Written and illustrated by Violetta Zein

This part covers the life of the Greatest Holy Leaf at the age of 17 in 1863.

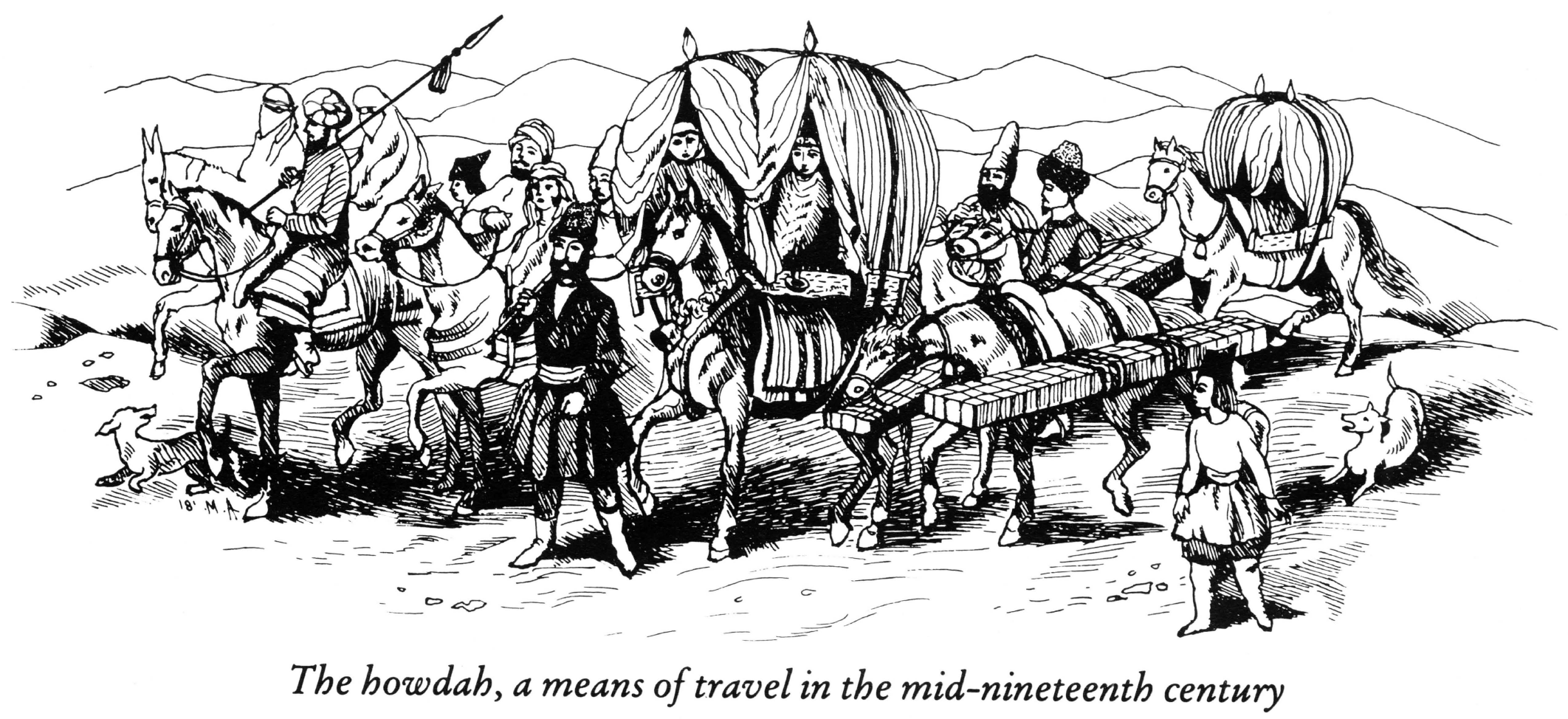

Persian howdah. You can clearly see the cloth covering and the wooden base, as well as the two compartiments seating one person each. There were seven such howdahs in Bahá'u'lláh's caravan. The Dawn-Breakers.

Baghdad was the city that Bahíyyih Khánum had known since she was seven years old.

It had been her home, through wonderful times and through profound spiritual tests of Covenant-breaking, and it was the place she had spent almost her entire childhood.

Baghdad held her childhood memories and experiences, which had turned her into the servant of Bahá'u'lláh she had now become, utterly devoted to the Blessed Beauty, and now she was leaving Baghdad, never to return.

She was leaving people she had come to know and love, dear friends, and she was heading into the unknown, to a foreign place, where they spoke Turkish, a language she did not know.

Bahíyyih Khánum would have to cope, along with her delicate mother Ásíyih Khánum, with the rigors of traveling 110 days on a litter placed on the back of a mule, jostled along rough terrain for hours and hours on end, day after day for three months.

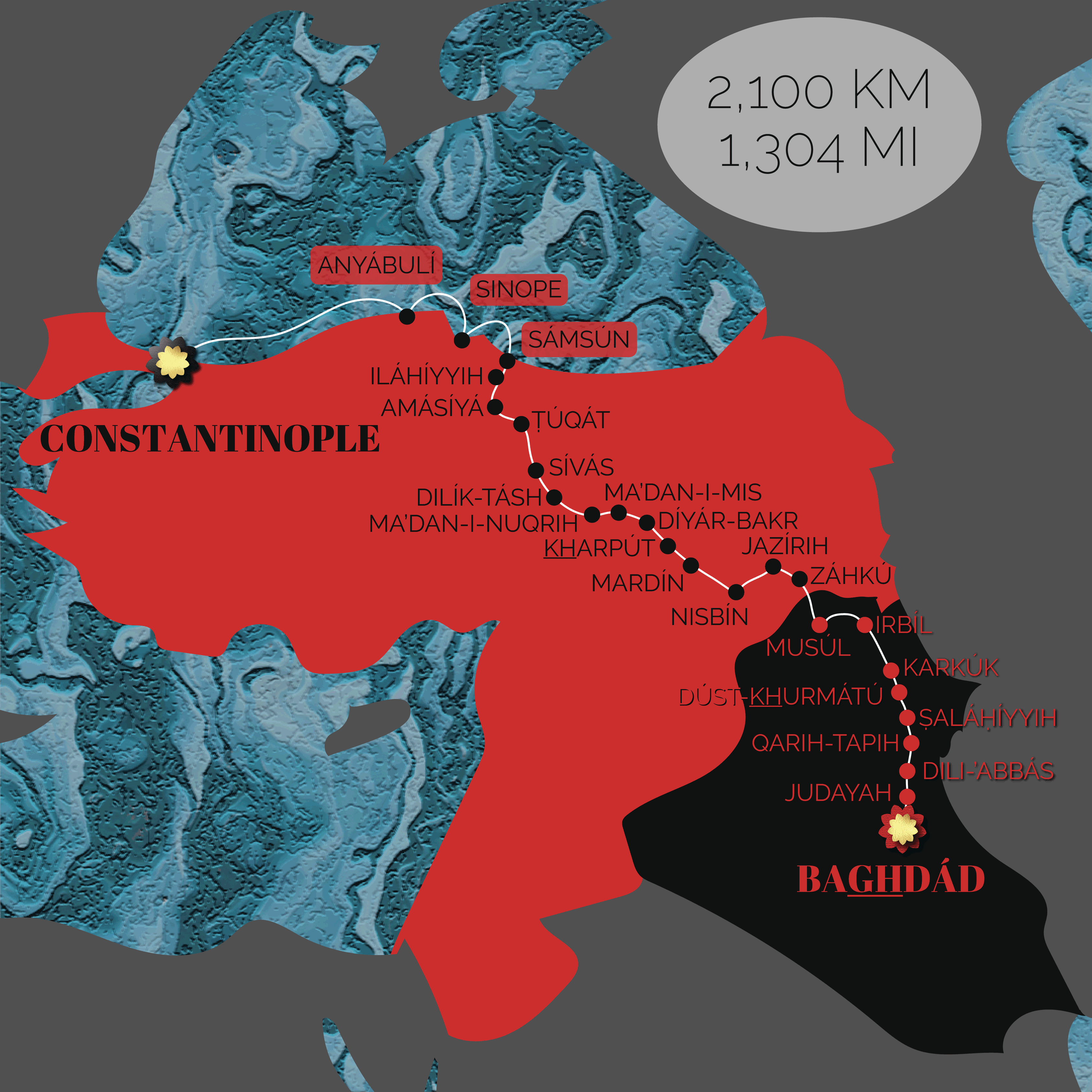

Map indicating only a small fraction of the stops made by the Greatest Holy Leaf’s caravan between Baghdad and Constantinople, from 3 May to 16 August 1863. Source: H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 180.

We have no testimony from the Greatest Holy Leaf about her experience of the long march of Bahá'u'lláh, the Holy Family and the Bahá'í exiles from Baghdad to Istanbul, but she was present the entire time, and so this story is recounted here in order to give an idea of what she lived through at the age of 17, as a young women entering her prime.

The caravan accompanying Bahá'u'lláh to Istanbul was large.

There were 50 mules, 10 guards and their officer on horses, a total 60 animals that would have to be fed every day. There were 14 howdahs carried on mules, topped by parasols, in which the women and children traveled, which included the Greatest Holy Leaf.

Bahá'u'lláh, 'Abdu'l-Bahá, the officers, and some men traveled on horseback, some traveled on mules, but most men walked beside the caravan.

The caravan would most often stop along the banks of Tigris and Euphrates rivers and their tributaries, where the exiles set up their camps and the travelers could bathe, and at times in caravanserais.

Two-thirds of Bahá'u'lláh’s journey to Istanbul was overland to Sámsún on the Black Sea, approximately 1,600 kilometers (990 miles) and the last third from Sámsún to Istanbul, or about 800 kilometers (490 miles), was by sea.

The caravan stopped, set up camp, rested, and packed up to continue their march 10 times between Mosul and Kirkúk, a distance of only 173 kilometers (107 miles). On this segment, the caravan only averaged 17 kilometers (10 miles) a day, but they usually covered 40 to 50 kilometers (25 to 30 miles) a day before setting up camp.

Bahá'u'lláh, the Holy Family, and the exiles stopped between 60 and 65 times before Sámsún, the port on the Black Sea where they would board a ship to Istanbul, and they repeated this exhausting process over, and over, again for three months over rough terrain in the full heat of the Arabian/Anatolian summer.

It would be an utterly exhausting ordeal, but most especially for Bahíyyih Khánum and the women.

Altogether, 54 people—including 12 women—traveled with Bahá'u'lláh to Istanbul.

An Arab horse caravan with howdahs, sometime before 1899. Painter: Albert Pasini. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Bahá'u'lláh traveled majestically.

Most of the time, Bahá'u'lláh traveled in His howdah which He shared with Ásíyih Khánum.

Ḥájí Maḥmúd led the mule carrying Bahá'u'lláh’s howdah, and two believers walked on either side.

On approach of a village or town, 'Abdu'l-Bahá would bring Bahá'u'lláh His horse, and take His place in the howdah with Ásíyih Khánum, reversing the process when they left a town.

Bahá'u'lláh would then ride out to meet the officials and notables who invariably came out to greet Him. Námiq Páshá’s order to welcome Bahá'u'lláh was followed by local government officials all along His route.

In many of the cities and towns where He stopped, Bahá'u'lláh would be met by a delegation before His arrival, and accompanied for some distance by another similar delegation upon His departure.

These delegation sometimes comprised Governors of regions, Administrators of larger divisions, Deputies representing the Sháh of Persia, local Governors, shaykhs, muftis, judges and other local government officials.

In some places, villagers organized festivities in His honor, prepared food, and made sure Bahá'u'lláh was comfortable, showing Him great reverence.

The local inhabitants who saw Bahá'u'lláh travel stated they had never witnessed anyone like Him, majestic in His journey, generous with His bounty, and hospitable to all.

Here are six Bahá'ís who had roles during the long journey from Baghdad to Istanbul.

Photo 1: Mírzá Áqá Ján, Bahá'u'lláh's amanuensis and personal attendant.

Photo 2: Áqá Riḍá, cook for the caravan.

Photo 3: Mírzá Maḥmúd-i-Káshání, cook for the caravan.

Photo 4: Áqá 'Abdu'l-Ghaffár, interpreter for the caravan.

Photo 5: Ustád Muḥammad-'Alíy-i-Salmání, Bahá'u'lláh's barber, in charge of supplies and the howdah of the wife of Mírzá Yaḥyá.

Photo 6: Áqá Ḥusayn Áshchí, a young boy, apprentice cook, porridge cook, and attendant to the ladies of the caravan.

The journey to Istanbul was such a logistically complex endeavor and everyone had a role to play in order for them to complete their long, difficult, and trying journey.

Bahá'u'lláh had personal attendants, including a barber and a man who carried a lantern in front of His howdah when they marched at night.

One Bahá'í, Áqá 'Abdu'l-Ghaffár was the only Turkish-speaker he served as the caravan’s interpreter.

There were cooks and a broth-maker, as well as a young boy whose responsibility it was to serve the ladies in the caravan, there were people responsible for pitching tents, a muleteer, those who groomed the animals, and one Bahá'í, Siyyid Ḥusayn was in charge of Namíq Páshá's horse, which He had asked Bahá'u'lláh to deliver to his son in Istanbul.

There were also exiles in charge of the fodder and barley for the animals, one Bahá'í who accompanied 'Abdu'l-Bahá in His search for provisions, two men who took care of the purchases of anything that was needed along the way, one man was in charge of supplies, two had the responsibility for providing coffee and water pipes, another two were responsible for the tea and the samovar.

This magnificent view of the Great Zab River near Irbíl on the way to Mosul in Iráqí Kurdistán is perhaps what Bahá'u'lláh would have seen from the caravan. Photographer: jamesdale10. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Bahá'u'lláh, Ásíyih Khánum, 'Abdu'l-Bahá, the Greatest Holy Leaf, Mírzá Mihdí and their fellow-exiles left Baghdad on 3 May 1863 and first traveled to Firayját, five kilometers (three miles) away from Baghdad as the sun was setting.

They stayed in Firayját for six days, then continued, along the banks of the Tigris to Judaydah, then Dilí-‘Abbás, in a verdant plain where they arrived on 12 May. They stayed for two nights in Ṣaláḥíyyih, a small town beside a mountain by the Diyáláh river where the local notables held a small festival in honor of Bahá'u'lláh.

Leaving Ṣaláḥíyyih, they traveled by night, as they often would during the long journey, and entered Turkish territory in Judaydah, then Karkúk where they stayed in an orchard. In Karkúk, Bahá'u'lláh met with the son of Shaykh Muḥyi’d-Dín of Khániqayn, the man in whose honor Bahá'u'lláh had revealed the Seven Valleys.

After Karkúk, the caravan arrived in Irbíl on 28 May 1863, on the Feast of ‘Íd al-Aḍhá (The Feast of the Sacrifice), one of the holiest days in the Islámic calendar. Leaving Irbíl, the caravan passed by a Christian village, then arrived in Mosul, where Mírzá Yaḥyá rejoined the caravan.

They were about to leave Iraq and cross over into modern-day Turkey. Bahá'u'lláh and His family were now farther than they had ever been from their native country.

This is a 1851/1852 photograph of an encamped tent in Egypt, headed for the Sennar, by Félix Teynard, a French photographer. The tents in the background help us form an image of the kind of tent Bahá'u'lláh and His Family were in when He cooked this sweet dish for His loved ones. Source: The Met.

The Holy Family’s march towards Istanbul took four months of bad weather and days with no food, and many of the exiles were women and many small children. There were very few happy memories of the journey except for the day when Bahá'u'lláh shared his recipe from Kurdistán.

One day, after a long and cold journey, 'Abdu'l-Bahá had managed to find some bread, rice and milk.

Bahá'u'lláh took these ingredients and used them to make a type of pudding by boiling them together with a little sugar. He would tell His family that this was the only warm food he ever ate during his time on Sar-Galú, the mountain where He lived in total isolation during His first year in Kurdistán.

After Bahá'u'lláh had prepared the pudding, it was shared with all the exiles in the caravan.

Recalling this fond memory several decades later, Bahíyyih Khánum would say:

Such times as these were moments of pleasure; but there was always present a feeling of apprehension—as though a sword were hanging over our heads.

Ever since Bahá'u'lláh revealed the Tablet of the Holy Mariner in March 1856, the Greatest Holy Leaf had known immense tests were awaiting her Father and her entire family.

A panorama of the city of Márdín. Photographer: Ben Bender, 2013. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The caravan had now entered Turkey.

On the way to Zákhú, stopping by the foot of a small mountain, the caravan encountered hostile and abusive Kurds who threw rocks at them, refused to sell them food and denied them night guards. This was one of the only truly unpleasant experiences of the three-month journey.

After leaving Zákhú, the caravan stopped in Jazírih, then Niṣíbín, an ancient Roman city. They pitched their tents in a delightful spot by the torrential Jaghjagh river, a tributary of the Euphrates.

Making their way through Anatolia, the eastern region of Turkey, the caravan passed through Diyár-Bakr, the largest Kurdish city in Turkey, then continued on to Ma'dan-i-Mis (Copper Mine), and camped at the foot of a steep castle-topped mountain, then traveled from Ma'dan-i-Mis to Khárpút, the caravan navigated its way through a narrow road in a mountain pass when Bahá'u'lláh nearly died.

Ḥájí Maḥmúd lost his hold on the rein of the mule carrying Bahá'u'lláh’s howdah, the mule slipped, lost its footing and started to slide down the precipice. The accident happened so fast that Bahá'u'lláh’s companions watched in horror, powerless to stop the inevitable.

Suddenly, miraculously, the mule regained its balance and slowly came to a halt. As Bahá'u'lláh’s companions registered that He was safe, the sheer joy of that realization filled their eyes with tears. After the averted calamity, an extremely large container of rosewater broke, filling the mountain air with its fragrance.

On the way to Khárpút, the caravan crossed villages ravaged by famine. It was difficult to feed their mules and horses, who began losing weight and having difficulty walking. Arriving in Khárpút, they were welcomed very generously by the Acting Governor-General, ʻIzzat Páshá, who loved Bahá'u'lláh and wanted to rend Him service, called on Him and offered 10 car-loads of rice, ten sacks of barley, 10 sheep, several baskets of rice, several bags of sugar, and many pounds of butter as a gift.

The exiles spent a week in Khárpút, then traveled to the last stages before the end of their overland journey: Ma'dan-i-Nuqrih, Sívás, Dilík-Tásh, Amásiyá, Túqát, where they pitched their tents in a large orchard and Iláhíyyih. At one of the stops, the exiles found that all the houses were underground because of the harsh winter months.

1870 photograph showing an approach to Sámsún with a view of the Black Sea, seven years after Bahá'u'lláh arrived here. Photographer: Dimitri Ermakov. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

On 7 August 1863 they were in view of the Black Sea, Bahá'u'lláh revealed a momentous Tablet called the Lawḥ-i-Hawdaj (Tablet of the Howdah), also known as Lawḥ-i-Sámsún (Tablet of Sámsún).

Bahá’u’lláh, the Holy Family, and the band of devoted exiles at their side, arrived in the port city of Sámsún on the shores of the Black Sea, after a grueling 1,600-kilometer (990 mile) journey.

The arduous—and the longest—overland part of the long march was now over.

It had lasted 110 exhausting days—infinitely more exhausting for the Greatest Holy Leaf, the women and the children.

In Sámsún, the exiles waited a week for an Ottoman steamer to take them to Istanbul.

Photo of Sinope by Bjørn Christian Tørrissen. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Photo of Anyábulí by Dosseman. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

At last, on 13 August 1863, the steamer arrived in Sámsún.

The exile’s trunks, goods, and horses were loaded, Bahá'u'lláh and His Family were taken aboard in one boat, and the rest of His companions in a second boat.

They cast off anchor, and sailed along the coast of Turkey, arriving in Sinope the next day, 14 August, where they stopped for a few hours.

On 15 August, they dropped anchor in Anyábulí, and arrived in Istanbul the next day, 16 August, after sailing 700 kilometers (430 miles) on the Black Sea.

1880 - 1893 photograph of the the mosque of Khirqiy-i-Shárif (Hırka-yi Şerif), close to where was located the house of Shamsí Big, the first house occupied by Bahá'u'lláh in Constantinople. Photographers: Abdullah Fréres. Source: Library of Congress

As He disembarked the ship, Bahá'u'lláh was welcomed to Istanbul with great honor by Shamsí Big who had been appointed by the government to entertain Him and His family and followers.

Shamsí Big led Bahá'u'lláh and the Holy Family to his home near the Kirqíy-i-Sharíf (Hırka-i Şerif) mosque, where they stayed for their first month in Istanbul, from August to September 1863.

Shamsí Big was a courteous, generous, and attentive host, and he hired two cooks, whom the exiles willingly helped prepare the meals.

Shamsí Big’s two-story home was unfortunately not large enough to accommodate Bahá'u'lláh’s large family comfortably, and it became obvious rather quickly that they would need more spacious lodgings.

The Mosque of Nişancı Mehmet Paşa, 30 meters (98 feet) from the house of Vísí Páshá, directly across the street. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

After a month spent in uncomfortably tight conditions in the house of Shamsí Big, Bahá'u'lláh and the Holy Family moved to the house of Vísí Páshá, near the mosque of Sulṭán Muḥammad-i-Fátiḥ—also known as the Blue Mosque.

The new house was a palatial residence. The house boasted a Turkish bath, a spacious garden, and rainwater collecting facilities.

Like the Most Great House in Bagdad, it had both a bírúní, public men’s quarters, and an andarúní, women’s inside quarters—where the Greatest Holy Leaf would have lived—both of which were three stories high and well-equipped.

Bahá'u'lláh’s quarters were on the first floor of the andarúní, with the rest of family occupying the other two stories. 'Abdu'l-Bahá lived on the first floor of the bírúní, Bahá'u'lláh’s companions on the second floor, and the third floor was turned into a kitchen and store.

Those responsible for Bahá'u'lláh’s third exile:

Top left: Sulṭán ‘Abdu’l-‘Azíz, Sulṭán of the Ottoman Empire. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Top right: Mírzá Ḥusayn Khán, Persian Ambassador in Constantinople. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Bottom left: ‘Alí Páshá, Prime Minister to the Sulṭán. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Bottom right: Fu’ád Páshá, Foreign Minister to the Sulṭán. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Ḥájí Mírzá Ḥusayn Khán, the Persian Ambassador in Istanbul, who had plotted against Bahá'u'lláh when He was in Bagdad, was on the offensive again.

Under constant pressure from the Persian government, he slandered Bahá'u'lláh to the chief ministers of Sulṭán ‘Abdu’l-‘Azíz, ‘Alí Páshá and Fu’ád Páshá, who pressured the Sulṭán until he decided to banish Bahá'u'lláh to Edirne, on the European continent and in the farthest reaches of the Ottoman empire at the harshest time of year, in the dead of winter.

Mírzá Ḥusayn Khán deeply resented Bahá'u'lláh’s independent and dignified behavior, refusing to beg for political favors, and arranged for rumors about Him to spread in government circles, according to which Bahá'ís were:

A mischief to all the world and destructive of treaties and covenants; they are a source of trouble and baleful to all lands; they have kindled a fire and consumed the earth; and though they be outwardly fair-seeming yet are they deserving of every chastisement and punishment.

In the winter of 1863, just four months after His arrival in Istanbul, Bahá'u'lláh received the edict for His third exile.

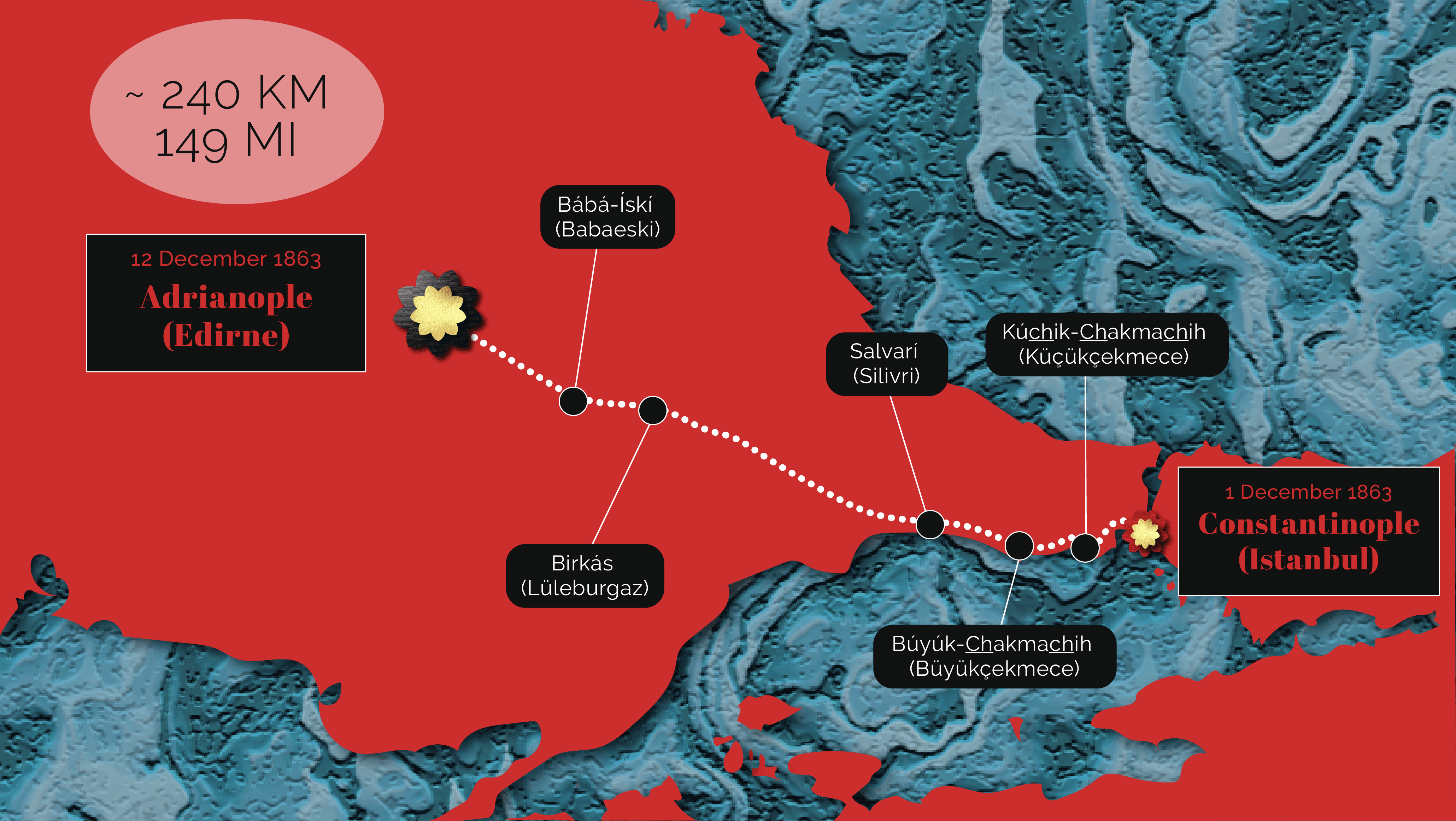

Map of the journey of the Holy Family from Constantinople to Adrianople based on the place names mentioned by Shoghi Effendi in God Passes By, page 161. © Violetta Zein.

The Ottoman officer in charge of the journey was 'Alí Big Yúz Báshí, and Bahá'u'lláh, His family, and twelve of His followers, including women and children, left Istanbul on the snowy morning of 1 December 1863.

The 240 kilometers (149 miles) of bleak and frozen territory separating them from Edirne (Edirne) would be the shortest journey towards an exile, but also, the worst of all.

The exiles traveled in the middle of the coldest winter in forty years, dressed in thin, summer clothing, and battered by snow, ice, and rain.

The wells and rivers along their route were frozen, and the only way of obtaining water was to melt ice with a torch. The conditions of their travel were undignified, some of the exiles were made to ride in wagons normally reserved for carrying goods, while others had to ride on animals, exposed to the freezing elements, their belongings piled in an ox-cart.

A Turkish ox-wagon in 1935. The exiles and their belongings were taken to Edirne in wagons such as this one. Source: Library of Congress.

The exiles reached their first stop, Kúchik-Chakmachih (Küçükçekmece), 14.5 kilometers (9 miles) from Istanbul, after a three-hour journey in the late afternoon of 1 December 1863. Upon their arrival, the official responsible for their journey, Yúz-Bashi, found lodgings for Bahá'u'lláh.

The next day, 2 December, they traveled a half-day, covering 17 kilometers (11 miles), they reached Búyúk-Chakmachih (Büyükçekmece) around noon, where the exiles were housed in the home of a Christian.

Traveling by night, the exiles covered 30 kilometers (19 miles), to Salvarí (Silivri), where they arrived on 3 December. Bahá'u'lláh and His family stayed in the home of another Christian, and the rest of the exiles being housed elsewhere with the cooking utensils. They left the town at midnight, pushing forward, in the frozen pouring rain and the bitter cold, towards their next stop.

We have no information on the stops the exiles made between Salvarí and Birkás (Lüleburgaz), which are separated by 90 kilometers (60 miles), but given that they generally traveled 20 kilometers (12.5 miles) a day, it is likely they stopped at least twice or three times before reaching Birkás.

After Birkás, the next stop was Bábá Ískí (Babaeski) on 11 December 1863.

They traveled the final 55 kilometers (34 miles), arriving in Edirne the next day.

On 12 December 1863, Bahá'u'lláh, His Family and the small band of exiles arrived in Edirne at the very western edge of the Ottoman empire.

The journey had nearly killed them all.

The bridge at Büyükçekmece, Turkey, which the Greatest Holy Leaf crossed in December 1863, on her way from Istanbul to Edirne. Bahá'í Media Bank © Bahá'í International Community.

Bahíyyih Khánum called the journey “the most terrible experience of travel thus far.”

The winter so cold that 90-year-olds could not remember a colder one. Animals froze to death in the snow in Turkey and Persia, entire regions were covered in ice for days, and in Díyár-Bakr a river remained fully frozen for over a month.

The wells and rivers along their route were frozen, and the only way of obtaining water was to melt ice with a torch for hours before it could be thawed.

Heavy snow fell through most of their journey, the exiles had no proper winter clothing, and lacked food. Bahíyyih Khánum would later say:

It was a miracle that we survived it.

The Holy Family and exiles were even forced to travel by night at times.

All the exiles arrived in Edirne sick, “even the young and strong,” and 'Abdu'l-Bahá suffered frostbite during the journey, an immensely painful skin injury that occurs when the skin on a person’s hand or feet freeze in extremely low temperatures.

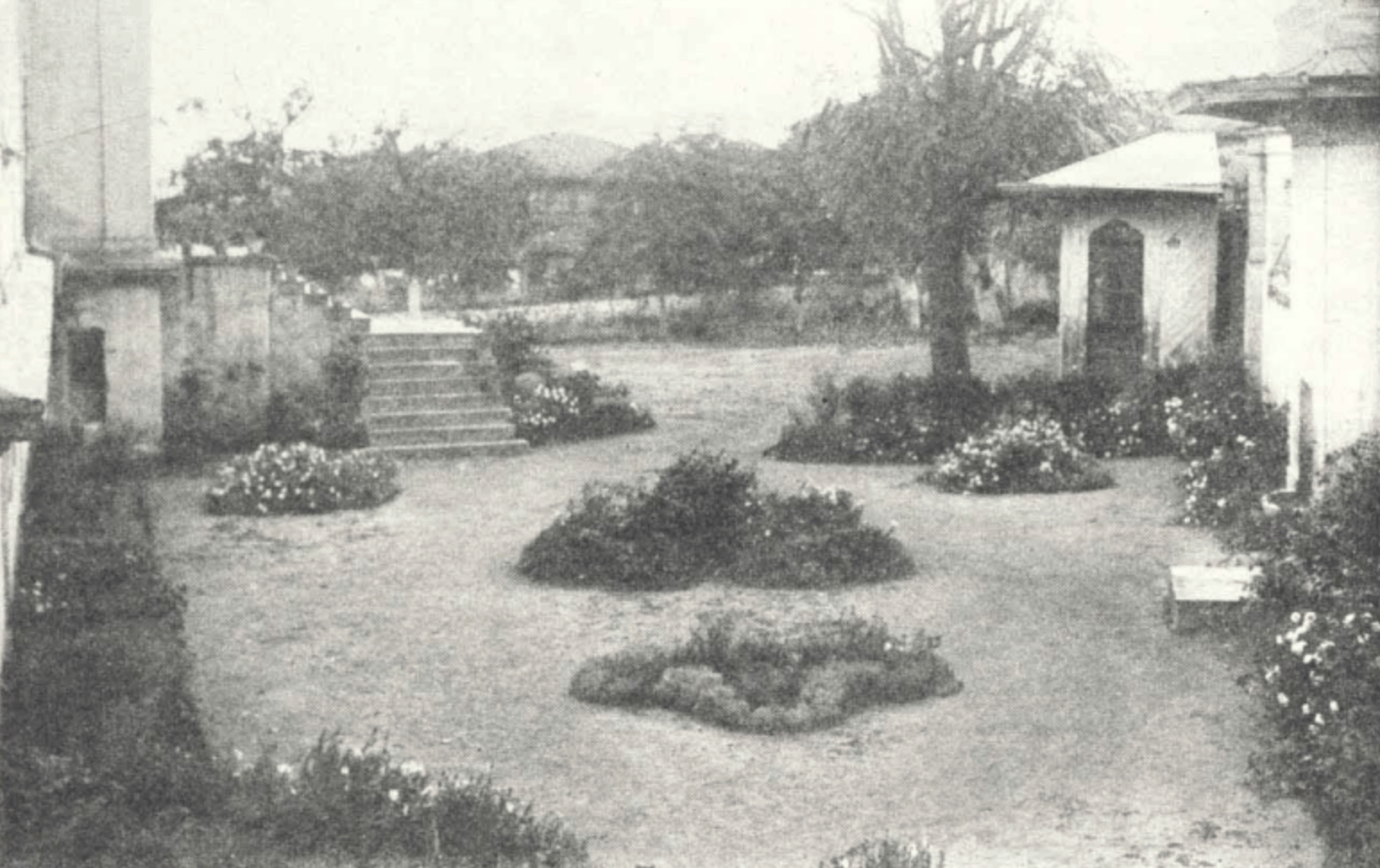

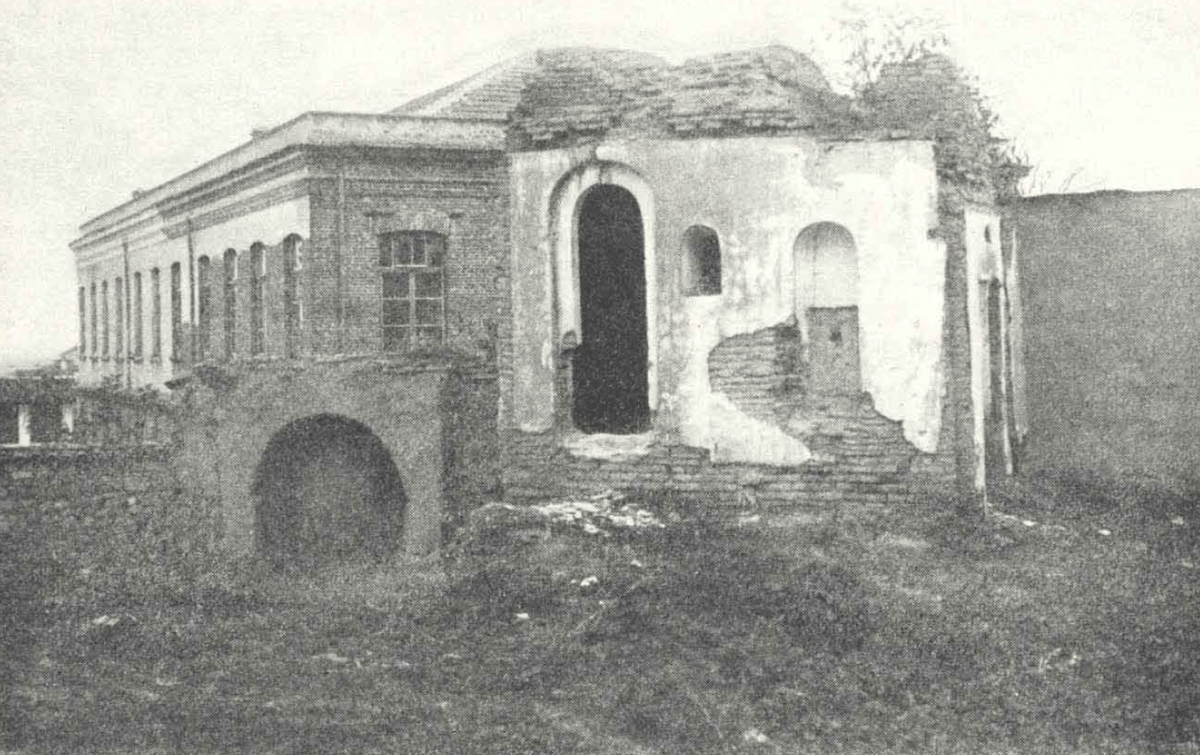

Site of the old Khán-i-'Arab Caravanserai in Edirne, where the Greatest Holy Leaf stayed when she first arrived on 12 December 1863. Source Bahá'í Media, originally from The Bahá'í World, Volume V (1932-1934), A Visit to Adrianople by Martha Root page 589.

When the exiles arrived in Edirne on 12 December 1863, they spent their first three days in a two-story caravanserai just outside of the city called the Khan-i-'Arab.

Then, the 11 members of the Holy Family were moved to a woefully inadequate house with just three rooms in the Murádíyyih neighborhood.

It was worse than a prison.

There were no comforts, it was surrounded by soldiers, they could only eat prison food, they were constantly cold and hungry.

But the worst part was the vermin.

Days were absolutely intolerable, but nights were much, much worse. The Holy Family was tormented by so much vermin that the Greatest Holy Leaf said “the house was swarming” with them.

Once the vermin made it absolutely impossible to sleep, 'Abdu'l-Bahá would light a lamp to somewhat intimidate them. Then, He would sing and laugh and try to cheer up His family.

After a week, the Holy Family was moved to another inadequate house in the same neighborhood.

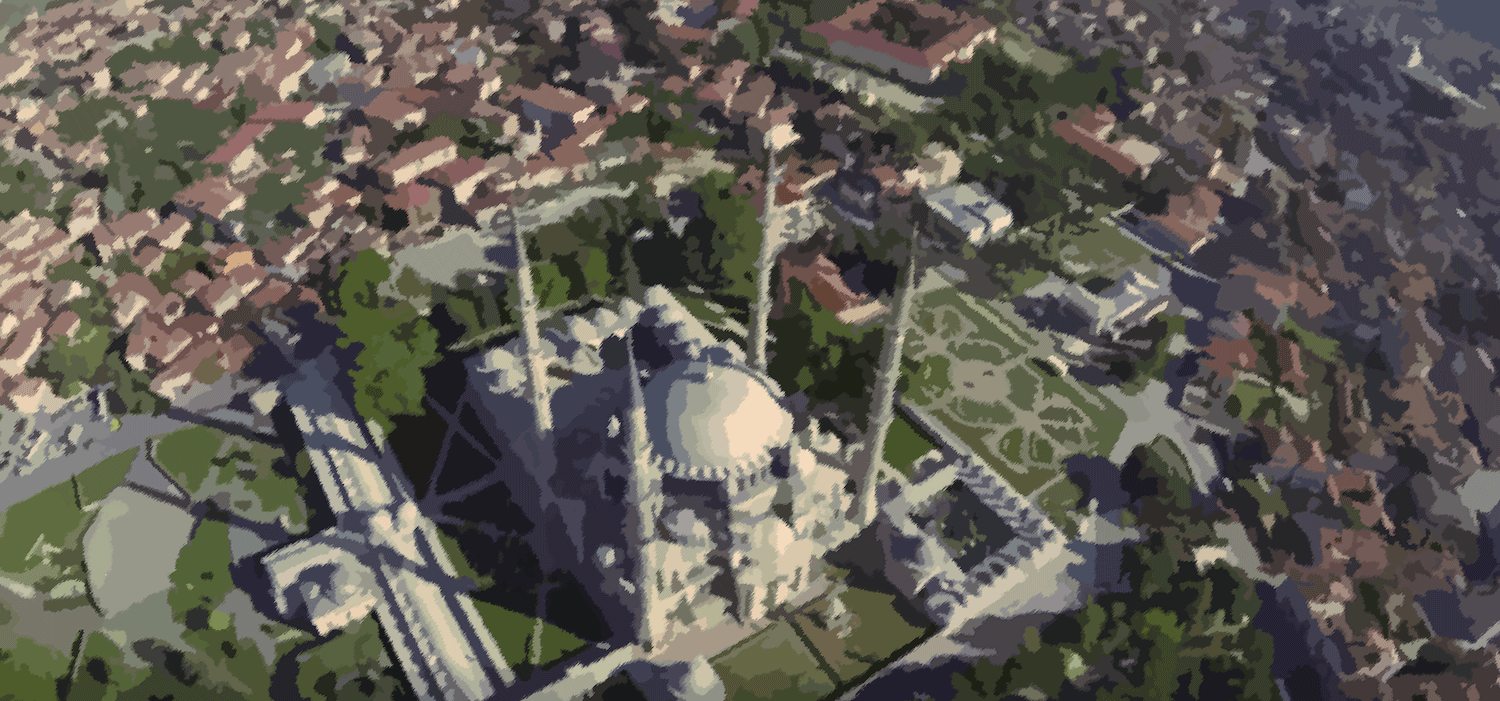

Digitally-transformed still of drone footage showing the neighborhood to the north-west of the mosque of Sulṭán Salím (in the top left-hand corner of the painting).

After six months in the Murádíyyih neighborhood, the Bahá'ís found the perfect house for Bahá'u'lláh and the Holy Family.

It was called—providentially—the house of ‘Amru’lláh (House of God's Command), and it was in a different neighborhood, in the heart of Edirne, located northwest of the 16th century Mosque of Sulṭán Salím, the glory of Edirne.

The house of ‘Amru’lláh was a spacious, magnificent mansion with its own Turkish bath and a kitchen with running water. Its private andarúní (the inner quarter, reserved for the women and the immediate family) was three stories high and had 30 rooms.

The bírúní (the men’s quarters and public-facing side of the house) had four or five beautiful rooms on the upper floor for reception or housing, and for preparing and serving the refreshments.

Mírzá Yaḥyá, Ṣubḥ-i-Azál (Morning of Eternity), in 1888, twenty-three years after the events depicted in this story. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

A darkness had been steadily growing in the heart of Mírzá Yaḥyá since the Declaration of Bahá'u'lláh in Baghdad.

Ever since Bahá'u'lláh’s return from Kurdistán, Mírzá Yaḥyá had lived in hiding, posing as a shoe merchant or barricaded in his own house, terrified of any danger to himself. His jealousy at the marks of high honor Bahá'u'lláh received and the utter devotion of His followers raged in his heart.

Mírzá Yaḥyá had been corrupted beyond salvation by his constant association with Siyyid Muḥammad-i-Iṣfahání, the Antichrist of the Bahá'í Revelation, who had promised him unchallenged leadership of the community. Siyyid Muḥammad was the very personification of evil, greed and deceit.

Mírzá Yaḥyá had committed unspeakable acts, corrupting the text of the Báb’s Holy Writings, modifying the obligatory prayer to include a reference to himself as the Godhead, falsely claiming himself and his children as descendants of the Báb.

Siyyid Muḥammad had played a hand in the murders of Dayyán, and the Báb’s cousin, and had married, shortly after Mírzá Yaḥyá, the second wife of the Báb, a desecration of the name and reputation of the Báb which broke Bahá'u'lláh’s heart.

There came a point in 1865 when Mírzá Yaḥyá could no longer be reasoned and he started down his evil path and His open rebellion began, he would go down in Bahá'í history as the and the Arch-breaker of the Covenant of the Báb.

Original photo by Meg Jerrard on Unsplash.

By December 1865, Mírzá Yaḥyá became obsessed with poisoning Bahá'u'lláh to gain control of the Bahá'í community.

He knew Bahá'u'lláh's faithful brother, Mírzá Músá, was very knowledgeable about medicine, and, under false pretenses, asked him about the effects of herbs and poisons.

Then, unusually for him, Mírzá Yaḥyá began to invite Bahá'u'lláh to his home, and on one of His visits, Mírzá Yaḥyá served Bahá'u'lláh tea in a cup he had smeared with a toxic substance he had concocted, and he poisoned Bahá'u'lláh.

Bahá'u'lláh was seriously ill for 21 days, with severe pains and high fever, and the aftermath of the poisoning would leave Him with a shaking hand until the end of His life.

His condition was so severe that the family called on a foreign Christian doctor named Shíshmán. The doctor was so shocked by Bahá'u'lláh’s livid skin tone that he fell to his feet, declared His case was hopeless, and left Bahá'u'lláh’s bedside without prescribing a remedy.

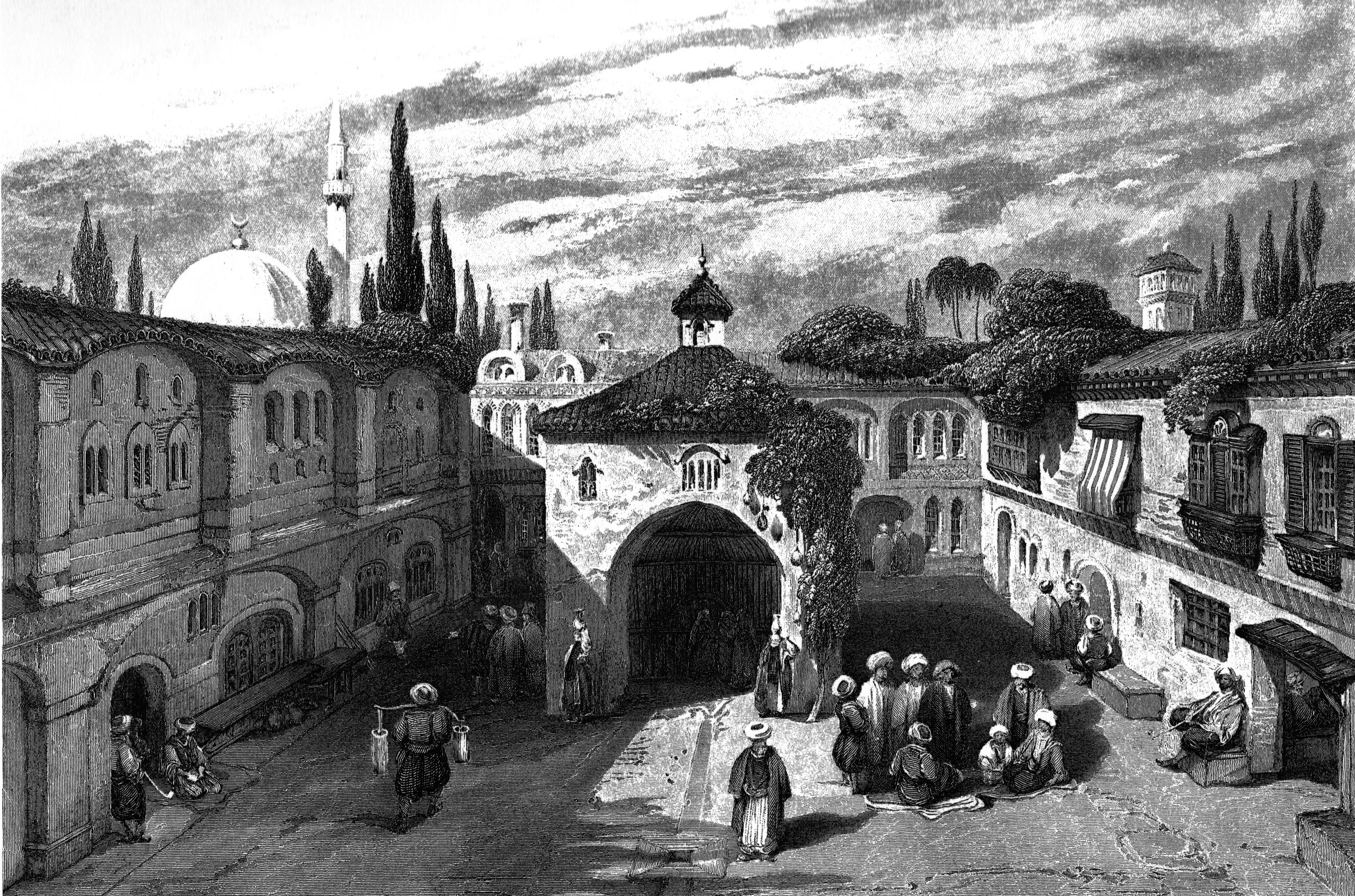

Edirne square with a well around 1835. After a painting by F. Hervé. Drawing by W.L. Leitch, engraving by J. Tingle. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Mírzá Yaḥyá continued his plotting to kill Bahá'u'lláh. He made two additional attempts that we know of.

First, he tried poisoning the well of the house of Amru'lláh the only source of drinkable for the Holy Family, including the Greatest Holy Leaf. This attempt failed, and only a few Bahá'ís came down with strange symptoms.

Second, Mírzá Yaḥyá tried to get someone else to kill Bahá'u'lláh for him, and he approached Bahá'u'lláh’s loyal barber, Ustád Muḥammad-‘Alí, and tried, through insinuation and manipulation, to get him to kill Bahá'u'lláh.

He could not have picked a worst person to ask.

When Ustád Muḥammad finally understood exactly what it was that Mírzá Yaḥyá was hinting at, he almost killed Mírzá Yaḥyá on the spot, then informed the community of Mírzá Yaḥyá’s despicable intentions.

The Bahá'í community was now officially divided into loyal Bahá'ís and the followers of Mírzá Yaḥyá who would later be known as Covenant-breakers.

The Most Great Separation was about to take place.

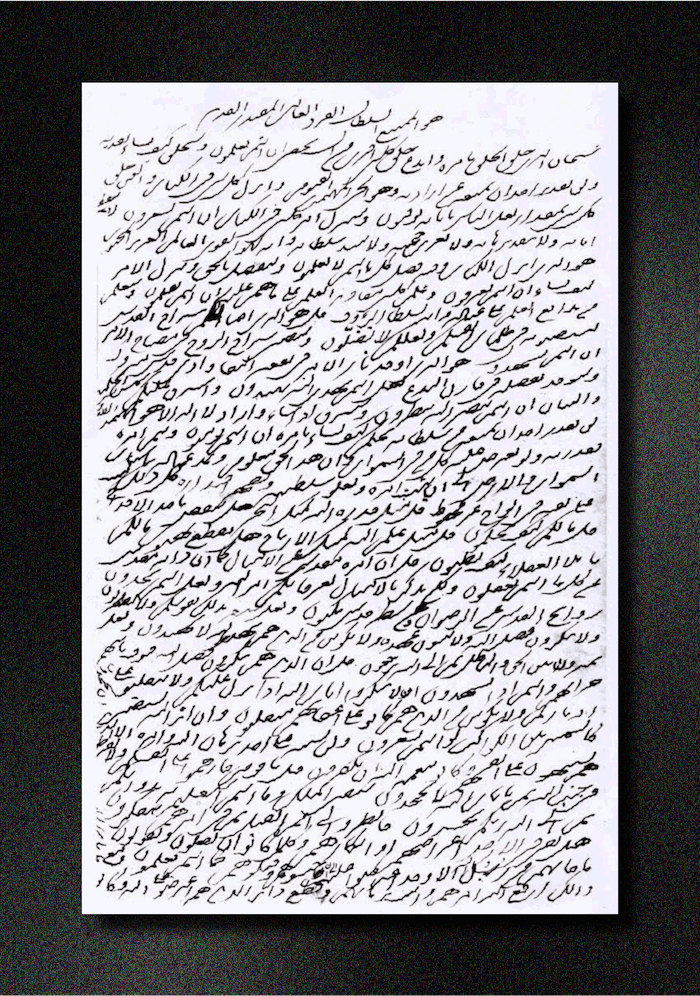

The first page of the Suri-i-Amr in Baha’u’llah’s handwriting which was affected by the poisoning that left his hand trembling, and which was revealed three months after the attempt on His life, around March 1866. Source: Bahá'í Sacred Relics: A Tablet in Baha'u'llah's own hand after He was poisoned by His half-brother

Three months after He survived the poisoning, Bahá'u'lláh decreed the time had finally come for Him to formally acquaint Mírzá Yaḥyá with His station as “Him Whom God shall make manifest.”

Bahá'u'lláh did this by revealing a major proclamatory Tablet in Arabic known as the Súriy-i-Amr (Surah of Command).

Mírzá Yaḥyá’s response was absolutely irrational.

He became angry, mocked Bahá'u'lláh’s use of Arabic instead of Persian, and, sealing his fate as the Arch-breaker of the Covenant of the Báb, Mírzá Yaḥyá made the absolutely outrageous and disgraceful claim that he, too, had received a Revelation from God.

This was the start of the Most Great Separation, one which not only marked a final irreconcilable break between Bahá'u'lláh and Mírzá Yaḥyá, but which Shoghi Effendi, Guardian of the Bahá'í Faith, called “one of the darkest dates in Bahá’í history.”

The house of Riḍá Big in the 1960s. Source: Bahá'í Media.

After the Most Great Separation, Bahá'u'lláh retired from the Bahá'í community, removing Himself from a situation of disunity and allowing believers the freedom in choosing to follow Him or Mírzá Yaḥyá.

Bahá'u'lláh left the house of ‘Amru’lláh on 10 March 1866, moving His immediate family, including the Greatest Holy Leaf, to the house of Riḍá Big, in another neighborhood of Edirne. He instructed His brother Mírzá Músá to divide all the furniture, bedding, clothing and utensils in the house of ‘Amru’lláh, giving half to Mírzá Yaḥyá’s household and dividing the rest among the believers.

Bahá'u'lláh’s seclusion was total.

For two months, He refused to associate with followers friend, stranger or foe, and He remained in the house of Riḍá Big for approximately one year, until Mírzá Yaḥyá and Siyyid Muḥammad’s abominable actions forced Him out of retirement.

Forbidden access to the house of Riḍá Big, Bahá'u'lláh’s companions were distressed and heartbroken, deprived of His company and guidance.

Inconsolable, they cut off all ties with the followers of Mírzá Yaḥyá and his evil influence.

Schemers. Digital art by Violetta Zein.

During Bahá'u'lláh’s two-month seclusion, Mírzá Yaḥyá and Siyyid Muḥammad embarked on such a ferociously ill-willed smear campaign that the Bahá'ís were stunned.

They wrote letters filed with vile slander, misrepresenting Bahá'u'lláh and accusing Him of everything Mírzá Yaḥyá had done, and distributed these poisonous letters widely among the believers in ‘Iráq and Persia.

Siyyid Muḥammad accused Bahá'u'lláh, who had ensured he and Mírzá Yaḥyá were receiving their monthly government allowance, of withholding it and of hiring an assassin to kill Náṣiri’d-Dín Sháh. Around May 1866, Mírzá Yaḥyá sent one of his wives to the government house lying that Bahá'u'lláh had cut off her husband’s allowance.

Their letters caused so much confusion and division in the Bahá'í community that some lost their faith, others wrote to Bahá'u'lláh for guidance to which He responded, and still others, like Nabíl, rose up to defend the Bahá'í Faith.

When Bahá'u'lláh returned to the community, one of the first things He did was to expel Siyyid Muḥammad-i-Iṣfahání from Faith.

The Most Great Separation between Bahá'u'lláh and Mírzá Yaḥyá which had taken place in March 1866 was now an official division between the Bahá'ís, the followers of Bahá'u'lláh, and the Azalís, the Covenant-breaking followers of Mírzá Yaḥyá.

The rift between the two communities became public knowledge.

Siyyid Muḥammad and Mírzá Yaḥyá’s letters and slander had caused irreparable damage in Ottoman government circles and they had already laid the groundwork for Bahá'u'lláh’s fourth and final exile to the prison-city of 'Akká.

Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash.

Bahíyyih Khánum was an unfailing spring of grace and loving-kindness to her family and the Bahá'í community, but throughout the trying years between Bahá'u'lláh’s poisoning and the Most Great Separation, Bahíyyih Khánum endured intense stress and deep-seated sorrows.

She was constantly assailed with countless oppressive trials and her lovely form was worn away to a shadow.

As the Bahá'í community was splitting into faithful believers and Covenant-breakers, Bahíyyih Khánum stood as an immovable and soaring pillar of strength. She did not wither and she did not hesitate.

She redoubled her efforts in servitude and sacrifice, she captivated hearts and won over hesitating souls, she destroyed doubts and misgivings, she led the community, she was filled to overflowing with the mercy of Bahá'u'lláh.

The influence of Bahíyyih Khánum’s pure loving-kindness transformed unmoving and unyielding believers into passionate lovers of Bahá'u'lláh.

The Greatest Holy Leaf’s faith was staunch, she had a calming presence and a forgiving attitude, but the rigors of the winter journey to Edirne and its extremely severe cold, combined with the privations of the early unhealthy accommodations in the city, which, when added to the extreme financial distress, and the division within the Bahá'í community, had permanently undermined her former health and vitality.

The storms of her years in Edirne imprinted themselves deeply in Bahíyyih Khánum’s consciousness, and to the end of her life, she would carry on her beautiful and angelic faces, the marks of intense spiritual and physical hardships she endured in that remote city on the European continent.

Ásíyih Khánum had been so deeply concerned about Bahá'u'lláh’s safety since Mírzá Yaḥyá’s poisoning attempt, that the Most Great Separation was almost a relief.

Mírzá Yaḥyá’s evil presence would hopefully be kept at bay now that he had his own community,

1933 photograph showing the ruins of the Turkish bath belonging to the house of 'Izzat 'Áqá. The house itself is on the right side of the picture. The long building to the left, extending towards the background is a school building and not part of the House of 'Izzat 'Áqá. Caption details provided by Mr. Mohssen Madjidi.Source: The Bahá'í World Volume V (1932-1934), Martha Root: A visit to Adrianople, page 587.

In June 1867, Bahá'u'lláh, Ásíyih Khánum, 'Abdu'l-Bahá, Bahíyyih Khánum, and Mírzá Mihdí moved into their last house in Edirne, the house of 'Izzat Áqá.

The house of 'Izzat Áqá was newly-built and boasted a beautiful view of the river and the southern orchards of Edirne.

The rooms in the house were vast, the bírúní was smaller than the andáruní, but they were both large enough and each had a large tree-filled courtyard with flower beds.

Aerial view of the mosque of Sulṭán Salim (Selimiye mosque) showing the general area that Bahá'u'lláh walked through like a king on his way to publicly confront Mírzá Yaḥyá. Source: Research Gate.

In September 1867, when Bahá'u'lláh was living in the house of Izzat Áqá, a public confrontation was organized between Bahá'u'lláh and Mírzá Yaḥyá, to settle whose claim was the truth. This was a tradition in Islám, called mubáhilih, and was considered an effective and fair means of resolving theological disputes.

The mistake Mírzá Yaḥyá made was thinking that Bahá'u'lláh would never come to a public confrontation. So he set the most unlikely and most public time and place he could think of: high noon at the mosque of Sulṭán Salím for Friday, at the time of the congregational prayer, the busiest time of the week when the mosque would be filled with a large crowd of people.

On Friday, the crowd’s impatience was palpable. The whole of Edirne was astir. From morning until noon, a huge crowd of Muslims, Christians, and Jews lined the streets from the house of Amru’lláh to the mosque of Sulṭán Salím. The crowd was so large, it was difficult to move about.

Bahá'u'lláh emerged from the house of 'Izzát Áqá around noon, and as He passed under the mid-day sun, accompanied by Mír Muḥammad, people showed Him reverence fit for a King. They greeted Him with salutations and bowed, opening the way for Him to advance through the crowd. Many kneeled to kiss His feet, and Bahá'u'lláh, radiating divine majesty and power, greeted the people by raising His hands and offering His good wishes, as He made His way to the Mosque of Sulṭán Salim.

At last, Bahá'u'lláh and Mír Muḥammad reached the mosque of Sulṭán Salím.

As soon as Bahá'u'lláh entered the mosque, the Imám who was delivering his discourse became speechless. Bahá'u'lláh came forward, sat down, and asked the Imám to continue.

The afternoon prayer ended.

Mírzá Yaḥyá never showed.

Mírzá Yaḥyá would later claim that Bahá'u'lláh had never shown up to the first meeting, but he had lost face in front of the crowd of witnesses that saw Bahá'u'lláh at the mosque.

The public confrontation had proved Bahá'u'lláh's supremacy and utterly and publicly humiliated Mírzá Yaḥyá.

Original photo by Richard Ciraulo on Unsplash.

After Mírzá Yaḥyá’s cowardice and refusal to communicate with Bahá'u'lláh after the debacle of the public confrontation, Bahá'u'lláh publicly and officially branded Mírzá Yaḥyá as a Covenant-breaker and expelled him from the Bahá'í community forever.

Mírzá Yaḥyá had been the master of his own spiritual downfall.

It was a dramatic conclusion to the year-long episode of the Most Great Separation.

In the life of Bahá'u'lláh, victory follows crisis, and after the fire of tests, the floodgates of Revelation were flung wide open.

After the events of the last months, including His majestic bearing during the public confrontation, Bahá'u'lláh had earned the unanimous admiration and respect of the population of Edirne and the unquestioned allegiance of the Bahá'ís.

The crisis of the Most Great Separation was so severe that it brought untold sorrows to Bahá'u'lláh and visibly aged Him.

In its weighty repercussions, the Most Great Separation would be the heaviest blow ever sustained by Bahá'u'lláh during His 40-year ministry.

Bahá'u'lláh was bent with sorrow and still suffering from the aftermath of His attempted assassination, but He was undaunted.

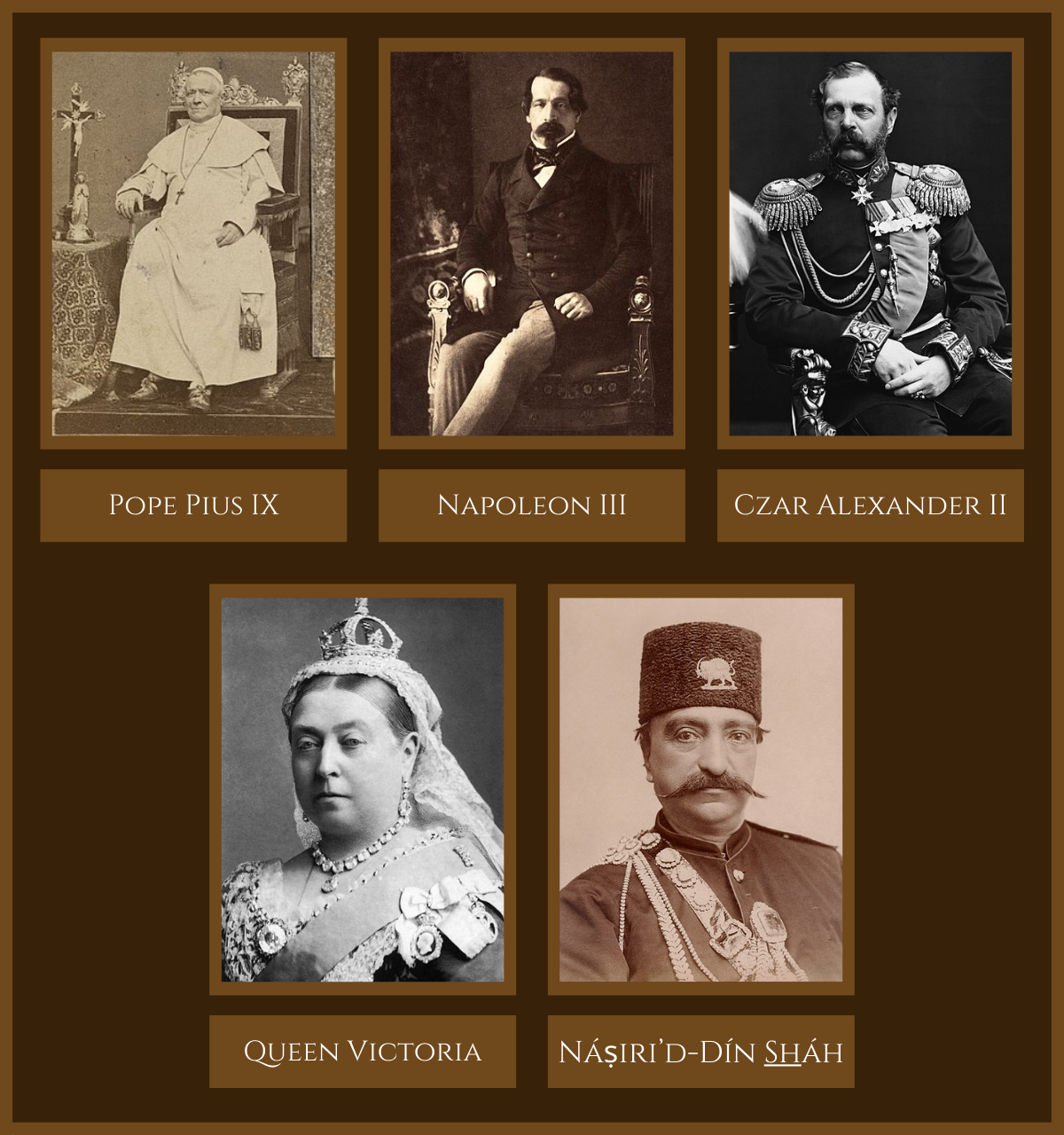

Five of the sovereigns addressed by Bahá'u'lláh in His Summons to the Lord of Hosts.

Top left: Pope Pius IX. Fratelli d’Alessandri Studio. Wikimedia Commons.

Top center: Napoleon III. Gustave Le Gray. Wikimedia Commons

Top right: Czar Alexander II. Unknown author. Wikimedia Commons.

Bottom left: Queen Victoria. Alexander Bassano. Wikimedia Commons.

Bottom right: Náṣiri’d-Dín Sháh. Nadar. Wikimedia Commons.

Bahá'u'lláh’s eleven remaining months in Edirne, in the house of ‘Izzat Áqá, from September 1867 to August 1868, constitute the most prodigiously prolific period in the entirety of His forty-year ministry. Tablets, epistles, and verses flowed continuously from His pen and His tongue, at times at such a rapid pace that no one, not even His own secretary, could copy them down.

Bahá'u'lláh revealed the Súriy-i-Mulúk (Surah of Kings), His most momentous proclamatory work addressed to the Kings of the earth, immediately after the darkest and most tumultuous period of His life, the Most Great Separation and the casting out of Mírzá Yaḥyá in September 1867.

Around May 1868, Bahá'u'lláh revealed His First Tablet to Napoleon III and sent it to the French Emperor through one of his ministers.

A few weeks before 12 August 1868: Bahá'u'lláh revealed the Lawḥ-i-Sulṭán (Tablet to Naṣiri'd-Dín Sháh.

The Lawḥ-i-Sulṭán is Bahá'u'lláh’s lengthiest Tablet to any monarch and deeply significant for two main reasons: first, it is addressed to the ruler of Bahá'u'lláh’s native land, and second, it is addressed to the only ruler to have savagely persecuted both the Bábí and Bahá'í Faiths—and by extension the Báb and Bahá'u'lláh—from their inception.

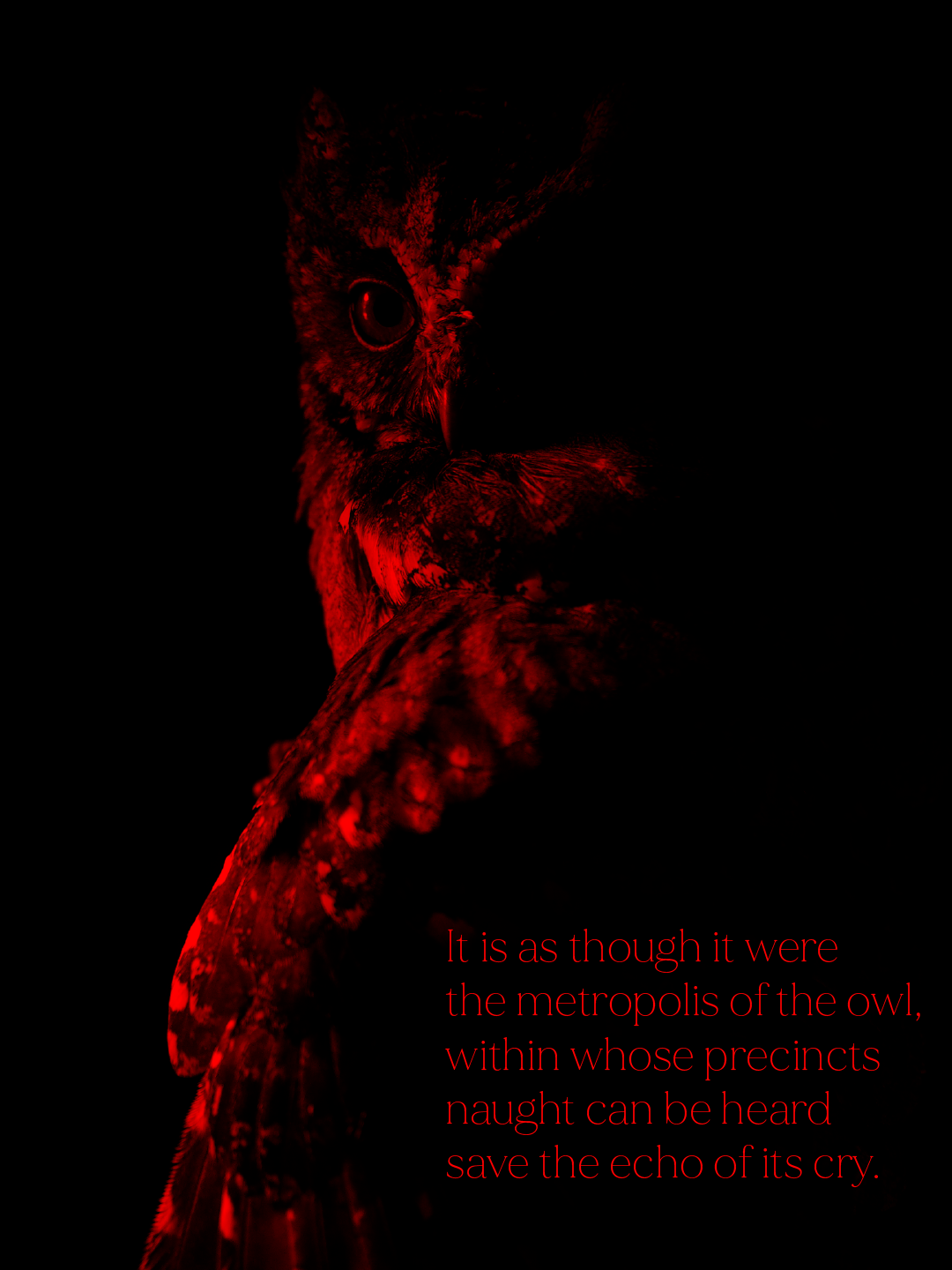

The metropolis of the owl. Photo by Agto Nugroho on Unsplash.

Bahá'u'lláh began revealing the Lawḥ-i-Sulṭán a few weeks before 12 August 1868.

The Lawḥ-i-Sulṭán is Bahá'u'lláh’s single longest Tablet to any monarch.

It is 11,133 words long and in the English version, counts 86 paragraphs.

Nine paragraphs from the very end of the Lawḥ-i-Sulṭán, Bahá'u'lláh predicts His exile to 'Akká, weeks before the Bahá'ís would even find out what their final destination was.

Erelong shall the exponents of wealth and power banish Us from the land of Adrianople to the city of ‘Akká. According to what they say, it is the most desolate of the cities of the world, the most unsightly of them in appearance, the most detestable in climate, and the foulest in water. It is as though it were the metropolis of the owl, within whose precincts naught can be heard save the echo of its cry. Therein have they resolved to imprison this Youth, to shut against our faces the doors of ease and comfort, and to deprive us of every worldly benefit throughout the remainder of our days.

SOURCES FOR PART III

3 May – August 1863: Bahíyyih Khánum leaves her home

Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees, Baharieh Rouhani Ma’ani, George Ronald, Oxford, 2013, page 139.

Violetta Zein, The Blessed Beauty Chronology Part 5: In Constantinople.

The Caravan and the scale of the journey

The caravan and the scale of the journey:

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá’u’lláh: The King of Glory, page 176.

The companions of Bahá’u’lláh:

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868, pages 5-6.

The March of the King of Glory

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá’u’lláh: The King of Glory, page 176.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868, page 6.

Star of the West, Volume XIII, No. 10, pp. 277–278. “Exiled From Bagdad: A story from the words of Abdul Baha” by Mirza Ahmad Sohrab.

Myron H. Phelps, The Master in ‘Akká, page 41.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá’u’lláh: The King of Glory, page 179.

Balyuzi, H.M. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá: The Centre of the Covenant of Bahá’u’lláh, page 17.

The Diary of Ahmad Sohrab, 26 April 1913, pages 19-22.

3 May – June 1863: The journey through Iraq

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá’u’lláh: The King of Glory, pages 176-178, 181-184.

Myron Phelps, The Master in ‘Akká, page 41.

Ustád Muḥammad-‘Alíy-i-Salmání, the Barber, My Memories of Bahá’u’lláh, page 28.

Wikipedia: Eid al-Adha.

HOW THE DATE FOR IRBIL WAS OBTAINED

The Islamic Holy Day of ‘Íd al-Aḍhá always falls on the 10th day of the last month of the Muslim calendar, Dhu-al-Hijjah. That day, in 1862-1863 (1279 A.H.) fell on 28 May 1863.

Habibur: Islamic Hijri Calendar For Dhu al-Hijjah – 1279 Hijri

The Life and Teachings of ‘Abbás Effendi, Myron Phelps, GP Putnams Sons, New York and London, 1904, PDF Edition from Bahá’í Library Online, page 32.

June – 13 August 1863: The overland journey through Anatolia

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá’u’lláh: The King of Glory, page 185, 186, 188, and 190-195.

Wikipedia: Jaghjagh River.Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Star of the West, Volume XIII, No. 10, pp. 277–278. “Exiled From Bagdad: A story from the words of Abdul Baha” by Mirza Ahmad Sohrab.

Ustád Muḥammad-‘Alíy-i-Salmání, the Barber, My Memories of Bahá’u’lláh, pages 31-35.

Facebook: Tokatadair: Underground houses in Boyunpınar.

7 – 13 August 1863: Sámsún, the last leg of the journey

Bahá’u’lláh, Tablet of the Holy Mariner.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá’u’lláh: The King of Glory, pages 195-196.Baha’i Tablets: Provisional translations: Tablet of the Howdah, a provisional translation by Stephen N. Lambden.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Steven Phelps’ Chapter 5: The Writings of Bahá’u’lláh in Routledge World: The World of the Bahá’í Faith, First Edition, Edited By Robert H. Stockman.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá’u’lláh: The King of Glory, page 195.

13 – 16 August 1863: The sea journey to Istanbul

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá’u’lláh: The King of Glory, page 196.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Wikipedia: Round City of Baghdad.

Wikipedia: Constantinople.

16 August – September 1863: The house of Shamsí Big

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá’u’lláh: The King of Glory, page 197.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh Volume 2: Edirne 1863-1868, page 2.

Sometime in September 1863: The house of Vísí Páshá

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá’u’lláh: The King of Glory, page 199.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh Volume 2: Edirne 1863-1868, page 3.

Shortly before 1 December 1863: The third exile

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá’u’lláh: The King of Glory, pages 198-203.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá, A Travelers’ Narrative.

1 December 1863: Leaving Istanbul

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá’u’lláh: The King of Glory, page 204.

1 – 12 December 1863: From Istanbul to Edirne

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá’u’lláh: The King of Glory, page 205.

The Greatest Holy Leaf’s testimony about the harshness of the journey

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá’u’lláh: The King of Glory, page 204.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868, page 61-62.

Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees, Baharieh Rouhani Ma’ani, George Ronald, Oxford, 2013, page 141.

Wikipedia: Frostbite.

12 – 21 December 1863: The first house in Edirne

Violetta Zein, The Blessed Beauty chronology Part 6: Adrianople.

The Life and Teachings of ‘Abbás Effendi, Myron Phelps, GP Putnams Sons, New York and London, 1904, PDF Edition from Bahá’í Library Online, page 35.

June 1864: The house of Amru’lláh

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá’u’lláh: The King of Glory, pages 217 and 221.

Bahá’u’lláh, The Tablet of Aḥmad.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868, pages 169-170.

Mírzá Yaḥyá and Siyyid Muḥammad-i-Iṣfahání

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

“Nor can this subject be dismissed without special reference being made to the Arch-Breaker of the Covenant of the Báb, Mírzá Yaḥyá…” quoted from Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Ustád Muḥammad-‘Alíy-i-Salmání, the Barber, My Memories of Bahá’u’lláh, pages 46-48.

“…allowing himself [Mírzá Yaḥyá] to be duped by the enticing prospects of unfettered leadership held out to him by Siyyid Muḥammad, the Antichrist of the Bahá’í Revelation, even as Muḥammad Sháh had been misled by the Antichrist of the Bábí Revelation…” quoted from Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

December 1865: Mírzá Yaḥyá tries to assassinate Bahá’u’lláh

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá’u’lláh: The King of Glory, page 225.

Mírzá Yaḥyá’s two additional assassination attempts

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868, page 159-161.

Ustád Muḥammad-‘Alíy-i-Salmání, the Barber, My Memories of Bahá’u’lláh, pages 49-53.

10 March 1866: The Most Great Separation

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Steven Phelps “The Writings of Bahá’u’lláh” in Routledge World: The World of the Bahá’í Faith, First Edition, Edited By Robert H. Stockman, page 59.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868, pages 161-162.

Lady Blomfield, The Chosen Highway, page 60.

Ustád Muḥammad-‘Alíy-i-Salmání, the Barber, My Memories of Bahá’u’lláh, page 45.

10 March – May 1866: Bahá’u’lláh’s seclusion in the house of Riḍá Big

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá’u’lláh: The King of Glory, page 232.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868, pages 162 and 164-165.

March– May 1866: Mírzá Yaḥyá and Siyyid Muḥammad’s two-month smear campaign

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá’u’lláh: The King of Glory, pages 232-124.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868, pages 165-167, 170 and 325-328.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Covenant of Bahá’u’lláh, Chapter 4, paragraph [4-25].

The effect of the Most Great Separation on Bahíyyih Khánum

Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees, Baharieh Rouhani Ma’ani, George Ronald, Oxford, 2013, pages 106-107 and 143.

June 1867 – August 1868: The house of ‘Izzat Áqá

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá’u’lláh: The King of Glory, pages 241 and 249.

Anthony A Reitmayer, Adrianople: Land of Mystery, page 42.

September 1867: The public confrontation between Bahá’u’lláh and Mírzá Yaḥyá

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Wikipedia: Event of Mubahala.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868, pages 295-296.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Covenant of Bahá’u’lláh, Chapter 5.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá’u’lláh: The King of Glory, pages 239-242.

September 1867: Bahá’u’lláh casts Mírzá Yaḥyá out of the community

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Juan Cole, The Azálí-Bahá’í Crisis of September 1867.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868, pages 301-303.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá’u’lláh: The King of Glory, pages 243-244.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868, page 397.

SÚRIY-I-MULÚK

Steven Phelps “The Writings of Bahá’u’lláh” in Routledge World: The World of the Bahá’í Faith, First Edition, Edited By Robert H. Stockman, page 59.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Wikipedia: Summons of the Lord of Hosts: Súriy-i Mulúk “Tablet of Kings”

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868, pages 301-336.

TABLET TO NAPOLEON III

Steven Phelps “The Writings of Bahá’u’lláh” in Routledge World: The World of the Bahá’í Faith, First Edition, Edited By Robert H. Stockman, pages 63-64.

For the date of the Tablet: Ismael Velasco, Baha’u’llah’s First Tablet to Napoleon III: A Research Note, published in Lights of Irfan, 4, pages 143-164.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868, pages 368-369.

LAWH-I-SULTAN

Steven Phelps “The Writings of Bahá’u’lláh” in Routledge World: The World of the Bahá’í Faith, First Edition, Edited By Robert H. Stockman, page 64.

Bahá’u’lláh, Lawḥ-i-Sulṭán (Tablet to Naṣiri’d-Dín Sháh)

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868, pages 337-357.

DATE OF THE LAWH-i-SULTAN

In its Introduction to the Summons of the Lord of Hosts, the Universal House of Justice states:

“Of the various writings that make up the Súriy-i-Haykal, one requires particular mention. The Lawḥ-i-Sulṭán, the Tablet to Náṣiri’d-Dín Sháh, Bahá’u’lláh’s lengthiest epistle to any single sovereign, was revealed in the weeks immediately preceding His final banishment to ‘Akká.”

With many thanks to Mohssen Madjidi for providing the source of this date.

A few weeks before 12 August 1868: Bahá’u’lláh predicts His last exile

Bahá’u’lláh, Lawḥ-i-Sulṭán.

![]()

3 May – August 1863: Bahíyyih Khánum leaves her home

3 May – August 1863: Bahíyyih Khánum leaves her home