Written and illustrated by Violetta Zein

This part covers the life of Shoghi Effendi at the age of 60 in 1957.

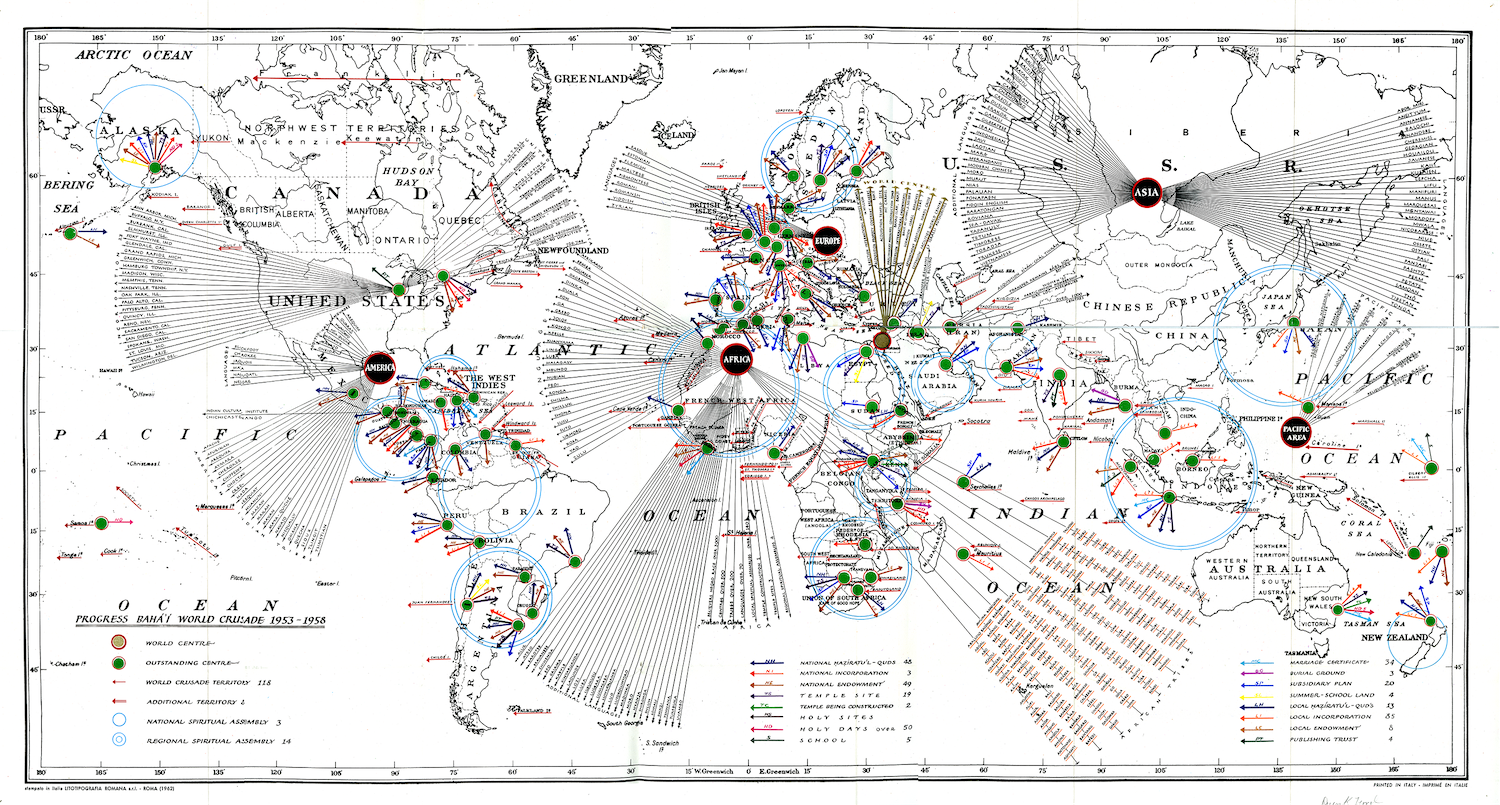

“It is killing me!” Background image: closeup of Shoghi Effendi’s last map, Map of the Progress of the World Crusade 1953 – 1958. Source: Bahá'í Library Online.

One day, when Rúḥíyyih Khánum was going through various lists and numbers with the Guardian, he said to her—as he had many times during the last year of his life—and said:

This work is killing me! How can I go on with this? I shall have to stop it. It is too much. Look at the number of places I have to write down. Look how exact I have to be!

Background photo by Dejan Zakic on Unsplash.

The Dispensation of Bahá'u'lláh holds a very special rank among the works of Shoghi Effendi.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum herself makes it abundantly clear that the Guardian attached a tremendous amount of importance to this long letter dated 8 February 1934 and addressed to the Bahá'ís of the United States and Canada, where he sheds light on the station of the three Central Figures of the Faith, the Guardianship and the Administrative Order.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum stated in the Priceless Pearl:

However Shoghi Effendi felt in his inmost heart about his other writings, I know from his remarks that he considered he had said all he had to say, in many ways, in the Dispensation.

Shoghi Effendi repeatedly stated to Bahá'í pilgrims that The Dispensation of Bahá'u'lláh should be regarded as his spiritual will and testament. And often, to Persian pilgrims, the Guardian would refer to it as his will.

These of course have the value of only pilgrim notes, but we do have a concrete and undeniable evidence from the Guardian himself about the importance the Dispensation of Bahá'u'lláh occupied in his mind. In a letter to an individual dated 11 May 1934, he wrote:

Shoghi Effendi was also pleased to learn of the response which [The Dispensation of Bahá'u'lláh]…has awakened in your community. It is his hope that the believers will, through their careful and continued study of this important communication, acquire a new vision of the Cause, and will be stimulated to redouble their efforts for the expansion and consolidation of their work for the Faith.

But the clearest testament to this strong feeling of the Guardian is a letter he wrote to Hand of the Cause Adelbert Mühlschlegel.

Dr. Adelbert Mühlschlegel had written to the Guardian if it would be possible for the German National Spiritual Assembly to publish a compilation of the Will and Testament of Bahá'u'lláh, and the Will and Testament of 'Abdu'l-Bahá.

The Guardian responded that this would be permissible, but that they should also consider adding the Dispensation of Bahá'u'lláh.

In his letter, the Guardian called the Dispensation of Bahá'u'lláh an invaluable supplement and annex to the Will and Testament of Bahá'u'lláh, and the Will and Testament of 'Abdu'l-Bahá.

“I suppose you will travel and encourage the friends.” Bahá’í Continental Conference of Africa, with Hand of the Cause Amatu’l-Bahá Rúhíyyih Khánum, in Monrovia, Liberia, in January 1971. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

One day, in the last years of his ministry, the Guardian was passing by Rúḥíyyih Khánum’s desk when he looked at her and asked:

What will become of you after I die?

Rúḥíyyih Khánum, frightened and agitated, said:

Oh, I don't want to live after you; don't say such terrible words.

The Guardian didn’t pay any attention to her words and continued, thoughtfully:

I suppose you will travel and encourage the friends.

Those were the only words the Guardian had ever spoken to Rúḥíyyih Khánum regarding her life without him. But the Guardian’s words were prophetic. Rúḥíyyih Khánum would sp end the rest of her life traveling around the world encouraging the Bahá'ís.

“I am getting so tired of my papers” Background photo by Niklas Bildhauer via Wikimedia Commons.

One evening, the Guardian came to dinner at the Western Pilgrim House in a deeply troubled mood. He didn't want to eat, and when Rúḥíyyih Khánum urged him to have some food he pushed the plate aside. He began to speak in an introspective way:

You know, shortly before Bahá'u'lláh passed away the Master went to see Him in Bahjí and found His papers strewn over the sofa. The Master collected them and laid them on the divan next to Bahá'u'lláh.

He said, “Bahá'u'lláh, I have collected your papers, I have put them in order and I have put them here for you.” Bahá'u'lláh said, “It is of no use to gather them, I must leave them and flee away.

Shortly before 'Abdu'l-Bahá passed away they found His papers scattered about His room, and He was very meticulous. His secretaries collected the papers, put them in order and brought them to the Master.

But He put them aside and said, “I am done with the papers, it is finished now. I don't want them anymore.” Shortly afterwards He passed away.

I am getting so tired of my papers, I don't want them anymore. I just don't want these papers any more. I am going to throw them away just as Bahá'u'lláh and 'Abdu'l-Bahá did.

An artistically faded map to indicate that Shoghi Effendi is currently working on his cherished map of the halfway point of the Ten Year Crusade which he will finish two days before his passing. The full image of the map will be available in that section, dated 2 November 1957. Source: Progress Bahá'í World Crusade 1953-1958, map by Shoghi Effendi, available on Bahá'í Library Online.

About two months before he passed away, Shoghi Effendi caught a cold, and had a fever the first night.

The second night, the fever was gone, but it was understood—perhaps by Rúḥíyyih Khánum more than by Shoghi Effendi—that he would remain in bed and rest.

But the Guardian decided to spend that day working on his last great map of the Ten Year Crusade which he named The Half-Way Point of the Ten-Year Crusade.

On this utterly thrilling map, the Guardian would create a massive infographic of the progress accomplished, the victories won, the territories settled, the countries and islands opened to the Faith.

For two months, the Guardian worked a great deal on this map, updating it with new information as it came. He would work on it right up until two days before his passing.

That day in September 1957, the Guardian worked on his map for 10 hours straight.

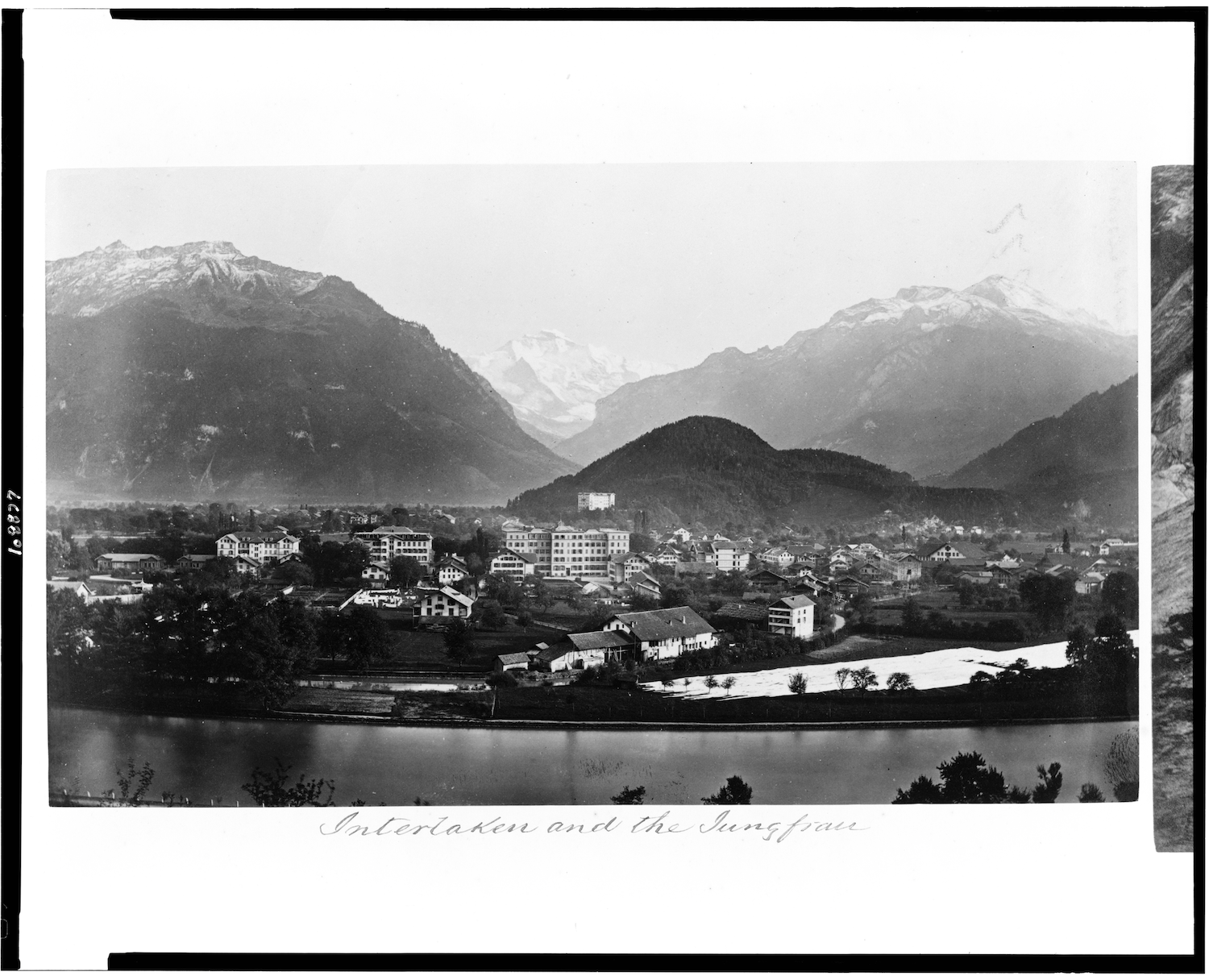

One of Shoghi Effendi’s favourite places: Interlaken and the Jungfrau— one of the main summits of the Bernese Alps—a photograph taken between 1860 and 1890. Source: Library of Congress.

By 1957, there was a surge of activity in the Administrative Order of the Faith worldwide, Bahá'í Institutions functioning at full capacity on all five continents, and, although his driving power never left him and he never decreased his long hours of work until the day he died, Rúḥíyyih Khánum could feel that Shoghi Effendi was very deeply tired.

In the summer of 1957, Shoghi Effendi left Haifa for the last time in his life and took Ruḥíyyíh Khánum back to his favorite mountain retreats in Switzerland, which he had loved for over three decades.

Shoghi Effendi’s health was excellent throughout the summer.

Looking back on her last grand tour with the Guardian, Rúḥíyyih Khánum said:

That last summer he went back to visit many of his favorite scenes in the mountains and I wondered about this too, when the blow fell, but at the time I was only happy to see him happy, forgetting, for a few fleeting moments, the burdens and sorrows of his life.

The only trace of a cable we have for Shoghi Effendi during his last summer in Messages to the Bahá’í World: 1950–1957, is one bearing wonderful news, the partial accomplishment of one of the objectives of the Ten Year Crusade—the re-interment of the remains of Bahá'u'lláh’s father—dated 17 July 1957 when the Guardian was in Switzerland, and it reads:

Inform Hands and national assemblies of transfer of remains of Mírzá Buzurg, marking attainment of yet another outstanding objective of the Crusade.

Advise avoid publicity.

“The Guardian is in perfect health.” Photo by Alyona Bogomolova on Unsplash.

For the past 10 years since 1947, the Guardian had been under the care of an excellent doctor who saw him at least twice a year.

Shoghi Effendi had even consented to special treatments aimed at improving his general health and reducing his blood pressure.

The doctor often urged Shoghi Effendi not to overdo things when he returned to Haifa, to get more exercise, and especially more rest.

When he examined Shoghi Effendi, the doctor commented on his excellent health, had found Shoghi Effendi’s blood-pressure lower than it had been in years, and essentially gave the Guardian a clean bill of health.

This was six weeks before the Guardian passed away.

A July 1957 photograph of Trafalgar Square looking down Duncannon Street towards Charring Cross railway station with St Martin-in-the-Fields church on the left and South Africa House on the right, four months before Shoghi Effendi and Rúḥíyyih Khánum arrive in the city. Photograph by Alfred Teske. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Shoghi Effendi and Rúḥíyyih Khánum arrived in London on Sunday 20 October 1957, after their trip to mainland Europe that summer.

They were in London because the Guardian wanted to make final purchases for the interior furnishing of the International Bahá'í Archives before returning to Haifa.

The reason the Guardian chose London was because at the time, it was an internationally-renowned center for vintage and antique ornaments, with a bustling and diverse range of shops with treasure troves of unique and extraordinary pieces, unmatched in the entire world.

London was where Shoghi Effendi would purchase the most iconic objects in the International Bahá'í Archives, such as its Chinese and Japanese lacquer cabinets, and from where, for decades, he had ordered the very distinctive marble ornaments for his beloved gardens.

Shoghi Effendi’s plan was to stay in London for a few days to make the final purchases of his summer, then return to the Holy Land.

The Guardian was eager to return to Haifa and transfer the priceless, precious relics from the six rooms where they were stored into their newly-completed, permanent, and befitting home on Mount Carmel.

But then, both Shoghi Effendi and Rúḥíyyih Khánum caught the Asian flu.

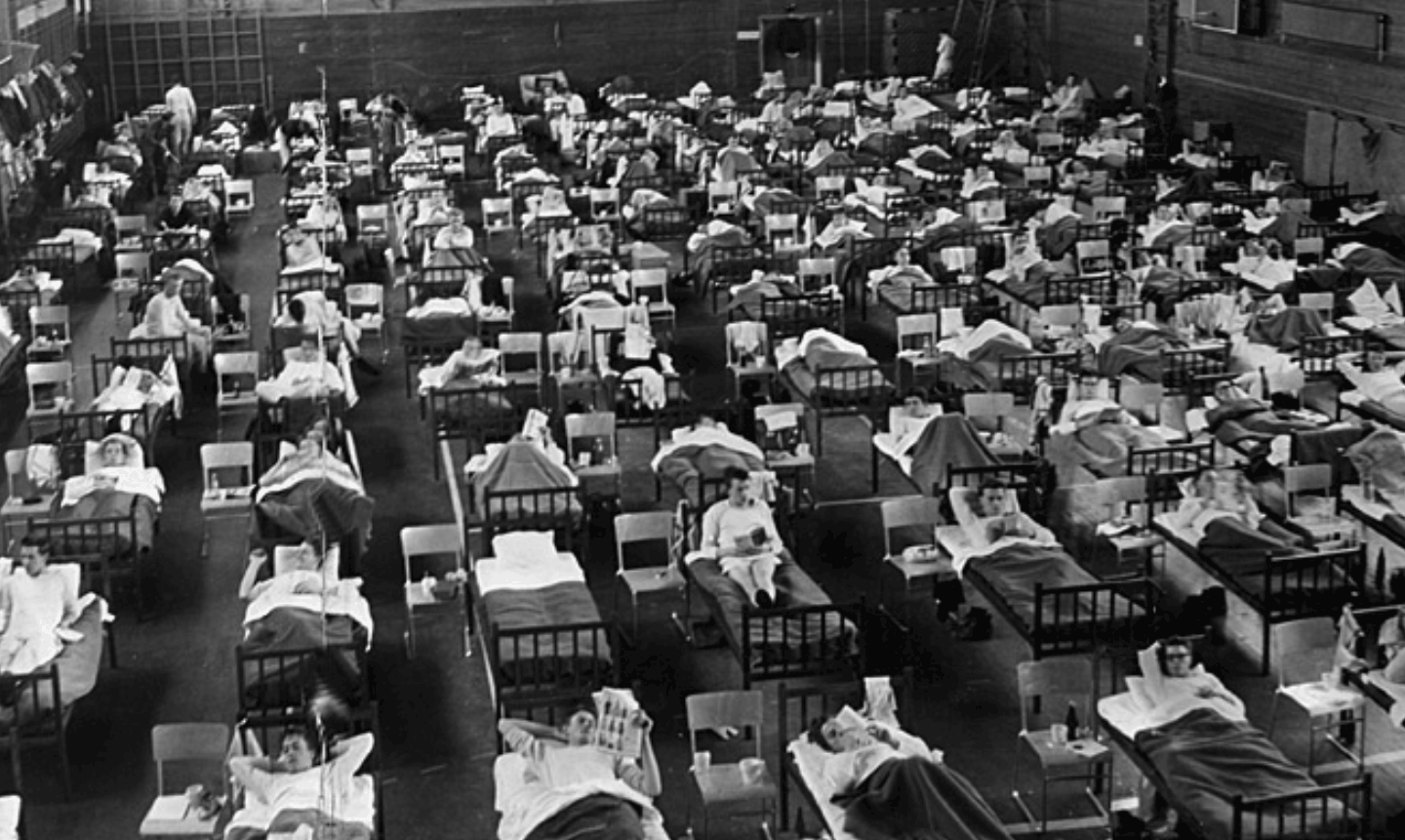

168 patients infected with Asian flu in a sports arena in Luleå, Sweden in 1957. Photograph by By Scanpix - dn.se, Public Domain. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

In late 1956 or early 1957, the first cases of a new influenza A virus subtype H2N2 broke out.

By the middle of March, the Asian flu had spread all over China.

On 17 April 1957, The Times reported it had spread to Hong Kong and infected thousands. By mid-May 1957, 680 people had died of the Asian Flu in Singapore.

The virus was spreading west fast.

By the end of May 1957, the outbreak had spread across Mainland Southeast Asia to Indonesia, the Philippines, Japan, and in Taiwan, 100,000 had caught it.

By June 1957, India suffered a million cases by June 1957.

It was in June 1957 that the Asian flu reached the United Kingdom.

The Asian flu of 1957 – 1958 is estimated to have killed between 1 and 4 million people worldwide, making it one of the deadliest pandemics in history.

An estimated 33,000 deaths in the United Kingdom were attributed to the flu outbreak.

The number of deaths in the United Kingdom peaked the week ending 17 October, with 600 reported in England and Wales.

“I feel so tired, so tired.” Background image: The neighborhood of Hampstead Rosslyn Hill in 1957, by Ben Brooksbank. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Starting on Thursday 24 October 1957, just 4 days after their arrival in London, Rúḥíyyih Khánum started having fevers, and was confined to bed.

Three days later, on Sunday afternoon, 27 October 1957, just a week after their arrival, Shoghi Effendi told Rúḥíyyih Khánum that he felt pain across the knuckles of both of his hands.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum asked Shoghi Effendi if he had any other pains, and he said no, just his fingers, which were stiff and caused him pain, adding:

I feel so tired, so tired.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum begged the Guardian to rest, and that, if he did not want to stay in bed, he should still try to rest quietly, because it was probably he was catching the Asian flu.

The Guardian began exhibiting symptoms of the Asian flu just 9 days after the height of the pandemic in England, in mid-October 1957.

By Monday 28 October 1957, the Guardian had a fever of 39 degrees Celsius—102.2 degrees Fahrenheit—and Rúḥíyyih Khánum successfully located an excellent doctor on Harley Street.

He immediately prescribed medication for the Guardian.

That evening, after work, the doctor returned and examined Shoghi Effendi very carefully. He listened to his heart and chest, took his temperature and pulse and diagnosed that both Shoghi Effendi and Rúḥíyyih Khánum had contracted the Asian flu.

The Guardian’s case was more severe, but still, both he and Rúḥíyyih Khánum worked through their illnesses.

A 1920s photograph of the House of ‘Abbúd, where Ásíyih Khánum, also known as Navváb, passed away in 1886. Her sudden passing caused Bahá'u'lláh to lose his appetite, the same condition Shoghi Effendi now finds himself in. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

For several weeks before and the week of his illness, the Guardian lost his appetite.

Several times, Shoghi Effendi told Rúḥíyyih Khánum:

I don't know what has happened to me.

I have completely lost my appetite.

I don't eat for twenty-four hours, but I still have absolutely no appetite whatever.

It is now weeks that I have been like this.

The same thing is happening to me that happened to Bahá'u'lláh when He lost His appetite after the death of Navváb.

“Do you realize that we have done nothing but work this week?” This picture shows us the interior of the receiving and dispatching room of the submarine cables at the Central Telegraph Office between 1897 and 1899. A nod to both how hard Shoghi Effendi and Rúḥíyyih Khánum have been working but also the type of work they have been doing, much of which was letter, cable and telegram-related. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

By Tuesday 29 October 1957, Rúḥíyyih Khánum had contracted bronchitis, a usual side effect of influenza—and the Asian flu of 1957—which causes coughing due to an inflammation of the airways of the lungs.

Still, the doctor felt that Rúḥíyyih Khánum had recovered enough to allow her to go run an important errand.

The doctor first examined the Guardian, then checked on Rúḥíyyih Khánum, then updated her on the Guardian’s condition, which allowed Rúḥíyyih Khánum to find out exactly how well the doctor felt he was progressing. Shoghi Effendi still had a very high temperature.

That day, they received a lot of mail, but because he had a fever, Rúḥíyyih Khánum persuaded the Guardian not to attend to it.

In the morning of Wednesday 30 October, the Guardian called for his mail and insisted on going over it personally, as he had always done, and he answered a large number of cables.

Shoghi Effendi and Rúḥíyyih Khánum worked all week, until the Guardian told her, towards the end of it:

Do you realize that we have done nothing but work this week?

Shoghi Effendi was anxious to leave London and return to Haifa.

But he was under the care of an excellent and meticulous doctor, and he told Shoghi Effendi frankly that if he did intend to leave London, he was free to call for another physician, because as long as he was the primary care doctor, he refused to give his consent to let Shoghi Effendi leave England until a week after his fever had fallen.

The doctor took a great liking to Shoghi Effendi and took very good care of him.

He came every day—usually staying for half an hour—and would sit with the Guardian, examining him thoroughly, and they would talk together.

One of these evenings, the doctor stayed an entire hour.

Every time the doctor came, he found Shoghi Effendi sitting in bed and reading, surrounded by papers, his briefcase by his side, and one day, he asked Rúḥíyyih Khánum privately what was the Guardian’s work? Rúḥíyyih Khánum replied that Shoghi Effendi was a religious leader and had many responsibilities.

The doctor had—as most people did—been charmed by the Guardian’s magnetic and lovable personality, and one night, before leaving, he turned to Rúḥíyyih Khánum and told her:

He was smiling tonight.

The doctor told the Guardian that on Friday 1 November, he was allowed to get up and sit in his armchair, for two reasons: a change from Shoghi Effendi’s sitting up in bed, and also in order to get his strength back.

But Shoghi Effendi preferred to work sitting in bed, and resting now and then.

In another heartbreaking fact that made his death so sudden and shocking, throughout the length of his illness, the Guardian had been well enough—even when he had a fever—to get up from bed every single day.

At no time during his flu was the Guardian in any way incapacitated, but it had left him weak and with almost no appetite.

There was absolutely no indication that he would die in the next 3 days.

None whatsoever.

Shoghi Effendi’s beloved map is finally finished. Source: Progress Bahá'í World Crusade 1953-1958, map by Shoghi Effendi, available on Bahá'í Library Online.

On Saturday morning 2 November 1957, the Guardian told Rúḥíyyih Khánum that he wanted a large table placed in his room, big enough so that he could lay on it his final masterpiece of a map: The Half-Way Point of the Ten-Year Crusade, showing the progress of the Ten Year Crusade at its midway point in 1958, five years into it with five more years to go.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum protested with the Guardian, and begged him not to work.

She said that in a few days he would be stronger, and he could finish his map then.

The Guardian replied:

No, I must finish it; it is worrying me. There is nothing left to do but check it. I have one or two names to add that I have found in this mail, and I will finish it today.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum had two small mahogany tables drawn together to create the large surface area the Guardian needed.

The Guardian stood in front of the large table and worked on his map for 3 hours.

The table was covered with scattered pencils, a penknife, an eraser, rulers and a compass and the Guardian’s enormous statistical booklet of languages, tribes, countries, Temples, Ḥaẓíratu’l-Quds, work completed, ongoing work, completed work.

The booklet had doubled in size since the last time he had worked on a map in 1952.

Shoghi Effendi told Rúḥíyyih Khánum he wanted her to carefully check the data with him, and he stated that, apart from adding a few extra details, and cross-checking what was on the map with his various lists, the work was finished.

The Guardian’s map was done.

On the very first day the Guardian began working on his last map in September 1957, he was ill.

And the Guardian was ill again, on the last day he ever worked on this very same map.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum was the one to make this parallel, and elevate our understanding of the Guardian’s last act by helping us see it through the lens of sacrifice:

…indeed it seems a strange coincidence that the first time and the last time he worked on [the map] should both have been occasions on which he was ill, symbolic of the great sacrifice of his life and strength that went into the conception and prosecution of the World Crusade.

“Who is going to go back and do all these things? I have no strength left. I am like a broken reed. I can't do anything more. I have no spirit left to do anything more.” Background photo by Xuan Nguyen on Unsplash.

After working on his map for 3 hours that afternoon, the Guardian looked tired.

He returned to bed, and sitting up, continued reading the many reports he had received. He ate only a mouthful at lunch and refused dinner.

The Guardian was very, very sad and depressed when speaking to Rúḥíyyih Khánum about his winter plans in the Holy Land that evening, saying:

Who is going to go back and do all these things? I have no strength left. I am like a broken reed. I can't do anything more. I have no spirit left to do anything more. Now we will be going back—who is going to go up that mountain and make all those plans and stand for hours and supervise the work? I can't do it. And I am not going to do anything about the houses in Bahjí. Let them stay like that until I see how I feel. And I am not going to furnish the inside of the Archives this winter. It can wait another year, until everything that is needed to furnish it is collected. I shall just see the pilgrims and stay in my room and rest and do the few things that I have to do. I am not even going to take the telegrams back from Jessie and make copies of them and keep all the receipts the way I have done all these years. She did this in the summer, she can go on doing it in the winter. I am too tired.

The Guardian went on speaking like this for a long time on the evening of 2 November.

The plans the Guardian was discussing with Rúḥíyyih Khánum were plans he had made several months before and enthusiastically discussed with her many times over the last few months.

They included working in the gardens above the International Bahá'í Archives, furnishing the Archives, personally overseeing the demolition of the last remaining Covenant-breakers’ house at Bahjí, using that rubble to extend the gardens around the Ḥaram-i-Aqdas.

It was not the first time that Rúḥíyyih Khánum had heard the Guardian speak words infused with sadness, but that evening, he spoke to her with far greater intensity, and in much more specific detail than she had ever heard him speak before.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum was deeply distressed.

“I like him very much. He is a fine man, and a good doctor.” Cropped image from a The Doctor (1891), an oil on canvas painting by Luke Fildes, showing a caring physician looking over his ill patient, a young girl, with a worried parent looking on. Painting was cropped to focus on the good doctor. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

That evening, when the doctor made his house call, he was satisfied with the progress in the Guardian’s health and said Shoghi Effendi could certainly leave England on Tuesday morning, 5 November. He also told Shoghi Effendi he could go out and get some fresh air if he wanted. They spoke together for a while, discussing the news on the radio that day that announced 200 people had died of the Asian flu.

When the doctor left that night, after staying quite a while, the Guardian had said he didn’t need to come the next day, Sunday, which was the doctor’s day of rest.

After he left, the Guardian said:

I like him very much. He is a fine man, and a good doctor.

That evening, Rúḥíyyih Khánum did not sleep well. She lay awake for hours, unable to go back to sleep. She had no inkling or premonition of what was about to happen, but her heart was heavy and sad, no doubt at the Guardian’s immense emotional pain, which she had witnessed that night.

A letter or postscript to a letter in Shoghi Effendi’s own handwriting. Source: The Bahá'í Faith: The official website of the worldwide Bahá'í community: Shoghi Effendi – The Guardian of the Bahá'í Faith: Guidance and Translations.

On Sunday 3 November 1957, the Guardian added his usual postscripts to the letters which Rúḥíyyih Khánum had written, he looked over some of his other matters, dictated instructions for Rúḥíyyih Khánum to mail, and told her to write two additional letters that afternoon.

The Guardian remained in his room, reading his papers in bed or attending to matters at his desk. He read the letters that Rúḥíyyih Khánum had typed and added a postscript to one of the letters. The Guardian became deeply upset about one of the reports he was reading.

The report spoke about Covenant-breaking.

Shoghi Effendi had updated Rúḥíyyih Khánum several times over the course of the last few days on news regarding recent Covenant-breakers, and the subject never failed to greatly distress the Guardian.

It is simply heart-breaking to think that Covenant-breaking plagued our beloved Guardian from the moment He began his ministry until the very last day of his Guardianship.

Although they had agreed there was no need for the doctor to visit that day, he still called to ask about Shoghi Effendi’s health. Rúḥíyyih Khánum answered the phone, standing beside Shoghi Effendi’s bed.

The doctor said he was willing to come if he was needed, but Rúḥíyyih Khánum conveyed a message on the part of Shoghi Effendi saying that he felt better, and that there was no need for him to come.

They then agreed that the doctor would make his last call to Shoghi Effendi the following afternoon, Monday 4 November 1957.

By then, the Guardian would be no more.

“Stay a little while longer and talk.” Hand of the Cause Amatu’l-Bahá Ruḥíyyíh Khánum representing the Guardian at 1953 Wilmette Intercontinental Teaching Conference. Source: Bahaimedia.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum sat in the Guardian’s room and they talked for a while about everyday things, then, at 9:30 PM, she asked Shoghi Effendi if he wanted to go to sleep, as she was sure he was tired. Shoghi Effendi asked her:

What time is it?

Nine-thirty.

Then Shoghi Effendi said:

It is too early to go to sleep now; if I go to sleep now I shall wake up early and then I won't be able to go to sleep again. Stay a little while longer and talk.

Thirty minutes later, at around 10 PM, Rúḥíyyih Khánum asked him if he wanted to go to sleep now, and the Guardian answered yes. Rúḥíyyih Khánum did a few last things to make him comfortable, and after saying goodnight, she asked the Guardian to be sure and call her in the night if he needed anything.

For the second night in a row, Rúḥíyyih Khánum suffered insomnia. Her heart still heavy.

It was the last Rúḥíyyih Khánum ever spoke to the Guardian.

On the morning of Monday, 4 November 1957, Rúḥíyyih Khánum went to the door of the Guardian’s room, knocked gently, and, when she received no answer, entered.

The curtains were drawn over the windows and the room was in twilight.

She saw the beloved Guardian lying on his left side facing her, with his left hand folded over towards his right shoulder and his right arm over his left one, looking relaxed and comfortable.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum asked the Guardian how he had slept, and if he felt better.

When Shoghi Effendi neither moved nor replied, and seemed unnaturally still, Rúḥíyyih Khánum felt a wave of agonizing terror sweep over her.

The Guardian had passed away hours ago, in the middle of the night, gently and serenely.

Within two minutes of discovering Shoghi Effendi had passed away, Rúḥíyyih Khánum had called his doctor at the hospital and begged him to come immediately in case there was still something to be done.

The doctor arrived immediately, and then a second physician arrived and confirmed death.

Shoghi Effendi had completely recovered from the Asian flu.

That was not what had taken our Guardian from us.

The Guardian’s official cause of death was coronary thrombosis—a blood clot in the blood vessels or arteries of the heart that causes an immediate heart attack.

Nothing in the world could have saved the Guardian's life, not even if all of the world’s best doctors and physicians had been standing right by his side.

Striking similarities in the gentle and dignified deaths of Bahá'u'lláh, 'Abdu'l-Bahá and their great-grandson and grandson, Shoghi Effendi, Guardian of the Bahá'í Faith. Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh from Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023. Design concept for the future Shrine of 'Abdu'l-Bahá from Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023. Monument at the resting place of Shoghi Effendi from Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

On Saturday 29 May 1892, at 3:00 AM, Bahá'u'lláh gently passed away, 8 hours after sunset, at the age of 75, in His own bed in the Mansion of Bahjí, with no sign of the fever that had troubled him for 3 weeks. His Spirit had winged its way to the next world.

29 years later, on Monday 28 November 1921, 'Abdu'l-Bahá awoke at 1:15 AM, rose from bed, walked across His room to a table, drank a glass of water, returned to bed after saying He was too warm, drank a little bit of rose water, sweetly chided his daughters for asking Him if He wanted to eat, closed his eyes, and passed away less than a minute later. 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s face was so serene, so peaceful, so calm, His daughters did not even realize He had passed away.

And on 4 November 1957—65 years after Bahá'u'lláh and 36 years after 'Abdu'l-Bahá—Shoghi Effendi too, passed away in a painless, peaceful, calm, and dignified way.

And like Great-grandfather and his Grandfather before him, the Guardian died in the middle of the night.

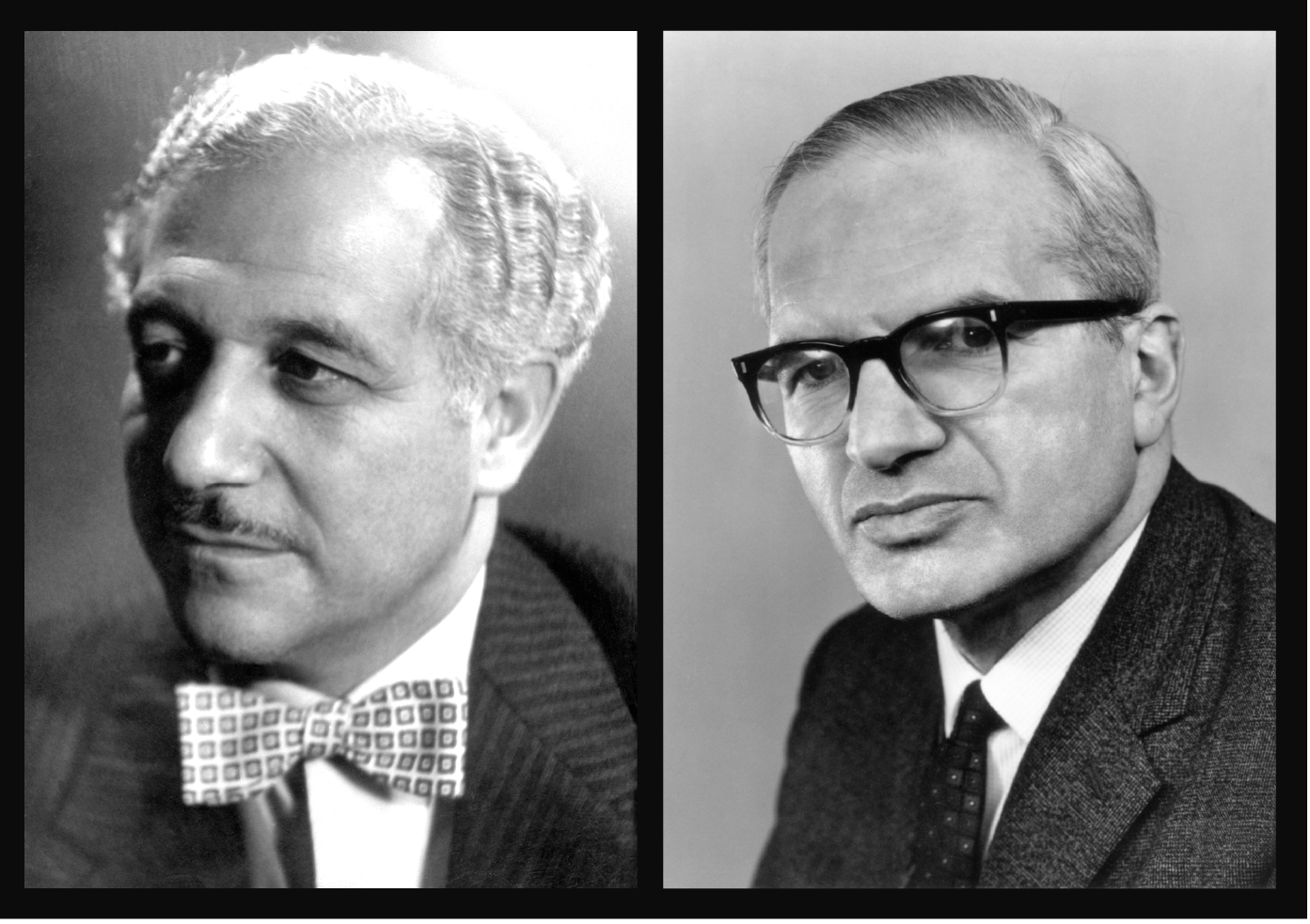

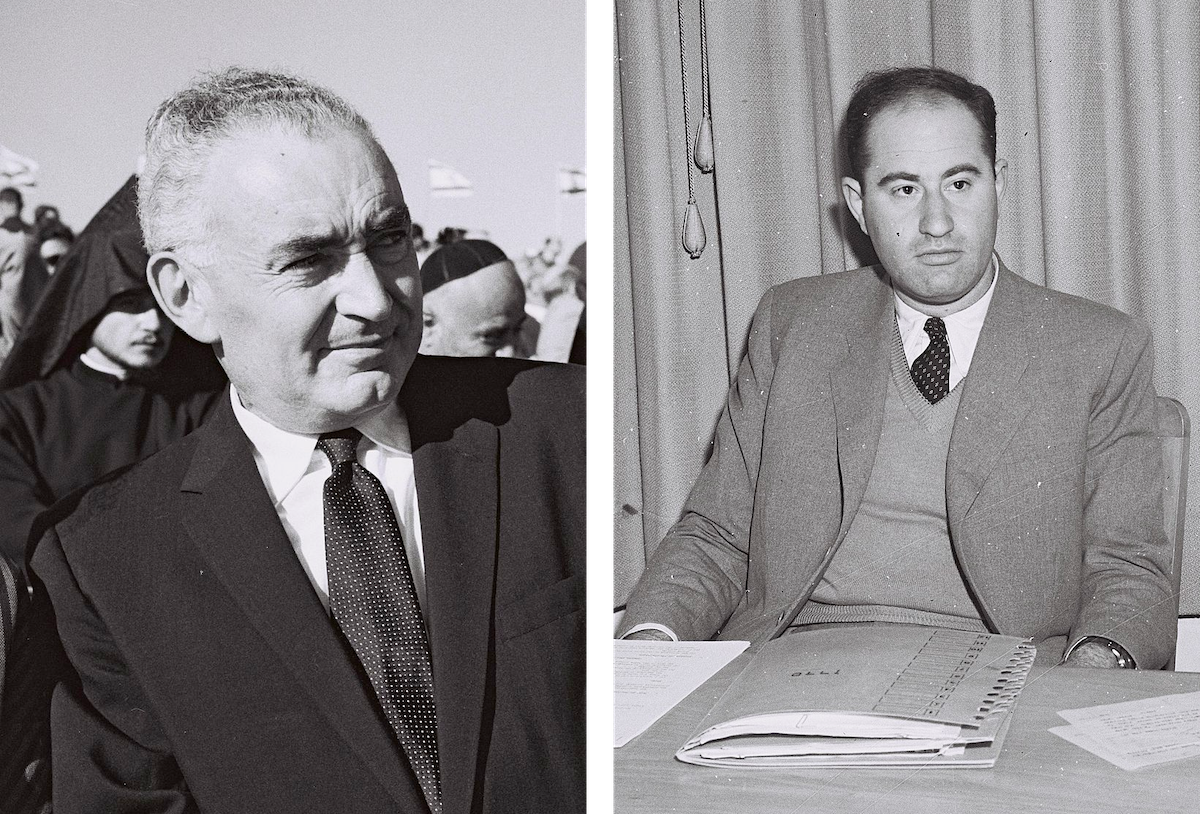

Hands of the Cause Ḥasan Balyúzí and John Ferrraby, both appointed in the Guardian’s third contingent of Hands of the Cause on 2 October 1957, exactly one month before his sudden passing. Photographs from Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum was half-mad herself with grief, in her own words.

She had suddenly, in the space of a few hours, lost her beloved Guardian, and become a widow.

Yet despite her intense personal trauma, Hand of the Cause Amatu’l-Bahá Rúḥíyyih Khánum found it within herself to find a way of conveying this devastating news to all the Bahá'ís of the world.

But before this, Rúḥíyyih Khánum immediately informed all the Hands of the Cause.

As she was in London, she summoned Ḥasan Balyúzí, who had been appointed a Hand of the Cause only one month before, and was by her side within the hour.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum then contacted Hand of the Cause John Ferraby, also newly-appointed and also in London, she enjoined him to silence and asked him to come quickly.

Hand of the Cause Ugo Giachery, appointed by the Guardian as part of the first contingent of Hands of the Cause in 23 December 1951. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

Monday 4 November was a national holiday in Italy, the annual National Unity and Armed Forces Day, and Hand of the Cause Ugo Giachery was at home in Rome.

At 2:10 PM, the phone rang, and Ugo Giachery heard the operator tell him to stand by for a long-distance connection.

Five minutes later, at 2:15 PM, Ugo Giachery heard the voice of Rúḥíyyih Khánum calling from London.

The first words Ugo Giachery heard Rúḥíyyih Khánum speak were:

The Guardian is dead!

Two hours later, Ugo Giachery caught the next plane from Rome to London and arrived at 8 PM on the same day as the Guardian had passed away.

The first cable. Photo by Priyanka Karmakar on Unsplash.

The Guardian’s passing was so sudden that Rúḥíyyih Khánum and the Hands of the Cause decided to break it to the Bahá'í world in two gentle stages, rather than inform them bluntly that their Guardian had died.

The other consideration in breaking the news slowly was a delicate attention to preparing the hearts of the most vulnerable of the Guardian's lovers: the sick, the elderly, and the feeble who would have suffered greatly upon hearing the news in a single cable.

The first cable the Bahá'ís of the world received was that Shoghi Effendi would inform them that Shoghi Effendi was seriously ill. Rúḥíyyih Khánum’s instructions to Hand of the Cause Leroy Ioas regarding the content of this first cable were the following:

Beloved Guardian desperately ill Asiatic flu tell Leroy inform all National Assemblies inform believers supplicate prayers divine protection Faith.

This first cable was preparing the Bahá'ís to receive the full blow of the second cable.

Hand of the Cause Leroy Ioas, appointed by the Guardian as part of the first contingent of Hands of the Cause in 23 December 1951. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

It was 5 PM in London and 7 PM in Haifa on Monday 4 November when Rúḥíyyih Khánum called the Hands of the Cause in the Holy Land to inform them of the passing of the Guardian.

No one in Haifa had yet received Rúḥíyyih Khánum’s first cable.

Hand of the Cause Leroy Ioas answered the phone and Rúḥíyyih Khánum told him that the Guardian had died early that morning in his sleep.

Sylvia Ioas, Leroy’s wife, heard him fall to the floor and ran to him but he was already getting up, and continued the terrible conversation.

For Leroy and Sylvia, it was as if their world had suddenly gone dark and empty.

Hand of the Cause Amelia Collins had just arrived the day before on Sunday 3 November 1957, to be sure she was in Haifa when Shoghi Effendi returned.

Feeling lost and alone, Sylvia and Leroy went over to Amelia Collins, whom they had just left an hour before so she could rest. Leroy Ioas told Amelia Collins as sweetly and gently as he could, but Amelia saw their stricken faces. She laid her head on Leroy Ioas’s shoulder and cried and cried.

Amelia’s strength and fortitude overcame her grief and she repeated, over and over again, God will give me strength; God will give me strength.

“The only Bahá’í we had in the world had died.” Photo by Karina Vorozheeva on Unsplash

Rúḥíyyih Khánum had made the decision to inform the Bahá'í world gradually about the Guardian’s passing, a news she herself had endured the full blow of, along with the three Hands of the Cause at her side: Ḥasan Balyúzí, John Ferraby and Ugo Giachery.

In her great kindness, she did not want to unleash that cataclysm on the Bahá'ís of the world in a single cable. Her first cable had prepared them.

Then, later in the day, Rúḥíyyih Khánum sent a second cable to Haifa asking it be sent to all National Spiritual Assemblies in the morning of Tuesday 5 November 1957.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum felt the announcement of the Guardian’s death should come from the World Center of the Faith:

Shoghi Effendi beloved of all hearts sacred trust given believers by Master passed away sudden heart attack in sleep following Asiatic flu stop urge believers remain steadfast cling Institution Hands lovingly reared recently reinforced emphasized by beloved Guardian stop only oneness heart oneness purpose can befittingly testify loyalty all National Assemblies believers departed Guardian who sacrificed self utterly for service faith. Rúḥíyyih.

On the first day of the All-India Teaching Conference, in October 1964, Rúḥíyyih Khánum told the assembled Bahá'ís exactly what her reaction had been after the passing of the Guardian:

When our beloved Shoghi Effendi died in 1957, I said that the only Bahá’í we had in the world had died.

The Guardian’s home and office at 7, Haparsim, the House of the Master, safeguarded by the Hands of the Cause in the Holy Land immediately upon hearing of the passing of the Guardian. Original color photograph from Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

During their phone conversation, Rúḥíyyih Khánum and Leroy Ioas decided that Leroy would secure the Guardian’s home and office, and inform the authorities about the Guardian’s passing.

Leroy Ioas, Sylvia Ioas, Ethel Revell, and Jessie Revell—four members of the International Bahá'í Council—could not enter the Guardian’s apartment or office, as he had locked them himself so they sealed them off with padlocked iron bars, and placed the keys to the padlocks in a signed and sealed envelope with their statements.

Leroy Ioas arranged for two trusted Bahá'ís to sleep in front of the Guardian’s apartment and office, and at the foot of the staircase so that no one could gain access to the area.

Leroy Ioas also took precautions to safeguard the Holy Places.

Several additional Bahá'ís were stationed at the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh, the Mansion of Bahjí, and the Shrine of the Báb to ensure no one would enter, and all three Holy Places were guarded day and night, with one Bahá'í sleeping inside each Holy Place every night.

At 11 PM that evening, Leroy, Sylvia, and Amelia walked up to the Shrine of the Báb and said many, many prayers. The intense state of prayer was the comforted they wanted and needed.

Then, before midnight, Leroy and Sylvia sent a touching condolence cable to Rúḥíyyih Khánum:

In Guardian's passing whole Bahá'í world grieved crushed but your personal loss insurmountable. Sylvia myself send deepfelt sympathy love admiration your strong determination assist his released spirit gain even greater victories beloved Faith.

Early the next morning on Tuesday 5 November 1957, Leroy drove Amelia Collins to the airport where she boarded a flight to London to be with Rúḥíyyih Khánum, to whom she had become like a mother.

Amelia Collins’ presence would be an immense comfort and precious support for the grieving Rúḥíyyih Khánum.

An aerial photograph of London, showing the vastness of the city, and the arduousness of the task of finding a befitting resting place for the Guardian. Photogrpah by Marek Ślusarczyk (Tupungato) on www.microstock.pl. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Basil Leverton was the funeral director in charge of the arrangements for Shoghi Effendi’s interment. Rúḥíyyih Khánum explained to Mr. Leverton the laws of Bahá'í burial, including that only a Bahá'í could perform the burial ceremony and letting him know she would make the arrangements personally.

The Hands of the Cause wanted to transfer the Guardian’s remains to the National Bahá'í Center in order to attend to all the funeral matters in the most efficient way possible, but London was so vast they found they could not do this, as it would have made it impossible to find a burial ground at less than an hour’s distance—an essential requirement of Bahá'í burial—within the center of London.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum was confident that Hand of the Cause Dr. Adelbert Mühlschlegel was the perfect person to prepare the Guardian’s body for his funeral: Dr. Mühlschlegel was a physician, as a Hand of the Cause, and a man known for his great spirituality.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum called Dr. Mühlschlegel in Stuttgart on Tuesday 5 November, and informed him of her decision. Dr. Mühlschlegel accepted immediately and he and Hand of the Cause Hermann Grossmann flew from Germany to London, arriving at the National Bahá'í Center that very evening.

Originally, the Hands of the Cause had planned to inter Shoghi Effendi on Friday 8 November.

This proved to be very complicated because they needed an additional business day to accomplish everything they needed to do before the funeral which included not only purchasing a piece of land for the resting place for the Guardian but also constructing a suitable vault.

The Hands of the Cause decided to move the Guardian’s funeral to Saturday 9 November instead.

New Southgate Cemetery—London’s Great Northern Cemetery at the time of the Guardian’s funeral, with a view on the chapel in which the funeral service of Shoghi Effendi took place. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The most urgent priority for Rúḥíyyih Khánum and the Hands of the Cause was to find a befitting burial place for the Guardian’s remains.

They needed more than a grave.

They needed a plot of land on which they could erect a monument, and this, at first, proved impossible.

Hand of the Cause John Ferraby met with the Home Office—the British Minister of the Interior—and was informed that British law prohibited the purchase of land near London for burials.

On that rainy afternoon, Rúḥíyyih Khánum, Ḥasan Balyúzí, and Ugo Giachery were taken out to inspect all possible sites for the Guardian’s grave in cemeteries within an hour's journey from London.

The Hand of the Cause visited a first plot, but it was directly across from the depressing vault of a member of the British nobility, too close to the main entrance of the cemetery, and prohibitively expensive.

It was unbefitting and out of the question.

A few minutes before 4:30 PM, Hands of the Cause Rúḥíyyih Khánum, Ugo Giachery, and Ḥasan Balyúzí arrived at the second cemetery, the Great Northern Cemetery—now called New Southgate Cemetery—due north of the center of London.

The Great Northern Cemetery was a 22-hectare cemetery in Brunswick Park in the London Borough of Barnet, and had been established by the Colney Hatch Company in the 1850s.

The Hands of the Cause were pleasantly surprised to find themselves in a beautiful, peaceful spot on a hill, surrounded by rolling country, where birds sang in the trees.

The cemetery Superintendent, Mr. Stanley, escorted them to the best piece of land he had, 30 square meters (almost 100 square feet) in the very center and at the highest point of the cemetery.

The plot was along one of the small cemetery avenues and was bordered by great trees, casting their shade over the spot.

It was absolutely perfect in every way.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum made arrangements to purchase it immediately, and gave instructions to build a strong, deep vault on the plot.

Portrait of Basil Leverton, the funeral director, who was responsible for organizing the funeral of the Guardian. Photograph © Levertons funeral directors, all rights reserved, used with permission.

By dusk, Rúḥíyyih Khánum and the Hands of the Cause had left the Great Northern Cemetery and were on their way to the office of Basil Leverton, the funeral director of Levertons Funeral Home. Mr. Leverton helped to plan the Guardian’s funeral, and he was assisted in this task by his brother Ivor and his nephew Keith.

Basil Leverton helped Rúḥíyyih Khánum and the Hands of the Cause with the heartbreaking task of selecting a befitting casket for their beloved Guardian.

After a long consultation, they all agreed the Guardian should be buried in a dark, polished bronze casket, the most dignified, the most expensive and the most enduring they could find.

The Hands of the Cause ordered a bronze plate to be placed on the upper lid of the casket which would be inscribed. They promised Mr. Leverton they would communicate to him the text of the inscription on the following day, Wednesday 6 November.

Hand of the Cause Amelia Collins arrived in London from Haifa on Tuesday night to be by Rúḥíyyih Khánum’s side. Amelia Collins had lived in Haifa for the last six years and had become a second mother to Rúḥíyyih Khánum. Her arrival in London was a great source of comfort to the grieving and heart-broken Rúḥíyyih Khánum.

Amelia Collins had brought with her. flowers from the Holy Threshold of the Shrine of the Báb.

By the end of the night on Tuesday 5 November 1957, Amelia Collins, as well as every single European Hand of the Cause, were in London and by Rúḥíyyih Khánum’s side in her time of devastating loss.

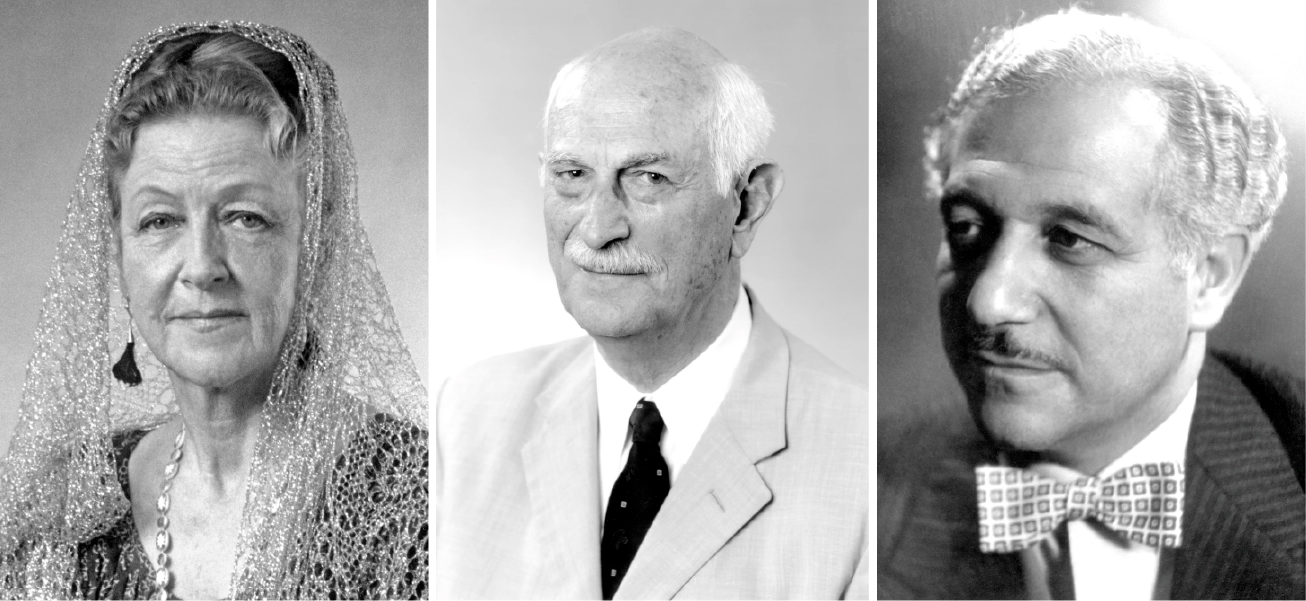

From left to right: Hands of the Cause Amatu’l-Bahá Ruḥíyyíh Khánum, Ugo Giachery, and Ḥasan Balyúzí made the official declaration of the passing of Shoghi Effendi with the Leverton funeral home. All images Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

On Wednesday 6 November, the National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá'ís of the British Isles communicated to all the believers in their country the heart-breaking news of the passing of the beloved Guardian.

The Bahá'ís of the British Isles, as members of the community in which this great calamity had occurred, were invited to be present at the funeral of Shoghi Effendi in London.

On the afternoon of Wednesday 6 November, Rúḥíyyih Khánum and Amelia Collins drove out to the Great Northern Cemetery and made arrangements with a florist in the neighborhood for the decoration of the Chapel and for the sheath of flowers which was to cover the casket.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum needed a very important and crucial piece of information before the Guardian’s funeral could take place. It was the law in England that a death must be registered at the register office by a relative in the days immediately following.

That same afternoon, Basil Leverton, the funeral director, accompanied Hands of the Cause Rúḥíyyih Khánum, Ugo Giachery, and Ḥasan Balyúzí to make the official declaration of the passing of Shoghi Effendi. They were immediately issued with a certificate of death and now Mr. Leverton had the necessary certificate for burial to proceed.

The Iranian Hands of the Cause, Dhikru’lláh Khadem, Abu’l-Qásim Faizi arrived in London in the evening of Wednesday 6 November.

Hand of the Cause Dr. Adelbert Mühlschlegel, handpicked by Amatu’l-Bahá Ruḥíyyíh Khánum for the signal honor of preparing the Guardian’s blessed body for burial. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

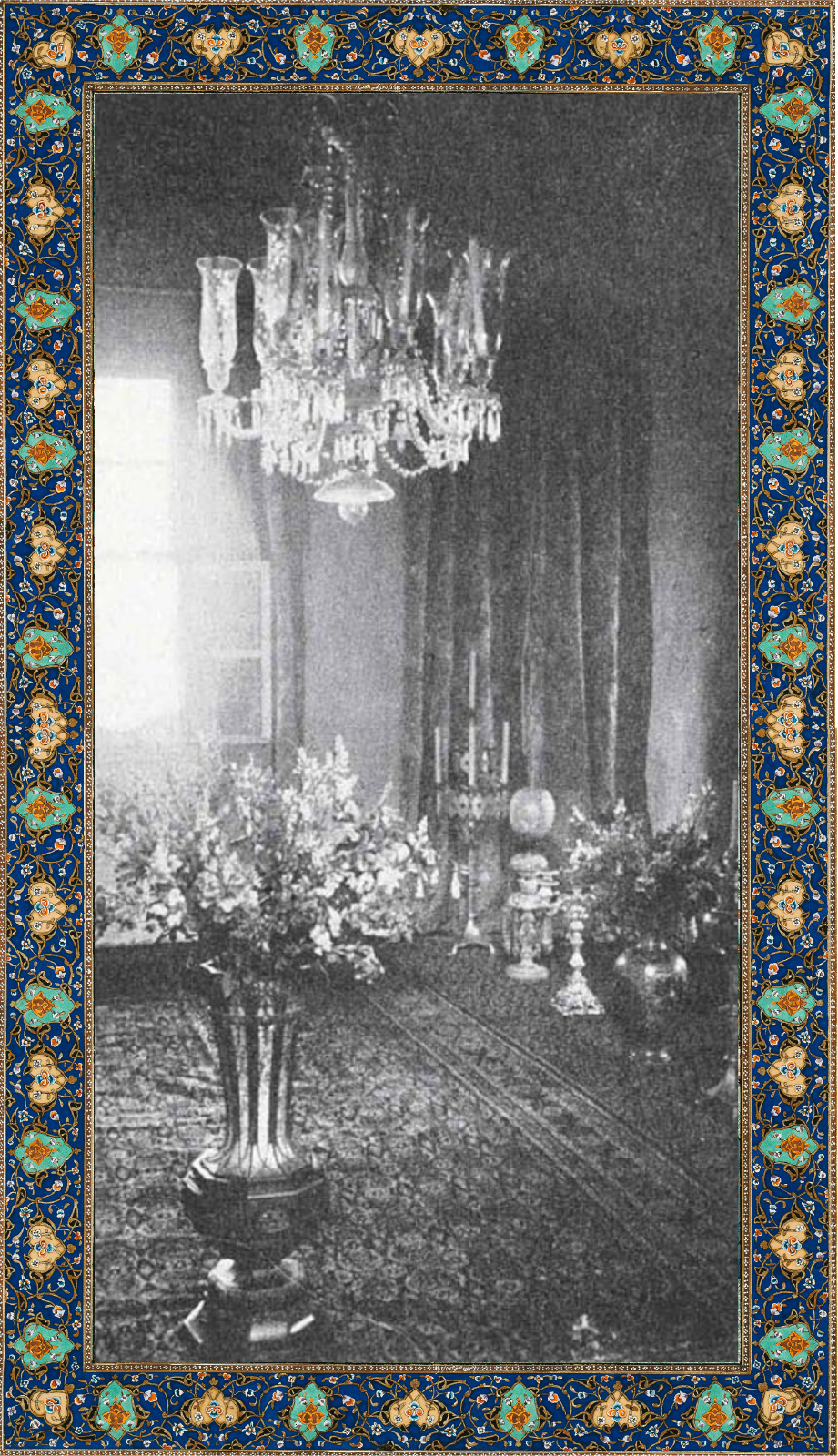

The next day, on Thursday 7 November 1957, Rúḥíyyih Khánum and Amelia Collins continued to make floral arrangements. They ordered the flowers for the Chapel at the cemetery, and for the floral blanket of roses, gardenias and lilies of the valley—Shoghi Effendi’s favorite flower—to be placed on the casket.

At 2 PM, Hands of the Cause Rúḥíyyih Khánum and Dr. Adelbert Mühlschlegel drove to the place where the Guardian’s casket was held.

When they arrived, Rúḥíyyih Khánum sat in the waiting room while Dr. Mühlschlegel performed the burial ceremony.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum would wait for an hour and a half.

“He was our Guardian, King of the world. Background photo by Simone Dalmeri on Unsplash.

Once Dr. Adelbert Mühlschlegel had completed the burial ceremony, Rúḥíyyih Khánum asked him for a moment alone with the beloved Guardian so she could say her own last farewell.

Afterwards, though she never spoke of this moment to another soul, Rúḥíyyih Khánum would tell the Bahá'ís:

He was our Guardian, King of the world. We know he was noble because he was our Guardian. We know that God gave him peace in the end. But as I looked at him all I could think of was—how beautiful he is, how beautiful! A celestial beauty seemed to be poured over him and to rest on him and stream from him like a mighty benediction from on high. And the wonderful hands, so like the hands of Bahá'u'lláh, lay softly by his side; it seemed impossible the life had gone from them—or from that radiant face.

White asters and lavender chrysanthemums, the flowers that cascaded down inside the church at the cemetery for the funeral of the beloved Guardian. Photos from Google.

Friday 8 November 1957 was just 4 days after Shoghi Effendi’s passing and the day before his funeral.

Throughout the day, in a room filled with flowers, Hands of the Cause from Iran, Europe, Africa, and America prayed, keeping vigil near the casket of their beloved Guardian.

At the top of the non-denominational Chapel was an arched alcove filled with a bank of lavender chrysanthemums and white asters, beginning with deep shades of purple and running up through violet, then lavender to white at the top.

Like two arms reaching out, garlands of lavender chrysanthemums ran along a cornice which framed the raised upper part of the Chapel. Above this, from wall to wall, was a beam of wood, in the centre of which a framed Greatest Name was hung.

Beneath this, in front of the alcove of flowers, the casket was to rest on a low raised platform covered by a rich green velvet cloth, the color to which the direct lineal descendants of Muhammad are entitled by their illustrious lineage.

Being descended from the family of the Báb, the Guardian was himself a Siyyid, and the green cloth, to which he was entitled by birthright, was an acknowledgement of his kinship with the Báb.

Seating arrangements were made for the following day, placing the Hands of the Cause on the right and on the left side of the casket, facing it. 100 more chairs had to be ordered as the Chapel normally only seated about 80 people.

On Friday evening, Rúḥíyyih Khánum and Amelia Collins drove out to the cemetery to inspect the Chapel and the grave.

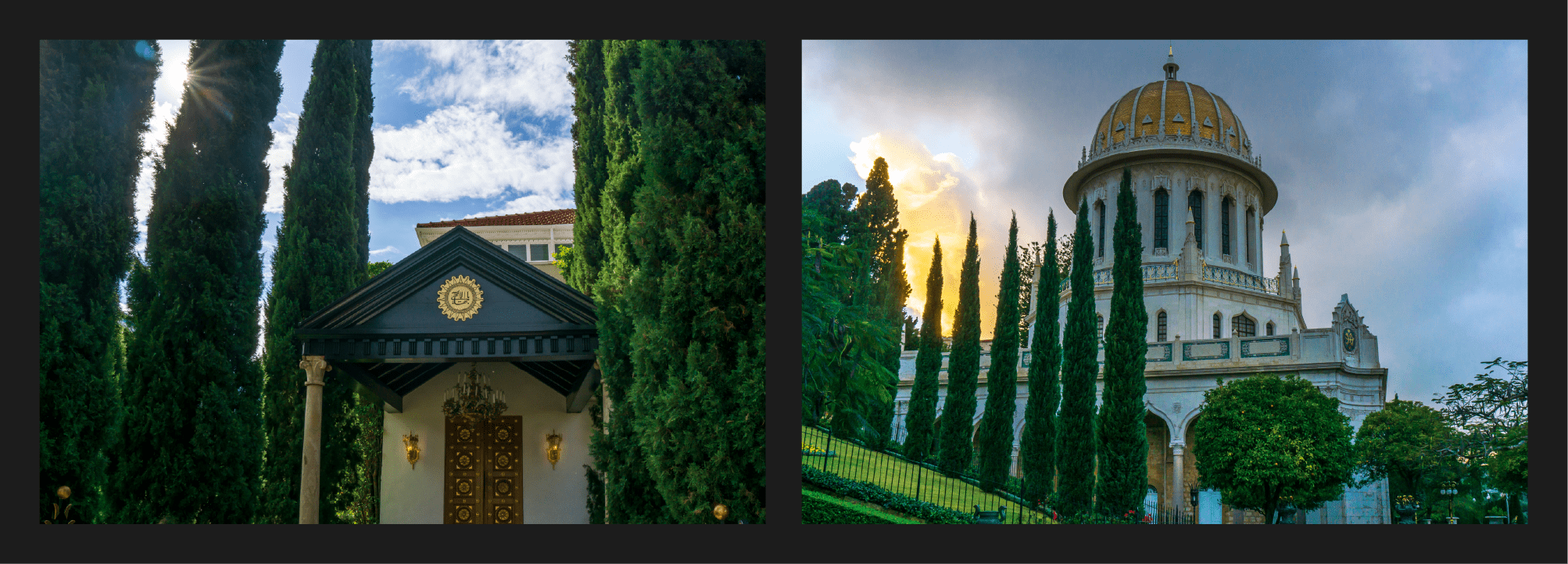

Shoghi Effendi’s beloved cypresses, straight and stately, standing guard over the Shrines of Bahá'u'lláh and the Báb. Both photographs by Farzam Sabetian at Luminous Spot.

The florist was following his instructions very carefully and making every effort to create an atmosphere of beauty worthy of this sacred occasion.

In fact, everyone concerned with the death of and the funeral arrangements made for the Guardian—to them a stranger who had very suddenly passed away in their country—seemed deeply touched and stirred by what Rúḥíyyih Khánum called “the great reverence and love that accompanied the still form of God's Great Guardian as he passed from life to the grave. They outdid themselves in showing sympathy and co-operation.”

At each one of the four corners of the resting place of the Guardian, the florist had a beautiful, small, cypress tree. Rúḥíyyih Khánum had ordered the trees in memory of the hundreds of cypress trees that the beloved Guardian had planted, during his lifetime, around the Holy Places in Bahjí and Haifa.

Cypress trees also carried a connection between Bahá'u'lláh, 'Abdu'l-Bahá, and Shoghi Effendi that centered around the Shrine of the Báb. It was in a circle of 15 cypress saplings that Bahá'u'lláh indicated to the Master the place where He should build the Shrine of the Báb, which he completed 18 years later. It was in that same spot that Shoghi Effendi constructed the magnificent superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb.

Eliahu Elath, the Israeli ambassador to the United Kingdom, Source: Wikimedia Commons. Gershon Avner, the Ambassador’s representative at the Guardian’s funeral. Mr. Avner was the only person in attendance not to be a Bahá'í. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

On Friday 8 November 1957, the Guardian’s sealed casket—with the affixed bronze plaque in the center of the lid—was delivered to the chapel of Basil Leverton’s funeral home, where it was banked with flowers.

Hands of the Cause took turn keeping vigil over the Guardian’s casket the entire day, never leaving the Guardian alone.

Final arrangements were made for Saturday’s massive funeral cortege.

The afternoon of Friday 8 November was spent coordinating and arranging the logistics of flying all the Hands of the Cause in London back to Haifa for their conclave in 10 days, which would start on Monday 18 November 1957.

The Hands of the Cause, upon consulting, had made the decision to keep the Guardian’s funeral a private event. The elements they had considered in their consultation were the depth of the Bahá'ís’ grief, the short time available, and the restricted space at the Great Northern Cemetery Chapel.

The Israeli Government, however, made a spontaneous gesture of paying homage to the Guardian by sending their representative, Gershon Avner, to attend the Guardian’s funeral.

The Israeli Government would have sent their Ambassador, Eliahu Elath, but he was absent from England at the time.

Gershon Avner would be the only person to attend the Guardian’s funeral not to be a Bahá'í.

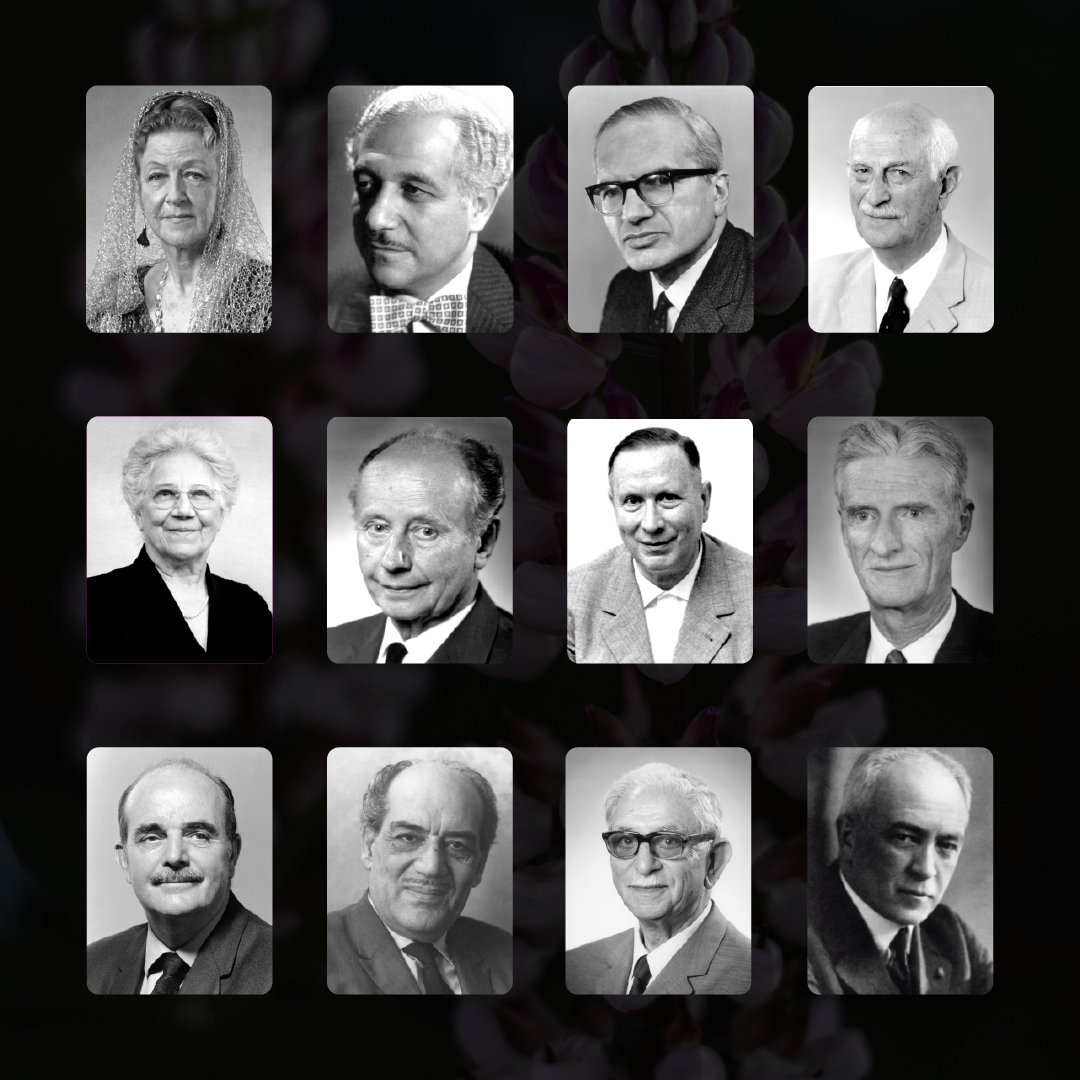

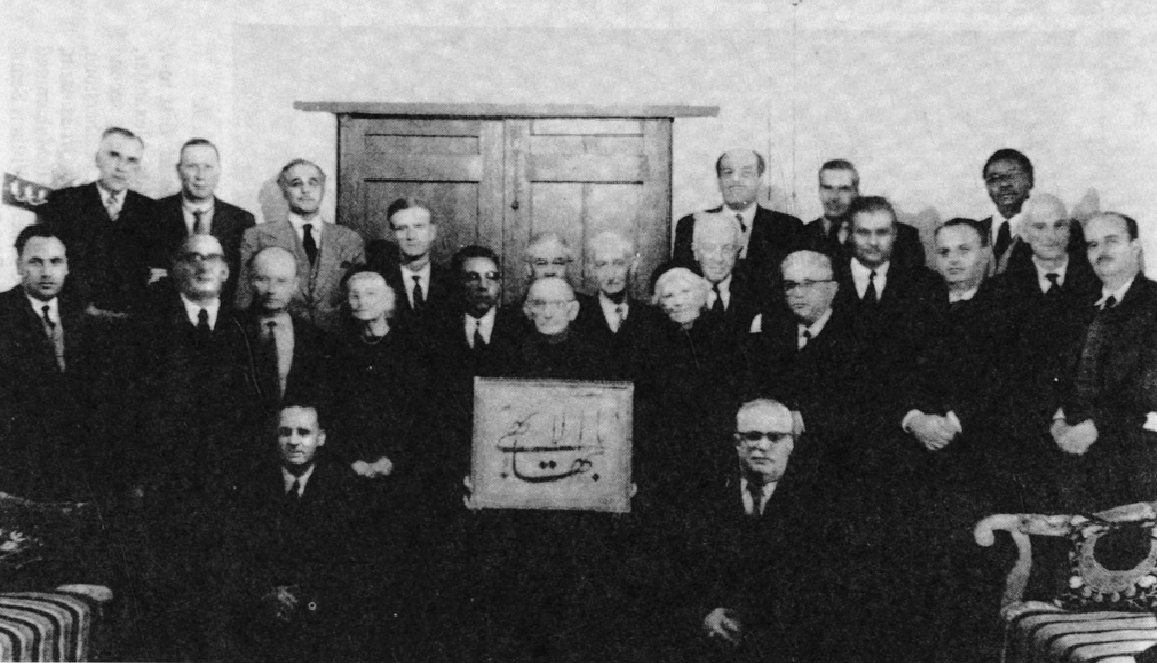

The 12 Hands of the Cause present in London on Friday 8 November 1957.

As the Guardian’s casket was very heavy, the Hands of the Cause carefully chose special bearers physically strong enough to carry the extremely heavy casket while maintaining the utmost dignity.

In the evening of Friday 8 November, the 12 Hands of the Cause present in London met together to prepare the prayers and readings for the Guardian’s funeral the next day. As the Hands of the Cause carefully chose the readings for the devotional programs at Shoghi Effendi’s funeral, they kept in mind that there would be one non-Bahá'í present, Gershon Avner, the representative of the Israeli government.

They worked until very late into the night.

These 12 Hands of the Cause present in London were from top to bottom and left to right:

- Rúḥíyyih Khánum

- Ḥasan Balyúzí

- John Ferraby

- Ugo Giachery

- Amelia Collins

- Adelbert Mühlschlegel

- Hermann Grossmann

- Paul Haney

- William Sears

- Abu’l-Qásim Faizi

- Shu’á’u’lláh ‘Alá’í

- Mason Remey

More Hands of the Cause would arrive the next day, including Leroy Ioas.

Bahá'ís standing in front of the Bahá'í National Center of the United Kingdom, at 27 Rutland Gate in London, on the day of the funeral of the Guardian, Saturday 9 November 1957. This photograph was taken by Arthur L. Dahl and is © Gregory C. Dahl from his historical photographic archive Bahá’í World Community: Historical Photos and Recordings. Source: Bahaimedia.

During the week prior to the Guardian’s funeral—from 4 to 9 November 1957—the National Bahá'í Center at 27, Rutland Gate in London was inundated by requests from agonizing, grieving Bahá'ís from around the world looking for information, asking for details, requesting directions to the cemetery, and more.

The telephone at the National Center rang uninterruptedly.

Hand of the Cause John Ferraby, Secretary of the British National Spiritual Assembly, with the constant help of his wife Dorothy Cansdale, also a member of the National Spiritual Assembly, were utterly deluged with work. They answered phone calls from Djakarta, Bombay, Kuwait, Israel, the United States and several European countries, responded to a ceaseless flow of cables and letters that poured in and out, wrote press releases and gave interviews.

It quickly became clear that the influx of Hands of the Cause, National Spiritual Assembly, Auxiliary Board Members, a large number of British Bahá'ís, as well as Bahá'ís from around the world were converging on London to attend the funeral of the Guardian.

Tragically, most of the heartbroken Bahá'ís pouring in from overseas would miss the funeral. As Rúḥíyyih Khánum described it:

As the Bahá'ís arrived in ever-increasing numbers, a great flood-tide of love and sorrow was rising about the silent figure of the Sign of God on earth, preparing to bear his sacred remains befittingly to the grave.

The inmost Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh, from where the precious items Leroy Ioas brings with him to London have come. Background border photo by McGill Library on Unsplash.

Hand of the Cause Leroy Ioas, Secretary-General of the International Bahá'í Council, had promptly and befittingly informed the Israeli authorities regarding the sudden and unexpected passing of Shoghi Effendi, the Head of the Bahá'í Faith.

After properly and thoroughly locking and sealing the Guardian’s rooms and office at the House of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, Leroy Ioas left Haifa and arrived in London at 8 AM on Saturday 9 November, the morning of the funeral.

Leroy Ioas was bringing with him from the Holy Land two items which Rúḥíyyih Khánum had specifically requested: a small rug from the innermost Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh at Bahjí, with which to carpet the floor of the vault, and a covering, which had also rested in the innermost Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh, to cover the casket.

Leroy Ioas also brought a bouquet of white jasmine—the Guardian’s favorite scent—and a box of flowers gathered from the Gardens at Bahjí, the Ridván Garden, Mazra'ih and the gardens on Mount Carmel.

Cars being boarded in front of the London Bahá'í Center, for Bahá'ís to attend funeral of the Guardian. This car is one of the 65 which formed the Guardian’s funeral cortege. This photograph was taken by Arthur L. Dahl and is © Gregory C. Dahl from his historical photographic archive: Bahá’í World Community: Historical Photos and Recordings. Source: Bahaimedia.

The Guardian’s funeral cortege of 65 cars carrying 360 Bahá'ís, gathered at 10 AM in front of the National Bahá'í Center at 27 Rutland Gate, opposite Hyde Park.

They, left the National Center 40 minutes later in a solemn file, and met the hearse on the way in Hampstead near Avenue Road and Finchley Road.

At the very front of the funeral cortege was a floral hearse, followed by the hearse carrying the casket of the beloved Guardian, which was followed by the car of Hands of the Cause Rúḥíyyih Khánum and Amelia Collins.

The other remaining Hands of the Cause, which included Músá Banání, Enoch Olinga, Dhikru’lláh Khadem, and Raḥmatu'lláh Muhájir, were behind this car, and behind them were, in order, the members of the National Spiritual Assembly of the British Isles, the members of the Auxiliary Board members and lastly, in the rest of the cars, the Bahá'ís from Britain and the rest of the world.

It was one of the largest funeral corteges London had seen in many years.

Hearse arriving at the chapel, followed by the car of Amatu’l-Bahá Ruḥíyyíh Khánum, accompanied by Amelia Collins. Source: The Bahá'í World Volume 13, page 210.

The funeral cortege arrived at the Great Northern Cemetery at New Southgate in less than an hour, and when they arrived, they found a large crowd of Bahá'ís already waiting at the door of the Chapel, each face bearing its own measure of grief, and many of them in tears.

The casket containing the remains of the beloved Guardian is about to be removed from the hearse, with its trunk open, and carried into the chapel for the funeral service. Source: The Bahá'í World Volume 13, page 210.

The casket of the Guardian was carried in by 8 strong pall-bearers and laid on the soft green covering of the raised platform. The Guardian’s casket was covered with a large blanket of deep-red roses with fragrant white gardenias, gardenias, fuchsias and lilies of the valley—the Guardian’s favorite flower.

In the center, a simple card carried a deeply tender inscription:

From Rúḥíyyih and all your loved ones and lovers all over the world whose hearts are broken.

A hushed and sorrowing throng filled the chapel to over-flowing. Source: The Bahá'í World Volume 13, page 212.

Inside the chapel at the cemetery was a platform.

On both sides of the platform were raised areas with several rows of chairs.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum sat on the right with Amelia Collins beside her, and behind them, in the second row were the Hands of the Cause and Gershon Avner, the representative of the Israeli Government.

Baba 'is enter the chapel for the funeral service. Source: The Bahá'í World Volume 13, page 211.

Bahá'ís filled all the available seats inside the chapel.

The remainder of the Bahá'ís who could not sit, stood filling the back of the chapel, and the rest stood outside.

Every person in chapel rose while Hand of the Cause Abu’l-Qásim Faizi chanted the Prayer for the Dead revealed by Bahá'u'lláh in Arabic with deep emotion.

Hand of the Cause Abu’l-Qásim Faizi had an enchanting voice and the Guardian and the Greatest Holy Leaf had loved his chanting when, as a teenager, he came to Haifa on pilgrimage in the summers during his studies at the American University in Beirut.

One of the believers reading from the Sacred Writings. The coffin of Shoghi Effendi was placed in front of the bank of flowers shown on the right.. Source: The Bahá'í World Volume 13, page 212.

The devotional program consisted of 10 selections comprising five Arabic Hidden Words—two in English and three in Arabic with one Hidden Word, number 32, being recited in English and also chanted in Arabic.

There were also two prayers, two excerpts from the Writings of Bahá'u'lláh, and the first two paragraphs from the Will and Testament of 'Abdu'l-Bahá.

All the prayers and selections in English, Arabic and Persian were read or chanted by Betty Reed, Borrah Kavelin, Adib Taherzadeh, William Sears, Elsie Austin, Ian Semple and Enoch Olinga, all Bahá'ís with beautiful voices, and from every continent.

You can find the full devotional program below this section of the chronology on The Utterance Project website.

Selections 1 and 2: The Hidden Words from the Arabic, numbers 32 and 11

O SON OF THE SUPREME! I have made death a messenger of joy to thee. Wherefore dost thou grieve? I made the light to shed on thee its splendor. Why dost thou veil thyself therefrom?

O SON OF BEING! Thou art My lamp and My light is in thee. Get thou from it thy radiance and seek none other than Me. For I have created thee rich and have bountifully shed My favor upon thee.

Selection 3: Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá'u'lláh CLXV

Death proffereth unto every confident believer the cup that is life indeed. It bestoweth joy, and is the bearer of gladness. It conferreth the gift of everlasting life. As to those that have tasted of the fruit of man’s earthly existence, which is the recognition of the one true God, exalted be His glory, their life hereafter is such as We are unable to describe. The knowledge thereof is with God, alone, the Lord of all worlds.

Selection 4: Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá'u'lláh, number CLXIII.

All praise be to God Who hath adorned the world with an ornament, and arrayed it with a vesture, of which it can be despoiled by no earthly power, however mighty its battalions, however vast its wealth, however profound its influence. Say: the essence of all power is God’s, the highest and the last End of all creation. The source of all majesty is God’s, the Object of the adoration of all that is in the heavens and all that is on the earth. Such forces as have their origin in this world of dust are, by their very nature, unworthy of consideration.

Say: The springs that sustain the life of these birds are not of this world. Their source is far above the reach and ken of human apprehension. Who is there that can put out the light which the snow-white Hand of God hath lit? Where is he to be found that hath the power to quench the fire which hath been kindled through the might of thy Lord, the All-Powerful, the All-Compelling, the Almighty?

…Say: The fierce gales and whirlwinds of the world and its peoples can never shake the foundation upon which the rocklike stability of My chosen ones is based.

Selections 5, 6, and 7: The Hidden Words from the Arabic (chanted in Arabic) numbers 12, 14, 32

O SON OF BEING! With the hands of power I made thee and with the fingers of strength I created thee; and within thee have I placed the essence of My light. Be thou content with it and seek naught else, for My work is perfect and My command is binding. Question it not, nor have a doubt thereof.

O SON OF MAN! Thou art My dominion and My dominion perisheth not; wherefore fearest thou thy perishing? Thou art My light and My light shall never be extinguished; why dost thou dread extinction? Thou art My glory and My glory fadeth not; thou art My robe and My robe shall never be outworn. Abide then in thy love for Me, that thou mayest find Me in the realm of glory.

O SON OF THE SUPREME! I have made death a messenger of joy to thee. Wherefore dost thou grieve? I made the light to shed on thee its splendor. Why dost thou veil thyself therefrom?

Selection 8: Prayers and Meditations, number CXLV

O God, my God! Be Thou not far from me, for tribulation upon tribulation hath gathered about me. O God, my God! Leave me not to myself, for the extreme of adversity hath come upon me. Out of the pure milk, drawn from the breasts of Thy loving-kindness, give me to drink, for my thirst hath utterly consumed me. Beneath the shadow of the wings of Thy mercy shelter me, for all mine adversaries with one consent have fallen upon me. Keep me near to the throne of Thy majesty, face to face with the revelation of the signs of Thy glory, for wretchedness hath grievously touched me. With the fruits of the Tree of Thine Eternity nourish me, for uttermost weakness hath overtaken me. From the cups of joy, proffered by the hands of Thy tender mercies, feed me, for manifold sorrows have laid mighty hold upon me. With the broidered robe of Thine omnipotent sovereignty attire me, for poverty hath altogether despoiled me. Lulled by the cooing of the Dove of Thine Eternity, suffer me to sleep, for woes at their blackest have befallen me. Before the throne of Thy oneness, amid the blaze of the beauty of Thy countenance, cause me to abide, for fear and trembling have violently crushed me. Beneath the ocean of Thy forgiveness, faced with the restlessness of the leviathan of glory, immerse me, for my sins have utterly doomed me.

Selection 9: Prayers and Meditations, number XCII

Glory to Thee, O my God! But for the tribulations which are sustained in Thy path, how could Thy true lovers be recognized; and were it not for the trials which are borne for love of Thee, how could the station of such as yearn for Thee be revealed? Thy might beareth me witness! The companions of all who adore Thee are the tears they shed, and the comforters of such as seek Thee are the groans they utter, and the food of them who haste to meet Thee is the fragments of their broken hearts.

How sweet to my taste is the bitterness of death suffered in Thy path, and how precious in my estimation are the shafts of Thine enemies when encountered for the sake of the exaltation of Thy word! Let me quaff in Thy Cause, O my God, whatsoever Thou didst desire, and send down upon me in Thy love all Thou didst ordain. By Thy glory! I wish only what Thou wishest, and cherish what Thou cherishest. In Thee have I, at all times, placed my whole trust and confidence.

Raise up, I implore Thee, O my God, as helpers to this Revelation such as shall be counted worthy of Thy name and of Thy sovereignty, that they may remember me among Thy creatures, and hoist the ensigns of Thy victory in Thy land.

Potent art Thou to do what pleaseth Thee. No God is there but Thee, the Help in Peril, the Self-Subsisting.

Selection 10: The Will and Testament of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, first two paragraphs

All-praise to Him Who, by the Shield of His Covenant, hath guarded the Temple of His Cause from the darts of doubtfulness, Who by the Hosts of His Testament hath preserved the Sanctuary of His most Beneficent Law and protected His Straight and Luminous Path, staying thereby the onslaught of the company of Covenant-breakers, that have threatened to subvert His Divine Edifice; Who hath watched over His Mighty Stronghold and All-Glorious Faith, through the aid of men whom the slander of the slanderer affect not, whom no earthly calling, glory and power can turn aside from the Covenant of God and His Testament, established firmly by His clear and manifest words, writ and revealed by His All-Glorious Pen and recorded in the Preserved Tablet.

Salutation and praise, blessing and glory rest upon that primal branch of the Divine and Sacred Lote-Tree, grown out, blest, tender, verdant and flourishing from the Twin Holy Trees; the most wondrous, unique and priceless pearl that doth gleam from out the Twin surging seas; upon the offshoots of the Tree of Holiness, the twigs of the Celestial Tree, they that in the Day of the Great Dividing have stood fast and firm in the Covenant; upon the Hands (pillars) of the Cause of God that have diffused widely the Divine Fragrances, declared His Proofs, proclaimed His Faith, published abroad His Law, detached themselves from all things but Him, stood for righteousness in this world, and kindled the Fire of the Love of God in the very hearts and souls of His servants; upon them that have believed, rested assured, stood steadfast in His Covenant and followed the Light that after my passing shineth from the Dayspring of Divine Guidance—for behold! he is the blest and sacred bough that hath branched out from the Twin Holy Trees. Well is it with him that seeketh the shelter of his shade that shadoweth all mankind.

The coffin bearing the remains of the Guardian being carried out of the chapel to the gravesite, where it will be lowered into the vault. Source: The Bahá'í World Volume 13, page 214.

In a solemn file the Bahá'ís followed the casket, which was gently placed at the head of the grave, and oriented so that the Guardian was facing the Qiblih—the Holiest place on earth for Bahá'ís, the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh at Bahjí in the Holy Land.

Stunned by their great loss, men, women and children follow the hearse to the grave. Source: The Bahá'í World Volume 13, page 219.

In a solemn file the friends followed the casket, where the casket containing his blessed remains was gently deposited at the head of the grave, and oriented so that the Guardian was facing the Qiblih—the Holiest place on earth for Bahá'ís, the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh.

The Grave of the Guardian, covered in beautiful flowers, shortly after funeral. This photograph was taken by Arthur L. Dahl and is © Gregory C. Dahl from his historical photographic archive: Bahá’í World Community: Historical Photos and Recordings. Source: Bahaimedia.

The graveside was covered with mats of green straw imitating grass and giving the illusion of spring.

The grave was lined with cedar boughs, studded with flowers.

When the flowers were removed from the casket, they revealed the engraved bronze plaque on which was written:

Shoghi Effendi Rabbání

First Guardian

of the Bahá'í Faith

As everyone stood, silently, Rúḥíyyih Khánum felt the agony of the hearts around her penetrate into her own great grief, and, recalling the event a month later, she wrote:

He was their Guardian. He was going forever from their eyes, suddenly snatched from them by the immutable decree of God, Whose Will no man dare question. They had not seen him, had not been able to draw near him.

Grief-stricken farewells take place as the Baha'is file past the casket of their beloved Guardian at the foot of his open grave. A man can be seen resting his head at the foot of the Guardian’s casket. Source: The Bahá'í World Volume 13, page 221.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum had made a decision that an announcement be made before the Guardian’s casket was lowered into the vault, that the Bahá'ís who wished to do so could pay their personal respects to their beloved Guardian by passing by the casket.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum was a comfort to the grieving Bahá'ís, described by Marion Hofman as “a queen, a sister, a mother to those too much overcome, a tower of strength, the wife of our Guardian.”

For the most part, in a rare demonstration of love, grief, and reverence, the Bahá'ís knelt and kissed the edge or the handle of the casket.

Children bowed their little heads beside their mothers, old men wept, and even the British—famous for their stoicism—melted as they said goodbye to their beloved Guardian.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum describes how it seemed to her even nature wept over the Guardian:

The morning had been sunny and fair; now a gentle shower started and sprinkled a few drops on the casket, as if nature herself were suddenly moved to tears.

Under a sea of umbrellas, Bahá'ís said farewell to their Guardian.

Some placed little gifts on the casket, small flasks of attar of rose or a red rose.

Others with trailing fingers carried away some of the earth near the casket as a memento.

They cried, placed kisses, swore solemn inner vows as they passed by the casket of the one who had called himself their “true brother” for 36 years.

By this time, the Guardian’s service that had lasted almost 4 hours, and Gershon Avner, the representative of the Israeli Government, was obviously deeply moved, as he himself, filed by the Guardian’s casket and paid his respects with a bowed head.

It took two hours until the last believers had paid their respects.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum then herself approached the casket of her Guardian and beloved husband.

She knelt by it and prayed for a moment, then had the green cloth spread over it, followed by the blue and gold brocade Leroy Ioas had brought from the innermost Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh.

Then, she laid the jasmine flowers Leroy had brought from the Holy Land, the Guardian’s favorite scent, over all the length of the brocade.

In this photograph you can see theh casket of the Guardian covered in the. cloth with the flowers from the Holy Shrines placed in the vault lined with boughs studded with flowers. Source: The Bahá'í World Volume 13, page 223.

The mortal remains of him whom 'Abdu'l-Bahá designated “the most wondrous, unique and priceless pearl that doth gleam from out the Twin Surging Seas” were then slowly lowered into the vault that had been constructed, amid walls covered with evergreen boughs and studded with flowers, to rest upon the Persian carpet from the Holiest of Holies, the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh at Bahjí.

Baha'is gathered at the Guardian's grave during the funeral. This photograph was taken by Arthur L. Dahl and is © Gregory C. Dahl from his historical photographic archive: Bahá’í World Community: Historical Photos and Recordings. Source: Bahaimedia.

After the Guardian’s casket was lowered into his grave, a woman chanted an unplanned prayer in Persian, after which the formal programmed resumed.

The graveside devotional program was composed of two prayer.

The prayer in Persian was one of Shoghi Effendi’s own prayers and it was chanted by ‘Alí Nakhjávání.

The English prayer, was read by Hand of the Cause and member of the family of the Báb, Ḥasan Balyúzí.

Prayer by Shoghi Effendi chanted in Persian

The Guardian did not like his prayers in Persian translated into English, so it is a true honor to be able to share the English for this prayer, titled Dar ín layliy-i-laylá (In this darkest night), translated into English by Hand of the Cause Ḥasan Balyúzí.

He is God

O Mighty Lord! Thou seest what hath befallen Thy helpless lovers in this darkest of long nights; Thou knowest how, in all these years of separation from Thy Beauty, the confidants of Thy mysteries have ever been acquainted with burning grief.

O Powerful Master! Suffer not Thy wayfarers to be abased and brought low; succor this handful of feeble creatures with the potency of Thy might. Exalt Thy loved ones before the assemblage of man, and grant them strength. Allow those broken-winged beings to raise their heads and glory in the fulfilment of their hopes, that we in these brief days of life may gaze with our physical eyes on the elevation and exaltation of Thy Faith, and soar up to Thee with gladdened souls and blissful hearts.

Thou knowest that, since Thy ascension, we seek no name or fame, that in this swiftly passing world we wish henceforth no joy, no delight and no good fortune.

Then keep Thy word, and exhilarate once more the lives of these, Thy sick at heart. Bring light to our expectant eyes, balm to our stricken breasts. Lead Thou the caravans of the city of Thy love swiftly to their intended goal. Draw those who sorrow after Thee into the high court of reunion with Thee. For in this world below we ask for nothing but the triumph of Thy Cause. And within the precincts of Thy boundless mercy we hope for nothing but Thy presence.

Thou art the Witness, the Haven, the Refuge; Thou art He who rendereth victorious this band of the innocent.

Prayer in English

Glory be to Thee, O God, for Thy manifestation of love to mankind! O Thou Who art our Life and Light, guide Thy servants in Thy way, and make us rich in Thee and free from all save thee.

O God, teach us Thy Oneness and give us a realization of Thy Unity, that we may see no one save Thee. Thou art the merciful and the Giver of bounty!

O God, create in the hearts of Thy beloved the fire of Thy love, that it may consume the thought of everything save Thee.

Reveal to us, O God, Thine exalted eternity—that Thou hast ever been and will ever be, and that there is no God save Thee. Verily, in Thee will we find comfort and strength.

“a rich carpet of exquisite flowers, symbols of the love, the suffering, of so many hearts” Background photo by Cody Chan on Unsplash.

After the final prayer and the majority of the Bahá'ís had left the cemetery, the Hands of the Cause, the members of the National Spiritual Assembly of the British Isles, and the members of the Auxiliary Boards, gathered together and said many prayers in many languages, representing many countries in the world.

Hand of the Cause Ṭaráẓu'lláh Samandarí, the only remaining Hand of the Cause to have had the honor of entering into the presence of Bahá'u'lláh, placed orange and olive branches from the Garden of Riḍván in Baghdad, where Bahá'u'lláh had declared His mission 94 years before.

Hand of the Cause Leroy Ioas had brought enough flowers from the Bahá'í gardens in the Holy Land for every person present to have something to offer the Guardian and place, for the last time, on his casket.

oly Land for every person present to have something to offer the Guardian and place, for the last time, on his casket.

As Rúḥíyyih Khánum described the touching scene:

Over the tomb, at his feet, like a shield of crimson and white, lay the fragrant sheath of blooms which had covered his casket, and heaped about was a rich carpet of exquisite flowers, symbols of the love, the suffering, of so many hearts, and no doubt the silent bearers of vows to make the Spirit of the Guardian happy now, to fulfil his plans, carry on his work, be worthy at last of the love and inspired self-sacrificing leadership he gave them for thirty-six years of his life.

After this, the Hands of the Cause, National Spiritual Assembly members and Auxiliary Board Members, ensured together that the vault of the Guardian’s resting place was properly and duly sealed.

Hand of the Cause Bill Sears and the American Bahá'ís remembering Shoghi Effendi on 2 May 1958, as he places a wreath on the resting place of the Guardian at the same time as the Intercontinental Conference opened in Chicago. Source: Bahaimedia.

On the day after the funeral, Sunday 10 November 1957. Rúḥíyyih Khánum sent a message to the grieving Bahá'í world informing them about the funeral and requesting believers to hold memorial gatherings.

Beloved Guardian laid rest London according laws Aqdas in beautiful spot after impressive ceremony held presence multitude believers representing over twenty-five countries east and west. Doctors assure sudden passing involved no suffering blessed countenance bore expression infinite beauty peace majesty. Eighteen Hands assembled funeral urge National Bodies request all believers hold memorial meetings eighteenth November commemorating dayspring divine guidance who was left us after thirty-six years utter self-sacrifice ceaseless labours constant vigilance. Rúḥíyyih.