Written and illustrated by Violetta Zein

This part covers the life of the Báb from the age of 27 in 1846 to the age of 28 in 1847.

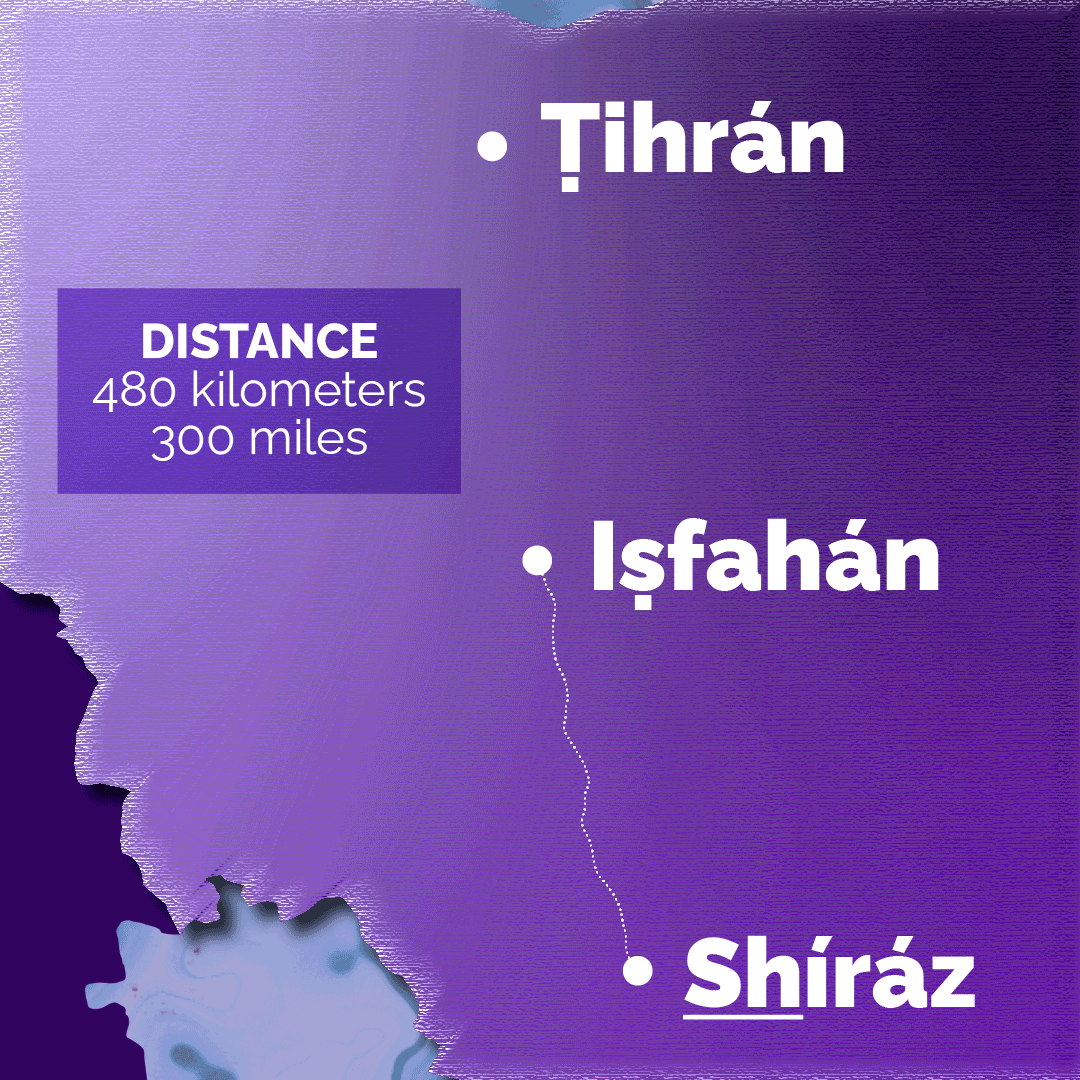

Distance map between Shíráz and Iṣfahán, showing the relationship of the two cities to Ṭihrán. The route is symbolic, as we have no historical information on the route taken by the Báb. © Violetta Zein

When ‘Abdu'l-Hamíd Khán had released the Báb in Shíráz, he had made His release conditional on Him leaving the city.

Two factors seemed to have played a role in the Báb’s decision to travel to Iṣfahán.

On one hand, the Báb had been telling the Bábís of Karbilá and Shíráz to travel to Iṣfahán for months, and Iṣfahán now had a sizeable Bábí population.

It seems the other factor of note in His decision was a favorable response He had received from Manúchihr Khán, the Governor of the city.

On 24 September 1846, the day after the Báb had been taken from His home and had saved the sons of ‘Abdu'l-Hamíd Khán, the Báb left His native city never to return.

Accompanied only by Siyyid Káẓim-i-Zanjání, they rode out to Iṣfahán.

The distance between Shíráz and Iṣfahán is 480 kilometers (300 miles), and in 19th century conditions, traveling by horseback, the journey would have taken the Báb approximately 6 six days, meaning He arrived in view of the city of Iṣfahán sometime at the very end of September 1846.

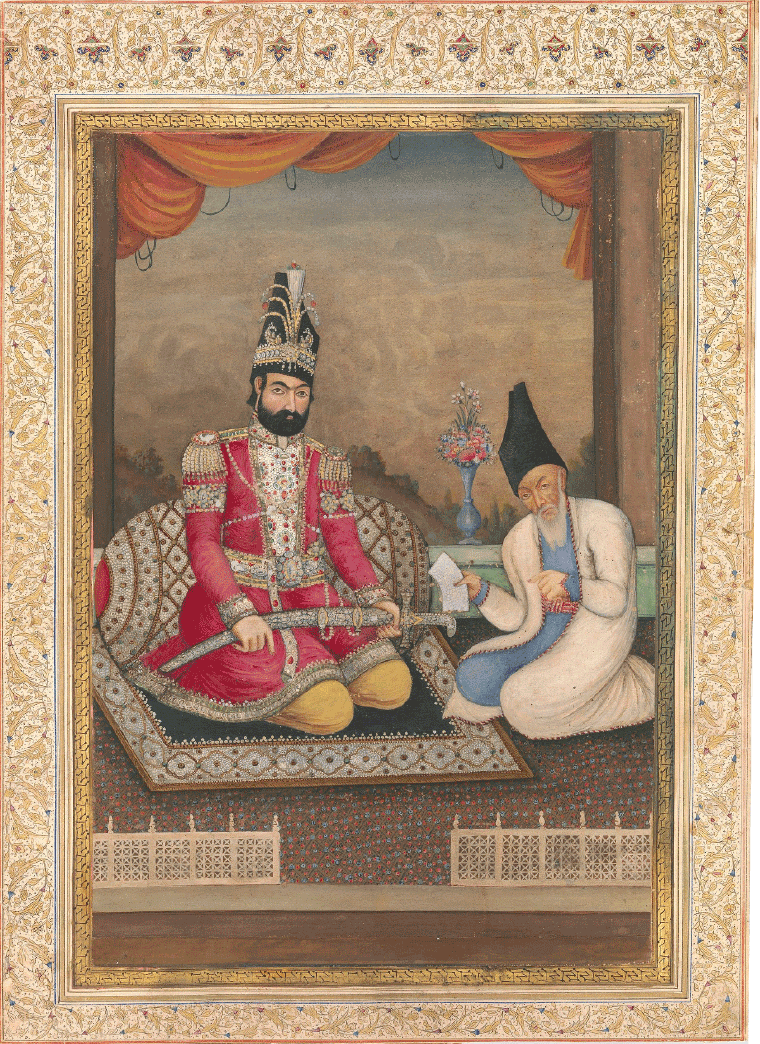

Portrait of Manúchihr Khán, the Governor general of Iṣfahán, on an 1847 mirror case. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The Governor of Iṣfahán, Manúchihr Khán, had started his life out as a Georgian slave, a eunuch. He had risen through the ranks of public service due to his remarkable abilities, and now enjoyed the confidence and favor of Muḥammad Sháh

Manúchihr Khán was considered one of the best administrators of Persia and respected as a just ruler but feared for his cruelty and greediness.

As the Báb approached Iṣfahán, He wrote a tablet to Manúchihr Khán from the outskirts of the city asking him to designate a place for Him to stay. The Báb’s companion, Siyyid Káẓim-i-Zanjání, delivered His letter to the Governor.

