, Bahá'u'lláh said: “Today, Divine anger nearly seized all, as you witnessed.” There was absolute silence, then Bahá'u'lláh had tea served.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 192-193.

Panorama of the region of Deliktaş from the Facebook Group "DELİKTAŞ 58." Link to the original image. Link to the main Facebook page of DELİKTAŞ 58.

Ma'dan-i-Nuqrih was four days away from Sívás, the next large town on the caravan’s route. They were now in the uplands of Anatolia, and it was very cold. At each of the stops on the way to Sívás, including one called Dilík-Tásh, notables came out to meet Bahá'u'lláh and His entourage and make the travelers feel welcome. During one of their stops, the caravan halted by a river where Bahá'u'lláh underwent bloodletting, and His blood spilled on Turkish soil, perhaps foreshadow the coming period of turmoil and tribulations.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 192-193.

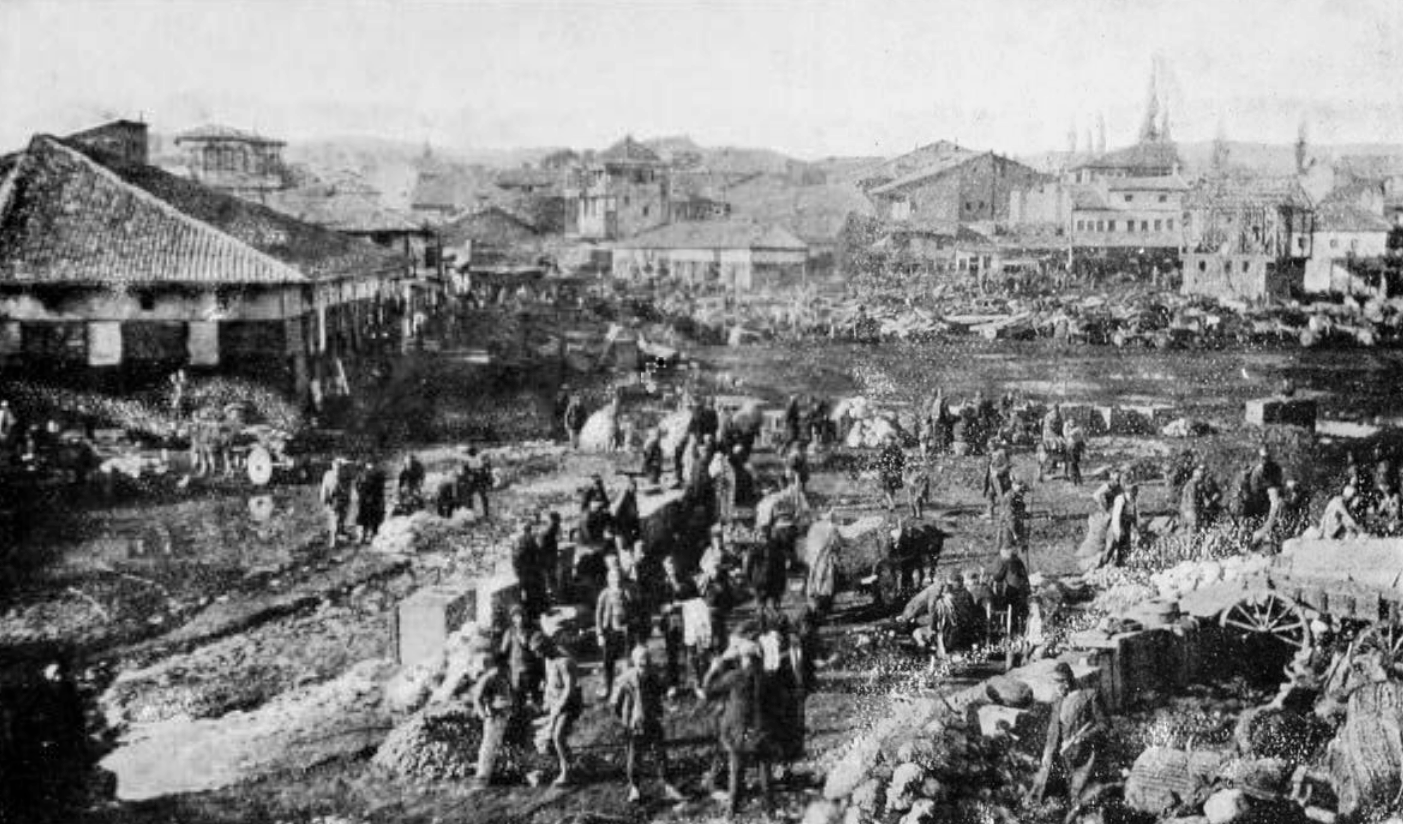

The bustling marketplace in Sívás. From W.J. Childs, Across Asia Minor on Foot, published by William Blackwood and Sons, 1917. Source: The Internet Archive.

The caravan reached Sívás, about 1,200 meters (4,000 feet) above sea-level, and everyone’s possessions had to cross the Kızılırmak river. Ustád Muḥammad-'Alíy-i-Salmání, noticing noise and bustle on the other side of the river, asked 'Abdu'l-Bahá to cross ahead of time to receive the baggage, and the cowardly Mírzá Yaḥyá took advantage to cross with him first. Around sunset, the Governor arrived with some officials and notables came to pay their respects to Bahá'u'lláh.

The caravan camped for two days on the northern bank of the Kızılırmak, in very cold weather, but Bahá'u'lláh was still able to visit the public bath. In Sívás, there was a Shaykh, a Ṣúfí leader well-versed in Persian who recited several Rúmí poems from the Mathnaví while he was in Bahá'u'lláh’s presence. Seeing the Shaykh's interest in poetry, Bahá'u'lláh recited no less than sixty verses of the Mathnaví from memory, though no one had ever seen Him read it. The Shaykh was deeply happy and noticeably touched by Bahá'u'lláh's gesture.

'Alí-Akbar Furútan, Memories of Bahá'u'lláh, pages 34-35.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 193.

Ustád Muḥammad-'Alíy-i-Salmání, the Barber, My Memories of Bahá'u'lláh, pages 29-30.

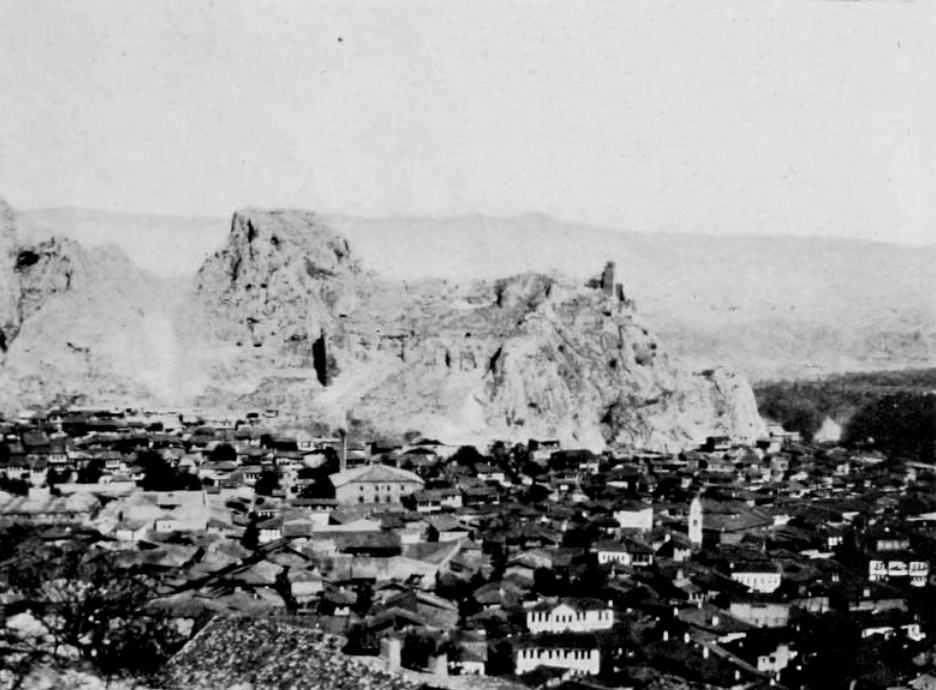

Castle Rock, Túqát. From W.J. Childs, Across Asia Minor on Foot, published by William Blackwood and Sons, 1917. Source: The Internet Archive.

Túqát was three days away from Sívás, and the journey took place in very cold weather. At one of the stops, the exiles found that all the houses were underground because of the harsh winter months. This could very well be the town of Boyunpınar (see references), located between Sívás and Túqát on the route of the caravan, where there are underground houses, a large cave with about 20 man-made rooms.

The caravan also pitched its tents in a large orchard, finally reaching Túqát, a city blessed with deliciously flavorful apples and pears, and they camped on the bank of the Yeşilırmak river, flowing towards Amásiyá, their next destination.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 193-194.

Facebook: Tokatadair: Underground houses in Boyunpınar.

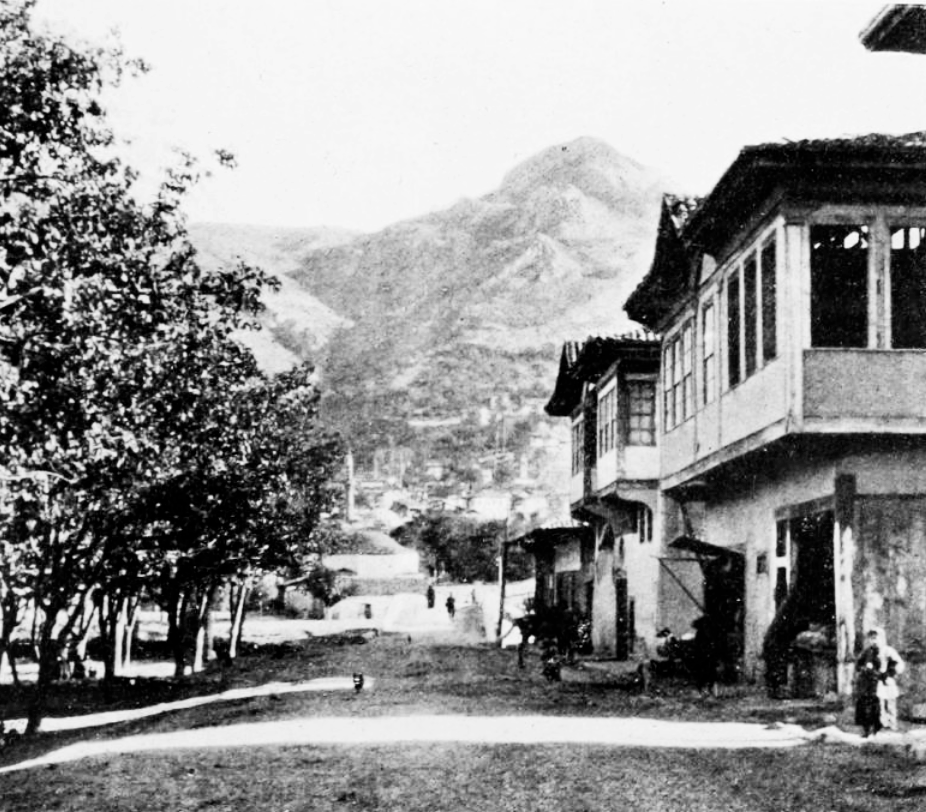

Entering Amasiya. From W.J. Childs, Across Asia Minor on Foot, published by William Blackwood and Sons, 1917. Source: The Internet Archive.

Most probably around mid-July 1863, having traveled 1,290 kilometers with only 250 (800 miles with 155) to go before reaching Sámsún, the caravan paused for two days outside Amásíyá, a city described as the “Oxford of Anatolia” because of its 18 theological colleges and 2,000 Muslim students.

Amásíyá lay in a narrow valley of the Yeşilırmak, dominated by steep rocky cliffs to the west, and gentle slopes to the east with houses and terraces of vines. The Governor and his officials called on Bahá'u'lláh who was also able to avail Himself of the public bath during this stop, but the exiles had run out of money and some sold their horses, which fetched an excellent price.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 194-195.

When one superimposes the map in Mr. Balyuí's Bahá'u'lláh: The Glory of God, onto a modern map, the location of the village of Ilahíyyih is almost directly on top of that of the village of Çakallı. There is currently no location determined for Ilahíyyih but in any case, the Çakallı valley is on the direct route to Sámsún, and therefore on the road Bahá'u'lláh would have taken. Photograph © Katherine Branning. Source: Turkish Han website: Turkish Han: Cardak (Çakallı) Han.

After a pleasant stay in Amásiyá, the caravan arrived at Iláhíyyih, the seat of a Qá'im-Maqám, who arrived to the camp before Bahá'u'lláh, accompanied by his officials. Finding that only the tents had arrived, he and his companions began pitching the tents for Bahá'u'lláh, and returned later to enter His presence and pay their respects.

Although it rained a little while Bahá'u'lláh’s companions were stopped in Iláhíyyih, they still had a wonderful time in the town because the inhabitants were kindness personified.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 195.

Digital painting of the forests between Iláhíyyih and Sámsún where the mule was lost, inspired by user photographers of Feza Memorial forest available here. © Violetta Zein.

At long last, the caravan began the last leg of its 1,600 kilometer (990 mile) overland journey towards Sámsún, their final stop before boarding a steamer to Constantinople. The route took the caravan through wooded mountains and thick forests, where a mule carrying trunks got lost.

'Abdu'l-Bahá and two of His companions went in search of the trunk-carrying mule, found it, and rejoined the caravan the next day, in the vicinity of Sámsún. That night, the caravan stopped at a large coffee-house before embarking on the last stage of their march, and, at long last, they arrived within sight of the Black Sea. To mark the memorable occasion, Mírzá Áqá Ján begged Bahá'u'lláh to reveal a Tablet, which is known as the Lawḥ-i-Hawdaj (Tablet of the Howdah).

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 195.

1870 photograph showing an approach to Sámsún with a view of the Black Sea, seven years after Bahá'u'lláh arrived here. Photographer: Dimitri Ermakov. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

After making his request for a Tablet, while Bahá'u'lláh’s was in view of the Black Sea, Mírzá Áqá Ján brought Him writing material. Baha'u'llah's hand moved over the paper, as He sat in His howdah, reciting aloud what flowed from His Pen. The Suriy-i-Hawdaj (the Surih of Howdah), also known as Lawḥ-i-Sámsún (Tablet of Sámsún).

In this Tablet, “disclosed in the Pavilion of Eternity and the Howdah of Holiness at the moment when the Greatest Name arrived…at the shore of a mighty ocean,” when His “terrestrial journey hath found completion,” Bahá'u'lláh states He reaffirms and supplements His dire predictions in the Tablet of the Holy Mariner three months prior. Addressing the Holy Mariner once again, Bahá'u'lláh sounds the dire warning of an impending "grievous and tormenting mischief" that would serve as the "Divine touchstone" separating truth from error.

Partial Inventory ID: BH01069

Baha'i Tablets: Provisional translations: Tablet of the Howdah, a provisional translation by Stephen N. Lambden.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Steven Phelps' Chapter 5: The Writings of Bahá'u'lláh in Routledge World: The World of the Bahá'í Faith, First Edition, Edited By Robert H. Stockman.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 195.

1870 (seven years after Bahá'u'lláh sailed from here) Sámsún seafront castle walls and coast. Photographer: Dmitri Ermakov. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The arduous overland part of the long march of Bahá'u'lláh had lasted one hundred and ten exhausting days, during which Bahá'u'lláh had traversed the flat northern regions of ‘Iráq, the homelands of the Kurds, the uplands, mountains and valleys of Anatolia, crossed rivers and streams, camped in caravanserais, orchards, mansions, crossed narrow gorgeous and steep mountain passes, narrowly escaped death and He had been received like a King in almost every place He arrived, and ended the journey by revealing the momentous Lawḥ-i-Hawdaj, in the words of Hand of the Cause Ḥasan Balyuzi, a “fitting end to an exodus, intended by its instigators to be fraught with humiliation, but which became the march of a king,”

Bahá’u’lláh, the Holy Family, and the band of devoted exiles at their side, arrived in the port city of Sámsún on the shores of the Black Sea, after a grueling 1,600-kilometers (990 miles), where they waited a week for an Ottoman steamer to take them to Constantinople.

The Chief Inspector showed Bahá'u'lláh the utmost respect, and Bahá'u'lláh, invited the official to luncheon. An Ottoman Inspector of Roads arrived in Sámsún from the capital, and became so captivated with Bahá'u'lláh’s charm and graciousness, that he had various Turkish dishes cooked to present to Him, and brought horses to take Him on a tour of some construction work he was supervising.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 195-196.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Bahá'u'lláh, Tablet of the Holy Mariner.

