Written and illustrated by Violetta Zein

This part covers the life of Shoghi Effendi from the age of 23 in 1920 to the age of 24 in 1921.

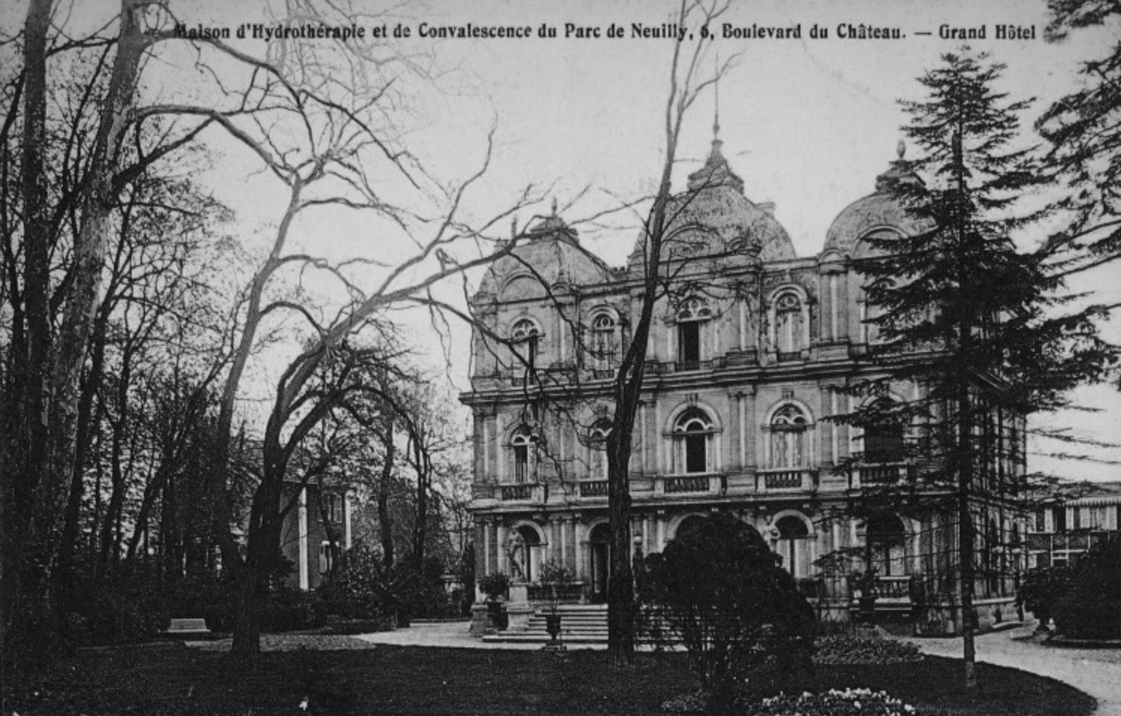

La Maison d’hydrothérapie et de convalescence du Parc de Neuilly, where Shoghi Effendi recovered from his fatigue before going to England to study at Oxford. Source : Cartorum (public domain).

At last, time came for Shoghi Effendi too to leave Haifa, but he had expended every last ounce of his energy throwing himself into serving 'Abdu'l-Bahá for nearly two years and he was utterly depleted. 'Abdu'l-Bahá arranged for him to recover his health at a sanatorium.

Sanatoriums were an important part of life in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The term “sanatorium” is antiquated, and today we would call them specialized hospitals, spas, retreats, or treatment centers depending on their aim, but staffed with trained medical personnel and dedicated to treating convalescent people, those with chronic illnesses, and those suffering—like Shoghi Effendi did—from exhaustion which we now call burn-out.

Most sanatoriums were in beautiful countryside, with fresh, invigorating, clean air, a welcome change from the smoky, polluted air of the early 20th century cities, where chimneys, factories, trains constantly blew toxic charcoal smoke everywhere.

The place 'Abdu'l-Bahá had chosen for Shoghi Effendi was a sanatorium in Neuilly, a suburb of Paris called La maison d’hydrothérapie et de convalescence du Parc de Neuilly—which literally translates as “Parc de Neuilly hydrotherapy and convalescent home,” located in a beautiful woodsy suburb northwest of Paris.

Shoghi Effendi, because of the uncommon pressures of his one-of-a-kind station and responsibility, compounded by the fact he had a rare tenderness of heart and sensitive soul, would suffer from burn-out for the rest of his life. He would always work at the edge of burn-out until he became so run down he was too tired to even sleep. This would be the lifelong reason the future Guardian would have to spend months every year in Switzerland, as Shoghi Effendi, to recover enough to return to Haifa and be the Guardian. The spring of 1920 was the first episode. There would be many more.

'Abdu'l-Bahá—in His immense love for his cherished grandson—had nonetheless let Shoghi Effendi out of His sight with very strict instructions: he must undergo treatment, he must recuperate, and he was not to open a book during his stay. 'Abdu'l-Bahá was so thoughtful and caring about Shoghi Effendi’s health, He even arranged for Dr. Luṭfu’lláh Ḥakím to accompany Shoghi Effendi from the Holy Land to France.

“The Master is in splendid health”: Shoghi Effendi was so encouraged and uplifted by the good health of 'Abdu'l-Bahá that the shock of His sudden passing was infinitely multiplied. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá receiving His Knighthood from the British Empire on 27 April 1920, 11 days before Shoghi Effendi wrote this letter to his friend ‘Alí Yazdí. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

On 24 May 2020, Shoghi Effendi wrote a letter to ‘Alí Yazdí, in which it is abundantly clear that Shoghi Effendi himself realized the gravity of his health situation as he describes it to ‘Alí:

I have not forgotten you, but do you know and realize what crisis I have passed and into what state of health I have fallen! For a month I have stayed and am still staying in this “maison de convalescence” away from Paris and its clamor in bed until noon, receiving…treatment and following the Master’s instructions not to open a book during my stay in this place.

Eighteen months before 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s passing there was absolutely no indication he would die. Shoghi Effendi was so confident he told ‘Alí:

The Master is in splendid health.

