Written and illustrated by Violetta Zein

This part covers the life of Shoghi Effendi from the age of 59 in 1956 to the age of 60 in 1957.

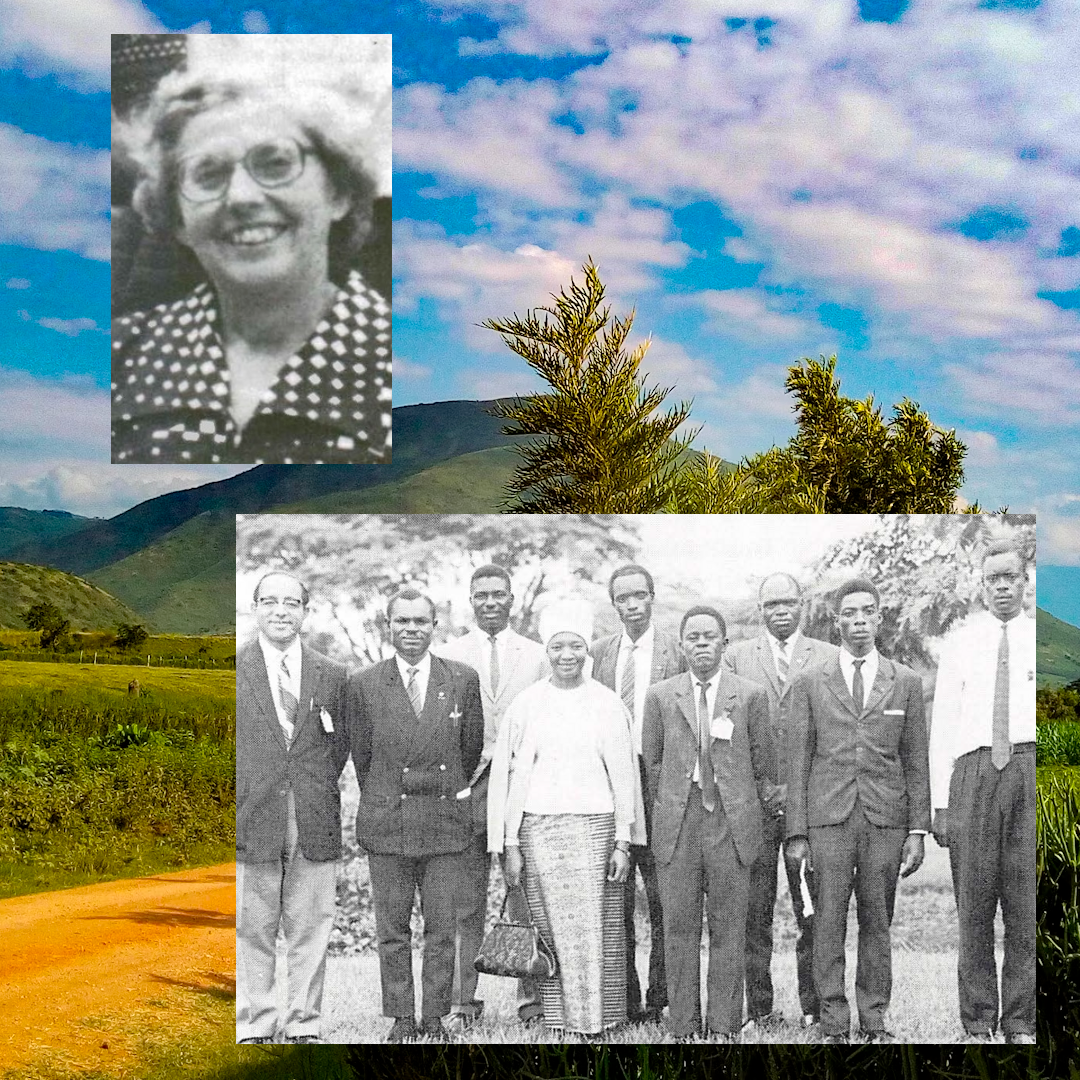

Gayle Woolson, member of the National Spiritual Assembly of South America. Source: Bahaimedia.

Gayle Woolson was born Gayle Abas in Crookston, Minnesota, to an Arabic-speaking Muslim family of Syrian descent. Her future husband, Clement Woolson, introduced her to the Faith. She became a Knight of Bahá'u'lláh for the Galapagos Islands and served as a National Spiritual Assembly and Auxiliary Board member.

When Gayle Woolson was on pilgrimage in Haifa on 16 February 1956, the Guardian spoke at length about effective teaching. He said the new Bahá'í had to develop spiritually, and arise to teach others, as it was happening in Africa.

The Guardian also warned the pilgrims that conversion should not be the goal of a Bahá'í teacher, but rather that they should teach with determination and patience, and never become discouraged if the progress was slow.

Speaking about attracting indigenous peoples to the Faith, the Guardian said:

Attract them through friendliness and kindness. Give them preference in everything; not only equality but preference, preferential treatment. Teaching the Indians [indigenous peoples] is very important…The Bahá'ís must treat them just the opposite of the way the others treat them. Amongst the Bahá'ís, the minorities in any country must be given preferential treatment. If there is a tie between two believers for anything, and one is of a minority group, there must not be a second vote. Preference must be given to the believer of the minority group.

Two years prior, Shoghi Effendi had told a pilgrim that there were three stages to the process of teaching the Faith to receptive souls:

- The first stage was attracting the people;

- The second stage was conversion to the Faith;

- The third stage was consecration: the new Bahá'ís arising to serve.

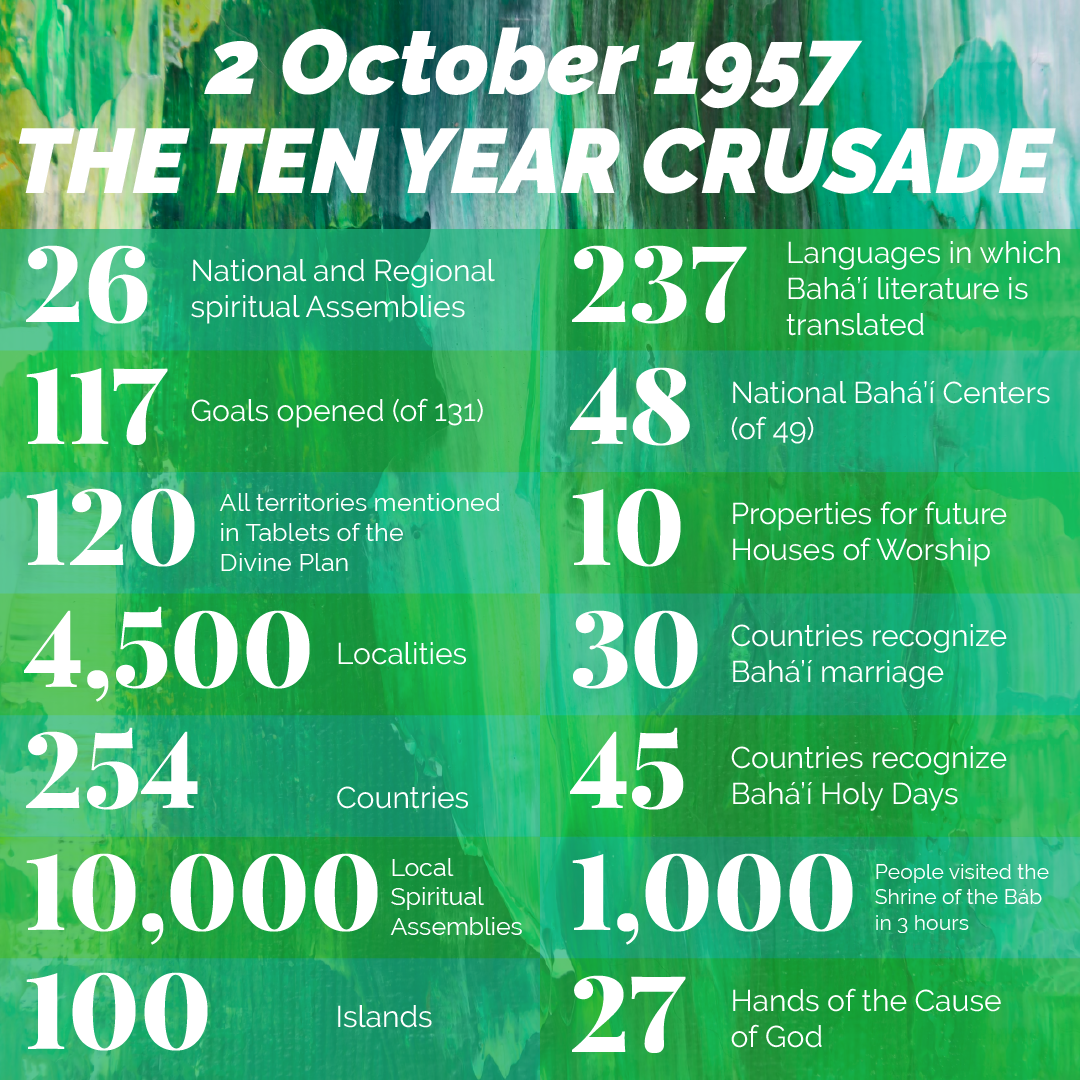

In his Riḍván message of 1956 the Guardian, as the Bahá'í world was entering into the third phase of the first five years in its world Crusade, highlighted the achievements attained by its band of heroes over the course of the two years since its inaugural phase:

- There were now 3,700 localities opened to the Faith over the surface of the entire planet

- 237 Sovereign States and Chief Dependencies where the Bahá'í Faith was present

- 900 Local Spiritual Assemblies

- All the countries listed as pioneering goals were now opened to the Faith except for those in the Soviet Union

- Over 70 islands in the Pacific, the Atlantic, and the Indian Oceans, were opened except for 6, bringing the total to 98 islands worldwide

- 40 territories were opened to the Faith in the Pacific, with 170 Bahá'í localities

- Bahá'í literature was now translated into 190 languages including 34 not included in the original plan

- In over 60 territories, the number of those who have become Bahá'ís has surpassed the number originally anticipated

- In a considerable proportion of these territories, Bahá'í membership has far exceeded the number required for the formation of local Assemblies, such as Gambia, for example, with 300 Bahá'ís

- There were 3,000 Bahá'ís in Africa

- 58 territories and islands were opened in Africa, with 400 Bahá'í localities

- 140 African tribes were now represented in the Bahá'í community

- 120 Local Spiritual Assemblies in Africa were functioning

- Bahá'í literature was now published in 50 African languages

- There were 43 National Ḥaẓíratu’l-Quds—National Bahá'í Centers

- 168 incorporated Local and National Spiritual Assemblies

- Land for 10 Temple Sites was acquired

- The value of National Bahá'í endowments in 51 countries exceeded $100,000—$1.1 million in today’s currence—and now included the Maxwell Home in Montreal

- The design for the House of Worship in Iran was approved

- Plans for three additional Houses of Worship in Europe, Africa, and Australia had begun

- In the Holy Land, the Covenant-breakers suffered defeat after defeat and Mírzá Majdi’d-Dín, the last survivor of the original Covenant-breakers from the time of 'Abdu'l-Bahá finally died

- In more positive news, 52 pillars of the International Bahá'í Archives had been raised and 450 tons of stone safely arrived in Haifa

- The contract was signed with the same factory in Utrecht who provided the golden tiles of the Shrine of the Báb for the green tiles of the Archives building

- The Monument Gardens were extended

- Several properties were acquired in Bahjí and on Mount Carmel

- The Temple Land on Mount Carmel was in the process of being purchased

- In the United States the Bahá'ís were invited by the San Francisco Council of Churches to attend a prayer meeting for the United Nations

- At this inter-religious gathering, the voice of the Bahá'í representative was the first to be raised, reciting a prayer revealed by Bahá'u'lláh

- A prayer revealed by `Abdu'l-Bahá for America was presented by the elected national representatives of the United States Bahá'í Community to President Eisenhower, who acknowledged its receipt in warm terms and above his own signature.

- A Bahá'í Publishing Trust was established in India

- 30 new centers and 15 assemblies were formed in India, Pakistan and Burma

- In Edirne, Bahá'ís were able to purchase sites blessed by the footsteps of Bahá'u'lláh

- The very first Bahá'í Summer School in Central Africa was held in Kobuka, Uganda, with 100 attendees

- The first All-France Teaching Conference was convened

- The Bahá'ís of Tripoli, Libya and the Capital of Tanganyika both identified plots to serve as future Bahá'í cemeteries

- In Iraq, the Bahá'ís purchased land for a Bahá'í Summer School in Iraq

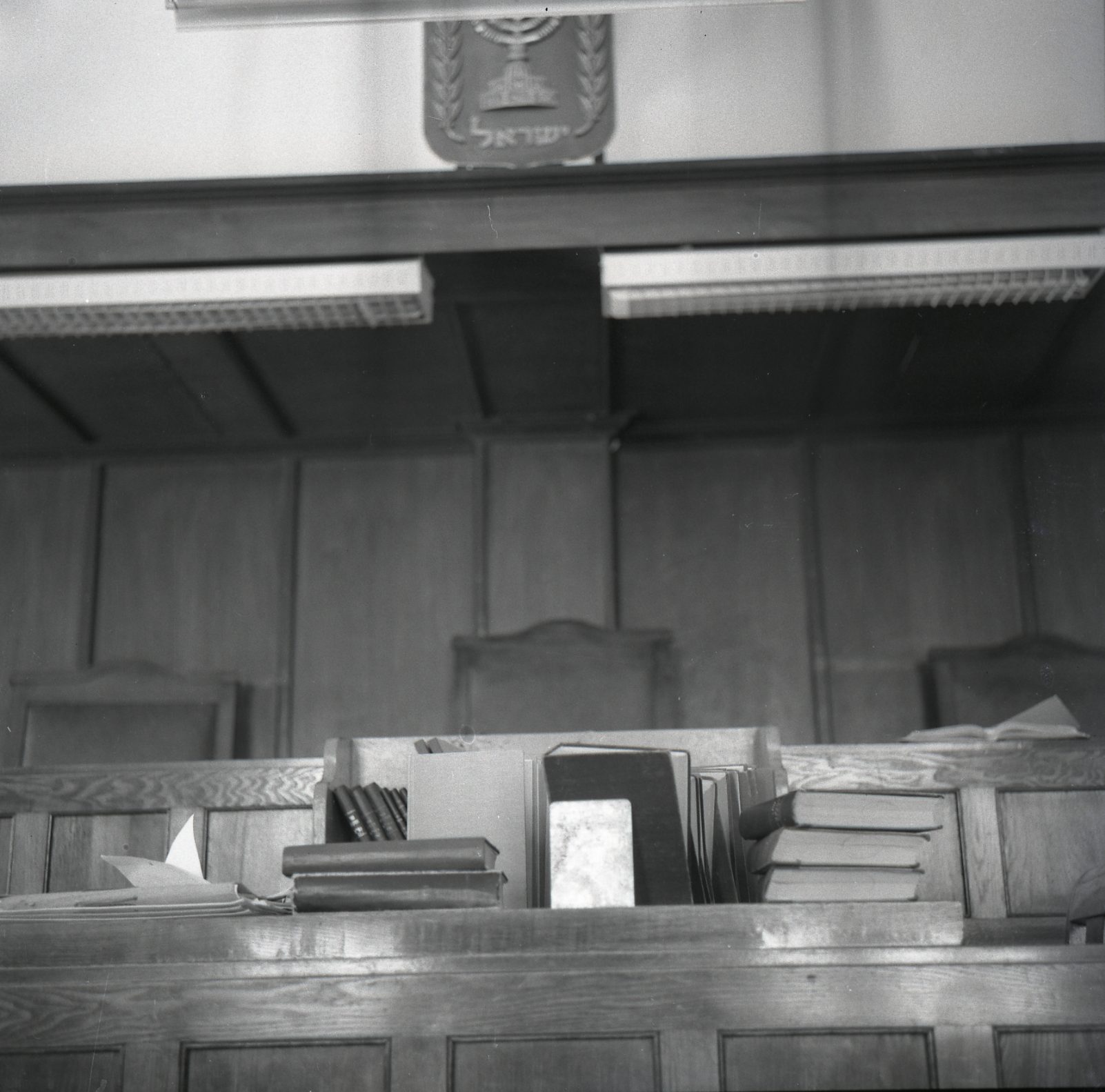

- The women of Egypt were granted the right to be elected to the Egyptian National Spiritual Assembly and participate as delegates at National Convention

- In the Mentawai Islands, a plot of land was purchased supplementing the National Bahá'í Endowment of Indonesia

- The northernmost outpost of the Faith in Alaska was pushed beyond the Arctic Circle

- The Seychelles and the Sudan both initiated plans for the propagation of the Faith

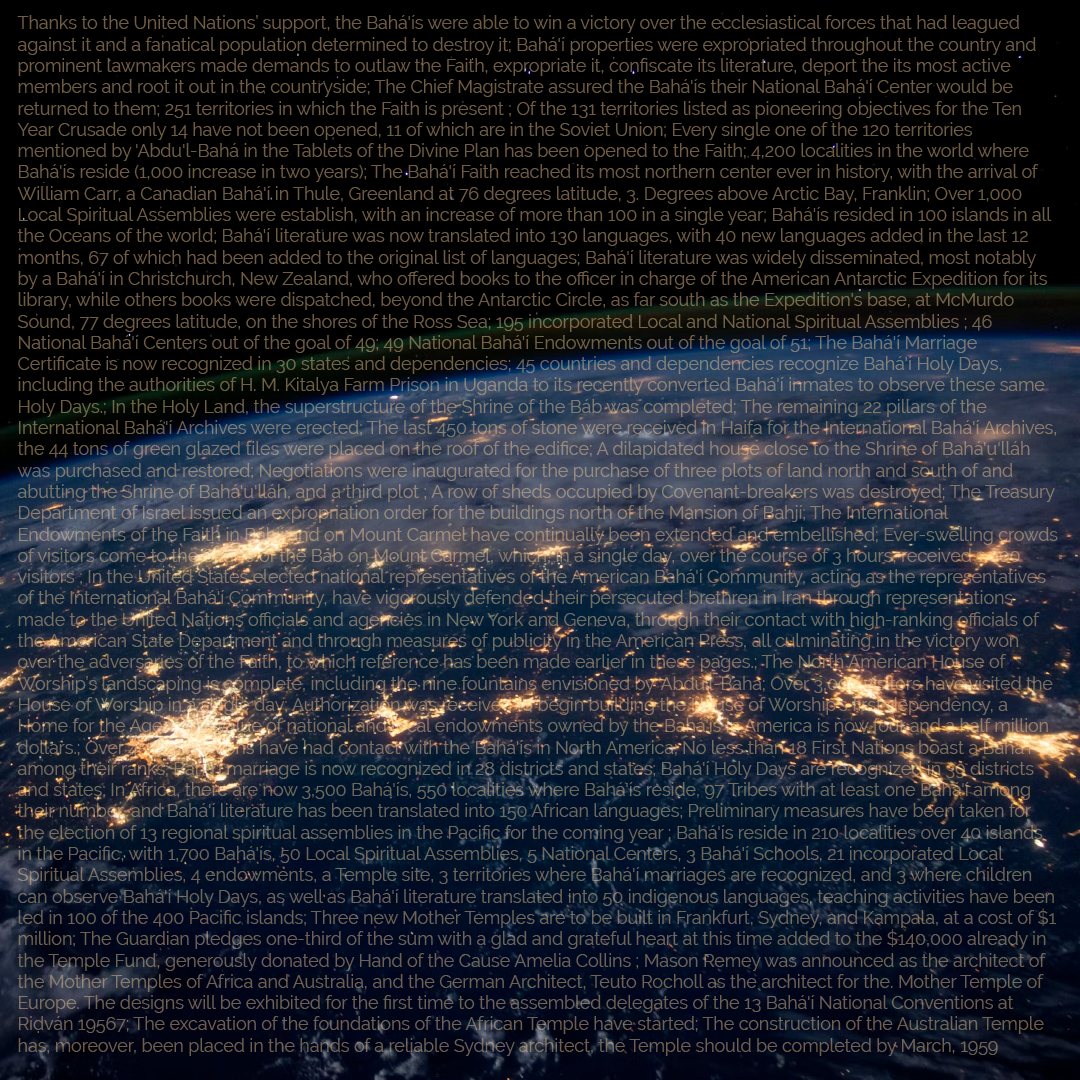

- The worldwide Bahá'í communities appealed with over 1,000 messages to the United Nations after the massacres of the Bahá'ís in Iran in 1955, subjected to the severest persecutions in decades.

- The Bahá'ís also contacted the Sháh of Iran, Government, the Majlis and the Senate

- Publicity was given on radio, in the world’s leading newspapers, protests were voiced by scholars, statesmen, government envoys and people of eminence such as Pandit Nehru, Eleanor Roosevelt, Professor Gilbert Murray and Professor A. Toynbee,

- A written memorandum listing the atrocities was submitted to the Secretary General of the United Nations, who appointed a commission of United Nations officers, headed by the High Commissioner for Refugees, instructing its members to contact the Persian Foreign Minister and urge him to obtain from his government in Tihrán a formal assurance that the rights of the Bahá'í minority in that land would be protected.

15 columns—half the Guardian’s achievement at this stage of construction—highlighted over the watercolor of the architectural drawing of the Archives. © United States National Bahá'í Archives, used with permission.

In his same Riḍván message of 21 April 1956, the Guardian linked the emergence of the International Bahá'í Archives, the first structure on the Arc, with the continued decline of the fortunes of the Covenant-breakers. He specifically referred to the disappearance "in miserable circumstances" of Mírzá Majdi’d-Dín, a notorious and particularly evil Covenant-breaker and the last survivor of the Covenant-breakers from the ministry of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, described by Shoghi Effendi as a "malignant" enemy of the Cause, even as the Archives was simultaneously rising from the ground in all its beauty.

The Guardian announced that 30 of the 52 pillars had been raised into position and that he had placed an order for 7,000 beautiful green tiles from the Utrecht factory in the Netherlands that had produced the golden tiles of the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb:

…on the other, through the laying of the foundation, and the erection of some of the pillars, of the facade and of the northern side of the International Bahá'í Archives—the first of the major edifices destined to constitute the seat of the World Bahá'í Administrative Center to be established on Mt. Carmel. No less than thirty of the fifty-two pillars, each over seven meters high, of this imposing and strikingly beautiful edifice have already been raised, whilst half of the nine hundred tons of stone ordered in Italy for its construction have already been safely delivered at the Port of Haifa. A contract, moreover, for over fifteen thousand dollars has been placed with a tile factory in Utrecht for the manufacture of over seven thousand green tiles designed to cover the five hundred square meters of the roof of the building.

“Putting on the armor of His love, firmly buckling on the shield of His mighty Covenant, mounted on the steed of steadfastness, holding aloft the lance of the Word of the Lord of Hosts” Photograph of The Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibit showing knights mounted on armored horses, holding aloft a lance, and protected by shields. Source: The Met.

The Guardian’s Riḍván 1956 message ends with the announcement of “a major turning point in the history of [the] marvelous unfoldment [of the Ten Year Crusade].” Paying tribute to the three years of magnificent exploits achieved by the Bahá'í community, with “a spirit of abnegation and self-sacrifice, so rare that only the spirit of the Dawn-breakers of a former age can be said to have surpassed it,” remembering the fallen heroes and the martyrs of the first two phases of these first five years, the Guardian could already discern the approaching age of entry by troops during the Ten Year Crusade:

Premonitory signs can already be discerned in far-off regions heralding the approach of the day when troops will flock to its standard, fulfilling the predictions uttered long ago by the Supreme Captain of its forces.

Referring to the Bahá'ís as “warriors enlisting under its banner” the Guardian raised their awareness of the work yet to be done, “fields of exploration and consolidation of such vastness as might well dazzle the eyes and strike awe into the heart of any soul less robust than those who have arisen to identify themselves with its Cause. The heights its champions must scale are indeed formidable. The pitfalls that bestrew their path are still numerous. The road leading to ultimate and total victory is tortuous, stony and narrow.”

But the Bahá'ís should never discourage, as Bahá'u'lláh assured them:

Whosoever ariseth to aid our Cause God will render him victorious over ten times ten thousand souls, and, should he wax in his love for Me, him will We cause to triumph over all that is in heaven and all that is on earth.

The last paragraph of the Guardian’s Riḍván 1956 is pure poetry, spurring on his spiritual army in the field to attain ultimate victory and never lose confidence:

Putting on the armor of His love, firmly buckling on the shield of His mighty Covenant, mounted on the steed of steadfastness, holding aloft the lance of the Word of the Lord of Hosts, and with unquestioning reliance on His promises as the best provision for their journey, let them set their faces towards those fields that still remain unexplored and direct their steps to those goals that are as yet unattained, assured that He Who has led them to achieve such triumphs, and to store up such prizes in His Kingdom, will continue to assist them in enriching their spiritual birthright to a degree that no finite mind can imagine or human heart perceive.

Leroy Ioas’ nephew Charles Ioas, Knight of Bahá'u'lláh to the Balearic Islands. Source: Bahaimedia. Background: A photo of Menorca, one of the Balearic Islands by Reiseuhu on Unsplash.

The Guardian's heart was with the pioneers, with those serving out on the front lines. He gloried more in their achievements than in anything else. Even at the Bahá'í World Centre, there were ties with the Crusade: Three of Leroy Ioas’ family members rose to the rank of Knight of Bahá'u'lláh: his nieces Margery Ullrich Kellberg in the Dutch West Indies, Florence Ullrich Kelley in Monaco, and his nephew Charles Ioas in the Balearic Islands.

The Guardian was inextricably tied to the Ten Year Crusade, he was a part of it, more so than the Knights of Bahá'u'lláh, it was the accomplishment in the most glorious form of the yearning of his Beloved Grandfather 'Abdu'l-Bahá in his majestic Tablets of the Divine Plan. What affected the Ten Year Crusade, affected the Guardian personally, Whenever he learned of difficulties that befell a pioneer he was depressed and saddened. When news of the Knights of Bahá'u'lláh’s and pioneers’ successes came to the Guardian, he was joyful. If they were forced to leave their pioneering posts, he was grieved.

The staff at the Bahá'í World Centre formed a unity with their Guardian, and they felt his emotions. When the Guardian was affected, everyone was affected. If he was sad, everyone was sad, if he was happy, everyone was joyful.

In a Riḍván message written by the Hands of the Cause during the Ministry of the Custodians after the Guardian’s passing, they wrote:

It is not possible for us to describe the wistful sadness and the look of concern and care that would pass over his blessed face when he received news that a goal had had to be abandoned and was lacking a pioneer.

“I’ll cross the other one off later.” Background image by Clay Banks on Unsplash.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum remembered a particularly poignant, heartbreaking moment that shows how sensitive the Guardian was when it came to losses during the World Crusade. On the same day, Shoghi Effendi received news that three pioneers had to abandon their post. Rúḥíyyih Khánum watched as the Guardian reluctantly crossed off two of their names in one of his little black notebooks, which he carried with him at all times. Later, Rúḥíyyih Khánum said to Shoghi Effendi:

Shoghi Effendi, you only crossed off two names.

Shoghi Effendi replied:

Yes, I’ll cross the other one off later.

The Guardian could not bring himself to cross off all three names at once.

“If we had let him go home he would not have won those victories.” Background image of Fiji, a Pacific island by Janis Rozenfelds on Unsplash.

One pioneer who went to an island in the Pacific and became extremely discouraged. He faced failure and opposition: he could not find a job, no one wanted to listen to what he had to say, the local clergy opposed him, and he was persecuted by the government. He asked the Guardian for permission to leave his post and the Guardian asked Leroy Ioas to write back, encouraging him to persevere, promising him that “every seed would ripen.”

Some time later, the man wrote again asking to leave, and the Guardian responded again that he should persevere.

The man wrote a third time, describing his dire financial situation and the Guardian said it should be arranged with his National Spiritual Assembly for him to be able to remain at his post.

Several months later, the Guardian arrived at dinner beaming with joy and said:

We have some wonderful cables today.

He shared a cable from this same pioneer: not only had he succeeded in enrolling 50 people into the Faith, but he had formed two Local Spiritual Assemblies. The Guardian said:

If we had let him go home he would not have won those victories.

Leroy Ioas remarked:

Well, Shoghi Effendi, I said, of course this pioneer, he did the work, but it’s the Guardian that actually won this victory. You’re the one that won it, because if it hadn’t been for you, he’d have left.

The Guardian said:

Leroy, he said, that is correct, I won those victories; I won them…I have to stay in the Holy Land. This is my seat of operation. The friends must do the work. And I tell you that if the friends would do what I had told them to do, and if they would follow my instructions, they would be amazed at the victories which I will win through them.

Leroy was amazed at the Guardian's response—he was speaking not just to the Bahá'ís seated at the dinner table, but to all Bahá'ís, worldwide. The Guardian acknowledged this and said:

Only years later did Leroy realize the full import of this answer, when the spirit of the Guardian was released from its physical confines and could work far more powerfully than when he was in this world.

When the Bahá'ís were winning great victories in the second half of the Ten Year Crusade, after the passing of the Guardian, Leroy Ioas once said:

Let me tell you, these extraordinary victories that are being won (in the second half of the Crusade) - Shoghi Effendi is winning them. His spirit is influencing anyone who becomes a proper vehicle for him to work through.

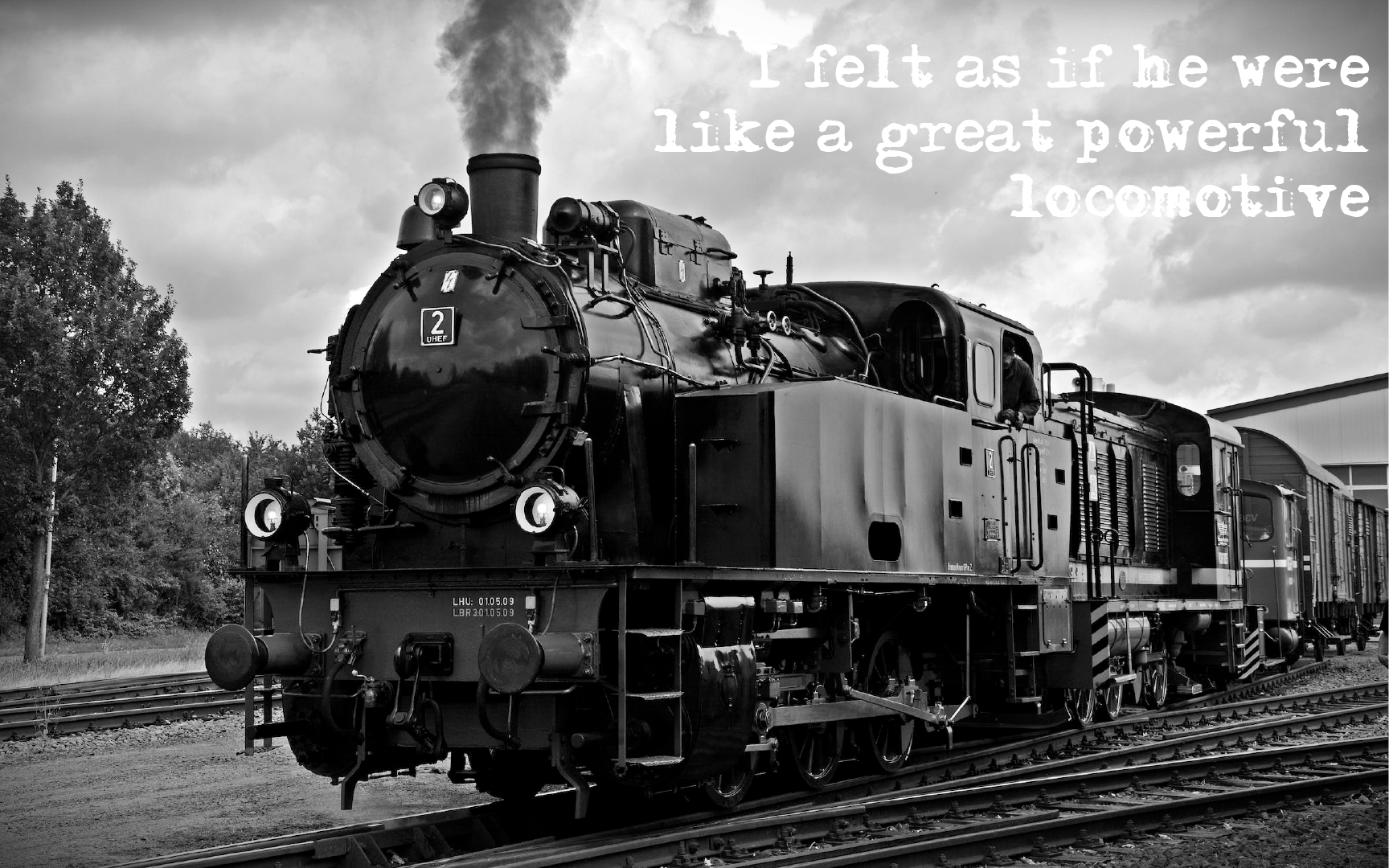

“I felt as if he were like a great powerful locomotive.” Steam locomotive background image by Pixabay on Pexels.

In 1956 a pilgrim, whose name we do not know, wrote her impressions of the Guardian which Rúḥíyyih Khánum found not only shrewd but accurate. This woman was a peerless judge of character, and found that Shoghi Effendi, who was at the time nearly 60 years old, looked like was just 48. She began by giving a beautiful and very detailed physical description of him:

His face is beautiful, as it is so pure in expression and so impersonal, yet at the same time tender and majestic...His nose is a combination of what it was in the pictures of him as a little boy - he still looks much like that! - and the sort of ridged nose of the Master…He had a small, greying moustache, tightly clipped. His mouth is firm and pure, his teeth white and beautiful. His smile is a precious bounty...

He is completely simple and direct. He himself does not demand all this deference, but just to be in his presence makes one feel absolutely “weak and lowly”. The Guardian is ever courteous and does not lose patience with questions of the immature. However, he is not reticent about letting people know which questions are important, and which are not, and which will be answered later by the International House of Justice…

This pilgrim saw the weight that Shoghi Effendi carried simply but majestically, as a king, his range of vision, extending infinitely further than any mere human could foresee, and his resistless march towards victory, sweeping along in his energy the entire community of believers:

I felt as if he were like a great powerful locomotive, pulling behind him a long, long string of cars, laden—not with dead-weight exactly—but sometimes pretty dead! This weight is the believers who have to be pushed, or pulled, or cajoled, or praised at every moment to get them into action. The beloved Guardian sees far in advance the needs, the lack of time, the obstacles and problems. He is actually hauling us all along behind his guiding and powerful light. Like a locomotive too—he can go straight ahead, fast or slow down, but he CANNOT deviate his course, he MUST follow the track which is his divine Guidance. He gives one the sense of being a perfect instrument—very impersonal, but hypersensitive to every thought, or atmosphere. He cannot be swayed in his thought. He is not influenced in the least by friendship, preference, money, hurting or not hurting feelings. He is absolutely above all that...

Perhaps the most heartbreaking comment this insightful pilgrim makes is how the Bahá'ís have not protected Shoghi Effendi as 'Abdu'l-Bahá had asked them in His Will and Testament, the suffering he has endured both at the hands of Covenant-breakers, but also at the hands of disobedient or careless Bahá'ís:

Alas, Shoghi Effendi's “radiant nature” has all too often been clouded over and saddened by the unwisdom of the friends, or their flagrant disobedience, or disregard of his instructions. Frantically one wonders who has not failed him in one way or another!

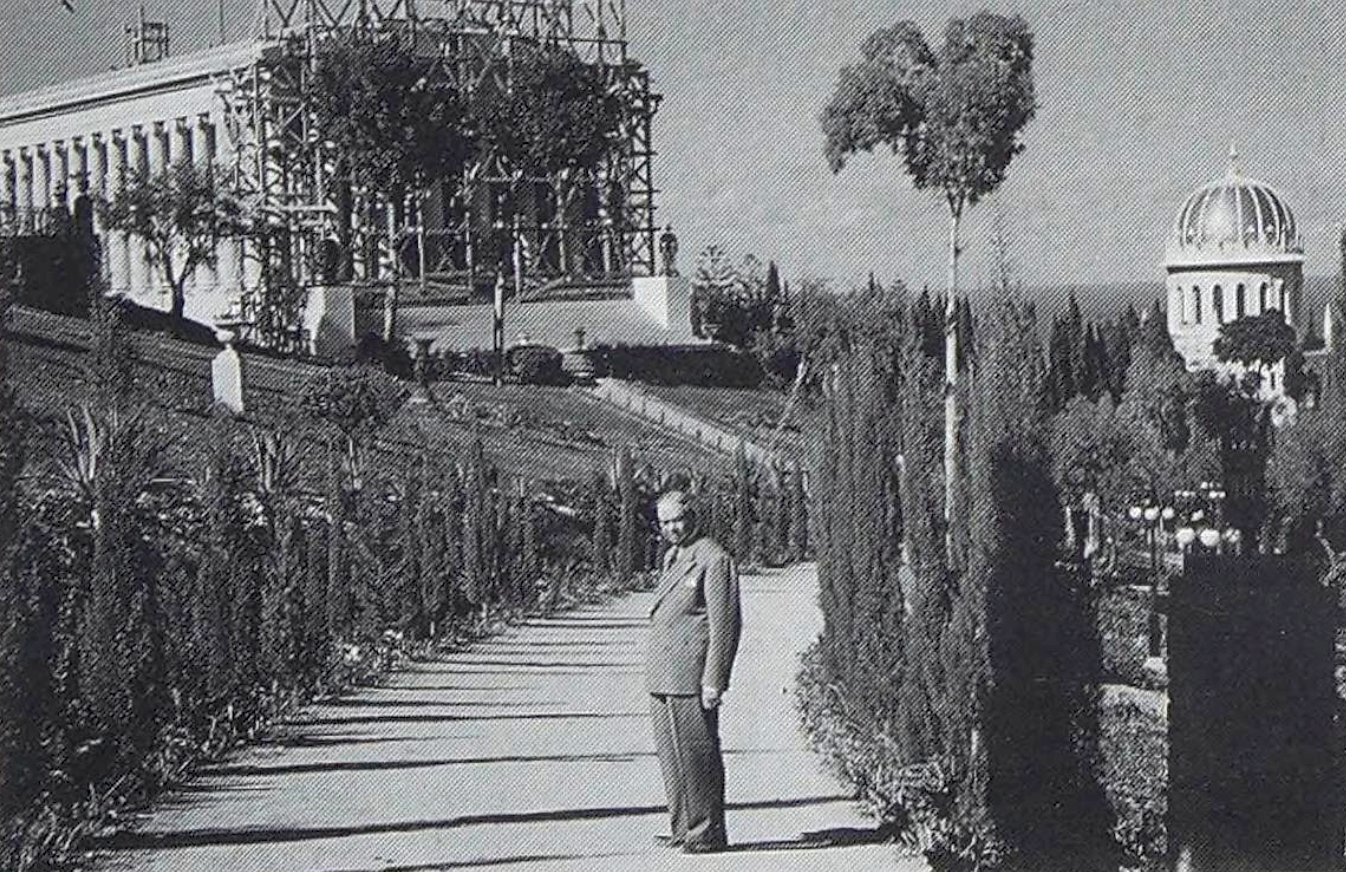

Shoghi Effendi in April 1957, standing in the garden gate of the House of the Master. He was directing the placing of the coffin of Isfandiyar—'Abdu'l-Bahá’s faithful servant and carriage driver—in the funeral cortege that was about to leave for the Bahá'í cemetery. Source: Bahaimedia.

After the thirty-fifth anniversary of the Ascension of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, Shoghi Effendi repeated many times to Rúḥíyyih Khánum:

Do you realize I have been carrying this load thirty-six years? I am tired, tired!

Hand of the Cause Leroy Ioas on the path leading to the International Bahá'í Archives. Source: Bahaimedia.

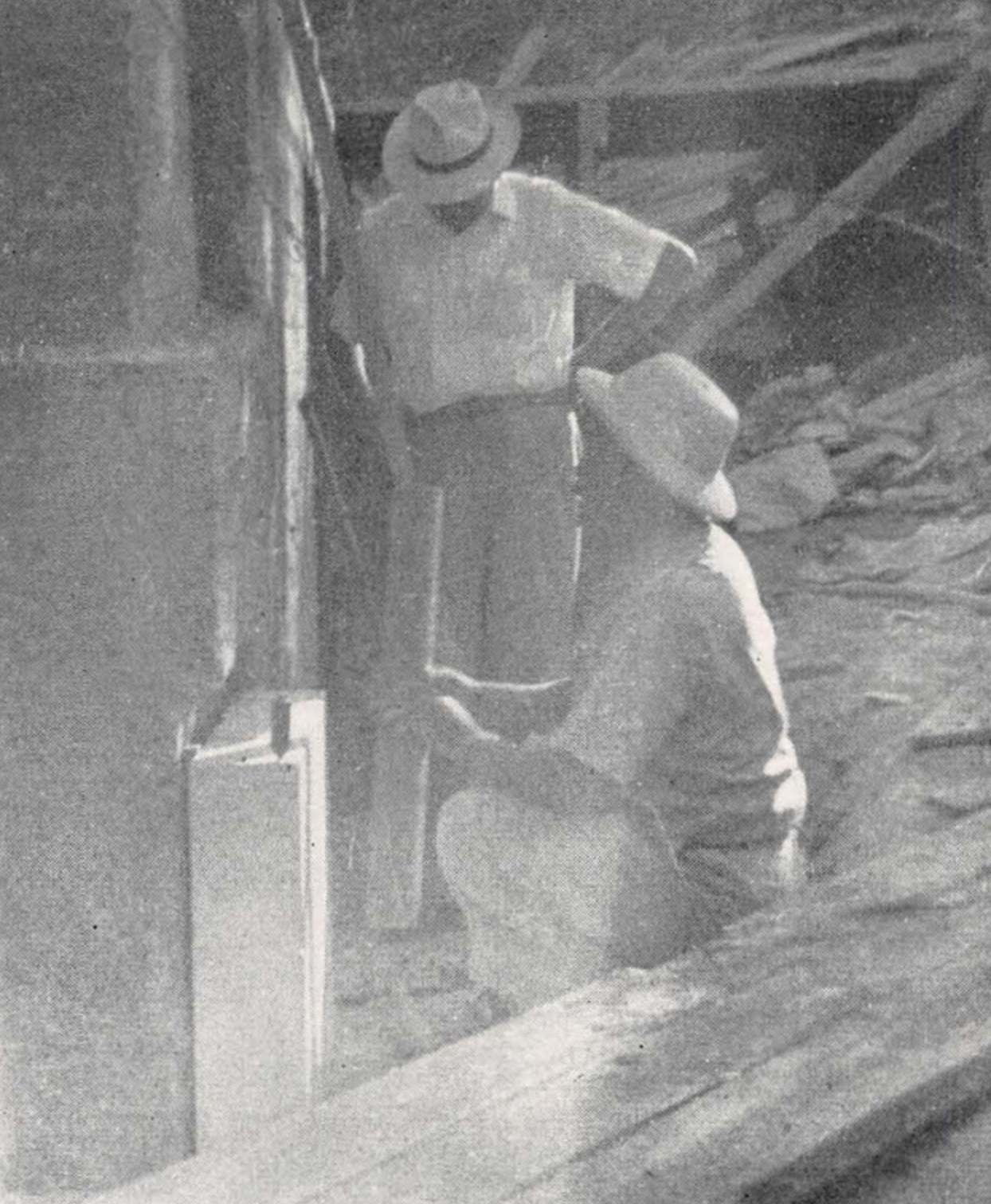

The Guardian informed Leroy Ioas, who was to supervise the work locally—as Ugo Giachery was supervising the other part of it in Italy—that the building would have to be built from the rear—where it backed into the mountain—fitting the front into the gardens that already surrounded it, for practically its full length on all three sides, leaving only about five meters’ leeway for the construction workers to maneuver in!

The Guardian oversaw the building project of the International Bahá'í Archives as Leroy Ioas was the project manager, and Abu Khalil—who was doing masterful work on the Shrine of the Báb—was the mason, but it is fair to say that the Guardian personally handled the entire project with his characteristic originality, his independent nature and his steely determination to get everything done as efficiently as possible.

The process was incredibly complicated: the International Bahá'í Archives was on a sloping hill, not on level terrain, all 52 columns were in three segments, a total of 156 pieces that had to be perfectly slotted into each other for the effect to be perfect, and Shoghi Effendi needed Leroy Ioas to build the Archives from the rear, where it backed into the mountain.

Every hurdle was overcome thanks to Leroy Ioas’s strength and ingenuity in Haifa, and Ugo Giachery’s brilliant problem-solving capacities, diplomatic and lovable nature, and his attention to detail. But the work was deeply taxing on the two Hands of the Cause, and it exhausted them to their physical limits.

Leroy Ioas was very hands-on. One day, the young nephew of Hand of the Cause Ṭaráẓu'lláh Samandarí was watching the construction and noticed the head mason and his men were working on a problem and Leroy Ioas went over to demonstrate to them how it should be done. Ṭaráẓu'lláh Samandarí’s nephew mentioned to the Guardian that the mason couldn’t fix the problem but the Hand of the Cause could, and Shoghi Effendi humorously responded:

Yes, Mr. Ioas is the invisible hand of God.

The Guardian’s response, spoken in Persian is a reference to a Muslim Ḥadíth according to which the solution to an insolvable problem is the “invisible hand of God.”

Images of the crates containing the marble, Ugo Giachery with the captain of the SS Nakhon—the ship which brought them from Italy—the unloading of the crates. All photographs from Bahaimedia: The construction of the International Bahá'í Archives. Background photograph: Front view of Archives Building, September 1956. Source: Bahaimedia.

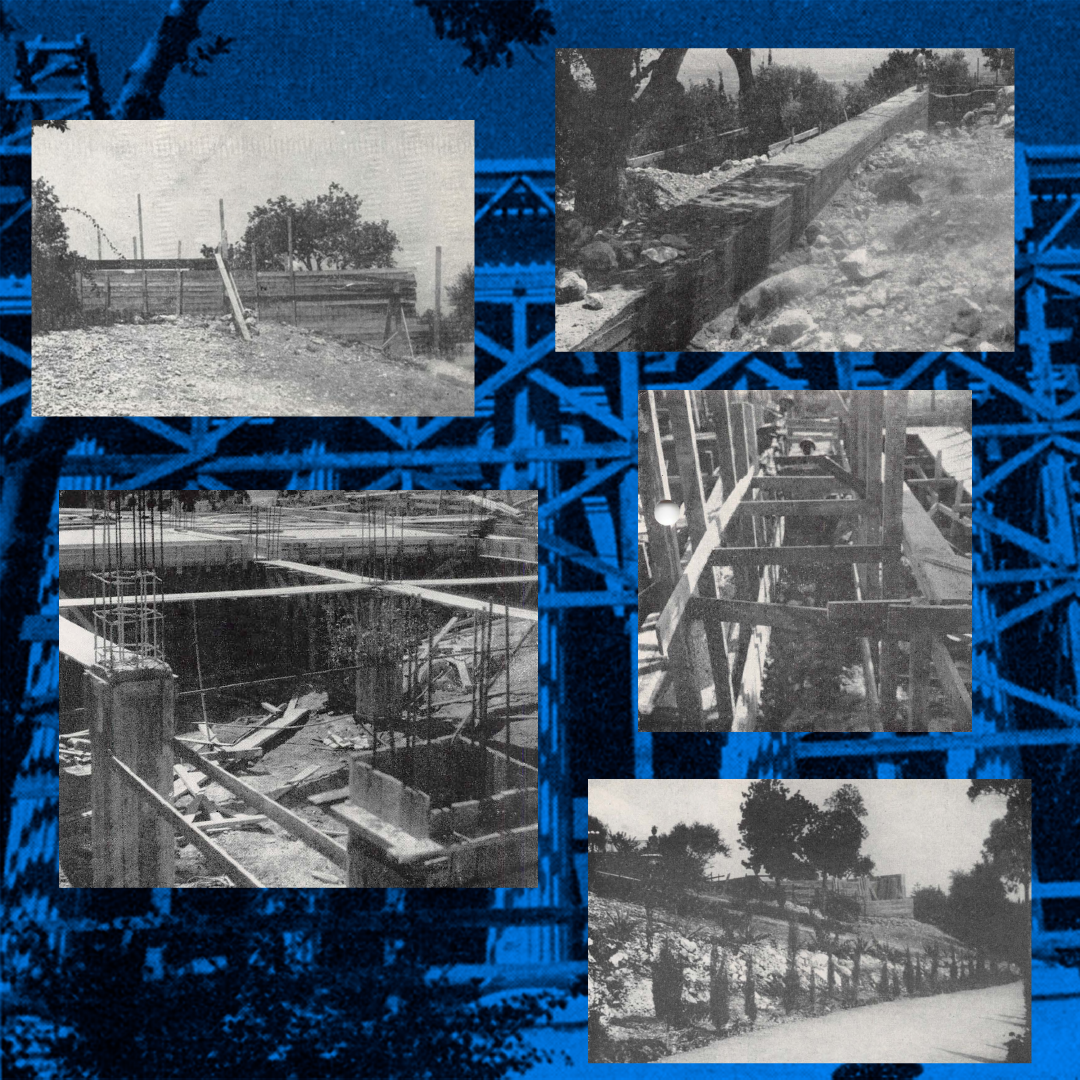

On 12 August 1955, seven months after the initial contracts were signed in Rome in January 1955, the first shipment of 100 tons of Chiampo Paglierino marble arrived in Haifa from Trieste on the S.S. Nakhson. More than 800 tons of stone were to follow during a period of a year and a half.

The next month, in September 1955, Leroy Ioas wrote to Hand of the Cause Amelia Collins:

We are working strenuously on the Archives building. At every turn there has been problem after problem but it forges ahead, and some think we are making good progress. Ugo thinks it is miraculous. The marble work on the north podium is being completed. Next will come the marble steps and then the other sections of the podium, before we can begin to set in place the fifty-two marble columns.

Among the many problems that Leroy Ioas was facing, some tested his patience to its very limits. In order to shore up the Archives building, the Guardian had ordered a huge quantity of material from the city, but the workers dumped the materials in the wrong place at the building site. Leroy Ioas was furious. His standards were exacting for all workers, Bahá'ís and Israelis.

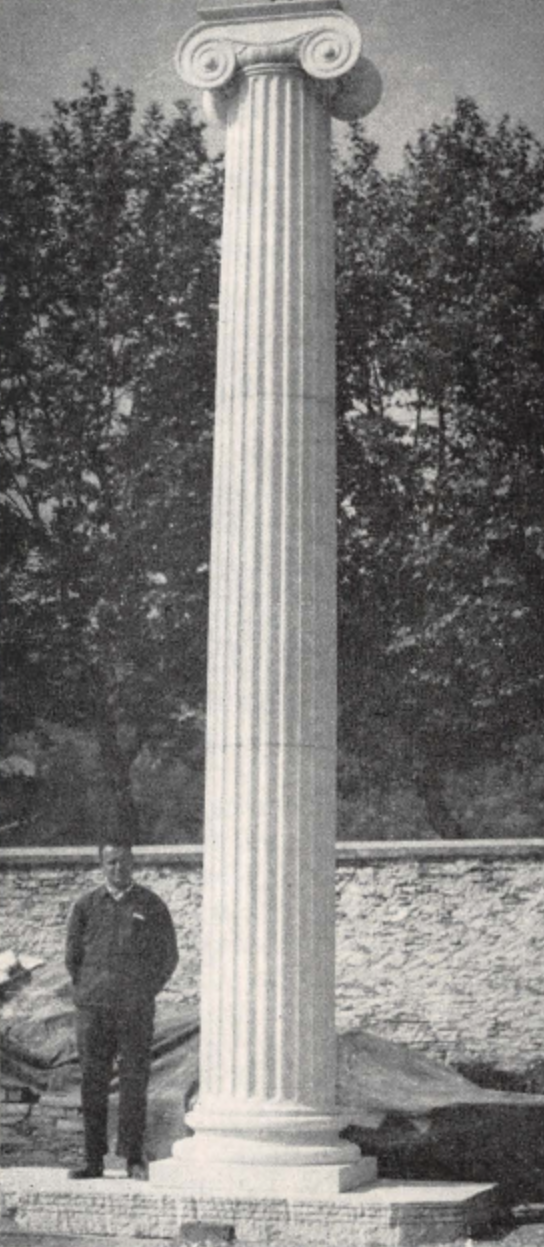

In December 1955, the first magnificent Ionic column was placed into position on the north-east corner of the podium, facing east toward the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh.

The contract for the roof tiles was signed on 6 June 1956 with the same Dutch firm in Utrecht.

The curved path or "arc" in front of the International Archives Building being constructed on Mount Carmel. Bahá'í News Issue 297, page 4.

Perhaps the greatest feat of genius of the Guardian in the innovative, fresh approach he had to constructing buildings was that he first planted gardens before the marble from Italy had even arrived and before he laid the foundation. Two years before construction began, the Guardian began planting laying out paths—with twine and pickets—as well as borders, hedges and trees on three sides of the building area.

Thanks to the Guardian’s visionary innovation, two years later, when the International Bahá'í Archives were completed, the gardens were fully mature and the stunning edifice looked as if it had been there for years—and not, as it was, just completed.

The reason the Guardian did this was because he could not bear such a masterpiece of a building to be completed surrounded by gravel and barren land. But building around a completed garden was not particularly easy for the engineers and workers. The Guardian did not care, he once even expressed his aesthetic philosophy this way:

I will always sacrifice utility to beauty.

Leroy Ioas and head mason with the first stone in place. Source: Bahaimedia.

Leroy Ioas was indispensable to the Guardian who once said he did not know what he would have done without Leroy Ioas, and that once he gave something to Leroy Ioas to do, he never again worried about it, because he knew Leroy Ioas would handle it perfectly, with his characteristic energy and attention to detail.

From the moment he had arrived in Haifa on 10 Marcy 1952, he had been working at a vertiginous pace. He was the Secretary of the Guardian, the Secretary-General of the International Bahá'í Council, he had assisted with the completion of the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb, he had traveled for the Guardian, bought dozens of tracts of land for the Faith, established the Israel Branches of National Spiritual Assemblies, he was the Guardian’s liaison with the Government of Israel.

Leroy Ioas’s work from 1952 to 1955 was, of course, enough to run anyone into the ground, but that was just the physical strain of his work responsibilities. Perhaps the element that was most difficult and painful for Leroy Ioas was the human, emotional element. For three years, he had been working on intense responsibilities while navigating the delicate balance between western and eastern culture with which he was deeply unfamiliar—Leroy Ioas had never left the United States before arriving in Haifa in 1952—the Israelis’ natural abrasiveness, an endearing quality but one he had no experience with, not to mention having to deal with Covenant-breakers over and over again while he was purchasing land for the Guardian.

After two years of this demanding routine, and ignoring his body’s warning signs, shoving his fatigue to the side, and generally increasing the intensity of his activities, Leroy Ioas had put a severe strain on his heart. Though he never suffered a heart attack, he had neglected the warning signs until his heart was permanently damaged. From 1955 onwards, he would not be able to work at the same pace as he had before.

When the Guardian heard, he insisted that Leroy Ioas leave the Bahá'í World Centre for an entire month and do absolutely nothing. This is wonderful, because whenever Rúḥíyyih Khánum found the Guardian in a state of absolute exhaustion and begged him to rest, Shoghi Effendi never would. But now, it was him giving his chief lieutenant advice he never heeded!

This happened during the Ten Year Crusade and Leroy Ioas asked the Guardian to basically pioneer to Europe where he could establish a community and deepen Bahá'ís. The Guardian said, in essence, absolutely not. He wanted Leroy Ioas to rest.

The early stages of construction the process of the International Bahá'í Archives showing the foundations and retaining walls. All photographs from Bahaimedia: The construction of the International Bahá'í Archives. Background photograph: Front view of Archives Building, September 1956. Source: Bahaimedia.

In his Riḍván message of 1955 to the Bahá'ís of the world, Shoghi Effendi updated the believers and the institutions on the progress made in the construction of the International Bahá'í Archives, explaining the expropriation process, the fixing of the position of the Arc, the field measurements for the exact position of the Archives building, the contract signed in Italy for the Chiampo Paglierino marble, and their expected date of arrival:

Following the expropriation by the Israeli Finance Minister, on the recommendation of the Mayor of the City of Haifa, of the plot adjoining the site of the future International Bahá'í Archives on Mt. Carmel, the fixing of the position of the far-flung arc, around which the edifices constituting the Seat of the World Bahá'í Administrative Order are to be built, the location of the site of the building and the preparations for the excavation of its foundations, a hundred and twelve thousand dollar contract has been signed in Rome for the quarrying, the dressing and carving of the stones and the fifty-two columns of the building which will amount in weight to over nine hundred tons and are to be shipped within less than two years to the Holy Land.

Crates of material for the Archives building on train cart in 1955. Source: Bahaimedia.

Hundreds of tons of marble were needed for the International Bahá'í Archives’ 52 seven-meter columns which formed the colonnade of the Archives, but because Shoghi Effendi needed finished stone blocks of the same shade and Chiampo Paglierino marble was found in veins of varying shades, three times as much marble had to be excavated.

The 7-meter columns could not be single blocks because they would have been impossible to ship. The stonemasons cut all the columns into three parts—weighing 2 metric tons each, ready for shipping.

As with his first experience collaborating with Italian professionals in the course of constructing the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb, the Guardian was very salified with the level of professionalism exhibited by the Italian team. A veritable little army was working on the Guardian’s materials for the International Bahá'í Archives: miners, sculptors, artisans, draftsmen, and architects, each and every one of them of the highest caliber in their field and eager to produce their best work for Shoghi Effendi.

The marble was carefully packed, and all the crates were touchingly respectively marked “S.E.” (“Sua Eminenza”: “His Eminence”), referring to the Guardian. The crates were first shipped by train in 8 railroad cars to Trieste, then loaded onto ships bound for Haifa. It took 17 ships to transport the 1,000 tons of carved Chiampo Paglierino marble.

As had been the case for the fabrication of the marble and granite for the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb, a veritable army of draughtsman, modelers, stonecutters and sculptors was mobilized, while miners in the quarries of Zanconato and Nicolato in the territory of Chiampo were wresting from the bowels of the earth hundreds and hundreds of tons of marble in huge blocks—an arduous and meticulous job. Only the most perfect marble was selected from the abundant yield of the quarries.

When Ugo Giachery witnessed the first completed column erected in his presence in the yard of the Chiampo workshop, he could not believe his eyes. The flawlessness of the Guardian’s design was standing before him in all its beauty and perfection! The workers stood around, watching Ugo’s expression—a mixture of pure joy and awe—and waiting for a word of praise.

Then, Ugo Giachery snapped out of his dreamlike state, and shook all the workers’ hands, warmly congratulating everyone, thinking to himself how the Guardian would feel when he saw the first column raised on Mount Carmel.

The first capital, "Ionic style", completed at Chiampo, Italy , on April 19, 1955, one of the 50 capitals required for the Baha'i International Archives Building on Mount Carmel. Each capital weighed 1 ton. Source: Bahaimedia.

Balustrade for balconies of the Archives Building, 1957. Source: Bahaimedia.

Shoghi Effendi had found a beautiful example of wooden balustrades in one of William Sutherland Maxwell’s books, designed by the famous 16th century Italian architect, Palladio, for the villa “La Rotunda”, near Vicenza.

The Guardian instructed Ugo Giachery to build a perfect replica of this balustrade, and Ugo Giachery immediately left for Vicenza with Professor Rocca to study the original in great detail.

They took careful measurements and made several drawings, both of which were a great help to Saiello Saielli of Pistoia, who had built the exquisite door to the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh five years earlier in 1957, and would also build the door to the International Bahá'í Archives.

Saiello Saielli chose the most perfect oak, absolutely uniform in tint and texture, then incorporated a variety of ingenious details to make the balustrade as solid and as safe as he could. After this, Saielli spent many months, skillfully and enthusiastically reproducing La Rotunda’s wooden balustrade for Shoghi Effendi, and his final work, as usually was stunning, and a priceless addition to the interior of the Archives.

When Saiello’s completed masterpiece reached Haifa and the balustrades were placed on the upper level balconies, Shoghi Effendi was incredibly pleased and highly praised their beauty and workmanship.

A view of the International Bahá'í Archives at night, with the two torch-holders on either side of the stairs clearly visible. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

Initially, the Guardian had wanted to place a large marble eagle on each side of the platform of the main entrance staircase, but he abandoned that idea in favor of two beautiful wrought-iron torch holders converted to electricity, a luminous and friendly welcome for all pilgrims. The simulated glass flames were specially made in the world-famous glass capital of Murano, Venice, Italy.

Steel beams carrying the weight of the ceiling of the Auditorium of the Baha'i International Archives Building, Haifa. The Auditorium is 10 meters wide by 24 meters long. Thirty beams each 50 centimeters high support the ceiling. Source: Bahaimedia.

The beautiful grilled inner vestibule door was a duplicate of an ancient Greco-Roman bronze door that Shoghi Effendi loved, and which perfectly fit the style of the building. The iron frame for the window and the bronze grilled door of the vestibule were made in Sarzana, Italy, by the firm of Malatesta, by the same firm that had manufactured all the lamp-posts and the various gates in the Holy Places on Mount Carmel and in Bahjí.

The original 450-square meter floor was made of green tiles of compressed cement, fabricated in Italy, but when they installed, they did not match the refinement of the Archives atmosphere and were covered with almond-green vinyl tiles made in England by Semtex Ltd., a subsidiary of Dunlop & Co. The vestibule and the staircases were made out of marble.

One of the most complex and most important steps in building the International Bahá'í Archives had been pouring the ceiling after the walls were placed into position. The ceiling was 10 meters wide by 25 meters long.

This was a problem because they had to make sure the concrete was poured in a way that would not create vulnerability in the solidity of the ceiling, or cause cracks.

In order to do it properly and ensure lasting solid results, they first poured the lower 6 centimeters of ceiling, then 37-centimeter-high beams were poured, and finally, they poured the concrete slab 8 centimeters above that.

From the moment the first shipment of stone arrived from Italy in August 1955, to the time the International Bahá'í Archives was completed in April 1957, less than two years had passed, with only the foundations and reinforced cement work of floor, walls and ceiling being manufactured in Haifa.

Collage of the various stages of construction of the roof of the International Bahá'í Archives, from the scaffolding erected to support the ceiling, to the tympanum, carved corner crowning, numbered antefixes which line the border of the roof of the Archives, a closeup on the tiles, fabricated in Utrecht, the tympanum of the east façade, steel beams supporting the roof. All photographs from Bahaimedia: The construction of the International Bahá'í Archives. Background photograph: Front view of Archives Building, September 1956. Source: Bahaimedia.

After the ceiling, the next major project was the roof itself, 500 square meters with 270 carved stone antefixes—ornaments at the eaves of classical buildings that served a dual purpose to embellish the roof and conceal the joints of the roof tiles.

Shoghi Effendi wanted lovely verdigris green tiles for the roof, and placed a $15,000 order—$172,000 in today’s currency—for 7,892 ridged green tiles from the Dutch factory in Utrecht, which had made the golden tiles for the dome of the Shrine of the Báb. It took the factory 8 months of testing to produce the proper shade of green and as identical as possible in size and shape to the antique original tiles. The tiles alone weighed 45 tons and had to be specially packed for shipping.

Shoghi Effendi was delighted with the final tiles. The color he had chosen, on clear days, blended with the sky, and the roof was a masterpieces with its front and back tympana, each topped at its apex by an anthemion—radiating petals—and connected to the edge of the roof by 235 carved acroteria—ornaments—with four additional anthemia at the four corners. The Guardian loved the roof so much, he was inspired to call it yet another crown.

Gorgeous photograph showing the distinctive sea-green color of the roof tiles and the tympanum with radiating golden rays around the Greatest Name. Photograph by Farzam Sabetian. Source: Luminous Spot: The Arc.

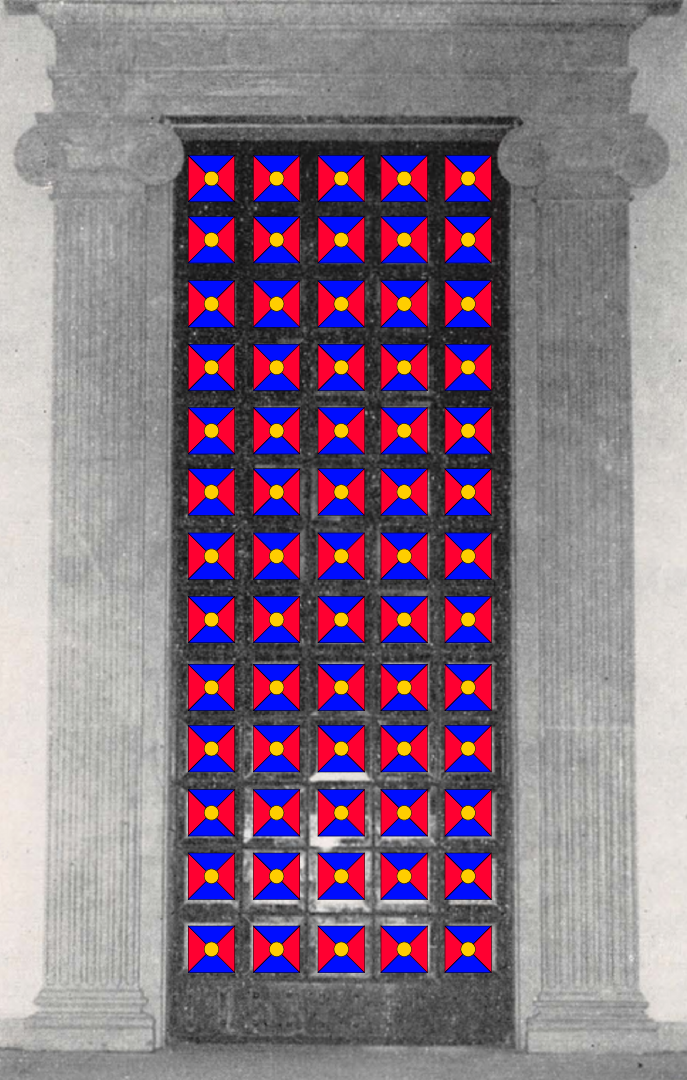

Black and white photograph of the large stained glass window of the International Archives, placed in position. The panels are of stained glass with a deep gold spot in the center, and red and blue panels, colored panels added in Adobe Illustrator to provide a sense of the brilliance of the colors in Shoghi Effendi’s design. Source: Bahaimedia.

The artist of the monumental stained glass masterpiece was Professor G. Gregorietti , who taught at the Palermo Accademia di Belle Arti (Palermo Academy of Fine Art) and an associate professor of the School of Architecture of Palermo University, in Sicily—Ugo Giachery’s native island. Professor Gregorietti’s specialty was producing rare and highly artistic decorative stained glass panels artwork.

Before work on the stained glass panel began, Ugo Giachery sent Shoghi Effendi many samples of stained glass sent to him from Italy and other European countries, from which the Guardian handpicked his colorway for the stained glass wall: yellow, red, blue, and clear glass.

Ugo Giachery traveled to Sicily to meet Professor Gregorietti, who expressed his willingness to take on this highly unusual commission. Ugo Giachery informed him of Shoghi Effendi’s color choices, and reported back to the Guardian including samples of the final stained glass colors along with a full-scale drawing of a single panel, and the estimate for all 65 panels. The final design for each panel consisted of a golden amber disk surrounded with ruby-red and royal blue panes alternating with clear glass pieces.

Professor Gregorietti worked alone in his vast and modern workshop in Palermo where he completed the work on the stained glass window meticulously, including operating the kilns and soldering the hundreds of meters of lead alloy binding for the glass.

During the months Professor Gregorietti was working on the stained glass panel, Ugo Giachery traveled to Sicily several times to check on his work and ensure its quality, as well as overseeing the final packing and shipping once the panels were all completed.

The stained glass panel—once assembled into position in the International Bahá'í Archives—was exquisitely perfect.

Color photograph of a rosace detail from the door to the International Bahá'í Archives. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023. Plaster model of the same detail prior to wood-carving. Source: Bahaimedia. Full-length photograph of the door after its arrival in Haifa in October 1956. Source: Bahaimedia. Background photograph: Front view of Archives Building, September 1956. Source: Bahaimedia.

The door the Guardian chose for the International Bahá'í Archives was a masterpiece of ingenuity. It was a monumental 3.80 by 1.80-meters Greek-style bronze double door, weighing almost two dons, faced with oak on the inside of the Archives. Each of the outer doors had the same pattern: 10 square panels was studded, large gilded rosettes, 30 centimeters in diameter, and each door was symmetrically studded with knobs.

Before embarking on the construction of the door, Ugo Giachery visited Roman sites to closely examine the most ancient Roman doors still in use, and concluded that the Archives’ door should be made of hard wood covered with heavy plated bronze and the outer ornamentation should be cast in solid bronze.

A reputable sculptor from Carrara made an actual-size model of one panel from which a full-scale model of the door was made for the Guardian to approve, after which the model served as a guide for the artisans. The Guardian chose the well-known Italian foundry of the firm of Renzo Michelucci for all the bronze work, and the firm of Saiello Saielli for the woodwork—this firm had built the door of the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh in late 1952— both of which were in Pistoia, not far from Florence. As with the door for the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh, Saiello Saielli took great pains to ensure that the oak was well-seasoned and bone-dry.

The door was built with wooden pegs and copper nails to further decrease any possibility of damage produced by iron rust, and the wood being treated with special oil and wax.

During the six months it took to build the Archive’ door, Ugo Giachery traveled the 300 kilometers from Rome to Pistoia very frequently to check and report back to Shoghi Effendi regarding the progress of the work, the bronze casting, the gilding of the rosettes, and the packing of the two half-sections of the door in a huge crate for shipment to Haifa.

The gilder for the decorative knobs and rosettes was the same Florentine artisan who had gilded the Greatest Name monograms on the arcade of the Shrine of the Báb, first silver plating the bronze, and then fire-gilding it.

As with the door to the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh, the door of the International Bahá'í Archives could not be installed with conventional hinges, and Ugo Giachery ordered the same special ball-bearing hinges, made of the finest steel, which allowed opening and closing of the door with the least amount of effort.

Once completed and installed, the door of the International Bahá'í Archives was a masterpiece, and Shoghi Effendi was able to see it in place in the early summer of 1957.

The completed, stunning International Bahá'í Archives. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

On 21 April 1957, the Guardian announced the completion of the International Bahá'í Archives to the Bahá'í world, but construction would not be totally completed until June, two months later:

The remaining twenty-two pillars of the International Bahá'í Archives—the initial Edifice heralding the establishment of the Bahá'í World Administrative Center on Mt. Carmel—have been erected. The last half of the nine hundred tons of stone, ordered in Italy for its construction, have reached their destination, enabling the exterior of the building to be completed, while the forty-four tons of glazed green tiles, manufactured in Utrecht, to cover the five hundred square meters of roof, have been placed in position, the whole contributing, to an unprecedented degree, through its colorfulness, its classic style and graceful proportions, and in conjunction with the stately, golden-crowned Mausoleum rising beyond it, to the unfolding glory of the central institutions of a World Faith nestling in the heart of God's holy mountain.

A front-facing photograph of the International Bahá'í Archives. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

Various stages of the construction process of the International Bahá'í Archives, as the walls are raised, the stairs are installed, and the roof is built. All photographs from Bahaimedia: The construction of the International Bahá'í Archives. Background photograph: Front view of Archives Building, September 1956. Source: Bahaimedia.

From the moment the first shipment of stone arrived from Italy in August 1955 and the first column was raised in December 1955 on the northeast corner of the podium directly facing Bahjí, until the International Bahá'í Archives was fully completed in June 1957, less than two years had passed.

The entire building had been prefabricated in Italy and assembled in Israel, with only

the foundations and reinforced cement work of floor, walls and ceiling being manufactured locally.

The Archives building was utterly stunning, skirted by 52 Ionic marble columns, its bright green roof of glazed tiles, the gold of its sunburst and Greatest Name gleaming against the blue of the Mediterranean.

- 17 ships carried 1,000 tons of marble from Italy to Haifa.

- Many, many other ships transported the structural steel, cement, floor and roof tiles, lumber, stained and clear glass, small and large iron window-frames, varnish and paint for the interior, chandeliers, electric and other wires, the main and the vestibule bronze doors, the oak balustrades and plinth for the balconies, lamp-posts and many other items, such as chain-lifts, nails, drain-pipes.

- Each marble column weighed 6 tons, and had to be assembled from three parts, each weighing 2 tons.

- Each column capital weighed 1 ton.

- Each of the six anthemia— an ornamental design of alternating leaf patterns— also weighed 1 ton each.

- The roof tiles weighed 40 tons and were packed in 7,200 cardboard boxes and padded with 25 kilometers of gummed paper strips

- The first load of marble left from the port of Trieste on the S.S. Nakhshon, of the Zim Line, under the command of Captain Israel Auerbach, on 10 August 1955, barely 7 months after the contract was signed with 169 cases ferried in 8 filled railcars.

Some months before his passing, the Guardian sent Ugo Giachery a moving, grateful cable:

Congratulate you splendid historic highly meritorious achievement ensuring execution details structure Archives particularly Greatest Name. Present future generation believers including myself profoundly grateful.

A collage of all photographs of workers on the International Bahá'í Archives that were found in Bahaimedia: The construction of the International Bahá'í Archives. Background photograph: Front view of Archives Building, September 1956. Source: Bahaimedia.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum, in her article in The Bahá'í World volume 13 on the completion of the International Bahá'í Archives, makes a stunning point about the team which built this incredibly beautiful work of art in just 2 years.

She remarks, rather brilliantly, that the team which built this exquisite edifice was composed of ignorant, untrained gardeners, an Italian chauffeur, an ex-railway executive—Leroy Ioas—a Ph.D. in chemistry—Ugo Giachery—and an elderly architect with little experience in such a large construction project—Dr. Andrea Rocca, Professor Emeritus of the Beaux Arts Academy of Carrara:

When one stands to the east and sees the early-morning light glancing along the gilded rays of the sunburst on the tympanum and catches the flash of the golden Greatest Name monogram blazoned on the green mosaic sun in the centre of nineteen pointed star, one marvels anew at that perfect sense of proportion, that innate flair for beauty, which so strongly characterized every undertaking of a man who was born a prisoner in ‘Akká, visited the West for the first time at twenty-three, had little contact with art and no formal training at all in its forms. When one recalls that this building and its gardens were realized through the instrumentality of ignorant, untrained “gardeners”, an Italian chauffeur who carried out the instruction of his employer standing directing him, an ex-railway executive, a doctor of chemistry and an old man who, though an architect, had had little experience in such undertakings, one bows one’s head before the inborn genius and determination of the Guardian.

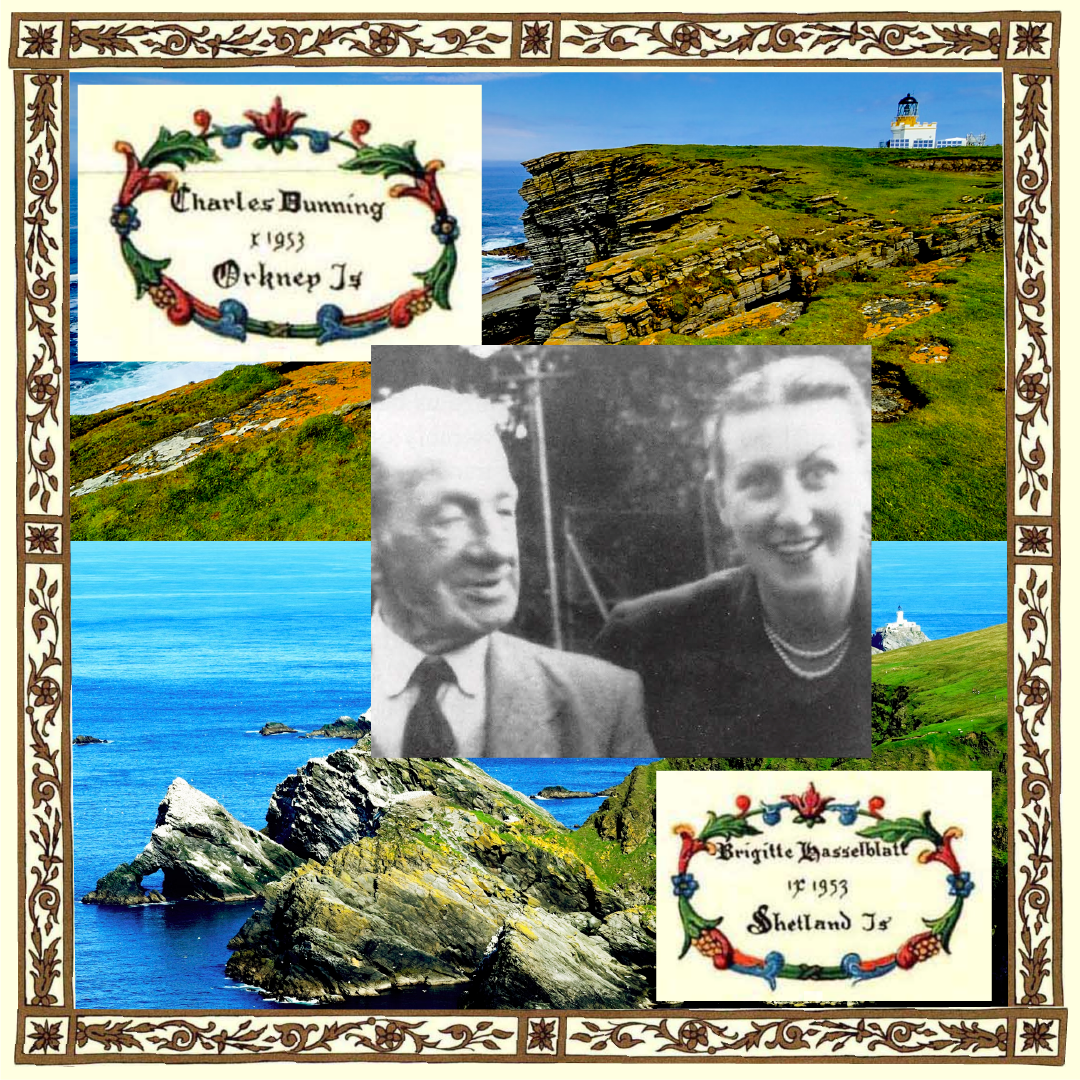

In 2023, Dr. Keith Munro published a biography of Charles Dunning, the Knight of Bahá'u'lláh to the Orkney islands, which is the main source for this section on Charles Dunning’s pilgrimage to the Holy Land in January 1957.

Dr. Munro’s book is a labor of love and dedication, filled with respect for this extraordinary hero of the Ten Year Crusade and is a thrilling read.

The isolated Orkney Islands, where Charles Dunning pioneered during the Ten Year Crusade, becoming a Knight of Bahá'u'lláh for the Islands. Photo by d kah on Unsplash.

Charles Dunning—whose job had been ship’s cook in the Merchant Navy—became a Knight of Bahá’u’lláh for the Orkney Islands, when he was the first Bahá'í to set foot there on 9 September 1953, winning a victory for Shoghi Effendi during the Ten Year Crusade. When Charles Dunning had discovered Bahá'u'lláh enjoined pilgrimage on Bahá'ís, he wrote to the Guardian, apologizing that he would not be able to perform pilgrimage because he had no money.

The Guardian paid for Charles Dunning’s pilgrimage himself. As Charles Dunning described it, the Guardian had “made the arrangements.”’

Charles Dunning was meant to sail to Haifa from Cardiff on the Israel cargo ship S.S. Geffer but there was a mix-up in his medical records and he was unable to board the ship, so he boarded a plane. During the trip, Charles Dunning made friends with many of the passengers and an air hostess who gave him her picture.

He arrived in Tel Aviv by plane on 7 January 1951 at 11:35 AM, and found no car waiting for him. Shoghi Effendi, Rúḥíyyih Khánum, and the staff of the House of 'Abdu'l-Bahá knew to expect Charles Dunning’s arrival, but they didn’t know when. Charles only had Scottish bills, and had a difficult time exchanging into Israeli Pounds, and an even harder time finding a taxi to take him to Haifa.

The taxi driver liked Charles Dunning so much they stopped for tea at the start of the journey, and soon, Charles Dunning was in Haifa, on Haparsim, at his destination.

His pilgrimage had begun.

“I am Charles Dunning. I am the pioneer from the Orkney Islands.” Background photo of the lighthouse at Kirkwall in the Orkney Islands by Mustang Joe on Flickr (license CC0 Public Domain Dedication).

Just before dinner on 7 January 1957, the doorbell rang at the western Pilgrim House.

Leroy Ioas, who was near the door, opened it and saw a very small man, who looked like a sailor, wearing a very large turtleneck sweater. Charles Dunning must have looked quite terrible because Leroy Ioas thought he was a bum who had rung the doorbell to ask for money.

Leroy Ioas was about to send him around to the side entrance of the house where the poor were often provided with food, when he suddenly thought changed his mind and asked him:

Yes? Is there anything that we can do for you?

Charles simply said:

I am Charles Dunning. I am the pioneer from the Orkney Islands.

Well, come right in.

Leroy Ioas realized with both shock and embarrassment that the man in front of him, whom he had so badly misjudged, was the Knight of Bahá’u’lláh they had been expecting the last few days.

Charles entered the western Pilgrim House, and the two sisters Ethel and Jessie Revell—members of the International Bahá'í Council—entered and spoke with Charles of his airplane trip and the friends in England.

Leroy Ioas took Charles Dunning to his room, informed him the Guardian would be arriving for dinner soon, and said:

Well, we are getting ready to go down to have dinner with the Guardian, and do you think maybe you want to change your clothes and clean up a little bit for the Guardian?

Charles Dunning responded:

Yes, I will. I will.

Leroy asked him if he had brought suitable clothes. Charles Dunning beamed and, gesturing to his old and worn suit, said:

Yes, I have.

Portrait of Charles Dunning. Source: Bahá'ís of Orkney.

Charles Dunning arrived for dinner wearing the exact same clothes he had arrived in.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum had arranged the dinner table in the western way: the Guardian would sit at his usual seat, from where he could see everyone at the table, Rúḥíyyih Khánum always sat next to Shoghi Effendi and his other secretaries, ladies who had arrived before Charles Dunning and several elderly Americans were seated closer to the Guardian, and Charles Dunning was seated further down. This all seemed perfectly logical to Rúḥíyyih Khánum.

The Guardian arrived in the dining room with his usual swish of elegance, put his arms around Charles Dunning, kissed him—something that the Guardian NEVER did—and said, with his arm around Charles’ shoulder:

You’re a Knight of Bahá’u’lláh, and you deserve to be at the head of this table.

Charles Dunning was still beaming as Shoghi Effendi led him to his seat of honor immediately to his right.

All the lades scattered further down the table to make room for Charles Dunning who was now sitting at the head of the table. Sitting there and watching the scene unfold, the Guardian’s love and respect for Charles Dunning, his Knight of Bahá'u'lláh, and his understanding of proper Bahá'í—not cultural—etiquette, she thought to herself:

Now look, isn't that just typical? You had the standard of the world. You went according to your culture and your background…This is the way it ought to be.

Leroy Ioas, too, learnt a lesson that night. He would later say that he felt like a 5 cent coin. He had judged a Knight of Bahá'u'lláh based on material standards and the Guardian had judged him with the standard of Bahá'u'lláh.

Steps leading up to the door of the Western Pilgrim House at 10, Haparsim, in Haifa, where Charles Dunning had his first dinner with Shoghi Effendi on 7 January 1957. Source: Bahaimedia.

Charles Dunning had created an entire image of what the Guardian would be like in his head—dignified and serene—and when he encountered the reality of the who the Guardian was, he discovered the spiritual reality of Shoghi Effendi, and described it beautifully:

He was possessed of a human touch which you could feel. And in my first meeting with him I was happy right away.

The dinner guests were fascinated: Charles Dunning sat at the head of the table, watching Shoghi Effendi, his beloved Guardian, with his arms on the table, leaning in into the Guardian’s personal space, wagging his finger almost under his nose, saying:

Guardian do you remember when you wrote that?

The pilgrims and staff were also fascinated because Shoghi Effendi was leaning into Charles Dunning absolutely beaming and enthralled, and he, too, had his arms on the table, something that Rúḥíyyih Khánum had never seen in 20 years of marriage. The Guardian was laughing and joking, and smiling, and talking to Charles Dunning in a way that astonished even his wife.

Shoghi Effendi and Charles Dunning were having a wonderful, unforgettable dinner. Charles Dunning was so thrilled, so awestruck that he held his soup spoon up to his mouth, but he was staring at the Guardian and kept raising his hand. Watching this, Rúḥíyyih Khánum thought:

In one more minute, he's going to pour this soup in his ear. Oh God, oh God, oh God!

In the end, when Charles Dunning saw where his soup spoon had gone, he was very surprised and put it in his mouth.

During this first dinner, Charles Dunning told Shoghi Effendi about the air hostess he had taught the Faith to on the plane to Tel Aviv and showed him her photograph. The Guardian asked Charles Dunning:

Can I have it?

Charles Dunning was overjoyed. He felt as if the air hostess he had taught the Faith had spiritually entered the Faith at that moment.

Charles Dunning was delighted to discover that Shoghi Effendi and Rúḥíyyih Khánum had a wonderful, very funny sense of humor, and he recalled there wasn’t a single dinner at the Pilgrim House when there weren’t peals of laughter.

“He overlooked faults.” The attitude of the Guardian illustrated by these three words, placed exactly over an advertisement for American cigarettes on Times Square in New York. Photogrpah by John Vachon. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Charles Dunning, a through and through Yokrshireman, was completely himself during his entire pilgrimage, and one night, he managed to appall all the Bahá'ís at the dinner table with a single gesture.

After the meal, Charles Dunning pulled a cigarette butt out of his pocket, impaled it on a needle, and began to smoke it with great enjoyment.

The only person that was in no way shocked or appalled was the Guardian himself, he was only very curious at what Charles Dunning was smoking and asked him why he was smoking a cigarette butt.

Charles Dunning replied:

I am a poor man and I have to use everything to the very last in order to get by.

The next evening, Fujita placed a brand new pack of American cigarettes beside Charles Dunning place.

It had been placed there at the Guardian’s request.

The whole “smoking incident” had taught a profound and important lesson to everyone at the table, by not criticizing Charles Dunning’s lifelong smoking habit—he must have started smoking when he was 7 and he was now 71 years old—which would have hurt him, or worse, alienated him.

Shoghi Effendi had chosen to overlook the small fault of a spiritual giant, a Knight of Bahá'u'lláh, a true hero of the Ten Year Crusade who had won inestimable victories for his Guardian, a humble and hardworking man who had given his whole heart to Bahá'u'lláh.

The Guardian was always focused on the inner being of the Bahá'ís, he loved and he overlooked faults.

“A gift from the Guardian.” Note: This is not the ring Rúḥíyyih Khánum gave to Charles Dunning. Background photograph: 18th century ring from Europe, gift of Mr. Lee Simonson, 1944. Source: The Met.

One evening, the Guardian told Rúḥíyyih Khánum he had a stone and wanted her to go to Haifa and have it mounted on a ring by a jeweler. When Rúḥíyyih Khánum got to the jewelry store, the jeweler told her the work would take a week, but Rúḥíyyih Khánum insisted she needed it that day, because it was a gift for someone who would be leaving Haifa in a few days.

The jeweler mounted the stone on a ring while Rúḥíyyih Khánum was in his shop.

When Rúḥíyyih Khánum returned, she showed the ring to Charles Dunning, and he was delighted.

Then, Rúḥíyyih Khánum put it on his finger. It was a gift from the Guardian.

Photograph of the door to the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh, where Charles Dunning guided pilgrims and visitors. Photograph by Farzam Sabetian. Source: Luminous Spot: The Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh.

Charles Dunning’s experiences at the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh, at the Shrine of the Báb, the prison cell of Bahá'u'lláh in the Most Great Prison, the Temple Site on Mount Carmel, and staying over one night at the Mansion of Bahjí would stay with him forever. They touched his heart and his soul. He was also privileged to be taken on a tour to the top of Mount Carmel by Rúḥíyyih Khánum herself.

Charles Dunning was a very independent and original character. He once asked Shoghi Effendi if he could go out exploring Haifa on his own, and the Guardian allowed it. He mixed with Arabs and Jews, and met children who could speak English. They translated what Charles Dunning was telling them for the adults, and they all spent a lovely time together and Charles felt he had made many friends. He would later say he was proud he had asked the Guardian if he could go into Haifa by himself and counted that outing as one of his greatest moments.

The Guardian asked Charles Dunning and Bobby Leedham to guide visitors at the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh for two days. Charles Dunning had a counter to record how many visitors entered the Shrine. On one of the two days, a group of children came with their teachers, and the children were so small, it would have been impossible to get them to remove their shoes and put them back on, so Charles suggested they peak inside the Shrine from the threshold of the door.

On another day, an American wanted to take three selfies in front of the Shrine and popped his pipe in his mouth. Charles Dunning asked him to take it out, but he was surprised when he recounted the story to Shoghi Effendi that the Guardian said he would not have asked the man to remove his pipe.

The Guardian arranged for something deeply meaningful for Charles: a special visit to Nazareth, so he would have something to share with Christians when he returned to Cardiff, Wales. In Nazareth, Charles visited the house of Mary, mother of Jesus Christ, a holy place that profoundly moved and impressed him with its massive pillars and vaults.

Charles Dunning’s pilgrimage was an infinite learning experience. He learned a lot from future member of the Universal House of Justice Luṭfu’lláh Ḥakím, Salah Jarrah, Ethel and Jessie Revell,

Charles Dunning’s place on the Roll of Honor as Knight of Bahá'u'lláh for The Orkney Islands, and his close friend Brigitte Hasselblatt, Knight of Bahá'u'lláh for the Shetland Islands. A photograph of Charles Dunnign and Brigitten Hasselblatt taken around 1954. Source: The Bahá'í World Volume 20, page 102. Top background photograph: The Orkney Islands by Maxwell Andrews on Unsplash. Bottom background photograph: The Shetland Islands by Lia Tzanidaki on Unsplash. Border created out of assets from the Roll of Honor.

The Guardian showed Charles Dunning the Roll of Honor of the Knight of Bahá'u'lláh and described to him what a pioneer was:

You were a first a dot.

Charles Dunning heard “dog” and said:

I didn’t think you thought I was a dog.

The Guardian burst out laughing, joined by Rúḥíyyih Khánum and the rest of the guests.

The Guardian explained he was first a dot, then a pioneer, then he was made a Knight of Bahá'u'lláh, the he became a conqueror.

Charles Dunning recalled his emotion when he heard the Guardian say “conqueror”:

That minute I was proud.

When the Guardian showed Charles Dunning the Roll of Honor, Charles Dunning asked to see the name of his good friend Brigitte Hasselblatt—Knight of Bahá'u'lláh to the Shetland Islands—and Shoghi Effendi teased Charles, saying:

You mean your girlfriend don’t you?

The best story was what happened when the Guardian shared his map of the Ten Year Crusade with Charles Dunning and the pilgrims. This is a story of Yorkshire’s directness and outspoken informality.

The Guardian was explaining that this map of the Ten Year Crusade showed the progress that had so far been accomplished.

The Guardian made a joke about the ambitiousness of the plans of the Ten Year Crusade—it was a tough ask for the Bahá'ís of the world—and he intimated that when the Bahá'ís saw his map, they would be very upset and unhappy with him.

Charles’s instant response to the Guardian was Yorkshire slang:

Bunkum, Guardian, bunkum.

“Bunkum” is a Yorkshire word for “nonsense.” What Charles Dunning was saying, would translate into full sentences in English as “Nonsense! How on earth could anyone even think that!” or, “Don’t be silly Guardian, no one would think that.”

The Guardian probably never found out what “Bunkum” meant in York slang, but he perfectly understood Charles Dunning’s reaction from his tone of voice.

Charles Dunning had told his beloved Guardian that Bahá'ís adored him and would always be devoted to him, no matter what the task was that he put before them, humble or majestic, attainable or heroic.

Charles was dead-right, of course. The Bahá'ís would be elated.

Portrait of Charles Dunning. Source: Bahaipedia.

Charles was a charming, funny, very down-to-earth, energetic man. He was in his 70s when he came on pilgrimage. He was originally from Yorkshire, and spoke with that delightful and most distinctive among all English accents. He was full of energy. He was a character and he left an impression on everyone who met him.

For as long as Charles Dunning’s pilgrimage lasted, every night when Shoghi Effendi and Rúḥíyyih Khánum walked home across Haparsim Street to the House of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, Shoghi Effendi would say:

Oh, I like that man so much. He's such a fine man. I like him so much.

Shoghi Effendi was not in the habit of praising Bahá'ís in that way.

Charles Dunning was just an extraordinary human being, he was blue collar, he was simple, he was poor, but he was happy in spirit. Perhaps Shoghi Effendi loved him so because he was closer to the types of people 'Abdu'l-Bahá spent a lifetime loving, guiding, caring for, and ministering, than most of the Bahá'ís he met as Guardian.

After Charles left Haifa, the Guardian said:

He is one of God's heroes.

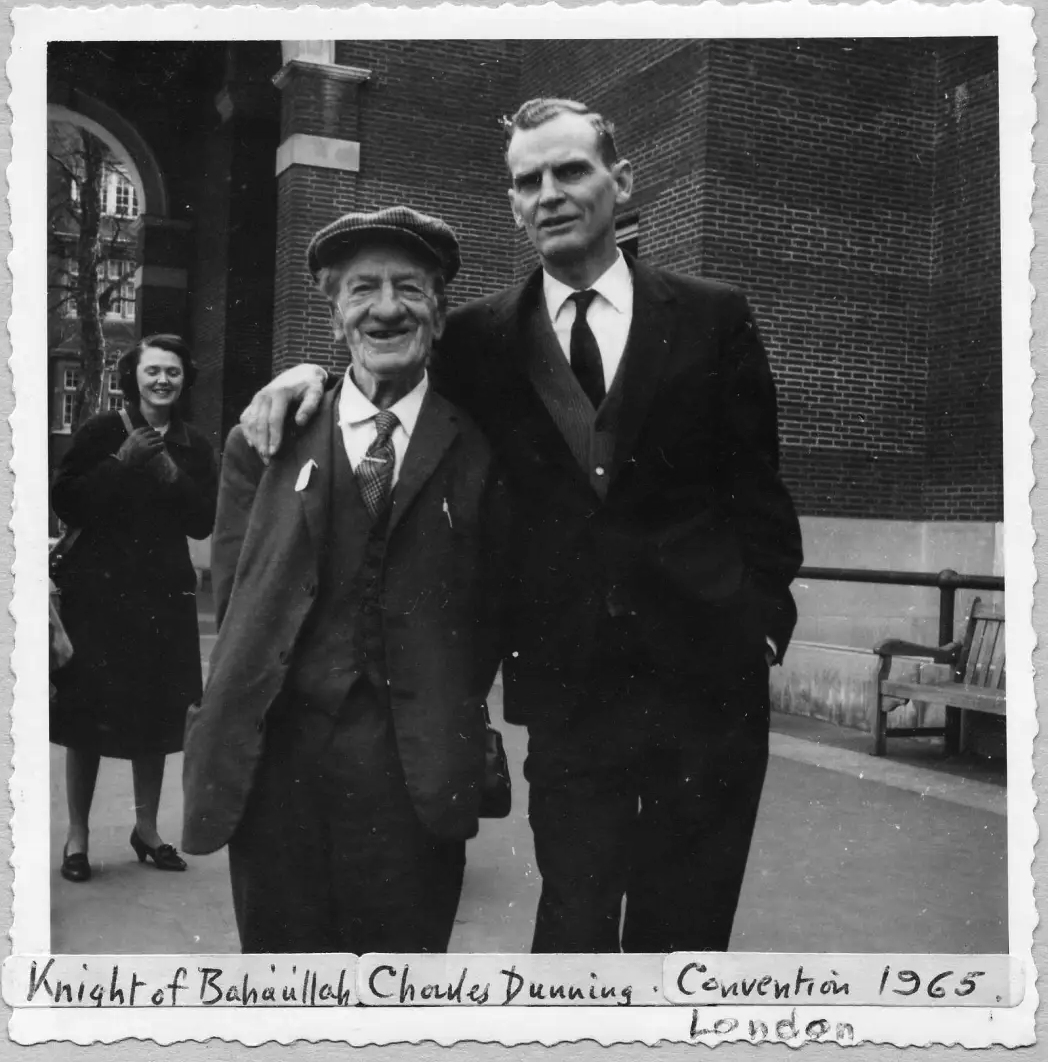

Charles Dunning with Knight of Bahá’u’lláh for South West Africa (Namibia) Ted Cardell at the 1965 National Convention for the United Kingdom. In the background is Alicia Cardell. Source: UK Bahá’í Histories.

After his pilgrimage, Charles Dunning wrote a pen-portrait of Shoghi Effendi, filled with his love for his Guardian and inspired by the profound experiences he had lived during his pilgrimage in the Holy Land. The following are all of Charles Dunning’s words, a compilation of his observations on the Guardian during his pilgrimage which started on 7 January 1957, the testimony of love for a Guardian who required his love a thousandfold:

What impressed me mostly was how he had studied everything in detail. As we all sat there you was at your ease, for events came so easily as he is telling you, with his map unfolded. He was pointing out what he had done and what he is intending doing in his 10-year Plan. It was with ease, and you was also at ease. And it is this I am trying to think of him…

When he asked me if I had gained from my visit I replied: “It is how you feel yourself spiritually when you go into the Shrine,” and he said yes that is true. How this consoled me. I felt so happy in his presence. And it is this now which makes me so happy…

[Each] night, when you was in his presence, he was so eager to know where you had been and what you had seen…

He said he had a great love for the British Bahá’ís we have a lot to be thankful for when we think of that…

“he becomes like a tree bearing fruit through the power of God” Background image from Pexels.

Regarding what Charles Dunning learned from the Guardian about how to teach, he had this to say:

This food [the message of the Bahá'í Faith] is to be offered for the sake of God, only, not for the hearer’s sake, not for the benefit of yourself: but simply because God wishes His Manifestation to become known and to become loved by those who come to know Him.

If one teaches one whom he loves, because of his love for him, then he will not teach one whom he loves not; and that is not of God.

If one teaches in order to derive the promised benefit to himself, this too is not from God. If he teaches because of God’s Will that God may be known, and for that reason only, he will receive knowledge and wisdom, and his words will have effect – being made powerful by the Holy Spirit, and will take root in the souls of those who are in the right condition to receive them.

In such a case the benefit to the teacher in growth is as ninety per cent compared to the ten per cent of gain to the hearer, because he becomes like a tree bearing fruit through the power of God.

Músá Banání and ‘Alí Nakhjávání at the Kampala Temple Site in 1957. Source: Bahaimedia.

‘Alí Nakhjávání left Uganda to come on pilgrimage in January 1957. There were 5 other men in his pilgrim group, and one day, after having visited Bahjí in the morning, they arrived in Haifa in the afternoon. From the Eastern Pilgrim House, they saw Shoghi Effendi was in the gardens, and when he signaled for them to join him, they ran to reach him, as he was walking in the gardens near the Shrine of the Báb.

One of the pilgrims was an elderly gentleman, and when they arrived in front of Shoghi Effendi, he began coughing, and coughing. The younger pilgrims—including ‘Alí Nakhjávání—stood behind him. Shoghi Effendi stopped, turned, and told the old man:

You are tired.

The man answered:

Beloved Guardian, we were tired, now that we are in your presence, all our fatigue has vanished.

The Guardian did not like this answer at all, but nonetheless told the old man very lovingly:

Why did you say this?

The poor man did not what to do or what to say, he was ready to crawl into a hole and disappear. There was absolute silence. Then, with the same loving and tender tone, the Guardian said:

What you should have said was: we were tired, but now that are in the precincts of the Shrine of the Báb, all our fatigue has vanished. This is what you should have said. You did not come here to see me. You have come here to visit the Shrines. The friends should not fix their gaze on individuals.

To ‘Alí Nakhjávání that was the essence of the Guardian’s evanescence, his humility.

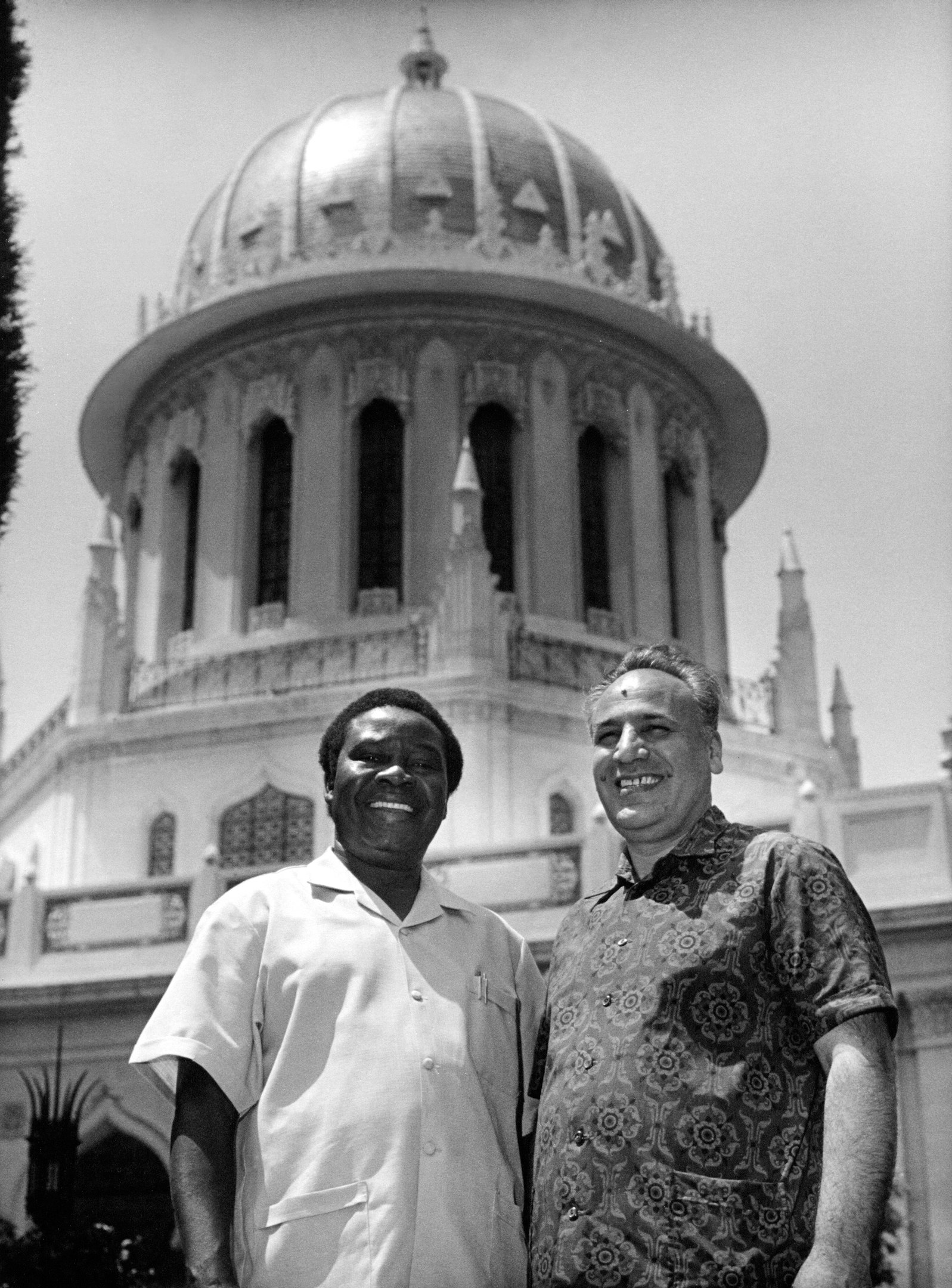

Hands of the Cause Enoch Olinga (left) and Raḥmatu'lláh Muhájir (right) in front of the Shrine of the Báb in 1973. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

Enoch Olinga had become a Knight of Bahá'u'lláh for British Cameroon, and five of the young men he had taught the Faith to had gone on to become Knights of Bahá'u'lláh in five West African countries and territories. Enoch had a burning desire to meet the Guardian and left for his pilgrimage, traveling through Tunis, and arrived in Rome on 1 February 1957, where he urgently sought the help of Ugo Giachery.

Enoch Olinga needed Ugo Giachery to perform a miracle: he had an old English passport that had expired a few years back, and didn’t have any money to travel. Ugo Giachery took Enoch to the British Consulate, where the wax-mustachioed Consul repeated to them for 20 minutes that Enoch would not be able to renew his passport. Enoch Olinga was doing what Ugo Giachery had told him to do: saying nothing, but reciting the Remover of Difficulties prayer, over and over again.

When Ugo Giachery told the British Consul that Enoch Olinga had been invited by the Guardian to Haifa, the Consul opened a drawer in his desk, pulled out a large binder. With blue pages, leafed through them carefully, and said:

I think I can do it.

Armed with Enoch Olinga’s new passport, they rushed to get a visa at the Israeli embassy, and on 3 February, Enoch Olinga finally arrived in Haifa, staying in the Eastern Pilgrim House, right next to the Shrine of the Báb. This meant that the Guardian considered Enoch Olinga an eastern pilgrim, with the privilege to walk the gardens with the Guardian and visiting the Shrines with him, hearing him chant the Tablets of Visitation with his wonderfully melodious voice. During his pilgrimage, Enoch Olinga had the bounty of spending a lot of time alone with the Guardian, and he would later remember how Shoghi Effendi “walked like a king,” and told his children the guardian was like a lion but at the same time very gentle.

Enoch Olinga was not only the first African Bahá'í to come on pilgrimage and meet Shoghi Effendi, he was also the first indigenous African Knight of Bahá'u'lláh to do so. The day he left, Shoghi Effendi kissed Enoch Olinga on both cheeks, something he rarely did.

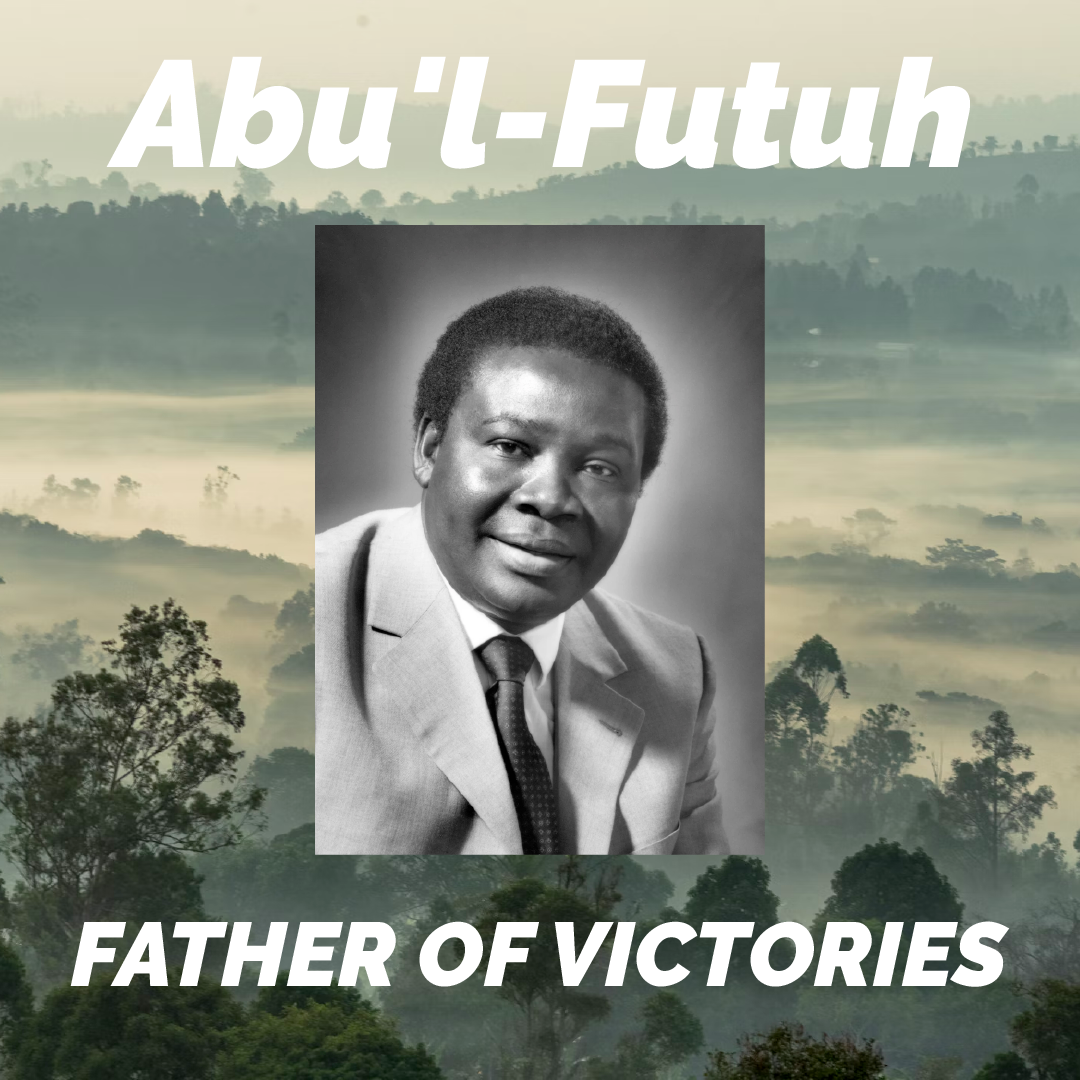

“Father of Victories” Portrait of Enoch Olinga from Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023. Cameroon was where Enoch Olinga won his greatest victories in the field of teaching during the Ten Year Crusade. Background image of a misty Cameroonian forest in Bawang, near Bansoa by Edouard TAMBA on Unsplash.

On 15 February 1957, two days after Enoch Olinga had left, the Guardian’s secretary wrote a letter on his behalf to Músá Banání, in which he expressed his pleasure with Enoch Olinga’s visit and the pilgrimage of the first African Bahá'í and Knight of Bahá'u'lláh to come to the Holy Land, in which the Guardian outlines Enoch Olinga’s extraordinary achievements and victories for the Faith and in which he conferred on Olinga his title of Abu’l-Futuh—Father of Victories:

Enoch Olinga has achieved many victories for the Faith; first in his work in Uganda; then by pioneering in the British Cameroons, becoming a Knight of Baha'u'llah there. Five of his spiritual children went from the Cameroons, to virgin areas of the Ten Year Crusade, thus becoming themselves, Knights of Baha'u'llah. He himself has confirmed 300 souls, with five Assemblies. The Guardian considers this unique in the history of the Crusade, in both the East and West; and he has blessed the one who so selflessly served, and won these victories for the Cause of God, by naming him “Abu'l-Futuh,” the “Father of Victories.” The Guardian felt you and ‘‘Alí [‘Alí Nakhjávání] would be pleased to know this, as he was ‘‘Alí spiritual child."

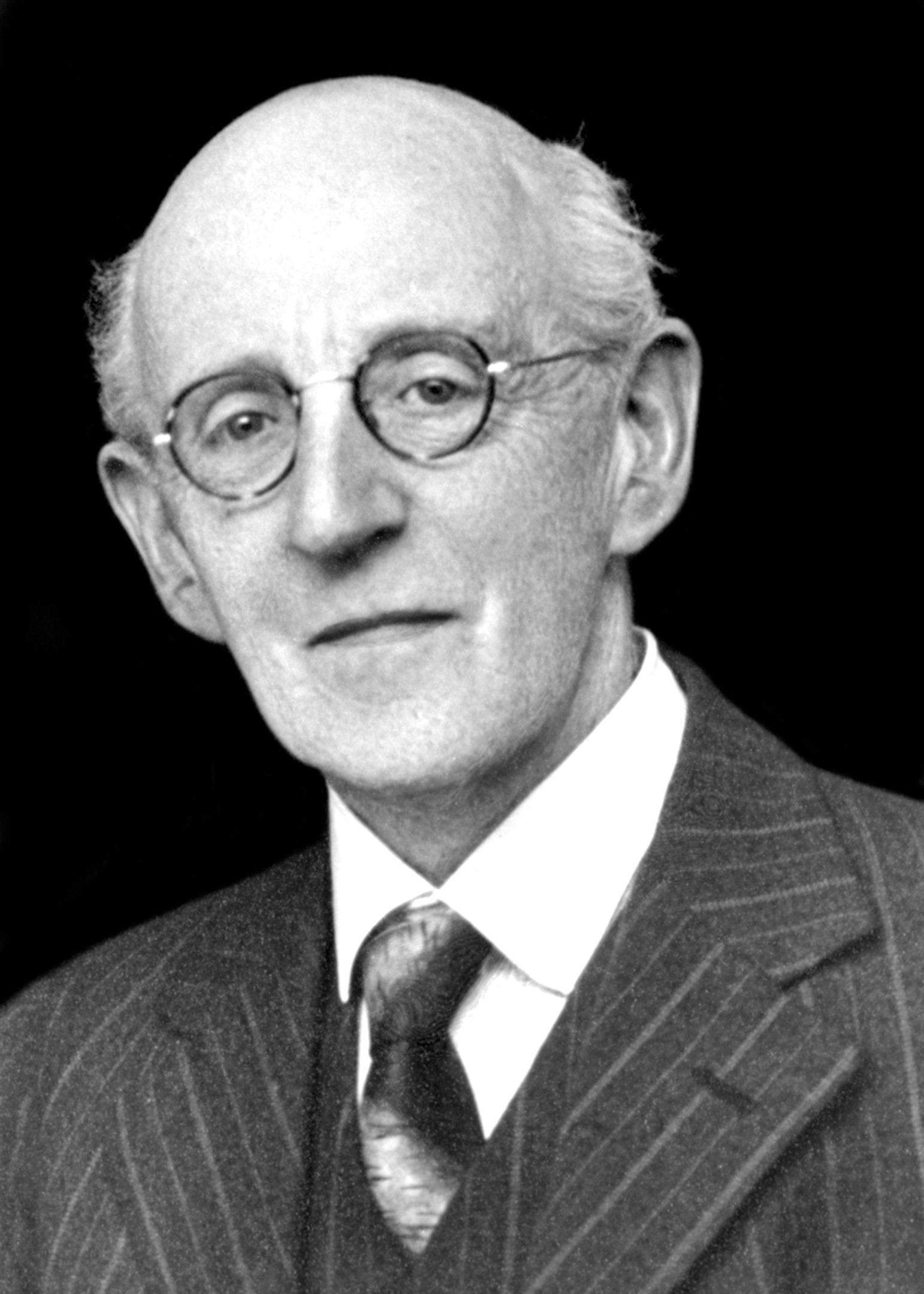

George Townshend (1876-1957). Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

George Townshend was born in Dublin on 14 June 1876. During his university studies, he excelled at two things: running and literature. In 1903, George became a barrister, but the next year, in 1904, his restlessness took him to the Provo, Utah in the United States and its rugged Rocky Mountains, where heh became a Mormon Missionary. In 1912 he was appointed Assistant-Professor of English at the University of the South in Sewanee, Tennessee. He returned to Ireland in 1916.

As soon as he arrived in England in July 1916, George received a letter from an American friend enclosing a couple of pamphlets with 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s words. As George said:

When I looked at those, that was the beginning and the end with me.

George Townshend wrote to 'Abdu'l-Bahá and received a luminous Tablet in return, which reads in part:

Thy letter was received and the account of thy life has been known. Praise be to God that thou hast ever, like unto the nightingale, sought the divine rose garden and like unto the verdure of the meadow yearned for the outpourings of the cloud of guidance. That is why thou hast been transferred from one condition to another until ultimately thou hast attained unto the fountain of Truth, hast illuminated thy sight, hast revived and animated thy heart, hast chanted verses of guidance and hast turned thy face toward the enkindled fire on the Mount of Sinai.

After he became a Bahá'í, George Townshend married Nancy in 1918. The couple had a son, Brian and a daughter, Una. In 1919, George Townshend became Rector of Ahascragh in County Galway. George Townshend became one of 8 Canons of St. Patrick’s Cathedral. His books on the Faith, The Heart of the Gospel and The Promise of All Ages increased tensions between him and the clergy and Shoghi Effendi advised him to resign.

Shoghi Effendi thought of George Townshend as "the best writer we have…the pre-eminent Bahá’í writer.” In this capacity, between 1927 and 1941, George Townshend assisted Shoghi Effendi with the translations of the Hidden Words, Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá'u'lláh, Prayers and Meditations by Bahá'u'lláh, the Kitáb-i-Íqán, and Epistle to the Son of the Wolf, and The Dawn-Breakers. He also provided literary help for God Passes By. It was George Townshend who gave The Dawn-Breakers and God Passes By their titles.

In 1933, he became Archdeacon of Clonfert, and 14 years later, in 1947, at the age of 70, George Townshend renounced his Anglican orders and wrote a pamphlet for Christians titled The Old Churches and the New World, which he sent to 100,000 people.

George Townshend was a gifted writer, and his crowning literary achievement was no doubt his book Christ and Bahá'u'lláh, which he completed shortly before his passing. Below is a list of his literary works:

- 1934: The Promise of All Ages

- 1939: The Heart of the Gospel

- 1952: The Mission of Bahá’u’lláh

- 1957: Christ and Bahá’u’lláh

The Guardian appointed George Townshend a Hand of the Cause on 24 December 1951.

George Townshend passed away from Parkinson's disease in 1957, at the age of 81 on 25 March 1957, six months before the beloved Guardian.

In his eulogy cable two days after George Townshend’s passing on 27 March 1957, the Guardian called him a “fearless defender of the Faith”:

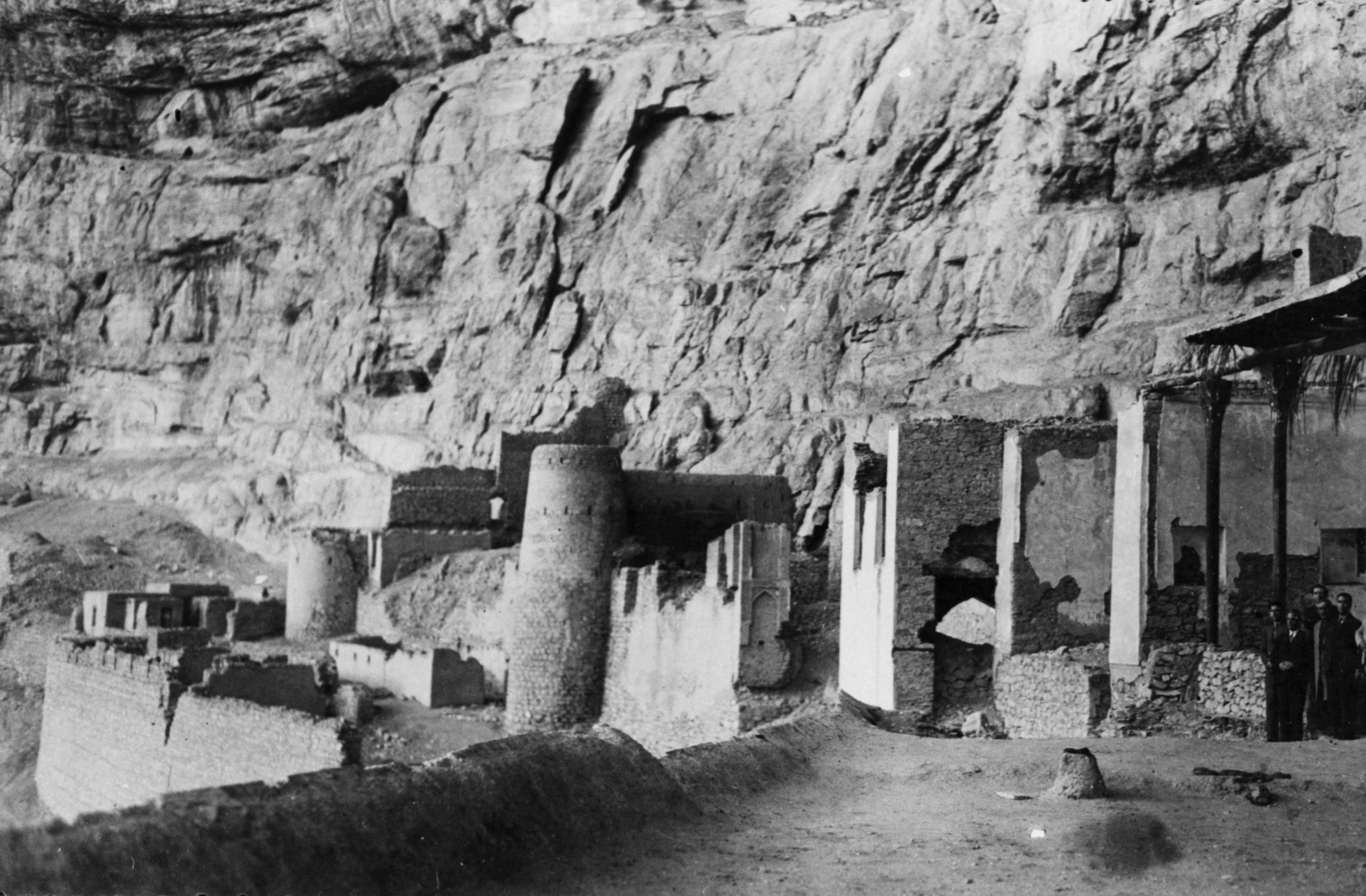

Inform Hands and national assemblies of the Bahá’í world, of the passing into Abhá Kingdom of Hand of Cause George Townshend, indefatigable, highly talented, fearless defender of the Faith of Bahá’u’lláh.