Photo of Sinope by Bjørn Christian Tørrissen. Source: Wikimedia Commons. Photo of Anyábulí by Dosseman. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

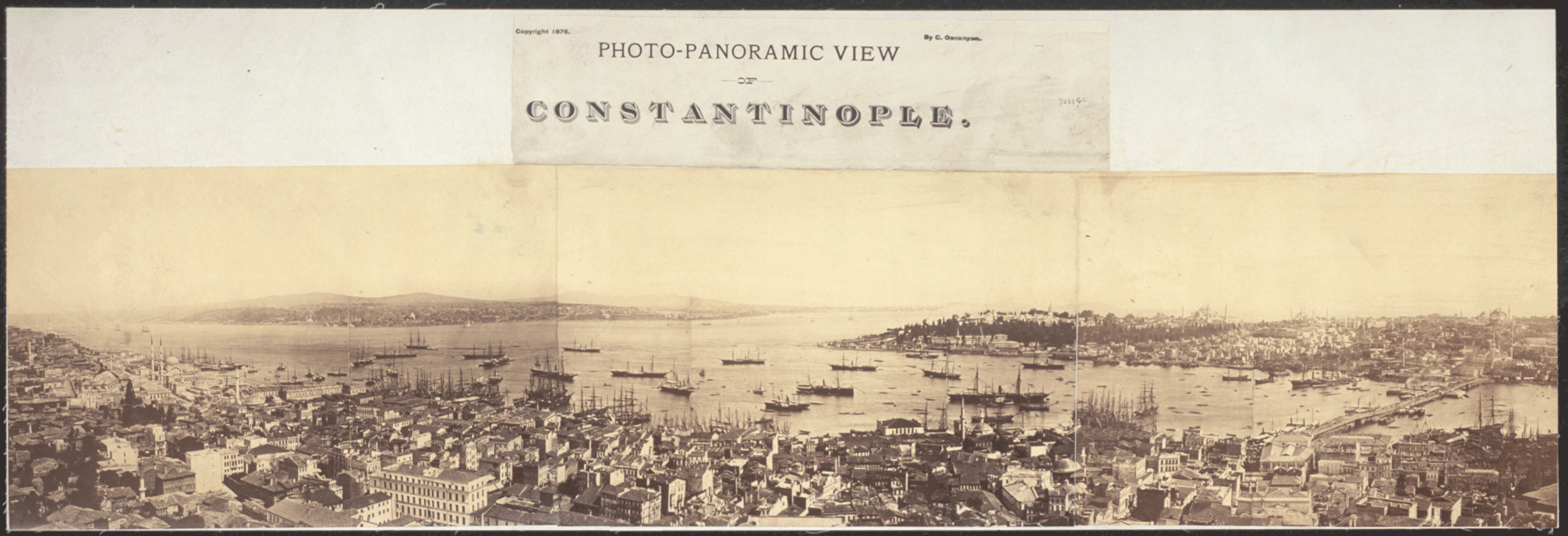

Circa 1876 Photo-panoramic view of Constantinople by Christopher Oscanyan. Source: Library of Congress.

At last, on 13 August 1863, the steamer arrived in Sámsún. The exile’s trunks, goods, and horses were loaded, Bahá'u'lláh and His Family were taken aboard in one boat, and the rest of His companions in a second boat. They cast off anchor, and sailed along the coast of Turkey, arriving in Sinope the next day, 14 August, where they stopped for a few hours. On 15 August, they dropped anchor in Anyábulí, and arrived in Constantinople the next day after sailing 700 kilometers (430 miles) on the Black Sea.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 196.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Wikipedia: Round City of Baghdad.

Wikipedia: Constantinople.

Note: There is almost no historical information on the sea journey between Sámsún and Constantinople, which explains the brevity of this section.

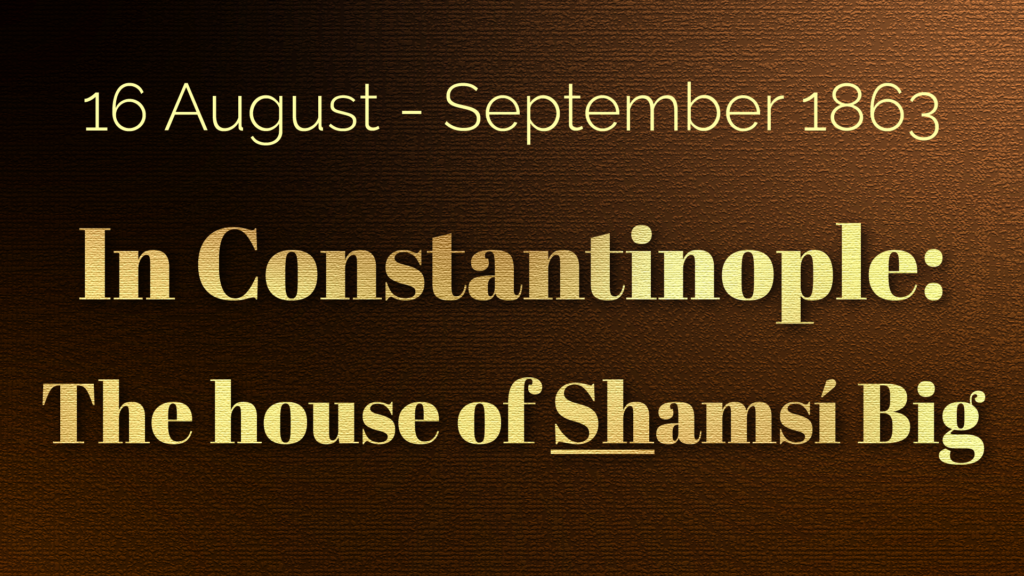

There is no clear indication which port Bahá'u'lláh arrived at in Constantinople (Istanbul) after His three-day sea journey from Sámsún, but this 1880-1893 photograph depicts the port of Sirkeci, on the European side of Constantinople, and is located 3 kilometers (1.8 miles) from the mosque of Kiriqiy-Sharíf (Hırka-i Şerif mosque, also known as the Mosque of the Exalted Cloak), in the vicinity of Bahá'u'lláh's first home in Constantinople, the house of Shamsí Big. Photographers: Abdullah Frères. Source: Library of Congress.

Bahá’u’lláh set foot in Constantinople at noon on 16 August 1863: the King of Glory had left Baghdád, the “Round City” of the Abbasids, and arrived in the “New Rome” of Constantine the Great. The official who had accompanied the travelers since Baghdád went ashore to enquire about the arrangements that had been made for their arrival, and Bahá'u'lláh was received with great honor by Shamsí Big, and other Ottoman officials as He disembarked the ship.

Shamsí Big had been appointed by the government to entertain Bahá'u'lláh and His companions. His residence, located in the vicinity of the Kirqiy-i-Sharíf (Hırka-i Şerif) mosque, was to be the home of Bahá'u'lláh and the Holy Family, for the first month of their exile in Constantinople, while the rest of their companions were lodged elsewhere.

Shamsí Big was a courteous, generous, and attentive host, and he hired two cooks, whom the exiles willingly helped prepare the meals. His house was a spacious, two-story home, but not large enough to accommodate Bahá'u'lláh’s large family comfortably, and it became obvious rather quickly that they would need more spacious lodgings.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 197.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868, page 2.

The Old Port of Constantinople, by Abdullah Frères, late 19th century. Photo courtesy of Istanbul Üniversitesi, Nadir Eserler Kütüphanesi

On the day he arrived in Constantinople, and after witnessing the honors bestowed on Bahá'u'lláh upon His arrival, Mírzá Yaḥyá remarked to his acolyte, Siyyid Muḥammad-i-Iṣfahání: “Had I not chosen to hide myself, had I revealed my identity, the honor accorded Him (Bahá’u’lláh) on this day would have been mine too.” The seed of jealousy had taken firm root in his heart, in a matter of four short years, it would grow to smother it and endanger his soul.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

1880 - 1893 photograph of the the mosque of Khirqiy-i-Shárif (Hırka-yi Şerif), close to where was located the house of Shamsí Big, the first house occupied by Bahá'u'lláh in Constantinople. Photographers: Abdullah Fréres. Source: Library of Congress.

The next day after His arrival, on 17 August 1863, a representative came to offer Bahá'u'lláh the respects of the Persian Ambassador, Ḥájí Mírzá Ḥusayn Khán, the same man who had played an instrumental role in having Bahá'u'lláh exiled to Constantinople.

Around noon on the same day, Baha'u'llah went out to visit Kirqíy-i-Sharíf mosque (Mosque of the Blessed Mantle), named after a relic, the mantle of Muḥammad, which He had reportedly given to Ka'b Ibn Zuhayr, after hearing him read a poem.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 197.

As a visual homage to the "barren trees" Bahá'u'lláh describes below, speaking of the people of Constantinople, a desaturated modern photograph of a forest of the dead trees in Namibia. Photographer: Ikiwaner. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Soon after His arrival, Bahá'u'lláh revealed a Tablet expressing His disappointment in the people He had met, describing their welcome as mere “conventional, officious formalities,” and finding them to be “many barren trees and much frozen snow,” and comparing them to “snow animals.”

Partial Inventory ID: BH04828

Original in Mixed Arabic and Persian Bahá'u'lláh, Má'idiy-i-Ásamání, vol. IV, p. 369.

Provisional translation by Juan Cole: Who Is Bahá'u'lláh? Website: The Snow Animals Letter.

Wikipedia: Deadvlei.

The Fatih Mosque, known in the time of Bahá’u’lláh as the Mosque of Sulṭán Muḥammad, between 1888 and 1910, where Bahá'u'lláh went daily for noon prayer. Sebah & Joaillier, photographer. Wikimedia Commons.

During His four months in Constantinople, Bahá'u'lláh only visited mosques, His brother Mírzá Músá’s home, and the public bath. Many called on Bahá'u'lláh in His homes, but Bahá'u'lláh Himself did not visit other people’s homes. At times, in the house of Mírzá Músá, Bahá'u'lláh would meet officials delivering messages from the Government, accompanied by His interpreter, Abdu’l-Ghaffár.

The notables of Constantinople told Bahá'u'lláh it was customary for a distinguished visitor to call on the Foreign Minister after three days, which would open the door to meeting first the Grand Vizir, then the Sulṭán, and advised Bahá'u'lláh to follow this protocol.

Bahá'u'lláh informed them He had no design or project to advance, no favor to ask or receive, and that He had come to Constantinople by invitation of the Ottoman government. If the Ottoman government had something they needed to convey to Him, they could come to Him.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 197-199.

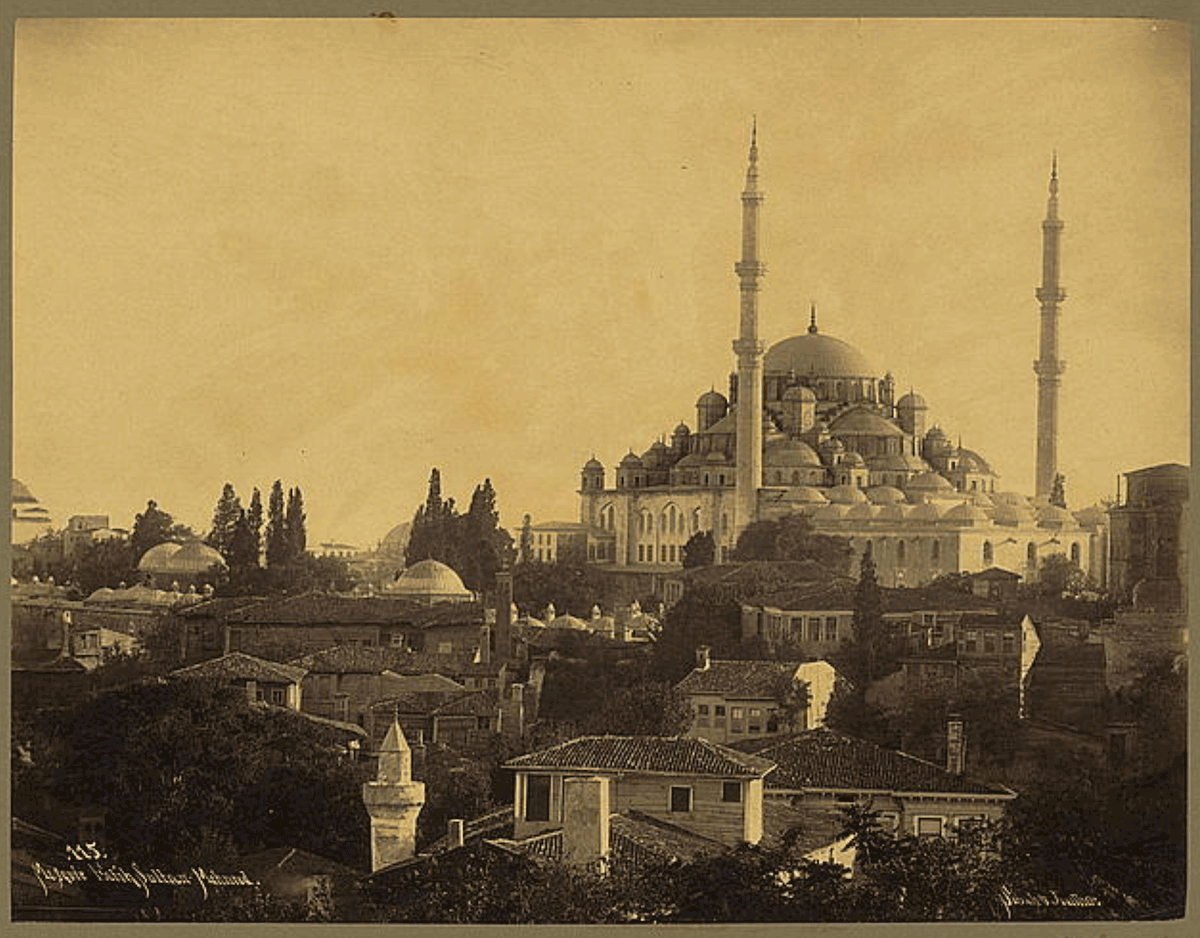

19th century Russian engraving of people waiting at the flour mill. Engraver: А. Земцов. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

One day, Áqá Riḍá, one of the cooks of the caravan, dreamt that Bahá'u'lláh had written a book, which was held by someone in a public square, and that there was a mill which people could not get going, the mill would only move in jerks, stopping, moving, then stopping again. That day, towards sunset, Bahá'u'lláh was about to leave the house to visit the mosque, when Áqá Riḍá entered His presence. Bahá'u'lláh told him, smiling, that he should endeavor to get the mill going. For some time after, and even in Adrianople, Bahá'u'lláh would sometimes turn to Áqá Riḍá and say “the mill did not get started.”

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 198.

A visual reminder in the form of a very minimalistic map of the distance between Ma'dan-i-Mis and Constantinople, and the time elapsed, yet Bahá'u'lláh never forgot the Persian prisoner, as the story below shows. © Violetta Zein.

To read the beginning of this story, go to the story further up called Ma'adan-i-Mis (Maden): The Persian Prisoner Part I.

After the Persian prisoner in Ma'dan-i-Mis had pleaded for Bahá'u'lláh to intercede on his behalf, Bahá'u'lláh had nearly died when the mule carrying His howdah had lost its footing, they had crossed famine-stricken regions where food was scarce, and traveled, by land and by sea, the remaining 1,300 kilometers (800 miles) to His second place of exile.

Still, Bahá'u'lláh did not forget the poor man in Anatolia, and He sent word to the Persian Ambassador, Ḥájí Mírzá Ḥusayn-Khán, and the prisoner was released.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 191.

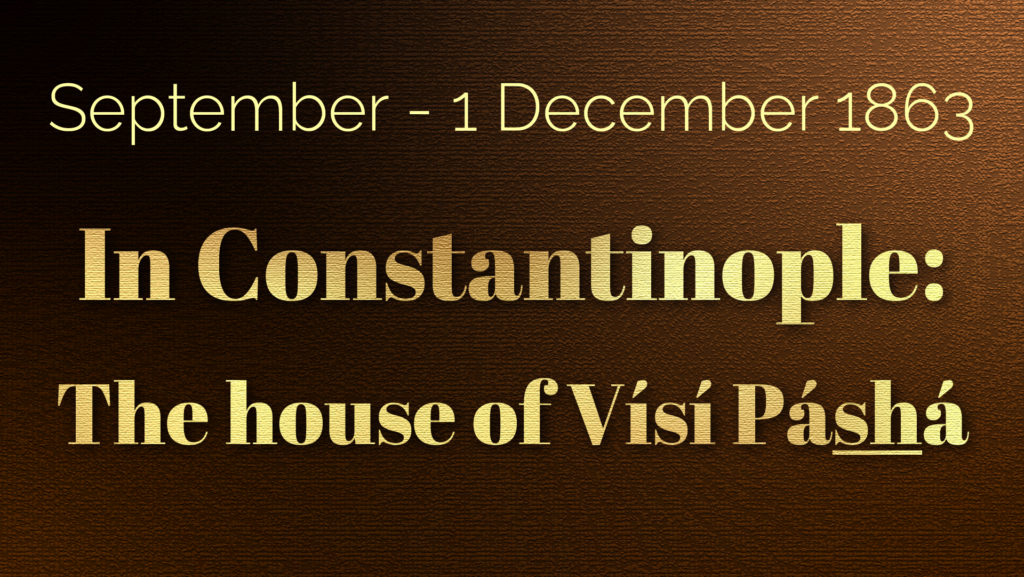

The Mosque of Nişancı Mehmet Paşa, 30 meters (98 feet) from the house of Vísí Páshá, directly across the street. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

After a month spent in uncomfortably tight conditions in the house of Shamsí Big, Bahá'u'lláh and the Holy Family moved to the house of Vísí Páshá, near the mosque of Sulṭán Muḥammad-i-Fátiḥ (also known as the mosque of Sultan Ahmet and the Blue Mosque). The new house was a palatial residence. Like the Most Great House in Baghdád, it had both a bírúní, public men’s quarters, and an andarúní, women’s inside quarters.

Both bírúní and andáruní were three stories high and well-equipped. The house boasted a Turkish bath, a spacious garden, and rainwater collecting facilities. Bahá'u'lláh’s quarters were on the first floor of the andarúní, with the rest of family occupying the other two stories. 'Abdu'l-Bahá lived on the first floor of the bírúní, Bahá'u'lláh’s companions on the second floor, and the third floor was turned into a kitchen and store..

A tent was pitched in the courtyard for two Christian servants sent by the Government to do the shopping and perform various other duties. Every morning, Bahá'u'lláh’s former host, Shamsí Big, came calling to the house of Vísí Páshá and took care of Bahá'u'lláh and the Holy Family’s needs, ensuring their well-being.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 199.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868, page 3.

This wonderful group photograph of Bahá'ís in Constantinople in 1863 is the subject of the story below. Pictured here are Áqáy-i-Kalím, Mírzá Músá, Bahá'u'lláh's faithful brother in the very center of the photograph, dressed in white with a white turban and a black beard. Sitting from left to right, are Ḥájí Mírzá Aḥmad-i-Káshání and Siyyid Muḥammad-i-Iṣfahání; Standing, from left to right: Áqá Muḥammad-Ṣadiq-i-Iṣfahání and Nabíl-i-A'ẓam the historian. Source: H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 200.

One day, in the Autumn or Winter of 1863, a photographer approached Mírzá Músá as he was walking towards the Big-Úghlí bazaar, and offered to take his photograph free of charge, and bring him copies. Mírzá Músá granted the photographer’s request, explaining to his companions with his characteristic empathy: “He wants to earn something by photographing us. This is his means of livelihood. We will not deprive him of it.”

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 199.

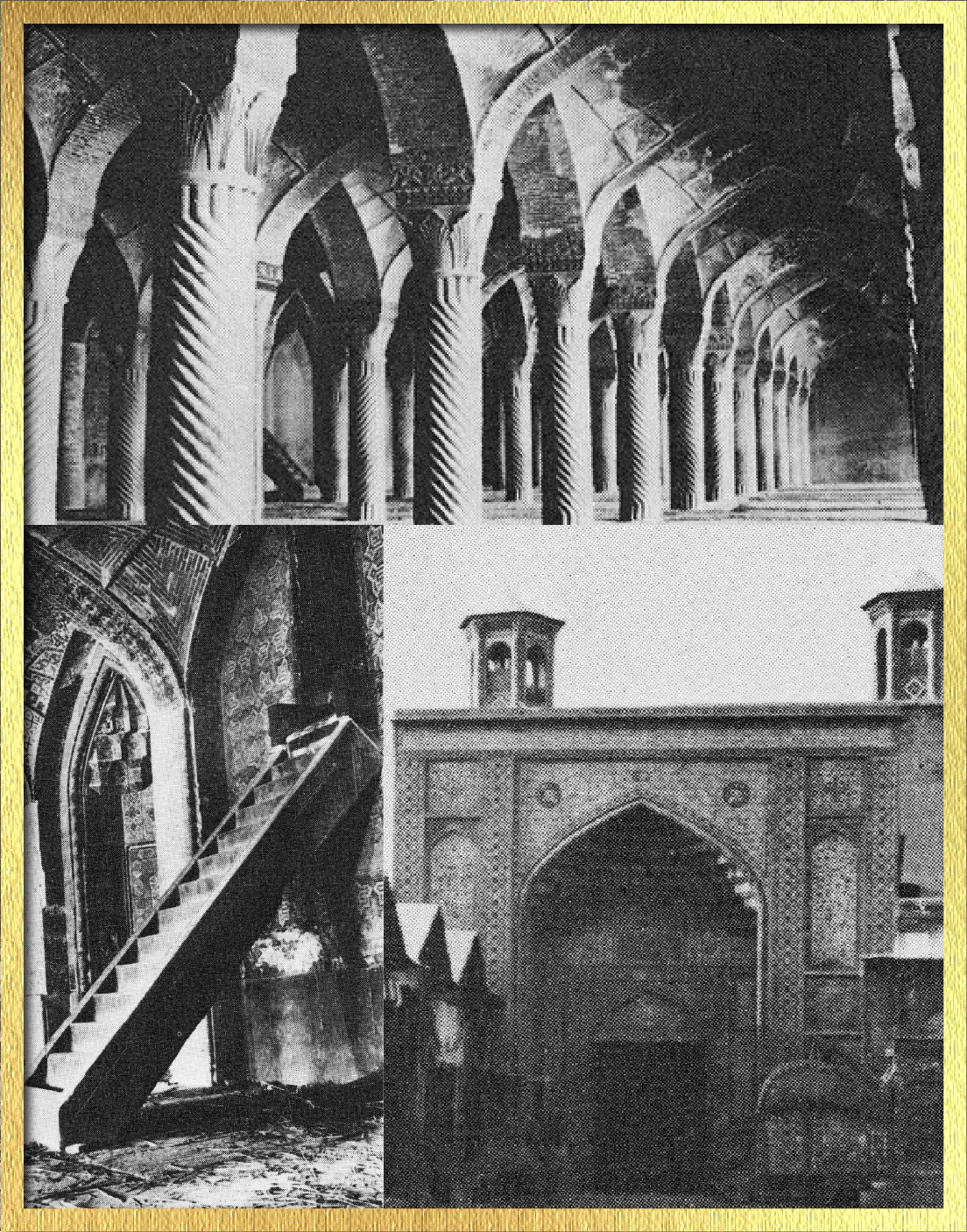

In honor of the Lawḥ-i-Naqús, revealed to commemorate the Declaration of the Báb, and announcing the ringing of a mighty Bell, three images from another rung bell, and another kind of declaration, when the Báb rebuked the congregation at Friday prayer in the Masjid-i-Vakíl in Shíráz. Top: Interior of the Masjid-i-Vakíl. Bottom left: Pulpit which the Báb ascended to address the congregation. Bottom right: Entrance door to the mosque. Source: Nabíl: The Dawn-Breakers, page 152.

On the eve of the anniversary of the Declaration of the Báb which, according to the lunar calendar, fell on 19 October 1863, Bahá'u'lláh revealed a beautiful Tablet in Arabic in His own hand honoring the Báb and called the Lawh-i-Náqús (Tablet of the Bell). This Tablet brought great joy to the believers who were celebrating the Báb’s Declaration.

The Tablet has two names. It is known as Lawh-i-Náqús (Tablet of the Bell) for the line “O Monk of the Divine Unity! Ring out the bell,” and it is also known as Subhánika-Yá-Hú (O Thou Who art “He”) because of the recurring invocation to the Báb repeated 28 times throughout the Tablet like a mighty bell ringing: “By Thy name “He”! Verily Thou art “He”, O Thou Who art “He”!”

In the Tafsír-i-Hú, revealed in Baghdád, Bahá’u’lláh explains that the name “He” (in Arabic Huva, consisting of Há’ and Váv) is God’s Most Great Name, and a mirror in which all of God’s names and attributes are reflected together.

Partial Inventory ID: BH00759

Bahá'u'lláh, Lawḥ-i-Náqús (Tablet of the Bell).

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868, pages 18-27.

The Tower of Babel is an origin myth found in Genesis 11:1–9 meant to explain why the world's peoples speak different languages. This painting from 1563, painted exactly three hundred years before this story is by Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

One day, while in Constantinople, Kamál Páshá visited Bahá'u'lláh, and their conversation turned to topics profitable to mankind. Kamál Páshá mentioned he had learned several languages, but Bahá'u'lláh gave him another, radically different vision, telling him:

“You have wasted your life. It beseemeth you and the other officials of the Government to convene a gathering and choose one of the divers languages, and likewise one of the existing scripts, or else to create a new language and a new script to be taught children in schools throughout the world. They would, in this way, be acquiring only two languages, one their own native tongue, the other the language in which all the peoples of the world would converse. Were men to take fast hold on that which hath been mentioned, the whole earth would come to be regarded as one country, and the people would be relieved and freed from the necessity of acquiring and teaching different languages.”

Kamál Páshá joyfully agreed with His argument, and Bahá'u'lláh told him to present the issue to officials and ministers in the government, so that it might be acted upon in the different countries. Kamál Páshá often returned to visit Bahá'u'lláh after this conversation, but never followed through or broached the subject again, as Bahá'u'lláh testified: “although he often returned to see Us after this, he never again referred to this subject, although that which had been suggested is conducive to the concord and the unity of the peoples of the world.”

Bahá'u'lláh, Epistle to the Son of the Wolf, pages 137-138.

Wikipedia: Tower of Babel.