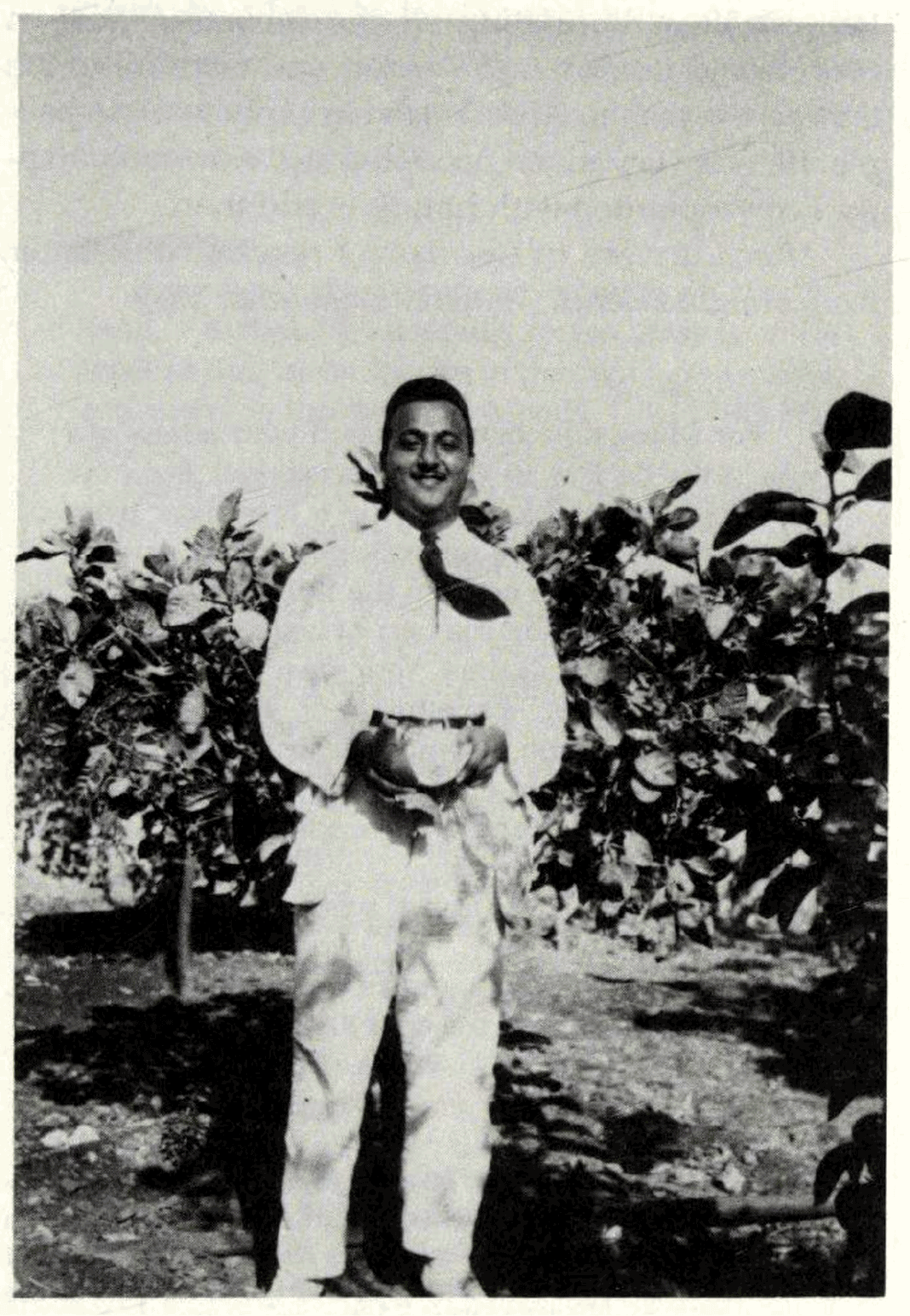

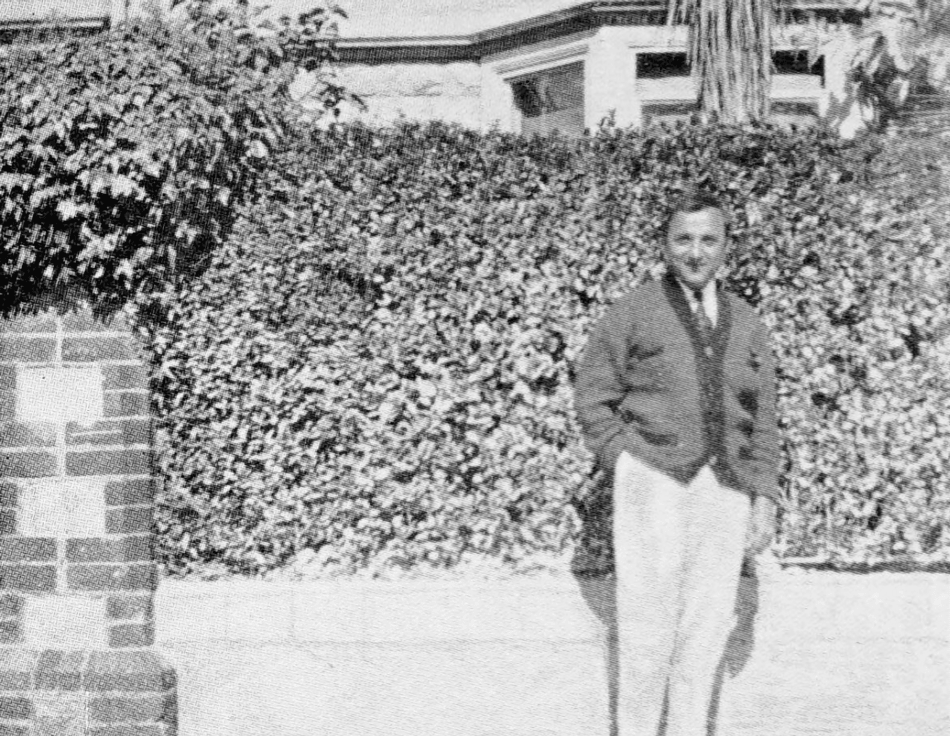

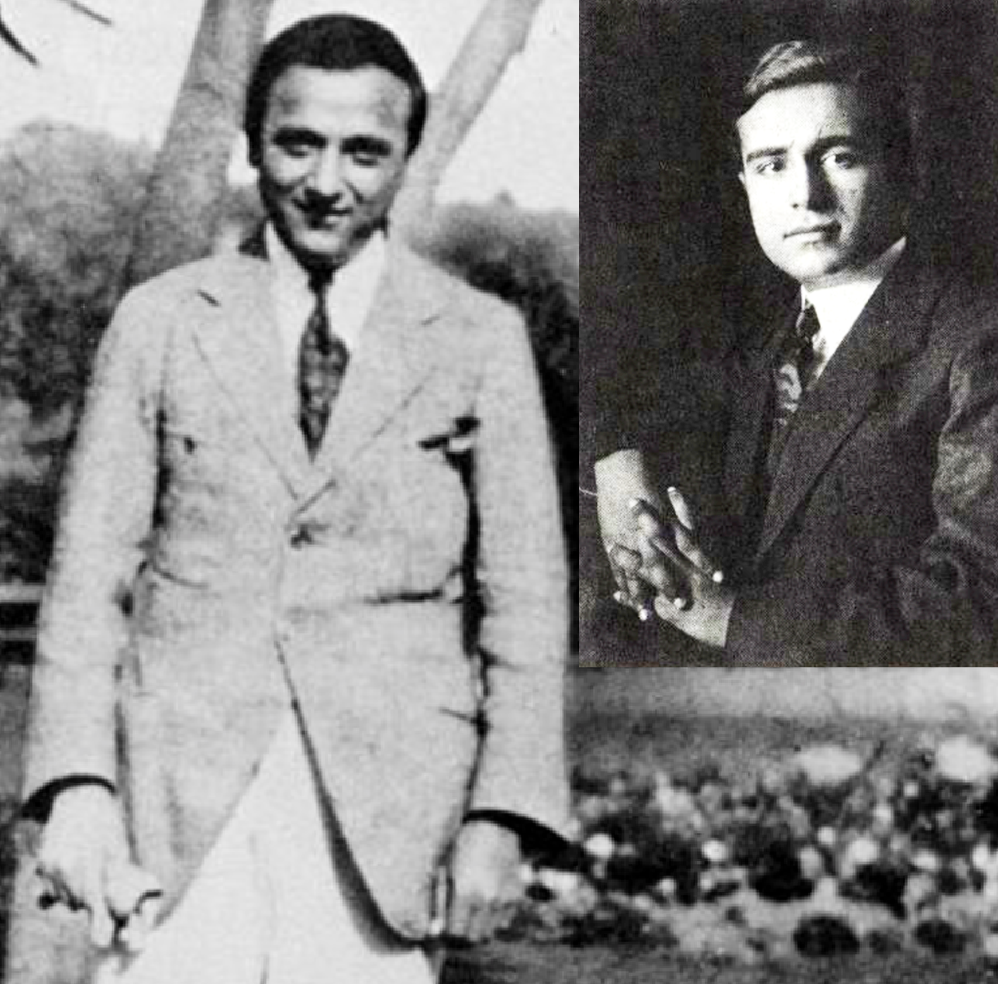

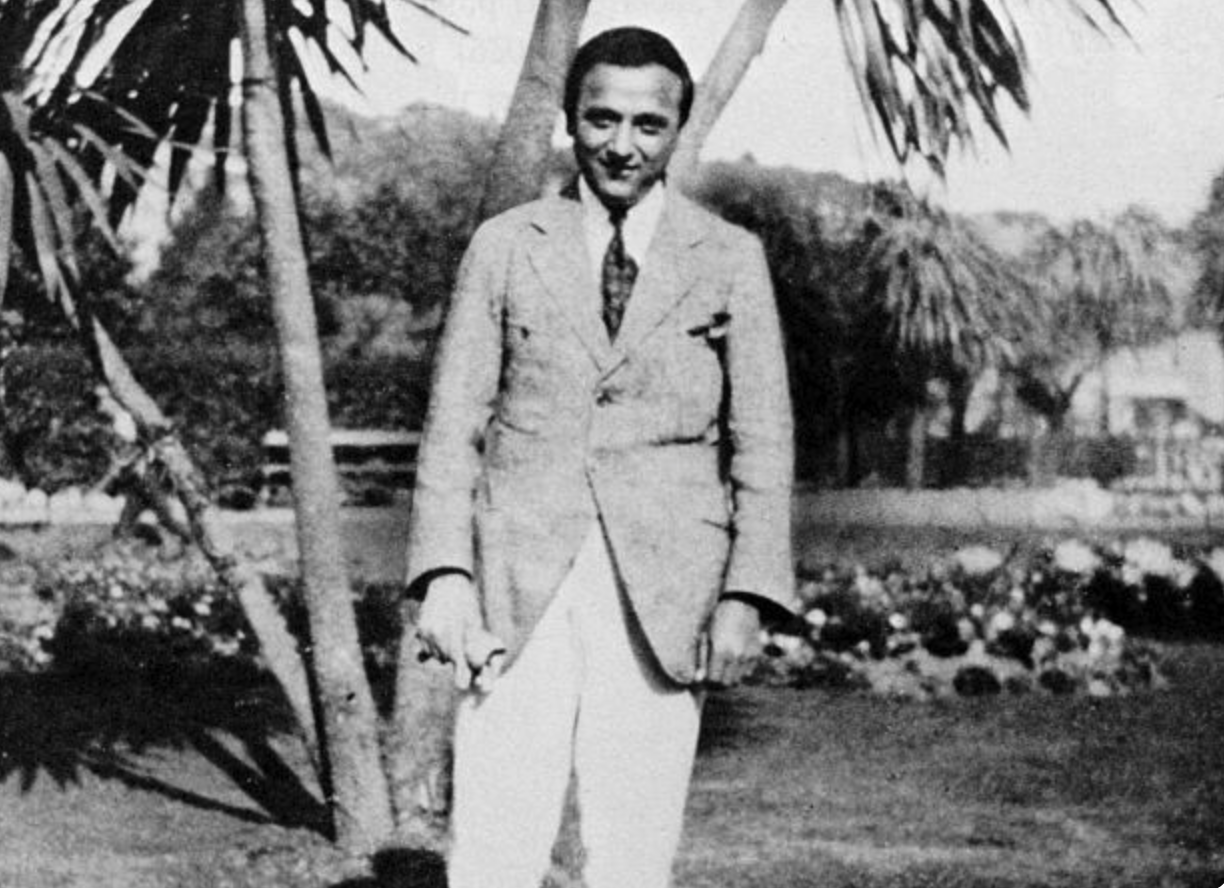

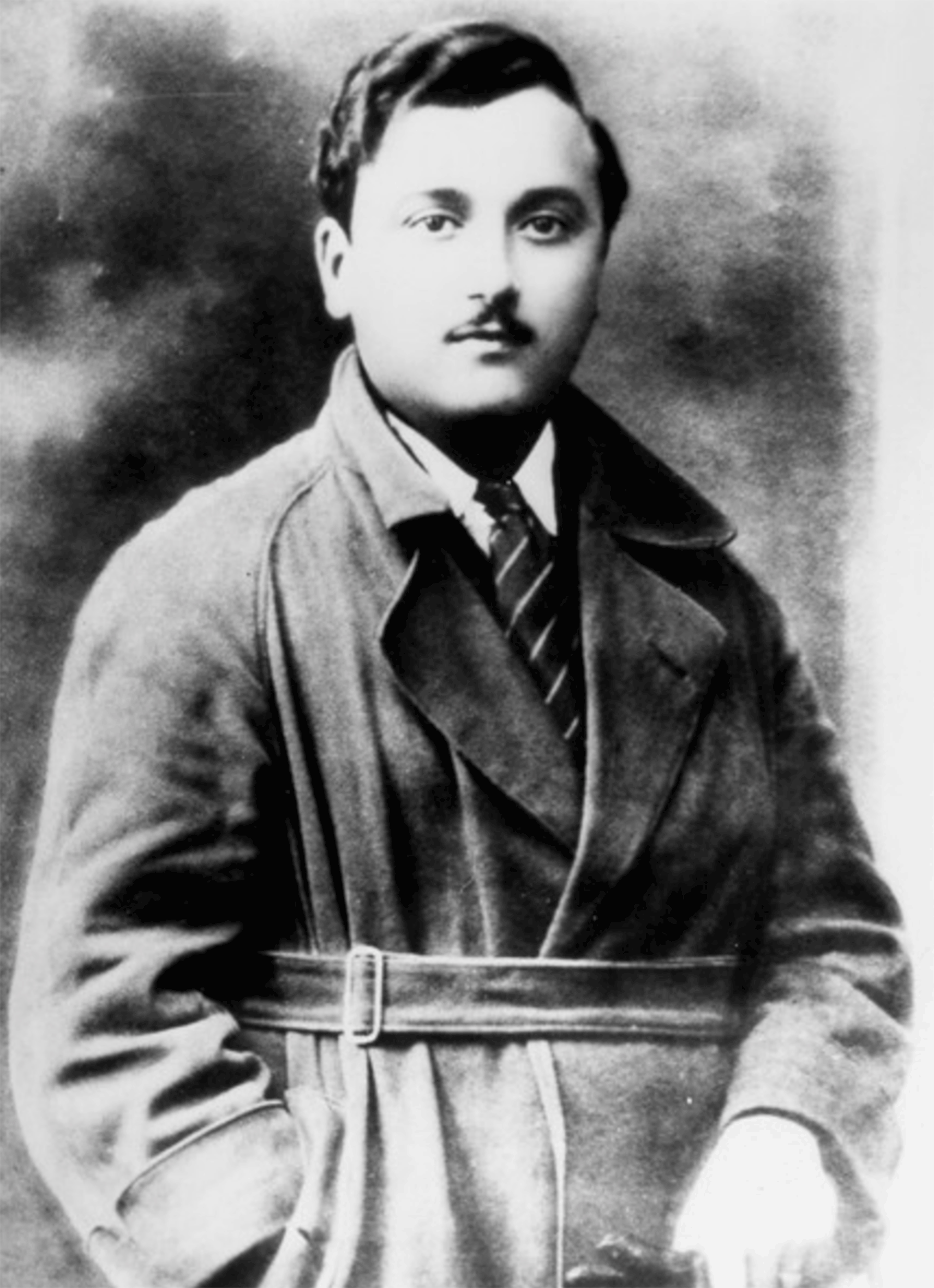

Shoghi Effendi in his twenties. Source: Blessings Beyond Measure, ‘Alí Yazdí, page 69.

Shoghi Effendi applied to Oxford as a non-collegiate student from the sanatorium, and his aim, in his letter of application was crystal clear:

My sole aim is to perfect my English, to acquire the literary ability to write it well, speak it well & translate correctly & eloquently from Persian & Arabic into English. My aim is to concentrate for two years upon this object & to acquire it through the help of a tutor, by attending lectures, by associating with cultured & refined literary circles & by receiving exercises in Phonetics.

While in Oxford, Shoghi Effendi will clarify his academic objectives in a 17 September 1920 letter to Mr. and Mrs. Scott in Paris:

I have been immersed in my studies – all having as an end a better ability in translating the words of Bahá’u’lláh and a fuller knowledge & better expression in expounding its principles.

At the same time, Shoghi Effendi wrote to his Beloved Grandfather, asking where he could study in England or if he was needed in Haifa. On 5 July 1920, 'Abdu'l-Bahá wrote His grandson back, giving His approval for him to study in England, and advising Shoghi Effendi on how to successfully enroll in Oxford.

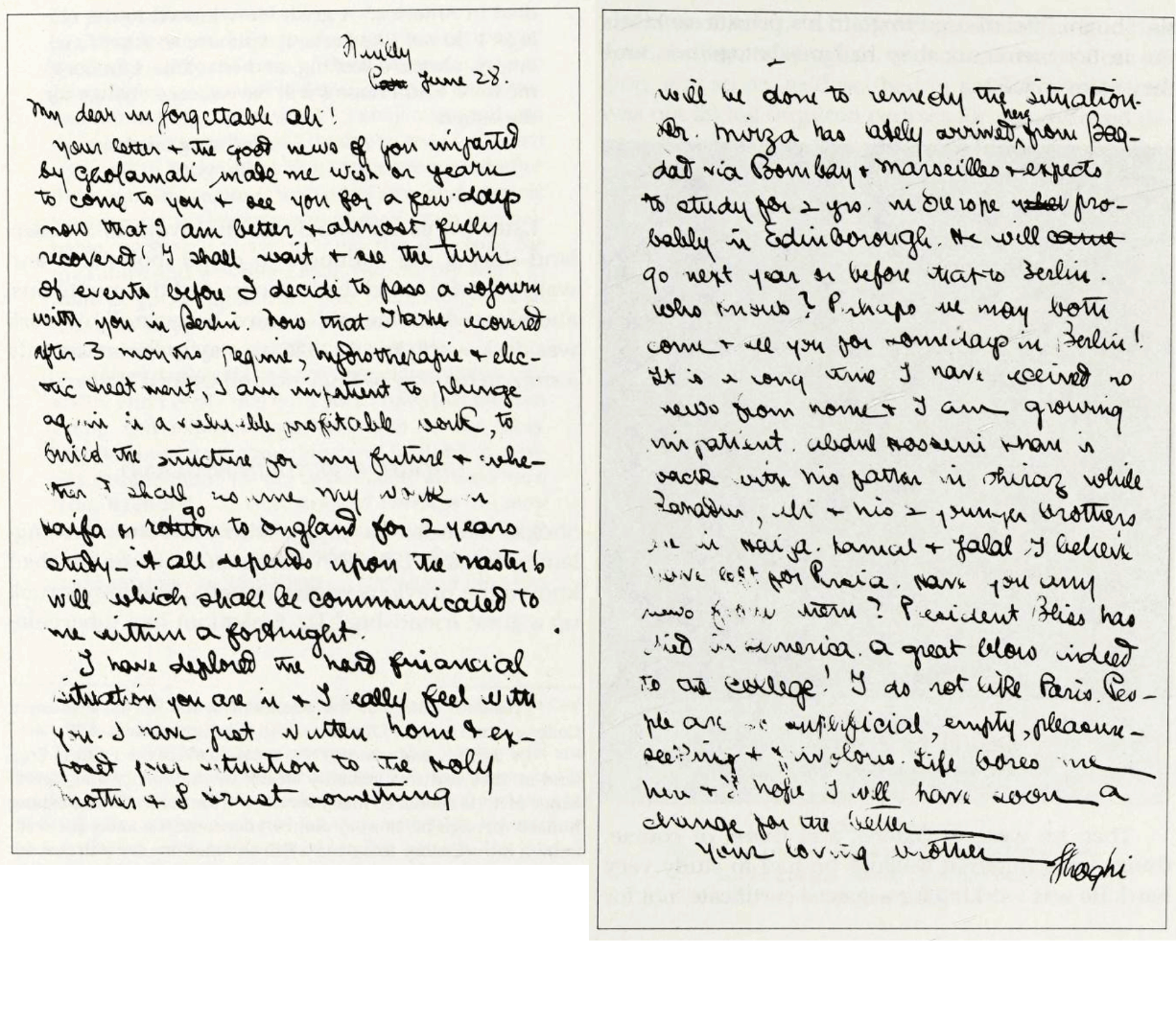

Shoghi Effendi's 28 June 1920 letter to ‘Alí Yazdí. Source: Blessings Beyond Measure, ‘Alí Yazdí, pages 76-77.

One month later, Shoghi Effendi was on the mend, and awaiting instructions from 'Abdu'l-Bahá on what should be his next course of action:

I am better and almost fully recovered! I shall wait and see the turn of events before I decide to pass a sojourn with you in Berlin. Now that I have recovered after three-months regime, hydrotherapy, and electric treatment, I am impatient to plunge again in a valuable, profitable work…

At this point in May 1920, Shoghi Effendi was not sure he would study in Oxford, or, indeed where he would study or even if he would study. His future was a question mark, and he was waiting for the answer to the question to come from his center of guidance, the goal of his life, 'Abdu'l-Bahá. The options he outlined to ‘Alí were: either he would return to Haifa and continue to work as 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s English secretary, or go to England and study for two years. 'Abdu'l-Bahá would make the decision for him in the next two weeks, he said.

Shoghi Effendi was very grieved to learn about ‘Alí Yazdí’s financial problems, saying:

I really feel with you. I have just written home and exposed your situation to the Holy Mother, and I trust something will be done to remedy the situation.

Shoghi Effendi was considering traveling to Berlin to visit ‘Alí Yazdí, but he was waiting on 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s word first. In other news, he informed ‘Alí that Dr. Bliss, President of Syrian Protestant College during their studies in Beirut, had passed away in the United States—he died from tuberculosis on 2 May 1920 in Saranac Lake, New York.

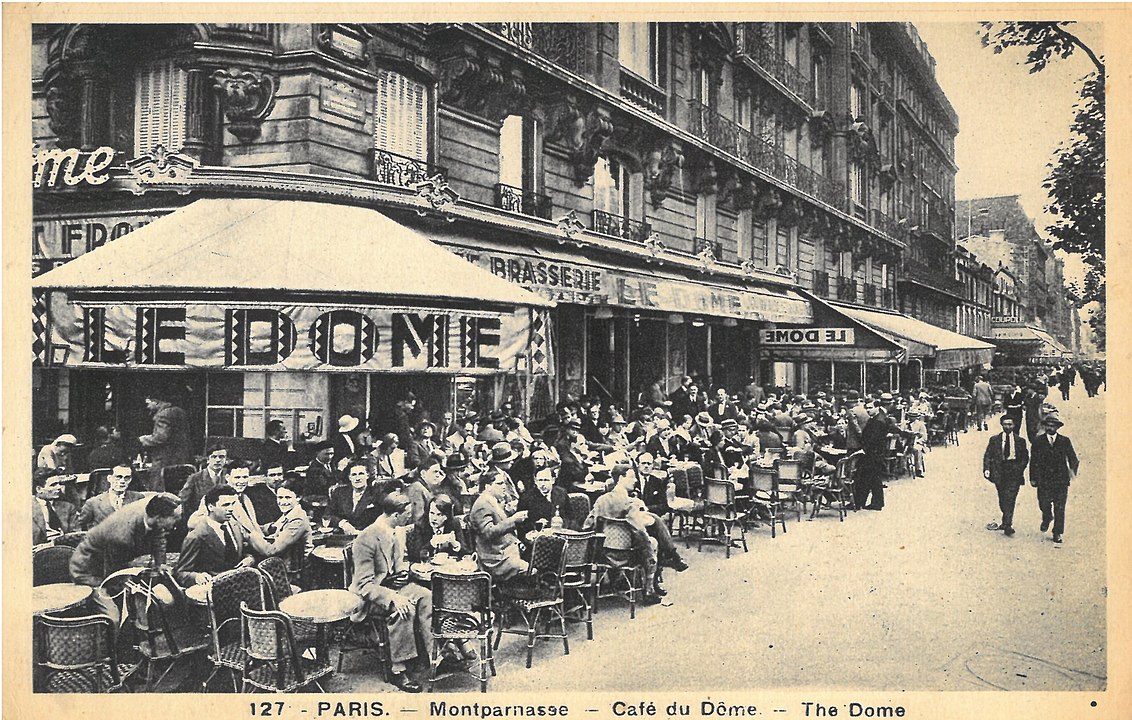

Le Dôme, the iconic Parisian café in the early part of the 20th century. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

There is a striking similarity in 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s and Shoghi Effendi’s experiences and comments about Paris just 7 years apart. Both 'Abdu'l-Bahá and Shoghi Effendi were profoundly dismayed by the materialism in Paris.

Here are 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s words about Parisians in 1913:

The Parisian people are submerged in the sea of materialism. They are intoxicated with the wine of desire and selfish appetites. They think these material objects are permanent.

And below are Shoghi Effendi’s words regarding Paris and Parisians in 1920, just 7 years later:

I do not like Paris. People are so superficial, empty, pleasure-seeking, and frivolous. Life bores me here, and I hope I will have soon a change for the better.

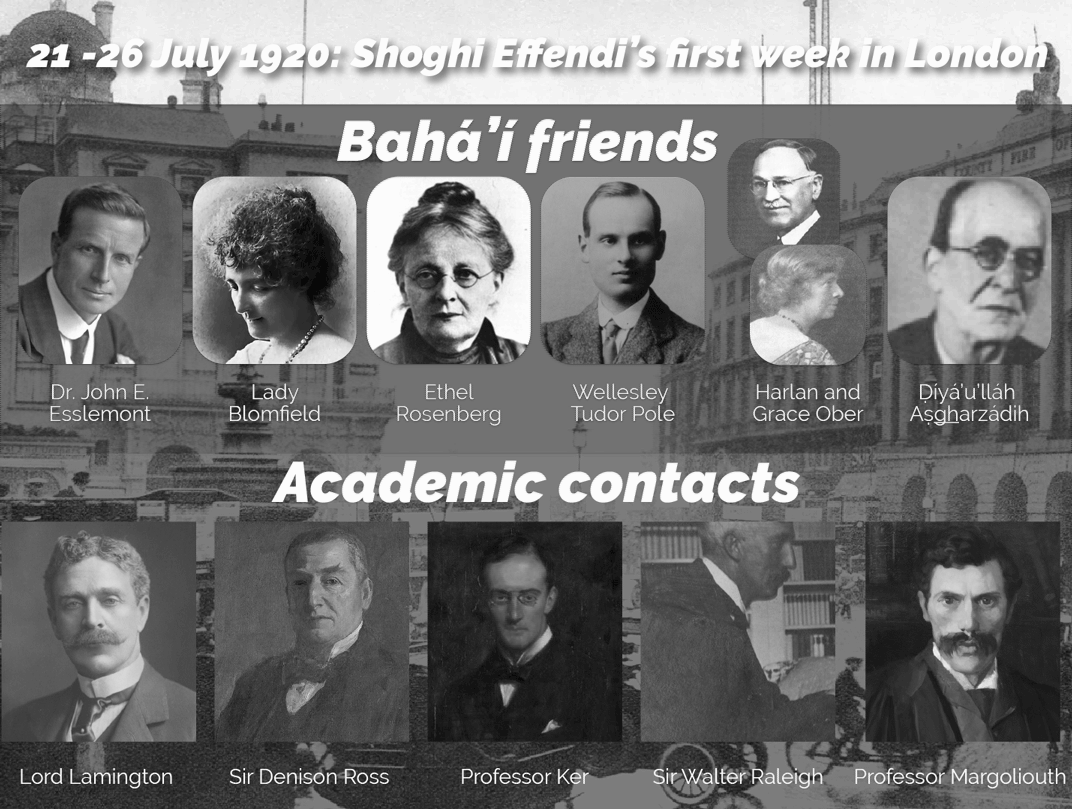

Shoghi Effendi arrived in London on 21 July 1920, and was warmly and affectionately welcomed by the many devoted friends of 'Abdu'l-Bahá in Lindsay Hall in Notting Hill Gate. Dr. John E. Esslemont was there, as well as Harlan and Grace Ober, two visiting American Bahá'ís.

The next day, on 22 July, Dr. Esslemont called on Shoghi Effendi at his hotel and they went to Miss Grand's home where the Obers were staying. The day after that, on 23 July 1920, Dr. Esslemont met Shoghi Effendi at the home of Ethel Rosenberg and they returned to Miss Grand’s home, where they introduced 17 people to the Faith. Dr. Esslemont returned to Bournemouth for a few days and returned on 26 July 1920, and together, paid a visit to Elizabeth Herrick, another Bahá'í in London, who had hoped to organize a Unity Feast.

Shoghi Effendi in a suit, with a coat in his hand and a suitcase, looking like he is traveling. Source: Reddit.

Shoghi Effendi had arrived in England with Tablets 'Abdu'l-Bahá had revealed for Lady Blomfield, Lord Lamington and Major Tudor Pole. Shoghi Effendi was also in possession of introductions and recommendations from Sir Denison Ross, and Professor Ker to Sir Walter Raleigh, a professor and lecturer on English literature at Oxford, and to Professor Margoliouth, a remarkable Orientalist and scholar of Arabic whom Shoghi Effendi admired greatly.

London—and then England—was a wonderful experience for Shoghi Effendi compared to Paris, and he loved the English Bahá'ís, so many of them utterly devoted to his beloved Grandfather, like Lady Blomfield, Ethel Rosenberg, Major Tudor Pole, Ḍíyá’u’lláh Aṣgharzádih—a longtime Persian pioneer to England—and Dr. John Esslemont, whom Shoghi Effendi had met in the winter of 1919 in Haifa.

While he was still in London, Shoghi Effendi received a letter back from Professor Margoliouth saying that he would do everything in his power to be of assistance to a relative of 'Abdu'l-Bahá.

Very shortly after 26 July 1920, Shoghi Effendi left London for Oxford.

When Shoghi Effendi arrived in Oxford around 26 July 1920, he checked into the Randolph hotel and began meeting with professors and searching out a tutor. Although it was still the summer holiday, Shoghi Effendi wasted no time and immediately began working with his tutor, who was a professor of philosophy at Balliol.

Sometime in August, Shoghi Effendi met with Lord Lamington.

There was no vacancy at Balliol college during Shoghi Effendi’s first tier, so he couldn’t register, but that did not stop him from attending class every day, and pursuing work with his tutors. He left the Randolph Hotel and rented a room at 45, Broad Street.

