Written and illustrated by Violetta Zein

This part covers the life of the Báb at the age of 29 in 1848.

“Inhospitable”: A digital recreation of an aerial photograph of the mountainous region of Chihríq, made to emphasize the inhospitability of the region. © Violetta Zein.

Ḥájí Mírzá Áqásí had been sure that exiling the Báb to Máh-Kú would snuff out his charisma and cause His Bábí Faith to die out.

Unfortunately for him, the Báb’s imprisonment in Máh-Kú was the most productive and fruitful of His entire ministry.

The Báb revealed the Seven Proofs, and began revealing three of the most important works of His life: the Persian Bayán, the Arabic Bayán and the Kitabu’l-‘Asmá’, the warden became a Bábí and helped the Báb’s followers when they needed it. He allowed the Báb visitors and the possibility to write and send messages and letters, including to His family.

While He was in Máh-Kú the Báb’s magnetic, holy personality and perfect character drew to Him the inhabitants of the surrounding cities and villages, and His name spread throughout Ádhirbáyján. In fact, the Báb became so popular in that remote corner of Persia where He had been sent to be forgotten that it became a real problem for the Persian government.

The authorities—and poor Ḥájí Mírzá Áqásí—had to figure out where to send the Báb where He could not be so attractive. They needed to find a place so different, so foreign to what He was used to that He could not wield His influence there and gain followers.

That is how it was decided to transfer the Báb from Máh-Kú to Chihríq. Chihríq was supposed to be a different experience than Máh-Kú for the Báb because it was everything He was not used to.

Chihríq was a majority Sunní, not Shí’ah area. The people there spoke mostly Turkish, not Persian. It seemed like an ideal place where there was no chance the Báb would penetrate through the hard Kurdish exterior of the people and the warden of the fortress.

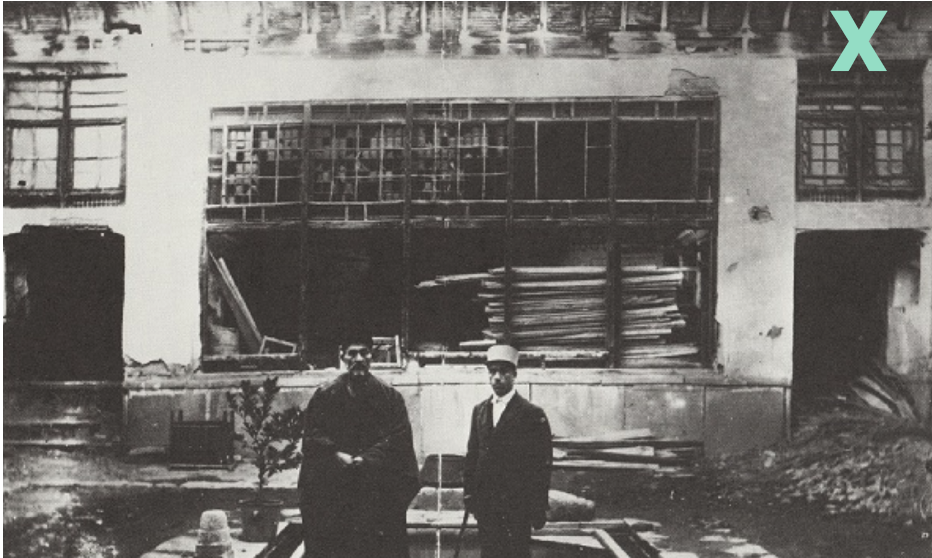

The Castle in Chihríq. In April 1848 the Báb was transferred from Máh-Kú to the even more remote Castle of Chihríq, by order of the Grand Vizier. The Báb remained in that Castle from 1848 to 1850. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

The castle of Chihríq was named by the Báb Jabal-i-Shadíd (the Grievous Mountain). Chihríq was close to Urúmíyyih and only 4 kilometers (2 miles) from the city of Salmas.

The inhabitants of that small region were Sunní Kurds of Naqshbandi, Yazidi, and Ahl-i Haqq tribes as well as a small minority of Nestorian Christians.

The warden of the fortress of Chihríq was named Yaḥyá Khán. He was a Kurdish chieftain of the Shikkak tribe and his sister was one of Muḥammad Sháh’s wives.

Yaḥyá Khán was a harsh and unpredictable man and, to satisfy Ḥájí Mírzá Áqásí, he treated the Báb harshly during His first few months of confinement, which were difficult and rigorous.

“Chihríq in Summer”: Digital painting of Chihríq, imagined in summer, for a story about the softening of harsh conditions in the Báb’s final imprisonment. © Violetta Zein

But Yaḥyá Khán could not keep the gates of his castle closed to the Bábís for very long. The Báb’s power and attraction soon captured his heart the way it had ‘Alí Khán’s, and soon, his entire being and heart were filled with love for the Báb.

One day, the Báb asked for some honey, but the product that was brought to Him was not of good quality, and He found the price expensive. The Báb explained that He had been a merchant by profession, and asked that better quality honey be bought for a lower price and brought to Him. The Báb counseled the men to follow His example, and to neither take advantage of anyone nor let themselves be taken advantage of.

This level of integrity, right down to the smallest things, was one of the Báb’s qualities. Not even the shrewdest or smartest of dishonest men could deceive Him, and He, in turn never treated harshly even the meanest or most helpless of men.

“The gathering”: Imagined scene at the bottom of the Castle of Chihríq created with the AI Midjourney. To see the original prompt and Midjourney export click here.

The Bab’s imprisonment in Ádhirbáyján caused the Bábí Faith to spread throughout the region in the cities and villages of Máh-Kú, Khúy, Maraghíh, Salmas, Urúmíyyih, Tabríz, and Saysán. The successful proclamation of the Bábí Faith during the Báb’s incarceration was due to a small but very active group of Bábís who had gone to meet the Báb, then disseminated His message effectively

There were soon so many Bábís in Chihríq, that it was impossible to find them accommodation, and they had to be housed in the town of Iskí-Shahr, where food and other necessities for the castle were purchased.

The Kurds who lived in Chihríq, like the inhabitants of Máh-Kú before them, soon became so fascinated by the Báb that they also gathered at the fortress every morning, before starting their work day, to prostrate themselves before the Báb.

So many people wanted to gather in the courtyard to see and hear the Báb that the majority of them had to remain in the street in order to listen to the verses revealed by the Báb, knelt to the ground, seeking to refresh their souls with Remembrance of Him.

In fact, the commotion caused by the Báb’s arrival in Chihríq far exceeded the infatuation of Máh-Kú, and Ḥájí Mírzá Áqásí’s plan to transfer the Báb to an even more remote location had completely backfired. The ardor the Báb aroused in people could not be stamped out.

Extremely distinguished Siyyids, eminent ‘ulamás, and even government officials flocked to the Bábí Faith and became ardent followers of the Báb. Yaḥyá Khán turned no one away.

The influence of the Báb was impossible to contain, it radiated like the sun, and attracted everyone.

A modern-day view of Khúy, 60 kilometers from Chihríq where Dayyán became a Bábí after a dream that prompted him to write to the Báb. Source: Wikimapia.

Khúy was also a town near Chihríq, and its inhabitants soon learned that a number of its more prominent citizens, Siyyids, clerics and officials, had become Bábís. Also living in Khúy was Mírzá Asadu'lláh Khúyí, the son of a personal friend of Ḥájí Mírzá Áqásí. He is known to us by his title Dayyán. Dayyán spoke Persian, but also Syriac, Hebrew, Turkish, and Arabic.

Mírzá Asadu'lláh had been a proud man, a high-ranking official in the government, a highly-learned man who wrote very eloquently, and had long resisted any attempts to convert him to the Bábí Faith. He was a very outspoken enemy of the Bábís until one night, he had a dream that convinced him to write to the Báb.

The moment he received the Báb’s answer, he gave the Báb his complete allegiance with great zeal and fervor and the Báb bestowed on Mírzá Asadu'lláh the title Dayyán ("One Who Rewards" or "Judge"). The Báb conferred on Dayyán, in His own words, the “hidden and preserved knowledge,” and extolled him as the “repository of the trust of the one true God.”

His father, thoroughly alarmed at his son’s intense conversion, wrote to Ḥájí Mírzá Áqásí in a panic. Things were not going well for the Prime Minister. All of Ḥájí Mírzá Áqásí’s plans to contain the Báb were failing, and it was spreading throughout Persian, unstoppable, and on another front, the health of Muḥammad Sháh was deteriorating quickly, as his gout was worsening. He did not have long to live.

A Persian dervish in the 1870s, photographed by Dimitri Yermakov. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

One day, an Indian dervish arrived from India. No one ever found out who he really was, and we still do not know. The Báb gave him the name Qahru'lláh (“the Wrath of God”).

All that the dervish would say about himself was that he was a Navváb in India, and that the Báb had appeared to him in a vision:

“He gazed at me and won my heart completely. I arose, and had started to follow Him, when He looked at me intently and said: 'Divest yourself of your gorgeous attire, depart from your native land, and hasten on foot to meet Me in Ádhirbáyján. In Chihríq you will attain your heart's desire.'”

The Báb received Qahru'lláh and gave him instructions to return to India as a dervish, alone and on foot, and Qahru'lláh obeyed, leaving alone, wearing the modest clothes of a dervish, staff in hand, all the way back to India. If anyone asked to accompany him, he would reply in a compelling way that stopped anyone from insisting:

“You can never endure the trials of this journey. Abandon the thought of coming with me. You would surely perish on your way, inasmuch as the Báb has commanded me to return alone to my native land.”

Although we do not know what happened to Qahru'lláh, this story is extraordinary for the distance he traversed in a dream. The pull of a Manifestation of God attracted a man from two countries away over thousands of kilometers on foot, and he reached not only his destination, but his heart’s desire.

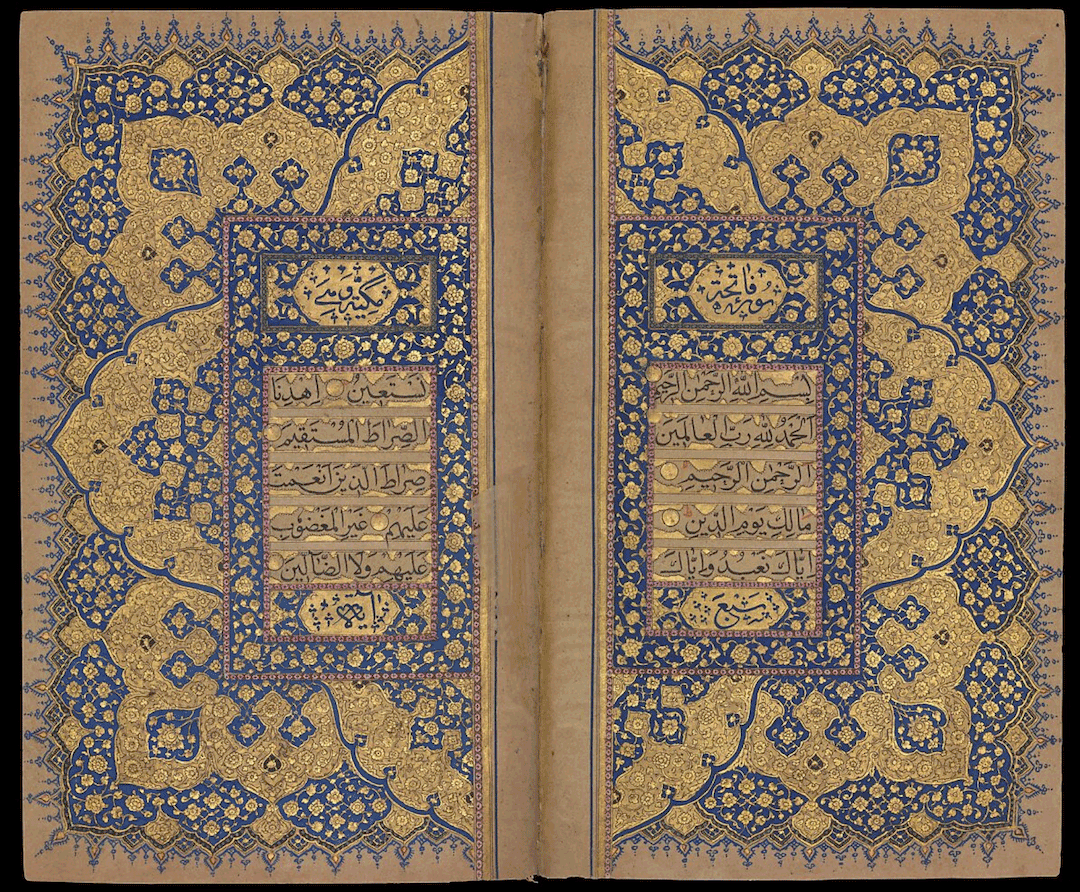

Late 18th / Early 19th century illuminated pages from a Qur’án, for a story about the Báb requesting treatises drawn from the Qur’án and Ḥadíths from 40 of His desciples. Source: The Met.

In the course of the year 1848, the Báb asked 40 of His disciples to compose a treatise establishing the truth and validity of His mission and relying on the Qur’án and the Ḥadíths.

His disciples obeyed immediately, and soon, the Báb received the 40 treatises and the Báb selected the one that Dayyán had written as the best of them all, showering His praise and unqualified admiration on his work.

It was on this occasion that He renamed Mírzá Asadu’lláh, and gave him the name Dayyán, and revealed in his honor the Lawḥ-i-Ḥurúfat (Tablet of the Letters), a Tablet by which He estimated, no amount of learning could produce:

“Had the Point of the Bayán (the Báb) no other testimony with which to establish His truth, this were sufficient—that He revealed a Tablet such as this, a Tablet such as no amount of learning could produce.”

Two years later, in the Lawḥ-i-Ḥurúfat (Tablet of the Letters), which forms the last part of the Book of the Five Modes, the Báb made statements that proved beyond any doubt that 19 years needed to elapse after His own Declaration before “Him Whom God shall make manifest” (Bahá'u'lláh) made His appearance.

No one but Bahá'u'lláh was able to discern those proofs in the Lawḥ-i-Ḥurúfat, it remained a complete mystery to even the most ardent of the Báb’s disciples.

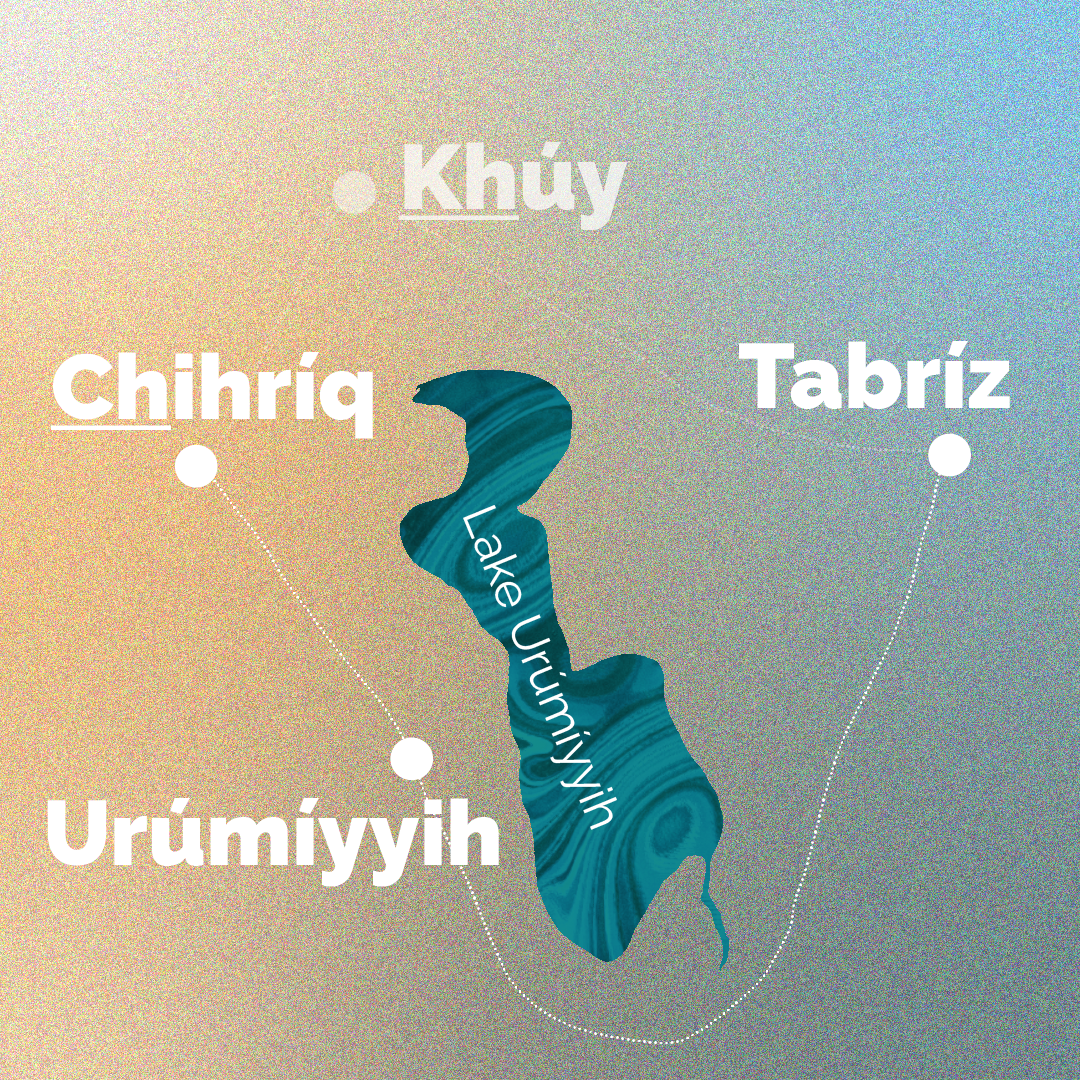

Map of the two possible routes to Tabríz from Chihríq: the first, most direct route, to the north of Lake Urúmíyyih, via the town of Khúy is in transparency as it was first planned but later abandoned because of the level of support for the Báb in Khúy. The second, southern route around Lake Urúmíyyih is the one that was taken, with a memorable stop in the town of Urúmíyyih itself. © Violetta Zein

The Báb had been in Chihríq for three months when Ḥájí Mírzá Áqásí, after receiving written complaint after complaint from the ‘ulamás of Ádhirbáyján regarding the enthusiasm of the people of Chihríq and the conversions of so many eminent personalities to the Bábí Faith, gave the order the Báb was to be sent to Tabríz.

Even before the summons arrived, the Báb had begun to make His own arrangements.

First, the Báb sent away the Bábís who had congregated around the castle of Chihríq. Then, the Báb asked Shaykh Ḥasan-i-Zunúzí to collect all the Writings He had revealed in Máh-Kú and Chihríq and entrust them for safekeeping to Siyyid Ibráhím-i-Khalíl, who lived in Tabríz.

The Persian government had originally wanted to transfer the Báb from Chihríq to Tabríz via the city of Khúy, but, given the enthusiasm for the Báb in Khúy, and a rescue attempt they got wind of, they decided to change the route and transfer Him via Urúmíyyih, 100 kilometers (80 miles) southwest of Tabríz, instead.

Ḥájí Mírzá Áqásí had chosen a brigadier by the name of Riḍá-Qulí Khán-i-Afshár to escort the Báb, and this man’s fate was the same as so many who had preceded him: he soon became wholly captivated by the Báb and would later become a devoted and faithful Bábí.

The Governor’s Court in Urúmíyyih; the light green ‘X’ on the top right above the window indicates the upper room (Persian: bálá-kháneh) occupied by the Bab during his stay. Source: Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, page 310.

As soon as the Báb reached Urúmíyyih, on his way to Tabríz, the Governor, Malik-Qásim Mírzá, received Him reverently, and took Him to the Governor’s Court, known as the Four Towers Building.

Malik-Qásim Mírzá was the 24th son of Fatḥ-‘Alí Sháh (1772–1834), and paternal uncle of Muḥammad Sháh and he was an extremely well educated man. He spoke French to perfection and was fluent in five other languages including Hindi. Malik-Qásim Mírzá was a lover of Western arts and education, but he was also a kind ruler, who took an interest in his people and often visited the sick.

It was thanks to Malik-Qásim Mírzá’s culture, open-mindedness, and fairness, that the Báb spent ten pleasant days in Urúmíyyih. Malik-Qásim Mírzá gave the Báb complete freedom while He was his guest.

For the next ten days, the Four Towers Building was thronged every day by people who wanted to meet the Báb or just to catch a glimpse of Him. The Báb was allowed to receive and return visits from local notables and Shí’ah clerics, but He also received visits from the Bábís of the town and the local Letter of the Living, Mullá Jalíl-i-Urúmí.

Self-portrait of Malek-Qasim Mirza holding a watch in his hands to measure the exposure time. Copyright: Chahryar Adle. Source: Encylopaedia Iranica Online edition (Accessed Friday 3 March 2023).

Malik-Qásim Mírzá could not help himself and decided to test the Báb. But this was not a theological test, it was the matter of an unruly horse.

On the Friday of His visit in Urúmíyyih, the Báb had decided to visit the public bath, and Malik-Qásim Mírzá thought he would trick the Báb by asking his attendants to give the Báb a particularly unruly horse to ride.

Those who knew the horse waited impatiently to see the spirited animal best the Báb, but when He approached the horse, the animal stood perfectly still, and the Báb quietly took the bridle in His hand, gently caressed the horse, then placed His foot in the stirrup. The Báb mounted the horse with no problem at all, and started riding it with perfect control.

Malik-Qásim Mírzá, ashamed of his trick, accompanied the Báb on foot, next to the now-calm horse, almost all the way to the public bath, until the Báb asked him to return to his house. All the way from the residence to the bath, attendants had to follow the Báb and stop the people from swarming Him.

When the Báb was finished with the public bath, he mounted the same horse again to return to the Governor’s home, but in the meantime, the news had spread through the town (one imagines that horse must have been extremely dangerous), and men, women, and children rushed in to take away every drop of the water the Báb had used.

Later, when the Báb was informed how the overwhelming majority of the people had spontaneously proclaimed their undivided allegiance to the Bábí Faith, He calmly quoted the Qur’án (29:2):

“Think men that when they say, ‘We believe,’ they shall be let alone and not be put to the proof?”

A beautiful modern-day photograph of nearby salt lake, Lake Urúmíyyih, for a story about art. Source: Wallpapers HD.

It was in Urúmíyyih that the only portrait of the Báb that we have today was painted, and this is the story of that portrait.

Áqá Bálá Bayg was a local artist from a nearby town and was Malik-Qásim Mírzá’s chief painter. When Áqá Bálá Bayg first met the Báb, he noticed the Báb had gathered His robes around Him, as if sitting for a portrait. When he noticed this again on his second visit, he understood, and when he arrived for his third visit, he brought his tools, and completed a couple of sketches of the Báb, which he later turned into a full-scale black and white portrait.

There are five known copies of the Báb’s portrait:

- The original black and white portrait was painted by Áqá Bálá Bayg in mid-end July 1848 in Urúmíyyih;

- This portrait was later copied as a watercolor painting at Bahá'u'lláh’s instruction in the early 1880s and delivered to Him by Hand of the Cause Ḥájí Akhúnd;

- Bahá'u'lláh requested another watercolor copy shortly after, but the fate of this artwork is unknown;

- A fourth copy of the painting was found in Áqá Bálá Bayg’s possessions after his death and Shoghi Effendi requested it be colored in 1936. This copy is still at the Bahá'í World Centre;

- There is also a fifth copy of an incomplete sketch that was found at the same time as the fourth copy of the ‘Báb’s portrait, and is believed to also be held at the Bahá'í World Centre.

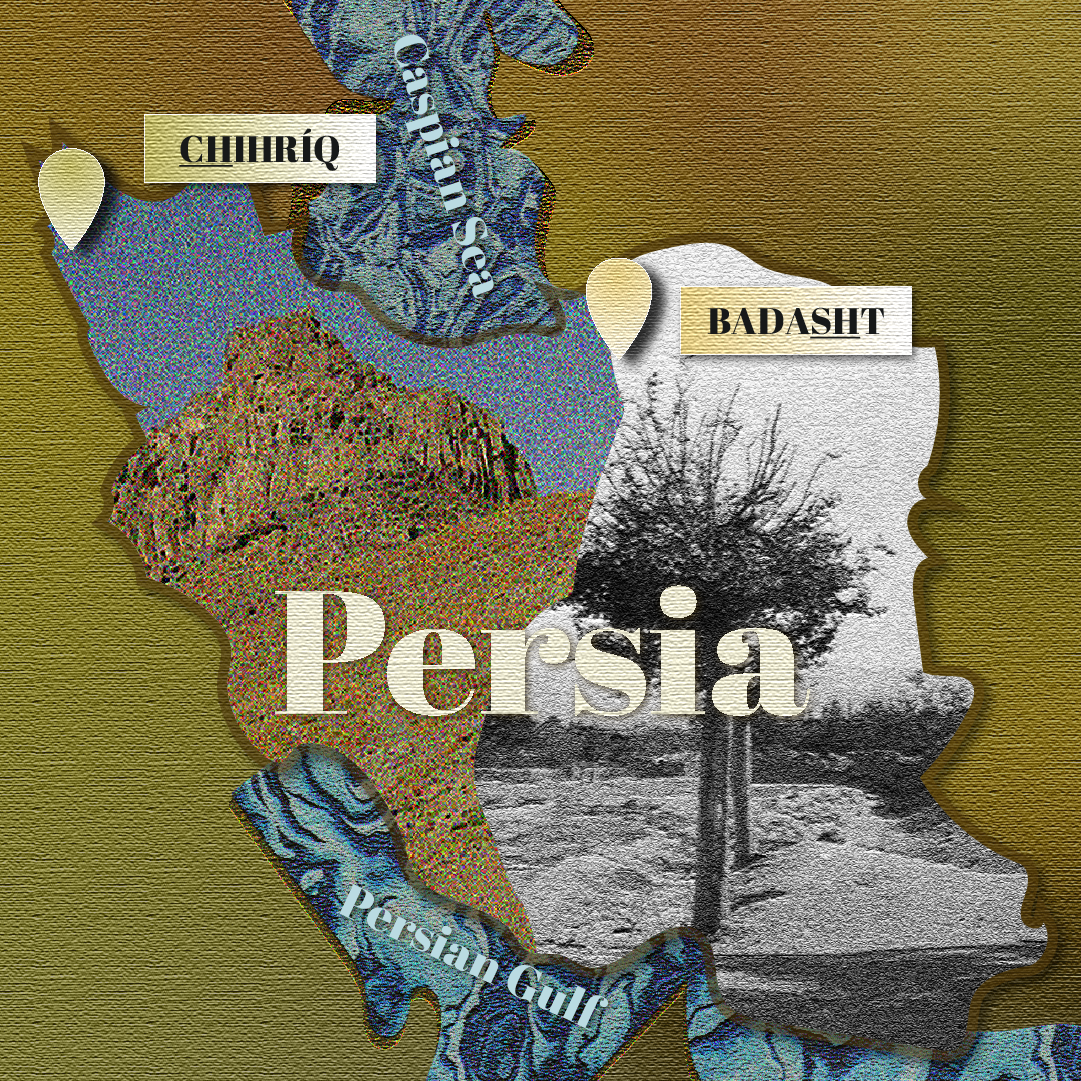

Spiritual energies at play: Map of Persia at the moment of the conference in Badasht, showing the location of the Báb in Chihríq. Image for the left half of the map of Persia: Chihríq fortress from Wikimedia Commons; Image for the right half of the map: the village of Badasht, © Bahá'í International Community, Bahá'í Media Bank. Map from The Blessed Beauty illustrated chronology: Part II: The Birth of the Bahá'í Faith: The Conference of Badasht © Violetta Zein.

Around the same time as the Báb was being examined in Tabríz, and made the public declaration of His claim as the Promised One of Islám, Bahá'u'lláh, Quddús and Ṭáhirih were proclaiming the Advent of the new Dispensation across the country in Khurasán at the conference of Badasht.

Bahá'u'lláh and Quddús had agreed the time had come, three years into the Báb’s ministry, to make the formal announcement, but in order for it to be effective, it had to be dramatic and unforgettable, and for that, they needed Ṭáhirih’s indomitable spirit.

Bahá'u'lláh organized the logistics of the conference and paid for the three-week event. Eighty-one Bábís, 80 men and Ṭáhirih, attended Badasht. Bahá'u'lláh rented three gardens, one for Himself, one for Quddús, and the third one for Ṭáhirih. Bahá'u'lláh bestowed new names on all the participants, but His guiding hand in the gathering was so subtle, no one knew who was revealing a new Tablet each day.

1930 photograph of the village of Badasht, where in 1848, Bahá’u’lláh hosted a gathering of the most eminent followers of the Báb. The meeting established for the growing number of believers the independent character of the Bábí religion. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

Bahá'u'lláh, Quddús, and Ṭáhirih had pre-arranged the roles they were to play to wake the Bábís from their slumber: Quddús was the conservative voice, Ṭáhirih the revolutionary, and Bahá'u'lláh the moderator, the conciliator.

Argument and counter argument arose during the conference until a final, irreconcilable and public break seemed to appear between Ṭáhirih and Quddús.

This was when Ṭáhirih appeared unveiled, and announced to her fellow Bábís:

“I am the Word which the Qá’im is to utter, the World which shall put to flight the chiefs and nobles of the earth!...This is the day of festivity and universal rejoicing, the day on which the fetters of the past are burst asunder. Let those who have shared in this great achievement arise and embrace each other.”

Badasht was a watershed event.

The fainthearted Bábís left, and those that remained were committed and steadfast. The blind, orthodox, rigid fetters of the past had been blown away, with the woman’s veil, the last most visible symbol of Islám, and the Bábí dispensation had been ushered in. The trumpet had been blown.

Before entering Tabriz, the Báb summoned Mullá ‘Alí Turshízí, known as ‘Aẓím, His foremost disciple native to Ádhirbáyján. ‘Aẓím was Vaḥíd’s friend, who had counseled him on how to act during his three interviews with the Báb in Shíráz, in the Spring of 1846.

He informed ‘Aẓím that He intended to formally and publicly assert His claim to being the Qá’im in front of a panel of clerics and the crown Prince, Naṣiri'd-Dín Sháh.

‘Aẓím was one of the Báb’s closest companions and he was shocked. He had until now thought the Báb was merely the Gate to the Qá’im, not the Qá’im Himself, and left the Báb’s presence.

The next day, ‘Aẓím returned to the Báb and told Him that he had spent the entire night in a deep state of agitation and ardent prayer and supplication with God and that he had come to recognize the Báb’s claim to being the Promised One.

The Báb then revealed the Risáliy-i-Qá’imíyyat (Treatise on Qaimhood) (also known as the Tawqíʻ-i-Qá’imíyyat—Epistle on Qaimhood—in honor of ‘Aẓím, and instructed him to disseminate it and share its contents openly with anyone he felt receptive to it.

ʻ‘Aẓím prepared several copies of the Treatise which he sent to the most eminent Bábís of the time, as well as to the Bábí communities of Ṭihrán, Káshán, Iṣfahán, Yazd and Búshihr.

The Risáliy-i-Qá’imíyyat would have a profound impact on how Bábís understood the truth of the Báb’s message and His station.

The Risáliy-i-Qá’imíyyat is an important Treatise because it represents the Báb’s most open expression of doctrinal independence and His final, clearest, and most emphatic break from Islám. Nowhere else does the Báb more clearly proclaim that He is the Qá’im, and in this Treatise, He plainly declares His mission, the fulfilment of the prophecies for the return of the Mihdí—another title for the Qá’im—and expounds on the signs of the Qá’im and His advent.

In the Risáliy-i-Qá’imíyyat, the Báb calls on ‘Aẓím to be the messenger between the people and the Qá’im, “Who by God’s benevolence has now manifested Himself,” and He declares:

“I am that divine fire which God kindles on the Day of Qiyáma. By which all will be resurrected and revived, then either they shun away from it or enter the Paradise through it…For fifty thousand years we awaited the Day of Qiyáma until All Beings would purify and nothing remain but the face of your Lord, the Lord of glory and might.”

In this Treatise, the Báb portrays His Revelation as the fulfilment of all past prophecies, the inauguration of a period of religious truth, and the abrogation of the religious laws of Islám (Sharí‘a law):

“The Báb emphasizes that, in abrogating the religious law that came before His own, he did not utter even a single word that ran counter to “the Primal Book” [the Qur’án], taking God as His witness that whatever He has annulled or established has been done at the behest of God.”

An undated photograph of old Tabríz. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

After Urúmíyyih, the Báb left for Tabríz which He reached at the end of July 1848, where He was, once again, welcomed by the population with joyful, wild excitement. The Báb’s arrival caused such a wave of enthusiasm that He was housed in a palace outside the gates of the city, but even this precaution did nothing to quell the excitement caused by His arrival.

At the time the Báb arrived in Tabríz, the city was home to the largest population of ‘ulamás in Persia after Iṣfahán, and its clerics were alarmed by the rapid spread of the Bábí Faith throughout the cities and villages of their region.

When Ḥájí Mírzá Áqásí staged the Báb’s trial in Tabríz, with its large population of clerics, he was not only calling instructing them to find a way to permanently stop the spread of the Bábí Faith, but he had two ulterior motives.

On the one hand, Ḥájí Mírzá Áqásí was sending a message to the Bábís, warning them of the fatal consequences of any militant action on their part.

At the same time, he was using the trial to remind the Tabríz ‘ulamás of their ultimate reliance on his good will.

It was a double political stratagem, but like all of his ploys when it came to the Báb, it would not go the way he had planned. In fact, the beginning of the Báb’s examination was delayed by a week because the clerics in Tabríz could not decide how they should conduct His trial.

Naṣiri'd-Dín Sháh as a child, with Mírzá Abu’l-Qásim, the Qá’im-Maqám on his right and Ḥájí Mírzá Áqásí, the Prime Minister, on his left. On the extreme left (marked with an X) is Manúchihr Khán, the Governor of Iṣfahán. Except for Manúchihr Khán, the types of people represented in this 19th century painting are the types of people who would have been present at the Báb’s examination in Tabríz. Source: Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, page 314.

In Tabríz, the Báb was brought before the 17-year old Governor of Ádhirbáyján, Naṣiri'd-Dín Mírzá (who would become Naṣiri'd-Dín Sháh in two months), the son of the dying Muḥammad Sháh.

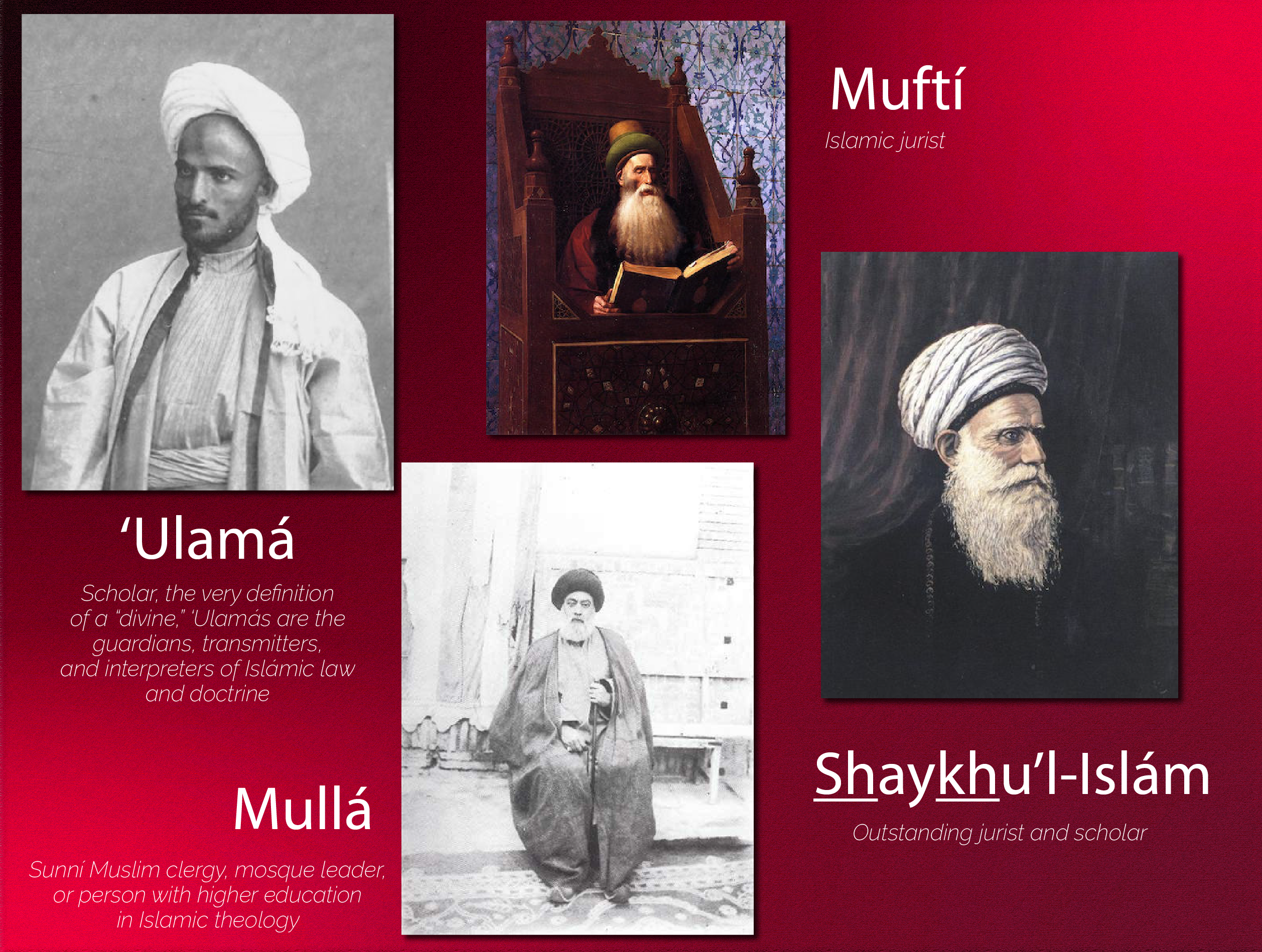

A panel of the prominent clerics of Tabríz had gathered to examine the Báb, and expose His so-called “heresy.” Among which the leaders were Ḥájí Mírzá Maḥmúd, the chief tutor of Naṣiri'd-Dín Mírzá, the one-eyed Mullá Muḥammad-i-Mámaqání, a well-known Shaykhí, Ḥájí Murtiḍá-Qulíy-i-Marandí, Ḥájí Mírzá `Alí-Aṣghar, the Shaykhu'l-Islám (a high clerical position), and Mírzá Aḥmad, the leader of Friday prayers.

The entire tribunal was a farce.

The leading clerics of Tabríz, the shining lights of Islám in that city, had assembled to learn from the Báb, to them a young Siyyid who claimed to bring a message from God. They only had to listen Him, to learn the nature of His Claim, and to be just.

They would fail on all counts, and ridicule themselves in the process, while the Báb did what He had come to do and remained composed and dignified throughout.

Musicians and dancers at the court of Naṣiri'd-Dín Sháh, as an illustration for court proceedings that were as much of a farce as the acrobatics of the dancers in the image above. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Instead of focusing on their stated aim, the clerics asked the Báb ridiculous and pointless questions such as these two from Ḥájí Mírzá Maḥmúd, Naṣiri'd-Dín Mírzá’s tutor. The first question, about indigestion:

“As the Prophet or some other wise man hath said "Knowledge is twofold—knowledge of bodies, and knowledge of religions"; I ask, then, in Medicine, what occurs in the stomach when a person suffers from indigestion? Why are some cases amenable to treatment? And why do some go on to permanent dyspepsia or syncope [swooning], or terminate in hypochondriasis?”

And a second question, about conjugating the verb “to say” Arabic:

“The science of "Applications" is elucidated from the Book and the Code, and the understanding of the Book and the Code [the Qur'án and the Traditions] depends on many sciences, such as Grammar, Rhetoric, and Logic. Do you who are the Báb conjugate Qála (Qála, the third person singular of “to say”)?'”

The examination of the Báb went on for hours.

The sheer number of questions posed to the Báb, His answers, the counter-questions, His calm responses, followed by His Revelation of verses in the style of the Qur’án, the angry comments of the members of the tribunal, their mockery, snide comments, requests for miracles, further questions, are above and beyond the scope of this chronology.

To read a complete, detailed account of all the above-mentioned events, please refer to Fereydun Vahman (Editor),The Bab and the Babi Community of Iran (2020), Chapter 1: The Báb: A Sun in a Night Not Followed by Dawn by Fereydun Vahman.

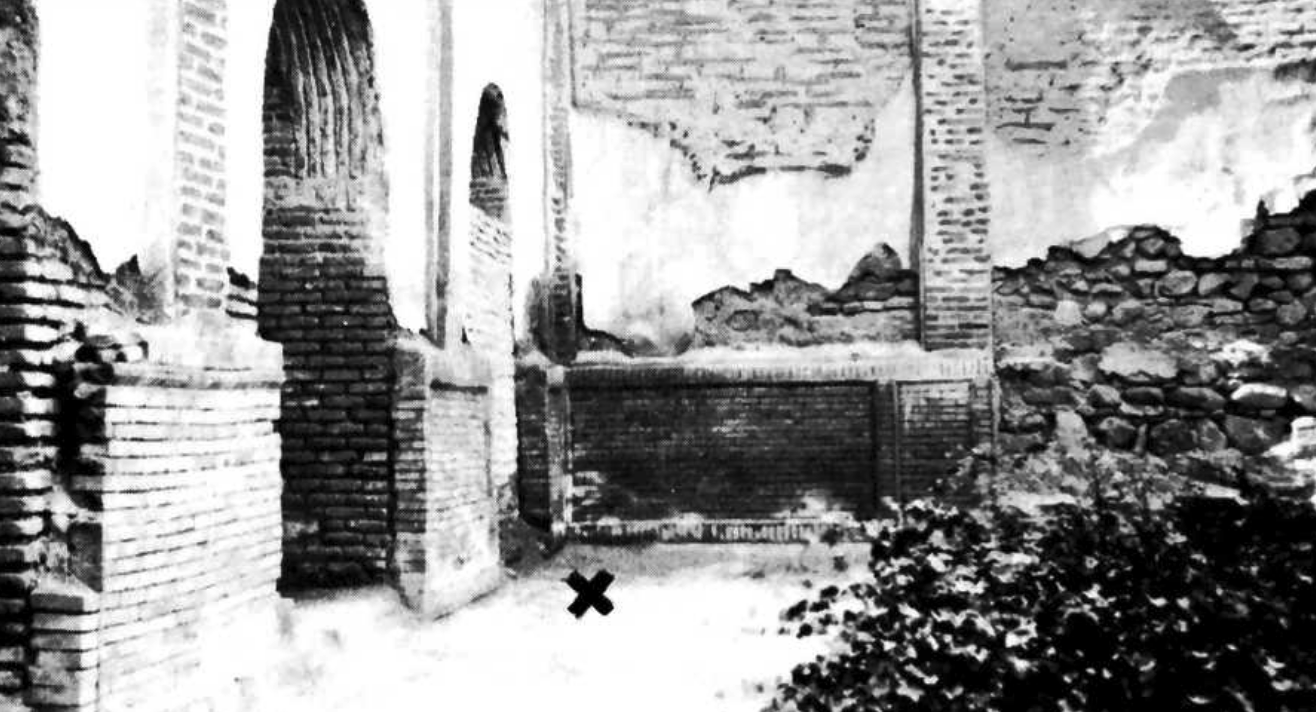

Ṭabríz. The Namáz-khánih (prayer-house) of the Shaykhu'l-Islám, the head of the Muslim court in Tabríz where the Báb was interrogated. The courtyard in front is where the Báb would soon be tortured. Source: Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, page 318.

The climax of the Báb’s examination in Tabríz was when He stated His claim clearly for all the assembled divines to hear:

“I am that person for whose appearance ye have waited a thousand years.”

Ḥájí Mírzá Maḥmúd replied:

“That is to say you are the Mahdí, the Lord of Religion?”

“Yes.”

“The same in person, or generically?”

“In person.”

“What is your name, and what are the names of your father and mother? Where is your birthplace? And how old are you?”

The Báb replied to all of the questions. And Ḥájí Mírzá Maḥmúd arrogantly replied:

“The name of the Lord of Religion is Muḥammad; his father was named Ḥasan and his mother Narjis; his birthplace was Surra-man-Ra'a; and his age is more than a thousand years. There is the most complete variance. And besides I did not send you.”

The Báb retorted:

“Do you claim to be God?”

It was in the course of this interrogation that the Báb reached the climax of His ministry, by presenting a dramatic, unqualified, formal declaration of His prophetic mission:

“I am, I am, I am the Promised One! I am the One Whose name you have for a thousand years invoked, at Whose mention you have risen, Whose advent you have longed to witness, and the hour of Whose Revelation you have prayed God to hasten. Verily, I say, it is incumbent upon the peoples of both the East and the West to obey My word, and to pledge allegiance to My person.”

Eminent Persian Mujtahids, like the ones examining and torturing the Báb in this section. Source: Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, page 318.

The rudest and most insolent cleric at the Báb’s mock trial was Mullá Muḥammad-i-Mámaqání. The Báb was sitting between him and Naṣiri'd-Dín Mírzá, and when the Báb affirmed He was the Qá’im, Mullá Muḥammad lashed out in anger and insulted Him:

“You wretched and immature lad of Shíráz! You have already convulsed and subverted ‘Iráq; do you now wish to arouse a like turmoil in Ádhirbáyján?”

The Báb's answer to his outburst was a calm statement of fact:

“Your Honour, I have not come hither of My own accord. I have been summoned to this place.”

This drove Mullá Muḥammad crazy and he shouted back at the Báb even more disdainfully:

“Hold your peace, you perverse and contemptible follower of Satan!”

The Báb calmly replied:

“Your Honour, I maintain what I have already declared.”

Collage of a variety of different Muslim clerics: a ‘ulamá, a mullá, a muftí, and a Shaykhu'l-Islám. © Violetta Zein

Ḥájí Mírzá Maḥmúd then challenged the Báb:

“The claim which you have advanced is a stupendous one; it must needs be supported by the most incontrovertible evidence.”

The Báb replied:

“His own word, is the most convincing evidence of the truth of the Mission of the Prophet of God,” and quoted a verse from the Qur’án to this effect: "Is it not enough for them that We have sent down to Thee the Book?"

Ḥájí Mírzá Maḥmúd continued with another ridiculous request:

“Describe orally, if you speak the truth, the proceedings of this gathering in language that will resemble the phraseology of the verses of the Qur'án so that the Valí-‘Ahd [Crown Prince] and the assembled divines may bear witness to the truth of your claim.”

The Báb had only just started answering when Mullá Muḥammad interrupted Him disrespectfully:

“This self-appointed Qá'im of ours has at the very start of his address betrayed his ignorance of the most rudimentary rules of grammar!”

The Báb, unperturbed, replied:

“The Qur'án itself does in no wise accord with the rules and conventions current amongst men. The Word of God can never be subject to the limitations of His creatures. Nay, the rules and canons which men have adopted have been deduced from the text of the Word of God and are based upon it. These men have, in the very texts of that holy Book, discovered no less than three hundred instances of grammatical error, such as the one you now criticise. Inasmuch as it was the Word of God, they had no other alternative except to resign themselves to His will.”

But Mullá Muḥammad turned a deaf ear to the Báb, and another divine interrupted with an absurd question about the tense of a verb.

The Báb had indulged their childish nonsensical questions for long enough. He replied with a verse from the Qur’án:

“Far be the glory of thy Lord, the Lord of all greatness, from what they impute to Him, and peace be upon His Apostles!”

Then, He rose up from His seat and walked out of the gathering.

At the end of the ridiculous trial, the clerics insisted that the Báb be executed on a charge akin to heresy. The young Naṣiri'd-Dín Mírzá was faced with a difficult decision. If he agreed to execute the Báb, it was likely the entire country would erupt into turmoil, but if he went against the ‘ulamás, he could lose his chance at sitting on the throne.

To solve the Prince’s dilemma, his advisors which included Ḥájí Mírzá Maḥmúd, the Niẓámu'l-‘Ulamá, suggested he send his personal physicians to assess the Báb’s mental faculties.

The photo of Dr Cormick obtained by Vincent Flannery. Source: Connections: Brendan McNamarra, Dr. Cormick: The man who met the Báb, some new facts about his life, (accessed 3 march 2023).

The Báb was subjected to a medical examination by two Persian doctors and an Irish physician, Dr. William Cormick, the only Westerner ever to meet the Báb in person. Dr. Cormick was born in Tabríz. His mother was Armenian, and his father was Irish, a doctor for the Qajár court. Dr. Cormick was born fluent in Farsi and English.

After completing his medical studies in England in 1844, he returned to Persia and was appointed as physician to the British Mission in Ṭihrán, which is how he found himself accompanying the young Naṣiri'd-Dín Sháh in Tabríz.

The point of that examination was to ascertain whether the Báb was sane or a madman, in order to decide whether to execute Him.

During the examination, the Báb chanted verses in a melodious voice.

Dr. Cormick described the Báb as follows:

“He was a very mild and delicate-looking man, rather small in stature and very fair for a Persian, with a melodious soft voice, which struck me much. Being a Sayyid, he was dressed in the habits of that sect, as were also his two companions. In fact his whole look and deportment went far to dispose one in his favour. Of his doctrine I heard nothing from his own lips, although the idea was that there existed in his religion a certain approach to Christianity. He was seen by some Armenian carpenters, who were sent to make some repairs in his prison, reading the Bible, and he took no pains to conceal it, but on the contrary told them of it. Most assuredly the Musulmán fanaticism does not exist in his religion, as applied to Christians, nor is there that restraint of females that now exists.”

Although He did not answer any of the physicians’ questions regarding His sanity, the Báb did speak directly to Dr. Cormick, stating that, as he was not a Muslim, he might be interested in knowing something of the Bábí Faith and perhaps might be inclined to become a Bábí himself.

As He was speaking to Dr. Cormick, the Báb looked at him intently, stating He had no doubt all Europeans would one day flock to His Faith.

Dr. Cormick and his fellow Persian physicians wrote a report to Muḥammad Sháh claiming insanity in order to spare the Báb’s life.

To satisfy the clerics who were intent on the Báb’s execution, the government spread rumors that the Báb had recanted His claims during His examination, and produced a written recantation in someone else’s handwriting with no signature as proof.

Naṣiri'd-Dín Mírzá wrote an extensive report to his father, Muḥammad Sháh, lying that the Báb had apologized, recanted, repented, begged for forgiveness for His errors, sworn to not repeat His mistakes, and was “awaiting the decision of his Most Sacred Royal and Imperial Majesty, may the souls of the worlds be his sacrifice!”

This is the part of the courtyard where the Báb was tortured. The Shaykhu'l-Islám personally carried out the enforcement of the sentence of torture by bastinado. Source: Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, page 318.

Shortly after the Báb’s ridiculous trial, Mírzá ‘Alí-Aṣghar, the Shaykhu'l-Islám of Tabríz who had not been present during the Báb’s examination, issued a fatwá condemning the Báb to death, and signed by his nephew, a mujtahid called Shaykh Abu’l-Qasím. In the fatwá, Mírzá ‘Alí-Aṣghar accused the Báb of heresy.

Mírzá ‘Alí-Aṣghar was aware the Persian government had no intention on executing the Báb at that time, so he insisted that the Báb be subjected to corporal punishment, hoping that torture would induce Him to truly recant His claims.

The decision to torture the Báb was neither a unanimous nor a popular one. Even the farráshes—persons in charge of administering torture—refused to whip the Báb out of sympathy for Him, and so Mírzá ‘Alí-Aṣghar was forced to administer the torture himself.

The Báb was taken to the the home of Muḥammad-Káẓim Khán, the head executioner or punisher, and Mírzá ‘Alí-Aṣghar personally administered the . bastinado (foot whipping) to the Báb.

The punishment was to be 20 lashes to the soles of the Báb’s feet, but several of the blows landed on His face, and the Báb was so severely wounded that he had to receive medical attention for the swelling on His face.

Instead of the Persian doctors, the Báb requested the presence of the English physician. Dr. Cormick stated that he treated the Báb for several days, for which the Báb was thankful. The men were always under heavy watch, which made any further conversation between them impossible.

Views of the Mosque of Gawhar-Shád In Mashhád, showing the pulpit where Mullá Ḥusayn preached on a visit Mashhád three years prior. This is the city where Mullá Ḥusayn is when he receives the Báb’s green turban and the Black Standard. Source: Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, page 124.

Mullá Ḥusayn had left Chihríq and followed the Báb’s instructions all the way to Mázindarán. He was now in Mashhád, in the province of Khurásán, when he received a package from the Báb which contained His green turban, and a new name for Mullá Ḥusayn: Siyyid ‘Alí, along with a message from the Báb:

“Adorn your head with My green turban, the emblem of My lineage, and, with the Black Standard unfurled before you, hasten to the Jazíriy-i-Khadrá (Verdant Isle) and lend your assistance to My beloved Quddús.”

The Black Standard was a very important symbol in Islám, signalizing the advent of the Promised One. According to the tradition, the Black Standard was the one the Prophet Muḥammad had spoken of in the following terms:

“Should your eyes behold the Black Standards proceeding from Khurásán, hasten ye towards them, even though ye should have to crawl over the snow, inasmuch as they proclaim the advent of the promised Mihdí, the Vicegerent of God.”

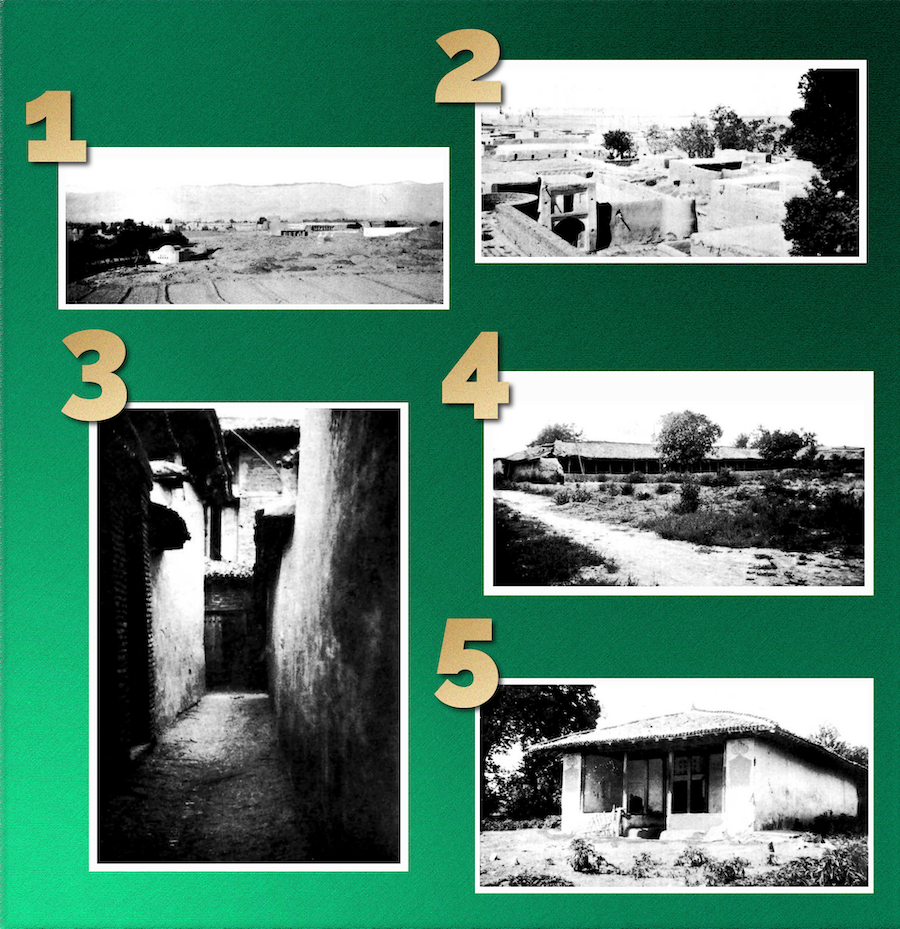

A small photo essay of the beginning of the Mázindarán Upheaval in five photographs: Photo 1: The village of Níshápúr where the father of Badí’ enlisted under the Black Standard; Photo 2: The village of Míyamáy where 30 inhabitants joined Mullá Ḥusayn; Photo 3: The house of the Sa‘ídu’l-‘Ulamá’ in Bárfurúsh, Mázindarán, a cruel and unforgiving man who rose up against Mullá Ḥusayn; Photo 4: Views of the caravanserai of Sabzih-Maydán in Mázindarán where Mullá Ḥusayn waited for his companions after being chased out of Bárfurúsh; Photo 5: The Shrine of Shaykh Ṭabarsí where the rest of the Mázindarán upheaval took place and where it ended. Design © Violetta Zein. All photos from Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, Chapter XIX: The Mázindarán upheaval.

As soon as he received the message, Mullá Ḥusayn followed all the Báb’s instructions to the letter. Some 6 kilometers (4 miles) outside of Mashhád, he placed the Báb’s green turban on his head, hoisted the Black Standard, assembled his companions, mounted his horse, and gave the signal for their march towards Quddús.

Mullá Ḥusayn and his companions raised the call of the Báb in every single town, village, or hamlet they passed, proclaiming the advent of the new day and inviting the people to join them, and selecting among the new converts those who would walk with them under the Black Standard.

The Mázindarán upheaval had just begun.

REFERENCES FOR PART X

April 1848: Why the Báb was transferred to Chihríq

Fereydun Vahman (Editor),The Bab and the Babi Community of Iran (2020), Chapter 1: The Báb: A Sun in a Night Not Followed by Dawn by Fereydun Vahman.

April – July 1848: Difficult circumstances in Chihríq

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, pages 135-136.

Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, page 303.

Fereydun Vahman (Editor),The Bab and the Babi Community of Iran (2020), Chapter 1: The Báb: A Sun in a Night Not Followed by Dawn by Fereydun Vahman.

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, pages 135-136.

Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, page 303.

Fereydun Vahman (Editor),The Bab and the Babi Community of Iran (2020), Chapter 1: The Báb: A Sun in a Night Not Followed by Dawn by Fereydun Vahman.

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, pages 135-136.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Fereydun Vahman (Editor),The Bab and the Babi Community of Iran (2020), Chapter 1: The Báb: A Sun in a Night Not Followed by Dawn by Fereydun Vahman.

Khúy: The story of Dayyán’s conversion

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, pages 136-137.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Fereydun Vahman (Editor),The Bab and the Babi Community of Iran (2020), Chapter 1: The Báb: A Sun in a Night Not Followed by Dawn by Fereydun Vahman.

Qahru’lláh: The Indian dervish

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, page 137.

Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, page 306.

The forty treatises of the Disciples of the Báb

Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, page 304.

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, pages 137-138.

In the home of Malik-Qásim Mírzá

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, pages 137-138.

Bijan Masumian and Adib Masumian, The Bab in the World of Images, Bahá’í Studies Review, vol. 19, June 2013, 171–90.

Fereydun Vahman (Editor),The Bab and the Babi Community of Iran (2020), Chapter 1: The Báb: A Sun in a Night Not Followed by Dawn by Fereydun Vahman.

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, page 138.

Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, pages 309-311.

Mid – end July 1848: Urúmíyyih: The Báb’s portrait

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, page 138.

Bijan Masumian and Adib Masumian, The Bab in the World of Images, Bahá’í Studies Review, vol. 19, June 2013, 171–90.

The organization of the conference

Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, Chapter XVI: The Conference of Badasht.

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, pages 167 – 171.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, Chapter XVI: The Conference of Badasht.

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, pages 167 – 171.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá in Memorials of the Faithful.

REVELATION: July 1848 before entering Tabríz: The Risáliy-i-Qá’imíyyat (Treatise on Qaimhood)

Fereydun Vahman (Editor),The Bab and the Babi Community of Iran (2020), Chapter 1: The Báb: A Sun in a Night Not Followed by Dawn by Fereydun Vahman.

Abbas Amanat, Resurrection and Renewal: The Making of the Bábí Movement in Iran (1844-1850) pages 375-376.

End of July 1848: The Báb arrives in Tabríz

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, pages 138-140.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, Chapter XVIII: The Examination of the Báb at Tabríz.

Fereydun Vahman (Editor),The Bab and the Babi Community of Iran (2020), Chapter 1: The Báb: A Sun in a Night Not Followed by Dawn by Fereydun Vahman.

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, pages 140-141.

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, page 141.

Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, Chapter XVIII: The Examination of the Báb at Tabríz.

Fereydun Vahman (Editor),The Bab and the Babi Community of Iran (2020), Chapter 1: The Báb: A Sun in a Night Not Followed by Dawn by Fereydun Vahman.

Climax of the examination: “I am that person for whose appearance ye have waited a thousand years”

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, pages 141-142.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, Chapter XVIII: The Examination of the Báb at Tabríz.

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, page 143.

Ḥájí Mírzá Maḥmúd’s challenge to the Báb

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, pages 143-145.

Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, Chapter XVIII: The Examination of the Báb at Tabríz.

Fereydun Vahman (Editor),The Bab and the Babi Community of Iran (2020), Chapter 1: The Báb: A Sun in a Night Not Followed by Dawn by Fereydun Vahman.

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, pages 138-140.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, Chapter XVIII: The Examination of the Báb at Tabríz.

Brendan McNamarra, Dr. Cormick: The man who met the Báb, some new facts about his life, (accessed 3 march 2023).

Fereydun Vahman (Editor),The Bab and the Babi Community of Iran (2020), Chapter 1: The Báb: A Sun in a Night Not Followed by Dawn by Fereydun Vahman.

H.M. Balyuzi, The Báb: The Herald of the Day of Days, page 145-147.

Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, Chapter XVIII: The Examination of the Báb at Tabríz.

21 July 1848: Mullá Ḥusayn receives the Báb’s turban

Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, Chapter IX: The Mázindarán Upheaval.

Immediately after: Mullá Ḥusayn rides to Mázindarán

Nabil, The Dawn-Breakers, Chapter IX: The Mázindarán Upheaval.

April 1848: Why the Báb was transferred to Chihríq

April 1848: Why the Báb was transferred to Chihríq