Written and illustrated by Violetta Zein

This part covers the life of Shoghi Effendi from the age of 24 in 1921 to the age of 25 in 1922.

Collage of photographs of 'Abdu'l-Bahá shortly before His Ascension, showing the Master from a distance, in His gardens or walking away. Source: Violetta Zein, The Extraordinary Life of 'Abdu'l-Bahá: The illustrated chronology of the life of 'Abdu'l-Bahá Part 9: The Ascension of 'Abdu'l-Bahá.

For several years before His passing, and with increasing frequency as the end of His earthly life approached, ‘Abdu'l-Bahá made passing comments about His death, sometimes clear allusion, and at times more subtle references. Here are the most striking.

This story is the first one we were able to find where 'Abdu'l-Bahá alludes to His Passing 8 years prior in Haifa and quoted by Shoghi Effendi in God Passes By:

Remember, whether or not I be on earth, My presence will be with you always.

Recounting His premonitory dreams about His passing was one of the more subtlest ways 'Abdu'l-Bahá would speak about his passing, so subtle it raised absolutely no concern among the friends, it raised no suspicion that 'Abdu'l-Bahá was being serious. This is an example of a dream 'Abdu'l-Bahá recounted around the end of September 1921, two months before His Ascension, also found in God Passes By:

I seemed to be standing within a great mosque, in the inmost shrine, facing the Qiblih, in the place of the Imám himself. I became aware that a large number of people were flocking into the mosque…As I stood I raised loudly the call to prayer. Suddenly the thought came to Me to go forth from the mosque. When I found Myself outside I said within Myself: ‘For what reason came I forth, not having led the prayer? But it matters not; now that I have uttered the Call to prayer, the vast multitude will of themselves chant the prayer.’

It seems alarming that the Bahá'ís would not react when 'Abdu'l-Bahá uttered extremely clear warning signs that He knew He would soon die. In some cases the dreams He recounted were violent, in other cases, he literally said He was going to die. Around 1919, turned to a distinguished visitor of His, seated by Him in His garden, suddenly breaking the silence and said:

My work is now done upon this plane; it is time for me to pass on to the other world.

'Abdu'l-Bahá in the Holy Land, in the year or two prior to His Ascension. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

A few weeks before His passing, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá suddenly entered the room where Shoghi Effendi’s father was and said:

Cable Shoghi Effendi to return at once.

Shoghi Effendi’s mother, Ḍíyá‘íyyih Khánum, consulted with his grandmother, Munírih Khánum, and after consultation, the family decided that to send a cable would risk shocking Shoghi Effendi unnecessarily. They opted instead to write a letter conveying this message, to soften the blow.

When 'Abdu'l-Bahá had asked them to cable Shoghi Effendi, he was in perfect health. The family second-guessed 'Abdu'l-Bahá because they never dreamed He had only a few weeks left to live, and they all lost sight for a critical moment that 'Abdu'l-Bahá was always right and should always be categorically obeyed.

That letter arrived after ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had passed away.

Shoghi Effendi had been deprived of the bounty of seeing His beloved grandfather alive one last time. For the rest of his life, Shoghi Effendi would say, repeatedly, that he felt that if he had been able to see 'Abdu'l-Bahá before His Ascension, he was sure that the Mater would have given him special words of advice, given him instructions and provided him with comfort. But beyond this, he would have been able to gaze one last time upon the beloved face of the single most important person in his life.

Unwittingly, by not strictly obeying ‘Abdu'l-Bahá's directive, they caused Shoghi Effendi a lifelong pain.

This story goes a long way in explaining what Amatu’l-Bahá Rúḥíyyih Khánum calls “the sense of abandonment, of unworthiness, of passionate longing for his grandfather that assailed Shoghi Effendi so strongly during the early years of his Guardianship.”

This photograph of ‘Abdu'l-Bahá as one of the pallbearers of Mírzá Ḥasan Afnán, is one of the last photographs ever taken of the Master. a very grainy, and cropped version of this photograph was published in Star of the West Volume XII, number 18 on page 281. This copy was provided for the chronology courtesy of the National Bahá'í Archives of the United States, uncropped and in high-definition. The caption on the back of the photo reads: "The Master carrying the coffin of Mírzá Abu’l-Ḥasan Afnán on His shoulders. Photo taken by L.S.H. [Luṭfu’lláh Ḥakím, future member of the Universal House of Justice] ten days before the Master's Ascension.”

Ḥájí Mírzá ‘Abu’l Afnán was an eminent Bahá'í and a direct relative of the Báb. He was the son of Ḥájí Mírzá Abú'l-Qásim, the older brother of Khadíjih Bagum, the Báb’s wife. He had lived for a long time in Haifa, and on 19 November 1921, sensing 'Abdu'l-Bahá was about to die and not able to bear that pain, he committed suicide. He was buried the next day, 20 November 1921, after his body washed up on the shore of the Mediterranean and 'Abdu'l-Bahá was one of his pallbearers and walked, carrying his coffin aloft.

'Abdu'l-Bahá implored the friends not to harm themselves:

Should anyone at any time encounter hard and perplexing times, he must say to himself: This will soon pass. Then he will be calm and quiet.

Friday 25 November 1921 was a very busy day for the Master. 'Abdu'l-Bahá attended the last noonday prayer of His life at a Haifa Mosque, then had lunch with the pilgrims, and the last photograph of 'Abdu'l-Bahá was taken on this day. The last Tablet he dictated was to His beloved Bahá'ís of Stuttgart. 'Abdu'l-Bahá insisted on officiating the marriage of and he performed the marriage of Áqá Khusraw, the Burmese servant who had been at his side since he had been freed from slavery at the age of 6 and brought to the Holy Land by a Persian pilgrim. 'Abdu'l-Bahá had adopted him into His family.

On Saturday 26 November, 'Abdu'l-Bahá caught a fever which disappeared the next day, Sunday 27 November. The last visitor of the day was the head of the police, an Englishman, and 'Abdu'l-Bahá offered him a silk hand-woken handkerchiefs, then retired to bed at around 8:30 PM. 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s very last concern, five hours before His passing was for the friends: He asked about the health of every member of the Holy Family, all the pilgrims and the Bahá’í friends in Haifa, and when he was informed they were all in good health, the Master said:

Very good, very good.

Two of His daughters, Rúḥá and Munavvar Khánum, stayed with Him as 'Abdu'l-Bahá fell asleep very calmly, free of fever.

The bedroom of 'Abdu'l-Bahá in His house at 7 Haparsim in Haifa, where He passed away. Source: Baha'i Points of Interest.

'Abdu'l-Bahá awoke at 1.15 AM on Monday 28 November 1921, rose from his bed, walked across His room to a table and drank some water. He was too warm and removed an out layer of clothing, and returned to bed, then asked His daughter, Rúḥá Khánum to lift up the mosquito net, telling her:

I have difficulty in breathing, give me more air.

'Abdu'l-Bahá drank a little, and when his daughters offered Him food, He responded in a clear voice, and giving them a beautiful look:

You wish me to take some food, and I am going?

Less than a minute later, 'Abdu'l-Bahá had passed away peacefully. His face was so beautiful, so calm and serene that, for a moment, His daughters thought He had just simply fallen asleep.

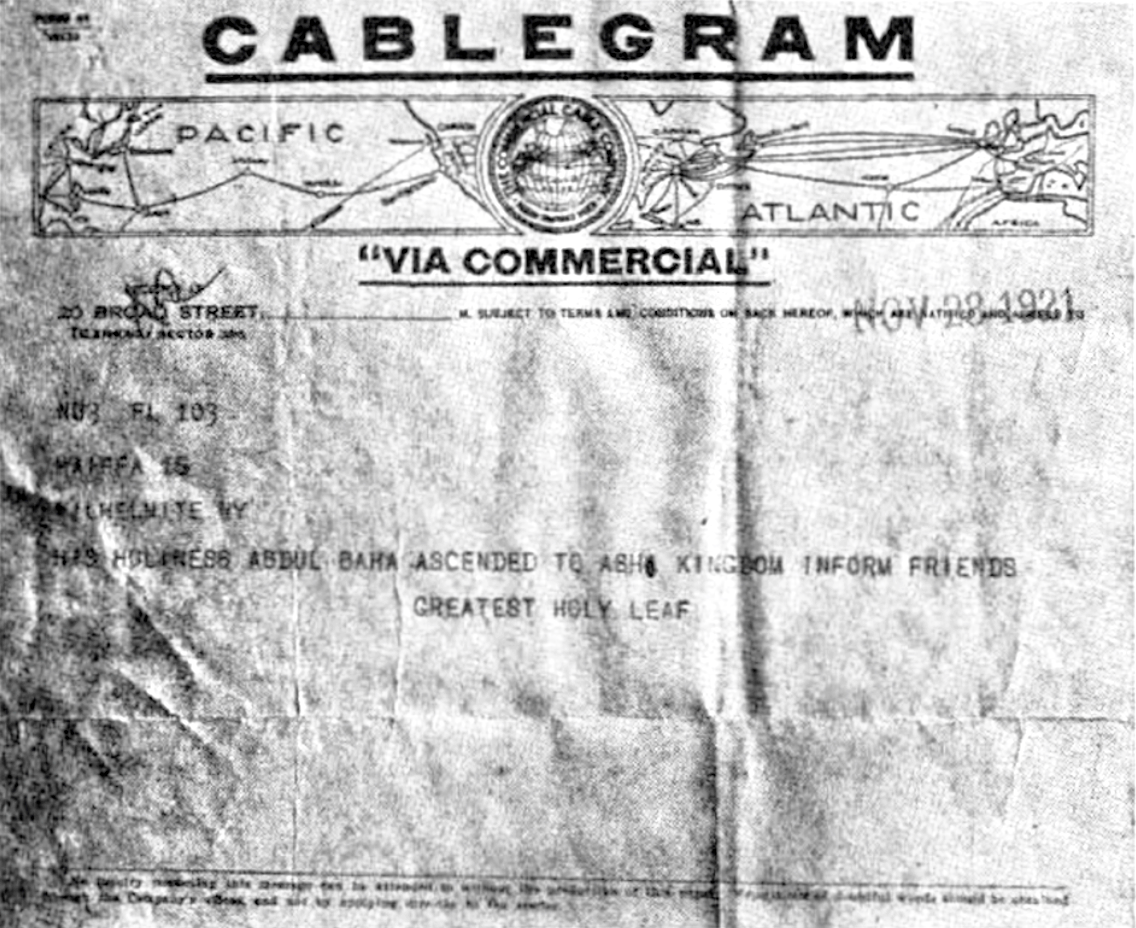

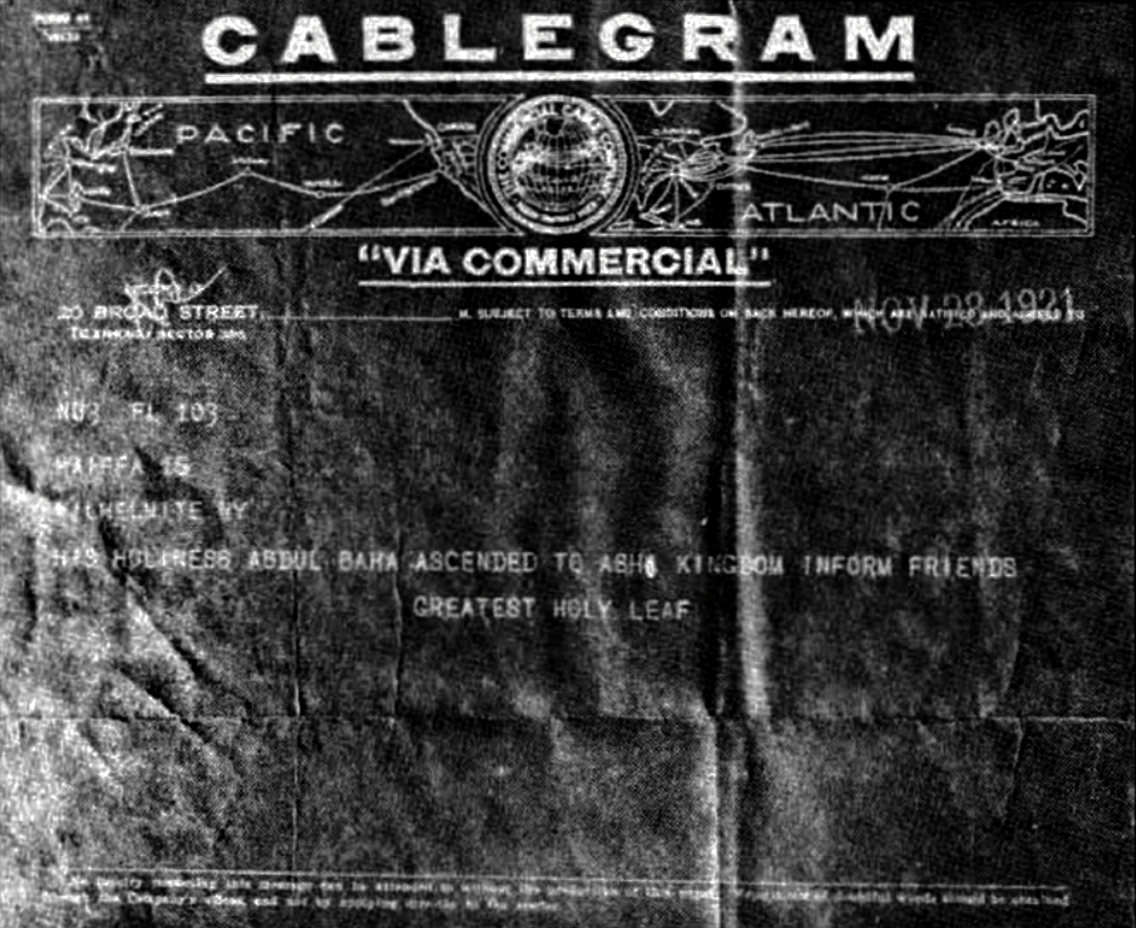

The cablegram sent by the Greatest Holy Leaf to the Bahá'ís of the world on 28 November 1921, reproduced in facsimile in Star of the West’s Special Ascension Edition, Volume 12, Number 15.

Everything now rested on the Greatest Holy Leaf’s shoulders. She was Head of the Faith until Shoghi Effendi arrived, and she had to make all the decisions. She had to, keep the Bahá'í Faith safe until the arrival of Shoghi Effendi, and make all the decisions for the funeral, burial, burial place.

But first thing she had to do was to announce 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s Ascension to the entire Bahá'í World.

The cable every Bahá'í community in the West received from Bahíyyih Khánum, the Greatest Holy Leaf on 29 December 1921 read simply:

His Holiness Abdul-Baha ascended to Abhá Kingdom.

This was the cable Shoghi Effendi saw in Major Tudor Pole’s office which caused him to faint. He had learned of his own Grandfather’s passing after most Bahá'ís, and in the exact same unceremonious manner.

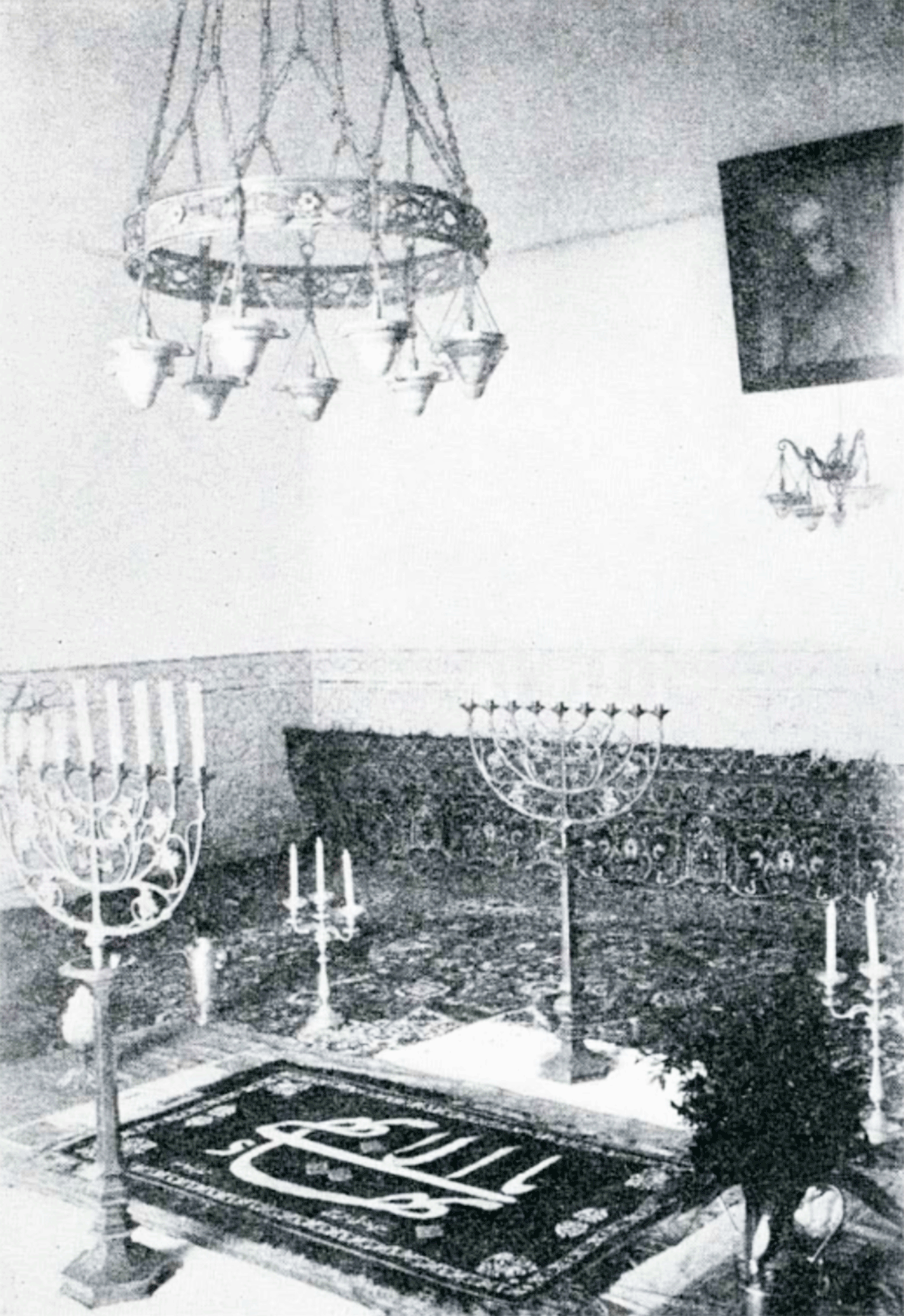

The interior of the Shrine of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá on Mount Carmel. Source: The Bahá’í World. Vol 3, page 22.

When the Greatest Holy Leaf was looking for the most befitting place to inter 'Abdu'l-Bahá, ‘Abbás-Qulí, the custodian of the Shrine of the Báb approached her and told her a 12-year-old story, dating back to 21 March 1909, when he had been alone with 'Abdu'l-Bahá after the Master had finally interred the remains of the Báb in the vault beneath the Shrine.

After 'Abdu'l-Bahá had accomplishes His historic task, He stepped from the vault into a passageway, ordered the door to the vault with the sarcophagus containing the remains of the Báb to be closed, and told ‘Abbás-Qulí, pointing to the passageway leading to an empty vault immediately next to Báb’s:

And this should be a place for Us.

The Greatest Holy Leaf had found the place to inter her beloved saintly Brother. She told ‘Abbás-Qulí before blessing him for his help:

Very well. This is where it will be.

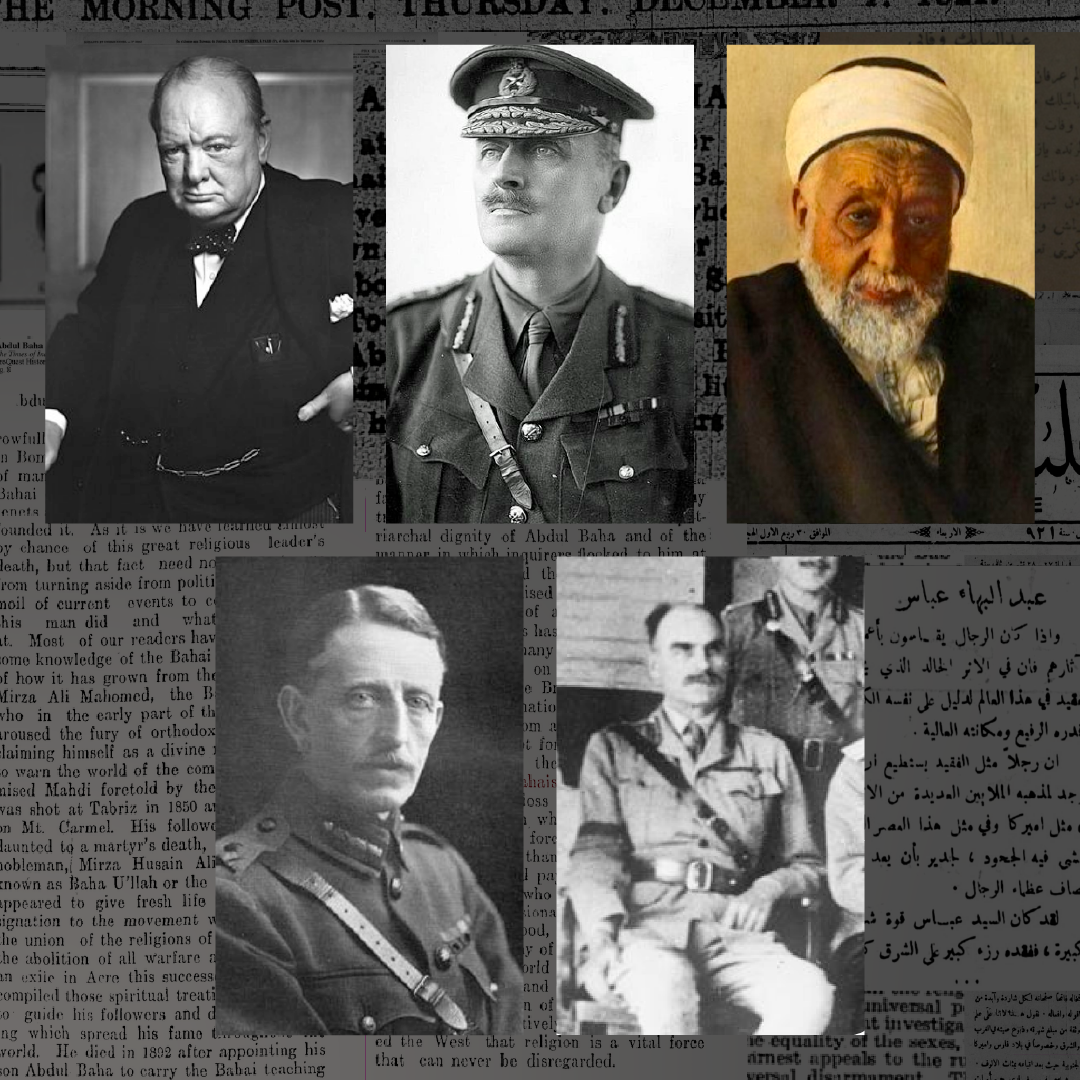

Photomontage of eminent personalities who sent condolence messages for the passing of 'Abdu'l-Bahá. Top row, left to right: Sir Winston Churchill ( Wikimedia Commons), Viscount Edmund Allenby (Wikimedia Commons), and Abd Al-Rahman Al Gailani (Wikimedia Commons). Bottom row: General Sir Walter Norris Congreve (Royal Green Jackets Museum) and Sir Arthur Money (The Imperial War Museums).

Hundreds of condolence messages poured in from the entire world, not just the Bahá'í community.

Sir Winston Churchill, the British Secretary of State for the Colonies immediately telegraphed Sir Herbert Samuel, the High Commissioner for Palestine, Sir Herbert Samuel, and instructed him to “convey to the Bahá’í Community, on behalf of His Majesty’s Government, their sympathy and condolence.”

Viscount Allenby, the High Commissioner for Egypt also wired Sir Herbert Samuel asking him to “convey to the relatives of the late Sir ‘Abdu’l‑Bahá ‘Abbás Effendi and to the Bahá’í Community...sincere sympathy in the loss of their revered leader.”

Others who expressed condolences were General Sir Walter Norris Congreve, the Commander-in-Chief of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force, and General Sir Arthur Money, former Chief Administrator of Palestine.

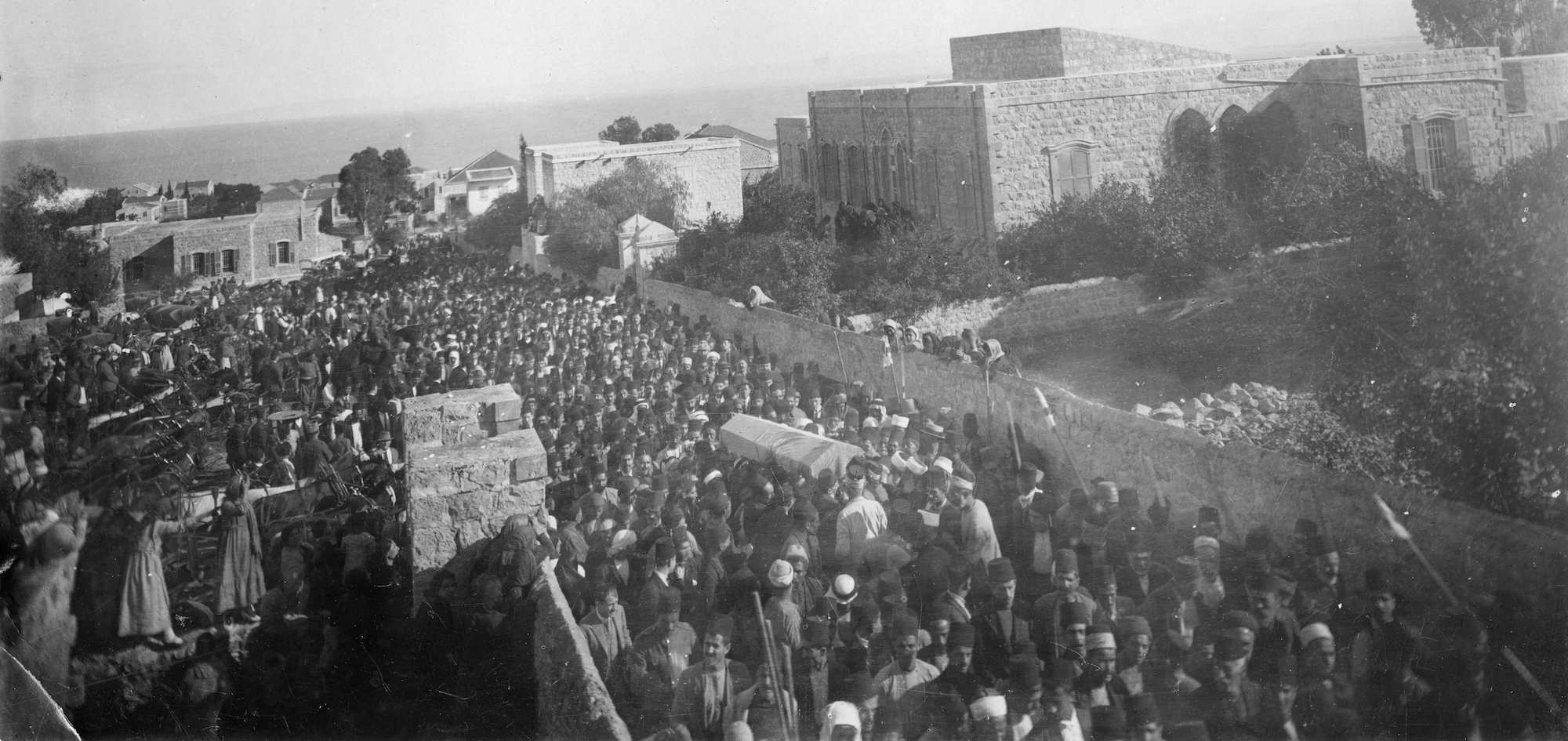

The funeral cortege of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, His casket carried aloft by pallbearers. Souce: © United States National Bahá'í Archives, used with permission.

The British Commissioner for Palestine and the Mufti of Haifa, along with other notables arrived for the funeral procession.

By 7 in the morning, on Tuesday 29 November 1921, Haifa was at a virtual standstill. The news of 'Abdu'l-Bahá's passing has shocked the city and its people, and soldiers lined both sides of Haparsim Street, some even stationed in the courtyard of the Master's house, standing guard.

'Abdu'l-Bahá's body is placed in a plain, white wood casket and the coffin was covered in a simple paisley shawl. At 9 AM, the funeral cortège left. Haparsim, and wound its way through Haifa streets until it arrived at the Shrine of the Báb, a distance of 1.5 kilometers, with Boy Scouts keeping the crowd of 10,000 people in an orderly procession.

Sir Ronald Storrs, Governor of Jerusalem was deeply moved by the funeral and said:

I have never known a more united expression of regret and respect than was called forth by the utter simplicity of the ceremony.

The failure of ‘Abdu'l-Bahá's family to instantly obey the Master's request and cable Shoghi Effendi to return home weeks before His passing had a catastrophic effect on 24-year old Shoghi Effendi, for whom 'Abdu'l-Bahá was the sun around which he revolved. Words will always fail human understanding to describe the love that Shoghi Effendi felt for 'Abdu'l-Bahá.

In the 1920s, the address of Major Wellesley Tudor Pole, in London, was often used as the distributing point for cables and letters from 'Abdu'l-Bahá and the Holy Land to the British Bahá'ís, and Shoghi Effendi, whenever he traveled to London from Oxford, always called in on Major Tudor Pole. On 29 November 1921 at 9:30 in the morning, Major Tudor Pole received the following heartbreaking cable:

His Holiness 'Abdu'l-Bahá ascended Abhá Kingdom. Inform friends. Greatest Holy Leaf.

Major Tudor Pole immediately notified the British friends by cable, by phone and by letter, and he must have called Shoghi Effendi and asked him to come to his office, in order to break the news to him as gently as humanly possible and in person.

Shoghi Effendi was not one who could be informed of this devastating blow by cable, phone or letter. It would have been too much of a shock. By noon, Shoghi Effendi had already arrived in London and entered Major Tudor Pole’s office at 61 St James' Street. He was shown into the Major’s office, where Tudor Pole was absent, and this is when Shoghi Effendi received the biggest blow of his entire life.

He was standing at Major Tudor Pole’s desk and his eye fell on the word “'Abdu'l-Bahá” in an open cablegram that was lying on the Major’s desk.

Shoghi Effendi read the cable and discovered the devastating news alone, not like the grandson of the Master, but like every other Bahá'í in the world. He read it in a cable.

Major Tudor Pole entered his office just a moment later and to his horror, he found that Shoghi Effendi had collapsed, dazed and bewildered by this catastrophic news.

In a state of shock, Shoghi Effendi was taken to the home of a Miss Grand, one of the Bahá'ís in London and he was put to bed in her home for a few days, as he began the long process of recovering from the greatest tragedy of his life.

Shoghi Effendi’s sister Rúhangiz, Lady Blomfield and several other British Bahá'ís, did everything they could to try and comfort him, but he was utterly grief-stricken.

For several days, Shoghi Effendi was unable to move.

Letter from Esslemont: “bolt out of the blue…how heart-broken you must feel…” Background photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash.

The friendship between Dr. Esslemont and Shoghi Effendi was a deep one. As soon as Dr. Esslemont heard of 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s passing, his first thought was for his young friend and he wrote him a deeply sensitive and moving letter:

Dearest Shoghi,

It was indeed a "bolt from the blue" when I got Tudor Pole's wire this morning: "Master passed on peacefully Haifa yesterday morning"...

It must be very hard for you, away from your family and even away from all Bahá'í friends.

What will you do now? I suppose you will go back to Haifa as soon as possible.

Meantime you are most welcome to come here for a few days...Just send me a wire...and I shall have a room ready for you...if I can be of any help to you in any way I shall be so glad.

I can well imagine how heart-broken you must feel and how you must long to be at home and what a terrible blank you must feel in your life...Christ was closer to His loved ones after His ascension than before, and so I pray it may be with the beloved and ourselves.

We must do our part to shoulder the responsibility of the Cause and His Spirit and Power will be with us and in us.

Shoghi Effendi accepted Dr. Esslemont’s invitation and he spent a few days with his close friend in Bournemouth before beginning preparations to return to Haifa.

“almost senseless, absent-minded and greatly agitated.” Background photo by Salman Khan on Unsplash.

When Dr. Luṭfu’lláh Ḥakím visited Shoghi Effendi, two days after the Ascension of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, he found him in bed, absolutely overcome with grief.

Shoghi Effendi was utterly overwhelmed with loss, unable to eat, or sleep. He was, in his own words, overwhelmed in body and mind by the terrible news, and laid in bed for a couple of days, “almost senseless, absent-minded and greatly agitated.”

During Dr. Luṭfu’lláh Ḥakím ’s visit, Shoghi Effendi recovered slightly, enough to translate and chant the last Tablet he had received from his Grandfather for his host, Miss Grand, Dr. Luṭfu’lláh Ḥakím , Lady Blomfield and two other Bahá'ís.

Together the friends made plans for Shoghi Effendi’s travel to Haifa with Lady Blomfield and his sister Rúhangiz.

Dr. Luṭfu’lláh Ḥakím accompanied him that afternoon to Bournemouth, an important change of scenery from London, where Shoghi Effendi had received the life-altering shock, and where he would rest and recuperate while preparations were underway for his journey to the Holy Land.

Shoghi Effendi would stay with Dr. Esslemont between December 2 and 7 until he received a cable from his great-aunt, the Greatest Holy Leaf, asking him to return to Haifa.

“Gradually His power revived me and breathed in me a confidence that I hope will henceforth guide me and inspire me in my humble work of service... I am immediately starting for Haifa to receive the instructions He has left and have now made a supreme determination to dedicate my life to His service and by His aid to carry out His instructions all the days of my life.” Background Photo by Sebastian Molina fotografía on Unsplash.

In an undated letter he wrote between 2 and 7 December 1921 in Bournemouth, Shoghi Effendi writes astonishing words about the passing of 'Abdu'l-Bahá and its implications for the ushering in of a new era for the Bahá'í Faith, as well as his enduring connection with 'Abdu'l-Bahá beyond this plane and into the Abhá Kingdom:

Gradually His power revived me and breathed in me a confidence that I hope will henceforth guide me and inspire me in my humble work of service.

The day had to come, but how sudden and unexpected.

The fact however that His Cause has created so many and such beautiful souls all over the world is a sure guarantee that it will live and prosper and ere long will compass the world! I am immediately starting for Haifa to receive the instructions He has left and have now made a supreme determination to dedicate my life to His service and by His aid to carry out His instructions all the days of my life.

…The stir which is now aroused in the Bahá'í world is an impetus to this Cause and will awaken every faithful soul to shoulder the responsibilities which the Master has now placed upon every one of us.

The Holy Land will remain the focal centre of the Bahá'í world; a new era will now come upon it. The Master in His great vision has consolidated His work and His spirit assures me that its results will soon be made manifest.

“Your noble letter uplifted us all and renewed our strength and determination; for if you could gather yourself together and rise above such grievous sorrow and shock, and comfort us, we, too, must do no less...” Background photo from Taylor Lastovich on Pexels.

In the midst of this emotional devastation, while he was recuperating in Bournemouth with Dr. Esslemont, the tender-hearted Shoghi Effendi still found time to offer love and comfort to other grieving souls, just as his Grandfather would have done.

Reeling with crushing grief and insurmountable spiritual anguish, Shoghi Effendi still found meaningful ways to comfort his Manchester friends who were devastated by the loss of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, something evident in this letter which his dear friend Edward Hall wrote to him on 5 December 1921, barely a week after the Ascension of 'Abdu'l-Bahá. Shoghi Effendi had managed to soothe the hearts of his friends, while his would remain broken forever, and his love to them gave them courage and strength:

Your loving, tender and noble letter, full of encouragement and fortitude came when we were very sad but resolute, very shocked but thoroughly understanding; and it turned the tide of our feelings into a flood-tide of peace and patience in the Will of God…Your noble letter uplifted us all and renewed our strength and determination; for if you could gather yourself together and rise above such grievous sorrow and shock, and comfort us, we, too, must do no less; but arise and serve the Cause which is our Mother.

In closing his letter, Edward Hall gives profound expression to his love, and the Manchester Bahá'í community’s love for Shoghi Effendi, offering him their love as he set out on his last journey before he became Guardian of the Cause—at this point, no one knew what was in store for the Faith’s next, glorious chapter:

I know you have a thousand things to see to ere you start for the Holy Land, But we all love you dearly and we are all united and stronger than ever. Go with our love and sympathy and all our hearts to that Hallowed Spot, for we are one with you always.

London in 1921. Unknown photographer. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Shoghi Effendi was deeply sad and overcome with grief, but pressed on courageously, returning to London on 8 December 1921, after spending five days with his close friend, Dr. Esslemont in Bournemouth, to try and book an earlier passage to the Holy Land. He had just received a telegram from the Greatest Holy Leaf dated 7 December 1921, urging him to travel as soon as he could and he was looking for the fastest way to get to Haifa.

At a meeting of the friends in Miss Grant’s apartment on 8 December 1921, where they were bidding farewell to Shoghi Effendi, still wearing his overcoat, although the room was heated. The friends asked him if he would not like to remove it, but Shoghi Effendi replied that when he had left the Holy Land for England, his Grandfather and told him to always wear it in winter.

Unfortunately, Shoghi Effendi was not able to leave England when he had planned.

There were issues with his passport that took some time to resolve, and he was only able to leave 8 days later, on 16 December 1921.

A 1921 passenger liner, the RMS Berengaria, a ship of the Cunard line. This ship was a transatlantic steamer, and much larger than the ship that brought Shoghi Effendi to Egypt from England, but it was so beautiful that this author could not resist using the image. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Shoghi Effendi’s departure from England was delayed because of passport complications.

On 16 December 1921, 18 days after the Ascension of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, Shoghi Effendi finally set sail for the Holy Land accompanied by Lady Blomfield and his sister Rúhangiz.

Their boat docked in Egypt.

East Haifa train station in 1931. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Shoghi Effendi arrived in Haifa by train from Egypt at 5.20 P.M. on 29 December 1921, exactly one month after the Ascension of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, where he was welcomed by many Bahá'í friends. The agony of bereavement had taken its toll on Shoghi Effendi and he was broken by grief, so frail that he had to be helped up the stairs of the Master's house upon his arrival.

Louise Bosch was in the tea room of the Master’s House alone, at the time everyone—the Holy Family and the Bahá'ís— was expecting Shoghi Effendi to arrive at any minute. Suddenly, Louise heard footsteps. It was Shoghi Effendi coming in, and as he entered, he gave out a loud, indescribable cry of the greatest grief, the greatest pain, the greatest ache.

Inside 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s home, was the only person in the world who could in any way comfort Shoghi Effendi: his beloved great-aunt, the sister of 'Abdu'l-Bahá. Bahíyyih Khánum, the Greatest Holy Leaf, so slight in appearance and so modest in character, had been the rock of the whole family in the month since 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s passing.

Shoghi Effendi was so devastated by ‘Abdu'l-Bahá's absence from His home that he was confined to bed for several days.

Upon arriving in Haifa, Shoghi Effendi first stayed in his old room, right next to 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s, now empty bedroom, but he was soon moved to a room in the house of one of his aunts while the Greatest Holy Leaf had two rooms and a bath built for him on the roof of the Master’s home.

For the first three days of his arrival in Haifa, 29, 30, and 31 December, the Greatest Holy Leaf did not show Shoghi Effendi the Will and Testament, but she could wait no longer.

Shoghi Effendi had to know.

The Faith needed its Guardian.

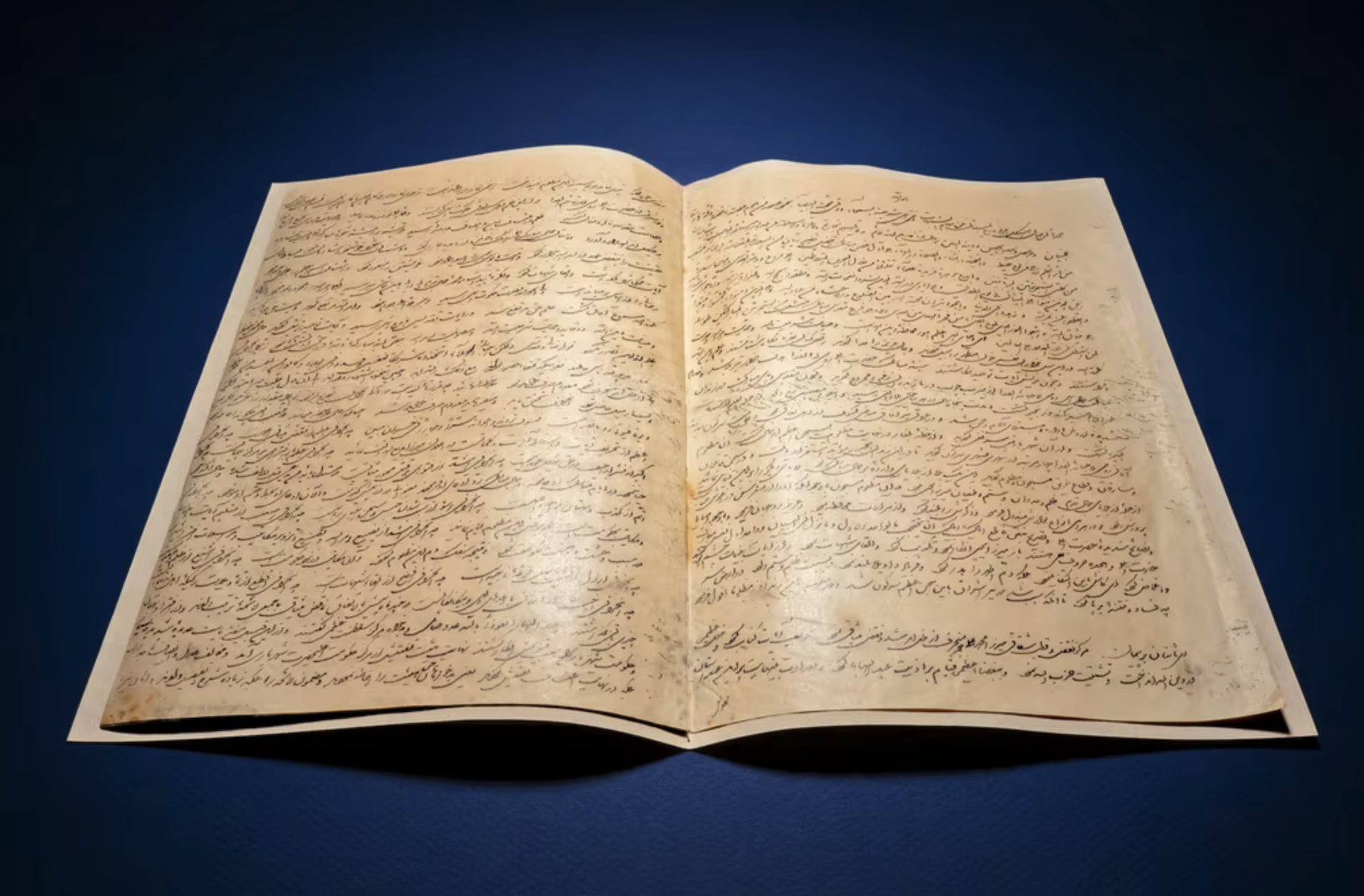

Photo of opening pages of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s Will and Testament. Source: Bahá'í World News Service, 24 December 2021.

Although Shoghi Effendi had been informed that 'Abdu'l-Bahá had left a letter for him, he had absolutely no knowledge of the contents of the document. At the most, Shoghi Effendi expected, due to his rank as the Master’s eldest grandson, that 'Abdu'l-Bahá might have left instructions regarding the election of the Universal House of Justice, and maybe even that he was the one who would be designated as the Convenor of the conference to elect the Supreme. Governing body of the Bahá'í Faith.

Shoghi Effendi had no foreknowledge of the institution of the Guardianship, he had no idea that his Grandfather had chosen him as Guardian when he was only 4 and 12 years old, and all these discoveries at once came as a shock to Shoghi Effendi, still so young at the age of 24, and naturally sensitive. It was all a tremendous, life-altering shock.

Knowledge of his new station instantly changed Shoghi Effendi. He knew, better than anyone else, exactly what being the Guardian entailed, that same burden of holding and protecting the Covenant, safeguarding and propagating the Faith, which had rested on the shoulders of the three Central Figures of the Faith before him.

In perhaps one of the most poignant sentences of "The Priceless Pearl," Rúḥíyyih Khánum recalls Shoghi Effendi telling her:

When they read the Master's Will to me, I ceased to be a normal human being.

Shoghi Effendi was now the Guardian of the Bahá'í Faith, and ‘Abdu'l-Bahá's Will and Testament now had to be read publicly.

Shoghi Effendi is now and forevermore the Guardian. Source: Blessings Beyond Measure, ‘Alí Yazdí, page 92.

Louise Bosch, an American pilgrim saw Shoghi Effendi after he had been read the Will and Testament, and recalled that he objected so strenuously his own mother, Ḍíyá‘íyyih Khánum, recalled to him how, in the days after Muḥammad’s Ascension, one of the Imáms refused to take over the mantle of leadership, too, and she asked her son:

Are you going to repeat the history of that Imám, who also felt that he was not qualified?

At the house of the Master. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

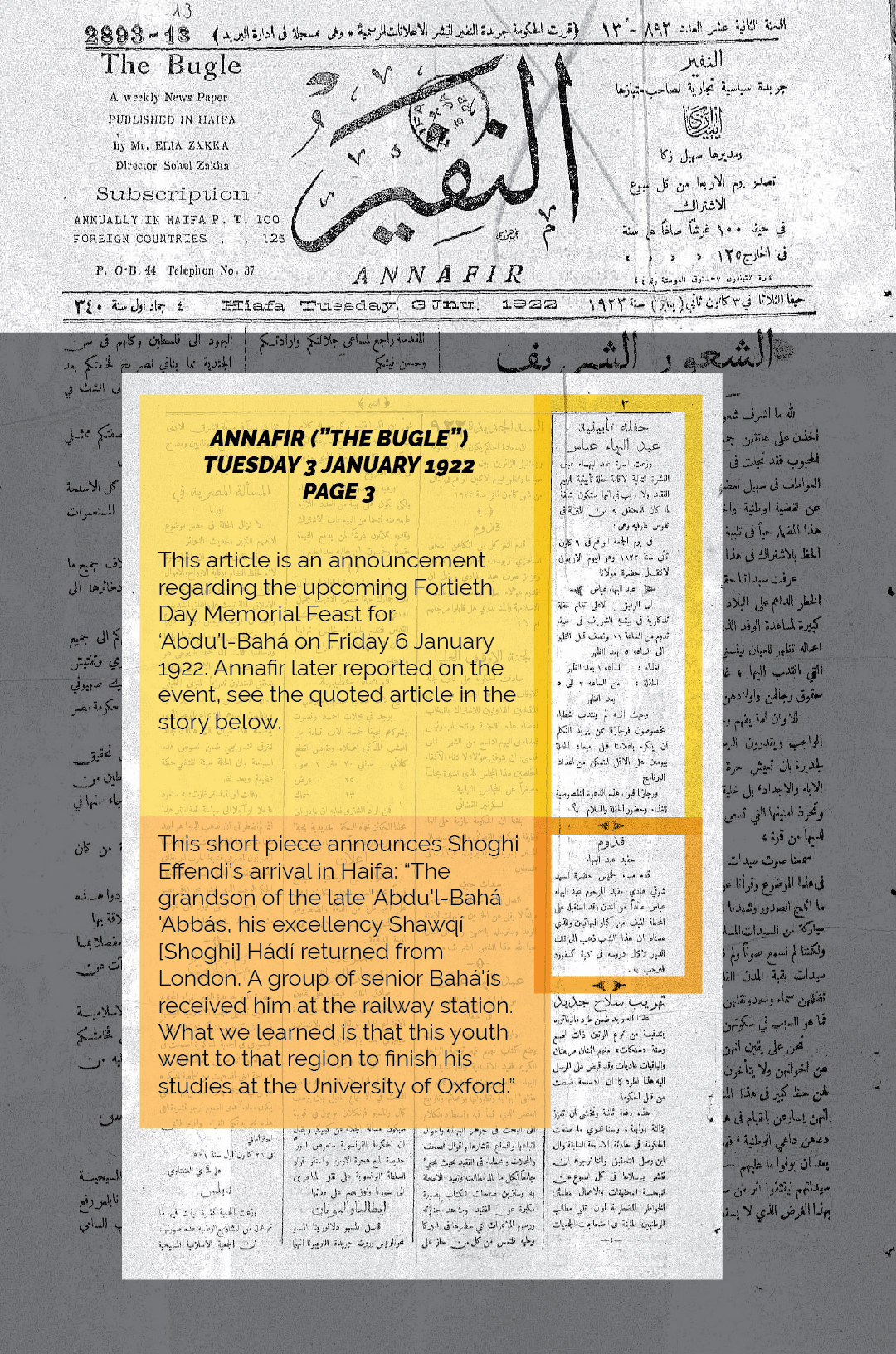

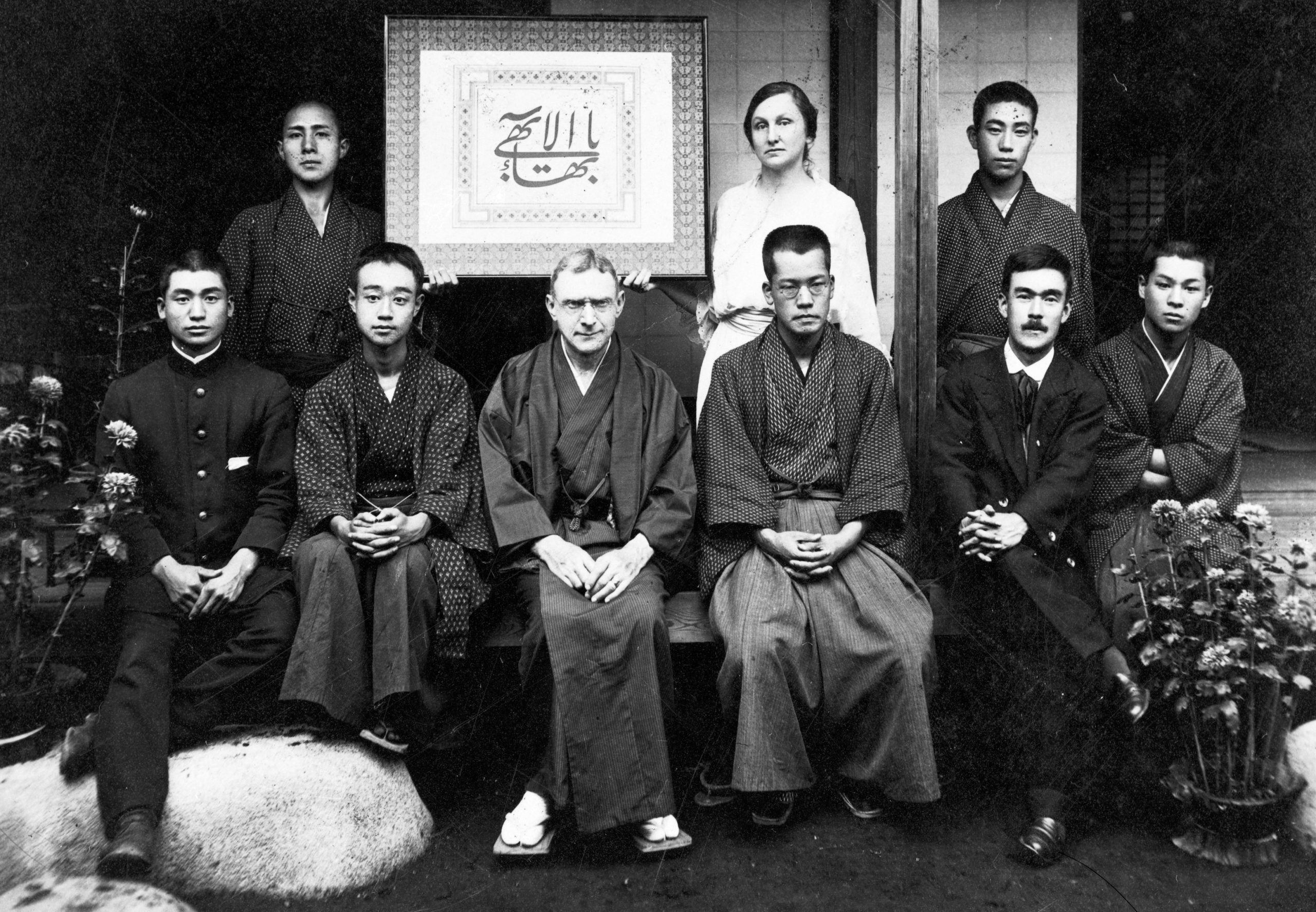

On the morning of January 3, 1922, Shoghi Effendi visited the Shrine of the Báb and the Tomb of 'Abdu'l-Bahá. Later the same day, at the House of the Master, ‘Abdu'l-Bahá's Will and Testament was read aloud to nine men, most of whom were members of the family of ‘Abdu'l-Bahá. Bahá'ís from Persia, India, Egypt, England, Italy, Germany, America and Japan were present at this reading.

Shoghi Effendi was not present, and according to Amatu’l-Bahá Rúḥíyyih Khánum, this was both for reasons of ill health as much as sensitivity on his part.

These men witnessed ‘Abdu'l-Bahá's own handwriting, His seals, and His signatures throughout the three documents that composed His Will and Testament. At Shoghi Effendi's request, a true copy of ‘Abdu'l-Bahá's Will and Testament was made by one of the men present, a Persian Bahá'í.

Click on the link below to listen to excerpts from the Will and Testament of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, recited in Arabic and Persian with English subtitles:

“It is all right.” Background photo by yousef alfuhigi on Unsplash.

After the first reading of the Will and Testament on 3 January 1921, Louise Bosch went over to the House of 'Abdu'l-Bahá after sunset and never forgot what she witnessed. Shoghi Effendi was coming out of a room, and entered the room of the Greatest Holy Leaf.

Shoghi Effendi, who had been under so much stress and pressure—looked like had aged, and become an old man. He was walking bent over and could hardly speak, but he shook Louise’s hand, and looked at her for a moment. He spoke like someone who did not want to hear anything and did not want to see anyone. He was a completely different person.

Shoghi Effendi was carrying a little light or a candle in his hand, and said to Louise:

It is all right.

But Louise knew something terrible had happened. Shoghi Effendi had reacted exactly the way his family thought he would, and he became ill, he stopped eating, and could not drink or sleep.

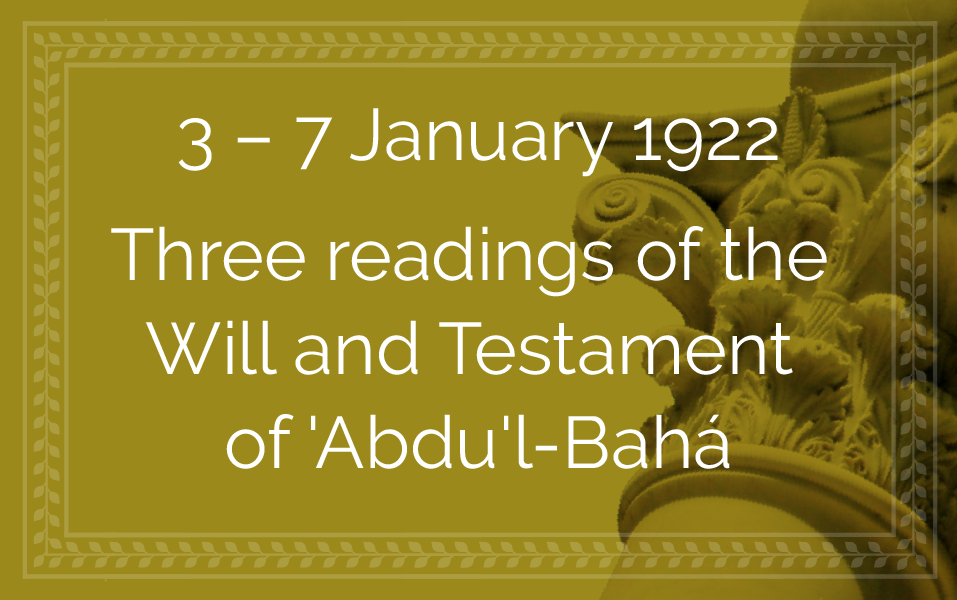

Tuesday 3 January 1922 Annafir ("The Bugle") article regarding the upcoming Friday 6 January 1922 Fortieth Day Memorial Feast for 'Abdu'l-Bahá. The article and the information contained in this graphic are both courtesy of Dr. Necati Alkan, an independent scholar with expertise about late Ottoman history and special focus on the Baha'i Faith. Annafir published an article about the Memorial Feast after it had taken place, and this article is quoted in the story below.

In accordance with eastern tradition, an impressive memorial feast is held in ‘Abdu'l-Bahá's memory on the fortieth day after His passing, on Friday 6 January 1922 at 1 PM.

Six hundred and fifty people from Haifa, 'Akká, neighboring towns, and as far away as Syria, Lebanon and Egypt, headed by Lieutenant Colonel Stewart Symes, the Governor of Phoenicia, the Governor of Haifa, government officials, foreign consuls, prominent poets and scholars, Muslims, Christians, Jews and Bahá'ís of various nationalities, gather at the home of ‘Abdu'l-Bahá at 7, Persian street (now Haparsim).

The members of the Master's household have arranged a perfectly prepared dinner for the more than 600 guests at the banquet, but also 150 of the poor of Haifa, gathered in a special banquet of their own.

The long banquet tables are decorated with trailing branches of bougainvillea, the vibrant purple blooms, mingling with white narcissus and large dishes filled with golden oranges from the Master's own garden.

Each and every guest receives the very same, warm welcome into the Master's house.

An article was published in the Arabic-language Haifa newspaper Annafir ("The Bugle"), a Haifa newspaper enthusiastically reporting the magnificent Fortieth Day Memorial Feast for 'Abdu'l-Bahá:

At one o'clock in the afternoon people from Haifa, 'Akká and the neighboring towns, headed by the High Commissioner of Palestine, government officials, foreign consuls, religious leaders, prominent poets and scholars of all nations, races, and creeds, assembled at the house of the late 'Abdu'l- Baha 'Abbás. Neither in Haifa nor in any other Oriental city has there ever been such an impressive service. A well-arranged and perfectly prepared dinner was served to more than six hundred guests. Besides these, one hundred and fifty of the poor gathered in a special place prepared for them. After all had partaken of the delicious food, they assembled in the large hall. On the platform was a photograph of the departed.

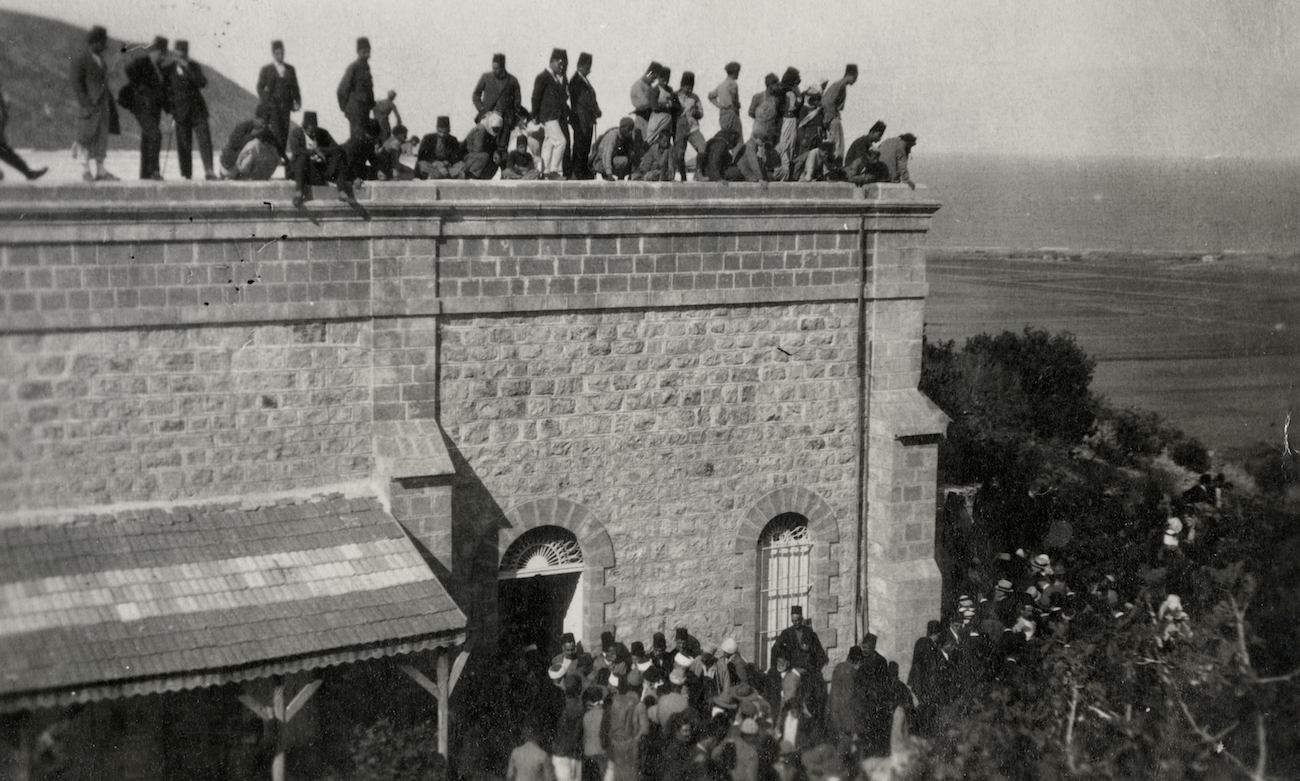

Men and boys crowd the roof of the Shrine of the Báb to hear the memorial speeches on Tuesday 29 November, the day of 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s funeral. Source: © United States National Bahá'í Archives, used with permission.

After the luncheon, the guests entered the large central hall of the Master's house, where both end rooms had been thrown open to accommodate the large number of guests.

Chairs had been brought in to ensure everyone could be seated, and the main hall had been decorated with beautiful rugs and draperies.

There was also a portrait of ‘Abdu'l-Bahá, and a raised platform had been brought in for the speakers, none of whom were Bahá'í and who included, among others, the Secretary of the National Muslim Society, Lieutenant Colonel Stewart Symes, Governor of Phoenicia, a young Christian poet, a well-known Muslim orator.

The six speeches were published in Annafir ("The Bugle"), a Haifa newspaper, and you can read them in full by downloading the magnificent compilation created by David Merrick, titled Passing of ‘Abdu'l-Bahá.

The front gate of the House of the Master, inside of which, in the main central hall, the Will and Testament of 'Abdu'l-Bahá is read for a second time. Source: Bahaimedia.

The Will and Testament of ‘Abdu'l-Bahá was read a second time publicly, after the speeches and tributes in honor of ‘Abdu'l-Bahá at the fortieth-day Memorial Feast. The guests of the memorial feast were eager to hear from Shoghi Effendi himself, and one of the Bahá'í friends carries a message to the Guardian to this effect. Shoghi Effendi was with the Greatest Holy Leaf, in her room, and when he receives the message, says he is too distressed and overcome to address the guests and instead, penned a message to be read on his behalf, which began with the following words:

The shock has been too sudden and grievous for my youthful age to enable me to be present at this gathering of the loved ones of beloved 'Abdu'l-Bahá.

Shoghi Effendi then expressed the heartfelt gratitude of himself and ‘Abdu'l-Bahá's family's for the presence of the Governor and the speakers who, by their sincere words "have revived his sacred memory in our hearts... I venture to hope that we his kindred and his family may by our deeds and words, prove worthy of the glorious example he has set before us and thereby earn your esteem and your affection. May His everlasting spirit be with us all and knit us together for evermore!"

The House of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, seen from the garden at the back. Source: Bahaimedia.

On January 7, 1922 in the Master's house the day after the Memorial Feast, ‘Abdu'l-Bahá's Will and Testament was read once again, in its entirety, but this time, to an audience composed entirely of Bahá'ís, the intended recipients of the weighty injunctions and provisions.

It was read in the large, central hall of the House of 'Abdu'l-Bahá at 7, Haparsim, the house in which He had passed away. The crowd—composed of Bahá'ís from Persia, India, Egypt, England, Italy, Germany, America and Japan. was so large that many people sat on the floor. Women were present, but seated behind a curtain, according to Persian tradition at the time in the 1920s.

In the corner of the hall, a prominent Egyptian Bahá'í read the Will and Testament out loud. Each time Shoghi Effendi’s name was mentioned, everyone would rise.

Shoghi Effendi was not present during this reading, as was his custom, but everyone in the audience rose each time his name was mentioned in the Will, as a show of respect.

To those assembled, it was abundantly clear that the responsibility of leading the Faith and its affairs have now fallen on the shoulders of Shoghi Effendi, Guardian of the Bahá'í Faith.

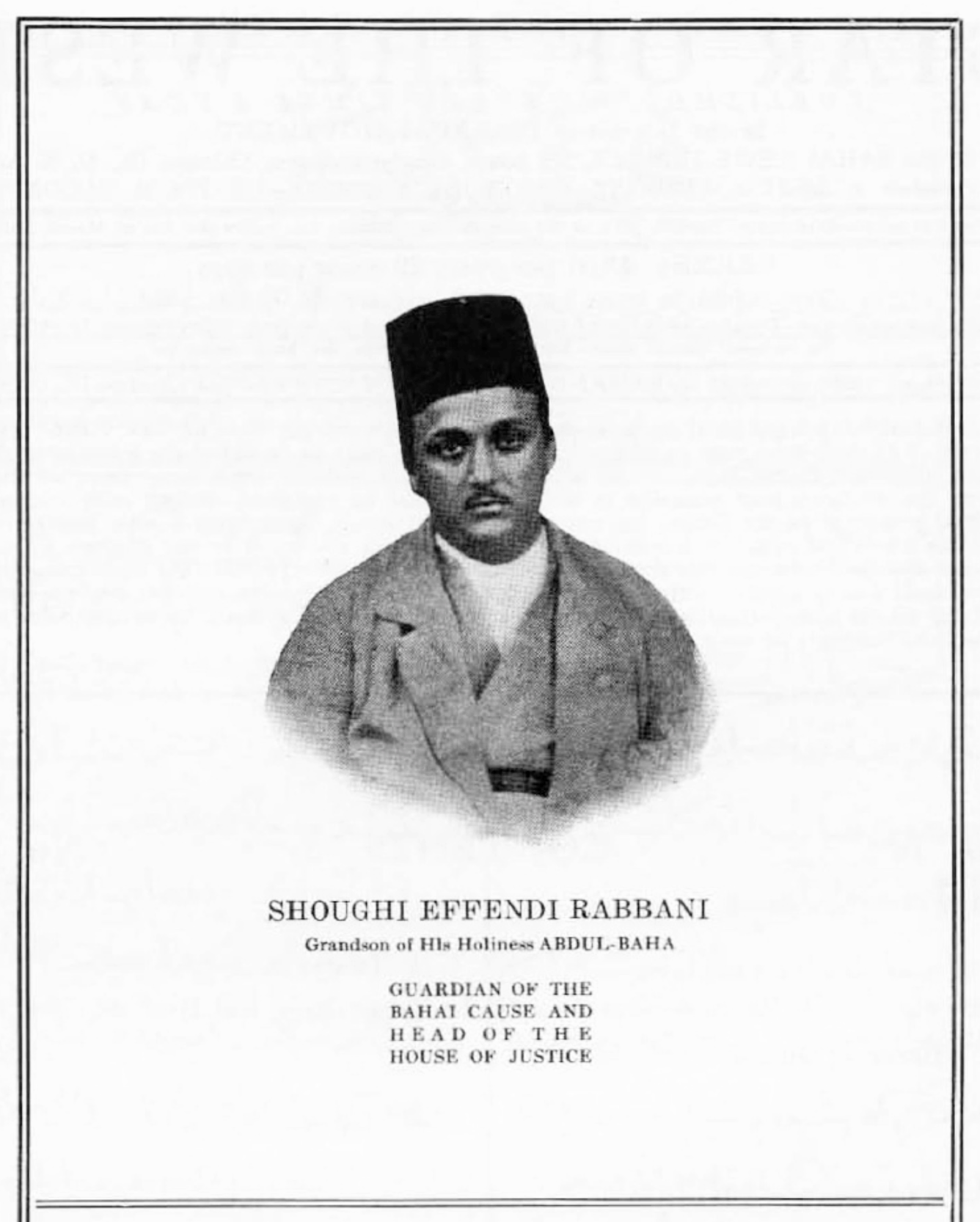

Guardian. Full-page photograph and announcement in Star of the West Volume 12 Number 17 page 258 introducing the Bahá'ís of the world to the new Head of the Bahá'í Faith: Shoghi Effendi, grandson of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, Guardian of the Cause and Head of the Universal House of Justice.

Befittingly, it was Bahíyyih Khánum, the Greatest Holy Leaf, and not Shoghi Effendi, who announced to the Bahá'í world the provisions of the ‘Abdu'l-Bahá's Will and Testament.

First, the Greatest Holy Leaf sent two cables to Persia on January 7, 1922.

The first one reads:

Memorial meetings all over the world have been held. The Lord of all the worlds in His Will and Testament has revealed His instructions. Copy will be sent. Inform believers.

and the second reads:

Will and Testament forwarded Shoghi Effendi Centre Cause.

The Spiritual Assembly of Ṭihrán had written to 'Abdu'l-Bahá asking in whose names properties in Persia should be registered to, and the Master had answered, no doubt foreseeing future events:

You have asked in whose name the real estate and buildings donated should be registered with the Government and the legal deeds issued: they should be registered in the name of Mirza Shoghi Rabbani, who is the son of Mírzá Hádí Shírází and is in London.

This Tablet from 'Abdu'l-Bahá explains in great part why it was no surprise to the Persian believers that Shoghi Effendi had been appointed Guardian of the Faith in the Master’s Will and Testament.

The Greatest Holy Leaf, sister of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, who held the Bahá'ís together after the Ascension of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, made all the crucial decisions, sent all the crucial cables, and supported Shoghi Effendi, the new Guardian of the Faith, throughout. Source: Bahá'í Talks.

Nine days after sending the first two cables to the Persian Bahá'ís, on January 16, 1922, the Greatest Holy Leaf sent the following cable to the United States:

In Will Shoghi Effendi appointed Guardian of Cause and Head of House of Justice. Inform American friends.

These series of three cables sent by Bahíyyih Khánum to the Bahá'í world are a great sign of what is to come. Despite the fact that Shoghi Effendi was, from the very beginning as the Guardian of the Faith, both tactful and masterful in the way he addressed any challenge or problem that arose, for the next ten years, he would have a constant and abiding ally, support, collaborator and loving presence in the Greatest Holy Leaf.

Bahíyyih Khánum’s station, her limpid character, her oceanic love for Shoghi Effendi made her not only his sole earthly support, but also, and more importantly, his refuge.

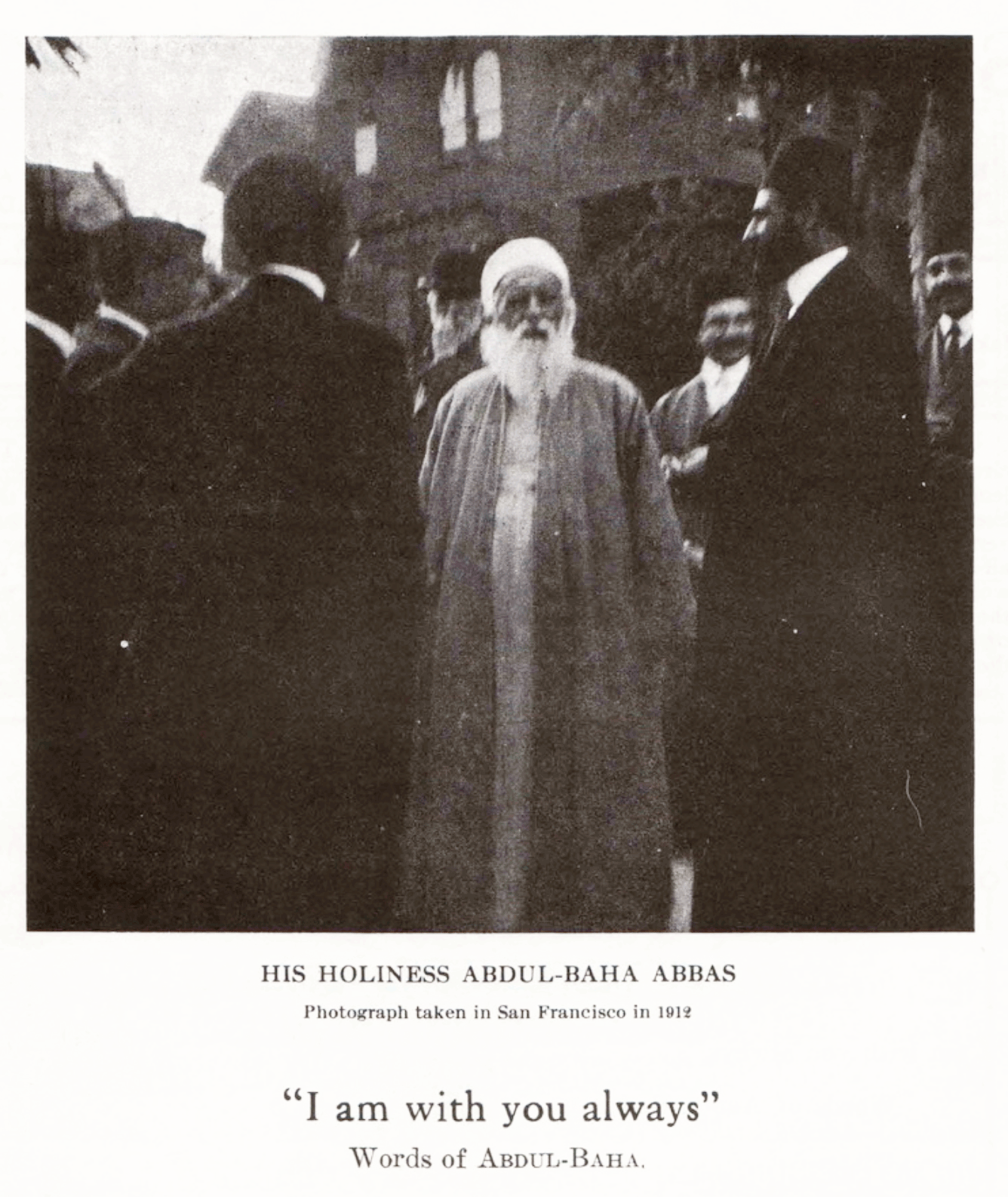

"I am with you always": A memorial photograph of 'ab in San Francisco in 1912. Source: Star of the West Volume 12, Number 16, page 250.

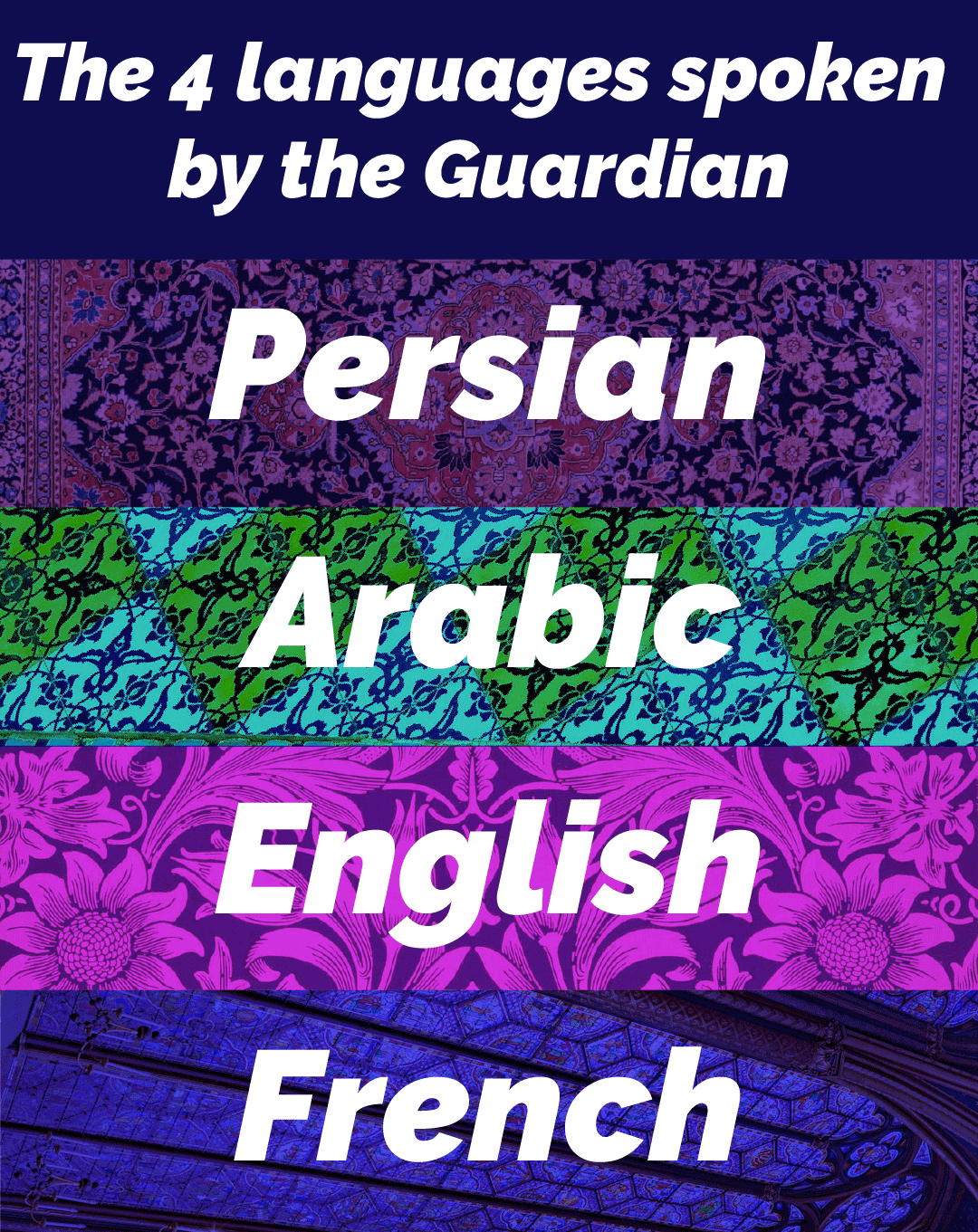

Almost immediately after having been acquainted with the contents of 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s Will and Testament, Shoghi Effendi—now the Guardian of the Cause of Bahá'u'lláh— set himself the painful task of translating it into English.

This was a daunting task, and no one has framed it better than Mr. ‘Alí Nakhjávání in his masterful series of talks, Shoghi Effendi: The Range and Power of His Pen:

Here was this 24-year-old youth, who had to translate, for all time, the provisions of a document which he later described as one of the two “Charter[s] of a future world civilization.” While he was doing this seminal work, he also had to make sure that photostatic copies of his Grandfather’s Will or reliable transcripts were made and duly sent to different Bahá’í communities throughout the East. Sentence by sentence, he had to translate the story of the sufferings endured by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, the disloyalty and rebellion of His half-brother, Mírzá Muḥammad-‘Alí, and the Master’s prediction of the frustration of all his hopes and those of the people who followed him. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá also expressed in His last wishes a call to all the friends to arise unitedly to disperse far and wide and to follow the heroic example of the Disciples of Jesus Christ. In this self-same document ‘Abdu’l-Bahá expresses His desire for martyrdom, and utters His prayers for the repentance and forgiveness of His enemies. On more practical matters, the Master outlined the responsibilities and powers devolving on the Guardian of the Faith, including his appointment of the Hands of the Cause of God, and specified the scope of the duties and functions of the Universal House of Justice, as well as stipulating the method of the election of this Supreme Body.

Evil things were rumbling across the world as Shoghi Effendi was translating 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s Will and Testament into English.

The American and Persian Covenant-breakers in the United States were counting on the Bahá'í Faith being severely weakened with the passing of 'Abdu'l-Bahá.

The Guardian made the decision to share the English translation of 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s Will and Testament in two stages.

Immediately after Bahíyyih Khánum had sent cables to the entire Bahá'í world announcing the provisions of the Will and Testament of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, Shoghi Effendi compiled 8 passages from the Master’s Will and circulated them among the Bahá'ís.

In a typical act of humility on behalf of Shoghi Effendi, only one of the 8 excerpts referred to Shoghi Effendi himself, and it was a very brief one which read:

O ye the faithful loved ones of 'Abdu'l-Bahá! It is incumbent upon you to take the greatest care of Shoghi Effendi. For he is, after 'Abdu'l-Bahá, the guardian of the Cause of God, the Afnán, the Hands (pillars) of the Cause and the beloved of the Lord must obey him and turn unto him.

The Master’s Will and Testament is filled with passages of great power and authority regarding Shoghi Effendi and his station, but Shoghi Effendi chose the least provocative to first introduce himself to the Bahá'ís.

Shoghi Effendi initially circulated these 8 selections with the Bahá'ís in the West to begin preparing them for a fuller understanding of the entire Will and Testament of 'Abdu'l-Bahá.

Soon after sending the short compilation, Shoghi Effendi sent the entire text of the Will and Testament to the Bahá'ís.

From the very beginning, Shoghi Effendi repeatedly indicated to Persian and western Bahá'ís that the provisions of the Will and Testament had hidden implications that would be revealed in time, as he explains in this letter dated 23 February 1924 to the American Bahá'ís:

To attempt to estimate its full value, and grasp its exact significance after so short a time since its inception would be premature and presumptuous on our part. We must trust to time, and the guidance of God’s Universal House of Justice, to obtain a clearer and fuller understanding of its provisions and implications....

One of these provisions would be what would happen to the Faith if the Guardian were to pass away without leaving a successor. This would be one of the greatest tests of the worldwide Bahá'í community, and thanks to 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s Will and Testament, to the 36 years of Shoghi Effendi’s Guardianship, to the wisdom and steadfastness of the Hands of the Cause, the hidden implications in the provisions of the Master’s Will and Testament would save the Bahá'í world.

While he was in the middle of translating 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s Will and Testament into English, Shoghi Effendi wrote his very first letter to the Persian Bahá'ís on 16 January, in which he encouraged them to remain steadfast and protect the Faith and sharing with them his grief at the passing of 'Abdu'l-Bahá’.

Five days later, on 21 January 1921, Shoghi Effendi wrote his first letter to the American Bahá'ís, opening with:

At this early hour when the morning light is just breaking upon the Holy Land, whilst the gloom of the dear Master's bereavement is still hanging think upon the hearts, I feel as if my should turns in yearning love and full of hope to that great company of His loved ones across the seas…

Already he had placed his hand on the tiller and sees the channels he must navigate clearly before him: "the broad and straight path of teaching", as he phrased it, unity, selflessness, detachment, prudence, caution, earnest endeavour to carry out the Master's wishes, awareness of His presence, shunning of the enemies of the Cause - these must be the goal and animation of the believers.

Four days after that letter, on 25 January 1921, Shoghi Effendi wrote his first letter to the Japanese Bahá'ís:

Despondent and sorrowful though I be in these darksome days, yet whenever I call to mind the hopes our departed Master so confidently reposed in the friends in that Far-eastern land, hope revives within me and drives away the gloom of His bereavement.

As His attendant and secretary for well-nigh two years after the termination of the Great War, I recall so vividly the radiant joy that transfigured His face whenever I opened before Him your supplications…

An Account of the Passing of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, Shoghi Effendi and Lady Sarah Louisa Blomfield, originally published in 1922 as a separate booklet, then published in the 1973 Bahá'í World on the 50th anniversary of the passing of Abdu'l-Bahá, and then posted in 2021, with minor changes, at bahai.org.

In the depths of his endless sorrow of losing his adored Grandfather, reeling with the realization that 'Abdu'l-Bahá had named him Guardian, protector and interpreter, Shoghi Effendi still found the strength to empathize with the suffering of the hundreds of thousands of Bahá'ís worldwide who were also grieving the loss of 'Abdu'l-Bahá.

He knew that they were anxiously waiting to hear what had happened in the days and weeks before his passing, how their beloved Master had left this world, and what the funeral had been like.

Shoghi Effendi gathered his strength, and, assisted by Lady Blomfield, they gathered all the material they could find, collected all the data they could get their hands on and began writing an extraordinary, unique type of eulogy. The document they produced together was in the form of a 50-page letter dated 19 January 1922 called The Passing of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá: Compiled by Shoghi Effendi and Lady Blomfield, and it was first published in England in 1922.

As soon as it was published, Shoghi Effendi sent a copy to the Local Spiritual Assembly of Ṭihrán, instructing them to translate it into Persian and distribute to the friends in Persia and surrounding countries.

The essay opens with six accounts showing that 'Abdu'l-Bahá knew His earthly life was coming to a close, in His own words and in dreams He recounted to His family including a following prayer, revealed in His very lengthy last Tablet to the Bahá'ís of America two weeks before His passing, in which 'Abdu'l-Bahá longs for the Abhá Kingdom. Here are two verses of 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s last supplication to America:

Yá Bahá’u’l-Abhá! (O Thou the Glory of Glories) I have renounced the world and the people thereof, and am heart-broken and sorely afflicted because of the unfaithful. In the cage of this world, I flutter even as a frightened bird, and yearn every day to take my flight unto Thy Kingdom.

Yá Bahá’u’l-Abhá! Make me to drink of the cup of sacrifice and set me free. Relieve me from these woes and trials, from these afflictions and troubles. Thou art He that aideth, that succoureth, that protecteth, that stretcheth forth the hand of help.

Shoghi Effendi and Lady Blomfield describe the last two days of 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s life in great detail, from 27 to 28 November, until He passed away extremely gently and very swiftly at 1 in the morning on 28 November 1921.

'Abdu'l-Bahá’s funeral procession on 29 November 1921 is described in great detail, and four funeral eulogies are included in the essay, along with several obituaries of the Master from English, American, Egyptian, and Indian papers.

Shoghi Effendi and Lady Blomfield quote the most touching telegrams of condolences from eminent people like Sir Winston Churchill, His Majesty’s Secretary of State for the Colonies, Viscount Allenby, High Commissioner for Egypt, and from Bahá'í communities around the world.

The essay describes the seventh day memorial feast for the poor, and the fortieth day memorial feast and its speeches.

Shoghi Effendi and Lady Blomfield close their magnificent tribute with 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s inspiring words, excerpted here for the purposes of this chronology:

Friends! The time is coming when l shall be no longer with you. I have done all that could be done. I have served the Cause of Bahá’u’lláh to the utmost of my ability. I have laboured night and day, all the years of my life. O how I long to see the loved ones taking upon themselves the responsibilities of the Cause!

…I am waiting, waiting, to hear the joyful tidings that the believers are the very embodiment of sincerity and truthfulness, the incarnation of love and amity, the living symbols of unity and concord. Will they not gladden my heart? Will they not satisfy my yearning? Will they not manifest my wish? Will they not fulfil my heart’s desire? Will they not give ear to my call?

I am waiting, I am patiently waiting.

Before proceeding any further with this chronology of the life and work of Shoghi Effendi, we must take a moment to listen to what the Guardian himself has to say, in full, about the Will and Testament of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, the basis of his ministry, the foundation of Bahá'u'lláh’s divine civilization, the originating point of the Bahá'í Administrative Order, and in a very real sense, the cornerstone of any serious examination of the life and work of Shoghi Effendi, including this humble attempt.

In God Passes By, written 23 years after the Ascension of 'Abdu'l-Bahá in honor of the first 100 years of the Bahá'í Revelation Shoghi Effendi writes three long sentences about 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s Will and Testament in the fourth part of the book, titled The Inception of the Formative Age of the Bahá’í Faith 1921–1944, Chapter XXII: The Rise and Establishment of the Administrative Order.

The three sentences of Shoghi Effendi from God Passes By below address the content of the Will and Testament in great detail, offering not only the most comprehensive but also the most concise description penned by the Guardian regarding this historic and foundational document:

The Document establishing that Order, the Charter of a future world civilization, which may be regarded in some of its features as supplementary to no less weighty a Book than the Kitáb-i-Aqdas; signed and sealed by ‘Abdu’l‑Bahá; entirely written with His own hand; its first section composed during one of the darkest periods of His incarceration in the prison-fortress of ‘Akká, proclaims, categorically and unequivocally, the fundamental beliefs of the followers of the Faith of Bahá’u’lláh; reveals, in unmistakable language, the twofold character of the Mission of the Báb; discloses the full station of the Author of the Bahá’í Revelation; asserts that “all others are servants unto Him and do His bidding”; stresses the importance of the Kitáb-i-Aqdas; establishes the institution of the Guardianship as a hereditary office and outlines its essential functions; provides the measures for the election of the International House of Justice, defines its scope and sets forth its relationship to that Institution; prescribes the obligations, and emphasizes the responsibilities, of the Hands of the Cause of God; and extolls the virtues of the indestructible Covenant established by Bahá’u’lláh.

That Document, furthermore, lauds the courage and constancy of the supporters of Bahá’u’lláh’s Covenant; expatiates on the sufferings endured by its appointed Center; recalls the infamous conduct of Mírzá Yaḥyá and his failure to heed the warnings of the Báb; exposes, in a series of indictments, the perfidy and rebellion of Mírzá Muḥammad-‘Alí, and the complicity of his son Shu‘á‘u’lláh and of his brother Mírzá Badí‘u’lláh; reaffirms their excommunication, and predicts the frustration of all their hopes; summons the Afnán (the Báb’s kindred), the Hands of the Cause and the entire company of the followers of Bahá’u’lláh to arise unitedly to propagate His Faith, to disperse far and wide, to labor tirelessly and to follow the heroic example of the Apostles of Jesus Christ; warns them against the dangers of association with the Covenant-breakers, and bids them shield the Cause from the assaults of the insincere and the hypocrite; and counsels them to demonstrate by their conduct the universality of the Faith they have espoused, and vindicate its high principles.

In that same Document its Author reveals the significance and purpose of the Ḥuqúqu’lláh (Right of God), already instituted in the Kitáb-i-Aqdas; enjoins submission and fidelity towards all monarchs who are just; expresses His longing for martyrdom, and voices His prayers for the repentance as well as the forgiveness of His enemies.

Shoghi Effendi, the Guardian of the Bahá'í Faith, characterized the Will and Testament of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá as “His greatest legacy to posterity” and “the brightest emanation of His mind.” ‘Abdu’l-Bahá's Will and Testament is called "The Charter of a New World Order" by Shoghi Effendi because in this document, ‘Abdu'l-Bahá not only unveils the character of the Administrative Order of the Faith, but He also “reaffirmed its basis, supplemented its principles, asserted its indispensability, and enumerated its chief institutions.”

'Abdu'l-Bahá’s Will and Testament is invested with power such that it is not a simple document but an organ and an instrument of the Covenant, capable of sheltering all humanity under its protective shadow. The Will and Testament of 'Abdu'l-Bahá is the salvation of the Bahá'í community and the indissoluble link between the Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh and its ultimate purpose: the establishment of a New World Order.

This is how Shoghi Effendi describes the Will and Testament of 'Abdu'l-Bahá:

…this supreme, this infallible Organ for the accomplishment of a Divine Purpose.

…an Instrument which may be viewed as the Charter of the New World Order which is at once the glory and the promise of this most great Dispensation.

Before we continue with the chronology of the life of Shoghi Effendi, it behooves us to spend some time fully understanding the content of the Will and Testament of 'Abdu'l-Bahá and its structure, as this is the document conferring upon Shoghi Effendi the station of Guardian of the Faith.

The Will and Testament of 'Abdu'l-Bahá was revealed during one of the “darkest periods of His incarceration in the prison-fortress of Akká."

It is a single document, composed of three parts:

- Part One is the longest at 16 pages, 32 paragraphs, and 5,351 words.

- Part Two is seven pages, 15 paragraphs, and 2,155 words.

- Part Three is four pages, 14 paragraphs, and 1,320 words.

The content of each of these three parts is summarized briefly in the next section, with great emphasis placed on analyzing the mentions of Shoghi Effendi in the Will and Testament.

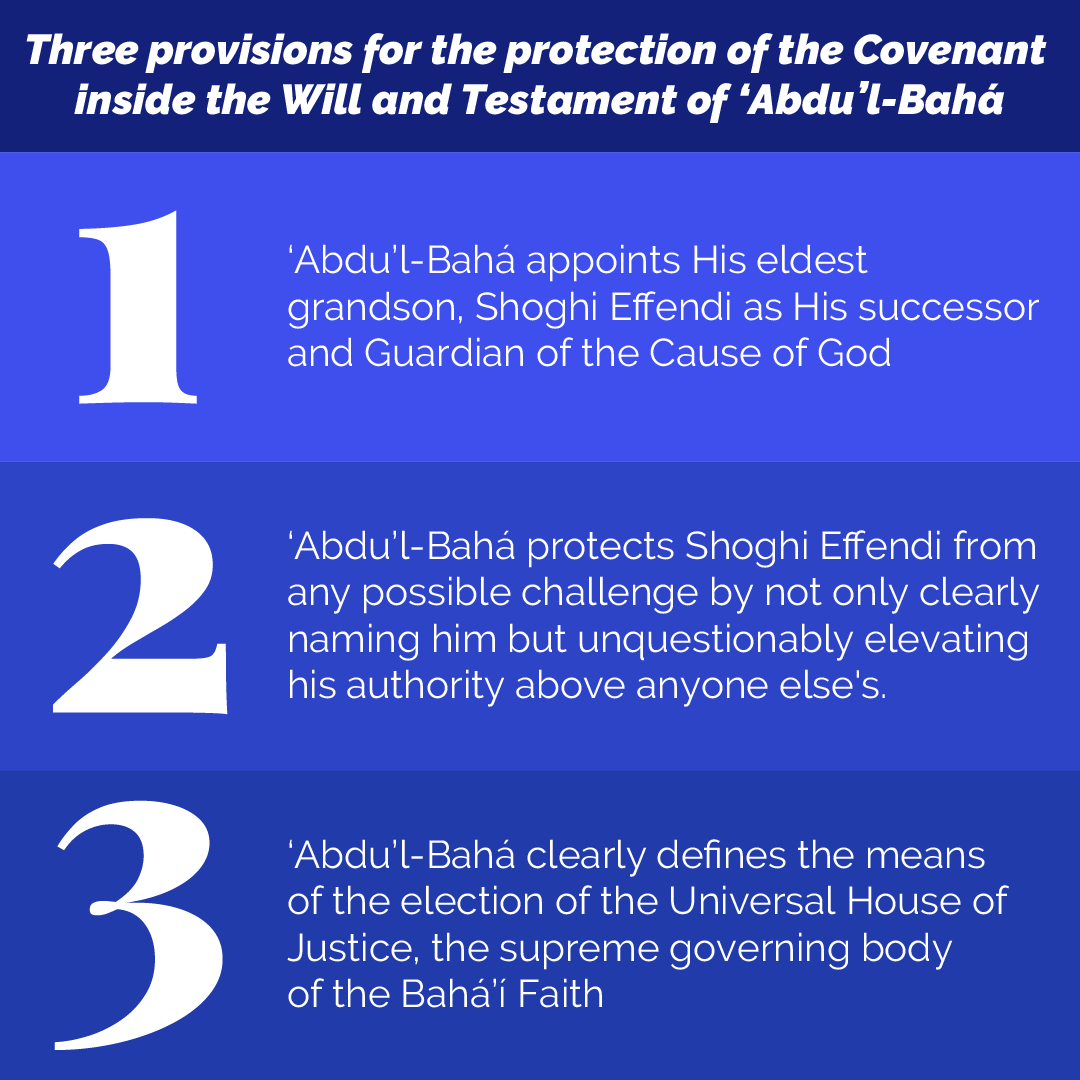

The Will and Testament of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá contains three provisions for the protection of the Bahá'í Faith after the passing of the Center of the Covenant, ‘Abdu'l-Bahá:

- First, ‘Abdu'l-Bahá appoints His eldest grandson, Shoghi Effendi as His successor and Guardian of the Cause of God..

- Second, He protects Shoghi Effendi from any possible challenge by not only clearly naming him but unquestionably elevating his authority above anyone else's.

- Lastly, ‘Abdu'l-Bahá clearly defines the means by which the Universal House of Justice, the supreme governing body of the Bahá'í Faith instituted by Bahá'u'lláh, should come into being.

Background floral tile pattern photo by elnaz asadi on Unsplash.

The Will and Testament is a long document, dealing with many, many subjects, such as obedience to Government, the behavior of Bahá'ís, the Covenant and Covenant-breaking, Mírzá Yaḥyá, Mírzá Muḥammad-'Alí, Mírzá Badí’u’lláh, the Universal House of Justice, the Hands of the Cause, the Supreme Tribunal, 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s immense suffering and many other themes, and deserves careful study.

Here, we will be looking closely at the mentions of Shoghi Effendi’s station in the Master’s Will and Testament.

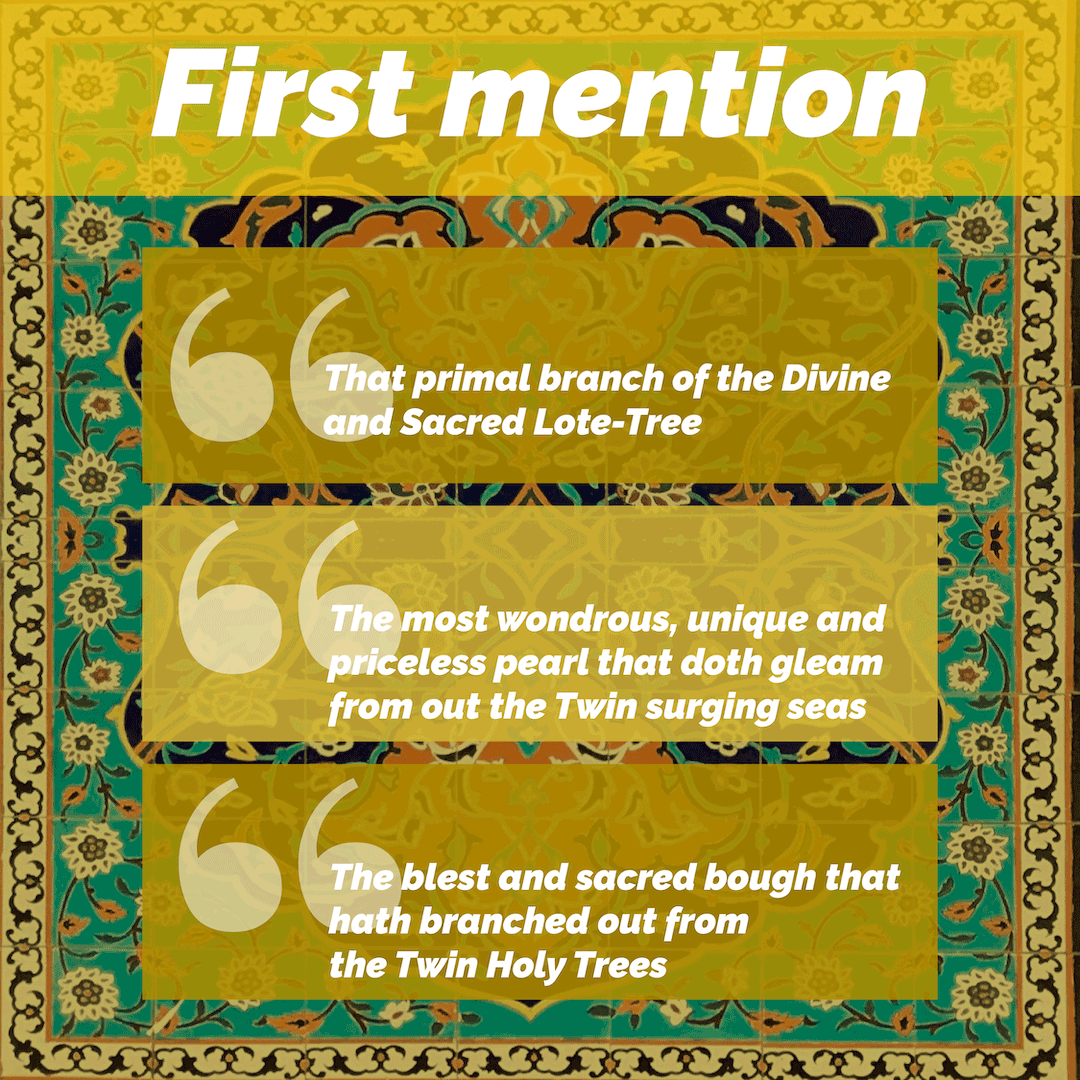

The first mention of Shoghi Effendi is in paragraph 3 of Part One:

Salutation and praise, blessing and glory rest upon that primal branch of the Divine and Sacred Lote-Tree, grown out, blest, tender, verdant and flourishing from the Twin Holy Trees; the most wondrous, unique and priceless pearl that doth gleam from out the Twin surging seas…for behold! he is the blest and sacred bough that hath branched out from the Twin Holy Trees. Well is it with him that seeketh the shelter of his shade that shadoweth all mankind.

This paragraph is long and only references to Shoghi Effendi were kept. It begins majestically, describing Shoghi Effendi as the “primal branch” of the Twin Holy Trees of the families of the Báb and Bahá'u'lláh, and re-emphasizes this point by calling him the “priceless pearl” that gleams from the Twin surging seas, again, the families of both Manifestations of God. At the end of the paragraph, 'Abdu'l-Bahá insists again on Shoghi Effendi’s dual heritage by referring to him as “the blest and sacred bough that has branched out from the Twin Holy Trees.”