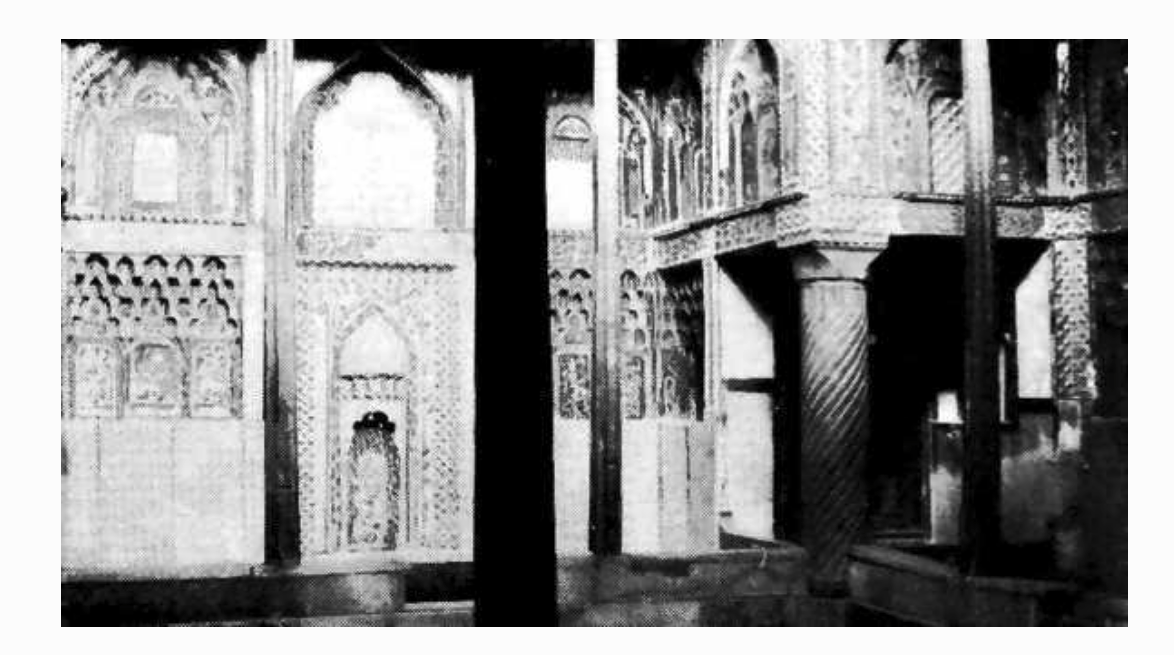

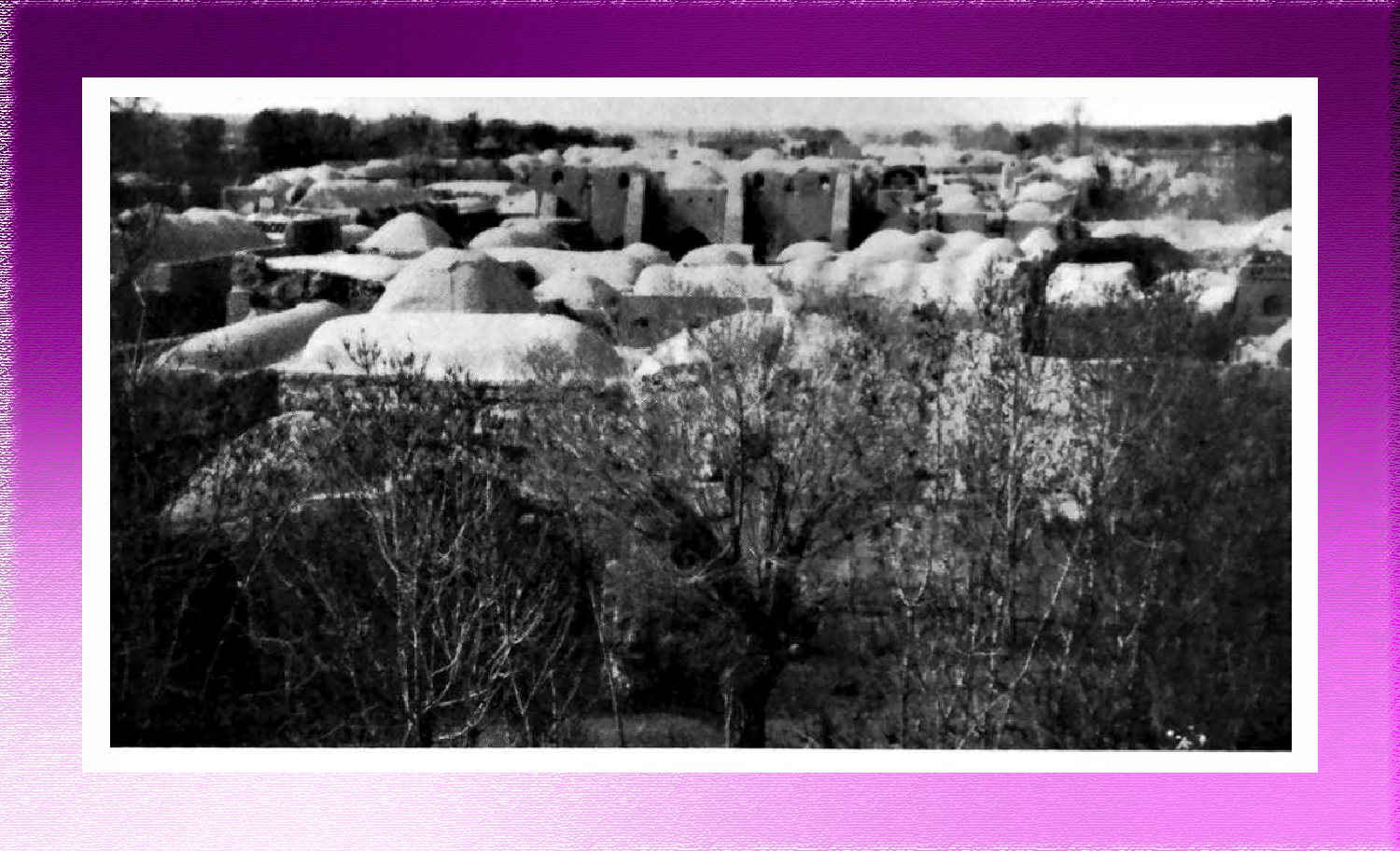

A view of the house of the Sulṭánu'l-‘Ulamá, the Imám-i-Jum'ih, where the Báb spent His first 40 days in Iṣfahán. Source: Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, page 200.

Manúchihr Khán was impressed by the Báb’s message and forwarded it to the Imám-i-Jum'ih (Leader of Friday Prayers) of Iṣfahán—also known as Sulṭánu'l-‘Ulamá—requesting he open his home to the Báb.

The Imám-i-Jum'ih sent his brother with an escort to meet the Báb, and welcomed Him in person at the gates of the city with respect and reverence far beyond the normal marks of hospitality: he went so far as to pour water on the hands of the Báb, a task usually performed by attendants.

By the time the Báb arrived in Iṣfahán, there were already a large number of Bábís in the city, both natives of Iṣfahán and other Bábís which the Báb had directed there from other towns and cities like Karbilá and Shíráz.

It is important to remember that this period of five months in Iṣfahán represents the only period of calm, tranquility, comfort, admiration, and respect which the Báb will experience in His life, after His Declaration, despite the short period of opposition 40 days into His stay.

The Imám-i-Jum'ih was enthralled with the Báb, and one night, after their evening meal, he asked his Guest to compose a commentary for him on Súrih 103 of the Qur’án, one of the shortest chapters called Súrih of V'al-‘Aṣr (Súrih of the Afternoon).

There and then, the Báb picked up His pen and, to the amazement and delight of those who were present, revealed His commentary in a single night, writing with astonishing speed.

By midnight, the Báb had revealed a number of verses equal to a third of the Qur’án dedicated to expounding on the many spiritual implications of the first letter of this chapter of the Qur’án, the letter “váv”, a letter whose importance Shaykh Aḥmad-i-Aḥsá’í had emphasized, and which symbolized the advent of the new cycle of Divine Revelation.

Soon after this, the Báb began to chant the prayer that prefaced His commentary, and those present were utterly entranced by the sweetness of His voice. Almost as if bewitched, they instinctively rose to their feet, along with the Leader of Friday prayers, and reverently kissed the hem of the Báb’s garment.

A cleric named Mullá Muḥammad-Taqíy-i-Hirátí, who was so overcome by the Báb’s voice, said:

“Peerless and unique as are the words which have streamed from this pen, to be able to reveal, within so short a time and in so legible a writing, so great a number of verses as to equal a fourth, nay a third, of the Qur'án, is in itself an achievement such as no mortal, without the intervention of God, could hope to perform.”

In the Súrih of V'al-‘Aṣr, the Báb interprets various parts of the short Qur’ánic súrih, and discusses many fundamental issues in religion including how to recognize spiritual truth, the nature of the human being, the meaning of faith, the nature of good deeds, and the preconditions of spiritual journey.

A memorable portion of the Súrih of the Afternoon is a passage where the Báb interprets the last letter of the name of the Súrih (Rá or “R” for ‘Aṣr) as being a reference to the word raḥmat (grace). In this passage the Báb expounds on the various meanings of the word grace which apply to every level of creation, from the lowest to the highest:

“Then there is the sixth letter of the súrih, Rá’, which referreth first to that universal Grace by which God created the Primal Will, prior to all things, by the Will’s own causation, whereby He ordained It to be the Cause of all essences. [The letter Rá’ also pointeth unto] the Grace of oneness by which God fashioned the souls of all who are embraced by His knowledge in the Book. Next, it hinteth at the universal Grace which descendeth unto the station of Destiny, that surging and bountiful sea within which all the creatures are distinguished...Finally, it indicateth the Mercy that hath encompassed all things…the all-embracing Grace which encompasseth the believer, the unbeliever, and all beings.”

Partial Inventory ID: BB00010

Engraving of a street in Iṣfahán from Jane Dieulafoy, La Perse, la Chaldée et la Susiane, page 275. Source : Archive.org.

The fame of the Báb began to spready quickly among the population of Iṣfahán, soon turning to reverence, with the inhabitants seeming to value any object which had been touched by the Báb as precious: on one occasion, people even stole the water He had used for His ablutions, His most fervent admirers believing that the water had the power to cure their illnesses.

People of all ranks and social classes began to flock to the Imám-i-Jum'ih’s home. Even the Governor, Manúchihr Khán, called on the Báb there, an extremely significant fact.

Manúchihr Khán was the Governor of one of the most important provinces of Persia, accountable to the Sháh himself, and he called on a relatively unknown young Siyyid, something only explainable by the effect the Báb’s Tablet had had on him.

The Báb, who had arrived into his city as a fugitive and an exile, would have a transformative effect on Manúchihr Khán.

An endless stream of visitors started calling on the Báb. Some were curious and wanted to see Him for themselves, others wanted to learn more about the Bábí Faith, and still others wanted to be healed of their illnesses or sufferings.

The Báb revealed Risáliy-i-Ithbát-i-Nubuvvat-i-Kháṣṣih (Epistle on the Proofs of the Prophethood of Muḥammad), also known as the Treatise on Specific Prophethood in Iṣfahán in honour of its Governor, Manúchihr Khán.

One day, in a gathering of the leading clerics of Iṣfahán, Manúchihr Khán asked the Báb to reveal a theological treatise on Nubuvvat-i-Kháṣṣih, the specific station and mission of the Prophet Muḥammad.

Once again, the Báb obliged:

“Which do you prefer, a verbal or a written answer to your question?”

Manúchihr Khán answered:

“A written reply not only would please those who are present at this meeting, but would edify and instruct both the present and future generations.”

The Báb instantly took up His pen to write, and in two hours, He had revealed the Risáliy-i-Ithbát-i-Nubuvvat-i-Kháṣṣih (Treatise on Specific Prophethood), a treatise of 50 pages, superbly reasoned, in which He proved beyond any possible doubt the claim and achievements of Islám, concluding with a masterful dissertation on the subject of the advent of the Qá’im and the return of the Imám Ḥusayn.

In the Treatise on Specific Prophethood, the Báb argues that nothing is accidental with respect to the reality of the Manifestations of God, including the Prophet Muḥammad, and therefore, above and beyond His Revelation (in this case, the Qur’án), every aspect of the life of a Manifestation of God, from the names of His parents to the place and date of His birth, is possessed with spiritual meaning for the sincere seeker of truth.

Manúchihr Khán’s immediate, enthralled response to the assembled divines was:

“Hear me! Members of this revered assembly, I take you as my witnesses. Never until this day have I in my heart been firmly convinced of the truth of Islám. I can henceforth, thanks to this exposition penned by this Youth, declare myself a firm believer in the Faith proclaimed by the Apostle of God. I solemnly testify to my belief in the reality of the superhuman power with which this Youth is endowed, a power which no amount of learning can ever impart.”

Partial Inventory ID: BB00014

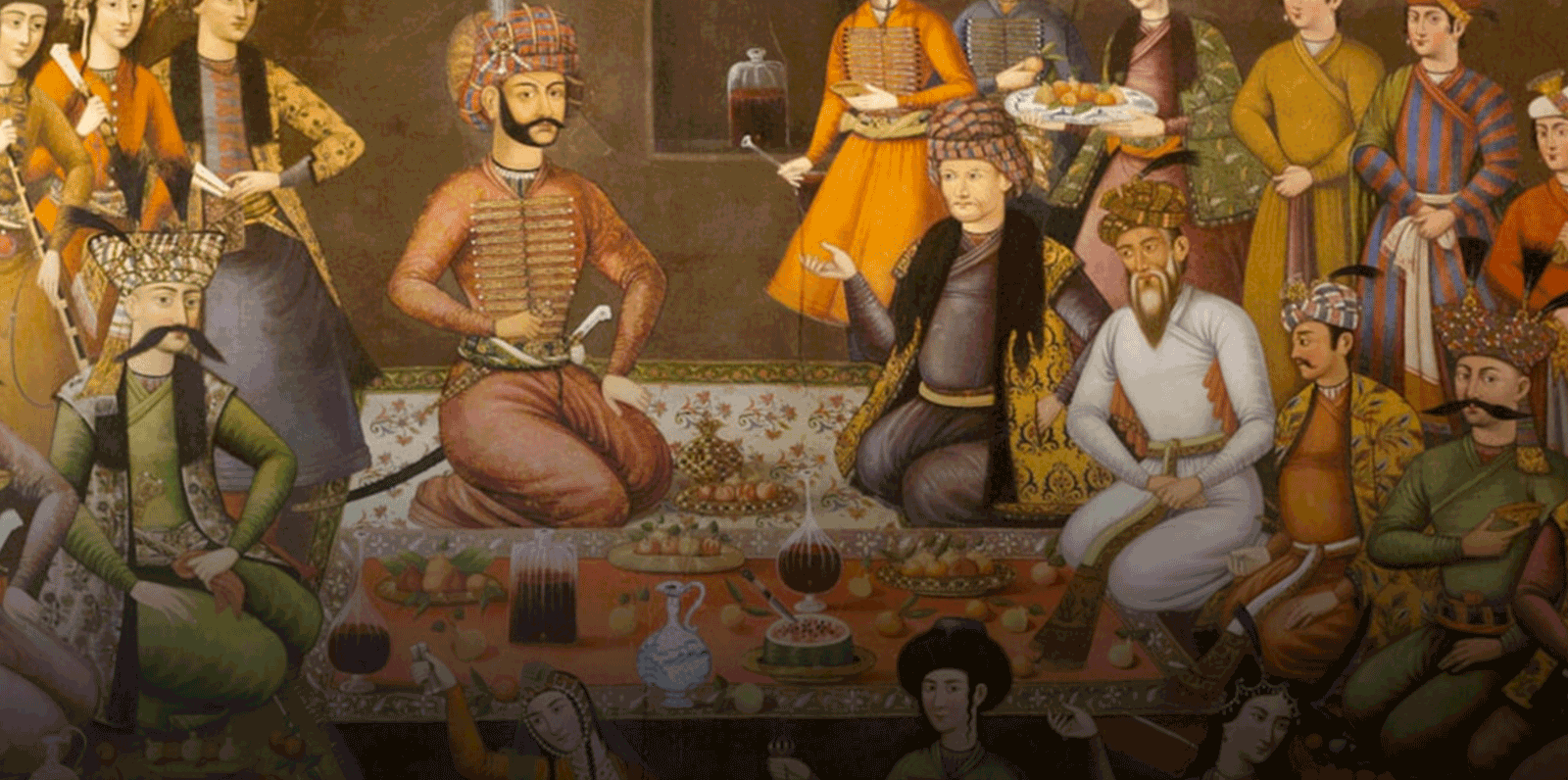

For a story about a dinner in Qajár Iṣfahán, a detail of a Fresco at Chehel Sotoun Palace in Iṣfahán of a dinner with Sháh ‘Abbás. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

One night before the Báb changed residences, a Bábí named Mírzá Ibráhím, invited Him to his home one night for a banquet of unsurpassed magnificence.

Two young brothers of Iṣfahán, Mírzá Muḥammad-Ḥasan and Mírzá Muḥammad-Ḥusayn, who would later be immortalized as the King and the Beloved of the Martyrs served food that night.

At one point during the splendid dinner, Mírzá Ibráhím turned to the Báb and begged Him for an immense favor:

“My brother, Mírzá Muhammad-‘Alí, has no child. I beg You to intercede in his behalf and to grant his heart’s desire.”

The Báb took a portion of the food from His own plate, and handed it to Mírzá Ibráhím, instructing him to take it to Mírzá Muḥammad ‘Alí and his wife:

“Let them both partake of this, their wish will be fulfilled.”

Sometime later in 1847, Mírzá Muḥammad ‘Alí and his wife gave birth to a wonderful baby girl, who showed signs of incredible spirituality from her early childhood. We know this girl better through the name Bahá'u'lláh conferred upon her shortly before she married 'Abdu'l-Bahá: Munírih Khánum.