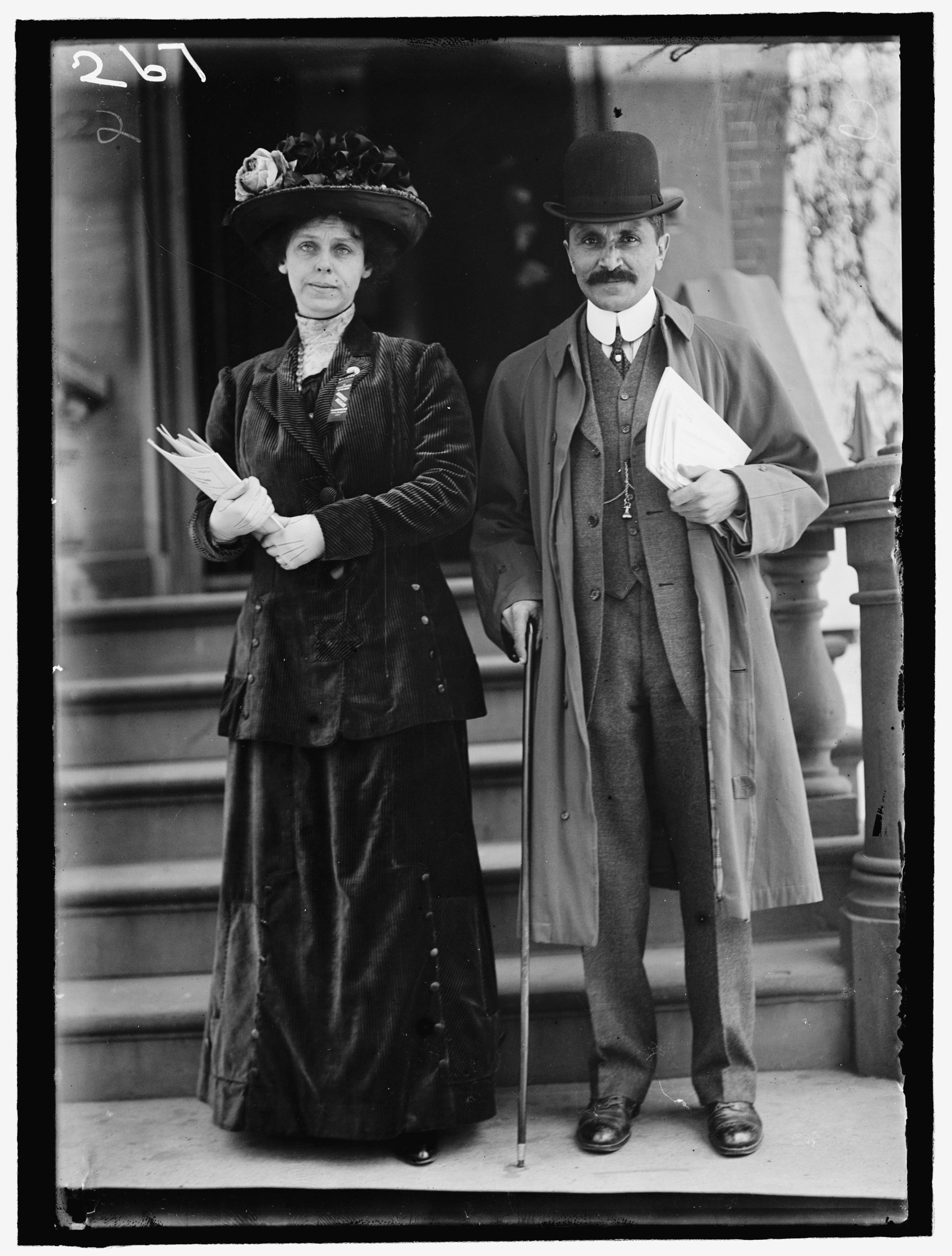

Florence Breed Khán with ‘Alí Qulí Khán in 1911. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

A week after his arrival, on 28 July 1920, Shoghi Effendi wrote a letter to Florence Khan in Paris that shows he was already extremely busy and productive, but also stimulated and excited:

I have been fearfully busy since I stepped on British soil and so far the progress of my work has been admirable.

After arriving in Oxford, and settling in the Randolph Hotel, Shoghi Effendi had the opportunity to meet and speak with Professor Margoliouth, as well as other eminent men and graduates of Oxford such as Lord Grey, Earl Curzon, Lord Milner, Mr. Asquith, Swinburne and Sir Herbert Samuel. To one and all, Shoghi Effendi clarified certain points regarding the Bahá'í Faith on which they had been uncertain and confused.

In ending his letter to Florence Khan, Shoghi Effendi makes a special, meaningful request:

Do pray for me, as I have requested you on the eve of my departure, that in this great intellectual center I may attain my object and achieve my end.

On 8 August 1920, Lord Lamington wrote to 'Abdu'l-Bahá with news of Shoghi Effendi and acknowledgement of having received the Tablet 'Abdu'l-Bahá revealed for him and entrusted to Shoghi Effendi to deliver:

My dear Friend

I was glad to get your letter at the hands of Shoghi Rabbani and to know from him that you are well. He himself seemed in good health, and I was again impressed by his intelligence and open honest manner. I hope he will manage to get the training he seeks at Oxford. He came to the House of Lords two or three days, but none of the occasions were I fear of any great interest.

It is very touching to see the eagerness of Shoghi Effendi to experience and observe the sessions of the House of Lords and the House of Commons. An abiding and insatiable curiosity was perhaps one of Shoghi Effendi’s most enduring and distinctive traits.

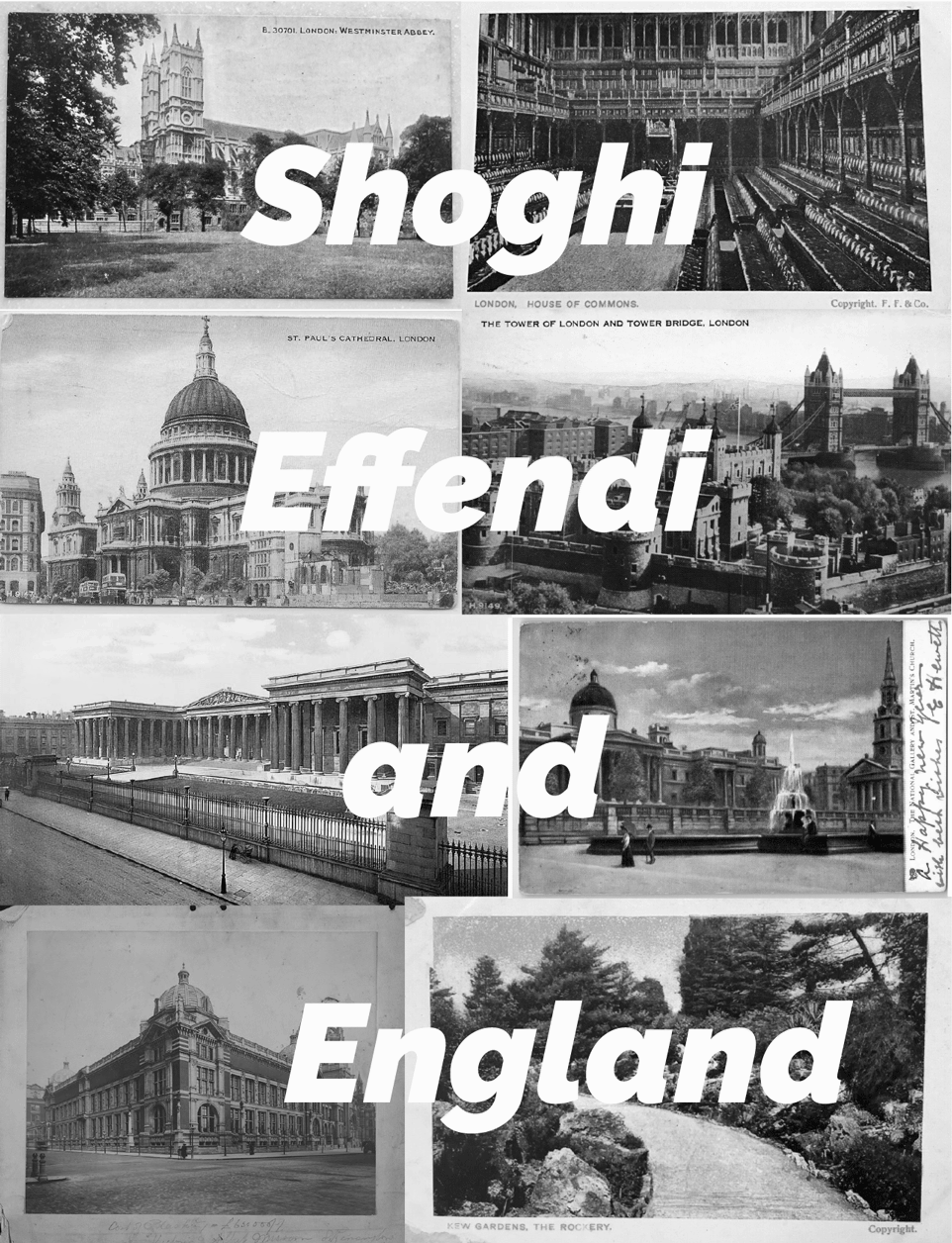

Vintage postcard collage of the sights in London Shoghi Effendi became familiar with: Westminster Abbey, the House of Commons, St Paul's Cathedral, the Tower of London, the British Museum, the National Gallery, the Victoria and Albert Museum, and Kew Gardens.

During his 18 months in England, Shoghi Effendi forged unforgettable memories, that would stay in his heart for the rest of his life. He became deeply familiar with iconic places in London for example, Westminster Abbey, the House of Commons, St Paul's Cathedral, the Tower of London, the British Museum, the National Gallery, the Victoria and Albert Museum, the City, and Kew Gardens, and the associations he formed with these places during his student days, he would later share with his wife, Rúḥíyyih Khánum.

Shoghi Effendi had very modest means during his studies at Oxford, and was very careful with his allowance, going so far as to purchase an electric iron and press his clothes himself. Despite his modest means, Shoghi Effendi no doubt discovered as much of England as he could, and the experience must have thrilled and impressed him.

Shoghi Effendi would never forget his student days in England.

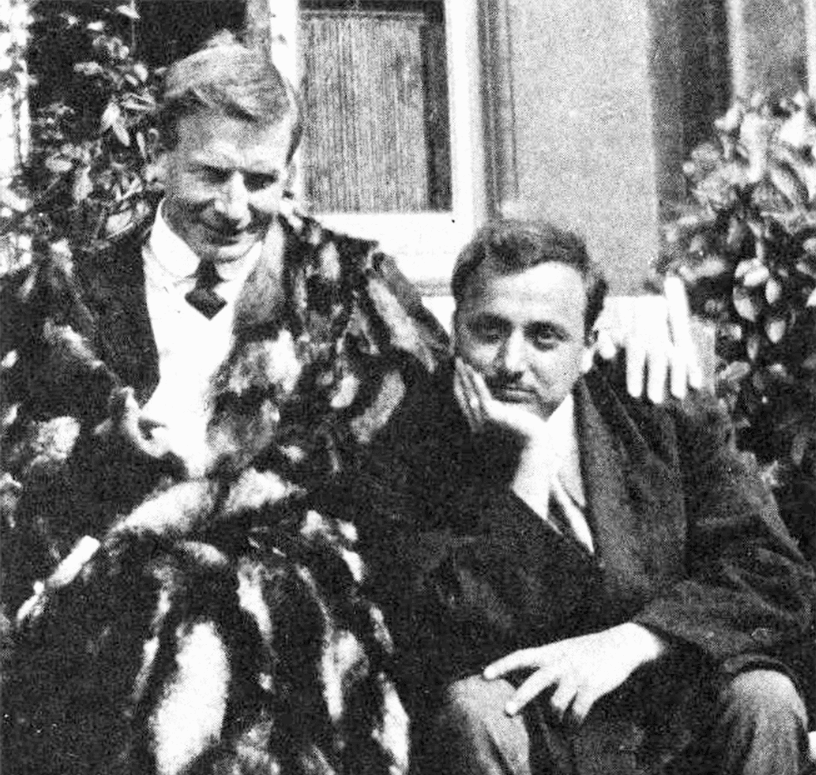

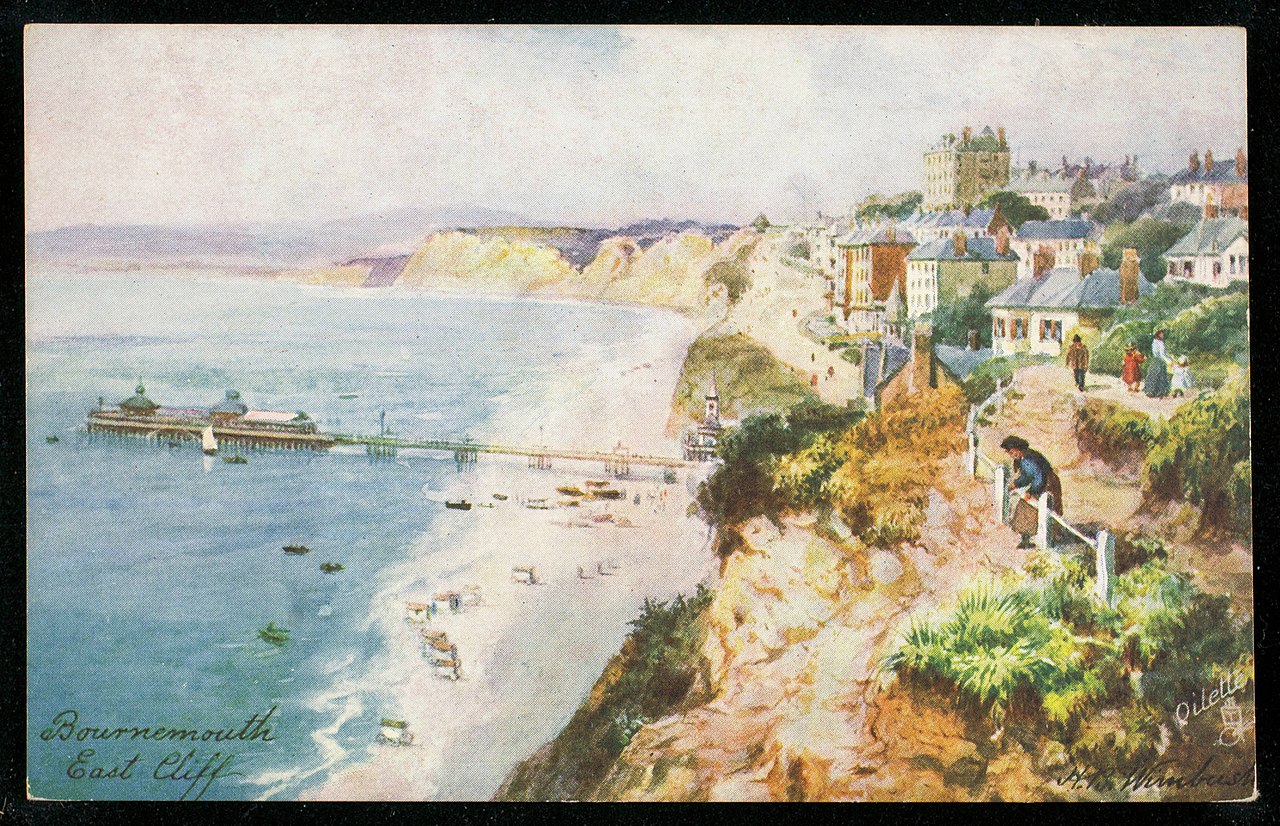

Shoghi Effendi visiting Dr. Esslemont in Bournemouth. Source: Blessings Beyond Measure, page 78.

After a few intense and concentrated weeks of study at Oxford, Shoghi Effendi finally accepted Dr. John E. Esslemont’s invitation and went to visit him in Bournemouth at his private sanatorium for a few days.

Dr. John E. Esslemont was the resident medical officer of the Home Sanatorium for the treatment of tuberculosis in the beautiful coastal resort town of Bournemouth on the south coast of England in South East Dorset.

The day after Shoghi Effendi arrived in Bournemouth, his sister Rúhangíz, about to begin her studies in Scotland, joined him, and they were both joined later by a Persian Bahá'í named Aflátún. Shoghi Effendi’s first term at Oxford was starting in two weeks.

The photograph above shows Shoghi Effendi and Dr. Esslemont sitting close to each other on the steps in front of the sanatorium, and Shoghi Effendi would later recall his lovely visits to Bournemouth in a letter, expressing what they meant to him:

I shall ever recall the happy and restful days I spent at Bournemouth in the company of our departed friend John Esslemont and I will not forget the pleasant hours we spent together while taking our meals in the sanatorium.

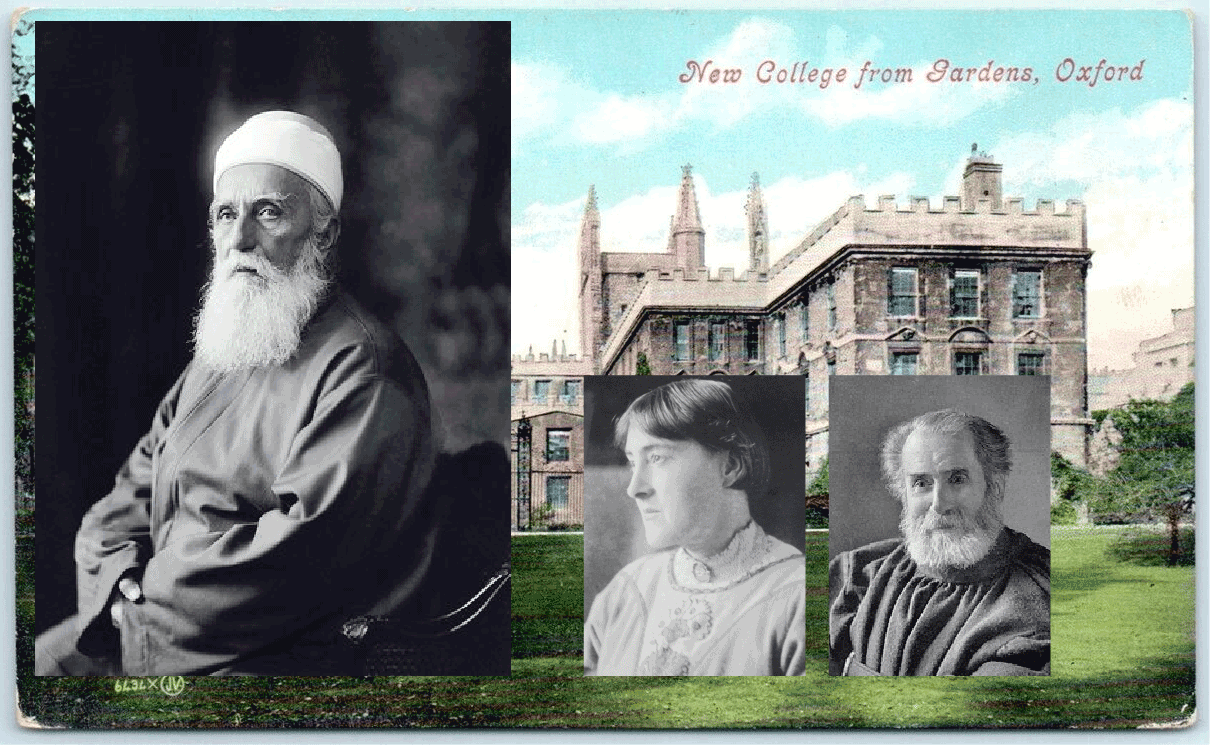

“'Abdu'l-Bahá in Oxford”: A photograph of 'Abdu'l-Bahá from 1912, and photos of Elizabeth Gibson Cheyne and Thomas Kelly Cheyne in 1911, one and two years before they all met in Oxford. 'Abdu'l-Bahá was deeply touched by the loving and devoted couple. Source: Judy Greenway: From the Wilderness to the Beloved City: Elizabeth Gibson Cheyne.

