Written and illustrated by Violetta Zein

This part covers the life of Shoghi Effendi from the age of 30 in 1927 to the age of 34 in 1931.

Avárih returned to Persia, he worked as a teacher in high school for the rest of his life.

He changed tactics and began writing letters to the members of 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s family saying there had been a misunderstanding, and if Shoghi Effendi would only arrange an annual income for him, he would stop working against the Guardian and actively opposing the Covenant of Bahá'u'lláh.

Once the Guardian formally expelled him from the Faith, on 17 October 1927, and branded him a Covenant-breaker, his life was shattered.

His wife left him and refused to associate with him. She remained a devoted and much-praised Bahá'í because of this immensely courageous act.

He was separated from his only child.

He was denied entry into his own home.

He was shunned by the entire Persian Bahá'í community.

He was abandoned by his lifelong friends.

He never gained any income from the book he had written on the Faith and published in Egypt.

Eventually, Avárih became a Muslim, and continued to attack the Faith openly, writing a three-volume attack on the Faith, and the Guardian officially declared him a Covenant-breaker.

Avárih wrote several letters of repentance to the Guardian, in which there was absolutely no indication of repentance.

When the Guardian did not respond to his hypocritical letters, he unleashed his satanic nature and wrote the vilest, most abusive letters to Shoghi Effendi, using vile, offensive languages, and vowing revenge, saying he planned to destroy the Faith of Bahá'u'lláh altogether.

In the revolting history of Covenant-breakers, there would never be anyone as vile as Avárih.

Out of rage, Avárih became a Muslim and allied himself with the most fanatical elements of the Shí’ah clergy, the most orthodox Christian missionaries in Ṭihrán, and every person he could find in the Persian capital that was opposed to the Faith. With those friends in his pocket, Avárih used his fiendish subtlety to appeal to government officials for financial assistance.

He continued to attack the Faith openly, and wrote a three-volume attack on the Faith. He denounced the teachings of the Faith, discarding them as ineffective, he rejected the Will and Testament of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, he attacked the Blessed Persons, Missions and motives of Bahá'u'lláh and the Báb.

But he did not stop there.

He revived the malicious lies of the 19th century, claiming that Bahá'ís were the sworn enemy of Persia, the wreckers of the faith of Islam.

Avárih’s full-time occupation was to strike terror in the heart of the Bahá'í community, to sow seeds of doubt in the minds of any Muslim Persian who was even slightly favorable to the Bahá'ís, to poison the minds of any Persian who was indifferent to the Bahá'í community, and to reinforce the capacity for oppression and persecution of the Bahá'ís for all those in positions of power.

He labored for years in vain.

He was a failure at everything, even Covenant-breaking.

Thankfully, the end of the nauseating story of Avárih ends with his death in 1953

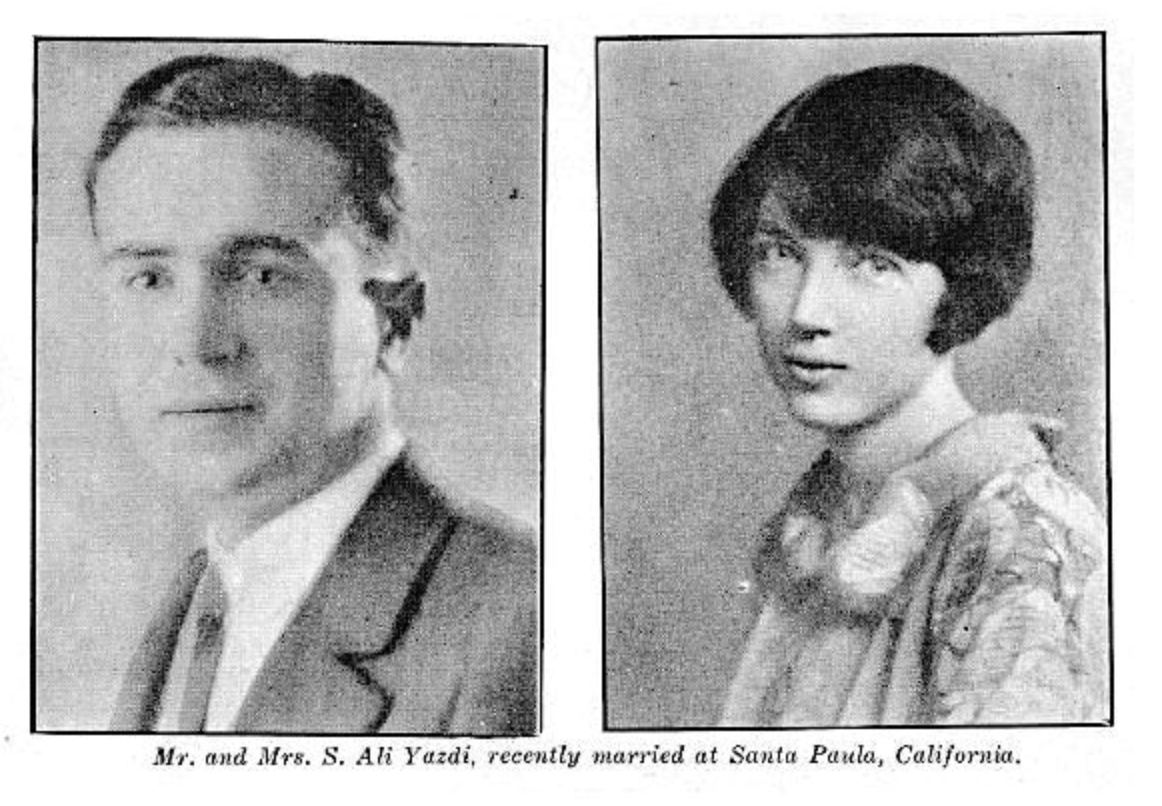

‘Alí Yazdí and Marion Carpenter Yazdí shortly after their marriage, a few years before their pilgrimage. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Marion Carpenter was born in Michigan in 1912, and was the first Bahá'í to attend the University of California at Berkley, and the first Bahá'í to attend Stanford University. As a young girl during World War I, she had begged 'Abdu'l-Bahá for permission to come to the Holy Land on pilgrimage, but communications were cut off and she never received a response.

When she started her studies at UC Berkley in the fall of 1920, she wrote to 'Abdu'l-Bahá again, requesting permission to come on pilgrimage, and 'Abdu'l-Bahá sent her a loving Tablet in answer to her letter in which He answered all her questions and wrote:

I hope that you…may make the visit, but at present it is not possible.

In August 1921, a handsome young Persian Bahá'í arrived at UC Berkley. He was remarkable from every point of view: he was profoundly deepened in the Teachings, he was utterly devoted to 'Abdu'l-Bahá, he was exemplary in his studies, he had a wonderful character, and he was all-around a fascinating person.

His name was ‘Alí Yazdí.

Marion could not get enough of ‘Alí’s stories about 'Abdu'l-Bahá, whom he had met countless times between 1910 and 1919 both in Ramleh, Egypt, and in Haifa.

Three months after Marion and ‘Alí Yazdí met, 'Abdu'l-Bahá passed away on 28 November 1921, so Marion never had the bounty of meeting Him in person. But she had ‘Alí Yazdí now, and she would live and breathe his stories about the Master. ‘Alí and Marion married in 1926, and two years later in 1928, Marion finally was able to go on pilgrimage, and ‘Alí was finally able to see Shoghi Effendi again after a separation of 8 years, since they had last seen each other in Oxford in 1920.

The last time they had met, Shoghi Effendi was a 23-year old student at Oxford and ‘Alí Yazdí was 21 years old, on his way to UC Berkley. Now, 8 years later, Shoghi Effendi had been the Guardian of the Cause for 7 years already and ‘Alí Yazdí had become a civil engineer.

When he was leaving, Shoghi Effendi encouraged ‘Alí to write to him and their friendship lasted to the end of the Guardian’s life. ‘Alí Yazdí did not want to burden the Guardian, he was all too aware—having spent so much time with 'Abdu'l-Bahá in his youth—the heavy responsibilities which the Head of the Bahá'í Faith had to bear. But ‘Alí did write to the Guardian on special occasions, when he had particularly good news, and the Guardian—as he had when he was a young man—always responded very warmly to his old friend’s letters.

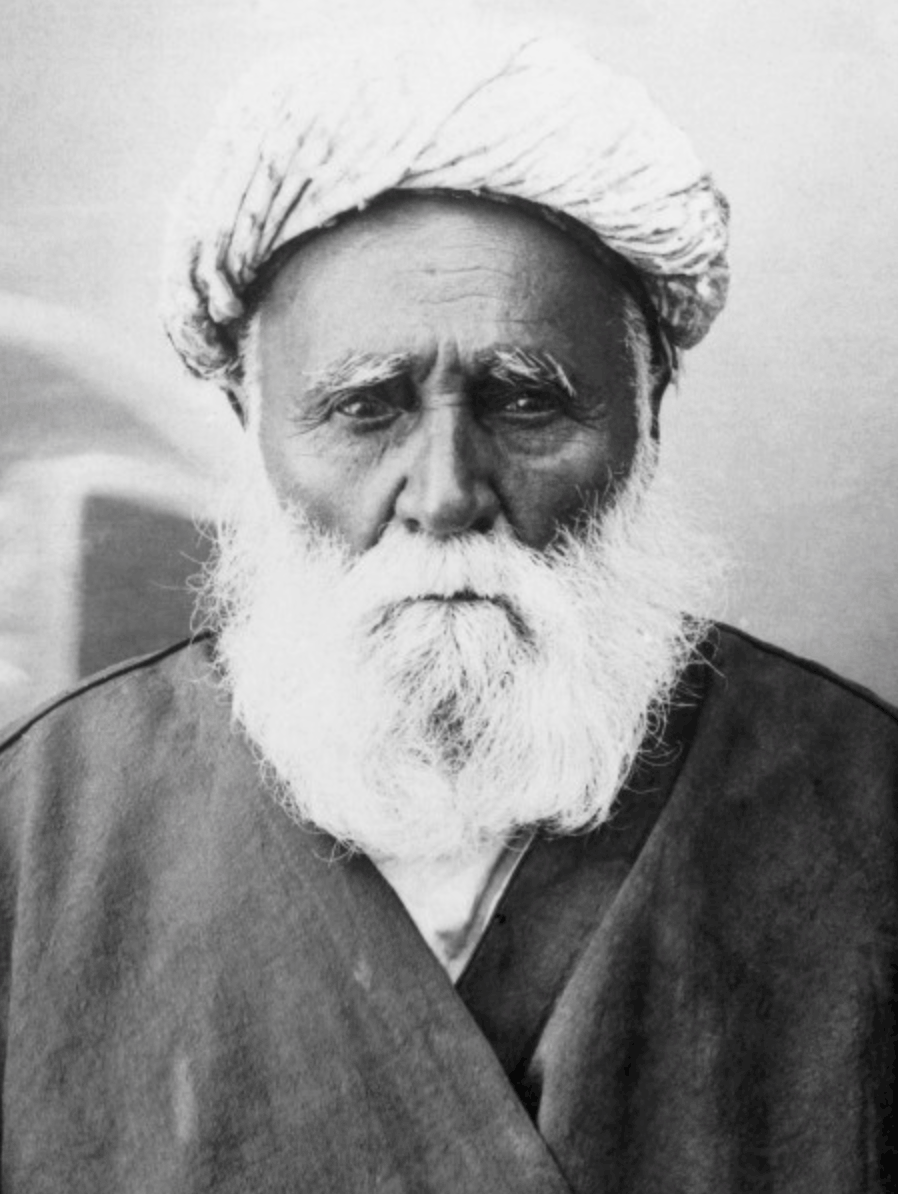

The eminent Ḥájí Amín, Apostle of Bahá'u'lláh, Hand of the Cause, Trustee of the Ḥuqúqu’lláh. Source: Bahaimedia.

Hand of the Cause Ḥájí Amín died in 1928, but we do not know the day or month, therefore this post is placed at this point in the chronology purely arbitrarily. Ḥájí Amín, Hand of the Cause, Apostle of Bahá'u'lláh, and the second Trustee of the Ḥuqúqu’lláh for 47 years, was a man of many names.

He was born Abu’l-Ḥasan-i-Ardikání. After he went on pilgrimage he was known as Ḥájí born Abu’l-Ḥasan-i-Ardikání, but he was also known as Mullá Abu’l-Ḥasan, and by his titles, Ḥájí Amín, and Amín-i-Iláhí (Trusted of God). He became a Bahá'í at the age of 17, and self-funded his travels around Persian by being a scribe and living a very simple, almost austere life.

Arriving six months after Bahá'u'lláh, Ḥájí Amín was the first Bahá'í to return to Persia with news of His whereabouts.

In 1880, Bahá'u'lláh appointed Ḥájí Amín the second Trustee of the Ḥuqúqu’lláh and he travelled around Persia and neighbouring countries like Azerbaijan and the region of the Caucasus for 11 years until he was arrested.

In 1891, Hands of the Cause Ḥájí Amín and Ḥájí Ákhúnd were imprisoned in Ṭihrán. Naṣiri'd-Dín Sháh, who liked to have photographs taken of his noteworthy and resilient prisoners—he had commissioned several portraits of Badí’ being tortured—did the same again with Ḥájí Amín and Ḥájí Ákhúnd. He had them photographed seated on the ground wearing their heavy chains around their neck with their jailers towering over them.

That photograph showed nothing but calm and fortitude. 'Abdu'l-Bahá loved the photograph so much he kept a copy near his room in 'Akká.

After 3 years of imprisonment, Ḥájí Amín was released in 1894, and spent all his time traveling for the Ḥuqúqu’lláh. In 1912, Ḥájí Amín travelled to London and brought 'Abdu'l-Bahá Ḥuqúqu’lláh contributions including what is probably the most precious Ḥuqúqu’lláh contribution of all time, two small loaves of dry, black bread and an apple, the humble dinner of a poor Turkmen worker in ‘Ishqábád. 'Abdu'l-Bahá pushed away his plate, opened the handkerchief in which it had been carried, broke off pieces of the bread and handed them to those present, saying:

Eat with me of this gift of humble love.

Ḥájí Amín made a total of 19 pilgrimages to the Holy Land and spent the rest of his life working as the Trustee for the Ḥuqúqu’lláh, until the day he died.

Ḥájí Amín passed away in Ṭihrán prior to July 1928 at the age of 92.

Shoghi Effendi elevated Ḥájí Amín posthumously to the rank of Hand of the Cause of God in an untranslated letter written in a mixture of Persian and Arabic and addressed to the Friends in Persia. Adib Masumian, provisional translator of the Writings of the Bahá'í Faith, has translated the last paragraph of this momentous message dated July 1928, as a gift for this chronology, and for this, we are immensely grateful:

The shocking news of the ascension of the honorable Amín-i-Iláhí to the Abhá Kingdom was the cause of immeasurable sorrow and regret. For many successive years, that distinguished individual, that noble soul, was intimately engaged in service to the sacred Threshold with an astonishing resolve and devotion. Not a moment’s peace did he enjoy; not a minute did he rest. In his firmness and faithfulness, he was an example to the companions and righteous ones—and in the extent of his sacrifice, the loftiness of his endeavor, the purity of his intent, and the immaculacy of his nature, he was the leader of the beloved and virtuous. He was accounted as one of the active Hands of the Unseen Abhá in that country [Persia], and numbered with the specially favored souls near to the divine Court. His is an exalted station, and his resplendent services will not be effaced with the passing of centuries and ages. The value of these sanctified souls is not known today. Soon will the men of the earth take pride in them, and the denizens of this realm remember the traces they left behind, and the masses of humanity vaunt them over all the world. May God grant him a dwelling-place in the vastness of His paradise, rain down the showers of his mercy and beneficence upon his radiant grave, and immerse him in the depths of His forgiveness and pardon. He is, in truth, the Sustainer, the Forgiver, the Pardoner, the All-Powerful, the Most Exalted, the Almighty.

A women’s meeting inside the House of Worship in ‘Ishqábád, Turkmenistan, which was seized by the Soviet Union on 22 June 1928. The women and girls would take turns reading or chanting prayers. The exquisite interior of the Mashriqu’l-Adhkár is evident in this photograph. Source: Bahá'í Historical Facts.

‘Ishqábád, Turkmenistan was home to one of the oldest Bahá'í communities in the world after Persia, and many Persian Bahá'ís emigrated there at the end of the 19th century to enjoy a safe haven from the constant persecutions in their native land. Bahá'ís built the very first House of Worship in Bahá'í history under the guidance of 'Abdu'l-Bahá in ‘Ishqábád, opened Bahá'í schools and, by 1928, had elected several Local Spiritual Assemblies in ‘Ishqábád, Moscow and other cities in the Soviet Union and two Central Spiritual Assemblies.

By 1928, the Soviet Union was on its second anti-religious campaign, following the first which started in 1921 and ended in 1928, This second campaign would last from 1928 to 1941, and further the goals of replacing religion with agnosticism and atheism and a materialist world view, fundamental goals of the communist state. They wanted to erase religion, and the Bahá'ís were swept up in a blanket state policy. Until 1928, the Bolsheviks, who had assumed power in 1917, had allowed the Bahá'ís to carry on with their community activities, but under Stalin’s regime, starting in 1922, the Bahá'í community came under increasing pressure and later, open persecution.

This is the major way in which the persecution of Bahá'ís in the Soviet Union differs from persecution in Persia: they were not specifically targeted just because they were Bahá'ís, they were victims along with all other religious communities.

On 22 June 1928 Shoghi Effendi received a cable from the ‘Ishqábád Assembly as follows:

In accordance general agreement 1917 Soviet Government has nationalized all Temples but under special conditions has provided free rental to respective religious communities regarding Mashriqu’l-Adhkár government has provided same conditions agreement to Assembly supplicate guidance by telegram.

The Guardian took immediate action, cabling the Moscow Assembly to vigorously intercede with the Soviet authorities and prevent the expropriation of the House of Worship in ‘Ishqábád, and he instructed the Local Spiritual Assembly of Moscow to petition government authorities on behalf of the Bahá'ís of Russia.

Shoghi Effendi later explained in a long letter dated 1 January 1929 on this subject that the Russian Bahá'ís had been brought under the "rigid application of the principles already enunciated by the state authorities and universally enforced with regard to all other religious communities."

Shortly after 22 June 1928, the Soviet Union had—faithful to their anti-religious state policy—expropriated the House of Worship of ‘Ishqábád, suspended all Bahá'í meetings, suppressed all Bahá'í communities, Local and National Spiritual Assemblies, prohibited fund-raising, required frequent inspection of their meetings, imposed strict censorship on their correspondence, suspended all Bahá'í newsletters, and deported leading Bahá'ís and well-known Bahá'í speakers and Assembly officers.

Soviet Union poster promoting their anti-religious campaign during which the House of Worship in ‘Ishqábád was seized. The poster reads: “Religion slows the five year plan! Down with religious holidays!” Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Shoghi Effendi went on to say that after the Bahá'ís in Turkistan and the Caucasus had unsuccessfully exhausted every legitimate means for the alleviation of these restrictions imposed upon them, they had resolved to “conscientiously carry out the considered judgment of their recognized government” and “with a hope that no earthly power can dim...committed the interests of their Cause to the keeping of that vigilant, that all-powerful Divine Deliverer...”

The Guardian described the Bahá'í community’s law-abiding response to these sanctions, which he describes as "measures which the State, in the free exercise of its legitimate rights, has chosen to enforce":

the followers of the Faith of Bahá'u'lláh have with feelings of burning agony and heroic fortitude unanimously and unreservedly submitted, ever mindful of the guiding principles of Bahá'í conduct that in connection with their administrative activities, no matter how grievously interference with them might affect the course of the extension of the Movement, and the suspension of which does not constitute in itself a departure from the principle of loyalty to their Faith, the considered judgment and authoritative decrees issued by their responsible rulers must, if they be faithful to Bahá'u'lláh's and 'Abdu'l-Bahá's express injunctions, be thoroughly respected and loyally obeyed.

Three months later, in September 1928, Shoghi Effendi wrote a letter to Martha Root in which he describes not only the events in the Soviet Union but their effect on him:

It has been a very depressing summer this year for me as the condition of the Cause in Russia is going from bad to worse. The Mashriqu’l-Adhkár has been appropriated by the State, closed and sealed. A very large sum is required from the friends if rented to them, otherwise they threaten to sell it to others in parts. The situation is very critical and many families have migrated to Persia. Meetings are suspended, Assemblies dissolved, heavy restrictions and penalties imposed...this and other happenings have made me feel very down-hearted and sad.

One thing the Guardian did not approve of was the return of the Russian Bahá'ís to Persia. He informed the ‘Ishqábád Assembly that "departure friends Iran exceedingly harmful." In the past, the Guardian had already encouraged Bahá'ís living in ‘Ishqábád to learn the language and publish literature in Russian, and in 1929, he encouraged them to obtain Russian citizenship if possible, weather the storm and stay strong at their post.

In April 1930, the Guardian launched a campaign to attempt to recover the House of Worship in ‘Ishqábád, which the Bahá'ís had succeeded in renting, but which it looked like they might soon lose for good. In the end, the Soviet government refused to concede, and Shoghi Effendi was forced to cable:

…abide by decision State Authorities.

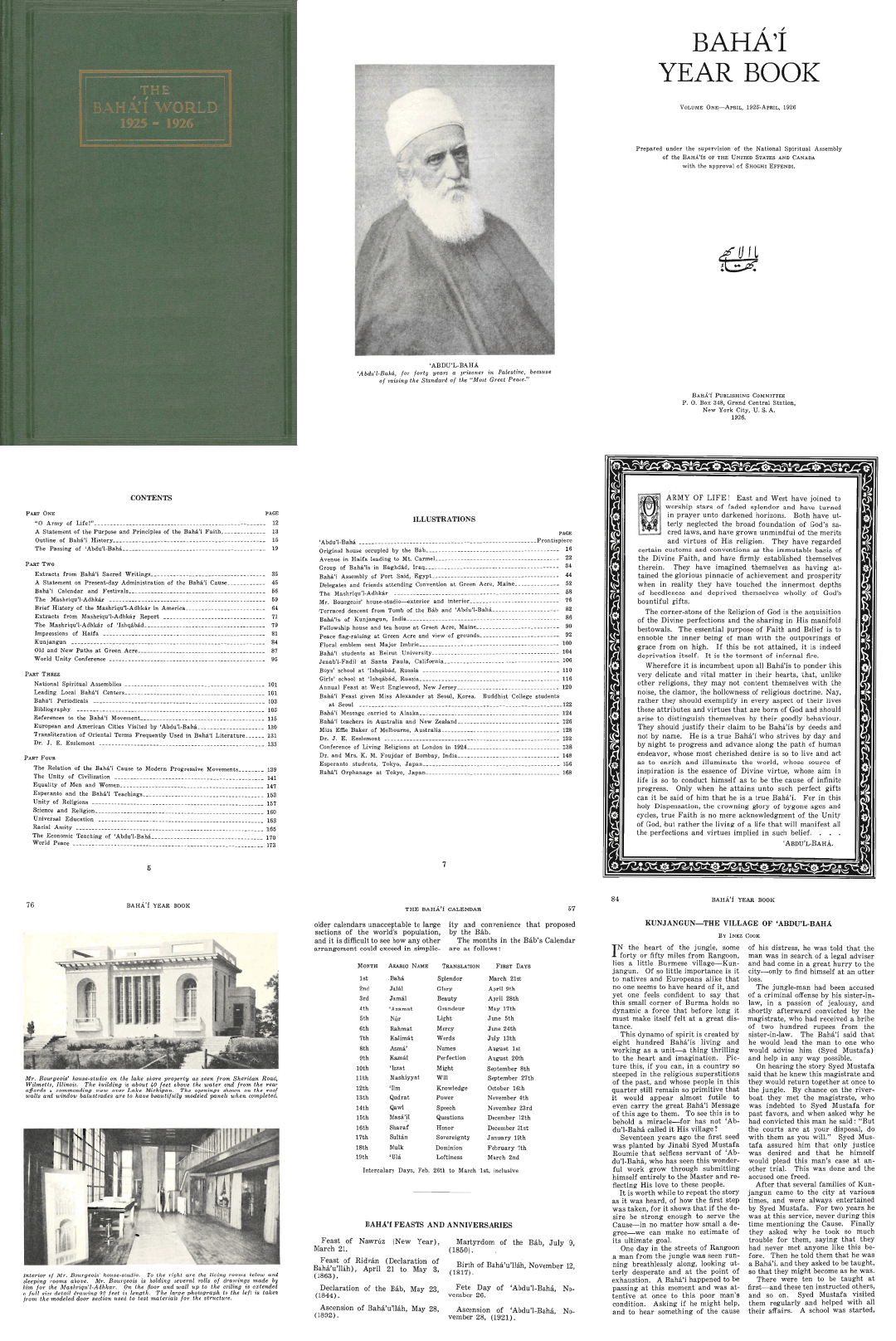

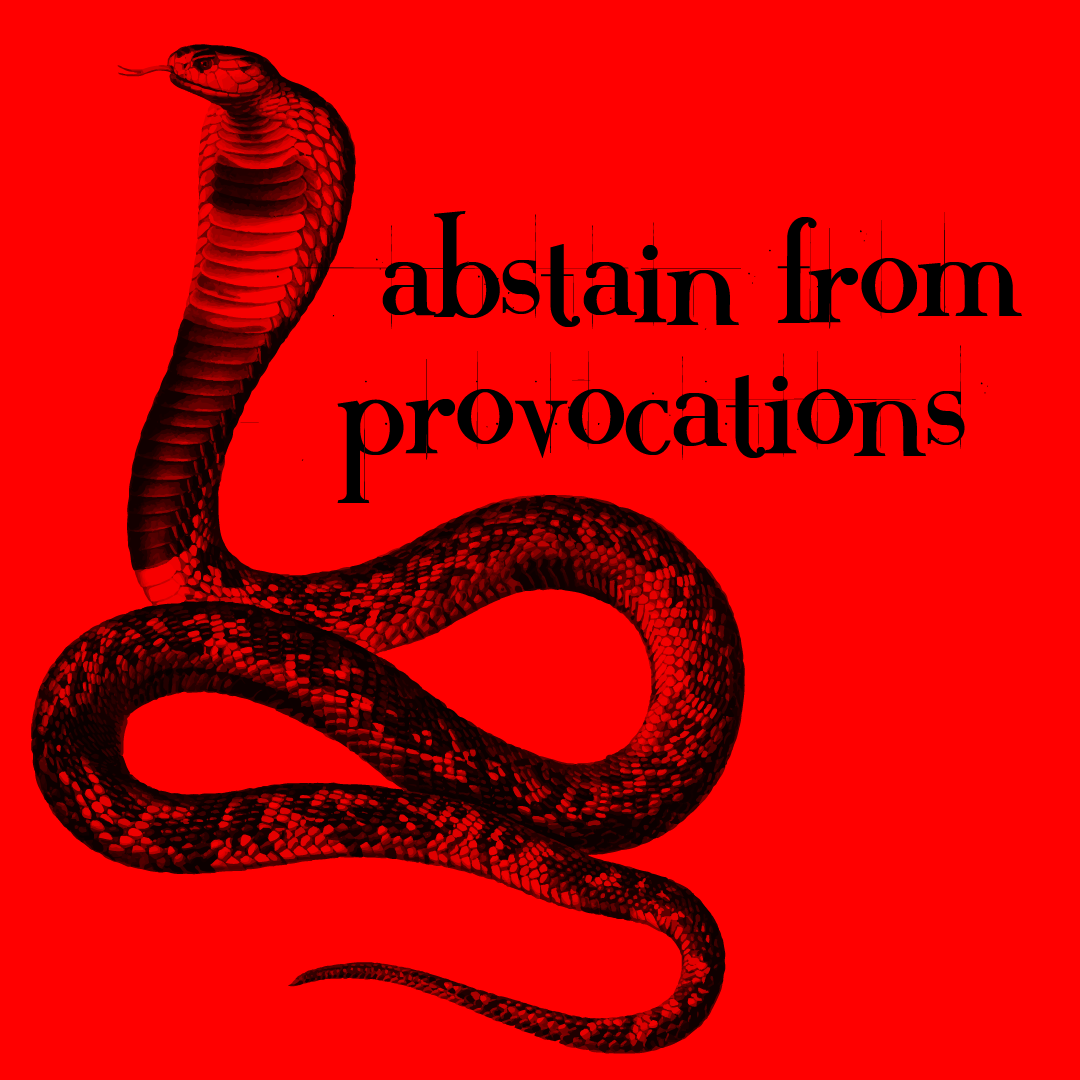

The Bahá'í World Volume 1: A sample of the extraordinary diversity of this publication, from rare photographs of the studio of Louis Bourgeois, the archictect of the Bahá'í House of Worship in North America, to an article about “'Abdu'l-Bahá’s village” in Burma, a useful Bahá'í calendar, etc.

The year after the publication of The Bahá'í World’s first volume covering the accomplishments of the Bahá'í community from 1925 to 1926, Shoghi Effendi had already expressed his attachment to the publication, writing to a person who was not Bahá'í:

I would strongly advise you to procure a copy of the Bahá'í Year Book…which will give you a clear and authoritative statement of the purpose, the claim and the influence of the Faith.

On 6 December 1928, Shoghi Effendi wrote a letter addressed to “the beloved of the Lord and the handmaids of the Merciful throughout the West,” and devoted, in its entirety, to the importance of The Bahá'í World. The Guardian enthusiastically described the publication and his commitment to and interest in it and emphasized its great value, encouraging all believers to widely circulate it. This is how Shoghi Effendi begins describing The Bahá'í World:

This unique record of world-wide Bahá’í activity attempts to present to the general public, as well as to the student and scholar, those historical facts and fundamental principles that constitute the distinguishing features of the Message of Bahá’u’lláh to this age. I have ever since its inception taken a keen and sustained interest in its development, have personally participated in the collection of its material, the arrangement of its contents, and the close scrutiny of whatever data it contains.

I confidently and emphatically recommend it to every thoughtful and eager follower of the Faith, whether in the East or in the West, whose desire is to place in the hands of the critical and intelligent inquirer, of whatever class, creed or color, a work that can truly witness to the high purpose, the moving history, the enduring achievements, the resistless march and infinite prospects of the Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh.

In the remainder of this letter, Shoghi Effendi calls The Bahá'í World eminently readable and attractive, reliable and authoritative, up-to-date, accurate, comprehensive, accurate, concise and persuasive, thoroughly illustrated, unexcelled and unapproached by any other publication, and capable of arousing unprecedented interest in the Faith among all strata of society.

The Guardian also sends out an earnest appeal to the worldwide Bahá'í community to a prompt and widespread dissemination of a book he describes as faithfully and vividly portraying the ”far-reaching ramifications and most arresting aspects” of the all-encompassing Faith of Bahá'u'lláh.

Shoghi Effendi had carefully designed The Bahá'í World to be suitable for the public, for scholars, and for libraries, and to combat malicious rumors and misrepresentations about the Faith.

He had wildly succeeded.

An American professor wrote back to Shoghi Effendi with enthusiastic gratitude at his gift of a volume of The Bahá'í World:

I cannot tell you how much I appreciate being able to study the book, which is exceedingly interesting and inspiring in every way…I congratulate you especially for developing the literature, and keeping alive such a wholesome spirit amongst the persons of many different groups who look to you for leadership.

One of Shoghi Effendi’s greatest tributes to the quality of this volume he so loved and was so invested in, were a series of special tributes to the Bahá'í Faith, written by a proud Queen Marie of Romania especially for The Bahá'í World. The Queen also gave permission for her photograph to appear as the frontispiece for Volume 5, and facsimiles of the Queen’s handwritten and signed appreciation for the Faith were published as frontispieces for Volumes 4, 6, and 8.

In 1931, when Shoghi Effendi received one of the Queen’s especially written tributes for publication in The Bahá'í World, he responded:

No words can adequately express my pleasure at the receipt of your letter enclosing the precious appreciation which will constitute a valuable and outstanding contribution to the forthcoming issue of the Bahá'í World.

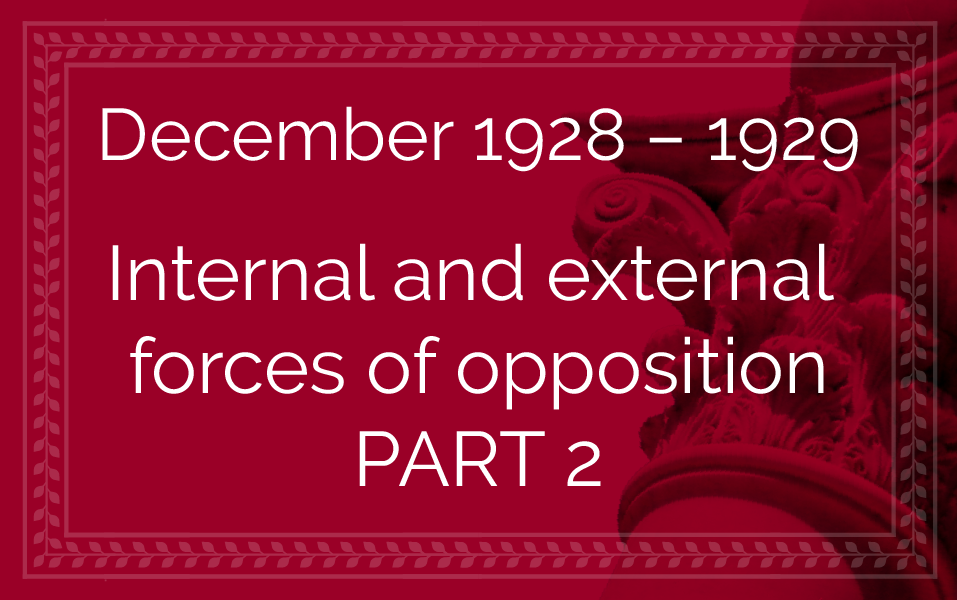

Top: One of Atatürk's many reforms, the abolition of the Caliphate, from Le Petit Journal illustré, 16 March 1924. Among the many other reforms of Atatürk were the Eliminating of religious “associations” from political arena, covered in the story below. Source: Wikimedia Commons. Left: A photo of Nuri Sadik Bey, the chairman of the Local Spiritual Assembly of Istanbul, while defending the Bahá'í Faith in Court. Source: The Martha Root Archives, National Spiritual Assembly of Hawaii (courtesy of Payam Afsharian via Dr. Necati Alkan). Used with permission. Right: Front page article from the Istanbul newspaper Milliyet dated 9 December 1928 about Queen Marie, the title reads: "The trial began: what is Baha’ism supposed to be? Yesterday those who set up a secret organization were tried." The caption of the photo of Queen Marie reads: "As was disclosed during the trial the Romanian Queen sent a letter to the Baha’i organization when she arrived in Istanbul; she also is a Bahá'í." Source: Dr. Necati Alkan.

Bottom: A photograph of the seven members of Local Spiritual Assembly of Istanbul, taken on 9 October 1928, the day they were arrested. Source: Mehrdad Mohregi via Dr. Necati Alkan, used with permission.

This section was a collaboration with the foremost specialist of the Bahá'í faith in the Ottoman Empire, Dr. Necati Alkan.

After the Young Turk Revolution in 1908, specifically after losing World War I in 1918, the Ottoman Empire fell apart and the Republic of Turkey was proclaimed in 1923, followed by an intense policy of secularization—separating Islam and state affairs—and wide-ranging civil reforms in 1928, which included removing Islam as the state religion in the Constitution and adopting the Latin alphabet for the Turkish language.

It came to the Turkish government’s attention that certain so-called religious groups had, in the past, provided cover for political agitators. They discovered that the Bahá'í Faith was not only an organized religion, but that it openly pursued its activities of teaching and propagating the Faith, and they became suspicious.

The Government searched the homes of Bahá'ís in Izmir (Smyrna) and Istanbul (Constantinople), seized all the literature they could find, questioned the believers and sent a number of them to prison. Some of the literature confiscated from the Local Spiritual Assembly of Istanbul were one of the tributes of Queen Marie of Romania to the Bahá'í Faith and her letter to the Bahá'ís of that city.

The case was widely reported in the European and of course the Turkish press, whose sympathy lay with the Bahá'í community, and the great deal of publicity ensured that the Bahá'ís were allowed a full and impartial hearing when the case reached the Criminal Tribunal on 13 December 1928.

This tribunal was a great step in the unfoldment of Baha’u’llah’s Cause, as Shoghi Effendi stated:

Never before in Bahá'í history have the follower of Bahá'u'lláh been called upon by the officials of a state…to unfold the history and principles of their Faith…

The President of the Local Spiritual Assembly of Istanbul was called on to explain the principles of the Faith, which he did brilliantly.

In the end, the Bahá'ís were found totally innocent and made to pay a fine of 25 Turkish Liras for not having registered their association with the government, and not having obtained proper authorization to hold public meanings.

The effects of this case, both locally and internationally, were deeply significant. The Faith had been publicly found to be a divine, independent, world religion. This was how the Guardian presented this historic verdict to the Bahá'ís of the West in his letter dated 12 February 1929:

As to the verdict…it is stated clearly that although the followers of Bahá'u'lláh, in their innocent conception of the spiritual character of their Faith, found it unnecessary to apply for leave for the conduct of their administrative activities and have thus been made liable to the payment of a fine, yet they have, to the satisfaction of the legal representatives of the State, not only established the inculpability of the Cause of Bahá'u'lláh, but have also worthily acquitted themselves of the task of vindicating its independence, its Divine origin, and its suitability to the circumstances and requirements of the present age.

Shoghi Effendi categorically stated that the Will and Testament of 'Abdu'l-Bahá was authentic beyond the shadow of a doubt. It had been authentified several times by several people, so many people still alive in 1930 knew 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s handwriting by heart, and recognized his seals.

Ruth White, the most notorious American Covenant-breaker, threw herself into her lunacy.

She wrote countless letters to the National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá'ís of the United States and Canada, as well as to some believers, in which she vehemently objected to the directives of Shoghi Effendi and the administration of the Cause through the local and national institutions.

She wrote to the United States Postmaster General, asking him to prohibit the National Spiritual Assembly of the United States and Canada from using the United States Postal Service to, in her words:

To spread the falsehood that Shoghi Effendi is the successor of 'Abdu'l-Bahá and Guardian of the Bahá'í Cause.

On 31 December 1928, Ruth White wrote to the civil authorities in Palestine, and made an official request that they declare the Will and Testament of 'Abdu'l-Bahá a forgery.

This caused the Guardian unneeded worry at a time where he was already overburdened with work and stress.

In January 1929, the National Spiritual Assembly of the United States and Canada forwarded the Guardian a pamphlet published by Ruth White and on 27 February 1929 the Guardian responded, writing :

I have in a letter addressed to the National Assembly set forth my views regarding the contents of Ruth White’s pamphlet. I have thus far received no intimation from the Palestine authorities, and have no reason to believe that they will consider it worthy of their consideration. The friends, however, should avoid hurting her feelings and should abstain from provocation.

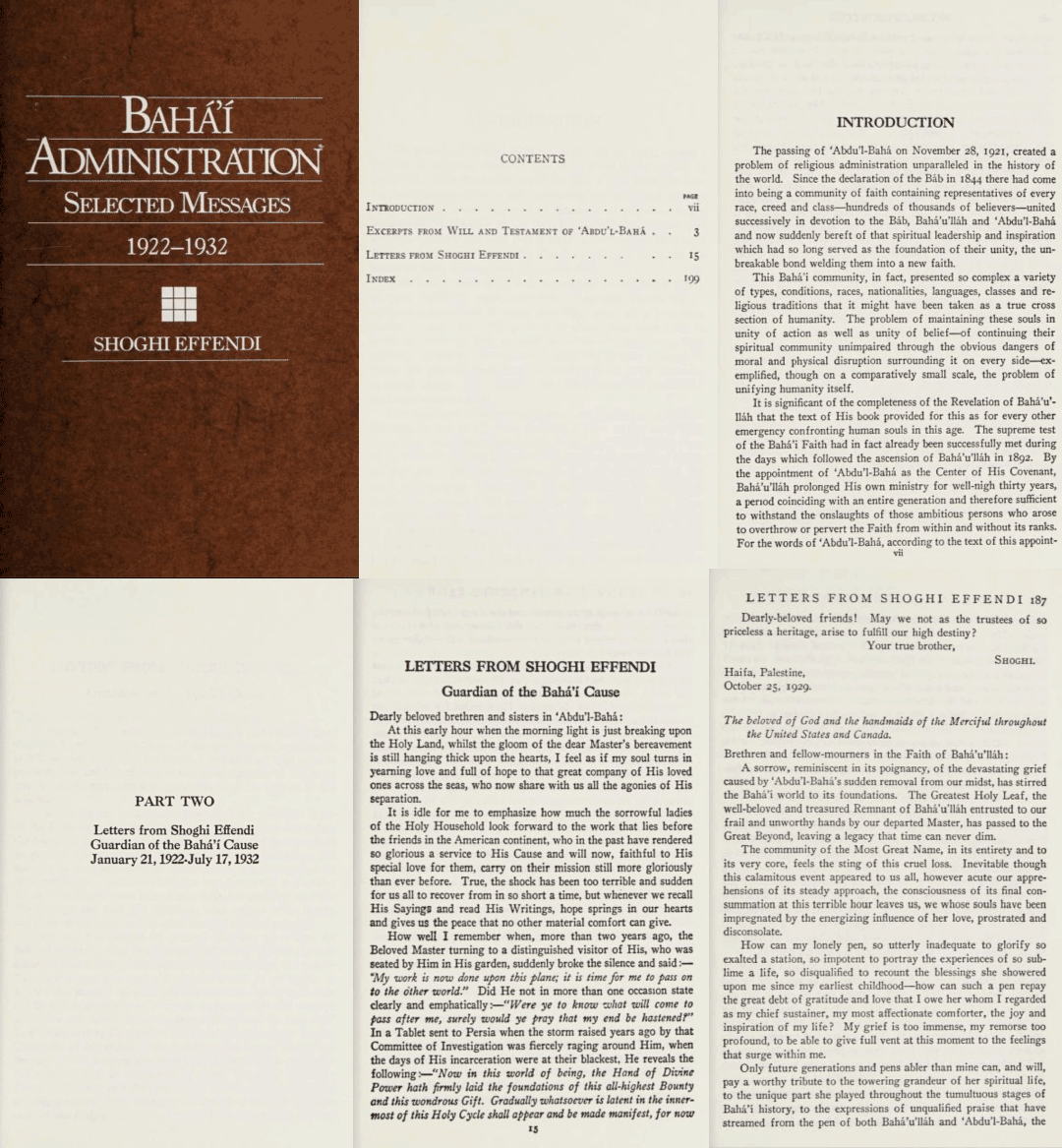

Images of the cover, table of content, first page of Horace Holley’s introduction, part 2 containing the letters of the Guardian, the first page of the first letter dated 21 January 1922, and the first page of the last letter dated 17 July 1932. Source: Internet Archive.

Bahá’í Administration was the very first compilation of Shoghi Effendi’s letters to ever be published in 1928. The compilation was revised twice and its current form is the 1941 publication and covers a period of ten years of letters from Shoghi Effendi addressed to the Bahá'ís of the United States and Canada from 21 January 1922 to 11 April 1933.

In the first letter included in Bahá'í Administration, dated two months after the Ascension of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, Shoghi Effendi expresses his deep sorrow at the passing of the Master, describing it as a “shock…too terrible and sudden for us all to recover from in so short a time.”

The last letter in the compilation, dated 11 April 1933 and titled Personalities Subordinated discusses various considerations regarding the delicate issue of removing voting rights.

After the book was published in its last edition Shoghi Effendi, in a letter written to a National Assembly on his behalf, made the following comment about its importance:

Two years after its publication, the Guardian suggested to the National Spiritual Assembly India that it carefully deepen itself on all the ramifications of the Bahá'í Administrative Order by studying Bahá'í Administration in a letter dated 9 may 1934:

The Guardian would strongly urge each and every member of the National Spiritual Assembly to carefully peruse, and to quietly ponder upon the outer meaning and upon the inner spirit as well, of all his communications on the subject of the origin, nature and present-day functioning of the administrative order of the Faith. A compilation of these letters has been lately published in the States under the title 'Bahá'í Administration', and a complete knowledge of that book seems to be quite essential to the right handling of the administrative problems facing your National Spiritual Assembly at present.

This majestic excerpt from Bahá'í Administration, from a letter dated Letter of 24 September 1924 is from a section of that letter called Our Inner Life, and it exemplifies the Guardian’s writing at its best, at its most momentous as it calls Bahá'ís, though few in number, to the greatest heights of heroism:

Humanity, through suffering and turmoil, is swiftly moving on towards its destiny; if we be loiterers, if we fail to play our part surely others will be called upon to take up our task as ministers to the crying needs of this afflicted world.

Not by the force of numbers, not by the mere exposition of a set of new and noble principles, not by an organized campaign of teaching – no matter how worldwide and elaborate in its character – not even by the staunchness of our faith or the exaltation of our enthusiasm, can we ultimately hope to vindicate in the eyes of a critical and sceptical age the supreme claim of the Abhá Revelation. One thing and only one thing will unfailingly and alone secure the undoubted triumph of this sacred Cause, namely, the extent to which our own inner life and private character mirror forth in their manifold aspects the splendor of those eternal principles proclaimed by Bahá’u’lláh.

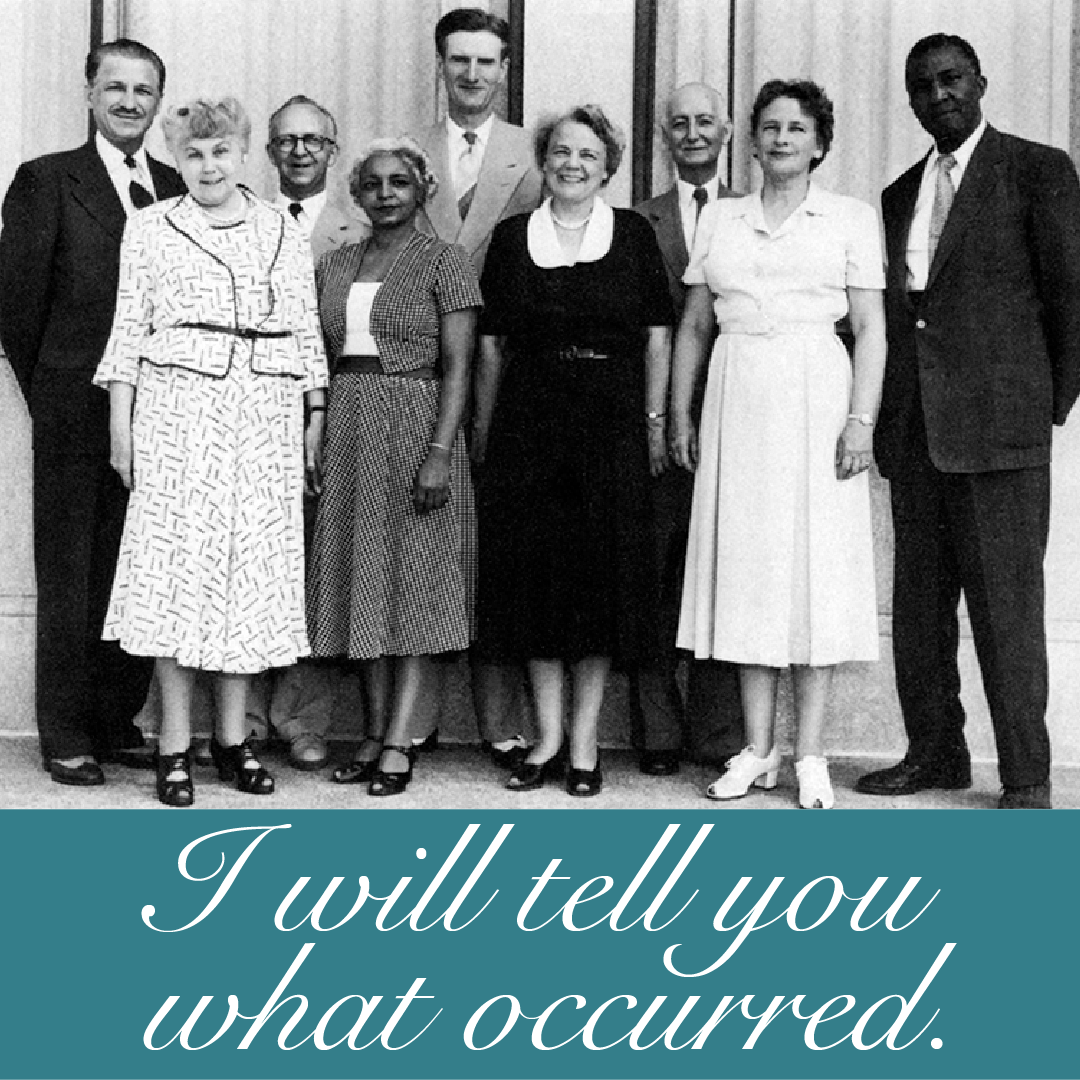

The Permanent Mandates Commission in Geneva in 1924. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Shoghi Effendi never rested until the case of the Most Great House was brought before the League of Nations. On 11 September 1928, the National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá’ís of Iraq submitted a petition to the Permanent Mandates Commission of the League of Nations in Geneva, Switzerland, for the return of the House of Bahá’u’lláh in Baghdád, a petition which reads, in part, that one of the most Holy Places of the Bahá'í community:

…has been unlawfully wrested from their possession and they have been deprived of the spiritual solace and inspiration of its use in their worship. This it is alleged has been brought about through the machinations of the leaders of the Shí‘ah sect of Islám…It is against this alleged violation of their constitutional treaty guarantees that your petitioners seek your aid and protection.

Between 26 October and 13 November 1928, the case of the Most Great House of Bahá’u’lláh in Baghdád was taken before the fourteenth session of the Permanent Mandates Commission of the League of Nations, where it was accepted and approved.

The British Government issued a memorandum unequivocally stating that the Shí’ah had "no conceivable claim whatever" to the Most Great House, and that the decision of the judge of the Iraqi tribunal was not only "obviously wrong," but "unjust" and "undoubtedly actuated by religious prejudice."

Three months after what seemed to be a permanent victory, Shoghi Effendi sent a short cable in February 1929, but asked not to give the victory much publicity:

League Council pronounced in favor Bahá'í Petition regarding Bahá'u'lláh House. Faith triumphant over deadliest enemy. Inform believers. Avoid for present widespread publicity. Cause much indebted to Mountfort's magnificent achievement.

On 4 March 1929, The Council of the League of Nations adopted the conclusion reached by the Mandates Commissions upholding the claim of the Bahá’í community to the Most Great House of Bahá’u’lláh in Baghdád. The Mandates Commission recommended that the Council of the League of Nations request the British Government to address the injustice suffered by the National Spiritual Assembly of Iraq in the case of the Most Great House directly with the Iraqi Government.

But the next month, in April 1929, King Faisal, a Sunní, caved under the pressure applied by the Shí’ah who threatened unrest, and the Most Great House was not returned to the Bahá’ís.

The matter was far from resolved.

In November 1929, the case of the Most Great House was again brought before the sixteenth session of the Permanent Mandates Commission of the League of Nations which received a petition drafted by Mountford Mills.

The right of the Bahá’ís to the House was upheld and the government of Iraq was strongly pressed to find a solution but the Most Great House was still not returned to the Bahá'ís.

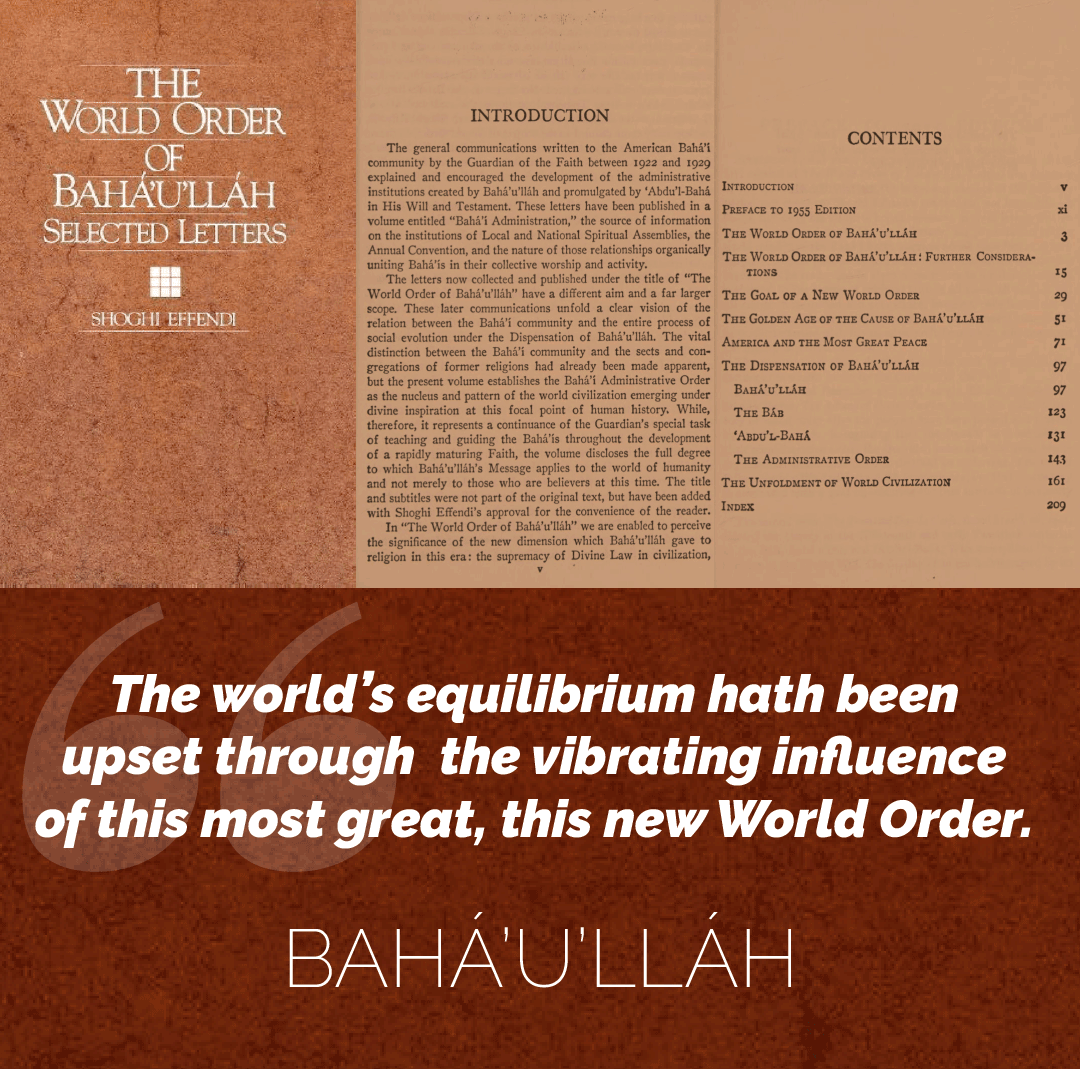

In the middle of the Great Depression, Shoghi Effendi published two very important compilations of letters addressed to the Bahá'ís of the United States and Canada and other western countries in a compilation. The first was The World Order of Bahá'u'lláh, published on 27 February 1929.

The following year, on 21 March 1930, the Guardian updated the compilation and released it under the title The World Order of Bahá'u'lláh: Further Considerations.

In these dark hours of worldwide economic chaos, disrupting the very foundations of the Old World Order, the Guardian felt the time had come to explain to the Bahá'ís of the West not only the sources, but the broad outlines of the New World Order ushered in by Bahá'u'lláh.

The aim of these two compilations was to clarify the meaning and purpose of the Bahá'í Faith, its beliefs, its implications, its destiny and its future, in order to guide the Bahá'í communities in North America and in the West to a better understanding of their duties and privileges and their destiny, while the Guardian led the unfoldment of Bahá'u'lláh’s Administrative Order.

One of the ways in which Shoghi Effendi did this was to call the Bahá'ís’ attention to the commonalities between the Kitáb-i-Aqdas and the Will and Testament of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, respectively authored by the Founder of the Bahá'í Dispensation and the Center of the Covenant of Bahá'u'lláh’s Faith.

Shoghi Effendi, the authorized interpreter of the Bahá'í Holy Writings, made seven extraordinary statements regarding the intertwined relationship between Bahá'u'lláh’s Kitáb-i-Aqdas and the Will and Testament of 'Abdu'l-Bahá:

- Together, they constituted “the chief depository wherein are enshrined those priceless elements of that Divine Civilization, the establishment of which is the primary mission of the Bahá’í Faith.”;

- They both had the same purpose

- They both had identical provisions for successorship—Bahá'u'lláh expressly naming 'Abdu'l-Bahá as His successor, and 'Abdu'l-Bahá explicitly naming Shoghi Effendi as His;

- The Will and Testament, in the Guardian’s own words, “confirms…the provisions of the Aqdas.”

- It also “supplements” these same provisions;

- In the same sentence, the Guardian states that 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s Will and Testament “correlates the provisions of the Aqdas.”

- In Shoghi Effendi’s words, the Will and Testament of 'Abdu'l-Bahá and the Kitáb-i-Aqdas were “inseparable parts of one complete unit.”

A photomontage of 64 of the world’s leaders in 1930, when Shoghi Effendi referred to them in a letter in the World Order of Bahá'u'lláh. Sources: World’s religious leaders in 1930 (Wikipedia), Philosophers of the world in 1930 (Wikipedia), Kings, Queens, and Presidents of the world in 1930 (Wikipedia).

This excerpt from The World Order of Bahá'u'lláh lays out in elevated and sublime terms the Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh and his New World Order as the last hopes for a fledgling humanity, and the heavy responsibility that rests on the small band of His devoted followers:

Leaders of religion, exponents of political theories, governors of human institutions, who at present are witnessing with perplexity and dismay the bankruptcy of their ideas, and the disintegration of their handiwork, would do well to turn their gaze to the Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh, and to meditate upon the World Order which, lying enshrined in His teachings, is slowly and imperceptibly rising amid the welter and chaos of present-day civilization. They need have no doubt or anxiety regarding the nature, the origin or validity of the institutions which the adherents of the Faith are building up throughout the world. For these lie embedded in the teachings themselves, unadulterated and unobscured by unwarrantable inferences, or unauthorized interpretations of His Word.

How pressing and sacred the responsibility that now weighs upon those who are already acquainted with these teachings! How glorious the task of those who are called upon to vindicate their truth, and demonstrate their practicability to an unbelieving world! Nothing short of an immovable conviction in their divine origin, and their uniqueness in the annals of religion; nothing short of an unwavering purpose to execute and apply them to the administrative machinery of the Cause, can be sufficient to establish their reality, and insure their success. How vast is the Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh! How great the magnitude of His blessings showered upon humanity in this day! And yet, how poor, how inadequate our conception of their significance and glory! This generation stands too close to so colossal a Revelation to appreciate, in their full measure, the infinite possibilities of His Faith, the unprecedented character of His Cause, and the mysterious dispensations of His Providence.

In a letter to Mary Maxwell dated 8 March 1929, May Maxwell shares the five steps for prayer and meditation which Ruth Moffet had heard from Shoghi Effendi during her pilgrimage, and which she widely disseminated. These, of course are pilgrim notes, and not to be considered as having the same weight as letters from Shoghi Effendi.

Step 1

Pray and meditate about it. Use the prayers of the Manifestations as they have the greatest power. Then remain in the silence of contemplation for a few minutes.

Step 2

Arrive at a decision and hold this. This decision is usually born during the contemplation. It may seem almost impossible of accomplishment but if it seems to be as answer to a prayer or a way of solving the problem, then immediately take the next step.

Step 3

Have determination to carry the decision through. Many fail here. The decision, budding into determination, is blighted and instead becomes a wish or a vague longing. When determination is born, immediately take the next step.

Step 4

Have faith and confidence that the power will flow through you, the right way will appear, the door will open, the right thought, the right message, the right principle or the right book will be given you. Have confidence, and the right thing will come to your need. Then, as you rise from prayer, take at once the fifth step.

Step 5

Then, he said, lastly, ACT; Act as though it had all been answered. Then act with tireless, ceaseless energy. And as you act, you, yourself, will become a magnet, which will attract more power to your being, until you become an unobstructed channel for the Divine power to flow through you. Many pray but do not remain for the last half of the first step. Some who meditate arrive at a decision, but fail to hold it. Few have the determination to carry the decision through, still fewer have the confidence that the right thing will come to their need. But how many remember to act as though it had all been answered? How true are those words-"Greater than the prayer is the spirit in which it is uttered" and greater than the way it is uttered is the spirit in which it is carried out.

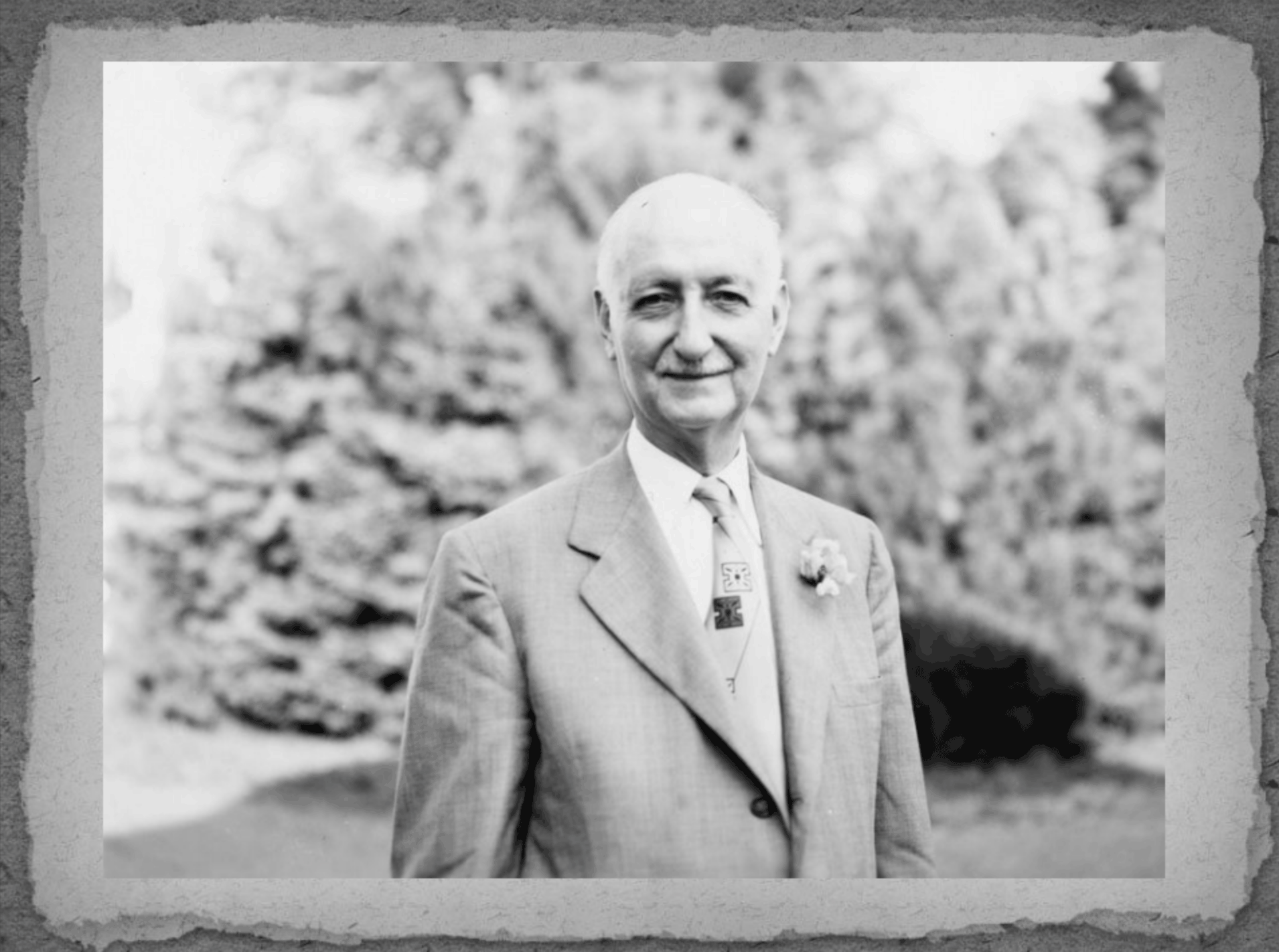

The talented Horace Holley, secretary of the National Spiritual Assembly of the United States and Canada from 1925 until 1959 (except for a brief period). He was a well-known poet, essayist, playwright, businessman, and thinker. He played a. pivotal role in the development of the Administrative Order and became known for his writings. Source: Wilmette Institute.

Horace Holley, the Secretary of the National Spiritual Assembly of the United States and Canada, was a talented writer, and, the Guardian allowed him to use his considerable talent to give titles to his epoch-defining letters from 1929 to 1957.

Horace Holley’s service in titling not only the Guardian’s letters, but the sections within the letters, served to not only identify his letters, but also dramatize Shoghi Effendi’s message, and capture the imagination of Bahá'ís.

The way Horace Holley titled the letters was to pick up the most stunning and appropriate turns of phrases used by the Guardian that could describe either the general subject of the entire letter or that specific thematic part.

In all his historic, epoch-defining letters from 1929 to 1957, it was Horace Holley, with the Guardian’s approval, who gave them their distinctive titles and subtitles, always excerpted from the words of Shoghi Effendi himself.

Horace Holley provided this service for the letters below:

- 1929: The World Order of Bahá'u'lláh

- 1930: The World Order of Bahá'u'lláh Further Considerations

- 1931: The Goal of a New World Order

- 1932: The Golden Age of the Cause of Bahá’u’lláh

- 1933: America and the Most Great Peace

- 1934: The Dispensation of Bahá’u’lláh

- 1936: The Unfoldment of World Civilization

- 1938: The Advent of Divine Justice

- 1941: The Promised Day Is Come

- 1957: Messages to the Bahá'í World: 1950-1957

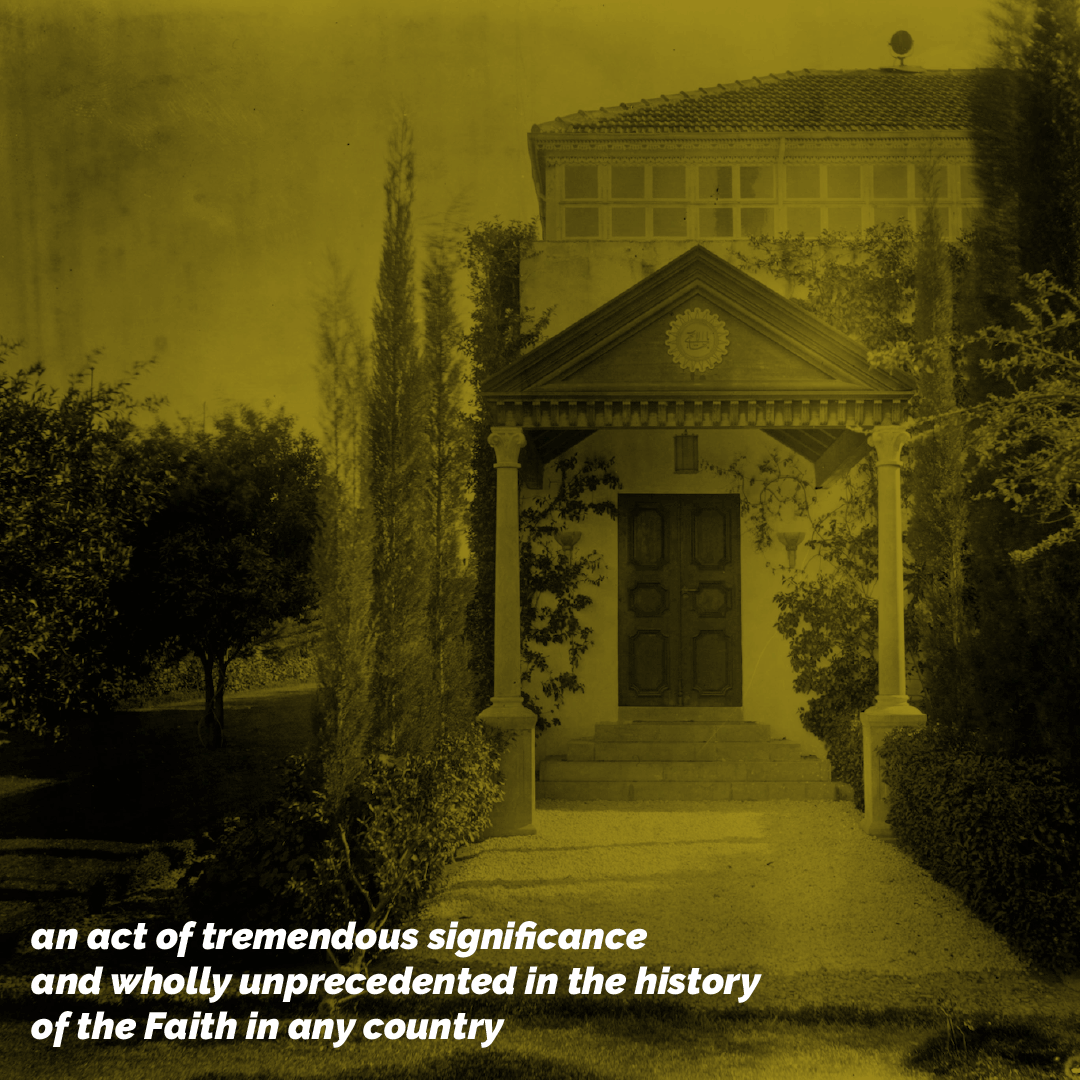

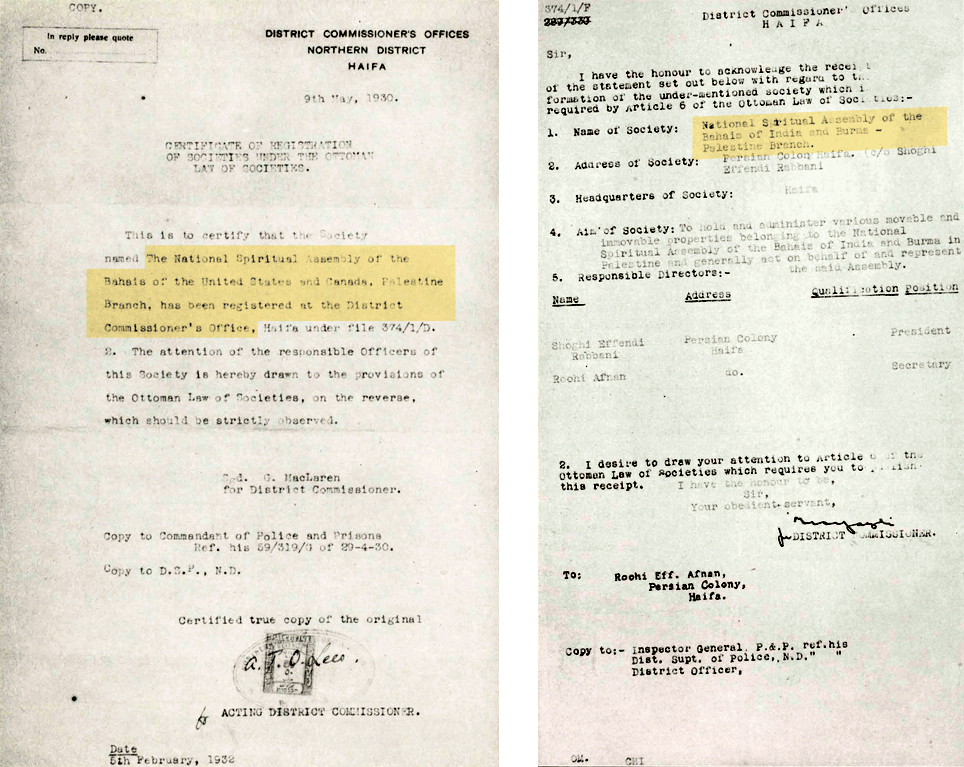

In the Holy Land, Bahá'ís already had a Bahá'í cemetery, and buried their dead facing the Qiblih, the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh in Bahjí. The community had stopped referring to an Islamic court for all questions of marriage, divorce and the rites of burial, but it was time for this practice to become official.

On 4 May 1929, Shoghi Effendi presented a formal petition from the representatives of the Bahá'í community of Haifa to the government of British Mandate Palestine requesting permission for the Bahá'í community to administer the affairs of the community according to Bahá'í law in matters of civil law such as marriage, divorce, burial laws, pending the adoption of a uniform code of civil law in Palestine.

This petition asked for the Bahá'í community to be fully recognized and be granted “full powers to administer its own affairs now enjoyed by other religious communities in Palestine.”

The petition was granted, and the Bahá'í Faith received official recognition by the civil authorities. Their marriage certificates, issued by the local Bahá'í communities were now valid, something which even the Persian Government’s representative in Palestine tacitly recognized.

The Bahá'í community was now on equal legal footing with Jewish, Muslim and Christian communities in Palestine.

Shoghi Effendi hailed this decision as "an act of tremendous significance and wholly unprecedented in the history of the Faith in any country".

The Guardian's own exclusively Bahá'í marriage to Rúḥíyyih Khánum, eight years later, would be registered and become legal as a result of this recognition he had won for the Faith.

Shoghi Effendi standing in a suit, holding a handkerchief.

In 1929, an Indian Bahá'í pilgrim Shoghi Effendi brilliantly characterized one aspect of Shoghi Effendi, the various intensities of his energy and speed, and in this brief description, gives us an understanding of the immense dynamic strength of the Guardian:

We must understand Shoghi Effendi in order to be able to help him accomplish the stupendous task he has entrusted to us. He is so calm and yet so vibrant, so static and yet so dynamic.

After 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s Ascension, Ahmad Sohrab—who had been His secretary for many years and had traveled with the Master to Europe and Egypt—broke the Covenant—though he would not be declared a Covenant-breaker until 1939—and revealed who he had always been. In his opposition to the Faith, Ahmad Sohrab was as despicable as Avárih, and, before long, faithful Bahá'ís began calling Ahmad Sohrab “The Avárih of the West.”

They were both very prominent in their circles—Avárih in the East and Ahmad Sohrab in the West—and they both wanted the Universal House of Justice elected immediately. And they both wanted to be on it.

As the Guardian began building up the Administrative Order, guiding communities to elect Local Spiritual Assemblies and National Spiritual Assemblies and strengthening these nascent institutions, Ahmad Sohrab rose up against the direction the Guardian was taking the Bahá'í Faith in.

Ahmad Sohrab allied himself with a wealthy woman, Julie Chanler, and in 1929, they created a new organization called “The New History Society,” making a lot of noise and drumming up a lot of publicity to recruit members. Their end goal was to use the indirect method to spread the teachings of the Bahá'í Faith for their own advantage, while, of course simultaneously attacking the Guardian’s directives on building the Administrative Order.

What Ahmad Sohrab did was create a sect of the Bahá'í Faith.

He shamelessly plagiarized the words of Bahá'u'lláh and 'Abdu'l-Bahá as his own, and alienated the Bahá'í community.

Ahmad Sohrab was very strange. He never questioned the authenticity of the Will and Testament of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, but he criticized the Guardian’s leadership and his decisions and stated that Shoghi Effendi was wrong in what he was doing.

In 1930, Ahmad Sohrab created a very weird foundation called the “Caravan of East and West” whose mission was “international correspondence,” designed to prepare children and youth to join the New History Society.

Ahmad Sohrab was deeply unsuccessful in all his ventures, a trait uniting all Covenant-breakers. The Bahá'ís shunned him, and none of his plans or new organizations were in any way successful.

During a period of intensity in Ahmad Sohrab’s nefarious activities, Shoghi Effendi wrote a letter dated 21 March 1934 through his secretary to the National Spiritual Assembly of the United States and Canada:

In regard to the activities of Ahmad Sohrab, Shoghi Effendi has already stated that such attacks, however perfidious, do not justify the friends replying or taking any direct action against them. The attitude of the N. S. A. should be to ignore them entirely. For any undue emphasis on attacks made upon the Cause by Ahmad and his supporters would make them feel that they constitute a real challenge to the Cause and a menace to its institutions. Should these attacks continue and acquire a serious importance the Guardian will surely advise the N. S. A. to take definite and decisive action.

Although the Guardian knew that the doors to electing the Universal House of Justice were closed for the time being, he continued developing an idea that would mature in his mind for a quarter century: that of forming an international Bahá'í Secretariat in the. Holy Land, a competent agency of people that could assist him in His work.

This international Bahá'í secretariat, in Shoghi Effendi’s mind, would be the preliminary step to the formation of the International Bahá'í Council.

On 30 August 1926, Shoghi Effendi wrote to one of the Bahá'ís:

I am anxiously considering ways and means for the formation of some sort of efficient, competent Secretariat in Haifa…I have thought of it a great deal and I am still exploring and searching for a competent, reliable, methodical, and trained associate who, untrammeled and unhampered, can devote…continuous months to such a delicate and responsible task. When this is achieved I cherished the brightest hopes for the strengthening of the vital bonds that bind the Centre in Haifa with all the Assemblies in the Bahá'í world.

In 1929, the Guardian briefly conceived the idea of Bahá'ís holding an international conference on the topic of forming National Spiritual Assemblies in the East.

The response from the Bahá'ís was very disappointing.

Older Bahá'ís wanted to use this conference to establish if a precursor to the Universal House of Justice could be elected. The Guardian sensed from various prominent believers that they wanted to be elected to this interim institution—or to the Universal House of Justice. These were men old enough to be his father, and they still looked upon the Guardian as an inexperienced young man.

This was obvious proof to the Guardian that Bahá'ís were immature and did not understand the Bahá'í Administrative Order fully.

On 12 December 1929, the Guardian was forced to cancel the international conference he had planned, stating it would only be "a source of confusion, misunderstanding and even controversy."

The Guardian kept the idea of this international Bahá'í Secretariat, which slowly matured into his conception of an International Bahá'í Council—formed of members he would appoint himself—safely in his thoughts for the next 20 years.

The story continues on 9 January 1951, with the Guardian’s announcement of the first International Bahá'í Council.

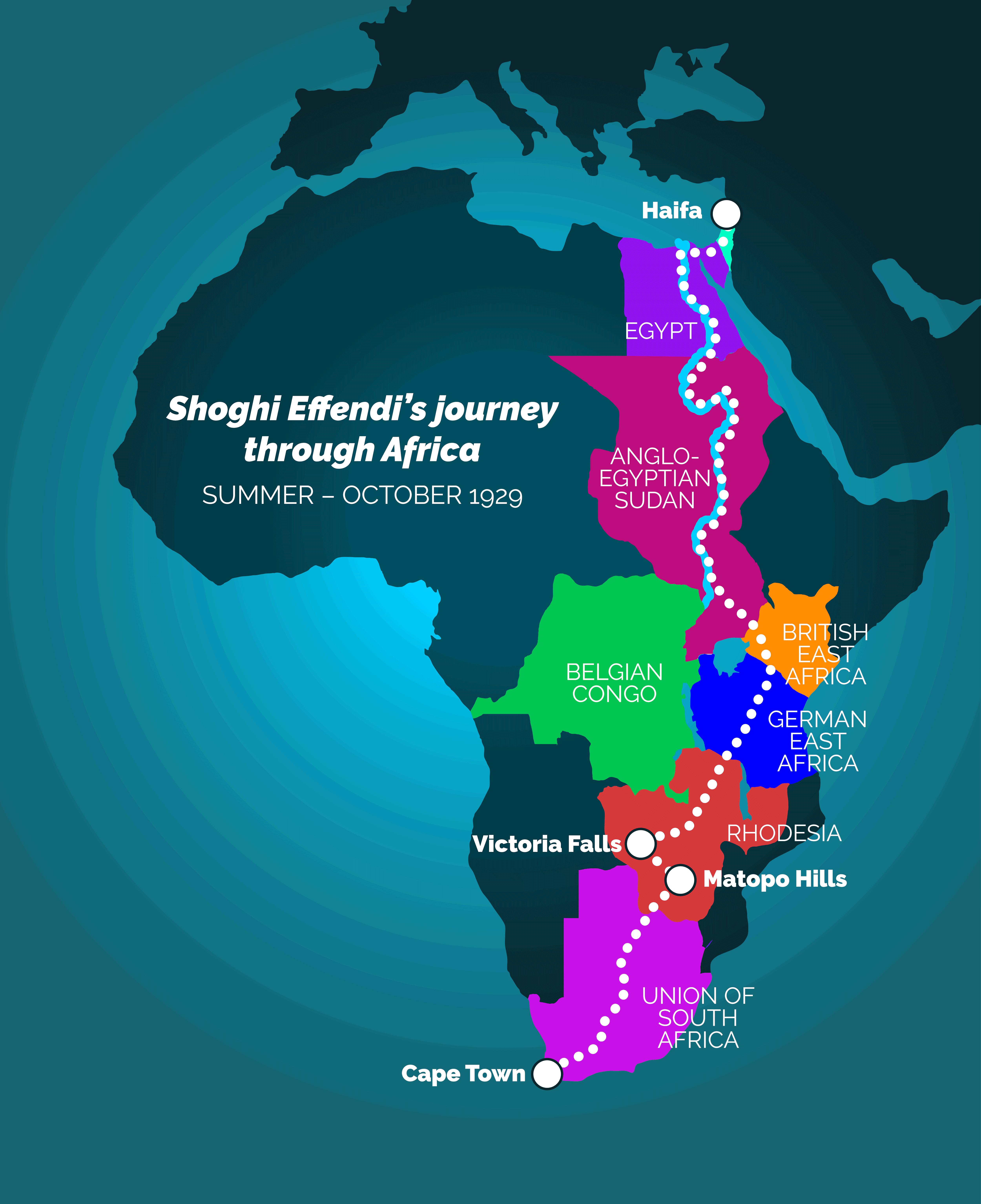

This map of Shoghi Effendi’s journey through Africa in 1929 is approximative. It is not known which direction Shoghi Effendi took upon arriving in Cape Town, though he probably traveled to Johannesburg. The journey through East Africa to the Nile and up the Nile is also symbolic. Shoghi Effendi did travel by train from Egypt to Haifa, so that part is relatively accurate.

Shoghi Effendi left Haifa for Europe in the summer of 1929. We do not know if he traveled to Switzerland, although it is very likely. That year, the Guardian’s adventurous spirit, the same deep love for scenic beauty that had attracted him so many times to the Bernese Alps but also the deep jungles of the world, took him to Africa for his first great journey across the continent.

Shoghi Effendi sailed to Cape Town, South Africa, from England in September 1929. Although he dearly wanted to visit the Belgian Congo, a country that had always fascinated him, he was not able to obtain a visa during this journey.

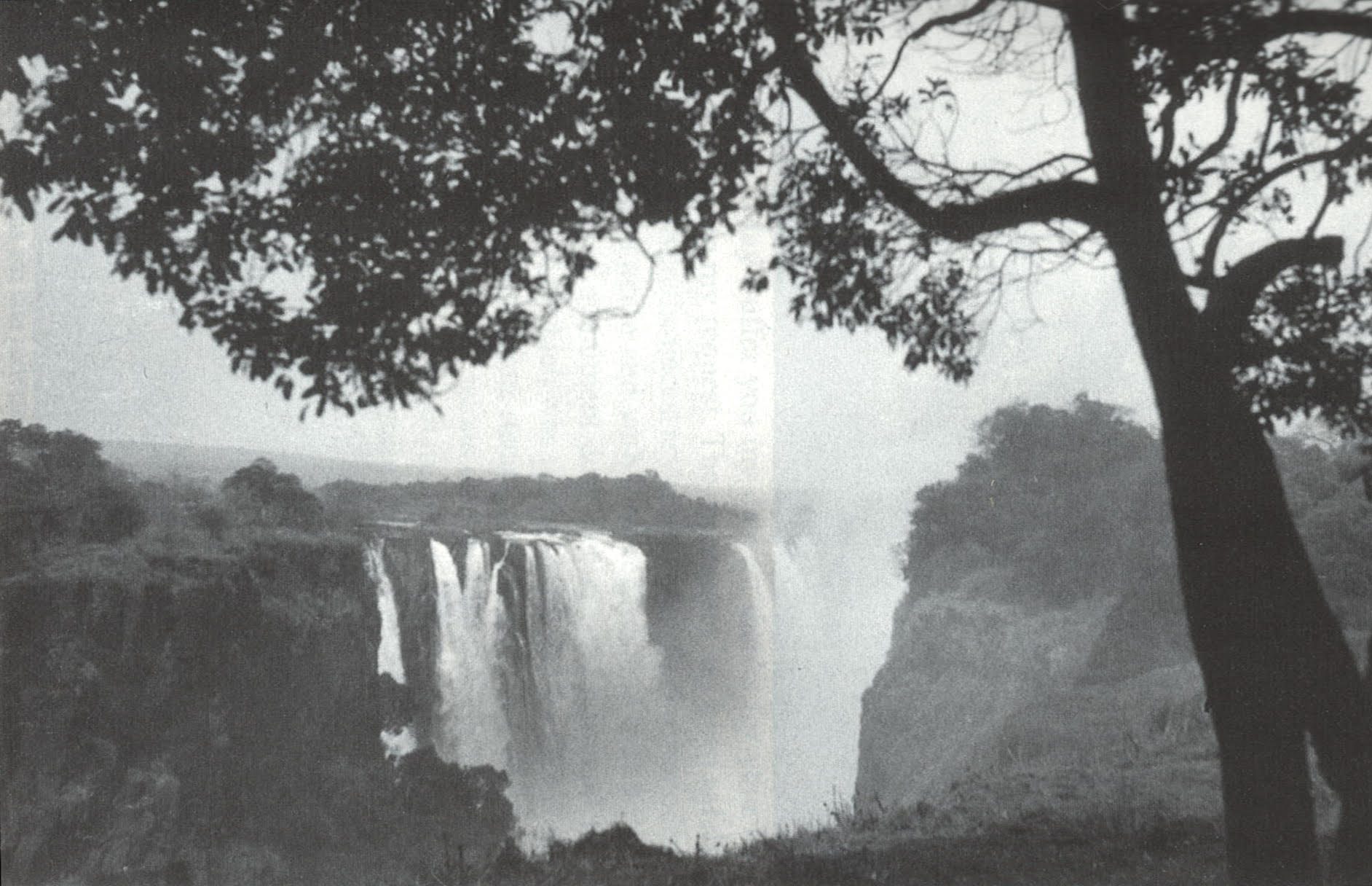

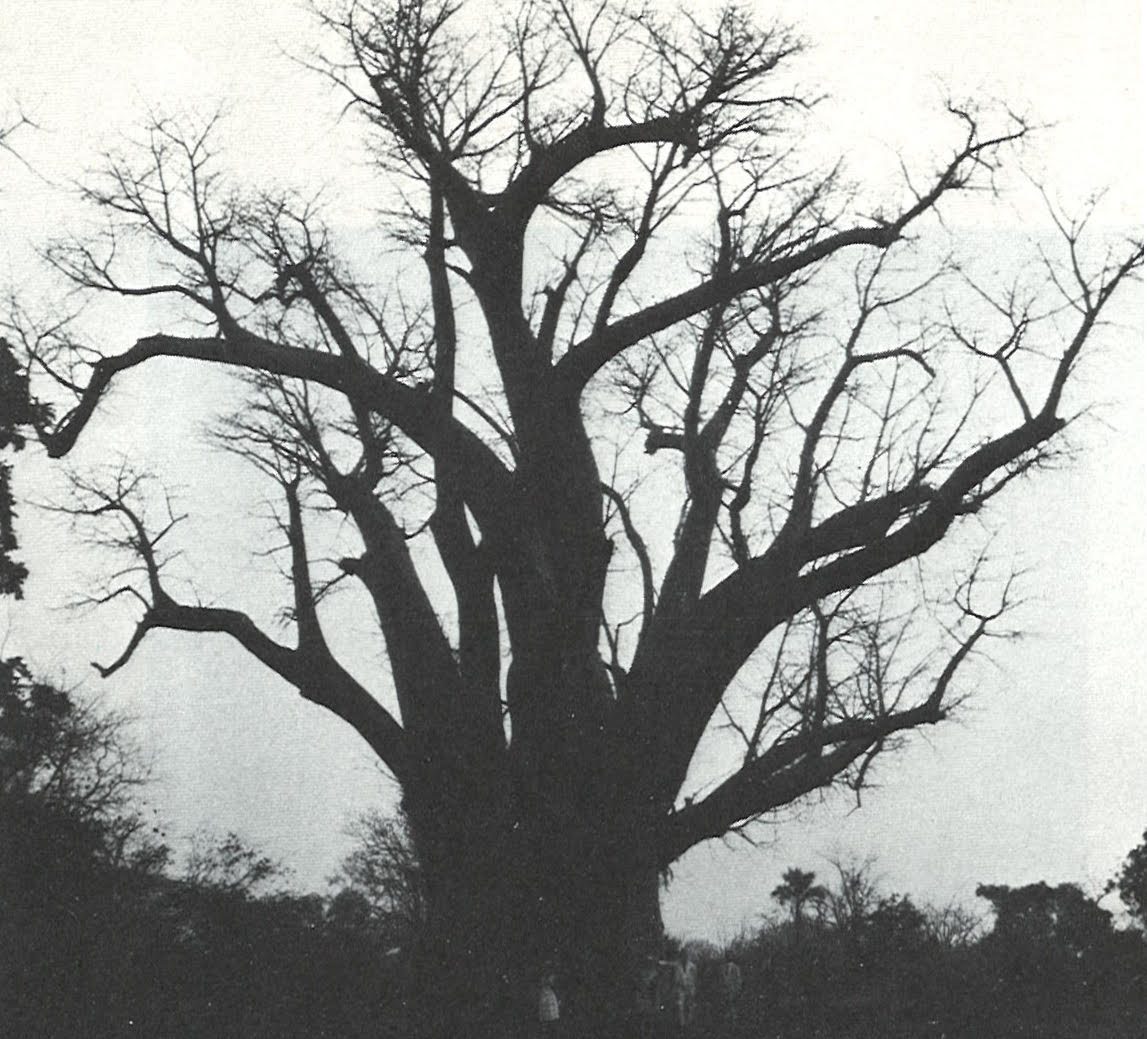

Shoghi Effendi passed through what is today Zimbabwe, visited the grave of Cecil Rhodes at Matopo Hills, then north to Victoria Falls, where Shoghi Effendi took a photograph of a stunning Baobab tree.

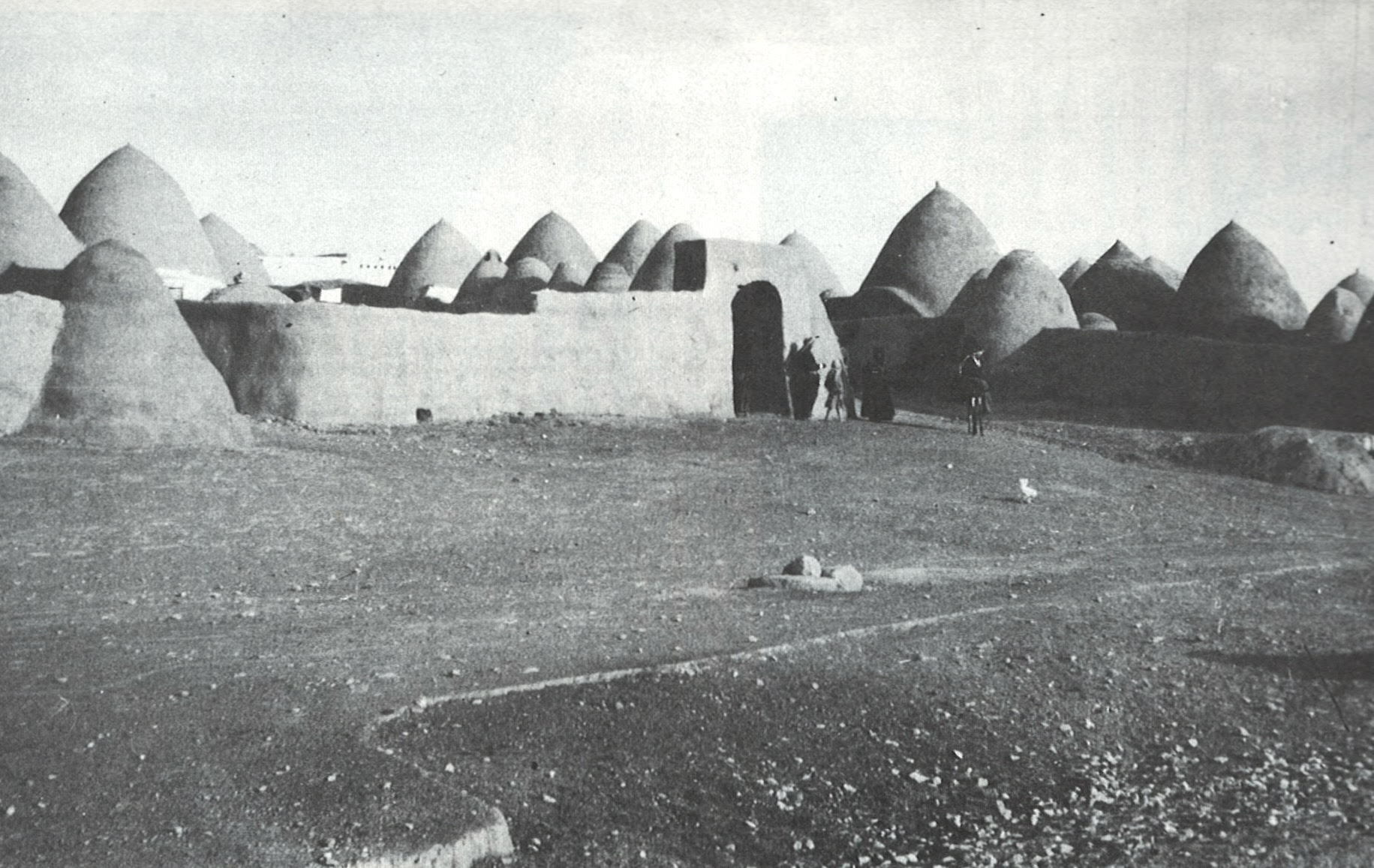

Leaving Zimbabwe, Shoghi Effendi bypassed the Belgian Congo and traveled in a car through East Africa with an English hunter, then rode on a train for 800 kilometers. In the Sudan, Shoghi Effendi rode a ferry on the Nile through a papyrus swamp, and took photographs along the way, making his way to Egypt and arriving back in Haifa in October 1929.

All of the known photographs from Shoghi Effendi's 1929 cross-Africa trip are below in chronological order of his journey.

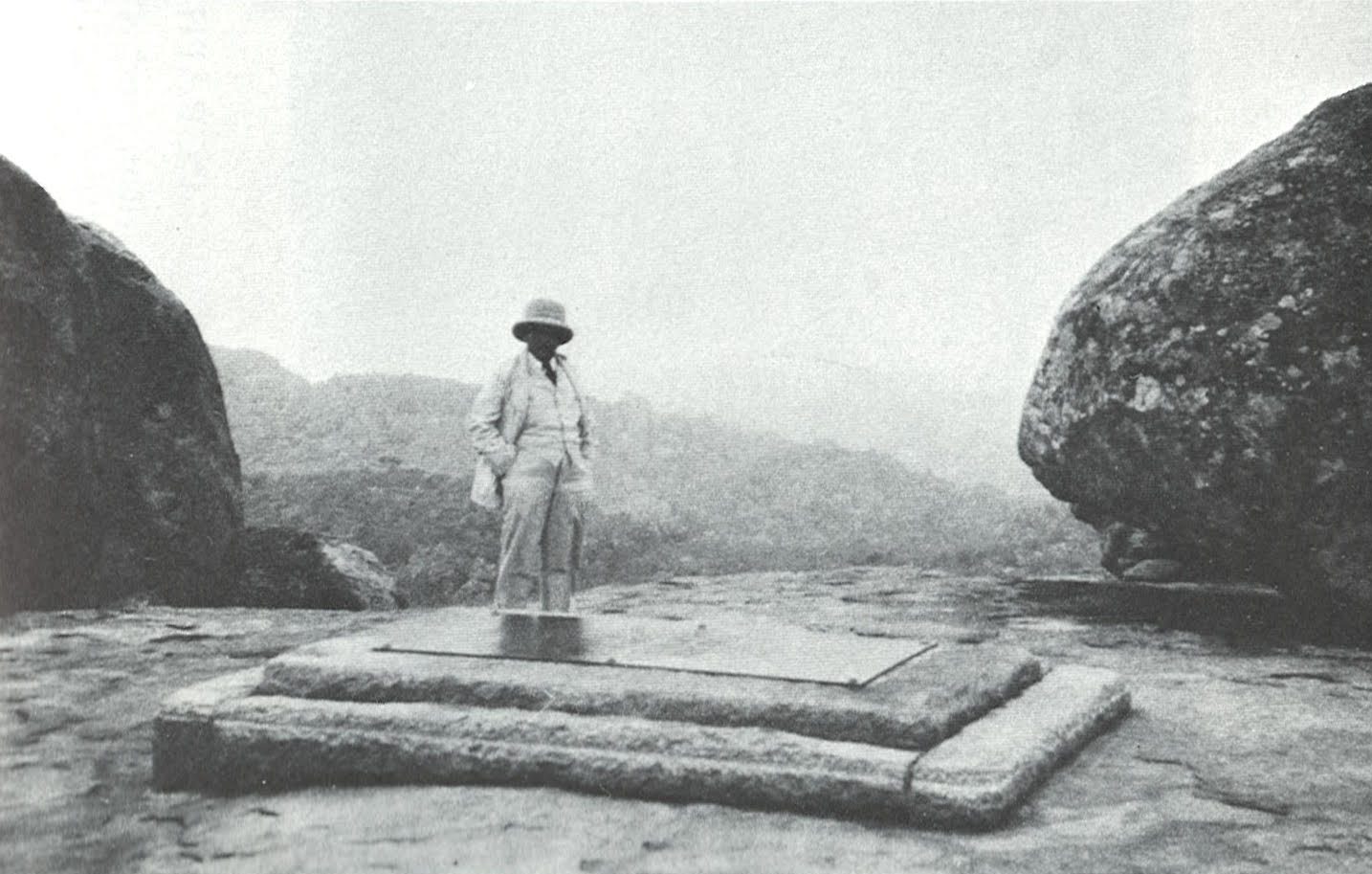

The Guardian standing at the grave of Cecil Rhodes, 1929. Cecil Rhodes was an English colonialist, mining magnate and politician in southern Africa who served as Prime Minister of the Cape Colony. He founded Southern and Northern Rhodesia—named after him and now known as Zimbabwe and Zambia). He also devoted a great deal of effort in building a railway from Cape Town to Cairo Railway and instituted the famous Rhodes Scholarship. Cecil Rhodes was buried at Matopo Hills near Buluwayo, Zimbabwe—then Southern Rhodesia, named after him, and 400 kilometers southeast of Victoria Falls, Shoghi Effendi’s next destination. Source: The Priceless Pearl, between pages 277-278. Scanned and shared by Earl Redman.

Victoria Falls: Shoghi Effendi’s masterly photograph of one of the world’s greatest waterfalls, Zimbabwe, Africa Source: The Priceless Pearl, between pages 277-278. Scanned and shared by Earl Redman.

Baobab tree: Shoghi Effendi’s photograph of the giant baobab trees which grew near Victoria Falls. Source: The Priceless Pearl, between pages 277-278. Scanned and shared by Earl Redman.

Getting the ferry boat through a papyrus swamp on the Nile River, 1929. Photograph by Shoghi Effendi. Source: The Priceless Pearl.

The car in which Shoghi Effendi travelled as a passenger with an English hunter across part of East Africa, 1929 Source: The Priceless Pearl.

Mud Village: A typical beautiful African mud village, taken by Shoghi Effendi when he crossed Africa from Cape Town to Cairo in 1929. This could be in South Sudan, which has these same types of conical mud huts. Source: The Priceless Pearl, between pages 277-278. Scanned and shared by Earl Redman.

A view of the Shrine of the Báb with the three rooms added by Shoghi Effendi, 1939. Source: Bahá'í World News Service.

Shoghi Effendi began his Guardianship knowing that 'Abdu'l-Bahá, although He had only built six, had planned nine rooms in the Shrine of the Báb, and His grandson undertook to complete the work He had started.

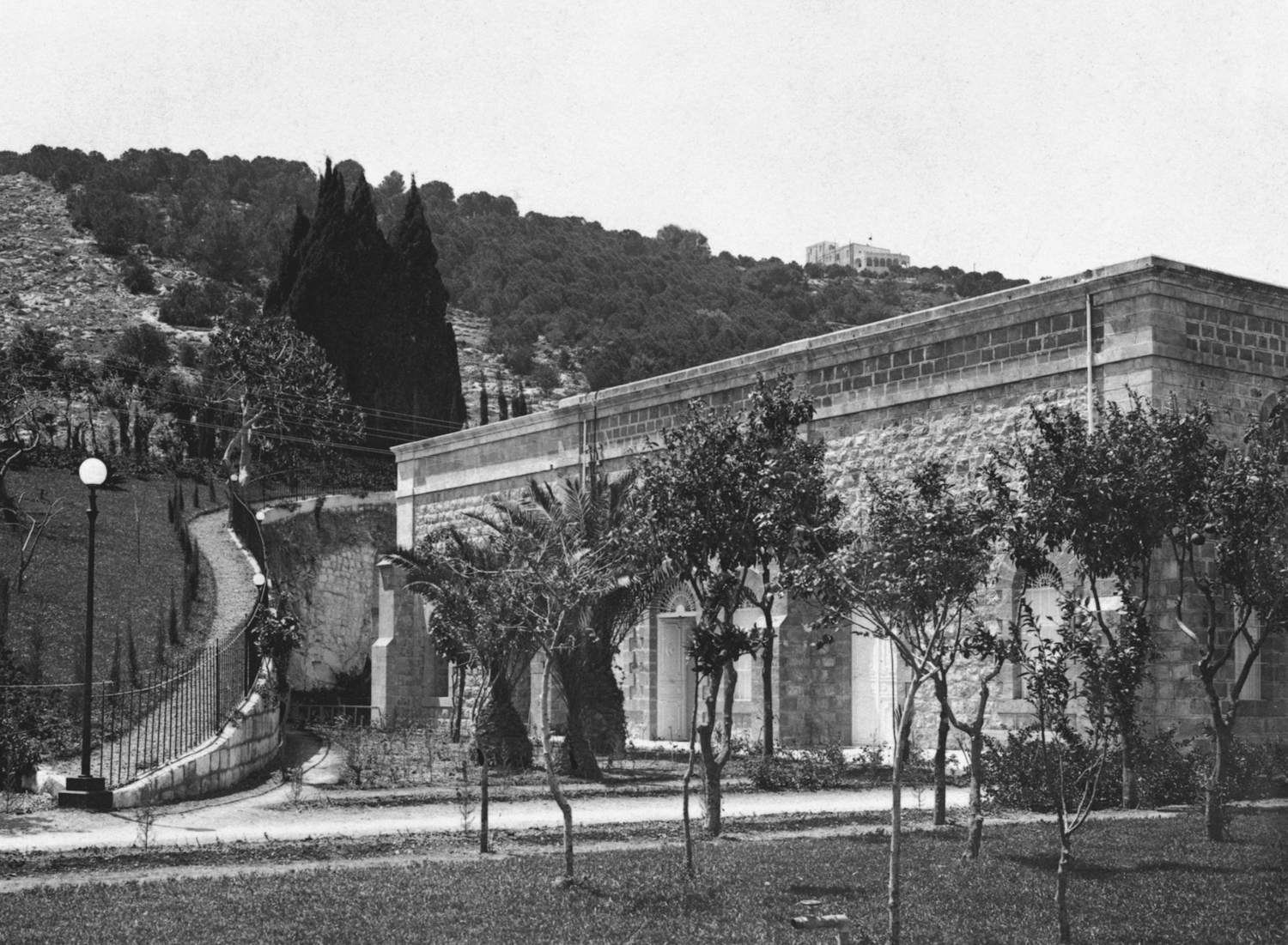

The only real place for the three new rooms of the Shrine of the Báb were on the south side of the Shrine, which would then place the inner sanctuary of the shrine of the Báb in the center of the building. The construction process would be very expensive, because Shoghi Effendi would have to excavate.

Providentially, in 1928, a Bahá’í from Baghdad, Ḥájí Maḥmúd Qassábchí offered to fund the entire project. With the help of a local architect and engineer, Shoghi Effendi designed the plan for the three additional rooms in the Shrine, and he personally supervised the arduous manual excavation of the rock mountain.Actual building work began on 14 February 1929, for a little less than a year, with the rooms being completed by 1930, after Shoghi Effendi had returned from Africa. The beloved Guardian personally supervised the construction work, which required excavation of the mountain-side to make sufficient space for the additional rooms. All the work was accomplished with the use of simple tools and raw manpower, a backbreaking and dangerous enterprise without the help of modern, specialized machinery.

With the Guardian’s addition of the last three rooms, the shape of the original Shrine built by 'Abdu'l-Bahá was changed from an oblong edifice to one perfectly square.

Two photographs of the inside of the very first International Bahá'í Archives on Mount Carmel, in the three rooms Shoghi Effendi finished building in early 1930. Both photographs © United States National Bahá'í Archives, used with permission.

In the three rooms he had just finished building, Shoghi Effendi established the first International Bahá'í Archives. With his own hands, he lovingly gathered and displayed, in orderly arrangements, the relics, the personal objects, photographs and portraits associated with the Central Figures of the Faith. These first Archives would later be known as the major Archives, when a second site would be inaugurated.

Among the items which the pilgrims could marvel at were portraits of the Báb and Bahá’u’lláh, the hair and garments of the Báb and Bahá'u'lláh, Bahá'u'lláh’s pen-case, garments, headdresses, and his alms-bowl (kashkúl) from His two years in Iraqi Kurdistán, priceless manuscripts and Tablets, some illuminated, blood-stained garment of the Purest Branch, the ring of Quddús and the sword of Mullá Husayn,

Visiting the International Bahá'í Archives was a profoundly moving experience which Rúḥíyyih Khánum first experienced in 1937, the year she came on her second pilgrimage to the Holy Land and the year she married Shoghi Effendi. These are her recollections of the early Archives in a room of the Shrine of the Báb and the deep significance of being allowed to gaze upon relics that had touched the person of a Manifestation of God:

If one could have walked into a museum of the authentic relics of the days and life of Christ, what would it have meant to the Christian believers? If they had seen His sandals, dusty from the road between Bethlehem and Jerusalem, or the mantle that hung from His shoulders - or the cloth that protected His head from the sun; what atmosphere of assurance, of wonder, even of adoration would have stirred the inheritors of His Faith. If their eyes could have rested on even one fragmentary line penned by His hand…To most of the people of the world the meaning of such things is beyond their imagining; but to Bahá'ís, believers in the newest Revelation of God's Will as yet revealed to unfolding mankind upon this planet, this inestimable privilege has been vouchsafed.

In the 1930s, Shoghi Effendi began collecting archival manuscripts and photographs from the older generation of believers who had become Bahá'ís during the Heroic Age. He also asked outstanding believers to write their memoirs—as 'Abdu'l-Bahá had done with ‘Ḥájí Mírzá Ḥaydar-‘Alí—and he did this with Bahá'ís of the east and the west. In Persia, Shoghi Effendi asked Bahá'ís to write the Bahá'í memoirs of their cities, and dozens of these were completed for cities like Yazd, Shíráz, Hamadan.

Shoghi Effendi also had another, magnificent project.

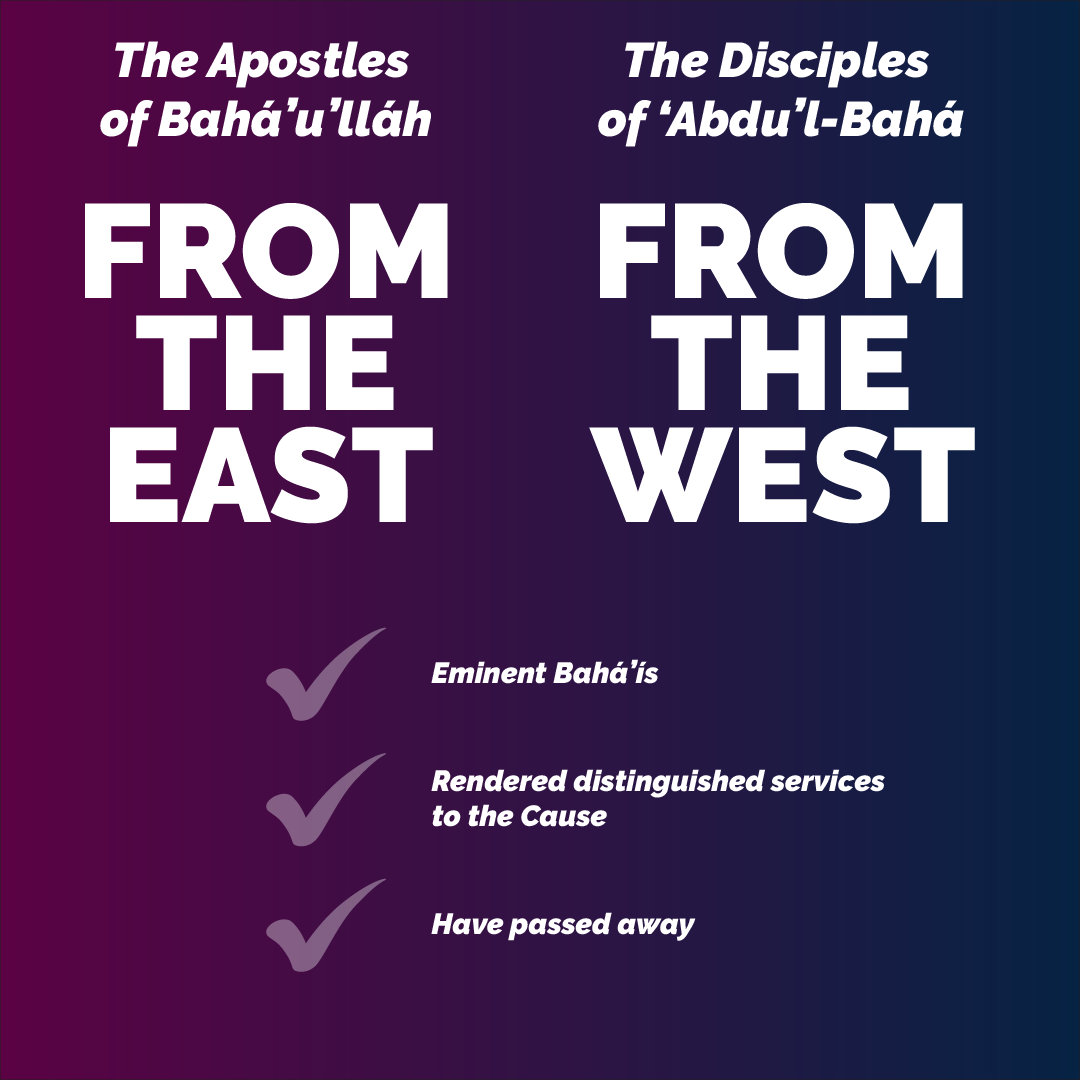

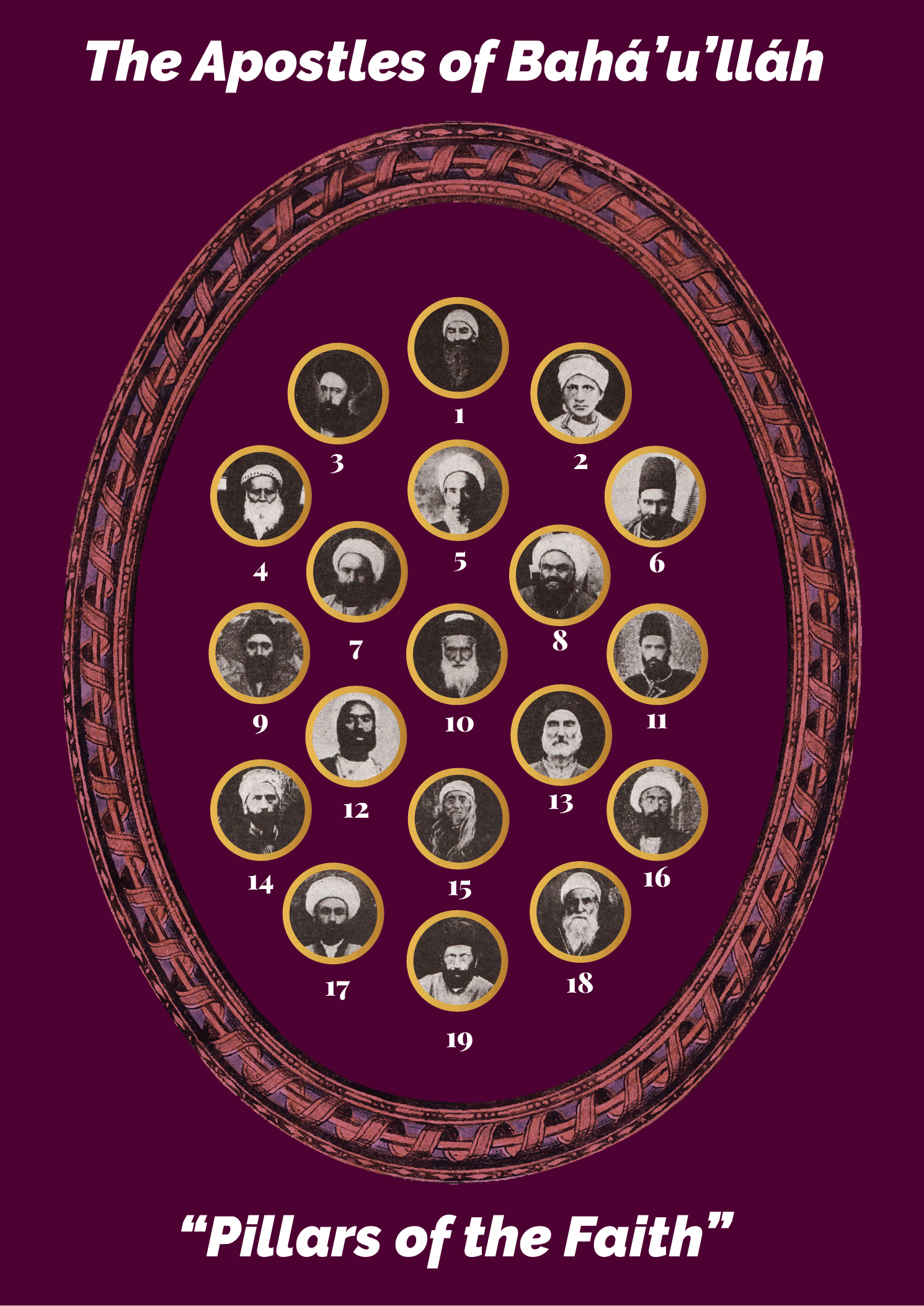

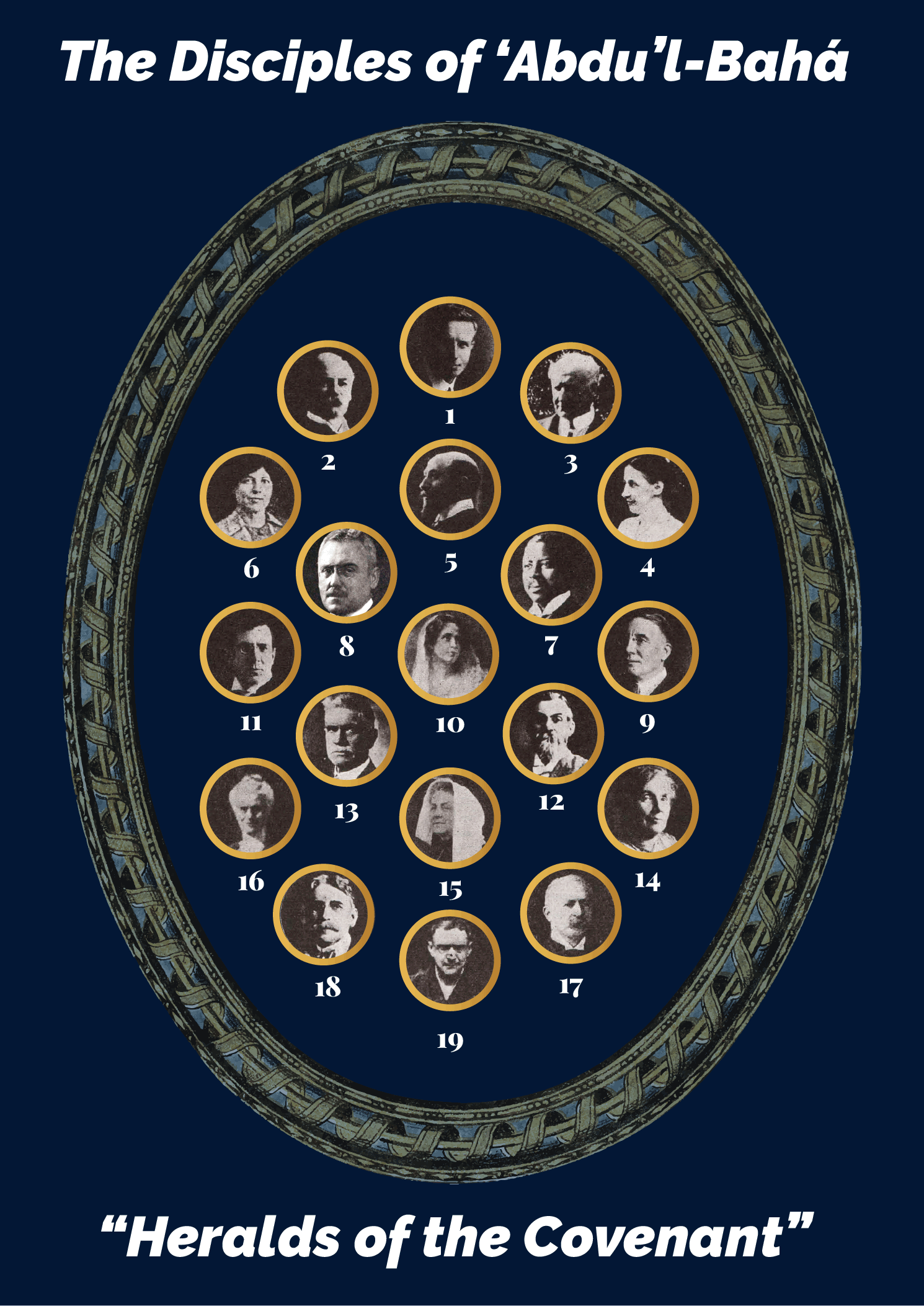

At least a year—if not more—before his letter to May Maxwell, Shoghi Effendi had devised the most elegant and befitting way to honor the heroes and heroines of the ministries of Bahá'u'lláh and 'Abdu'l-Bahá: He would elevate them all to a rank, he would choose 19 of them, and provide their photographs, and insert the two plates in the upcoming volume of The Bahá'í World.

The 19 eminent Bahá'ís from the time of Bahá'u'lláh would be called the Apostles of Bahá'u'lláh—all of them men, and all of them Persian.

The 19 distinguished believers from the ministry of 'Abdu'l-Bahá would be henceforth known as the Disciples of 'Abdu'l-Bahá—men and women, all western.

On 3 February 1930, May Maxwell received a letter from Shoghi Effendi’s describing the project:

Among others [Shoghi Effendi] is collecting the pictures of some of the old friends who have passed away and who have rendered distinguished services to the Cause. He has already gathered the pictures of nineteen distinguished figures among those who have rendered eminent services to the Cause in the East. He wishes now to gather an equal number from among the old western Bahá’ís who have passed away and who have done great services to the Cause.

- Mírzá Músá: the brother of Bahá’u’lláh, 18 month his junior.

- Badíʻ: the 17-year-old who martyred after delivering Bahá'u'lláh’s Tablet to Naṣiri'd-Dín Sháh.

- Siyyid Ḥasan: the “King of Martyrs” who was beheaded with his brother.

- Ḥájí Amín: a.k.a. Mulla Abdu'l-Hasan, the trustee of Ḥuqúqu’lláh. Elevated to the rank of Hand of the Cause by Shoghi Effendi after his passing.

- Mírzá Abu'l-Faḍl: one of the most learned Bahá'í scholar and ardent defender of the Faith of his generation.

- Varqá: the father of Rúhu'lláh. They were martyred together.

- Mírzá Maḥmúd: well-known teacher of the Faith, dedicated to the welfare of the youth.

- Ḥájí Ákhúnd: One of the four Hands of the Cause appointed by Bahá'u'lláh during His lifetime. At 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s orders, he transferred the remains of the Báb from various secret locations to ʻAkká. He was responsible for much of the Bahá’í activity in Persia until his death.

- Nabíl-i-Akbar: one of the most learned men in all of Persia, with the equivalent of two doctorates in philosophy and Islamic law, he attained the rank of mujtahid and was a fearless teacher and recipient of several tablets from Bahá’u’lláh.

- Vakílu'd-Dawlih: a cousin of the Báb and the chief builder of the first Bahá'í House of Worship in ‘Ishqábád, a project initiated by ʻAbdu'l-Bahá in 1902.

- Ibn-i-Abhar: One of the four Hands of the Cause appointed by Bahá'u'lláh during His lifetime. He traveled and taught throughout Persia, the Caucasus, Turkmenistan and India.

- Nabíl-i-Aʻẓam: Poet-Laureate of the Blessed Beauty, eminent teacher of the cause and author of Nabíl’s Narrative.

- Káẓim-i-Samandar: Bahá'u'lláh’s favorite Apostle, extraordinary teacher of the Faith and recipient of the Lawḥ-i-Fu'ád

- Muḥammad Muṣṭafá Baghdádí: he lived in Beirut and assisted all the pilgrims on their way to and from 'Akká; he met some of the Báb's Letters of the Living.

- Mishkín-Qalam: the most noteworthy calligrapher of his time and designer of the Greatest Name.

- Adíb: One of the four Hands of the Cause appointed by Bahá'u'lláh during His lifetime. After the passing of Bahá’u’lláh, he became instrumental in dealing with the activities of Covenant-breakers in Persia; he became of the first National Spiritual Assembly of Persia and also traveled to India and Burma.

- Shaykh Muḥammad-'Alí: the nephew of Nabíl-i-Akbar, he traveled to India and Haifa, and 'Abdu'l-Bahá later sent him to ‘Ishqábád to promote the education of children; he helped complete some of Mírzá 'Abu'l-Faḍl’s unfinished works.

- Zaynu’l-Muqarrabín: a doctor of Islamic law, it was he who asked Bahá'u'lláh questions regarding the Kitáb-i-Aqdas which are published as an appendix called “Questions and Answers” at the end of the Most Holy Book.

- Ibn-i-Aṣdaq: One of the four Hands of the Cause appointed by Bahá'u'lláh during His lifetime. Bahá'u'lláh gave him the title Shahíd Ibn-i-Shahíd (Martyr, son of the Martyr) because he was the son of Mullá Ṣádiq Muqaddas, a martyr from the time of the Báb; he brought the Tablet to the Hague from Haifa to the Netherlands along with Aḥmad Yazdaní.

- John E. Esslemont: author of Bahá'u'lláh and the New Era, Hand of the Cause and secretary of the Guardian.

- Thornton Chase: the first American Bahá'í,

- Howard MacNutt: noted Bahá’í teacher, passionate about editing and publishing Bahá'í books and newsletters.

- Sarah Farmer: Founder of Green Acre.

- Hippolyte Dreyfus-Barney: author, translator, and international promoter of the Faith.

- Lillian Kappes: noted teacher of the Tarbíyaṭ school in Tihrán.

- Robert Turner: first African-American Bahá'í.

- Albert Schwarz: a prominent member of the German Bahá'í community.

- William H. Randall: eloquent upholder of the Bahá’í Cause in America.

- Lua M. Getsinger: titled “Herald of the Covenant” and "Mother of the believers" by 'Abdu'l-Bahá and “mother teacher of the American Bahá‘í Community, herald of the dawn of the Day of the Covenant" by Shoghi Effendi, she was one of the first westerners ever to meet 'Abdu'l-Bahá in 1898,

- Joseph Hannen: an integral member of the Washington Bahá'í community, notable for his efforts to teach the Faith to the African American community.

- Chester I. Thacher: an early Chicago Bahá'í.

- Charles Greenleaf: an active member of the early Chicago Bahá'í community, and cofounder of the entity which eventually became the Bahá'í Publishing Society

- Isabella D. Brittingham: one of the earliest American Bahá'ís, a trusted and energetic teacher of the Faith.

- Ethel Rosenberg: the first English Bahá'í, hosted ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in her home during His visit to England, she served on the first National Spiritual Assembly of the British Isles, briefly served as a secretary for Shoghi Effendi.

- Helen S. Goodall: dearly beloved by 'Abdu'l-Bahá, she accompanied Him often during His travels in America; she helped establish the Bahá'í Faith on the west coast of the United States and in Hawaii, and served on the first national administrative Bahá'í body in the United States.

- Arthur P. Dodge: staunch advocate of the Cause, very active member of the New York City Bahá'í community.

- William H. Hoar: prominent Bahá’í teacher and one of the earliest American Bahá'ís.

- George Jacob Augur: first Bahá'í to pioneer to Japan.

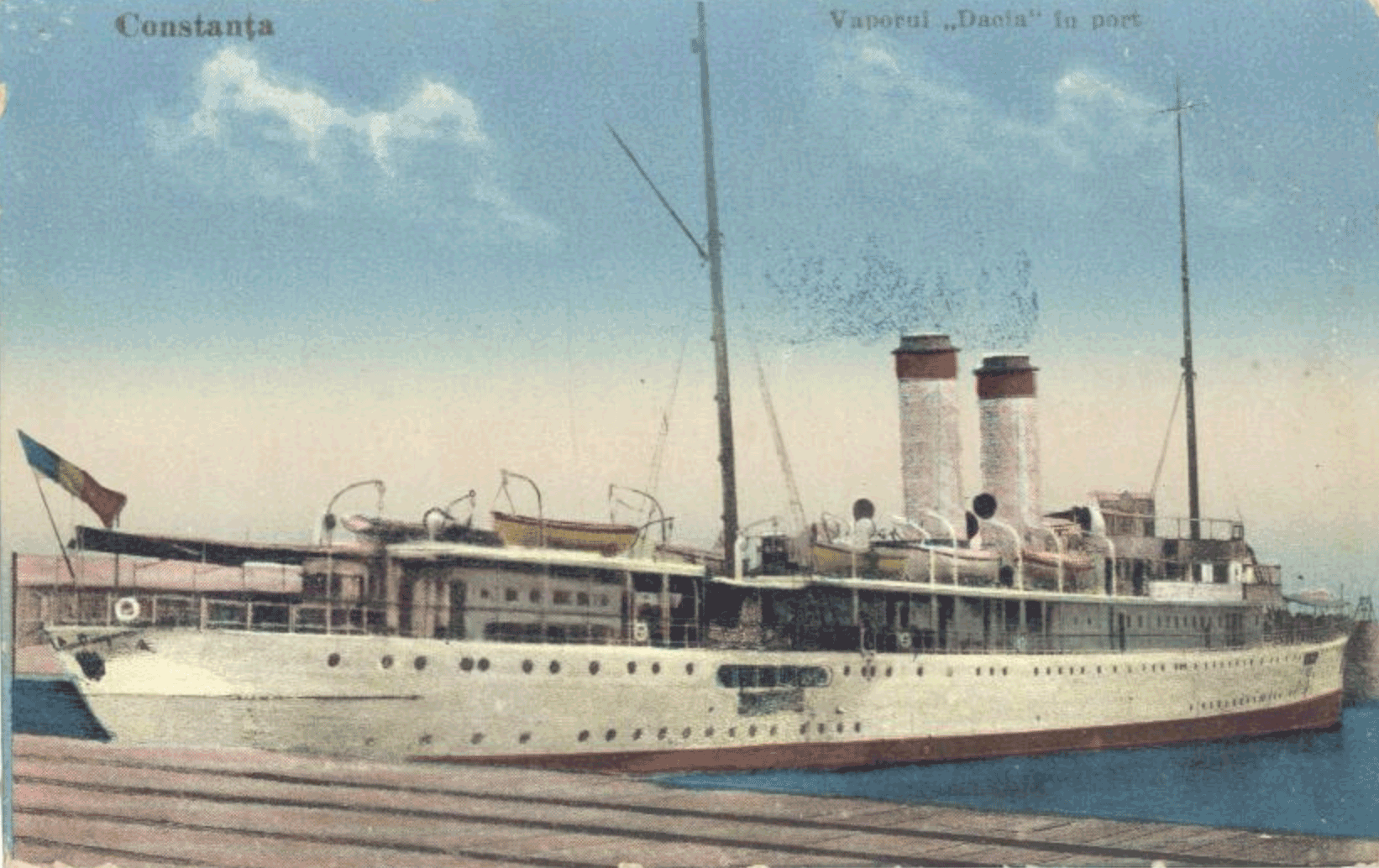

The Dacia, the Imperial Yacht aboard which Queen Marie of Romania sailed to Egypt and to the Holy Land, but was unable to visit Shoghi Effendi and the Greatest Holy Leaf. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

In October 1929, Queen Marie, knowing about her upcoming visit, in spring of 1930, to Egypt and the Middle East, had affirmed to Martha Root:

We shall surely go to Haifa.

Queen Marie of Romania and her daughter Ileana left Romania on the royal yacht, the Dacia, and traveled from Istanbul to Athens, arriving in Alexandria sometime in February 1930.

Both Shoghi Effendi and Bahíyyih Khánum were anxiously awaiting Queen Marie’s visit in March 1930, and Shoghi Effendi began making preparations. He wired the Bahá'ís in Egypt and asked them to only convey written expressions of welcome on behalf of the Bahá'ís and to avoid individual communications.

The Guardian also prepared a priceless gift. He asked the Bahá'ís of Persia to reproduce Bahá'u'lláh’s Tablet to Queen Victoria, Queen Marie’s grandmother in the finest calligraphy, illuminate the Tablet and send it to the Holy Land no later than 10 March 1930.

Shoghi Effendi had not heard from Queen Marie so he sent a cable on 8 March extending a heartfelt invitation on behalf of 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s family to the queen and stated:

Your Majesty's acceptance to visit Bahá'u'lláh's Shrine and prison-city of 'Akká will apart from its historic significance be a source of immeasurable strength joy and hope to the silent sufferers of the Faith throughout the East.

There was no reply.

On 30 March 1930, Queen Marie’s ship docked in Haifa. The Greatest Holy Leaf had waited, hour after hour, in the Master's home to receive Queen Marie and Princess Ileana, and even Shoghi Effendi had hoped the visit and the Queen’s pilgrimage would take place. But time passed and no news came.

In her diary, Queen Marie sheds light on what happened. She had docked in Haifa in the early morning of 20 March. Then, the party had been met at the ship, informed her visit was politically impossible, the Queen was placed in a car and driven to Syria.

Queen Marie was just as heart-broken as Shoghi Effendi and the Greatest Holy Leaf that her visit to Haifa and 'Akká did not take place. One year later, on 28 June 1931, she wrote to Shoghi Effendi and expressed her feelings about the missed visit:

Both Ileana and I were cruelly disappointed at having been prevented going to the holy shrines and of meeting Shoghi Effendi, but at that time were going through a cruel crisis and every movement I made was being turned against me and being politically exploited in an unkind way. It caused me a good deal of suffering and curtailed my liberty most unkindly.

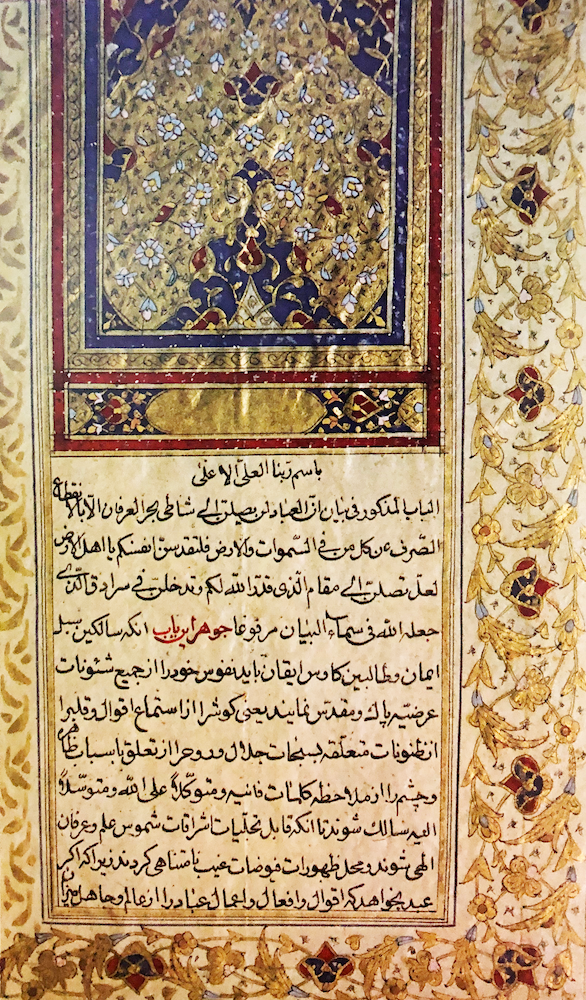

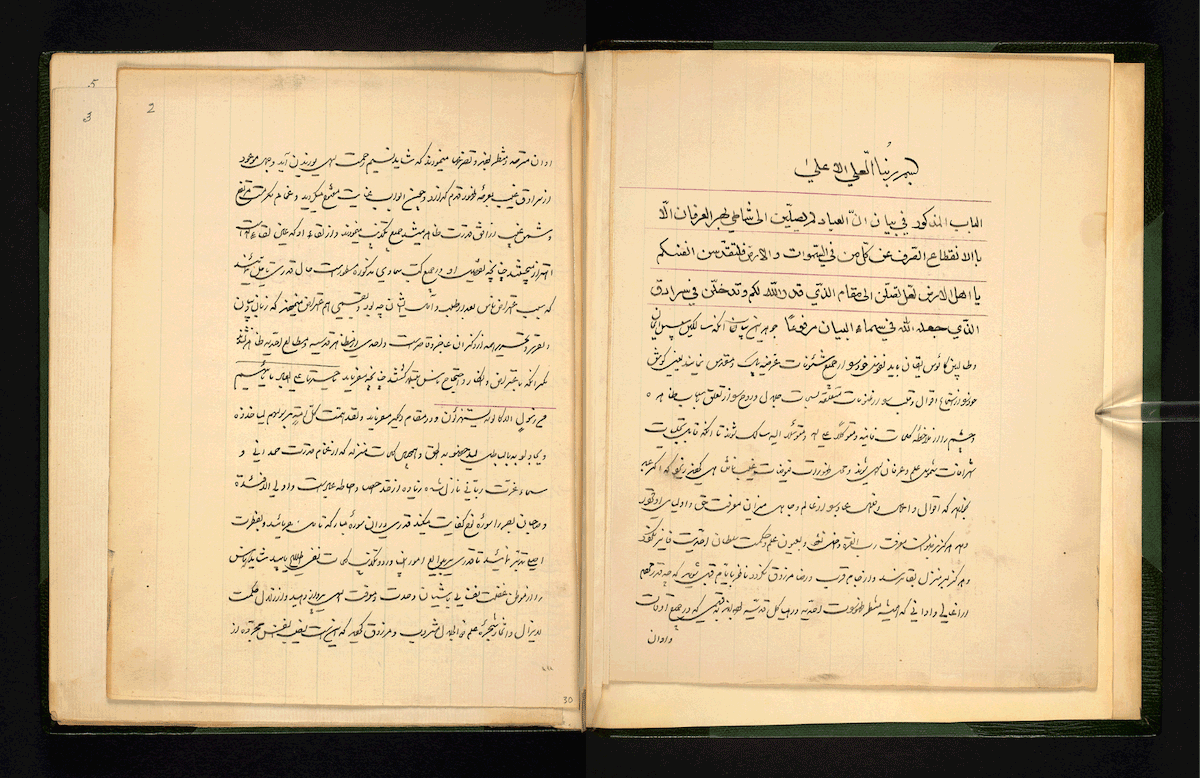

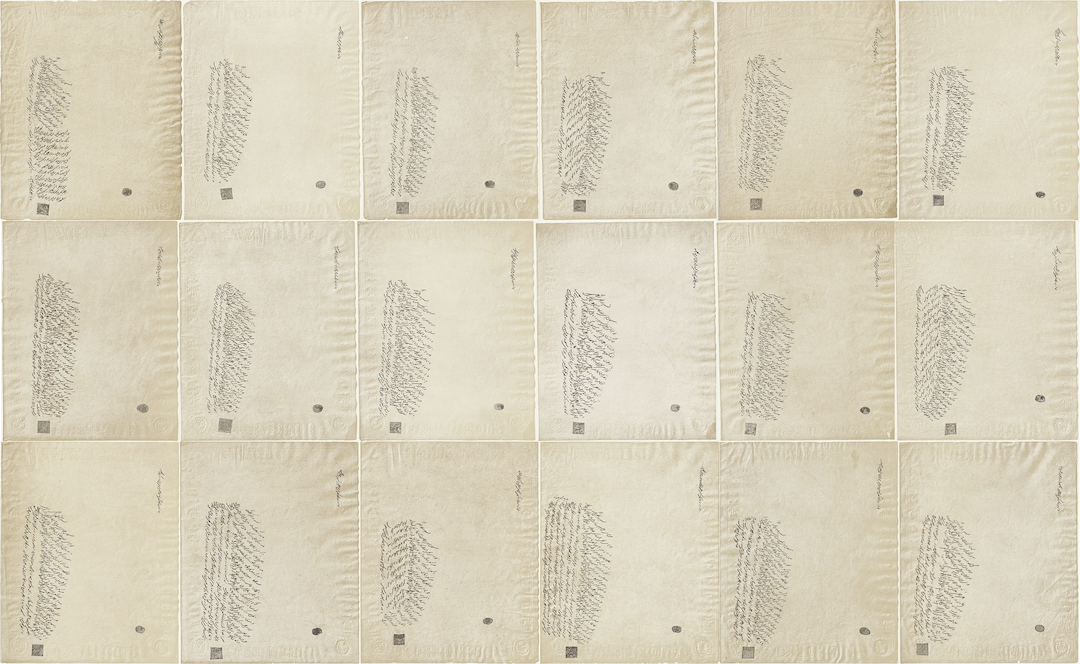

Opening page of the Kitáb-i-Íqán from a manuscript date 1871 in the handwriting of Áqá Mírzá Áqáy-i-Rikáb-Sáz, the first Bahá'í Martyr of Shíráz. Source: Frontispiece of H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory.

In early 1930, the Guardian embarked on his first major, ambitious translation of the Writings of Bahá'u'lláh: the Kitáb-i-Íqán, “foremost among the priceless treasures cast forth from the billowing ocean of Bahá’u’lláh’s Revelation,” a book he later described as a “model of Persian prose, of a style at once original, chaste and vigorous, and remarkably lucid, both cogent in argument and matchless in its irresistible eloquence, this Book, setting forth in outline the Grand Redemptive Scheme of God, [the Kitáb-i-Íqán] occupies a position unequalled by any work in the entire range of Bahá’í literature, except the Kitáb-i-Aqdas, Bahá’u’lláh’s Most Holy Book.” (GPB 138–9).

The Guardian also describes the Kitáb-i-Íqán as “foremost among a “unique repository of inestimable treasures,” possessing an “unsurpassed pre-eminence among the doctrinal” Writings of Bahá’u’lláh.

The Kitáb-i-Íqán (The Book of Certitude) had been the most important book in the early days of the Faith, and it was the source of many eminent Bahá'ís’ conversion to the Faith. Bahá'u'lláh revealed the Kitáb-i-Íqán in January 1861, in the space of 48 hours in Baghdad in response to four questions from the maternal uncle of the Báb, Ḥájí Mírzá Siyyid Muḥammad, who accepted the station of his Nephew, the Báb, when he read the Kitáb-i-Íqán.

The Kitáb-i-Íqán is Bahá'u'lláh’s greatest treatise on the station, the mission, and the role of Manifestations of God, and it would be as useful to Christian seekers in the 20th century as it had been to Muslim ones in the 19th century.

It just needed to be translated into English.

Manuscript of the first two pages of the Kitáb-i-Íqán (unknown calligrapher), copied prior to 1886, when it was purchased by the Austrian orientalist and politician Alfred von Kremer. British Library. Kitab-i Iqan (‘Book of Certitude’), a major Baha’i work by Baha’u’llah.

Shoghi Effendi must have started translating the Kitáb-i-Íqán in 1929, because he had finished the first pages by January 1930, and sent them to George Townshend for review. By 12 March 1930, George Townshend had the entire Kitáb-i-Íqán.

Shoghi Effendi had included words in parentheses in the manuscripts he had sent George Townshend, asking him to choose the most suitable alternative.

The Guardian’s translation of the Kitáb-i-Íqán, like all his translations, was a marvel of meticulous attention paid to every single word. This short excerpt of a letter Shoghi Effendi’s secretary wrote to George Townshend on 19 January 1930 shows how much thought was put into the translation of a single word:

He would like to draw your attention to the word “tribulation” on page 9. Bahá’u’lláh is quoting the famous words of Jesus recorded in Matthew 24:29–31, “Immediately after the tribulation of those days shall the sun be darkened…” etc. The Authorized Version reads “tribulation” whereas the Arabic, from which Bahá’u’lláh is quoting, gives “narrowness.” As there is a difference, Shoghi Effendi would like you please to find out what the original in Greek or Hebrew is. If you think proper he would welcome such alterations from you which would make the language of the rendering more Biblical as he thinks it preferable.

George Townshend’s response to the Guardian’s request was equally meticulous. It turned out that the original Greek word used in the Bible was the word “Thlipsis” which has two meanings: pressure or oppression/affliction.

Upon receiving this information, Shoghi Effendi changed the word “tribulation” to “oppression” which rendered the text: “Immediately after the oppression of those days shall the sun be darkened…”

Shoghi Effendi included a note for the word oppression which read:

“The Greek word used (Thlipsis) has two meanings: pressure and oppression.

When he sent the manuscript of the Kitáb-i-Íqán to the United States, Shoghi Effendi wrote an explanatory note:

Unable to find a good typist, I have had to do the work myself, and I trust that the proofreaders will find it easy to go over and will not mind the type errors which I have tried to correct. I would especially urge you to adhere to the transliteration which I have adopted. The correct title is, I feel, "The Kitab-i-Íqán" the sub-title "The Book of Certitude. “May it help the friends to approach a step further, and obtain a clearer idea of the fundamental teachings set forth by Baha'u'llah.

“Transformation.” Original image: Photo by Alan Scales on Unsplash.

The Guardian’s translation of the Kitáb-i-Íqán stands alone as a work of unsurpassed beauty in the English language. And yet, Shoghi Effendi felt impelled to place a note immediately before his own translation, as if to pay a public homage to the untranslatable perfection of Bahá'u'lláh’s original Persian:

This is one more attempt to introduce to the West, in language however inadequate, this book of unsurpassed pre-eminence among the writings of the Author of the Bahá’í Revelation. The hope is that it may assist others in their efforts to approach what must always be regarded as the unattainable goal—a befitting rendering of Bahá’u’lláh’s matchless utterance.

The Kitáb-i-Íqán is filled with peerless, exquisite sentences, but this excerpt inward and outward transformation, on the goal of all divine Revelations is simply without equal for its straightforwardness, its eloquence and its unimpeachable, divine logic:

Behold, how, notwithstanding these and similar traditions, they idly contend that the laws formerly revealed must in no wise be altered. And yet, is not the object of every Revelation to effect a transformation in the whole character of mankind, a transformation that shall manifest itself, both outwardly and inwardly, that shall affect both its inner life and external conditions? For if the character of mankind be not changed, the futility of God’s universal Manifestation would be apparent.

Two views of the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh at Bahjí at night around 1930. Source: The Bahá'í World Volume 4, page 5.

This story is meant to convey the atmosphere of sanctity that Holy Day commemorations had during the ministry of the Guardian. Every year, these holy days were celebrated, but this vignette serves as a universal description of what it was like to live through the commemoration of the Ascension of Bahá'u'lláh in his presence.

There were so many pilgrims present on the night of 28 May 1930, that groups of Bahá'ís had to take turns entering the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh. The outer chamber of the Shrine was brilliantly illumined, its large cut-glass chandeliers sparkling with the flames of its countless candles, shedding their flickering light on the delicate rug and velvet drapes.

The blue sky was still visible through the glass windows at the top of the Shrine’s outer chamber, their electric lamps, bringing out the relief of the color and texture of the many plants in the central atrium, paved with the small, perfectly round Galilee Sea pebbles.

The Guardian entered first, knelt before the inner Shrine, and retreated to the outer chamber after a few moments.

The Bahá'ís paying their respect at the Holy Threshold moved silently and reverently in an atmosphere devoid of somberness, but filled with a regenerating spirit. Some of the Bahá'ís present on this day had lived in the time of Bahá'u'lláh, entered His presence, gazed upon His face, and they wept with their memories, silently, filling the Shrine with their sense of loss and inexpressible longing.

The believers, one by one, knelt in silent reverence at the Holy Threshold before the inner Shrine, directly above the vault in which Bahá'u'lláh’s sacred remains lay. The Holy of Holies was adorned with soft green velvet draperies and exquisite Persian rugs, beautiful urns overflowing with flowers shedding their fragrance, and delicately lit with a lamp and candelabra.

After the believers had paid their respects, the Guardian chanted the Tablet of Visitation, and the Bahá'ís exited the Shrine, resuming their devotions in the Ḥaram-i-Aqdas, the beautiful garden surrounding the Most Holy Shrine.

Throughout the night, Bahá'ís entered the Shrine to pay their respects, pray, and leave to make room for the next group of friends.

At 3:00 AM on 29 May 1892, the Guardian again entered the Shrine and chanted the Tablet of Visitation, his sweet, melodious voice penetrating the hearts of all those who were present. When the last of the Bahá'ís exited the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh, the first streaks of dawn were lighting the sky, and the first sound they heard was the song of a bird.

One hour later, at 4:00 AM, the Bahá'ís began their journey back to Haifa.

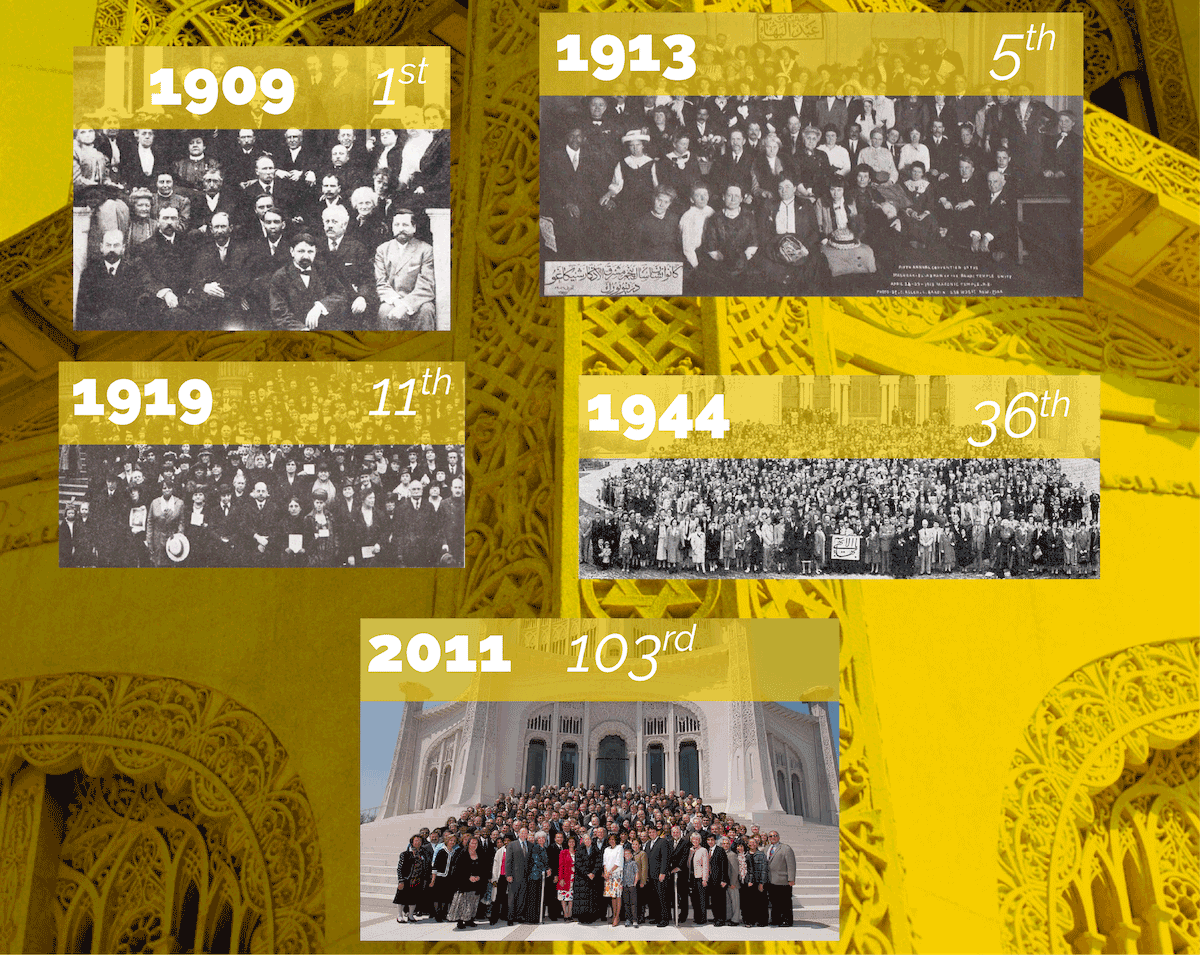

Photographs of the 1st, 5th, 11th, 36th, and 103rd National Conventions of the United States. Source: Bahaimedia. Background: Detail of the ornamental features of the Continental Bahá’í House of Worship of North America (Wilmette, United States), 1988. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

One of the Guardian’s strongest characteristics was his genius for organizing, and Rúḥíyyih Khánum estimates this quality was divinely created in him to fulfill the needs of the Formative Age of the Faith, the development of the Administrative Order, and in particular, how quickly and carefully Shoghi Effendi devised a uniform system of National and Local Spiritual Assemblies throughout the entire world. He was a true statesman.

The Guardian explained to the Bahá'ís at the start of his ministry, that this Administrative Order was unique in religious history, different from any system of religious administration, and that, what they were building would evolve to eventually "at once incarnate, safeguard and foster" the spirit of this invincible Faith and become a World Bahá'í Commonwealth. The system created by Bahá'u'lláh was therefore divine in origin, inaugurated by 'Abdu'l-Bahá, and implemented by Shoghi Effendi would, as the Guardian stated, never “degenerate into any form of despotism, of oligarchy, or of demagogy which must sooner or later corrupt the machinery of all man-made and essentially defective political institutions," in fact, as Shoghi Effendi stated, it was an Administrative Order completely “supernatural, supranational, entirely non-political, non-partisan, and diametrically opposed to any policy or school of thought that seeks to exalt any particular race, class or nation. It is free from any form of ecclesiasticism, has neither priesthood nor rituals, and is supported exclusively by voluntary contributions made by its avowed adherents."

This work would define the next 36 years of his Guardianship, but began in the first year of his ministry, when he encouraged the election of a National Spiritual Assembly in the United States and Canada after a National Convention where 65 localities in North America were present.

Original photo by Erol Ahmed on Unsplash.

By 1930, there were 9 National Spiritual Assemblies in the Caucasus, Persia and Turkistan—these three could not hold National Conventions at first—and Egypt, Great Britain, Germany, India and Burma, Iraq, and the United States and Canada.

In terms of developing the local administration of the Faith, already on 4 April 1923, Shoghi Effendi had sent a cable to the National Spiritual Assembly of the United States and Canada Bahá'ís stating:

"strongly urge re-election all local Assemblies first Riḍván April 21.

This personal attention to the development of a uniform Administrative Order, this personal encouragement from the Guardian to individual National Spiritual Assemblies regarding the importance of the development of Local Assemblies went out to the entire Bahá'í world.