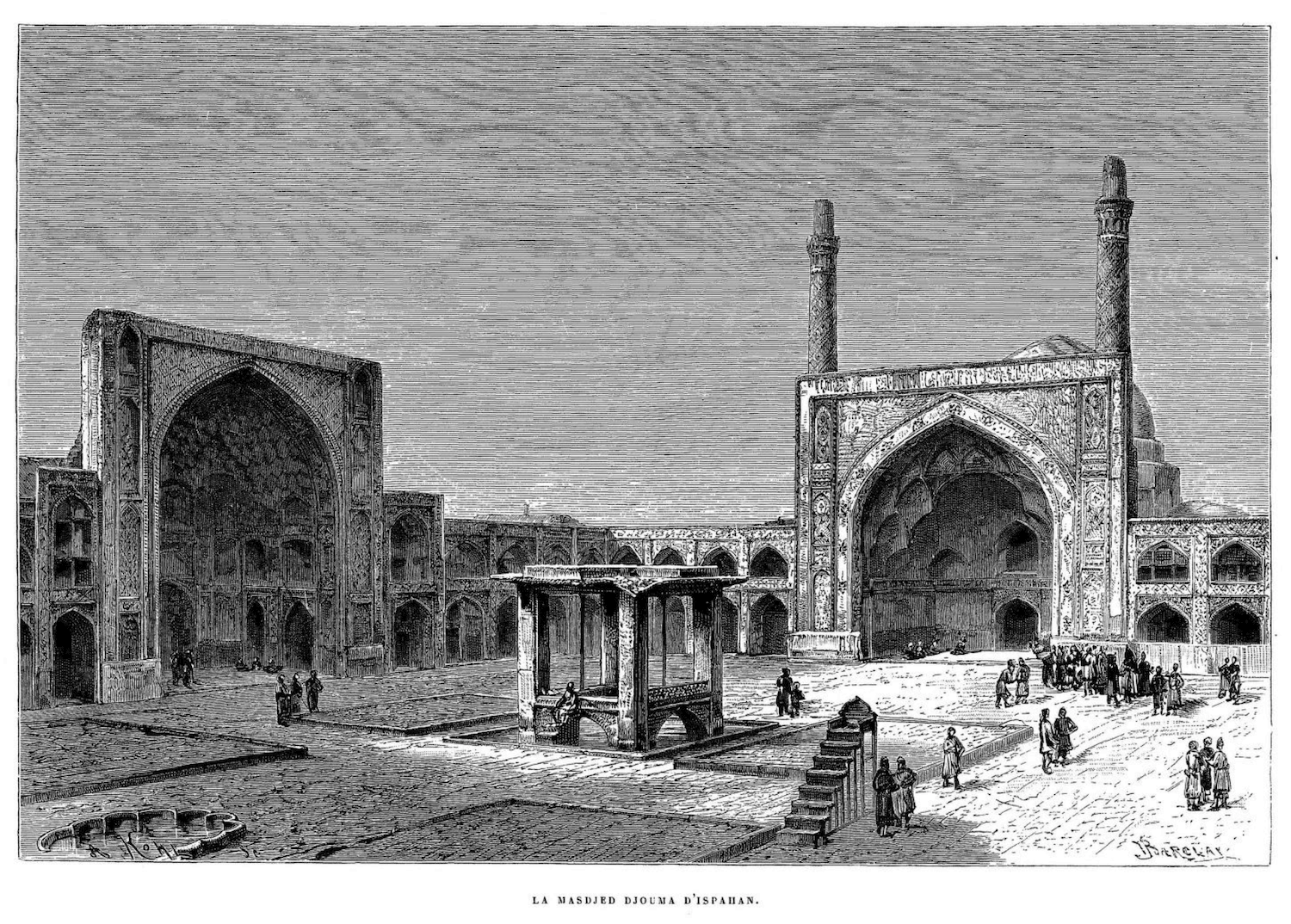

An engraving of Masjid-i-Ju'míh, where the Báb prayed in Iṣfahán. Source: Jane Dieulafoy, La Perse, la Chaldée et la Susiane, page 307. Source : Archive.org.

It was inevitable that the Báb’s radiance, the perfection of His character, His superhuman knowledge, His intellectual brilliance, and His theological superiority despite His lack of formal academic training, would attract jealousy and envy.

The clerics of Iṣfahán started opposing Him.

Áqá Muḥammad-Mihdí denounced, insulted and disparaged the Báb from his pulpit, and glowing news of the Báb’s stay in Iṣfahán reached the Prime Minister, Ḥájí Mírzá Áqásí, who immediately wrote to the Imám-i-Jum'ih, reprimanding him for having given the Báb his hospitality. Ḥájí Mírzá Áqásí was mainly afraid that Manúchihr Khán, who had significant influence with Muḥammad Sháh, might be tempted to arrange a meeting between the Báb and the sovereign.

After the letter from Ḥájí Mírzá Áqásí, the Imám-i-Jum'ih took no steps in opposing the Báb, but limited the numbers of visitors He received.

After the Báb had been in Iṣfahán for 40 days, staying with the Imám-i-Jum'ih, more and more clerics started opposing the Báb, and Manúchihr Khán thought he had found a way to silence them.

In an effort to dispel the ‘ulamá’s concerns and answer their questions Manúchihr Khán invited them to meet the Báb in his home and present their arguments.

Ḥájí Siyyid Asadu'lláh, an influential cleric, refused the invitation and encouraged the rest of his compatriots to do the same, saying:

“I have sought to excuse myself and I would most certainly urge you to do the same. I regard it as most unwise of you to meet the Siyyid-i-Báb face to face. He will, no doubt, reassert his claim and will, in support of his argument, adduce whatever proof you may desire him to give, and, without the least hesitation, will reveal as a testimony to the truth he bears, verses of such a number as would equal half the Qur'án. In the end he will challenge you in these words: 'Produce likewise, if ye are men of truth.' We can in no wise successfully resist him. If we disdain to answer him, our impotence will have been exposed. If we, on the other hand, submit to his claim, we shall not only be forfeiting our own reputation, our own prerogatives and rights, but will have committed ourselves to acknowledge any further claims that he may feel inclined to make in the future.”

Only one of the clerics also declined the invitation, and the rest of the ‘ulamás of Iṣfahán met the Báb in Manúchihr Khán’s home.

One cleric asked the Báb to elucidate philosophical concepts in a work called the Ḥikmatu'l-‘Arshíyyah (“Divine Philosophy”). The Báb's answers, though couched in simple terms, were too complex for the cleric to grasp.

The next cleric asked the Báb obscure questions of Islamic law, and finding himself unable to grasp the Báb’s explanation, began to assault Him verbally.

The exchange of questions and answers ended fruitlessly, and was not the neat solution to the opposition to the Báb that Manúchihr Khán had hoped. In fact, it probably worsened the situation because the Báb’s answers were too profound for the clerics to grasp and it would have been humiliating for them to acknowledge it.

Manúchihr Khán sensed the mood of the audience and put a stop to the questions, offering the Báb safe harbor in his home, and the antagonism of the clerics started up again.

For a story on Persian clerics in Isfahán, here is a photograph of a group of 19th century Persian ulamás. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The clerics of Iṣfahán became deeply concerned with the Báb’s influence. After just 40 days in their city, the Báb was highly revered, and they began fearing to lose their influence, like their colleagues in Shíráz.

No less than 70 of the ‘ulamás of Iṣfahán issued fatwás calling for the Bab’s execution. All of them registered complaints with Muḥammad Sháh and Ḥájí Mírzá Áqásí.

The Báb would have been executed in late October or early November 1846 in Iṣfahán if it hadn’t been for a very unusual bureaucratic piece of paper that saved His life in the most unexpected way.

What saved the Báb’s life was a diplomatic fatwá issued by His former host, the Imám-i-Jum'ih—the Leader of Friday Prayers. In his moderately-worded fatwá, the Imám-i-Jum'ih, characterized the Báb as insane and testified that he had not noticed Him behaving in any unorthodox way when He was his guest for 40 days. The Imám-i-Jum'ih appened his moderately-worded fatwá to the other 70 fatwás demanding the Báb’s death.

Despite his great affection for the Báb, the Imám-i-Jum'ih was afraid for his position, and although his fatwá declared the Báb insane, it was also the piece of paper that saved His life, the text of which read in part:

“I testify that in the course of my association with this youth I have been unable to discover any act that would in any way betray his repudiation of the doctrines of Islam. On the contrary, I have known him as a pious and loyal observer of its precepts. The extravagance of his claims, however, and his disdainful contempt for the things of the world, incline me to believe that he is devoid of reason and judgment.”

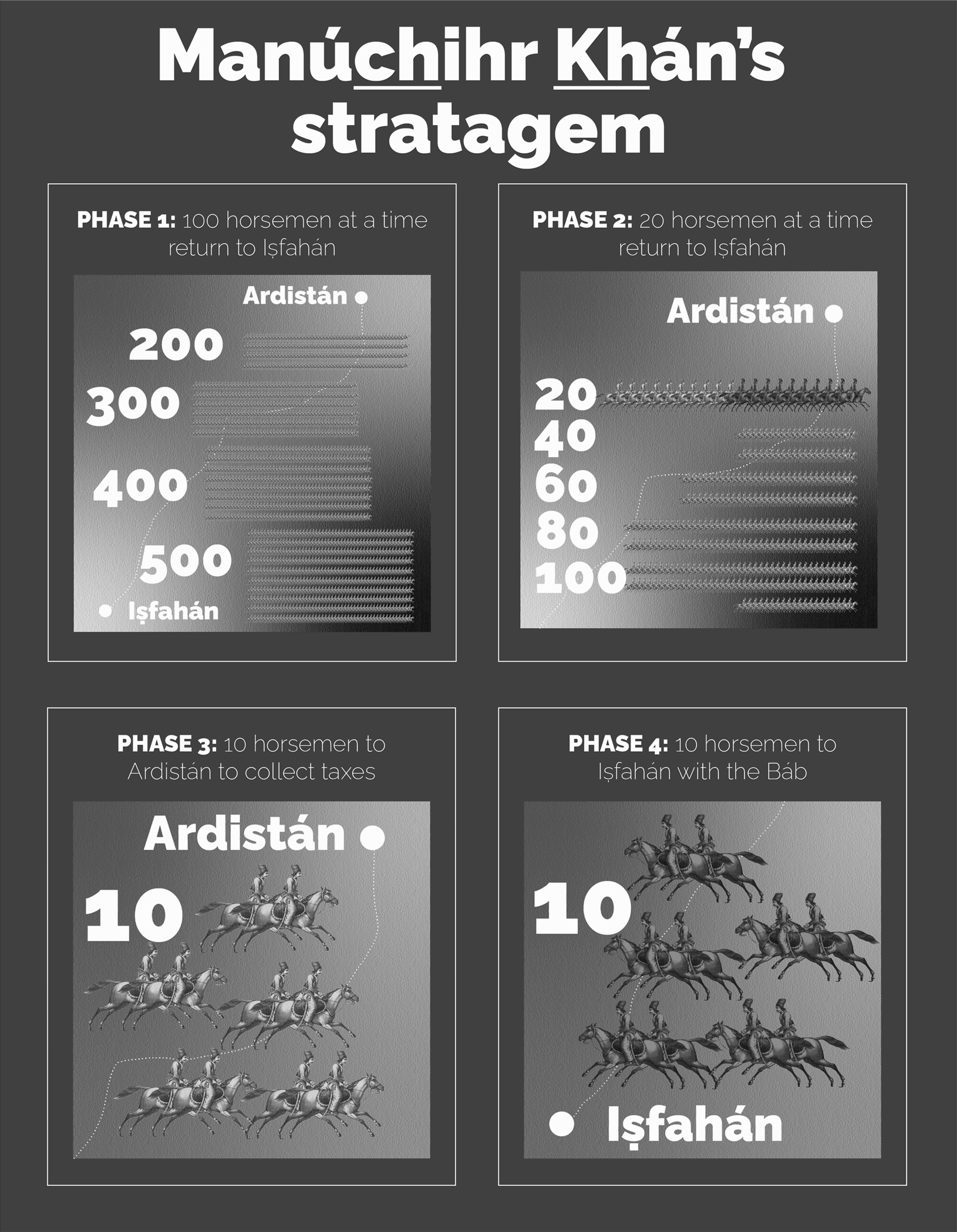

“Manúchihr Khán’s stratagem”: An infographic of Manúchihr Khán’s strategy to fake the Báb’s departure from Iṣfahán and return Him safely to the city under cover of darkness, detailed in the story below. © Violetta Zein

Ḥájí Mírzá Áqásí had already, by this time, asked Manúchihr Khán to deliver the Báb to him in Ṭihrán, but the Governor of Iṣfahán had been won over by the Báb, and could not imagine delivering Him into the cruel hands of Ḥájí Mírzá Áqásí.

He devised a very complex and ingenious trick to save the Báb.

Manúchihr Khán arranged for the Báb to be publicly escorted out of Iṣfahán under full view of all the inhabitants, escorted by 500 horsemen, and had given the following instructions:

- 100 horsemen should return to Iṣfahán every 10 kilometers (6 miles);

- After this, he had instructed the chief of the remaining 100 soldiers to dismiss 20 of his horsemen every few kilometers/miles, ordering them to return to Iṣfahán;

- When only 20 soldiers remained, the chief was to dispatch 10 of them to Ardistán to collect taxes;

- The remaining 10 soldiers, his most loyal and dependable, should bring back the Báb to Iṣfahán by an untraveled road, under cover of darkness, so that Manúchihr Khán could welcome Him back into the city before dawn.

Manúchihr Khán himself waited on the Báb, served His meals, made sure He had everything He needed, and was safe and comfortable.

The Báb would stay with Manúchihr Khán for four months, the calmest and most peaceful ones of His entire ministry.

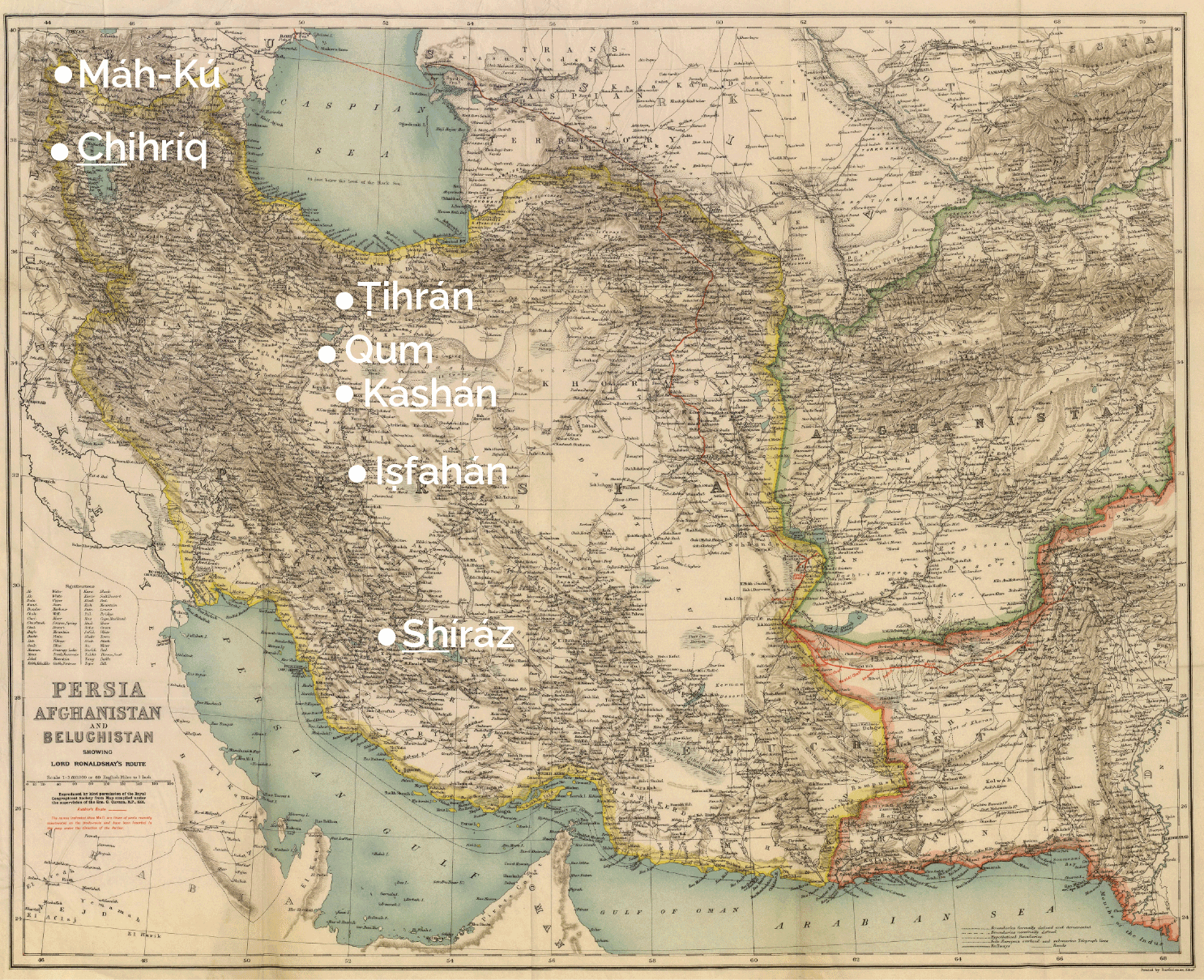

19th century map of Persia showing all the locations mentioned in the story below and adding Shíráz for reference. Source for the map: Wikimedia Commons.

After Manúchihr Khán saved the Báb in such an ingenious way, wild rumors began to circulate that the Báb had been executed in Ṭihrán.

The Bábís did not know what to believe, so the Báb allowed three of them, Mullá `Abdu'l-Karím-i-Qazvíní, Siyyid Ḥusayn-i-Yazdí and Shaykh Ḥasan-i-Zunúzí, to be brought to meet Him at the Governor’s home.

He entrusted them with the task of transcribing His Writings, then asked them to inform, the Bábís to disperse north to Káshán, or Qum or Ṭihrán.

At one point during His stay in Iṣfahán, Siyyid Ḥusayn asked the Báb a question, ostensibly about His future, and the Báb replied something Siyyid Ḥusayn did not understand:

“For a period of no less than nine months, we shall remain confined in the Jabál-i-Basít, from whence we shall be transferred to the Jabál-i-Shadíd.”

The Báb had just told Siyyid Ḥusayn about the two places where He would be confined for the last three years of His earthly life: Máh-Kú Jabál-i-Basít (“The Open Mountain”), and Chihríq, or Jabál-i-Shadíd (“The Grievous Mountain”).

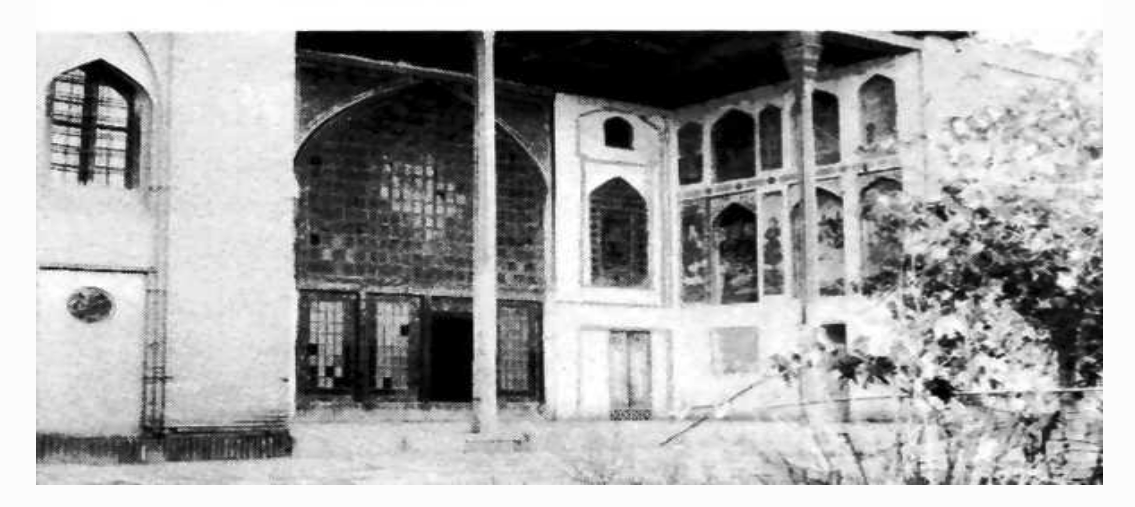

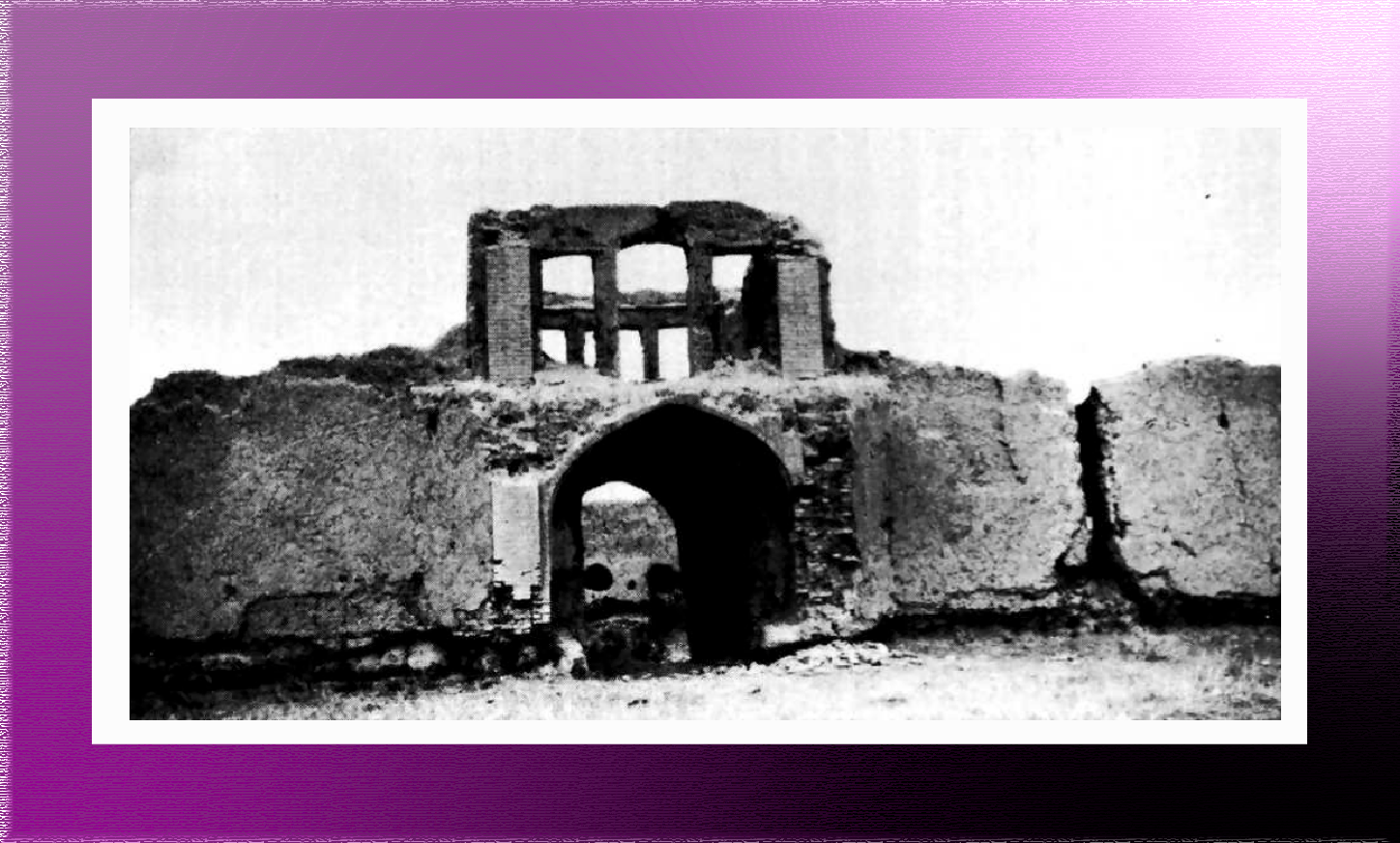

Manúchihr Khán’s home in Iṣfahán, where the Báb was a Guest during the last four months of His stay in the city, until the death of His host. Source: Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, page 206.

Approximately three months before his death, Manúchihr Khán, the Governor of Iṣfahán, offered the Báb his immense fortune, valued at 40 million francs. In terms of purchasing power, 40 million francs in 1847 could buy a person what $1.8 billion offers someone today. It was an enormous, unbelievable fortune.

Seated with the Báb he confided in Him that he wanted to give everything to the Bábí Faith, and was sure the kings of the earth would join the Cause:

“The almighty Giver has endowed me with great riches. I know not how best to use them. Now that I have, by the aid of God, been led to recognise this Revelation, it is my ardent desire to consecrate all my possessions to the furtherance of its interests and the spread of its fame. It is my intention to proceed, by Your leave, to Tihrán, and to do my best to win to this Cause Muhammad Sháh, whose confidence in me is firm and unshaken. I am certain that he will eagerly embrace it, and will arise to promote it far and wide…Finally, I hope to be enabled to incline the hearts of the rulers and kings of the earth to this most wondrous Cause and to extirpate every lingering trace of that corrupt ecclesiastical hierarchy that has stained the fair name of Islám.”

Above and beyond his fortune, Manúchihr Khán took off his rings and offered them to the Báb, and gave the Báb the resources of his army to march to Ṭihrán and meet Muḥammad Sháh. Manúchihr Khán also had a plan to wed the Báb to one of the sisters of Muḥammad Sháh.

The Báb responded with a touching letter on 6 December 1846 in which He not only reassured and comforted His dear and loyal friend but also gave him the gift of knowing he had 99 days left to live:

“May God requite you for your noble intentions. So lofty a purpose is to Me even more precious than the act itself. Your days and Mine are numbered, however; they are too short to enable Me to witness, and allow you to achieve, the realisation of your hopes. Not by the means which you fondly imagine will an almighty Providence accomplish the triumph of His Faith. Through the poor and lowly of this land, by the blood which these shall have shed in His path, will the omnipotent Sovereign ensure the preservation and consolidate the foundation of His Cause. That same God will, in the world to come, place upon your head the crown of immortal glory, and will shower upon you His inestimable blessings. Of the span of your earthly life there remain only three months and nine days, after which you shall, with faith and certitude, hasten to your eternal abode.”

Manúchihr Khán, as his life was ending, had realized everything he had, his wealth and estates, had been the product of oppression, and spent as much time as he could in the Báb’s company. One day, he confided his fears in the Báb:

“As the hour of my departure approaches, I feel an undefinable joy pervading my soul. But I am apprehensive for You, I tremble at the thought of being compelled to leave You to the mercy of so ruthless a successor as Gurgín Khán. He will, no doubt, discover Your presence in this home, and will, I fear, grievously ill-treat You.”

The Báb had accepted both Manúchihr Khán’s repentance and his wealth, and had returned his riches to him to use as he saw fit until his death. And now He alleviated His faithful friends’ fears:

“Fear not, I have committed Myself into the hands of God. My trust is in Him. Such is the power which He has bestowed upon Me that if it be My wish, I can convert these very stones into gems of inestimable value, and can instil into the heart of the most wicked criminal the loftiest conceptions of uprightness and duty. Of My own will have I chosen to be afflicted by My enemies, ‘that God might accomplish the thing destined to be done.’”

Manúchihr Khán died on 4 March 1847.

During the course of His sojourn in Iṣfahán, the Báb revealed a Tablet in honor of Mírzá Sa‘íd-i-Ardistání, who had asked Him three philosophical questions about

This Tablet is one of the Báb’s most complex philosophical Writings, as He expounds on three highly mystical, abstruse, enigmatic concepts which Mírzá Sa‘íd-i-Ardistání had asked him about, namely the concept of the True Indivisible Being (Basíṭu’l-Ḥaqíqah), the question of the eternity and the creation of the world, and the issue of the emanation of plurality out of the One.

As to the first question, the Báb goes into an intricate explanation as to why the current beliefs of contemporary philosophers are wrong about these topics, analyzing their logical error:

“Verily, their grievous sin is due to their use of analogy in their desire to comprehend the essential properties of the Essence at the level of the contingent beings. Exalted be God above such a notion!”

The Báb then uses the same method to expound on the discussion of origination versus pre-existence, arguing that the Primal Will of God represents His absolute Pre-existence in the realm of creation. The Primal Will is originated, but not originated in time, and has no beginning or end:

“Know thou, of a certainty, that the Pre-existence of the Eternal Essence hath ever been Himself, and His Eternity is naught but His Essence. Nothing existeth besides Him, much less that it could be capable of explaining His Pre-existence…Therefore, any praise made by His creation, and any description comprehended by His servants, is the outcome of their limited creation and the attributes that their minds may invent within the created realm…Verily, the Source of the originated is the Primal Creation, which God hath created for Itself, by Itself; no other mention can ever be made besides It…”

Partial Inventory ID: BB00064

At some point between September 1846 and March 1847 (we do not have an exact date) the Báb revealed a Treatise on Singing called Risálah Fi’l-Ghiná’ in honor of Sulṭánu’dh-Dhákirín.

The way the Báb treats this subject is fascinating, because it is not a theological discussion of Islamic law regarding singing and music.

Instead, the Báb approaches the topic of singing and music philosophically by defining instead the philosophical conditions of actions, moral or immoral and establishing the dual nature of the human being, at once possessing existence and essence, or divine revelation and specific determination.

As with every other action undertaken by a human being, singing or music can be moral or immoral depending on the intention of the person doing the singing or playing the music, and the function of the act.

Partial Inventory ID: BB00037

Portrait of Manúchihr Khán, the Governor general of Iṣfahán, on an 1847 pen box. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

After the death of Manúchihr Khán, although he had willed all of his earthly possessions to the Báb, his nephew and successor Gurgín Khán, took everything. Gurgín Khán informed Muḥammad Sháh that the Báb was still in Iṣfahán, and that he had been protected for four months by Manúchihr Khán.

The Sháh never doubted Manúchihr Khán, certain that his faithful follower had kept the Báb safe for a meeting with him, and ordered that the Báb be brought to Ṭihrán, giving orders that He should not be recognized during the journey.

In Ṭihrán, Ḥájí Mírzá Áqásí, the Sháh’s Prime Minister was waiting for the Báb. Shoghi Effendi called Ḥájí Mírzá Áqásí the Antichrist of the Bábí Revelation. He had hated the Báb from the earliest reports of His Cause and would do everything in his power to prevent a meeting between Muḥammad Sháh and the Báb.

The Báb asked his companion Siyyid Ḥusayn-i-Yazdí to ride ahead and wait for Him in Káshán.

Five photos of the Báb’s stay in Káshán: Photo 1: Two views of the gate of ‘Aṭṭár; Photo 2: A general view of the city; Photos 3 and 4: Two views of the house of Ḥájí Mírzá Jání, where the Báb stayed in Káshán; Photo 5: The room in which the Báb stayed. Source: Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, pages 217-222.

Gurgín Khán followed Muḥammad Sháh’s intructions and entrusted the Báb to the custody of Muḥammad Big-i-Chápárchí (“the chief courier”). Muḥammad Big belonged to the sect of Ahl-i-Ḥaqq (the People of Truth), also known as the ‘Alíyu'lláhí, a community well-respected for their tolerance, liberalism and rectitude.

The horse-mounted guards under Muḥammad Big’s command who were to escort the Báb on His northern journey were all Nuṣayrí, a sect almost identical to the ‘Alíyu'lláhí and well-known for their integrity.

Their first stop on the way to Ṭihrán was Káshán, where they were met by a Bábí merchant, Ḥájí Mírzá Jání, who was waiting for them on 20 March 1847, forewarned of the Báb’s arrival by a dream.

As Ḥájí Mírzá Jání went to kiss the Báb’s stirrup, the Báb welcomed Him and spoke almost the exact words the merchant had heard in his dream:

“We are to be your Guest for three nights. To-morrow is the day of Naw-Rúz; we shall celebrate it together in your home.”

A colleague of Muḥammad Big’s refused to allow the Báb to stay in Káshán because they had orders He was not to enter any city until they reached Ṭihrán. After a long argument, Muḥammad Big managed to persuade the man, and Ḥájí Mírzá Jání accompanied the Báb to his home, where he had already made all the preparations for a feast, based on his previous night’s dream.

When Ḥájí Mírzá Jání offered to pay the expenses of the three-day halt in Káshán for His escort, the Báb dissuaded him:

“It is unnecessary, but for My will, nothing whatever could have induced them to deliver Me into your hands. All things lie prisoned within the grasp of His might. Nothing is impossible to Him. He removes every difficulty and surmounts every obstacle.”

Siyyid Ḥusayn-i-Yazdí, the Seventh Letter of the Living, who had arrived in Káshán ahead of them, came out to transcribe a Tablet the Báb revealed for Ḥájí Mírzá Jání, and offer prayers on behalf of His gracious host, supplicating God to illumine his heart with divine knowledge. After the Báb’s departure, the previously unschooled Ḥájí Mírzá Jání became endowed with such power in his speech that he could silence any opponent.

Three views of the Báb’s journey from Iṣfahán to Qumrúd: Photos 1 and 2: Two views of Qum, showing the Ḥaram-i-Ma'súmih, the Holy Shrine of Fáṭimih, the sister of the Eighth Imám; Photo 3: The village of Qumrúd. Source: Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, pages 223-225.

The Báb and His escort continued on to Ṭihrán two days after Naw-Rúz, on the road to Qum.

When they arrived at Qum, although they had been ordered not to stop in any city, the guards offered the Báb the choice to enter it, but He declined, preferring to continue in the countryside.

They stopped in a village called Qumrúd, where they stayed one night. The entire population of Qumrúd was of the same faith as Muḥammad Big and his horsemen, and the Báb was touched by the warmth and spontaneity of their welcome.

Before leaving their pleasant company, the Báb cheered the townsfolk with assurances of His love and appreciations and prayed for blessings from God on their behalf.

Ruins of the fortress of Kinár-Gird. Source: Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, page 225.

On the afternoon of 28 March 1847, the Báb and His escort arrived at the fortress of Kinár-Gird, 45 kilometers (28 miles) away from Ṭihrán, and their long journey seemed at its end.

But that was not to be the case.

Ḥájí Mírzá Áqásí had sent instructions ahead of their arrival for Muḥammad Big and ordered him to bring the Báb to a village he owned called Kulayn, instead of Ṭihrán.

In Kulayn there was no suitable house for the Báb and Muḥammad Big ordered a tent to be pitched for Him outside the village in a beautiful spot inside an orchard.

It was in this idyllic surrounding of nature and trees, with a running brook and lush vegetation, that the Báb spent 20 days.

Four Bábís soon joined the Báb: Siyyid Ḥusayn-i-Yazdí and his brother Siyyid Ḥasan, Mullá ‘Abdu'l-Karím-i-Qazvíní and Shaykh Ḥasan-i-Zunúzí.

Closeup view of the village of Kulayn. Source: Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, page 226.

On 1 April 1847, three days after the Báb had arrived, two Bábís arrived in Kulayn bearing a gift from Bahá'u'lláh.

Bahá'u'lláh’s parcel included a sealed letter and some gifts which brought great joy to the Báb in a moment of loneliness and imprisonment. His face glowed with joy and He effusively thanked the believer who had delivered Him the package.

Bahá'u'lláh’s gift would have a profound impact on the Báb, who kept the glow of exultation from His contact with “Him Whom God shall make manifest” for nearly two years until He received news of the massacre at Shaykh Ṭabarsí, in the summer of 1849.

Distance view of the village of Kulayn, for a story about the Báb walking back towards camp. Source: Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, page 226.

One night in Kulayn, all the Bábís who were sleeping around the tent of the Báb were suddenly awoken by the trampling of horses: the Báb had disappeared from His tent!

Muḥammad Big refused to panic, he calmed his troops saying:

“Why feel disturbed? Are not His magnanimity and nobleness of soul sufficiently established in your eyes to convince you that He will never, for the sake of His own safety, consent to involve others in embarrassment? He, no doubt, must have retired, in the silence of this moonlit night, to a place where He can seek undisturbed communion with God. He will unquestionably return to His tent. He will never desert us.”

Muḥammad, followed by the Bábís and his troops, started walking in the direction of Ṭihrán to find the Báb. They had covered a few kilometers when they saw in the dim light of the early dawn, the figure of the Báb, walking from the direction of Ṭihrán.

The Báb’s countenance had completely changed, He exuded incredible serenity, and His face was radiant, and when He asked Muḥammad Big:

“Did you believe Me to have escaped?”

Overwhelmed by the power in the Báb's words, Muḥammad Big was overwhelmed and he threw himself at His feet and cried out:

“Far be it from me to entertain such thoughts!”

Painting of Ḥájí Mírzá Áqásí, Grand Vizir (Prime Minister) to Muḥammad Sháh, and Naṣiri'd-Dín Sháh. Source: The British Museum.

When the Báb had been in Kulayn for three weeks, He wrote a Tablet to Muḥammad Sháh asking for a meeting and describing in detail the cruelty of Ḥusayn Khán, the Governor of Fars, and praised the kindness of Manúchihr Khán.

The Báb’s letter arrived just as two major events were preoccupying Muḥammad Sháh. He was increasingly worried about the menace of rebellion in the region of Khurásán, and he was about to leave Ṭihrán for the countryside.

Ḥájí Mírzá Áqásí, whom Shoghi Effendi called the “Antichrist of the Bábí Revelation,” played heavily on both of his fears to prevent the meeting between the Sháh and the Báb from ever taking place.

The Prime Minister reportedly told his sovereign that to meet with the Báb on the eve of his departure from the capital would destabilize the entire kingdom. He argued that the Muslim clerics in Ṭihrán would be just as easily taken in by the Báb’s charisma as those of Iṣfahán, and would likely be more lenient towards Him if they met Him in person, on account of His pure lineage.

Ḥájí Mírzá Áqásí warned the Sháh that the mere presence of the Báb in Ṭihrán would be “the cause of the gravest trouble and the greatest mischief.”

In the end, he told the Sháh that the wisest course of action was to send the Báb to Máh-Kú, all the way at the northwestern end of the kingdom, as far away as possible from Ṭihrán, and to wait until the Sháh had returned to the capital before addressing the Báb’s request of an audience.

Thanks to Ḥájí Mírzá Áqásí’s scheming and manipulation, the Báb would never meet the Sháh.

A mid-19th century portrait showing both characters referenced in the story below: Muḥammad Sháh and the scheming Ḥájí Mírzá Áqásí, his Prime Minister. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

When the Báb had been in Kulayn for three weeks, He wrote a Tablet to Muḥammad Sháh asking for a meeting.

Ḥájí Mírzá Áqásí, whom Shoghi Effendi called the “Antichrist of the Bábí Revelation,” discouraged the Sháh, manipulating the sovereign’s fear of a rebellion in Khurásán and using the pretext that the Sháh was about to leave Ṭihrán, with these words.

Tainted by Ḥájí Mírzá Áqásí’s influence, the Sháh responded to the Báb’s request in these terms:

“Since the royal train is on the verge of departure from Ṭihrán, to meet in a befitting manner is impossible. Do you go to Máh-Kú and there abide and rest for a while, engaged in praying for our victorious state; and we have arranged that under all circumstances they shall shew you attention and respect. When we return from travel we will summon you specially.”

When he ordered the Báb confined in Máh-Kú, Ḥájí Mírzá Áqásí was employing a definite strategy, adapted to this expansive, proclamatory stage of the Bábí movement.

He was sending the Báb, the leader of that movement, to the most remote and unfamiliar place He had ever experienced: northwestern Ádhirbáyján, a place peopled by Sunní, not Shí’ah, people who spoke Turkish, and not Persian.

Máh-Kú was meant to isolate, silence, alienate the Báb and keep Him as far away from His followers as possible.

Once Ḥájí Mírzá Áqásí exiled the Báb to the far ends of Persia in Máh-Kú, the Revelation of the Báb now culminated in its third, legislative stage, which would encompass the remainder of the Báb’s Writings until the end of His ministry.

The third stage of the Báb’s Revelation followed the first philosophical stage, from 23 May 1844 and before until January 1846, and the second, philosophical stage of the Báb’s Revelation from January 1846 to April 1847.

The legislative stage of the Bábí Revelation encompasses philosophical and interpretive works with one major addition: a recurring theme in the Báb’s Revelation from 1847 to 1850 is the theme of the Promised One, “Him Whom God shall make manifest.”

Bahá'u'lláh’s advent is the over-arching theme of the Báb’s entire Revelation but His allusions and prophecies intensify with the legislative stage.

REFERENCES FOR PART VIII

24 – end of September 1846: The Báb’s journey to Iṣfahán

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, pages 103-105.

Baharieh Rouhieh Ma’ani, Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees, page 13-15.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, page 198.

Information about 19th century travel conditions.

Fereydun Vahman (Editor),The Bab and the Babi Community of Iran (2020), Chapter 1: The Báb: A Sun in a Night Not Followed by Dawn by Fereydun Vahman.

End of September 1846: The Báb’s arrival in Iṣfahán

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, pages 108-110.

Fereydun Vahman (Editor),The Bab and the Babi Community of Iran (2020), Chapter 1: The Báb: A Sun in a Night Not Followed by Dawn by Fereydun Vahman.

Forty days in the home of the Imám-i-Jum’ih

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, pages 108-110.

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, page 110.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Nader Saiedi, Gate of the Heart: Understanding the Writings of the Báb, pages 34 and 116.

Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, pages 202-203.

The fame of the Báb spreads in Iṣfahán

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, pages 110-111.

REVELATION: Risáliy-i-Ithbát-i-Nubuvvat-i-Kháṣṣih (Treatise on Specific Prophethood)

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, page 111.

Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, pages 202-204.

Nader Saiedi, Gate of the Heart: Understanding the Writings of the Báb, page 34.

The Báb gives a child to the parents of Munírih Khánum

Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, pages 208-209.

After 40 days: Opposition in Iṣfahán

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, pages 111-113.

The Báb: A Sun in a Night Not Followed by Dawn by Fereydun Vahman.

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, page 113.

Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, page 209.

Fereydun Vahman (Editor),The Bab and the Babi Community of Iran (2020), Chapter 1: The Báb: A Sun in a Night Not Followed by Dawn by Fereydun Vahman.

Manúchihr Khán’s stratagem to protect the Báb

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, pages 113-114.

The Báb’s instructions to the Bábís

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, page 114.

Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, page 243.

6 December 1846 – 4 March 1847: Manúchihr Khán’s will and testament

Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, pages 2012-214.

Nader Saiedi, Gate of the Heart: Understanding the Writings of the Báb, page 34.

REVELATION: Sometime during the Báb’s sojourn in Iṣfahán: Risálah Fi’l-Ghiná’ (Treatise on Singing)

Nader Saiedi, Gate of the Heart: Understanding the Writings of the Báb, pages 34-35.

After 4 March 1847: The Báb is called to Ṭihrán

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, pages 116-117.

20 – 22 March 1847: Káshán: First stop on the Báb’s journey to Ṭihrán

Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, pages 217-218.

Between 22 – 28 March 1847: A kind welcome in Qumrúd

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, page 119.

Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, pages 223-224.

28 March– 17 April 1847: Twenty peaceful days

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, pages 119-121.

Nabíl, The Dawn-Breakers, pages 224-228.

REVELATION: April 1847 – July 1850: Third stage of Revelation: Legislative

Nader Saiedi, Gate of the Heart: Understanding the Writings of the Báb, pages 27-28.

1 April 1847: A message from Bahá’u’lláh

Nabíl, The Dawn-Breakers, pages 224-228.

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, pages 119-121.

Nabíl, The Dawn-Breakers, pages 224-228.

The Báb requests a meeting with the Sháh

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, pages 121-123.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By, for the reference to the antichrist of the Bábí Revelation.

Fereydun Vahman (Editor),The Bab and the Babi Community of Iran (2020), Chapter 1: The Báb: A Sun in a Night Not Followed by Dawn by Fereydun Vahman.

After 17 April 1847: Perpetual imprisonment

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, pages 121-123.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By, for the reference to the antichrist of the Bábí Revelation.

Fereydun Vahman (Editor),The Bab and the Babi Community of Iran (2020), Chapter 1: The Báb: A Sun in a Night Not Followed by Dawn by Fereydun Vahman.

24 – end of September 1846: The Báb’s journey to Iṣfahán

24 – end of September 1846: The Báb’s journey to Iṣfahán