Written and illustrated by Violetta Zein

This part covers the life of Shoghi Effendi from the age of 49 in 1946 to the age of 54 in 1951.

Background image by Paul Blenkhorn on Unsplash.

The official inception of the Second Seven Year Plan, at the 1946 National Convention of the United States and Canada, with a message from the Guardian which opened with momentous epoch-making words:

Time ripe events pressing hosts on high sounding signal inauguration second Seven Year plan designed culminate first Centennial Year Nine marking mystic birth Bahá’u’lláh’s prophetic Mission Síyáh-Chál Tihrán.

In this long cable, the Guardian called on the American believers to arise and simultaneously follow through on the tasks begun in the first Seven Year Plan and launch new enterprises worldwide.

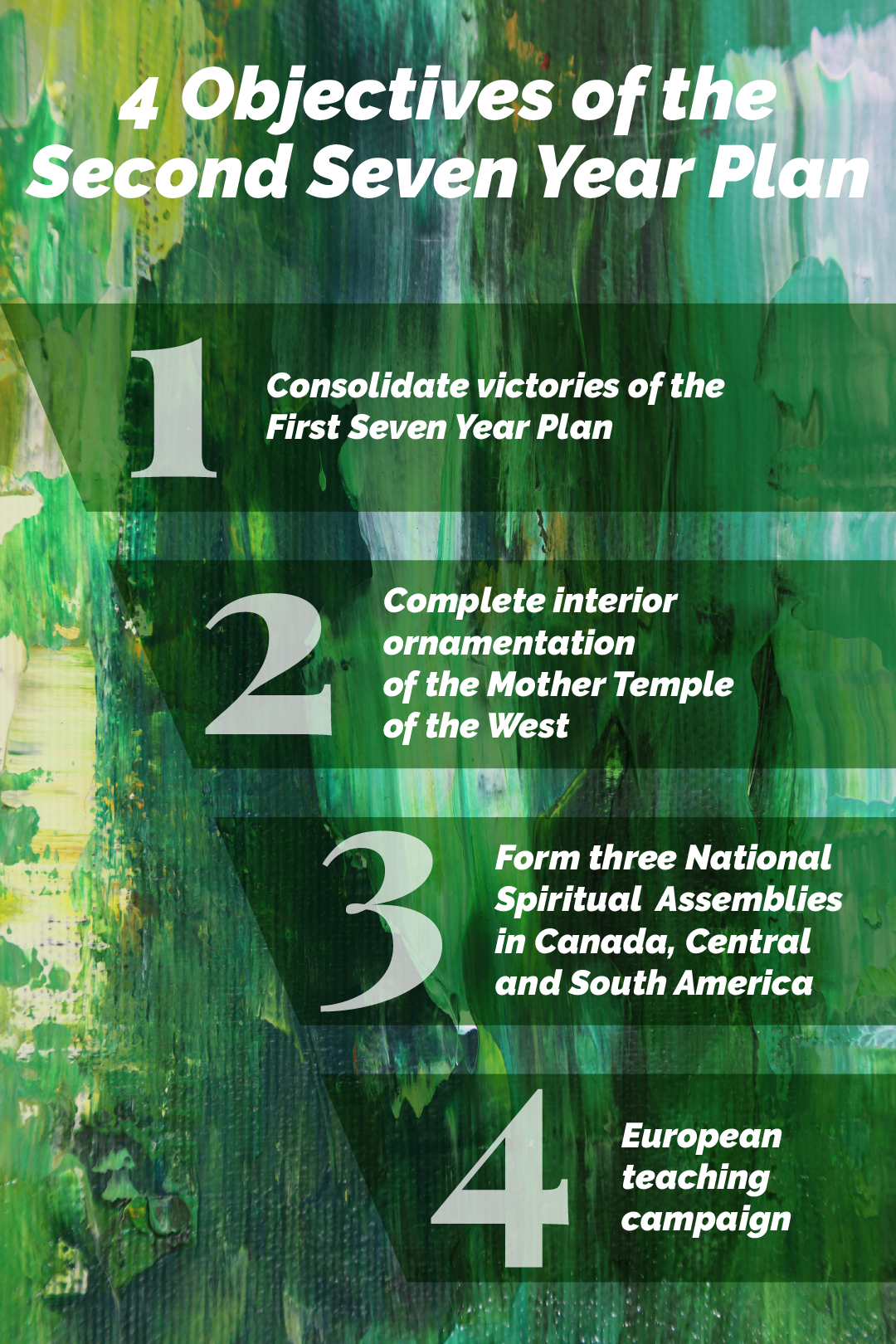

The Guardian set four objectives for the Second Seven Year Plan:

- The first objective was to consolidate the victories won in the expansion of the First Seven Year Plan throughout the American continent, and to proclaim the Faith to the masses.

- The second objective was to complete the interior ornamentation of the Mother Temple of the West by the 50th anniversary of its inception.

- The third objective was to form three National Spiritual Assemblies in Canada, Central and South America.

- The fourth objective was to initiate a systematic teaching campaign aimed at forming National Spiritual Assemblies in what Shoghi Effendi termed the “war-torn spiritually famished European continent.” This would later be called the European Campaign.

The Guardian closed this extraordinary message with a statement of such grandeur about the coming crusade, that all Bahá'ís who received it must have held their heads high from pride:

Pledging ten thousand dollars my initial contribution furtherance manifold purposes glorious Crusade surpassing every enterprise undertaken by followers faith Bahá’u’lláh course first Bahá’í century.

Ten thousand dollars in 1946 represent amount to $157,000 today.

The Second Seven Year Plan was to coincide with the second great Centenary of the Guardian’s ministry: the 100 years since “Year Nine,” the time fore-ordained by the Báb until Bahá'u'lláh received the Revelation from God in the Siyáh-Chál, in October 1952.

Background image by Laura Vinck on Unsplash.

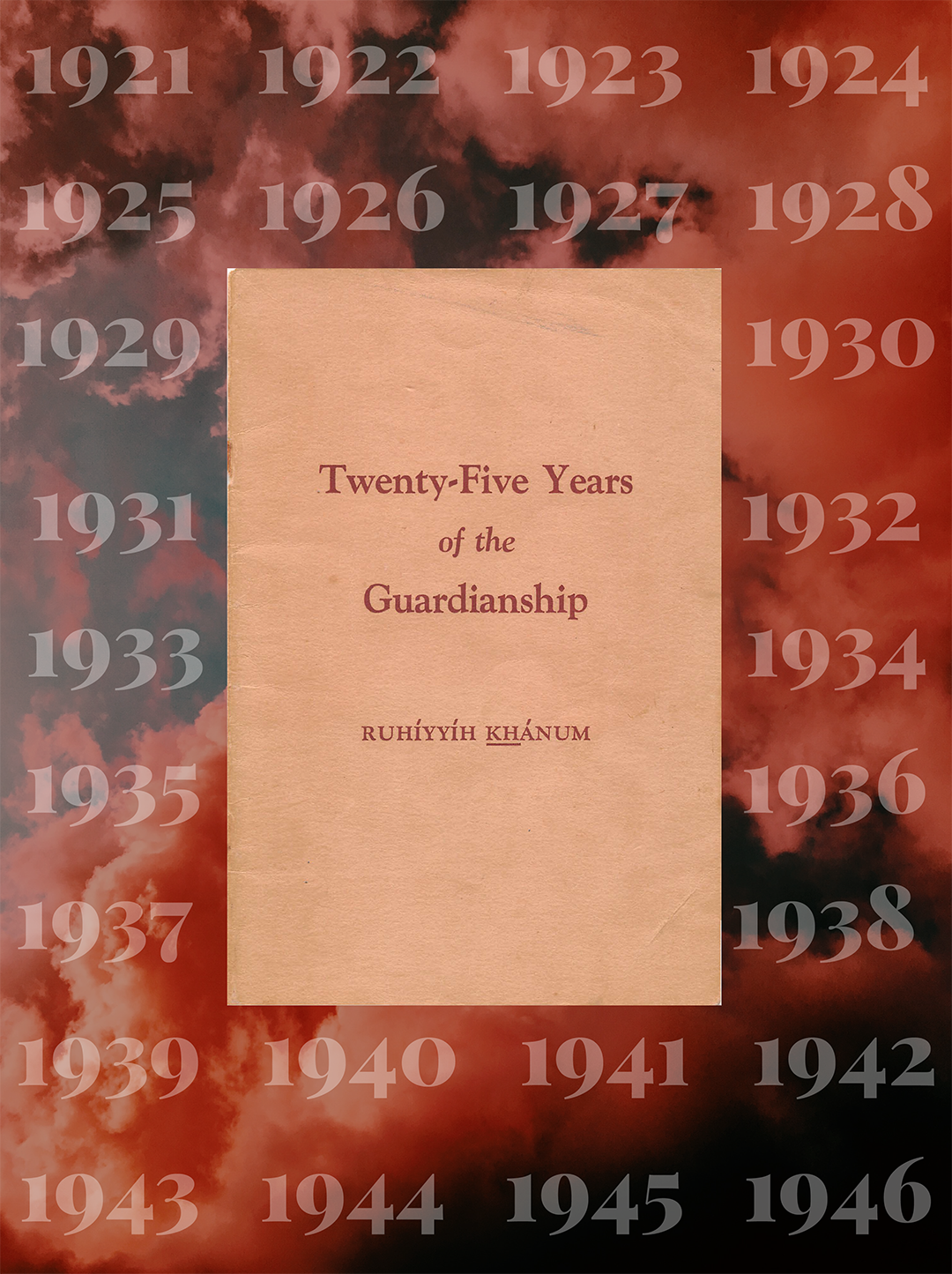

In November 1946, Amatu’l-Bahá Rúḥíyyih Khánum published a 27-page booklet called Twenty-Five Years of the Guardianship, a retrospective on the Guardian’s first quarter-century of ministry. This story will examine the entire structure of Rúḥíyyih Khánum’s marvelous essay.

It opens with the passing of 'Abdu'l-Bahá and the anguish and uncertainty of the grieving Bahá'í world who had just lost their beloved Master:

Twenty-five years ago the Bahá'í world was shaken by a great earthquake, 'Abdu'l-Bahá, the Center of the Covenant, the greatest Mystery of God, had suddenly passed away…

The next several paragraphs study 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s Will and Testament in detail:

['Abdu'l-Bahá] had given us the mighty Ark of His own Covenant, which we could enter into in peace secure.

This is how Shoghi Effendi, the Guardian saw the Bahá'í world as he began his ministry, conscious of the work of community-building which lay ahead:

[Shoghi Effendi] beheld a widely diversified, loosely organized community, scattered in various parts of the globe, and with members in about twenty countries. These people, loyal, devoted and sincere though they were, were still, to a great extent living in their parent religion's house, so to speak; there were Christian Bahá'ís, Jewish Bahá'ís, Muhammadan Bahá'ís and so on.

A snapshot of the early years of the Guardian’s ministry:

Shoghi Effendi immediately began to display a genius for organization, for the analysis of problems, for reducing a situation to its component parts and then giving a just and wise solution. He acted vigorously, with unflinching determination, and unbounded zeal.

At the start of his ministry, 'Abdu'l-Bahá had appointed himself three tasks: the establishment of the Faith in North America, the erection of the first Bahá'í House of Worship in ‘Ishqábád, and the construction of the Shrine of the Báb on Mount Carmel. Shoghi Effendi appointed himself two tasks:

{One] was to steer the believers all over the world into working through properly organized administrative channels…and the other was to see that year by year they became more emancipated from the bonds of the past.

Between 1923 and 1934, the Guardian succeeded in establishing six new National Spiritual Assemblies and the development of the Administrative Order was one of the priorities of his ministry, which he did for 16 years from 1921 to 1937, when he finally communicated to the Bahá'í world that they had matured enough to enter into a new developmental stage: he inaugurated the first Teaching Plan based on 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s The Dawn-Breakers, the First Seven Year Plan:

He told us, so to speak, that we were now trained enough to use our laboriously erected Administrative System for a great joint effort, an effort to carry into effect the first stages of the Divine Plan.

After the First Seven Year Plan followed the Second Seven Year Plan, and the achievements of the worldwide Bahá'ís were staggering: institutions, endowments, properties, legal recognition, summer schools, Bahá'í literature. The Guardian’s achievements in the Holy Land were stupendous. Rúḥíyyih Khánum lists them all over several paragraphs, devotes four paragraphs to listing the Covenant-breakers that attacked Shoghi Effendi, and lists all his translations, and major letters. In the penultimate paragraph, Rúḥíyyih Khánum has a beautiful phrase:

So we see that just as we Bahá'ís the world over are his responsibility, given to him by Almighty God, so is he our responsibility, likewise given us by Almighty God. Let us not take it lightly!

Gleneagles Hotel in Scotland. By Simon Ledingham, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons.

After their first trip to Scotland in 1945, Shoghi Effendi and Rúḥíyyih Khánum returned for a second visit, either in 1946 or 1947, and this time they had a car. Shoghi Effendi had told his wife:

I'm going to take you to the home of your ancestors.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum had always loved Scotland and considered herself Scottish, but didn’t really connect with her Scottish identity until she was 8 years old, in the home of an aunt and heard bagpipes for the first time, playing from a parade in the street below. The sound of the bagpipes went through little Mary Maxwell like a fire, and her father explained to her what had just happened:

It's because you're a Scot.

Her father, William Sutherland Maxwell, was Scottish through and through. Some of the family was from Aberdeen, on the eastern coast of Scotland, and his parents, Edward John Maxwell and Johan MacBean, had emigrated from Jedburgh, a small town in Southeastern Scotland to Canada in the 19th century, and he was born in Montreal on 14 November 1874. Rúḥíyyih Khánum’s ancestors were from three Scottish Clans—Clan Maxwell, Clan MacBean, and Clan Sutherland—but mainly came from Aberdeen and Jedburgh.

On this trip to Scotland, Shoghi Effendi and Rúḥíyyih Khánum had a car and they visited several cities: Loch Lomond, Gleneagles, Stirling, Edinburgh, Glasgow and Aberdeen, as well as several stops on the way during the longer journeys. Rúḥíyyih Khánum spoke of a memorable evening in Gleneagles:

After dinner in the foyer of the hotel, people were dancing Scottish reels in the kilts and Shoghi Effendi thought it was beautiful. He thought it was lovely music and very, very graceful dancing. And I can remember now how much he enjoyed that.

A masterful and life-size silvered bronze Okimono—a small decorative Japanese carving—of an eagle on a root wood base, the exact same type of sculpture that Shoghi Effendi purchased on his first trip to Scotland with Rúḥíyyih Khánum. The story of this Japanese eagle sculpture continues in Part XXI: The Passing of the Guardian, as the inspiration of the design for the monument of Shoghi Effendi’s resting place in London. Source: Source: © Kevin Page, Oriental Art, all rights reserved, used with permission.

Shoghi Effendi often went to England to buy furnishings for the Holy Places in Haifa and Bahjí, and while they were visiting Scotland, they walked into several shops. One of the shops was owned by a woman, and she had a beautiful Japanese bronze eagle, poised on a wood cliff, for sale.

Shoghi Effendi did not like many things, he had very, very specific tastes, but the things he loved, he loved with passion, and Shoghi Effendi fell in love with that eagle.

He bought the sculpture and had it shipped back to Haifa where he placed it on a table near his bed, in his bedroom which also doubled as his office.

Shoghi Effendi’s eagle is now on display in the International Bahá'í Archives.

It was this eagle that Rúḥíyyih Khánum took inspiration from when designing the golden eagle that crowns Shoghi Effendi’s resting place in London.

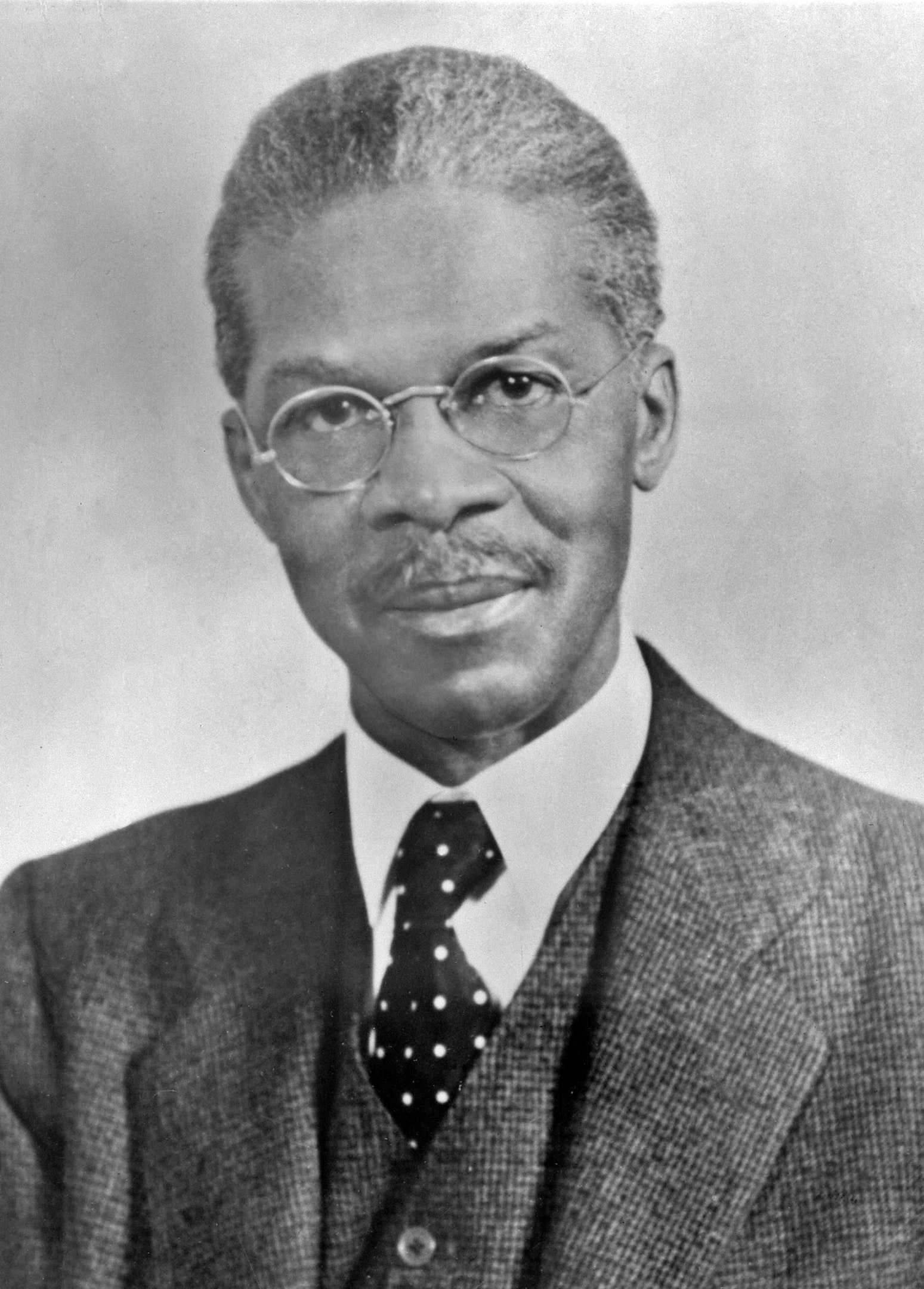

Amelia Collins. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

Amelia Collins had become a Bahá'í in the time of 'Abdu'l-Bahá and came to the Holy Land, seeking the presence of the Guardian in 1923, with her husband Tom, who was not a Bahá'í. During this pilgrimage, the Guardian gave Amelia a message to read. The next day, the Guardian asked her:

What did you think of the papers I gave you to read?

Amelia answered truthfully:

What shall I say? I did not understand anything!

That same day, the 26-year-old Guardian explained the contents of the message to Amelia as they walked together, began to educate Amelia in the core administrative principles of the Faith with immense patience loving-kindness.

When she returned to America, the Convention received the same message the Guardian had deepened Amelia on in Haifa, and she was called to the front to explain it.

Thus started a collaboration between Amelia Collins and Shoghi Effendi that would last from the second year of his Guardianship to his thirty-sixth. Amelia would never leave his side, and she would never let him down.

Whatever the Guardian asked, she gave, and what he did not ask, she gave also. Their unique collaboration is obvious in the letters Shoghi Effendi wrote to her throughout her life.

In 1937, Amelia Collins’ beloved husband Tom died suddenly. Shoghi Effendi sent a touching condolence message:

Greatly distressed sudden passing beloved husband. Heart overflowing tenderest sympathy

Amelia rendered such great services to Shoghi Effendi that he was moved to write her these lines:

How pleased the Beloved must be: how proud He must feel of your truly great achievements! The soul of dear Mr. Collins must exult and rejoice in the Abba Kingdom. Persevere and be happy.

Over the years, it was clear that Shoghi Effendi was preparing, training, forming Amelia Collins to attain the rank of Hand of the Cause. For example, in 1926, the Guardian wrote Amelia:

Your steadfastness in service, your selflessness and devotion to the work you are engaged in greatly encourage me and inspire me in my work. Your many services, past and present, will ever be remembered with praise, gladness, and gratitude. Continue in your magnificent endeavours for the propagation of the Bahá'í Faith and remember always that in me you have a grateful, loving and admiring brother who will never cease to pray for you from the bottom of his heart.

During the first 30 years of his Guardianship, Shoghi Effendi only appointed Hands of the Cause posthumously. The first contingent of living Hands of the Cause he appointed was on 24 December 1951.

Except for one living Hand of the Cause.

The Guardian elevated Amelia Collins to the rank of Hand of the Cause in a private cable dated 22 November 1946:

Your magnificent international services exemplary devotion and now this signal service impel me inform you your elevation rank Hand Cause Bahá'u'lláh. You are first be told this honour in lifetime. As to time announcement leave it my discretion.

The entire world would learn about her appointment five years later, when the Guardian informed the world about the first contingent of Hands of the Cause.

Amelia Collins would serve on the International Bahá'í Council, and she also was an active teacher of the Faith, but another aspect of her service to the Guardian were her immensely generous contributions, very often directly offered to Shoghi Effendi.

She never mentioned these.

Salt, Jordan, where Bahá'ís from ‘Adasiyyíh moved to after leaving the Holy Land. Photograph by Adeeb Atwan, available under Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 on Wikimedia Commons.

When the state of Israel was established in 1948, its boundary with Jordan passed very close to the village of ‘Adasiyyah, making it very difficult to continue to live there and many Baha’is moved away, but Shoghi Effendi had begun advising the Bahá'ís to leave ‘Adasiyyíh.

In 1946, some Bahá'ís relocated to other parts of the Holy Land and Maan, Jordan, where they worked with Bedouin tribes, and in 1947 other ‘Adasiyyíh farmers settled in Salt, in southern Jordan.

Between 1951 and 1953, strife in Israel intensified, and so did the restrictions on the Bahá'í community of ‘Adasiyyíh. At that time, the Guardian instructed a number of the Bahá'ís to return to Iran.

Over the years, more ‘Adasiyyíh farmers left the village and pioneered to neighboring countries and other parts of the world, but a number of them stayed in the village, despite the fact the land had been sold to new owners. They leased their farms and worked the land, as Shoghi Effendi’s had instructed.

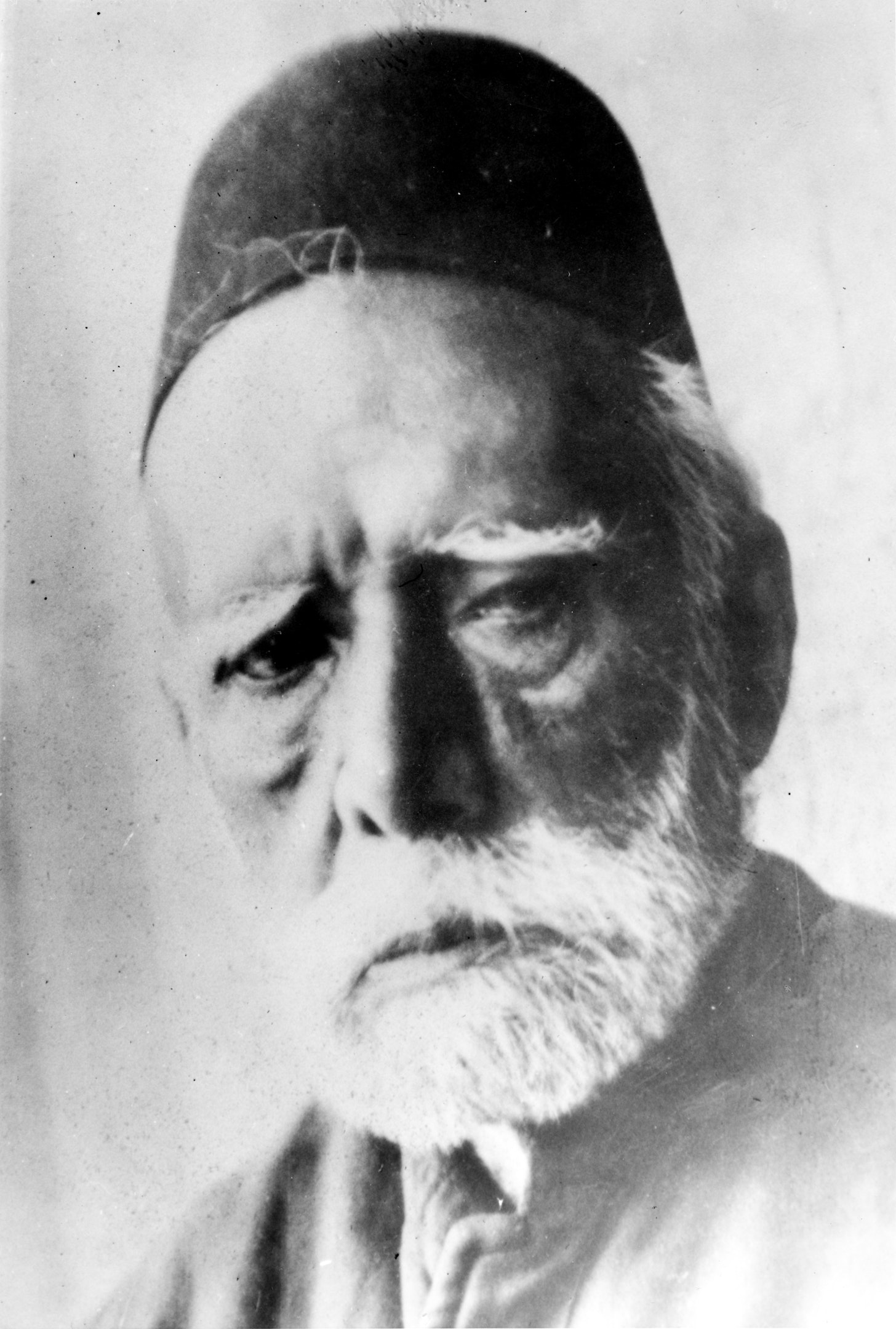

Muḥammad Taqíy-i-Isfáhaní (died in 1946). Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

Muḥammad Taqíy-i-Isfáhaní was born in the village of Sidih, near Iṣfahán, around 1860. Muḥammad Taqíy-i-Isfáhaní became a Bahá'í young, and at the age of 15 in 1875, he was imprisoned for his beliefs. The martyrdom of the King and the Beloved of Martyrs four years later, in 1879, shocked him to his core, particularly because they were murdered by a mob instigated by the Leader of Friday Prayers who did not want to pay them a substantial debt he owed them.

After the Martyrdom of the King and the Beloved of Martyrs, Muḥammad Taqíy-i-Isfáhaní left Persia for Egypt, stopping for pilgrimage in 'Akká on the way for a 13-day pilgrimage. He met 'Abdu'l-Bahá one day, and entered into the presence of Bahá'u'lláh the next. In all, Muḥammad Taqíy-i-Isfáhaní completed four pilgrimages to the Holy Land during the lifetime of Bahá'u'lláh, who had encouraged him to settle in Egypt and pursue a career there.

Muḥammad Taqíy-i-Isfáhaní established himself in Egypt and his home became a center for Bahá'í activity.

After the Ascension of Bahá’u’lláh in 1892, Muḥammad Taqíy-i-Isfáhaní served 'Abdu'l-Bahá faithfully, particularly during 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s visits to Egypt in 1910. 1911, 1912, and 1913, in the course of His Journeys to the West. He ran errands for 'Abdu'l-Bahá and for the visiting pilgrims waiting to enter into His presence.

During the ministry of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, Muḥammad Taqíy-i-Isfáhaní also went to Haifa several times. His last pilgrimage was in February 1919.

As soon as Muḥammad Taqíy-i-Isfáhaní heard of 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s Ascension on 28 November 1921, he immediately set off for Haifa and stayed there for 40 days. When the Will and Testament of 'Abdu'l-Bahá was read, Muḥammad Taqíy-i-Isfáhaní immediately supported Shoghi Effendi as Guardian.

In 1924, when the first National Spiritual Assembly of Egypt and the Sudan was formed, Muḥammad Taqíy-i-Isfáhaní was elected as one of the members, and subsequently appointed to its Publishing Committee. As a member of that committee, Muḥammad Taqíy-i-Isfáhaní translated Bahá'u'lláh’s Kitáb-i-Íqán and 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s Some Answered Questions into Arabic.

An Egyptian Covenant-breaker named Fa’iq tried to create a sect of the Bahá'í Faith in Egypt in 1925, and Muḥammad Taqíy-i-Isfáhaní was among the most stalwart defenders of the Faith at that time.

Muḥammad Taqíy-i-Isfáhaní served on the National Spiritual Assembly of Egypt and the Sudan for at least ten years. His last years were deeply heartbreaking as both his son and his wife passed away before him.

On 13 December 1946, Muḥammad Taqíy-i-Isfáhaní passed away, and Shoghi Effendi elevated him to the rank of Hand of the Cause as a posthumous honor:

Hearts grief stricken passing beloved, outstanding, steadfast promoter Faith, Muḥammad Taqíy-i-Isfáhaní. Long record his magnificent, exemplary services imperishable deserves rank Hands Cause God. Advise hold befitting memorial gatherings Egyptian centers. Contribution two hundred pounds construction grave.

On 15 January 1947, ten years before the passing of the Guardian, the National Spiritual Assembly of the United States and Canada published a compilation of his letters under the title: Messages to America: selected Letters and Cablegrams Addressed to the Bahá'ís of North America, 1932-1946.

This compilation does not include the major letters of Shoghi Effendi during this period: The World Order of Bahá’u’lláh, The Goal of a New World Order, The Golden Age of the Cause of Bahá’u’lláh, America and the Most Great Peace, The Dispensation of Bahá’u’lláh, The Unfoldment of World Civilization, The Advent of Divine Justice or Promised Day Is Come.

This Decisive Hour brings together 165 chronologically-organized letters and cables the Guardian addressed to the National Spiritual Assembly of the United States and Canada, to the annual Conventions and to the Bahá'í community of North America from June 21, 1932, to December 3, 1946—one of the most tumultuous periods in world history.

These communications represent an enduring source of guidance, inspiration, and capacity-building from Shoghi Effendi and bear witness to the Faith’s ability to build a new spiritual order on the wreckage of the old word order.

These letters from Shoghi Effendi trace the history of the American Bahá'í community through his Plans and announcements: the First Seven Year Plan, the exterior ornamentation of the House of Worship, the development of the Administrative Order in North America, the expansion of the Faith in Central and South America, the devastating state of the world with the approach to and consummation of World War II, and the inauguration of the Second Seven Year Plan.

In this volume, the Guardian also makes many announcements the publication of the Dawn-Breakers, his marriage to Amatu’l-Bahá Rúḥíyyih Khánum, the transfer of the remains of Ásíyih Khánum and Mírzá Mihdí to Mount Carmel, preparations for the centenary of the Declaration of the Báb, and the publication of God Passes By.

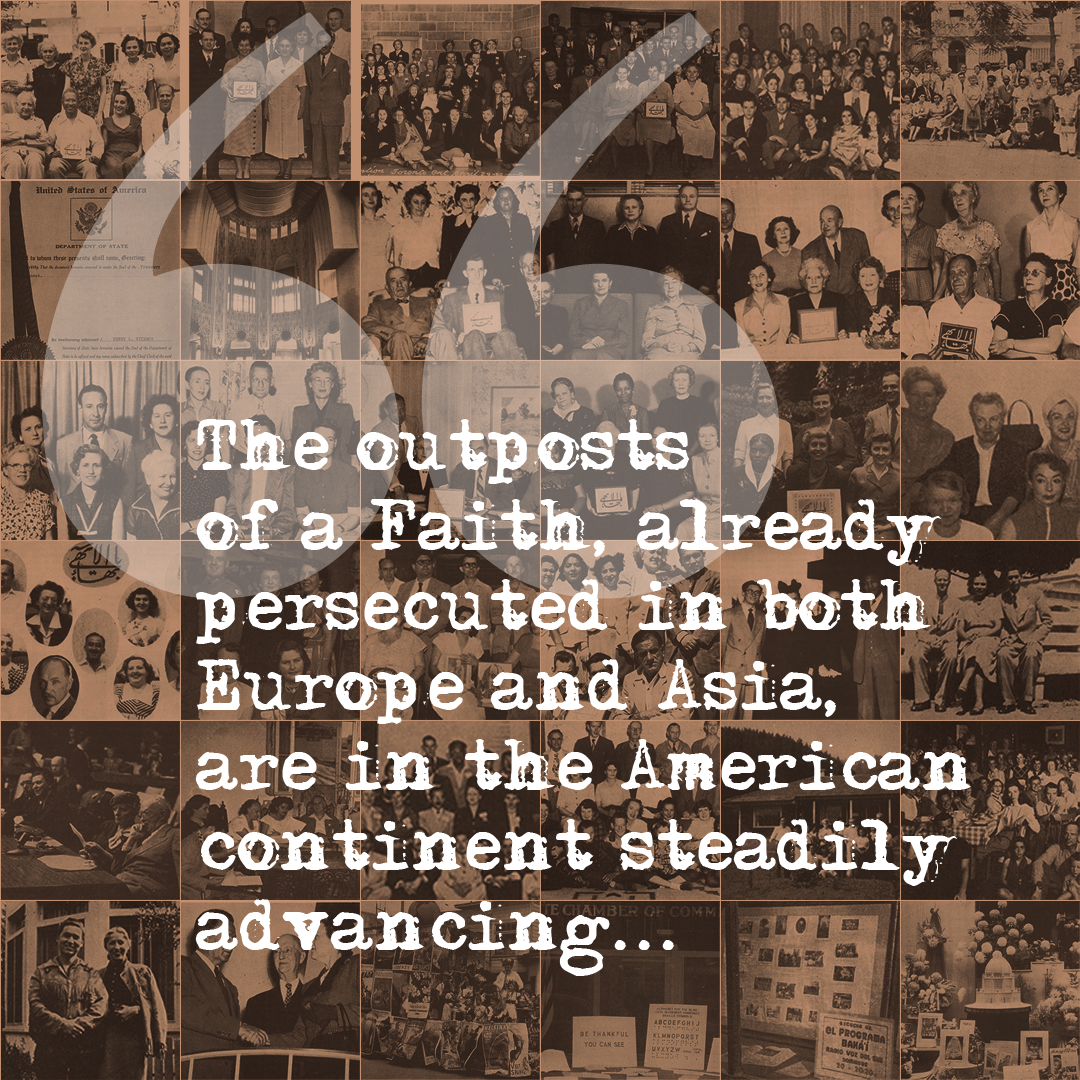

36 photos of the many activities and communities in North, Central, and South America from The Bahá'í World Volume 12.

Here is a marvelous excerpt from This Decisive Hour, a letter written by Shoghi Effendi on 25 November 1937, and titled All Should Arise, in which the Guardian speaks about the extraordinary qualities of the American Bahá'ís:

As I lift up my gaze beyond the strain and stresses which a struggling Faith must necessarily experience, and view the wider scene which the indomitable will of the American Bahá’í community is steadily unfolding, I cannot but marvel at the range which the driving force of their ceaseless labors has acquired and the heights which the sublimity of their faith has attained. The outposts of a Faith, already persecuted in both Europe and Asia, are in the American continent steadily advancing, the visible symbols of its undoubted sovereignty are receiving fresh luster every day and its manifold institutions are driving their roots deeper and deeper into its soil. Blest and honored as none among its sister communities has been in recent years, preserved through the inscrutable dispensations of Divine Providence for a destiny which no mind can as yet imagine, such a community cannot for a moment afford to be content with or rest on the laurels it has so deservedly won. It must go on, continually go on, exploring fresh fields, scaling nobler heights, laying firmer foundations, shedding added splendor and achieving further renown in the service and for the glory of the Cause of Bahá’u’lláh. The Seven Year Plan, which it has sponsored and with which its destiny is so closely interwoven, must at all costs be prosecuted with increasing force and added consecration. All should arise and participate. Upon the measure of such a participation will no doubt depend the welfare and progress of those distant communities which are now battling for their emancipation. To such a priceless privilege the inheritors of the shining grace of Bahá’u’lláh cannot surely be indifferent. The American believers must gird up the loins of endeavor and step into the arena of service with such heroism as shall astound the entire Bahá’í world. Let them be assured that my prayers will continue to be offered on their behalf.

Gladys Weeden in her later years. Source: Bahaimedia.

Gladys Anderson, a friend of Rúḥíyyih Khánum’s was the first American Bahá'í to be called to Haifa after World War II. She arrived on 30 March 1947 and in a very sensitive portrait she paints of the Guardian, she touches on many different facets of his wonderful personality from his friendliness to his bearing, his utter devotion to the Faith, his sense of humor:

My first impression was of his warm, loving smile and handclasp, making me fell instantly at ease...In the course of these interviews, I was to become increasingly conscious of his many great qualities—his nobility, dignity, fire and enthusiasm—his ability to run the scale from sparkling humour to deep outrage, but always, always putting the Bahá'í Faith ahead of everything...

All those who worked closely with Shoghi Effendi and listened to his guidance, learned a new sense of perfection and attention to detail. Gladys also gives a sense of what it was like to work for Shoghi Effendi, who was a very precise, methodical leader, and who outlined the responsibilities of his staff in clear terms, so that they would know exactly what to do in every situation:

In his practical, logical manner, Shoghi Effendi made me feel both a welcome guest and a needed helper, he outlined some of my duties which started the very next day! His advice, given me on that initial visit, was to overshadow all my efforts on his behalf; he said he wanted me to follow his instructions explicitly, if I was unsuccessful, or ran into difficulties, to report to him precisely and he would give me a new plan of action...

Shoghi Effendi was deeply generous in dinner time conversations, he would include everyone in the messages he received, the plans he was developing, with an infectious energy, as Gladys brilliantly describes what it was like to be seated at that table with the Guardian:

Sparkling with excitement and new plans, he would produce messages and letters from his pockets, oftentimes pushing his dinner plate away untouched, calling for paper and pencil and thrill us all with his new ideas and hopes for the Bahá'ís to carry out.

Column detail of the Seat of the Universal House of Justice. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

An extremely important point made by ‘Alí Nakhjávání in his paper The Ten Year Crusade, is that careful observation reveals that throughout the Ten Year Crusade the Guardian was diligently preparing the world for the election of the Universal House of Justice, an objective that had been at the forefront of his ministry for 30 years, and for which he had spent the first three decades of his Guardianship meticulously, systematically building a robust Administrative Order—in particular the National Spiritual Assemblies, the ”pillars” of the Universal House of Justice.

Shoghi Effendi clearly and repeatedly stated in his letters to the Bahá'ís and to Bahá'í institutions that the second epoch of the Formative Age would come to an end with the Centenary of the Declaration of Bahá'u'lláh in 1963.

As early as 5 June 1947—the very year when North America’s Seven Year Plan was launched—the Guardian wrote to the American Bahá'ís that the current epoch of the Formative Age would witness the consummation of the laboriously-built Administrative Order, and the unfoldment of 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s Divine Plan. He also firmly stated that it would witness the election of the Universal House of Justice:

During this Formative Age of the Faith, and in the course of present and succeeding epochs, the last and crowning stage in the erection of the framework of the Administrative Order of the Faith of Bahá’u’lláh—the election of the Universal House of Justice—will have been completed.

Shoghi Effendi stated that 1964 was the year prophesied in the Book of Daniel which would witness the universal spread and triumph of the Faith of Bahá'u'lláh, an outcome that 'Abdu'l-Bahá had confirmed.

Alfred Emil Fredrik Sandström, the chairman United Nations Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP). Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The Guardian wrote two statements addressed to secular government authorities during his ministry. The first was written in the 1930s, possibly for the British authorities in Palestine and was published as “The Bahá'í Faith: A Summary” after the introduction of the 1955 edition of the compilation The World Order of Bahá'u'lláh.

Shoghi Effendi wrote his second statement describing the aims and principles of the Bahá'í on 14 July 1947, in response to a request made by Alfred Emil Fredrik Sandström, the chairman United Nations Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP), four months before the United Nations General Assembly would adopt the resolution to partition Palestine on 29 November 1947.

The Guardian’s statement opens with a stunning description of the Bahá'í Faith:

The Revelation proclaimed by Bahá’u’lláh, His followers believe, is divine in origin, all embracing in scope, broad in its outlook, scientific in its method, humanitarian in its principles and dynamic in the influence it exerts on the hearts and minds of men.

Mr. ‘Alí Nakhjávání studied this statement of Shoghi Effendi extensively—the entire statement is available in the reference section—and he has isolated several fascinating statements made by the Guardian regarding the Bahá'í Faith:

- This letter is the only place in Shoghi Effendi’s body of work where he describes that the Faith is “scientific in its method”;

- In the same opening statement, Shoghi Effendi emphasizes that religious truth is not absolute;

- Shoghi Effendi states in no uncertain terms that the final stage of human evolution—the oneness of mankind—is not only necessary and inevitable, but gradually approaching;

- Shoghi Effendi describes the social and material teachings of the Bahá'í Faith as non-essential characteristics compared to its spiritual teachings;

- He uncompromisingly describes the station of Bahá'u'lláh as “the Promised One in the end of time,” and the advent of the “Day of Judgment”;

- Shoghi Effendi summarizes the aims of Bahá'u'lláh as fulfillment of all past religious dispensations and reconciliation of all beliefs in modern society;

- Shoghi Effendi describes the duty of an individual’s independent investigation of truth as the primary duty of every Bahá'í;

- Shoghi Effendi describes in detail the Bahá'í Administrative Order;

- He refers to the Bahá'í Faith as supernatural, supranational, entirely apolitical, non-partisan, and diametrically opposed to any and all prejudice—racial, class or national;

- Another fascinating point Shoghi Effendi makes in his description of the Bahá'í Faith is the Faith’s systematic dedication to the overriding welfare of the whole of mankind, and the Bahá'ís’ passionate dedication to this truth, over and above any particular personal, regional, or national interest.

At the end of this statement to UNSCOP, Shoghi Effendi quotes tributes to the Bahá'í Faith by prominent world figures such as Queen Marie of Romania, Leo Tolstoy, Referend T.K. Cheney, and the Master of Balliol, Professor Benjamin Jowett, among others.

Shoghi Effendi sent the letter the next day, 15 July 1947.

Four months after Shoghi Effendi’s letter to Justice Sandström, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the resolution to partition Palestine on 29 November 1947, and the United Kingdom announced the termination of its Mandate for Palestine, which became effective on 15 May 1948.

This letter was of such importance that it was published three months later in October 1947, under the title The Faith of Bahá’u’lláh: A World Religion.

Left: Marion Holley. Source: Wikimedia Commons. Right: Sylvie Ioas, the wife of future Hand of the Cause Leroy Ioas. Source: Bahaimedia. Background image: Participants at the 25 April 1945 United Nations conference in San Francisco.

The United Nations—replacing the League of Nations—was established after World War II with the aim of preventing future world wars.

On 25 April 1945, 50 nations met in San Francisco, California for a conference and started drafting the UN Charter. Two Bahá'ís were present at the birth of the United Nations—special envoys of the National Spiritual Assembly—Marion Holley and Sylvie Ioas.

The United Nations’ charter took effect on 24 October 1945, when the UN began operations. As soon as it became apparent that the United Nations would allow non-governmental organizations to send representatives to various conferences, the Guardian immediately began working towards obtaining this status, which would mean full recognition of the Faith’s position in history, on equal footing with all other world religions.

The National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá'ís of the United States and Canada applied for the status of non-governmental organization. They included a Bahá'í Declaration of Human Obligations and Rights in their application, as well as a Bahá'í Statement on the Rights of Women.

On 18 May 1947, the United Nations Office of Public Information recognized the United States and Canadian Bahá'í communities as a national non-governmental organization with observer status. A Bahá'í United Nations Committee was appointed and a Bahá'í observer attended United Nations sessions, but this role was limited in scope.

A little less than a year later, on 18 Apr 1948, nine National Spiritual Assemblies were collectively recognized as an International NGO under the title “Bahá'í International Community” for the purpose of maintaining a relationship with the United Nations.

The Guardian attached a great deal of importance to this tie uniting the Bahá'í International community with the United Nations—what Rúḥíyyih Khánum calls “the greatest international instrument ever forged in human history”—and called it:

An important step forward in the struggle of our beloved Faith to receive in the eyes of the world its just due, and be recognized as an independent World Religion. Indeed, this step should have a favourable reaction on the progress of the Cause everywhere, especially in those parts of the world where it is still persecuted, belittled, or scorned, particularly in the East.

One of the Guardian’s 27 objectives of the Ten Year Crusade was the “Reinforcement of the ties binding the Bahá'í World Community to the United Nations.”

Background image: Palestine refugees (British Mandate of Palestine - 1948). "Making their way from Galilee in October-November 1948. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

With the creation of the State of Israel, thousands of Arabs left former Palestine. One of the Guardian’s neighbors, an Arab family, asked a Bahá'í every day:

Is Shoghi Effendi leaving?

The family told this Bahá'í that when Shoghi Effendi left, they would leave too. Shoghi Effendi’s Arab neighbors told each other:

When you see Shoghi Effendi leave, grab your coat, lock the door and follow him!

On 27 April 1948, a few weeks before the end of the British Mandate, one of Shoghi Effendi’s neighbors told a Bahá'í:

If don't tell me Shoghi Effendi is planning to go, if he does, you are responsible for my life.

Like 'Abdu'l-Bahá before him, Shoghi Effendi had a well-earned reputation in Haifa, and the local inhabitants—even if they showed no interest for the Bahá'í Faith—respected him deeply.

A 1948 Buick as a symbolic illustration of Shoghi Effendi’s car, a gift from Roy Wilhelm, as no photographs of the Guardian’s car could be found. Source: © Classic Promenade, all rights reserved, used with permission.

On 4 May 1948, the Guardian’s Buick was stolen. It had been a very recent gift from Roy Wilhelm, after Shoghi Effendi had spent years moving around in taxis during the war, due to lack of spare parts.

Shoghi Effendi was calmer than everyone and only said:

How it will rejoice my enemies!

The Bahá'ís filed reports with several police stations in Haifa, but then, a strange thing happened. Rúḥíyyih Khánum spotted a hand lotion in a beauty parlor that she had several times tried to purchase, and she almost kept walking, but entered anyway. The owner of the shop knew Rúḥíyyih Khánum’s father, William Sutherland Maxwell, very well, and enquired after him, and Rúḥíyyih Khánum, in turn, asked after the shop owner’s elderly father. She almost didn’t say anything about the stolen car, but then, after paying for her items, she left without them. She felt so foolish that she apologized, saying:

I am very upset because our car has just been stolen!

The shop owner had just seen Rúḥíyyih Khánum and Gladys Weeden drive by in a Buick with American license plates the day before and replied, surprised:

But I saw your car today at about 2:15 in the new Business Center! And I was surprised because I wondered how you could sell such a beautiful new car!

He saw people driving the Buick and that it was just around the corner from the Savoy Hotel but he asked that Rúḥíyyih Khánum not mention his name as a witness. Rúḥíyyih Khánum explained that leaving his name out would not help them recover the car, so the man relented and agreed to be a witness.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum and Gladys returned to the police station and reported what they had just learned. Some time later, the Hadar police station called and said:

Your car has been located and you will get it back tomorrow so don't worry.

At 11 AM on 4 May 1948, Rúḥíyyih Khánum and Shoghi Effendi received a call that the car was ready to be picked up at the Hadar police station.

Digital painting of an imagined car shootout during the 1940s.

Shoghi Effendi had the long-standing practice of visiting Mount Carmel every day. He supervised the gardens and the progress of any work being undertaken, he visited the Shrines, and he returned home before dark.

The only times Shoghi Effendi was prevented from going about his usual tasks was when a curfew had been imposed.

One day, the Guardian was nearly involved in cross-fire.

Many Arabs had left the Holy Land when the British Mandate ended and the state of Israel was formed, and this included the Guardian’s Arab chauffeur. An American Bahá'í, Gladys Weeden, had arrived in Haifa in 1947 to serve the Guardian, and would stay for several years. She took over as Shoghi Effendi’s chauffeur, and was driving to the Shrines.

Suddenly, behind them, a car began shooting at the car in front of it, which overtook the Guardian’s car, placing him in the line of fire.

Eventually the shooters also overtook Shoghi Effendi’s car, and they went on to wage their private war, but for a moment, the Guardian had been involved in a shootout!

These years were deeply stressful for Rúḥíyyih Khánum, worrying not only about her Guardian but her husband. One day, on 22 February 1948, Shoghi Effendi was late in returning from the Shrine. The road was closed and so he was on foot, walking down the mountain. She was filled with anxiety but utterly powerless, and had to simply trust in Bahá'u'lláh to protect the Guardian.

In those years, there was shooting every night, sometimes even all night long, and they began to sleep through it, unless it was a bomb.

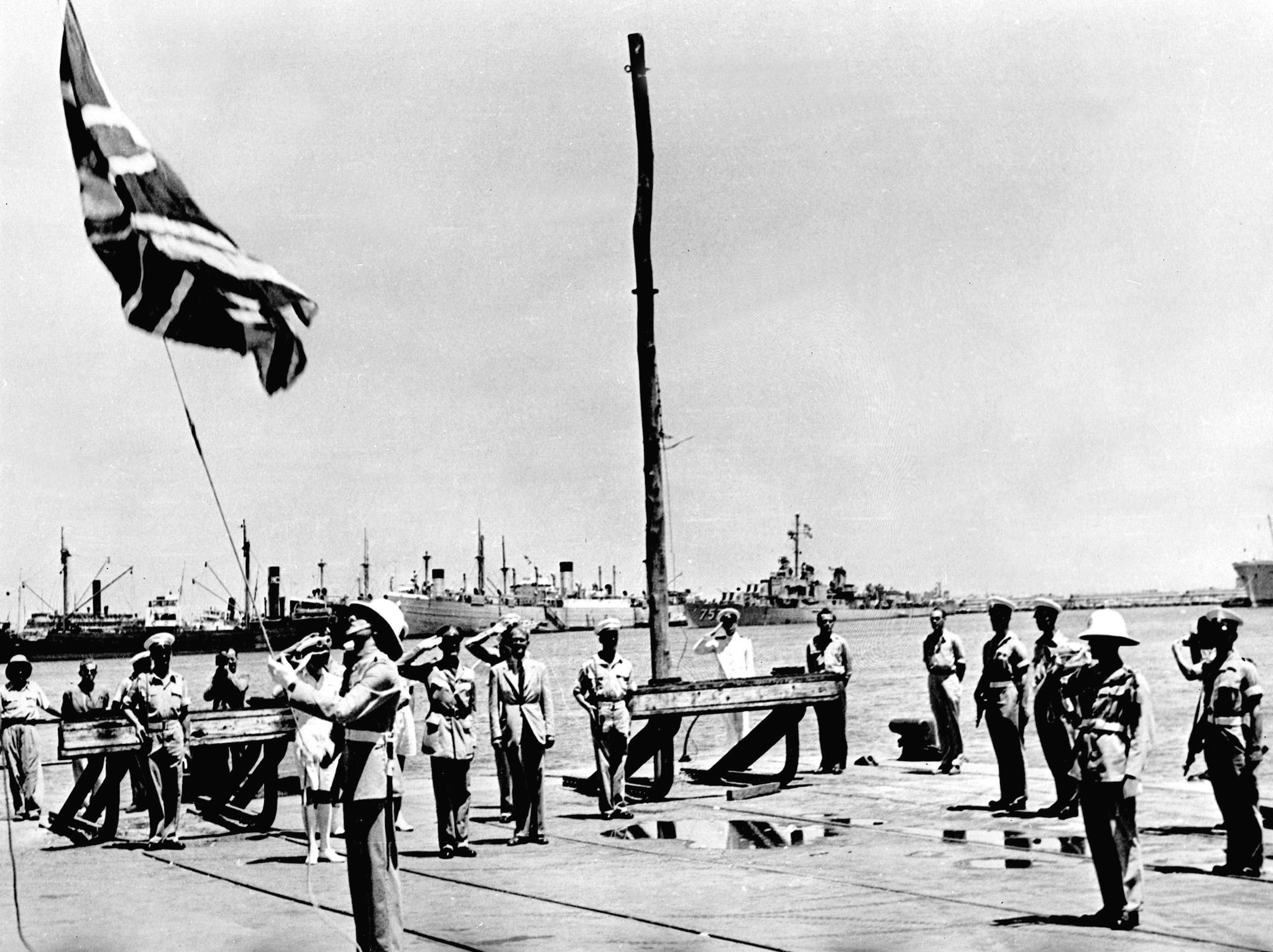

The British flag is lowered for the last time in Haifa, in 1948. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The situation in Palestine had begun deteriorating after the end of World War II, and it grew steadily worse between 1945 and 1947, as the British Mandate approached its end. The entire country was boiling over with apprehension and hatred, and terrorism was on the rise.

Everyone was involved: the British, Palestinian Jews, and Palestinian Arabs. In that tense era, there was literally no neutral ground left: everyone was entrenched and protecting their own.

The British, Jews, and Palestinians did have one thing in common: they respected the fact the Guardian, the world head of the Bahá'í Faith was apolitical and that meant that Shoghi Effendi was universally respected and left alone. This only added to the Guardian’s lifelong reputation as a man of dignity, integrity, honor, unbending principle, and iron-clad will.

The Guardian’s position of absolute neutrality—despite the fact he was clearly Middle-eastern, and had been born in Palestine—was an oddity in the political and social context of Palestine before the end of the British Mandate.

David Ben-Gurion, flanked by the members of his provisional government, reads the Declaration of Independence in the Tel Aviv Museum Hall on May 14, 1948. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

On 14 May 1948, the last of the British forces left what used to be called British Mandate Palestine from Haifa.

The Jewish People's Council—the main executive organization within British Mandate Palestine from 1920 to 1948—gathered at the Tel Aviv Museum and proclaimed the establishment of a Jewish state in Eretz Israel, to be known as the State of Israel.

That same evening, the United States recognized the State of Israel, followed three days later by the Soviet Union.

The Prison Cell of Bahá’u’lláh around 1965. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

The State of Israel came into being on 14 May 1948, and a few months later, the Bahá'ís learned that the Government wanted to turn the barracks in 'Akká—known to Bahá'ís as the Most Great Prison—into a psychiatric hospital.

The Bahá'ís were understandably worried about how this would affect a Holy Place contained in the 'Akká barracks—the prison cell where Bahá'u'lláh spent two full years between 1868 and 1870.

During the British Mandate, the Government had put up a plaque indicating that Bahá'u'lláh had stayed in the barracks, but now, the fate of the Holy Place was uncertain.

One day, a letter arrived, addressed to the “Bahá'í Community.”

In this letter, the Israeli authorities expressed their willingness to entrust the cell of Bahá'u'lláh in the Most Great Prison to the Bahá'ís permanently, and asking for someone to come and retrieve the key.

The letter seemed miraculous to the Bahá'ís, used to obtaining keys to Holy Places only after lengthy, painful, protracted. This was the complete opposite: not only were they simply given the keys, no questions asked, but the initiative had come from the government!

The Guardian appointed three Bahá'ís to go and receive the keys from the Israeli authorities.

The first Bahá'í had a deeply meaningful and 80-year connection to the Holy Place: his name was Salah Jarrah and he was the great-nephew of Colonel Aḥmad Jarráh, the Commander of the Guard who had converted to the Bahá'í Faith while Bahá'u'lláh was under his guard in the Most Great Prison.

Appointed by the Guardian along with Salah Jarrah were. Ben Weeden—who was serving Shoghi Effendi and the Bahá'í World Centre—and Gladys, Ben’s wife, also serving the Guardian in Haifa.

On the day the keys of Bahá'u'lláh’s cell in the Most Great Prison were obtained, the Guardian, Salah Jarrah, and Ben and Gladys Weeden went to the cell, and said prayers in three languages.

One of the most significant and iconic Holy Places associated with Bahá'u'lláh’s ministry—his prison cell in the Most Great Prison—was in the hands of the Bahá'ís now and forevermore.

A view of the Bay of Haifa from the top of the ninth terrace. Source: Bahaimedia.

Shoghi Effendi began extending the terraces in the winter of 1932 and seven years later, by November 1939, he had completed seven terraces below the Shrine, but the first two terraces leading up Mount Carmel from Ben Gurion Avenue, the last two terraces he needed to build, were a problem.

There were several houses on the slope of Mount Carmel which extended to current-day Ben Gurion Avenue, and they were exactly where the Guardian’s last two terraces, the ones connecting to the street, needed to be. One of these houses belonged to Mr. 'Azíz Sulaymán Dumit, a Christian who had erected a large illuminated cross on his roof. When the Bahá'ís tried to purchase his house in 1933, he sued.

Dumit’s 1933 case came before the Haifa District Court and Shoghi Effendi argued that because it concerned a Holy Place, it was outside the court’s jurisdiction. By 1935, Mr. Dumit’s finances had seen a turn for the worst and he dropped the civil case and begged Shoghi Effendi to purchase his house, which the Guardian was able to do thanks to the generosity of the American Bahá'í community.

Between the 1930s and the 1940s, Shoghi Effendi was forced to pause the progress of his project to bring to life 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s vision of the nine lower terraces of the Shrine of the Báb.

There were two reasons for this. First, of course, was World War II, which raged from 1939 to 1945, and second, was the increase in activity of the Covenant-breakers, which necessitated the Guardian’s full attention to annihilate. These attacks, from the east and the west, are covered in separate sections.

In the winter of 1948/1949, Shoghi Effendi managed to strengthen the wall of the mountain at the back of the Shrine, and extend the terrace of the Shrine of the Báb by 60 meters to the east, personally and closely supervising the entire project.

David Ben-Gurion, the Prime Minister of the Provisional Government. Source: Encyclopaedia Britannica.

On 20 January 1949 David Ben-Gurion, the Prime Minister of the Provisional Government, came to Haifa on his first official visit and the Mayor of Haifa naturally invited Shoghi Effendi to attend the reception being given in his honor by the Municipality.

The Guardian could not attend this function, because, as Head of the worldwide Bahá'í community, in this particular reception, he would not have received proper protocol and respect. In fact, William Sutherland Maxwell, whom the Guardian sent as his representative, confirmed this. As its Guardian, Shoghi Effendi always had to ensure the Faith of Bahá'u'lláh received its proper respect, in any gathering or event.

The Guardian, however, wished to show courtesy to David Ben-Gurion, and, with great difficulty, arranged a visit to call on him in person during his very brief stay in Haifa which ended two days before the first general election in the State of Israel.

At 7:15 PM on Friday 21 January 1949, the Guardian met Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion in the Mount Carmel home he was staying in. The meeting lasted 15 minutes, Ben-Gurion asked about the Faith and Shoghi Effendi’s role in it, and asked if there was a book on the Faith he could read. Shoghi Effendi answered his questions, and later sent him a copy of God Passes By, which Ben-Gurion acknowledged with thanks.

Shoghi Effendi had been trying for 25 years to get the Bahá'í Faith recognized in Israel, not as a local community but as a World Center, and so this face-to-face meeting with David Ben-Gurion was very important.

“He is without peer. There is no one like him.” Photo by Conscious Design on Unsplash.

Ben Weeden, the fiancé of Gladys Anderson arrived on 19 March 1948, and they were married. Ben also served at the Bahá'í World Centre, and formed a deep and indelible impression of the strength of the Guardian, the great burden he so elegantly carried, and the superhuman pace he kept, while at the same time being a deeply wonderful person:

One can only marvel at the scope of his mind and the strength of him. Yet, tho' he is fire and steel, he is the most loveable, understanding, compassionate and considerate person I have ever known. He is without peer. There is no one like him.

Curtis Kelsey. Source: Bahaimedia.

One day, while Curtis was living in Teaneck, he received a letter from Shoghi Effendi’s secretary, enclosing a check for $600, and asking him to get the check to a jeweler in New York City.

From Shoghi Effendi’s letter, Curtis only had the name of the jeweler—a very common name—but no home or office address. Curtis opened the Manhattan Telephone Book, and saw there were hundreds of men with the same name as the jeweler. ,His wife Harriet thought finding that man would be impossible, like finding a needle in a haystack, probably.

But Curtis was a man of deep Faith and he was never discouraged. He always relied on divine assistance, and Bahá'u'lláh had always come through for him in the past, when he had been faced with impossible situations, so he picked a “John Smith” at random, and dialed his number. The man answered and Curtis asked him:

Do you know His Eminence, Shoghi Effendi Rabbání?

The man responded:

Yes, I do.

Curtis responded to the Guardian that same night, informing him that he had delivered the check.

A United States Postal Service 3 cent stamp from 1949, one of many such denomination stamps that were published that year. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

One day ,Curtis Kelsey was visiting his friend Roy Wilhelm—who would later be posthumously appointed a Hand of the Cause by the Guardian—in North Lovell, Maine. In the course of their conversation, Curtis casually mentioned:

The Shrine of the Báb area on Mount Carmel needs a watering facility, in fact, it was the hope of the Master that one be constructed.

Instead of a watering facility, Roy suggested a water pump, offered to pay for it, and asked Curtis if he would handle the project.

First, Curtis needed to buy the water pump, a very expensive piece of equipment which cost $2,000—$36,000 in today’s currency—but when he called Roy to tell him how much the pump cost, Roy, who was dying of cancer, couldn’t speak to him.

For some reason, Curtis wasn’t worried, and he went ahead and took out a 90-day loan from a bank. Two weeks later, Curtis received a phone call from Leroy Ioas, then the Treasurer of the National Spiritual Assembly of the United States and Canada, asking:

Curtis, are you going to Haifa?

No—I have no plans to.

Well, the Guardian has asked us to send you a check for $10,000.

Curtis chuckled to himself, and told Leroy Ioas:

You better send me the check.

The pump had only cost $2,000 and the Guardian had sent four times that amount. Curtis wondered why, but he opened a bank account, deposited the check, and soon after received a letter from the Guardian explaining what he wanted purchased: it was a lot more than the pump.

Over the next few years—and an additional $40,000 later—Curtis had bought and shipped a brand new Ford pickup truck, an automobile, 3,000 feet of water hose, cable-wiring, fixtures to the Guardian in Haifa.

Not long after the shipment left for Haifa with all the items Shoghi Effendi had requested, Curtis received a letter from the Guardian asking him to close the bank account.

Curtis checked his account balance, he realized there was only three cents left in the account! Curtis had never sent the Guardian a bank statement, he was the only one who received them.

When Curtis went to the post office to mail his final report to the Guardian, the stamp for the letter cost exactly three cents!

Curtis’ serviced were deeply appreciated by Shoghi Effendi, for whom nothing, not even three cents, escaped notice, and on 6 June 1949, he wrote a letter to Curtis and his wife Harriet, thanking them for their precious services:

Dear and Valued Co-Workers: Your constant services, rendered with such loyalty, zeal and perseverance, will never be forgotten, and are highly meritorious in the sight of God. Be assured, happy and grateful and persevere in your noble endeavors. I will continue to supplicate on your behalf that the Master’s richest blessings may crown your efforts with signal success. Your true and grateful brother, Shoghi

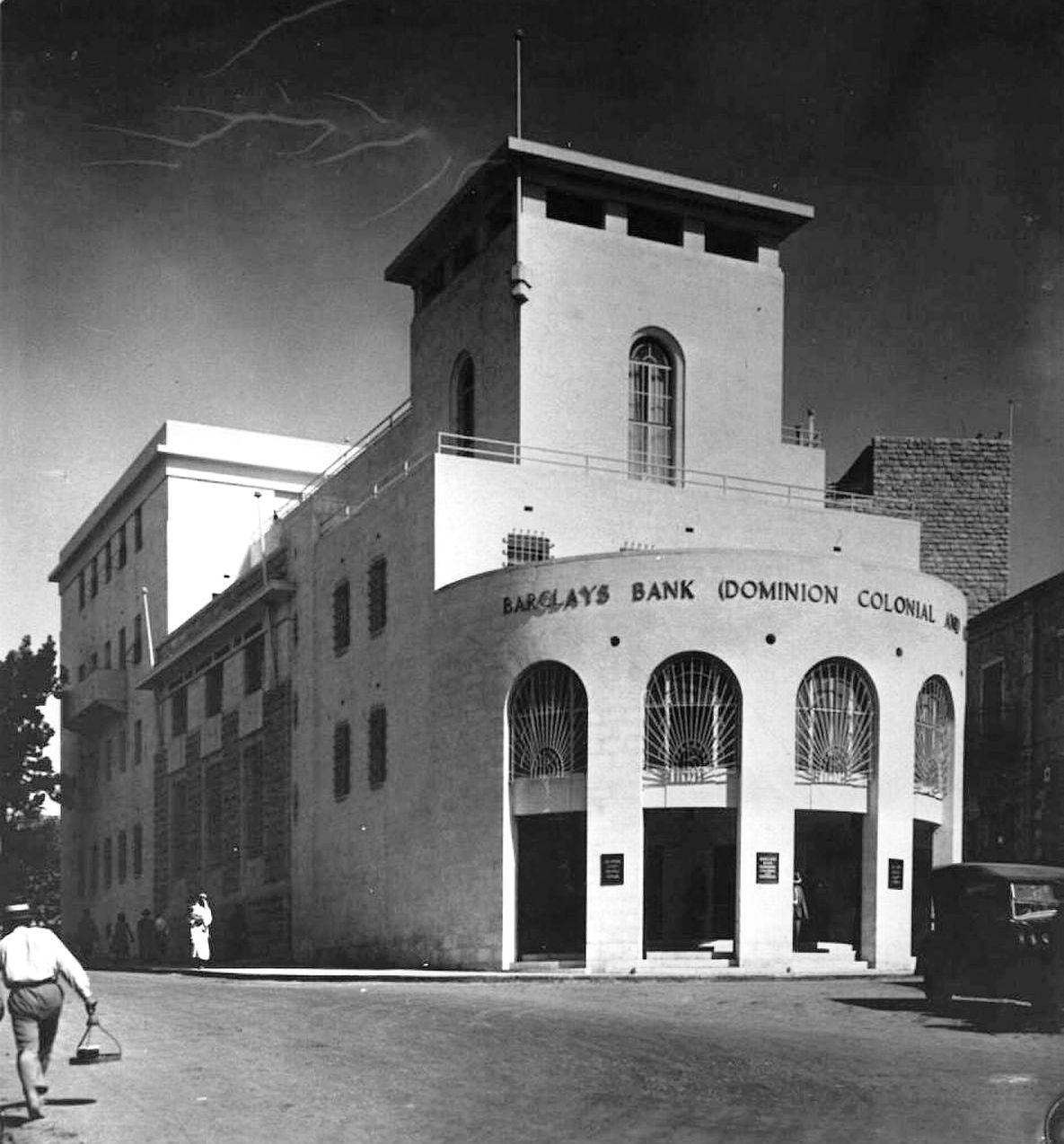

Barclays Bank of Jerusalem in the. 1940s. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

In the summer of 1949, the Guardian had to leave and the only person in Haifa was William Sutherland Maxwell, who was over 74 years old, and didn’t speak any Persian or Arabic. Shoghi Effendi gave him instructions, and William Sutherland Maxwell took charge of the affairs of the Faith.

When the Guardian returned, he asked William Sutherland Maxwell for the account books. William Sutherland Maxwell handed them back, and proudly told the Guardian that they now had £57,000 in Barclays Bank—£2 million today, adjusted for inflation.

Shoghi Effendi said:

What? Where did you get that from?

William Sutherland Maxwell mentioned the name of a Bahá'í whom the Guardian was displeased with, and he instructed his father-in-law:

Go down tomorrow to the bank and transfer it back to his account. I will have nothing to do with it

Later Shoghi Effendi told Rúḥíyyih Khánum:

How can I take money from a man with whom I am displeased? Am I to take his money and then go on being displaced with him and shunning him and disgracing him? And as I'm certainly not going to take his money and forgive him because I've taken his money, then I can't take his money.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum comments, regarding this story:

This was Shoghi Effendi. This kind of integrity, friends, will keep this Cause spotless for a thousand years. It is the integrity that all the Bahá’ís must follow and the integrity that all the assemblies must follow because it is standard of God.

The Bahá'ís of Burma with the completed sarcophagus before it is shipped to 'Abdu'l-Bahá. You can see the inscriptions by Mishkín-Qalam on the sides. Bahá'í Media Bank.

In 1897, as 'Abdu'l-Bahá was constructing the Shrine of the Báb, He began making plans for how to befittingly inter such holy and precious remains. To that end, 'Abdu'l-Bahá began an extensive correspondence with the Bahá'ís of Burma, and gave them a plan and very specific instructions for the construction of a one-piece sarcophagus of the finest marble. Mishkín-Qalam—the most eminent Bahá'í calligrapher of his time—happened to be visiting Burma at the time, and 'Abdu'l-Bahá instructed him to inscribe ‘Yá Bahá’u’l-Abhá’ (O Glory of the All-Glorious) and ‘Yá ‘Alí’u’l-A‘lá’ (O Exalted of the Most Exalted Ones) on the sides of the sarcophagus. 'Abdu'l-Bahá also ordered a hardwood coffin of the best Indian wood, and both the sarcophagus and the coffin arrived in the Holy Land in 1899.

Shoghi Effendi told Ugo Giachery that the Bahá'ís of Burma had also built and shipped a second, almost identical sarcophagus for the remains of Bahá'u'lláh, but it had never reached Haifa.

In the late 1940s, the Guardian asked Ugo Giachery to arrange for its transportation to the Holy Land but the worsening political situation in the area prevented Ugo Giachery from fulfilling this plan. Ugo Giachery states, in relation to this second sarcophagus:

The sarcophagus is now in good hands waiting for the opportunity to be sent to its rightful destination and thus fulfil another wish of the Guardian, as part of his plan to beautify that Holy Shrine.

An illustration of a rainy muddy path. Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash.

On 5 April 1949, Shoghi Effendi was meeting with Rúḥíyyih Khánum, Gladys and Ben Weeden when Rúḥíyyih Khánum noticed he had a mud stain on his coat. She asked her husband what he had been doing and Shoghi Effendi replied:

I had a fight with General Mud, only he won!

Then, Shoghi Effendi explained he had fallen down again, because it was so slippery from the rain, and everyone had a good laugh.

After World War II, Rúḥíyyih Khánum’s heart broke from the confused and disillusioned soldiers returning from the conflict, to a strange and unfamiliar civilian life. Rúḥíyyih Khánum yearned to find a way and provide them with some assurance, some light, some direction, a way to see hope for the future.

It was the Guardian who encouraged Rúḥíyyih Khánum to turn her yearning into a book, and this is how Prescription for Living came to be.

Prescription for Living is an informal—and at times humorous—conversation between Rúḥíyyih Khánum and anxious youth living in a post-war world and trying to find meaning to their lives. The main subject of Prescription for Living is the rampant unhappiness, confusion and uncertainty of a devastated world, and reasons to find hope, happiness, clarity of mind, and assurance.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum addresses love and marriage, our habits, work, death, difficulties, with great sympathy and confidence, breaking down each topic into its component parts, analyzes them, guides the reader to find their truth, but never shies away from offering the solution she has at hand. Her inspiration for advice comes from the Bahá'í Writings, but she also takes the opportunity to teach the Faith in the book itself. Of the 13 chapters in Prescription for Living, two of them are entirely dedicated to the Bahá'í Faith’s history and teachings—Chapter 11: The burgeoning—about Bahá'u'lláh.

In the final chapter, “You,” Rúḥíyyih Khánum brings the entire book together on the theme of personal transformation, opening with a five-word sentence:

World reform is personal reform.

After having introduced her readers—in two preceding lengthy paragraphs—to the Bahá'í Faith, Rúḥíyyih Khánum opens the door for them to take matters into their own hands:

We have everything we need to-day. The stage is set. All that remains is to roll up the curtain and start the play.

In her own introduction to Prescription for Living, Rúḥíyyih Khánum calls the thoughts she puts forth in her book “as straws on the wind, hoping others may see in them the direction in which it is blowing,” and that is why she gave her book that title. It is a recipe book for a happy, fulfilled, spiritual life.

Rúḥíyyih Khánum’s dedication to her beloved martyred mother reads like a poem:

To

MAY BOLLES MAXWELL

Who gave me the gift of life,

But better still, the beloved

Mother of my soul.

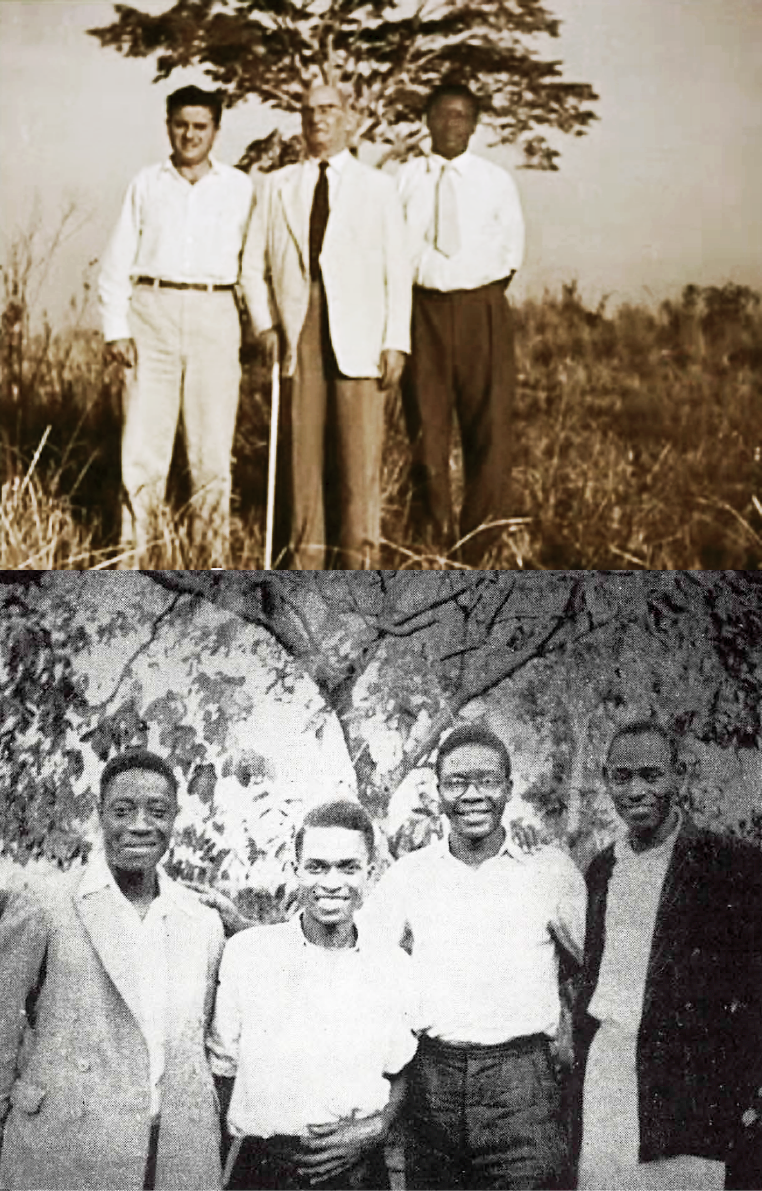

The African Campaign from 1950 to 1953 was an ambitious Teaching project the Guardian entrusted to the National Spiritual Assembly of the British Isles to promote the spread of the Bahá’í Faith in Africa. It was a coordinated effort between six National Spiritual Assemblies:

- The National Spiritual Assembly of the British Isles,

- The National Spiritual Assembly of Egypt

- The National Spiritual Assembly of India

- The National Spiritual Assembly of Iran

- The National Spiritual Assembly of the Sudan

- And the National Spiritual Assembly of the United States

The African Campaign was very historic and deeply significant, because it was the first Plan conceived by the Guardian, in a sense a trial on the Guardian’s part to involve international cooperation between six National Spiritual Assemblies in the Bahá'í world.

The African Campaign was the Plan which would lay the groundwork for the Ten Year Crusade, which would be inaugurated in 1953, at the conclusion of the Campaign.

Background image: Distance view of the Barracks Square in Tabríz where the Báb was martyred. Photos taken in the dead of winter of a later year. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

On 4 July 1950, the Guardian sent a 1,027-word cable to the Bahá'ís of the United States and Canada five days prior to the centenary of the Martyrdom of the Báb.

The Guardian’s message was eight paragraphs long and opened with a powerful reminder to the American Bahá'ís that the Dispensation founded by the Báb was the culmination of a 6,000-year-old Adamic cycle and that the Bahá'í Cycle He inaugurated was destined to last 500,000 years.

This is how the Guardian poignantly describes the Báb’s Martyrdom:

The last act consummating the tragic ministry of the Master-Hero of the most sublime drama in the religious annals of mankind, signalizing the most dramatic event of the most turbulent period of the Heroic Age of the Bahá’í Dispensation, destined to be recognized by posterity as the most precious, momentous sacrifice in the world’s spiritual history.

The Guardian describes the Báb’s agonies, “the glad-tidings He announced, the warnings He uttered, the forces He set in motion, the adversaries He converted, the disciples He raised up, the conflagrations He precipitated, the legacy He left of faith and courage, the love He inspired,” and in the one hundred years elapsed since His Martyrdom and the end of His “meteoric ministry,” he pays tribute to the “successive, marvelous evidence of His triumphant power” and the creative energies released by His Revelation, propelling mankind towards its maturity.

In this sublime tribute, the Guardian draws a direct link between the ministries of the Báb, Bahá'u'lláh, and 'Abdu'l-Bahá, and His own—without ever mentioning himself, of course. What the Guardian does is he cites the clarion call of the Order announced in the Writings of the Báb, a New World Order revealed by Bahá'u'lláh in the Kitáb-i-Aqdas, delineated in 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s Will and Testament, and birthed during Shoghi Effendi’s ministry with the nascent Institutions of Bahá'u'lláh’s Administrative Order on all five continents of the planet.

The Guardian describes the evolution of the Bahá'í Faith from the moment of the Báb’s martyrdom as a birthing and maturation process:

The embryonic Faith, maturing three years after His martyrdom, traversing the period of infancy in the course of the Heroic Age of the Faith is now steadily progressing towards maturity in the present Formative Age, destined to attain full stature in the Golden Age of the Bahá’í Dispensation.

In the penultimate paragraph, the Guardian describes the current achievements of the Faith, accomplished in the last 100 years since the Báb was martyred in Tabríz on 8 July 1850: 2,500 tightly-knit Bahá'í community centers spread over 100 countries, a worldwide community extending as far north as the Arctic Circle, and as far south as the Strait of Magellan, a wealth of Bahá'í literature in 60 languages, boasting $10 million of endowments—$128 million in today’s currency.

A Faith adorned by two Houses of Worship, one in the heart of Asia in ‘Ishqábád, and one in the heart of America in Wilmette, a Faith blessed with the Shrine of the Báb in the Holy Land, consolidated by the incorporation of more than 100 National and Local Spiritual Assemblies, a Faith recognized as an independent world religion in the east and the west, eulogized by Queen Marie of Rumania, fortified by 9 National Spiritual Assemblies, a community energized and consolidated by prosecuting successive teaching plans.

The Guardian’s final appeal in his centenary tribute to the Martyrdom of the Báb is a plea to the American believers, “to hold aloft unflinchingly the torch of the Faith impregnated with the blood of innumerable martyrs and transmit it unimpaired so that it may add luster to future generations destined to labor after them.”

On 9 July 1950, the Bahá'í world commemorated the Martyrdom of the Báb in a diversity of touching events, private and public. Volume 12 of The Bahá'í World listed seven national communities’ commemorative events: those of the United States and Canada, Egypt and the Sudan, Ethiopia, Iran, and Australia and New Zealand.

Recovery of William Sutherland Maxwell. Background image: Construction of the colonnade of the Shrine of the Báb, 1950. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

William Sutherland Maxwell’s health had started declining in 1949. That August, the Guardian was in Europe, and was so worried about his father-in-law that he sent an anxious cable:

Urge you take utmost care avoid possibility sunstroke while inspecting Shrine stop as work progresses you are increasingly precious to us all stop airmail copy photograph Shrine model not too small love.

Sutherland fell gravely ill in the winter of 1949 – 1950, and on 5 April 1950, Sutherland collapsed. and the doctors were hopeless. He could no longer recognize Rúḥíyyih Khánum, the child he idolized, he lost control over his functions, and could barely speak.

William Sutherland Maxwell’s soul was still there, however, and it burned with love for the Guardian each time Shoghi Effendi came to visit him. Although William Sutherland Maxwell could not speak, and gave no sign of registering Shoghi Effendi’s presence, although there was no physical flutter or tremor, an ephemeral but visible reaction passed over him in the presence of his Guardian.

This was so extraordinary—and so obvious—that his nurse, the best in Haifa, was puzzled by it. It defied medical explanation.

Shoghi Effendi was determined that William Sutherland Maxwell would not die, and despite everyone having lost hope, even Rúḥíyyih Khánum, the Guardian insisted that William Sutherland Maxwell be taken to Switzerland, where he rapidly recovered under the care of their own physician and a Swiss nurse.

A few weeks after arriving in Switzerland, Rúḥíyyih Khánum took her father out for his first drive and he noticed a café surrounded by a garden, and invited the friends out on a drive with him for tea.

Shortly after this, on 7 July 1950, the Guardian sent a joyful cable to the Bahá'ís in America on the progress of the construction of the superstructure of the Shrine of the Báb, adding a joyful line about his father-in-law’s regained health:

My gratitude is deepened by the miraculous recovery of its gifted architect, Sutherland Maxwell, whose illness was pronounced hopeless by physicians.

In 1948, with the end of the British Mandate and the formation of the State of Israel, a fierce political upheaval erupted in the Holy Land. War broke out between Arabs and Jews and more than 700,000 Palestinian Arabs fled the country

Almost the entirety of 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s Covenant-breaking family allied themselves with the Arab community and fled Israel for Lebanon.

Among them were the family of Mírzá Jalál, which included Rúhá Khánum, the daughter of Abdu'l-Bahá;

Those who left were:

- Rúhá Khánum—'Abdu'l-Bahá’s third daughter, her husband Mírzá Jalál and their children Muníb and Ḥasan and Duhá;

- Túbá Khánum—'Abdu'l-Bahá’s second daughter—and two of her sons including Rúhí Afnán along with his wife Zahra Afnán— Rúhá Khánum’s daughter;

- Three cousins of Dr. Farid—Munírih Khánum’s nephew who had been excessively cruel to 'Abdu'l-Bahá in 1912 during His journey to America;

- Shoghi Effendi’s sister Rúhangíz and her husband Nayyír Afnán and their two daughters;

- The aging Mírzá Badí’u’lláh—second most notorious Covenant-breaker from 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s ministry after Mírzá Muḥammad-'Alí—and his relatives, along with

- Covenant-breaking Bahá'ís.

These members of Shoghi Effendi’s family began assimilating into Muslim society in Lebanon. Two years later, time went on these people, who were already cut off from the Holy Family by virtue of their association with the enemies of the Faith, integrated themselves into the Islamic society.

On 15 July 1950 Shoghi Effendi sent a devastating cable.

In 45 words, the Guardian had been forced to denounce 12 members of his family: three of 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s four daughters, his own great-aunts Rúhá Khánum, Túbá Khánum, and Munavvar Khánum, his cousin Rúhí, and nine of his cousins.

Inform friends that Rúḥí, his mother, with Rúḥá, his aunt, and their families, not content with years of disobedience and unworthy conduct, are now showing open defiance. Confident that exemplary loyalty of American believers will sustain me in carrying overwhelming burden of cares afflicting me.

After he was excommunicated, Ahmad Sohrab began collaborating with other infamous Covenant-breakers.

In 1950-1951, he supported a lawsuit which Shoghi Effendi’s Covenant-breaking family members brought against the Guardian challenging his right to carry out construction in the vicinity of the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh at Bahjí.

In 1952, Ahmad Sohrab cabled Israel’s Minister of Religion in an attempt to influence the lawsuit, claiming that the Caravan of East and West was not under the authority of Shoghi Effendi and was in support of the Covenant-breaker’s claims.

The case did not go in their favor, because the Guardian’s main enemy, his brother-in-law Nayyír Afnán died before the case was heard, and the court granted full recognition to the Guardian’s legal ownership of all Bahá'í Shrines and properties.

In 1954, Ahmad Sohrab returned to Haifa and collaborated with Covenant-breakers from the time of 'Abdu'l-Bahá—those who were still alive. He was witnessing the victories of the Ten Year Crusade. A robust Administrative Order—something he had fought for 30 years—and a promulgation of the corner in every country of the world by Knights of Bahá'u'lláh, bringing the Faith to virgin territories.

Ahmad Sohrab was furious with the growth and consolidation of the institutions of the Faith. He immediately rallied the old guard of Covenant-breaking, the ones who had opposed Bahá'u'lláh in His ministry, and those who had rebelled against 'Abdu'l-Bahá during his ministry. He organized meeting s with them encouraged them and gave them his support.

Ahmad Sohrab went so far as to publicly announce that Bahá'u'lláh had, in fact, appointed twin successors: 'Abdu'l-Bahá and Mírzá Muḥammad-'Alí and that 'Abdu'l-Bahá had disobeyed the Book of Bahá'u'lláh’s Covenant, the Kitáb-i-Ahd, forcibly taken the reins of the affairs of the Faith in His hands and eliminated Mírzá Muḥammad-'Alí.

He held a press conference and told reporters 'Abdu'l-Bahá was a Muslim. Not that many years ago, Ahmad Sohrab had been saying the opposite, that Bahá'u'lláh was the Manifestation of God for today and that 'Abdu'l-Bahá was His legitimately appointed successor.

In another interview in Tel Aviv, Ahmad Sohrab introduced himself as the secretary of. 'Abdu'l-Bahá and His leading disciple. A journalist asked him about the Will and Testament of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, and asked why he wasn’t working with the worldwide Bahá'í community if he was as sincere as he said he was.

Ahmad Sohrab acknowledged the authenticity of the Will and Testament of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, that Shoghi Effendi was Guardian, but that he had failed at his job and needed to be replaced.

No one in the Holy Land took Ahmad Sohrab seriously.

Nothing the Covenant-breakers were doing had any effect, so they relied on bringing lawsuits against the Guardian for anything they could think of.

In 1956, when the Guardian demolished one of the houses near the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh, Julie Chanler sent a petition to the President of Israel in which she supported the claim of a Covenant-breaker to the property on behalf of a new group called the “Free Bahá'ís.”

The Covenant-breakers continued opposing Shoghi Effendi in such ways until the end of his ministry, without ever making any headway, and without ever gaining any victories. All their tactics fell apart in the end.

Shoghi Effendi once wrote about Covenant-breakers:

Viewed in the light of past experience, the inevitable result of such futile attempts, however persistent and malicious they may be, is to contribute to a wider and deeper recognition by believers and unbelievers alike of the distinguishing features of the Faith proclaimed by Bahá’u’lláh. These challenging criticisms, whether or not dictated by malice, cannot but serve to galvanize the souls of its ardent supporters, and to consolidate the ranks of its faithful promoters. They will purge the Faith from those pernicious elements whose continued association with the believers tends to discredit the fair name of the Cause, and to tarnish the purity of its spirit. We should welcome, therefore, not only the open attacks which its avowed enemies persistently launch against it, but should also view as a blessing in disguise every storm of mischief with which they who apostatize their faith or claim to be its faithful exponents assail it from time to time. Instead of undermining the Faith, such assaults, both from within and from without, reinforce its foundations, and excite the intensity of its flame. Designed to becloud its radiance, they proclaim to all the world the exalted character of its precepts, the completeness of its unity, the uniqueness of its position, and the pervasiveness of its influence.

By the end of Ahmad Sohrab’s life, the movement he had founded had completely disintegrated, while every single one of the Guardian’s ambitious, momentous goals had been surpassed, and the Faith was growing everywhere in the world, including a flourishing Administrative Order.

On 5 August 1950, the Guardian made a historic appeal to African-Americans to pioneer to Africa:

Feel moved to appeal to gallant, great-hearted American Bahá’í Community to arise on the eve of launching the far-reaching, historic campaign by sister Community of the British Isles to lend valued assistance to the meritorious enterprise undertaken primarily for the illumination of the tribes of East and West Africa, envisaged in the Tablets of the Center of the Covenant revealed in the darkest hour of His ministry.

Shoghi Effendi strongly felt that, although this was not one of the objectives of the Second Seven Year Plan, this added responsibility was crucial and constituted a worthy response on behalf of the African-American people, whom 'Abdu'l-Bahá had so dearly cherished, and so repeatedly blessed, and for whom He had so ardently prayed, and for whose destiny He had cherished the highest hopes. This was how Shoghi Effendi connected the African American people’s service to the hopes of 'Abdu'l-Bahá Himself:

Though such participation is outside the scope of the Second Seven Year Plan, I feel strongly that the assumption of this added responsibility for this distant vital field at this crucial challenging hour, when world events are moving steadily towards a climax and the Centenary of the birth of Bahá’u’lláh’s Mission is fast approaching, will further ennoble the record of the world-embracing tasks valiantly undertaken by the American Bahá’í Community and constitute a worthy response to ‘Abdu’l‑Bahá’s insistent call raised on behalf of the race He repeatedly blessed and loved so dearly and for whose illumination He ardently prayed and for whose future He cherished the brightest hopes.

'Abdu'l-Bahá had spoken at an African-American Methodist Church in Washington, D.C. on 23 April 1912, shortly after arriving in America, and later, He wrote a loving letter, filled with tenderness to an African-American Bahá'í, in which He poured out his love for a long-oppressed people:

O thou who art pure in heart, sanctified in spirit, peerless in character, beauteous in face! Thy photograph hath been received revealing thy physical frame in the utmost grace and the best appearance. Thou art dark in countenance and bright in character. Thou art like unto the pupil of the eye which is dark in colour, yet it is the fount of light and the revealer of the contingent world. I have not forgotten nor will I forget thee. I beseech God that He may graciously make thee the sign of His bounty amidst mankind, illumine thy face with the light of such blessings as are vouchsafed by the merciful Lord, single thee out for His love in this age which is distinguished among all the past ages and centuries.

William Sutherland Maxwell and Rúḥíyyih Khánum in 1948. Source: Bahaimedia.

After his near-death illness, William Sutherland Maxwell, then 77 years old, was very weak and frail, and suffered painful, recurring gall bladder attacks.

According to Rúḥíyyih Khánum, Shoghi Effendi had an impatient temperament, brought about the never-ending pressures of his work and his permanent lack of time, but with William Sutherland Maxwell, in the last two years of his life, the Guardian was the essence of marvelous gentleness and patience.

William Sutherland Maxwell, for his part, simply worshiped Shoghi Effendi and Rúḥíyyih Khánum went even further in describing his love for his Guardian:

There is no adjective to describe the degree to which my father adored him. His feelings were not only based on his deep faith as a Bahá'í, the respect and obedience he owed him as Guardian of his Faith, but also on his love for him as a man he profoundly admired in every way, and of course because of the personal human relationship which he felt very deeply.

When William Sutherland Maxwell had lost his last sister in 1942, Shoghi Effendi told him that he should now consider Haifa his first home and that he could not spare him.

Shoghi Effendi was equally warm to all of William Sutherland Maxwell’s Christian family. When they wrote letters, they always addressed him as Shoghi, something a Bahá'í would never dream of calling the Sign of God on Earth. Rúḥíyyih Khánum was embarrassed when she read the informal letter to Shoghi Effendi but he simply said, in the sweetest way:

Convey my love to them too.

The Guardian did not stand on ceremony for things like this. He was noble and simple in his relationships with those he loved.

Shoghi Effendi teased William Sutherland Maxwell in the sweetest way imaginable. William Sutherland Maxwell, the Scot-Canadian, came from a background where men didn’t wear perfume and he never even used a scented lotion. Shoghi Effendi took great pleasure in enthusiastically rubbing attar of rose on William Sutherland Maxwell, and Rúḥíyyih Khánum absolutely loved to see the expression on her father’s face when Shoghi Effendi did this, It was an extraordinary—and most probably hilarious—mixture of panic at the idea he was about to smell strongly for several hours, and pure joy at having received the loving attention of his beloved Guardian.

Mírzá Badí’u’lláh was the youngest son of Bahá'u'lláh. He spent 60 years of his life betraying Bahá'u'lláh and 'Abdu'l-Bahá, and perpetrating acts of treachery, deceit, all borne of his jealousy and arrogance. It was Mírzá Badí’u’lláh who had seized the keys of the Shrine of Bahá'u'lláh on 30 January 1922.

When he finally died, on 3 November 1950, Shoghi Effendi sent this cable to the world, not only announcing the death of one notorious Covenant-breaker, but three vile individuals.

The first of course was Mírzá Badí’u’lláh, the brother of the Arch-breaker of the Covenant of Bahá'u'lláh.

The other two who died around the same time as Mírzá Badí’u’lláh, were Mírzá Muḥammad-'Alí’s sons and therefore Badí’u’lláh nephews, Shu'a'u'lláh and Músá.

This is the cable the Guardian sent regarding these three despicable individuals:

Badí’u’lláh, brother and chief lieutenant of Archbreaker of divine Covenant, has miserably perished after sixty years’ ceaseless, fruitless efforts to undermine the divinely-appointed Order, having witnessed within the last five months the deaths of his nephews Shoa and Musa, notorious standard-bearers of the rebellion associated with the name of their perfidious father.

Aerial view of the Mansion of Mazra'ih and surrounding gardens, April 1979Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

The Mansion of Mazra’ih was the first place Bahá'u'lláh had lived after His nine years in the grey stones of the Most Great Prison and inside the walls of the Prison-City of 'Akká.

The Mansion was a Muslim religious endowment, the property of the descendants of Muḥammad Safwat.

Around 1928, a Bahá'í named Lilian McNeill—a childhood friend of Queen Marie of Romania—and her husband, a Brigadier-General who had fought with General Allenby in the conquest of Palestine, visited the Holy Land and came across the Mansion of Mazra’ih.

At the time, a Bedouin family was living in a tent in the garden and the olive pickers stayed on the ground floor of the house during harvest. The Mansion had fallen into disrepair but its gorgeous vaulted rooms were still there, as were the centuries-old cypress trees standing guard beside it.

Starting in May 1931, when her husband retired, until 1949 when she passed away, Lilian McNeill and her husband leased the Mansion of Mazra’ih, restored it, planted a garden, but left the cement floor on the ground floor untouched, as they believed it had been blessed by Bahá'u'lláh’s footsteps.

Now that the Mansion of Mazra’ih was empty, the Israeli government planned to turn it into a rest home for officials.

The Guardian appealed to all concerned departments of the Government, to no avail, until he appealed directly to the Prime Minister, David Ben Gurion, explaining the profound significance of the Mansion of Mazra’ih for Bahá'ís, and his desire to turn it into a place of pilgrimage.

David Ben Gurion himself intervened, and the Mansion of Mazra’ih was leased to the Bahá'ís as a historic site.

On 16 December 1950, the Guardian joyfully cabled the Bahá'í world:

Announce Friends delivery after more than fifty years keys Qaṣr Mazra‘ih by Israel authorities stop historic dwelling place Bahá’u’lláh after leaving prison city ‘Akká now being furnished anticipation opening door pilgrimage.

Background image: Windows on the Haifa Pilgrim House. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

One of Shoghi Effendi’s most distinctive characteristics was the balance which outwardly seemed like a sudden impulse but in fact had been maturing in his mind for years. In this way, Shoghi Effendi, in Rúḥíyyih Khánum’s words had an intense objectiveness that God Himself had endowed him with as the Guardian. He was an “absolutely unselfconscious instrument.”

Sudden decisions of the Guardian, brought forth with immense confidence and assurance, had been mulled over in his mind for a long time—weeks, months, and sometimes years—before acting upon them, and when the moment finally came, the Guardian never waited five seconds to act on the decision.