A 1789 oil on canvas painting of Sultan Selim III holding an audience in front of the Gate of Felicity, with courtiers assembled in a strict protocol. This type of pleading is what the notables of Constantinople suggested Bahá'u'lláh resort to. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Most of the high-ranking personalities who called on Bahá'u'lláh expected Him to curry favors in securing the support of the Ottoman Government. They soon found out Bahá'u'lláh was above such things, and His unfailing honor and integrity, dignity of bearing, and upright conduct impressed them all. The conversation, when these notables of Constantinople were in Bahá'u'lláh’s presence, mostly centered on the arts and sciences, but one day, some noblemen dispensed unsolicited advice to Bahá'u'lláh saying: “To appeal, to state your case, and to demand justice is a measure demanded by custom.”

Bahá'u'lláh is reported to have said that what they understood stating His case was in fact nothing more than please and demands, something to which He would never sink, and turned the tables on them by calling into question the diligence and professionalism of the Ottoman ministers: “If the enlightened-minded leaders [of your nation] be wise and diligent, they will certainly make inquiry, and acquaint themselves with the true state of the case; if not, then [their] attainment of the truth is impracticable and impossible.”

Bahá'u'lláh assured the notables present that He felt no urgency, no anxiety, and was not only ready and prepared for whatever was predestined for Him, submissive to the Will of God, and entirely confident that there was no dispeller of affliction save God.

'Abdu'l-Bahá, A Traveler’s Narrative, p. 92.

Wikipedia: Selim III.

After His Declaration in the Garden of Riḍván a few days before leaving Baghdád, Bahá'u'lláh was no longer the leader of the Bábís, He was the Manifestation of God heralded, lauded, and extolled by the Báb, the Promised One of all ages.

As His companions, now His followers, associated with One who was the repository of all of God’s attributes and powers, they found themselves spiritually tested, in the purity of their character and the sincerity of their faith. To remain close to Bahá'u'lláh, His companions underwent spiritual purification, attempting to rid themselves of every trace of self, and evince steadfastness and detachment.

Bahá'u'lláh’s awe-inspiring and majestic presence, radiating at the same time kindness and authority, His radiant countenance, and all-encompassing love and compassion had a magnetic effect on people. He could simultaneously overwhelm, revive, comfort His disciples and transport them to spiritual realms.

Two people entering His presence would feel His love directed only towards them, His words addressed to each one alone, and neither could describe their shared experience, so affected would they be in their innermost soul, only able to tell each other “I was intoxicated and in a state of ecstasy.”

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868, pages 7-8.

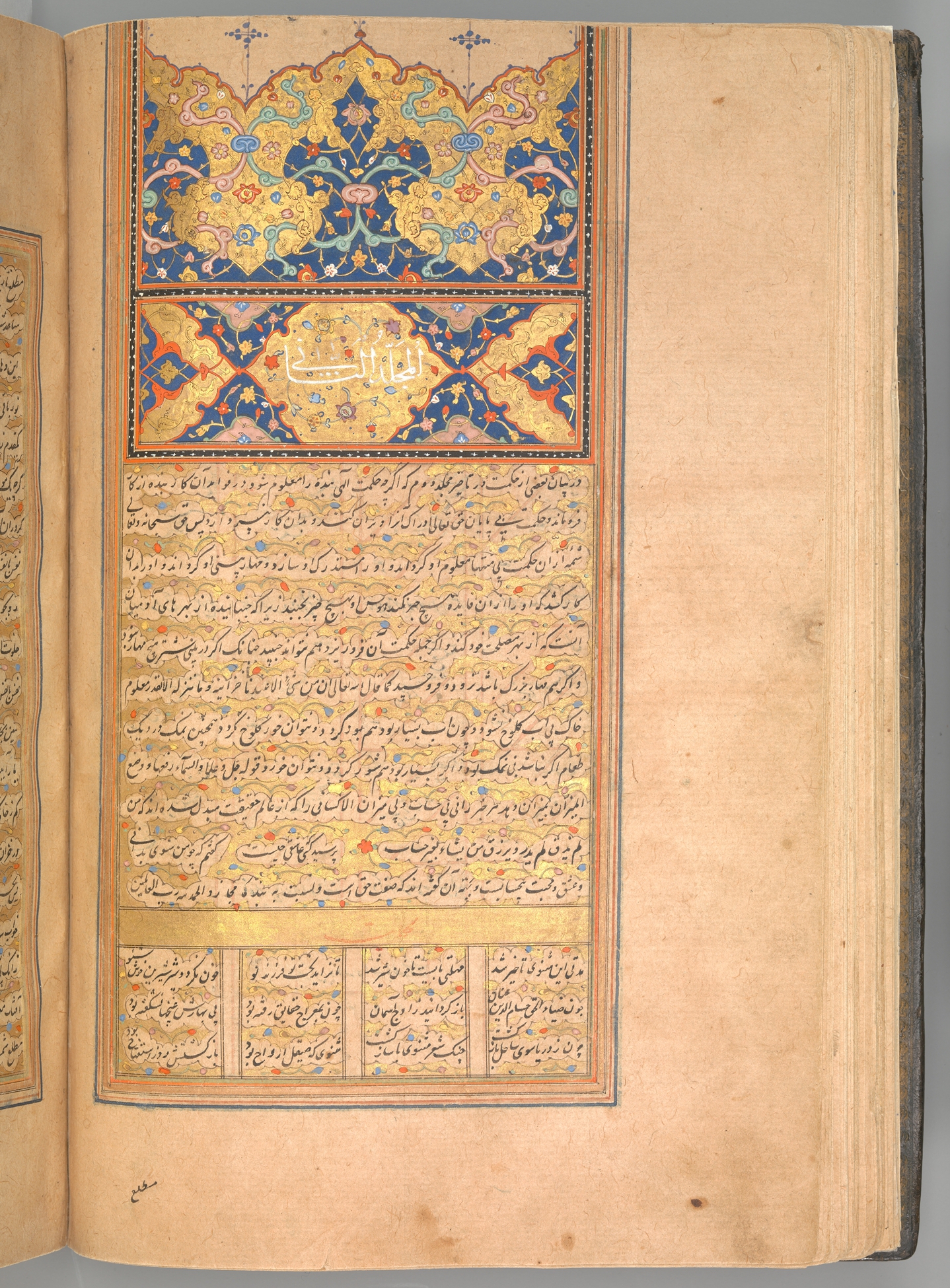

Page 58 of a 15th century copy of the Masnavi of Jalal al-Din Rumi, dated 1488–89. Source: The Met.

The Mathnavíy-i-Mubárak (The Blessed Couplets), is believed to have been composed at different times, starting in the mid 1850s in Sulaymáníyyih and Baghdád, but most of the poem was revealed in Autumn 1863 in Constantinople, where Bahá'u'lláh completed its Revelation. The Mathnavíy-i-Mubárak is the longest work He revealed in rhyme and meter, and also among His last.

A mathnaví is poem using rhyming couplets in Persian, intrinsically a rhyme-rich language, and the most famous example being Rúmí’s 13th century masterpiece, the Mathnavíy-i-Ma’navi (The Spiritual Couplets), six books of poetry amounting to 25,000 verses, and considered to be the greatest mystical poem ever written.

Bahá'u'lláh’s Mathnavíy-i-Mubárak, a long poem at 4,04 verses, while alluding to Rúmí’s poem, closing with the trop of reed pipes with which Rúmí opens his poem, and using similar imagery to the Persian Hidden Words, uses the theological and rhetorical tools of Ṣúfísm to prepare the way for Bahá'u'lláh’s future, wider proclamation, and to disclose His station to the Bábís and to humanity as a whole and including mentions of Ḥusayn, ‘Alí the Mihdí, and Imámi traditions of Shíism.

In this work, Bahá'u'lláh discloses realities of the world of humanity and indicates how we can achieve the summit of glory, echoing The Hidden Words, He identifies Himself as the Day-Star of Truth, describes His coming as the Advent of the Day of God, the divine springtime bestowing new life on all creation. In the Mathnavíy-i-Mubárak, Bahá'u'lláh cautions that before human beings can truly reflect divine virtues, they must first purify their hearts and tear asunder the veils that would keep them from perceiving spiritual truths.

Partial Inventory ID: BH00108

Provisional translation: Mathnaviyí-i Mubárak, by Bahá'u'lláh translated by Frank Lewis, published in Bahá'í Studies Review, Volume 9 London: Association for Baha'i Studies English-Speaking Europe, 1999.

Wikipedia: Masnavi.

Frank Lewis, Poetry as Revelation: Introduction to Bahá'u'lláh's ‘Mathnavíy-i Mubárak, published in Bahá'í Studies Review, Volume 9 London: Association for Baha'i Studies English-Speaking Europe, 1999.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863–1868, pages 29–54.

Top left: Sulṭán ‘Abdu’l-‘Azíz, Sulṭán of the Ottoman Empire. Source: Wikimedia Commons. Top right: Mírzá Ḥusayn Khán, Persian Ambassador in Constantinople (Mirza Hosein Khan Moshir od-Dowleh Sepahsalar). Source: Wikimedia Commons. Bottom left: ‘Alí Páshá, Prime Minister to the Sulṭán (More information on his Turkish Wikipedia page: (Mehmed Emin Âli Pasha) Source: Wikimedia Commons. Bottom right: Fu’ád Páshá, Foreign Minister to the Sulṭán (More information on his Turkish Wikipedia page: Keçecizade Mehmet Fuat Pasha). Source: Wikimedia Commons.

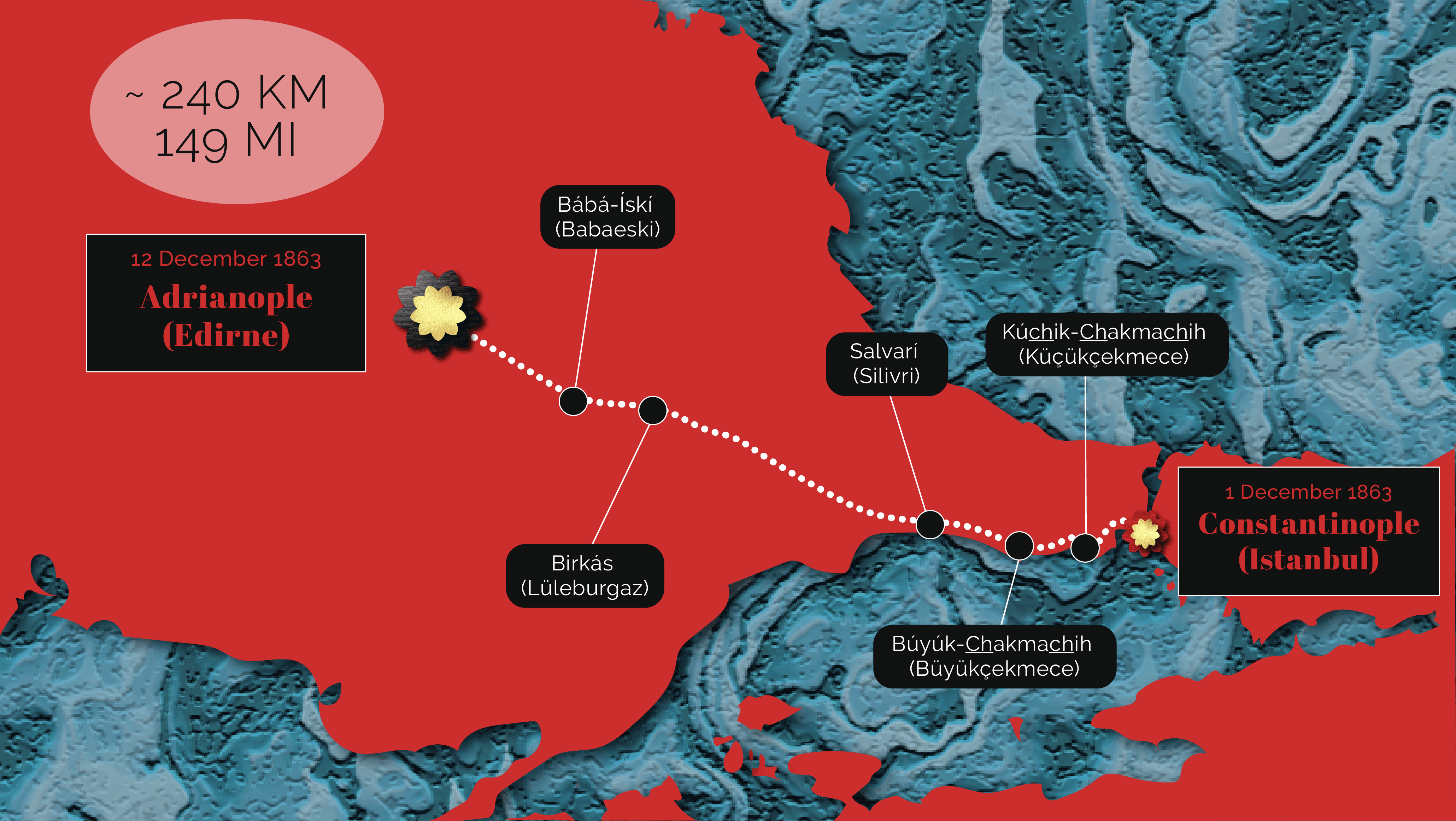

Ḥájí Mírzá Ḥusayn Khán, the Persian Ambassador in Constantinople, who had plotted against Bahá'u'lláh when He was in Baghdád, was on the offensive again. Under constant pressure from the Persian government, he slandered Bahá'u'lláh to the chief ministers of Sulṭán ‘Abdu’l-‘Azíz, ‘Alí Páshá and Fu’ád Páshá, who pressured the Sulṭán until he decided to banish Bahá'u'lláh to Adrianople, in the farthest reach of the Ottoman empire, in the depths of winter.

Ḥájí Mírzá Ṣafá was a close friend of the Persian Ambassador, a two-faced man with ambitions to become a murshid, an influential position with high social status. He had frequently visited Bahá'u'lláh in Constantinople, but at times, Bahá'u'lláh would speak to him with such authority that Ḥájí Mírzá Ṣafá was at a loss for words, and once He addressed the deceitful man with such power that His voice rang down to the ground floor of the house.

Mírzá Ḥusayn Khán deeply resented Bahá'u'lláh’s independent and dignified behavior, refusing to beg for political favors, and instructed Ḥájí Mírzá Ḥasan-i-Ṣafá, to spread unfounded rumors about Him, which he then used in his circle of influence, to portray Bahá'u'lláh as an arrogant person, Who thought Himself above the law and posed a threat to all authority.

Calumnies about Bahá'u'lláh began to spread in gatherings of Ottoman notables who said that Bahá'ís were “a mischief to all the world and destructive of treaties and covenants; they are a source of trouble and baleful to all lands; they have kindled a fire and consumed the earth; and though they be outwardly fair-seeming yet are they deserving of every chastisement and punishment.”

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 198-199.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

'Abdu'l-Bahá, A Travelers’ Narrative.

Another portrait of Fu’ád Páshá (More information on his Turkish Wikipedia page: Keçecizade Mehmet Fuat Pasha). Source: Wikimedia Commons. Fu’ád Páshá was the Grand Vizir during Bahá'u'lláh's four months in Constantinople. 'Alí Páshá was Grand Vizir when Bahá'u'lláh arrived in 'Akká. Fu’ád Páshá was Grand Vizir from 22 November 1861 to 6 January 1863 and from 3 June 1863 to 5 June 1866. 'Alí Páshá was Grand Vizir five times, in 1852, 1855 - 1856, 1858 - 1859, 1861 and 1867 to 1871, but not while Bahá'u'lláh was in Constantinople.

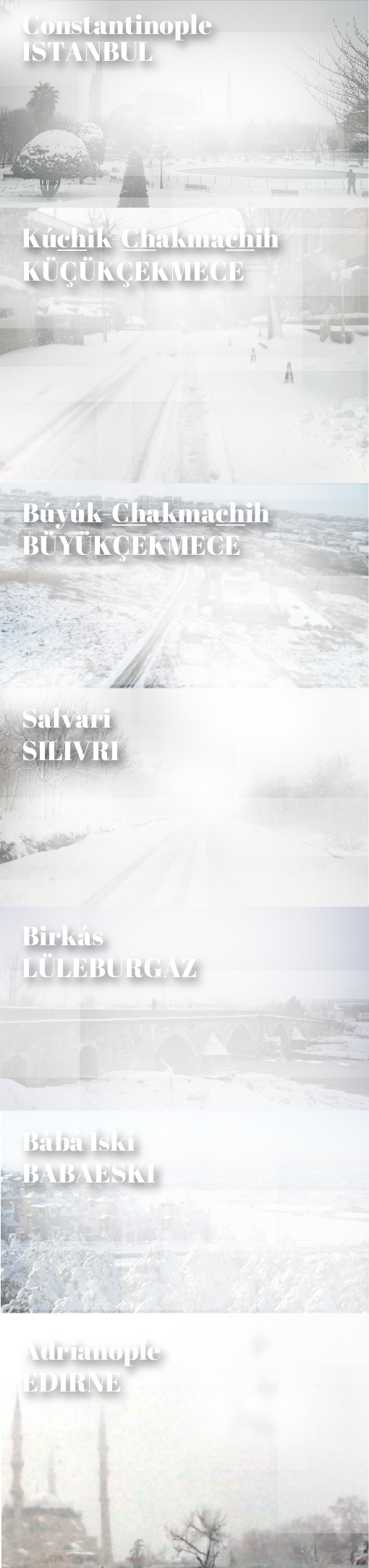

In the winter of 1863, Bahá'u'lláh’s 18-month-old daughter Sádhijíyyih Khánum with His second wife, passed away and was buried in a plot of land outside the Adirnih Gate of Constantinople. Soon after this personal tragedy, Bahá'u'lláh received the edict for His third exile. Bahá'u'lláh refused to receive the Grand Vizir’s envoy, delegating 'Abdu'l-Bahá and Mírzá Músá to listen to his trivial observations and arguments. The envoy said he would return in three days to receive Bahá'u'lláh’s response.

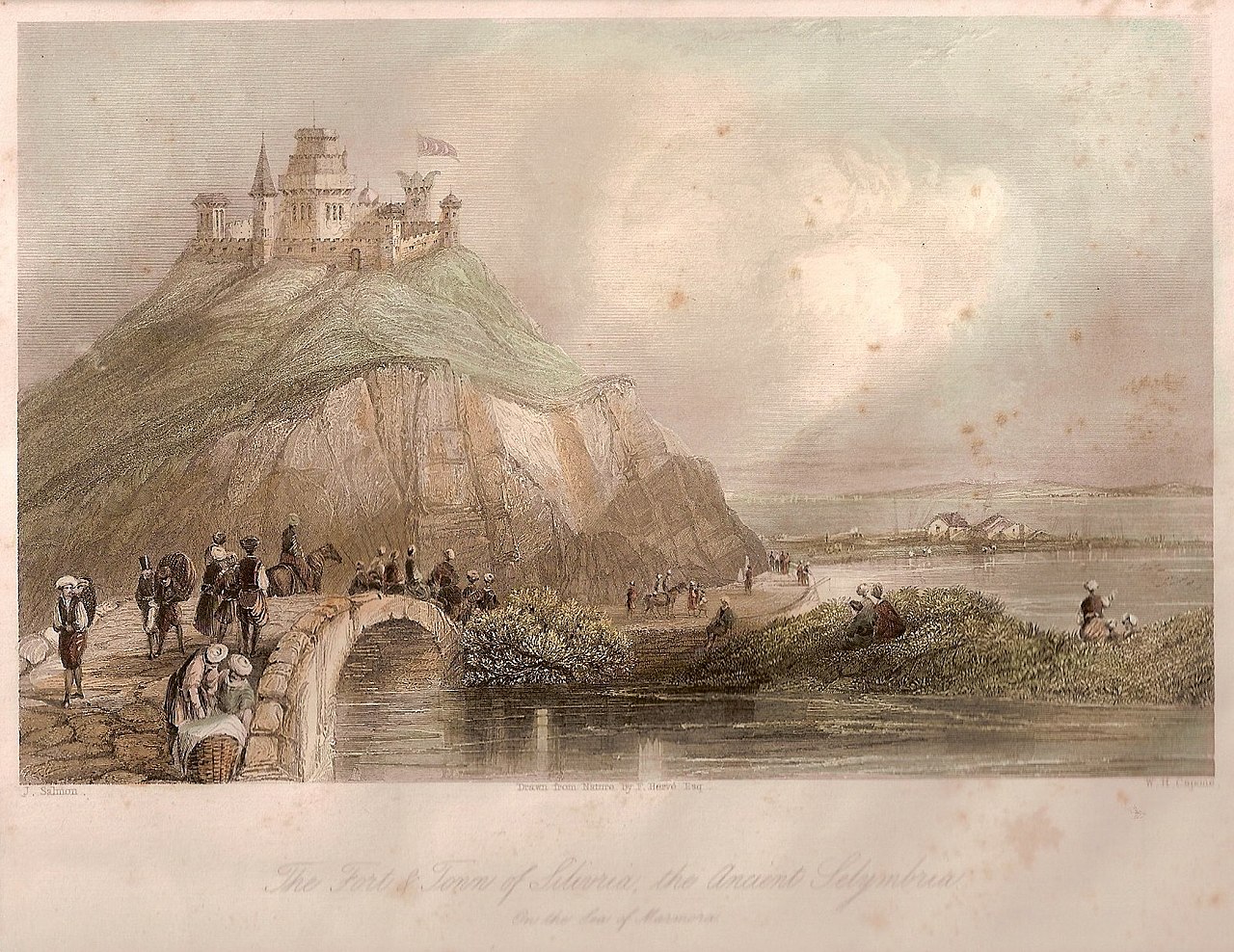

Bahá'u'lláh refused to comply to the edict for a new banishment. It was a deeply unfair, unprovoked, and cruel humiliation to be banished in the dead of winter to Adrianople, at the very edge of the Ottoman empire, for Bahá'u'lláh who, since His arrival in Constantinople, had kept Himself away from the political cross-currents, and had not uttered a single word of complaint.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 199-203.

A collage of eleven photographs of Sulṭán ‘Abdu’l-‘Azíz found on Wikimedia Commons, cropped and resized for the faces to be proportional, then tiled with varying levels of transparency. Source: Photo 1, Photo 2, Photo 3, Photo 4, Photo 5, Photo 6, Photo 7, Photo 8, Photo 9, Photo 10, Photo 11. © Violetta Zein.

The initial phase of Bahá'u'lláh’s Proclamation to the world began in Constantinople, shortly before 1 December 1863, and four years before the Súriy-i-Muluk, with a now-lost Tablet to Sulṭán ‘Abdu’l-Azíz called the Lawḥ-i-‘Abdu’l-Azíz-va-Vukalá.

Bahá'u'lláh revealed this lengthy Tablet after receiving the decree for a new exile. The next morning, Bahá'u'lláh placed the Tablet in a sealed envelope, instructing Shamsí Big, to deliver it to ‘Alí Páshá, the Grand Vizir and to say that it was sent down from God. Shamsí Big did not know the contents of the Tablet but affirmed that “no sooner had the Grand Vizir perused it than he turned the color of a corpse, and remarked: ‘It is as if the King of Kings were issuing his behest to his humblest vassal king and regulating his conduct.’”

In the Tablet, Bahá'u'lláh rebuked the Sulṭán for this unjust banishment, reprimanded his ministers, exposing their immaturity and incompetence. Bahá'u'lláh addressed the ministers in several passages, sternly admonishing them not to take pride in their material possessions or foolishly seek fleeting riches.© Violetta Zein.

The Lawḥ-i-‘Abdu’l-Azíz-va-Vukalá was intended by Bahá'u'lláh as a turning point, as He stated: “Whatever action the ministers of the Sulṭán took against Us, after having become acquainted with its contents, cannot be regarded as unjustifiable. The acts they committed before its perusal, however, can have no justification.”

Partial Inventory ID: BH11579.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 206-208.

Mírzá Ḥusayn Khán, the Mushíru’d-Dawlih (Mirza Hosein Khan Moshir od-Dowleh Sepahsalar), the Persian ambassador in Constantinople. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Before leaving Constantinople forever, Bahá'u'lláh a last and memorable interview with Ḥájí Mírzá Ḥasan-i-Ṣafá, asking him to convey the following message to Ḥájí Mírzá Ḥusayn-Khán, the Persian Ambassador: “What did it profit thee, and such as are like thee, to slay, year after year, so many of the oppressed...We, few that we are, will stand our ground, until every one of us meets a martyr's death.”

When Ḥájí Mírzá Ḥasan-i-Ṣafá replied it wasn’t possible to withstand a government, Bahá'u'lláh said “Whenever I find the whole world assailing Me with drawn swords, all alone and engulfed as I may be, I see Myself seated on the throne of Might and Authority. It has always been the fate of the Manifestations of God to meet such injustice and oppression…”

Bahá'u'lláh asked Ḥájí Mírzá Ḥasan-i-Ṣafá to remind the Ambassador of a Quranic verse in which a believer argued with the Pharaoh. Thunderstruck, Ḥájí Mírzá Ḥasan-i-Ṣafá asked permission to leave, and Bahá'u'lláh asked His followers: “Do you wish to drain the cup of martyrdom? No better time can there be than now to offer your lives in the path of your Lord. Our innocence is manifestly evident, and they have no alternative but to declare their injustice.”

Bahá'u'lláh’s faithful followers were ready to follow Bahá'u'lláh into martyrdom, Ottoman observers felt pride in Bahá'u'lláh’s integrity, Ottoman authorities were impressed Persia still had men who stood up for their dignity, and Persian officials in Ṭihrán said Bahá'u'lláh’s conduct had brought prestige to their nation, at a time when most Qájár princes begged for handouts.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 201-203.

The seemingly indestructible stone walls of a Muslim place of worship enshrine Bahá'u'lláh's fearless and powerful words to the believers after accepting the second exile are offered here as a stark contrast to Mírzá Yaḥyá distinctive and perennial cowardice, rendered more pathetic in contrast to Bahá'u'lláh's fearlessness, courage, and integrity. Original image: Central mihrab (Muslim prayer room) in the tomb of Sikander Lodi, built in 1494 in New Delhi, Indi. Source: Wikimedia Commons. © Violetta Zein.