Written and illustrated by Violetta Zein

This part covers the life of Shoghi Effendi from the age of 25 in 1922 to the age of 27 in 1924.

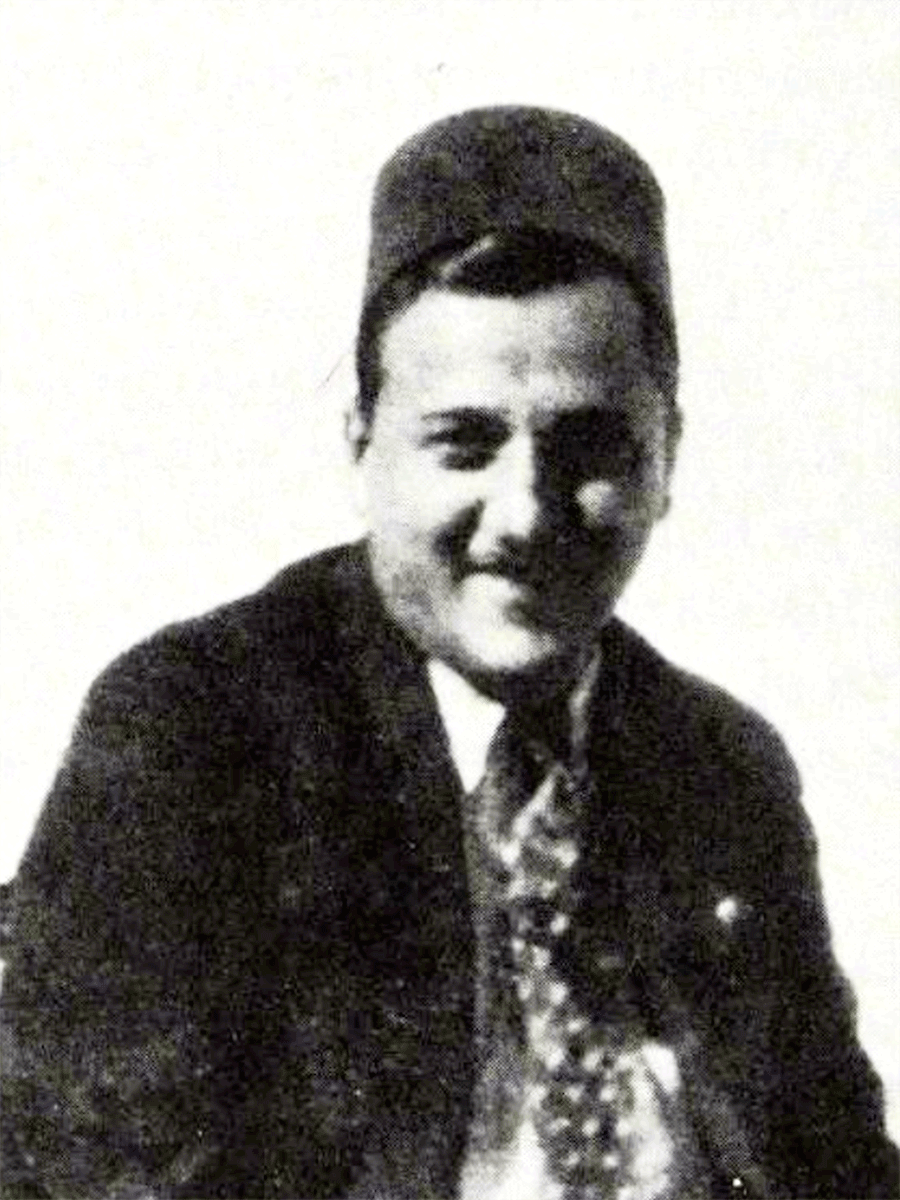

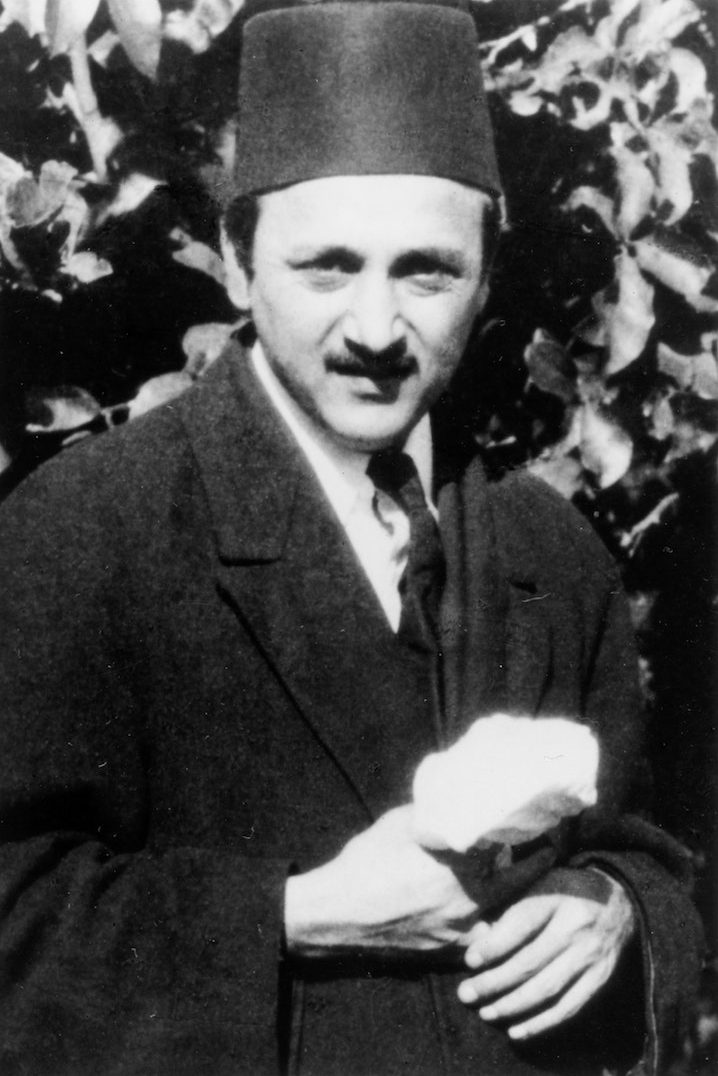

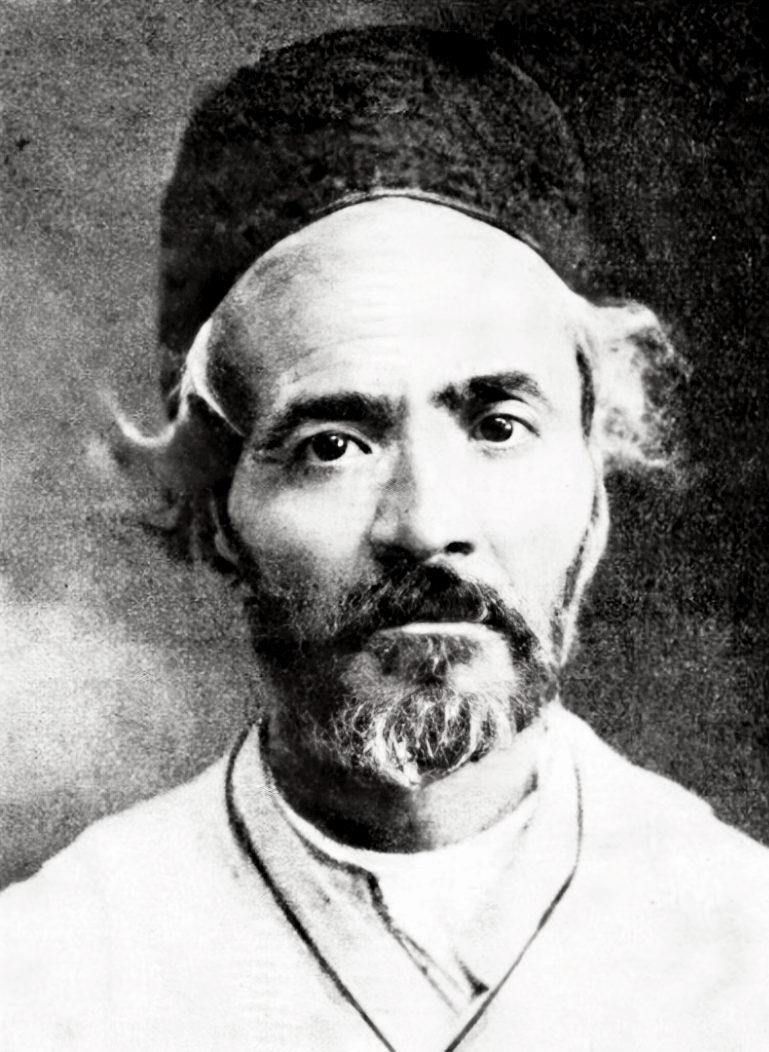

The Guardian: photograph of Shoghi Effendi. Source: The Priceless Pearl, between pages 120 and 121.

Shoghi Effendi was now the Guardian. Guardian is not as strong a word in English as the Arabic original term is. In the original Arabic, "Valíyy-i-Amru'lláh" is a beautiful, precise, evocative term which means at once Defender of the Faith, Leader, and Commander-in-Chief.

'Abdu'l-Bahá’s Will and Testament had placed on Shoghi Effendi the same responsibility which Bahá'u'lláh’s Will and Testament had placed on the Master after His Ascension on 29 May 1892.

This responsibility could not be shared with another person, nor with a body of believers.

It was Shoghi Effendi’s to carry alone, as it had been 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s to carry alone.

In a letter Shoghi Effendi wrote in February 1922, to a nephew of 'Abdu'l-Bahá who had risen up against 'Abdu'l-Bahá, he clearly shows he already understood the full picture of his new station, received in the middle of his sorrows, cares and afflictions:

…the pain, nay the anguish of His bereavement is so overwhelming, the burden of responsibility He has placed on my feeble and my youthful shoulders is so overwhelming…you will also see what a great responsibility He has placed on me which nothing short of the creative power of His word can help me to face…

One month later on 19 March 1922,, Shoghi Effendi unequivocally stated his position in a letter to one of his professors at the American University in Beirut:

Replying to your question as to whether I have been officially designated to represent the Bahá'í Community: 'Abdu'l-Bahá in his testament has appointed me to be the head of the universal council which is to be duly elected by national councils representative of the followers of Bahá'u'lláh in different countries…

After he became the Guardian, Shoghi Effendi made two simple changes to his wardrobe. He stopped wearing the Turkish-style fez he had worn as a student, and begin wearing a black Persian-style fez, and he adopted a simple knee-length coat.

Background photo of an intricate ceiling in Iṣfahán by Nastaran Taghipour on Unsplash.

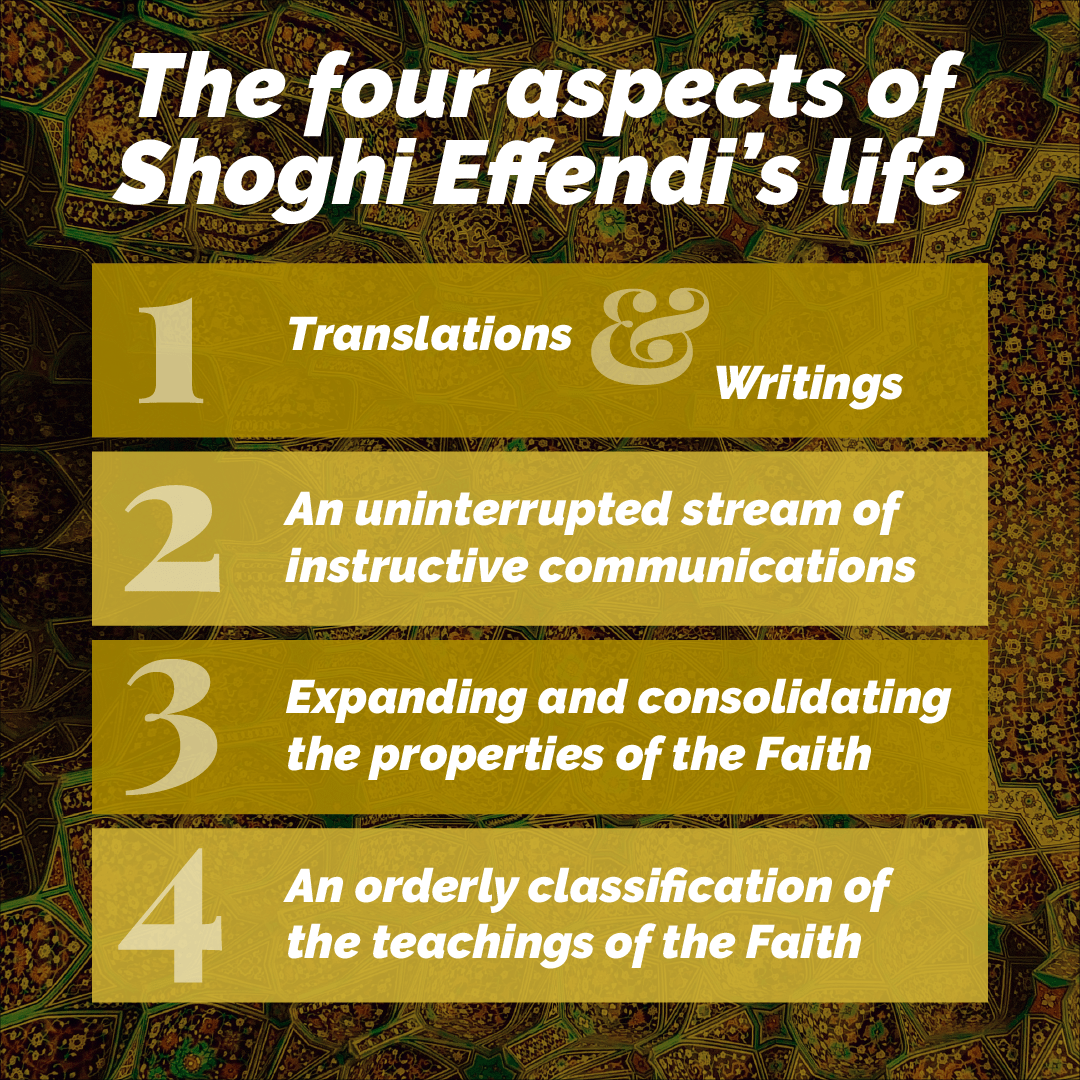

This section, as an homage to Hand of the Cause Amatu’l-Bahá Ruḥíyyíh Khánum, will contain only her analysis of the four major aspects of the life work of the Guardian. They have been broken up into paragraphs for ease of reading:

The life work of Shoghi Effendi might well be divided into four major aspects:

his translations of the Words of Bahá'u'lláh, the Bab, 'Abdu'l-Bahá and Nabil's narrative; his own writings such as the history of a century, published as God Passes By,

as well as an uninterrupted stream of instructive communications from his pen which pointed out to the believers the significance, the time and the method of the building up of their administrative institutions;

an unremitting programme to expand and consolidate the material assets of a world-wide Faith, which not only involved the completion, erection or beautification of the Bahá'í Holy Places at the World Centre but the construction of Houses of Worship and the acquisition of national and local headquarters and endowments in various countries throughout the East and West;

and, above all, a masterly orientation of thought towards the concepts enshrined in the teachings of the Faith and the orderly classification of those teachings into what might well be described as a vast panoramic view of the meaning, implications, destiny and purpose of the religion of Bahá'u'lláh, indeed of religious truth itself in its portrayal of man as the apogee of God's creation, evolving towards the consummation of his development - the establishment of the Kingdom of God on earth.

Background photo of an intricately designed rug by Meriç Dağlı on Unsplash.

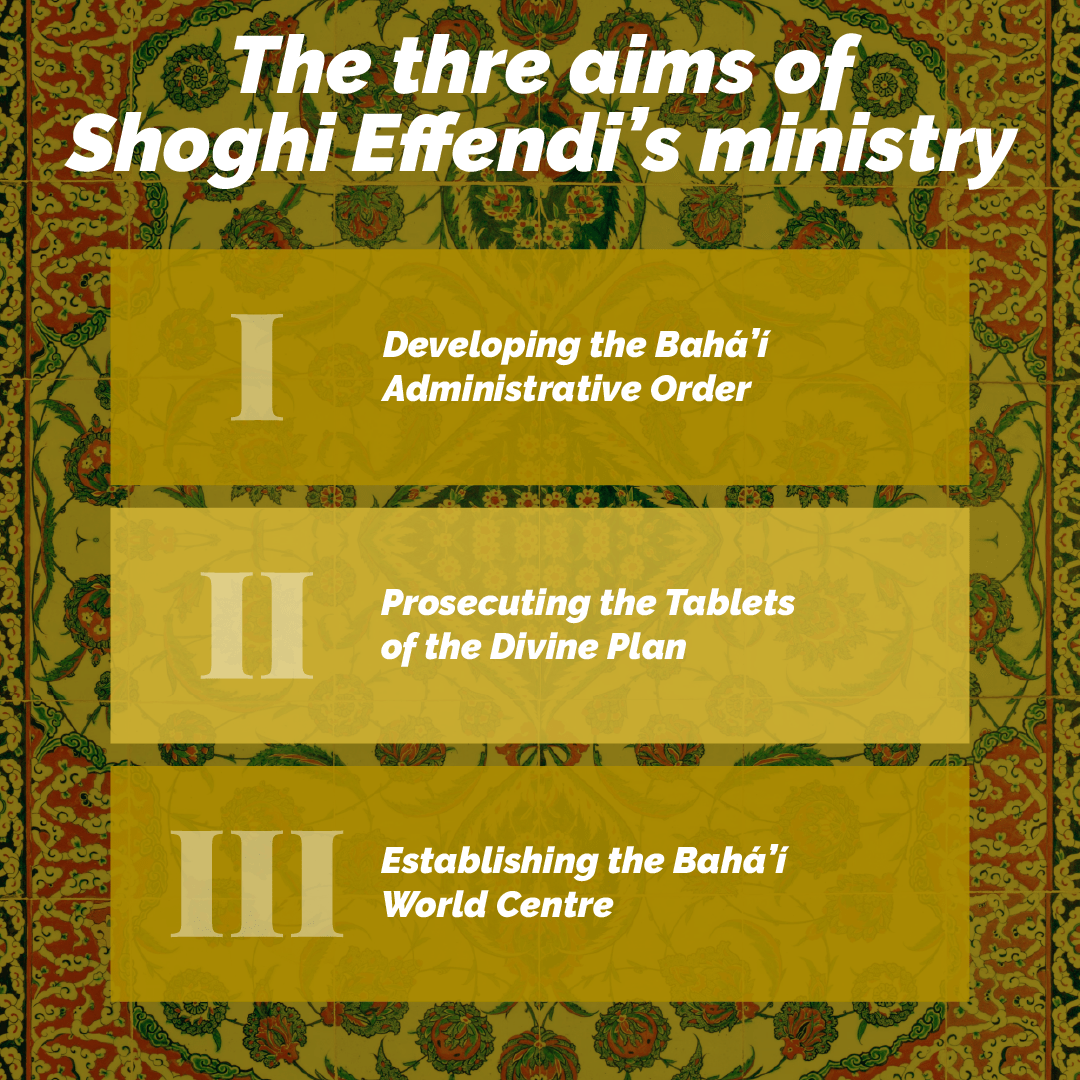

The Guardian told Hand of the Cause Leroy Ioas that he saw his Guardianship as having three main aims:

- One was to build up the Administrative Order of the Cause of Bahá'u'lláh

- Two was to prosecute 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s Tablets of the Divine Plan and spread the teachings of the Cause throughout the entire earth

- And third, to build the World Center of the Bahá'í Faith in the Holy Land

These were the three self-imposed aims that dominated the Guardian’s ministry, and directed both his life and activities.

It should be remembered that, at the outset of His ministry, 'Abdu'l-Bahá also set Himself main goals for His own ministry:

- The establishment of the Faith in America

- The erection of the first Bahá'í House of Worship in ‘Ishqábád, Turkmenistan

- The construction of the Shrine of the Báb on Mount Carmel and the interment of His remains

“First laugh”: An undated photograph of Shoghi Effendi smiling, wearing his signature black fez, possibly before he became the Guardian. Source: Blessings Beyond Measure, ‘Alí Yazdí, page 84.

John and Louise Bosch had arrived on pilgrimage on 13 November 1921 and had lived through the Ascension and the funeral of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, and the reading of His Will and Testament. Before leaving Haifa, Louise wanted to buy the same regular eastern clothes the women of the Holy Family wore—as a show of respect on her part to the family.

Once she had worn her eastern outfit, the women of the Holy Family led Louise to a room where women were praying and one of the Guardian’s aunts told Louise:

You must go and see Shoghi Effendi.

Now that she was going to see the Guardian, Louise felt like a child playing dress-up, and she entered Shoghi Effendi’s room, standing about 1 meter away from his bed. Shoghi Effendi sat up in bed, and realizing he didn’t know who he was looking at under the veil, Louise couldn’t contain her laughter and Shoghi Effendi recognized her, and said:

Oh, it’s Mrs. Bosch.

He pointed to her shoes—that was how he had recognized her. Shoghi Effendi, Louise and one of Shoghi Effendi’s aunts laughed a little over the incident and Shoghi Effendi’s aunt told Louise that was the first time Shoghi Effendi had laughed since he had arrived, almost a month ago, on 29 December 1921.

John and Louise departed, after a two-month pilgrimage on 17 January 1922.

John and Louise went to see Shoghi Effendi to say goodbye, and the Guardian’s last words to them as they left were:

Tell the friends, time will prove that there has been no mistake.

When ‘Alí Yazdí learned the devastating news of 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s Ascension, he was studying at UC Berkley. His own words in his memoirs show the extent of the shock that overwhelmed him and the worldwide community of faithful Bahá'ís:

It is strange, but we never thought that ‘Abdu’l-Bahá would die. Though He Himself alluded to His passing, our minds had not, could not, accept the possibility.

‘Alí Yazdí was devoted to Shoghi Effendi, and his first thought, when he heard the news, despite his overwhelming grief, was to write to his father Ḥájí Muḥammad Yazdí in Haifa expressing his grief, his affection, and his concern for Shoghi Effendi.

It was the Guardian himself who replied to ‘Alí Yazdí’s letter, his first letter to his old friend ‘Alí as Guardian of the Cause.

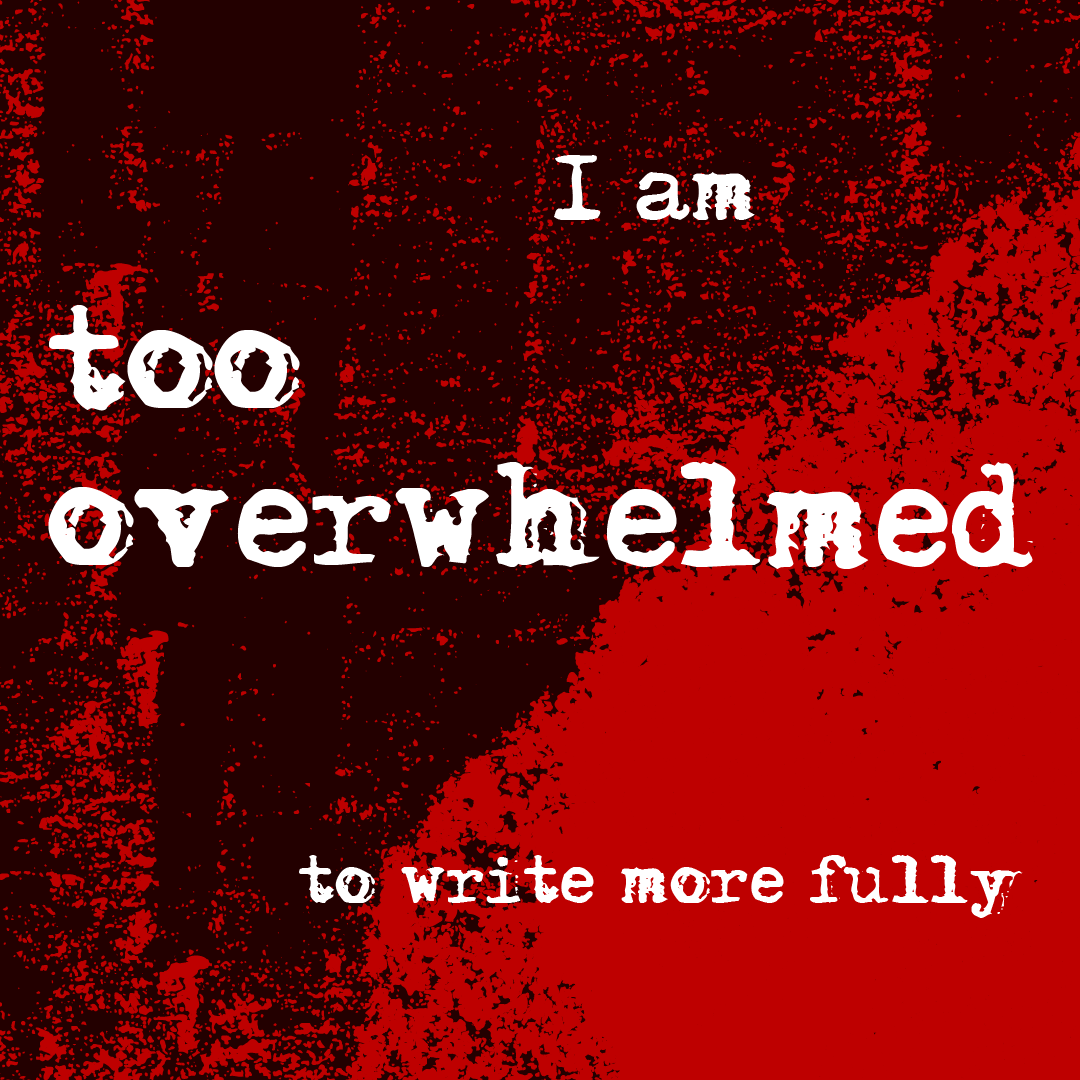

My dearest brother:

The touching letter you had written to your dear father has been such a relief and comfort to me and to those who have perused it. In the midst of our sorrows, one ray of hope gives us the solace and peace that the world cannot give—namely, His sure and repeated promise that He will send souls that shall gloriously promote His Cause after Him. My dear brother! The pure faith, the ardor and the services of your father, I am sure, as well as your own noble wish, will make of you an efficient and energetic servant in His Cause, and I assure you of my prayers at His hallowed Shrine, that whatever you do, whatever you acquire may in the near future be wholly and directly put to the service of His Cause.

I am too overwhelmed to write more fully, but I assure you of my prayers for you, my attachment to you, and my fervent hope that we shall both co-operate to the very last, in our servitude at His Holy Threshold.

The bereaved Holy Leaves remember you with tenderness and hope and wish you a bright future wherever you may be.

Yours in His Love and Service

Shoghi

The Guardian had the thoughtfulness of enclosing in his letter to ‘Alí Yazdí an envelope on which he had penned:

Rose petals that have been laid upon His Sacred Threshold.

‘Alí Yazdí would not see Shoghi Effendi again until 7 years from then, in 1928, when he arrived on pilgrimage with his wife Marion.

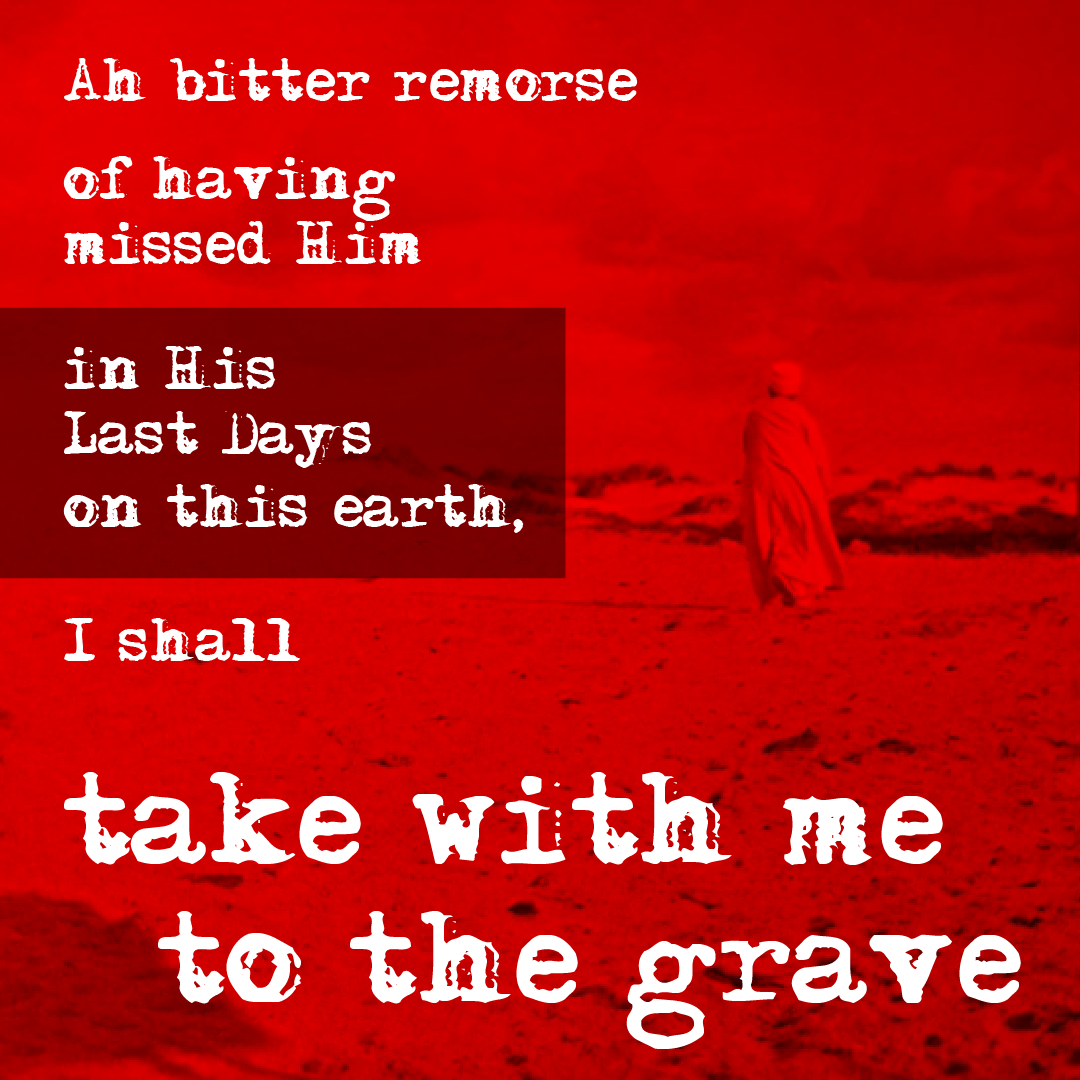

By February 1922, a little over two months after 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s Ascension, Shoghi Effendi was beginning to feel deep grief, and remorse at having missed seeing his grandfather alive one last time.

He wrote to a distant cousin:

Ah bitter remorse of having missed Him - in His Last Days - on this earth, I shall take with me to the grave no matter what I may do for Him in future, no matter to what extent my studies in England will repay his wondrous love for me.

Mrs. Whyte, whom both Shoghi Effendi and 'Abdu'l-Bahá had visited in Scotland, had been impressed with Shoghi Effendi since he was a nine-year-old boy prostrating his forehead at the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh.

She became a close friend of Shoghi Effendi’s and was able to offer him comfort in this devastating time. Her letters had moved Shoghi Effendi to tears, of his own admission. In his response to his Scottish friend on 6 February 1921, Shoghi Effendi pours out his heart and describes in great detail the grief that has consumed it:

Moments of gloom, of intense sadness, of agitation I often experience for wherever I go I remember my beloved grandfather and whatever I do I feel the terrible responsibility He has so suddenly placed upon my feeble shoulders…How intensely I feel the urgent need of a thorough regeneration to be effected within me, of a powerful effusion of strength, of confidence, of the Divine Spirit in my yearning soul, before I rise to take my destined place in the forefront of a Movement that advocates such glorious principles.

I know that He will not leave me to myself, I trust in His guidance and believe in His wisdom, but what I crave is the abiding conviction and assurance that He will not fail me.

The task is so overwhelmingly great, the realization of the inadequacy of my efforts and myself so deep that I cannot but give way and droop whenever I face my work...

Writing to Mrs. Whyte again later in February, Shoghi Effendi states:

…the pain, nay the anguish of His bereavement is overwhelming…

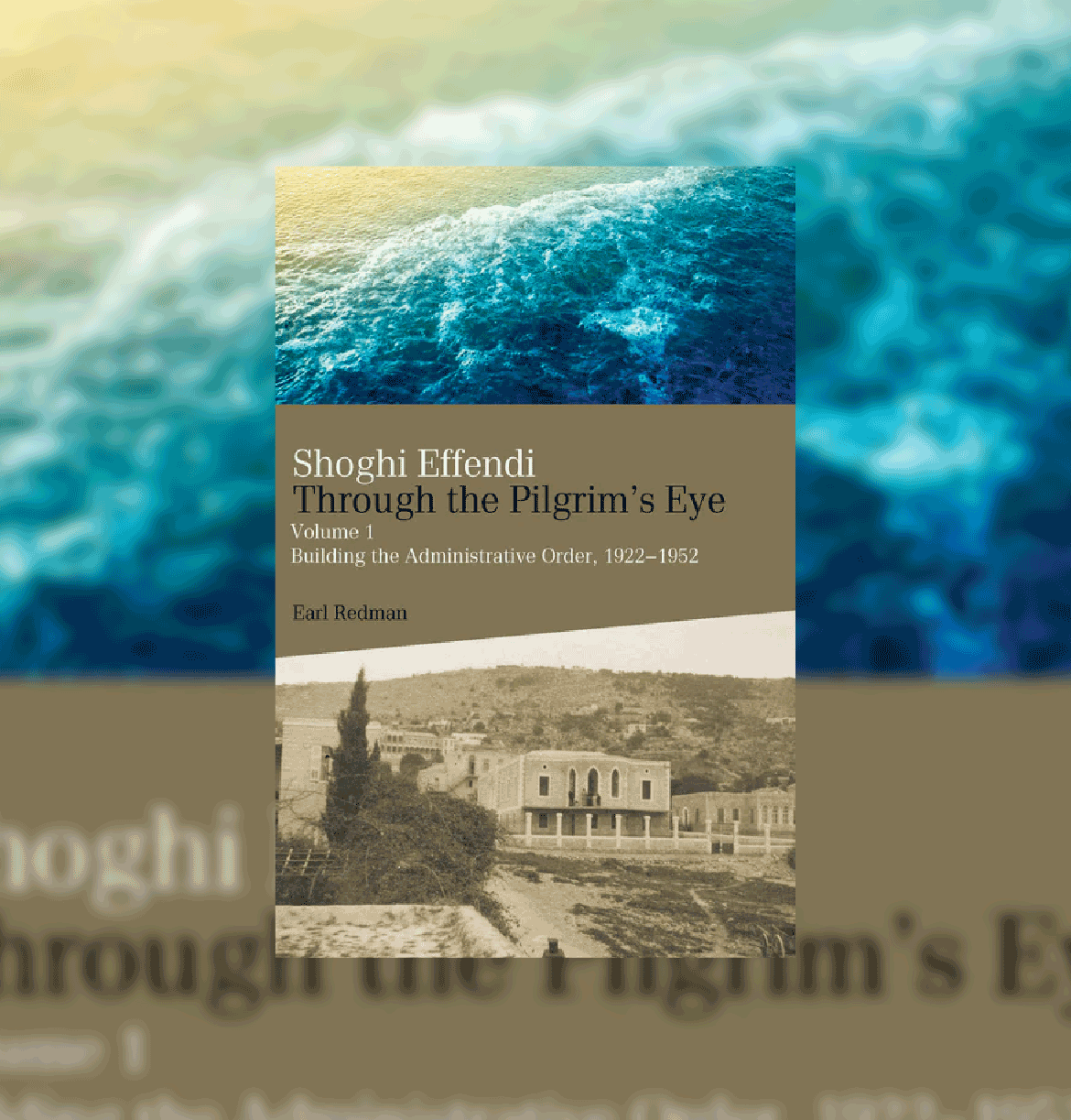

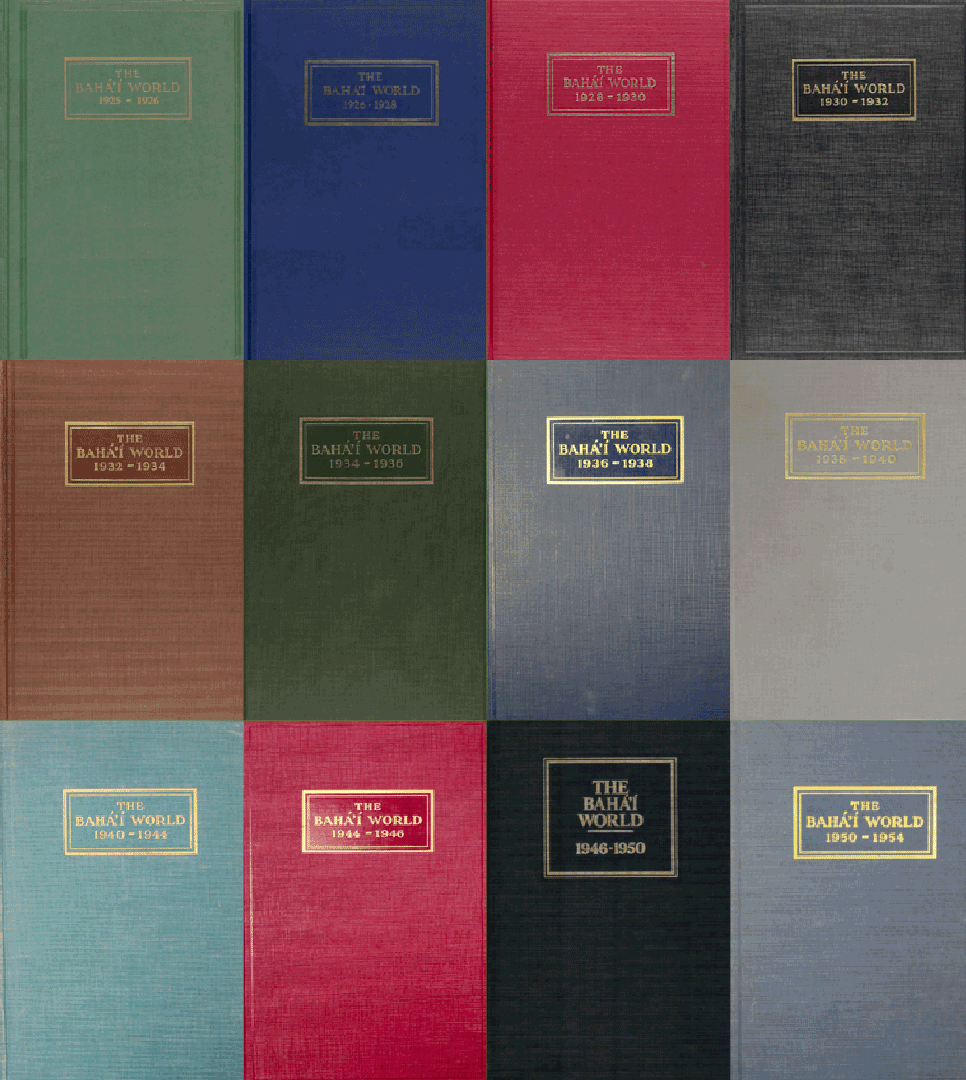

Before the first story quoting Earl Redman’s Shoghi Effendi Through the Pilgrim’s Eye Volume 1, this book should be introduced.

If it hadn’t been for Bahá'í historian Earl Redman’s magnificent book— Shoghi Effendi Through the Pilgrim’s Eye Volume 1 Building the Administrative Order, 1922-1952—several important and beautiful stories would have not found their way into the chronology, particularly the story of Effie Baker, the Australian photographer sent on a mission by the Guardian to photograph the holy sites in Persia in 1930 for his masterpiece, The Dawn-Breakers.

Shoghi Effendi Through the Pilgrim’s Eye is a work of art, opening vistas unto our beloved Guardian through the eyes and the flowing pen of pilgrims who were privileged to meet him, and Earl Redman’s signature thorough research has built a mosaic of pen-portraits filled with heart-rending, extraordinary moments. Only a few of his original findings are included in this chronology, so please procure a copy so you can discover them all.

This work was crucial in the architecture of the chronology because no one has so far aligned as many exact dates for the comings and goings of pilgrims in the ministry of Shoghi Effendi, and the exactness of Earl Redman’s book and his commitment to accuracy allowed many stories to find their place chronologically in this work.

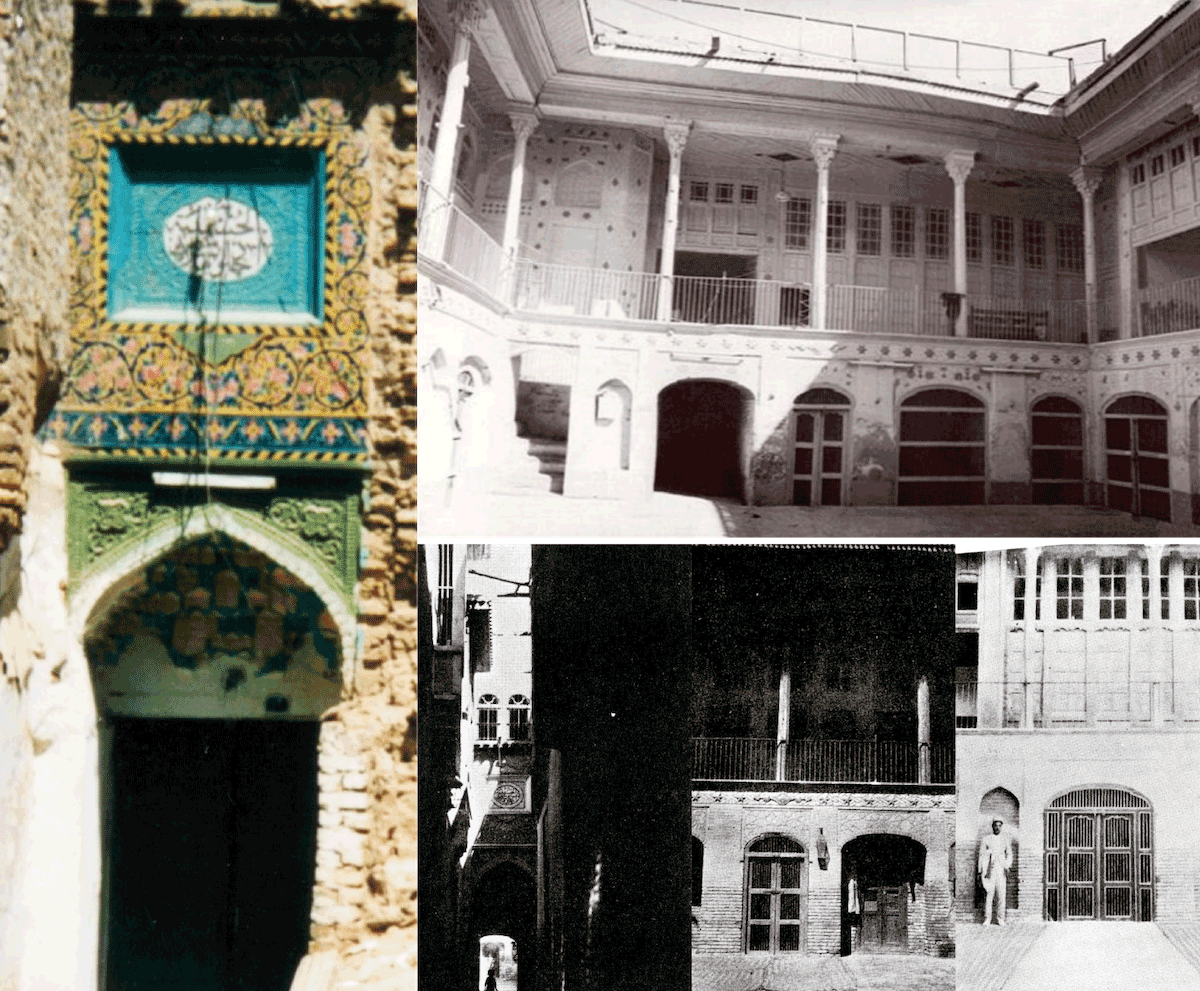

The Most Great House of Bahá'u'lláh in Baghdad: Color photo on the left: The entrance to the Most Great House. Source: © Sa'ad Salim, used with permission. Top photo: The house of Bahá'u'lláh in Baghdád, where the Holy Family moved while He was in Kurdistán. Source: Taazakh Khabar News; Bottom photo: Three less well-known photos of the outside of the house of Bahá'u'lláh in Baghdád from the street. Photo on the left, view of the house from the alley/street. Source: The Bahá'í World Volume 5, via Baha'i Media. Photo in the center, of the balcony of the Most Great House facing the port on the River Tigris. Source: TheBahá'í World Volume 6via Baha'i Media. Photo on the right, source: Nabíl, The Dawn-Breakers, Epilogue, page 663.

The Most Great House of Bahá'u'lláh in Baghdad was decreed by Bahá'u'lláh in the Kitáb-i-Aqdas to be one of the two places of pilgrimage for Bahá'ís, with the house of the Báb in Shíráz.

Bahá'u'lláh lived in the Most Great House for seven uninterrupted years as He revealed the Hidden Words, the Seven Valleys and the Four Valleys and the Kitáb-i-Íqán. Bahá'u'lláh effected a complete spiritual transformation on the Bábí community of Baghdád while He lived in the Most Great House, He taught the people of Baghdád in cafés, and it was from this House that he departed on 22 April 1863 for the Garden of Riḍván, where He made His momentous Declaration.

In 1921, in the last year of His ministry and with the beginning of the British Mandate in Iraq, 'Abdu'l-Bahá felt that the increased religious freedom and security allowed for the Bahá'ís to make repairs on the Most Great House, which He authorized. When the custodian died leaving no heirs, the House fell into the hands of the Shí’ah, but the decision was reversed two months later, and the Bahá'ís regained ownership of the House.

In 1921, the Bahá'ís were illegally evicted, the Shí’ah again sued for ownership, and the Court of Appeals, by a decision of 4 to 1, decided in favor of the Shí’ah on 23 November 1921, one week before 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s Ascension.

The Shí’ah clergy began to plot to take possession of the house by going through the Shí’ah courts, and caused such a commotion that on 8 February 1922, King Faisal of Iraq ordered the Bahá'ís evicted from the Most Great House and the keys remanded into the hands of the Governor of Bagdad, to keep the peace.

In 1923, the Government of Iraq handed the Shí’ah the keys for the Most Great House.

The Bahá'ís appealed to the Peace Court for possession of the House of Bahá’u’lláh in July 1923, but the Bahá'í community’s joy would be short-lived. In fact, it would last exactly five months.

On 20 December 1923, the Peace Court ruled in favor of returning possession of the Most Great House to the Bahá'ís, but the Council of Ministers of Baghdad ordered a stop to the decision until true ownership could be established.

This deeply upsetting situation would continue to weigh on Shoghi Effendi for years.

One day in early 1922, Shoghi Effendi walked back to 7 Haparsim from a visit to the Shrine of the Báb, followed by some Bahá'ís.

When he arrived at the House of the Master, Shoghi Effendi invited Boyce Nourse, a young pilgrim in Haifa with his family, to stroll through the garden with him.

Boyce asked Shoghi Effendi if he could take his photograph, and, surprisingly, Shoghi Effendi agreed.

This is one of the earliest photos of Shoghi Effendi as Guardian of the Faith, which was published in The Priceless Pearl, by Rúḥíyyih Khánum.

The photograph shows Shoghi Effendi standing in the garden of 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s home, holding a handkerchief filled violets he had picked at the Shrine of the Báb, and which he was bringing back for his beloved Great-Aunt, the Greatest Holy Leaf.

On that occasion, Shoghi Effendi had also picked a second bouquet of violets which he asked Boyce’s mother, Elizabeth Nourse to bring back with her to America.

Those violets were Shoghi Effendi’s first gift to America. They were preserved and later offered to the United States National Archives.

The Guardian’s very first long, 6-page letter was dated 5 March 1922, and addressed to the “fellow-workers in the Cause of Bahá’u’lláh,” and concerns the establishment of the Administrative Order of the Faith.

There are two main parts to this letter: the Mission of the Cause, Local and National Spiritual Assemblies, and Committees of the National Assembly.

The Mission of the Cause

In this first part of the 5 March 1922 letter, the Guardian sets forth the primary aim of the Bahá'í Faith, its propagation throughout the world:

How great is the need at this moment when the promised outpourings of His grace are ready to be extended to every soul, for us all to form a broad vision of the mission of the Cause to mankind, and to do all in our power to spread it throughout the world!...Now is the time to set aside, nay, to forget altogether, minor considerations regarding our internal relationships, and to present a solid united front to the world animated by no other desire but to serve and propagate His Cause.

Local and National Spiritual Assemblies

The second part of Shoghi Effendi’s masterful letter is aimed at the unfoldment of the Institutions of Bahá'u'lláh’s’ Administrative Order: the Local and National Spiritual Assemblies. First, the priority of establishing Local Spiritual Assemblies in every locality and the two-step process of electing a proper National Spiritual Assembly. The Guardian follows this important fact up with powerful quotes from Bahá'u'lláh and 'Abdu'l-Bahá regarding Assemblies:

Hence the vital necessity of having a local Spiritual Assembly in every locality where the number of adult declared believers exceeds nine, and of making provision for the indirect election of a Body that shall adequately represent the interests of all the friends and Assemblies throughout the American Continent.

At the end of this section, the Guardian emphasizes the importance of unity and cooperation between the members of the assembly and between Local and National Spiritual Assemblies:

Full harmony, however, as well as cooperation among the various local assemblies and the members themselves, and particularly between each assembly and the national body, is of the utmost importance, for upon it depends the unity of the Cause of God, the solidarity of the friends, the full, speedy and efficient working of the spiritual activities of His loved ones.

Committees of the National Assembly

In the last and shortest section of this major letter, Shoghi Effendi emphasizes the importance of committees for such issues as managing important publications like Star of the West, teaching campaigns, publishing Bahá'í literature, the construction of the Bahá'í House of Worship, race relations, receiving and interacting with Persian Bahá'ís, directing that all these important matters, as well as the archival preservation of the films and voice of 'Abdu'l-Bahá far from being dealt with by individual Bahá'ís or Local Spiritual Assemblies, should be:

…minutely and fully directed by a special board, elected by the National Body, constituted as a committee thereof, responsible to it and upon which the National Body shall exercise constant and general supervision.

The Guardian was beginning to unfold the Bahá'í Administrative Order.

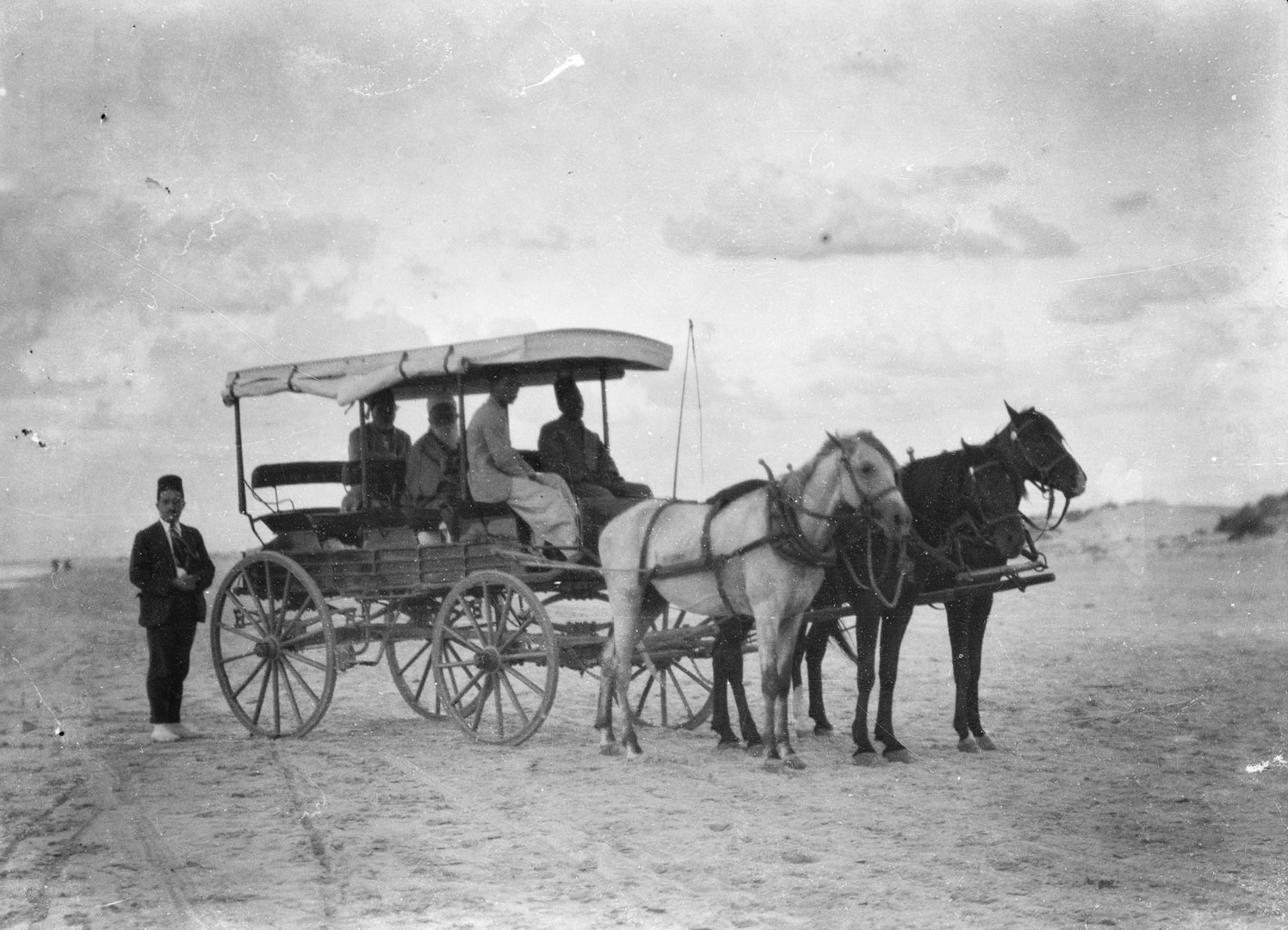

“A place for 'Abdu'l-Bahá”: A photograph of 'Abdu'l-Bahá sitting in His carriage on His way back from Bahjí to Haifa. 'Abdu'l-Bahá is on the sands of the beach close to which He wished to be interred. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

We all know the exactly location of 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s Shrine today, but a hundred years ago, Shoghi Effendi could already see it. Mason Remey, a well-known American architect, arrived in Haifa on 10 March 1922 to participate in the consultations Shoghi Effendi had called for, and he stayed until early April.

At one point during Mason Remey’s stay in Haifa, shortly before his departure, Shoghi Effendi seized the opportunity to consult with him on several things, such as the future Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh and eventual Temple on Mount Carmel, the terraces of the Shrine of the Báb and the three extra rooms 'Abdu'l-Bahá had stipulated He wished added.

Shoghi Effendi also brought Mason Remey to study the possible future site of a separate Shrine for 'Abdu'l-Bahá.

'Abdu'l-Bahá had once said he wished to be buried between the Shrines of the Báb and Bahá'u'lláh, on the sands of the crescent-shaped beach. When Shoghi Effendi and Mason Remey arrived at the spot the Guardian had envisioned, they walked about 400 meters inland until they reached a spot that was halfway between the beach and the railroad tracks.

Shoghi Effendi saw a 2.5 square kilometer property, filled with trees and intersecting waterways and lakes. In the middle, Shoghi Effendi pictured a Taj Mahal-like Shrine, but stated the final decision belonged to the Universal House of Justice.

Today, 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s shrine is being erected in that same approximate location, halfway between the Shrines of the Báb and Bahá'u'lláh, and the building will be at once majestic when one stands in front of it, and effaced from a distance, but the Guardian’s infallible and momentous vision still carries us.

‘Alí-Aṣghar Qazvíní was a remarkable man, deeply spiritual, pious, discreet, and hardworking. He was taught the Faith by a wandering dervish, and arrived in Haifa shortly after the Ascension of 'Abdu'l-Bahá.

When Shoghi Effendi was named Guardian, ‘Alí-Aṣghar Qazvíní offered him his services.

For 25 years, ‘Alí Aṣghar was at Shoghi Effendi’s side, loyal, understanding, ready to render any service to his beloved Guardian. He became known as “Mu’allim” (Teacher), and he had many duties: He taught the Bahá'í children written and spoken Persian, as well as the Bahá'í teachings: serving the Guardian’s guests tea; bringing the cakes for the Feast Days

‘Alí-Aṣghar Qazvíní’s most important duty by far was as postman of the Guardian.

Under the beating sun or the pouring rain, every day for 25 years, ‘Alí-Aṣghar carried the heavy brief case of mail back and forth from the Post Office. This was by far the most confidential position anyone could have, and he was the perfect man for the job. Shoghi Effendi trusted him so completely that it made him the envy of everyone.

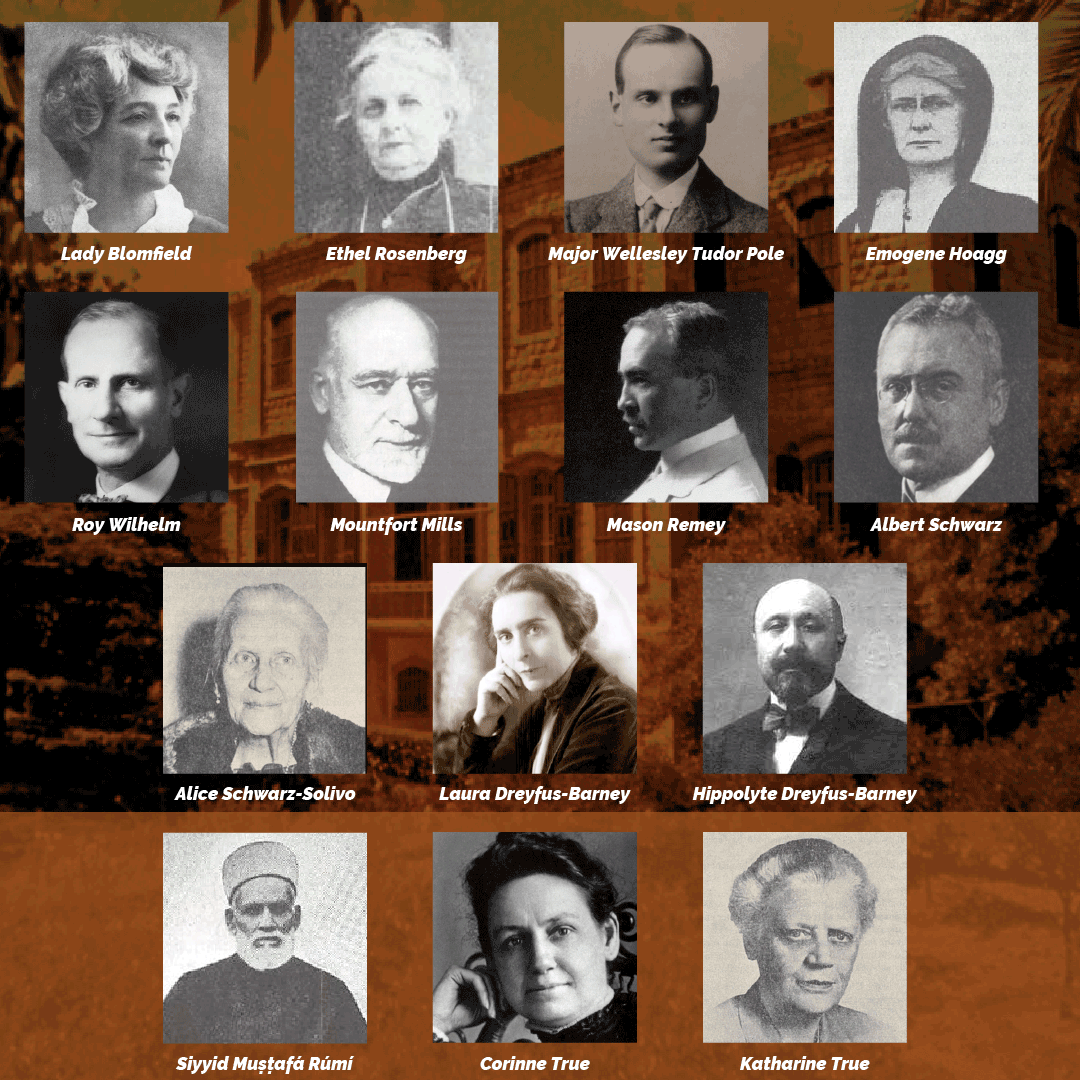

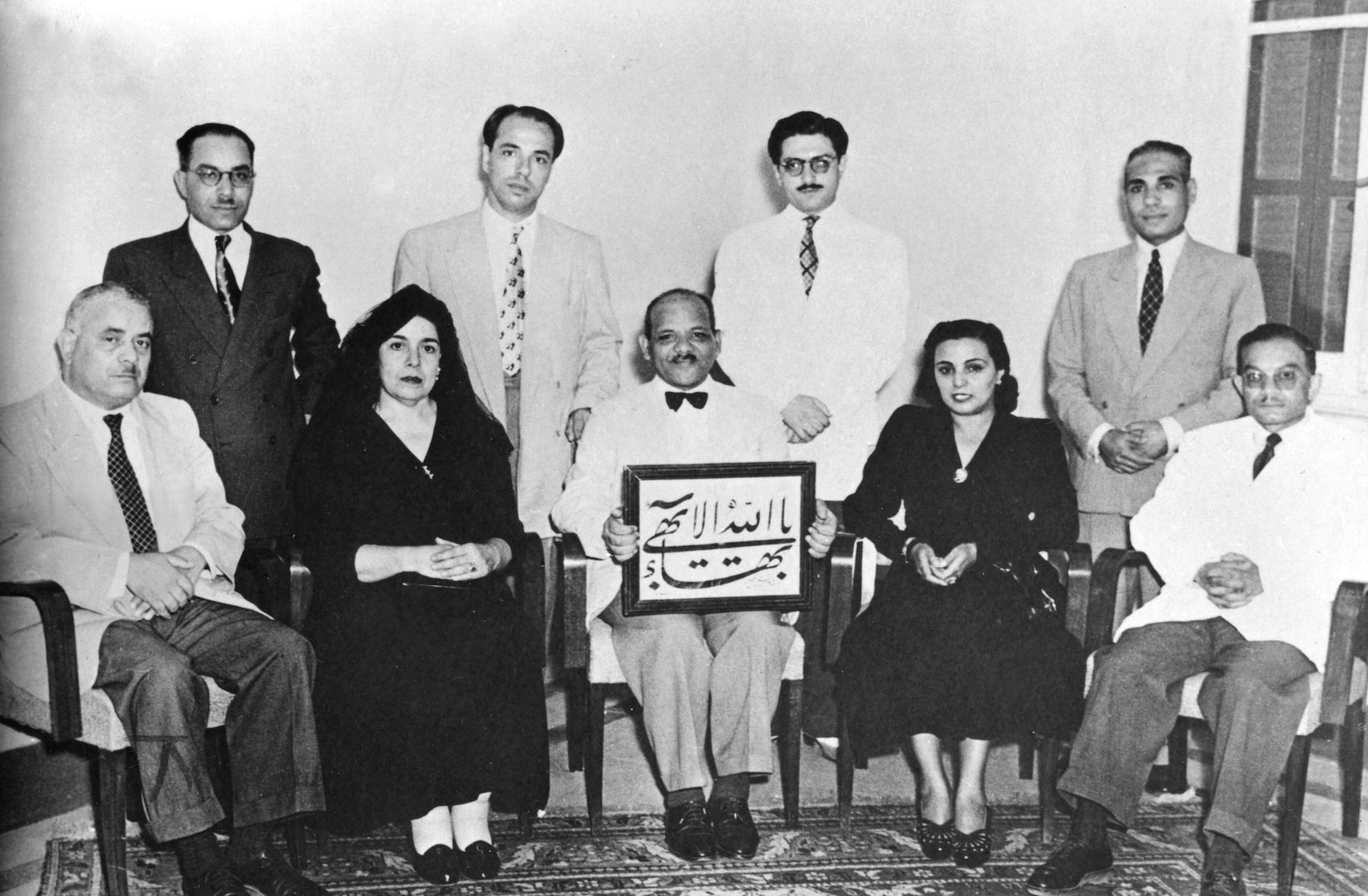

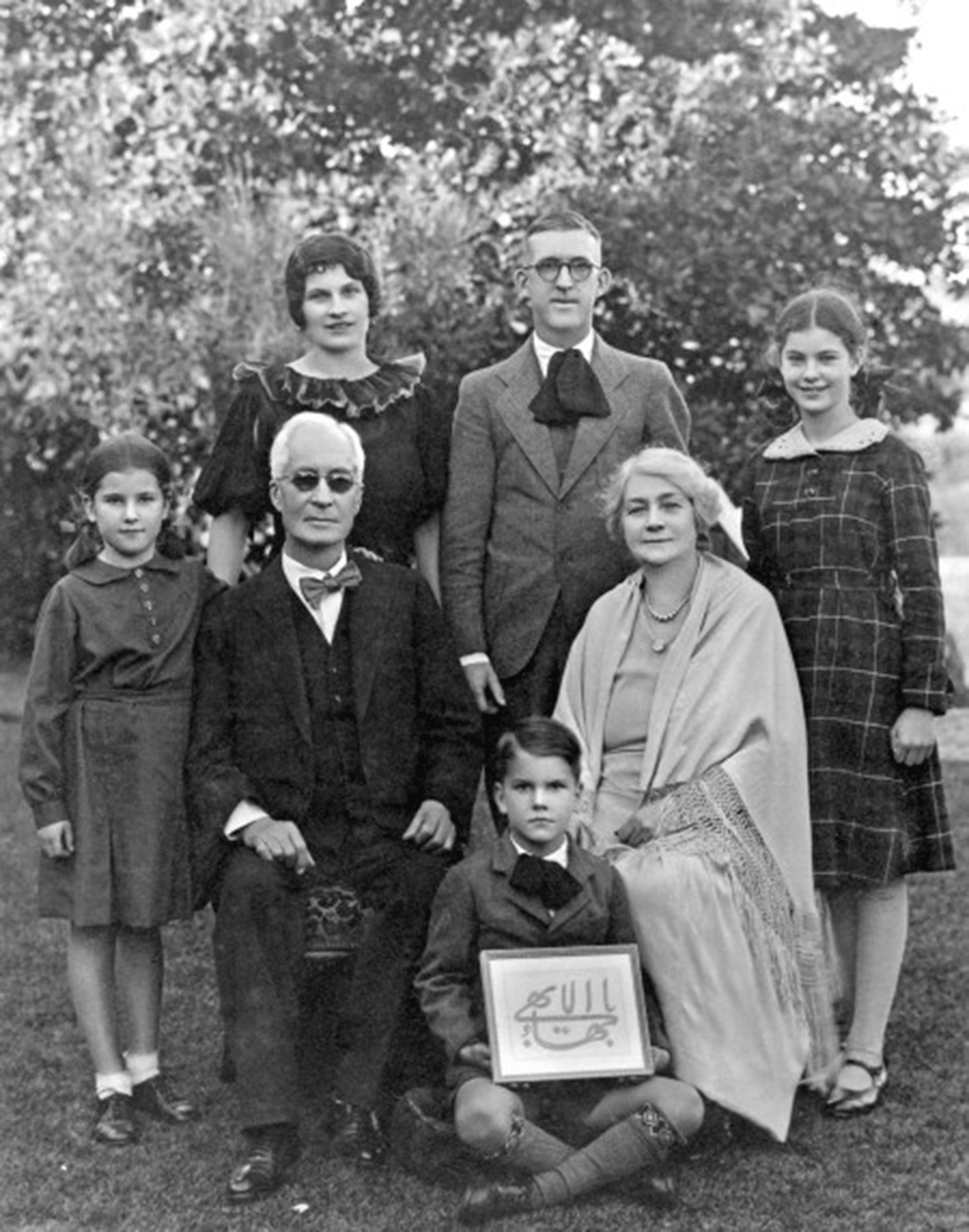

The participants at the consultative meeting in Haifa called by the Guardian in March 1922. The three on the bottom row arrived late.

According to Rúḥíyyih Khánum, there was little doubt in her mind that upon reading 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s Will and Testament, one of the first thoughts of Shoghi Effendi was the feasibility of electing the Universal House of Justice as soon as possible.

In fact, in one of his earliest communications to the Bahá'ís in Persia on 16 January 1922, the Guardian refers to the Universal House of Justice, stating that he would later announce to the friends the preliminary arrangements for its election.

There was never any question in the Guardian’s mind regarding the function and significance of the Universal House of Justice. In March 1923, he described the Universal House of Justice as "that Supreme Council that will guide, organize and unify the affairs of the Movement throughout the world."

To this end, one of the young Guardian’s earliest acts in March 1922 was to summon prominent, devoted and deepened Bahá'ís to Haifa to discuss this matter with him.

From England, the Guardian called Lady Blomfield, Ethel Rosenberg, and Major Tudor Pole. From America, he summoned Emogene Hoagg, Roy Wilhelm, Mountfort Mills, and Mason Remey. The Guardian called Laura and Hippolyte Dreyfus-Barney from France, and Consul and Alice Schwarz from Germany. Shoghi Effendi had also summoned two well-known Persian Bahá'ís, Avárih and Fazel, but they were not able to attend. Three Bahá'ís arrived late: Siyyid Mustafa Rumi from Burma, and Corinne True and her daughter, Katherine, from the United States.

“Two countervailing forces.” Background photo by Marcel Strauß on Unsplash.

According to Rúḥíyyih Khánum, in these early months of the Guardian’s ministry there were two forces at work.

One force was the youthful eagerness of the Guardian to implement all the instructions of his beloved Grandfather, so clearly set forth in His Will and Testament, including the election of the Universal House of Justice.

The other countervailing force was the protection bestowed on the Guardian by the Will and Testament of 'Abdu'l-Bahá itself: that he would unerringly, infallibly be guarded by Divine guidance.

As Shoghi Effendi repeatedly attempted to set in motion the preliminaries of the election of the Universal House of Justice, the Hand of Divine Providence also repeatedly steered events in a way which showed him that this action was premature.

During the consultations with these 11 stalwart Bahá'ís, it became apparent to the Guardian that, no matter how much he wished to inaugurate the preliminary stage of the election of the Universal House of Justice, it would have been a dangerous step to take in 1922.

The necessary firm, solid foundation of Bahá'u'lláh’s Administrative Order was not yet in place, and there was not yet a sufficient reservoir of qualified and well-informed Bahá'ís to draw from.

Shoghi Effendi, in his infallibility and his familiarity with 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s leadership and the Bahá'í Holy Texts, had fully realized that electing the Universal House of Justice in early 1922 was not only premature but impossible.

The Bahá'í world needed strong local and national institutions before its world governing body could be elected. You never placed the roof on a building that didn’t have either a foundation or walls.

The issue was that the instinct of many Bahá'ís, including 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s family, the believers Shoghi Effendi had invited to consult in Haifa, along with the local British government, were all trending in the opposite, and wrong direction: they all believed that electing the Universal House of Justice now was the best solution.

They had misconstrued Shoghi Effendi’s youth, his terrible state of grief that had temporarily weakened him, and they thought he needed the support of the Universal House of Justice.

They had not only severely underestimated the Guardian, but they were utterly wrong in their conclusions. The way Shoghi Effendi navigated this delicate situation in which he had no one on his side, was the way a brilliant general never got distracted by details or emergencies.

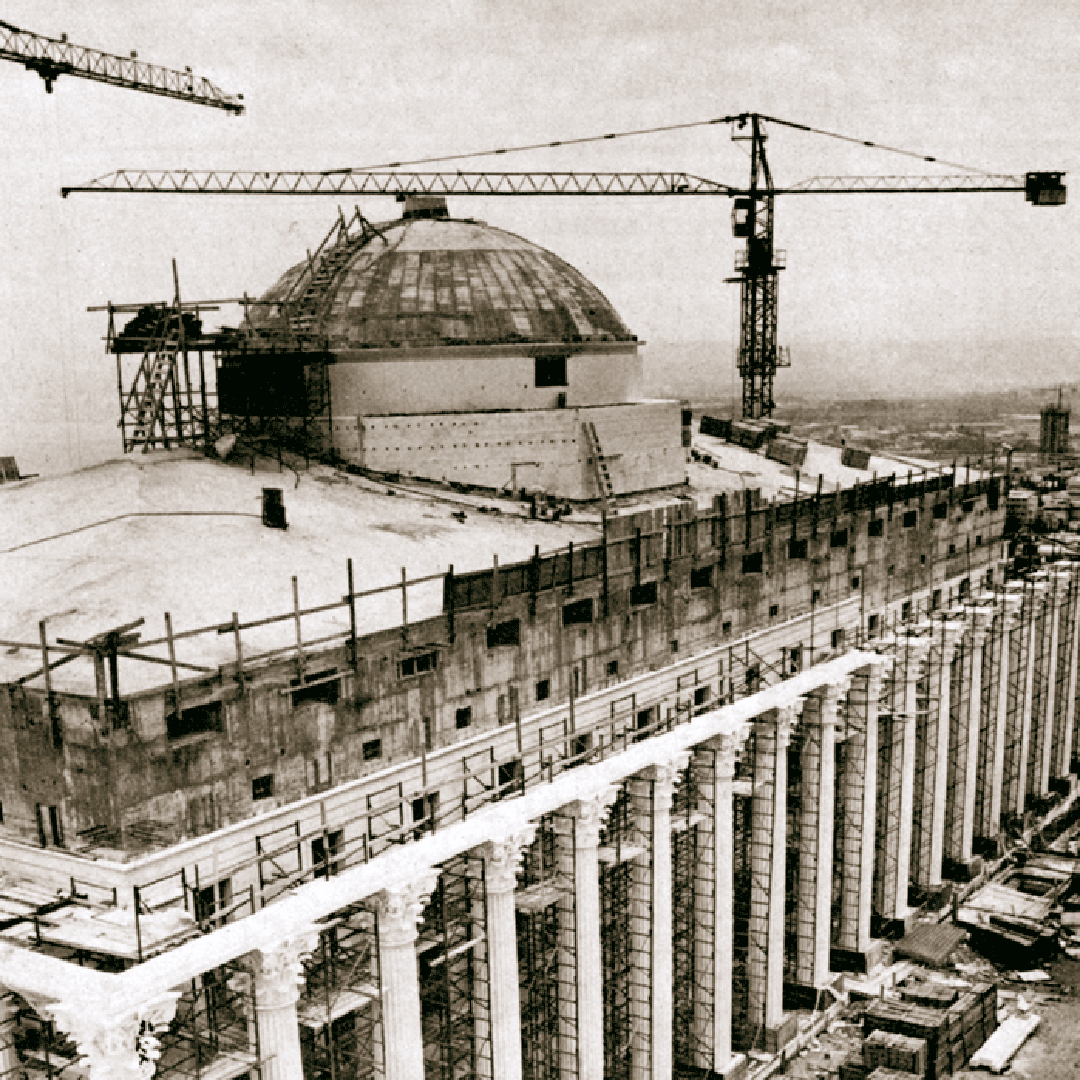

“Construction of the Administrative Order”: You can’t have a dome without having a foundation. Photograph from the construction of the seat of the Universal House of Justice in 1979. Source: Reddit.

He eventually won everyone over to his divinely-guided opinion that this was indeed, not the right time to elect the Universal House of Justice, but rather the time to establish functioning and mature Local and National Spiritual Assemblies, worldwide, to elect the Universal House of Justice when the time was right, which would end up being in 41 years.

In the end, Shoghi Effendi sent every Bahá'í who had come to consult back to their homes to begin working on the formation of Local Spiritual Assemblies, and he asked the American Bahá'ís to convey to the American National Convention that they needed to become legislative body, guiding the affairs of the National community.

Two months after he became Guardian, Shoghi Effendi was already laying the foundation for the Administrative Order of the Faith of Bahá'u'lláh, the single greatest achievement of his ministry.

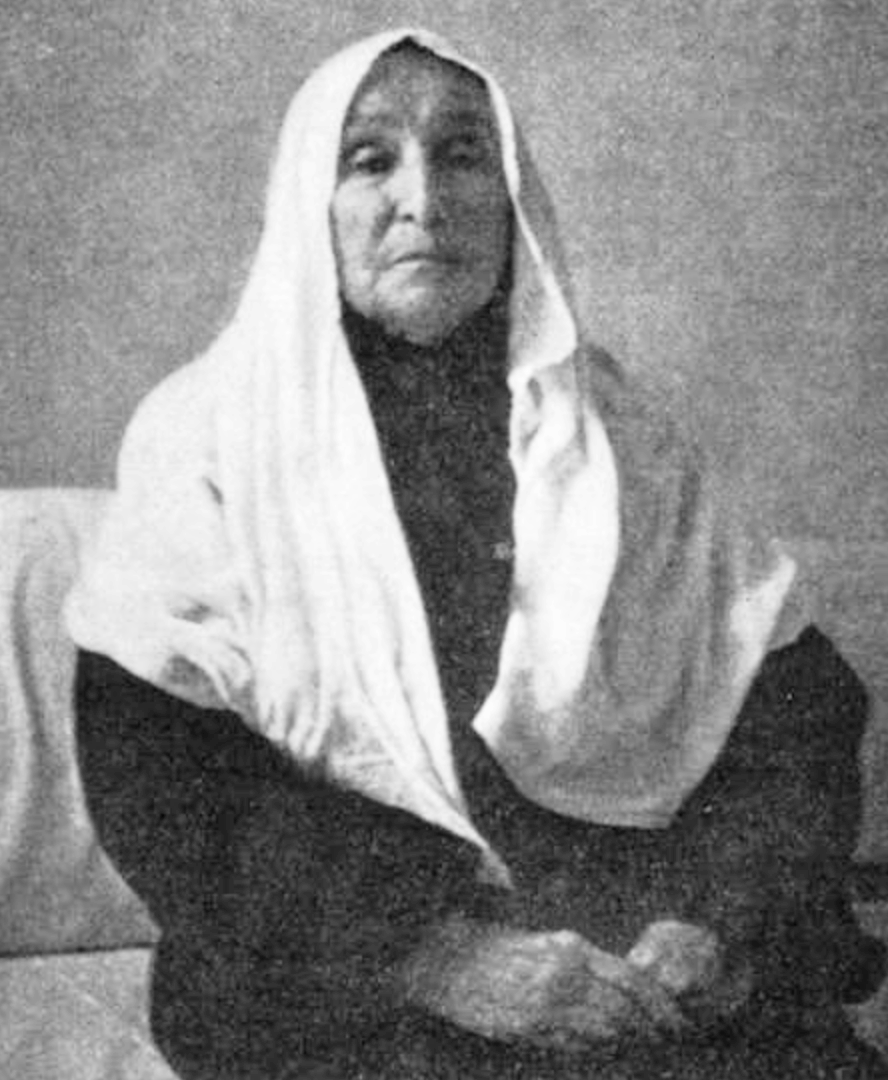

Photograph of the Greatest Holy Leaf. Source: Uplifting Words.

Before Shoghi Effendi left Haifa for 8 months of rest and recuperation, he appointed a body of nine Bahá'ís to act tentatively as an Assembly in the Holy Land and appointed Bahíyyih Khánum, the Greatest Holy Leaf to administer all Bahá'í affairs in his absence in consultation with the family of 'Abdu'l-Bahá and the Assembly.

The decision, along with a copy of letters from Bahíyyih Khánum and Shoghi Effendi to that effect, were published in Star of the West.

“The growth of the Bahá'í World Center”: An aerial view of the Arc in the 1960s. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

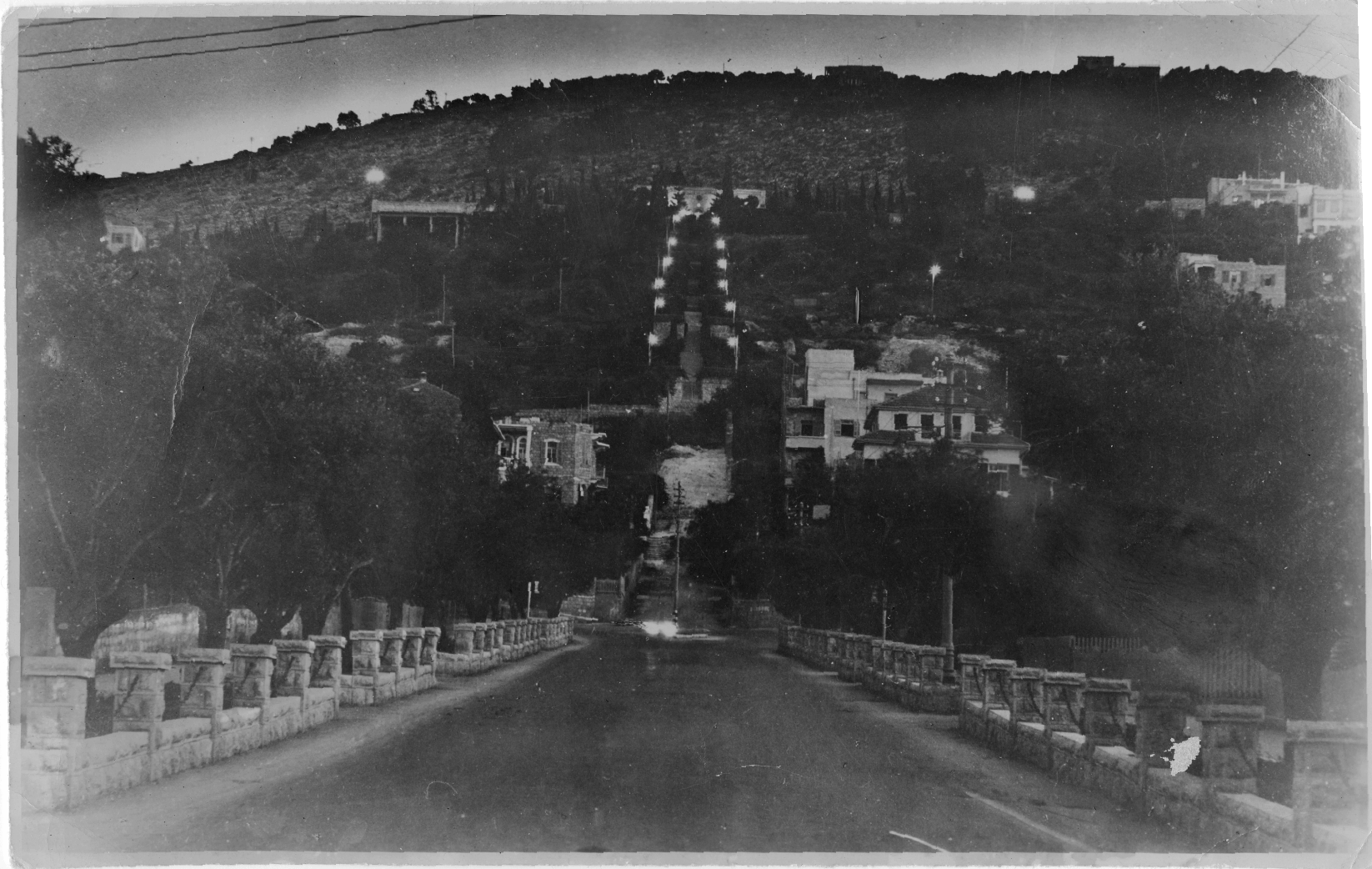

From the very beginning of his Guardianship, Shoghi Effendi devoted a considerable amount of time, energy, and attention to developing the properties of the Bahá'í World Centre. Work had already begun on the western Pilgrim House, and for the Riḍván while he was away in Europe, the Shrines of the Báb and Bahá'u'lláh had been illuminated electrically for the first time.

Before leaving for Europe, in March 1922, Shoghi Effendi had discussed with Mason Remey the future Mashriqu’l-Adhkár on Mount Carmel, and landscaping options for the current properties.

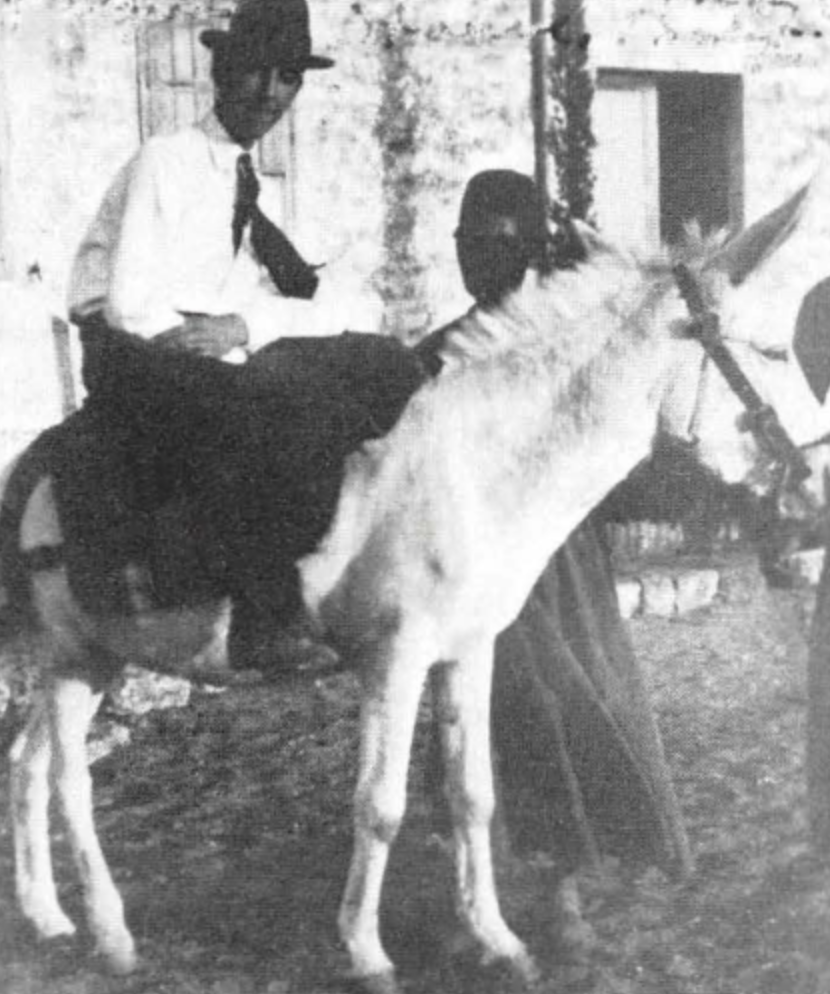

Curtis Kelsey astride a donkey at the Pilgrim House in Bahjí in 1921. Source: Bahaimedia.

Curtis Kelsey was not an educated man. He had bounced around schools in his childhood, even going to a military academy for a short time. He was profoundly independent, and had a bit of a rebellious spirit. His mother, Virginia Kelsey—the most powerful influence in his life—became a Bahá'í in 1909. Curtis was deployed to France during World War I, and was unable to avoid combat. He became a Bahá'í in 1917.

After the war Kelsey served on the Local Spiritual Assembly of New York City with Roy Wilhelm who recommended to ‘Abdu’l-Bahá that Kelsey be invited to the Holy Land to install the three electrical generators he had purchased for the House of the Master, the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh, and the Shrine of the Báb.

Curtis arrived in Haifa in September 1921, and immediately began working diligently on the electrical installations in Haifa and Bahjí. Curtis loved working in Haifa, because he could see 'Abdu'l-Bahá every day, but in Bahjí, he yearned for his presence, so whenever he was working there, he found any excuse he could to return to Haifa just to see the Master. These were the last two months of 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s life, and they were joyous.

A bond of camaraderie developed between Curtis, the tall American, Fujita, the small Japanese, and 'Abdu'l-Bahá. From three completely different cultures, the friends treasured their time together and developed a very cute ritual. Fujita had a brown cat, and he would lock him in the kitchen each day before 'Abdu'l-Bahá came for lunch. Then, when the Master swept into the Pilgrim House, every day, he would tell Fujita "Let the cat out." As soon as Fujita freed the little animal, he raced across the room to 'Abdu'l-Bahá to be stroked and fed. 'Abdu'l-Bahá enjoyed this little charade every bit as much as Curtis and Fujita.

When one of 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s daughters—despairing that her 77-year old Beloved Father was not getting enough sleep—asked Him why he would go all the way to the Pilgrim House to have lunch instead of eating and resting at home, 'Abdu'l-Bahá gave her the simplest, most touching answer:

I like to eat with my friends.

Curtis Kelsey was in the Holy Land when 'Abdu'l-Bahá passed away on 28 November 1921, and as soon as he heard the Will and Testament of 'Abdu'l-Bahá appointing Shoghi Effendi as the Guardian, he became deeply devoted to him until the end of the Guardian’s life

Curtis Kelsey with pilgrims at the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh during his first pilgrimage. © United States National Bahá'í Archives, used with permission.

A few days before 5 April 1922—when the Guardian left for Switzerland—Shoghi Effendi saw Curtis Kelsey in the street and asked him to join him on a walk to the Shrine of the Báb. Curtis Kelsey was a deeply spiritual man, and when he had heard the Will and Testament, he knew that Shoghi Effendi should be considered almost like an extension of 'Abdu'l-Bahá Himself, and so he had an instinct this walk was not going to be a run-of-the-mill walk, because he was with the Guardian. The thought crossed Curtis’ mind that the Guardian might give him a special assignment.

As Shoghi Effendi and Curtis made their way up Mount Carmel, Haifa children played around joyfully dancing in and out of the shadows in the street, cast by the floodlight at the base of the Shrine of the Báb. These were the early days of electricity and it was an exciting new development for the residents: they didn’t have electricity in their homes yet, but the Guardian had brought it to Mount Carmel.

Shoghi Effendi turned to Curtis and thanked him for the wonderful work he had done in installing the three generators, assuring him that 'Abdu'l-Bahá Himself appreciated his strenuous efforts. Such praise made Curtis uncomfortable and he blushed, batting away the compliment:

Well, Shoghi Effendi, I was very happy doing the work for the Master, and I want no credit.

The Guardian stopped walking. He looked into Curtis’ eyes and firmly reiterated:

Nevertheless appreciation goes with your service.

Curtis made light of his work, and as he did, the Guardian grew even firmer. He strongly conveyed to Curtis the signal importance of sincerely thanking a person for services rendered. It was a defining experience for Curtis Kelsey. After this interaction with the Guardian, for the rest of his life, he showed gratitude and appreciation for everyone who had assisted him, no matter how small the service they had rendered.

The quality of radiant gratitude was shared by his beloved Great-Aunt, the Greatest Holy Leaf. A few days before Curtis Kelsey returned home, she had written a letter to his mother, Valeria Kelsey, about the stellar services her son had rendered, echoing the words of the Guardian to Curtis himself during their memorable walk on Mount Carmel:

My dear sister in this blessed Cause…Mr. Curtis Kelsey is leaving after a sojourn of hard work recompensated by the blessings of our Lord from on high and the affection of each and everyone who happened to come in contact with him; we thought that at this hour, when he is to leave us with perhaps a faint ray of hope to see us again, we would write a few words and express our idea of the sincerity and absolute devotion with which your son accomplished his allotted task and we would be in turn congratulating you for this achievement and assuring you that [each and] every time that we see those bright lights shining from those blessed Tombs we cannot but remember that sincere and diligent work which was put into it and the sacrifice of Mr. Wilhelm who supplied the necessary material.

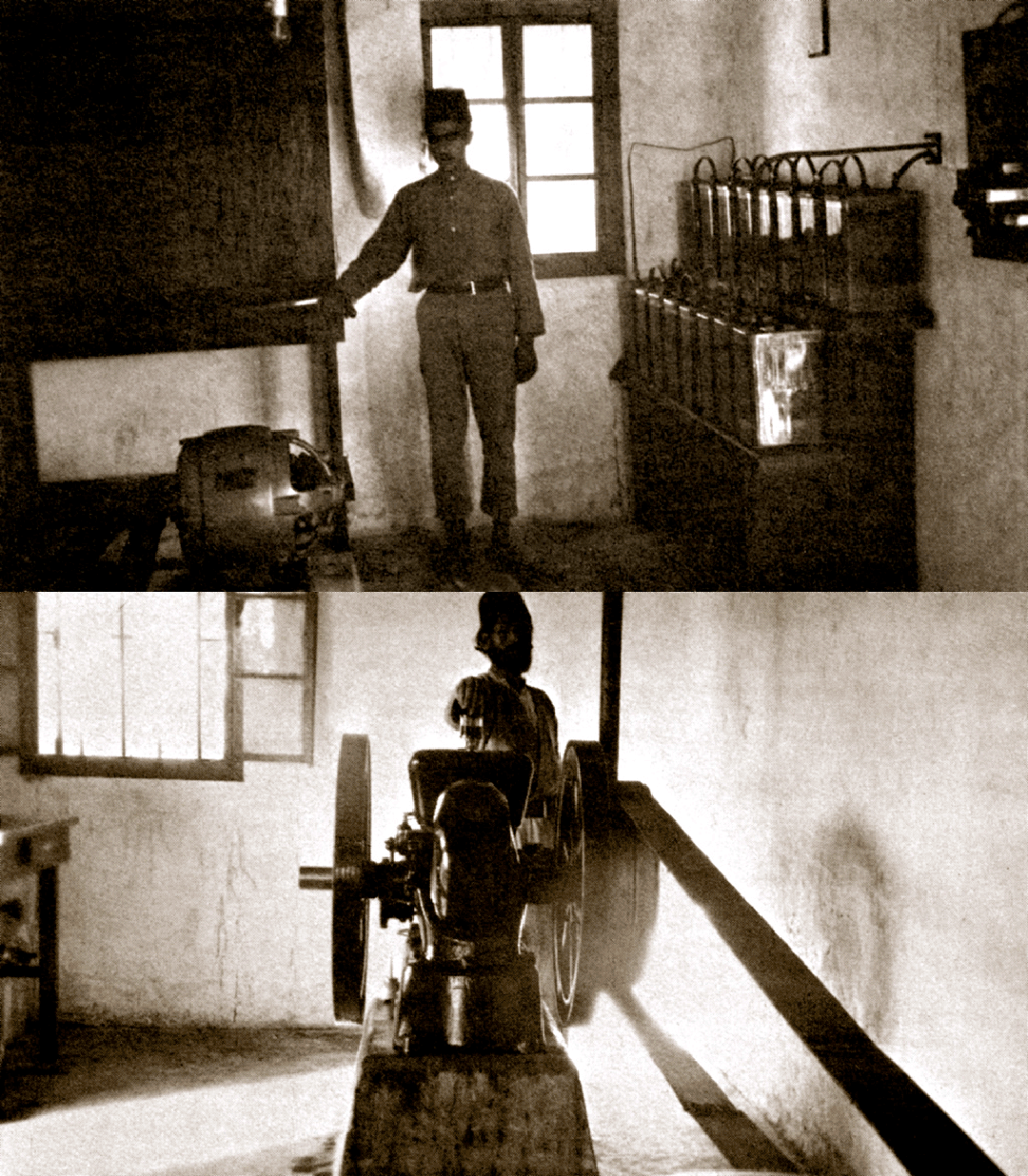

The Shrines are illumined for the first time: Photograph of the generators that illumined the Shrine of the Báb. Source: Bahá'í Historical Facts.

In early April, before he traveled to Switzerland for 8 months to recover from the shock he had just received, Shoghi Effendi gave instructions to Curtis Kelsey for his very first plan for beautifying the Holy Places: the illumination of the Shrine of the Báb with the help of generators.

The Guardian’s goal was to actualize 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s long-cherished desire to bathe the Shrine of the Báb in light, and he was going to fulfill it.

The illumination of the Shrine of the Báb was deeply significant. During His imprisonment in Máh-Kú, the Báb had been deprived of even a lamp, and now he was bathed in light at night. The floodlights at the base of His Shrine in Haifa was the first of its kind in the city: there was a floodlight at the base of the building, a light on the roof of the building, and two 1,000-watt lamps on poles on either side of the Shrine in aluminum-framed globes. A third, smaller globe was at the top and center of the front wall.

Photograph of the Shrine of the Báb and its terraces, brightly illumined at night. © United States National Bahá'í Archives, used with permission.

On the first day of Riḍván, 21 April 1922—and two weeks after the Guardian had left for Germany and Switzerland—the Shrine of the Báb and the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh were illuminated for the very first time, and both Bahá'ís, and Haifa and 'Akká residents were filled with joy.There were strings of lights that illuminated the fledgling terraces down to the street.

Across the bay, at Bahjí, the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh was flooded with light and the glow was visible from the Shrine of the Báb.

The illumination was so bright in Haifa that it temporarily confused a sea captain steering in his ship that night, and because of this incident, the port authorities added the lights of the Shrine of the Báb to the official navigation chart.

The Greatest Holy Leaf’s commanding presence. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

After the Shrines had been illuminated, it was time for Curtis to return to New York, but he wasn’t worried about how he would get there, even though he only had enough money to travel from Haifa to Istanbul.

This was when he experienced the full commanding power of the Greatest Holy Leaf—then 76 years old—in her role as Vicegerent during Shoghi Effendi’s long absence from the Holy Land. The Greatest Holy Leaf was a gentle person, she was kind and loving, but she was also a redoubtable commander, and a fearless defender and protector of the Faith, and she—the Outstanding Heroine of the Bahá'í Dispensation—was the reason both 'Abdu'l-Bahá and Shoghi Effendi were able to leave the Holy Land for long periods of time. Combining both of their absences from 'Akká and Haifa on trips within Israel, to Europe, North America, and Africa, the Greatest Holy Leaf was alone, acting Head of the Bahá'í Faith for 7 years and 3 months.

Curtis’ plan was to travel from Haifa to Istanbul with the money he had, then get a job there and earn enough money to sail back to New York. He had absolutely no idea that the Greatest Holy Leaf knew he was in essence, broke, and one day, he was summoned to Bahíyyih Khánum’s presence, three of her nieces—daughters of 'Abdu'l-Bahá—at her side.

One of 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s daughters warmly greeted Curtis, and praised him for his stellar and literally luminous work, and remembering what Shoghi Effendi had taught him, he humbly accepted her expressions of gratitude, but when she insisted that he take money to return to the United States, Curtis refused:

No, all my affairs are in order.

There was no conceivable way that Curtis Kelsey would take money from 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s family. The other two daughters of the Master were adamant. Curtis Kelsey refused again. In the end, the Greatest Holy Leaf reached out, took Curtis’ hand and said:

Kelsey, you need this money to pay for your return home.

The Greatest Holy Leaf placed the money in Curtis’ hand. And Curtis only accepted it on one condition:

I will take it if you will let me return it after getting home.

To this, the Greatest Holy Leaf firmly said:

No.

What that single word, spoken with such authority, Curtis could sense that the Greatest Holy Leaf had issued a divine command and it reminded him of the way in which 'Abdu'l-Bahá, so gentle and patient, could be adamantly firm when the situation called for it. Curtis graciously accepted the money and thanked them for it, but as he was leaving the Greatest Holy Leaf’s room, he couldn’t help but wonder how they had known of his dire financial situation. He hadn’t told a soul about it.

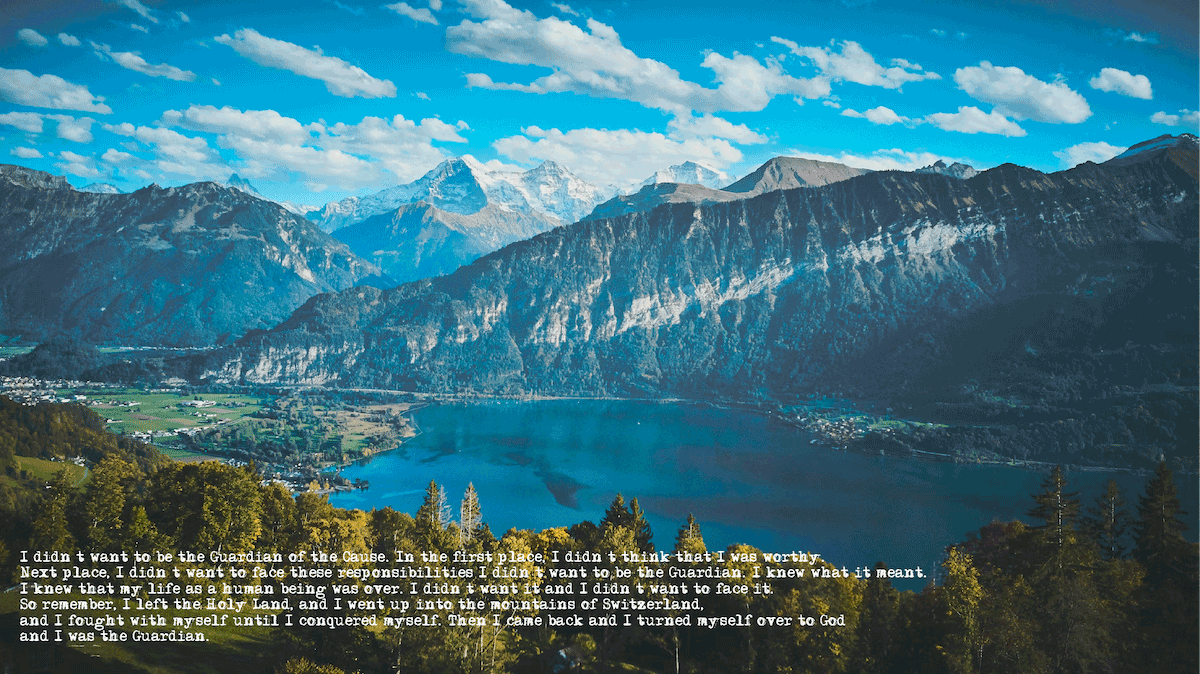

By early April 1922, Shoghi Effendi was utterly crushed under the weight of his sorrows and boundless grief, and he was forced to leave the Holy Land to regain the strength he needed to fulfill the duties of Guardianship. He had not wanted this position, and did not want it now, but he knew it was his duty to carry on the work of 'Abdu'l-Bahá. Many years later, he would tell Leroy Ioas:

I didn’t want to be the Guardian of the Cause. In the first place, I didn’t think that I was worthy. Next place, I didn’t want to face these responsibilities…I didn’t want to be the Guardian. I knew what it meant. I knew that my life as a human being was over. I didn’t want it and I didn’t want to face it.

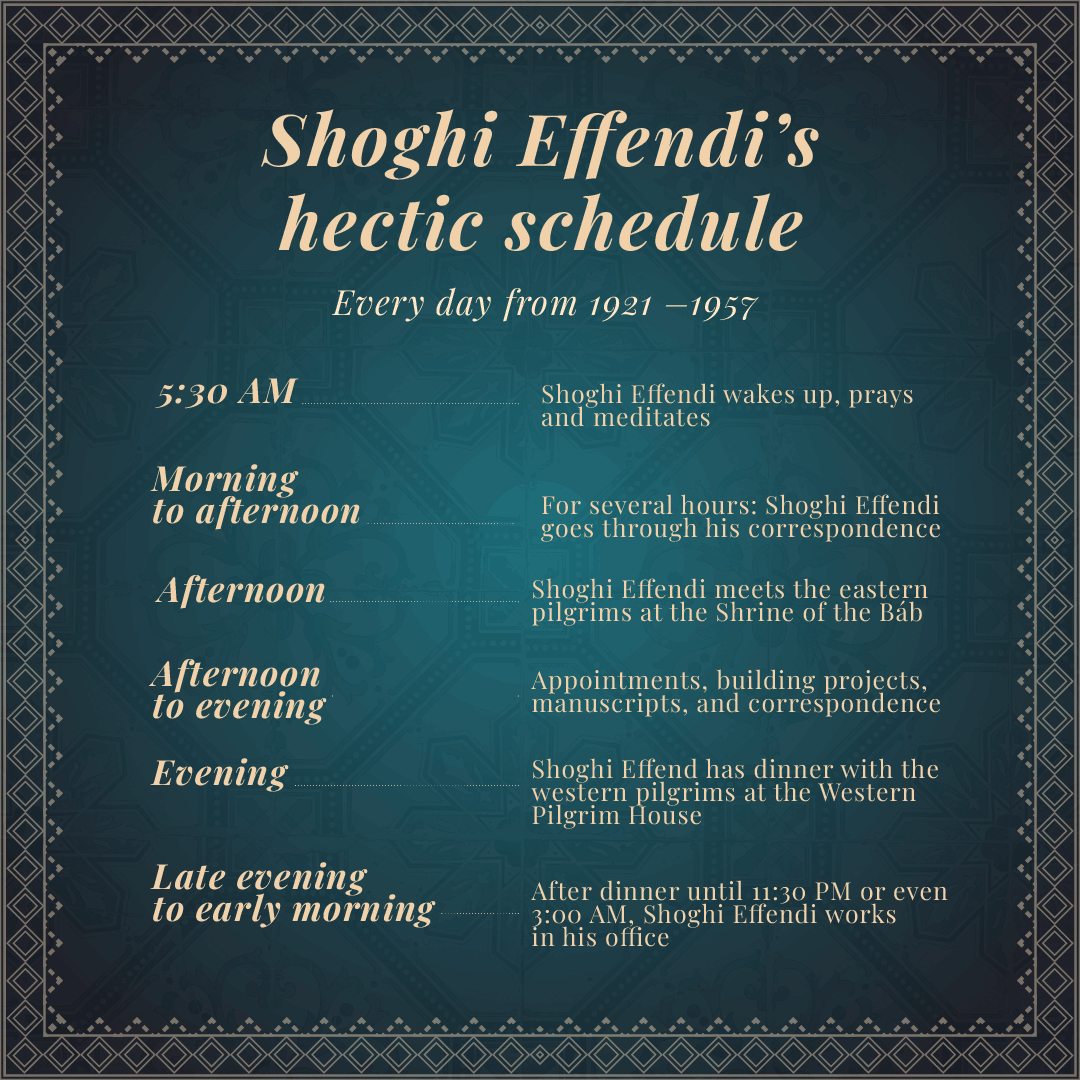

One day, Shoghi Effendi. Had gone to bed at 3 AM and woken up at 6 AM. Another day, he had worked 48 hours straight without eating or drinking anything. He was spent and burnt-out, and in Haifa, he could never rest, only work.

Shoghi Effendi never would have been able to leave without such a perfect ally, friend, and capable and talented administrator such as Bahíyyih Khánum to oversee all Bahá'í affairs in Haifa and worldwide.

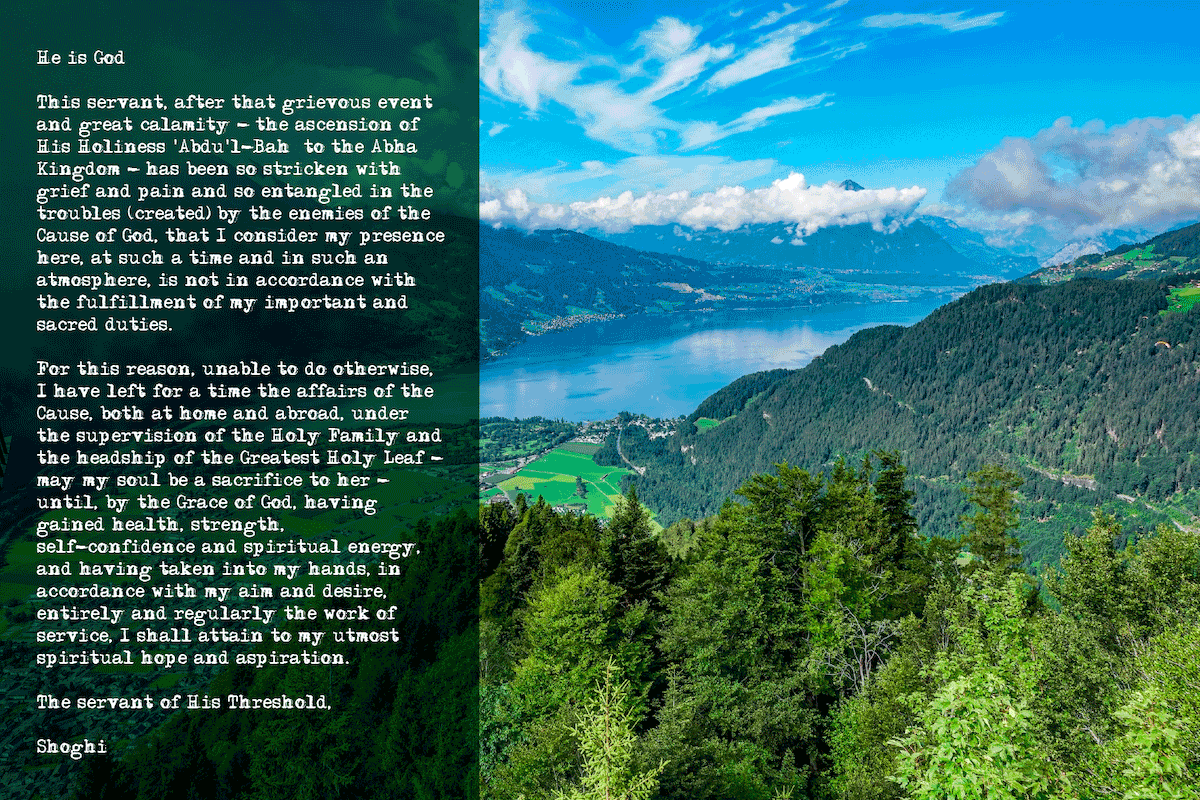

“I have left.” Base image: A view of Interlaken, Switzerland. Source: Josef Ivan Jimenea on Unsplash.

Shoghi Effendi needed radically different scenery and quiet to rebuild himself, but also contemplate the immense task that lay ahead of him, and so he left Haifa for Europe on 5 April, accompanied by his eldest cousin.

Shoghi Effendi wrote a letter to the Bahá'ís about his forced leave of absence:

He is God!

This servant, after that grievous event and great calamity - the ascension of His Holiness 'Abdu'l-Bahá to the Abhá Kingdom - has been so stricken with grief and pain and so entangled in the troubles (created) by the enemies of the Cause of God, that I consider my presence here, at such a time and in such an atmosphere, is not in accordance with the fulfillment of my important and sacred duties.

For this reason, unable to do otherwise, I have left for a time the affairs of the Cause, both at home and abroad, under the supervision of the Holy Family and the headship of the Greatest Holy Leaf - may my soul be a sacrifice to her - until, by the Grace of God, having gained health, strength, self-confidence and spiritual energy, and having taken into my hands, in accordance with my aim and desire, entirely and regularly the work of service, I shall attain to my utmost spiritual hope and aspiration.

The servant of His Threshold,

Shoghi

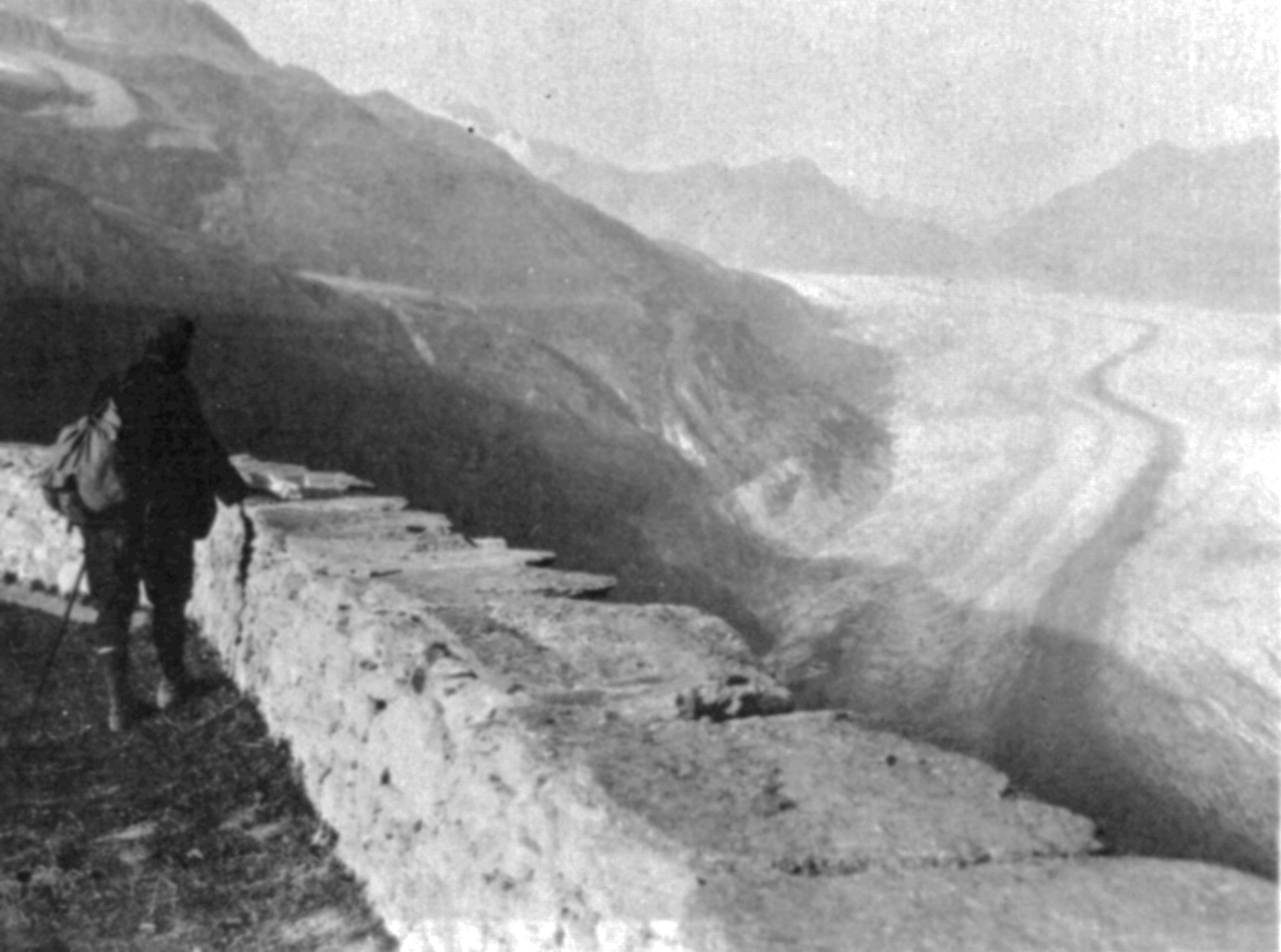

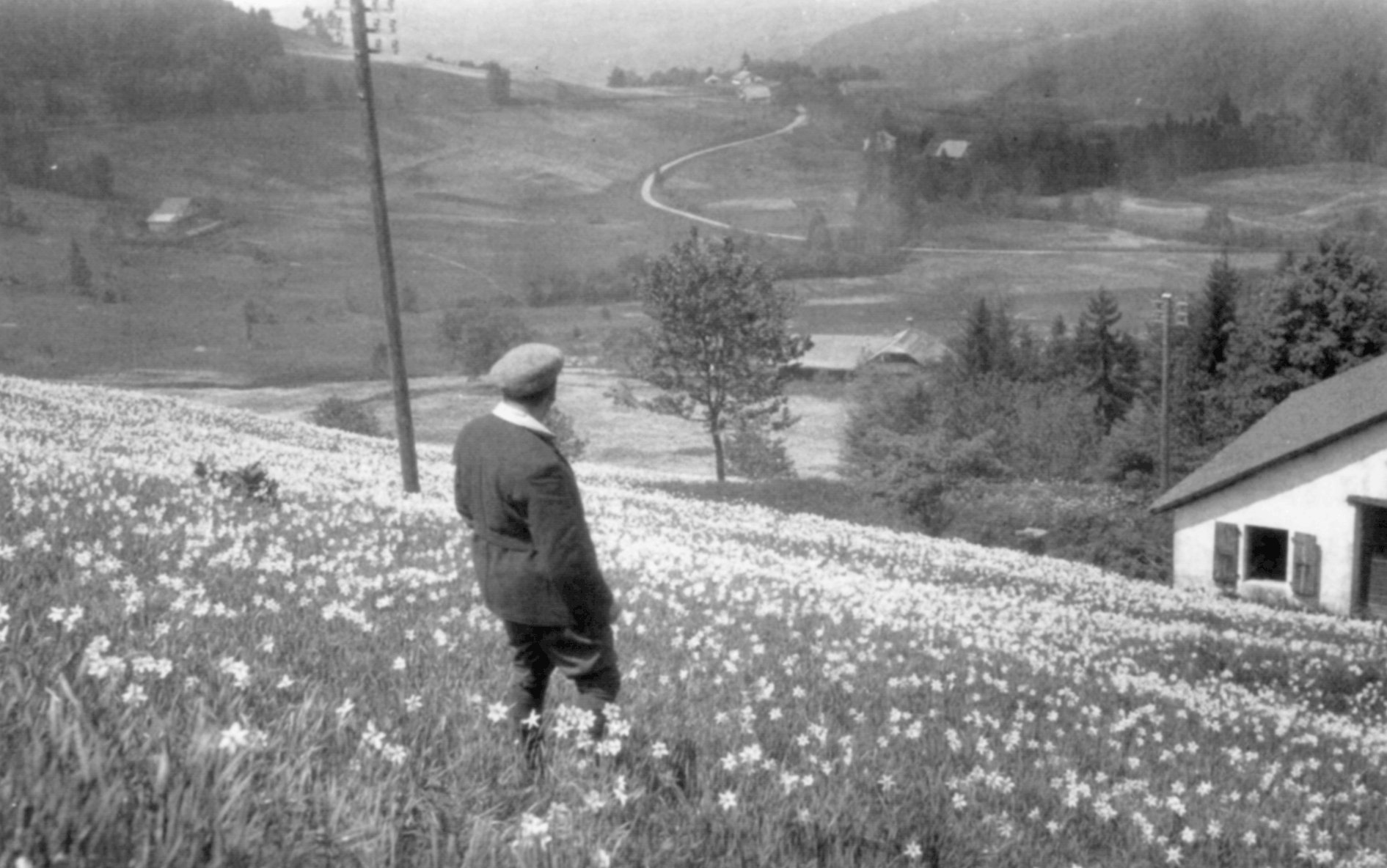

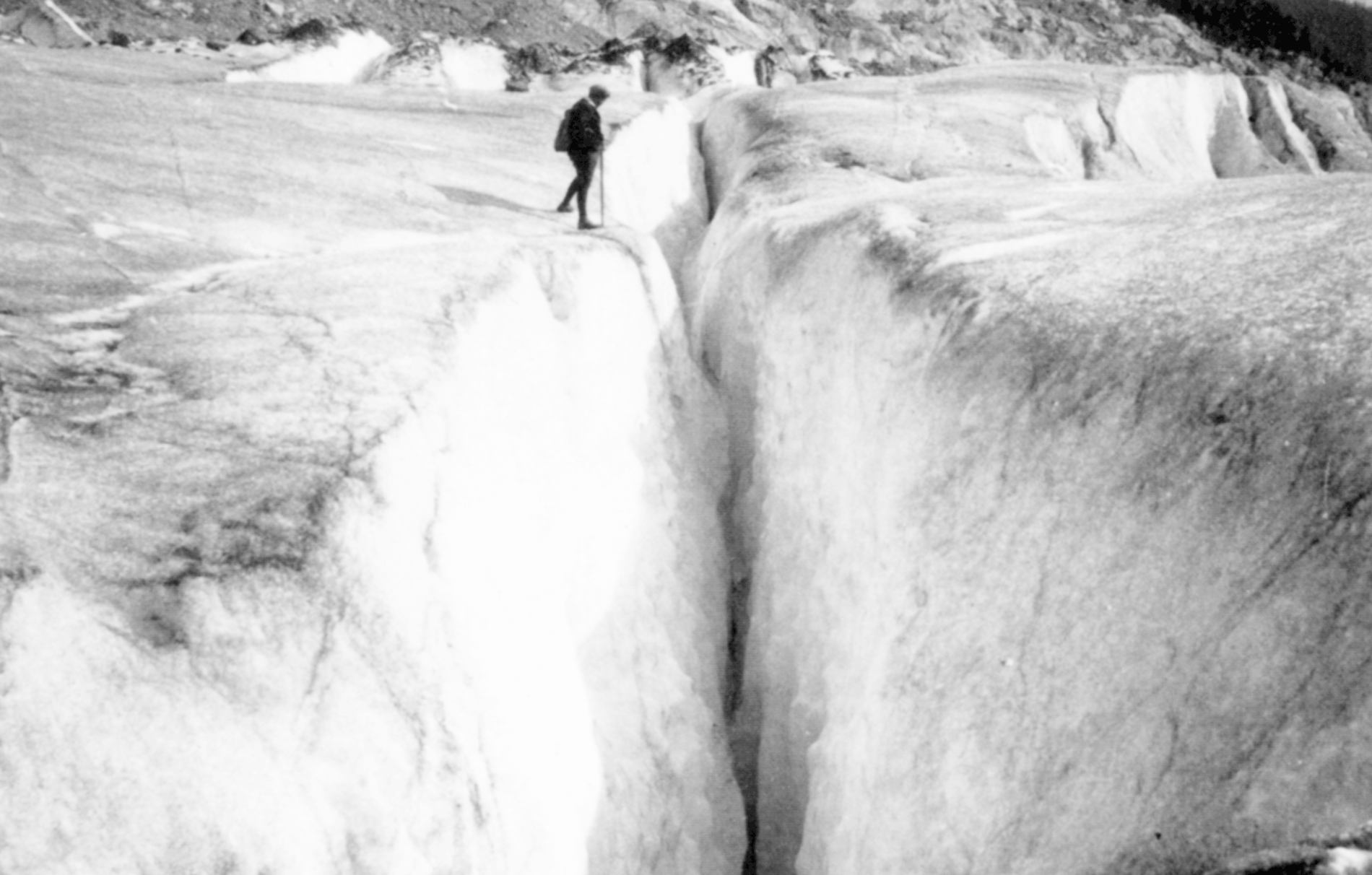

Shoghi Effendi looking over a low wall down to a glacier. Source: The Priceless Pearl.

Shoghi Effendi first traveled to Germany to consult doctors, and they found something deeply alarming: Shoghi Effendi had almost no reflexes left. After Germany, Shoghi Effendi spent time in Switzerland and its Bernese Oberland, which would become his second home. Shoghi Effendi loved its alluring mountains, and he particularly appreciated his host, Mr. Hauser an old Swiss mountain guide, in the town of Interlaken. He would remain close to Mr. Hauser for years, spending many summers in his cabin.

Shoghi Effendi loved good, simple people, and had a very close relationship with Mr. Hauser, corresponding with him regularly when he returned to the Holy Land, and exchanging photographs and small gifts.

For years, Shoghi Effendi rented Mr. Hauser’s tiny attic, paying one Franc a night. The ceiling was so low that guests had to hunch over, and Shoghi Effendi’s furnishings were very simple: a small bed, and a pitcher of cold water to bathe.

From Interlaken, Shoghi Effendi would hike the Bernese Oberland for 16 hours on end, sometimes hiking 40 kilometers in one day, and he found healing in his exertions in the wilderness and fresh mountain air.

Shoghi Effendi commemorated the anniversary of the passing of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, alone in Switzerland.

Years later, Shoghi Effendi spoke to Leroy Ioas about his reason for leaving the Holy Land. The position entrusted to him by 'Abdu'l-Bahá in His Will was so overwhelming to him, at the time, he felt like he did not want to be the Guardian, and did not want to face the responsibilities. And he told Leroy:

I left the Holy Land, and I went up into the mountains of Switzerland, and I fought with myself until I conquered myself.

Bahíyyih Khánum, the Greatest Holy Leaf, the daughter of Bahá'u'lláh and Ásíyih Khánum, and the sister of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, around 1895 at the age of 49. Source: Bahaipedia.

Starting with his very first Riḍván as the Guardian of the Cause of Bahá'u'lláh, the Greatest Holy Leaf began a 48-month letter campaign with the Bahá'ís of every corner of the world from Persia and Pakistan to America.

The Greatest Holy Leaf wrote to individual Persian Bahá'í communities—villages, towns and cities—Hamadán, Ḥusayn-Ábád, Miyánáj, Qazvín, Shíráz, Shishaván (Ádhirbáyján), Tabríz, and Takúr in Persia, to the United States, and to Karachi, Pakistan.

She wrote to Spiritual Assemblies, to individuals, and to the worldwide Bahá'í community in the East and West, rallying them, one and all to the Covenant and to the youthful Guardian.

To the local and national Bahá'í communities from Pakistan to the United States, receiving these touching, personal letters directly from the Greatest Holy Leaf must have been deeply impressive and unforgettable. Every Bahá'í knew the Greatest Holy Leaf, born during the Dispensation of the Báb, the saintly daughter of Bahá'u'lláh, who had followed her Father to each of His four exiles, the cherished sister of 'Abdu'l-Bahá—only two years younger than Him, at His side for 29 years, his closest friend since childhood.

And now the Greatest Holy Leaf was writing to the entire world calling them to gather under the protective shade of the Guardian.

In these letters, Bahíyyih Khánum poured out her love for the Guardian and showcased her considerable talent as a writer forging in every single letter a new and beautiful way to refer to the Guardian never once repeating the same exact sentence.

Portrait of Bahíyyih Khánum, the Greatest Holy Leaf, from Bahíyyih Khánum: The Greatest Holy Leaf by Bahá'u'lláh, Abdu'l-Bahá, Shoghi Effendi, and Bahíyyih Khánum compiled by the Research Department of the Universal House of Justice, between pages 156 and 157.

Below are the 49 ways in which the Greatest Holy Leaf refers to Shoghi Effendi in the 21 excerpts below, excerpted from the Universal House of Justice’s Fiftieth anniversary compilation called Bahíyyih Khánum.

- A most great favour

- A wondrous gift

- An incomparable cure

- Branch that has Branched from the two hallowed and sacred Lote-Trees

- Chosen branch

- He to whom the people of Bahá must turn

- His Eminence

- No dazzling gem could rival such a precious pearl

- No gift could equal this

- Shoghi Effendi

- Shoghi Effendi Rabbani

- The appointed Centre

- The authorized Point to whom all must turn

- The blest and sacred bough that hath Branched out from the Twin Holy Trees

- The bough that has Branched out from the twin heavenly Trees

- The bough that has grown from the two offshoots of the celestial glory

- The Centre

- The centre and focus of all on earth

- The Centre of His Cause

- The Centre of the cause

- The Centre of the Faith

- The Centre on which the concourse of the faithful must fix their gaze

- The Centre toward whom all the people of Bahá must turn

- The concealed mystery

- The cure most exquisite, most glorious, most excellent, most powerful, most perfect, and most consummate

- The designated Centre

- The explicitly Chosen Branch

- The Expounder of the Holy Writings

- The goodly and precious legacy

- The Guardian

- The Guardian of His Covenant

- The Guardian of the Cause

- The Guardian of the cause of god

- The Guardian of the Faith

- The highly potent remedy

- The Interpreter

- The interpreter of the Book

- The interpreter of the Book of God

- The Interpreter of the Holy Book

- The Interpreter of the holy writ

- The Leader

- The one appointed to guide the administration of the Cause

- The one to whom all must turn

- The one to whom all the people of Bahá must direct themselves

- The one toward whom all must turn

- The one toward whom must turn all those who follow Bahá'u'lláh

- The Specific Centre

- The specifically named Centre

- The well-guarded secret

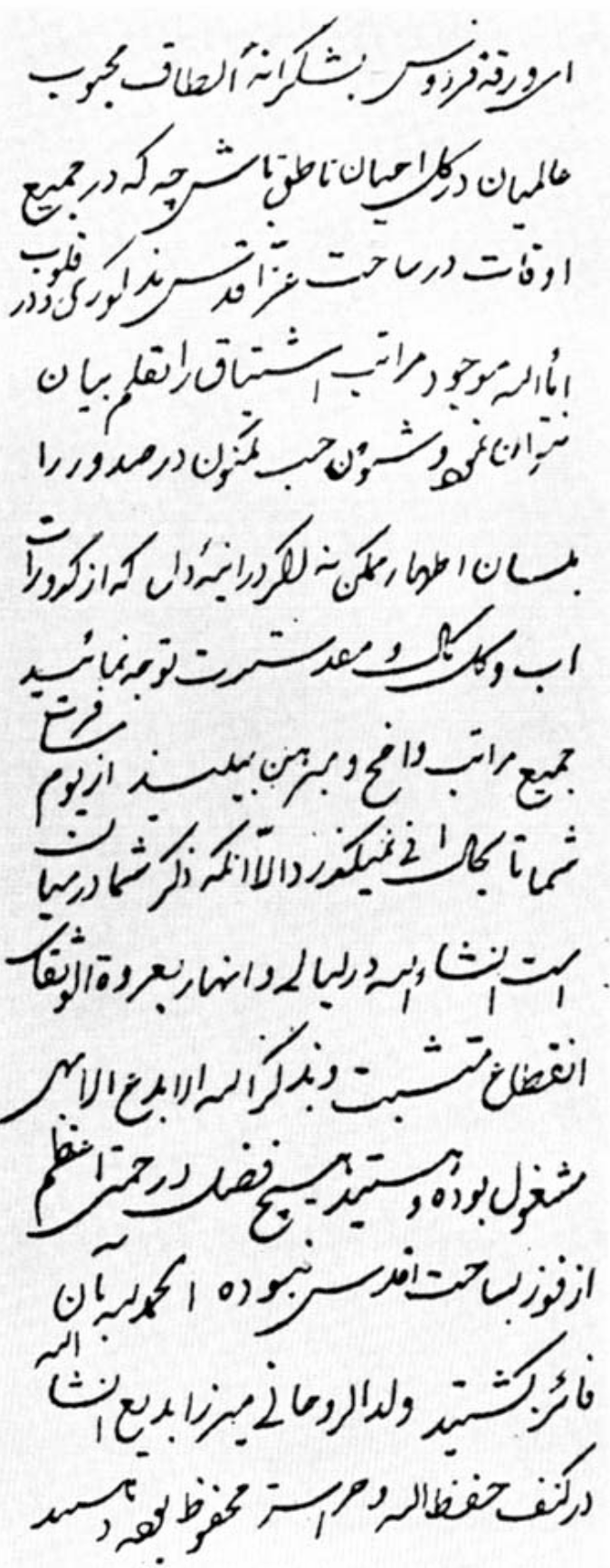

Facsimile of the Persian handwriting of Bahíyyih Khánum, the Greatest Holy Leaf, from Bahíyyih Khánum: The Greatest Holy Leaf by Bahá'u'lláh, Abdu'l-Bahá, Shoghi Effendi, and Bahíyyih Khánum compiled by the Research Department of the Universal House of Justice, between pages 156 and 157.

Here are the 20 excerpts of letters written by Bahíyyih Khánum, the Greatest Holy Leaf, between 21 April 1922 and 27 May 1924 to the Bahá'ís of the east and west, calling them to pledge allegiance to the Guardian:

We are more than thankful to God that He has not left us without a leader, but that Shoghi Effendi is appointed to guide the administration of the Cause. We hope that the friends of God, the beloved and the handmaidens of the Merciful, will pray for us, that we may be enabled to help Shoghi Effendi in every way in our power to accomplish the Mission entrusted to him.

April/May 1922 to the Bahá'ís in America:

Praised be the undying glory of God that you and all His friends have attained this greatest of gifts. You stand fast-rooted in the divine Covenant, and you turn to the appointed Centre, the explicitly chosen Branch. In all the world, what conceivable bounty could ever be greater than this?

April/May 1922 to the Bahá'ís in America:

He has specifically named the centre to whom all must turn, thus solidly fixing and establishing the foundations of the Covenant, and has clearly appointed the centre, to whom all the people of Bahá must direct themselves, the Chosen Branch, the Guardian of the Cause of God. This great bestowal is one of the special characteristics of this supreme Revelation, which of all Dispensations is the noblest and most excellent. Goodly be this to the steadfast, glad-tidings to the staunch, blessings to those who win the day.

April/May 1922 to a believer in Tabríz:

[P]raised be God, He Who is the Dayspring of the Covenant has appointed in writing a specific centre, and designated the Guardian of the Cause, Shoghi Effendi, as the one toward whom must turn all those who follow Bahá'u'lláh—His purpose being that the Faith of God and His Cause should remain secure and safe. For this greatest of gifts it is fitting that we should return a thousand thanks to the one Beloved, and offer a thousand praises to His court of holiness.

April/May 1922 to a believer in Qazvín:

The Will and Testament of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá is His decisive decree; it gathers the believers together; it preserves their unity; it ensures the protection of the Faith of God. It designates a specific Centre, irrefutably and in writing establishing Shoghi Effendi as Guardian of the Faith and Chosen Branch, so that his name is recorded in the Preserved Tablet, by the fingers of grace and bounty. How grateful should we be that such a bounty was bestowed, and such a favour granted.

May/June 1922:

That blessed Being perfected His bounties for the people of Bahá, and His grace and favour were extended to those of all degrees. In the best of ways, he manifested at the end what had been shown forth at the beginning, crowning all His gifts with His Will and Testament, in which He clearly made known the obligations devolving upon every stratum of the believers, in language most consummate, comprehensive and sound, setting down with His own pen the name of Shoghi Effendi, as Guardian of the Cause and interpreter of the Holy Writ. The first of His bounties was the light He shed, the last of His gifts was that He unravelled the secrets by lifting the veil.

God be praised, all the beloved of God's Beauty are immersed in an ocean of bounty and grace, all are receiving abundant bestowals from the lights that radiate from that Countenance of glory.

May/June 1922 to a believer in Karachi:

All are firmly rooted in the Faith, steadfast, turning with complete devotion to him who is the appointed and designated Centre, the Guardian of the Cause of God, the Chosen Branch, His Eminence Shoghi Effendi; are founding Assemblies, conducting meetings, teaching most eloquently and with all their energies, presenting proofs, disseminating the doctrines of the Divine Beauty and the counsels of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá .

On 22 June 1922 to a Bahá'í in Qazvín:

His bounties, His favours to the people of Bahá were made perfect, and extended to every class and kind. And as at the beginning, so at the end: His final bestowal of all, a crowning adornment, was His Will and Testament. Here, to Bahá'ís of every degree, in the clearest, most complete, most unmistakable of utterances, He described the obligation of each one, explicitly appointed, irrefutably and in writing, the Centre of the Faith, designating the Guardian of the Cause and the interpreter of the Holy Book, His Eminence Shoghi Effendi, appointing him, the Chosen Branch, as the one toward whom all must turn. Thus He closed for all time the doors of contention and strife, and in the best of ways and in a most perfect method He pointed out the path that leads aright.

June/July 1922 to a Bahá'í in Shíráz:

The good news has come that the Will and Testament of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá , may our lives be sacrificed for His meekness, has been read at the meetings of the friends, and we here are rejoiced to learn of their unity and their steadfastness and loyalty, and of their directing themselves toward the designated Centre, the named and specified Guardian of the Cause of God, the interpreter of the Book of God, the protector of His Faith, the keeper of His Law, Shoghi Effendi. This news brought extreme joy.

On 7 July 1922 to a Bahá'í in Takúr, Núr:

Praised be God the Beloved that He has disclosed, through His invisible bounties and visible grace, such secrets, and drawn such veils aside. Words have taken on new meaning, and meaning itself has been adorned with the divine. A clear Covenant makes our duty plain; an explicit and lucid Text explains the revealed Book; a specifically named Centre has been designated, toward whom all must turn, and the pronouncement of him who is the Guardian of the Cause and the interpreter of the Book has been made the decisive decree. All this is out of the grace and favour of our Beloved, the All-Glorious, and the loving-kindness of Him from the splendours of Whose servitude earth and heaven were illumined.

On 10 July 1922 to the Bahá'ís of Ḥusayn-Ábád, Yazd:

The purport of your letter is highly indicative of your steadfastness in His Cause, of your unswerving constancy in the Covenant, of having set your face toward Shoghi Effendi, the authorized Point to whom all must turn, the Centre of the Cause, the Chosen Branch, the bough that has Branched out from the twin heavenly Trees. Indeed, this is the essential thing, this is the meaning of true devotion, this is the unshakable, the indubitable truth whereby the people of Bahá, the dwellers of the Crimson Ark, are distinguished.

On 14 July 1922 to the Bahá'ís of Míyánaj:

A physician treats every illness with a certain remedy and to every painful sore he applies a specially prepared compound. The more severe the illness, the more potent must be the remedy, so that the treatment may prove effective and the illness cured. Now consider, when the divine Physician ['Abdu'l-Bahá] determined to conceal His countenance from the gaze of men and take His flight to the Abhá Kingdom, He knew in advance what a violent shock, what a tremendous impact, the effect of this devastating blow would have upon His beloved friends and devoted lovers.

Therefore He prepared a highly potent remedy and compounded a unique and incomparable cure—a cure most exquisite, most glorious, most excellent, most powerful, most perfect, and most consummate. And through the movement of His Pen of eternal bounty He recorded in His weighty and inviolable Testament the name of Shoghi Effendi —the bough that has grown from the two offshoots of the celestial glory, the Branch that has Branched from the two hallowed and sacred Lote-Trees. Then He winged His flight to the Concourse on High and to the luminous horizon.

Now it devolves upon every well-assured and devoted friend, every firm and enkindled believer enraptured by His love, to drink this healing remedy at one draught, so that the agony of bereavement may be somewhat alleviated and the bitter anguish of separation dissipated. This calls for efforts to serve the Cause, to diffuse the sweet savours of God, to manifest selflessness, consecration and self-sacrifice in our labours in His Path.

4 August 1922, to the Bahá'ís in the West:

Again, I supplicate the Eternal Glory to send down His herald of holiness with the garment in his hands, that all eyes may be solaced and all hearts rejoiced by the return to this country of the Chosen Branch, the Guardian of the Cause of God, Shoghi Effendi, in the briefest of times. This indeed is well within the reach of the bounties of our Almighty and All-Generous Lord.

On 9 August 1922:

All praise be to Bahá'u'lláh! The meaning of those bounties became apparent and the splendour of those bestowals was made manifest: that conclusive Text, the Will and Testament of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá , was given us, and what had been hidden at the beginning was made known at the end. His infinite grace became clearly manifest, and with His own mighty pen He made a perfect Covenant, naming Shoghi Effendi the Chosen Branch and Guardian of the Faith. Thus, by God's bounty, what had been a concealed mystery and a well-guarded secret, was at last made plain.

This greatest of bestowals came as a lightning-flash of glory to the righteous, but to those evil ones who broke the Covenant, it was the thunderbolt of God's avenging wrath.

20 Muharram 1341 A.H. (12 September 1922 A.D.)

You have offered up thanks to the Lord for appointing the Centre of His Cause and the Guardian of His Covenant, and have voiced your gratitude and expressed your spiritual sentiments, for this favour and grace. It is true, in all the world there could be no mercy greater than this, no bounty more abundant. 'Abdu'l-Bahá, may our lives be sacrificed for His sacred dust, has bestowed on us a wondrous gift, a most great favour. He has clearly shown us the highway of guidance and explicitly designated the Centre toward whom all the people of Bahá must turn, and with His own bounteous pen has written down for us what will ensure prosperity and progress, and salvation and bliss, for evermore.

On 14 September 1922 to the members of the Spiritual Assembly of Shíshaván, a village in Ádhirbáyján:

In its every aspect, this noblest of Dispensations and greatest of eras is something set apart, for it is most exalted, most glorious, and distinguished from the past. In no wise is it to be compared with the ages gone before. So plainly, in this mighty day, have the mysteries been laid bare, that to the perceptive and the initiated and those who have attained the knowledge of divine secrets, they appear as tangible realities. In this new Day the stars of allusions and hints have fallen, for the Sun of explicit texts has risen, and the Moon of expositions and interpretations has shone above all horizons. As expressly stated in the Holy Text, a specific Centre has been given us. With His own pen has ‘Abdu’l-Bahá , the Centre of the Covenant, selected and appointed Shoghi Effendi, the Chosen Branch, the Guardian of the Cause of God, the interpreter of the Book of God, so that the highway of divine guidance has been clearly marked out and lighted up for all the ages to come. This bounty is one of the distinguishing features of this mightiest of Dispensations, a special grace allotted to this age.

ON 11 December 1922:

Today as well, the Chosen Branch, the Guardian of the Cause of God, is at all times waiting expectantly —and indeed, it is the most cherished desire of his heart—to see this reality, this proof of serious effort, this feature that distinguishes the Bahá'ís from all others, clearly and unmistakably revealed in the life of every single Bahá'í.

On 28 March 1924 to the members of the Spiritual Assemblies and all the Friends of God in the East

Let us call to mind the clear statements and the warnings revealed by the Blessed Beauty, and the explanations and commentaries of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá , particularly as found in His Will and Testament. This Testament was the last song of that Dove of the Rose-garden of Eternity, and He sang it on the Branch of the Tree of bestowal and grace. It was His principal gift, indeed the greatest of all splendours that radiated forth from that Day-Star of bounty, out of the firmament of His bestowals. This Testament was the strong barricade built by the blessed hands of that wronged, that peerless One, to protect the garden of God's Faith. It was the mighty stronghold circling the edifice of the Law of God. This was an overflowing treasure which the Beloved freely gave, a goodly and precious legacy, left by Him to the people of Baha. In all the world, no gift could equal this; no dazzling gem could rival such a precious pearl.

With His own pen, He designated as Guardian of the Cause of God, Shoghi Effendi Rabbani, the Chosen Branch, and made him the 'blest and sacred bough that hath Branched out from the Twin Holy Trees,' to be the one to whom all must turn, the centre and focus of all on earth.

On 27 May 1924 to the Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá'ís of Hamadán:

The essential point is this: praise be to God, the way of His holy Faith is laid straight, the Edifice of the Law of God is well-founded and strong. He to whom the people of Bahá must turn, the Centre on which the concourse of the faithful must fix their gaze, the Expounder of the Holy Writings, the Guardian of the Cause of God, the Chosen Branch, Shoghi Effendi, has been clearly appointed in conformity with explicit, conclusive and unmistakable terms. The Religion of God, the laws and ordinances of God, the blessed teachings, the obligations that are binding on everyone—all stand clear and manifest even as the sun in its meridian glory. There is no hidden mystery, no secret that remains concealed. There is no room for interpretation or argument, no occasion for doubt or hesitation. The hour for teaching and service is come. It is the time for unity, harmony, solidarity and high endeavour.

The very first National Convention in the United States: The First Temple Unity on 21 March 1909, the day that 'Abdu'l-Bahá interred the remains of the Báb on Mount Carmel in Haifa. Source: Bahaipedia.

It is important to remember that although the National Spiritual Assembly of the United States and Canada was formed in 1922, the Guardian would not officially count it as a National Spiritual Assembly until three years later in 1925, when its elections were duly and properly standardized.

The second week after Shoghi Effendi had left Haifa for his long withdrawal in Europe, the 14th national convention of the United States took place. This was a historic convention, because it was the first time they elected a National Spiritual Assembly of the United States, at Shoghi Effendi’s instructions and replacing the older Executive Board of Bahá'í Temple Unity. The work of the Bahá'í Faith in North America was going to develop in a completely new environment.

Mountfort Mills spoke about Shoghi Effendi to the American Bahá'í Convention about their young Guardian:

Think of what he stands for today! All the complex problems of the great statesmen of the world are as child's play in comparison with the great problems of this youth, before whom are the problems of the entire world...No one can form any conception of his difficulties, which are overwhelming...the Master is not gone.

His Spirit is present with greater intensity and power...In the center of this radiation stands this youth, Shoghi Effendi. The Spirit streams forth from this young man.

He is indeed young in face, form and manner, yet his heart is the center of the world today. The character and spirit divine scintillate from him today. He alone can...save the world and make true civilization. So humble, meek, selfless is he that it is touching to see him. His letters are a marvel.

It is the great wisdom of God in grating us the countenance of this great central point of guidance to meet difficult problems…This foundation is being laid, sure and certain, by Shoghi Effendi in Haifa today.

Roy Wilhelm also shared an important testimony of the Guardian:

When one reaches Haifa and meets Shoghi Effendi and sees the workings of his mind and heart, his wonderful spirit and grasp of things, it is truly marvelous.

Although not in Haifa when the Convention took place, Shoghi Effendi had somehow arranged to be present in spirit, and he had thoughtfully sent the gathered friends a bunch of violets, carried by a return pilgrim who conveyed his love to all the Bahá'ís.

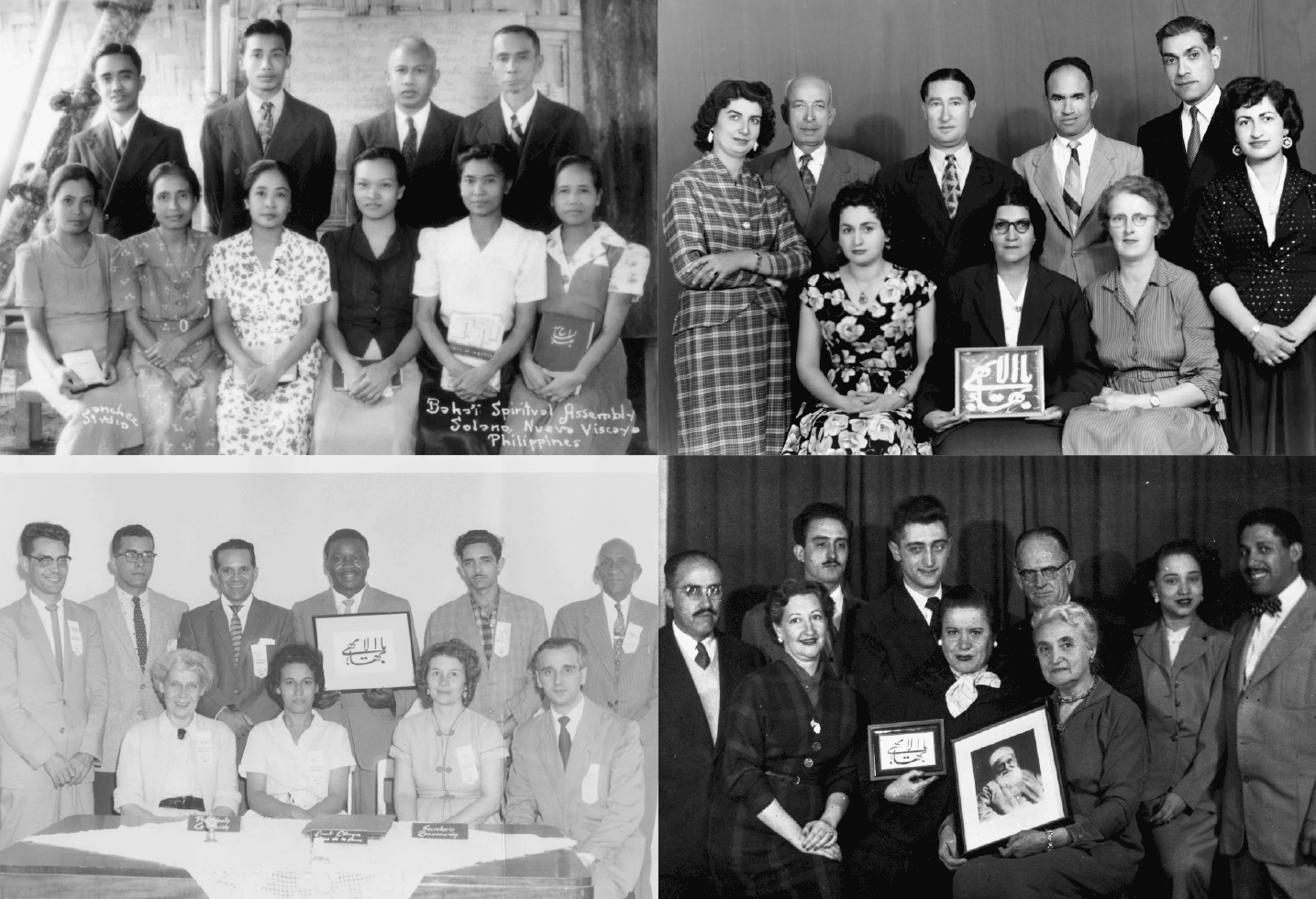

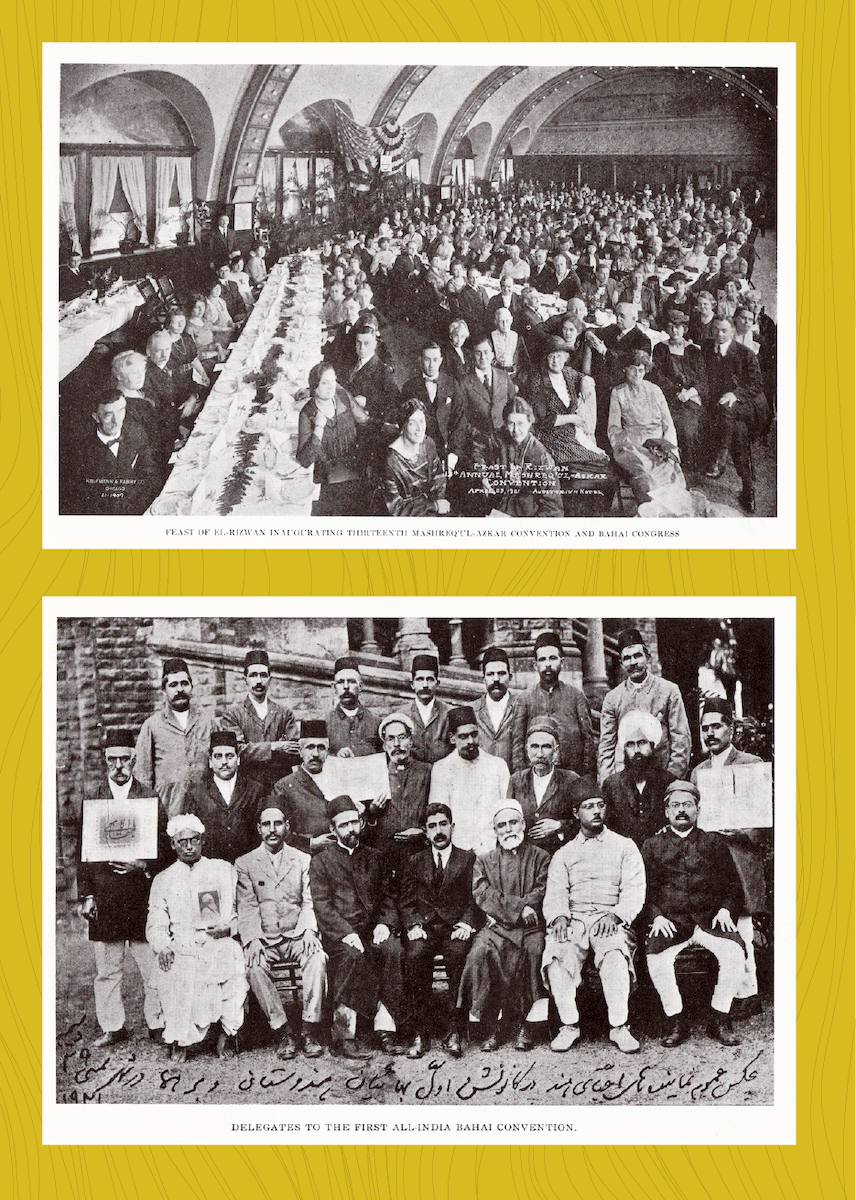

“The state of the worldwide Bahá'í Administrative Order”: Two very early institutions of the Bahá'í Administrative Order in 1922: Top: Naw-Rúz feast inaugurating the United States and Canada’s 13th Mashriqu’l-Adhkár’s Convention and Congress. Source: Star of the West Volume 12, Number 4, page 66. Bottom: Delegates to the All-India Bahá'í Convention. Source: Star of the West Volume 12, Number 1, page 20.

In 1922, there was only one National Spiritual Assembly to speak of, the National Spiritual Assembly of the United States and Canada, that had evolved from its original “Temple Unity” body, elected since 1909. They had the most administrative experience, 13 years more than all the new National Spiritual Assemblies which were elected in 1922 – 1923.

In 1922, the British Bahá'ís spontaneously formed in 1922 a "Bahá'í Council" to foster national affairs.

Germany elected its National Spiritual Assembly with Austria in 1922.

In 1923, India had the beginnings of what would become a real National Assembly, and had Burma’s “Central Council” under its jurisdiction.

The vast majority of Bahá'ís worldwide were still concentrated in Persia and its neighboring countries.

There was a small, loyal, and devoted community in North America, an even smaller one in Europe, and even smaller ones in Africa, the Indian sub-continent and the Pacific.

Most of Bahá'ís around the world in 1922—including the members of 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s family—did not clearly understand what the Bahá'í Faith truly represented, they had absolutely no idea what shape it was about to take under the guiding hand of Shoghi Effendi, and they did not know what the Bahá'í Administrative Order was.

Although there were Spiritual Assemblies in local areas, they had many different names, their functioning was not systematized, and their membership was vague, at best.

Shoghi Effendi was a born administrator, and he would spend the next 36 years establishing, consolidating, systematizing, guiding, assisting, and correcting the establishment of National Spiritual Assemblies, Local Spiritual Assemblies.

He would build the Administrative Order, gradually, consistently, and unerringly.

During the first two or three years of his ministry, Shoghi Effendi kept lists and data on the countries and local communities he wrote to. After 1925, the pressures of his correspondence was such that he could no longer keep track of the number of letters and cables he was sending and where, and he lacked qualified administrators to help him in his work. It was almost impossible for the Guardian to handle everything alone, another reason why was it was vital for him to leave the Holy Land for a few months each year and simply not work, for him to be able to continue to work the coming year.

From 1922 to 1925, Shoghi Effendi kept lists of the countries he wrote to: America, Britain, France, Germany, Japan, Mesopotamia, Caucasus, Persia, Turkistan, Turkey, Australia, Switzerland, India, Syria, Italy, Burma, Canada, Pacific Islands, Egypt, Palestine, Sweden and Europe.

Also between 1922 and 1925, he wrote to local communities in America, Europe, North Africa, the Middle and Far East, and he kept lists of these, as well:

- From 1922 – 1923, Shoghi Effendi wrote to 67 local communities

- From, 1923 – 1924, he wrote to 88 local communities

- And from 1924 – 1925, the last period for which he kept statistics, he wrote to 96 local communities

Even though there are only three years of data, it is clear that the number increased significantly from year to year. And now, imagine what these numbers would have been in 1935, in 1949, in 1953, in 1957.

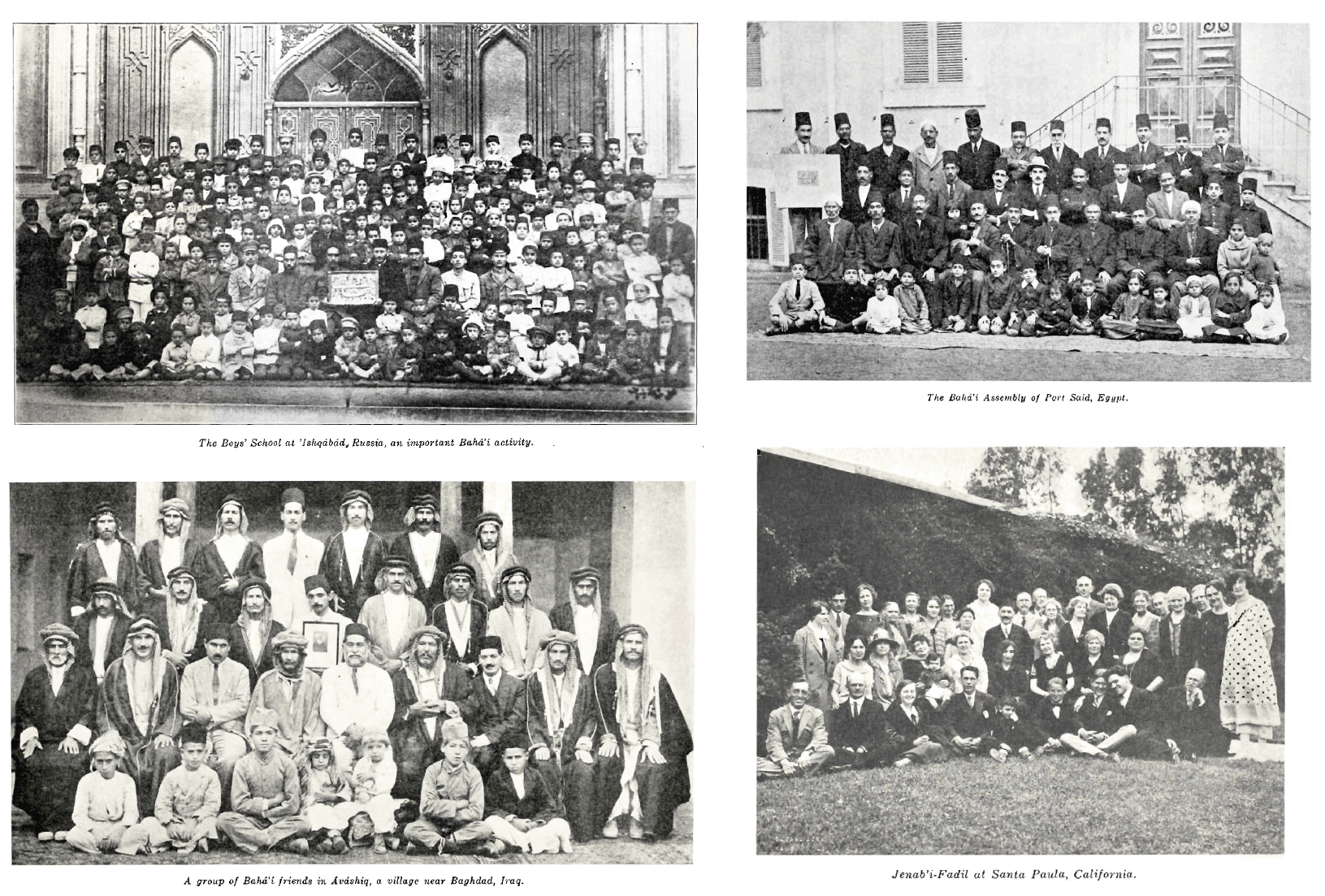

Top left: The boys’ school in ‘Ishqábád, Turkmenistan; Top right: The Bahá’í Assembly of Port Said, Egypt; Bottom left: A group of Bahá’ís in Áváshíq, near Baghdad, Iraq; Bottom right: The Bahá’ís of Santa Paula, California, United States. Source: The Bahá'í World Volume 1 (1924-1926): pages 110, 44, 34, and 106 .

Most Bahá'í communities in the world in 1922 had national and local customs that were not compatible with Bahá'í law.

In Persia, there was an overlap with Muslim culture, and monogamy was neither properly understood or strictly practiced. Bahá'ís still used opium and drank alcohol, something that western Bahá'ís also did.

In America, Bahá'ís were still attached to their churches, and had membership in secret societies.

Bahá'ís weren’t aware that they were to shun all political affiliations and activities.

What the Guardian did to address these issues throughout his entire ministry was a two-fold approach.

First, Shoghi Effendi created a universal, consistent and coherent method of carrying on Bahá'í community life and organizing its affairs, based on the Teachings and the Master's elaboration of them.

Second, he patiently educated Bahá'ís to help them understand the objectives and implications of their religion and the truths enshrined in it.

Munírih Khánum and Bahíyyih Khánum, the Greatest Holy Leaf. Source: Twitter.

By the first anniversary of the Ascension of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, 28 November 1922, Shoghi Effendi had been gone eight months.

The Greatest Holy Leaf had done her best to field all the issues that had happened in Haifa, in the Holy Land, in Persian, in the United States and Canada, and all she had protected the Faith from all the Covenant-breaking activity, but she was at the end of her strength.

On 28 November 1922, Munírih Khánum, 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s widow, wrote her first “Letter of Lament”—she would write three in total—and mentioned how Shoghi Effendi’s prolonged absence had taken its toll on Bahíyyih Khánum, causing her extreme anxiety:

Lord, Lord, Thou seest and knowest that these grieving hearts have lost all patience and strength. The thin thread of endurance is breaking. Resolution and tenacity have come to an end. The absence of the Most Excellent Branch [Shoghi Effendi],[1] and the lack of any news from Him have completely sapped the strength of the Greatest Holy Leaf [Bahíyyih Khánum], and of Rúḥá, the Holy Leaf ['Abdu'l-Bahá's daughter]. No longer is there vigor or strength or forebearance.

The Greatest Holy Leaf needed Shoghi Effendi back in Haifa.

One night—most probably sometime in early to mid-December 1922—Shoghi Effendi was returning from one of his all-day hikes and was stunned to find his mother and a relative looking for him in the street of a small mountain village.

They had been sent by the Greatest Holy Leaf.

Ḍíyá‘íyyih Khánum tearfully told Shoghi Effendi about Bahíyyih Khánum’s distress at his prolonged absence and convinced him to return to Haifa.

It was time to go home.

“Refreshed spirit” Photo of the Swiss Alps: Marco Meyer on Unsplash.

Shoghi Effendi arrived in Haifa on Friday afternoon, 15 December 1922, happy and in radiant health.

Switzerland had worked its magic, and it is nowhere more obvious than in Shoghi Effendi’s own words. These are excerpted from letters and cables, to at least 10 different countries, which you can read in full in the Priceless Pearl by Rúḥíyyih Khánum, pages 623-67. Here, for the purposes of this chronology, only the relevant phrases are excerpted, to show how critical, how important, how vivifying, how life-changing these months were to Shoghi Effendi, and to help us all understand why he would need these long breaks every year. The benefit of the crips mountain air and invigorating hikes re-created our Guardian, year after year.

Here are Shoghi Effendi’s own words about his health for the first week after he returned from Switzerland, which eloquently show the improvement in his health and outlook:

[have now] returned to the Holy Land with renewed vigour and refreshed spirit.

…refreshed and reassured I resume my arduous duties…

…such a needed retirement…

With feelings of joyful confidence…

I pray the Almighty that my efforts, now refreshed and renewed, may with your undiminished support lead it to glorious victory.

Solaced and strengthened, I now join my humble strivings to your untiring exertions for the Cause of Bahá'u'lláh.

I now gladly and hopefully add the further bond of active participation in a life-long service at the Threshold of Bahá'u'lláh.

Refreshed and reassured I now stretch to you across the distant seas my hand of brotherly cooperation in the Cause of Baha.

With zeal unabated and with strength renewed I now await your joyful tidings in the Holy Land.

…my happy return to the Holy Land."

…happily I feel myself restored to a position where I can take up with continuity and vigour the threads of my manifold duties…

…I am now fully restored to health and am intensely occupied with my work…

In a talk in 1978, Hand of the Cause Leroy Ioas reported a conversation he had with the Guardian who explained to him what he had expected upon returning to the Holy Land on 29 December 1921:

I had in mind that Abdu’l-Baha would give me the honor of calling the great conclave, calling together the great conclave which would elect the Universal House of Justice. And I had thought in His Will and Testament, that that probably was what He was instructing to be done. But, instead of that, I found that I had been appointed as the Guardian of the Cause of God, I didn’t want to be the Guardian of the Cause. In the first place, I didn’t think I was worthy. The next days, I didn’t want to face these responsibilities.

The Guardian told Leroy Ioas that once he had been made aware of the contents of the Will and Testament of 'Abdu'l-Bahá and had understood 'Abdu'l-Bahá had appointed him Guardian of the Cause, he spoke about his immediate mindset and why he had to retreat to Switzerland for 8 months:

I didn’t want to be the Guardian. I knew what it meant. I knew that my life as a human being was over. I didn’t want it, and I didn’t want to face it, so as you remember, I left, remember, I left the Holy Land, and I went up in the mountains of Switzerland, and I fought with myself until I conquered myself. Then I came back and I turned myself over to God, and I was the Guardian.

“Piles of mail”: Collage of vintage telegrams and cablegrams.

As soon as news of Shoghi Effendi’s return to the Holy Land spread throughout the Bahá'í world, the Guardian was inundated with a flood of letters and cables from every part of the globe.

Shoghi Effendi was faced with an impossible and thorny problem, which he articulated to one of his distant cousins.

He could not copy 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s method of dealing with incoming correspondence, an unsustainable solution given that the Faith was growing too much and too fast.

He could not respond personally to some Bahá'ís and not others, as this would eventually cause friction and animosity between the believers.

He could not do away with individual correspondence, delegating responses to his associates while he wrote general messages and communicated directly with assemblies. This solution would destroy his personal relationship with the believers.

The problem of how to cope with his mail would weigh on Shoghi Effendi for the entire 36 years of his Guardianship.

In the end, Shoghi Effendi decided to continue answering individuals letters, especially those in western countries and in countries where institutions were not mature enough to deal diplomatically with individuals and not estrange them.

National Spiritual Assemblies sometimes grumbled about this, as it meant that individuals in their country received important information from Shoghi Effendi and they were not informed.

Shoghi Effendi—second from right—with Saichiro Fujita in the front row, and guided the group to holy places in 'Akká and Haifa. Immediately behind Shoghi Effendi is George Latimer. Harry Randall is fourth from the right, behind Saichiro Fujita, Albert Vail is second from the left, and Dr. Luṭfu’lláh Ḥakím—future member of the Universal House of Justice is next to Shoghi Effendi, third from right. Shoghi Effendi has just guided the pilgrims to Holy Places in Haifa and 'Akká. Source: The Network of Bahá'ís of Jewish Background.

It was customary for Shoghi Effendi, in the early days of his ministry to have regular meetings in the Master’s home, and in fact in 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s old reception room, with visiting pilgrims.

Shoghi Effendi preoccupied himself with the welfare of the pilgrims, and he would have a meal with the western pilgrims in the Pilgrim House that was across the street from 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s house on Haparsim street.

With the eastern pilgrims, Shoghi Effendi would visit the Shrines of the Báb and 'Abdu'l-Bahá, and they would all refresh themselves with a cup of tea in the eastern pilgrim house, a stone’s throw from the Shrines on Mount Carmel.

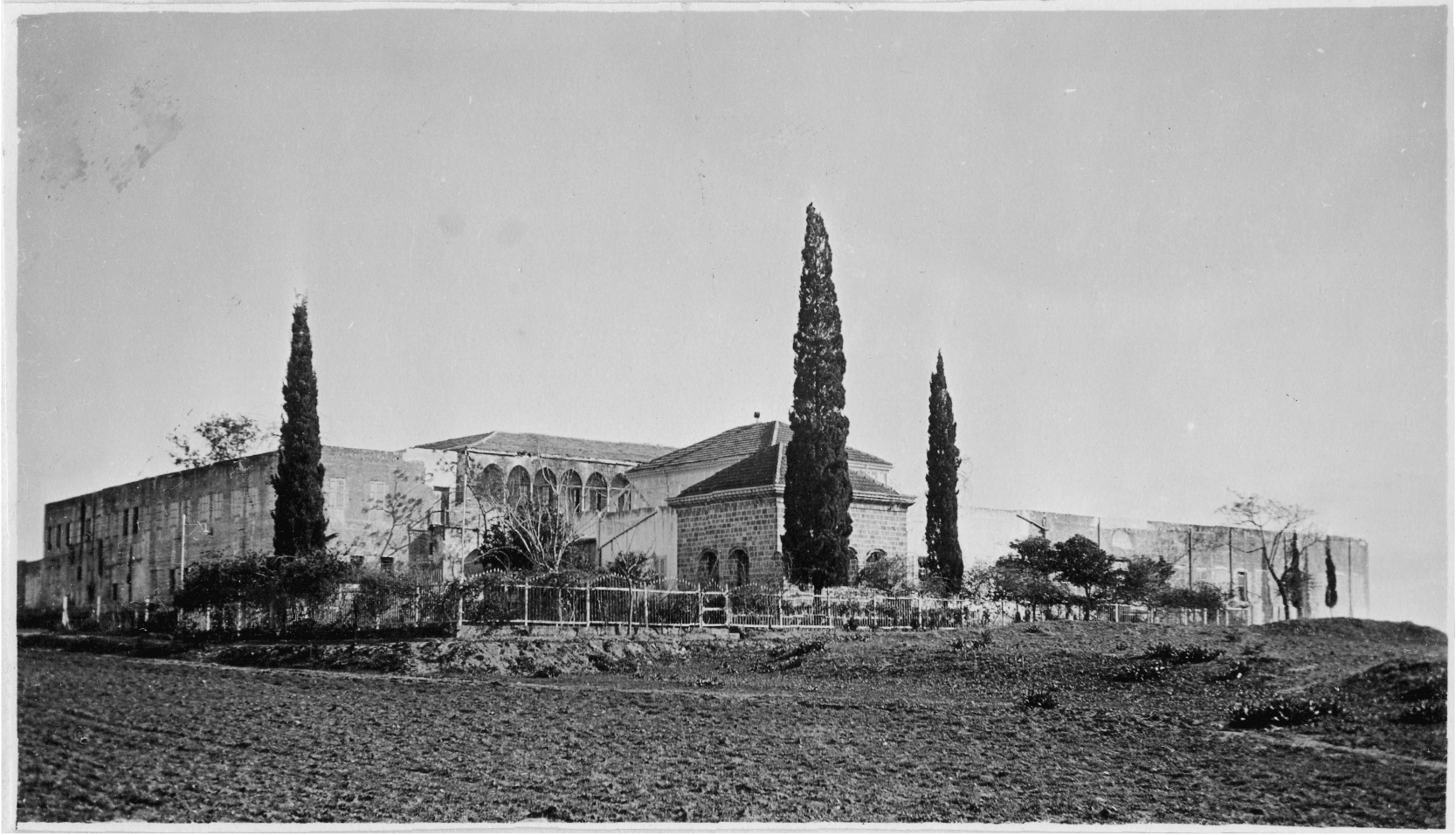

A rare early photograph of Bahjí showing the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh, the Mansion of Bahjí, and the two-story house built by the Covenant-breakers, who stole the keys to the Shrine. © United States National Bahá'í Archives, used with permission.

Ever since 30 January 1922, when Mírzá Muḥammad-'Alí had engineered a plot for Covenant-breakers to seize the keys of the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh, this had been Shoghi Effendi’s most pressing concern.

Since June 1922, the keys of the inner Tomb had been held by the Sub-Governor of 'Akká, both Bahá'ís and Covenant-breakers had access to other parts of the Shrine, the custodian cleaned the Shrine, and everything seemed on indefinite administrative hold.

Shoghi Effendi never for one second stopped to apply insistent pressure on the British authorities, aided in his claim by additional pressure from a united worldwide Bahá'í community.

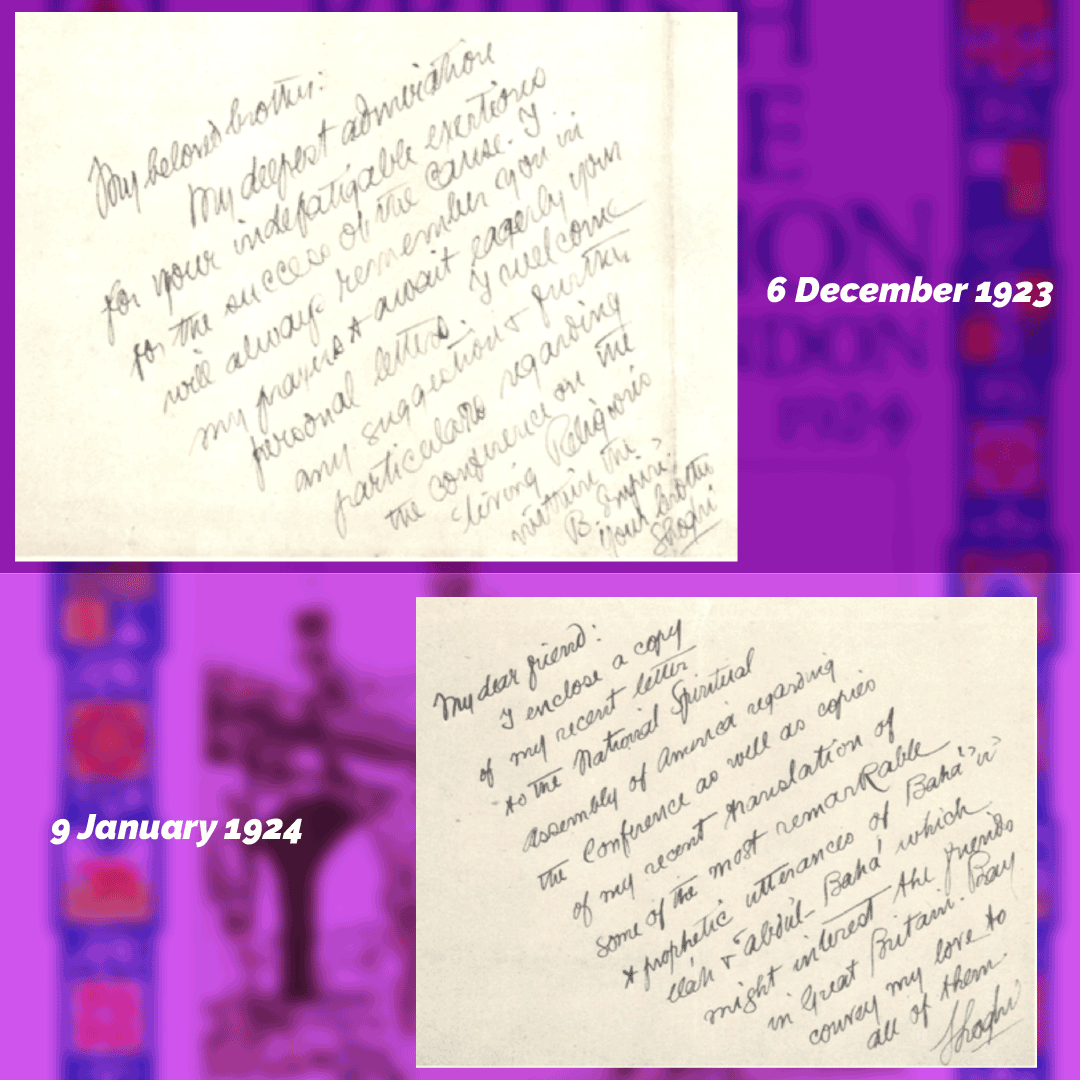

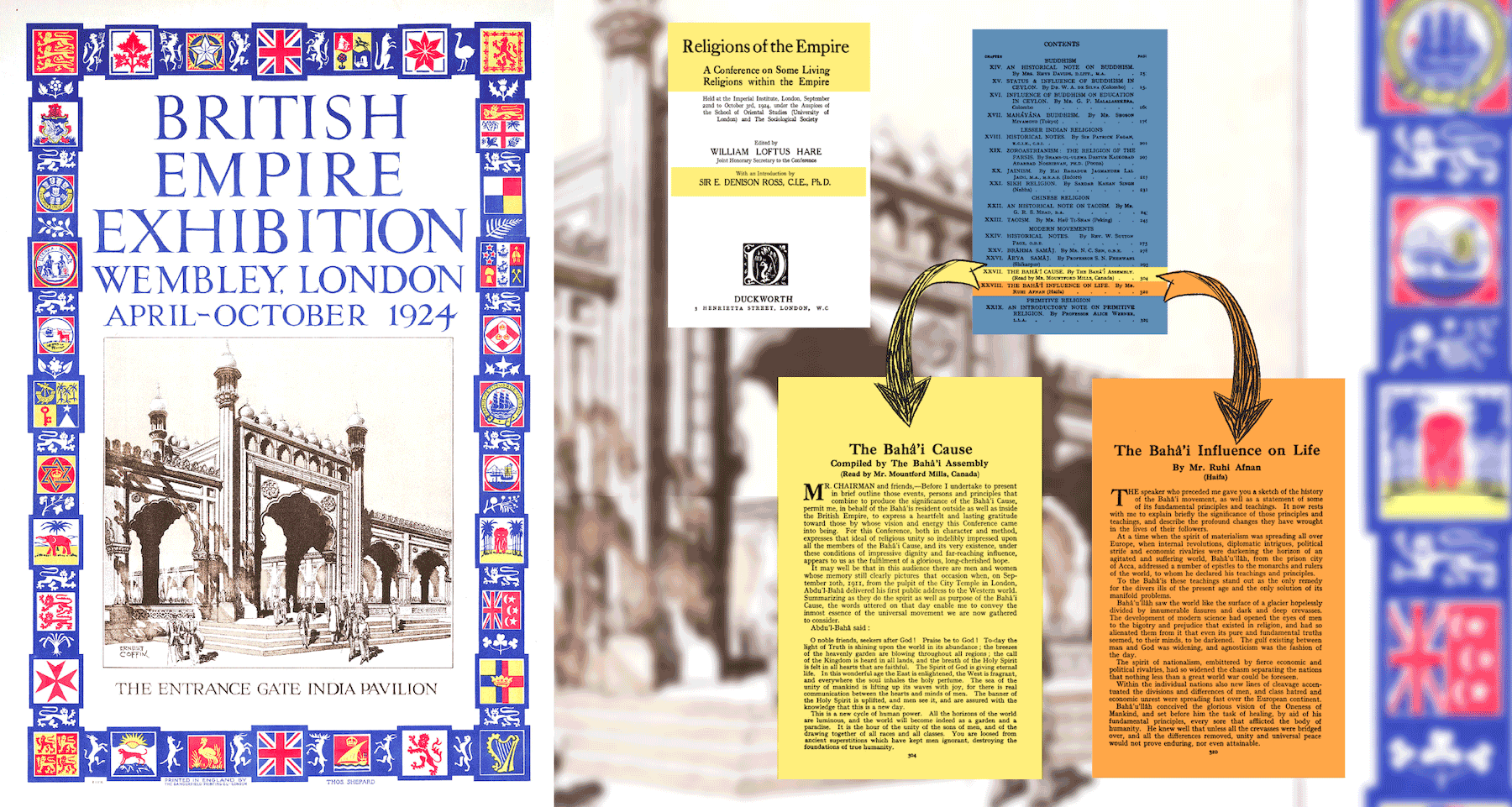

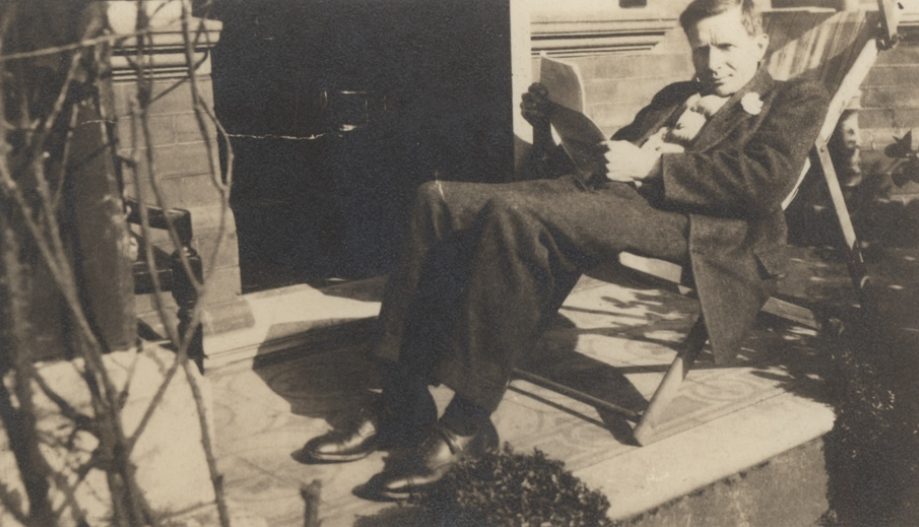

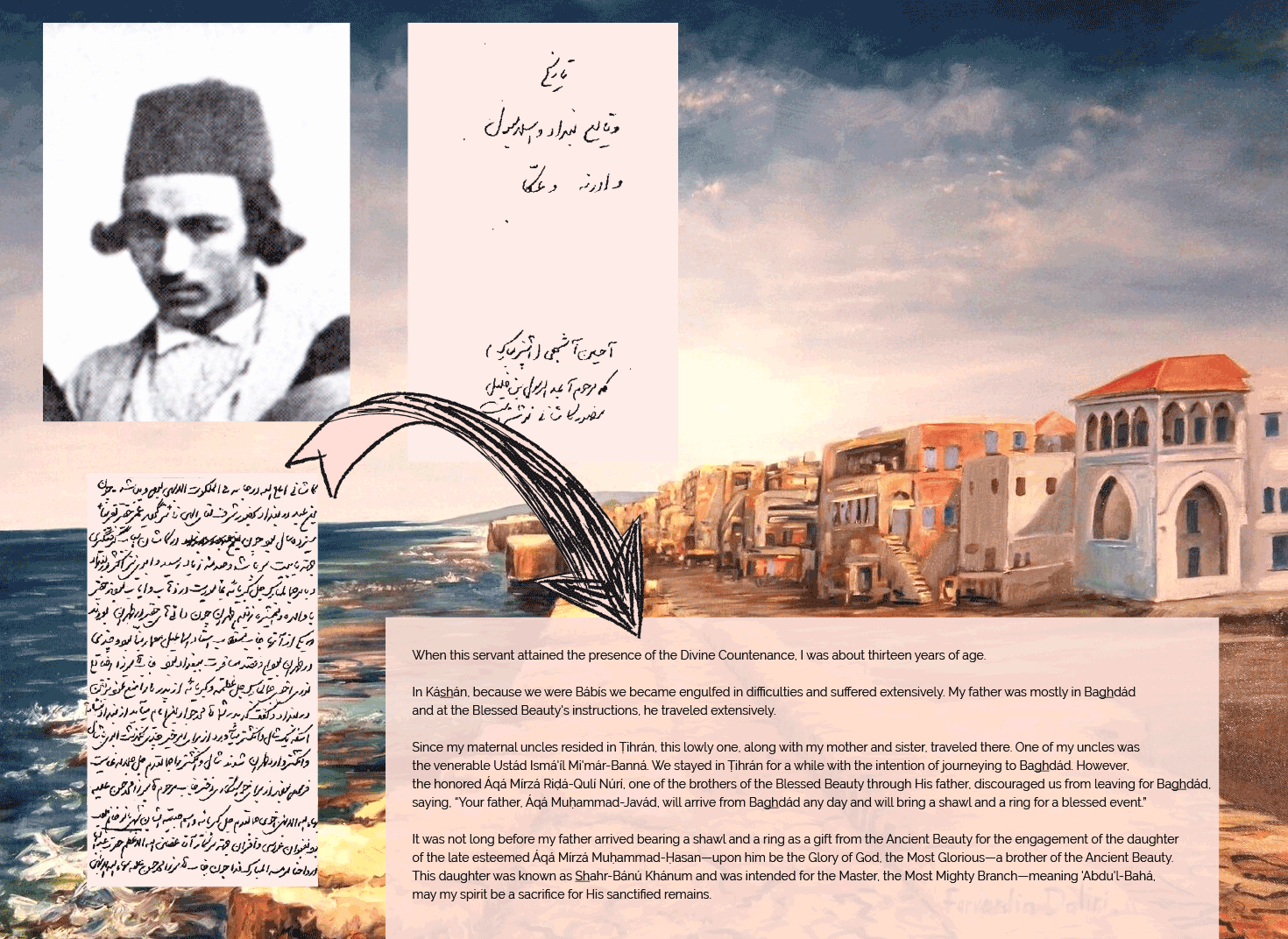

On 7 February 1923 he wrote to Wellesley Tudor Pole about his conversation with Colonel Symes, Governor of Haifa with whom he was on excellent terms, regarding Mírzá Muḥammad-'Alí’s refusal to pay for the policeman who guarded the Shrine: