Written and illustrated by Violetta Zein

This part covers the life of the Greatest Holy Leaf from the age of of 22 in 1868 to the age of 46 in 1892.

An 1854 watercolor showing three Ottoman soldiers, left to right: a soldier in the light infantry regiment; a sergeant, line artillery; and a bashi-bazouk, an irregular soldier of the Ottoman army. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

One day, on a mid-August morning of 1868, Bahá'u'lláh and His family were sitting quietly at home together in the house of ‘Izzát Áqá, when, all of a sudden, they heard the loud and discordant sound of military bugles being sounded outside. They looked outside their windows to find their home had been completely surrounded by a large number of soldiers, with watchmen posted at the gates.

The Greatest Holy Leaf later said:

This trouble broke with the suddenness of a tornado upon us…Our first thought was that the life of the Blessed Perfection [Bahá'u'lláh] or of ‘Abbás Effendi ['Abdu'l-Bahá] was threatened.

'Abdu'l-Bahá calmed the family while He went outside to find out what was happening.

He was handed a letter from the Governor of Edirne, conveying orders from the Ottoman government for Bahá'u'lláh’s fourth and final exile.

Due entirely to the chaos unleashed by Mírzá Yaḥyá and Siyyid Muḥammad, all of the Bábís in Edirne were to be separated and banished: Bahá'u'lláh to one location, the Holy Family to another, Mírzá Yaḥyá to a third location and the rest of the Bahá'ís somewhere else, without anyone having any knowledge of where the rest of them were.

That same day, the Bahá'í shopkeepers or traders were all arrested and placed in the Government House, and all Bahá'ís were called before the authorities, interrogated and forced to confess their Faith. Their belongings and goods were sold or auctioned the following day, and they were told they had three days to prepare for leaving Edirne.

In the Súriy-i-Ra’ís (Surah to the Chief), Bahá'u'lláh later testified that He and His family were left without food that first night, and that their neighbors wept over their plight. Foreign consuls came to call on Bahá'u'lláh offering their government’s help. Bahá'u'lláh told them that His relief lay in the hands of God.

Bahá'u'lláh refused to leave Edirne until all His debts could be settled in the bazaar.

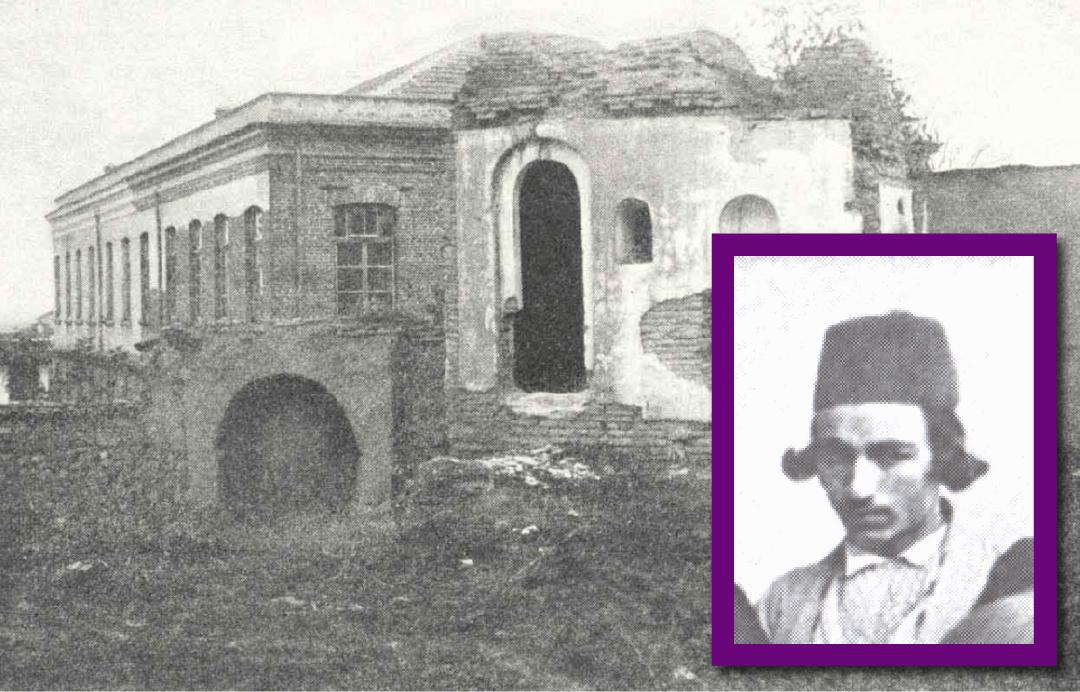

The location and a protagonist of the scene retold below: The house of ‘Izzát Páshá and Husayn-i-Áshchí. Photo of Husayn-i-Áshchí from Bahaipedia.

Husayn-i-Áshchí was the cook of the Holy Family, and witnessed the tragic event of Ḥájí Ja'far-i-Tabrízí’s suicide attempt and the calm and collected composure the Greatest Holy Leaf as she faced this difficult crisis.

In the days preceding His departure from Edirne towards His final exile, Bahá'u'lláh had lovingly explained to the Bahá'ís that some of them would have to stay behind.

One of these Bahá'ís was a particularly enkindled and devoted Bahá'í, a sensitive man named Ḥájí Ja'far-i-Tabrízí. Something broke in Ḥájí Ja'far’s soul when he realized he would be separated from Bahá'u'lláh, and he tried to commit suicide. He decided if he couldn’t live in the presence of Bahá'u'lláh, he would just not rather live at all. He took a razor and put his head out of a window that gave onto the street and tried to slice his throat.

At the moment that Ḥájí Ja'far attempted to end his life, Husayn-i-Áshchí was in the outer apartment of the house of ‘Izzat Áqá, doing something very mundane: he was counting the number of people, so he could tell the Greatest Holy Leaf, who was preparing dinner, how many people needed to eat.

The Greatest Holy Leaf was in the kitchen, waiting for Husayn-i-Áshchí to give her number of people to feed but he had just seen the body of Ḥájí Ja'far and was in a state of total shock. The Greatest Holy Leaf waited and waited, and finally sent a Bahá'í woman in search of Husayn-i-Áshchí.

When the woman saw Ḥájí Ja'far, she fell unconscious.

With still no news of Husayn-i-Áshchí, the Greatest Holy Leaf sent a Christian woman who served the Holy Family as a maid in search of the strangely absent Husayn-i-Áshchí. The Christian woman saw Ḥájí Ja'far, and she too, fell unconscious on the ground, right next to the other woman.

This was an incredibly stressful time for everyone in the house of ‘Izzat Áqá.

'Abdu'l-Bahá asked Husayn-i-Áshchí to go and fetch some of his own clothes so that they could changes the blood-stained clothes of Ḥájí Ja'far.

It was on his way to run this errand for 'Abdu'l-Bahá that Husayn-i-Áshchí saw the two unconscious women lying on the floor. He took some time to sprinkle water on their faces so that they could regain consciousness, and accompanied them into the kitchen when the Greatest Holy Leaf was waiting for them.

The members of the Holy Family in the kitchen saw the haggard look on their faces and demanded to know what had happened. The Greatest Holy Leaf asked Husayn-i-Áshchí:

Tell me the truth, what is the matter? Why are you all so frightened?

In the end, Husayn-i-Áshchí told her the entire truth, and suggested hiding it from Bahá'u'lláh until after He had had his supper.

And this is where the Greatest Holy Leaf, only 22 years old at the time, showed her tremendous strength. Bahíyyih Khánum felt such compassion for Ḥájí Ja'far’s tremendous spiritual pain at being separated from Bahá'u'lláh, but she also had full knowledge of her Father Bahá'u'lláh’s spiritual power of attraction. It would have been useless to hide anything to Bahá'u'lláh Who already knew everything.

She reminded Husayn-i-Áshchí that this was not the first—nor the last time—that the lovers of Bahá'u'lláh would shed their blood or give their lives in the path of the Blessed Beauty.

Of course, Bahíyyih Khánum had been right.

Ḥájí Ja'far survived: he had providentially missed the carotid artery in his neck. But he absolutely and resolutely refused treatment from the surgeon. It took Bahá'u'lláh’s loving-kindness to change his mind. comforted Ḥájí Ja'far, touched his head and face and promised him that as soon as he was healed, he would join Him in 'Akká, which he did.

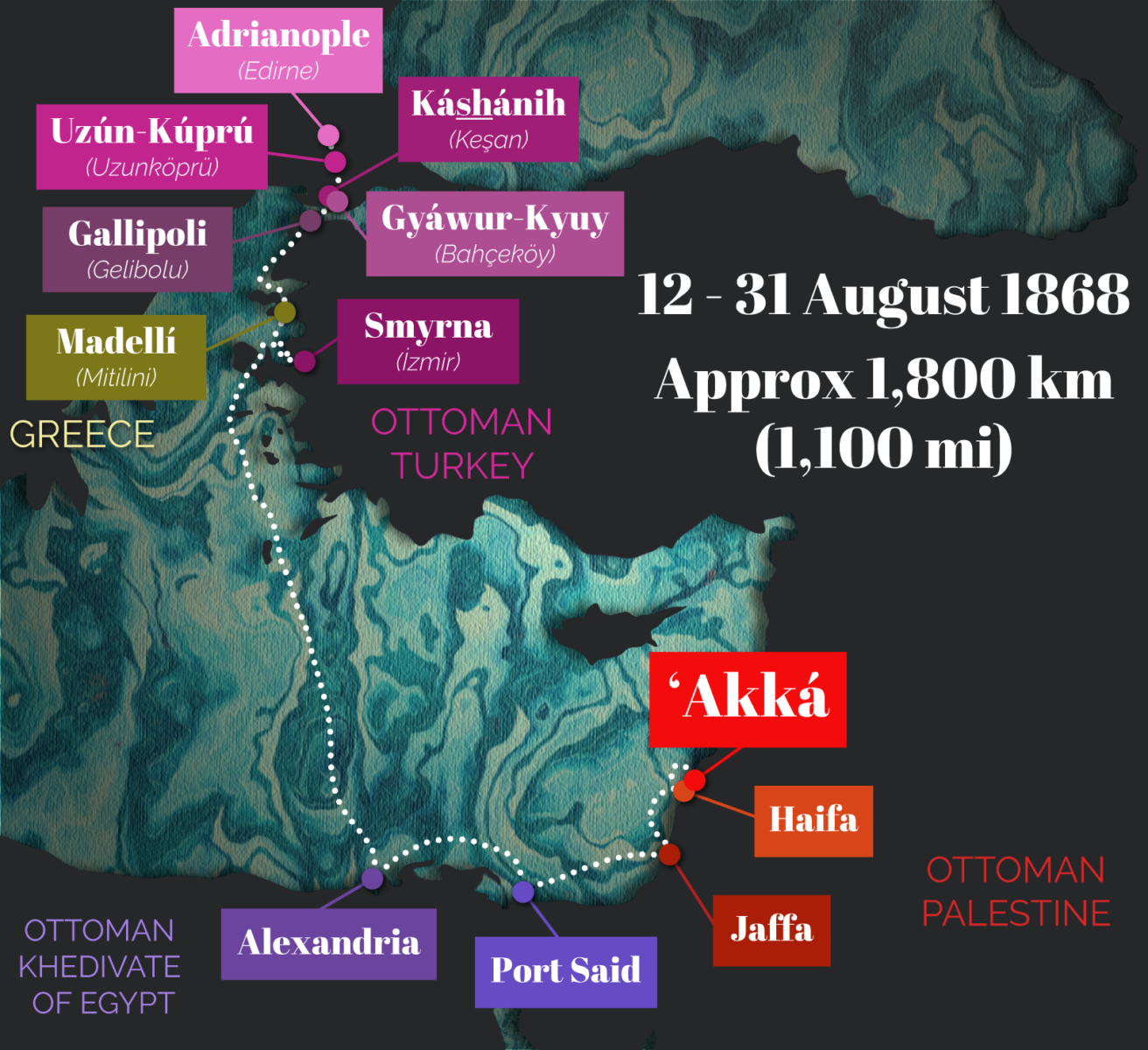

Hand-drawn map showing locations of Bahá'u'lláh's land and sea journey to His final exile in 'Akká mentioned by Shoghi Effendi in God Passes By. Map traced from the 1860 map of Persia, Turkey in Asia, Afghanistan, and Beloochistan by Samuel Augustus Mitchell; Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The journey to 'Akká from Edirne was nearly 1,800 kilometers (1,100 miles).

The exiles traveled roughly one-tenth of the journey overland, approximately 160 kilometers (100 miles) Edirne to Gallipoli.

Ninety percent of the journey—or about 1,600 kilometers (1,000 miles) would be covered by sea aboard nightmarish steamers.

Over the course of this 10-day voyage, Bahá'u'lláh, a Manifestation of God would anchor off the coast of three continents—Europe, Africa, and Asia—and cross through four modern-day countries: Turkey, Greece, Egypt, and Israel.

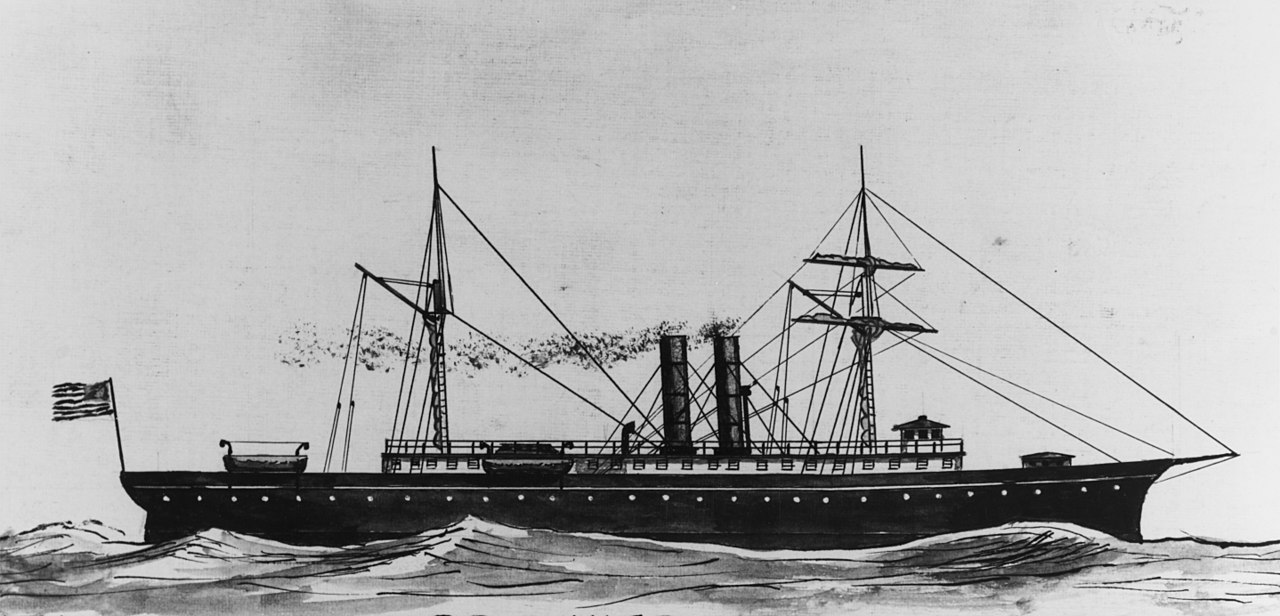

The steamship R. R. Cuyler, built in New York in 1860 for commercial service along the United States east coast. From an original watercolor by Heyl, Erik (1955). This watercolor of a steamship is an accurate depiction of the ship Bahá'u'lláh and the Holy Family would have sailed on from Gallipoli to Alexandria in 8 years' time. Image contributed by Johannes Rosenbaum. Wikimedia Commons.

After 5 days of nightmarish sailing conditions from Gallipoli, the exhausted and famished exiles arrived in Alexandria, Egypt on the morning of 26 August 1868.

Here, Bahá'u'lláh received a letter from the first Bahá'í of Christian origin, Faris Effendi, who had been taught by Nabíl. They were both imprisoned in Alexandria and could see Bahá'u'lláh’s ship from the roof of their prison.

By the time the exiles arrived in the Holy Land on 30 August 1868, there was almost no food left, several exiles were ill because of the unsanitary conditions. The ship was filled with an appalling stench, and was so crowded there was no place to lie down or rest.

The exhausted exiles arrived in Haifa at midnight on 31 August 1868, and were carried ashore in row-boats.

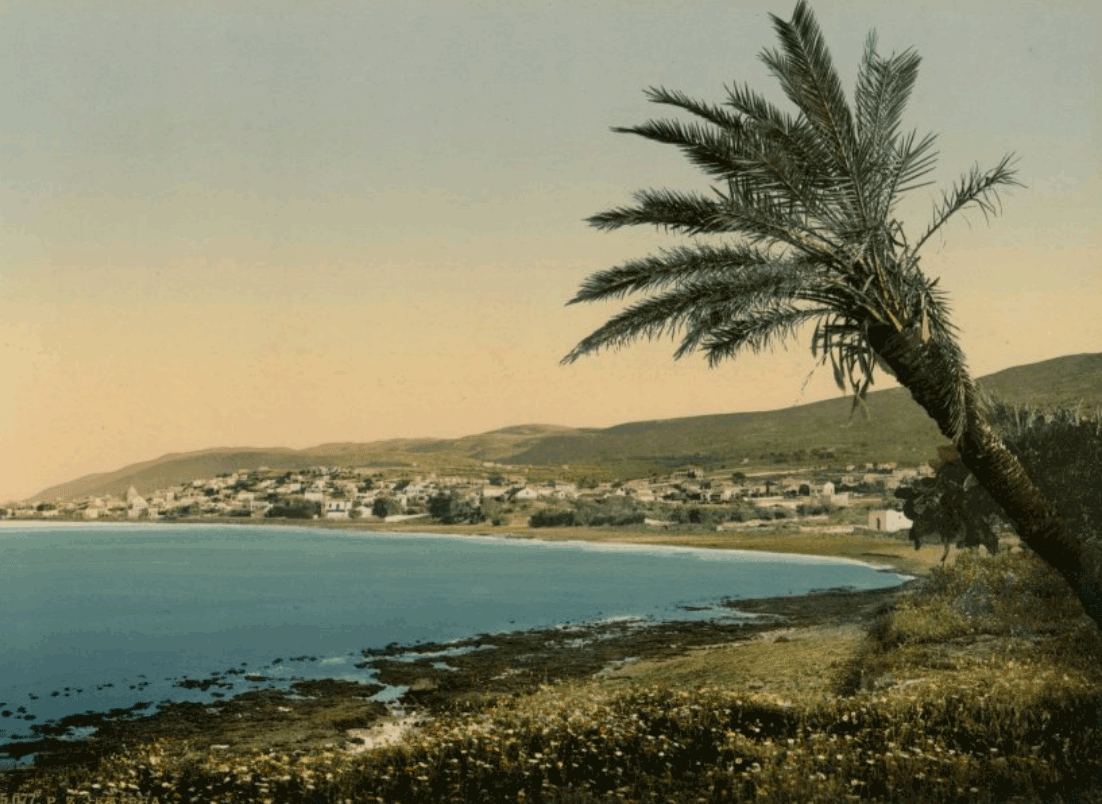

Panorama of Haifa, Photochrome Zurich circa 1895 of the Bay of Haifa. Musée de la Photographie (Online Photography Museum) Exposition: Journey to the Holy Land through the Photochromes from 1880 to 1895.

At last, after hours spent waiting in the heat of Haifa, the exiles, boarded a sailboat for ‘Akká, their final destination for an utterly miserable journey of 16 kilometers (10 miles).

The exiles sailed from Haifa to 'Akká on 31 August 1868.

What was supposed to be a short sailing journey turned into an absolute nightmare.

Bahíyyih Khánum said that by this point in their ordeal, almost everyone was now sick, and they sailed on a windless day for eight hours under the scorching sun with no shade.

The short trip took 8 hours of complete and utter misery.

Bahíyyih Khánum would later recall:

I myself was a healthy woman up to the time of taking this voyage; since then I have never been well.

For the Greatest Holy Leaf to make such a statement about an 11-day sea journey is astonishing.

Bahíyyih Khánum endured three traumatic journeys in the successive exiles of Bahá'u'lláh, first from Ṭihrán to Baghdad in the middle of winter, then four months from Baghdad to Istanbul, and the worst and shortest journey in the coldest winter in four decades from Istanbul to Edirne.

But she would single out the fourth and last journey, the shortest of all by far, as the only one that had a permanent, lifelong effect on her physical health and wellbeing.

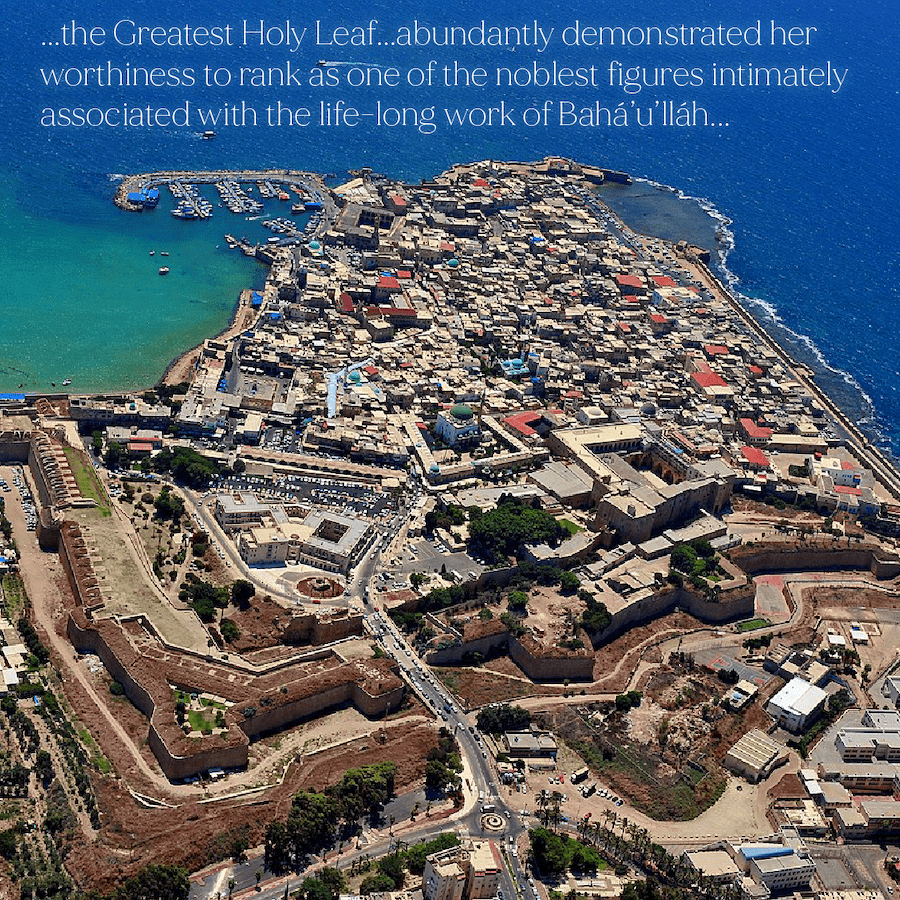

With their arrival in the prison-city of 'Akká on 31 August 1868, at the far ends of the Ottoman Empire, a new chapter in Bahíyyih Khánum’s life was opening.

A 1920 photograph of the sea gate where The Greatest Holy Leaf disembarked at 'Akká on 31 August 1868. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

At last, the battered, exhausted, sick and starving exiles reached the end of their long and painful journey. Once they arrived outside the Prison City, they realized that 'Akká had no landing stage or dock, only a sea-gate, and passengers had to wade ashore in the shallow sea to land in the city.

The Governor of ‘Akká ordered that the 23 women in the party, nearly one-third of all the exiles, be carried ashore on the backs of the men.

'Abdu'l-Bahá categorically refused, out of respect for the dignity of the women, most especially His mother and sister.

'Abdu'l-Bahá was one of the first passengers to wade ashore. He procured a chair and organized the logistics of carrying all the women ashore while they were seated on a chair, in a dignified manner.

Through this gesture, 'Abdu'l-Bahá managed to wordlessly convey that, despite their status as prisoners and exiles, Bahá'ís treated women with respect.

The ship was bound for Cyprus, but Bahá'u'lláh was not allowed to disembark until the last member of His family had landed. After all the Bahá'ís had disembarked, they were counted and led through the streets of the penal colony.

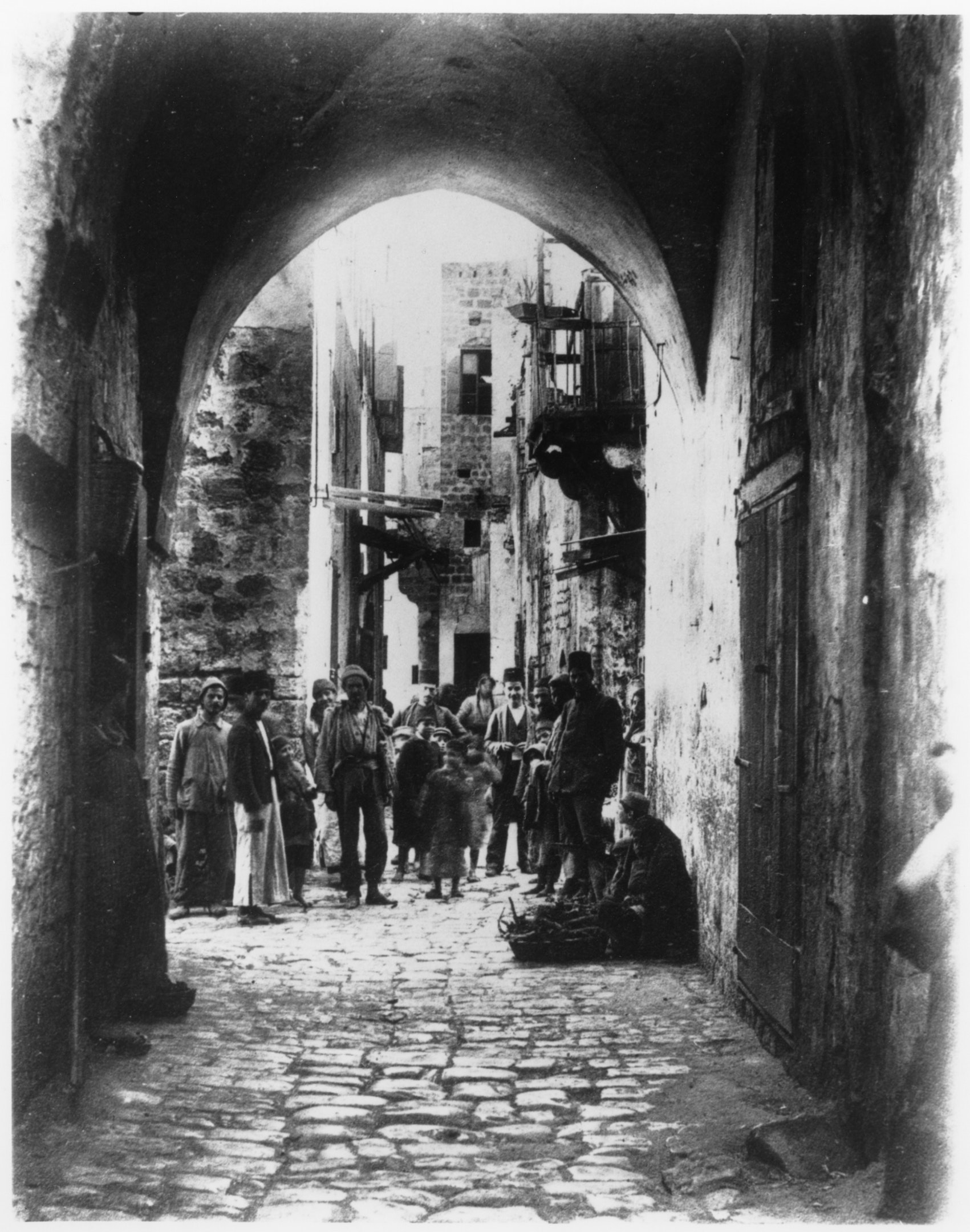

A street scene in ‘Akká, c. 1914. Bahá'í Media Bank.

Bahíyyih Khánum was appalled by what awaited the exiles once they set foot in 'Akká.

At the time, ‘Akká was a city with a population of close to 9,000 people. 'Akká was a prison city, the worst penal colony in the Ottoman Empire, and the people imprisoned there were most dangerous or most troublesome criminals—murderers, political detainees, troublemakers.

But the inhabitants were little better.

A large crowd of ‘Akká residents had assembled to watch the exiles and the “God of the Persians” arrive.

Wild rumors had preceded the Bahá'ís’ arrival, and the townspeople had been told the followers of Bahá'u'lláh were infidels, criminals, and sowers of sedition, evil men and women, all deserving to be treated cruelly.

Their reaction to the Bahá'í exiles’ arrival was threatening and aggressive.

They surrounded the Bahá'ís and screamed, hurled insults, they swore at them, mocked them, and yelled out curses in Arabic, filling the exhausted and miserable exiles with fresh misery. The Greatest Holy Leaf understood what they were saying and recounted:

Some said that we were to be put in the dungeons and chained; others that we were to be thrown into the sea. The most horrible jests and jeers were hurled at us as we were marched through the streets to this dreadful prison.

They had just traveled from the other end of the Ottoman Empire and were terrified of the unknown that awaited them in 'Akká, unsure of their fate or the fate of their loved ones.

1920s photograph of a view of the courtyard inside the Most Great Prison. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2023.

The Greatest Holy Leaf, contemplating that moment of her arrival in her last place of exile at the age of 24 poignantly said, when she was interviewed about this episode some 50 years later:

Imagine, if you can, the overpowering impression made by all this upon the mind of a young girl, such as I was then. Can you wonder that I am serious, and that my life is different from those of my countrywomen?

The life of the Greatest Holy Leaf would never be the same after this last, and worst of all exiles, due to the conditions of the sailing journeys, their traumatic, insult-filled arrival into the city, and the despicable conditions of the barracks in the Prison City.

'Akká changed everything.

Bahá'u'lláh’s arrival in the Most Great Prison also marked a great turning point in the life of 'Abdu'l-Bahá.

Upon arriving in 'Akká, Bahá'u'lláh told His Son:

Now I concentrate on My work of writing commands and counsels for the world of the future, to thee I leave the province of talking with and ministering to the people. Servitude is the essence of worship. I have finished with the outer world, henceforth I meet only the disciples.

Life would never be the same for the Holy Family.

View of the stairway leading to the ‘Akká prison within the citadel, c. 1901, where the exiles would have entered the barracks. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank.

The exiles were led through the dirty, dank, narrow streets of 'Akká to the Citadel which functioned as barracks for the Ottoman army, and would be their prison for the next two years. Once they entered, the doors slammed shut behind them and the huge iron bolts thrown closed.

Bahíyyih Khánum recalled in an interview:

Of my own experience perhaps this is the most awful. The horrible sufferings of the voyage had reduced me almost to the point of death. Upon that came the seasick- ness.

This was the Greatest Holy Leaf’s first impression of the Most Great Prison, when she fainted for the first time:

I cannot find words to describe the filth and stench of that vile place. We were nearly up to our ankles in mud in the room into which we were led. The damp, close air and the excretions of the soldiers combined to produce horrible odours. Then, being unable to bear more, I fainted.

As Bahíyyih Khánum fell to the ground, Bahá'ís around her caught her before she fell. There was nowhere to safely put her down. Nearby, a man was weaving a mat for the Ottoman soldiers. Someone grabbed the mat and placed it on the ground and laid the Greatest Holy Leaf on it.

The mat weaver had been moistening his leaves in a pool of water on the mud floor. In order to revive the Greatest Holy Leaf, a Bahá'í dipped a cloth in the dirty water and squeezed it onto her lips, but the water was so foul that Bahíyyih Khánum fainted again.

In the end, the Greatest Holy Leaf’s family could only use the water to refresh her face, and she was finally revived enough to climb the stairs up to their quarters.

The Holy Family’s cell was filled with mud to their ankles, preventing anyone from lying down, and what little plaster remained on the ceiling was peeling off.

Portrait of Mírzá Mihdí, The Purest Branch, son of Bahá’u’lláh dating back to Edirne, two years before his death in 1868. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank.

Mírzá Mihdí, Bahíyyih Khánum’s younger brother—known as the Purest Branch—had the habit along with many of the prisoners, of climbing narrow stairs leading to the rooftop of the barracks.

The roof was an ideal vantage point, where the prisoners could enjoy spectacular views of majestic Mount Hermon to the northeast, and the pure blue of the Mediterranean to the West, as well as a refreshing sea breeze at the end of a sweltering summer day.

There, the Purest Branch would spend long hours in prayer and meditation, communing with God while pacing back and forth.

This rooftop had a fatal flaw, a rectangular unprotected sky-light in the middle of the roof near the kitchens, which Mírzá Mihdí was aware of, and kept track of by counting his steps.

In the late afternoon of 22 June 1870, Bahá'u'lláh informed Mírzá Mihdí that he would not be needed that day to copy Tablets, so the Purest Branch climbed to the rooftop around twilight and began chanting the matchless verses of Bahá'u'lláh’s Qaṣídiy-i-Varqá’íyyih, His heavenly poem from Kurdistán.

Mírzá Mihdí was transported into a state of such spiritual ecstasy that he did not keep track of the skylight and fell through, impaling himself on an open wooden crate on the floor 10 meters (34 feet) below.

Mírzá Mihdí’s body crashed with a deafening sound on the crates below the skylight, alerting all the Bahá'ís. Bahá'u'lláh came out of His room and the believers ran to the sound.

Bahá'u'lláh reached His injured son and asked what happened, and Mírzá Mihdí told his Father he had forgotten to count his steps on the roof.

The crate had pierced Mírzá Mihdí’s ribs and he was bleeding profusely.

Mírzá Mihdí fell very close to the cell which Bahíyyih Khánum shared with Ásíyih Khánum.

His companions tore the clothes off his battered body and carried him to his room, and Bahá'u'lláh called for an Italian physician, who was unable to treat the Purest Branch.

Bahíyyih Khánum saw Ásíyih Khánum struggling to embrace her youngest son’s bloodstained body before losing consciousness. Mírzá Mihdí reached out to hold his unconscious mother in his arms, despite the pain of the move.

Top two photographs: Two views of the narrow stairs leading to the rooftop of the Most Great Prison. Source: Reflections on the Bahá'í Writings: The Great Sacrifice of the Purest Branch;

Bottom left: The rooftop skylight through which Mírzá Mihdí fell on 22 June 1870. Source: Bahá'í Media;

Bottom right: The original exposed stone that covered the ground when Mírzá Mihdí fell 10 meters (30 feet) through the skylight in the roof onto a wooden crate, the stairs to the roof are visible in the background. Source: Bahá'í Media.

Slowly dying from his wounds, weak, and in a tremendous amount of pain, Mírzá Mihdí lay on his bed perfectly attentive to all his visitors, fellow exiles who came to sit and stand by his side, attending to his every need. He greeted them all warmly, apologizing about being forced to lie down in their presence, and was kind, caring and polite to all.

Áqá Ḥusayn-i-Áshchi describes Mírzá Mihdí’s last hours:

It is not possible for anyone to visualize the measure of humility and self-effacement and the intensity of devotion and meekness which the Purest Branch evinced in his life.

Ásíyih Khánum, Bahíyyih Khánum, and 'Abdu'l-Bahá were utterly distraught and 'Abdu'l-Bahá entered the presence of Bahá'u'lláh with tears-filled eyes, begging Him to heal His brother. Bahá'u'lláh replied to Him:

O my Greatest Branch, leave him in the hands of his God.

Bahá'u'lláh entered Mírzá Mihdí’s room and, after dismissing everyone, remained alone with His dying son for an hour. Before Mírzá Mihdí died, Bahá'u'lláh asked him:

Áqá, what do you wish, tell Me.

Instead of asking his Father to spare his life, Mírzá Mihdí replied:

I wish the people of Bahá to be able to attain Your presence.

And Bahá'u'lláh responded to his dying son:

And so it shall be. God will grant your wish.

In a prayer revealed in honor of Mírzá Mihdí, Bahá'u'lláh heartbreakingly proclaims:

Glorified art Thou, O Lord, my God! Thou seest Me in the hands of Mine enemies, and My son bloodstained before Thy face, O Thou in Whose hands is the kingdom of all names.

Mírzá Mihdí passed away twenty-two hours after his fall, on 23 June 1870. When he had breathed his last breath, Bahá'u'lláh was heard lamenting:

Mihdí! O Mihdí!

As Mírzá Mihdí was dying, he bled profusely from his mouth, his thigh was so shattered from his fall that his clothes had to be torn away from his body.

It was the Greatest Holy Leaf, despite the intense pain of her grief, who had the presence of mind to safeguard and preciously keep these holy relics, the bloodstained clothing of her younger brother, the youngest son of Bahá'u'lláh, relics which today, still, 150 years later, are preciously kept in the International Bahá'í Archives.

Left: A 1930s photograph depicting the section of the Muslim cemetery of 'Akká where the Shrine of Nabí Ṣáliḥ is located with a row of graves including that of Mírzá Mihdí. Source: Bahá'í Media.

Right: The original headstone of Mírzá Mihdí's grave in the cemetery of Nabí Ṣáliḥ, before his remains were moved to their final resting place, in the company of his saintly mother Ásíyih Khánum, and sister, Bahíyyih Khánum on the slopes of Mount Carmel, and at the heart of the Administrative Order of the Bahá'í Faith. Source: Bahá'í Media

On 24 June 1870 in the afternoon, Mírzá Mihdí’s martyred body was placed in a casket which they purchased by selling Bahá'u'lláh’s only rug, and as the sounds of weeping and lamentation rose, it was carried out of the Most Great Prison on the shoulders of barracks guards, in a serene and majestic funeral procession joined by the notables of 'Akká.

Bahá'u'lláh’s youngest son was laid in a Muslim cemetery beyond the city walls, near shrine of Nabí Ṣáliḥ.

After Mírzá Mihdí’s funeral, at 17:00 (5:00 PM) on 24 June 1870, an earthquake hit Palestine. The tremors lasted three minutes and were felt around Palestine, from Jerusalem to 'Akká, Nazareth, and Gaza. Nabíl, the eminent Bahá'í historian and great teacher of the Faith confirmed the earthquake in Nazareth, where he was, and said that it had frightened people.

Bahá'u'lláh Himself confirmed the earthquake following Mírzá Mihdí’s burial in a Tablet of Visitation for the Purest Branch:

When thou wast laid to rest in the earth, the earth itself trembled in its longing to meet thee.

A gorgeous 1971 color photograph of Old 'Akká by Bernard Gotfryd, 101 years after Bahá'u'lláh left the Most Great Prison in November 1870 after an incarceration of two years and two months. Source: Library of Congress.

After the tragic death of her youngest son, Ásíyih Khánum was inconsolable.

Because of the constraints of their imprisonment in the barracks, Bahíyyih Khánum and Ásíyih Khánum were heartbroken at the fact they could not leave the prison and bury their beloved Mírzá Mihdí.

She wept almost incessantly until Bahá'u'lláh kindly assured her that God had accepted her beloved Mírzá Mihdí’s martyrdom and that pilgrims would soon be able to attain His presence, that mankind might be quickened. It was the only thing that could console Ásíyih Khánum, and her weeping ceased.

After its catastrophic performance in the Crimean War of 1854-1856, the Ottoman army was reorganized. New army regulations, were issued in August 1869 under Hüseyin Avni Páshá, the Minister of National Defense and army recruitment was reformed in March 1870.

After these reforms of the Ottoman Army, ‘Akká became the site of new military activities and the barracks were filled with soldiers, housed in the city. Bahá'u'lláh protested at the crowding and problems produced by such an influx of troops, and in early November 1870, the Governor allowed Bahá'u'lláh, His family and the exiled Bahá'ís to leave the barracks in order to live in the city, under house arrest and surveillance.

Mírzá Mihdí’s ardent prayer on his deathbed, and Bahá'u'lláh’s promise to him were about to be fulfilled: Bahá'í pilgrims would soon attain Bahá'u'lláh’s presence freely.

Bahíyyih Khánum’s life in 'Akká had begun.

This image of the façade of the house of ‘Údí Khammár is a modern photograph from Wikimedia Commons, but was heavily photoshopped to remove the parked cars, street signs and numerous electrical lamps and cables, in an attempt to artificially recreate the 19th century house Bahá'u'lláh moved in. Original unedited image: Wikimedia Commons.

Four months after the martyrdom of Mírzá Mihdí, the barracks had been requisitioned to house an influx of Ottoman soldiers and the Greatest Holy Leaf and the Holy Family were moved into the city of 'Akká.

It was a small step toward some semblance of freedom after two years in the Most Great Prison. Ottoman guards would watch over them for the first year, during which the Holy Family would be moved four times, from house to house, wherever there was space available.

The first year of the Greatest Holy Leaf’s life in 'Akká was hectic, as the family moved to three different houses in 'Akká, ending with the house of ‘Údí Khammár in September 1871 after ‘Údí Khammár himself moved into his recently-completed mansion named Bahjí (Delight), 2 kilometers (1.5 miles) north of ‘Akká in the countryside.

The illustration depicts not the murders, but how the murders acted as a spark that lit a conflagration in ‘Akká. The explosion in the background starts in the vicinity of the neighborhood where the murders took place, the photograph at the center is from Saladin street, near Lion’s gate, where Siyyid Muḥammad and Kaj-Kuláh lived. Original photograph from David S. Rue, Door of Hope page 37.

By late 1871 – early 1872, the three Covenant-breakers in 'Akká, Siyyid Muḥammad and his two minions, had firmly turned the people of 'Akká against Bahá'u'lláh and the Bahá'ís and Bahá'u'lláh secluded Himself in the House of ‘Údí Khammár.

The situation became so tense that 'Abdu'l-Bahá moved back into the family home from the Khán-i-Avámíd, where He had been living for the last two years.

During Bahá'u'lláh’s brief period of seclusion, the Covenant-breakers infiltrated the Bahá'í community, calumniated Bahá'u'lláh, and even corrupted the text of His Tablets to make them hostile to Islám.

By 22 January 1872, Bahá'ís could no longer stand the pain and suffering that the Covenant-breakers were inflicting on Bahá'u'lláh.

Seven misguided Bahá'ís, against the explicit instructions of Bahá'u'lláh, murdered Siyyid Muḥammad, Kaj-Kuláh, and Mírzá Riḍá-Qulí in an act unparalleled in the annals of the Faith.

A very unusual photograph of the house of Údí Khammár, from The Historical Development of Genoa Square in Acre Israel from the Seventh Century to the Present Day, page 125, a thesis by Amy Suzanne Hollander available on Bahá'í Library Online. The image’s native weathered and distressed quality is an appropriate illustration for a most distressing episode for the women of the Holy Family, particularly Ásíyih Khánum.

The reprisals after the murder of the three Covenant-breakers in the center of 'Akká were immediate.

Twenty-five Bahá'ís were arrested, including Bahá'u'lláh and 'Abdu'l-Bahá.

Bahá'u'lláh and His son Mírzá Muḥammád-‘Alí were moved to a room above the Khán-i-Shávirdí. The eastern wing of the Khán-i-Shávirdí was adjacent to the prison where 'Abdu'l-Bahá was taken and shackled.

Ottoman officials arrived at the prison and demanded 'Abdu'l-Bahá hand over the keys for the house of ‘Údí Khammár, saying they needed to search the house for weapons.

Ásíyih Khánum and Bahíyyih Khánum were alone at home, the men having all been arrested, and 'Abdu'l-Bahá refused to give the officials the keys, but He agreed to accompany them so they would not frighten His mother and sister.

The Ottoman official forced 'Abdu'l-Bahá to walk from the prison in northeast 'Akká to the house of ‘Údí Khammár in the western part of the city with chains around His neck and feet, a total distance of about one kilometer (0.6 miles).

When they reached the house, 'Abdu'l-Bahá tried to hide the chains from His mother, but Ásíyih Khánum saw them and wept bitterly.

Bahá'u'lláh and 'Abdu'l-Bahá were released on 25 January 1872.

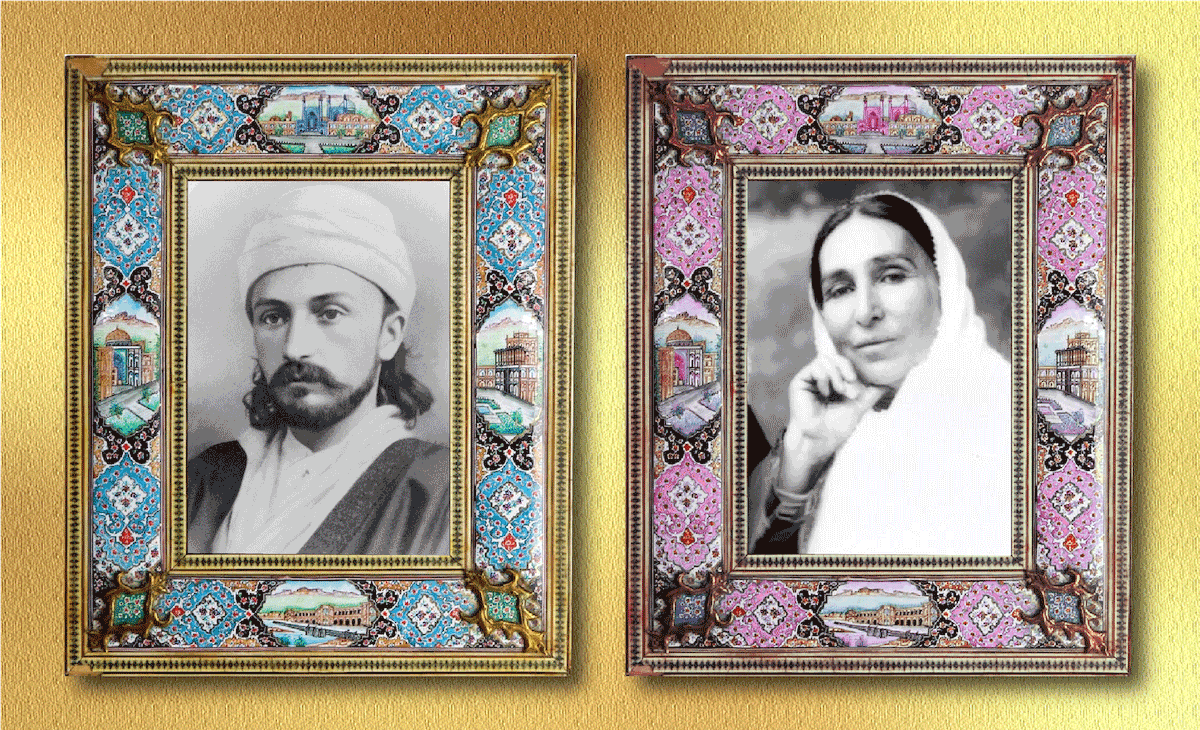

This is, by a few years on either side, what 'Abdu'l-Bahá and Munírih Khánum would have looked like when they were married at 28 and 26 years old. The photograph of 'Abdu'l-Bahá was taken four years before His wedding, in 1868. The photograph of Munírih Khánum was taken in the 1870s, the decade after her wedding. Source for the photo of 'Abdu'l-Bahá: 'Abdu'l-Bahá in America: 1912-2012; Source for the photo of Munírih Khánum: Bahá'í Media Bank.

Around 1870/1871, Bahá'u'lláh had a dream of a luminous young woman, the future bride of His eldest son, 'Abdu'l-Bahá.

Bahá'u'lláh sent a dedicated believer to Iṣfahán with a personal invitation to the young Fáṭimih Khánum, from a very devoted Bahá'í Family, and she and her brother arrived in 'Akká in September 1872.

Bahá'u'lláh, who had supervised Fáṭimih Khánum’s entire journey from Persia through Saudi Arabia to 'Akká, had asked 'Abdu'l-Bahá to be at the docks when she arrived, to make sure she disembarked safely.

It was night and 'Abdu'l-Bahá was concealed, and Munírih Khánum never found that He had even been there until later, when the Greatest Holy Leaf told her about it.

For six months, the marriage of Fáṭimih Khánum and 'Abdu'l-Bahá could not take place because there was no room for the young couple. During this time, Bahá'u'lláh bestowed a new name on Fáṭimih, calling her Munírih Khánum (Luminous).

On 8 March 1873, a little over one year after the murder of the three Covenant-breakers, Bahá'u'lláh’s neighbor, Ilyás 'Abbúd had been utterly won over, and become devoted to Bahá'u'lláh. He broke down the wall on his side of the house and created a room for 'Abdu'l-Bahá and Munírih Khánum, and offered it to Bahá'u'lláh as his wedding gift.

The wedding took place that very day.

The wedding of 'Abdu'l-Bahá and Munírih Khánum was very simple. 'Abdu'l-Bahá bride wore a white dress given to her by Bahíyyih Khánum, there were only seven guests, including the wife and daughters of Ilyás 'Abbúd, and for refreshments, they drank tea.

Munírih Khánum, 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s young wife, would be Bahíyyih Khánum’s close friend, support and confidante for the next 60 years.

This beautiful painting shows what 'Akká would have looked like at the time Bahá'u'lláh moved into the house of 'Abbúd, showing both His balconied room, and the sea view He so enjoyed. © Farvardin Daliri, used with permission. Source: Farvardin Daliri.

Ilyas 'Abbúd became extremely devoted to Bahá'u'lláh and 'Abdu'l-Bahá. Sometime in late 1873, feeling ill, he left the city and rented his spacious home, adjacent to the house of ‘Údí Khammár, to Bahá'u'lláh.

The Holy Family moved in quickly, and two doorways, on the upper and lower floors, were opened between the house of ‘Abbúd and the house of ‘Údí Khammár, fusing them into the single house they had originally been built as.

Bahá'u'lláh’s room was a large corner room with high ceilings, many windows offering a view of the Mediterranean Sea and a wraparound balcony.

'Abdu'l-Bahá and Munírih Khánum moved into the room Bahá'u'lláh had occupied in the house of ‘Údí Khammár, where He had revealed the Kitáb-i-Aqdas, and they began raising their family in what the Holy Family called “the small house.”

'Abdu'l-Bahá rented a reception room and office for Himself across Genoa square, where the house of ‘Údí Khammár was located.

'Abdu'l-Bahá used this office for his counseling work—a lot of which we would today refer to as social work—providing assistance to the people and officials of ‘Akká.

The house of ‘Abbúd allowed an increase of activity in the work of the Faith, providing enough room to receive pilgrims and visitors.

Greatest Holy Leaf devoted herself selflessly and untiringly to the needs of the family and to her Father’s Cause. From early morning until late at night she was occupied with household and other varied duties which to her were precious privileges. Her work was an unceasing prayer, her presence an inspiration to all.

Modern view of the renovated house of 'Abbúd, with Bahá'u'lláh’s beautiful and pleasant balcony clearly visible. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2024.

When the Holy Family moved into the house of 'Abbúd, the Greatest Holy Leaf’s household responsibilities increased. She was constantly busy with her many tasks, generally in the kitchen.

During the hottest times of year, members of the family or visitors would often find a servant coming to them, bearing a loving message and a cool beverage. The Greatest Holy Leaf’s attentions were constant, even when she was out of view, the welfare of all the people under her roof was always her primary concern.

No one was ever forgotten.

Bahíyyih Khánum managed every single detail of this large, complex household, which extended to giving loving advice to those wo needed it, or carefully and lovingly prepared food.

The Greatest Holy Leaf was the head of Bahá'u'lláh’s household, and she excelled at it.

Many people of rank, from officials to scholars, sought out Bahá'u'lláh’s presence despite the surveillance Bahá'u'lláh was under by the Ottoman authorities.

The Greatest Holy Leaf paid special attention to the needs of Bahá'u'lláh, and did everything in her power to protect and safeguard Him.

Eventually, the antagonism and hatred of the Covenant-breakers came to such a climax that even Bahíyyih Khánum’s gracious hospitality was often met with ingratitude and malicious slander.

But the Greatest Holy Leaf was never affected by these negative forces, and continued on, with serenity and patience.

“Utmost Joy” AI illustration generated by Pikaso AI.

It would be easy to think of the Greatest Holy Leaf as long-suffering, but this would deprive us of a dimension of the Greatest Holy Leaf’s life which was shared by the Báb, Bahá'u'lláh, 'Abdu'l-Bahá, and the Guardian: their ability to feel joy, find solace, and smile, even in the depths of spiritual agony.

It is an important dimension of the life of the Greatest Holy Leaf and in fact, one of my favorite passages about Bahíyyih Khánum come from an exquisite essay she wrote in 1982 for The Bahá'í World special edition of the fiftieth commemoration of Bahíyyih Khánum’s passing.

Bahíyyih Nakhjávání’s words are so beautiful and stirring, I wish to quote them in full here:

One of the characteristics of the Greatest Holy Leaf was her ability to endure suffering with the utmost joy reflected on her face.

After her passing Shoghi Effendi’s secretary wrote, “Even in the thick of the worst ordeals she would smile like an opening rose.” It is a smile that lingers with us still, a smile that looks at us with tenderness through the photographs.

Within this smile there is so much of radiance and sorrow, so much of understanding; it is a smile so deep that we might feel it penetrating our inmost hearts.

Just as her own heart retained the treasured traces of the heroic age of Bahá’í history, so our hearts too are revived and refreshed by “those smiles’ of hers exquisitely described by Shoghi Effendi which have been “forever and faithfully imprinted” there.

The Mansion of Bahjí and its surrounding gardens. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2024.

In 1877, 'Abdu'l-Bahá found the perfect place for Bahá'u'lláh in the countryside of 'Akká. It was called the Mansion of Mazra’ih.

Mazra'ih was a lovely little mansion with a stream surrounded by gardens, about 6.5 kilometers (4 miles) away from ‘Akká.

Two years later, in the summer of 1879, the inhabitants of the countryside of 'Akká fled an epidemic of plague, and ‘Údí Khammár and his family, abandoned his beautiful, palatial Mansion, which 'Abdu'l-Bahá was able to rent for Bahá'u'lláh.

This was what would come to be known as the Mansion of Bahjí, and would be Bahá'u'lláh’s last and most splendid home.

When ‘Údí Khammár had built the Mansion, he had been inspired to engrave a deeply significant Arabic phrase above the door which read:

Greetings and salutations rest upon this Mansion which increaseth in splendour through the passage of time. Manifold wonders and marvels are found therein, and pens are baffled in attempting to describe them.

Once Bahá'u'lláh moved into the Mansion of Bahjí in September 1879, these prophetic words would be fulfilled time and again.

The Mansion of Bahjí was spacious, richly designed, well-equipped, surrounded by a delightful grove of fragrant lemon and orange trees, and a large, beautiful pond.

Beyond the Mansion, the large garden was surrounded by a high wall, and it was closer to 'Akká than Mazra’ih, only 3,5 kilometers (2 miles) to the northeast.

A means of travel unavailable to women of the Holy Family in the Holy Land at the end of the 19th century: a beautiful white donkey photographed in Cairo, Egypt in 1899. Photograph by Keystone View Company. Library of Congress.

In 1877, Bahá'u'lláh moved to the Mansion of Mazra’ih, a profound improvement in His living conditions. Bahá'u'lláh had been deprived of greenery for 9 years in the Most Great Prison and 'Akká, and now He lived surrounded by nature. Mazra’ih was very close to 'Akká in modern terms: it was located 6.5 kilometers (4 miles) north.

But for the women of the Holy Family, and really, for any women in 19th century Palestine living within the city walls of 'Akká, it might as well have been in another country.

Why was it so impossible for women to travel such a short distance?

It is important to note that Ásíyih Khánum would have been prohibited from traveling because of her physical frailty, so these travel options would only apply to Bahíyyih Khánum.

Donkeys were the primary means of travel.

That is, in fact, how Bahá'u'lláh travelled, always accompanied by a servant who frequently held a parasol to shield Bahá'u'lláh from the harsh sun.

Bahá'u'lláh would own two white donkeys, both gifts sent from Persia. The first donkey was very fast on his feet, and he was named Barq ("lightning"). When Barq died, the Persian Bahá'ís sent Bahá'u'lláh another white donkey, slower, who was aptly, and quite humorously named Ra'd (thunder).

But Bahá'u'lláh was a man.

No woman in 19th century Palestine could ride atop a donkey. It simply would have been outrageous, shocking, and most probably prohibited by that era’s decency standards, most particularly for Bahíyyih Khánum, of noble Persian blood and the only daughter of Bahá'u'lláh.

Another option for travel would have been a carriage, but there were only a handful of carriages in 'Akká at the time, and they were too expensive for the Holy Family. 'Abdu'l-Bahá had only rented a carriage for the special occasion of bringing Bahá'u'lláh out of the gates of 'Akká for the first time in 9 years.

There was an additional restriction for both of the above travel methods, and that is that in the 19th century, women had to be veiled in public at all times, and when traveling, they had to travel hidden from all male view.

That left really only a howdah erected on the dorse horse, a donkey, or a camel, and supported by a flat wooden base. These would have had to be built as the Holy Family did not own one, since the women never traveled.

And so given all these complexities, although we know that the Greatest Holy Leaf did travel to see Bahá'u'lláh, we do not know how often she had that chance, or how she traveled.

Bahá'u'lláh, however, always came to His cherished family in 'Akká.

During the last 7 years of her life, from 1879 to 1886, Bahá'u'lláh spent long stretches of time with His beloved Ásíyih Khánum in the house of ‘Abbúd during the winters. In the spring and summers, when they were separated while He lived in te countryside, Bahá'u'lláh revealed kind and loving Tablets for Ásíyih Khánum.

The front door of the house of ‘Abbúd. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, Copyright © Bahá’í International Community 2024.

Between 1873 and 1877, Bahá'u'lláh, Ásíyih Khánum, 'Abdu'l-Bahá, Bahíyyih Khánum, and Munírih Khánum all lived together in the house of ‘Údí Khammár.

In 1874, 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s first daughter was born and Bahíyyih Khánum became an aunt for the first time. The little girl’s name was Ḍíyá‘íyyih Khánum, and she would later be the mother of Shoghi Effendi.

By 1875, there were changes for the better in 'Akká. Ottoman officials had been brought in close contact to 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s stainless character and their attitude to Bahá'u'lláh and the Bahá'ís had been much improved.

Around 1875, work began on the aqueduct, at the request of Bahá'u'lláh. A kind and friendly governor, Aḥmad Big Tafwíq, asked the Blessed Beauty what service he could render Him and Bahá'u'lláh had suggested he begin repairing the aqueduct, the only source of fresh water in 'Akká, which had fallen into disrepair over the last 30 years.

The final resting place of Ásíyih Khánum, known as Navváb, Bahá'u'lláh’s perpetual consort, next to her beloved son Mírzá Mihdí, in the Monument Gardens on Mount Carmel, at the heart of the Administrative Order of the Bahá'í Faith. Source: Bahá'í Media Bank, © Bahá'í International Community 2024.

Ásíyih Khánum, from one of the wealthiest families of Mázindarán, had lived a very modest life.

She had married Bahá'u'lláh in 1832, around the age of 15, she had borne him seven children, six boys and one girl, Bahíyyih Khánum. Of the six boys, only two had reached adulthood, and Mírzá Mihdí had been martyred 16 years earlier when he fell through the open skylight on the roof of the barracks.

Ásíyih Khánum’s room in the house of ‘Abbúd was small, simple and bare, her narrow white bed was her divan during the day, and she had a small table on which she placed her prayer books and Holy Books, pen case, writing papers, prayers and sometimes cut flowers. Ásíyih Khánum had a musical voice and chanted prayers with a wrapt expression on her smiling face.

Although a life filled with prolonged sufferings had weakened her, it is believed Ásíyih Khánum died a few days after a fall from a great height, in 1886.

Ásíyih Khánum passed away surrounded by Bahá'u'lláh, and her only two surviving children, her adored 'Abdu'l-Bahá, 42 and Bahíyyih Khánum, 40.

Her funeral was held with all the dignity required by her exalted position.

Muezzins and reciters of the Qur’án led the funeral cortège which included notables of ‘Akká, Christian and Muslim religious leaders, and schoolchildren, chanting verses and poems expressing their grief.

Bahá'u'lláh called Ásíyih Khánum, also known as Navváb “His companion in every one of His worlds,” testified that God had singled her out for His own Self.

The Holy Family’s sorrow was overwhelming, but, by far, Bahíyyih Khánum was the one who was most affected by Ásíyih Khánum’s passing. From her earliest childhood, she had been her saintly and sacrificial mother’s closest helper, spending all her time with her adored mother.

Ásíyih Khánum’s passing created a vacuum, a deep void in Bahíyyih Khánum’s life that nothing would ever fill, until her own passing.

The headstone over Mírzá Músá’s grave. Source: Bahaimedia.

The year after Bahíyyih Khánum lost her beloved mother Ásíyih Khánum, she lost another towering figure in her life: her beloved uncle, Bahá'u'lláh’s only true and faithful brother, Mírzá Músá.

Mírzá Músá-i-Núrí, titled Áqáy-i-Kalím (Master of Discourse), was Bahá'u'lláh’s younger brother by one or two years, born in either 1818 or 1819. In His eulogy of Mírzá Músá, 'Abdu'l-Bahá calls him Bahá'u'lláh’s “true brother,” who formed an extraordinary attachment to Bahá'u'lláh from the time he was a baby.

Mírzá Músá was utterly detached from material things, caring only to live according to the teachings of the Faith, and that, by his pure character, he shone “like a bright lamp” in the Holy Family, with, as his one supreme desire, to serve Bahá'u'lláh. Mírzá Músá was also deeply knowledgeable about all aspects of herbal medicine, which he practiced.

Shoghi Effendi called Ásíyih Khánum and Mírzá Músá the “twin pillars who, all throughout the various stages of Bahá’u’lláh’s exile from the Land of His Birth to the final place of His confinement, had demonstrated, unlike most of the members of His Family, the tenacity of their loyalty,” describing Mírzá Músá as Bahá'u'lláh’s “staunch and valued supporter, the ablest and most distinguished among His brothers and sisters, and one of the “only two persons who,” according to Bahá’u’lláh’s testimony, “were adequately informed of the origins” of His Faith.”

In honor of four-year-old Ḥusayn’s Effendi love of sightseeing, the tamáshá he endearingly pronounced tabashá, and his many adventures with his beloved grandfather Bahá'u'lláh in the Mansion of Bahjí, a wild grassy corner of the gardens near the Mansion with stately centuries-old olive trees. © Chad Mauger, all rights reserved, used with permission. Source: Flickr.

Just two years after the passing of her cherished mother and one year after the passing of her beloved uncle, Bahíyyih Khánum lost a third precious member of her immediate family in just three years: her wonderful and deeply special four-year-old nephew Ḥusayn Effendi, 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s only surviving son.

'Abdu'l-Bahá and Munírih Khánum’s son Ḥusayn Effendi was born in 1884, and was the delight of Bahá'u'lláh, spending long periods of time with His Grandfather in Bahjí.

Ḥusayn Effendi was a very special little boy, eager and vivacious and loved by all.

Bahá'u'lláh was very attached to Ḥusayn Effendi and often mentioned him in very sweet Tablets:

O Ḥusayn Effendi! Upon thee be God's peace and His favour. Yesterday We were in Junaynih. Some pomegranate was found and sent. We instructed Muṣṭafá, should he find something else in the city, to procure it and send it with the pomegranate. A small sum of money was also sent.

Background photo by Johannes Schenk on Unsplash.

Imprisonment in 'Akká had a deep impact on the heroic soul of Bahíyyih Khánum.

It is clear from Shoghi Effendi’s words in his 17 July 1932 tribute to the Greatest Holy Leaf after her passing that Bahíyyih Khánum’s contributions to the Bahá'í Faith and local community of Bahá'í exiles in 'Akká were deeply significant, although we do not have a detailed description of her role and responsibilities.

Shoghi Effendi stated that it was not until the Greatest Holy Leaf had been imprisoned with Bahá'u'lláh in the prison-city of 'Akká—this took place in the fall of 1870—that she had completely displayed the fullness of her spiritual power:

Not until, however, she had been confined in the company of Bahá’u’lláh within the walls of the prison-city of ‘Akká did she display, in the plenitude of her power and in the full abundance of her love for Him, more gifts that single her out, next to ‘Abdu’l‑Bahá, among the members of the Holy Family, as the brightest embodiment of that love which is born of God and of that human sympathy which few mortals are capable of evincing.

Shoghi Effendi also stated that it was in the abundance of her love for Bahá'u'lláh in that prison that her spiritual gifts, those that singled her out with 'Abdu'l-Bahá, her eldest Brother, among all the members of the Holy Family as the brightest embodiment of a love born of God.

Bahíyyih Khánum’s sympathy was a quality she alone possessed in the greatest possible measure, a quality which few people are capable of displaying. The Greatest Holy Leaf was also a wellspring of generosity and tender kindness.

One of the most important things to remember about the role of Bahíyyih Khánum in the Faith is that, in large part, her spiritual qualities were so powerful that she had a transformative effect on those around her and those who entered her presence, she was able to create unity in the community through her effect of her saintly character, and that those spiritual perfections imbued every word she spoke and every service she performed.

Overarching this was, of course, The Greatest Holy Leaf’s perfect understanding of the Dispensation of Bahá'u'lláh and His mission. Her commitment to serving Bahá'u'lláh and the Bahá'í Faith was the sole focus of her entire life. Bahíyyih Khánum banished every earthly attachment from her mind and heart, and stood by 'Abdu'l-Bahá, as they both dedicated their every energy in service to Bahá'u'lláh during the last two decades of His life.

View of the Mediterranean from the sea wall at 'Akká. Photograph by Jan Helebrant. Source: Jan Helebrant’s Flickr page. License: CC0 Public Domain Dedication.

The Greatest Holy Leaf’s spiritual attributes coalesced together to form a unique personality that could foster unity and cohesion in the Bahá'í community, both locally and internationally.

People of very high rank, even in the religious context, usually abuse their power, let it inflate their ego, and develop a sense of superiority.

The Greatest Holy Leaf’s personality was created in a way that the higher her rank in the Faith, the more responsibility she was given, the brighter her qualities of humility and selflessness shone.

She was a deeply social person with a quiet and unassuming disposition, and all these virtues together enhanced the prestige of her rank even more.

The Greatest Holy Leaf’s heart was so tender that it made every distinction of creed, class and colour disappear. She was so modest that she referred to herself as “this prisoner” in her letters on behalf of Shoghi Effendi.

She had a profound sense of balance and practical judgement that created order and grace all around her and in the household of the Holy Family.

View of the sea wall at 'Akká and the Mediterranean Sea. Photograph by Photograph by Jan Helebrant. Source: Jan Helebrant’s Flickr page. License: CC0 Public Domain Dedication.

Bahíyyih Khánum was a born leader.

Many of the Bahá'ís who met the Greatest Holy Leaf were attracted by the powerful atmosphere of her presence, a mixture of strong but gentle authority that gravitated around her.

Although the Greatest Holy Leaf had a strong will, she never exerted it on others, she was never heavy-handed, she never forced her way and never imposed her opinions on anyone. What she needed to accomplish, she did so gently and patiently, carefully and diplomatically and always smiling.

The approach of the Greatest Holy Leaf to leadership was a reflection of her innate sense of organization and her power to create unity. Her approach to anyone, Bahá'ís, local residents, pilgrims, persons of authority, or enemies of the Faith was always the same: respectful, sensitive, and patient.

In the words of Dr. Janet Khan:

She modeled a leadership style that exemplified nurturance, trust, and encouragement. She was a force for unity and understanding actively supporting and collaborating with the embryonic Spiritual assemblies.

The Greatest Holy Leaf was also a highly principled individual. Unity was important to her but not at the cost of the integrity of the Faith and the Bahá'í standard. She promoted the spiritual and administrative principles of the Faith, not compromise.

View of the sea wall at 'Akká from the Mediterranean. Photograph by Photograph by Jan Helebrant. Source: Jan Helebrant’s Flickr page. License CC0: Public Domain Dedication.

One of the Greatest Holy Leaf’s most remarkable characteristics was her willingness to accept and even embrace change and her ability to adapt to that change, and the new requirements it brought along.

When she transitioned from a wealthy child of the Persian aristocracy to an exile, she did so in a heartbeat. When Covenant-breaking became a constant in her life, she adapted to learning how she could heal the spiritual damage it was causing in the community. When Bahá'u'lláh passed away, she squarely stood by 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s side. After the Ascension of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, she immediately rallied around the new Guardian as his fiercest defender and strongest supporter. When the Guardian instituted the Bahá'í Administrative Order—a very difficult change for the old Bahá'ís to accept—she embraced it wholeheartedly and educated Bahá'ís on it through her innumerable letters.

The Greatest Holy Leaf was a decidedly modern, adaptable figure.

She did not cling to the past.

She was not passive.

She evolved as the Bahá'í Faith evolved, and she served exactly as the Faith needed to be served in the present moment, not how she had served it in the past.

The Greatest Holy Leaf was a realist, a pragmatist, she had a great understanding of history and religious history and she knew that time does not stay the same, new problems require new solutions. She adapted her language in her letters over the course of the ministries of 'Abdu'l-Bahá and Shoghi Effendi. In them, she spoke about different things, new circumstances, novel opportunities.

The Greatest Holy Leaf was the only member of the family of Bahá'u'lláh who saw both the Heroic Age and the Formative Age.

She helped steer the Bahá'ís, old and new, pliable and reticent, from the age of heroes and martyrs to the age of Local and National Spiritual Assemblies, from an age of father-figure Heads of the Faith such as Bahá'u'lláh and 'Abdu'l-Bahá, to the Guardian. In this, her link from one Bahá'í age to another, she fostered innovation and change in the attitude of the Bahá'ís and their communities.

She played a vital role in helping grow the Faith and its Administrative Order, particularly not only when she was at the headship of the Cause, but also after.

Bakckground photo: A modern-day aerial photograph of 'Akká. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Bahíyyih Khánum would spend the 'Akká years constantly attentive to Bahá'u'lláh’s everyday needs and managing the household of the Holy Family—at which she excelled.

One of her most precious services to both Bahá'u'lláh and 'Abdu'l-Bahá however, was how carefully she maintained good social relationships. This was a true protection for her Father and Brother.

Sometimes even the kindness of Bahíyyih Khánum could not change the hearts of some enemies.

When the Ottoman officials, their wives and their employees would spew forth constant wickedness, ungratefulness, and blind fanaticism, the Greatest Holy Leaf showered them with generosity, love, kindness, and patience. These people were so perverse that her kindness only exacerbated their jealousy and intensified their fears.

By contrast to the gloominess of the Bahá'í exiles in 'Akká, one of Bahíyyih Khánum’s enduring characteristics was her confident hope and deeply-rooted optimism, a frame of mind that found its source in her belief of the unconquerable power of the Bahá'í Faith and its ultimate victory. Nothing could tarnish the brightness of her saintly face, no calamity, no crisis, no matter how severe, could disturb her gracious and dignified composure.

It was during this time that the Greatest Holy Leaf rose to the rank of one of the most noble and exceptional figure ever associated with the ministry of Bahá'u'lláh.

Background image created with https://openart.ai/

In Part IV, we alluded only briefly to two sentences revealed by Bahá'u'lláh about His only daughter, the Greatest Holy Leaf, but in this Part, as Bahíyyih Khánum enters the fullness of her spiritual powers, it is time to take a closer look at the words of the Blessed Beauty.

Bahá'u'lláh revealed several excerpts about the station the Greatest Holy Leaf, and we have access to two, which were published in a compilation on excerpts by and about Bahíyyih Khánum. Because we have no dates of revelation for these excerpts, we have chosen to place them here.

Background photo from Freepik Premium.

In this first excerpt Bahá'u'lláh elevates the Greatest Holy Leaf to a rank towering above all women of her generation, a station unsurpassed by any other woman, and enters into great detail regarding her exalted rank:

Let these exalted words be thy love-song on the tree of Bahá, O thou most holy and resplendent Leaf: “God, besides Whom is none other God, the Lord of this world and the next!” Verily, We have elevated thee to the rank of one of the most distinguished among thy sex, and granted thee, in My court, a station such as none other woman hath surpassed. Thus have We preferred thee and raised thee above the rest, as a sign of grace from Him Who is the Lord of the throne on high and earth below. We have created thine eyes to behold the light of My countenance, thine ears to hearken unto the melody of My words, thy body to pay homage before My throne. Do thou render thanks unto God, thy Lord, the Lord of all the world.

How high is the testimony of the Sadratu'l-Muntahá for its leaf; how exalted the witness of the Tree of Life unto its fruit! Through My remembrance of her a fragrance laden with the perfume of musk hath been diffused; well is it with him that hath inhaled it and exclaimed: 'All praise be to Thee, O God, my Lord the most glorious!' How sweet thy presence before Me; how sweet to gaze upon thy face, to bestow upon thee My loving-kindness, to favour thee with My tender care, to make mention of thee in this, My Tablet—a Tablet which I have ordained as a token of My hidden and manifest grace unto thee.

Background photo from Freepik Premium.

In the second excerpt, Bahá'u'lláh offers kind words to His beloved daughter, enjoining unto her to be unmoved by the difficulties of life:

O my Leaf! Hearken thou unto My Voice: Verily there is none other God but Me, the Almighty, the All-Wise. I can well inhale from thee the fragrance of My love and the sweet-smelling savour wafting from the raiment of My Name, the Most Holy, the Most Luminous. Be astir upon God's Tree in conformity with thy pleasure and unloose thy tongue in praise of thy Lord amidst all mankind. Let not the things of the world grieve thee. Cling fast unto this divine Lote-Tree from which God hath graciously caused thee to spring forth. I swear by My life! It behoveth the lover to be closely joined to the loved one, and here indeed is the Best-Beloved of the world.

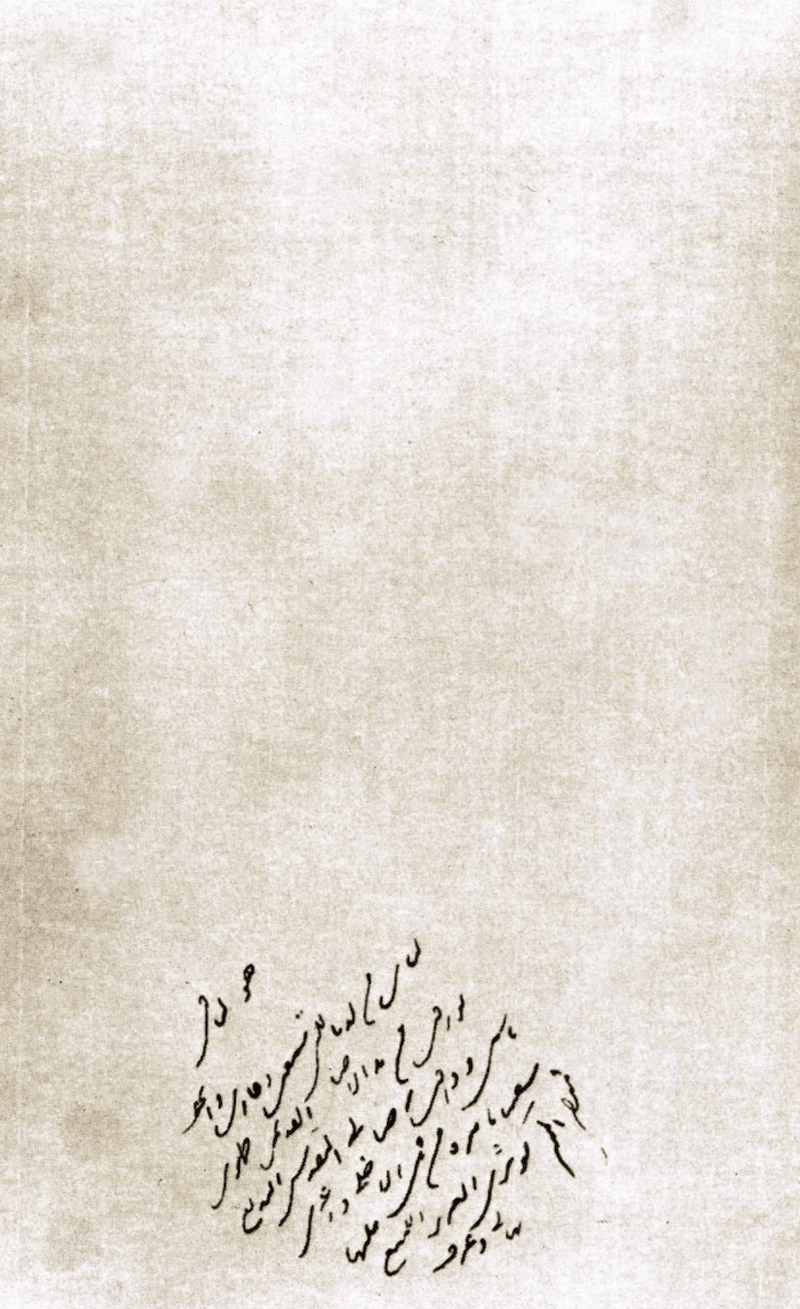

Facsimile of Bahá'u'lláh’s Tablet, in His Own handwriting, revealed in honor of the Greatest Holy Leaf. The text of this Tablet is carved and gilded around the base of the dome of her monument. Source: Bahá'í Sacred Relics.

The following Writing of Bahá'u'lláh is not an excerpt, it is a very short Tablet which He revealed in His Own Hand. This is the most famous of all of Bahá'u'lláh’s words about His saintly daughter because it is the one which the Guardian chose in 1932 to inscribe, carve, and gild forever upon the monument of the Greatest Holy Leaf on Mount Carmel:

This is My testimony for her who hath heard My voice and drawn nigh unto Me. Verily, she is a leaf that hath sprung from this preexistent Root. She hath revealed herself in My name and tasted of the sweet savours of My holy, My wondrous pleasure. At one time We gave her to drink from My honeyed Mouth, at another caused her to partake of My mighty, My luminous Kawthar. Upon her rest the glory of My name and the fragrance of My shining robe.

SOURCES FOR PART IV

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Lady Blomfield, The Chosen Highway, page 62.

Myron H. Phelps, The Master in ‘Akká, pages 64-65.

Bahá’u’lláh, Súriy-i-Ra’ís (Surah to the Chief).

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá’u’lláh: The King of Glory, pages 255-257.

Before 12 August 1868: Bahíyyih Khánum handles a difficult crisis

The Revelation of Baha’u’llah, Volume 2, Adib Taherzadeh, George Ronald, Oxford, 1983, pages 404-407.

Archeologists & Travelers in Ottoman Lands: Travel in the Ottoman Empire.

21 – 31 August 1868: The sea journey

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá’u’lláh: The King of Glory, pages 268-269.

Lady Blomfield, The Chosen Highway, pages 65-66.

Myron H. Phelps, The Master in ‘Akká, pages 70-72 and 75.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

The Life and Teachings of ‘Abbás Effendi, Myron Phelps, GP Putnams Sons, New York and London, 1904, PDF Edition from Bahá’í Library Online, page 55.

31 August 1868: From Haifa to the Prison City of ‘Akká

The Life and Teachings of ‘Abbás Effendi, Myron Phelps, GP Putnams Sons, New York and London, 1904, PDF Edition from Bahá’í Library Online, page 55.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá’u’lláh: The King of Glory, page 271.

The Chosen Highway, Lady Blomfield, Bahá’í Publishing Trust, Wilmette, Ill. 1975, page 66.

Myron H. Phelps, The Master in ‘Akká, pages 75-76.

31 August 1868: Setting foot in ‘Akká

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá’u’lláh: The King of Glory, pages 275-276.

Myron H. Phelps, The Master in ‘Akká, page 76-81.

The Chosen Highway, Lady Blomfield, Bahá’í Publishing Trust, Wilmette, Ill. 1975, page 66.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh Volume 3: ‘Akká, the Early Years 1868-1877, page 16.

Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees, Baharieh Rouhani Ma’ani, George Ronald, Oxford, 2013, pages 146-147.

The Life and Teachings of ‘Abbás Effendi, Myron Phelps, GP Putnams Sons, New York and London, 1904, PDF Edition from Bahá’í Library Online, pages 56-57.

The effect of arriving in ‘Akká on the Greatest Holy Leaf

The Life and Teachings of ‘Abbás Effendi, Myron Phelps, GP Putnams Sons, New York and London, 1904, PDF Edition from Bahá’í Library Online, page 56.

Lady Blomfield, The Chosen Highway, pages 64 and 66.

The Greatest Holy Leaf faints twice upon arrival

The Life and Teachings of ‘Abbás Effendi, Myron Phelps, GP Putnams Sons, New York and London, 1904, PDF Edition from Bahá’í Library Online, pages 56-58.

22 June 1870: Mírzá Mihdí’s tragic fall

Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees, Baharieh Rouhani Ma’ani, George Ronald, Oxford, 2013, page 150.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá’u’lláh: The King of Glory, pages 311-314.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh Volume 3: ‘Akká, the Early Years 1868-1877, pages 204-220.

Myron H. Phelps, The Master in ‘Akká, page 87.

David S. Ruhe, Door of Hope: The Bahá’í Faith in the Holy Land, page 31.

The Bahá’í World Volume XV (April 1968-1973), The Centenary of the Passing of Mírzá Mihdí, The Purest Branch 1848 – 1870, pages 159-163.

Shoghi Effendi, 5 December 1939 cablegram Blessed Remains Transferred to Mount Carmel published in This Decisive Hour.

23 June 1870: The sacrifice of the Purest Branch

Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees, Baharieh Rouhani Ma’ani, George Ronald, Oxford, 2013, page 150.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá’u’lláh: The King of Glory, pages 311-314.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh Volume 3: ‘Akká, the Early Years 1868-1877, pages 204-220.

Myron H. Phelps, The Master in ‘Akká, page 87.

David S. Ruhe, Door of Hope: The Bahá’í Faith in the Holy Land, page 31.

The Bahá’í World Volume XV (April 1968-1973), The Centenary of the Passing of Mírzá Mihdí, The Purest Branch 1848 – 1870, pages 159-163.

Shoghi Effendi, 5 December 1939 cablegram Blessed Remains Transferred to Mount Carmel published in This Decisive Hour.

The Bahá’í World, Volume 8, pages 255-256.

24 June 1870: The funeral of Mírzá Mihdí

Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees, Baharieh Rouhani Ma’ani, George Ronald, Oxford, 2013, page 150.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá’u’lláh: The King of Glory, pages 311-314.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh Volume 3: ‘Akká, the Early Years 1868-1877, pages 204-220.

Myron H. Phelps, The Master in ‘Akká, page 87.

David S. Ruhe, Door of Hope: The Bahá’í Faith in the Holy Land, page 31.

The Bahá’í World Volume XV (April 1968-1973), The Centenary of the Passing of Mírzá Mihdí, The Purest Branch 1848 – 1870, pages 159-163.

Shoghi Effendi, 5 December 1939 cablegram Blessed Remains Transferred to Mount Carmel published in This Decisive Hour.

23 June – 4 November 1870: After the martyrdom of Mírzá Mihdí

Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees, Baharieh Rouhani Ma’ani, George Ronald, Oxford, 2013, page 152.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá’u’lláh: The King of Glory, page 314.

David S. Ruhe, Door of Hope: The Bahá’í Faith in the Holy Land, page 33.

Wikipedia: Tanzimat.

Encyclopaedia Britannica: The Tanzimat reforms (1839–76) – The 1875-78 crisis.

Bloomsbury Collections: Handan Nezir Akmeṣe, Editor, The Birth of Modern Turkey: The Ottoman Military and the March to World War I: An introduction.

Erik Jan Zürcher, The Ottoman Conscription System, 1855-1914, International Review of Social History 43 (1998), pages 438, 440: PDF Download link from Cambridge.

Wikipedia (in Turkish): Hüseyin Avni Pasha.

4 November 1870 – September 1871: The first three houses

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá’u’lláh: The King of Glory, page 315.

David S. Ruhe, Door of Hope: The Bahá’í Faith in the Holy Land, pages 34-35, 205 and 222.

22 January 1872: The murder of the three Covenant-breakers

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá’u’lláh: The King of Glory, pages 317-321 and 325-326.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh Volume 3: ‘Akká, the Early Years 1868-1877, pages 224-226 and 235-236.

The Chosen Highway, Lady Blomfield, Bahá’í Publishing Trust, Wilmette, Ill. 1975, page 251.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá’u’lláh: The King of Glory, pages

David S. Ruhe, Door of Hope: The Bahá’í Faith in the Holy Land, page 37.

22 January 1872: Ásíyih Khánum and Bahíyyih Khánum see ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in chains

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá’u’lláh: The King of Glory, pages 325-326.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh Volume 3: ‘Akká, the Early Years 1868-1877, pages 224 and 235-236.

The Chosen Highway, Lady Blomfield, Bahá’í Publishing Trust, Wilmette, Ill. 1975, pages 254-255.

Balyuzi, H.M. Bahá’u’lláh: The King of Glory, pages 320-332, Taherzadeh, Adib. The Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh Volume III: ‘Akká, the Early Years (1868 – 1877) pages 234-236, Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By. Details about ‘Abdu’l-Bahá in chains from Lady Blomfield: The Chosen Highway. Calculations about the distance between the Limán and the house of ‘Údí Khammár are my approximative measurements on Google Maps, tracing the most direct path between the Limán and the house of ‘Údí Khammár along the pedestrian alleys indicated on the map.

8 March 1873: ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and Munírih Khánum’s wedding

Maani, Baharieh Rouhani. Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees: An in-depth study of the lives of women closely related to the Báb and Bahá’u’lláh, pages 309-327.

Munírih Khánum, Memoirs and Letters, pages 24-25.

The Chosen Highway, Lady Blomfield, Bahá’í Publishing Trust, Wilmette, Ill. 1975, pages 84-90.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá’u’lláh: The King of Glory, pages 338-350.

Episodes in the life of Munírih Khánum, page 28.

DATE

Maani, Baharieh Rouhani. Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees: An in-depth study of the lives of women closely related to the Báb and Bahá’u’lláh, page 318.

Late 1873: The house of ‘Abbúd

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá’u’lláh: The King of Glory, pages 334-335.

David S. Ruhe, Door of Hope: The Bahá’í Faith in the Holy Land, page 47.

The Greatest Holy Leaf’s responsibilities in the house of ‘Abbúd

The School of Adversity: A Brief Study of the Life of Bahíyyih Khánum, Anise Rideout, published in Baha’i Magazine Dedicated to the New World Order, Volume 25, Number 4 (July 1934), pages 120-121.

The Greatest Holy Leaf’s smile

Nakhjávání, Bahíyyih, The Greatest Holy Leaf: A reminiscence, published in The Bahá’í World Volume 18 (1979 – 1983): Part Two: The Commemoration Of Historic Anniversaries: The Life and Service of the Greatest Holy Leaf, pages 68 to 74.

1877 – 1879: Mazra’ih and Bahjí

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá’u’lláh: The King of Glory, pages 357-359.

David S. Ruhe, Door of Hope: The Bahá’í Faith in the Holy Land, pages 83-85.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh Volume 3: ‘Akká, the Early Years 1868-1877, pages 414-415.

1877 – 1879: Travel for women in Ottoman Palestine in the 19th century

Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees, Baharieh Rouhani Ma’ani, George Ronald, Oxford, 2013, pages 113-114 and 154-155.

Taherzadeh, Adib. The Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh, Volume 4 (Mazra‘ih & Bahjí, 1877–1892) page 105.

1873 – 1892: The Holy Family grows

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá’u’lláh: The King of Glory, pages 334-361.

David S. Ruhe, Door of Hope: The Bahá’í Faith in the Holy Land, page 47 and 83-90.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh Volume 3: ‘Akká, the Early Years 1868-1877, pages 274-282.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh Volume 4: Mazra’ih and Bahjí 1877-1892, pages 1 and 6-8.

1886: The passing of Ásíyih Khánum, the Greatest Holy Leaf’s cherished mother

Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees, Baharieh Rouhani Ma’ani, George Ronald, Oxford, 2013, pages 114-120 and 155-156.

1887: The passing of Mírzá Músá, the Greatest Holy Leaf’s adored uncle

Gail, Marzieh, Dawn Over Mount Hira, pages 94-95.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá’u’lláh: The King of Glory, pages 137.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By, Excerpt 1 and Excerpt 2.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh Volume 3: ‘Akká, the Early Years 1868-1877, page 361.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Memorials of the Faithful: His Eminence Kalím (Mírzá Músá)

‘Abdu’l-Hussayn Fikri, Ḥawáríyyú Ḥaḍrat-i-Bahá’u’lláh, p. 14.

Shoghi Effendi, Bahá’í Administration.

The Bahá’í World Volume III, (1928-1930), page 92

1888: The passing of Ḥusayn Effendi, the Greatest Holy Leaf’s beloved nephew

Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees, Baharieh Rouhani Ma’ani, George Ronald, Oxford, 2013, pages 321-324.

David S. Ruhe, Door of Hope: The Bahá’í Faith in the Holy Land, page 51.

After 1870: The fullness of the Greatest Holy Leaf’s spiritual power

Bahá’í Administration, 17 July 1932 letter from Shoghi Effendi regarding the passing of Bahíyyih Khánum to the Bahá’ís of the West.

Prophet’s Daughter: The Life and Legacy of Bahíyyih Khánum, Outstanding Heroine of the Bahá’í Faith, Janet A. Khan, Bahá’í Publishing Trust, Wilmette, 2005, pages 41-43.

The Greatest Holy Leaf’s personality

Rank and Station: Reflections on the Life of Bahíyyih Khánum, Janet A. Khan, published in Journal of Bahá’í Studies, 17:1-4, pages 1-26 Ottawa: Association for Bahá’í Studies North America, 2007, pages 22-23.

The Greatest Holy Leaf’s leadership style

Rank and Station: Reflections on the Life of Bahíyyih Khánum, Janet A. Khan, published in Journal of Bahá’í Studies, 17:1-4, pages 1-26 Ottawa: Association for Bahá’í Studies North America, 2007, pages 22-23.

The Greatest Holy Leaf’s attitude to change

Rank and Station: Reflections on the Life of Bahíyyih Khánum, Janet A. Khan, published in Journal of Bahá’í Studies, 17:1-4, pages 1-26 Ottawa: Association for Bahá’í Studies North America, 2007, pages 23-24.

The services of the Greatest Holy Leaf

Bahá’í Administration, 17 July 1932 letter from Shoghi Effendi regarding the passing of Bahíyyih Khánum to the Bahá’ís of the West.

Prophet’s Daughter: The Life and Legacy of Bahíyyih Khánum, Outstanding Heroine of the Bahá’í Faith, Janet A. Khan, Bahá’í Publishing Trust, Wilmette, 2005, pages 41-43.

Three excerpts from the Writing of Bahá’u’lláh about the Greatest Holy Leaf

Bahíyyih Khánum: The Greatest Holy Leaf by Bahá’u’lláh, Abdu’l-Bahá, Shoghi Effendi, and Bahíyyih Khánum, compiled by Research Department of the Universal House of Justice Haifa: Bahá’í World Centre Publications (1982): From the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh, Selections 1 and 2, pages 3-4.

We preferred thee and raised thee above the rest

Bahíyyih Khánum: The Greatest Holy Leaf by Bahá’u’lláh, Abdu’l-Bahá, Shoghi Effendi, and Bahíyyih Khánum, compiled by Research Department of the Universal House of Justice Haifa: Bahá’í World Centre Publications (1982): From the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh, Selections 1 and 2, pages 3-4.

I can well inhale from thee the fragrance of My love

Bahíyyih Khánum: The Greatest Holy Leaf by Bahá’u’lláh, Abdu’l-Bahá, Shoghi Effendi, and Bahíyyih Khánum, compiled by Research Department of the Universal House of Justice Haifa: Bahá’í World Centre Publications (1982): From the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh, Selections 1 and 2, pages 3-4.

This is My testimony for her who hath heard My voice and drawn nigh unto Me

Bahá’í Sacred Relics: Baha’u’llah’s Tablet to Bahiyyih Khanum, the Greatest Holy Leaf. Published 8/07/2010.

![]()

Early August 1868: Surrounded

Early August 1868: Surrounded