'Abdu'l-Bahá had blessed Oxford with His footsteps when He visited the town on Tuesday 31 December 1912. Abdu’l-Bahá and His entourage left London at 10:50 in the morning and arrived in Oxford at 11:35.

Upon arriving, 'Abdu'l-Bahá had gone straight to “South Elms”, a sprawling property at 17 Parks Road, to spend a few hours with Thomas Kelly Cheyne and his devoted wife Elizabeth Gibson Cheyne.

Thomas Kelly Cheyne, at 72 years old, was the foremost Western intellectual during 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s ministry. He was a highly-respected English theologian and Biblical critic with a Doctorate in Literature from Oxford University and became a Bahá'í five months before 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s visit through Ethel Rosenberg, the first British Bahá'í.

Cheyne, at this point, had suffered from debilitating health for most of his life, lost sight in one eye in 1883, and for five years before 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s visit, he had suffered progressive paralysis in his hands and feet, nevertheless publishing five books in this time period. As the paralysis progressed, it affected his throat, so few people could understand what he said, unless his loving wife Elizabeth translated for him.

When ‘Abdu’l-Bahá arrived, He lovingly embraced T.K. Cheyne and praised his courageous steadfastness in his life’s work, despite declining health and increasing physical weakness, saying that the light of the mind and spirit shone through with radiant persistence through those veiling clouds.

While they spoke, Cheyne showed 'Abdu'l-Bahá what he had written about the Faith. Cheyne’s attentive attitude and faith so moved the Master that 'Abdu'l-Bahá kissed him several times. In one of His last tablets to him in 1914, 'Abdu'l-Bahá called T.K. Cheyne “my spiritual philosopher.” Cheyne himself, writing to Mr. Craven, a Bahá'í from Manchester on January 31, 1914, said:

Alláh’u’Abhá! Dear Bahá'í brother... Why I am a Bahá'í is a large question, but the perfection of the character of Bahá'u'lláh and 'Abdu'l-Bahá is perhaps the chief reason...

'Abdu'l-Bahá then told T.K. Cheyne a deeply prophetic story about another author, also affected in the throat, whose spirit also knew no defeat. It was the story of ʿAṭṭár of Nishapur, a Persian poet and Súfi theoretician from the 12th-13th century who had an immense and lasting influence on Persian poetry and Sufism, and the author of the vastly influential work The Conference of the Birds".

'Abdu'l-Bahá's story was fascinating. One day, ʿAṭṭár was traveling through the desert when he was set upon by thieves who robbed him and injured his throat. Attar survived and reached the city, where doctors attended to him. But the injury to his throat had rendered ʿAṭṭár mute. After the attack, he lived one more year, during which he wrote the book that survived his entire legacy. The book in question was most probably Tazkirat al-Awliyá or "Biographies of the Saints," his only surviving prose work published shortly before his death.

At the time 'Abdu'l-Bahá recounted this story, T.K. Cheyne was by this time also nearly mute, and, though he did not know it, only had two years left to live. During these two years, he, too, would write the one book that would outlive his legacy, his History of the Bahá’í Faith: The Reconciliation of Races and Religions. In the 1914 preface to this book, T.K. Cheyne wrote a touching sentence:

'Abdu'l-Bahá (when in Oxford) graciously gave me a new name [Rúḥání (Spiritual)]. Evidently he thought that my work was not entirely done and would have me ever looking for help to the Spirit, whose “strength is made perfect in weakness."

Elizabeth Gibson Cheyne and Thomas Kelly Cheyne married in 1911, two years before 'Abdu'l-Bahá's visit, when Elizabeth was 42 years old and Thomas, 70. Their marriage was happy, one of equals who shared a passion for feminism, internationalism, universalism, and anti-racism, but they were most deeply bonded in their approach to God and spirituality.

When 'Abdu'l-Bahá came to visit, Elizabeth was at Thomas’ side, interpreting his inaudible answers, caring, devoted, solicitous. Her attitude deeply touched 'Abdu'l-Bahá, who, with tears in His eyes, told Lady Blomfield and Mrs. Thornburgh-Cropper, on the train journey back to London:

She is an angelic woman, an example to all in her unselfish love. Yes, she is a perfect woman. An angel.

Manchester College where 'Abdu'l-Bahá spoke at 3 PM on Tuesday 31 December 1913 in Oxford, from the south side of Chapel Court. Photograph by Matthew Hoser. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

After his moving visit with the Cheynes, 'Abdu'l-Bahá spoke at Manchester College at Oxford University at 3 PM, a speaking engagement which Thomas Kelly Cheyne had arranged himself, for an audience of professors, scholars and ministers.

After a brief introduction, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá gave a masterful address, starting with science as the cause of man’s intellectual progress, which led to an in-depth survey of the powers of perception. 'Abdu'l-Bahá followed this with an example of a lack of perception, namely warfare, and poignantly asked His audience if the fundamental idea of Christianity had not been entirely forgotten, saying that the Balkan War was due to the fundamental basis of religion having been set aside. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá ended on an optimistic note: great universities were working on peace and reconciliation, mankind’s perception was becoming clearer, and His wish was for the audience to work for peace and unity in words and deeds to uproot the tree of warfare.

Unusually, there were no questions when the floor opened. Professors came to shake ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s hand, but it was T.K. Cheyne who was especially impressed. He would later write of 'Abdu'l-Bahá:

He was a complete man. No one in our time, so far as my observation reaches, lived the perfect life like 'Abdu'l-Bahá.

Aerial panorama of the many colleges at Oxford. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Shoghi Effendi began studying under a private tutor in August 1920, two months before the start of the term. In his first term in Oxford, Shoghi Effendi was not yet admitted to Balliol and was living off-campus, attending lectures while matriculated in St. Catherine’s college, the Delegacy for Non-Collegiate Students, meaning students not yet admitted to one of Oxford’s Colleges.

By October 1920, Shoghi Effendi was intensely immersed, heart and soul, in his preparations for entrance at Balliol College and studying very hard, taking specialized college, to obtain the certificate he needed to officially matriculate at Oxford.

The Bodleian Library is the main research library of the University of Oxford, sprawling over no less than five buildings, and is one of the oldest libraries in Europe, tracing its origins back to the 14th century, and Shoghi Effendi spent many hours in its hallowed halls. This photograph is of the interior of the Duke Humfrey's Library, the oldest reading room in the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford. The Humfrey's Library houses collections of maps, music, Western manuscripts, and theology and art materials. It is the main reading room for researchers of codicology, bibliography and local history, as well as it containing the University Archives and the Conservative Party Archive. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

In his letter to ‘Alí Yazdí dated 5 October 1920, Shoghi Effendi finds the time to worry about ‘Alí’s financial troubles:

I wished, dear ‘Alí, to have had enough money at my disposal to share it with you! I immediately wrote to Mrs. George and exposed the case fully. I hope you will soon and easily sail. I am so grieved at the sudden turn of events and the complications and cost of travel have only marred the brightness caused by the knowledge that some financial help has been finally extended.

Shoghi Effendi had written a letter to his family in Haifa about ‘Alí Yazdí’s situation and he stated he “really wondered and got even angry at the delay and silence following my letter which I sent home concerning you.”

Although Shoghi Effendi himself was not subject to worries about money, he assured ‘Alí he was subject to other kinds of suffering, “various physical, intellectual, and social drawbacks and preoccupations” and confided in his best friend the extent of his emotional pain:

Do you believe me when I say that I, the grandson of the Master, have been victim of painful experiences, sometimes of bitter disappointments, and always of constant anxieties—all justified—for my immediate work and future? If you have spent of late painful and trying times, my share of these troubled hours is by no means much less and my burden much lighter.

In this same letter of 5 October 1920, the young Shoghi Effendi strikingly expresses himself with the eloquence of the future Guardian as he lays out for ‘Alí Yazdí the herculean task that lies ahead of him, and the pressures he feels to succeed in order to fulfill his destiny of service:

My field of study is so vast, I have to acquire, master, and digest so many facts, courses, and books—all essential, all indispensable to my future career in the Cause. The very extent of this immense field is enough to discourage, excite, and overwhelm such a young and inexperienced beginner as myself. Think of the vast field of Economics; of social conditions and problems; of the various religions of the past, their histories and their principles and their force; the acquisition of a sound and literary ability in English to be served for translation purposes; the mastery of public speaking so essential to me, all these and a dozen more—all to be sought, acquired, and digested!

The last line of his letter reads like the motto of the future Guardian of the Cause:

Prayer, faith, perseverance and effort will alone do it.

Shoghi Effendi’s sister Rúhangiz began studying at university in Scotland around the time Shoghi Effendi started at Oxford.

The great quadrangle in front of the 1,000-year old Christ Church in Oxford. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Shoghi Effendi wrote down the schedule of his classes for his Michaelmas term in one of his of his notebooks at that time. His first classes were Political Science, Social and Political Problems, Social and Industrial Questions, Political Economy, English Economic History since 1668, Logic, The eastern Question, and Relations of Capital and Labour.

In addition to his schoolwork, Shoghi Effendi helped Dr. John E. Esslemont with transliterating Persian words for Bahá’u’lláh and the New Era, he played football and participated in student debates. A week after starting classes, on 23 October 1920, Shoghi Effendi officially matriculated in the Non-Collegiate Delegacy.

Oxford would be Shoghi Effendi’s home for over a year. He walked the streets to the world-famous Bodleian library, one of the oldest libraries in the world, walked along the placid Thames River, and the sights he saw were ancient, like the thousand-year-old Christ Church, at once a cathedral and a college with a vast kitchen, and an intricate lace of Gothic arches.

While he was studying, Shoghi Effendi used his spare time to translate the Hidden Words and the Tablet of Visitation for Bahá'u'lláh. He was very neat, and bought himself an iron with which he pressed his clothes.

Shoghi Effendi’s four terms at Oxford, his last Michaelmas term cut short by the Ascension of 'Abdu'l-Bahá. Background photograph of the world-famous Bridge of Sighs in Oxford by Václav Jirousek. Source: Flickr (license CC0 Public Domain Dedication).

Like many other universities and educational institutions, Oxford University organizes its year around terms, each of which begins on a Sunday, and the names of the terms originated in the legal system during medieval times.

Oxford's Michaelmas Term

The Michaelmas Term is the first academic term of the year from October to December. The name “Michaelmas” comes from the Feast of St Michael and All Angels, which falls on 29 September.

Oxford's Hilary Term

The Hilary Term is the second academic term, from January to March. The name “Hilary” comes from the feast day of St. Hilary of Poitiers, which falls close to the start of this term, on 14 January. St. Hilary of Poitiers was a Bishop and Doctor of the Church.

Oxford's Trinity Term

The Trinity Term is the third and final term of the academic year, from April to June. It’s named after Trinity Sunday, which falls eight weeks after Easter, in May or June, a date which changes each year. Trinity Sunday celebrates the Christian doctrine of the Trinity (three persons of God: The Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit).

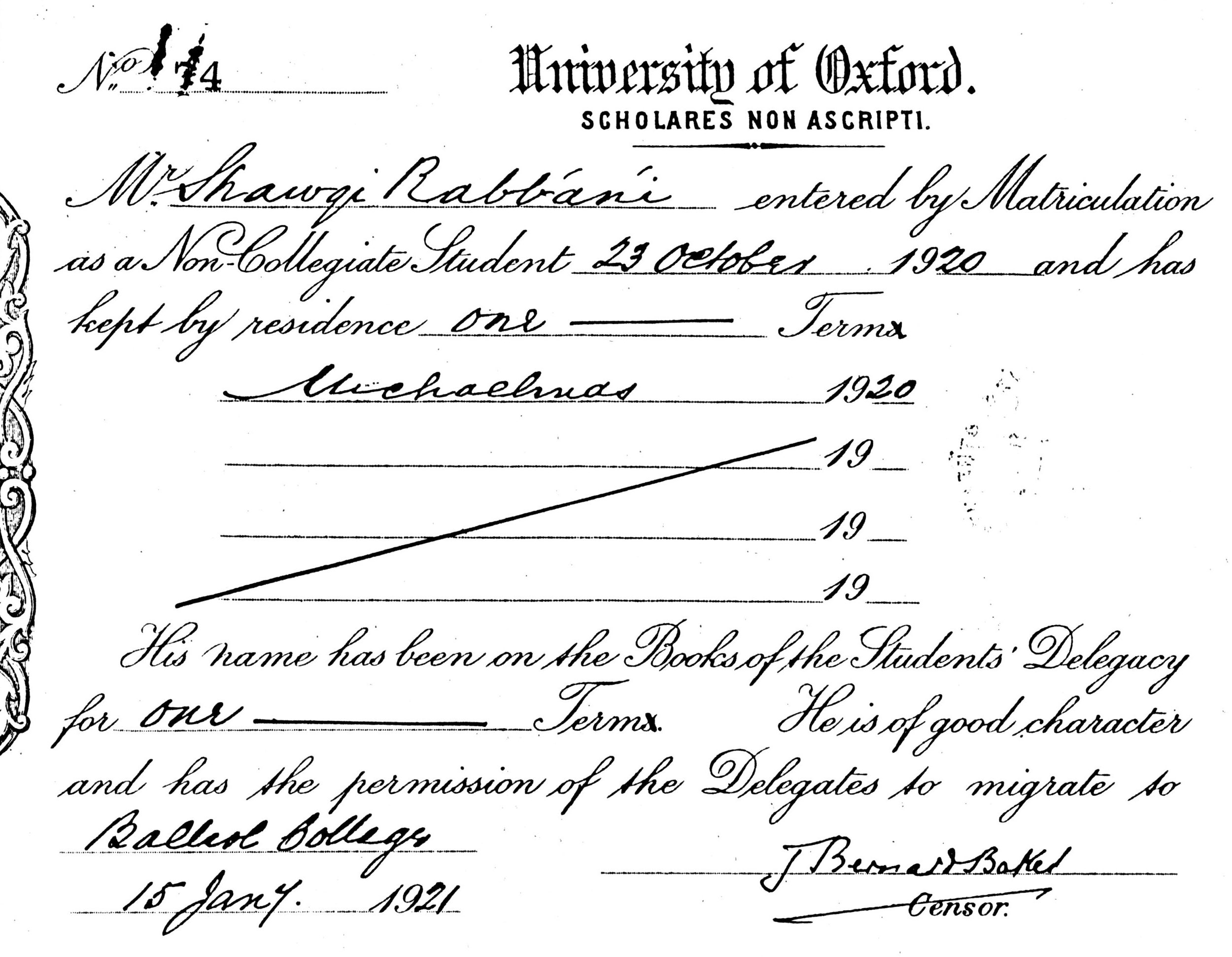

The certificate of matriculation reads:

University of Oxford

SCHOLARES NON ASCRIPTI (Latin for SCHOOLS NOT REGISTERED)Mr. Shawqi Rabbání entered by Matriculation as a Non-Collegiate Student 23 October 1920 and has kept by residence one term: Michaelmas 1920. His name has been on the Books of the Students’ Delegacy for one term. He is of good character and has the permission of the Delegates to migrate to Balliol College 15 January 1921.

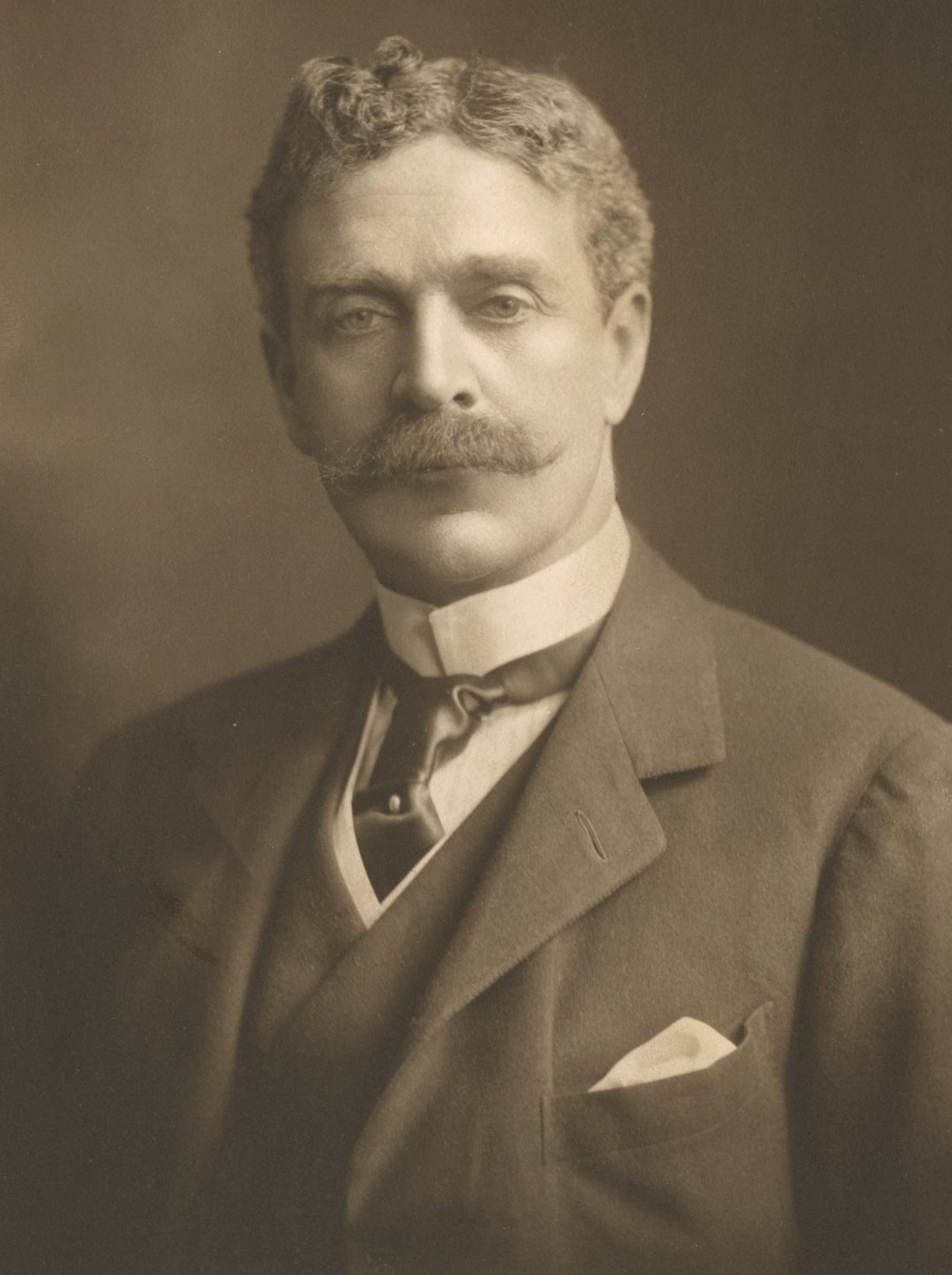

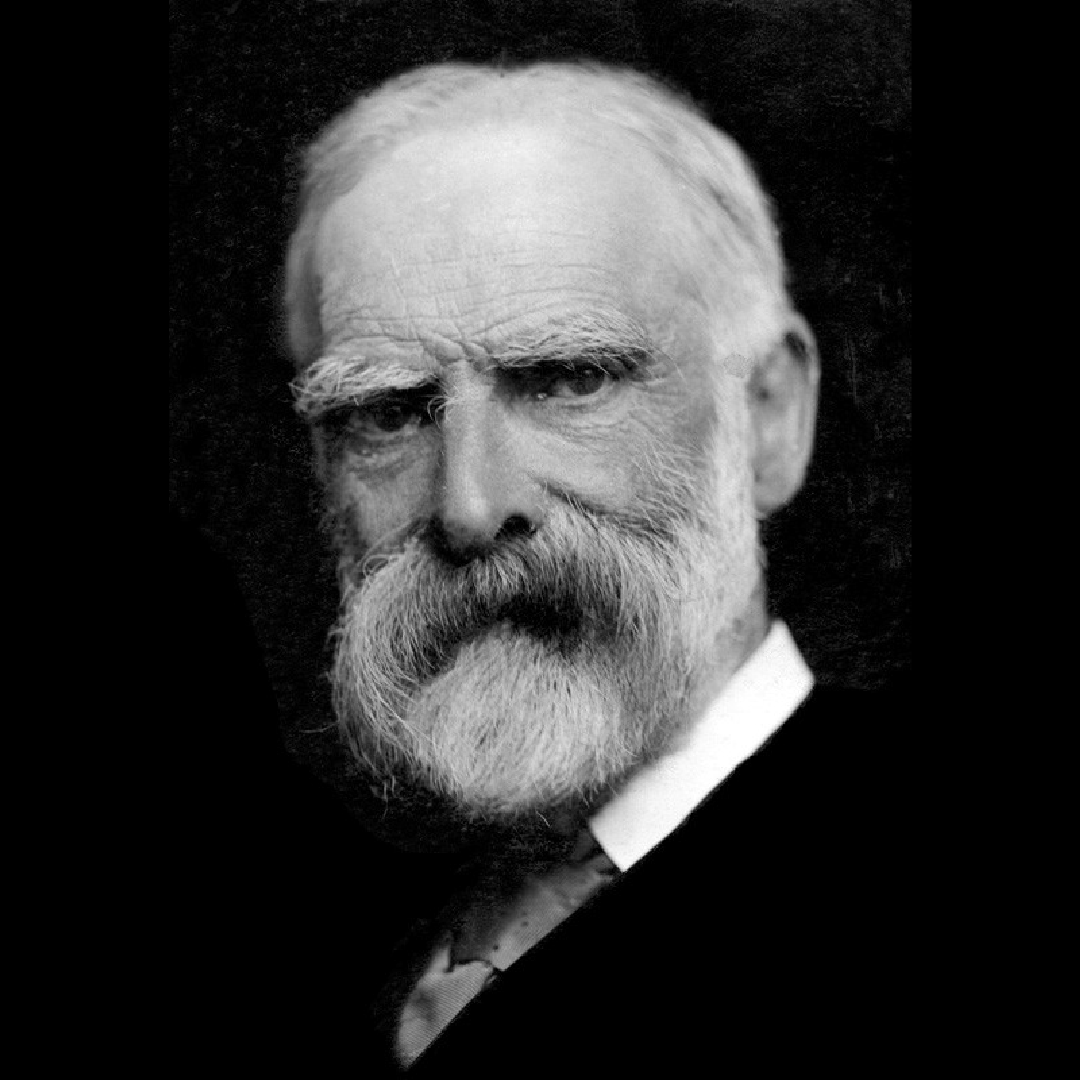

James Bryce, 1st Viscount Bryce. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Around mid to late October 1920, ‘Alí Yazdí left Germany for the United States. His plan was to enroll at the University of California at Berkley, and he stopped by London, where he wired Shoghi Effendi to inform him they were once again in the same country!

Shoghi Effendi immediately responded to ‘Alí’s telegram:

You don’t mean to tell me you are going to America without coming to see me.

‘Alí wrote Shoghi Effendi a note and Shoghi Effendi responded with a postcard dated 3 November 1920 in which he speaks about the Arabic tradition musáfihih—where two close friends embrace each other touch the right, then the left cheeks:

When I received your telegram, I wondered to what address I should forward my answer. Now that I have been informed I hasten to tell you how glad I would be to meet you, shake hands with you, and perform the ceremony of musáfihih.

In the same postcard, Shoghi Effendi informs ‘Alí Yazdí he is drowning under the hectic schedule of his lectures and courses, and sometimes feels depressed, but he is very much looking forward to hosting his dear friend, even though he doesn’t know how ‘Alí Yazdí managed to afford his trip.

Shoghi Effendi’s postcard was sent on Wednesday 3 November and he tells ‘Alí that on Thursday 4 November and Friday 5 November there will be a brilliant debate address by James Bryce.

It is no wonder that Shoghi Effendi was looking forward to James Bryce’s lecture. James Bryce, 1st Viscount Bryce, was a British academic, lawyer, historian, and Liberal politician. He was extremely influential in matters of law, politics, and history and at the time he gave his lecture at Oxford, he was the British Ambassador to the United States. He is just one example of the high caliber of speakers which Shoghi Effendi was privileged to hear during his time at Oxford.

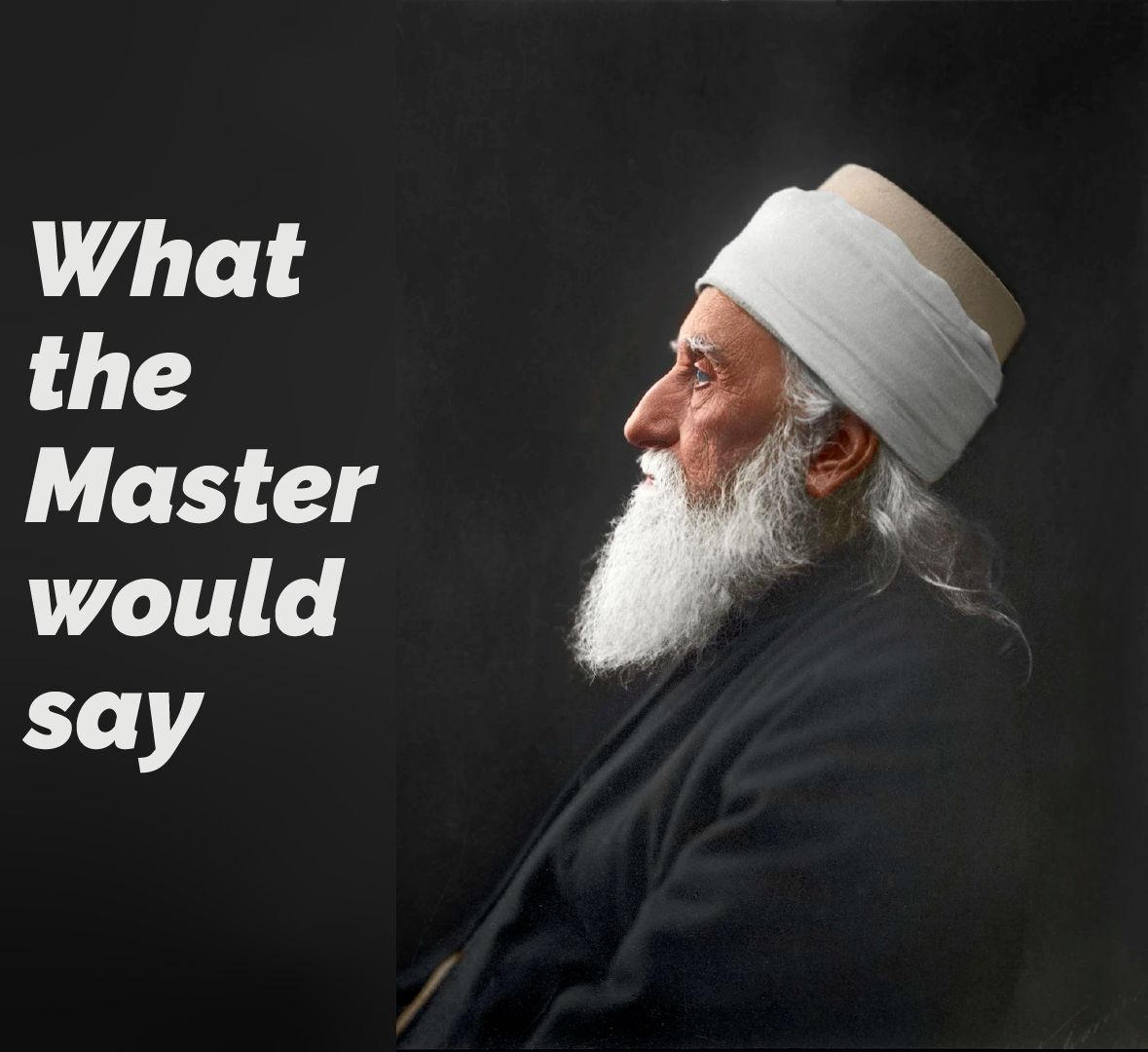

“What the Master would say”: Shoghi Effendi’s motto. Source: Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

‘Alí Yazdí went to visit Shoghi Effendi at Oxford on 3 November 1920 and stayed one night in Shoghi Effendi’s room. Shoghi Effendi took ‘Alí on a full tour of Oxford, showing him the sights and unburdening his heavy soul. They were together again, just as they had been when they were 11 and 13 in Ramleh, Egypt, just as they had been when they were 17 and 19 at Syrian Protestant College in Beirut, just as they had been when they were 20 and 22 in Haifa.

They spent delightful hours speaking about the future of the Faith and their part in its bright destiny, they talked about their own futures and the opportunities that lay ahead of them. Shoghi Effendi confided to ‘Alí Yazdí that he longed to return to Haifa and serve 'Abdu'l-Bahá in any way the Master saw fit. For Shoghi Effendi, his entire life, according to ‘Alí Yazdí, could be distilled, in Shoghi Effendi’s’ own words to a simple five-word motto:

What the Master would say.

Shoghi Effendi was passionate about the great speakers that came to Oxford and wanted ‘Alí Yazdí to attend James Bryce’s talk so they could discuss it afterwards, but ‘Alí Yazdí left on 4 November 1920 and could not stay for the talk.

Two days after ‘Alí Yazdí’s visit to Oxford, he sent Shoghi Effendi a postcard to which Shoghi Effendi responded with a letter dated 6 November, written on the letterhead of the Oxford Union Society, in which he expressed how much he had missed ‘Alí, and wished he could have attended James Bryce’s talks on the evenings of 4 and 5 November. Shoghi Effendi knew how much ‘Alí Yazdí would have enjoyed the lectures, but also because Shoghi Effendi yearned to discuss them together after.

Shoghi Effendi closed the letter to his beloved friend telling him he had already written to his family and asked them to help him financially as he embarked on his studies in California:

I have written to Grandmother about you reminding her of your difficult and strained situation yet your patience and will. I hope that some help might issue by the time you prepare yourself for entrance into college. My best and tenderest wishes be with you always. May we meet again under better circumstances!

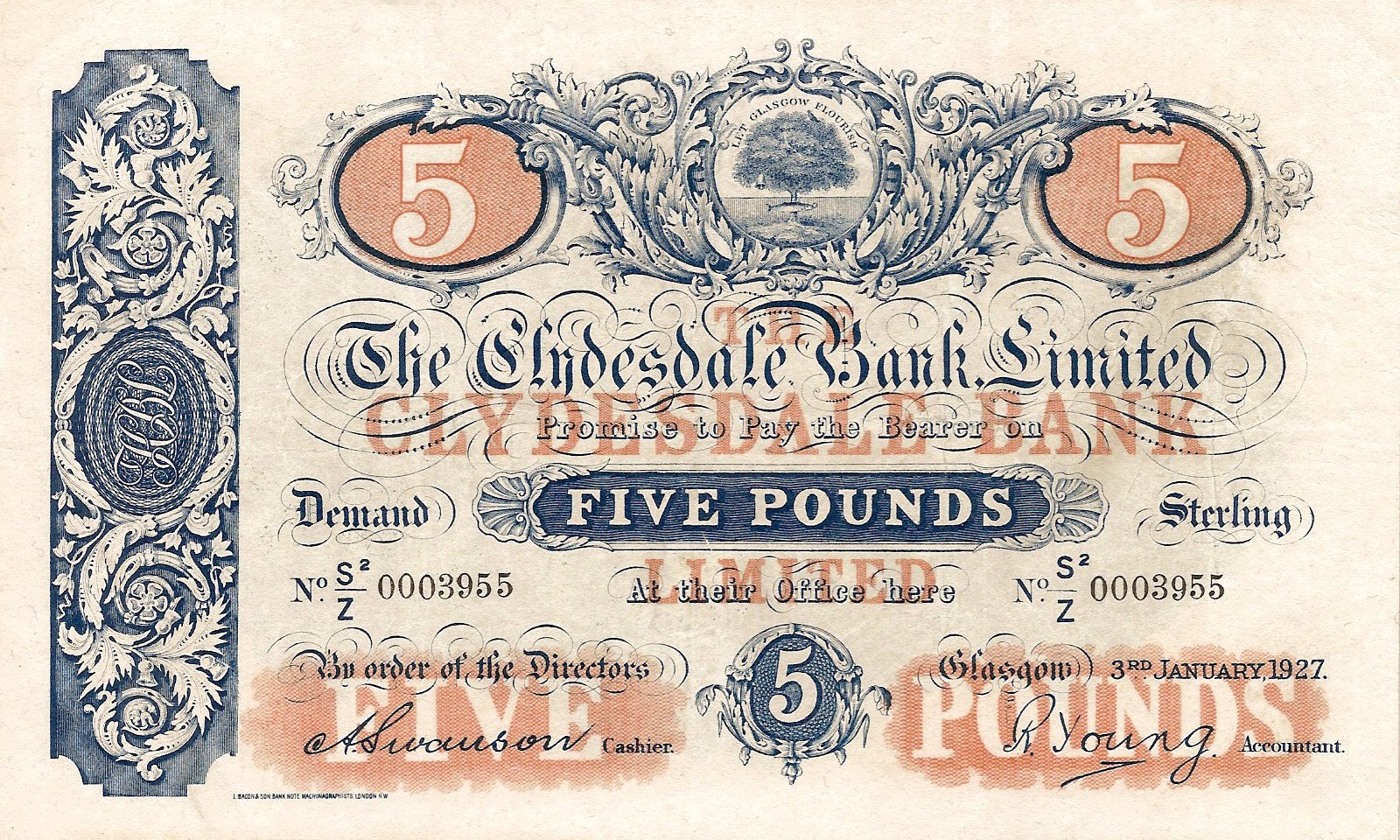

In lieu of a £5 bank note from 1920, here is a £5 British Banknote dated 1927 from Clydesdale Bank and signed Swanson/Young. Source: Pam West British Notes. © Used with permission.

‘Alí Yazdí received another testimony of Shoghi Effendi’s love for him just a few days before he sailed to America, in a letter written on 10 November 1920. In this letter, Shoghi Effendi displays the evidences of his kind and tender heart, his loving kindness, and his generosity towards his beloved friend, at a time when he was himself completely overwhelmed with difficulties of his own:

I really never realized how minute, intense, and urgent were your financial needs. I hasten, therefore, to send you all that I can for the present—namely, five English pounds banknote, which I enclose in this letter. I hope you are staying at Miss Herrick’s. She has some rooms to offer to friends who come to London. If you are not there, do apply. She is so kind.

£5 in 1920 is equivalent to £300 today. It was a very generous gesture. Shoghi Effendi confides his struggles to his loving friend:

My studies and preoccupations are exerting an effect upon me almost as distressing as your own difficulties, Believe me it is so. I don’t know what I shall do at the end.

Shoghi Effendi’s letter ends with immense generosity, absolutely and categorically forbidding ‘Alí Yazdí to even think of repaying him:

For Heaven’s sake think not of sending me back anything. I flatly refuse and decline. Let your mind be at rest.

A dazzling photograph of Edinburgh’s Castle Rock. Source: Pixabay.

During his winter break in 1920, Shoghi Effendi traveled to Edinburgh, Scotland. Shoghi Effendi’s sister Rúhangiz was studying in Scotland, and, more importantly, 'Abdu'l-Bahá had spent several wonderful and very productive days in Edinburgh seven years before, and stayed at the home of a very devoted believer, Mrs. Whyte, who had also hosted the Master in January 1913.

Later, Shoghi Effendi would write to Mrs. Whyte, thanking her for her hospitality and saying:

I shall always remember, with the liveliest and most pleasant recollection your most valuable help to me as well as your generous hospitality during my stay in Oxford...Always your grateful and affectionate friend Shoghi.

Inside the dining hall at Balliol College, Oxford. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Oxford’s academic structure of colleges is worth looking at, to understand what Balliol College represents, where Shoghi Effendi completed the remainder of his studies at Oxford.

In 1920, there was no university ranking system such as we have today. University education in our time is orders of magnitude more prevalent than it was in the second decade of the 20th century. Today, we have universities in the United States, like Harvard, Princeton, Yale, MIT, Stanford, that rival the centuries-old universities of England, but in the 1920s, the two best universities in the world were essentially Oxford and Cambridge.

Oxford has a system of colleges, unique in all the world’s higher education institutions. The university has 43 colleges (38 in Shoghi Effendi’s time), each one of them a small, multidisciplinary community, with its own students, academic and administrative staff, accommodations, library, cafeteria, social events, sports, and its very own, distinctive character and history, and each is governed by a charter, an elected Head of House, and a governing body of Fellows.

Oxford colleges provide students with support, facilities, and membership in a friendly and stimulating academic community. Bonds between students in the same college are deep and intimate, they live, study, eat, and play together, and often debate and discuss together. An Oxford college is an immediate community of friends.

Shoghi Effendi was admitted into Balliol college in January 1921, after the winter break following his first non-collegiate term.

Balliol is one of the oldest, largest, and most centrally-located of all the Oxford colleges, founded in 1263 by John I de Balliol. It is the oldest college in the English-speaking world, and its members boast 12 Nobel Prize laureates.

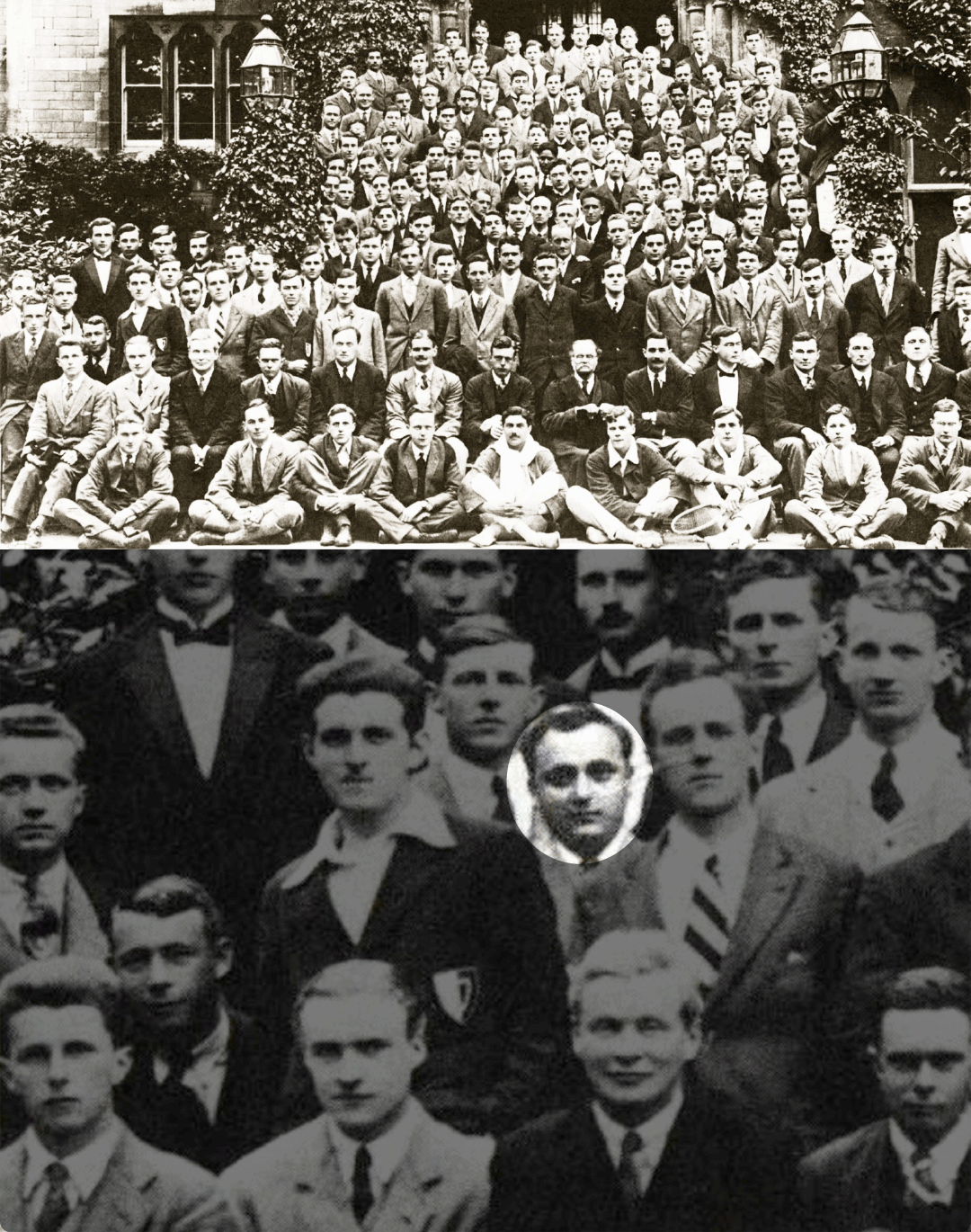

The class of 1920, Balliol College, Oxford. Shoghi Effendi is standing behind the third man in the second row, counting from left to right (in between the young man with a sports jacket and the one with a striped tie) (The Bahá’í World 1954-1963). Source: Bahá'í Points of Interest.

For his second term, from January to March 1921, Shoghi Effendi was officially admitted into Balliol college and moved his residence to Magdalen College, which was very close to Balliol College, only about 800 meters, Many years later, Shoghi Effendi would bring his wife, Amatu’l-Bahá Rúḥíyyih Khánum to Oxford and show her its beautiful surroundings.

Every day during his studies, Shoghi Effendi, wearing the mandatory black gown of an Oxford student, would cross the quad to attend his classes.

Shoghi Effendi’s quarters at Balliol included a bedroom and a living room in a stately edifice dating from the 12th century. Shoghi Effendi likely took his breakfast, lunch and dinner in the dining hall at Balliol,

Shoghi Effendi was so busy with his studies in Oxford, and with that, the University had strict regulations, which meant that he was usually only free on Sundays, and that was when most of his visitors would have to come see him. His hobbies at the time seem to have been participating in a debating society and playing football and tennis.

Shoghi Effendi was intensely focused on his goal of perfecting his translation skills, and during this term, he completed his first translation of the Persian Hidden Words, and one of the Tablets of Visitation.

He also translated some of 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s Tablets and showed his long-range thinking when expressing the hope that the Súriy-i-Haykal and the Summons of the Lord of Hosts would eventually be translated in the most eloquent and majestic English.

Already in Oxford, Shoghi Effendi was writing summaries of the history of the Faith from its inception, describing the extraordinary propagation of the Faith throughout the world in the Ministry of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, analyzing the impact of the Báb’s message on Persian society, and on the stages of Bahá'u'lláh’s proclamation to the world.

In February 1921, Shoghi Effendi gave an address to the Oxford University Asiatic Society on the history and principles of the Bahá'í Faith.

Shoghi Effendi at the time he was studying in Oxford. Source: Brilliant Star Magazine.

From March to April 1921, during vacation, Shoghi Effendi traveled to Scotland to visit his sister Rúhangiz, then Sussex and spent time playing tennis, which was his favorite sport. During this short vacation, Shoghi Effendi continued translating several prayers and Tablets.

During his spring vacation in 1921, Shoghi Effendi first visited his sister Rúhangiz, who was studying in Scotland, then traveled to Sussex to visit his dear friend, Dr Esslemont at his private sanatorium in Bournemouth, following his Grandfather’s clear instructions to rest.

Shoghi Effendi loved Devon, and would always remember how good the thick slices of brown bread, raspberry jam and Devonshire cream had tasted to him.

Shoghi Effendi spent nine full weeks at Oxford for the duration of his Trinity term, from 28 April to 23 June 1921.

Shoghi Effendi began making arrangements early in the term to hire a competent private tutor to work with during the long summer vacation, in order to not waste those precious months, and asked Ethel Rosenburg and Mary Thornburgh-Cropper to help him secure Professor Reynold Nicholson as his tutor. Professor Nicholson was professor of Persian and Arabic at Cambridge and well-known known for his translation of the Persian poet Rumi into English.

The debate chamber of the Oxford Union Society. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Shoghi Effendi was focused on his studies, but there was another aspect of university life that held great appeal for Shoghi Effendi was his interest in the outstanding speakers who gave talks at the Oxford Union, but he also presented papers on the Faith—most likely at the Lotus Club—in April 1921.

Despite his busy schedule, Shoghi Effendi found time to closely associate with the British Bahá'í community and participate in some of its activities.

An Indian Bahá'í living in England, wrote a letter on 5 May 1921, about a lecture of Shoghi Effendi’s which he attended:

On Wednesday evening I went to attend the usual Bahá'í meeting at Lindsay Hall. Mr. Shoghi Rabbani read a paper dealing with the economic problems and their solution. His paper was beautifully worded and was very good..

Shoghi Effendi also presented papers at Oxford, as he mentions himself in a letter:

I shall also later send you a paper on the Movement which I read some time ago at one of the leading societies in Oxford.

A view of East cliff in Bournemouth, where Dr. Esslemont was living, a place Shoghi Effendi visited often during his time in England. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Shoghi Effendi spent part of his long summer vacation in 1921, studying in the Holywell Annexe near Manchester College. But 'Abdu'l-Bahá had sent strict instructions that Shoghi Effendi was to rest outside of London and not engage in any studies or work during his break, and so, Shoghi Effendi obeyed.

He visited Dr. Esslemont in Bournemouth for two weeks starting 20 July 1921. Shoghi Effendi’s sister Rúhangiz, met him in London on 25 September on break from her studies in Scotland. She was staying with Mary Thornburgh-Cropper, and Shoghi Effendi also had the opportunity to see Lady Blomfield.

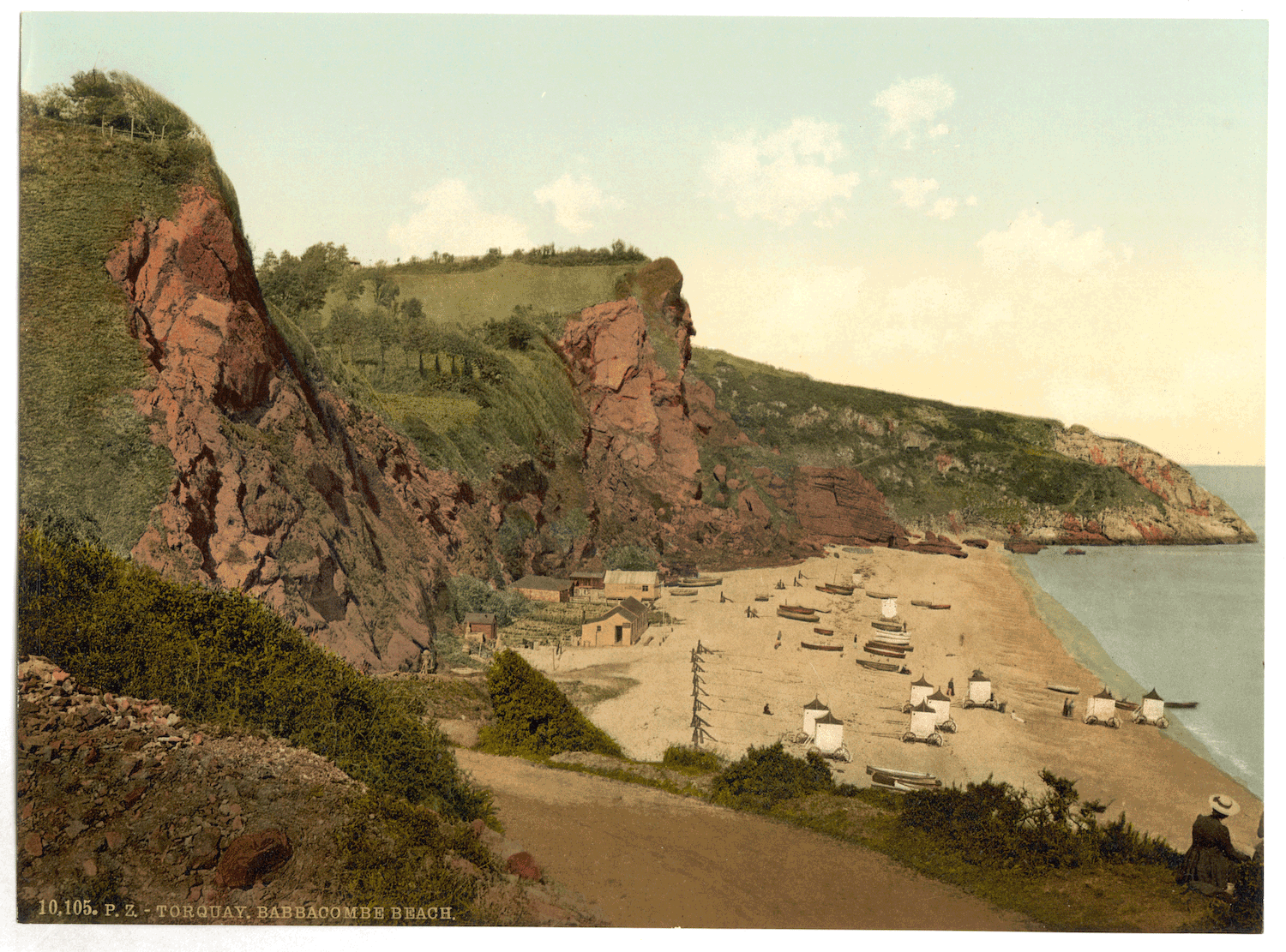

Then Shoghi Effendi spent a few weeks in Torquay (see the story below) and visited Manchester (see the next two sections below).

Beautiful Babbacombe Downs, with the highest cliff top promenade in England and its naturally red dirt paths which so inspired Shoghi Effendi. The red dirt paths are not shown but can be imagined given the stunning red of the cliff face. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

On 10 August 1921, Shoghi Effendi visited Torquay, a seaside resort in the south of England, where he stayed for three weeks.

It must have been during this visit that Shoghi Effendi had the opportunity to walk through the park of Babbacombe downs, near Torquay, a beautiful seaside garden of striking green grass, bright red earth paths, white ornamental vases against a crisp blue sky.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum later surmised that Babbacombe was Shoghi Effendi’s inspiration for the red crushed red tile or brick paths, perfect green lawns, and granite and marble ornaments in the gardens surrounding the Shrines of Bahá'u'lláh and the Báb in Bahjí and Haifa.

The Manchester Bahá'í community, with around 30 believers, was one of the oldest in England, and was very active and devoted. Dr. John E. Esslemont visited Manchester in late August 1921 to stay with the Bahá'ís for a few days and visit his friends. He told the elated Manchester community that Shoghi Effendi, the grandson of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, would be visiting them soon.

On the evening of Saturday 1 October 1921, the Bahá'ís of Manchester gathered in the basement room of the Mosley Street offices of Jacob Joseph—a very successful Persian real estate agent of distinguished Jewish background from the well-known Mottahedeh family—all eagerly awaiting Shoghi Effendi’s arrival, close to the start of his new Michaelmas term at Oxford University.

When Shoghi Effendi walked into the room, he made everyone feel perfectly at ease. Edward Hall, one of the veteran Bahá'ís of Manchester Bahá'í, gave a charming description of the 24-year-old Shoghi Effendi, just two months before he became the Guardian of the Cause:

His eyes were bright, his voice reassuring, his manners perfect, his features beautiful. He was as one, who, having control of himself, would therefore be able to control others. He commanded respect without seeming to know it. His youthfulness attracted us and the brightness of his thoughts called out our admiration. We all became very happy, and led him to the principal chair.

Norah Crossley, a new Bahá'í at the time of Shoghi Effendi’s visit. Enlarged from the Manchester Bahá'ís photograph. Source: Some Bahá’ís to Remember, O. Z. Whitehead, between pages 36 and 37.

Norah Crossley had only been a Bahá'í for three months. Her father had died, and her mother, a devout Irish Catholic, was estranged from her. The night he arrived in Manchester, Shoghi Effendi, wanting to describe to the Bahá'ís how much 'Abdu'l-Bahá was pleased with Norah Crossley, placed her in the chair next to his, and as soon as all 19 Bahá'ís were seated, he shared with them a Tablet revealed in August 1921 by 'Abdu'l-Bahá to the Bahá'ís of Najafábád in which He spoke about Norah Crossley’s exquisite sacrifice: too poor to contribute money towards the construction of the House of Worship in North America, had donated her hair.

Norah Crossley was deeply enkindled, and thought of nothing but of how to serve the Faith. She spent her days deepening herself in her new Faith and had fallen in love with the Persian language and handed Shoghi Effendi a Tablet revealed for her by 'Abdu'l-Bahá, asking him to chant it. Shoghi Effendi was so moved by 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s sweetness of words and expressions in the Tablet that tears streamed from his face as he was chanting, and the Manchester Bahá'ís were deeply moved by the experience.

Among the audience was a priest, Mr. Heald, an eloquent and persuasive orator who spoke with utmost sweetness and eloquence in praise and admiration for Bahá'u'lláh. That same evening, Lucy Hall asked Shoghi Effendi to write in her autography book, and he left the following exquisite inscription, perhaps the only prayer in English we possess from Shoghi Effendi—the rest of which he only wrote in Persian and Arabic:

O Divine Providence! Pitiful are we; grant us Thy succour! Homeless and wanderers; give us Thy shelter! Scattered; do Thou unite us! Astray; join us to the fold! Bereft; do Thou bestow upon us a share and portion! Athirst; lead us to the wellspring of Life! Frail; strengthen us! that we may arise to exalt Thy Cause and present ourselves a living sacrifice in the pathway of guidance! What can I offer sweeter than the words of the Beloved Master? I trust you will commit them to memory and remember me. To Miss Lucy Hall from Shoghi, her brother in Bahá’u’lláh.

The friends stayed together until midnight that night.

Lua Getsinger around 1910. Source: A Love Which Does Not Wait, Janet Ruhe-Schoen, page 2.

On the evening of Sunday 2 October 1921, Shoghi Effendi listened intently to the friends singing hymns, then related a very moving story from one of Lua Getsinger’s many pilgrimages to the Holy Land.

Shoghi Effendi told the Bahá'ís in Manchester that on one of her several extended pilgrimages, 'Abdu'l-Bahá asked Lua to step out onto the roof terrace of his House in Haifa, in the cool, fragrant night and sing the hymn He loved the most “Nearer My God to Thee.” Lua's voice would rise and fall like a nightingale's while they stood facing Bahjí, lying across the plain, and her singing and the joy of 'Abdu'l-Bahá was evident, as He wept, tears streaming down His Blessed face.

A general view of Manchester from 1905. Source: Library of Congress.

From Manchester, Shoghi Effendi wrote a lengthy, very detailed, four-page letter to his Grandfather which he begins by joyfully describing the radiance of the Bahá'ís of Manchester as having “no peer except among the friends in Iran”:

My Master, my ultimate goal, my Beloved, how can I express my gratitude that Thou hast manifested such sincere, firm and blessed souls in this great city…These friends have kindled such light and fire in this city that its like has not been seen since the dawn of the Cause of God in these British Isles.

Shoghi Effendi describes in detail the services of two Bahá'ís, first that of Jacob Joseph, the Persian businessman, and one of three Persian Bahá'ís in Manchester and transmits to 'Abdu'l-Bahá their offer to sponsor pioneers:

There are three Iranian believers here, brothers from the Mottahedeh family: Jacob, Joseph and Abraham. One of them is successful in the real estate business. They provide a high level of assistance to these poor and needy believers. Having obtained subscriptions to the Star of the West and Glad Tidings for a group of these friends, they are distributing the publications in this city. Some time ago he had sent 19 guineas as a contribution to the London community through Miss Rosenberg. This same Persian youth, Mr Joseph, has begged me to submit to Your holy presence his offer that should You wish to send teachers to these regions, he would pay all their expenses, as his business affairs are, praise be to God, prospering.

The other Bahá'í Shoghi Effendi describes in great detail to 'Abdu'l-Bahá is Edward Hall, one of the most veteran Bahá'ís of Manchester, describing his services to his Grandfather, and the spirit of his daughter:

The spiritual father of this community of friends is Mr Hall. He has even set aside concern for earning his livelihood and is moving from place to place, from church to church, striving with enthusiasm to teach the souls. He has a daughter who, in her love for the Faith and her warmth of devotion, reminds one of the maidservants of God in Iran with longstanding training in the Cause.

The enkindlement of the Manchester Bahá'ís was such a surprise to Shoghi Effendi that he told 'Abdu'l-Bahá the center of the Bahá'í community in England was not London, and these two paragraphs, towards the end of the letter, praising the Manchester Bahá'ís are truly extraordinary in Shoghi Effendi’s spiritual joy, his passion and enthusiasm:

Truthfully, I never imagined that there were such souls in this city. The centre of the Cause is really Manchester, not London…They are thirsty for news of the progress of the Cause and have such attachment to the person of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá…They are truly worthy and deserving…Meeting with these friends brings such spiritual warmth that I cannot describe.

What steadfastness and certitude! They are confident as a mountain that this Cause will spread worldwide. The actions and efforts of these friends are beyond words…I was so moved by meeting these true servants of the Blessed Beauty that I could not sleep comfortably last night, until the morning arrived and I penned this supplication to describe their condition.

A Manchester street in 1925. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The next day, Monday 3 October 1921, Shoghi Effendi and Ḍíyá’u’lláh Aṣgharzádih called on Edward and Lucy Hall and offered them the gift of a beautiful photograph of 'Abdu'l-Bahá on which he had inscribed a few words of esteem for the Hall family—Edward, Lucy and their two children. After his visit to the Halls, Shoghi Effendi was taken to visit Reverend Johnson, a Manchester minister who was a sincere friend of the Faith.

That evening, Shoghi Effendi bought several bunches of purple grapes on the way to meet the Manchester friends in Jacob Joseph’s office on Mosley Street. At 8:00 PM, Shoghi Effendi chanted a prayer in the presence of 23 people, then proceeded to recount the spirit of the Bahá'í gatherings in Haifa and in Persia, to give the English friends a glimpse of the spirit that pervaded them. Then, Shoghi Effendi divided up the grapes between all those present, telling them to think of their brothers and sisters around the world. The Bahá'ís of Manchester were deeply moved.

After a while, Shoghi Effendi stood up and showed the friends a small bottle of attar of rose which the Greatest Holy Leaf, 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s younger sister, had given him, and had asked he anoint the friends when the meeting had risen to a spiritual atmosphere. Shoghi Effendi felt the moment had arrived, and he asked all the friends gathered to hold out their hands, palm upwards, as he passed around the room depositing a drop of that pure essential oil on their hands. The Bahá'ís rubbed their hands together, and spread the divine fragrance on their foreheads and hair until the entire room was deliciously fragrant.

As Shoghi Effendi was s peaking of Bahá'í gatherings in the Holy Land and Persia, the Manchester Bahá'ís felt transported to another place and time, gone from Manchester, and their spirits all gathered in the Holy Land.

The Manchester Town Hall in Albert Square. Photo by Chris Curry on Unsplash.

On that most spiritual evening, the Bahá'ís of Manchester wrote a joint, deeply united letter to 'Abdu'l-Bahá, signed by everyone present. The letter opened:

O our dear Lord and loving Master, at this moment when we are full of joy that we have attained to the meeting with thy richly illumined, beautiful, and radiant grandson, Shoghi Effendi, and have become re-inspired and re-invigorated by the pure flame of his love and his message to us.

The Bahá'ís of Manchester appealed to 'Abdu'l-Bahá, despite the fact that they felt “so small and insignificant” and asked 'Abdu'l-Bahá to grant that they “be one with Thee, living with Thee in the Divine Kingdom,” and begged for His prayers. Given the fact that 'Abdu'l-Bahá would pass away one month after receiving their letter, there is such a sense of sadness in the closing of the letter from these faithful Manchester Bahá'ís:

We pray for the everlasting success of Thy Divine Mission, rejoicing that Thou art in good health, and full of love towards us.

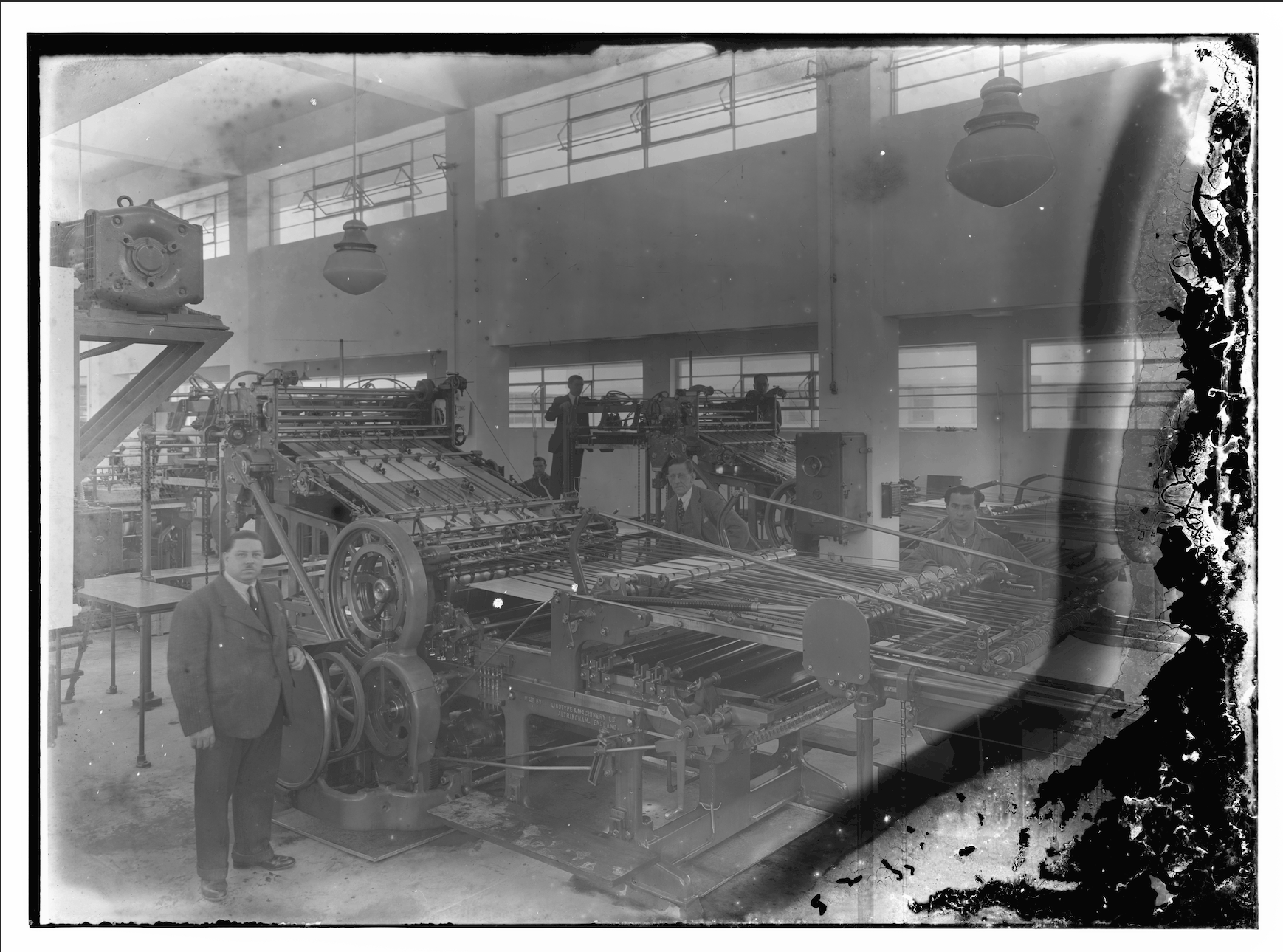

A British Linotype plant. Source: Library of Congress.

One of the Bahá'ís, John Craven, worked at a linotype factory called Linotype Works, and on Tuesday 4 October 1921, thanks to the fact the managers of the factory were friendly to the Bahá'ís, John Craven showed Shoghi Effendi around the premises.

Linotype machines had completely revolutionized the printing business, allowing newspapers among others to mold an entire “line of type” of characters at once, not just individual letters.

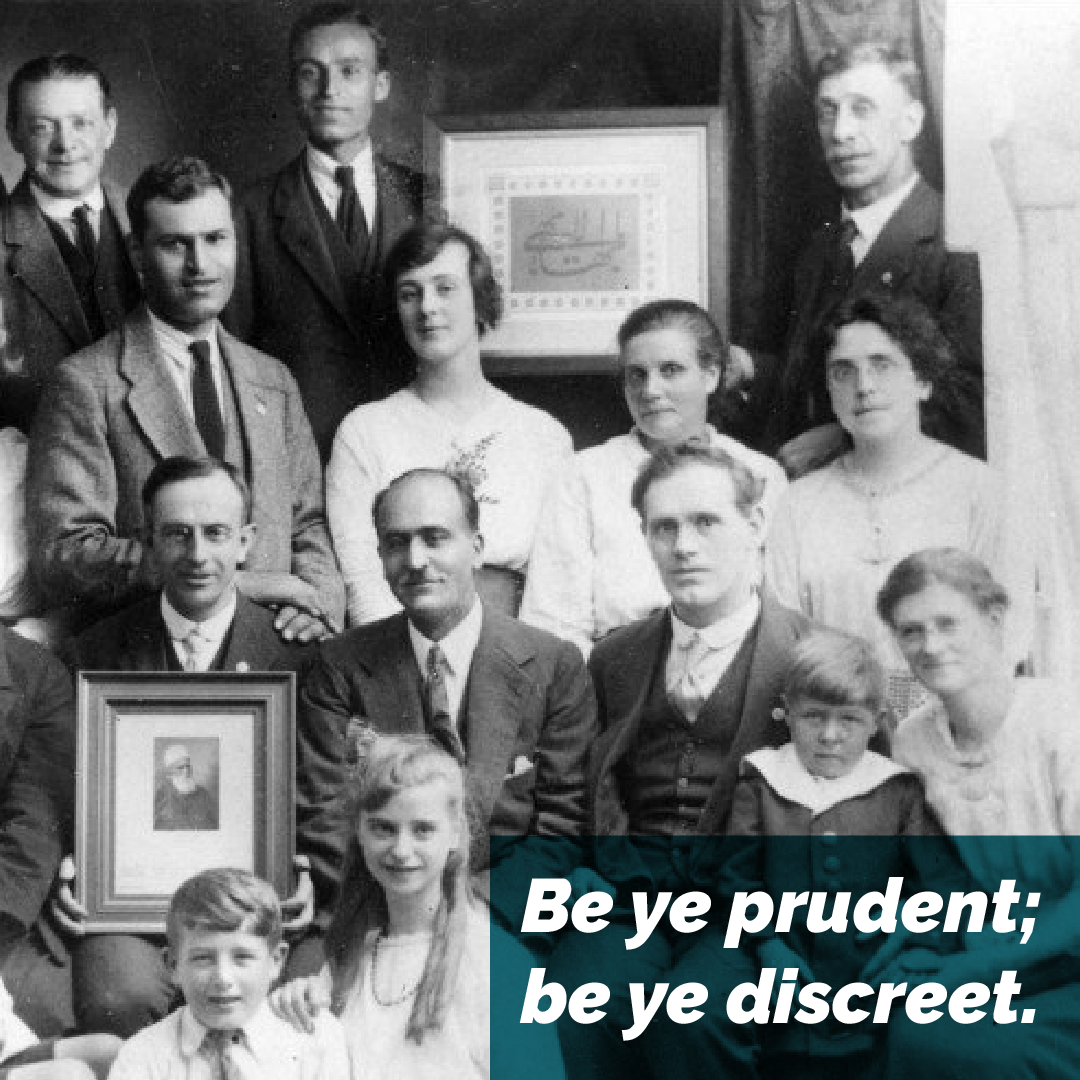

In the evening, Shoghi Effendi attended a meeting of believers and seekers at John Craven’s home. The next day, in the early evening of Wednesday 5 October 1921, Shoghi Effendi was back at Jacob Joseph’s office on Mosley Street with 26 people present. Ḍíyá’u’lláh Aṣgharzádih offered a silk handkerchief and a Bahá'í ringstone to everyone, and then anointed them with attar of rose, and at 8:00 PM everyone walked a short distance to a photographer’s studio on Oldham Street for the beautiful group portrait that illustrates this story.

Shoghi Effendi and Ḍíyá’u’lláh Aṣgharzádih left Manchester, Ḍíyá’u’lláh for London and Shoghi Effendi returning to Oxford on the morning of the following day, Thursday 6 October 1921.

Shoghi Effendi and Edward Hall, enlarged from the photograph of Manchester Bahá'ís.

Shoghi Effendi absolutely loved his five days in Manchester, something extremely obvious in the opening lines of a very long and significant letter he wrote, four days later, from Balliol College to thank Edward Hall:

My dearest Bahá'í brother: The sweet perfume of the friends in Manchester has clung to us wherever we have gone and now that I find myself again in the cold and academic atmosphere of Oxford, my thoughts go back to the sweet hours I have spent in your midst.

We see the future Guardian, the builder of the Administrative Order in the next section of the letter, focused on the growth of the Faith and the teaching efforts of the Bahá'ís:

My earnest hope is that the seed the Master has so tenderly and wisely planted in that city may soon germinate and give rise to a stately tree that shall in the near future overshadow all the other spiritual centres throughout the British Isles and brave every storm of test that may break upon it.

Included in the letter was a priceless gift bestowed by Shoghi Effendi to the Hall family: a precious relic, a lock of the hair of Bahá'u'lláh, which he had promised them in Manchester, which, Shoghi Effendi hoped would “ensure the safety and the protection of your home and will as a lodestone bring to you the hallowed memories of the days and life of the ever Blest Beauty.”

Shoghi Effendi shared with Edward Hall that he had forwarded the joint supplication of the Manchester friends to 'Abdu'l-Bahá, and made a touching request:

…my first and last request is that the friends, one and all, may persevere to the very end in holding their regular meetings. The Master has so often emphasized the vital necessity of such gatherings in all newly established Baha’i Centres for the meeting itself possesses a peculiar power in attracting divine confirmations.

Shoghi Effendi ended the letter with yet another precious gift: a rare photograph of 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s martyred younger brother, Mírzá Mihdí, for Edward’s son.

“Be ye prudent; Be ye discreet.” 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s advice to the Bahá'ís of Manchester in a Tablet dated 18 October 1921.

Eight days after Shoghi Effendi’s letter to Edward Hall, 'Abdu'l-Bahá revealed a Tablet dated 18 October 1921, addressed “To the beloved of the Lord in the city of Manchester,” in which He acknowledges receipt of their united letter, signed by 24 Manchester Bahá'ís. In part, 'Abdu'l-Bahá wrote:

Your letter hath been received, and the contents thereof have imparted the utmost joy and gladness. Praised be the Lord, ye have eyes that see and ears that hear. Ye behold the Light of Truth and are accounted, even as Christ hath said, among the Chosen rather than among the Called.

'Abdu'l-Bahá ends His tablet advising cautiousness and prudence:

Wherefore, praise ye the Lord, that in the lamp of your hearts the Flame of Divine guidance is kindled and ye have entered the Kingdom of God. It is incumbent upon you, however, to act with the utmost discretion and not rend the veil asunder, for the enemy, though he be near or afar, lieth in wait and stirreth the negligent to arise against His Holiness Bahá’u’lláh; Be ye prudent; be ye discreet.

Shoghi Effendi in Manchester with the three Joseph Brothers—Jacob, Jeff and Albert. Source: © George Ronald Publishing, used with permission.

On 20 October 1921 'Abdu'l-Bahá revealed a following Tablet for Jacob Joseph and his brother, Ibráhím, translated by Shoghi Effendi which begins:

O ye that stand fast and firm in the Covenant! The faithful servant of the Ever-Blest Beauty, Shoghi Effendi, hath written a letter, and therein hath praised you most highly, namely, that these blessed souls are true Bahá’ís, are verily self-sacrificing, burn brightly, even as twin candles, with the Light of Guidance, serve with heart and soul the Cause of God, succour the needy amongst the faithful, and seek fellowship with the poor. Such praise as this hath indeed caused the greatest pleasure

An aerial view of Oxford and its many quads. Photo by Sidharth Bhatia on Unsplash.

As Shoghi Effendi was beginning the last of his terms in Oxford, he wrote a kind letter to the Bahá'ís of Manchester, expressing how much he enjoyed the “sweet hours” he spent with them.

A couple of weeks later, 'Abdu'l-Bahá responded to the Manchester friends’ joint supplication, expressing his joy at their letter, and their love of Shoghi Effendi.

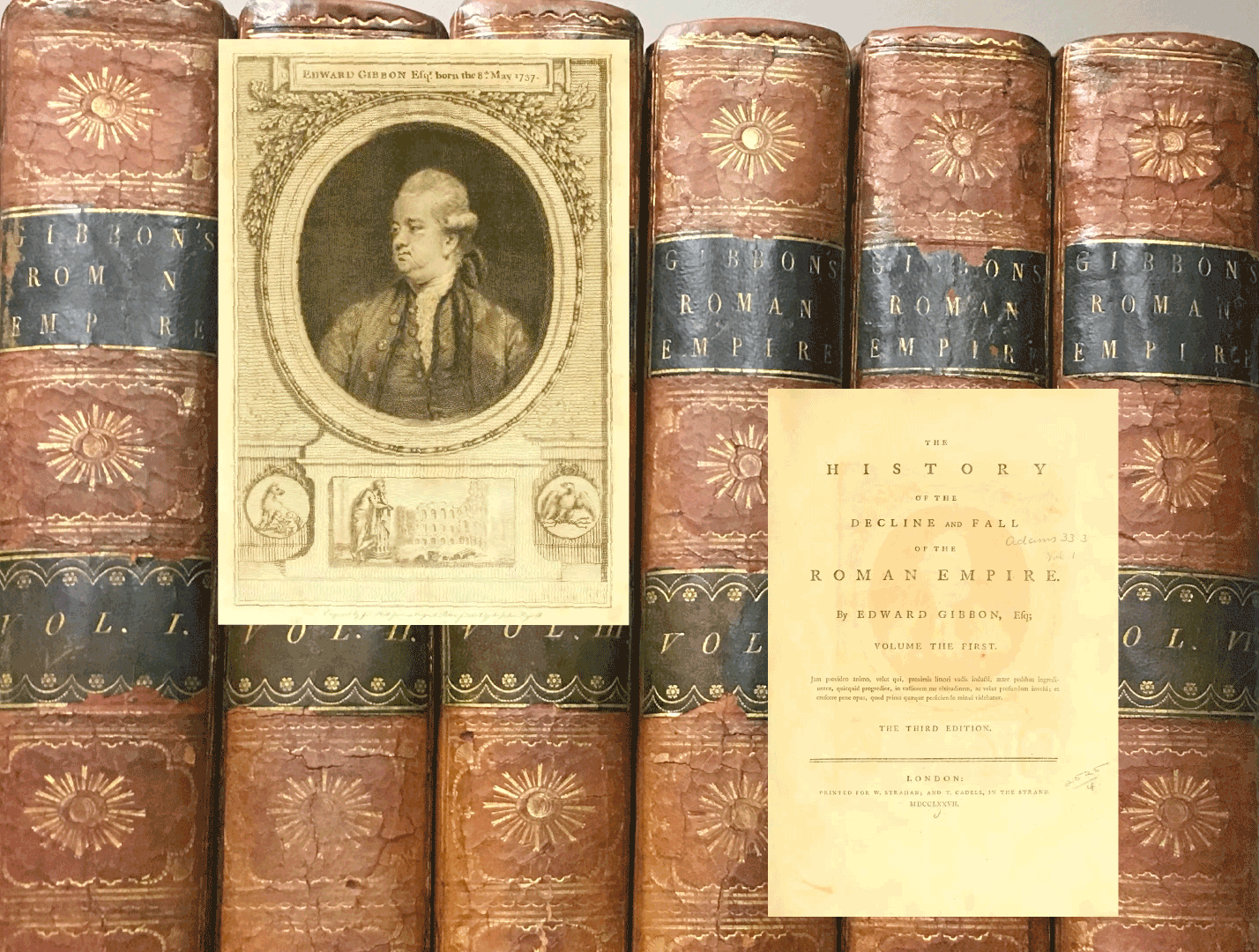

Sometime in his studies in Oxford, Shoghi Effendi discovered a book that would have a tremendous impact on his literary style: Edward Gibbon’s masterpiece, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.

Shoghi Effendi fell in love with Gibbon’s prose, and the way he described momentous historical events, a style he would greatly adapt and elevate as Guardian of the Cause in order to tell the sweeping history of the Bahá'í Faith, and in exposing its spiritual principles in his letters.

So many of Shoghi Effendi’s friends and classmates would later remember him, sitting in the Garden Quad, or walking around on summer evenings, reading this book, so taken was he by its elegant and majestic style.

All his life, Shoghi Effendi’s studies had been hard for him. He was never really happy in any educational institution he attended, and though he had many memories of Oxford, they were not all positive, as Shoghi Effendi stated in several of his letters to friends during his time there that he had been very lonely and depressed.

Shoghi Effendi had a shy nature and did not make close friends in Oxford, although he was hosted at the home of his professor D. S. Margoliouth, an Arabic scholar and orientalist and his wife, who thoroughly enjoyed having him over.

The Doe Memorial Library, completed in 1911, and the main library at University of California at Berkeley. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

While ‘Alí Yazdí was in California, he received the last Tablet revealed by 'Abdu'l-Bahá for him. It is clear that 'Abdu'l-Bahá cared for ‘Alí Yazdí because of how close he was to Shoghi Effendi, and the fact the two young men had, by this time, been friends for a decade, evident in the Tablet’s inscription, where the Master referred to ‘Alí Yazdí as “The spiritual son, Shaykh, upon him be the Glory of God, the All-Glorious.”

O Shaykh-’Alí who are dear to the spiritually minded.

Render thanks unto God that in this blessed age thou hast stepped forth into the world of existence, been nursed from the breast of the love of God and hast been reared in the bosom of divine guidance, and that now with the permission of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and by His leave thou art proceeding to America to study the sciences. Thy father is here with us at the Holy Threshold, and we both pray on thy behalf and beseech for thee the assistance and favor of the Blessed Perfection. And upon thee be His glory.

‘Alí Yazdí received this Tablet while he was attending UC Berkely, and just one year before 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s Ascension.

A 1605 map of Oxford, then a walled city, with Balliol College—Shoghi Effendi’s college—already indicated on the map. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Shoghi Effendi was not in Oxford long, but even though his stay was brief, it was immensely successful.

The heightened and rarefied atmosphere of academic excellence that Shoghi Effendi absorbed while in Oxford, in Amatu’l-Bahá Rúḥíyyih Khánum’s words:

…shaped and sharpened his already clear and logical mind, heightened his critical faculties, reinforced his strong sense of justice and reasoning powers, and added to the oriental nobility which characterized Bahá'u'lláh's family those touches of the culture we associate with the finest type of English gentleman.

Shoghi Effendi himself detailed the progress he had made in his studies in Oxford in a letter he wrote to a British believer on 22 November 1921, a letter in which Shoghi Effendi’s mastery and self-confidence are clearly visible:

...I have been of late immersed in my work, revising many translations and have sent to Mr. Hall my version of Queen Victoria's Tablet which is replete with most vital and significant world counsels, so urgently needed by this sad and disillusioned world! If you have not yet perused it be sure to obtain it from Mr. Hall as it is in my opinion one of the most outstanding and emphatic pronouncements of Bahá'u'lláh on world affairs.

In a Persian letter addressed to one of his friends in London, Shoghi Effendi expresses satisfaction at his academic progress:

I am engaged in this land, day and night, in perfecting myself in the art of translation...I do not have a moment's rest. Thank God that to some extent at least the results are good.

Queen Victoria. Source: An 1880 chromolithograph print of a portrait of Queen Victoria. Source: Library of Congress.

One month after his visit to Manchester, Shoghi Effendi wrote a letter to John Craven from the Junior Common Room in Balliol College, Oxford, regarding one of Bahá'u'lláh’s weightiest and most significant Tablets, the Tablet to Queen Victoria which He revealed in 1870, while in the Most Great Prison.

Shoghi Effendi describes his efforts in translating the Tablet to Queen Victoria, which is “replete with most vital and significant world counsels, so urgently needed by this sad and disillusioned world!” Shoghi Effendi describes the Tablet, revealed by Bahá'u'lláh while He was imprisoned in the Most Great Prison in 'Akká, as, in his opinion, “one of the most outstanding and emphatic pronouncements of Bahá'u'lláh on world affairs.”

When describing the contents of the Tablet, Shoghi Effendi mentions that Bahá'u'lláh considered Queen Victoria as “an able and well-intentioned ruler,” and quotes Bahá'u'lláh as praising her in this Tablet for having forbidden the trading in slaves:

We have been informed that thou hast forbidden the trading in slaves, both men and women. This, verily, is what God hath enjoined in this wondrous Revelation.

Bahá'u'lláh also praises Queen Victoria for her system of Government:

We have also heard that thou hast entrusted the reins of counsel into the hands of the representatives of the people. Thou, indeed, hast done well…

Shoghi Effendi quoted John Craven another passage, Bahá'u'lláh speaks to Queen Victoria about the sovereign remedy for the world’s ills:

That which the Lord hath ordained as the sovereign remedy and mightiest instrument for the healing of all the world is the union of all its peoples in one universal Cause, one common Faith. This can in no wise be achieved except through the power of a skilled, an all-powerful and inspired Physician.

At the end of this very interesting letter, Shoghi Effendi concludes telling John Craven that 'Abdu'l-Bahá was so pleased to hear from the Manchester Bahá'ís.

Shoghi Effendi in his 20s. Source: Bahaimedia.

One of Shoghi Effendi’s goals in attending Oxford was to spend time with cultured and refined people, and he definitely made an unforgettable impression on the students who met him.

Shoghi Effendi stood out among his friends, because they knew he was somehow destined to head the Bahá'í Faith, and that made his future remarkable and very uncommon. Some of his friends in later years would describe him as unforgettable.

Even in his college years, Shoghi Effendi was known for having a restless energy, and not sitting down for long periods of time. He was friendly and easy to get along with, and enjoyed great conversations.

A classmate described Shoghi Effendi as irrepressibly cheerful and energetic, and brining positive energy to any gathering. Shoghi Effendi was seen as quiet but very quick-witted, and deeply informed.

Because his friends knew he was destined for spiritual leadership, he earned the nickname “God,” or “The God Kid.” There was absolutely no mockery intended in the nicknames, because Shoghi Effendi was much too well-liked for that. There was no rudeness or irreverence, they just admired him, but Shoghi Effendi was more often referred to as just “Rabbani.”

Shoghi Effendi loved to quote the great Persian poets Hafiz and Saadi, and he communicated this lifelong love to at least one of his friends at Oxford.

His friends knew that there was always Russian Caravan tea with cardamon seeds brewing in Shoghi Effendi’s room, and that was where they often congregated. Shoghi Effendi loved to have long conversations about broad ethical, social, and historical issues.

Shoghi Effendi even gave Persian cloth slippers to one of his friends, which he kept for years.

Shoghi Effendi was deeply committed to his aim, mastering English to the highest degree in order to be of most service to 'Abdu'l-Bahá.

At Oxford, students were supervised by tutors who helped them with their academic choices of courses and schedule. Shoghi Effendi’s tutor during his time at Balliol, was A. D. Lindsay, who, in 1924 would become Master of Balliol College.

In an informal conversation, years later, Lindsay shared the passion and eagerness of Shoghi Effendi in a very wonderful vignette:

Shoghi Effendi's idea of education was to discover somebody whose opinions he valued and then question him. When Shoghi Effendi got his answers he wrote them all in a small black book. I had posted my schedule;

Shoghi Effendi came to me asking, 'What do you do between seven and half past eight?'

'Why man,' I cried, 'I dine!'

'Oh', said Shoghi Effendi with obvious disappointment, 'but must you have all that time?"

I had not found so much eagerness for knowledge at Oxford.

So I gave him another quarter-hour and went with less dinner. So it was - I suffered for him.

Shoghi Effendi had a definite goal in attending Oxford, and he was determined to attain it. This is clearly outlined in a letter he wrote on 18 October 1920:

My dear spiritual friend...God be praised, I am in good health and full of hope and trying to the best of my ability to equip myself for those things I shall require in my future service to the Cause. My hope is that I may speedily acquire the best that this country and this society have to offer and then return to my home and recast the truths of the Faith in a new form, and thus serve the Holy Threshold."

In the spring, Shoghi Effendi avidly played tennis, a sport he not only loved but was extremely good at.

He played tennis with many adversaries in the Master’s field, and he was very talented. He played with high energy, and, being ambidextrous, he could switch his racket flawlessly from his right to his left hand.

He would hit volleys at the net with tremendous speed, and laughed while he played.

Shoghi Effendi often hit unstoppable shots, and he served the ball from as far back in the court as he could, running through his serve with great energy. Although Shoghi Effendi was short, his serve was ferocious.

Most of his opponents would remember Shoghi Effendi as a very pleasant person to play tennis with, and he sometimes goaded players he knew were very talented into playing game with him.

The six volumes of Edward Gibbon’s “The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire,” with an engraving of Gibbon and the title page from the 1777 Third Edition. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Shoghi Effendi was deeply methodical in his learning of English. Until the end of his life, he kept a habit he had picked up in Beirut, which was to write hundreds of vocabulary words and phrases in his little notebooks. As Rúḥíyyih Khánum stated:

For him there was no second to English.

Shoghi Effendi was a great reader of King James version of the Bible, and of the historians Carlyle and Gibbon, whose style he greatly admired, and which would later show their influence in his superlative English style. His love of Biblical English would also be reflected in Shoghi Effendi’s future translations of Bahá'u'lláh’s prayers and Meditations, The Hidden Words, and the Kitáb-i-Íqán.

SOURCES FOR PART IV

April – July 1920: La Maison d’hydrothérapie et de convalescence du Parc de Neuilly

The Priceless Pearl, Rúḥíyyih Rabbání, Bahá’í Publishing Trust, London, 1969, pages 31-32.

Blessings Beyond Measure: Recollections of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and Shoghi Effendi. ‘Alí M Yazdí. Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1988, pages 72-73.

Wikipedia: Neuilly-sur-Seine.

8 May 1920: Shoghi Effendi’s letter to ‘Alí Yazdí from Neuilly

Blessings Beyond Measure: Recollections of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and Shoghi Effendi. ‘Alí M Yazdí. Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1988, pages 72-73.

11 June 1920: Application to Oxford

Prelude to the Guardianship. Riaz Khadem, George Ronald, Oxford, 2014, Kindle Edition, Locations 2713 and 2992.

Bahaipedia: Shoghi Effendi.

28 June 1920: At last, Shoghi Effendi is fully recovered

Blessings Beyond Measure: Recollections of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and Shoghi Effendi. ‘Alí M Yazdí. Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1988, pages 73-75.

Violetta Zein, The Extraordinary Life of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá Part VII: Journeys to the West:

International Encyclopedia of the First World War: Bliss, Howard S.

The parallel between ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s and Shoghi Effendi’s experiences in France

Blessings Beyond Measure: Recollections of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and Shoghi Effendi. ‘Alí M Yazdí. Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1988, pages 73-75.

Violetta Zein, The Extraordinary Life of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá Part VII: Journeys to the West: Europe and Egypt (1912-1913): 23 January 1913 to Edith Sanderson: “Submerged in the sea of materialism”.

21 – 26 July 1920: Shoghi Effendi’s arrival in London

The Priceless Pearl, Rúḥíyyih Rabbání, Bahá’í Publishing Trust, London, 1969, pages 32-33.

Bahá’í Library Online chronology: The life of Shoghi Effendi.

26 July – 10 September 1920: Shoghi Effendi’s first month in Oxford

Bahá’í Library Online chronology: The life of Shoghi Effendi.

Prelude to the Guardianship. Riaz Khadem, George Ronald, Oxford, 2014, Kindle Edition, Location 2955.

28 July 1920: Letter to Florence Khan

The Priceless Pearl, Rúḥíyyih Rabbání, Bahá’í Publishing Trust, London, 1969, pages 32-33.

Blessings Beyond Measure: Recollections of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and Shoghi Effendi. ‘Alí M Yazdí. Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1988, pages 75, 78-82.

8 August 1920: Lord Lamington’s letter to ‘Abdu’l-Bahá

The Priceless Pearl, Rúḥíyyih Rabbání, Bahá’í Publishing Trust, London, 1969, page 33.

1920 – 1921: Shoghi Effendi and England

The Priceless Pearl, Rúḥíyyih Rabbání, Bahá’í Publishing Trust, London, 1969, pages 33-34.

10 – 15 September 1920: Five days with Dr. Esslemont

Bahá’í Library Online chronology: The life of Shoghi Effendi.

Prelude to the Guardianship. Riaz Khadem, George Ronald, Oxford, 2014, Kindle Edition, Location 2976-2992.

Wikipedia: Sanatorium.

Wikipedia: Bournemouth.

Bahá’í Chronicles: Dr. John E. Esslemont.

31 December 1912: ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in Oxford with Thomas Kelly Cheyne and Elizabeth Gibson Cheyne

31 December 1913 at 3:00 PM: ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s address at Manchester College

REFERENCES FOR THE TWO PREVIOUS STORIES:

Wikipedia: Thomas Kelly Cheyne.

Ahmad Sohrab’s European Diary, 21 December 1912.

Redman, Earl. ‘Abdu’l-Baha in Their Midst, Kindle Edition.

Judy Greenway: From the Wilderness to the Beloved City: Elizabeth Gibson Cheyne.

Violetta Zein, The Extraordinary Life of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá: The illustrated chronology of the life of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá Part VII: 31 December 1912 – OXFORD – The spiritual philosopher and the angelic woman.

The Chosen Highway, Lady Blomfield.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá in Britain 1913, compiled by David Merrick, page 90.

August – October 1920: Shoghi Effendi prepares to matriculate at Oxford

Blessings Beyond Measure: Recollections of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and Shoghi Effendi. ‘Alí M Yazdí. Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1988, pages 75, 78-82.

Prelude to the Guardianship. Riaz Khadem, George Ronald, Oxford, 2014, Kindle Edition, Locations 2942, 3094, 3176 and 3224.

5 October 1920: Shoghi Effendi’s letter to ‘Alí Yazdí

Blessings Beyond Measure: Recollections of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and Shoghi Effendi. ‘Alí M Yazdí. Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1988, pages 75, 78-82.

Prelude to the Guardianship. Riaz Khadem, George Ronald, Oxford, 2014, Kindle Edition, Locations 2942, 3094, 3176 and 3224.

The Priceless Pearl, Rúḥíyyih Rabbání, Bahá’í Publishing Trust, London, 1969, pages 35-36 and 38.

St. Catherine’s College Oxford: College History.

Bahaipedia: Shoghi Effendi.

Prelude to the Guardianship. Riaz Khadem, George Ronald, Oxford, 2014, Kindle Edition, Locations 2942, 3094, 3176 and 3224.

Our beloved Guardian: An Introduction to the Life and Work of Shoghi Effendi, Lowell Johnson Johannesburg: National Spiritual Assembly of South Africa, 1993.

Bahá’í Library Online chronology: The life of Shoghi Effendi.

The term names at Oxford University: Michaelmas, Hilary and Trinity

University of Oxford.

Oxford visit.

Wikipedia: Michaelmas Term.

Wikipedia: Hilary Term.

Wikipedia: Trinity Term.

3 November 1920: Shoghi Effendi invites ‘Alí Yazdí to Oxford

Blessings Beyond Measure: Recollections of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and Shoghi Effendi. ‘Alí M Yazdí. Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1988, pages 82-83.

Wikipedia: James Bryce, 1st Viscount Bryce.

3 – 4 November 1920: Shoghi Effendi and ‘Alí Yazdí in Oxford

Blessings Beyond Measure: Recollections of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and Shoghi Effendi. ‘Alí M Yazdí. Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1988, pages 83-84.

Bahaipedia: ‘Alí Yazdí.

6 November 1920: Shoghi Effendi’s letter to ‘Alí Yazdí

Blessings Beyond Measure: Recollections of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and Shoghi Effendi. ‘Alí M Yazdí. Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1988, pages 84-85.

Bahaipedia: ‘Alí Yazdí.

10 November 1920: Shoghi Effendi’s farewell letter to ‘Alí Yazdí, on his way to California

Blessings Beyond Measure: Recollections of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and Shoghi Effendi. ‘Alí M Yazdí. Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1988, pages 42 and 85-86.

Blessings Beyond Measure: Recollections of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and Shoghi Effendi. Ali M Yazdí, Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1988, pages 42-43.

December 1920 – Winter break: Visiting Mrs. Whyte in Scotland

The Priceless Pearl, Rúḥíyyih Rabbání, Bahá’í Publishing Trust, London, 1969, page 36.

The Priceless Pearl, Rúḥíyyih Rabbání, Bahá’í Publishing Trust, London, 1969, pages 34-35.

Oxford university: What is an Oxford college?

Balliol College, University of Oxford: About Balliol.

Wikipedia: Balliol College, Oxford.

Prelude to the Guardianship. Riaz Khadem, George Ronald, Oxford, 2014, Kindle Edition, Location 3199

January – March 1921: Shoghi Effendi’s Hilary (second) term at Oxford

The Priceless Pearl, Rúḥíyyih Rabbání, Bahá’í Publishing Trust, London, 1969, pages 35-36 and 38.

Bahaipedia: Shoghi Effendi.

Prelude to the Guardianship. Riaz Khadem, George Ronald, Oxford, 2014, Kindle Edition, Location 3224, 3364 and 4538.

27 March – April 1921: Scotland and Sussex

The Priceless Pearl, Rúḥíyyih Rabbání, Bahá’í Publishing Trust, London, 1969, page 33.

Prelude to the Guardianship. Riaz Khadem, George Ronald, Oxford, 2014, Kindle Edition, Location 3491.

Bahaipedia: Shoghi Effendi.

Bahá’í Library Online chronology: The life of Shoghi Effendi.

April – June 1921: Shoghi Effendi’s Trinity (third) term at Oxford

Prelude to the Guardianship. Riaz Khadem, George Ronald, Oxford, 2014, Kindle Edition, Location 3510.

Bahá’í Library Online chronology: The life of Shoghi Effendi.

5 May 1921: A paper on economic problems and solutions

The Priceless Pearl, Rúḥíyyih Rabbání, Bahá’í Publishing Trust, London, 1969, page 34.

June – October 1921: Summer Vacation

The Priceless Pearl, Rúḥíyyih Rabbání, Bahá’í Publishing Trust, London, 1969, page 33.