This entire paragraph, a masterfully eloquent opening to His Will and Testament, sets forward incontrovertibly that Shoghi Effendi’s station is far beyond anyone else in 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s family. 'Abdu'l-Bahá makes the point three times.

The last time 'Abdu'l-Bahá speaks about Shoghi Effendi in this paragraph, He uses a turn of phrase Bahá'u'lláh had once used to describe Him, and the similarity is extraordinary:

This is how Bahá'u'lláh had spoken about 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s station in the Súriy-i-Ghúṣn:

There hath branched from the Sadratu’l-Muntahá this sacred and glorious Being, this Branch of Holiness; well is it with him that hath sought His shelter and abideth beneath His shadow.

And compare it to this sentence, 'Abdu'l-Bahá speaking about Shoghi Effendi in His Will and Testament:

behold! he is the blest and sacred bough that hath branched out from the Twin Holy Trees. Well is it with him that seeketh the shelter of his shade that shadoweth all mankind.

Background floral tile pattern photo by elnaz asadi on Unsplash.

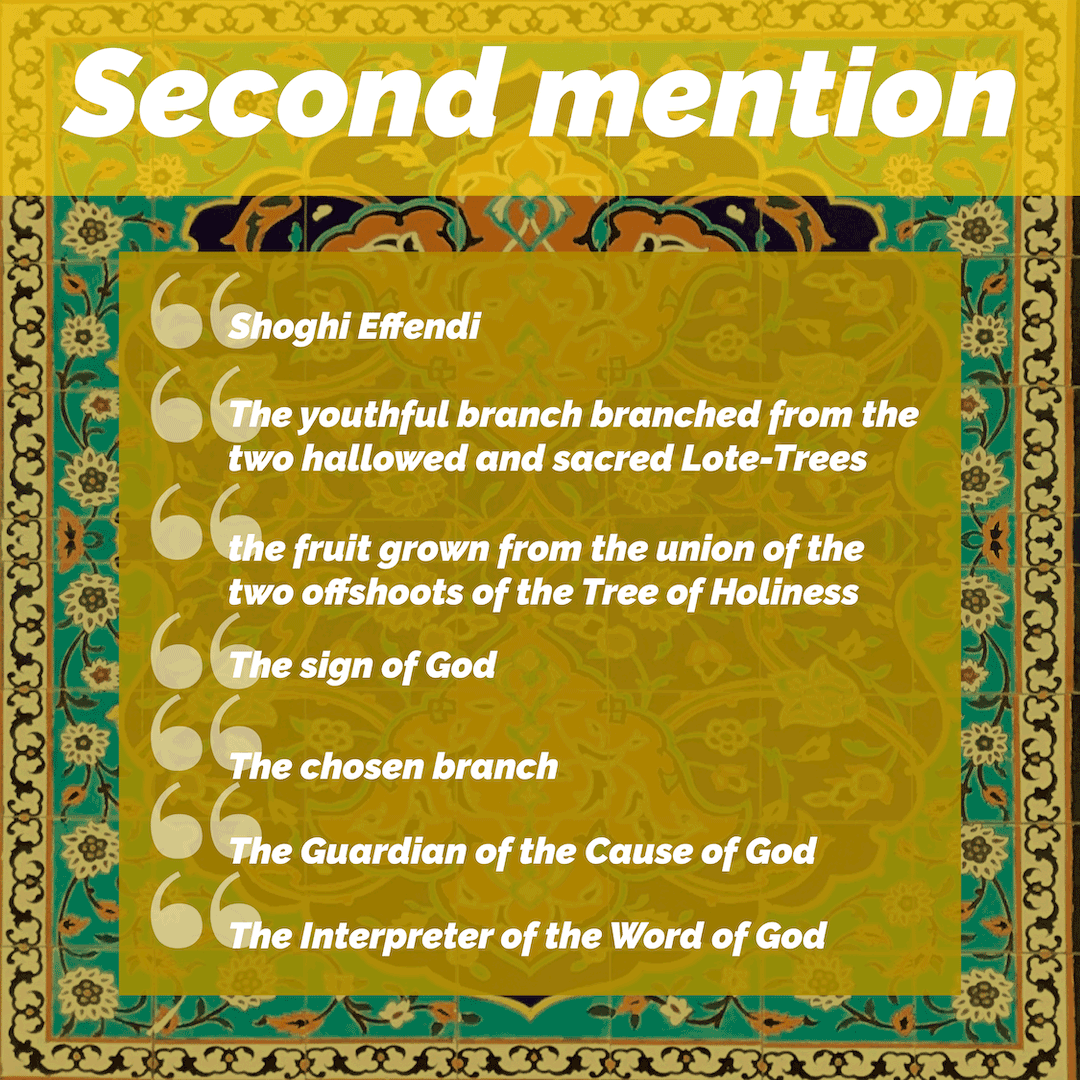

'Abdu'l-Bahá expounds again on Shoghi Effendi’s station in paragraph 17 of Part One:

O my loving friends! After the passing away of this wronged one, it is incumbent upon the Aghsán (Branches), the Afnán (Twigs) of the Sacred Lote-Tree, the Hands (pillars) of the Cause of God and the loved ones of the Abhá Beauty to turn unto Shoghi Effendi—the youthful branch branched from the two hallowed and sacred Lote-Trees and the fruit grown from the union of the two offshoots of the Tree of Holiness,—as he is the sign of God, the chosen branch, the Guardian of the Cause of God, he unto whom all the Aghsán, the Afnán, the Hands of the Cause of God and His loved ones must turn. He is the Interpreter of the Word of God and after him will succeed the first-born of his lineal descendents.

In the opening line of this paragraph, 'Abdu'l-Bahá makes two references to Shoghi Effendi’s exalted lineage: “the youthful branch branched from the two hallowed and sacred Lote-Trees” and “the fruit grown from the union of the two offshoots of the Tree of Holiness.”

Immediately after this, 'Abdu'l-Bahá bestows three extraordinarily important titles on Shoghi Effendi, perhaps the three most important phrases in the entire Will and Testament. 'Abdu'l-Bahá calls Shoghi Effendi “the Sign of God,”, “the Guardian of the Cause of God,” and “the Interpreter of the Word of God,” and calls on all male descendants and relatives of the Báb and Bahá'u'lláh, and the Hands of the Cause to turn to him.

Background floral tile pattern photo by elnaz asadi on Unsplash.

Immediately after the paragraph in which 'Abdu'l-Bahá officially calls Shoghi Effendi the Guardian for the first time, He continues, in the very next section, paragraph 18, and opens with his title instead of his name for the first time in the Will and Testament:

The sacred and youthful branch, the Guardian of the Cause of God, as well as the Universal House of Justice to be universally elected and established, are both under the care and protection of the Abhá Beauty, under the shelter and unerring guidance of the Exalted One (may my life be offered up for them both). Whatsoever they decide is of God.

This paragraph is immensely important because it lays out as fact the infallibility of the Guardian and the Universal House of Justice with the sentence: “the Guardian of the Cause of God, as well as the Universal House of Justice…are both under the care and protection of the Abhá Beauty, under the shelter and unerring guidance of the Exalted One. Whatsoever they decide is of God.”

The remainder of this long paragraph, which has been omitted, consists of 'Abdu'l-Bahá issuing several extremely emphatic warnings against Covenant-breaking. 'Abdu'l-Bahá cautioning all Bahá'ís to obedience, firmness and steadfastness in the Covenant, and 'Abdu'l-Bahá delineates all possible spiritual dangers in this matter:

- Disobeying the Guardian or the Universal House of Justice;

- Rebelling against them;

- Opposing them;

- Contending with them;

- Disputing with them;

- Denying them;

- Disbelieving in them;

- Deviating from them;

- Separating from them;

- Turning aside from them;

And lest there be any doubt, 'Abdu'l-Bahá applies all these warnings implicitly to the Members of the Universal House of Justice who are bound to the Guardian with obedience, submissiveness and subordination.

Background floral tile pattern photo by elnaz asadi on Unsplash.

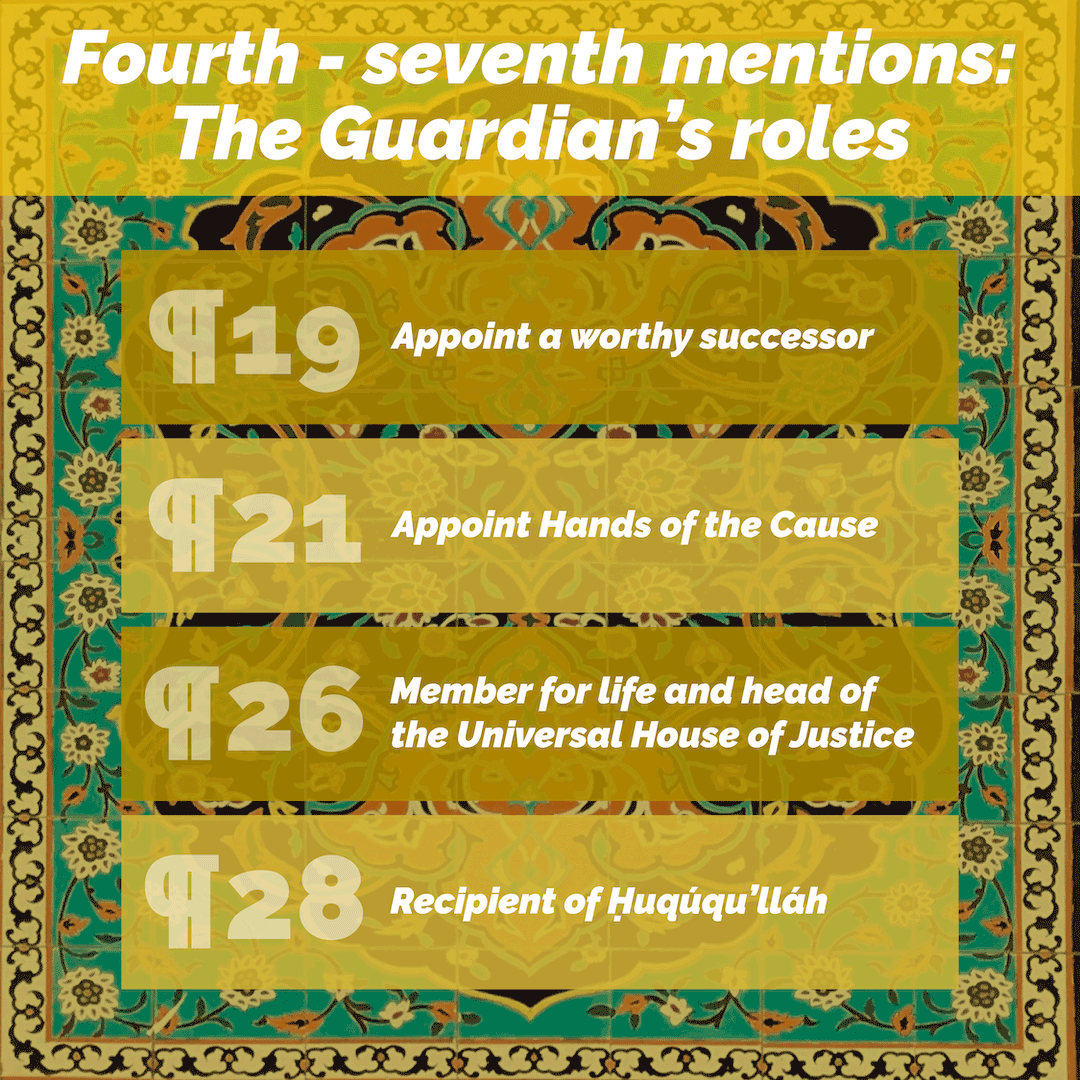

In the rest of Part One, 'Abdu'l-Bahá specifies several roles for the Guardian inside thematic paragraphs on other topics:

- In paragraph 19, 'Abdu'l-Bahá states that the Guardian must appoint a worthy successor in his lifetime;

- In paragraph 21 He says that the Guardian must appoint Hands of the Cause, who act under his command;

- In paragraph 26 'Abdu'l-Bahá appoints the Guardian as member for life and head of the Universal House of Justice;

- And in paragraph 28 'Abdu'l-Bahá directs that Ḥuqúqu’lláh must be paid to the Guardian of the Cause.

Background floral tile pattern photo by elnaz asadi on Unsplash.

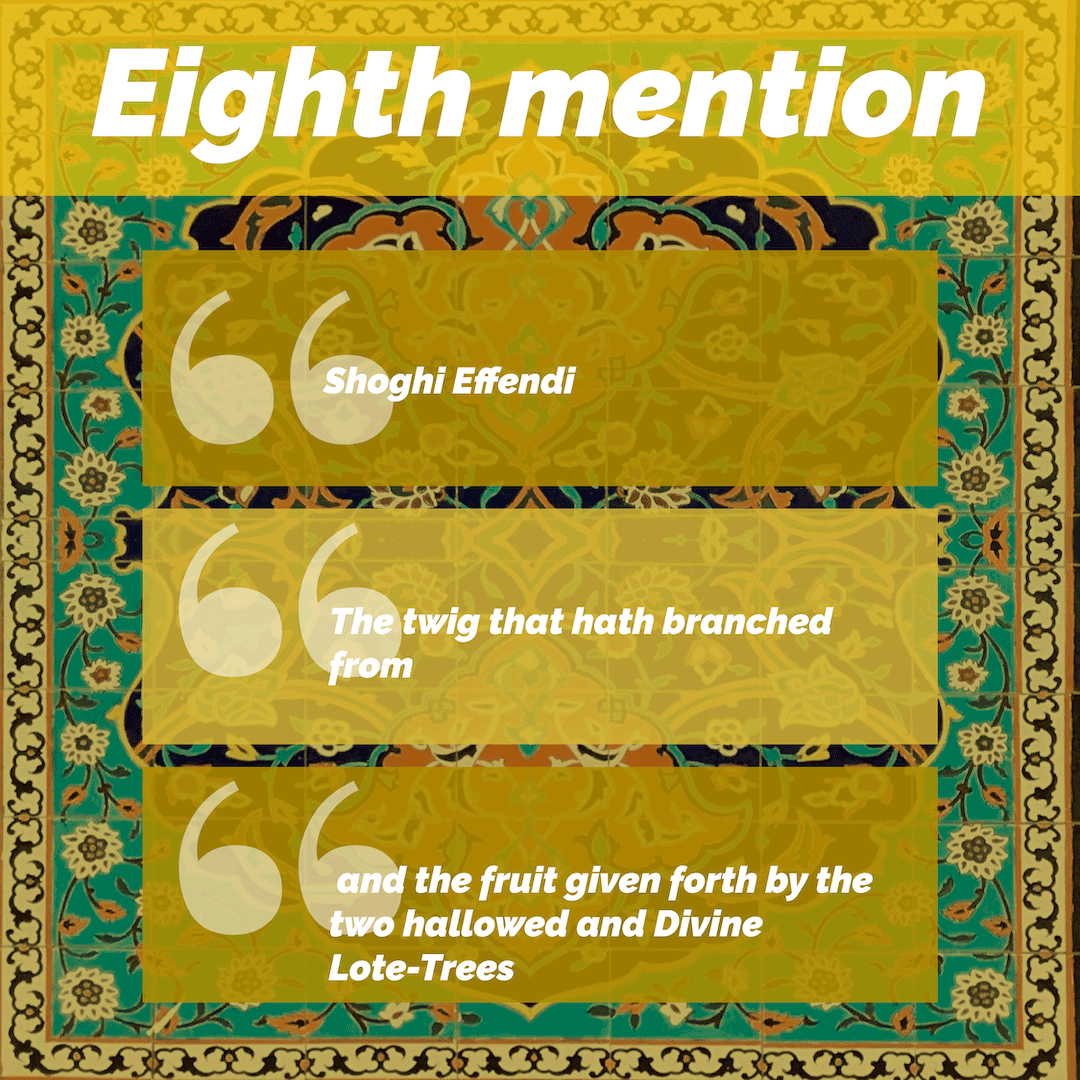

Shoghi Effendi is not mentioned in Part Two of 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s Will and Testament, and the next mention appears in the penultimate paragraph of the entire Will before a closing greeting, paragraph 12, where the Master has touching words about the well-being of His grandson:

O ye the faithful loved ones of `Abdu'l-Bahá! It is incumbent upon you to take the greatest care of Shoghi Effendi, the twig that hath branched from and the fruit given forth by the two hallowed and Divine Lote-Trees, that no dust of despondency and sorrow may stain his radiant nature, that day by day he may wax greater in happiness, in joy and spirituality, and may grow to become even as a fruitful tree.

This paragraph contains the fifth mention of Shoghi Effendi’s descendance of the ‘Báb and Bahá'u'lláh: “the twig that hath branched from and the fruit given forth by the two hallowed and Divine Lote-Trees.” By repeating this unalienable fact, 'Abdu'l-Bahá is establishing Shoghi Effendi’s undeniable right as His chosen successor.

'Abdu'l-Bahá speaks tender and loving words about His favored grandson, entrusting him to the followers of Bahá'u'lláh, who are asked to not only care for him, but endeavor to prevent him from being hurt and saddened.

