Written and illustrated by Violetta Zein

This part covers the life of Shoghi Effendi from the age of 28 in 1925 to the age of 30 in 1927.

The Most Great House of Bahá'u'lláh in Baghdad. Source: H-Net.

On 16 January 1925, Shoghi Effendi reported that the Shí’ah had first taken the case of the Most Great House of Bahá’u’lláh in Baghdad to their religious court. The case was sent to the Peace Court, then brought before the local Court of First Instance, which decided in favor of the rights of the Bahá'ís.

In November 1925, the decision of the local Court of First Instance was taken to the Court of Appeals, the Supreme Court of Iraq, which gave its verdict in favor of the Shí’ah and therefore decided against the Bahá'ís in the dispute over the Most Great House of Bahá'u'lláh in Baghdád.

On 2 November 1925, Shoghi Effendi sent a distressing cable:

Iraq's Supreme Court unexpectedly pronounced verdict against us in Baghdad case strongly advise national and every Local Assembly communicate by cable and letter with Iraq High Commissioner appealing ardently for action to ensure the security of Baha'u'llah's Sacred House.

Four days later, on 6 November, Shoghi Effendi wrote a letter to the Bahá'ís of the world:

The sad and sudden crisis that has arisen in connexion with the ownership of Bahá'u'lláh's sacred house in Baghdád has sent a thrill of indignation and dismay throughout the whole of the Bahá'í world. Houses that have been occupied by Bahá'u'lláh for well-nigh the whole period of His exile in Iraq, ordained by Him as the chosen and sanctified object of Bahá'í pilgrimage in future, magnified and extolled in countless Tablets and Epistles as the sacred centre "round which shall circle all peoples and kindreds of the earth”—lie now, due to fierce intrigue and ceaseless fanatical opposition, at the mercy of the declared enemies of the Cause.

I have instantly communicated with every Bahá'í Centre in both East and West, and urgently requested the faithful followers of the Faith in every land to protest vehemently against this glaring perversion of justice, to assert firmly and courteously the spiritual rights of the Bahá'í community to the ownership of this venerated house, to plead for British fairness and justice, and to pledge their unswerving determination to ensure the security of this hallowed spot.

One of his first acts, on receiving the news of the decision of the Supreme Court, was to cable the High Commissioner in Baghdad that:

The Bahá'ís the world over view with surprise and consternation the Court's unexpected verdict regarding the ownership of Bahá'u'lláh's Sacred House. Mindful of their longstanding and continuous occupation of this property they refuse to believe that Your Excellency will ever countenance such manifest injustice. They solemnly pledge themselves to stand resolutely for the protection of their rights.

They appeal to the high sense of honour and justice which they firmly believe animates your Administration. In the name of the family of Sir 'Abdu'l-Bahá 'Abbas and the whole Bahá'í Community, Shoghi Rabbani.

On the same day he cabled the heart-broken custodian of Bahá'u'lláh's House:

Grieve not. Case in God's hand. Rest assured.

The Guardian immediately showed his brilliant strategic side and roused the Bahá'í world to unite in action, and sent 19 cables to national communities from Europe and America to Persia and Central Asia, to the Pacific and South-East Asia, instructing the Bahá'ís to protest this decision with the British High Commissioner in Iraq.

On 13 December 1925, the keys of the Most Great House were given to the Shí’ah. The next day, Shoghi Effendi wrote:

We received last night news that the keys of the houses in Baghdád have been given to the Shi'ites and they had made a regular demonstration on the occasion. We await to see what will be done at last

Shoghi Effendi informed the Bahá'í community that the situation was perilous, warned them that it carried "consequences of the utmost gravity” and required “prompt action to safeguard spiritual claims of Bahá'ís to this dearly-beloved Spot.” In a period of six months, Shoghi Effendi wrote nearly 600 letters and hundreds of cables, informing believers and national communities of the language they should use, specific turns of phrases to include, and not to send messages that were identical in wording.

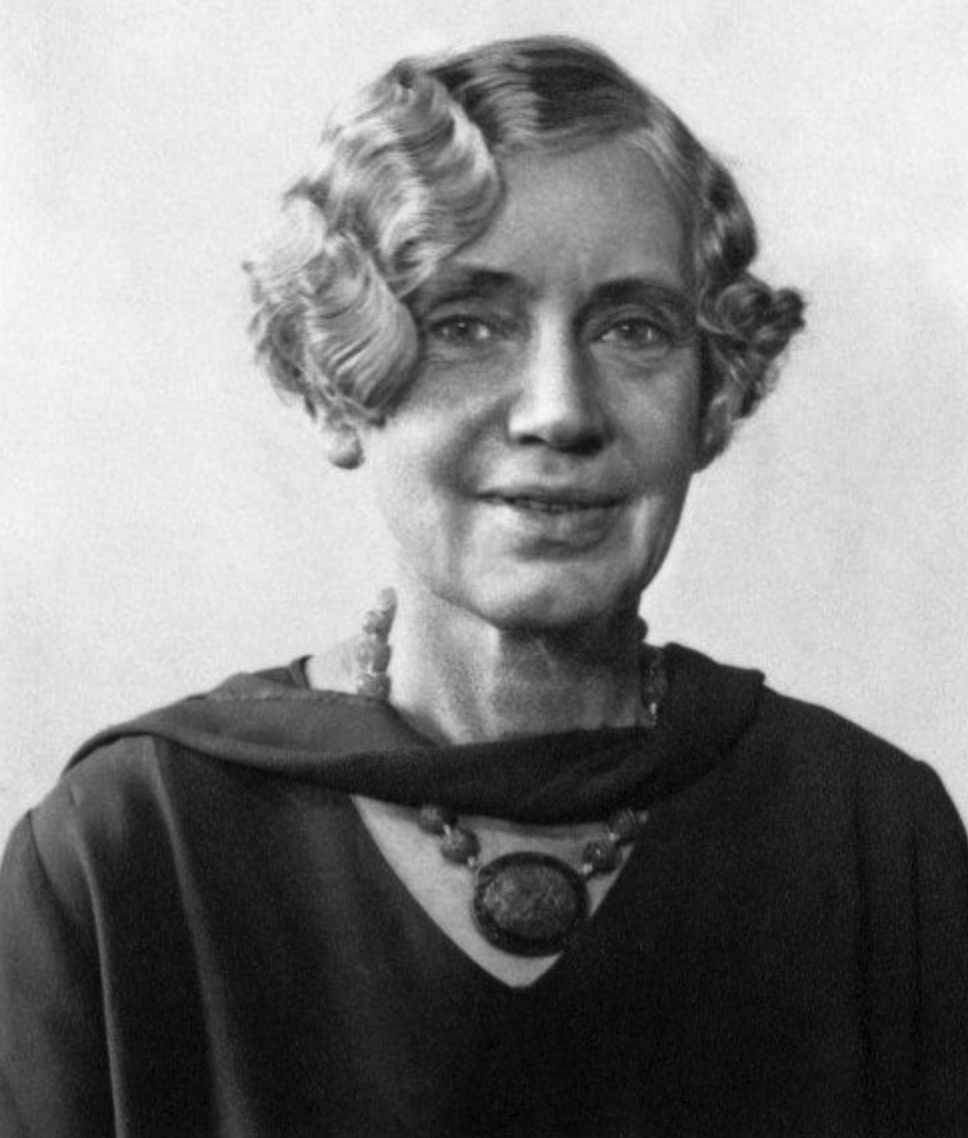

Effie Baker. Frontispiece of her biography, Ambassador at the Court: The Life and Photography of Effie Baker by Graham Hassall.

Euphemia “Effie” Baker, the second Australian Bahá'í and a professional photographer, returned to Haifa in August 1925, after six months in England following her fist pilgrimage of January 1925. This time, Effie Baker only intended to stay for a few weeks, and had made arrangements to leave on the next steamer to Port Said, Egypt, leaving at the end of August. But when she arrived in Haifa, Shoghi Effendi was absent from the Holy Land and she found Saichiro Fujita and Jináb-i-Fádil-i-Mazandarání, his wife Ḍíyá‘íyyih and two children had come down with influenza, and she began caring for them.

The ladies of the Holy Family asked Effie to extend her stay until Shoghi Effendi returned, and Ḍíyá‘íyyih Khánum—Shoghi Effendi’s mother—asked directly if she could stay in the Holy Land with them indefinitely, and informed her they wanted Effie to accompany the girls to England when they resumed their university studies. Effie Baker did such a marvelous job caring for the sick Bahá'ís that Ḍíyá‘íyyih Khánum would later say she had at long last found a Mother for the Western Pilgrim House. But Effie knew serving at the World Center would be difficult, as she told Hyde and Clara Dunn in a letter:

I can see that life here will not be easy and perhaps I have come here to learn the lesson of detachment. I am up at a little after five every morning and it is generally ten o'clock before I get to bed.

Effie Baker stayed in Haifa for a few weeks, unsure of her immediate plans. When Shoghi Effendi returned to the Holy Land on 15 October 1925, he suggested it would be best for Effie Baker to return to Australia and helped Hyde and Clara Dunn spread the Faith. Effie was disappointed, she wanted to stay in Haifa, but she booked passage on the S.S. Esperance Bay, due to sail from Haifa on 21 January 1926, and reconciled herself with leaving the Holy Land, and making the most of the last few weeks she had left. Then, a couple of days before her departure, Shoghi Effendi took Effie Baker on her last visit to the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh, and on the drive back he told her:

You know Effie, a general always sends his good soldiers afar, he keeps the bad ones always under his eye

The next afternoon, Effie Baker was walking up the single terrace to visit the Shrine of the Báb, when she met Shoghi Effendi, who was coming down Mount Carmel, accompanied by eastern pilgrims. He told the pilgrims to wait for him, and continued stepping down to speak to Effie, saying:

Effie I've reconsidered my decision. I'm going to keep you here.

Effie Baker said:

Oh! Shoghi Effendi I am evidently one of the bad soldiers you told me about yesterday!”

Shoghi Effendi and Effie Baker shared a laugh at her quip. The Guardian had no doubt been impressed by Effie Baker’s endearing and impressive qualities, and no doubt she had received glowing reviews from the women of the Holy Family. Later, Shoghi Effendi would describe Effie in a letter to the Dunns as a “beloved and devoted sister,” and an evidence of their “diligent and heroic pioneer work in that vast continent” whom he had been “so glad to welcome in Haifa.”

The Western Pilgrim House. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

When Effie Baker began to serve as hostess of the Western Pilgrim House, there were three pilgrim houses in Haifa: the Western Pilgrim House and the Pilgrim House for eastern women, across the street from the House of 'Abdu'l-Bahá where Shoghi Effendi lived, and the Eastern Pilgrim House, close to the Shrine of the Báb on Mount Carmel.

When the Western Pilgrim House was finally built and ready for use in the first half of 1926, Effie’s first duties were to make it habitable. Electricity was installed at the end of September 1926, and this made Effie’s life much easier, because she no longer needed to constantly clean kerosene lamps. The Australian Bahá'ís contributed £17 for the purchase of a new sewing machine. By 1927, the Guardian had added an additional 8 rooms to the Western Pilgrim House, and Saichiro Fujita and Effie Baker carried many bricks to help with the building.

There were, of course, others assisting Shoghi Effendi maintain the buildings and grounds of the Bahá'í holy places in Haifa and 'Akká during Effie’s years there, although she seems to have been the only resident Westerner (apart from Dr Esslemont, whose story is told below).

The other caretakers at the time were Yahdu’lláh who was Turkish but from the Persian village of Saysán, who was the caretaker of the Garden of Riḍván and Bahjí. He was assisted at the Riḍván garden by his sons Isfandíyár and Farud. The sons of Abul-Qasím Khurásání, became the caretakers of the gardens and the Archives on Mount Carmel.

Effie Baker suffered from the heat in the Holy Land, but any hardships that Effie endured living in Haifa were more than compensated for by the privilege of being in the presence the Greatest Holy Leaf, the saintly daughter of Bahá'u'lláh. The Greatest Holy Leaf would teach Effie Baker so much about life: forgiveness, acceptance without complaint, patience, and radiant acquiescence.

When she saw light in Shoghi Effendi’s office, Effie Baker tried an experiment: she attempted to stay up as long as his light was on, to go to bed at the same time as him. She tried for several evenings, and every night, fell asleep before Shoghi Effendi’s desk lamp turned off.

Food was always cooked at the Master's house. Saichiro Fujita carried it to the Western Pilgrim House and an Arab youth kept it hot on a blue-flame stove. It was then Effie’s job to inform Shoghi Effendi that the food was ready, the pilgrims were present, and dinner could begin.

During her service at the World Center, Effie Baker wrote very long circular letters to the Australian Bahá'í community, with the Guardian’s permission. Here are a few sentences from a letter dated 23 December 1925:

Yesterday I was able to have a talk with our Beloved Guardian and he wishes me to impress upon you that it is very necessary that each assembly and their group should consult with one another upon this matter thoroughly and after consultation if the majority decide as to its formation the minority should cheerfully abide by the majority's decision and be willing to give its whole-hearted and cheerful support. If this were not so then inharmony and discord would arise and progress of the Cause arrested.

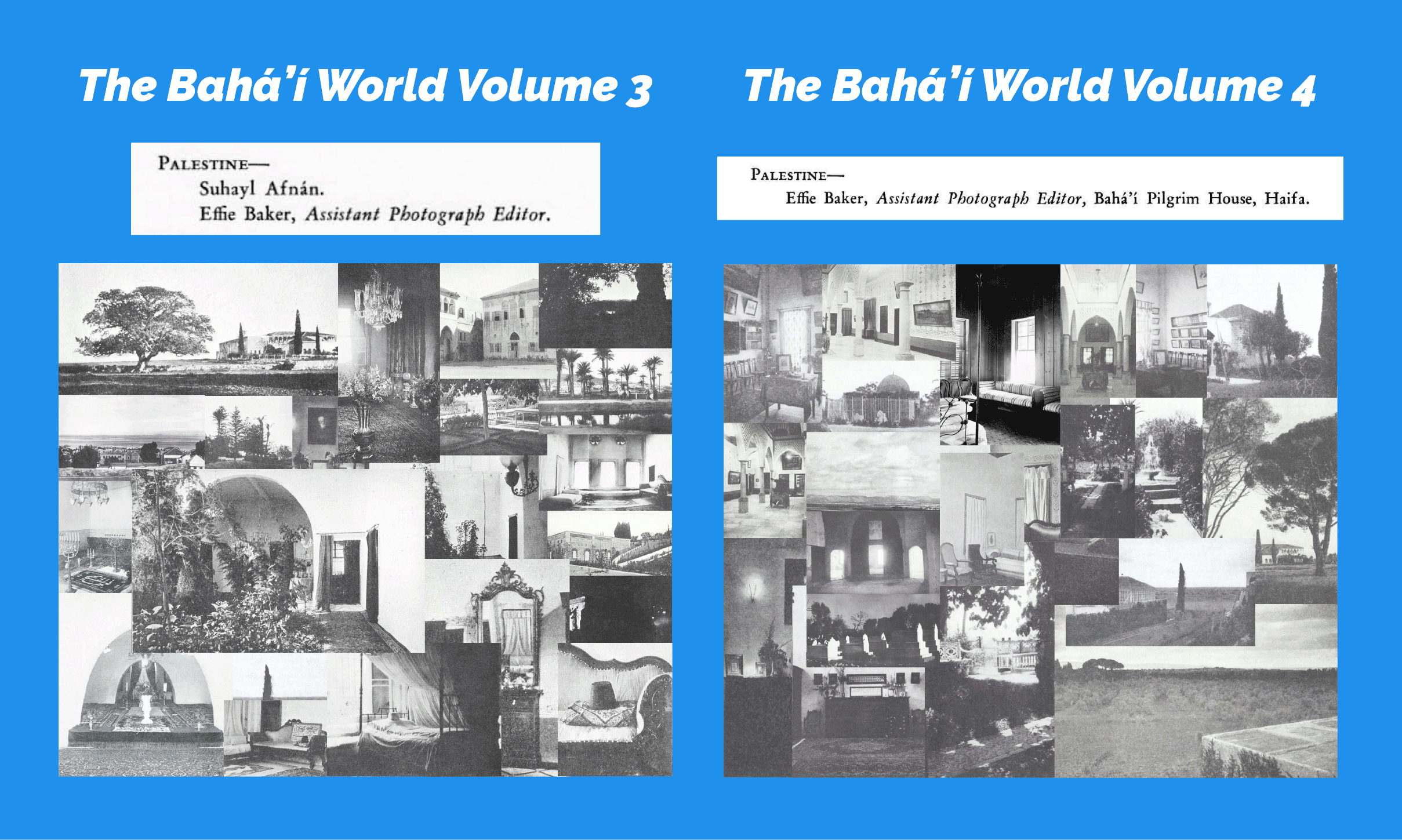

All the photographs taken of the Holy Places in 'Akká and Haifa—including rare photographs of the inner sanctum of the Shrines of Bahá'u'lláh and the Báb—by Effie Baker “Assistant Photograph Editor” of the Bahá'í World, for Volume 3 and Volume 4 of The Bahá'í World.

In the first ten years of the Guardian’s ministry, several Bahá'ís had taken photographs of the Bahá'í Holy Places. Dr. Edward Getsinger took photos in 1900, Thornton Chase in 1907, Curtis Kelsey and Clarence L. Welsh both took photos during their pilgrimage in 1920, and Dr. Luṭfu’lláh Ḥakím began taking pictures in 1921, through the all the events preceding and following the Ascension of 'Abdu'l-Bahá on 28 November 1921, and for decades after.

Shoghi Effendi was himself a talented photographer. He was the one who took the 1919 photograph of the monument for the Greatest Holy Leaf which appears as the frontispiece of The Bahá'í World Volume 5. Rúḥíyyih Khánum said that photography was Shoghi Effendi’s “one single personal hobby was photography; he took superlatively artistic pictures of the scenery in Switzerland and other places during those early years.” In later years, Effie Baker made transparencies from Shoghi Effendi's negatives, from which she later reproduced prints.

Effie Baker was a very talented and technical photographer in the studio, out in the field, and in the darkroom. She had even mastered the art of coloring photos. In February 1925, she took photographs which were reproduced in Star of the West, and in 1926, she hand-colored photographs of the new gardens at Bahjí. Effie Baker’s photographs from 1925 – 1936 are the first comprehensive and sustained photographic documentation of the Bahá'í Holy Places that we have from any single photographer.

Providentially, Effie arrived in Haifa the same year that Shoghi Effendi was preparing to publish the very first volume of The Bahá'í World, and she provided a few photographs for this issue. Then, later in 1925, she began taking specific photos at the Guardian’s request and she was listed as the “Palestine photographic editor” for The Bahá'í World Volumes 3 and 4.

At first, Effie used a Kodak 1A-Autographic (Kodak junior), a folding camera for 120 film (6x9 cm), and a Plate Camera and auto focus enlarger—offered to her by the Canadian Bahá'í and future Hand of the Cause Fred Schopflocher—which she accessorized with supplementary lenses in the 1930s.

Jean Stannard was a steadfast Bahá'í from the time of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, fluent in French and Persian, and who had been pioneering for years in Egypt.

In February 1925, she came on pilgrimage, and consulted with Shoghi Effendi about where she could move to next in Europe. She was thinking of moving to Lausanne, but Shoghi Effendi immediately replied:

Geneva.

Jean Stannard was surprised at Shoghi Effendi’s answer but moved to Geneva, Switzerland. At the time, Geneva was the hub of international organizations, and Jean Stannard quickly integrated in that world. Soon after her arrival, she established the International Bahá'í Bureau.

Shoghi Effendi’s vision for the International Bahá'í Bureau was as a communications hub between Bahá'í groups and communities worldwide, and Shoghi Effendi’s star servant, Martha Root, soon joined the Bureau. Martha Root would organize the Esperanto Congresses of 1925 and 1926 in the Bureau’s offices, and it was during one of these events that Lydia Zamenhof, the daughter of L.L. Zamenhof, the inventor of Esperanto, first learned of the Bahá'í Faith.

The International Bahá'í Bureau was a very important organization for Shoghi Effendi and he described its role:

Geneva is auxiliary to the Center in Haifa. It does not assume the place of Haifa, but is auxiliary. It exercises no international authority; it does not try to impose, but helps and acts as intermediary between Haifa and other Bahá’í centers. It is “international” because it links the different countries; it is like a distributing centre.

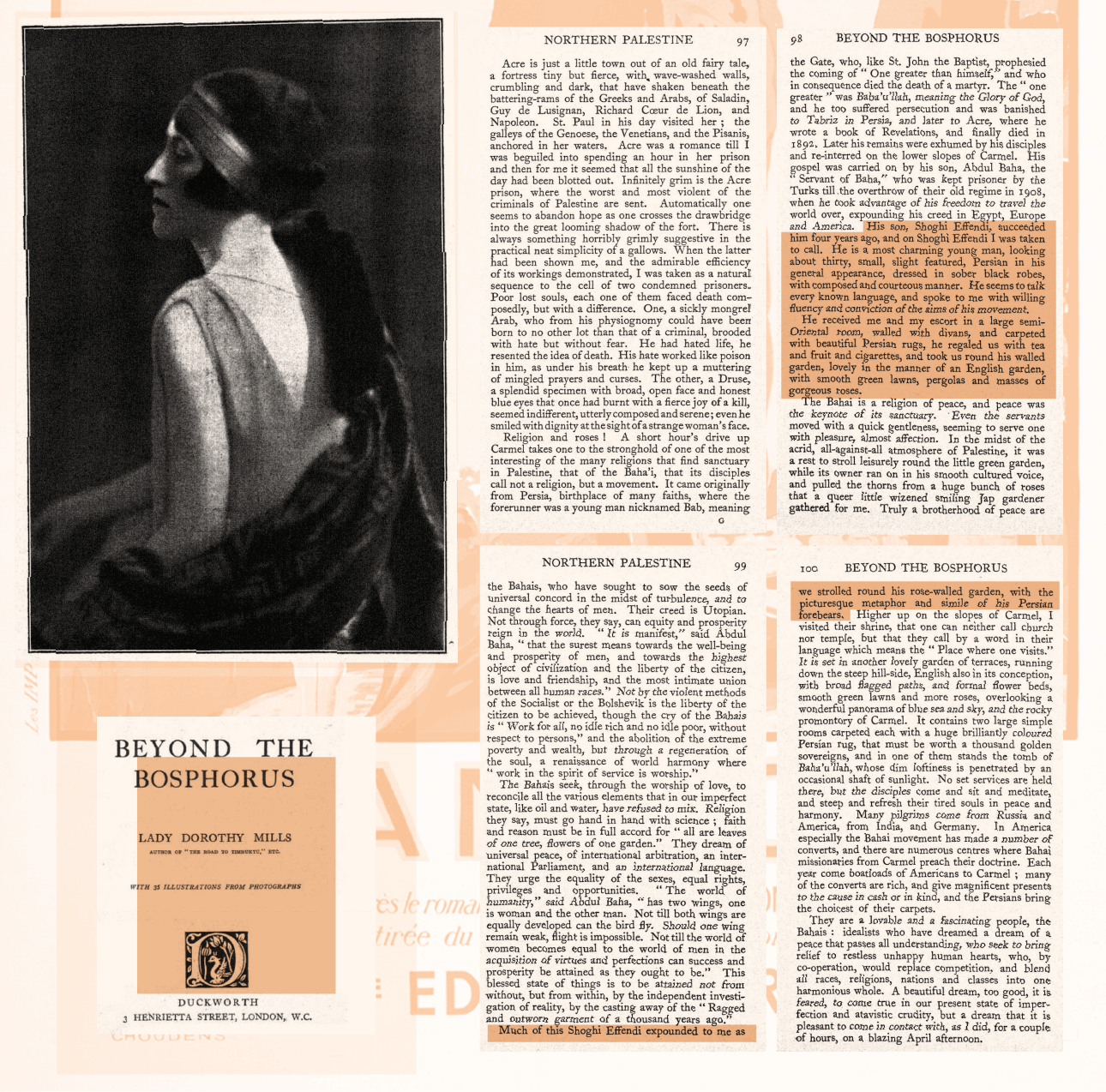

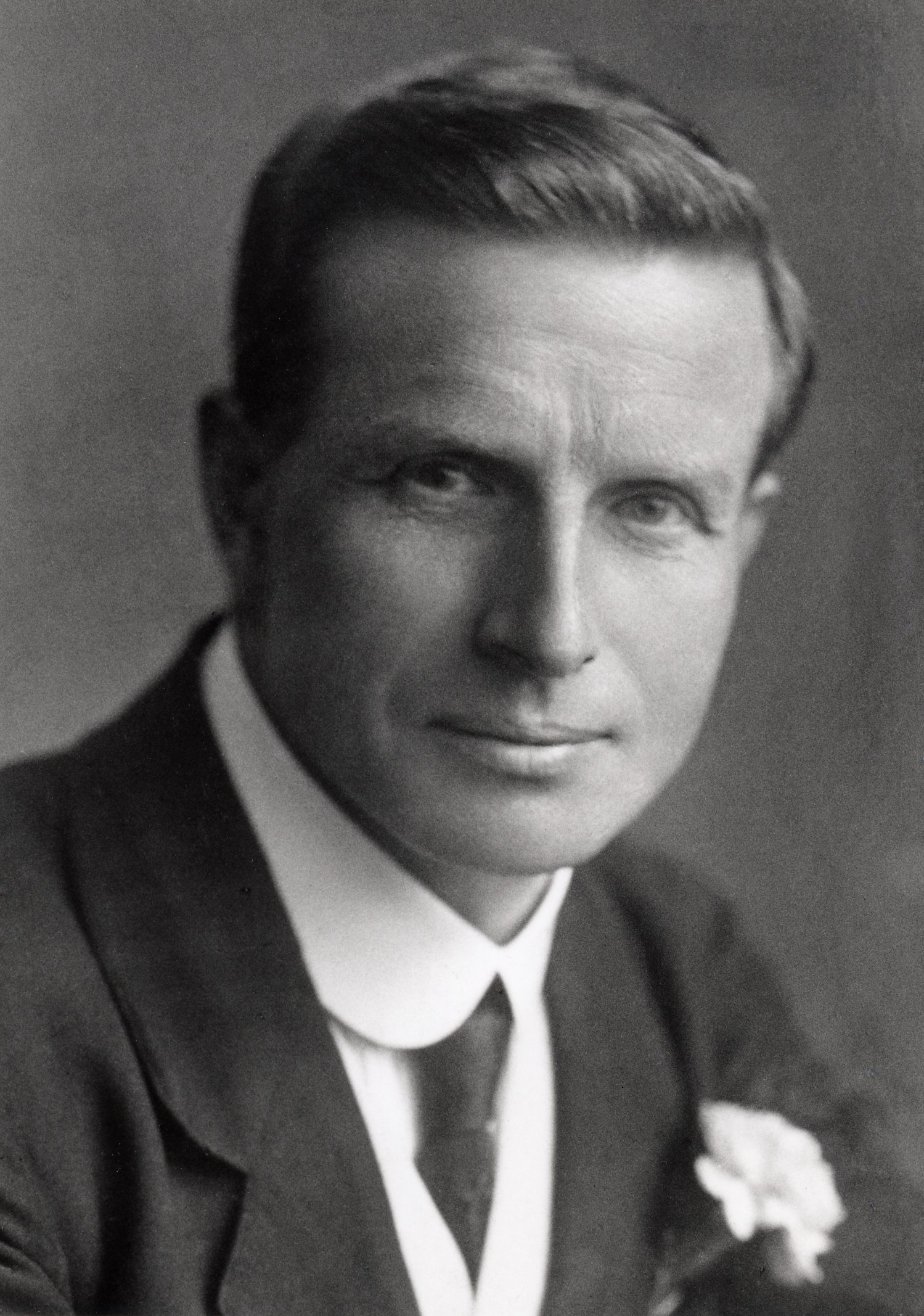

Photograph of Lady Dorothy Mills and the paragraph where she describes Shoghi Effendi on page 98 of Beyond the Bosphorus, along with the cover the book and the four pages in which she speaks about the Bahá'í Faith. Source: Internet Archive.

In order to offer as complete an image of Shoghi Effendi as possible, we have chosen to include two portraits of Shoghi Effendi by people who were not Bahá'ís. This is the first one, and the second, in 1938 is by Rom Landau in 1938.

Lady Dorothy Mills was born Kensington, London, the daughter of Robert Horace Walpole, the 5th and final Earl of Orford, and his American-born wife, Countess Louise Melissa Corbin. Lay She was a Soroptimist and a Founder the Soroptimist London chapter in 1923. The Soroptimist movement, was founded in the United States in 1921 as a global volunteer service for women as a reaction against all-male organizations like the Rotary Club. The relatively baroque name was a neologism composed of two words: the Latin words soror "sister" and optima "best," meant to imply "best for women".

Lady Dorothy Mills married Captain Arthur F. H. Mills of the Duke of Cornwall's Light Infantry after he was wounded in World War I in 1916, and her wedding ring was fabricated from a bullet that had wounded her husband in combat during World War I. Mills was an author of both fiction and non-fiction books, and an adventurous traveler.

She was the first western woman to travel to Timbuktu, Mali, and in the course of her tour of the Middle East, she traveled to British Mandate Palestine, meeting Shoghi Effendi in Haifa on a blazing hot day of April 1925, and recording her first impressions of the Guardian:

He is a most charming young man, looking about thirty, small, slight featured, Persian in his general appearance, dressed in sober black robes, with composed and courteous manner. He seems to talk every known language, and spoke to me with willing fluency and conviction of the aims of his movement…

Lady Mills described the stark contrast between the acrid, antagonistic mood in the Holy Land and Shoghi Effendi’s beautiful little green garden, and described her conversation with the Guardian and “his smooth cultured voice,” as he accompanied her through the small garden around the Shrine of the Báb, pulling the thorns from a huge bunch of roses that Saichiro Fujita had picked for Lady Mills.

For two hours, Shoghi Effendi spoke to Lady Mills at length on the Bahá'í teachings, and Lady Mills kept meticulous notes of what he said, as they strolled around his rose-walled garden, describing how the Guardian spoke the Faith as distinctly eastern in style, “with the picturesque metaphor and simile of his Persian forebears.”

Lady Mills described Bahá'ís in affectionate and loving terms:

They are a lovable and fascinating people, the Bahais: idealists who have dreamed a dream of a peace that passes all understanding, who seek to bring relief to restless unhappy human hearts, who, by co-operation, would replace competition, and blend all races, religions, nations and classes into one harmonious whole. A beautiful dream, too good, it is feared, to come true in our present state of imperfection and atavistic crudity, but a dream that it is pleasant to come into contact with.

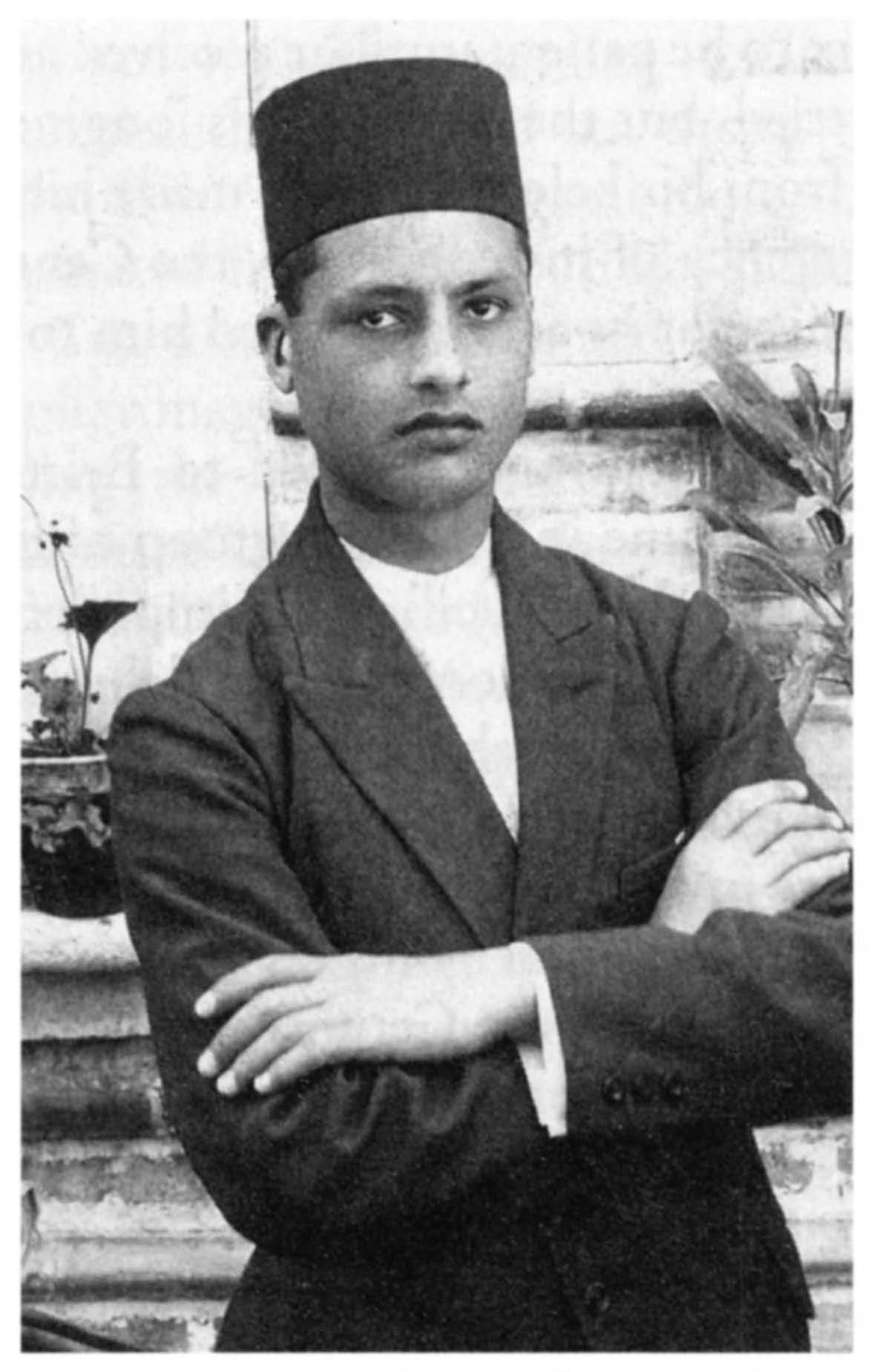

Dhikru’lláh Khadem’s passport photograph from his first pilgrimage in 1925, to the Bahá'í World Center and the presence of the Guardian. The trip made a deep and lasting impression on Zikrullah. Source: With Love: Dhikru’lláh Khadem: The Itinerant Hand of the Cause of God, Javidukht Khadem, page 33.

Shortly after the Ascension of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, in 1921/1922, the Central Spiritual Assembly of Persia advised the Bahá'í community to express their loyalty to the Guardian. Dhikru’lláh Khadem, the future Hand of the Cause, was 18 years old, and he eagerly obeyed, writing a letter to his beloved Guardian and pledging his love and devotion. In response to his beautiful letter, the Guardian sent him a letter, and that was it for Dhikru’lláh. His heart was fully enkindled, and Shoghi Effendi’s letter created in his heart an irrepressible desire to attain the Guardian’s presence. After receiving that letter, going on pilgrimage to the Holy Land was the only thought in his mind. His heart had been set on fire.

Javidukht Khadem, Dhikru’lláh Khadem’s wife described the three years, between the time Dhikru’lláh received his first letter from the Guardian and the time he arrived in Haifa for his pilgrimage in 1925 as spiritual stages of longing:

The ardor, the anguished waiting, the torrent of emotions when he finally attained his goal. He ardently prayed for the opportunity to attain the beloved Guardian's presence and to visit the holy shrines. Eager for any news, hoping to quench vicariously his burning thirst for contact with Shoghi Effendi, he sought the company of anyone going on or returning from pilgrimage.

One day, Dhikru’lláh passed through the Customs Office and was drawn, like a magnet, into a conversation with a European traveler who had a Haifa sticker on his suitcase. The traveler did not know about the Bahá'í Faith.

In a dream one night, Dhikru’lláh made his pilgrimage to the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh and the presence of the beloved Guardian, and wept so profusely that, when he awoke, his pillow had been drenched with his tears.

By 1925, the 21-year-old Dhikru’lláh was so eager to go on pilgrimage that he began preparations for his journey: he applied and obtained a passport with the help of a friend, and he packed his suitcase, then realized…he had not received permission to come on pilgrimage. As luck would have it, Dhikru’lláh met Ḥájí Amín, the Trustee of the Ḥuqúqu’lláh from the time of 'Abdu'l-Bahá,

Fortuitously, he encountered Ḥájí Amín, the trustee of Ḥuqúqu’lláh since the time of Bahá'u'lláh, who offered to write the Guardian a letter requesting permission for Dhikru’lláh to come on pilgrimage. But Dhikru’lláh was on fire and the humble request of Ḥájí Amín was not enough for him. He wanted a stronger, more urgent plea. Finally, his patience ran out and he left Persia for Baghdad, to await the Guardian’s permission there. When the Central Assembly of Iraq advised him to be patient, the intensity of his longing made him ill and the Bahá'ís of Iraq told him to travel to Haifa, and that they would take responsibility for his not having obtained permission.

Dhikru’lláh Khadem left Baghdad, traveled to Damascus, and arrived in Beirut where he traveled by car, overland to Haifa with a group of Europeans, assailing his traveling companions with incessant questions about how much farther Haifa was, until they unceremoniously dumped him and his luggage at the gate of the House of 'Abdu'l-Bahá at 7 Haparsim.

Then, it hit him. He had not received permission from the Guardian to be where he was standing, and he began to feel remorseful about his rashness, and as he was standing there, Dr. John Esslemont—the Guardian’s secretary—and a Dutch pilgrim saw him from the window of the western Pilgrim House and went out to welcome him.

One of the Bahá'ís recognized Dhikru’lláh and immediately handed him his letter of permission for pilgrimage that had been prepared that day and was about to be mailed to him!

A portrait of 'Abdu'l-Bahá standing, holding a rose in His hand. Dr. Jena Khadem-Khodadad, Dhikru’lláh Khadem’s daughter, believes this might be the photograph given to her grandfather by the Guardian, as stated in an email communication dated 4 January 2024. Source: Storytelling in the Bahá'í Faith.

Dhikru’lláh Khadem’s first pilgrimage had a profound influence in directing that same ardor he had demonstrated in entering the presence of the Guardian into Bahá'í service for the next 6 decades of his life. The Guardian asked the ardent young man, eager to perform any service for his beloved Guardian, to share with the Persian Bahá'í youth his love and his encouragement and to ask them to deepen themselves in the Faith, to study English, and English literature in particular. Dhikru’lláh would be the first to obey the Guardian, and would be a lifelong student of English.

Dhikru’lláh was present while the Guardian was laying out the additional three rooms to the original Shrine of the Báb, bringing the total project plan of 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s 9 rooms into reality. One day during this pilgrimage, Shoghi Effendi came into the gardens and summoned Áqá Raḥmatu’lláh, the gardener, asking him for string and a handful of plaster. The Guardian asked Dhikru’lláh to hold one end of the string while he poured plaster powder on the ground along the line formed by the string to draw the three additional rooms on the ground so he could better visualize them.

Shortly before he left Haifa, Dhikru’lláh Khadem asked the Guardian for his photograph. Instead, the Guardian gave Dhikru’lláh a beautiful photo of 'Abdu'l-Bahá holding a rose in His hand and said to him:

I give you a portrait of the beloved Master as a souvenir.

Dhikru’lláh Khadem cherished this gift with all his heart, and he returned to Persia lit with devotion for the Guardian and an insatiable thirst to serve him at all times.

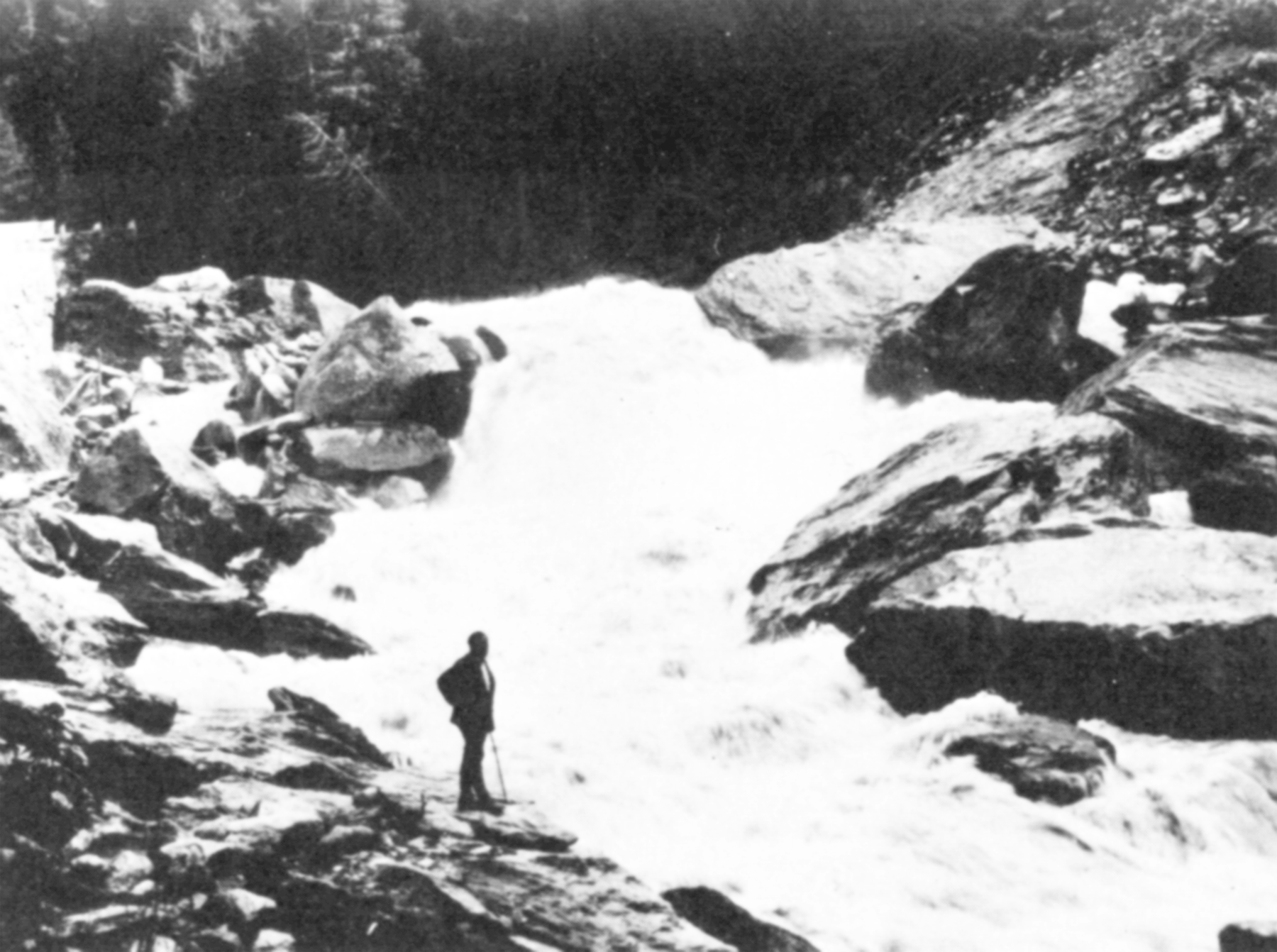

Shoghi Effendi by a glacier with a walking pole. Source: The Priceless Pearl.

Shoghi Effendi spent five months in Switzerland in 1925.

He was a serious, experienced hiker, and Interlaken, where he always stayed, was the starting point for countless trails into the Bernese Alps. The views are stunning, spectacular, as the mountains overlook many lakes in the region.

Shoghi Effendi would leave for his strenuous hikes before sunrise, wearing sturdy hiking boots, knee-length trousers, heavy black puttees—a strip of wool wound tightly around his calves, a loose tweed jacket and a small, cheap canvas backpack.

He would take a train to the foot of some mountain or pass and begin his very long hike, often walking 10 to 16 hours alone. Whenever his young family members tried to accompany him, they would never be able to stand the pace.

Shoghi Effendi shared his passion for walking with his beloved Grandfather. 'Abdu'l-Bahá walked several times a day, if He could, during His journeys to the west. Often people tried to keep up with the Master during His vigorous walks all over Europe and America, and they were always surprised at how brisk His pace was.

Sometimes Shoghi Effendi climbed even higher mountains, but for these expeditions, he would be roped to a seasoned Swiss guide.

The longest hike Shoghi Effendi ever completed was 42 kilometers over two mountain passes.

Shoghi Effendi always hiked through inclement weather, if ever got caught in the rain, he would simply let his clothes dry on his back as he kept walking.

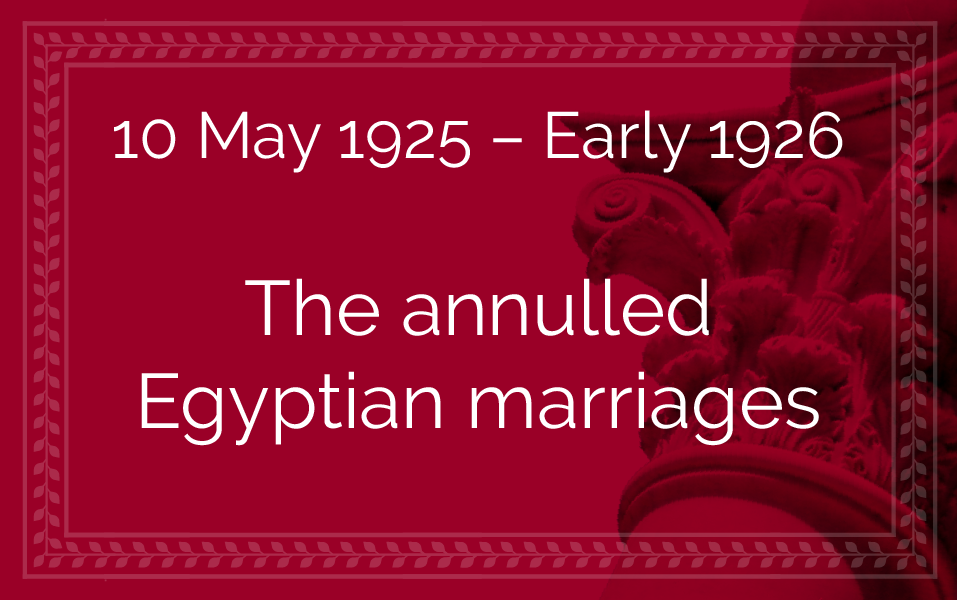

Beba, Egypt. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Egypt was one of the very first countries in which the Faith of Bahá'u'lláh was established in His lifetime.

In all Islamic countries, all matters pertaining to civil law were administered by religious courts. For several years, Hippolyte Dreyfus had met with and provided legal support to the Bahá'ís in Egypt in the hopes that the Egyptian authorities would recognize the independent character of the Bahá'í Faith and allow Bahá'ís to refer their legal matters to independent tribunals instead of Muslim courts.

Then, everything changed in a small village in Upper Egypt.

When the Bahá'ís of Kawmu’ṣ-Ṣa‘áyidih formed their Local Spiritual Assembly, the local fanatical tribal leader began stirring up mischief against three Bahá'ís, legally demanding that their Muslim wives divorce them on the grounds that the Bahá'ís were now heretics to Islam.

The case was sent to the Appellate religious court of the district of Beba.

The court delivered their judgement on 10 May 1925, strongly condemning the three heretics for violating the laws and ordinances of Islam and annulled their marriages.

What outwardly seemed like a defeat for Bahá'ís, was, in fact, a great victory in the eyes of the Guardian, rather it was “the first charter of liberty emancipating the Bahá’í Faith from the fetters of orthodox Islam.”

By declaring the three Bahá'ís heretics, the district court of Beba had in fact, declared the Bahá'í Faith a religion independent of Islam. In the words of Shoghi Effendi:

It even went so far as to make the positive, the startling and indeed the historic assertion that the Faith embraced by these heretics is to be regarded as a distinct religion, wholly independent of the religious systems that have preceded it.

The formal verdict listed the fundamental principles and laws of Islam, gave a detailed list of the Bahá’í teachings—from the Kitáb-i-Aqdas, the writings of 'Abdu'l-Bahá and those of Mírzá 'Abu'l-Faḍl—and demonstrated that the three defendants had given up Islam upon becoming Bahá'ís.

The verdict formally declared in the most unequivocal terms that:

The Bahá'í Faith is a new religion, entirely independent, with beliefs, principles and laws of its own, which differ from, and are utterly in conflict with, the beliefs, principles and laws of Islam. No Bahá'í, therefore, can be regarded a Muslim or vice-versa, even as no Buddhist, Brahmin, or Christian can be regarded a Muslim or vice-versa.

A year later, the Guardian would revisit the situation in Egypt, and the Beba verdict would go down in history.

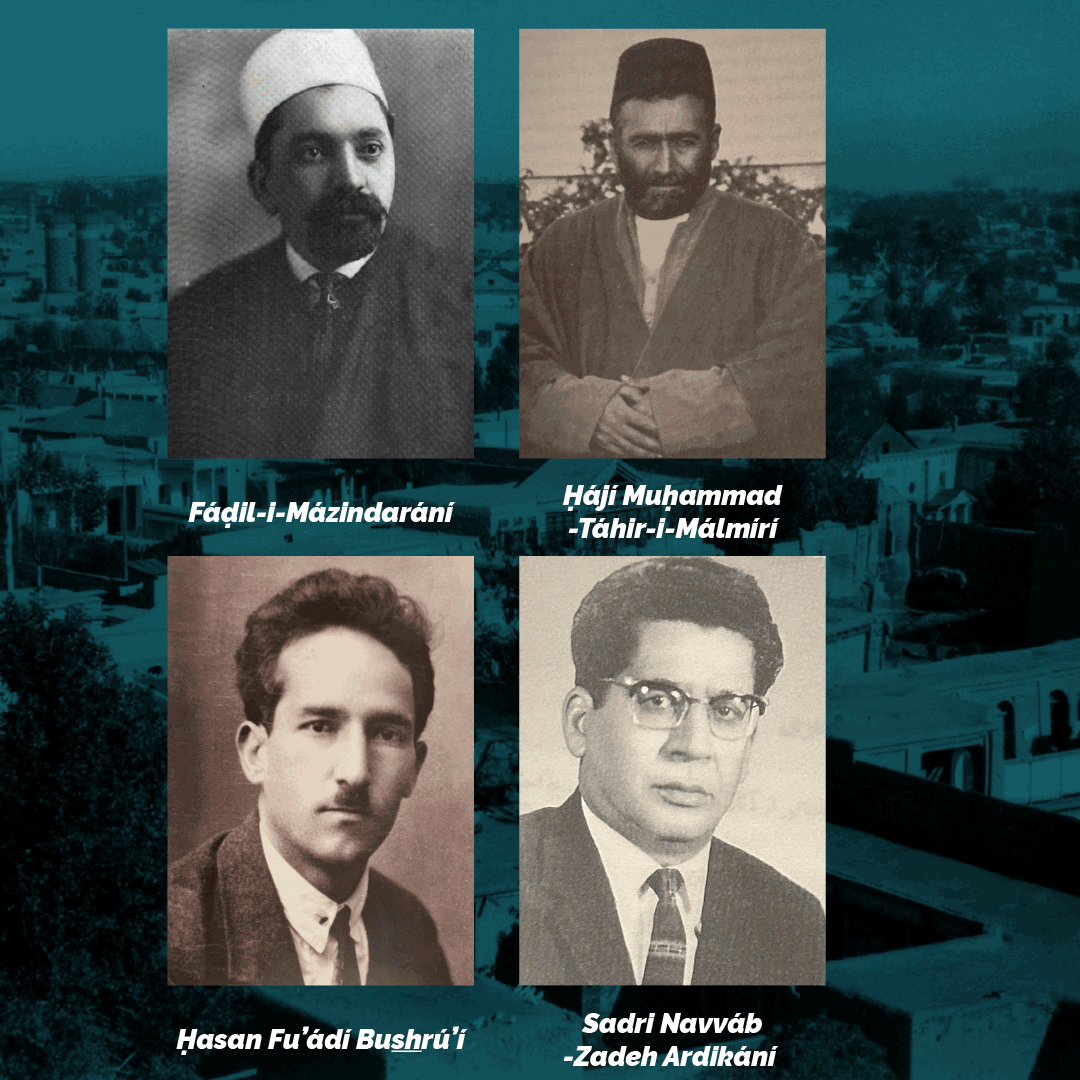

Top left: Fáḍil-i-Mázindarání, an eminent and devoted Bahá'í teacher and historian, among those whom the Guardian tasked with writing histories of Persia’s regions and cities. Top right: Ḥájí Muḥammad -Táhir-i-Málmírí (who wrote the History of the Martyrs of Yazd). Bottom left: Ḥasan Fu’ádí Bushrú’í (who wrote the History of the Bahá'í Faith in Khurásán). Bottom right: Sadri Navváb-Zadeh Ardikání (who wrote The Bahá'í Faith in Ardikán). Many thanks to Dr. Bijan Masumian for providing these four photographs and their historical context.

Three short years after the beginning of His Guardianship, Shoghi Effendi’s lifelong dedication to preserving the precious history of the Bahá'í Faith was already in place. From the beginning of his ministry, he had encouraged the Bahá'ís of Persia to start compiling the history of the Faith in their country, and had asked them to gather historical information on events having transpired during the Heroic Age.

On 25 October 1925, Shoghi Effendi wrote a letter to the Central Assembly of Ṭihrán stating that he hoped this new history would soon be completed and disseminated throughout the Bahá'í community.

The Bahá'í Central Assembly of Ṭihrán first appointed a central committee to oversee the efforts of writing Bahá'í history in several provinces and cities in Persia for the writing of a number of histories of the Baha’i Faith in the various provinces and cities of Persia as well as the writing of a general history. The work of the committee was later taken over by Fádil Mazandarani, who was a member of the Central Assembly, and under his guidance, several Local assemblies prepared local histories of the Faith in their area and sent to them to the Guardian.

As a result of the Guardian’s encouragement, prominent local Baha’is wrote a series of local Bahá'í histories were written in the late 1920s and early 1930s on provinces such as Ádhirbáyján, Khurásán and Gilan cities such as Isfahan, Hamadán, Yazd, and Sháhmirzád, and smaller communities such as Milán, Nayríz, Abadih, Sangsar, Núr and some of the villages around Yazd.

This important work was continued in the decades since then, and there are now dozens of precious local Bahá'í histories for many cities and regions around Iran.

Dr. Esslemont, a close friend of Shoghi Effendi’s had been his secretary for exactly one year, since November 1924, when he died, suddenly and very unexpectedly in from complications of his tuberculosis.

Shoghi Effendi sent heartfelt condolences to Dr. Esslemont’s family:

Overwhelmed with sorrow at passing dearly-beloved Esslemont. All devoted efforts unavailing. Be assured of heartfelt sympathy condolences myself and Bahá'ís world over. Letter follows.

Four days letter, in the letter he had promised, Shoghi Effendi expounded on his deep pain at the loss of a cherished friend and valued coworker and a distinguished international figure and author in the Bahá'í world:

It is no exaggeration to say that I find no words to express adequately the sense of personal loss I feel at the passing of my dear collaborator and friend John Esslemont.

Shoghi Effendi added that his masterpiece, Bahá'u'lláh and the New Era "would inspire generations yet unborn" but gave a touching testimonial of what Dr. Esslemont had meant to him, personally, as he was, in Shoghi Effendi’s words:

…the warmest of friends, a trusted counsellor, an indefatigable collaborator, a lovable companion.

The Guardian wept for his friend for days, and he immediately cabled England, America, Germany, Persia and India to hold memorial meetings for Dr. Esslemont and to cable their condolences to Esslemont's relatives, none of whom were Bahá'ís.

Shoghi Effendi would posthumously raise Dr. J.E. Esslemont to the rank of Hand of the Cause.

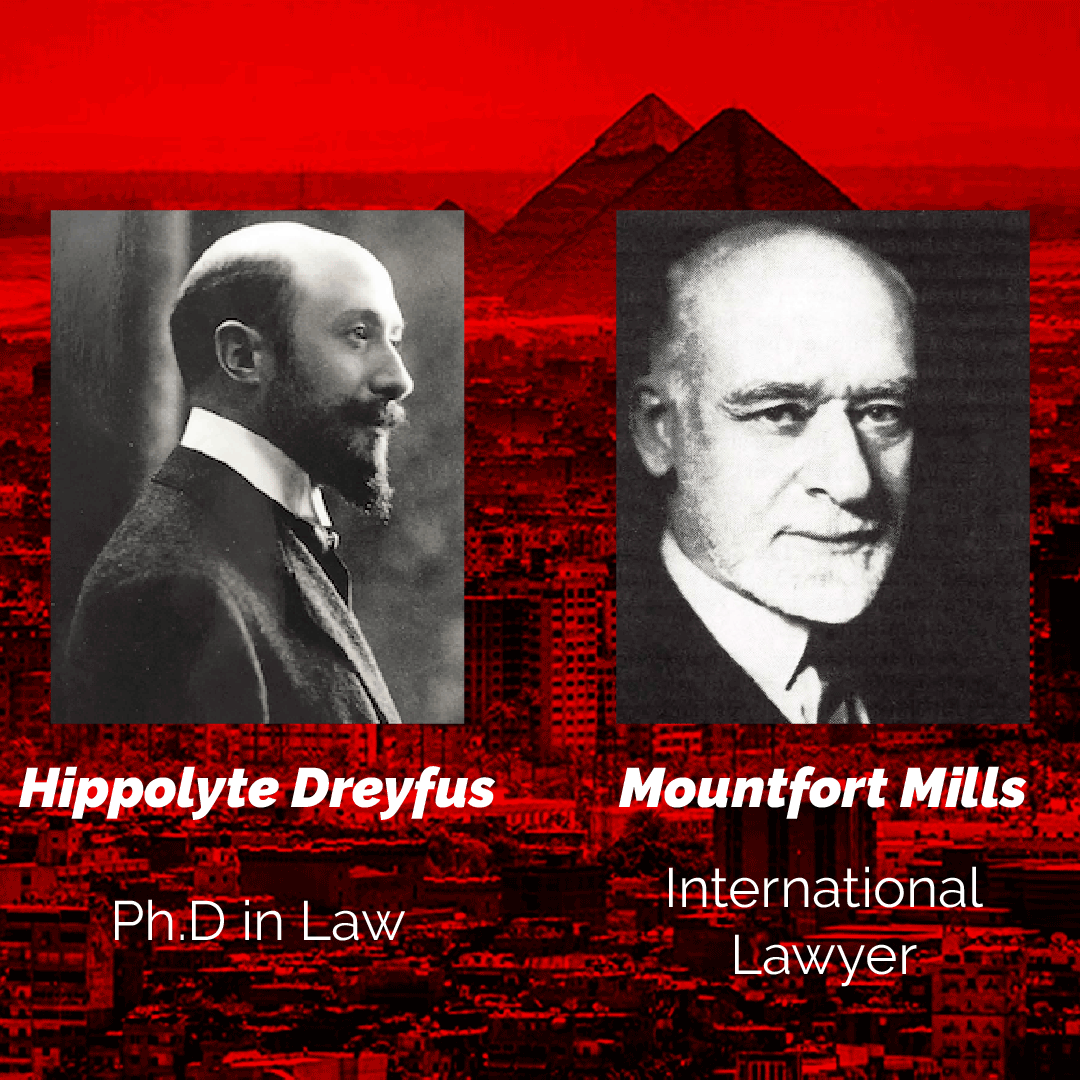

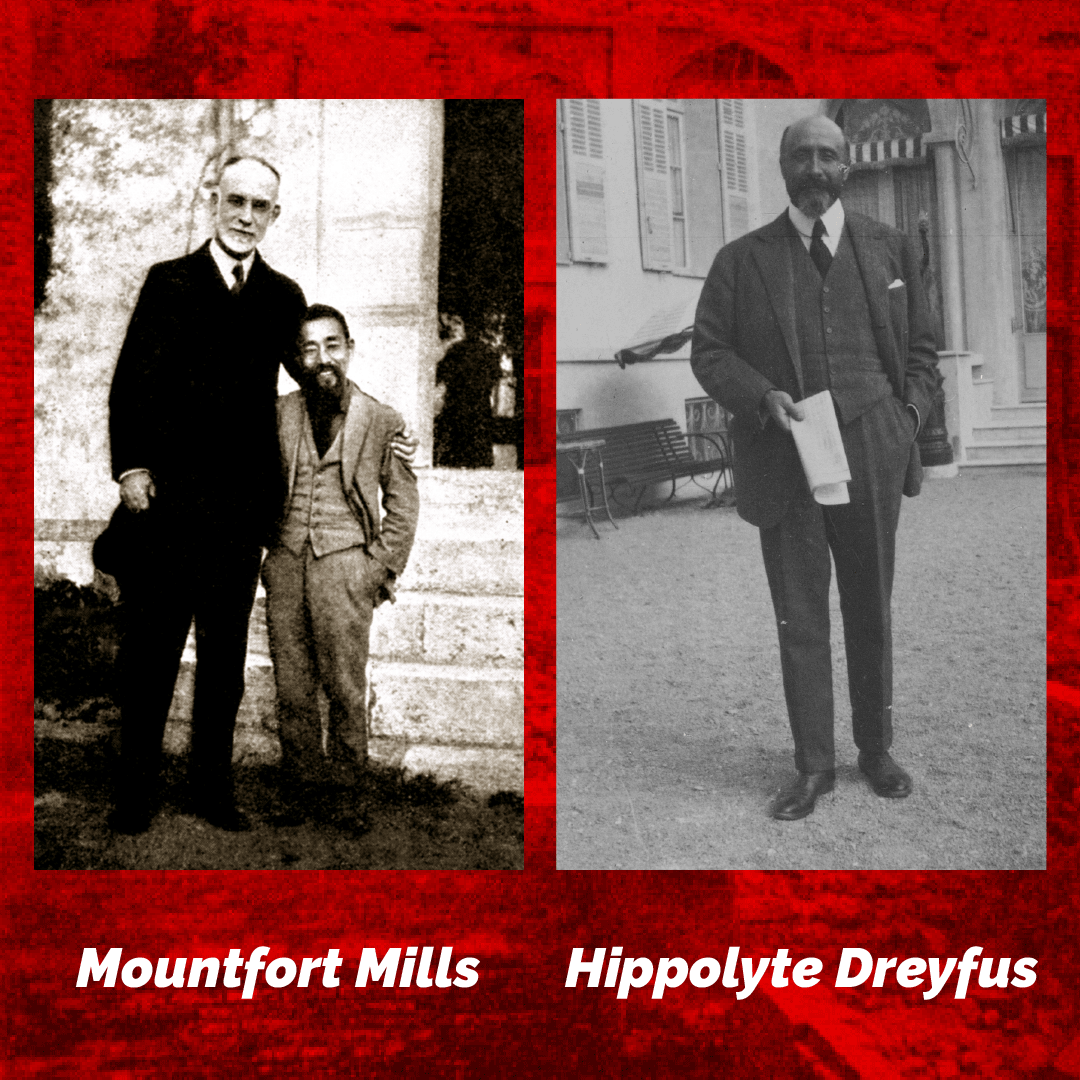

Shoghi Effendi’s crack legal team: Hippolyte Dreyfus, the first French Bahá'í who obtained a Ph.D. in Law (Bahaipedia) and Mountfort Mills, an American Bahá'í and international lawyer (Bahaipedia).

In early January 1926, the Guardian called Hippolyte Dreyfus and Mountfort Mills, two outstanding Bahá'ís and expert lawyers to the Holy Land for consultation on the situation in Egypt. In the Holy Land, the Guardian gave them instructions to travel to Egypt and plead with Egyptian authorities for the national legitimization of this local verdict, and the recognition of an independent civil status for members of the Bahá'í community.

A few weeks later, by the end of January 1926, the two friends were in Cairo, and had secured meetings with the Prime Minister, the Minister of the Interior and the British High Commissioner and his advisor.

At each of these meetings, Hippolyte Dreyfus and Mountfort Mills were received with great courtesy and their interlocutors showed were understanding of their appeal. Despite the complexity of the problem, the various authorities seemed sincere in their desire to act and Hippolyte Dreyfus’ extraordinary skills of political analysis and diplomacy were a great help.

Beyond the efforts of Mountfort Mills and Hippolyte Dreyfus, the National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá'ís of Egypt fought for years to obtain a modicum of recognition of the Faith’s independent status.

They used the Beba Court’s judgement, published a compilation of Bahá'í laws relating to matters of personal status, and used repeated incidents provoked by fanatical Muslims to obtain plots of land from the Egyptian government, to be used exclusively as Bahá'í cemeteries.

The Beba verdict—officially declaring the Bahá'í Faith an independent religion—was eventually sanctioned and upheld by the highest ecclesiastical courts in Egypt, and printed and circulated by the Muslims themselves.

The Guardian seized the Beba verdict, this powerful new implement, handed to him by the enemies of the Faith themselves, and used it as a badge of honor until the end of his life, telling the Bahá'ís in eastern and western countries to use the verdict as definitive proof that the Bahá'í Faith was not a sect of Islam.

The compilation on Bahá'í laws was translated into Persian and English and used as a guide to running Bahá'í affairs in countries which lacked civil laws to cover such matters.

The battle was far from won, of course, and for decades after, Bahá'ís in Muslim countries continued to live in a legal no-man’s-land, but Bahá'ís accepted this hardship proudly, refusing to be humiliated, and would continue their struggle to be recognized as members of an independent religion.

The Guardian, speaking of the Beba verdict, stated that:

This decision, however locally embarrassing, in the present stage of our development, may be regarded as an initial step taken by our very opponents in the path of the eventual universal acceptance of the Bahá’í Faith, as one of the independent recognized religious systems of the world.

In God Passes By, when speaking of the events surrounding the Beba verdict, the Guardian shared his infallible interpretation of history:

To all administrative regulations which the civil authorities have issued from time to time…the Bahá'í community, faithful to its sacred obligations towards its government, and conscious of its civic duties, has yielded, and will continue to yield implicit obedience…To such orders, however, as are tantamount to a recantation of their faith by its members, or constitutes an act of disloyalty to its spiritual, its basic and God-given principles and precepts, it will stubbornly refuse to bow, preferring imprisonment, deportation and all manner of persecution, including death—as already suffered by the twenty thousand martyrs that have laid down their lives in the path of its Founders—rather than follow the dictates of a temporal authority requiring it to renounce its allegiance to its cause.

In later years, Shoghi Effendi used the Beba verdict as proof for the Israeli Minister of Religious Affairs that the Department Head handling the Muslim community in Israel could not be the same person to handle the Bahá'í community, which would create the impression that the Bahá'í Faith was related to Islam in some way.

Queen Victoria, full-length portrait, facing left, photograph taken after 1862, four years before Bahá'u'lláh sent Queen Victoria a Tablet. Queen Victoria was the paternal grandmother of Queen Marie of Romania. Source: Library of Congress.

How great the blessedness that awaiteth the king who will arise to aid My Cause in My kingdom, who will detach himself from all else but Me! Such a king is numbered with the companions of the Crimson Ark—the Ark which God hath prepared for the people of Bahá. All must glorify his name, must reverence his station, and aid him to unlock the cities with the keys of My Name, the omnipotent Protector of all that inhabit the visible and invisible kingdoms. Such a king is the very eye of mankind, the luminous ornament on the brow of creation, the fountainhead of blessings unto the whole world. Offer up, O people of Bahá, your substance, nay your very lives, for his assistance.

Bahá'u'lláh, The Kitáb-i-Aqdas, verse 84.

A portrait of Martha Root future Hand of the Cause, indefatigable teacher of the Cause and one of the very rare individuals mentioned by name in God Passes By during the period relating to the Formative Age of the Faith. Source: Alchetron.

Queen Marie, the beloved queen of Romania, was the grand-daughter of Queen Victoria of England, and the Russian Czar Alexander II, two monarchs who had not only been directly addressed by Bahá'u'lláh, but also had not turned away from Him.

Martha Root, who had first served 'Abdu'l-Bahá and now served Shoghi Effendi devotedly, zealously and indomitably, arrived in Romania around 26 January 1926, and she was deeply convinced that even a queen deserved to know about the message of Bahá'u'lláh.

Shoghi Effendi would say of Martha Root:

In her case we have verily witnessed in an unmistakable manner what the power of dauntless faith, when coupled with sublimity of character, can achieve, what forces it can release, to what heights it can rise.

Despite a daily speaking schedule, and her plans to leave in early February, she began assiduously making contacts in order to meet Queen Marie. She contacted the queen’s lady in waiting, then the American ambassador told her flat out she could not see the queen.

Martha refused to be defeated. On 28 January 1926, she sent Queen Marie a letter, enclosing a photograph of 'Abdu'l-Bahá and Dr. Esslemont’s magnificent book, Bahá'u'lláh and the New Era.

Cotroceni Palace in Bucharest, Romania, was originally built as a monastery in 1679, and was the palace of many of Romania’s rulers. It was rebuilt in 1893, and Queen Marie made requests to renovate the north wing of the palace. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The next day, 29 January, Martha Root received an invitation to visit the Queen at the Cotroceni Palace outside Bucharest on the following day.

Martha Root was elated.

Martha had almost no money, and she prepared extremely humble gifts to bring to Queen Marie: the Greatest Name, a copy of the Seven Valleys, two Esperanto books, her own Esperanto pin, a small bottle of cheap perfume, a little box containing a piece of chocolate wrapped in gold foil, a branch of white lilacs and a report of the Education Congress in Edinburgh, because Queen Marie had been the Princess of Edinburgh before her marriage.

Queen Marie of Romania. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

On 30 January 1926, Martha arrived at the palace, wearing her long white dress, and the doors swung open. She met a lady-in-waiting who led her up a spiral staircase and she arrived at Queen Marie’s drawing room. The Queen walked briskly towards Martha, smiling in her blue silk dress, briefly greeted her then said:

I believe these Teachings are the solution for the world’s problems today!

Queen Marie had stayed up until 3 AM that morning, reading Bahá'u'lláh and the New Era and she found the principles of the Faith very interesting. She asked Martha to tell her about the Cause, and asked a number of questions, and she also gave Martha the name and address of a dear friend of hers in Vienna, whom she encouraged her to visit.

Their meeting was deeply intimate, they confided in each other and spoke about world issues, manners and morals, religions and prejudice, Esperanto and education. It was the beginning of a beautiful friendship. Martha Root would have eight interviews with Queen Marie.

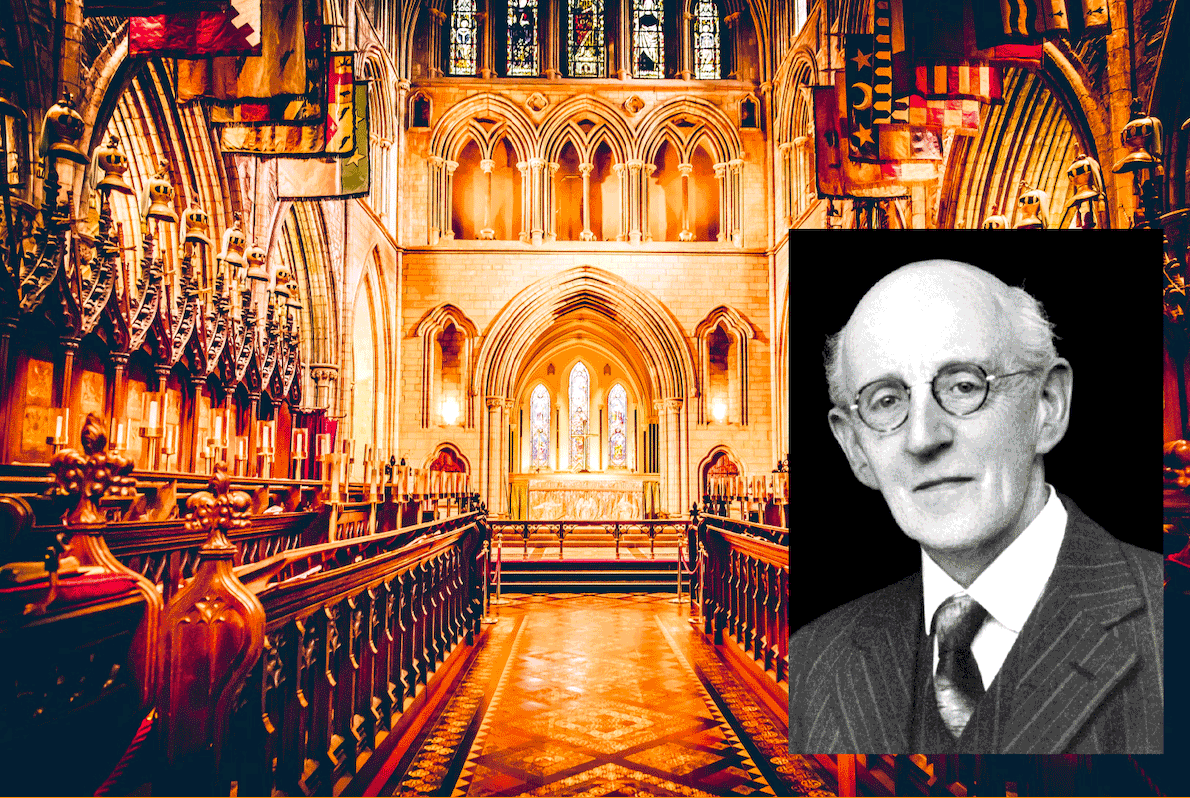

George Townshend, an Irish Anglican clergyman who became a Bahá'í in 1918, after beginning a correspondence with 'Abdu'l-Bahá, but did not officially sever ties with the Anglican church and renounce his orders until he was 790 in 1946. George Townshend also happened to be a very gifted and rather well-known writer, and assisted Shoghi Effendi with the editing of his English translations and with his original manuscript of God Passes By.

A perfect example of the nature of the collaboration between the Guardian of the Faith and George Townshend is illustrated in the way Shoghi Effendi describes it himself in a letter he sent George on 1 May 1926:

I am taking the liberty of forwarding to you some of my recent translations and if you feel that you would like to reshape and reconstruct the whole sentence or bring about a fundamental change in the expression of the thought in some passages, please do not hesitate. I would greatly value your opinion as to the standard of English represented by these recent renderings and would appreciate your detailed comment, criticism and suggestion.

Of course, the Guardian’s English was flawless, but George’s intrinsic, innate, native qualities perfectly complemented Shoghi Effendi’s superlative talent for translation.

George Townshend received translations and simply touched them up, tuned them here and there, making valuable, detailed, careful and sensitive suggestions to Shoghi Effendi. His input in the collaboration was not in translating from Persian and Arabic into English. That was the Guardian’s sole domain as Interpreter of the Holy Writings.

George Townshend was focused on how it read and sounded in English as a lover of the English language, a passion he shared with the Guardian. George Townshend also had excellent intuition and judgement, and he was a loving, kind person, a joy for Shoghi Effendi to work with.

The way their collaboration worked was that the Guardian would send George Townshend typewritten pages with a request for George’s input. Despite the great value that Shoghi Effendi placed on George Townshend’s input on syntax, polishing, refining “englishing” the work, it was the Guardian who was the sole arbiter of final translations, and as such, he decided whether to reject, adopt or change any of George’s editorial suggestions.

The collaboration between George Townshend and Shoghi Effendi is one of the most beautiful stories of partnership in the history of the Faith. That of a Bahá'í assisting the Head of the Faith with unbending loyalty, immense capacity, deep knowledge, and with a heart and mind filled with the love of Bahá'u'lláh to the end.

From Americans and Canadians to British and Persians, women and men, authors and physicians to a railroad executive, the Guardian had at least 16 secretaries during the 36 years of his ministry, if not more.

It is fair to say that from the very beginning of his Guardianship, Shoghi Effendi had needed a capable secretary, and the need only increased in urgency as the years went on.

At first Shoghi Effendi received assistance from members of 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s family, and Dr. Esslemont filled that role perfectly from 1923 to 1925, but after his death, Shoghi Effendi was, once again, without a talented co-worker.

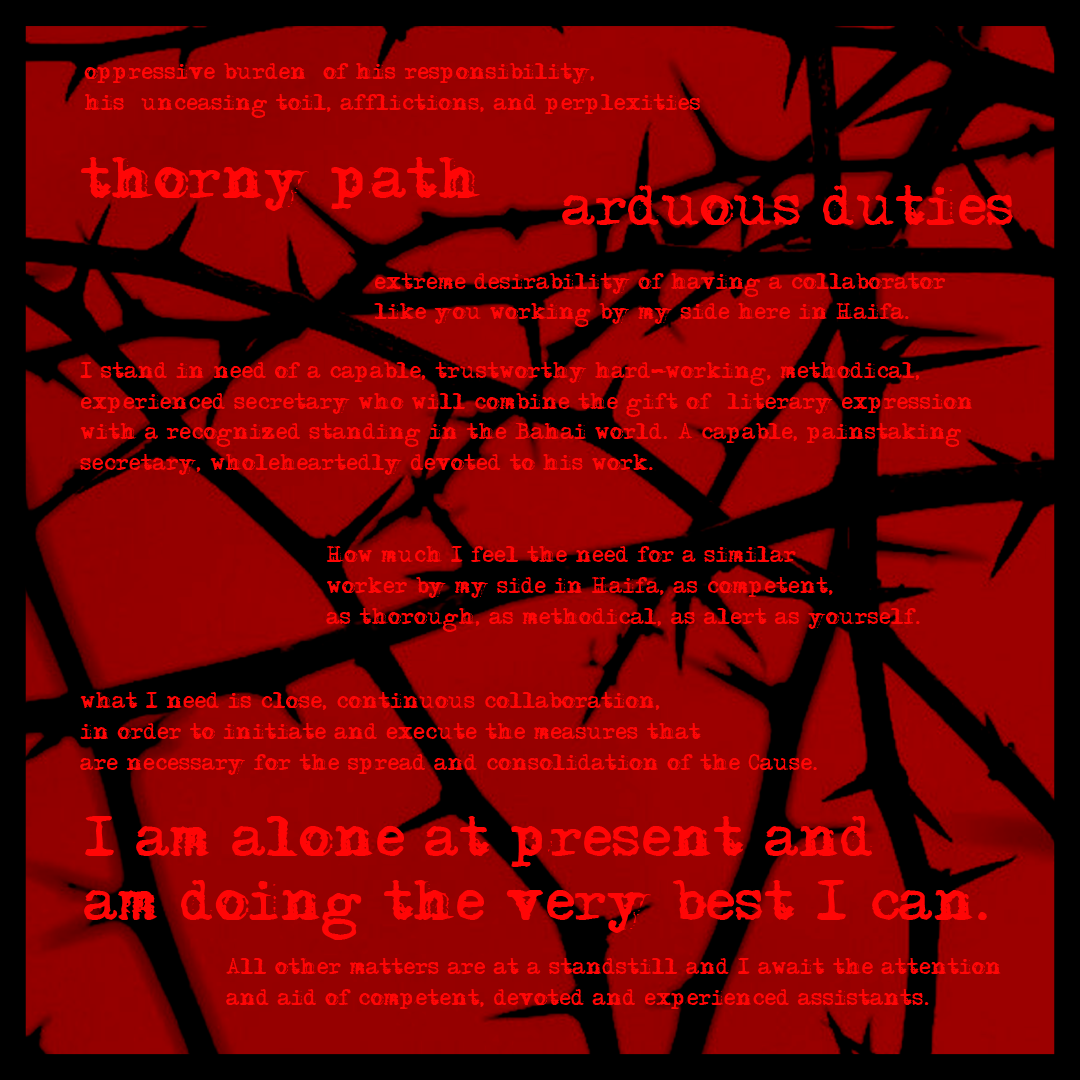

Starting in January 1926, two months after Dr. Esslemont’s passing, Shoghi Effendi already felt the "oppressive burden” of his responsibility, his “unceasing toil, afflictions, and perplexities" and the "thorny path" of his "arduous duties".

Four months later, in May 1926, he wrote to Horace Holley:

I have often felt the extreme desirability of having a collaborator like you working by my side here in Haifa.

On 30 June 1926, while he was in Switzerland, the Guardian wrote to his dear and respected French friend, Hippolyte Dreyfus-Barney, once again laying the qualities that were so hard to find in a dedicated secretary, and expanding on the needs of an office with several advisors:

I stand in need of a capable, trustworthy, hard-working, methodical, experienced secretary who will combine the gift of literary expression with a recognized standing in the Bahá'í world…A capable, painstaking secretary, wholeheartedly devoted to his work, and two chief advisers who would represent the Movement on specific occasions, with dignity and devotion, together with two eastern associates, mentally awake and expert in knowledge, would I feel set me on my feet and release the forces that will carry the Cause to its destined liberation and triumph.

It would have been heart breaking for Hippolyte to receive this letter, after his decades of devoted service to the Center of the Covenant, and not be able to respond positively to the Guardian. His health had suddenly taken a turn for the worst, and he passed away two years later.

In September 1926, Shoghi Effendi wrote to Horace Holley again, emphasizing Holley could not abandon his post, but describing the kind of help he direly needed:

How much I feel the need for a similar worker by my side in Haifa, as competent, as thorough, as methodical, as alert as yourself.

One year later, in September 1927, writing to a friend, Shoghi Effendi speaks about the level of collaboration he desperately needs:

…what I need is close, continuous collaboration, in order to initiate and execute the measures that are necessary for the spread and consolidation of the Cause.

Shoghi Effendi confides in a heartbreaking sentence from a letter written in October 1927:

I am alone at present and am doing the very best I can.

Shoghi Effendi expresses the acute severity of the situation in a single sentence in a letter he wrote in January 1928:

All other matters are at a standstill and I await the attention and aid of competent, devoted and experienced assistants.

This agonizing search would last from 1926 to 1940, when Rúḥíyyih Khánum began working as his secretary full-time.

Until then, he was essentially alone, single-handedly setting in motion the establishment of the Administrative Order of the Faith of Bahá'u'lláh, and sometimes calling on various family members to lend a hand.

In 1926, Shoghi Effendi invited two eminent Bahá'í lawyers to Haifa to consult with them on several sensitive and highly confidential cases. These Bahá'ís were Mountford Mills and Hippolyte Dreyfus.

Mountfort Mills was an early American Bahá'í from Chicago who served on the Bahá'í Temple Unity and the National Spiritual Assembly of the United States and Canada, was an international lawyer, and Hippolyte Dreyfus, the first French Bahá'í, had a doctorate in law.

One of the cases Shoghi Effendi required their help with was to assert the Bahá'í community’s legal claim to the Most Great House.

Hippolyte and Mountfort Mills used their considerable legal skills to counsel and advise the Iraqi Bahá'ís in the preparation of their files and the presentation of their cases.

Mountfort traveled twice to Iraq for audiences with King Faisal and to plead the Bahá'í community’s case for legal ownership of the Most Great House.

On 14 November 1926, Shoghi Effendi received more terrible news. Iraq’s highest tribunal ruled against the Bahá’ís in the case of the ownership of the House of Bahá’u’lláh.

Shoghi Effendi immediately sent a cable urging all American national and local spiritual assemblies to emphatically protest this glaring injustice by writing or cabling the High Commissioner in Iraq through the British Consular. The Bahá'ís were appealing to the famous British sense of fairness and proving their spiritual claim of ownership to the Most Great House, to them a Holy Place.

Mountford Mills and Hippolyte Dreyfus consulted with the Guardian and together, they decided to bring the case of the Most Great House to the attention of the League of Nations in Geneva. Hippolyte was very familiar with the workings of the organization, and the two Bahá'í lawyers provided support and legal expertise in the drafting of the petition signed by the Iraqi Bahá'ís.

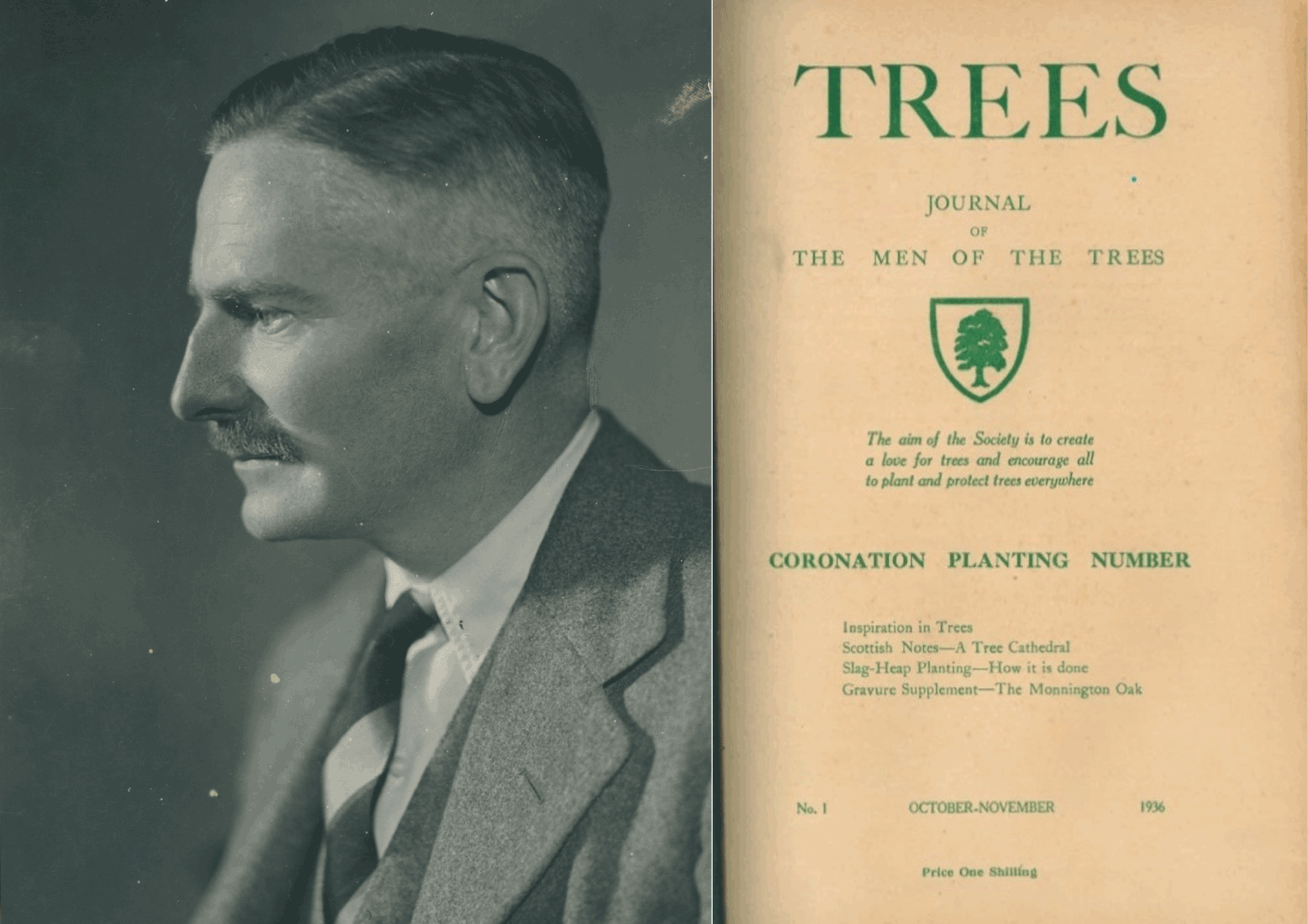

Richard St. Barbe Barker and his publication, the “Journal of the Men of the Trees.” Source: Bahá'í World News Service.

Sir Richard St. Barbe Baker OBE, was an English biologist and botanist, environmental activist and author, who contributed greatly to worldwide reforestation efforts. He worked as a logger in his youth in Saskatchewan, and that was when he became. Convinced that the waste of timber and razing of natural scrub trees was leading to soil degradation. It was the beginning of his lifelong activism to protect the trees of the world. St. Barbe Baker was a vegetarian and a pioneering and leading advocate for a plant-based diet.

After his studies at Cambridge in botany, Richard St. Barbe Baker became a specialist in deforestation, soil-loss problems, and declines in biodiversity. He went to work in Kenya, where he created a tree nursery and developed reforestation with the Kikuyu tribes replanting native Kenyan tree species.

While in Kenya, Richard St. Barbe Baker founded an organization called “Watu wa Miti.” This formed the foundation for what was to become an international organization, the Men of the Trees (a translation of the original name in Swahili), an organization that is still active today as the International Tree Foundation, whose many chapters carry out reforestation internationally.

Richard St. Barbe Baker became a Bahá'í ten days after attending the London conference “Some living religions within the British Empire,” in September/October 1924. Two years later, he attended the First World Forestry Congress in Rome in 1926, then traveled to Palestine, where he set up a chapter of the Men of the Trees there.

One day, in Haifa, St. Barbe Baker went to pay his respects to Shoghi Effendi, who greeted him warmly, and handed him an envelope containing his application for life to the Men of the Trees organization. Shoghi Effendi was the first member of the organization in Palestine.

Shoghi Effendi promised St. Barbe Baker he would do much more than just apply for membership, and it was thanks to Shoghi Effendi’s efforts that and his enthusiastic endorsement, that all the Heads of Religion in Palestine also joined the organization—Muslim, Jews and Christians. Shoghi Effendi and St. Barbe Baker would remain close for. Many years and in 1953, Shoghi Effendi would call on his friend to help the African Bahá'ís attend the 1953 Intercontinental Teaching Conference.

Letter in Persian from the National Spiritual Assembly of Baha’is of the US and Canada to Reza Shah, appealing for justice. Source: Archives of Bahá'í Persecution in Iran. English translation of this letter is available below the images on the webpage provided about.

On 7 April 1926, 12 Bahá'í adults and a 16-month-old baby were savagely martyred in Jahrúm, Persia, a city 160 kilometers southeast of Shíráz. The instigator of the brutal murders was Ismá'íl Khán, Sawlatu'd-Dawlih, a chief of the Qashqa'i tribe, and the Deputy for Jahrúm, who was trying to prevent his defeat in elections, and was looking to boost his popularity.

Fu’ád Rawhani, a Bahá'í in Ṭihrán, described the ferocity and violence of the attack, based on a report he received from the Local Spiritual Assembly of Jahrúm. The murders were carried out on 7 April 1926 by a Siyyid Muḥammad and three others. They first instigated the local population to rise up against the Bahá'ís, and at first, two Bahá'ís were chased and badly beaten. Bahá'ís complained to the authorities, but nothing was done.

The four aggressors beat four more Bahá'ís, beat Bahá'í women and children, nearly pummeled to death any Bahá'í they found in Jahrúm, killing one Bahá'í with an axe and beating his mother, plundering, pillaging, and setting on fire 20 Bahá'í homes. By the end of the day, many Bahá'ís had been wounded, had lost everything they owned, and had become homeless and 12 Bahá'ís had been martyred, including a 16-month-old baby.

The Guardian received a devastating cable from Shíráz the on 11 April 1926, four days after the atrocities had taken place:

Twelve friends in Jahrom martyred agitation may extend elsewhere.

Shoghi Effendi immediately replied, that same day:

Horrified sudden calamity. Suspend activities. Appeal central authorities. Convey relatives tenderest sympathy

The same day, Shoghi Effendi wired Ṭihrán a deeply significant message, rooted in the rich Bahá'í history of victory over crisis, asking the believers in the region to elect their National Assemblies:

I earnestly request all believers Persia Turkistan Caucasus participate whole-heartedly in renewal Spiritual Assemblies election. No true Bahá'í can stand aside. Results should be promptly forwarded Holy Land through central assemblies communicate immediately with every centre. Proceed cautiously. Imploring Divine assistance.

On 12 April 1926, one day after the martyrdoms, the chief instigator was arrested, and Shoghi Effendi sent a cable to the National Spiritual Assembly of Persia, asking them to convey to the Sháh, his profound appreciation for such a swift intervention.

Shoghi Effendi was deeply distressed by the martyrdoms, and asked Bahá'í National Spiritual Assemblies to publicize the event, but refrain from contacting the Persian Government.

Shoghi Effendi was reaching the point where he was too tired to work, and his usually superhuman, unstoppable energy had halted to a slow trickle. He felt he was becoming inefficient, and would only last another month before he had to go to Switzerland to rebuild himself.

In this profoundly afflicted state, Shoghi Effendi still managed to see the situation with the infallible eyes of the Guardian, in a very profound excerpt from a letter he wrote over a month after the massacres, on 21 May 1926:

I feel that with patience, tact, courage and resource we can utilize this development to further the interests and extend the influence of the Cause.

Shoghi Effendi, although exhausted to the point of barely being able to function, had managed to lead a concerted, worldwide media campaign in defense of the oppressed Persian Bahá'í community. The martyrdoms received wide publicity in the foreign press, and Shoghi Effendi constantly and single-handedly directed National Assemblies in their actions with respect to not only the martyrdoms in Jahrúm, but also the case of the Most Great House of Bahá'u'lláh in Bagdad.

Shoghi Effendi was receiving blow after blow, and still remained standing, working, serving, protecting, defending, directing, writing, building, constructing, encouraging.

That was the unassailable strength of the Guardian.

A view of Maraghih, Persia. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

In May 1926, a particularly severe persecution against Bahá'ís erupted in the town of Marághih in Ádhirbáyján, northwestern Persia. The Governor of Marághih suspended all constitutional rights for the Bahá'í community, and this resulted in severe curtailment of the Bahá'í community’s human rights, manifested by:

- Banning Bahá'ís to use the public baths

- Banning Bahá'ís from interacting with Muslim merchants

- Constant abuse of Bahá'ís

- Felling all trees belonging to Bahá'ís

- Withholding water for irrigation of lands owned by Bahá'ís

- Refusing to provide Bahá'ís with drinking water

- Depriving Bahá'ís of recourse to law

- Banning Bahá'ís from properly burying their dead

In a letter dated 11 May 1926, the Guardian expressed his dismay at the persecutions in Marághih, first recounting all these inhuman measures, and adding

Every appeal made by these Bahá’ís on behalf of their brethren, whether living or dead, has been met with cold indifference, with vague promises, and, not infrequently, with severe rebuke and undeserved chastisement.

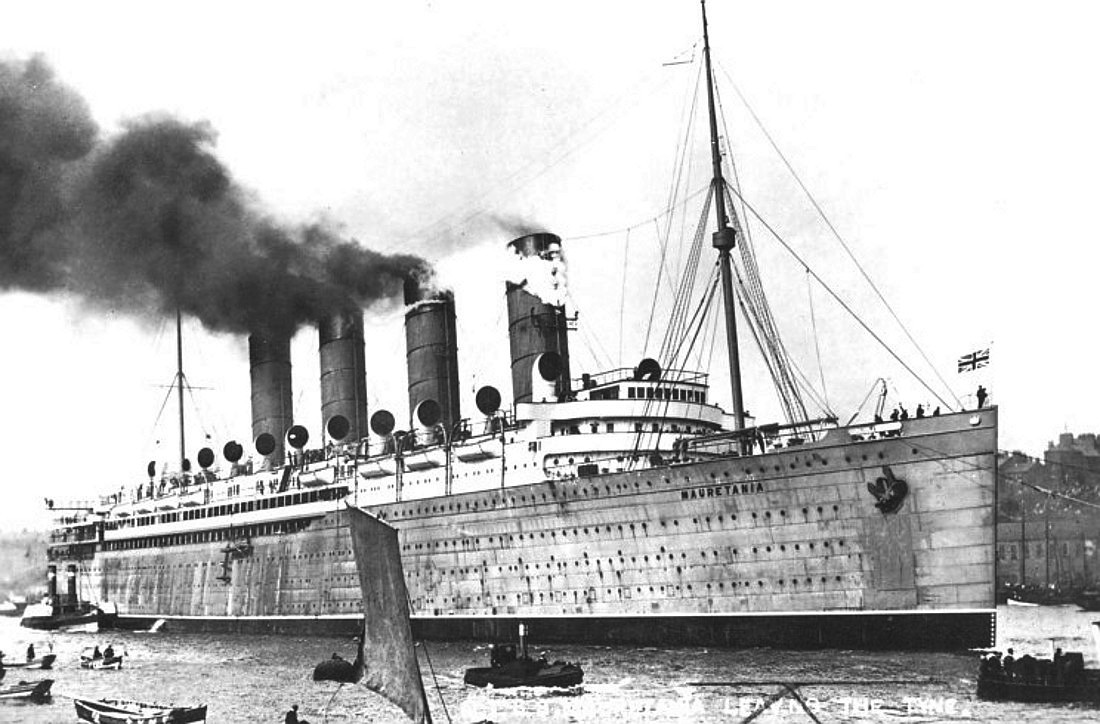

The R.M.S. Mauretania, onboard which Mary Maxwell wrote her parents May and William Sutherland Maxwell on 9 April 1926. Sailing with her were Juliet Thompson and Daisy Smith. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

May Maxwell had such a formidable life-giving relationship with the Covenant that she wanted the two most important people in her life, her husband and her daughter, to forge their one personal relationship with it. When Mary reached the Bahá'í age of maturity and turned 15, May Maxwell encouraged her to begin this lifelong relationship with the Covenant by going on pilgrimage, alone.

Mary set sail from New York in April 1926 on the R.M.S. Mauretania, in the company of two of her best and oldest friends, both New York artist, Daisy Smythe and Juliet Thompson—who was immensely loved by 'Abdu'l-Bahá for her honesty. Mary and May wrote each other constantly, and in one of her letters, May asks Mary to ask the Guardian a very funny question:

Will you also ask Shoghi Effendi if he considers it advisable for you to bring some Persian back with you to teach you Persian in Green Acre this summer, also if he approves of Rahim Yazdí, then cable me.

Mary Maxwell at 16 years old, one year after her second pilgrimage. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

By 12 May 1926, Mary Maxwell was in Haifa. Shoghi Effendi was ill when they arrived, in the same state of utter burn-out that Mary and May had witnessed in 1923 when he had to leave for Switzerland. Mary had arrived at the same time of year that the Guardian, nearly crushed to death by the pressures of his work and the Covenant-breakers, had to leave Haifa in order to survive another year as Guardian. This year, his decline in health was gravely precipitated by the news of Twelve Martyrs of Jahrúm.

May Maxwell was such a well-known and universally-admired Bahá'í that Mary wrote to her say something deeply sweet:

I get at least two extra kisses from everyone just because I am your daughter and they are sending them back to you! Everyone loves you so much.

The Guardian loved May Maxwell so much that his first words to Mary were about her mother, specifically about her health and if she was able to walk, and Munírih Khánum, 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s widow sent May her love. To Munírih Khánum, the Greatest Holy Leaf and the older members of the Holy Family, Mary was the spitting image of May Maxwell when she had first come on pilgrimage in December 1898.

Mary’s only thought in the Shrines was:

How can we cheer our Guardian if we have nothing but tears and sighs, and why do we come to our lord weeping with sorrow for his passing when he is not passed but here with us more so than ever?

William Sutherland Maxwell in 1913. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

On 16 May 1926, Mary had a fascinating conversation with the Guardian which denotes her rare maturity and dedication to the Faith. After dinner, she told Shoghi Effendi that she wished her father—William Sutherland Maxwell—would work a little more for the Cause. Shoghi Effendi replied that her father was a Bahá'í.

Mary said:

Yes, but might work a little more for this Cause.

The Guardian then lovingly joked that he hoped to see the husbands of formidable Bahá'í women—Mr. Maxwell, Mr. Smythe, and Mr. French, the husbands of May Maxwell, Daisy Smythe, and Nellie French—vying with their wives for the Cause, then said:

This may happen! This will happen!

May Maxwell and her dear friend, the artist beloved by 'Abdu'l-Bahá, Juliet Thompson. Source: Bahaimedia.

On 17 May 1926, the day after his conversation about husbands vying for service with their famous Bahá'í wives, Shoghi Effendi wrote a very touching letter to May Maxwell about her daughter, demonstrating two of his most endearing qualities, his compassion and his thoughtfulness:

The visit of your dear daughter, Mary, has reminded me of your sojourn in the Holy Land, the memory of which will ever linger in my mind. I am glad and grateful to learn from her of your good health for as I have already said I greatly value and prize your welfare and happiness realizing that every ounce of your energy and every minute of your time is consecrated to the service of our beloved Cause. Let not the difficulties and disappointments overpower you. Remember my prayers and love for you. My earnest hope is that Mary may follow in your footsteps and render memorable services to the Cause you love so well.

Mary Maxwell at the age of 13/14, a year or so before her second pilgrimage. Source: Source: The Maxwells of Montreal: Middle Years 1923-1937 Late Years 1937-1952. Violette Nakhjavani, Kindle Edition, Location 583.

On the evening of 23 May 1926, Shoghi Effendi sent for Mary Maxwell and gave her very specific advice on her studies and her service. In regards to her learning Persian, the Guardian suggested a good teacher. Regarding her studies, Shoghi Effendi explained to her it was important that she first get a good general education, and then—if her health permitted—study economics, sociology or literature in university. Mary wrote to her mother that she wanted to study all three. Her spontaneity and trademark frankness were a lifelong trait, even in Rúḥíyyih Khánum.

Mary Maxwell spent three or four days in Tiberias and returned to Haifa for the Commemoration of the Ascension of Bahá'u'lláh, but it is unclear what date she left.

At the young age of 15, she was already utterly dedicated to serving the Guardian and was deeply humbled by his station, telling her mother:

If I could be an insect and crawl around after Shoghi Effendi I would be a very happy being.

Her pilgrimage in 1926 completely recreated Mary Maxwell. She would never be the same person again, something in her heart, her mind, and her soul had shifted permanently into their rightful position. After her pilgrimage, Mary would be immoveable in the Covenant. Shoghi Effendi had become her sun, and she would orbit in his sphere, take her strength from his guidance, and serve the Faith to please him.

The next time Mary Maxwell would see Shoghi Effendi would be on 12 January 1937, two and a half months before they were married.

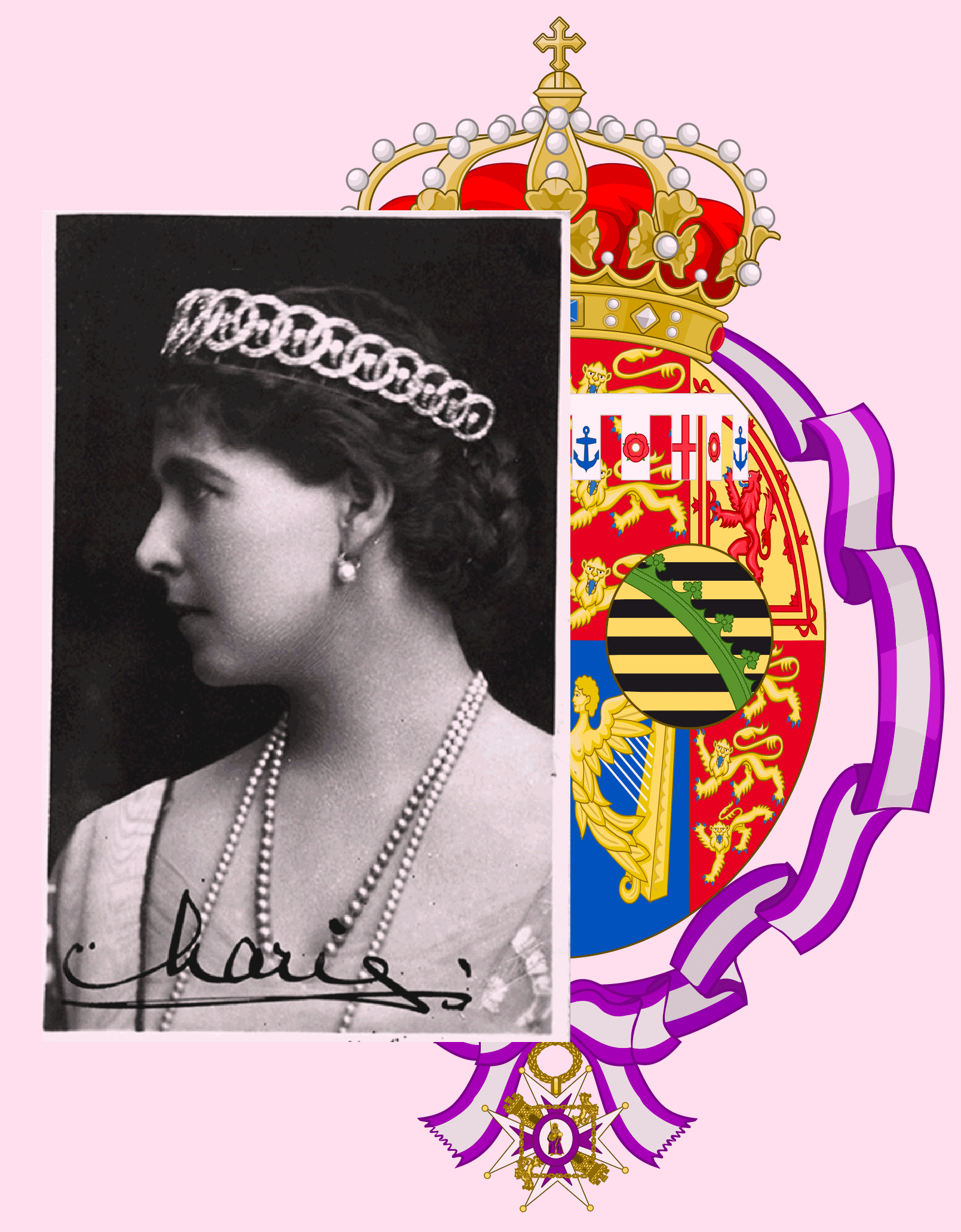

Queen Marie of Romania – Signed photograph. Source: Bahá'ís of the United States. In the background: Coat of Arms of Marie of Saxe-Coburg, Queen of Romania (Order of María Luisa). Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Shoghi Effendi was literally engulfed with troubles, when the first of Queen Marie of Romania’s open letters was published, on 4 May 1926, by the Toronto Daily Star. Queen Marie would publish two more letters on 27 and 28 September 1926.

Queen Marie was, at the time, visiting the United States and Canada, and three of her open letters were published and widely circulated. It was the largest and most spectacular publicity the Bahá'í Faith had ever received.

Below is Queen Marie’s first open letter, and all three can be read in full in the Bahá'í World, Volume 2:

A woman brought me the other day a Book. I spell it with a capital letter because it is a glorious Book of love and goodness, strength and beauty.

She gave it to me because she had learned I was in grief and sadness and wanted to help… She put it into my hands saying: “You seem to live up to His teachings.” And when I opened the Book I saw it was the word of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, prophet of love and kindness, and of his father the great teacher of international good-will and understanding—of a religion which links all creeds.

Their writings are a great cry toward peace, reaching beyond all limits of frontiers, above all dissension about rites and dogmas. It is a religion based upon the inner spirit of God, upon that great, not-to-be-overcome verity that God is love, meaning just that. It teaches that all hatreds, intrigues, suspicions, evil words, all aggressive patriotism even, are outside the one essential law of God, and that special beliefs are but surface things whereas the heart that beats with divine love knows no tribe nor race.

It is a wondrous Message that Bahá’u’lláh and his son ‘Abdu’l-Bahá have given us. They have not set it up aggressively knowing that the germ of eternal truth which lies at its core cannot but take root and spread.

There is only one great verity in it: Love, the mainspring of every energy, tolerance towards each other, desire of understanding each other, knowing each other, helping each other, forgiving each other.

It is Christ’s Message taken up anew, in the same words almost, but adapted to the thousand years and more difference that lies between the year one and today. No man could fail to be better because of this Book.

I commend it to you all. If ever the name of Bahá’u’lláh or ‘Abdu’l-Bahá comes to your attention, do not put their writings from you. Search out their Books, and let their glorious, peace-bringing, love-creating words and lessons sink into your hearts as they have into mine.

One’s busy day may seem too full for religion. Or one may have a religion that satisfies. But the teachings of these gentle, wise and kindly men are compatible with all religion, and with no religion.

Seek them, and be the happier.

BY MARIE, QUEEN OF RUMANIA.

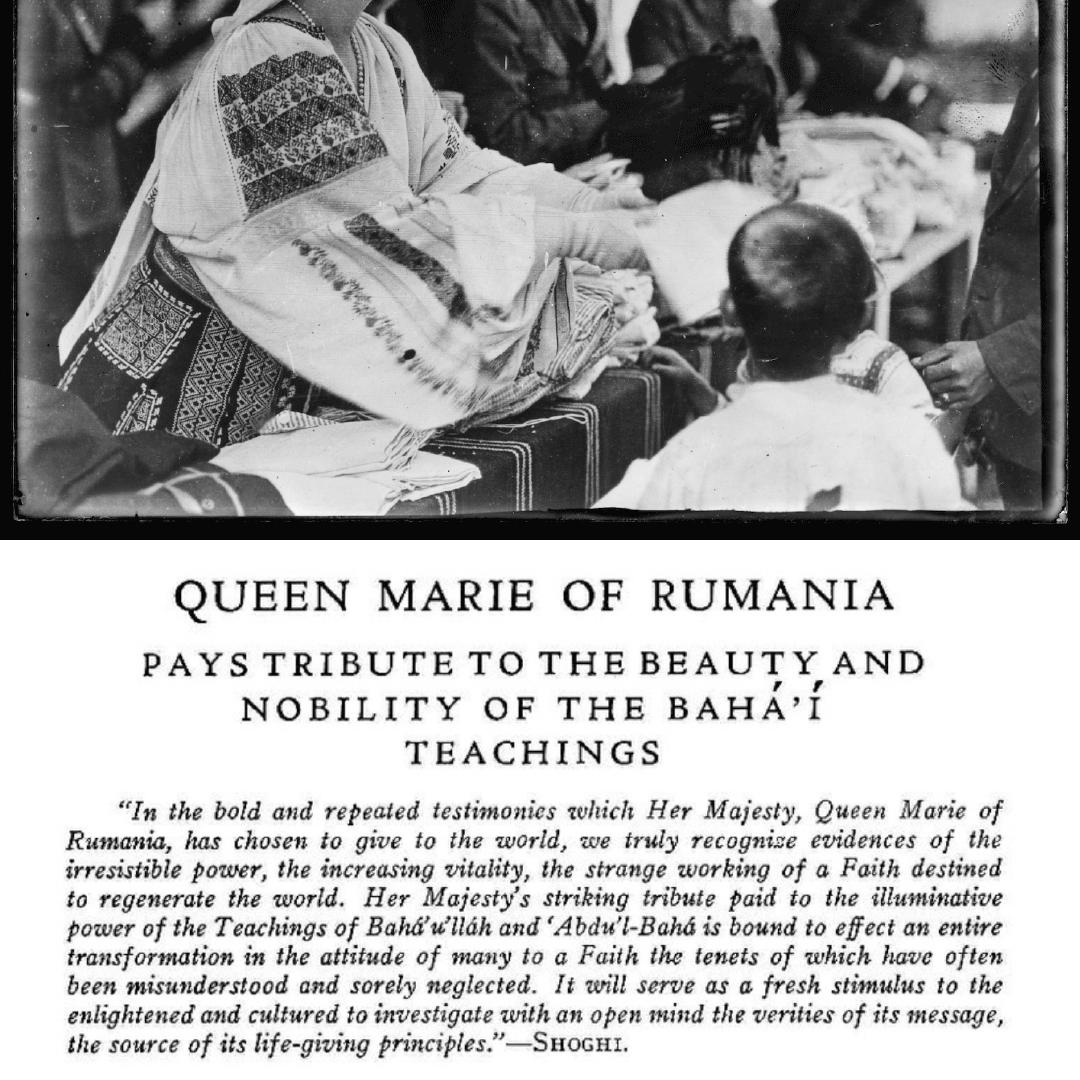

Top image: Queen Marie of Romania dressed in the national Romanian garb, distributing American Red Cross supplies to the needy children and women of Bucharest. . Source: Library of Congress. Bottom image: Shoghi Effendi’s response printed in The Bahá'í World Volume 2 page 173.

Queen Marie’s tributes to the Faith in her open letters were published in over 2oo newspapers and constituted the most spectacular publicity the Faith had ever received.

In a confidential letter he wrote on 29 May the Guardian referred to this moment as the “most astonishing and highly significant event in the progress of the Caus.”

In September 1926 Shoghi Effendi, expressed great joy at the Queen’s public declaration of Faith:

I am glad to share with you the contents of the Queen of Rumania's answer to my letter. I think it is a remarkable letter, beyond our highest expectations. The change that has been effected in her, her outspoken manner, her penetrating testimony and courageous stand are indeed eloquent and convincing proof of the all-conquering Spirit of God's living Faith and the magnificent services you are rendering to His Cause.

This is how Shoghi Effendi paid tribute to Queen Marie’s open letters about the Bahá'í Faith, in a letter dated 29 October 1926, addressed to the Bahá'ís of the West:

In the bold and repeated testimonies which Her Majesty, Queen Marie of Rumania, has chosen to give to the world, we truly recognize evidences of the irresistible power, the increasing vitality, the strange working of a Faith destined to regenerate the world. Her Majesty’s striking tribute paid to the illuminative power of the Teachings of Bahá’u’lláh and ‘Abdu’l-Bahá is bound to effect an entire transformation in the attitude of many to a Faith the tenets of which have often been misunderstood and sorely neglected. It will serve as a fresh stimulus to the enlightened and cultured to investigate with an open mind the verities of its message, the source of its life-giving principles.

Martha Root. Source: Bahaipedia.

Martha Root was a journalist from a distinguished American family. She had met 'Abdu'l-Bahá in 1912 when He was visiting the United States, and was one of the very first people to rise up in 1919 after He revealed the Tablets of the Divine Plan.

From the moment he became the Guardian, Martha Root included Shoghi Effendi as a partner in all her travel-teaching and proclamation, including the highlight of her life, the conversion of Queen Marie of Romania.

The relationship between the Guardian and Martha Root was warm and deeply spiritual. Shoghi Effendi not only respected and admired Martha, but he felt profound spiritual love for this tireless teacher, who never once let him down. In 1926, Shoghi Effendi wrote these deeply touching lines to her, which attest to the depth of their friendship:

…write me fully and frequently for I yearn to hear of your activities and of every detail of your achievements. Assuring you of my boundless love for you…

Martha Root was one of the rare people who constantly and repeatedly brought the Guardian joy and encouragement. Shoghi Effendi himself attested to this in a letter he sent Martha on 10 July 1926:

Your letters…have given me strength, joy and encouragement at a time when I felt depressed, tired and disheartened.

Shoghi Effendi was very honest with his admiration of Martha Root, even once telling her that:

…Generations yet unborn will exult in the memory of one who has so energetically, so swiftly and beautifully paved the way for the universal recognition of the Faith of Bahá'u'lláh.

Martha Root was a deeply obedient, fully-enkindled servant of the Guardian, asked for his advice constantly, and always followed his instructions. In this way, Shoghi Effendi was able to make use of Martha’s considerable talents in fields as varied as the defense of the Faith, teaching and proclamation, as his representatives to international conferences, and to present his greetings or sympathies to heads of State, such as Queen Marie of Romania, President Hoover of the United States, and His Imperial Majesty the Emperor of Japan.

“The top of the mountain”: Shoghi Effendi—on the right—summitting one of the Swiss Alps with his guide. Source: The Priceless Pearl.

By May 1926, Shoghi Effendi was worn out beyond imagination. Already, in February, three months before, Shoghi Effendi had written to a Bahá'í stating:

I am submerged in a sea of activities, anxieties and preoccupations. My mind is extremely tired and I feel I am becoming inefficient and slow due to this mental fatigue.

Over the next three months, Shoghi Effendi worsened, and his condition became so acute that he was forced to leave the Holy Land for a period of rest. When Shoghi Effendi was leaving for his annual pilgrimage to the Swiss Alps, he received a letter from his dear friend Hippolyte Dreyfus. Shoghi Effendi replied to him later writing eloquently about how much he needed the respite from the stress of his work:

In the fastnesses and recesses of its alluring mountains I shall try to forget the atrocious vexations which have afflicted me for so long...It is a matter which I greatly deplore, that in my present state of health, I feel the least inclined to, and even incapable of, any serious discussion on these vital problems with which I am confronted and with which you are already familiar. The atmosphere in Haifa is intolerable and a radical change is impractical. The transference of my work to any other centre is unthinkable, undesirable and in the opinion of many justly scandalous...I cannot express myself more adequately than I have for my memory has greatly suffered.

Shoghi Effendi left Haifa for Switzerland in late May 1926, shortly after the commemoration of the Ascension of Bahá'u'lláh, and in August he was joined by his mother, Ḍíyá‘íyyih Khánum, and one of his sisters. They returned to the Holy Land on 15 October 1926.

The Western Pilgrim House in 1925. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

After the end of World War I, large numbers of western pilgrim began flooding into the Holy Land to see 'Abdu'l-Bahá and perform pilgrimage at the Shrines. This was the first opportunity the masses of Bahá'ís who had met 'Abdu'l-Bahá during His Journeys to the West to see the Master again, and they came in large numbers.

There was already, at the time, an adequate eastern Pilgrim House for the Bahá'ís arriving from Persia, Iraq, Egypt, Turkmenistan, Pakistan, and Turkey, among many other places, but the small stone building across from the Master’s House was no longer a befitting and adequate pilgrim house for the American and European Bahá'ís.

'Abdu'l-Bahá needed a western Pilgrim House.

A Persian Bahá’í from Egypt—Ḥájí ‘Abdu’l-Javád Iṣfahání—donated a plot of land across from the House of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, where Bahá'u'lláh had once pitched His tent, and in November 1919, William Henry Randall asked 'Abdu'l-Bahá for the privilege of contributing money for the building of the western Pilgrim House in November 1919. ‘Abdu'l-Bahá graciously accepted Henry Randall’s offer.

'Abdu'l-Bahá had plans drawn for the building but He didn’t have enough money to continue building. Shoghi Effendi picked up where his Grandfather had left off and began construction on the western Pilgrim House on 9 April 1922, but due to lack of funds, he, too, had to halt the project.

In December 1925, the Guardian expressed his "heartfelt and abiding gratitude" to Amelia Collins and seven others Bahá'ís who had donated the necessary funds to complete the western Pilgrim House construction project, and the western Pilgrim House at 10 Haparsim, across the street from the Master’s House, was completed in 1926.

In 1927, Shoghi Effendi added 8 bedroom suites to the building. Shoghi Effendi adopted the custom of taking the evening meal with the western pilgrims in the dining room on the lower level. He usually met with the eastern pilgrims in the eastern Pilgrim House, a stone’s throw from the Shrine of the Báb.

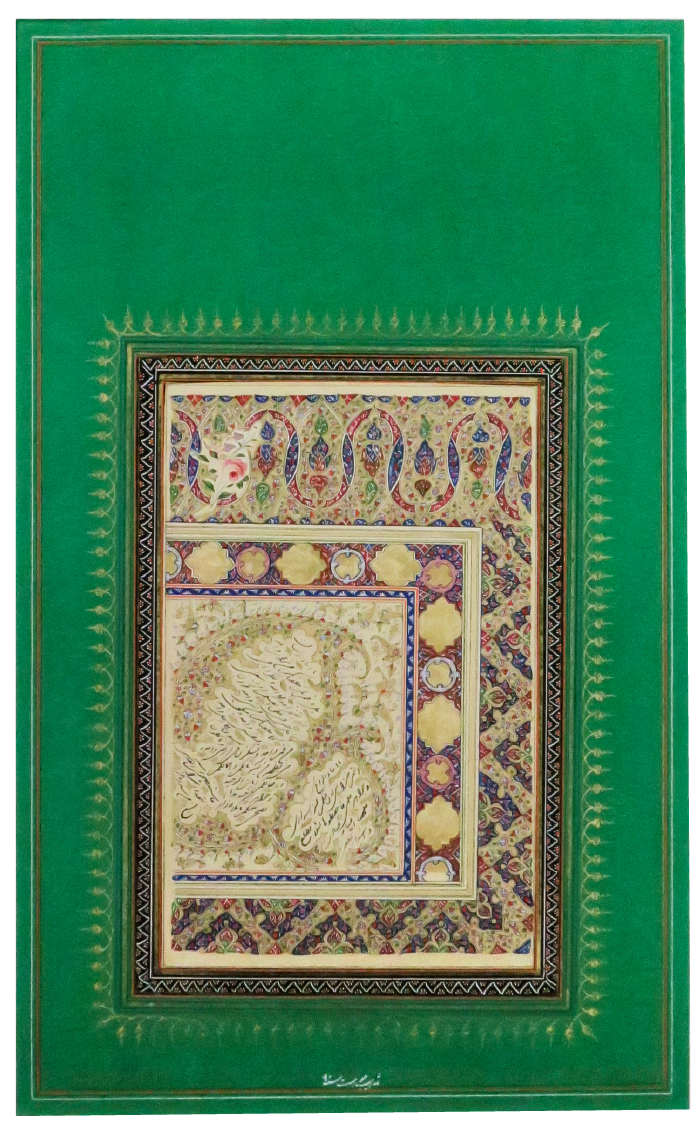

Verses from The Hidden Words by Bahá’u’lláh, in His own handwriting. © Baha’i International Community.

Bahá'u'lláh revealed the Hidden Words around 1858 in Baghdad. He stated that this was The Hidden Book of Fáṭimih of Islamic tradition, the words of consolation spoken to the grieving daughter of the Prophet Muḥammad.

Shoghi Effendi had been working on a translation of Bahá'u'lláh’s Hidden Words since his Oxford days, as far back as January – March 1921. It was a work he described as an “outstanding contribution… to the world’s religious literature,” a work “occupying a position of unsurpassed pre-eminence among the ethical Writings of the Author of the Bahá’í Dispensation,” and a “collection of gem-like utterances.” Shoghi Effendi stated that the Hidden Words constituted a “dynamic spiritual leaven cast into the life of the world for the reorientation of the minds of men, the edification of their souls and the rectification of their conduct.”

Shoghi Effendi sent a first translation to the Bahá'ís of the United States and Canada in February 1923, and revised the translation two years later in January 1925. Shoghi Effendi’s final translation of the Hidden Words, however, was the one he made from 27 February 1926 until March 1927, with the assistance of first Ethel Rosenberg and then George Townshend.

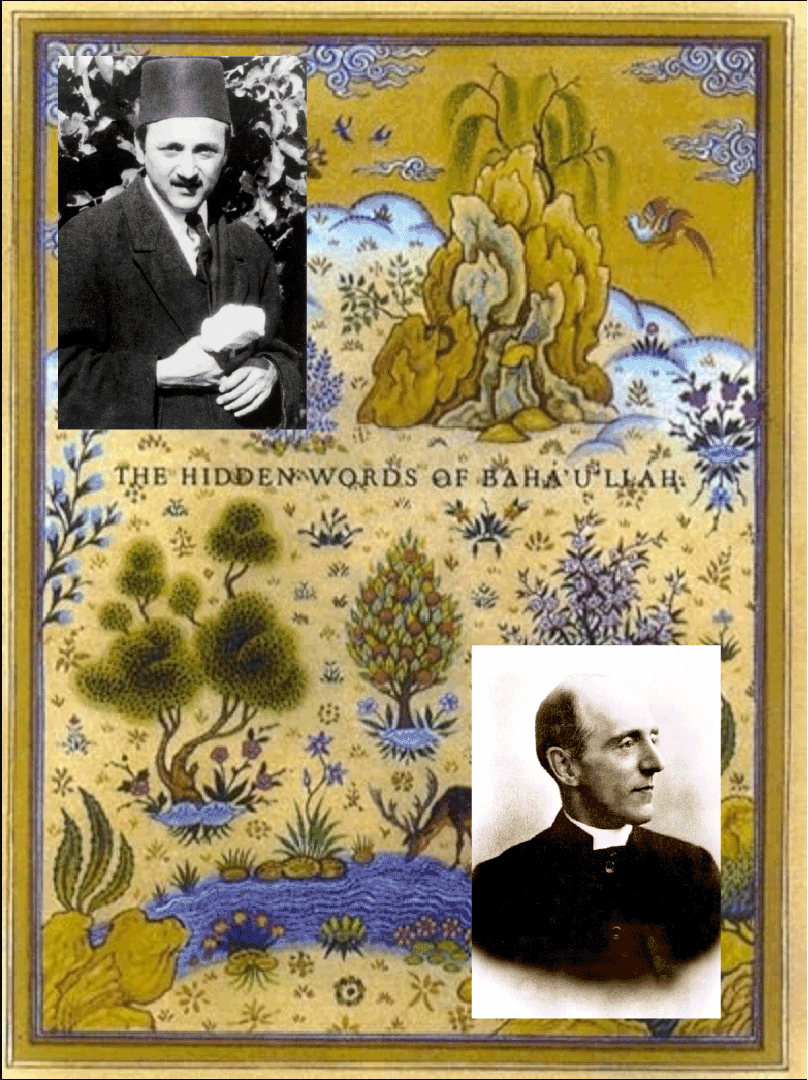

Shoghi Effendi (Bahá'í Media Bank) and George Townshend (Uplifting Words), a legendary literary partnership. Background: Modern edition of The Hidden Words by Bahá'u'lláh.

Shoghi Effendi’s and George Townshend’s 18-year literary partnership began on 27 February 1926 with a letter from George Townshend. He had heard that Shoghi Effendi had invited Ethel Rosenberg to Haifa to help him with translation and joyfully offered his services. George Townshend was a well-known talented Irish writer and former Anglican clergyman. He was a phenomenally talented writer with a real gift for eloquence. In his letter, George Townshend gave examples of difficulties translating in English, such as the objective and subjective possessive cases and gave examples of improved translations.

When Shoghi Effendi received his letter, he was exultant. George had been the literary partner he had been looking for and he replied on 28 March 1926 with the first batch of translations of the Hidden Words.

When George returned the last pages of the Hidden Words to Shoghi Effendi on 7 March 1927, he included a handwritten note:

There is a note, a music, a voice in the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh, even in translations, which never was heard in English literature before and which has such power that it seems to shake the air as one reads. If other proof were lacking, this Mighty Voice would be proof enough. Literary people all must feel it.

Some hidden words in Shoghi Effendi’s exquisite calligraphy. Source: Bahá'í Sacred Relics.

The translation work done by Shoghi Effendi and the finishing touches brought by George Townshend consummated themselves in a literary masterpiece, the Hidden Words, that never once reads as if it had been translated into English from Persian and Arabic.

This was also the impression of Shoghi Effendi’s former teacher in Beirut, Bayard Dodge who wrote to him, thanking him for a copy of the Hidden Words:

I realize how exceedingly difficult it is to translate beautiful Oriental thoughts into English and I congratulate you for the quality of the language which you have used.

This Hidden Word, number 3 from the Arabic, is just one of 153 such gems of brevity and mystical enlightenment in the matchless translation of Shoghi Effendi:

O SON OF MAN! Veiled in My immemorial being and in the ancient eternity of My essence, I knew My love for thee; therefore I created thee, have engraved on thee Mine image and revealed to thee My beauty.

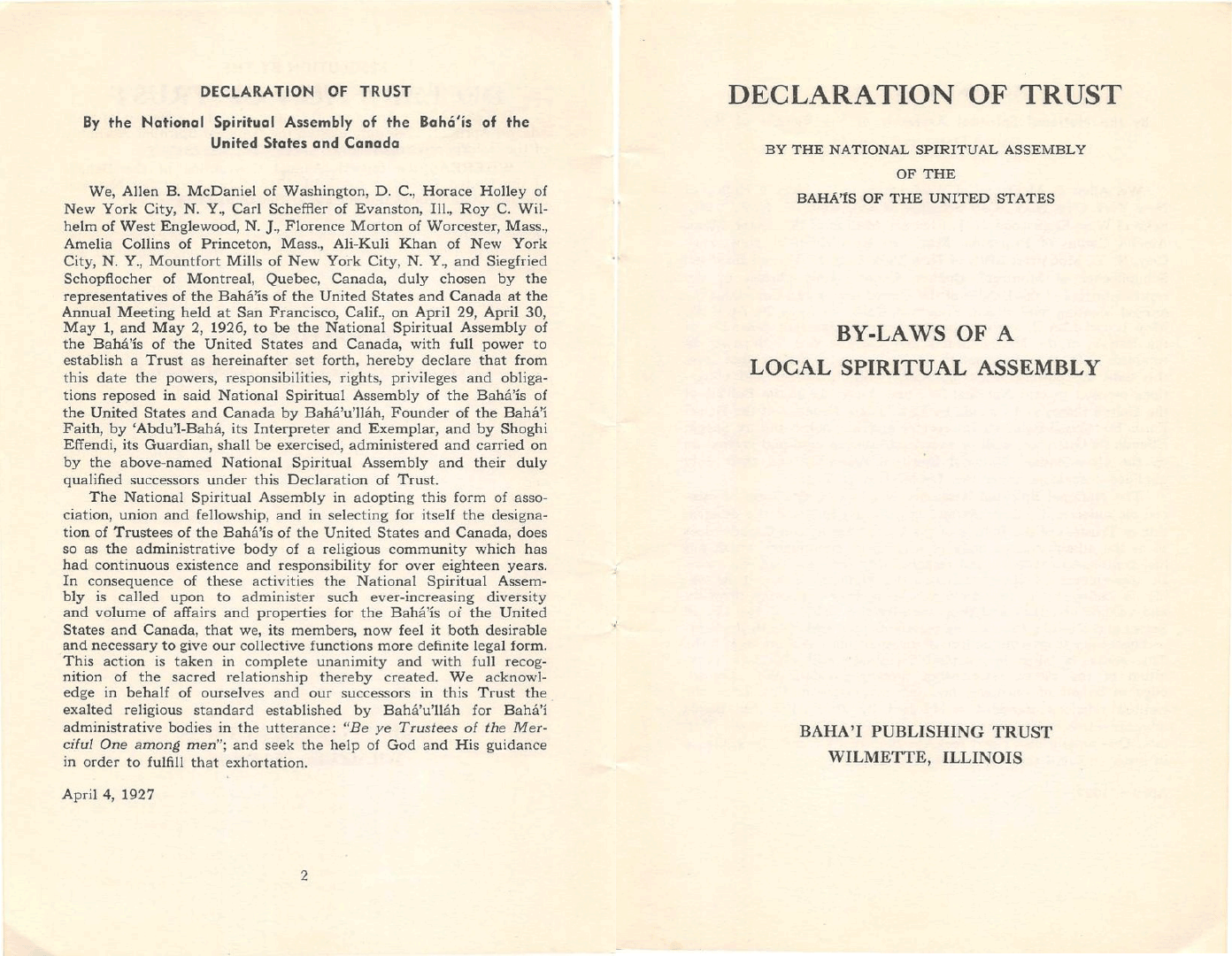

Declaration of Trust by the National Spiritual Assembly of the United States. Source: Bahá'í Works.

One of the great milestones in the Formative Age of Bahá'í history was the drafting and adoption of a Bahá'í National Constitution in 1927, five years into Shoghi Effendi’s ministry.

In April/May 1926, Mountfort Mills, an early American Bahá'í from Chicago and an international lawyer—elected to the first National Spiritual Assembly of the United States as its Chairman in 1923—drew up a draft of a National Constitution for the Bahá'ís of the United States and Canada, a Declaration of Trust for and by-laws.

The National Spiritual Assembly adopted the National Constitution in April 1927 and the Guardian reviewed them.

On 18 October 1927, the Guardian congratulated the National Spiritual Assembly on the work done by “that highly-talented, much-loved servant of Bahá’u’lláh, Mountfort Mills,” and asked them to send a copy of the documents to all National Spiritual Assemblies: