Written and illustrated by Violetta Zein

This part covers the life of Shoghi Effendi from the age of 46 in 1943 to the age of 56 in 1953.

As we begin the chronological story of the Guardian’s crowning achievements—the building of the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb—a formal introduction is required to a herculean feat of modern-day Bahá'í historical research from which several of these stories are based.

In 2018, Bahá'í journalist, historian, and editor Michael V. Day published an extraordinary book: Coronation on Carmel: The Story of the Shrine of the Báb Volume II: 1922 – 1963.

Coronation on Carmel is the biography of the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb in 364 glorious pages and is a thrilling read on the crowning achievement of the Guardian’s ministry.

The stories in this chronology on the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb are greatly summarized. To experience the entire adventure of this four-decade long journey, please read Coronation on Carmel and discover the hundreds of stories that Michael Day hash uncovered in his exacting research.

Michael V. Day is the author of an entire trilogy on the Shrine of the Báb, all published by George Ronald:

Journey to a Mountain - The Story of the Shrine of the Bab Vol. I: 1850-1921 tells the story of the highly secret process of carrying the casket containing the precious remains of the Báb across mountains, desert and sea to the Holy Land, and how 'Abdu'l-Bahá built the original Shrine of the Báb out of local Palestinian stone on the spot indicated to him by Bahá'u'lláh in 1891 , completing it in 1909, and laying the remains of the Báb to rest on 21 March 1909.

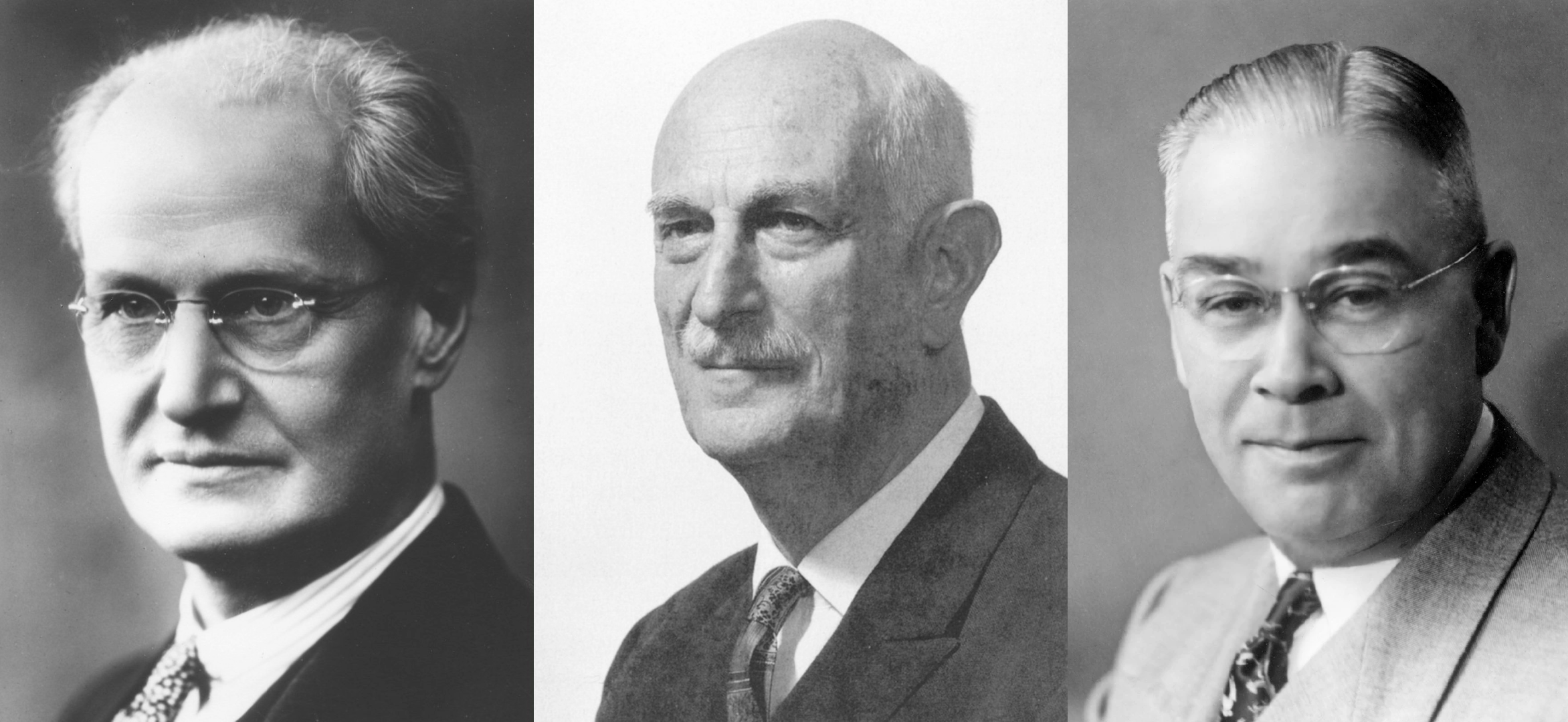

Coronation on Carmel: The Story of the Shrine of the Báb Volume II: 1922 – 1963 picks up the story of the Shrine of the Báb during the ministry of the Guardian and tells the story of the erection of the superstructure of the Shrine, a story of collaboration between Shoghi Effendi, William Sutherland Maxwell Ugo Giachery, Leroy Ioas, and all of the architects, gilders, builders, and collaborators in Italy, Israel, and the Netherlands who made it happen, , the story told here in greatly summarized form.

Sacred Stairway - The Story of the Shrine of the Bab Volume III: 1963–2001 continues the thrilling biograph of the Shrine of the Báb during the ministry of the Universal House of Justice, with the story of the successful construction in the 1990s of a stairway with 19 garden terraces stretching one kilometre up the steep northern slopes of Mount Carmel. The story of the project of the Universal House of Justice to build the “Pathway of the Kings and Rulers of the world” is one of devotion, sacrifice and supreme expertise in architecture, engineering and horticulture.

Michael Day is also the author of Queen of Carmel: The Shrine of the Báb 1850 - 2011 A story in photographs, an illustrated guide to events that led to today's spectacular vision of the Shrine of the Báb and its garden terraces on Mount Carmel in Haifa, Israel.

The stone edifice, the original Shrine of the Báb while it was being built by 'Abdu'l-Bahá in the early 1900s. Source: Bahá'í World News Service.

Ugo Giachery called the project of the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb, an “integral part of Shoghi Effendi’s universal conception of the expansion of the Faith and of the consolidation of its institutions at its World Centre.” Shoghi Effendi considered the Shrine of the Báb an Institution, and in completing its superstructure, he was literally and practically making preparations for the realization of the prophecy of Bahá'u'lláh regarding the election of the Universal House of Justice, that the “Ark” Bahá'u'lláh spoke of in the Tablet of Carmel, would soon sail on the slopes of God’s Own Mountain and manifest the Universal House of Justice.

One day, in 1942, Shoghi Effendi was returning from Mount Carmel and he asked Rúḥíyyih Khánum about ideal dimensions for a staircase. Rúḥíyyih Khánum asked the Guardian why, he didn’t ask one of Canada’s best architects—William Sutherland Maxwell—who was living across the street in the western Pilgrim House. As Rúḥíyyih Khánum puts it so well, “this marked the beginning of a beautiful partnership. I have never known two people who had such a perfect sense of proportion as Shoghi Effendi and my father and of the two the Guardian's was the finer.”

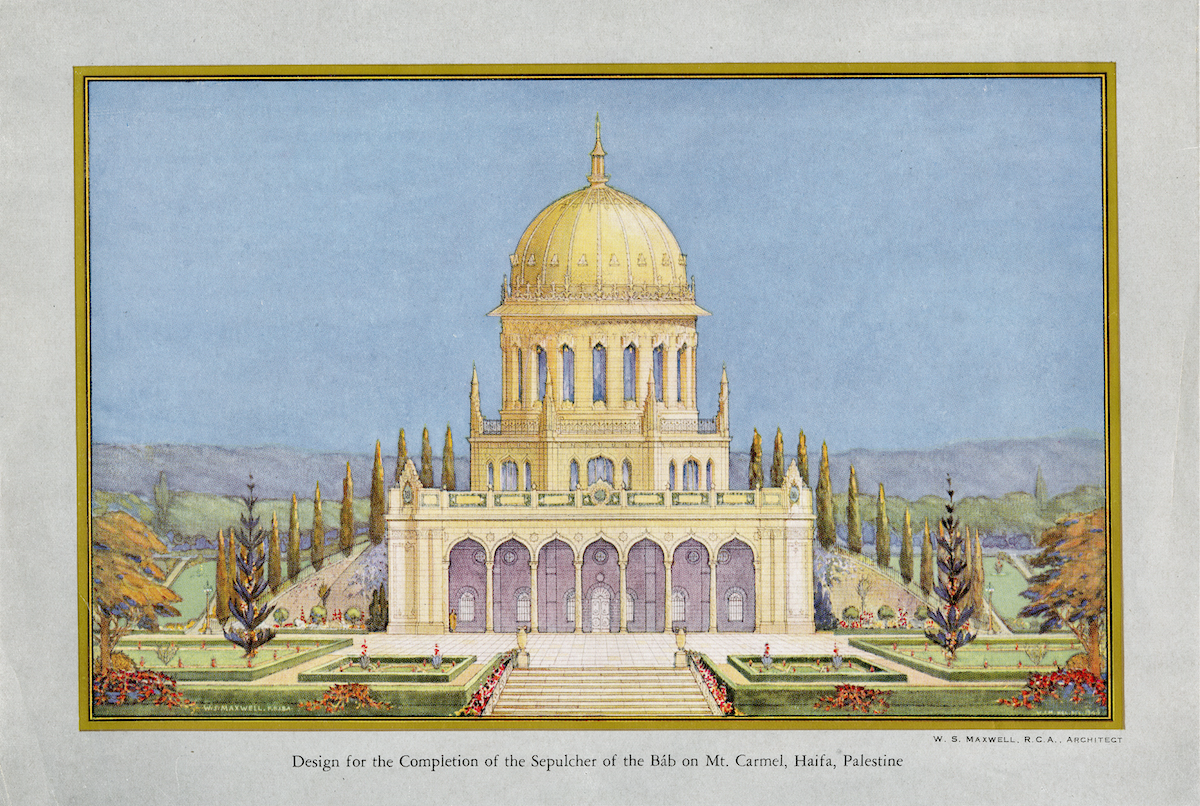

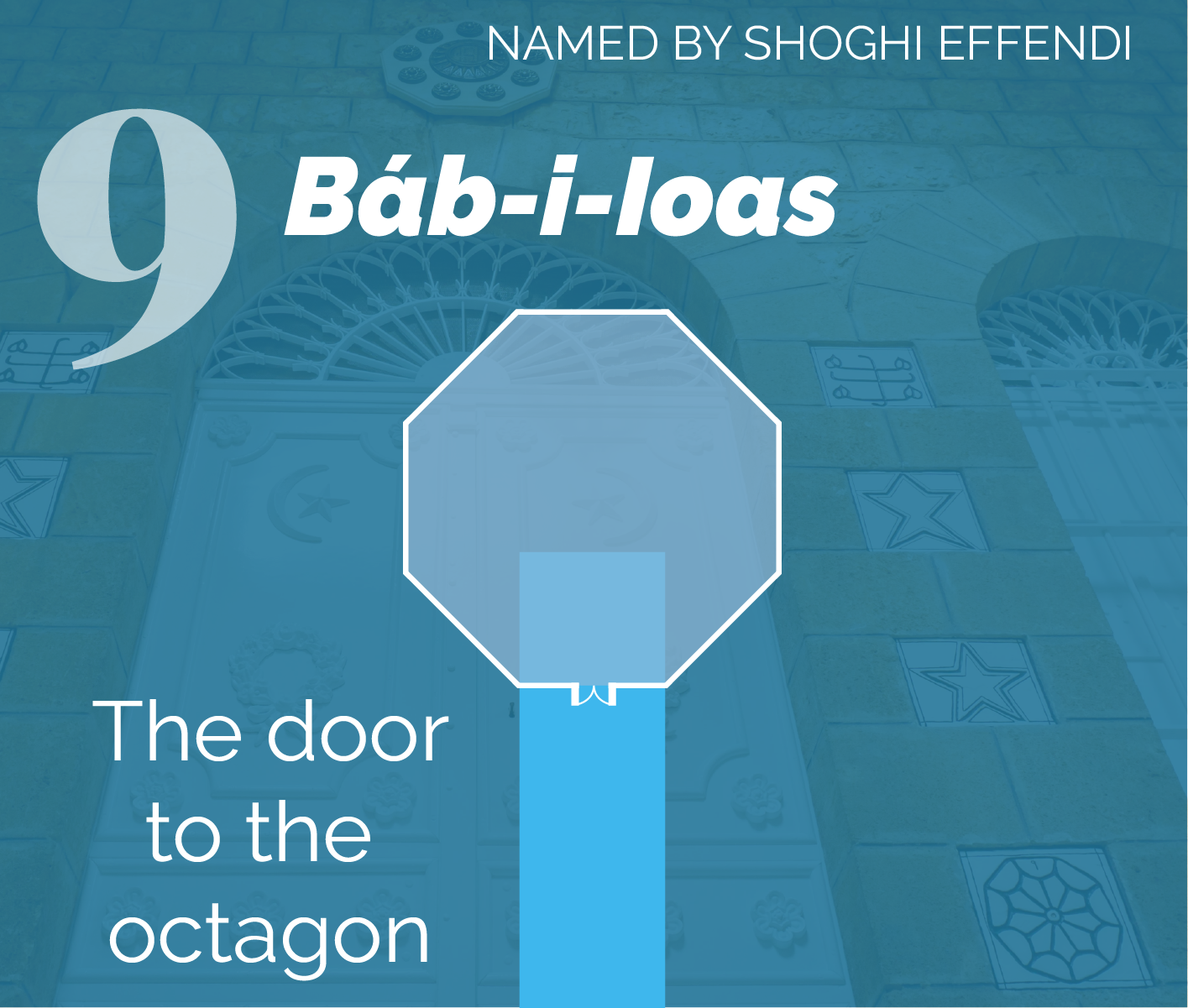

'Abdu'l-Bahá had once stated that the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb should have a dome and an arcade. Beginning in late 1942, the Guardian tasked William Sutherland Maxwell to come up with a design, neither completely eastern or western, that followed 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s guidance while enhancing and elevating and not obscuring the original Shrine the Master had completed in 1909. The Guardian also suggested that the dome should sit on an octagon.

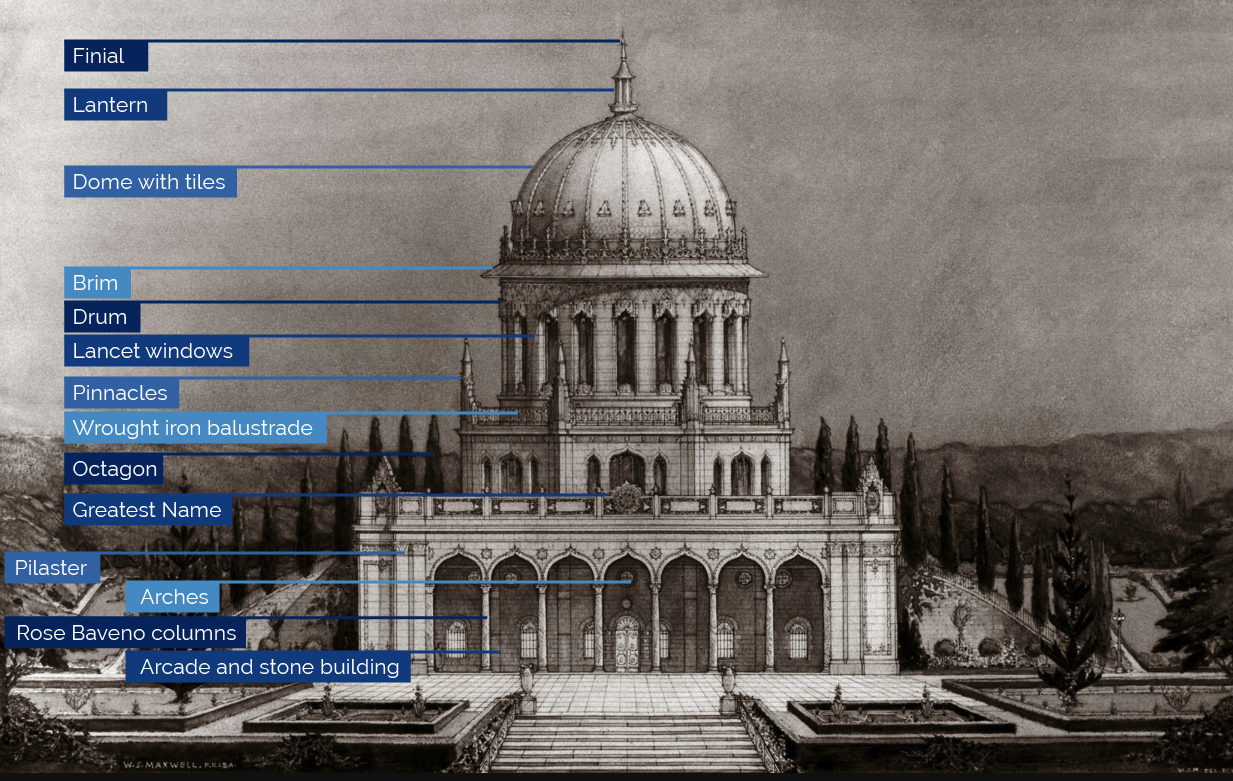

William Sutherland Maxwell’s exquisite watercolor architectural drawing for the Shrine of the Báb on the frontispiece of The Bahá'í World Volume 9. This pristine image was provided © United States National Bahá'í Archives, used with permission.

The first design William Sutherland Maxwell produced had an arcade, an octagon but the dome was a pyramid. Shoghi Effendi suggested the dome should resemble Michelangelo’s design for St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome.

When he came back with another design which was too European, Shoghi Effendi liked the proportions and asked William Sutherland Maxwell to keep them and make another design. Then, Shoghi Effendi asked William Sutherland Maxwell to change the height of the octagon.

This process went on for several weeks, Shoghi Effendi making small changes in each version, while keeping elements he had already approved. Sometimes the changes were in the height of certain features or the thickness of other elements, and William Sutherland Maxwell drew design after design, and version after version, always following the Guardian’s perfect instinct and sense of proportion, gradually bringing to life the design that was in the Guardian’s mind.

Finally, on 25 December 1943, the Guardian approved William Sutherland Maxwell’s design. The survey plan of the Shrine of the Báb was finished two days later, on 27 December 1943.

After the final design was approved, William Sutherland Maxwell painted a gorgeous color painting of the Shrine of the Báb, exactly as we know it now, with its golden dome, its colonnade, its windowed octagon, under a beautiful golden afternoon light.

Although Shoghi Effendi had begun the design process with only the scantest information from 'Abdu'l-Bahá—that there needed to be an arcade and a dome—he had let his phenomenal intuition guide him through version after version of William Sutherland Maxwell’s drawings, changing one small detail every time while keeping an additional detail out of each successive drawing.

Exactly ten years later—when the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb had finally been completed—Shoghi Effendi came to dinner one night beaming with happiness. Something extraordinary and completely unexpected had just happened, which the Guardian explained:

Last month I received a letter from [Badí Bushruí], one of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s secretaries. He said he had found among his papers a diary kept during the days when he served ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. He wrote to ask if I’d like to read the diary and I said, of course I want to read it. He sent it to me, and what do you think I found today? I found a talk that ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had given, recorded in this diary, in which ‘Abdu’l-Bahá explained how the Shrine should be embellished and beautified. And there it is on Mt. Carmel, just as the Master had described it.

The Guardian had followed his intuition with absolute certitude, and he had built the Shrine of the Báb “Just as the Master had described it.”

The Guardian asked William Sutherland Maxwell to build him a scale model showing the. Future superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb. This is a photograph of that model. Source: The Bahá'í World Volume 10, page 3.

There seem to have been three main ways—at least—in which the Guardian and William Sutherland Maxwell worked together.

The first method was consultation, where they would both discuss a design. In this type of collaboration, William Sutherland Maxwell finished a version of the design for the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb, having incorporated the Guardian’s last round of suggestions and modifications, he would bring it to Shoghi Effendi and they would talk back and forth. Once, because of his exhaustion, the Guardian was propped up in bed, sitting and working—not resting, of course. Shoghi Effendi invited William Sutherland Maxwell to pull up a chair next to his bed so they could look at the new design together.

Another way they worked together, was live editing, in a way, a well-oiled system between the designer—the Guardian—and the architect—William Sutherland Maxwell. First, the Guardian would describe to Sutherland what he wanted. Then, Sutherland went to his office and made a scaled drawing of what Shoghi Effendi had described, then bring the drawing back to him. The Guardian would pick up a pencil, and with a couple of deft, graceful strokes, make a change here or there, to reflect more accurately the design that was in his mind, and Sutherland would return—literally—to the drawing board. But there were times when William Sutherland Maxwell’s designs were so exquisite, there was nothing for the Guardian to add. Our next story is one such case.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum describes a third process—and there were no doubt many, many more given the Guardian’s brilliant mind—was, shall we say, 3D. This is how it worked: the Guardian would ask Sutherland to make him a model of the final concept so that he could visualize it perfectly.

The alchemy between the Guardian and William Sutherland Maxwell was so perfect that. Rúḥíyyih Khánum described their working together like a knife: Sutherland was the handle perfectly fitted into the palm of the Guardian—allowing him to bring his design to life—and Shoghi Effendi was the sharp blade—supremely confident, infallible, clear in his vision.

Six years later, when Shoghi Effendi was working on building the colonnade over the original Shrine of the Báb, he sent designs to William Sutherland Maxwell for his opinion. When William Sutherland Maxwell responded that he was satisfied, Shoghi Effendi told Rúḥíyyih Khánum:

One word from your father I attach more importance to than any amount of praise by the engineers.

Photograph of the Shrine of the Báb from Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

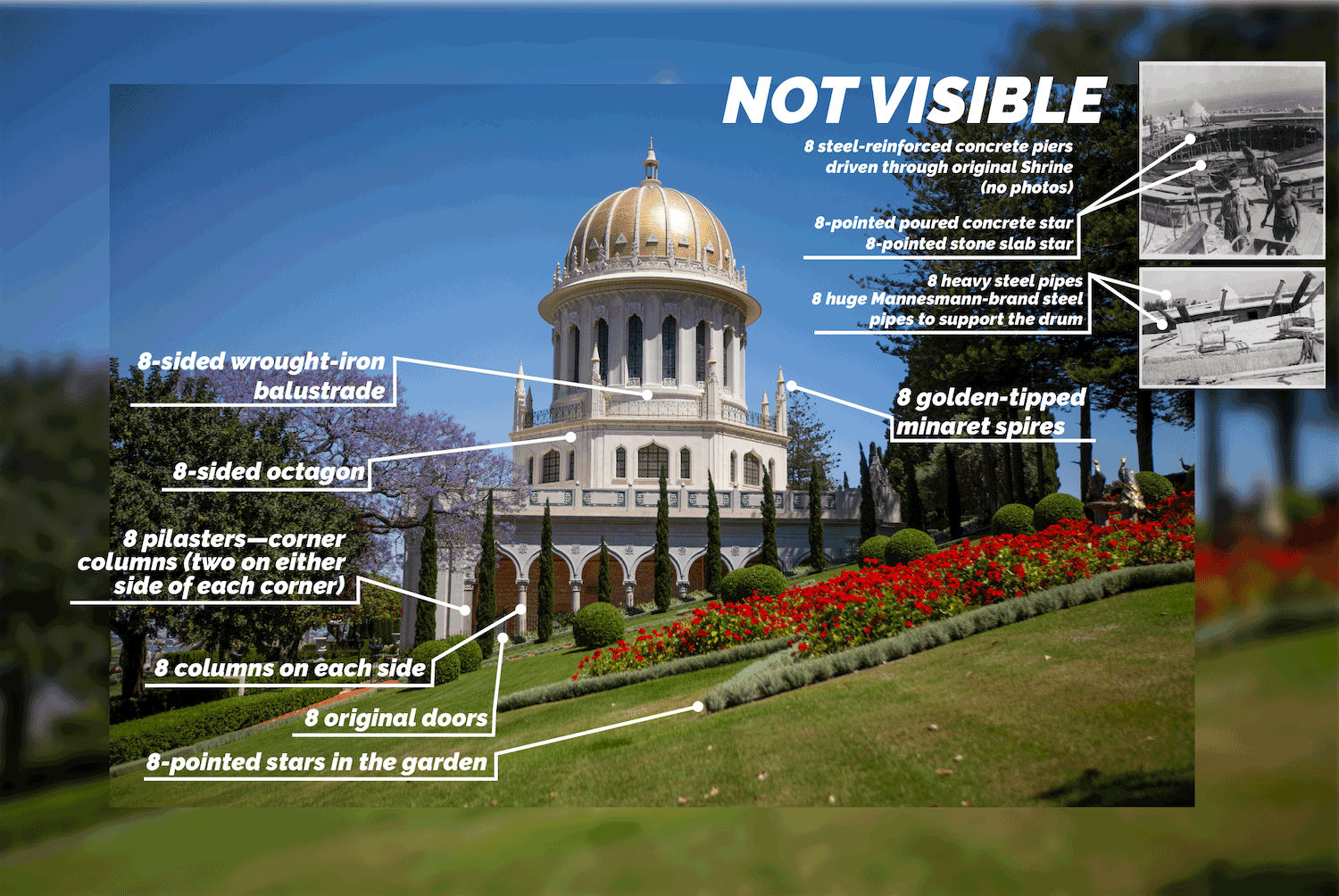

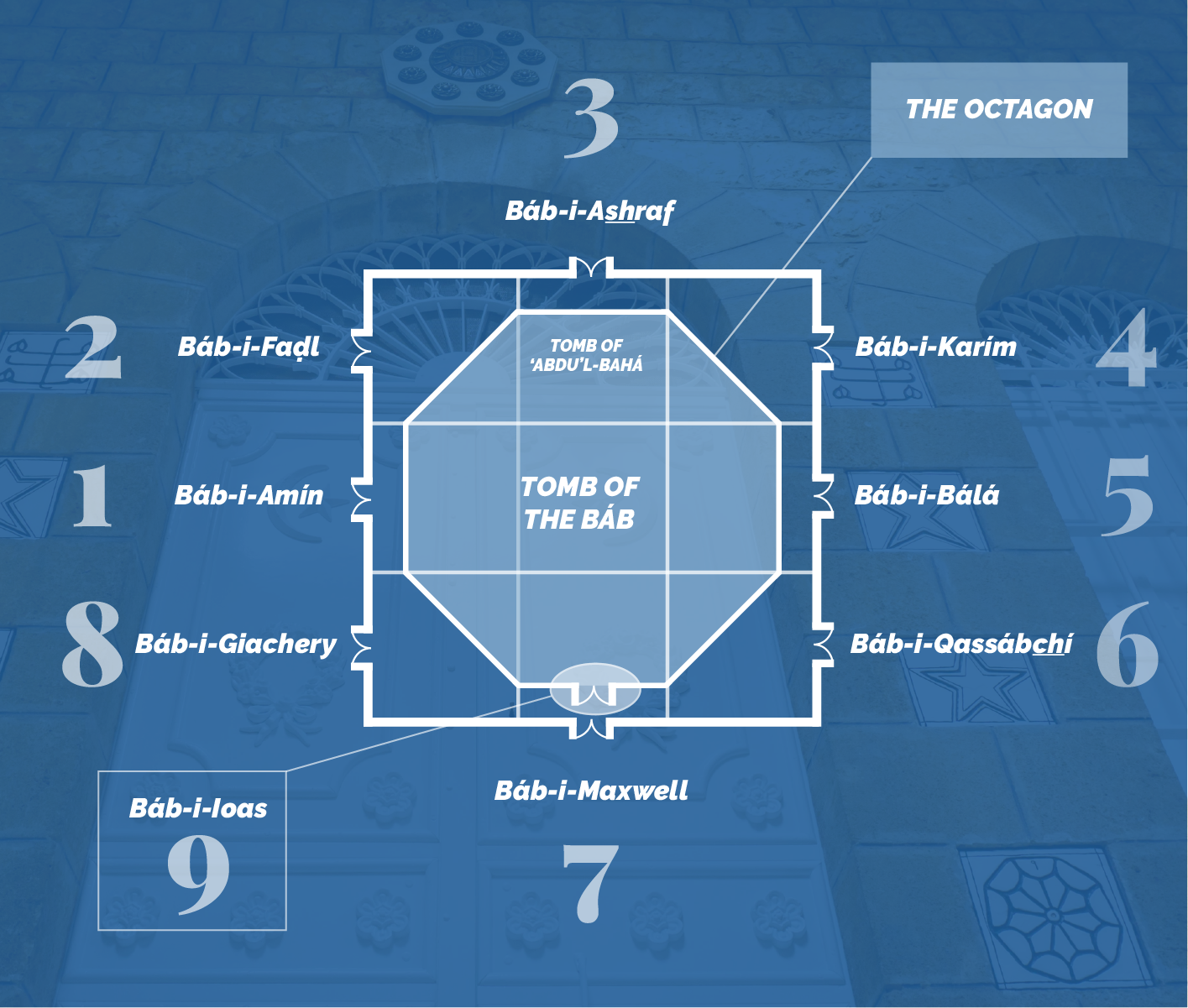

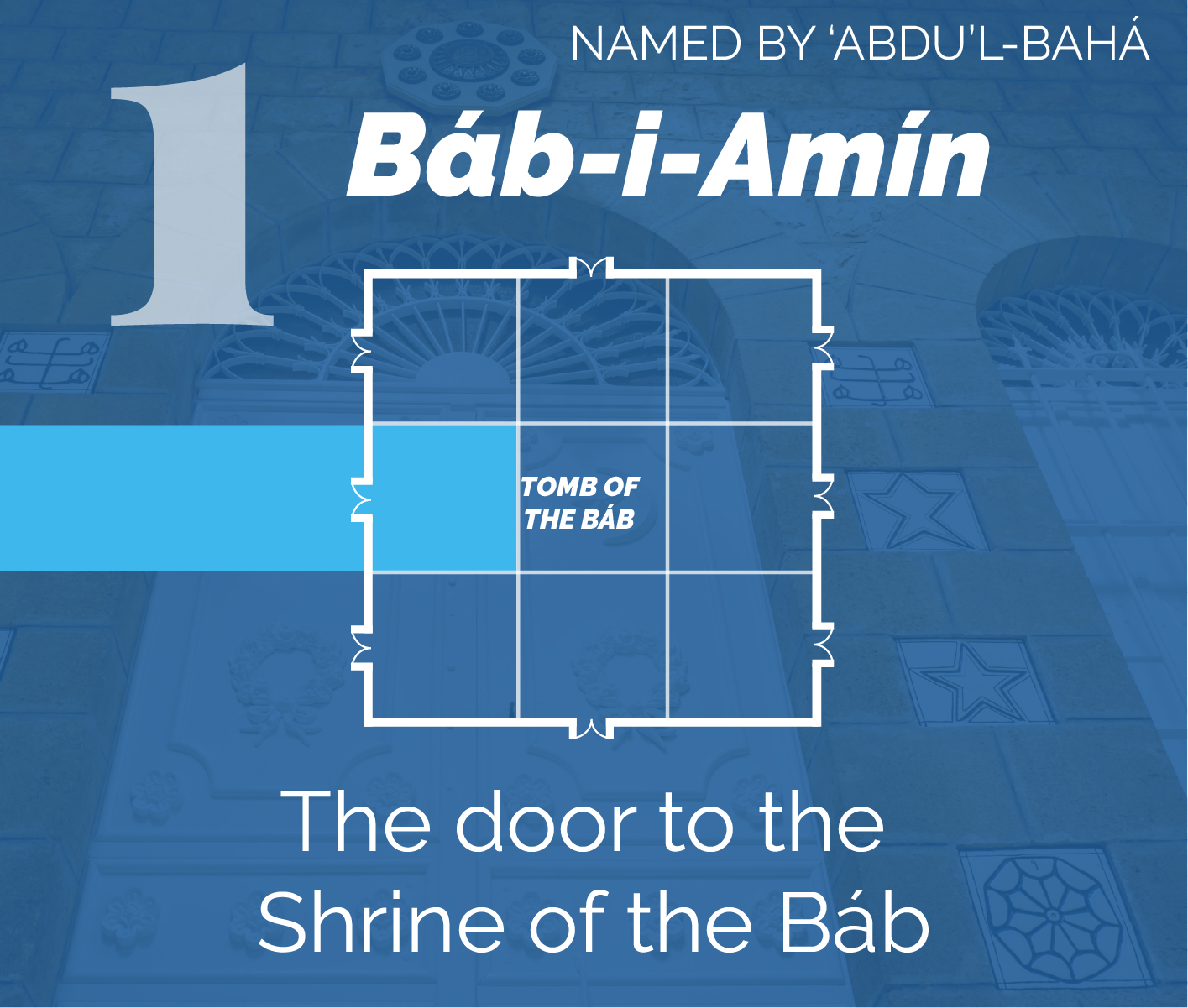

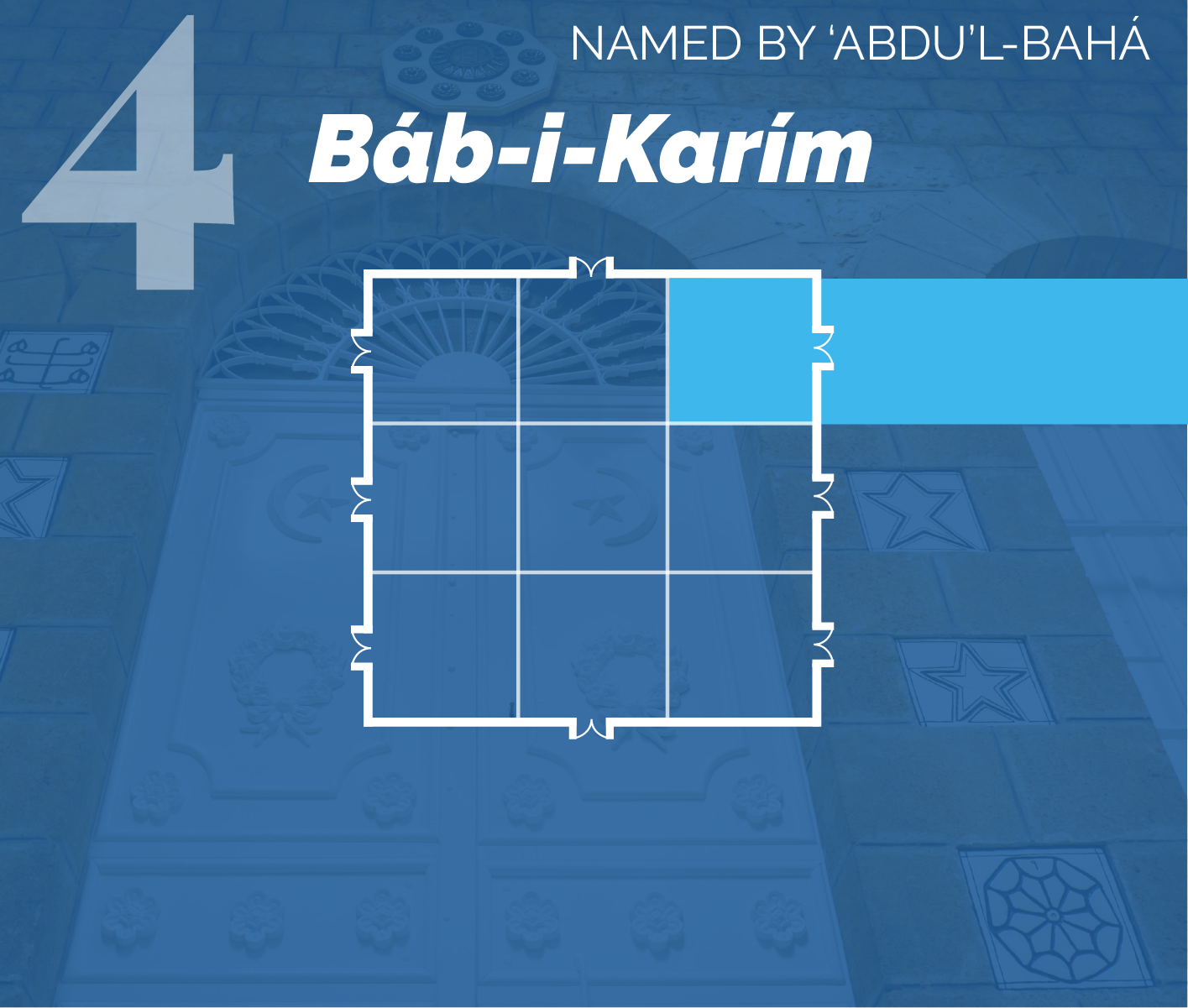

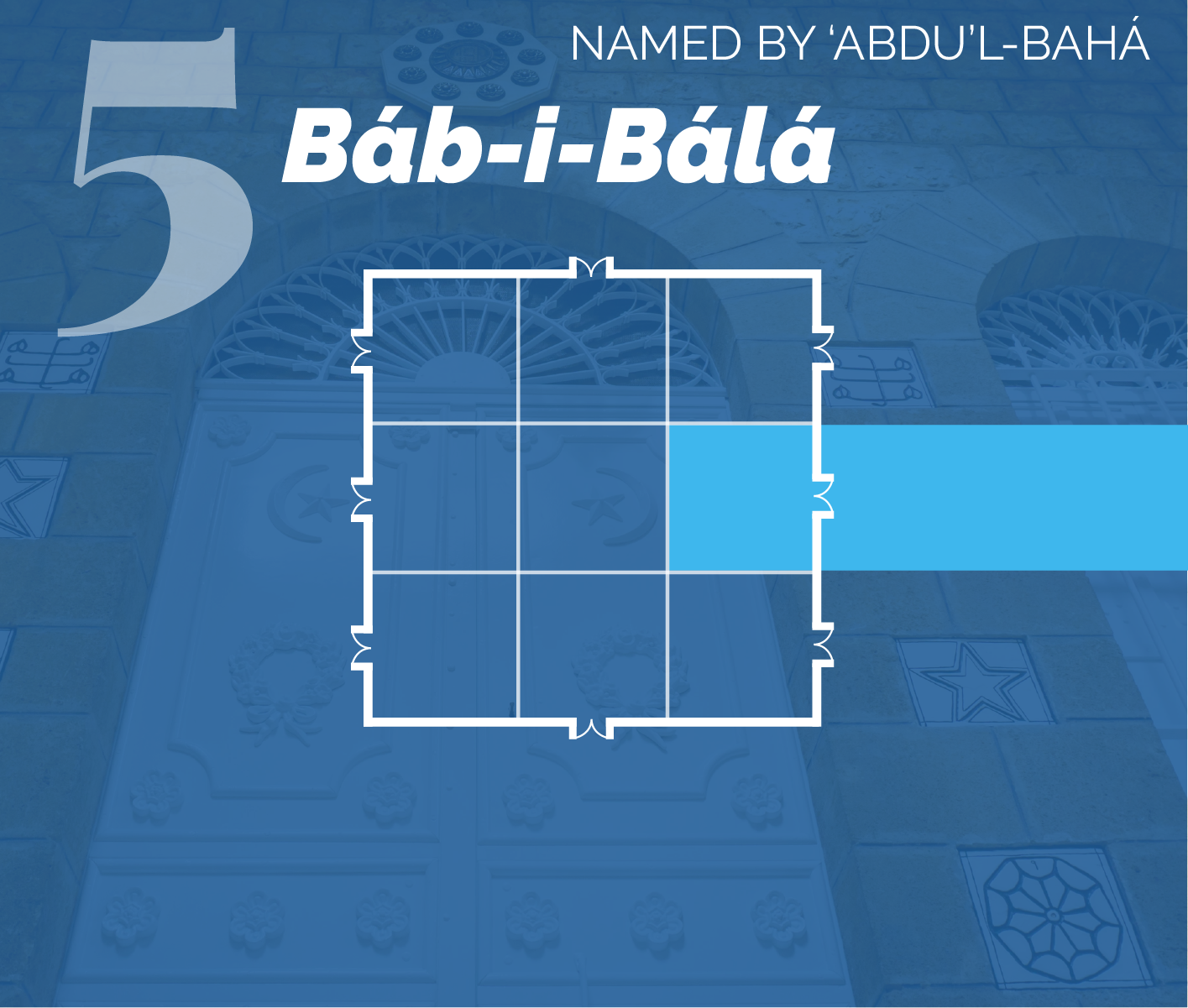

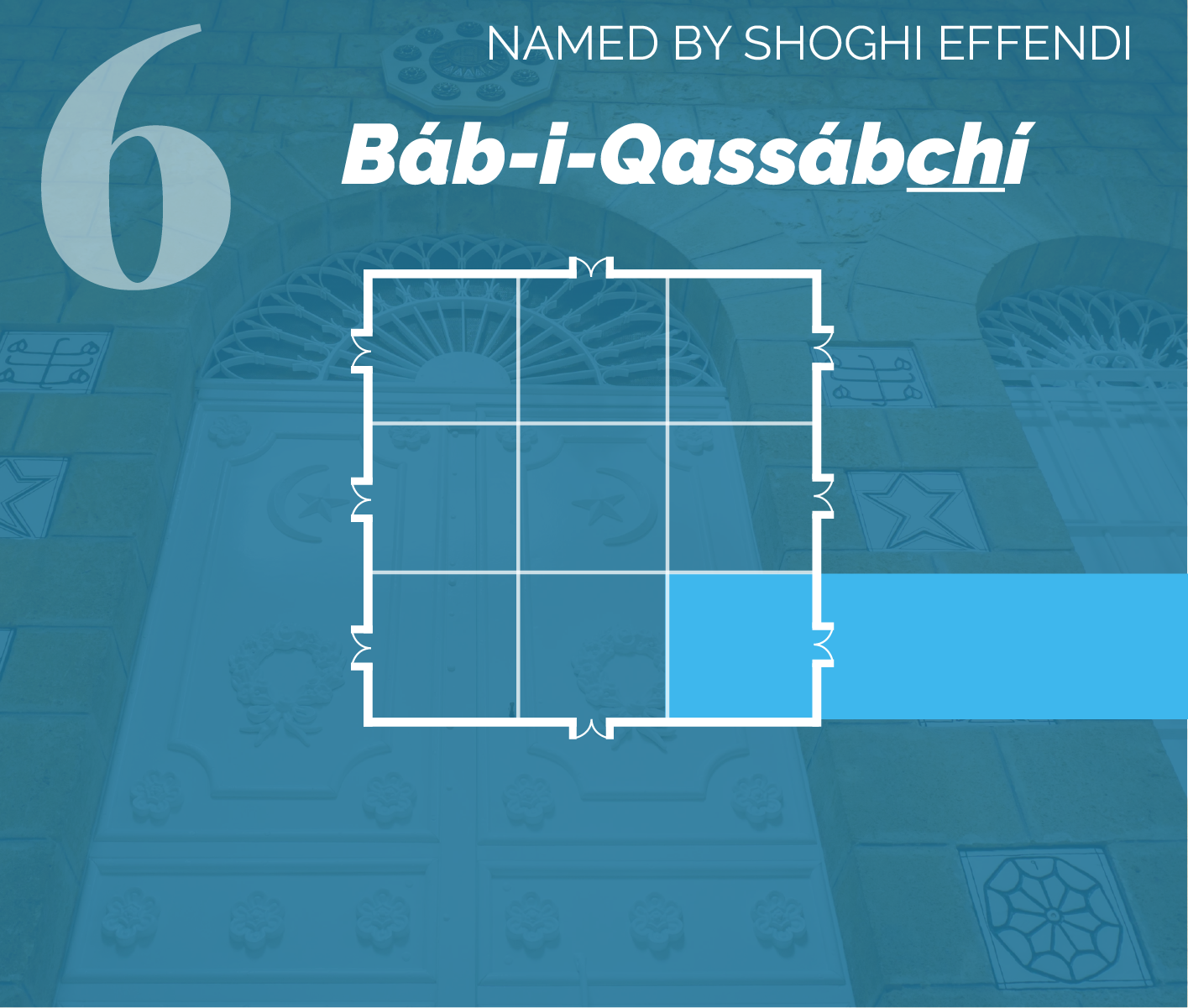

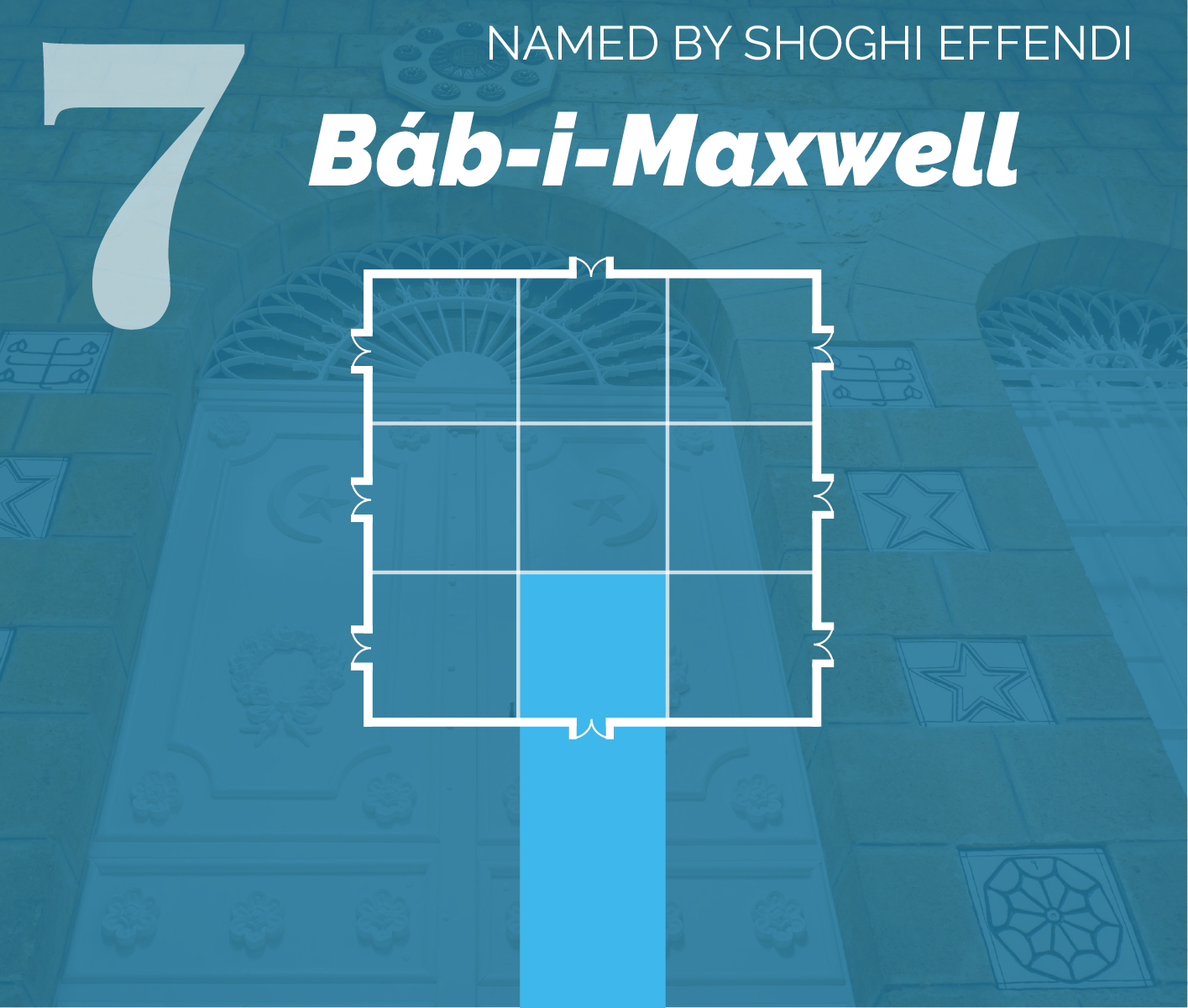

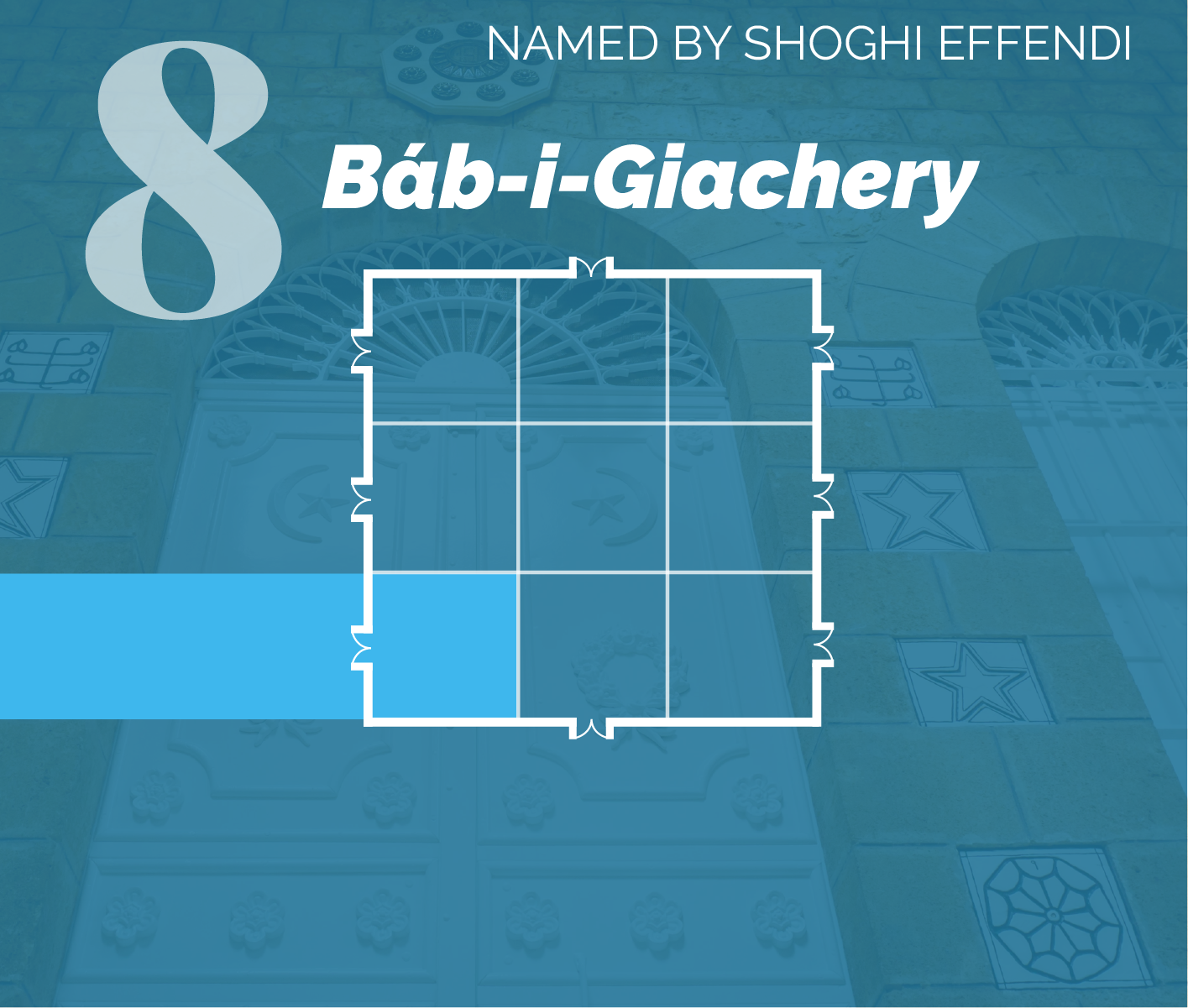

The number 8, as per the Guardian’s wishes is present in many elements of the final superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb and its gardens:

- 8 doors originally planned by 'Abdu'l-Bahá for the original Shrine ; the Master was only able to complete 5 and Shoghi Effendi built the remaining 3 in 1929, after he had added the remining three rooms to the Shrine

- 8 sides to the octagon, and, related to the octagon:

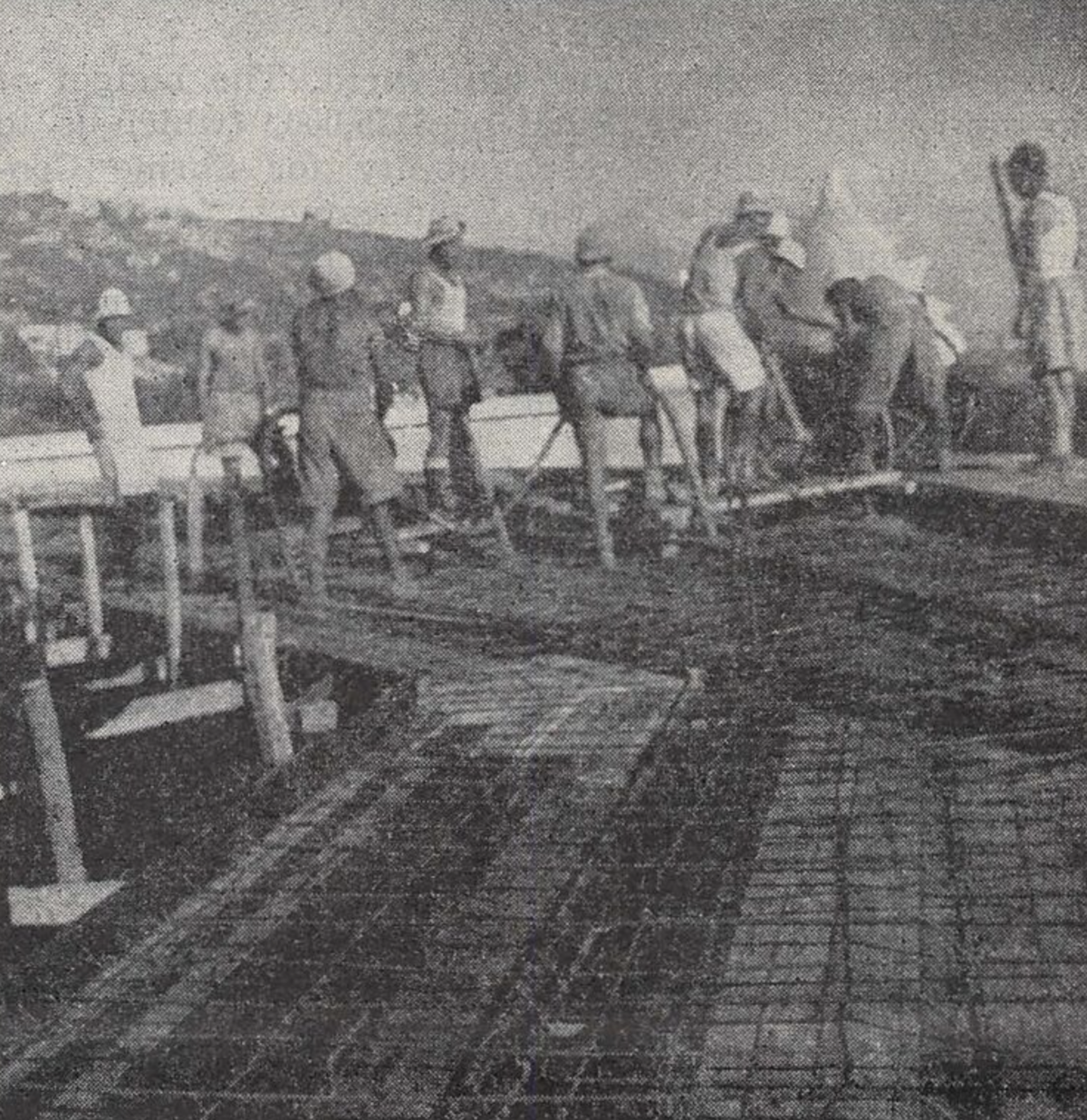

- 8-pointed hollow star that forms the elevated platform foundation for the octagon, the brim and the dome

- 8-poined stone slab star

- 8-pointed poured reinforced-concrete star poured in one day above the stone-slab 8-pointed star

- 8 heavy steel pipes supporting the hollow star

- 8 pillars of steel-reinforced concrete piers reaching through the original Shrine walls deep down to the bedrock of the mountain to support the entire superstructure

- 8 sections of the wrought-iron balustrade

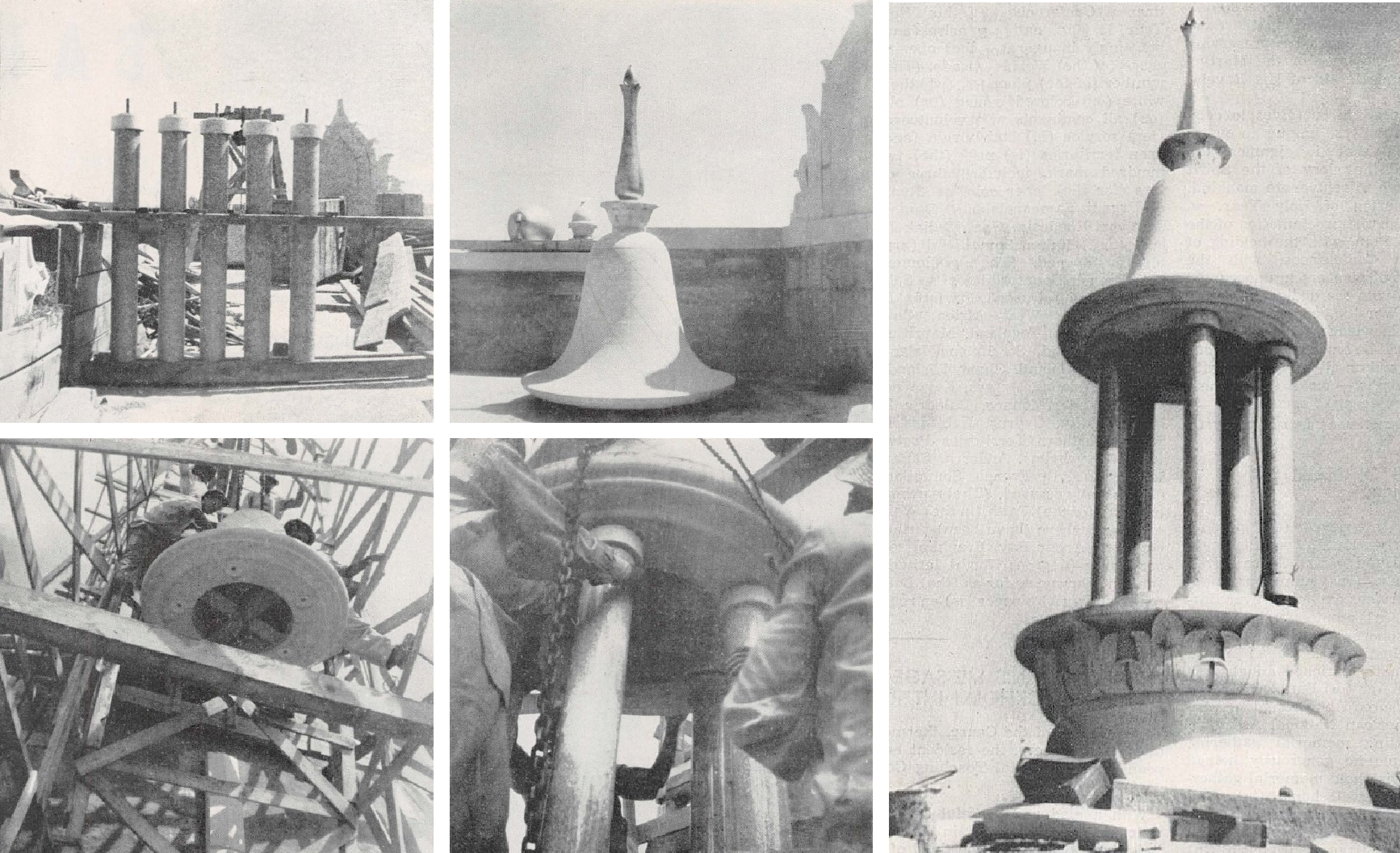

- 8 huge Mannesmann-brand steel pipes to support the circular drum of the superstructure—which supports its dome

- 8 pilasters—corner columns emerging from the colonnade: there are two on each of the four corners of the arcade

- 8 columns on each of the four sides of the building for a total of 24 columns

- 8 golden-tipped minaret spires

- 8-pointed stars in the garden, contrasting against the grass

Ugo Giachery had already noticed the predominance of the number 8 in the architectural drawings, and one evening, Shoghi Effendi explained to Ugo Giachery that he was the one who had guided William Sutherland Maxwell in making the number 8 a prominent design element, tied to the station of the Báb, who, as a Siyyid, a direct descendent of the Prophet Muḥammad deserved to be remembered in the same way as the Prophet Himself and the Holy Imáms. Speaking one evening on the importance of minarets in Islám, Shoghi Effendi told Ugo Giachery:

The mosque of Medina has seven minarets, the one of Sulṭán Aḥmad in Constantinople has six, but the Qur’án mentions eight.

Shoghi Effendi recited an Arabic verse for him from the Qur’án Verse 17 of Suráh LXIX, “The Inevitable,” which he then translated into English:

And the angels shall be on its sides, and over them on that day eight shall bear up the throne of thy Lord.

The 8 slender minaret spires with gilded points on the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb are meant to represent the bearers of the throne of God, in Islamic.

In Islám, ‘Arsh (the Throne of God) is the dwelling place of God, but also an elevated realm, located above the highest heaven and enveloping all the heavens and the earth, surrounding all systems, and created by God as a symbol and manifestation of His power and a perfect mirror of all His names and attributes, the seat of God’s unknowable essence, not accessible by mortals.

The Throne of God is also very significant in the Báb’s life, because as a child of 5, the Báb was already intimately familiar with this deeply significant and highly complex mystical concept.

The Guardian asked William Sutherland Maxwell to incorporate the spiritual meaning of this Islamic prophecy—symbolized by the number 8—in the project, to testify to the Báb’s exalted station, to eternally honor the Martyr-Prophet in His Shrine and to emphasize how closely the Báb's Revelation was connected with Islamic prophecies.

The Master had designed the inner Shrine so there could be eight doors…Also the Báb is the eighth Manifestation of those religions whose followers still exist. When Sutherland [William Sutherland Maxwell] designed the Shrine, I told him, “You must have eight columns on each side.”

The first crown: The parapet of the arcade with its arches and mosaics. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023. The second crown: The wrought iron balustrade of the octagon. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023. The third crown: The garland around the dome. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

Shoghi Effendi always referred to three crowns in the design of the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb, and they will be the main references to construction stages.

- The first crown was the parapet of the arcade—the parapet is the decorated low wall that “crowns” the 24 Rose Baveno granite columns of the arcade: it does not include the columns themselves

- The second crown was the wrought-iron balustrade and 8 pinnacles or minarets of the octagon

- The third crown is the intricate carved marble garland at the base of the dome

The sublime architectural features of the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb. Background: Drawing by William Sutherland Maxwell of the Shrine of the Bab with the superstructure he designed, 1944. Source: Bahá'í World News Service. Inspiration for graphic from Bahá'í World News Service.

Closeup of a magnificent fence. Photograph by Farzam Sabetian. Source: Luminous Spot: The Shrine of the Báb.

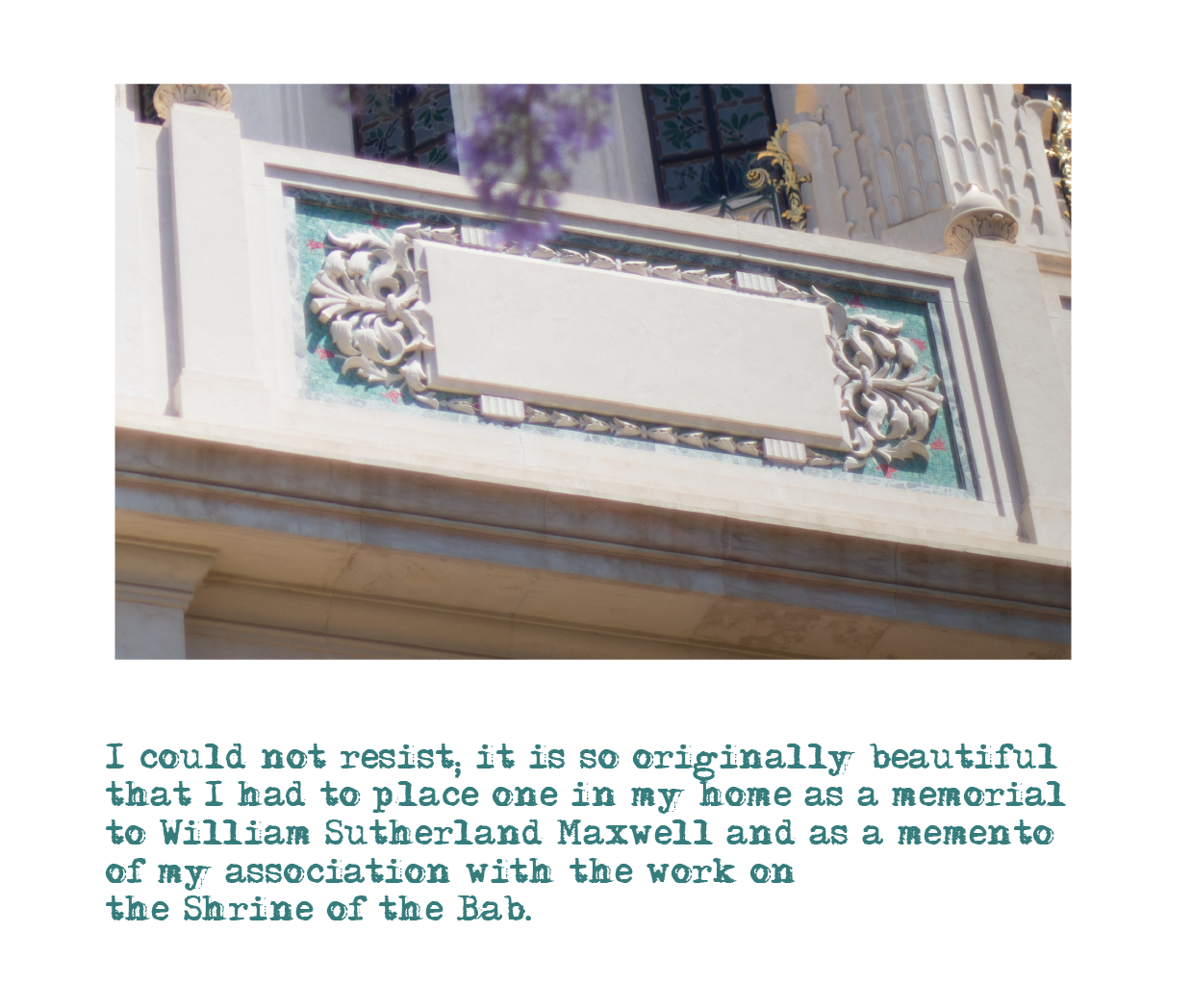

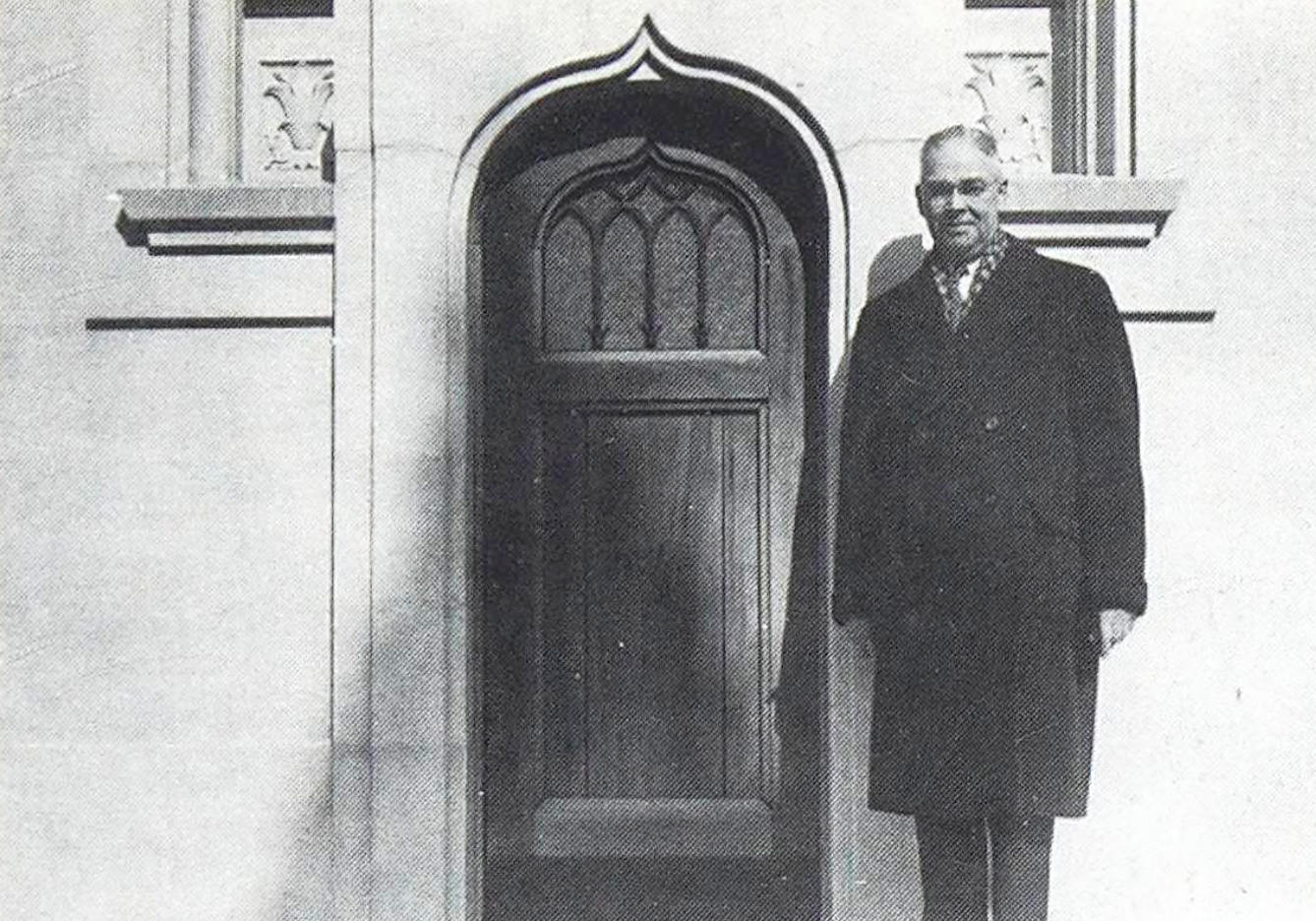

One day, Shoghi Effendi asked William Sutherland Maxwell to design the main entrance gate leading to the Shrine of the Báb. When her father had finished the drawing, Rúḥíyyih Khánum brought it to the Guardian’s office-room, where she found him in bed. She gave him the drawing, and Shoghi Effendi looked at it for some time in silence. Then, he said:

It's not fair.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum was instantly worried and misinterpreted what the Guardian had said, thinking he wasn’t satisfied, and she asked, anxiously:

Is it not what you had wanted?

It was the complete opposite.

The Guardian replied, admiringly:

Why, no one can resist anything when it looks as beautiful as this!

The Guardian was so delighted by Sutherland’s sketch that he had it framed and hung it on the wall of his office-room, where it stayed until his passing, 14 years later.

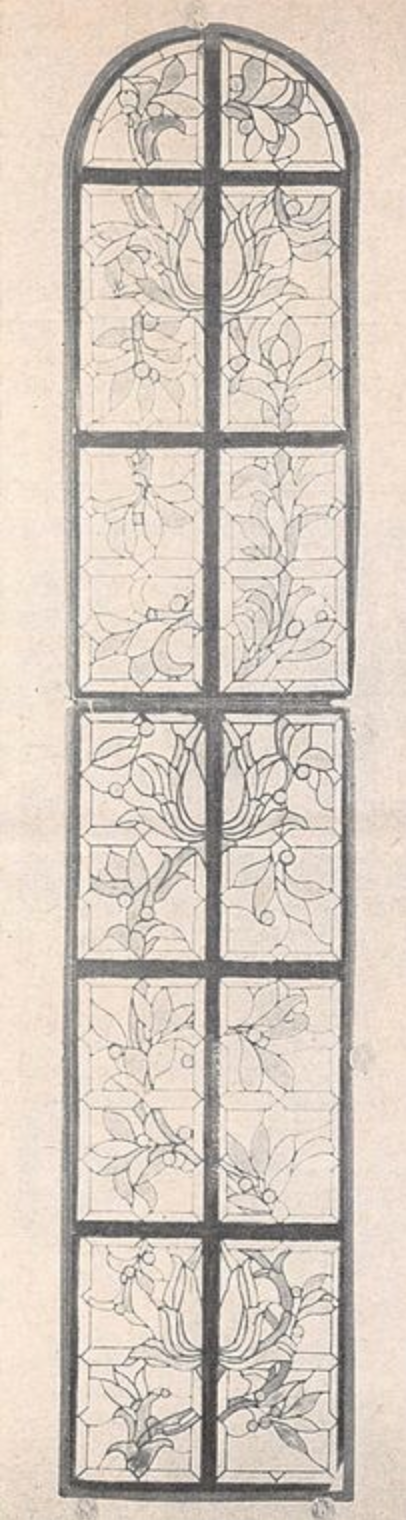

A drawing of one of William Sutherland Maxwell's details of the balustrade which would surmount the Arcade of the Shrine of the Báb on Mount Carmel. This represents the central panel facing the sea and Bahjí. The Greatest Name, in bronze gilt, will be on a star of green marble. Green Mosaic is contemplated for the background of the "B" and leafage. Source: The Bahá'í World Volume 11, page 90.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum, the deep friendship between her father and her Guardian—the two men she adored—described what it meant to her:

“[of]the many undeserved blessings in my life this was one of the greatest that God in His infinite mercy showered upon me—the great love between Shoghi Effendi and my father.”

Rúḥíyyih Khánum spoke of these blessed moments:

Such fleeting moments of peace and family pleasure in the stormy atmosphere of our lives sweetened what was often a very bitter cup of woe.

The love and collaboration between Shoghi Effendi and William Sutherland Maxwell was the greatest source of joy to Rúḥíyyih Khánum during those war years, and she would later say:

I really learned to know and appreciate my father through Shoghi Effendi.

Shoghi Effendi, Rúḥíyyih Khánum, and William Sutherland Maxwell enjoyed each other’s company, and Rúḥíyyih Khánum’s father often traveled with her and Shoghi Effendi. The first few years he was in the Holy Land, he spent a few weeks in the summer with Shoghi Effendi and his daughter in Jerusalem.

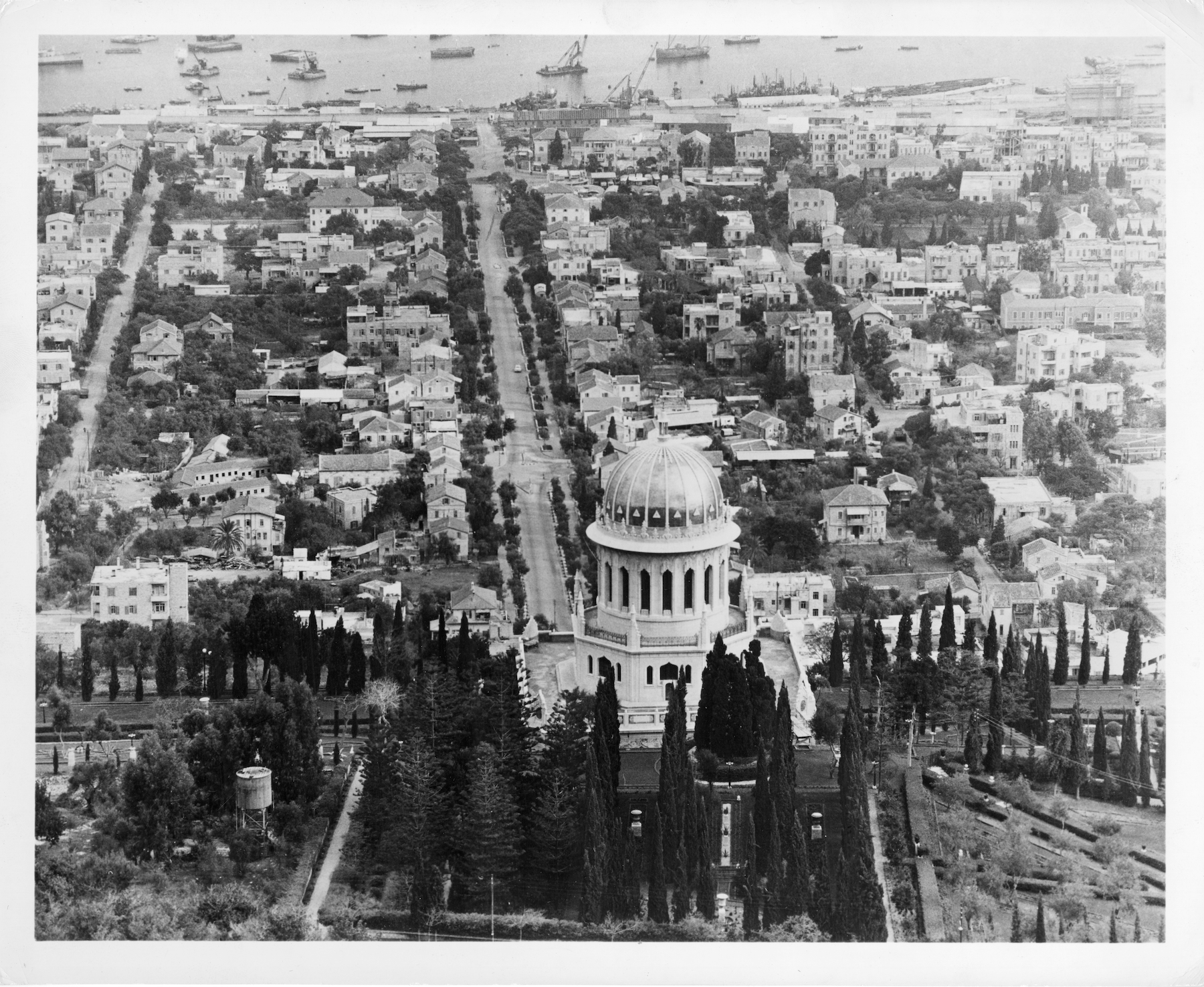

Bacground image: View of the Shrine of the Báb from the road which later became Ben Gurion Avenue (1905-1910). Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

After Shoghi Effendi approved the design for the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb on 25 December 1943, he needed to see an architectural model of the completed building, a perfect representation of what it would look like once built, before making any final decisions.

The level of skill required to produce such an intricate structure at such a small scale was almost impossible to find in Palestine in those days, and William Sutherland Maxwell did most of the work for the architectural model, delivering it to the Guardian in May 1944.

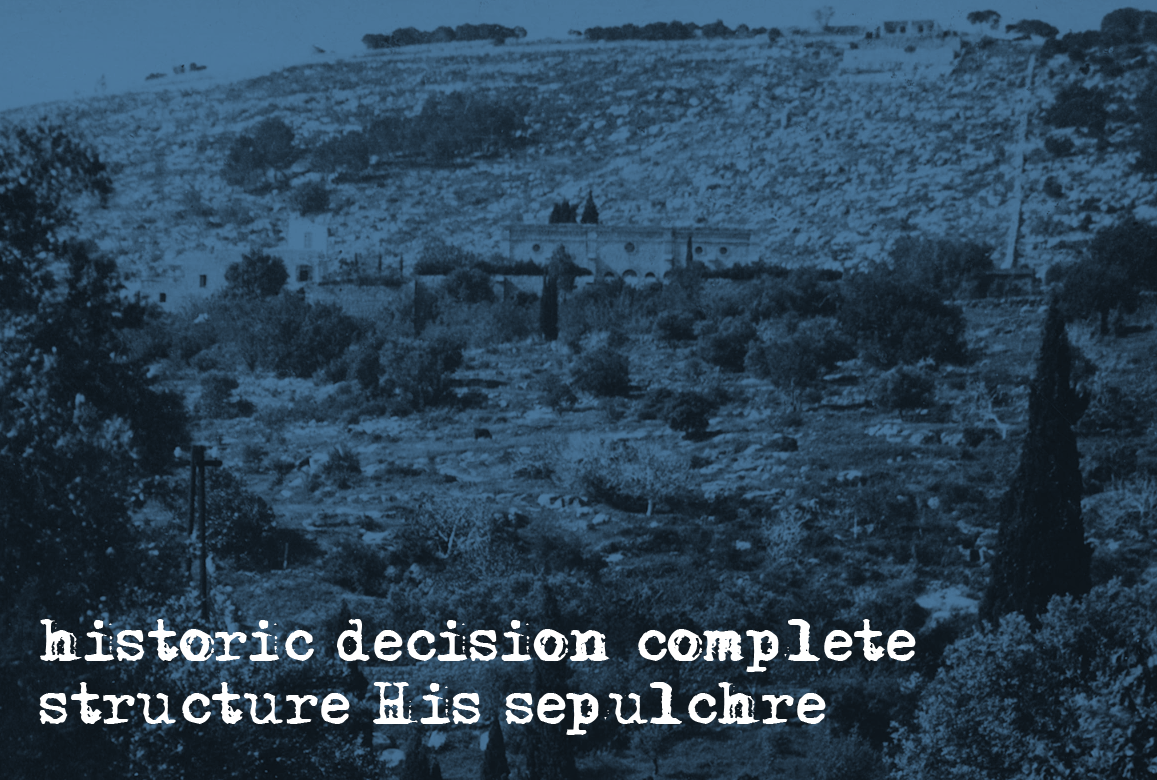

After carefully studying it, Shoghi Effendi came to his decision and on 22 May 1944, the press was informed that the design for the completed Shrine of the Báb had been chosen and that it would be built as soon as circumstances permitted.

In the afternoon of 23 May 1944, in the eastern Pilgrim House, Shoghi Effendi unveiled the model of what was essentially the Guardian’s design for the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb, executed to perfection by William Sutherland Maxwell—to a group of believers.

That same day, the Guardian announced to the Bahá'í world:

Announce friends joyful tidings hundredth anniversary Declaration Mission Martyred Herald Faith signalized by historic decision complete structure His sepulchre erected by 'Abdu'l-Bahá site chosen by Bahá'u'lláh. Recently designed model dome unveiled presence assembled believers. Praying early removal obstacles consummation stupendous Plan conceived by Founder Faith and hopes cherished Centre His Covenant.

For two years after this announcement, the project was on hold. The story continues on 15 December 1947 with the official start of the construction project.

Before the extraordinary story of the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb begins, we should pay tribute to the Guardian’s right-hand man in Italy, Hand of the Cause Dr. Ugo Giachery, and to his utterly stunning, his astonishing, pure-hearted, sincere tribute of love to his beloved Guardian, his unforgettable memoirs: Shoghi Effendi: Recollections.

Ugo Giachery spent 10 years from 1947 to 1957 serving the Guardian in fulfilling the crowning achievements of his ministry: developing the international endowments at the Bahá'í World Centre.

This book was the central pivot around which some of the most important stories of this chronology were carefully crafted: Ugo and Angeline Giachery’s precious pilgrim notes where profound moments in the unfolding of Bahá'í history and the Guardian’s Teaching Plans, the stories of the construction of the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb, the gardens and their nurseries, the embellishments to the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh, the Mansion of Bahjí, the International Bahá'í Archives, and the Obelisk erected by the Guardian on the Temple Land in Haifa, on Mount Carmel.

These memoirs are priceless because the book is an autobiography, and the author is not only a Hand of the Cause, but one intimately associated with the Guardian for an entire decade and a first-hand witness to the victories of the Guardian’s ministry.

Every page of this memoir is scintillating. Ugo Giachery’s utter humility, never calling attention to his own heroic efforts, and always giving the Guardian the credit makes this book exceedingly sweet to read. Ugo Giachery’s love for Shoghi Effendi suffuses each page, infuses each word, and bestows fragrance on the book as a whole, the fragrance of love and devotion to his beloved Guardian.

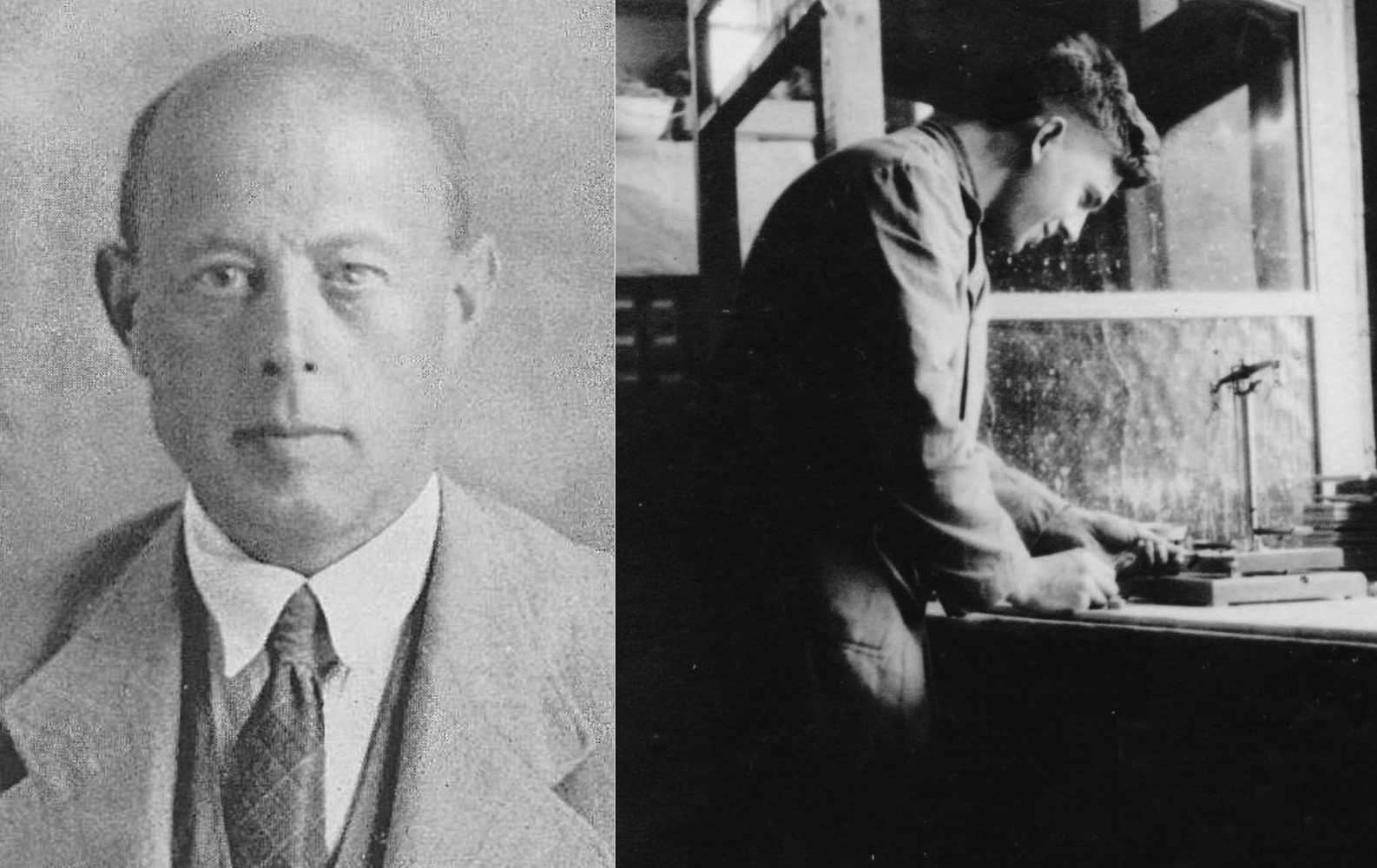

Dr. Ugo Giachery was a prominent Italian Bahá'í from an aristocratic Sicilian family. Dr. Giachery was a veteran of World War I, he was tall and distinguished, charming, and understood Italian bureaucracy.

When Dr. Giachery was wounded in World War I, he received a government scholarship, and obtained a doctorate in chemistry.

He would be invaluable to the Guardian.

In early 1947, Dr. Giachery and his wife Angeline had moved back to Italy at the Guardian’s request, and a few months later, in Spring 1947, he was already beginning work on the project of the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb.

At first, Dr. Giachery helped locate the perfect quarries in Italy for the exact stone that William Sutherland Maxwell had in mind, some of which had to match the hue of the original Palestinian stone for the Shrine built by 'Abdu'l-Bahá.

As the Guardian’s official personal representative, Dr. Giachery traveled throughout Italy, met with minister after minister in Rome, filled out endless forms, paid dues in advance, waited for hours, supervised the quarrying and cutting, sculpting and polishing, packing and shipping, sent cable after cable to Shoghi Effendi, and was generally present at every step of the way for six long and intense years.

Ugo Giachery’s services to the Guardian began in 1947 and continued for a decade until Shoghi Effendi’s passing in 1957. Ugo Giachery described this period of service to the Guardian in his memoirs as “a unique, once-in-a-lifetime experience of the deepest spiritual import that can only very inadequately be described or explained in words.”

The original Shrine built by 'Abdu'l-Bahá and completed in 1909, the beautiful watercolor design by William Sutherland Maxwell for the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb can be seen in transparency in the upper left corner. Background image:: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

Shoghi Effendi had announced his plans to erect the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb one year before the end of World War II. For two years, the Guardian had held back from inaugurating a Shrine Fund—no doubt because the Bahá'ís worldwide were suffering the economic repercussions of the end of the War, and also because the Bahá'ís in the West had strained themselves to win the goals of the First Seven Year Plan.

For two and a half years, between 23 May 1944 and late 1946, Bahá'ís did not hear from the Guardian about the Shrine of the Báb.

Then, on 11 April 1946, the Guardian asked William Sutherland Maxwell to set plans in motion for building the first part of the superstructure—the arcade and columns.

On 7 December 1947, the Guardian personally contacted the Haifa Local Building and Town Planning Commission applying for a building permit for the construction work, and his letter is at the same time tactful, eloquent, and clear.

Shoghi Effendi attached drawings and an application to his cover letter to the Haifa Local Building and Town Planning Commission, with a majestic cover note explaining the project in great detail:

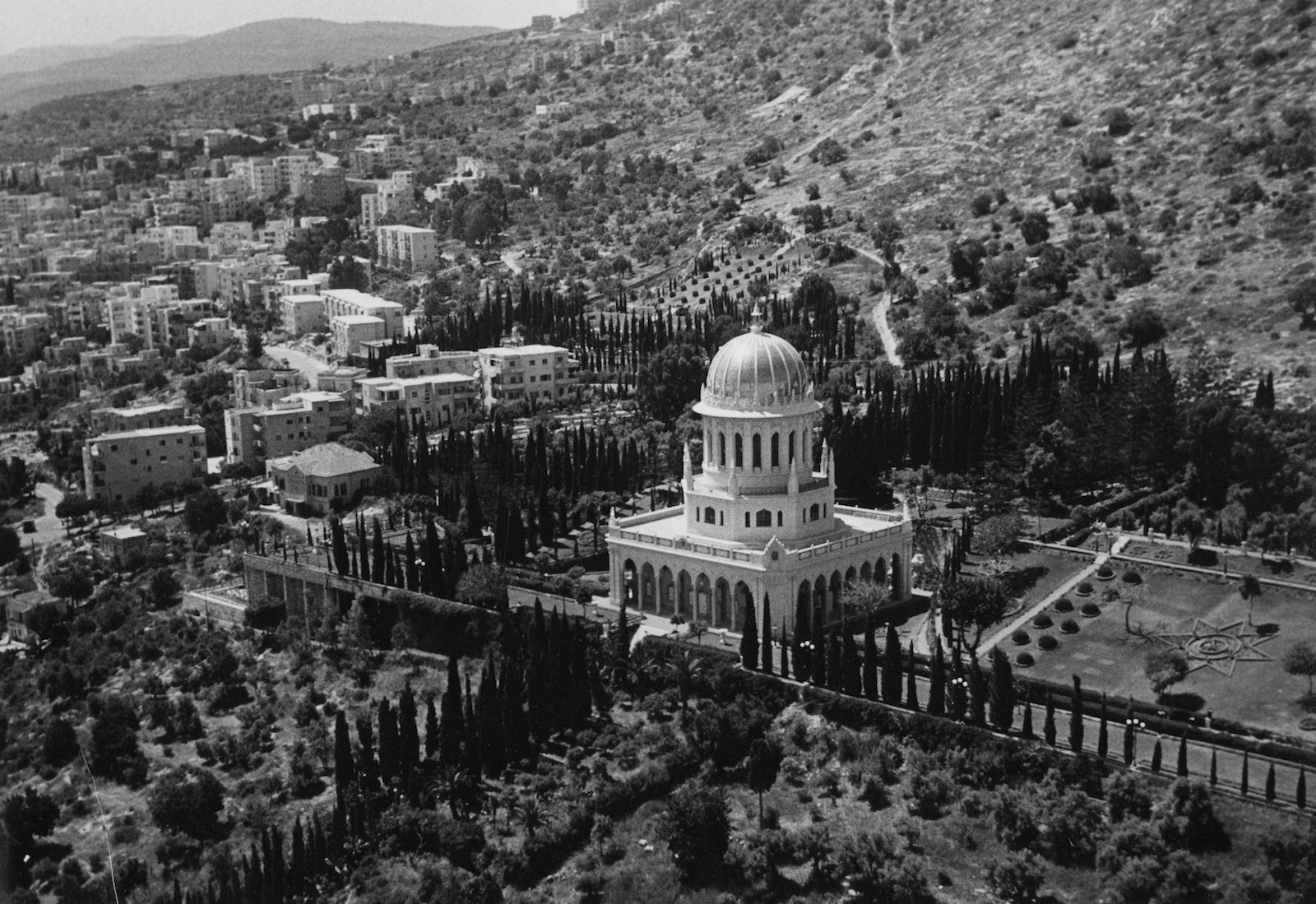

The Tomb of the Bab, and of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, so well-known to the people of Haifa as 'Abbas Effendi, is already in existence on Mt. Carmel in an incomplete form. In its present state, in spite of the extensive gardens surrounding it, it is a homely building with a fortress-like appearance.

It is my intention to now begin the completion of this building by preserving the original structure and at the same time embellishing it with a monumental building of great beauty, thus adding to the general improvement in the appearance of the slopes of Mt. Carmel.

The purpose of this building will, when completed remain the same as at present. In other words it will be used exclusively as a Shrine entombing the remains of the Bab.

As you will see from the accompanying drawings the completed structure will comprise an arcade of twenty four marble or other monolith columns surmounted by an ornamental balustrade, on the first floor or ground floor of the building. It is this part of the building that we wish to begin work on at once, leaving the intermediary section and the dome, which will surmount the whole edifice when completed, to be carried on in the future, if possible at an early date after the completion of the ground floor arcade.

The Architect of this monument building is Mr. W.S. Maxwell, F.R.I.B.A., F.R.A.I.C., R.C.A., the well-known Canadian architect, whose firm built the Chateau Frontenac Hotel in Quebec, the House of Parliament in Regina, the Art Gallery, Church of the Messiah, various Bank buildings, etc., in Montreal. I feel the beauty of his design for the completion of the Bab's Tomb will add greatly to appearance of our city and be an added attraction for visitors.

Two weeks later, on 15 December Shoghi Effendi cabled America:

Happy announce completion of plans and specifications for erection of arcade surrounding the Bab's Sepulchre constituting first step in process destined to culminate in construction of the Dome anticipated by 'Abdu'l-Bahá and marking consummation of enterprise initiated by Him fifty years ago according to instructions given Him by Bahá'u'lláh.

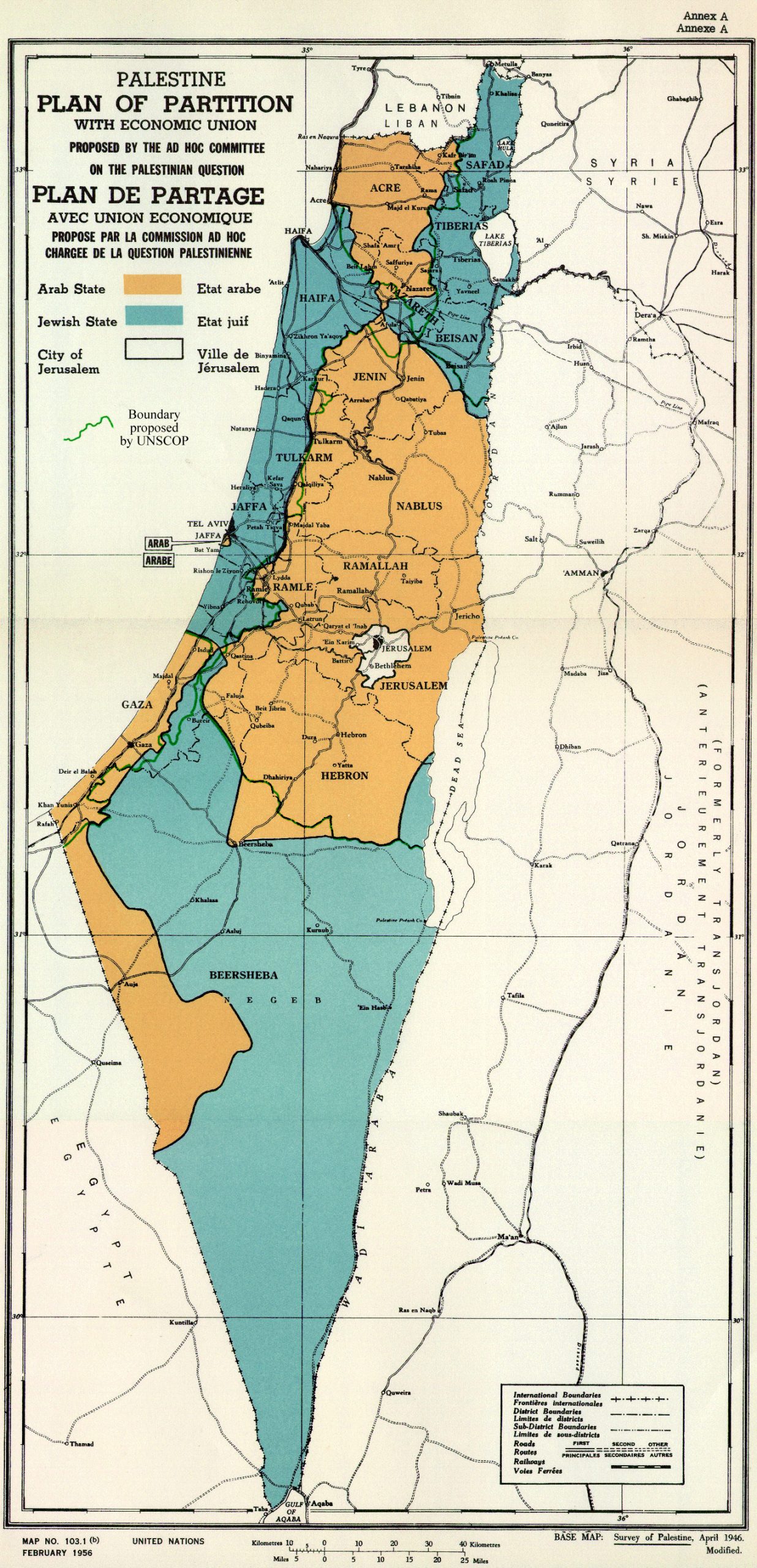

The Guardian’s project of the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb was now official. As the project had officially launched, the Guardian made a decision of pure genius. Palestine in 1947 did not have the skilled laborers to carve the intricate stone work on the hundreds of tons of granite and marble for the Shrine, so Shoghi Effendi simply decided to have the Shrine built in Italy and shipped to Haifa.

The story continues on 13 December 1948 with a first section on Dr. Ugo Giachery.

February 1956 Map of UN Partition Plan for Palestine, adopted 29 Nov 1947, with boundary of previous UNSCOP partition plan added in green. Source: Wikimedia Commons

When the project was just beginning, in 1947/1948, the State of Israel was about to be proclaimed—and then it was proclaimed—and it became obvious to Shoghi Effendi that the economy of this brand new country was going to undergo immense changes. There would be a period of readjustment of both its industries and its workforce.

At first, the Guardian tried to source building materials locally, but with insignificant results. There was an influx of Jews fleeing to their new homeland after having been savagely and monstrously persecuted in the Nazi extermination camps and ghettos of World War II, and they needed housing. It was the priority of the new State, and the Guardian immediately realized that all construction material would be diverted in priority to this most important and worthy cause.

And so, the Guardian immediately thought of procuring the initial necessary building materials from Italy. But the situation there in 1948 was not much better than in Israel, and it would take a miracle to find the materials to build the superstructure.

Shoghi Effendi's judgement and decision proved to be essentially prophetic—and timely—if he had waited one year before instructing Ugo Giachery to source the materials, the cost would have been prohibitive, and he could never have built the Shrine.

Italy had been destroyed after the war. In this photograph, the men of the 5th Northamptonshire Regiment of the British Army pick their way through the ruins of Argenta, Italy on 18 April 1945. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The situation in Italy, in some ways, was even more critical than that in Israel. After all, Italy had been decimated during World War II, which had taken place on its soil, and the country needed to be rebuilt, so building materials were in high demand, and almost impossible to obtain, especially for international export. They were needed locally and nationally.

Italy was just in the stage of beginning to recover from its ravaged, disastrous war economy. Because Benito Mussolini—its leader during the war—was a Fascist who had sided with Hitler, Italy was forced—like Germany—to pay reparations to the Allied Nations—France, Britain, etc.

To add to complications, there was the famous Italian bureaucracy, almost a work of art in its convolutedness. Every item of building material was controlled by licenses issued by the Ministry of Industry and Commerce, and only granted after a lengthy application process. If the application was for export—which was the case with everything Ugo Giachery needed to source—there was another complex permission to obtain from the Ministry of Foreign Trade, with another approval needed from the Ministry of Finance, which controlled Customs for all of Italy.

Two other unforeseen complications arose: one was that, although Bahá'ís were banned from teaching the Faith in Italy, they were still systematically harassed by the police, as Ugo and Angeline Giachery experienced regularly.

The second complication was that marble and other building materials were highly sought after and scarce.

But there were several things working in the Guardian’s favor. One, was that a lot of workers were out of jobs, and a lot of factories needed contracts, so the big project of the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb was welcome, and labor was not as expensive as it would be even 12 months from the start of the project.

Another positive factor in favor of the Guardian, was that, in the ravaged economy of Italy, any influx of foreign currency was not only welcome but eagerly courted, and the Guardian was going to pay for everything in US Dollars. Ugo Giachery had something very substantial to bargain with in his negotiations.

The procurement of the marble and all other building material for export to Haifa was highly coveted, even though scarcity of the materials, as already explained, raised many difficulties at every turn.

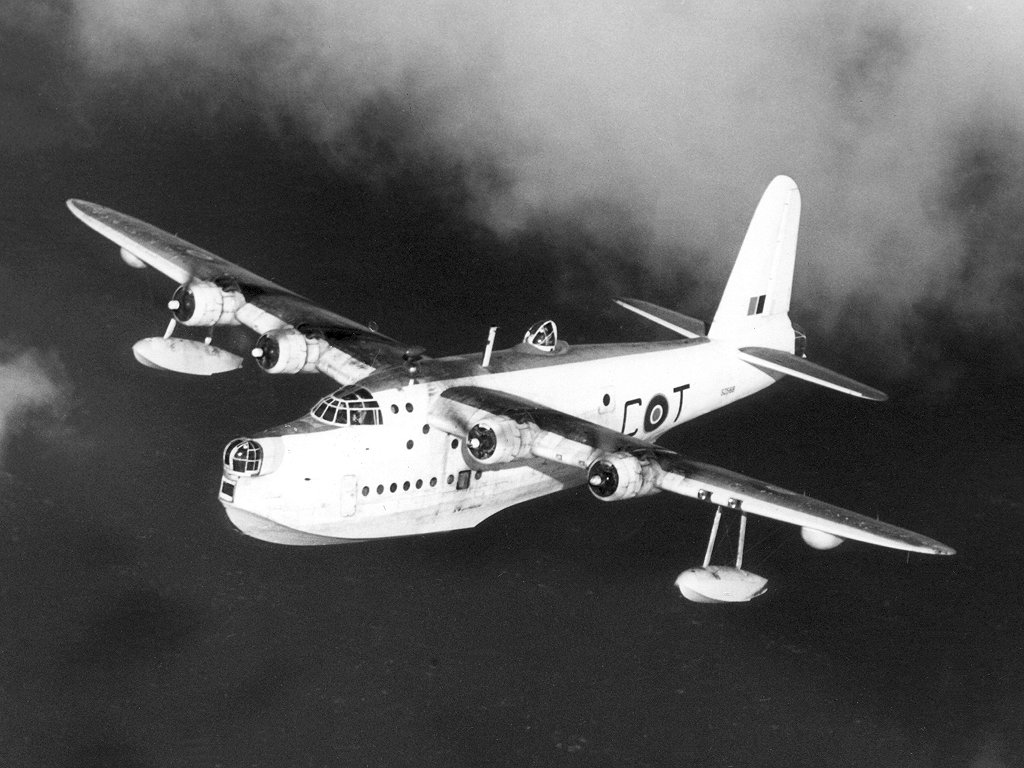

A Short Sunderland Mark V, formerly flying boat patrol bombers during the war, developed and constructed by Short Brothers for the Royal Air Force (RAF).The Short Sunderlands were demilitarized on the production line for service as mail carriers to outposts of the British Empire such as Nigeria and India. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

At the very beginning of Ugo Giachery’s sourcing work in Italy, the Guardian had instructed him to send him photographs of all clay and plaster models of the intricate decorative parts, for his approval, before beginning carving them out of marble. Communication with the Holy Land was difficult: messages, photographs and construction plans had to be sent by unscheduled airplanes in packages taken to the Rome airport, and called for at the airport in Haifa. There was a constant element of uncertainty.

Fortunately, however, telegrams and cablegrams, accepted at the sender's risk, were quick, efficient, and only rarely delayed, so that was the number one method of communication between Ugo Giachery and the Guardian.

Photograph on the left: The original Shrine of the Báb, erected by 'Abdu'l-Bahá, before the superstructure was built. This photograph clearly shows the quality of the local stone used by 'Abdu'l-Bahá, particularly its texture. Source: The Bahá'í World, Volume 11, page 17. Photograph on the right: This image shows the delightful rose-tinted color of the original stone, which matched the Rose Baveno granite chosen ty the Guardian so perfectly. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

At the start of the construction of the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb, Shoghi Effendi had given serious consideration to the possibility of using local stone and local labor to build the superstructure—the same stone and labor which 'Abdu'l-Bahá had Himself used in building the original Shrine. At the time, Israeli and Egyptian stonemasons were the most skilled in the Middle East. The political situation interfered with Shoghi Effendi’s original plan.

After the end of the British Mandate and the creation of the State of Israel, there had been a mass exodus of Arab locals, and with them, most of the skilled artisans had left the country. Shoghi Effendi found himself with only one option: Italy.

For two millennia since Roman times, Italians had established themselves as the world’s foremost center for marble quarrying, cutting, and sculpting. The artisans working marble and granite in Italy were masters at their craft, handed down through centuries. And Italian quarries had the world’s most exquisite marble and granite, of every tint imaginable.

As an abstract illustration for a single response from Italy, a 1949 Italian postcard of Madonna-di-Campiglio, in the region of Trento where there are stone quarries. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

William Sutherland Maxwell started preparing for his exploratory trip to Italy in the early spring of 1949. First, he had written to his architect friends in Canada and procured the addresses of reliable marble quarries. One of his friends, Mr. Allen, had particularly recommended the Guido M. Fabbricotti firm. Then, William Sutherland Maxwell had written to a few of these firms, including the one Allen had mentioned, hoping for favorable responses.

He received only one answer, from the Guido M. Fabbricotti marble quarry recommended by his friend, and this is the story of how he received their letter. But first, a little marble history and an introduction to the two important Italians in this story.

Guido M. Fabbricotti was a marble quarry founded in Carrara in 1722, and by 1948, it had a reputation for being the best marble firm in Italy. The two partners at Guido M. Fabbricotti were Dr. Orlando A. Lazzareschi, and Colonel Alberto Bufalini, a former officer in the Royal Carabinieri, with Professor Andrea Rocca as their technical adviser.

Professor Andrea Rocca was born of a long line of marble craftsmen who, as he used to say, went back to the days of ancient Rome and had graduated from the Accademia delle Belle Arti (Academy of Fine Arts) of Carrara in the early 20th century and he was a brilliant architect. Professor Rocca was endowed with an encyclopedic unmatched knowledge of granite, marble and other building materials. During the post-war years, Professor Rocca had been struggling to find a way to make ends meet, calling, almost every morning, the various marble firms in Carrara in the hopes of finding a job. Until the spring of 1948. A few months later, he would be busier than he had ever been in his life.

One morning, in the early spring of 1948, Professor Rocca entered the Fabbricotti office as one of the partners was crumpling in his hand what appeared to be a letter. As he was throwing it into the waste-basket, Professor Rocca asked:

What is that you are throwing away?

Oh, it is only a preposterous request for information that sounds like a fable, something about a grandiose mausoleum to be erected in the Holy Land! But who can build such a costly structure at this time? Let us forget about it.

Professor Rocca bent down and pulled the crumpled letter out of the waste-basket, saying:

Let us read this again, together.

As soon as he read the letter, Professor Rocca, a man of true vision, knew this was the opportunity of a lifetime, and with some convincing on his part, he got the Fabbricotti firm on board.

From that moment on, Professor Rocca would be the most enthusiastic and indefatigable supporter and advocate of the Guardian’s “grandiose mausoleum.”

A 1952 photograph of a Braathens South Africa Far East Air Company plane. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

On 2 April 1948 Shoghi Effendi cabled Ugo Giachery, informing him that his architect, William Sutherland Maxwell, would be arriving in Rome on a Braathens South Africa Far East Air Company plane on 13 April 1948, accompanied by Benjamin Weeden, an American Bahá'í who had just begun serving at the Bahá'í World Centre, having arrived two weeks earlier on 19 March 1948.

Because William Sutherland Maxwell was a British citizen, he didn’t. need a visa for Italy, but Ben Weeden was American, and because of the local conditions in Israel at the time, he couldn’t obtain his Italian visa in Jerusalem, and Shoghi Effendi asked Ugo Giachery to meet them at the plane and arrange to get Ben an Italian visa on arrival. If this was not possible, the Guardian said that Ben Weeden should remain on the same Braathens plane and continue to Geneva to obtain a visa there.

Rolls Royce Armoured Car , this would have been the kind of taxi William Sutherland Maxwell and Ben Weeden left Haifa in. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

On 11 April 1948, William Sutherland Maxwell and Ben Weeden left Haifa in an armored taxi for Tel Aviv, on their momentous. Mission to sign contracts for the stone of the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb. They had a letter from the Guardian dated from the same day which read:

To Whom it may Concern: This is to introduce Mr. W. S. Maxwell, F.R.I.B.A., who is a member of the Bahá’í Community and has been residing in Haifa with me since 1940. He is my father-in-law and is proceeding to Italy in connection with work to be carried out on one of our Bahá’í Shrines on Mt. Carmel. He is accompanied by Mr. Benjamin Weeden, a Bahá’í from the United States of America, who is likewise occupied here in Haifa in serving the Bahá’í Faith at its World Centre. Mr. Weeden is proceeding to Italy to assist Mr. Maxwell in his work there. I, as Head of the Bahá’í Faith, would appreciate every assistance being rendered to these two gentlemen in discharging their tasks and in facilitating their journey and safe transit through Palestine territory. Shoghi Rabbani, Head of the Bahá’í Faith. House of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá 7 Persian Street, Haifa

Rome in 1948. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

William Sutherland Maxwell and Ben Weeden arrived in Tel Aviv on 11 April 1948, they were frustrated by repeated delays for their departure, heard gunshots in the city at night, but finally were able to board a four-engined American-made Norwegian plane staffed by capable Norwegians. They were two of about 40 passengers and flew by night, arriving a few hours later, in the early morning above Italy, the plane descending from the clouds to offer them a view of the River Tiber.

William Sutherland Maxwell and Ben Weeden finally landed at Rome’s Ciampino airport on 16 April 1948. Ugo Giachery, who had gone to the airport to meet them several times unsuccessfully since 13 April—when they were originally supposed to have arrived—had been at the airport waiting for them for hours, and finally, at long last, saw them come down the ramp, and cheerfully greeted them with a loving embrace.

William Sutherland Maxwell’s blue eyes were smiling as he told Ugo Giachery:

You were the last to bid me farewell when I left for Europe…and you are the first to bid me welcome on European soil.

Shoghi Effendi was relieved to hear that William Sutherland Maxwell and Ben had finally arrived in Italy and cabled on 19 April 1948:

Delighted safe arrival stop praying success stop love friends. Shoghi.

Ugo and Angeline Giachery were delighted to have William Sutherland Maxwell in Rome with them. Because the rents in Rome had skyrocketed after World War II, they were living in the Hotel Savoia, and William Sutherland Maxwell took a room in the same hotel.

Just one example of the devastation visited on Italy during the Second World War: The San Tommaso Cathedral in Ortona was literally gutted during the December 1943 fighting. Photo by Terry F. Rowe. Department of National Defence / National Archives of Canada, PA-136308. Source: The Juno Beach Centre.

Italy was reeling from the destruction of World War II. Public services were almost non-existent, all of the Italian railroads had been catastrophically damaged, the locomotives, freight and passenger cars had all been confiscated, shipping was at a standstill.

Millions of Italians were prisoners of war in almost every continent, food, electricity and water were rationed and almost unavailable.

Italy was overcome with gloom and despair, and absolutely no hope of relief in rebuilding its shattered economy.

This was mainly why William Sutherland Maxwell only received one response to his many inquiries to marble quarries, but even that small ray of hope from a single response was uncertain: practically none of the marble quarries in the Apuan Mountains of Tuscany—the place where the best finest marble was quarried—were open. That, and the fact that any skilled and specialized artisans had been widely dispersed during the War.

A modern exhibit at the marble museum of Carrara, Italy showing the variety of colors and textures marble comes in. Source: Vacanze in Versilia.

The instructions Shoghi Effendi had given William Sutherland Maxwell was to find marble or granite which would last at least 500 years. On 25 April 1948, William Sutherland Maxwell went to the Chief of police to get a form filled out, and coming back, had the idea to ask Ugo Giachery if there was a government geological museum in Rome.

There was: Museo di Mineralogia della Sapienza Università di Roma (the Museum of Mineralogy at the Sapienza University of Rome), founded in 1873 which housed 19th collections of ancient marbles including the prestigious collection by Thomas Belli which includes about 550 tiles, cut from pieces of ornamental stones, that came to light during the excavations of ancient Rome.

When William Sutherland Maxwell and Ugo Giachery arrived at the Museum, they were welcomed by the Curator of the Museum himself, an expert in marble and Professor at Sapienza University, and he gave them a guided tour.

They carefully and meticulously examined dozens of specimens of marble and granite to select the one most perfectly suited to the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb, and showed the Curator a sample William Sutherland Maxwell had brought of the original Palestinian stone used by 'Abdu'l-Bahá in the original Shrine. The Curator confirmed they had the same stone, and after inspection, William Sutherland Maxwell and Ugo Giachery found it was perfect for everything but the columns themselves.

The Curator also confirmed with them that the best firm to source the granite they needed for the columns was the firm they were already in touch with—Guido M. Fabbricotti—he spoke highly about the firm, confirming it was the best in Italy, and also spoke well of Colonel Alberto Bufalini. William Sutherland Maxwell felt pleased and confirmed in his efforts.

But, still, time was running out.

The Guardian had called Ugo Giachery with instructions to find the quarry as soon as possible, to urgently identify the correct stone—marble or granite—to make a decision regarding its carving and to ship the finished pieces to the Holy Land.

The Fabbricotti firm in the early 20th century. Source: GM Fabbricotti.

William Sutherland Maxwell invited the two partners of Guido M. Fabbricotti to meet with him in Rome and establish their willingness to participate in the audacious project of the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb.

The first stage was to be the arcade of columns over the initial Shrine constructed by 'Abdu'l-Bahá. For purely financial reasons, due to the dismal post-war worldwide economic situation, the Guardian had limited funds to work with and divided the project into several successive stages, the first one being the colonnade.

William Sutherland Maxwell’s design for the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb was a columned arcade completely surrounding the original structure, protecting the four sides of the Shrine, creating a beautiful space for pilgrims to circumambulate the Shrines of the Báb and 'Abdu'l-Bahá, and having the added benefit of extending the base of the original Shrine in order to support the octagon, the drum and the dome.

The initial consultations between William Sutherland Maxwell and the Guido M. Fabbricotti firm were to ensure that there would be enough material to complete the arcade, the first stage of construction. This was where Professor Rocca—Guido M. Fabbricotti’s brilliant adviser whom William Sutherland Maxwell had not yet met—came into play.

Top series of 2 photographs: a detail of the smooth texture and beige cream color of Chiampo Paglierino marble, and on the right, in its final form, as the stone of the arcade around the Shrine of the Báb. Bottom series of 3 photographs: Rose Baveno granite in its raw form, polished, and on the right, in its final form, as one of the columns surrounding the Shrine of the Báb under the arcade.

Professor Rocca first started looking for the marble or granite in the obvious place—Carrara. But his search there yielded no suitable material, so he traveled to the region of Venice to investigate the possibility of using Chiampo Paglierino marble, which, as divine providence would have it, was of a creamy rosy color that matched the original Palestinian stone of 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s Shrine perfectly.

The Chiampo quarries were located between Verona—the fabled home of Romeo and Juliet—and Vicenza in the Vicentine Alps and were a treasure trove of massive quantities of marble of various colors. The Chiampo marble would be used in the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb for the arches, capitals, walls, corners and balustrade.

Professor Rocca then traveled high into the western Alps, 200 kilometers northwest of Chiampo on the border with France and Switzerland for the Baveno quarry, which quarried the exquisite Rose Baveno granite—pink granite flecked with delicate white and grey crystals—needed for the columns, pilasters and bases of the superstructure.

William Sutherland Maxwell’s design called for 24 columns and 8 pilasters—essentially “corner columns”—all monolithic as per the Guardian’s express request. This quarry had been outside the war zone, and so the difficulties in obtaining the granite were simply mechanical and easily solved with ingenuity and perseverance.

Once Professor Rocca had visited the two quarries, his expert opinion filled William Sutherland Maxwell, Ugo Giachery and Ben Weeden with joy: he confirmed that they could obtain the highest, finest quality marble and granite that Italy had to offer.

Now the project could begin its second phase, but first, William Sutherland Maxwell and Professor Rocca needed to meet in person.

A modern marble quarry in Cava Lazzareschi, Colonnata, Italy. Photo by Gianluigi Marin on Unsplash.

Some weeks after his arrival, William Sutherland Maxwell met Professor Andrea Rocca in Rome, and immediately knew Professor Rocca was the ideal and perfect man for the job of finding the stone for the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb. William Sutherland Maxwell knew that with Professor Rocca at the helm, all the stone work of the Shrine of the Báb would be in competent and knowledgeable hands, and that his devotion to the project, which had become second nature to him, would ensure the work would proceed with the least amount of errors.

Together, William Sutherland Maxwell and Professor Rocca formed a top-notch team of surveyors to the Chiampo and Baveno quarries to select the perfect marble and granite, then travel to the workshops which would cut and carve the stone with the highest degree of skill.

After completing the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb, William Sutherland Maxwell and Professor Rocca would team up again for the International Bahá'í Archives. All told, their partnership lasted well over 10 years during which, time and again, William Sutherland Maxwell learned to appreciate and admire Professor Rocca’s great talent and versatility in his novel use of marble. Professor Rocca for his part, developed a boundless love and admiration for the Guardian.

Background image: historical photograph of the Fabbricotti marble firm which began operation in 1722, bringing 200 years of family experience and expertise to the construction project of the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb. Source: GM Fabbricotti.

After the initial meeting with the Guido M. Fabbricotti firm, Ugo Giachery was intensely busy. William Sutherland Maxwell’s designs were discussed in minute detail, and every word of these consultations had to be translated from Italian into English and back into Italian with absolute accuracy.

Guido M. Fabbricotti spent several days crunching numbers, and thinking of every last cost in order to quote the Guardian the most accurate rates that took into account the best workmanship possible. They were extremely precise, down to including the wooden crates for shipping the finished work.

Ben Weeden and William Sutherland Maxwell had sent the Guardian several cables to keep him apprised of the negotiations with the Guido M. Fabbricotti firm, including when the first contract was drafted. The Guardian approved it, and William Sutherland Maxwell signed it on 29 April 1948. A second contract, requested by the Guardian was prepared and signed on 5 May 1948.

Once the two contracts were signed, the wheels were in motion for an army of specialists to begin their historic work. The team assembled by William Sutherland Maxwell, Professor Rocca, and the Guido M. Fabbricotti, spanned all of Italy, from Carrara to Chiampo, to Baveno, to Pietrasanta, and included the most skilled, competent, and artistic marble and granite sculptors in all of Italy.

Had the Guardian waited a single year to place the contracts, none of the artisans, none of the quarries, and none of the workshops would have been available. In all things, Shoghi Effendi was divinely guided.

After the contracts had been signed, William Sutherland Maxwell held consultations with the architects and technical experts. Ugo Giachery’s role was to act as the Guardian’s personal representative, select the granite and marble, supervise the cutting and carving, oversee the proper packing and shipping, handle all insurance matters, and manage the massive amount of mail and technical data produced by this immense project.

An apprentice carving a block of stone manually, the way that the stonemasons in Italy carved all the ornamentation around the Shrine of the Báb. The original uploader was Flassig Reiner at German Wikipedia.(Original text: Reiner) - Self-photographed, CC BY-SA 2.0 de. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

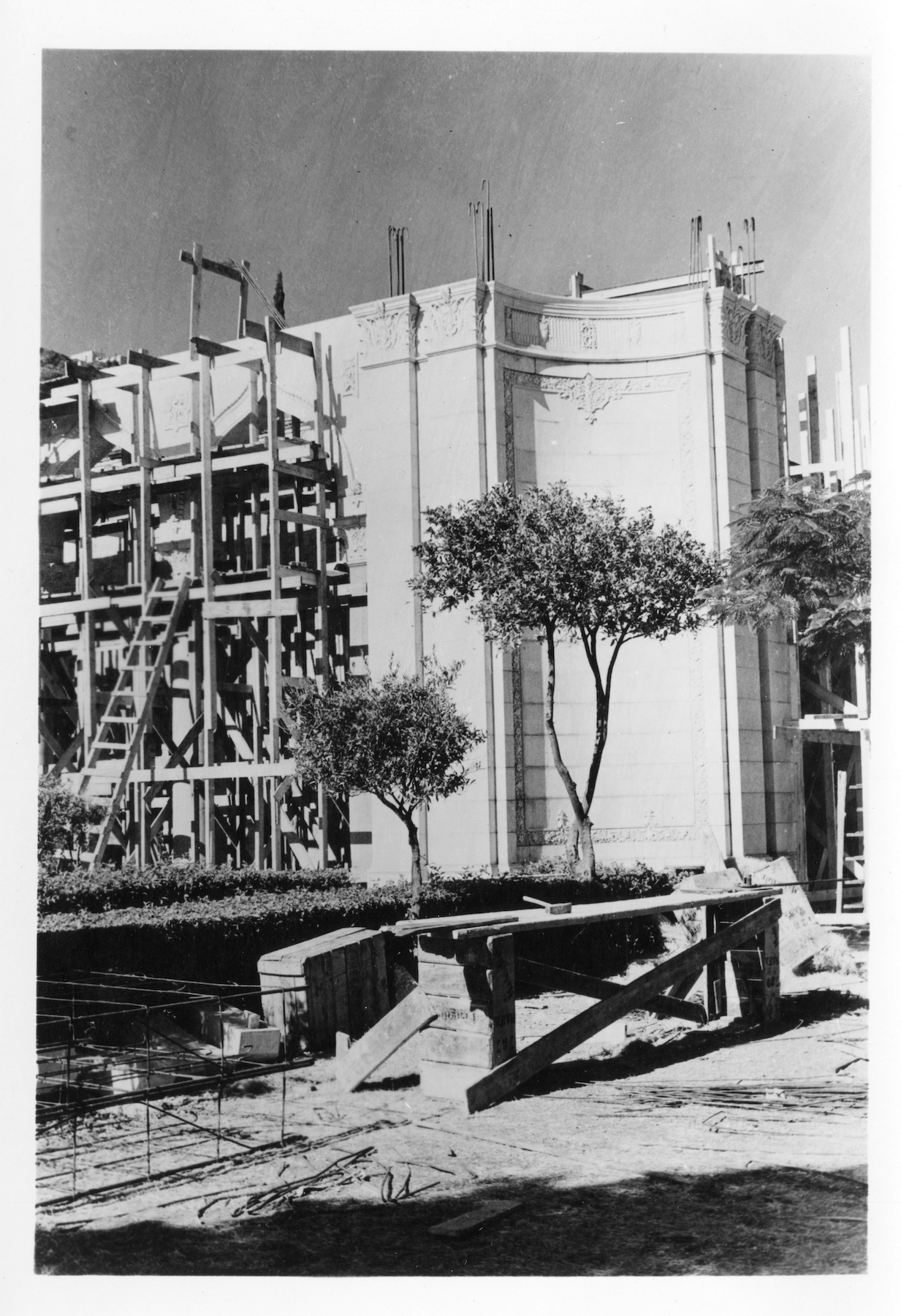

The Chiampo Paglierino marble quarried in the Vicentine Alps was brought 200 kilometers southwest to the small city of Pietrasanta in the pre-Apennine hills of the Apuan mountain chain for cutting, carving and sculpting.

Pietrasanta—literally “sacred stone”—had been the beating heart of the marble industry in Tuscany for 1,000 years and was strategically placed between the quarries and a secondary railroad track that stopped 90 meters from the town.

The Pietrasanta team which would work on the Chiampo marble for the arcade was composed of 60 men from 100 different regional firms involved in marble sculpting. Many of the men were graduates of the finest art academies of Italy, others were established, reputable sculptors who would model the capitals of the columns and pilasters, the panels of the facade and the decorative elements of the balustrade parts in clay

Skilled draftsmen enlarged to actual size all of William Sutherland Maxwell’s designs—thousands of drawings of every single block or stone or ornamentation, in order to enable the stonemasons and carvers to reproduce every detail to perfection.

The Guardian’s 24 monolithic Rose Baveno granite columns were carved at a workshop at the foot of the mountain where the stone was quarried.

For each column required a block of granite four times its size which had to be brought down from the mountain with great difficulty.

After a whirlwind intense month of adventures, discoveries, and phenomenal success, William Sutherland Maxwell and Ben Weeden returned to the Holy Land on 15 May 1948, having brilliantly accomplished the complex mission the Guardian had entrusted them with.

They were bringing their beloved Guardian the most wonderful news: the construction of the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb could begin. Everything was in place: quarries, stonemasons, contracts.

History was about to be made.

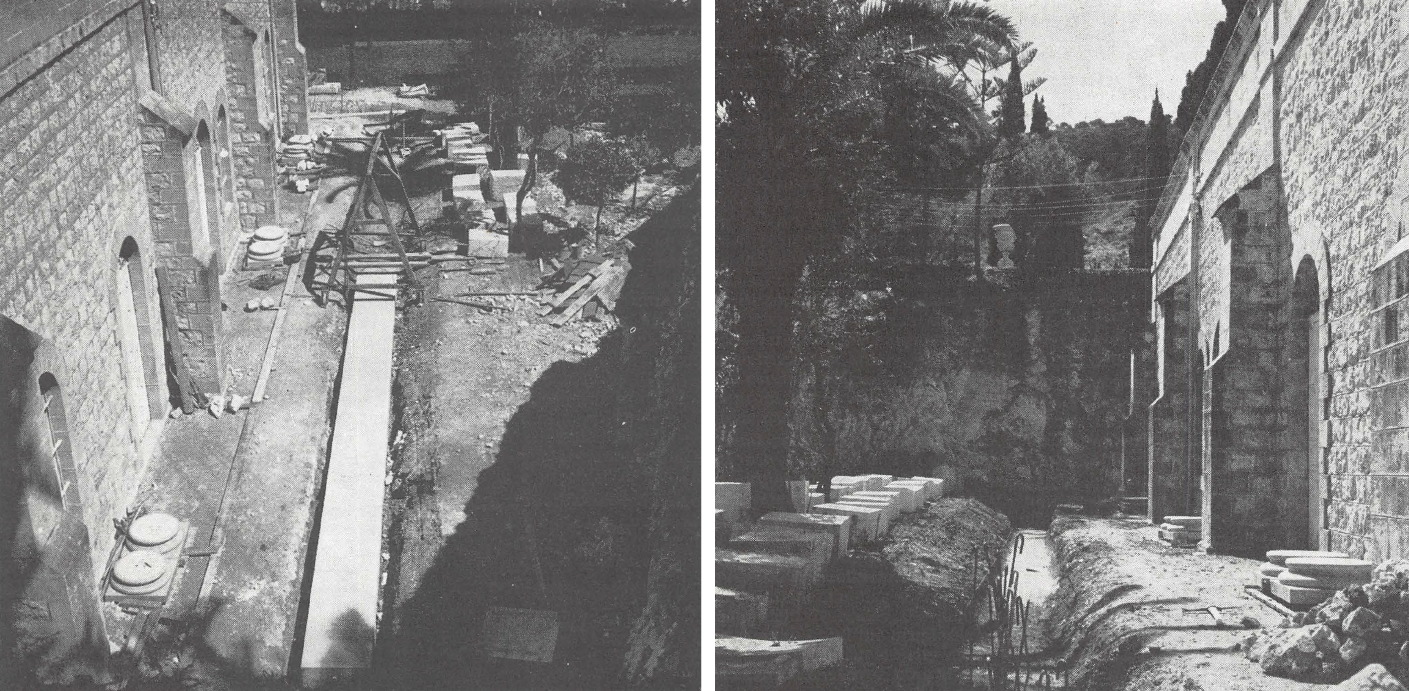

Photo on the left: Chiampo stone foundations awaiting erection of columns.Photo on the right: Trench of reinforced concrete upon which foundation stones supporting columns will be laid in constructing the Arcade of the Shrine of the Báb. Source: The Bahá'í World Volume 11, pages 61 and 62.

When William Sutherland Maxwell returned to the Holy Land from his one-month trip to Italy, he sought the assistance of a valuable collaborator, the engineer of the project, Dr. Heinrich Neumann, of the Hebrew Technical College.

Together, William Sutherland Maxwell and Dr. Heinrich Neumann, prepared the structural plans for laying the foundation and erecting the first elements of the colonnade.

A few weeks later, the Guardian authorized Ugo Giachery to sign contracts for the marble to be used in the facades up to and including the balustrades, and approved the clay and plaster models for all the decorative parts of this stage of the construction to Ugo Giachery.

Photograph on the left: Deep excavations into the rock of the mountain were necessary on the southern side of the Shrine of the Báb to make place for the new Arcade added to original building. Photograph on the right: Retaining wall being erected to hold fill in an extension of the terrace facing the Shrine of the Báb. Source: The Bahá'í World Volume 11, pages 59 and 60.

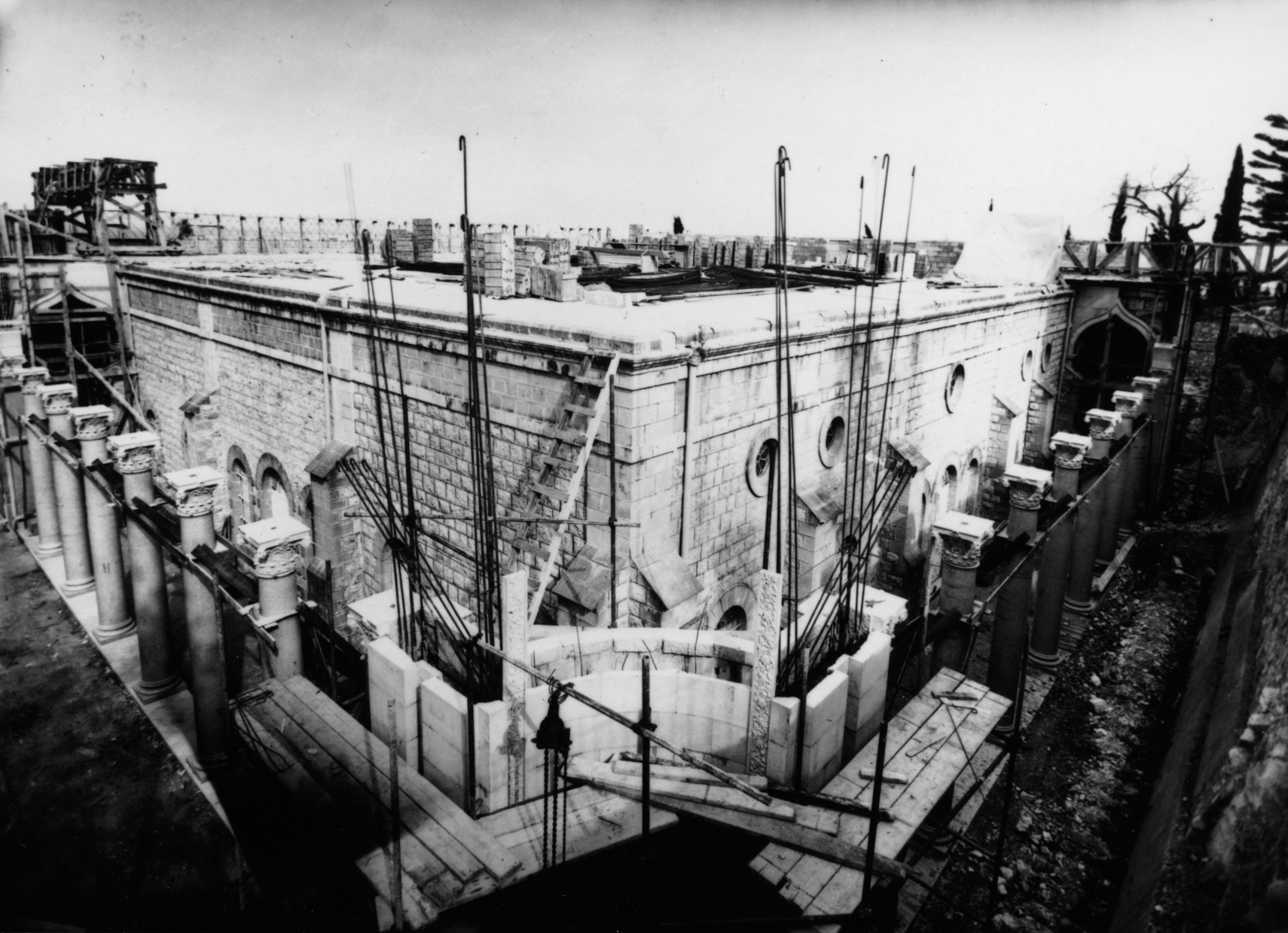

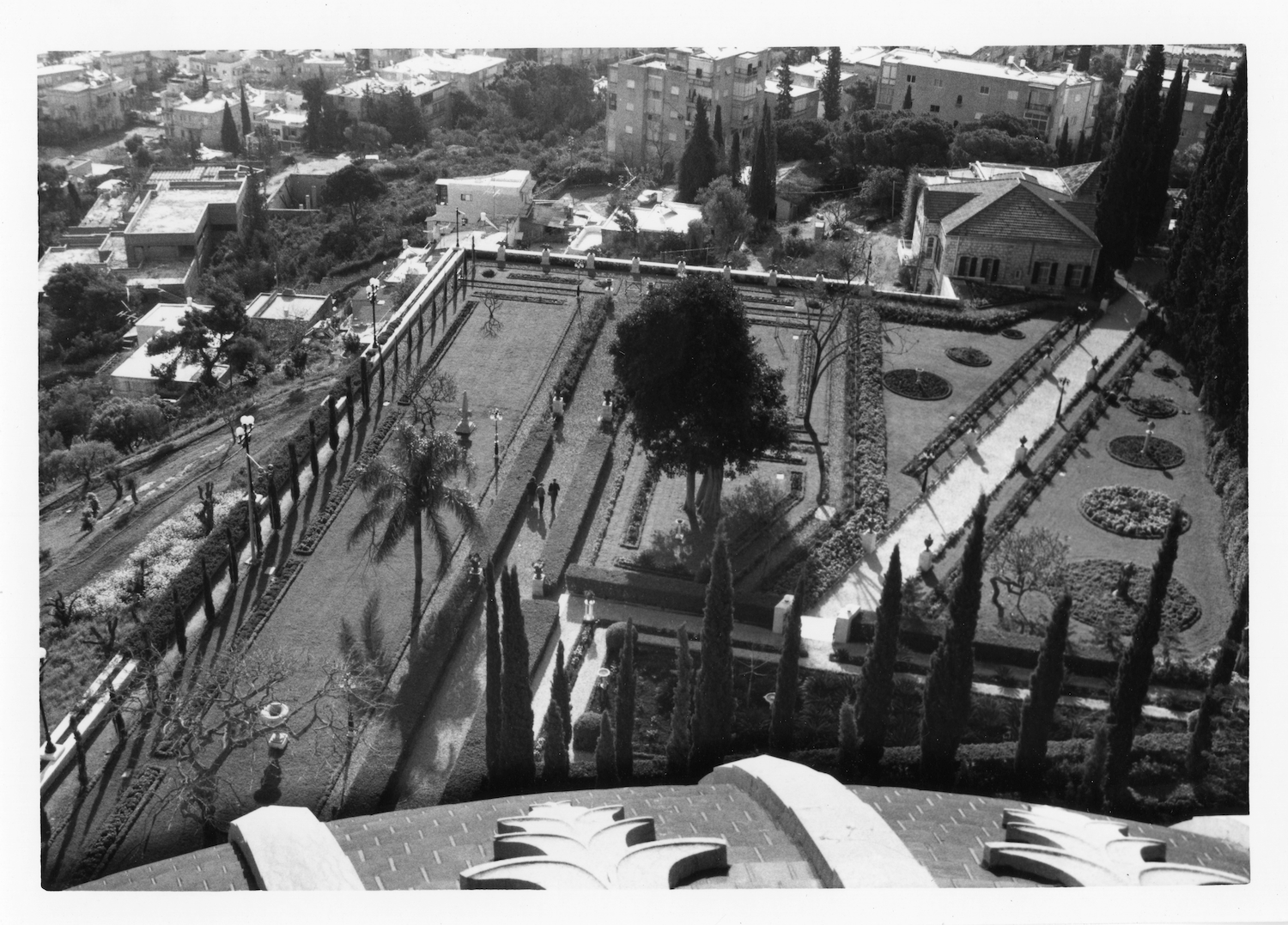

Immediately after William Sutherland Maxwell and Ben Weeden’s return from Italy, the Guardian was overjoyed and began preparing the ground around the Shrine of the Báb for the foundation of the arcade. For this, Shoghi Effendi had to further excavate Mount Carmel, because the superstructure would double the base of the original Shrine built by 'Abdu'l-Bahá.

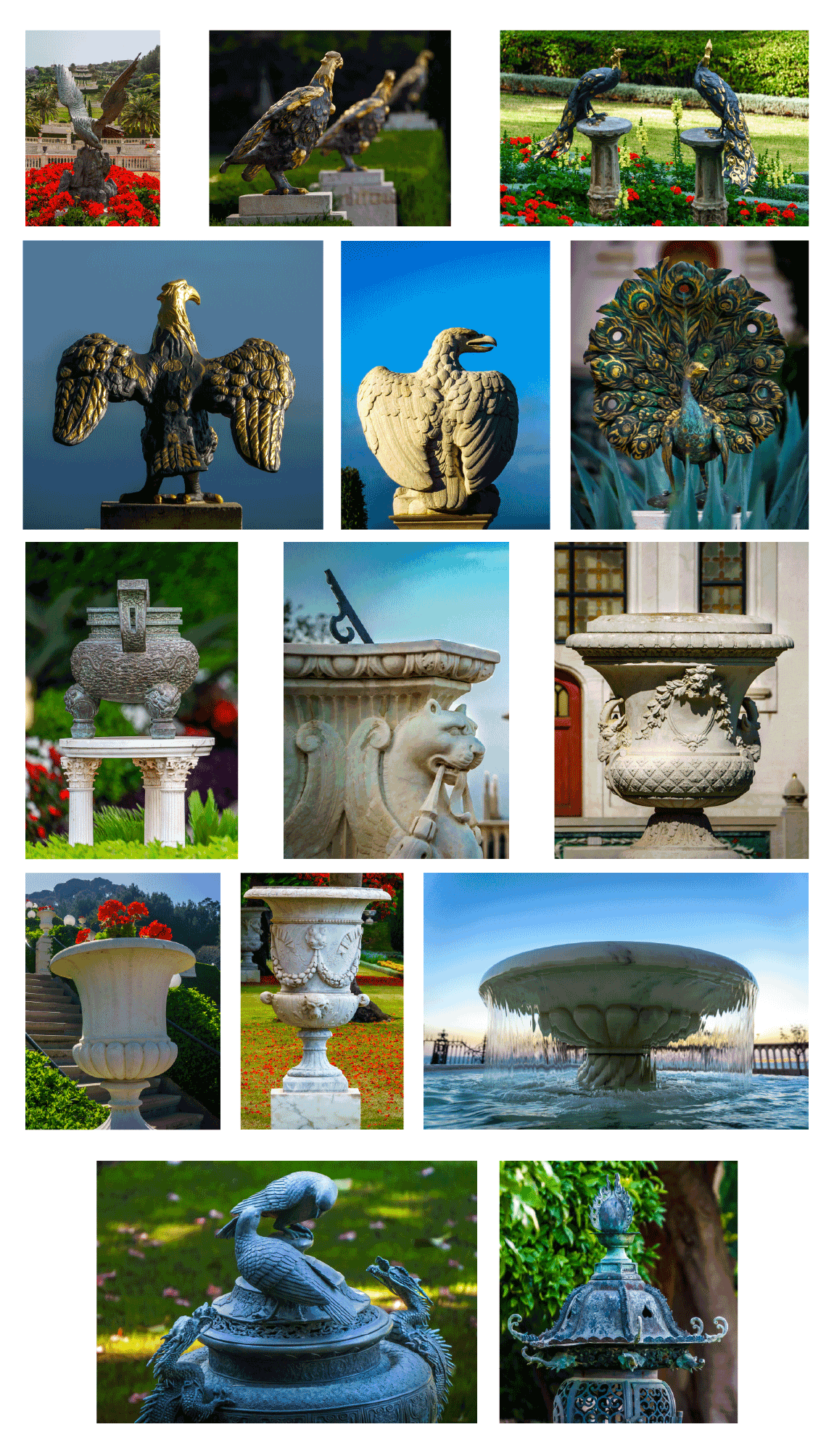

Before excavating, the Guardian had to do several things. First, he had to carefully uproot trees, flowers and hedges, which would be replanted as soon as construction permitted. Then, he had to remove the countless marble tiles paving the walkway of the Shrine, as well as enormous vases and pedestals,

The Guardian still had no proper excavating equipment, and the job was arduous. Once Mount Carmel had been excavated, the Guardian had to reinforce the face of the cut-away mountain-side with an almost vertical wall and tons and tons of rock had to be carted away.

Shoghi Effendi's drive and eagerness to complete the excavation for the foundation was a sure sign of his eagerness to begin construction on the masterpiece he had guided William Sutherland Maxwell to create.

Materials needed to build the arcade included these large corner stones. © United States National Bahá'í Archives, used with permission.

Carved marble and granite columns were not the only materials needed for the construction of the first crown of the superstructure. The Guardian needed hundreds of tons of structural steel at regular frequencies, and the steel became harder and harder to find.

The Guardian also needed lumber for the scaffolding built around the project in order for the workers to be able to work, and other items included shuttering— planks or strips of wood temporarily used to contain concrete as it hardens—nails, iron wire, wrought-iron gates and fences, iron posts, electric wiring and cable, insulators, iron and zinc pipe, chain lifts, various types of tools, anti-rust varnish, paint and, in due time, lamp-posts, lamp-holders, switches, metal chains, moldings, marble pedestals, marble steps and tiles—a different marble from the Chiampo kind—door and window frames, plain and stained-glass window panes, marble adhesive, electric globes and lamps, and many, many, many other items.

At one point, Ugo Giachery felt that only the power of divine assistance was able to help them not only find what the Guardian needed, but buy it, pay for it, ship it, and have it arrive safely in Haifa. In 10 years of working on several building projects with Shoghi Effendi, Ugo Giachery never once had to tell him he couldn’t find something the Guardian wanted.

25 years later when writing his memoirs in 1973, Ugo Giachery was still wondering how it had been possible to obtain those materials. The only thing he was certain of, was that of the power that emanated from the World Center, from the Shrine of the Báb, and from the Guardian. Speaking of these miraculous events, Ugo Giachery said:

I knew that if the Guardian asked for something, nine-tenths of the problem had been solved. His daily prayers and supplications at the Shrines would solicit the intervention of heavenly assistance that would remove every difficulty, near or remote.

Ugo Giachery never once told the Guardian of the problems he was facing in trying to obtain materials, he never once told him of the insurmountable obstacles right in front of him, never shared his pain and heartache in trying to obtain export licenses, never told him about the hours of work each day, week after week, month after month, year after year, for nearly five years. He never told the Guardian about going from Ministry to Ministry, from committee to committee, from individual to individual, all scattered around different parts of Rome, waiting for hours in waiting rooms, filling out forms, paying dues in advance.

But the Guardian knew.

3 July 1948: Guardian announces the start of the work on the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb

3 July 1948: Guardian announces the start of the work on the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb

Background photograph: Lead vases, gilded peacocks, crushed red tile paths, lights, marble stairs and cypress trees all play a part in beautifying the gardens around the Tomb ol the Bab on Mt. Carmel, Haifa, Israel. Source: The Bahá'í World Volume 11, page 37.

On 3 July 1948, Shoghi Effendi announced to William Sutherland Maxwell after dinner:

Well, the historic decision to commence work on the Shrine has been taken at 10:15 (p.m.) today!

The superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb was—at that time—the largest prefabricated building ever to be shipped out of Europe. The Guardian’s timing was perfect: his was the only monumental project after World War II.

Over a period of 19 months, the crews throughout Italy dug out 800 tons of granite and marble for the entire arcade—24 columns, 8 pilasters, bases and threshold stones—which were cut, sculpted and polished to perfection by some of the best stonemasons in the country.

Once all parts of the arcade were finished, they were assembled by section, numbered like an immense building-sized puzzle, and carefully packed in huge packing crates. They sent the cut and polished granite and marble to Haifa with packing lists for every single crate, and an overall map of where each stone fit into the entire building.

A stunning photograph by Chad Mauger of the Rose Baveno columns, perfectly framed to highlight their characteristic charm. Source: Chad Mauger’s Flickr page, © Chad Mauger, used with permission.

Some months after 5 May 1948,when the contracts for the Rose Baveno granite were signed and before 1 October 1948, when they were shipped, Ugo Giachery had an almost spiritual experience seeing the pink columns for the first time in all their glory:

Never shall I forget the astounding impression I received when, in the marble working-yard, I beheld the Rose Baveno columns, twenty-four of them, lined up like giant soldiers on parade, glimmering in the sunlight of a clear autumn morning in the Italian Alps!

Just a few months ago, those same shiny, polished, finished columns had been huge rough blocks of granite, just quarried from the bosom of the mountain, and now they were standing there, after having been manually shaped with sledgehammers:

Now, like well-cut precious gems carved out from shapeless stones, the slender, towering shafts were proclaiming the perfection of their form and brilliancy to my incredulous eyes.

Ugo Giachery felt a flood of joy, filling his entire being, just imagining how happy the Guardian would be to see his columns raised up along the colonnade, 8 on each of the four sides of the building, and the joy of all the pilgrims hereafter, who would circumambulate under the shade of those precious columns. Ugo Giachery had spent months with William Sutherland Maxwell’s drawings, but when he actually saw the columns in front of him, it was a deeply moving experience.

Modern view of the port of Livorno, Italy, where the ships loaded with materials for the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb left from. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The materials were ready to be shipped.

On 1 October 1948, Shoghi Effendi sent a telegram to Ugo Giachery:

Delighted splendid progress increasingly admire your indefatigable labours. owing international situation urge start shipment material completed. Cable date shipment. Deepest love. Shoghi Rabbání.

Shoghi Effendi sent another telegram a few days after this one asking for the name of the ship.

In another sign that they were operating in a post-war world, Ugo Giachery was having a hard time finding a captain willing to sail from Italy to Israel, because many of them thought the seas around Haifa had been rigged with mines, set to detonate.

A view of the port of Haifa from the Shrine of the Báb showing docked ships such as the many ships which sailed from Italy to the Holy Land carrying hundreds of tons of precious building materials for the superstructure. © United States National Bahá'í Archives, used with permission.

Almost by miracle, Ugo Giachery found a ship that was available with a captain that was willing: the S.S. Norte, which could arrive in the Holy Land by the end of November 1948.

In Haifa, everyone was getting ready, quickly.

Ben Weeden was making arrangements to bring the materials, after they were unloaded at the port midway up Mount Carmel, and workers made space in the gardens to store the shipping crates, Arrangements were made for clearing customs, and Ugo Giachery sent word that a second ship was also arriving at the same time, the S.S. Campidoglio.

Things were moving fast.

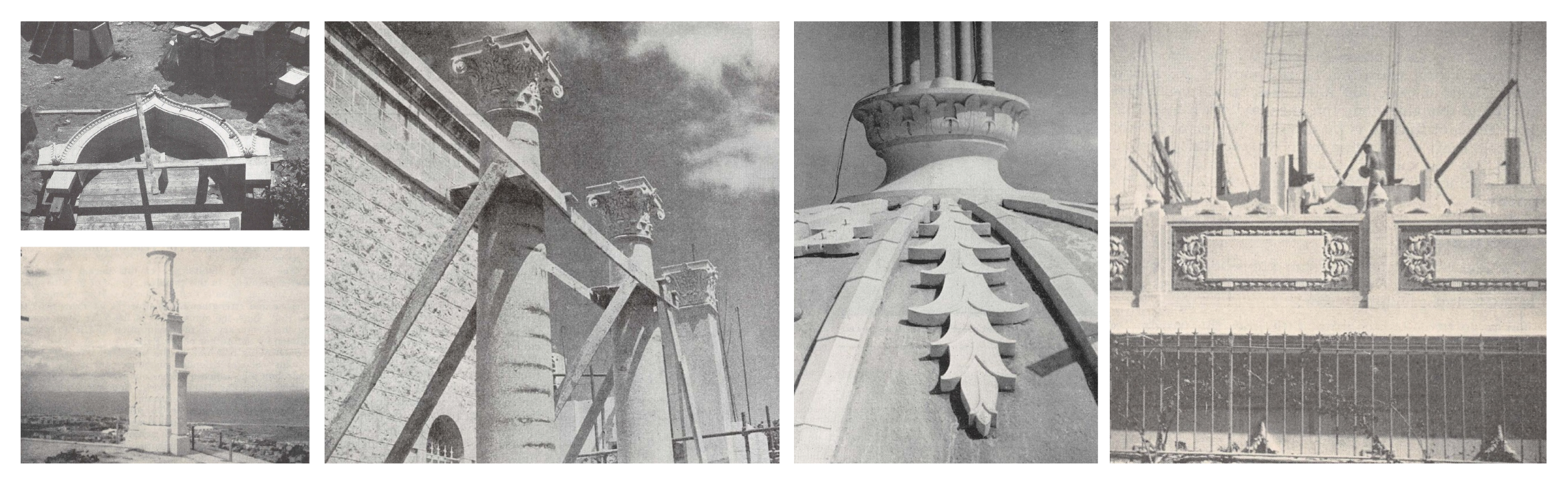

Arches, finials, columns, panels, carved decorations for the dome, just a fraction of the materials sent from Italy to Haifa.

After Shoghi Effendi’s enthusiastic approval, Ugo Giachery began making long preparations for packing and shipping all the material for the construction of the arcade, preparing gigantic, sturdy wooden crates and transporting the giant columns to Livorno, a port on the west coast of Italy.

In Livorno, dockers loaded the S.S. Norte with its precious and very heavy cargo: 72 wooden crates filled with 112 tons of columns, pilasters, socles (plinths) and threshold stones and the S.S. Campidoglio was carrying 40 tons of cut, carved and polished marble and granite. These were just the first 152 tons of a total of 800 that would eventually make its way to the Holy Land from Italy in the lifetime of the project.

The captains were worried their cargo might be confiscated, but they set off, and on 16 November, Ugo Giachery sent a momentous cable to Shoghi Effendi that the ships had departed two days prior:

First shipment granite, stone Holy Báb’s shrine left Leghorn [Livorno] Sunday November 14th steamship Norte due Haifa twenty-third entrusting safety beloved guardian’s prayer assistance blessed perfection ever-present master’s guiding hand. loving devotion. Ugo Giachery.

The S.S. Norte and Campidoglio sailed a few days apart to the Holy Land.

These stunning Rose Baveno granite columns arrived as is from Italy, as with all the rest of the elements of the superstructure, making the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb the largest prefabricated building ever shipped out of Italy. © United States National Bahá'í Archives, used with permission.

The S.S. Norte arrived on 28 November 1948—the anniversary of the Ascension of 'Abdu'l-Bahá. Five days later, on 3 December 1948, the S.S. Campidoglio arrived.

The largest prefabricated building ever to be shipped out of Europe had safely arrived at port. All of the carved marble and granite was carefully unloaded and stored, a huge endeavor.

On 13 December 1948, the Guardian was able to announce the arrival of the first shipment of ready-made materials in Haifa to the Bahá'ís of the United States:

Convey to believers the joyful news of the safe delivery on Mt. Carmel of a consignment of thirty-two granite monolith columns, part of the initial shipment of material ordered for construction of the arcade of the Báb’s sepulcher, designed to envelop and preserve the sacred previous structure reared by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá.

Building was about to begin.

The story continues on 9 July 1950, with the completion of the arcade.

Colonel Alberto Bufalini was the one who dealt personally with William Sutherland Maxwell and later with Ugo Giachery in the work of constructing the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb and the International Bahá'í Archives.

Through his devotion to the projects, and his hard work, he had helped make Bahá'í history.

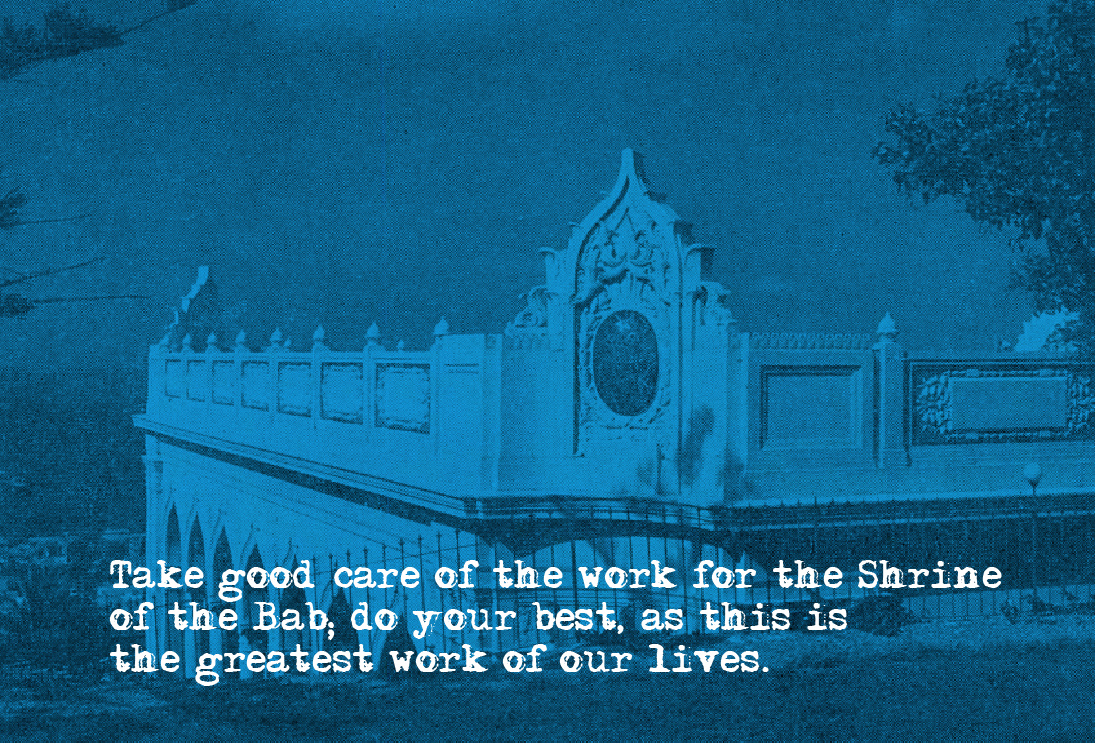

On his deathbed, on 10 September 1949, he told his two sons, speaking about the Shrine of the Báb:

Take good care of the work for the Shrine of the Báb; do your best, as this is the greatest work of our lives.

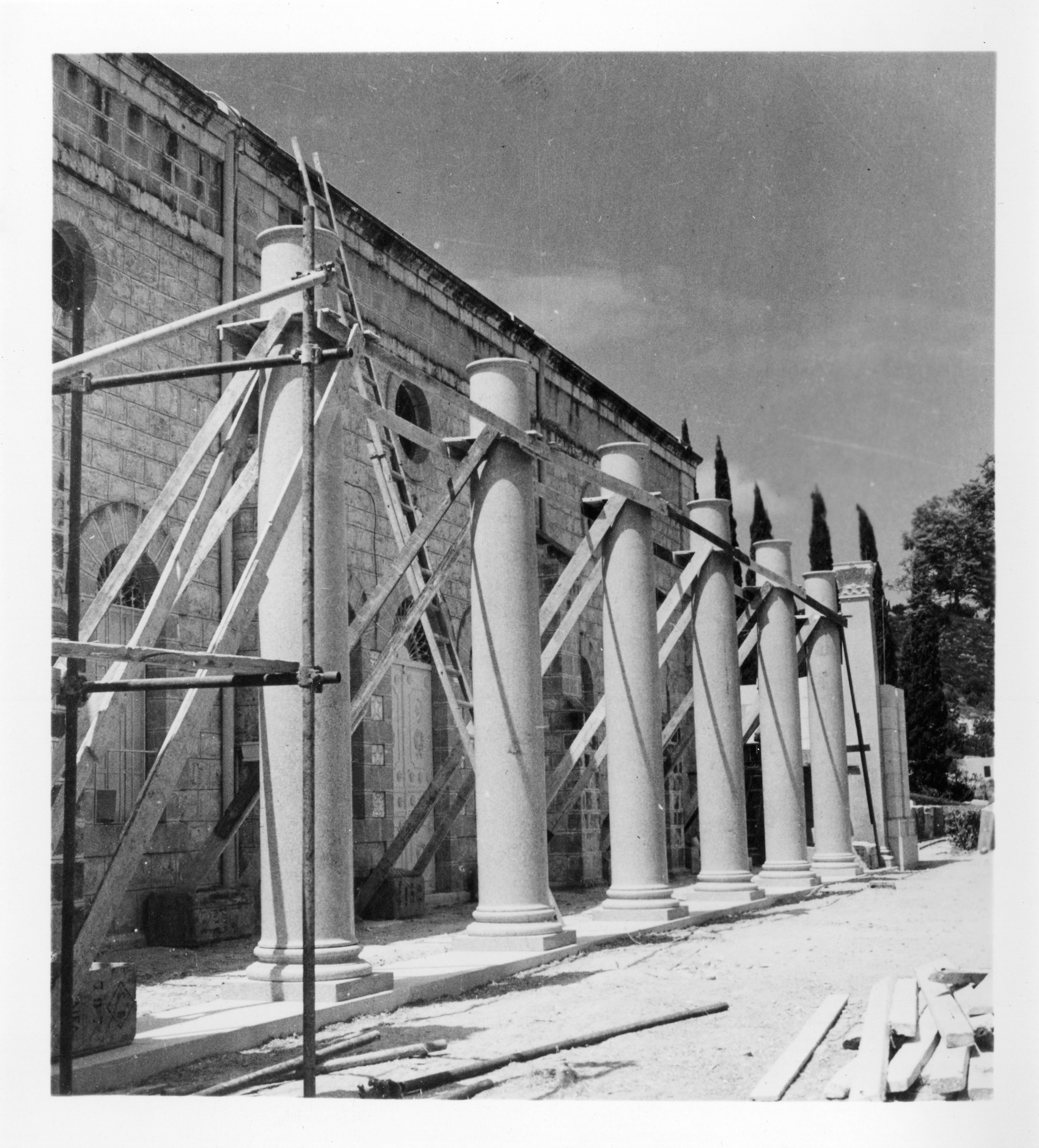

The colonnade under construction in 1950. Source: Bahá'í World News Service.

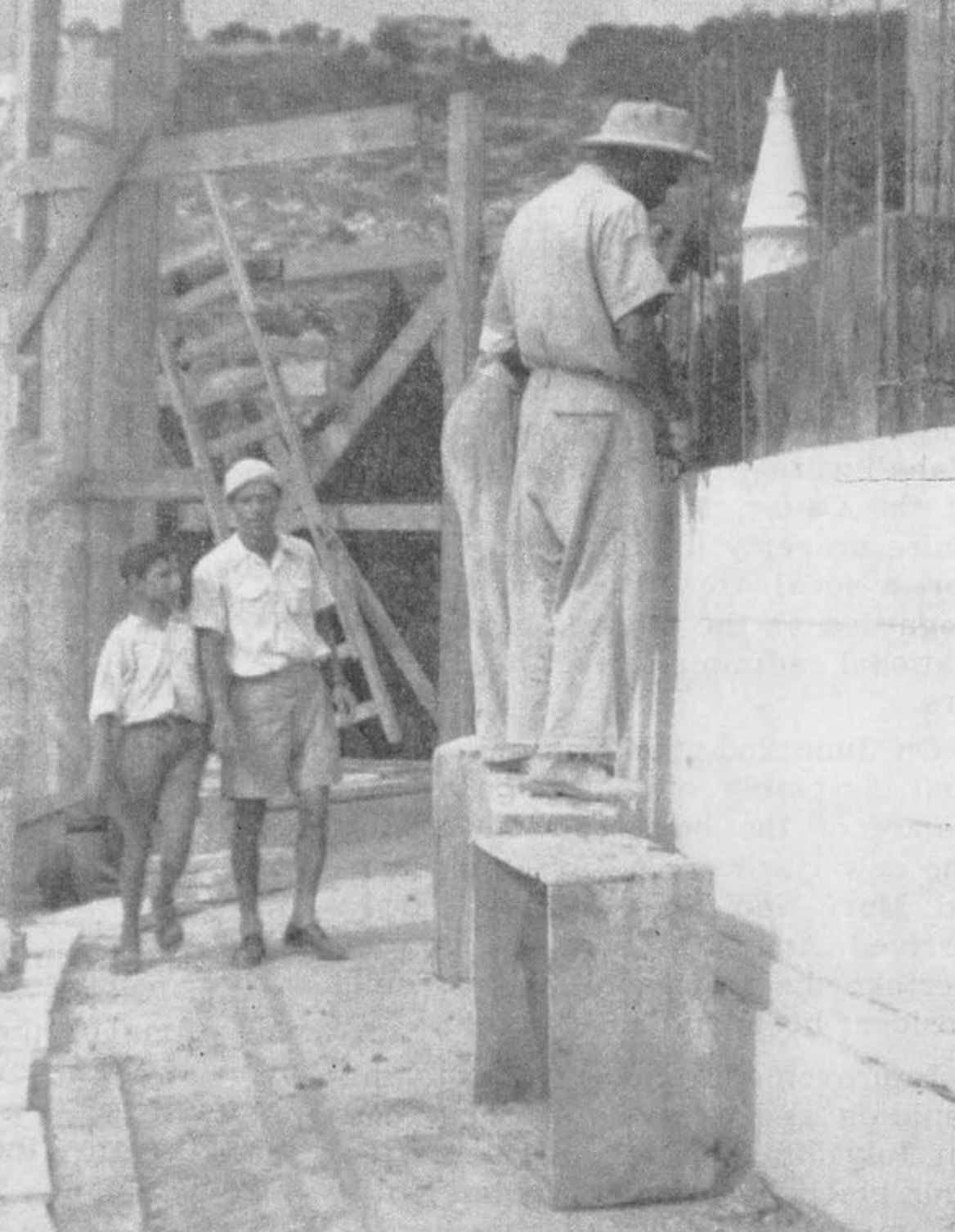

On 14 March 1949, workers installed the first threshold stone for the arcade, 50 years after 'Abdu'l-Bahá had placed the foundation stone of the original Shrine on 14 March 1899. Construction of the arcade of the shrine of the Báb had begun.

Soon, the three remaining threshold stones had been placed, but the construction was paused until the spring of 1949 because of large expenses for the House of Worship in the United States, and a severe drought in Italy which impacted the work of the stonemasons.

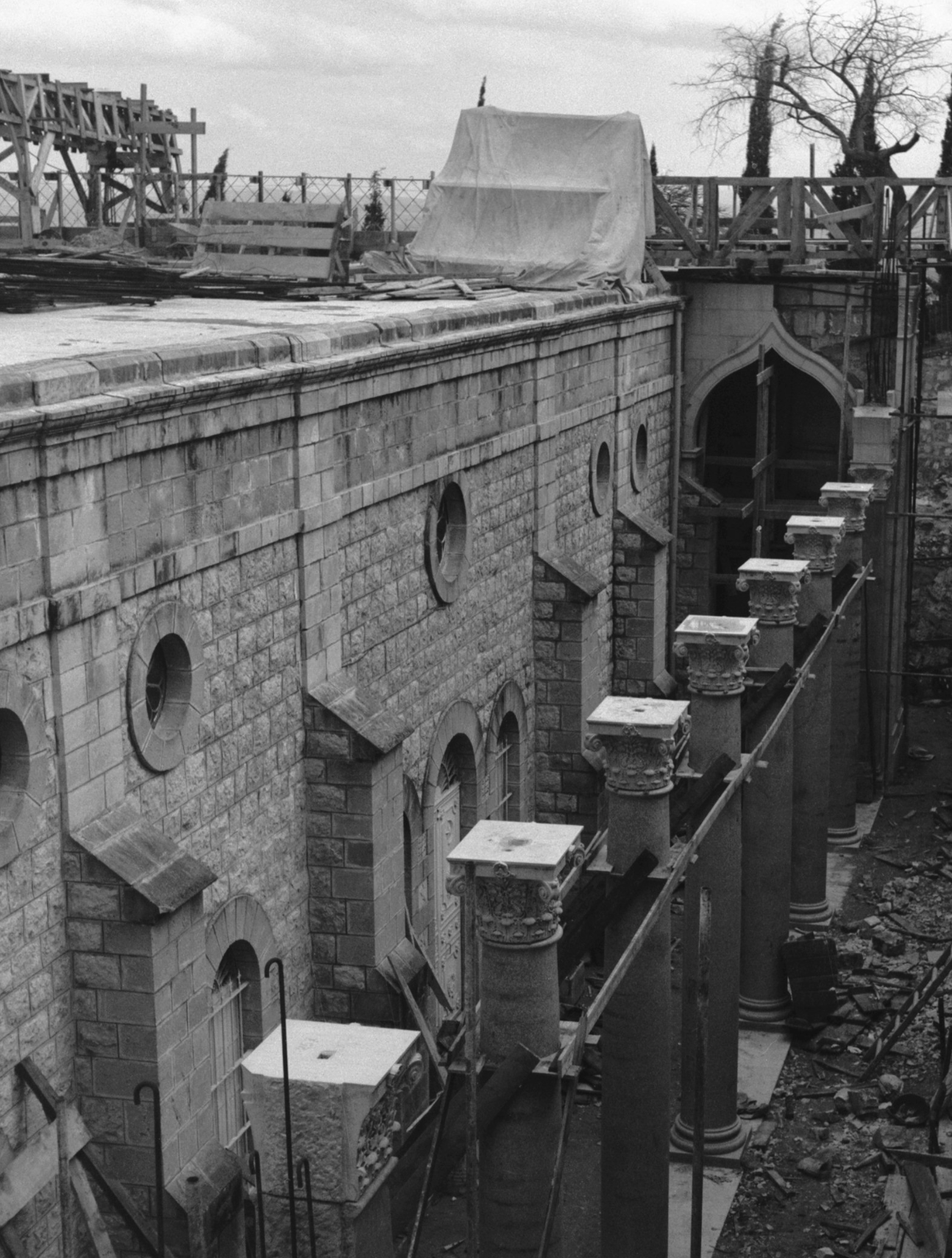

On 7 August 1949, the Guardian informed the Bahá'í world that construction had begun on three corners of the arcade of the Shrine and six granite pilasters—corner columns—were about to be raised. Shortly after this, 12 of the distinctive Rose Baveno granite columns of the arcade were raised.

By 13 November 1949, the Guardian had completed construction on three corners of the arcade, leaving the cornice and the roof as the next step.

The Guardian’s deadline was fast approaching for the completion of the Arcade: it was only a year away. As work progressed on the arcade itself in the Holy Land, Dr. Giachery sent the Guardian samples for the 27 mosaic floral panels in hues of blue and green with red flowered accents, which he approved.

The colonnade under construction in 1950. Source: Bahá'í World News Service.

The construction stage of the colonnade where we can see two rows of 8 Rose Baveno columns in place. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

This photograph shows the northeast corner of the Shrine of the Báb with a home-made gantry being used to raise a Rose Baveno granite pilaster. © United States National Bahá'í Archives, used with permission.

This photograph clearly shows the colonnade on the north side of the Shrine beginning to look compete. Source: Bahaimedia.

Workmen building the platform to construct the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb above the original Shrine built by 'Abdu'l-Bahá. Source: Bahá'í World News Service.

Two receipts issued by Shoghi Effendi and signed in his own hand for contributions to the building projects on Mount Carmel, one from 1926 and one from 1951. Source: Bahaimedia.

Soon, the columns began rising, one by one, along the arcade, and everything began to take shape. The last 200 tons of stone arrived in Haifa, and in the middle of a hectic construction schedule to a very tight deadline, the Guardian still found time to acknowledge a contribution for the Shrine of the Báb from a very small New Zealand community of Whanganui for the construction of the Shrine, his secretary writing on his behalf:

The Guardian was deeply touched to receive your contribution for the Shrine of the Báb, sent in your letter dated September 28 [1949], and for which I am enclosing a receipt.

Photographs of marble and mosaic panels, including the panels of the Greatest Name, some in black and white from the 1950s, and some in color taken in the last 10 years. All photographs Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

The mosaics were so fragile, and the panels on which they were installed were so intricate and delicate, that shipping them was a problem. The rest of the marble and granite had been shipped in sturdy crates of local alpine fir, like the columns, but when Ugo Giachery traveled to Pietrasanta and saw the panels, he realized a single packing crate would not be enough and decided that the first crate should be encased in a second packing crate for protection.

The Guardian approved the extra expense, and Ugo Giachery purchased the needed lumber, and within days, the 200 tons of marble and mosaics for the parapet where shipped to the Holy Land. The ship loaded with the parapet marble and mosaics made a stop at a port to load bags of black soot, used to make paints, and which they placed on top of the precious marble crates.

The sea journey to Haifa was rough, and the bags of black soot had split open all over the Guardian’s precious crates, but Ugo Giachery’s genius idea of double-boxing the marble prevented the soot from damaging the marble panels.

The panels and their intricate mosaics arrived in Haifa on 25 February 1950.

A graceful arch is first carefully tried out on the ground before being built into Arcade of the Shrine of the Bab. Source: The Bahá'í World Volume 11, page 73.

This photograph shows the scaffolding for the placement of the arches of the arcade, the step before the first crown formed by the parapet. © United States National Bahá'í Archives, used with permission.

Two ornamental stone carving detail designs on the outer face of the arcade on the Shrine of the Báb, including a close up of the detail of the arches of the arcade. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

Top photograph: Ringstone symbol on the Shrine of the Báb in the corners of the parapet. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023. Bottom photograph: Exquisite mosaics decorating the parapet in colors specifically chosen by Shoghi Effendi from samples sent to him. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

The parapet panels of the arcade—the front vertical side of the arcade where the beautiful mosaics are—started arriving on 25 February 1950. Once a crate was opened, and the packing removed, everyone was lost in admiration. The Italian craftsmen had outdone themselves, and reproduced to perfection William Sutherland Maxwell’s exquisite designs.

With these wonderful panels on hand the workmen went forward with added zest to prepare for the setting of them. Soon the day came when the first panel on the east side of the arcade was brought carefully into place and raised into position. At the end of the second day the other six panels were placed with the small pillars standing between. Not long after, the cover stones and the finials of the pillars were added thus completing the east side of the arcade.[ 625]

The parapet crowning the eastern façade of the Shrine of the Báb was completed on Naw-Rúz, 21 March 1950. The finely carved panels and the green-blue mosaics with red flecks over the graceful, soaring arches and the rose-colored columns were a sight to behold, beautiful and majestic, and the work on the entire arcade was finished when the last stone was placed at 3:30 PM on 29 May 1950. The arcade was almost complete.

By 17 June 1950, the gilded Greatest Name on a green mosaic background was in position, as well as the three ringstone symbols, on three corner panels.

Workers installing a single panel of the parapet. © United States National Bahá'í Archives, used with permission.

A photograph of the construction stage of the parapet above the colonnade in 1950. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

A stunning photograph of the completed arcade and parapet. Source: The Bahá'í World Volume 11, page 13.

On 7 July 1950, the Guardian announced to the Bahá'í world the completion of the arcade around the Shrine of the Báb on the eve of the centenary of the Báb’s martyrdom:

Announce to believers, through all National Assemblies, termination initial stage of construction of domed structure designed to embellish and preserve the Báb's sepulcher on Mount Carmel…My soul is thrilled in contemplation of the rising edifice, the beauty of its design, the majesty of its proportions, the loveliness of its surroundings, the historic associations of the site it occupies, the sacredness of the Sanctuary it envelops, the transcendent holiness of the Treasure it enshrines.

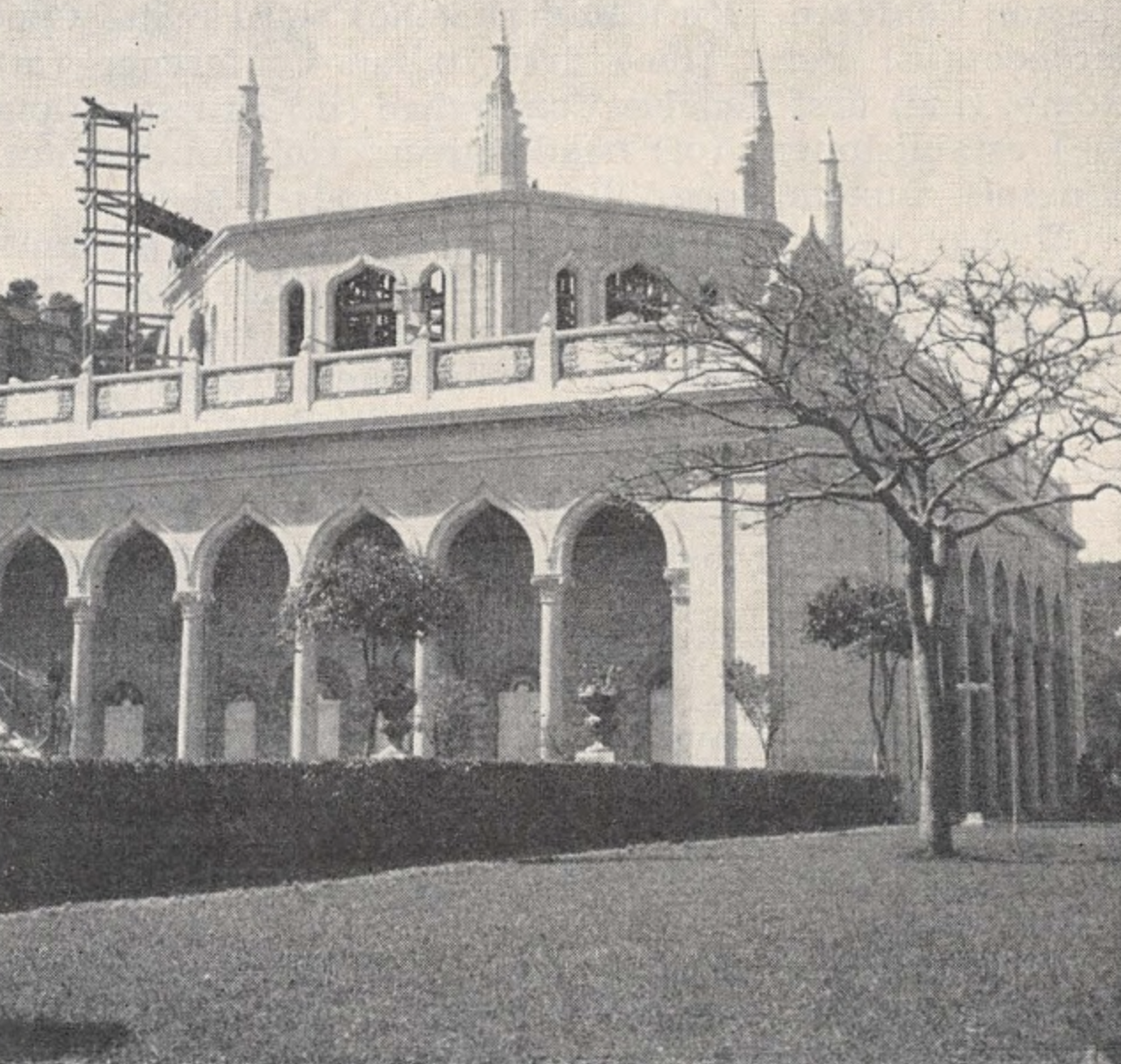

The Guardian would always refer to the parapet of the arcade as the “first crown of the Shrine.” In this beautiful message, the Guardian paid tribute to the Shrine’s “gifted architect, Sutherland Maxwell,” who was recovering in Switzerland of a serious illness, and announced the next step in the construction of the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb, the octagon, without delay.

The colonnade which was just completed, was an equilateral quadrangle, with 8 smoothy, shiny, perfect pink granite columns on each side, joined by graceful, arabesque arches in between them which connected the columns to the cornice, which then connected to the parapet. The parapet and the cornice together were what Shoghi Effendi considered the first crown of the Shrine of the Báb.

The cornice—the part between the parapet or the stone balustrade and the arcade above the columns—is a substantial vertical wall. The cornice is composed of 28 regular monolithic one-ton panels of flawless marble, 7 on each side of the shrine, and in between each panel is a vertical post topped with an ornament.

Inside each marble panel on the cornice is a green glass mosaic with scarlet flowers, which Shoghi Effendi described:

Green denotes the lineage of the Holy Bab, and scarlet signifies the colour of the blood shed by His martyrdom.

The parapet—the top part above the columns which the Guardian considered to be the first crown of the Shrine, was made of four walls that met—not at a straight angle—but in beautiful, ample intricately carved marble concave recess, in each of which was set, like a diamond on a ring, a gorgeous green blue mosaic in the shape of an oval shield with a gilded Greatest Name in the center.

The large central panel on the north side of the parapet, facing the sea, is a masterpiece of beauty, craftsmanship and intricate design. When the entire balustrade was completed, Shoghi Effendi announced this to the Bahá'í world, and referred to that central panel as “adorned with green mosaic with gilded Greatest Name, the fairest gem set in crown of arcade of Shrine.”

At the heart of the central part of this panel is a large disk like a shining midday sun, with white and golden rays, holding within a nine-pointed star of green marble a bronze fire-gilded Greatest Name in Arabic in bas-relief, visible from a distance. On either side of this panel, there is a letter B, carved with interspersed leaves and foliage in the acanthus motif. The left B is reversed and the right B is normal, so that they bookend the center design with the first letter of the Báb’s name.

Each of the four concave corners is flanked at each side by two pilasters of Chiampo marble, with bases and Corinthian capitals.

The story of the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb continues on 21 April 1952, with the story of the octagon.

A pristine photograph of the eastern side of the Shrine of the Báb, now enshrined in the graceful colonnade and its first crown, the parapet above the arches. This is the side of the edifice through which pilgrims will access the Shrines of the Báb and 'Abdu'l-Bahá. © United States National Bahá'í Archives, used with permission.

A rare site: A snow covered shrine in the winter of 1949/1950. Bottom photograph: Haifa covered in snow. Source: The Bahá'í World Volume 11, page 91.

In the winter of 1950, there was a historic snowfall in Israel. The snow event began in early January 1950 with a hailstorm in Jaffa and light snow in the mountains of the Upper Galilee and Jerusalem, then, on 27 January 1950, it began snowing in the mountains of Hebron and Jerusalem, but the snow soon melted after it had piled up.

A cold front swept through all of Israel, and snow began falling in the mountains of Samaria and in the west of the country. By February, it had snowed in Petah Tikva, Netanya, Rishon Lezion, the Sea of Galilee, the Negev and the Dead Sea.

On 28 January 1950, 15 centimeters of snow fell in Haifa, snowing the next day again, and covering the entire city in a blanket of snow. Haifa had magically turned white.