This is a deeply intimate section, one where we can hear 'Abdu'l-Bahá the Grandfather as well as 'Abdu'l-Bahá the Center of the Covenant speaking about a being He knows as well as His own self. 'Abdu'l-Bahá knew that at the heart of Shoghi Effendi was a deeply radiant nature, and He also knew that, as the Guardian, he would accomplish so much if only he were happy and joyful. Unfortunately, Shoghi Effendi would fulfill his role burdened by sorrow and heartbreak. How much more he could have done had the Bahá'ís only obeyed the Master and been faithful.

Background floral tile pattern photo by elnaz asadi on Unsplash.

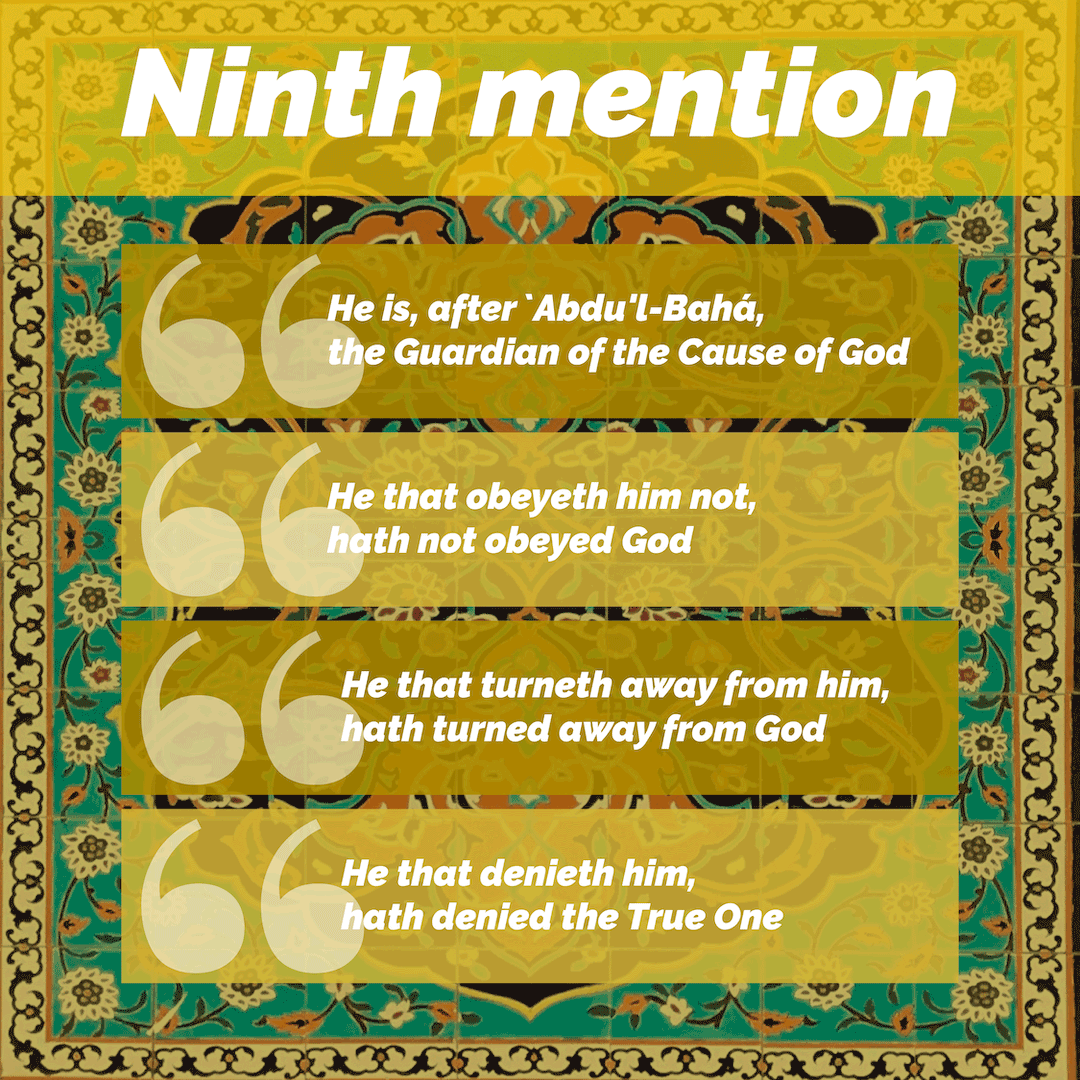

Immediately following the previous paragraph is the penultimate paragraph of the entire Will before a closing greeting, paragraph 13, where the Master reiterates the power of the Covenant:

For he is, after `Abdu'l-Bahá, the Guardian of the Cause of God, the Afnán, the Hands (pillars) of the Cause and the beloved of the Lord must obey him and turn unto him. He that obeyeth him not, hath not obeyed God; he that turneth away from him, hath turned away from God and he that denieth him, hath denied the True One. Beware lest anyone falsely interpret these words, and like unto them that have broken the Covenant after the Day of Ascension (of Bahá'u'lláh) advance a pretext, raise the standard of revolt, wax stubborn and open wide the door of false interpretation. To none is given the right to put forth his own opinion or express his particular conviction. All must seek guidance and turn unto the Center of the Cause and the House of Justice. And he that turneth unto whatsoever else is indeed in grievous error.

The words “For he is, after 'Abdu'l-Bahá, the Guardian of the Cause” are majestic and could not be clearer. 'Abdu'l-Bahá has, several times in this Will and Testament, made it clear that Shoghi Effendi is His chosen and worthy successor, but these words are a definite statement of fact that leaves no room for interpretation.

'Abdu'l-Bahá’s repeats the same instruction in the last words of His Will and Testament as in paragraph 17 of Part One: the descendents of the Báb and Bahá'u'lláh, the Hands of the Cause and all Bahá'ís must obey and turn to Shoghi Effendi, the Guardian of the Cause of God.

The Master cautions the disobedient and the unfaithful, and warns the Bahá'ís not to let the Covenant-breaking that had arisen after Bahá'u'lláh’s Ascension repeat itself after His own passing.

In closing His Will and Testament, 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s last words are a final warning to turn to the Guardian and the Universal House of Justice.

The ministry of the Guardian was characterized by a stupendous release of spiritual forces which enabled Shoghi Effendi to prosecute his divinely-ordained charge with colossal success.

He single-handedly spearheaded the birth of the Administrative Order, lovingly encouraged its nascent institutions worldwide, he increased the endowments of the Faith at the Bahá'í World Centre and in countries all around the world, he built the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb, the Monument Gardens, the International Bahá'í Archives, he launched three major teaching Plans and led the Bahá'ís to unprecedented victories in the promulgation of the Faith of Bahá'u'lláh.

On the other hand, throughout the 36 years of his ministry, he was plagued by untold suffering, agony, anguish, and tribulation at the hands of Covenant-breakers.

These two aspects of the Guardian’s ministry: the light of his superb achievements and the and the dark shadow of Covenant-breaking, are inseparable parts of his life.

Covenant-breakers arose to oppose the Guardian as Head of the Cause. These dark-hearted individuals were consumed with ambition, insanity, hatred, ego, jealousy. They thought they could either destroy the Faith, discredit the Guardian, or take over his position, setting themselves up as a rival faction, and win the Bahá'ís to their side and their own erroneous, blatantly false interpretation of the Teachings of Bahá'u'lláh, eventually running the Bahá'í Faith the proper way, meaning the way they thought it should be run.

No one ever succeeded. But they did not stop trying.

But the Covenant-breaker ringleaders did manage to win the souls of misguided, foolish Bahá'ís. The excommunicated outliers continued to try and win over and pervert the faithful Bahá'ís.

To help us understand Covenant-breaking, Rúḥíyyih Khánum explains the principle of light and shadow, the brighter the light at the center of the Faith, the darker and blacker the shadow of Covenant-breaking:

No proper picture of Shoghi Effendi's life can be obtained without reference to the subject of Covenant-breaking. The principle of light and shadow, setting each other off, the one intensifying the other, is seen in nature and in history; the sun casts shadows; at the base of the lamp lies shadow; the brighter the light the darker the shadow; the evil in men calls to mind the good, and the greatness of the good underlines the evil.

Bahá'í author and research Dr. Moojan Momen isolates four types of Covenant-breaking in the Bahá'í Faith:

- Leadership challenges: People who dispute either the legitimacy of the authority of the Head of the Faith, claiming they are the rightful authority. These include Mírzá Muḥammad-'Alí and Mason Remey, after the Guardian’s passing.

- Dissidence: Individuals who disagree with the policies and actions of the Head of the Faith but don’t claim leadership. These include: Ahmad Sohrab and Ruth White.

- Disobedience: These are believers who disobey a direct instruction from the Head of the Faith, such as ceasing to associate with Covenant-breakers.

- Vicious attacks: In this category are former Bahá'ís who maliciously attack the Bahá'í Faith. An example of this is Avárih.

We will be looking at the main Covenant-breakers during the Guardian’s ministry: Avárih, Ruth White, Ahmad Sohrab, and Shoghi Effendi’s family in the following sections throughout the chronology.

“Snake.” Original photo: Photo by Meg Jerrard on Unsplash.

Towards the end of 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s ministry, the old band of Covenant-breakers led by Mírzá Muḥammad-'Alí—the Arch-breaker of the Covenant of Bahá'u'lláh and the faithless half-brother of 'Abdu'l-Bahá—had receded into the shadows because of 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s magnetic personality and the years of prestige that characterized the last decades of His extraordinary life, including His Knighthood by the British government, His majestic Tablets of the Divine Plan, and the esteem in which the British authorities held Him.

After the Ascension of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, when Shoghi Effendi became the Guardian, when the Bahá'í world itself wad dimmed and weakened with grief, the old Covenant-breakers from the time of the Master crawled out their dark recesses and took full advantage of the shock caused by the Master’s passing, particularly during the eight months when Shoghi Effendi had to leave the Holy Land for Switzerland.

This was when Covenant-breakers found themselves infused with a new supply of venomous, mischievous energy, and they unleashed their attacks on the Faith of Bahá'u'lláh and its 24-year-old leader. The old guard of Covenant-breakers, led by Mírzá Muḥammad-'Alí enrolled the entire family of 'Abdu'l-Bahá under into their black cause, and the defection of the entirety of Shoghi Effendi’s relatives is addressed in full in 1941.

“Gathering Storm.” Original photo: Photo by Max LaRochelle on Unsplash.

In the weeks before and after 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s passing, He and the Greatest Holy Leaf had to manage worldwide rumblings of Covenant-breaking.

'Abdu'l-Bahá had been deeply concerned with Covenant-breaking in America, and had cabled Roy Wilhelm who responded on 8 November 1921 that there were serious Covenant-breaking activities in Chicago, Washington and Philadelphia from the henchmen of Mírzá Muḥammad-'Alí, the Arch-breaker of the Covenant of Bahá'u'lláh.

'Abdu'l-Bahá had responded with a cable that ended:

Certainly shun violators.

By 14 December 1921, two weeks before Shoghi Effendi arrived in Haifa, the Greatest Holy Leaf sent a cable to America following up on the Covenant-breaking activity there, with strict instructions:

Now is period of great tests. The friends should be firm and united in defending the Cause. Nakeseens [Covenant-breakers] starting activities through press other channels all over world. Select committee of wise cool heads to handle press propaganda in America.

In America, many reports detailed accusations and facts on the new Guardian, and Shoghi Effendi received a letter from a staunch American Bahá'u'lláh on 18 January 1922 which read:

As you know we are having great troubles and sorrows with violators in the Cause in America. This poison has penetrated deeply among the friends…

Shortly after 'Abdu'l-Bahá's Ascension, Mírzá Muḥammad-'Alí, His disgruntled and treacherous half-brother, had filed a claim, based on Islamic law for a portion of the 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s estate.

By 24 January 1922, the High Commissioner for Palestine, Sir Herbert Samuel demanded from Shoghi Effendi to be informed what was going on with the situation:

I am much interested to learn of the measures that have been taken to provide for the stable organization of the Bahá'í Movement.

Shoghi Effendi was beginning his Guardianship having inherited this volatile Covenant-breaking situation.

Original image: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

Mírzá Muḥammad-'Alí began actively plotting, and petitioned the civil authorities of Palestine to turn over custodianship of the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh, stating that he was 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s lawful successor.

The British authorities refused to act in what they saw was a religious dispute, and when Mírzá Muḥammad-'Alí appealed to the Mufti of 'Akká to intervene on his behalf, the Mufti refused, so he sent his younger brother, Mírzá Badí’u’lláh, along with other Covenant-Breakers to the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh, and on Tuesday 30 January, they stole the keys of the Most Holy Shrine based on their false claim that they were the closest surviving relatives of Bahá'u'lláh.

Their despicable act caused such a commotion in the Bahá'í community that the Governor of 'Akká ordered the keys remanded into the hands of the authorities and refused to return them to Mírzá Muḥammad-'Alí or to Shoghi Effendi.

No one could enter the Shrine, they could only stand outside of it, and Shoghi Effendi was deeply distressed, however, he followed 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s example, and, although encompassed by severe tests, he calmly gave instructions as to where to place lights inside and outside the Shrine, which was being electrified at the time, a process that had been started by the Master in the last months of His life.

On 13 June 1922, the dispute over custody of the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh was reported to Winston Churchill, stating a number of telegrams from around the world supported Shoghi Effendi’s’ claim.

By 23 June 1922, the government of the British Mandate in Palestine was forced to intervene and a temporary arrangement that the keys of the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh should be held by the Sub-Governor of 'Akká and be made available to Bahá'í pilgrims and visitors and posted a guard at the entrance, but a decision as to who had the custodianship of the Shrine would not be reached for several months.

A digital painting of an alembic for distilling essential oils. Original image inspiration: Etsy.

In a deeply significant paragraph of the Priceless Pearl, Rúḥíyyih Khánum describes the “alembic of [the Guardian’s] creative mind.”

Rúḥíyyih Khánum uses the adjective “alembic” for a very specific reason, central to this story, and it is important we understand exactly what she means by it, for us to appreciate the depth of what she is about to share with us regarding the Guardian’s creative mind.

Alembic is usually used as a noun, almost never as an adjective, as Rúḥíyyih Khánum creatively uses it. The roots of the word are found in Medieval Latin, originally from the Greek “ambix” (“cup with a spout”). Alembics were medieval pre-chemistry devices used for distilling liquids—like alcohol—but they were also used in places like Persia, for example for distilling perfume from flowers like violets, gardenias, jasmine, or lilac. In Persia, they used alembics to make rose water or attar of rose. An alembic is a series of two connected devices. For making rosewater, the first would be a small to large copper pot filled with pure water and thousands upon thousands of rose petals, set over a fire. As the water begins to boil, the precious steam is not allowed to escape, but rather gathered into tubes in which the vapor condenses into sweet-smelling rosewater, and it finally distills into an alembic, which at the end of the entire process becomes filled with rose water or attar of rose.

That the Guardian’s mind was “alembic” meant it could distill anything and purify and elevate it. Essentially, what Rúḥíyyih Khánum is saying is that the Guardian’s mind was transformational and would with events, writings, and the Bahá'í Teachings exactly what a physical alembic device did by distilling, transforming thousands of rose petals into precious attar of rose. That is the essence of what Rúḥíyyih Khánum meant.

And so this is what Rúḥíyyih Khánum has to say: over the course of his 36-year ministry, the Guardian of the Cause had distilled in his creative mind all of the component elements of the Faith of Bahá'u'lláh into one, great, indivisible, distilled whole.

He had created a united, tethered worldwide Bahá'í community from a disparate mass of disconnected believers that awoke on 29 November 1921 to find 'Abdu'l-Bahá, their Father, their Leader and the Center of the Covenant, gone.

The Guardian had woven the teachings of the Báb, Bahá'u'lláh, and 'Abdu'l-Bahá into a shining cloak that would clothe and protect the vibrant, organized community of the followers of Bahá'u'lláh for 1,000 years, a cloak, Rúḥíyyih Khánum stated, Which bore the make of the Guardian’s mark:

…a cloak on which the fingers of Shoghi Effendi had picked out the patterns, knitted the seams, fashioned the brilliant protective clasps of his interpretations of the Sacred Texts, never to be sundered, never to be torn away until that day when a new Law-giver comes to the world and once again wraps His creature man in yet another divine garment.

Vineyard photo by Dan Meyers on Unsplash.

From the beginning of his Guardianship, Shoghi Effendi regularly had to readjust the Bahá'ís’ understanding of his position in the Faith.

On 5 March 1922, Shoghi Effendi included a post-script in a letter to the American believers:

May I also express my heartfelt desire that the friends of God in every land regard me in no other light but that of a true brother, united with them in our common servitude to the Master's Sacred Threshold, and refer to me in their letters and verbal addresses always as Shoghi Effendi, for I desire to be known by no other name save the one our Beloved Master was wont to utter, a name which of all other designations is the most conducive to my spiritual growth and advancement

In 1924, Shoghi Effendi cabled India a very definite instruction:

My birthday should not be commemorated.

In 1930, Shoghi Effendi’s secretary had answered a letter with a firm statement on Shoghi Effendi’s station:

Concerning Shoghi Effendi's station: he surely has none except what the Master confers upon him in His Will and that Will also states what Shoghi Effendi's station is. If anyone misinterprets one part of the Will he misinterprets all the Will.

By 1934, Shoghi Effendi addressed the question of his station clear, once and for all: