Written and illustrated by Violetta Zein

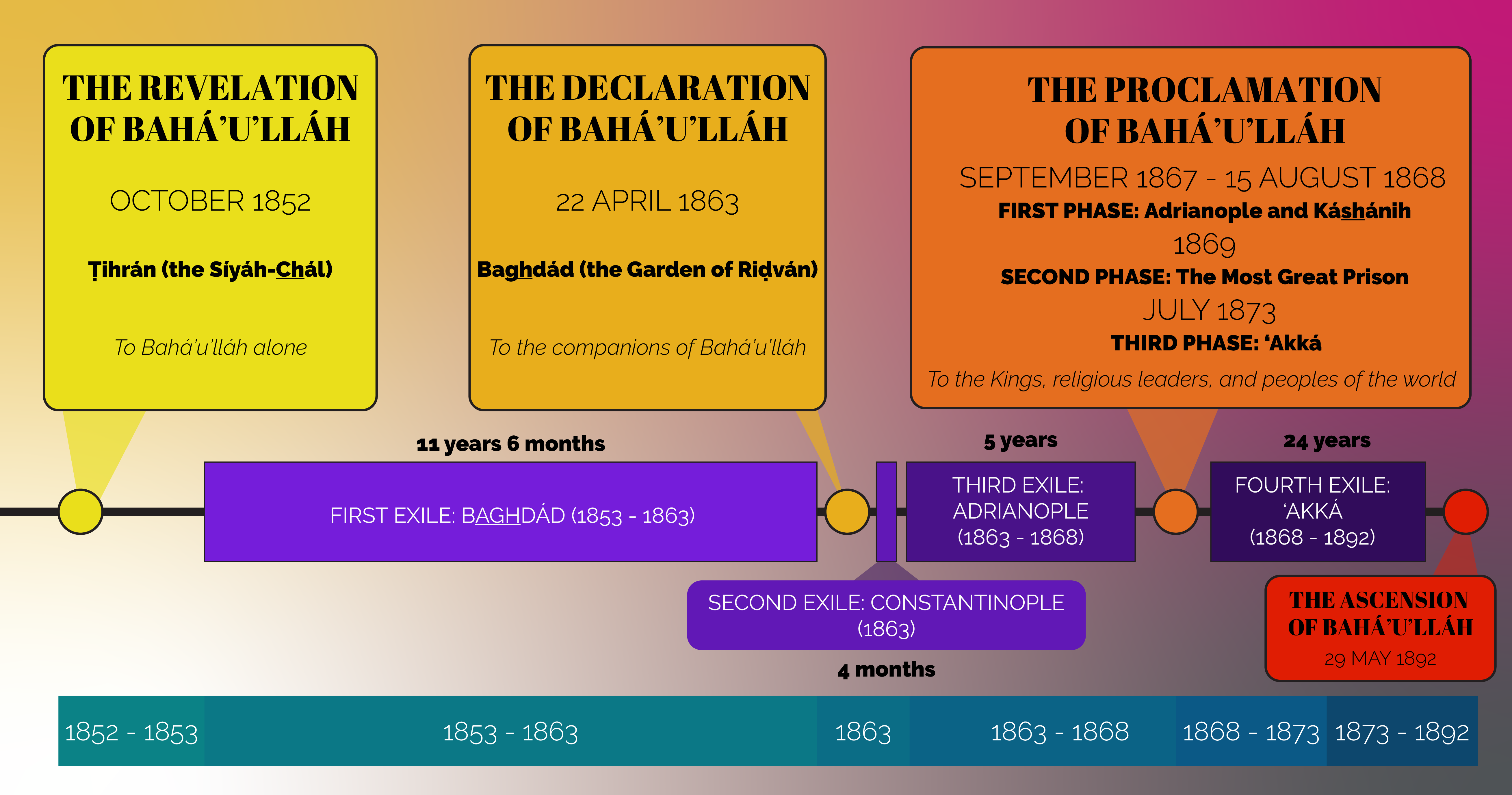

This part covers the life of Bahá’u’lláh from the age of 39 in 1856, to the age of 46 in 1863.

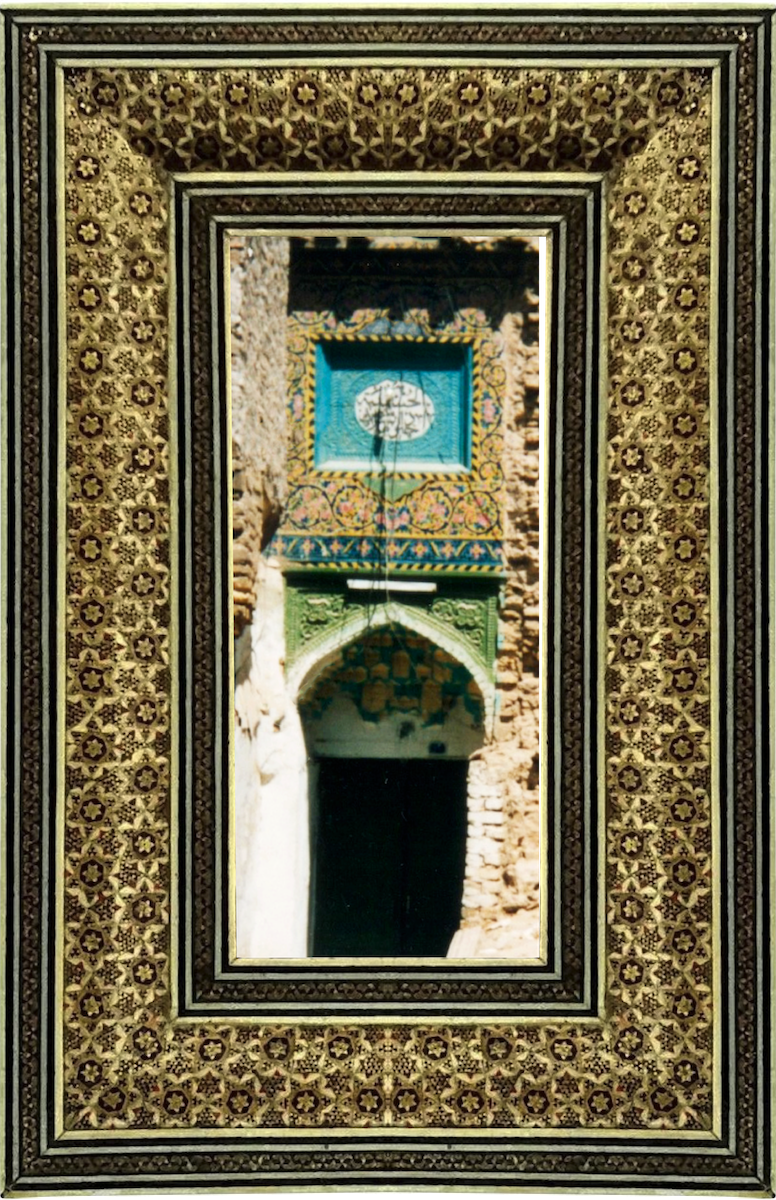

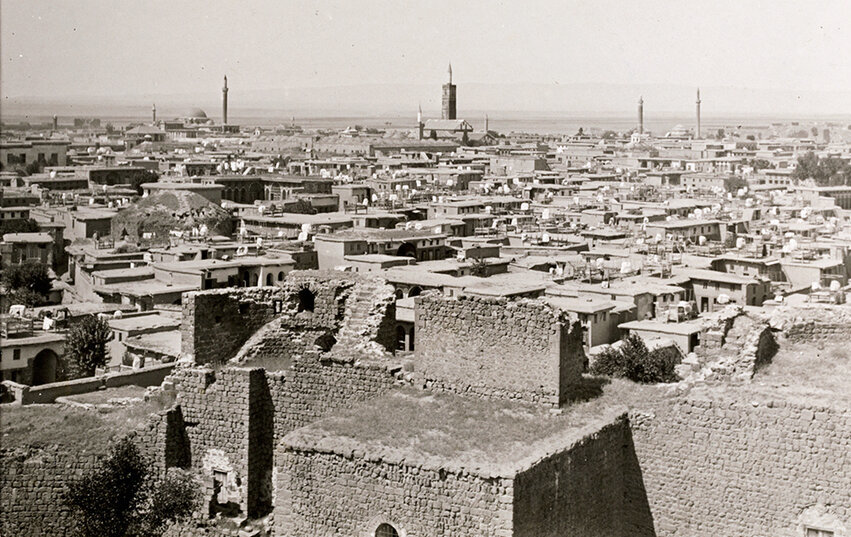

The entrance to the Most Great House. Digitally-framed color photograph obtained from Sa'ad Salim, used with permission.

From the moment Shaykh Sulṭán had left on his mission to find Bahá'u'lláh in Kurdistán, the Holy Family had begun to regain hope of seeing Bahá'u'lláh again. Ásíyih Khánum made a coat for her beloved Husband out of a precious red cloth, tirmíh, which she had especially set aside from her marriage treasures for this purpose.

On 19 March 1856, Ásíyih Khánum, 'Abdu'l-Bahá, and Bahíyyih Khánum sat breathlessly, as they heard a step. Although, outwardly, He looked like a dervish, they instantly recognized Bahá'u'lláh! The moment they had all impatiently awaited for two long years was finally here! The entire family was submerged in an ocean of joy. The children clung to their Father, 'Abdu'l-Bahá holding Bahá'u'lláh’s hand tightly, as if he never intended to let Him out of His sight again.

It was a deeply happy and touching scene: Ásíyih Khánum, kind and gentle, ecstatic, 'Abdu'l-Bahá, ecstatic, and enveloped in Darvísh Muḥammad’s coarse clothes. Bahá'u'lláh’s wife and children never tired of His stories from Sar-Galú and Sulaymáníyyih. He described for them the simple foods He ate, coarse bread a little cheese, and a rare treat when He could have it, a type of rice pudding He would make with rice and a tiny bit of sugar, cooked in milk.

Bahá'u'lláh recounted the story of the young boy, weeping bitterly over his calligraphy exercise, how His penmanship had caught the attention of the Kurds, and how He retreated further into caves, moving from place to place when people tried to pry Him out of His solitude, and He told them that He had left Mírzá Músá’s name with His Kurdish friends in Sulaymáníyyih, telling them they would always be able to find Him in Baghdád if they spoke His brother’s name.

After Bahá'u'lláh’s return, joy followed joy: first, Mírzá Músá married the daughter of the loyal ‘Iráqí Bábí who had brought Bahá'u'lláh back, Shaykh Sulṭán, and then, in 1858, after a five-year absence, the family was reunited at last with Mírzá Mihdí, now almost ten years old! But while the family of Bahá'u'lláh experienced great happiness during this time, Bahá'u'lláh returned to find a Bábí community in shambles. His work of spiritual regeneration awaited.

Lady Blomfield, The Chosen Highway, pp. 53-54.

FAINT DISPIRITED LOST DEAD © Violetta Zein.

After His two-year absence, Bahá'u'lláh found the Baghdád Bábí community in shambles, destroyed by Mírzá Yaḥyá and Siyyid Muḥammad’s two years of ravages, and irrelevant in the larger community. No one spoke of the Bábís. Bahá'u'lláh stated that “We found no more than a handful of souls, faint and dispirited, nay utterly lost and dead. The Cause of God had ceased to be on any one’s lips, nor was any heart receptive to its message.” The situation broke Bahá'u'lláh’s heart, and at first, He refused to leave the Most Great House, except occasionally to meet His friends in Baghdád and in Káẓimayn.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 123.

CRUEL MARTYRDOM © Violetta Zein.

Dayyán (One Who Rewards) was a peerless Bábí, praised by both the Báb and Bahá'u'lláh as the “Point of the Bayán,” the “repository of the knowledge of God,” the “Third Letter to believe in Him Whom God shall make manifest,” “the repository of the trust of the one true God…and the treasury of the pearls of His knowledge,” and the one whom the Báb “had taught the hidden and preserved knowledge”

In a moment of confusion, Dayyán was among those who put forth a short-lived claim to be "Him Whom God shall make manifest,” but immediately renounced all His claims after meeting Bahá'u'lláh in Baghdád, following His return from Kurdistán. Mírzá Yaḥyá felt immensely threatened by Dayyán and ordered his assassination. After meeting with Bahá'u'lláh in Baghdád, he was murdered by a man named Mírzá Muḥammad in Káẓimayn. Dayyán’s martyrdom filled Bahá'u'lláh with an immeasurable sadness.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 123-124.

Bahá'u'lláh, Epistle to the Son of the Wolf.

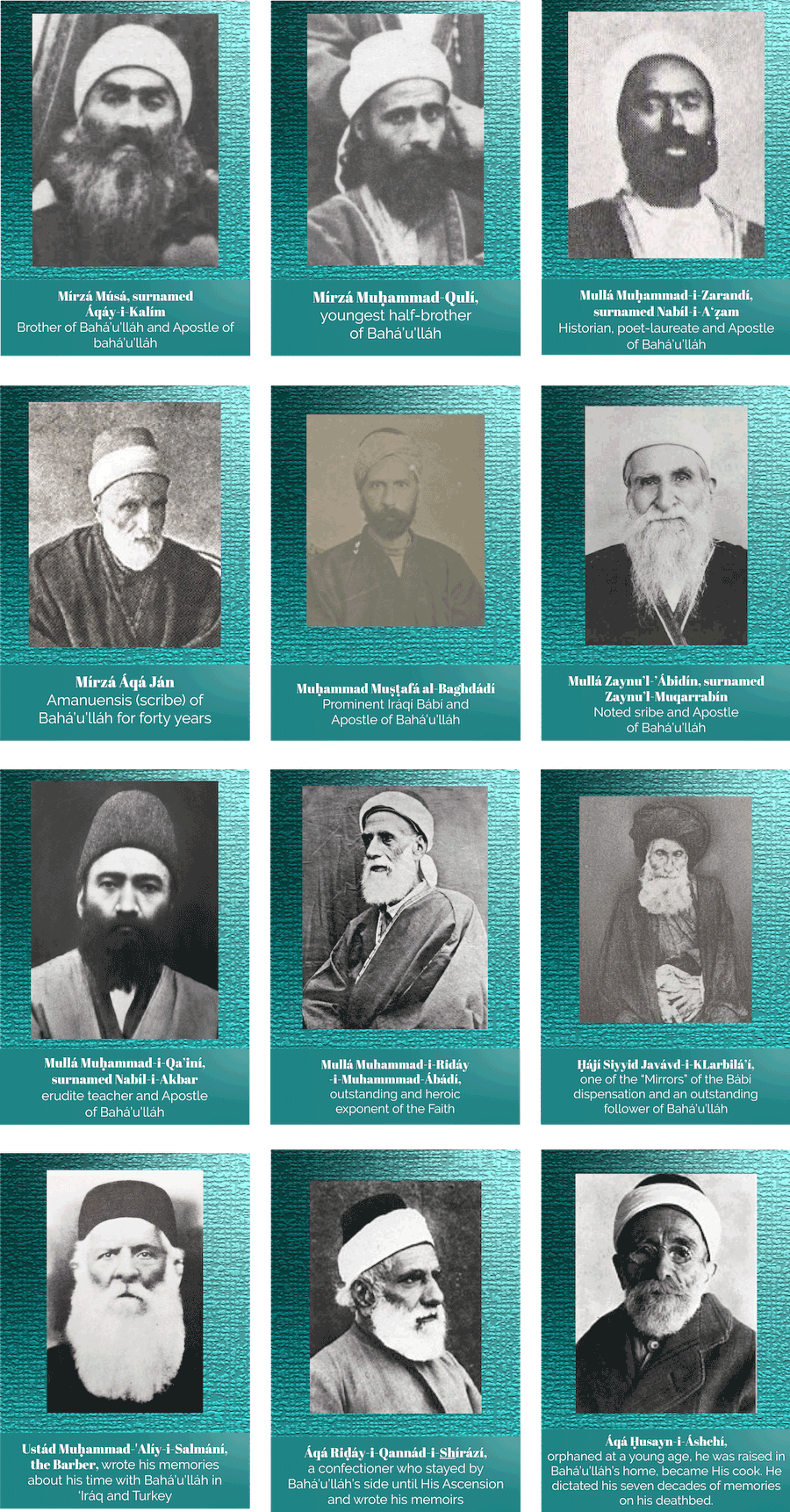

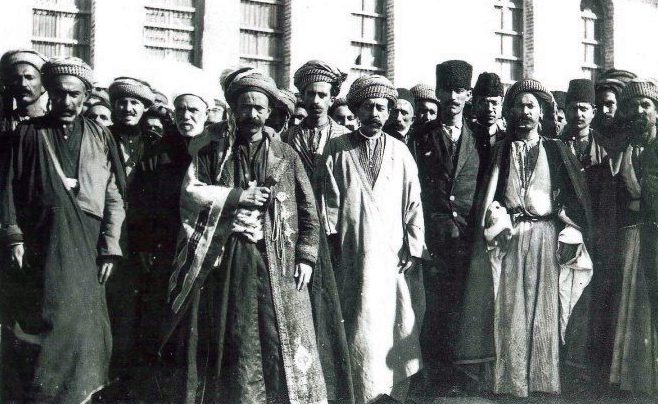

An imperfect attempt at showing the variety of the Bábí community in Baghdád, with devoted and loyal family members of Bahá'u'lláh, Persians, an eminent Iráqí believer, theologians, learned believers, historians, calligraphers, but also loyal and steadfast believers, a barber, a confectioner, and a cook who was orphaned at a young age and raised by Bahá'u'lláh.

The return of Bahá’u’lláh from Sulaymáníyyih was a significant turning point for the Bábí community of Baghdád. For the first time in its short history, apart from the first three years of the Báb’s ministry, the Bábí Faith now had a firm and immovable anchor point in the towering figure of Bahá'u'lláh. Bábís could come to Bahá'u'lláh and receive continuous, open and uninterrupted guidance, encouragement, and inspiration. Whatever their views or understanding of Bahá'u'lláh’s true station, the Bábís of Baghdád could finally center their hopes and their lives around One who could ensure the stability and integrity of their Cause and rebuild the prestige of their Faith.

For the moment, Bahá'u'lláh's enemies were silenced. Mírzá Yaḥyá, Siyyid Muḥammad, and their followers quieted down, some claiming to follow Bahá'u'lláh, others feigning respect, while some rejoined the ranks of the Bábí community.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Sunset on the banks of the River Tigris in Baghdád, Iráq, 1932, the banks of the Tigris is, in part, where Bahá'u'lláh revealed the Hidden Words. Source: Library of Congress.

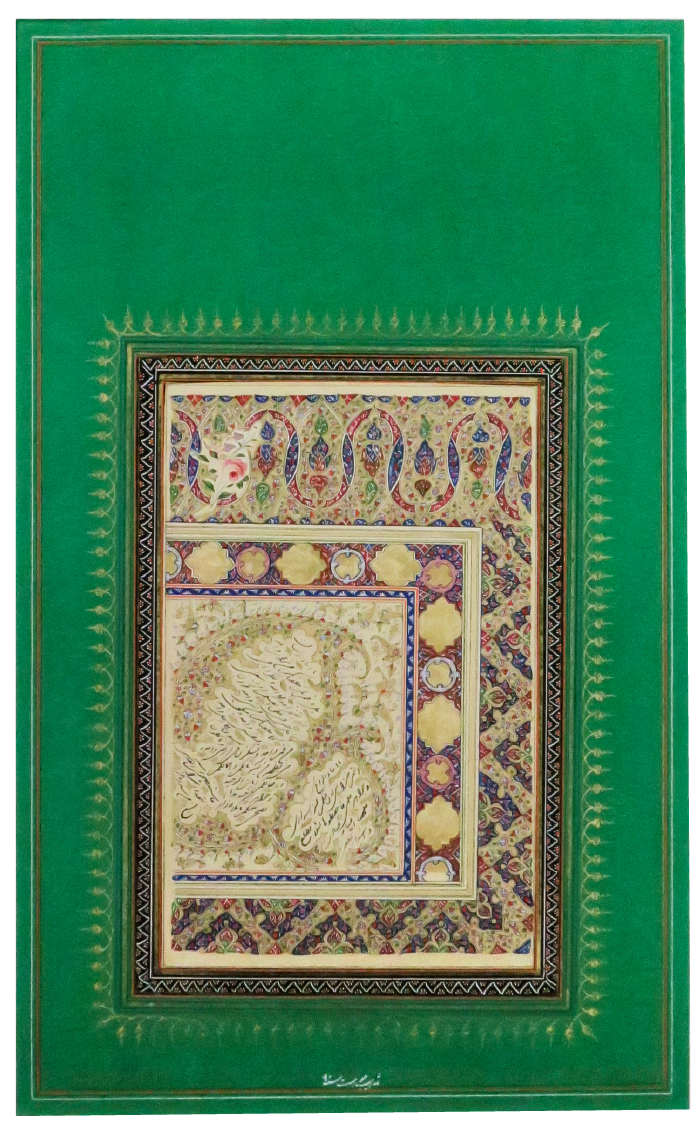

Verses from The Hidden Words by Bahá’u’lláh, in His own handwriting. © Baha’i International Community. Source: The British Museum blog: Displaying the Baha’i Faith: the pen is mightier than the sword.

About a year or two after His return to Baghdád, Bahá'u'lláh revealed His first major work, while pacing along the banks of the River Tigris. The Hidden Words is a masterpiece of spiritual gems “clothed in the garment of brevity,” and revealed partly in Arabic, and partly in Persian. Certain passages of the Hidden Words were revealed in one time and recorded in a single Tablet, and the rest, revealed at different times, were added to the first Revelation.

The Book of Fáṭimih, according to Shí’ah prophecy, contained the words of consolation the Angel Gabriel addressed, at God’s command, to a grieving Fáṭimih, mourning the death of her Father, the Prophet Muḥammad. In the early days of the Faith, the Hidden words were known as The Hidden Book of Fáṭimih, as Bahá'u'lláh stated the Hidden Words were the revealed Book of Fáṭimih from Shí’ah prophecy.

In His preface to the Hidden Words, Bahá'u'lláh states His purpose for revealing the Hidden Words was to reform the soul and conduct of humanity, and lead it to detachment from the material world, and enable believers to stand faithful to the Covenant.

Partial Inventory ID: BH00386

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 1: Baghdád 1853 - 1863, pages 71-75.

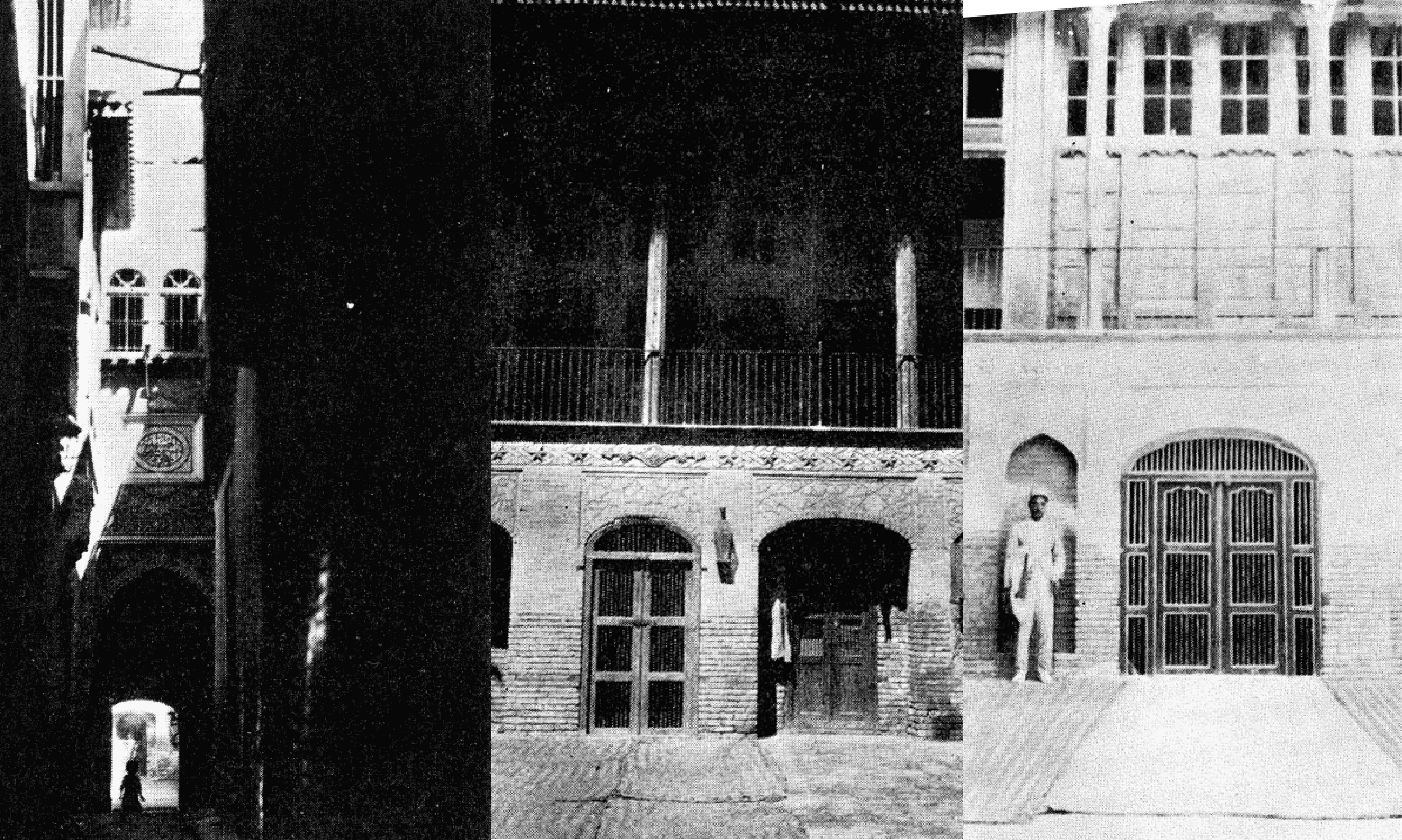

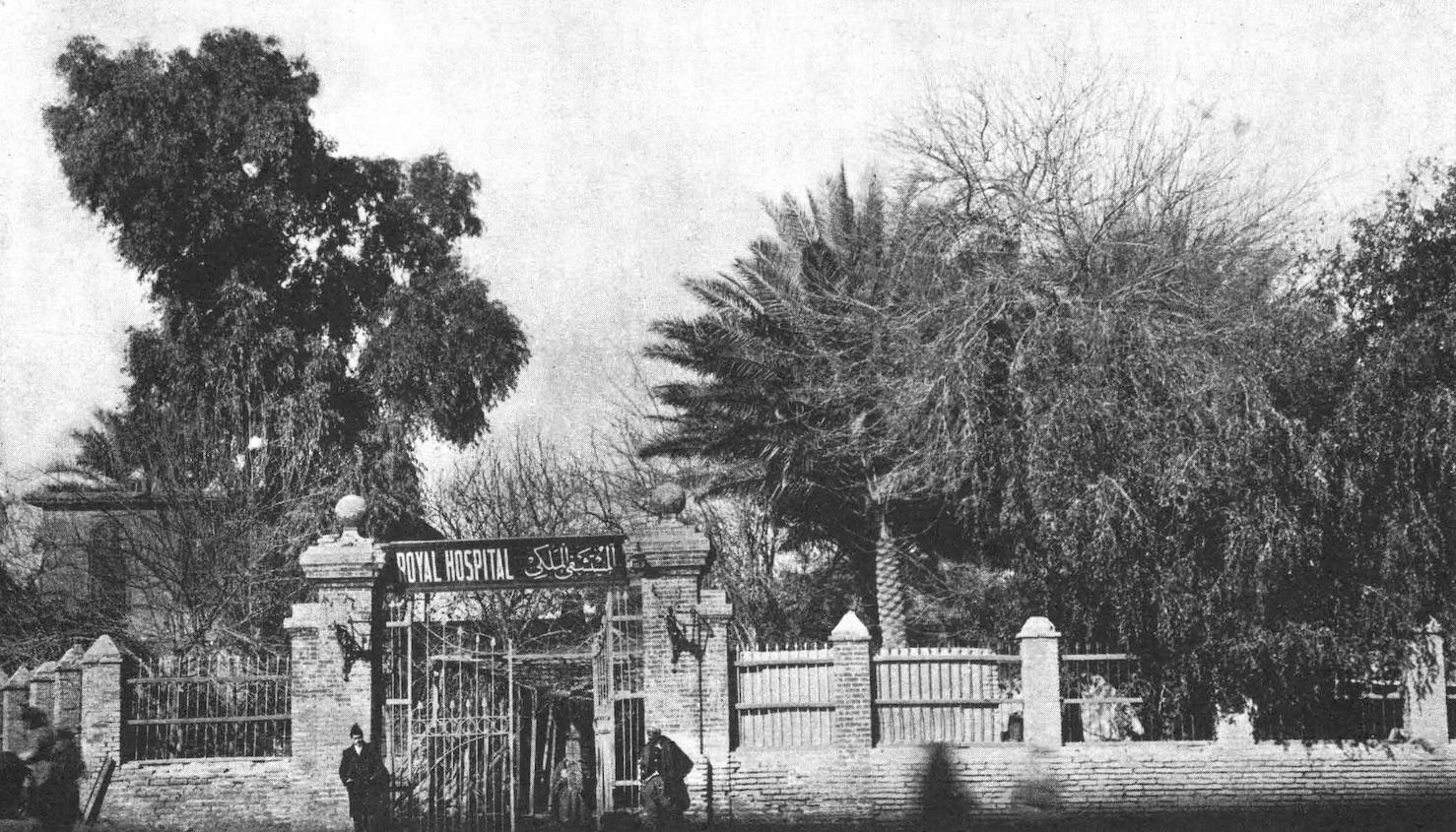

Three less well-known photos of the outside of the house of Bahá'u'lláh in Baghdád from the street. Photo on the left, view of the house from the alley/street. Source: The Bahá'í World Volume 5, via Baha'i Media. Photo in the center, of the balcony of the Most Great House facing the port on the River Tigris. Source: TheBahá'í World Volume 6via Baha'i Media. Photo on the right, source: Nabíl, The Dawn-Breakers, Epilogue, page 663.

Bahá'u'lláh would reside for the next seven years in the house of Sulaymán-i-Ghannám, which had originally been Mírzá Músá’s home. The Holy Family had moved in with Mírzá Músá while Bahá'u'lláh was in Sulaymáníyyih, and it soon became the focal center of the Bábí community.

Bahá'u'lláh bestowed on Sulaymán-i-Ghannám’s modest house, located on the banks of the Tigris River, the title of Bayt-i-A‘ẓam (the Most Great House). It was the destination for Bábí visitors and for all those who sought truth and enlightenment in Bahá'u'lláh’s presence, Turks, Persians, Arabs, and Kurds, from Ṣúfí, Sunní, Shí’ah, Christian, and Jewish backgrounds. The Most Great House also became a sanctuary for Persian Muslims fleeing Naṣiri'd-Dín Sháh government.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

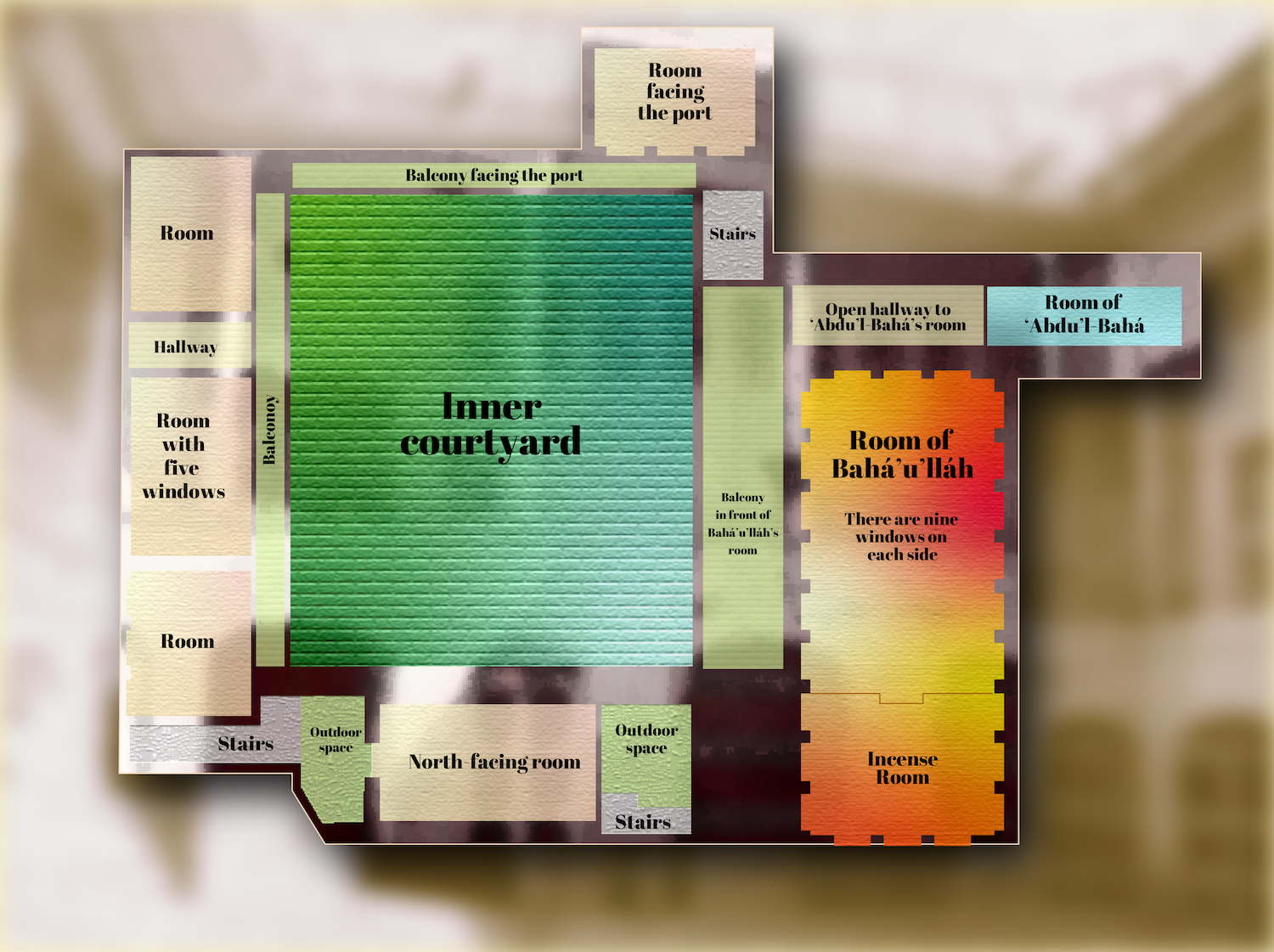

Floor plan of the second floor Most Great House in Baghdád, this only shows the bírúní side of the house. Standing in the courtyard facing the room of Bahá'u'lláh is the most common view of this house. Bahá'u'lláh had nine windows on the two long sides of His room, and 'Abdu'l-Bahá's room was very close to His. Original floor-plan in Persian from The Bahá'í World Volume 6. Floorplan in English from Reflections on the Bahá'í Writings: House of Bahá'u'lláh in Baghdád.

In Persian homes, the house was divided into two parts, usually built around a garden. The andarún, the women's side of the house, was the private part of the home, and off-limits to visitors. The bírúní was the men's side of the house, the public-facing side of a home, where messages were received, receptions held and guests entertained. The bírúní of the Most Great House was a neat and tidy low-roofed room, with a single couch made from palm branches on which Bahá'u'lláh would sit. The bírúní was constructed by a builder from Kashán by the name of Ustád Ismá'íl Banná.

In the morning, Bahá'u'lláh would have His morning tea with His family in the andarún, then leave for the bírúní, where He received visitors for about half an hour in the mornings, before heading to a coffee-house. When He returned from the coffee-house in the afternoons, Bahá'u'lláh would either go to the andarún or come to the bírúní, where believers gathered daily to spend time together until two hours after sunset, when they each regained their homes.

One of Bahá'u'lláh’s visitors, a prince from Káẓimayn declared to his friends he planned on building a duplicate of Bahá'u'lláh’s bírúní in his own home. When Bahá'u'lláh heard the story, He smiled and remarked: “He may well succeed in reproducing outwardly the exact counterpart of this low-roofed room made of mud and straw with its diminutive garden. What of his ability to open onto it the spiritual doors leading to the hidden worlds of God?”

The Most Great House brought disparate people together, and simply being in the house lifted people’s spirit and brightened their mood. Zaynu'l-'Ábidín Khán, the Fakhru'd-Dawlih, an exiled Persian nobleman, often said: “I cannot explain it, I do not know how it is, but whenever I feel gloomy and depressed, I have only to go to the house of Baha'u'llah to have my spirits uplifted.”

Ustád Muḥammad-'Alíy-i-Salmání, the Barber, My Memories of Bahá'u'lláh, pages 16-17.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 124.

This photograph, taken some seventy years later of Iráqí Kurds is offered as an illustration of their dress. The man in the center, in a long robe and clutching his dagger is Shaykh Maḥmud Barzánjí and was the King of Kurdistán from 1922-1924. He was born in Sulaymáníyyih twenty years after Bahá'u'lláh lived there. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

After visiting the always-hospitable Most Great House, and entering in the presence of Bahá'u'lláh, the Persian Bábís would return to Persia with countless written and oral testimonies of Bahá'u'lláh’s rising power and glory.

Among the most noteworthy visitors and disciples who associated with Bahá'u'lláh during His years in Baghdád were four of the Báb’s cousins, His maternal uncle Ḥájí Mírzá Siyyid Muḥammad, Princess Shams-i-Jihánl, the granddaughter of Fatḥ-‘Alí Sháh, Nabíl, the King and the Beloved of Martyrs, the father of Munírih Khánum, 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s future wife, and Zaynu’l-Muqarrabín, a highly esteemed mujtahid.

Many notables of Baghdád reverentially attended Bahá'u'lláh in His bírúní, including celebrated ‘ulamás, well-known calligraphers, famous Páshás and their Vizirs, the controller of customs, and government officials. All these regular and faithful visitors spread abroad the praises of Bahá'u'lláh and His fame grew to the point where new arrivals to Baghdád were soon drawn into the circle of Bahá'u'lláh’s acquaintances.

In the 19th century, oriental courts in cities like Ṭihrán, Baghdád, Constantinople were veritable snake pits. Malcontents and intrigue-lovers each had their own axe to grind, and, while Bahá'u'lláh was kind and welcoming to all, He did not tolerate scheming, at times refused to meet certain individuals, and harshly condemned brash and politically ambitious visitors who tried to gain His support or the backing of the Bábí community for their causes.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 124-125 and page 201,

Many of the people who encountered Bahá'u'lláh in Baghdád would have worked or been visiting the same streets and markets through which He walked. This almost contemporary 1876 engraving depicts a marketplace in Baghdád which could very well have looked the same twenty years earlier. Engraving by John Philip Newmain from The thrones and palaces of Babylon and Ninevah from sea to sea; a thousand miles on horseback. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Among the multitudes who sought out, accidentally met, or encountered Bahá'u'lláh during His seven years in Baghdád, many left anecdotes of their encounters with Him. Bystanders would recount their luck at seeing Him, watching Him walk through the streets of the city, or pace the banks of the Tigris. Muslims would remember watching Him pray in their mosque.

The beggars, elderly, indigent, and infirm would praise how Bahá'u'lláh helped, healed, supported, and comforted them. Visitors, princes and paupers, would recall entering His home to sit at His feet. Shopkeepers, artisans, and merchants told stories of serving on Him or supplying Him with His daily needs. Bábís would claim they had perceived the signs of His hidden glory.

Even Bahá'u'lláh’s adversaries would describe how the power of His utterance and the warmth of His love had confused and disarmed them.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Watercolor of an 19th century Ottoman coffee-house in Constantinople by Amedeo Preziosi. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

One feature of Bahá'u'lláh’s life in Baghdád that is unique in comparison to Ṭihrán, Constantinople, Adrianople and 'Akká, was His outgoing social habits. Baghdád was the only city where He lived during His ministry when He frequented coffeeshops daily, always accompanied by two or three Bábís.

Bahá'u'lláh would frequent coffee houses in the morning, for an hour and a half, and in the afternoon until sunset, returning to the Most Great House in between. When He was in a coffee-house, Bahá'u'lláh would, of course, drink coffee but mostly His aim was to teach, spread, and propagate the Bábí Faith, and so much of His time was spent speaking to people.

The coffee-houses were a central part of Bahá'u'lláh’s life because He never visited people in their homes. The notables, ulamás and magistrates of Baghdád who wished to enter His presence could either go to the bírúní of the Most Great House, or meet Bahá'u'lláh in a coffee-shop.

Bahá'u'lláh often frequented the coffee-house of Siyyid Ḥabíb the Arab, an imposing man with a white beard and the kad-khudá (borough-head) of Old Baghdád. Bahá'u'lláh would call Siyyid Ḥabíb over and offer him tea, and this became such a habit that Siyyid Ḥabíb considered any day when He was not in the presence of Bahá'u'lláh as a wasted day.

Bahá'u'lláh also visited 'Abdu'lláh’s coffee-house in Jassár, in east Baghdád. Whichever coffee-house Bahá'u'lláh patronized would inevitably become so crowded by the notables of Baghdád, that the owner prospered.

Some of these coffee-house owners became so attached to Bahá'u'lláh that His departure from Baghdád deeply affected them. A man named Ḥamd abandoned his coffee-house and left the city, and Siyyid Ḥabíb the Arab never again drank tea, or set foot in his coffee-house.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 151.

Ustád Muḥammad-'Alíy-i-Salmání, the Barber, My Memories of Bahá'u'lláh, pages 16-17,

Detail of the minaret of the Quamarí (Al Qamariyah) mosque near the Most Great House in Baghdád, on the banks of the River Tigris, where Bahá'u'lláh met the imám in the story below. Source: Google Maps.

One day, when Bahá'u'lláh visited the mosque of Quamarí, near the Most Great House, on the banks of the River Tigris. The imám, 'Abdu's-Salám Effendi, asked Bahá'u'lláh where He was from, and Bahá'u'lláh replied: "My dwelling-place is called 'Amá." An 'amá is a very specific type of cloud, thin, visible and disappearing at once, and in Persian mysticism, it is a term often used to describe Universal Reality. But the imám just asked: "What kind of city is it?"

Bahá'u'lláh described His fictional home as a perennially sunlight place, with a moon “wreathed in light,” bright-shining stars, flowing streams, fruitful trees, flowers always in bloom. Enchanted, the Imám said he had never heard of such a place, but would love to live in ‘Amá as well. He was a simple man, and had taken the story literally, but after this, he often came to seek Bahá'u'lláh’s presence. 'Abdu's-Salám Effendi was knowledgeable, and a good teacher, and Bahá'u'lláh arranged for him to discuss academic questions with 'Abdu'l-Bahá, then a teenager, on some mornings and afternoons.

One day, 'Abdu's-Salám Effendi remarked to Bahá'u'lláh that he had taught students for over thirty years, but often had to refer back to the books, and he had noticed that 'Abdu'l-Bahá, Bahá'u'lláh’s “accomplished child,” was capable of giving him explanations that had never occurred to him.

Bahá'u'lláh’s response to 'Abdu's-Salám Effendi is perhaps our first record of Him expounding on the powers of 'Abdu'l-Bahá and hinting at His station. He replied to the observant imám:

"The essence of the Most Great Branch is indicative of the essence of God. The Most Great Branch effortlessly comprehends scientific matters and perceives realities which others are incapable of fathoming; even as the Báb, Who, with only a few pages of practice, was able to produce such exquisite handwriting, and although He spent no more than a few days in school, prolific was the divine knowledge which flowed from His heart. In the same way, as soon as some aspect of knowledge comes to the attention of the Most Great Branch, He comprehends it to a degree that no scholar, however competent, can ever match."

'Alí -Akbar Furútan, Memories of Bahá'u'lláh, pages 24-26.

From the footnotes of the Rashḥ-i-'Amá (The Clouds From the Realm Above).

Many thanks to Adib Masumian for his kind help with the definition of 'amá.

1932 photograph of lemonade and bread street vendors in Baghdád, by the American Colony (Jerusalem). Source: Library of Congress.

All the people living in the neighborhood of the Most Great House received gifts from Bahá'u'lláh, particularly the poor, the disabled and the orphans. Whenever Bahá'u'lláh walked in His neighborhood and came upon someone needy, He showered His bounties upon them.

There was an old woman, around 80 years old who lived in a ruined house. Every day, around the time when Bahá'u'lláh would go to the coffee-houses, she would be waiting for Him by the road. And every day, Bahá'u'lláh would stop and enquire about her health and give her money, and she would kiss His hands. She wanted to kiss His face, but she was too short, so Bahá'u'lláh would bend down so she could reach Him. Speaking about this charming woman, Bahá'u'lláh would say: “She knows that I like her, that is why she likes Me.”

When Bahá'u'lláh left Baghdád, He made arrangements so that the old woman would receive a daily allowance until she died.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 151.

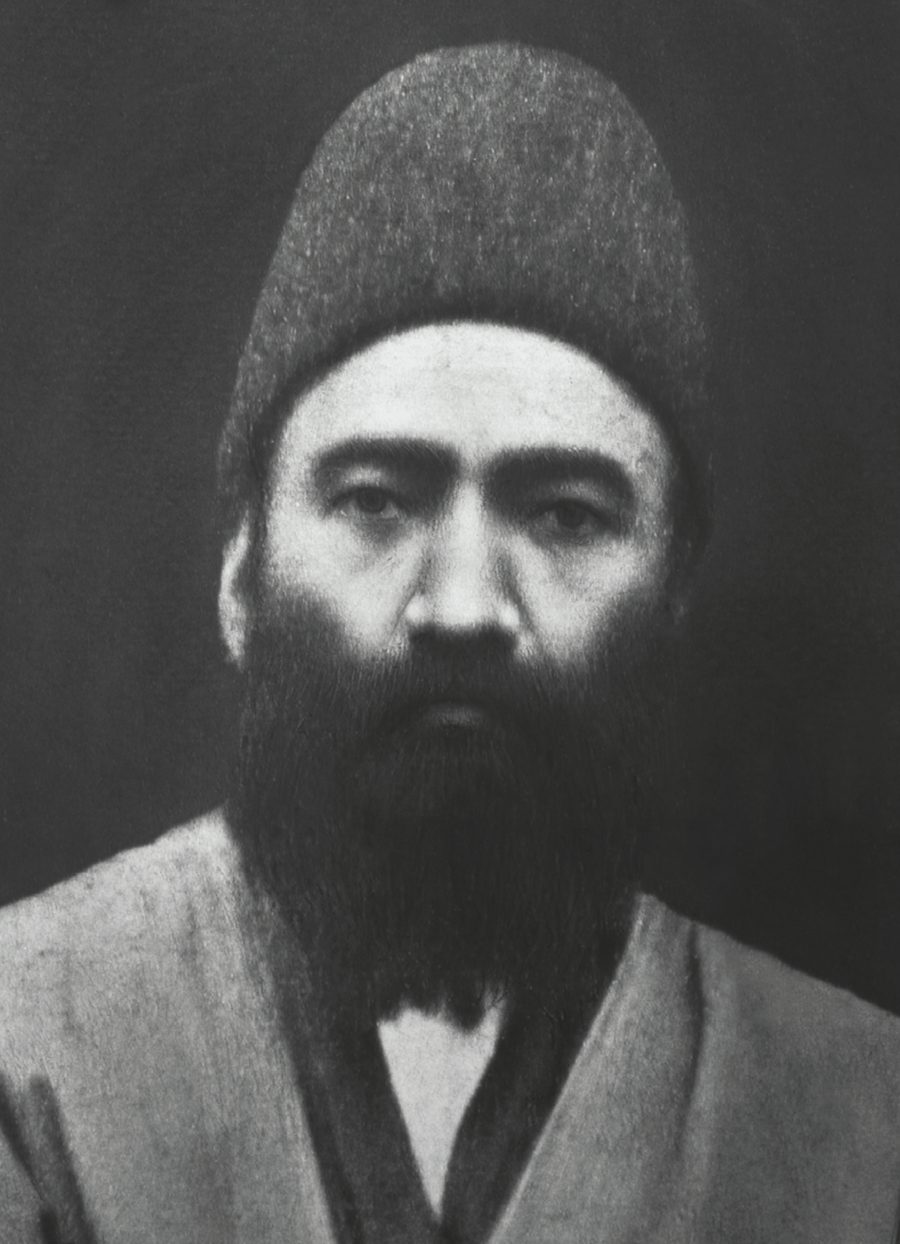

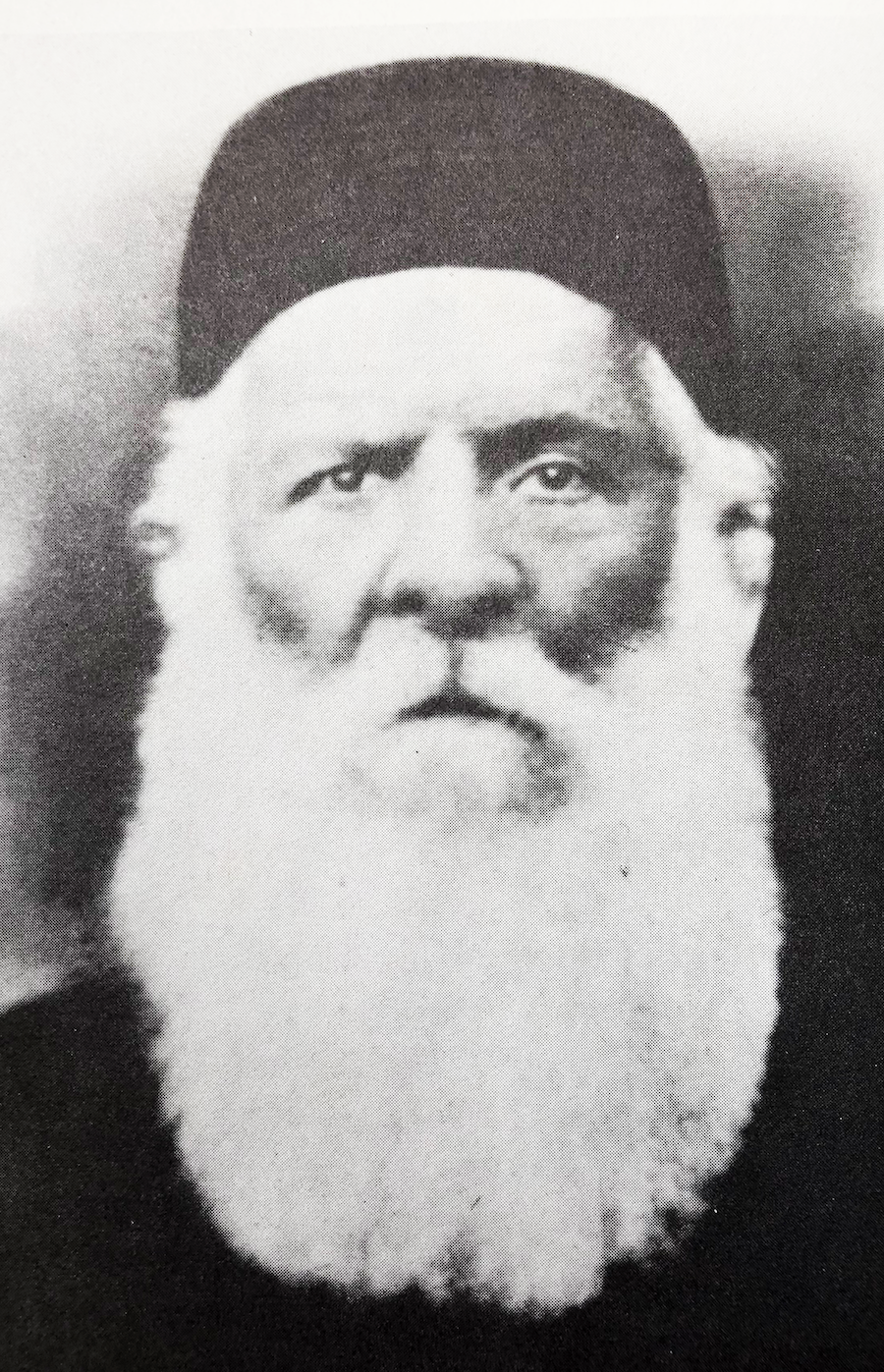

Shaykh Salmán, the tireless special messenger of Bahá'u'lláh. Source: Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 1: Baghdád 1853 - 1863, page 206.

Shaykh Salmán was Bahá'u'lláh’s courier to Persia for forty years. For four decades, he had no home. He walked the thousands of kilometers from wherever Bahá'u'lláh was, Baghdád, Constantinople, Adrianople, ‘Akká, Mazra’ih or Bahjí, to Persia, carrying petitions to Bahá'u'lláh and carrying Tablets from Bahá'u'lláh to the believers.

Shaykh Salmán became renowned among first the Bábís, then the Bahá'ís, and Bahá'u'lláh conferred upon him the title of “Messenger of the Merciful.” Shaykh Salmán was the personification of trustworthiness, so careful and diligent, that in 40 years, he never lost a Tablet, and every letter he carried reached its recipient. He was so patient under trials that Persians called him "the Bábí's Angel Gabriel."

Shaykh Salmán was blessed with incredible superhuman physical endurance. He lived in poverty and ate very simply, often a loaf of bread and raw onions, two items that do not spoil fast. Although he was illiterate, Bahá'u'lláh bestowed on him the knowledge of God, and through His bounty, Shaykh Salmán acquired a deep understanding of the Faith and a clear vision of the spiritual worlds.

Believers who wanted to attain the presence of Bahá'u'lláh had to ask for His permission and Bahá'u'lláh relied on Shaykh Salmán’s judgement in these matters. In fact, at one stage, Bahá'u'lláh delegated to Shaykh Salmán the authority to give permission for pilgrimage.

Bahá'u'lláh revealed many Tablets for Shaykh Salmán, often dealing with weighty and mystical subjects, such as the Madínatu't-Tawhíd, a Tablet in Arabic on the theme of the oneness of God, which Bahá'u'lláh had revealed at Shaykh Salmán’s request.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 1: Baghdád 1853 - 1863, pages 110-114.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Memorials of the Faithful.

1861 (contemporary to Bahá'u'lláh) engraving depicting the Shi'áh Al-Kadhimíya Mosque, located in the Kaẓimayn suburb of Baghdád, Iraq. It contains the tombs of the seventh and ninth Twelver Shi'áh Imáms, respectively Músá al-Káẓim and his grandson Muḥammad al-Jawad. Engraving from Le Tour du Monde, Volume 4 by Eugène Flandin. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

‘Abdu’r-Raḥmán, the Coppersmith was born in Káshán became a Bábí at a very young age in the very early days of the Faith. He dedicated his life to the Cause and left Káshán for Baghdád to meet Bahá'u'lláh. ‘Abdu’r-Raḥmán was blessed to spend time in Bahá'u'lláh’s company, as they set out together, many a time, and always on foot to the twin shrines in Kaẓimayn, some 7 kilometers (4.3 miles) from Old Baghdád.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Memorials of the Faithful.

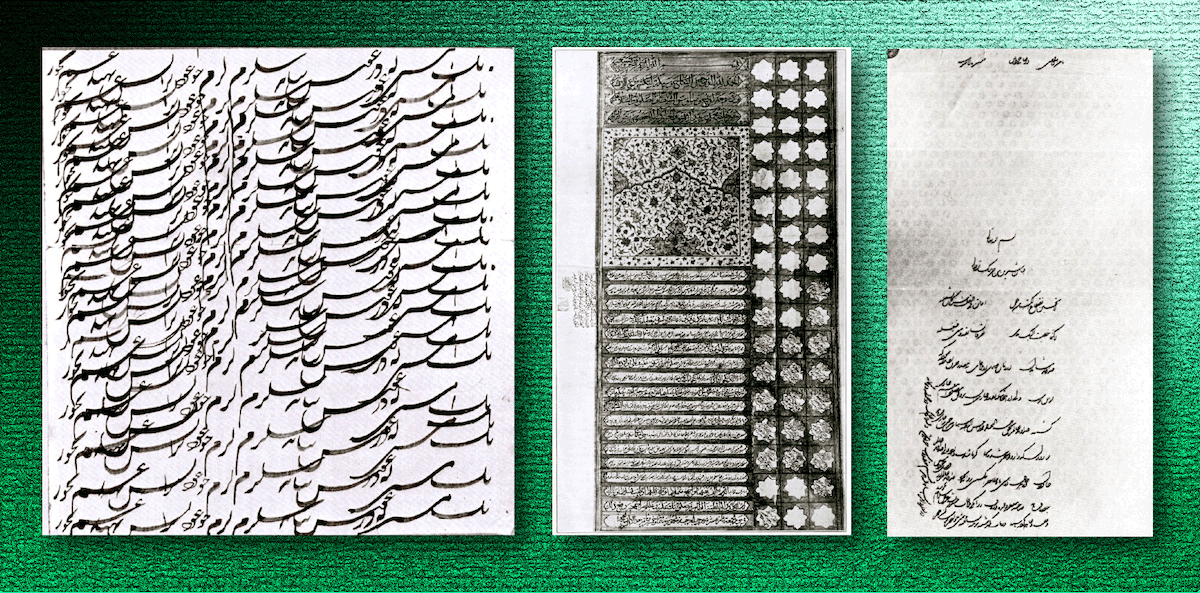

Three relics of the Báb closely associated with the two most important women in His life, His mother, Fáṭimih Khánum and His wife, Khadíjih Bagum. Left image: The Báb's childhood calligraphy exercises written before He was ten years old, ostensibly after His father had passed away, and His mother was a widow taking care of her only Son. Source: Bahá'í Sacred Relics. Center image: The Báb and Khadíjih Bagum's marriage certificate, dated 1842. Source: Bahá'í Sacred Relics. Right image: The first letter of the Báb to His wife, Khadíjih Bagum, sent from Búshihr before His departure as a pilgrim to Mecca. Source: Bahá'í Sacred Relics.

Twelve years after the Báb’s Declaration and six years after His martyrdom, His beloved mother with whom He had enjoyed an extraordinarily close bond with since childhood, still had not recognized His station as a Manifestation of God. After the loss of her only Son, the cruel and spiteful attitude of her hostile relatives was too much for her to bear, and she moved from Shíráz, to Najaf, around 145 kilometers (90 miles) from Baghdád, in 1854. In Najaf, the grief-stricken Fáṭimih Khánum lived a life of seclusion, meditation and prayer.

After Bahá'u'lláh had returned from Sulaymáníyyih in March 1856, Bahá'u'lláh sent two devoted Bábís, Hájí Siyyid Javad-i-Karbilá'í (see the photograph of the Baghdád Bábí community) and the wife of Hájí 'Abdu'l-Majíd-i-Shírází. They were both very well-acquainted with Fáṭimih Khánum from their time in Shíráz, and Bahá'u'lláh had asked them to instruct the mother of the Báb in the principles of the Bábí Faith and acquaint her with her Son’s station as a Manifestation of God.

The most insurmountable obstacle for Fáṭimih Khánum in acknowledging the Bábí Faith was Mírzá Yaḥyá's despicable desecration of the Báb’s honor, when he had married His second wife and given her to Siyyid Muḥammad. In a Tablet, Bahá'u'lláh stated Fáṭimih Khánum had asked "How could the people convinced of His claim to be the Qá'im, those who have given their allegiance to Him, dishonour His wife?" This situation caused Bahá'u'lláh to be “overtaken by sadness,” but eventually, towards the end of her life, and thanks entirely to Bahá'u'lláh’s efforts, Fáṭimih Khánum recognized the priceless Treasure that was her Son, accepted Him a Manifestation of God, embraced the truth of the Bábí Faith and died a believer, fully aware of the station of her Blessed Son. She had fulfilled His injunction addressed to her in the Qayyúm al-Asmá': “Recognize then the station of thy Son Who is none other than the mighty Word of God.”

Nabíl, The Dawn-Breakers, pages 190-193.

Baharieh Rouhani Ma'ani, Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees, pages 4-22.

Translation of the Tablet of Bahá'u'lláh approved for inclusion in Baharieh Rouhani Ma'ani, Leaves of the Twin Divine Trees, page 22.

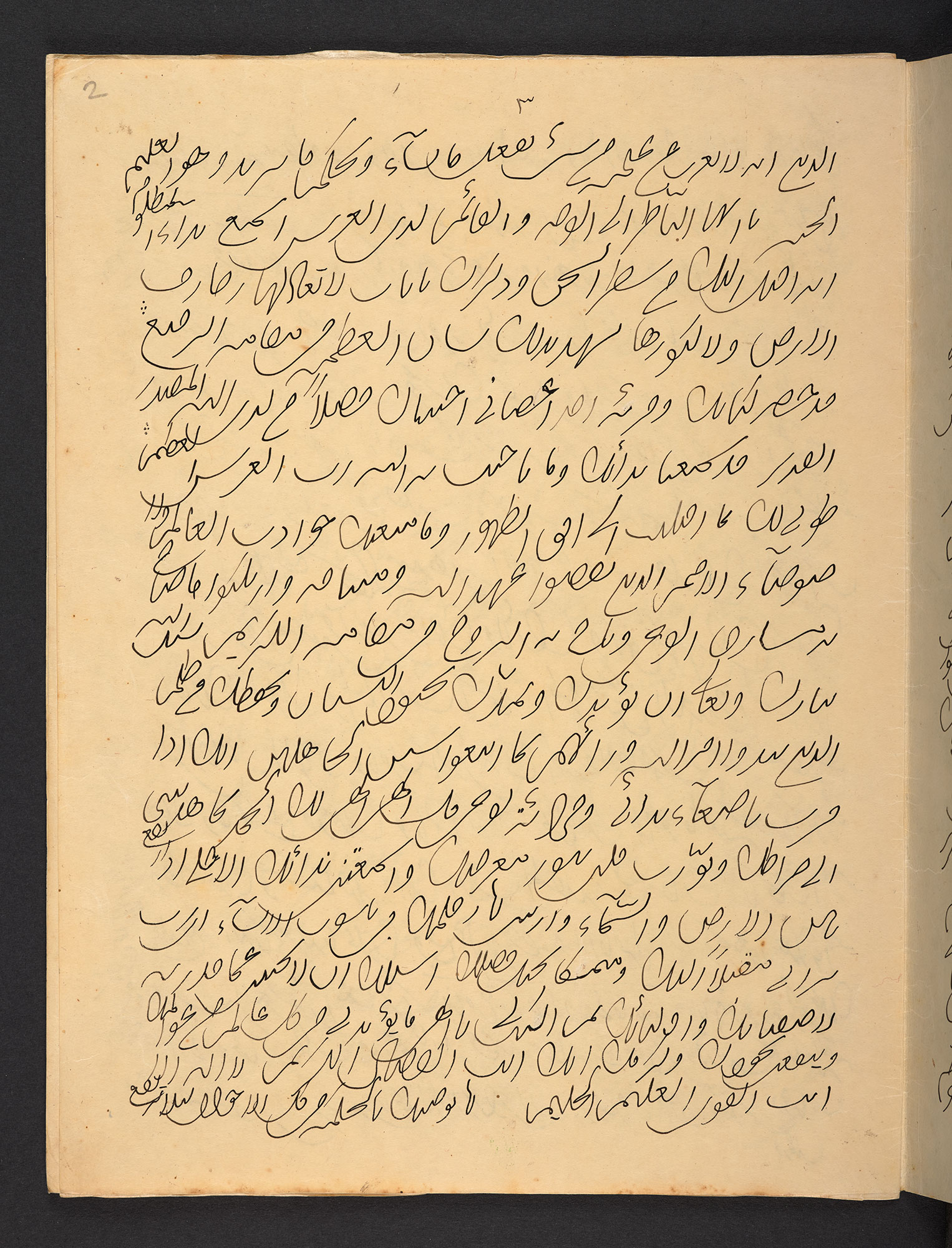

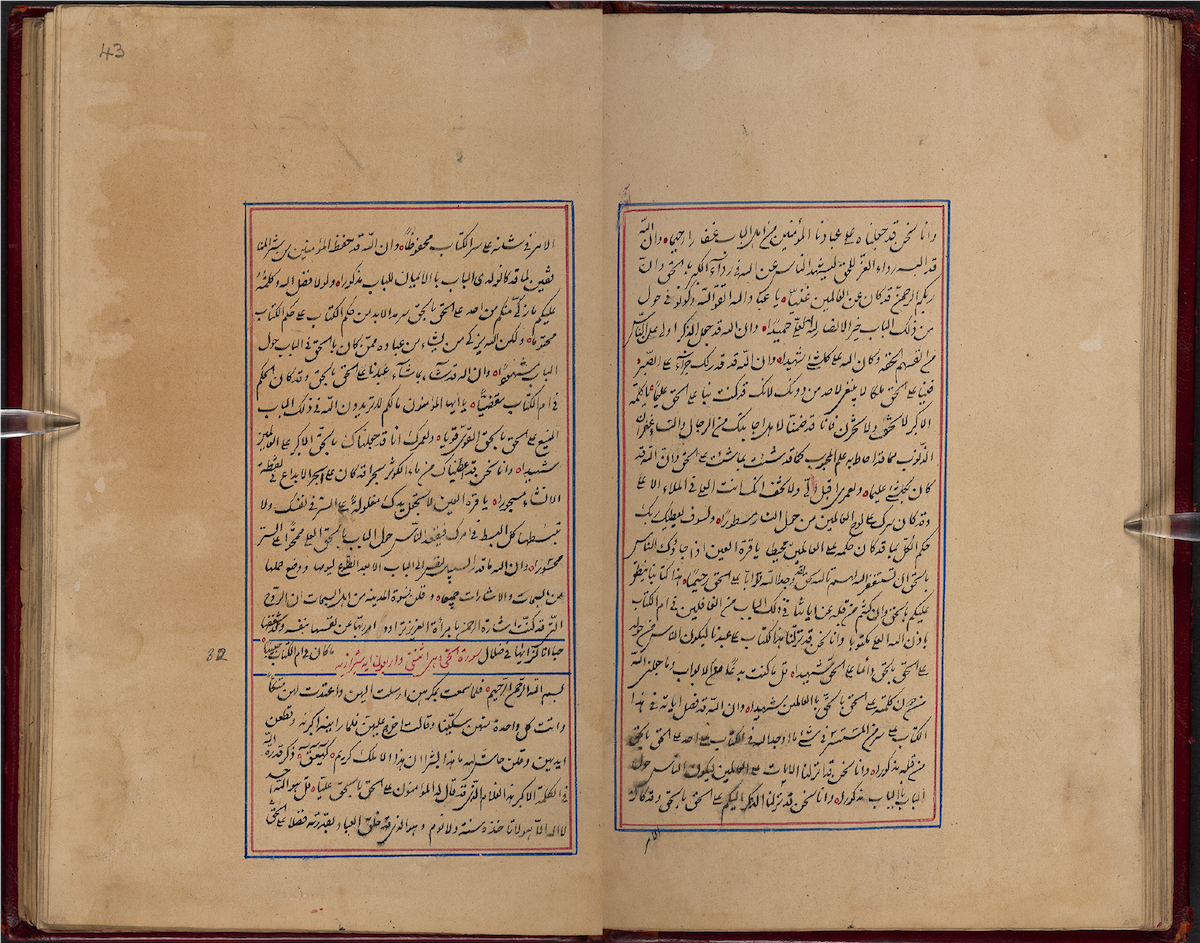

A draft Tablet revealed by Bahá'u'lláh and transcribed in "Revelation" script by Mírzá Áqá Ján, His amanuensis. Source: British Library.

The foundation and distinguishing elements of the spiritual transformation of the Bábí community of Baghdád can be found in Bahá'u'lláh’s prolific output of Revelation during those years. The intensity and extent of His Revelation was such that Bahá'u'lláh Himself described it as “a copious rain,” but its breadth was also astonishing. Bahá'u'lláh revealed epistles, exhortations, commentaries, apologies, dissertations, prophecies, prayers, odes, poems, and Tablets.

Bahá'u'lláh revealed so much that it could not all be transcribed, and Nabíl estimated that Bahá'u'lláh revealed the equivalent of the Qur’án each day of verses that were never taken down or copied. Most of Bahá'u'lláh’s Revelation during this time was dictated to Mírzá Áqá Ján or written down by Bahá'u'lláh, but the majority of His Revelation from Baghdád is lost to us forever.

Over seven years, Bahá'u'lláh ordered Mírzá Áqá Ján countless times to cast hundreds of thousands of verses into the River Tigris, comforting His reluctant amanuensis by telling him that “None is to be found at this time worthy to hear these melodies.”

Muḥammad Karím, a Bábí from Shíráz, had the bounty of being present while both the Báb and Bahá'u'lláh were Revealing verses. Muḥammad Karím affirmed that Bahá'u'lláh’s Revelation alone was His most powerful claim to greatness: “Had Bahá’u’lláh no other claim to greatness, this were sufficient, in the eyes of the world and its people, that He produced such verses as have streamed this day from His pen.”

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

SPIRITUAL TRANSFORMATION 1/3 © Violetta Zein.

Between 1856 and 1863, Bahá'u'lláh’s leadership of the Bábí community of Baghdád, gave them vision, strengthened its Faith, bolstered its confidence, expanded its horizons, and transformed its character.

In the span of just seven years, Bahá'u'lláh infused into the community and its members an even loftier set of principles and ethics than the lofty ones enshrined in the Bayán. Bahá’u’lláh held the believers to such a high standard that He declared: “It would be more acceptable in My sight for a person to harm one of My own sons or relatives rather than inflict injury upon any soul.”

So lofty were Bahá'u'lláh’s standards for integrity that one day, a Baghdád official came with a delicate situation. He confided to Bahá'u'lláh that he had not punished a criminal because the man claimed to be one of His disciples. Bahá'u'lláh made the situation perfectly clear for the official: only those who followed His example were His followers, and told him that even if Mírzá Músá, His full brother, was found guilty of an offence, “I would be pleased and appreciate your action were you to bind his hands and cast him into the river to drown, and refuse to consider the intercession of any one on his behalf.”

The Bábís in Bahá'u'lláh’s entourage were altered and uplifted in their understanding, and strove with all their might to sanctify and purify their souls, to conform with the will of God. They made pacts to admonish, correct, and punish each other when they strayed from the standard of Bahá'u'lláh. It was a re-created community.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

SPIRITUAL TRANSFORMATION 2/3 © Violetta Zein.

Bahá'u'lláh’s devout Kurd admirers soon started arriving in Baghdád with the words “Darvísh Muḥammad” and “house of Mírzá Músá the Bábí” on their lips. The religious leaders of Baghdád were simply astonished. They witnessed throngs of Kurdish ‘ulamás and Ṣúfís of historically rival orders flock to the Most Great House, and soon, they too began to seek out Bahá'u'lláh’s presence.

When Bahá'u'lláh answered all their questions to their complete satisfactions, these religious leaders of Baghdád became some of Bahá'u'lláh’s earliest admirers. Their unconditional recognition of Bahá'u'lláh’s majesty in turn piqued the curiosity and interest of poets, mystics and notables of Baghdád who would later sing Bahá'u'lláh’s praises far and wide.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

SPIRITUAL TRANSFORMATION 3/3 © Violetta Zein.

Aside from transforming its character, Bahá'u'lláh deepened, encouraged, and educated the Bábí community. He explained, interpreted, refreshed, and reaffirmed the fundamental teachings of the Báb that had been neglected, obscured, and misrepresented by Mírzá Yaḥyá and Siyyid Muḥammad. As a result, the spiritual life and health of the Bábí community and its members were profoundly revived.

Bahá'u'lláh gave the Bábís clear guidance. They were absolutely forbidden to engage in any political activity, to band in factions, or to hold secret meetings. They were defined by a strict principle of nonviolence and obedience to authority. Rebellion, retaliation, discord, dispute, and backbiting were banned. The foundational virtues of the new Bábí community of Baghdád were godliness, kindness, humility and piety, honesty and spirituality, chastity and faithfulness, justice, tolerance, friendliness, harmony, and unity.

Bahá'u'lláh encouraged the study of the arts and sciences, and created a code of ethics that included the virtues of self-sacrifice and detachment, patience, steadfastness, and resignation to the Will of God.

'Abdu'l-Bahá would later say that Bahá'u'lláh reformed, educated, and trained the Bábí community, managed its affairs and reversed its fortunes. Once Bahá'u'lláh had planted spiritual seeds in the hearts of the Bábís, their behavior completely changed, and they became known for their integrity and steadfastness, their pure motives, praiseworthy deeds and excellent conduct.

After years of turmoil, conflict, and shame, the Bábí community was imbued with peace and tranquility.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

1932 photograph of the copper bazaar in Baghdád, by the American Colony (Jerusalem). Source: Library of Congress.

Áqá Muḥammad, a Persian Kurd, came to Baghdád, opened a kebab shop, and became the leader of the bazaar. He disliked the Bábís and swayed the other Persian shopkeepers until they started abusing innocent Bábís publicly. When a confectioner hurled insults at a Bábí walking with Bahá'u'lláh, another Bábí gave him, and Áqá Muḥammad a sound beating. Áqá Muḥammad complained to Bahá'u'lláh, who assured him He would investigate the matter and punish the culprits, but the kebab shop owner filed a complaint with the Persian consulate anyway.

When the Vice-Consul heard from Bahá'u'lláh what they had done, he gave Áqá Muḥammad and the confectioner a dressing down and held them in custody. A few days later, both men’s families came crying to Bahá'u'lláh that they had no one to look after them, and Bahá'u'lláh asked the Vice-Consul to release the men. Later, when the Persian Consul returned from Karbilá and heard what had happened, he re-arrested Áqá Muḥammad and the confectioner, and again, their families went weeping to Bahá'u'lláh, who asked the Consul to release the men.

The Kurdish community of Baghdád was significant at the time, and its 2,000 members felt persecuted: one of their leaders and upstanding citizens had been arrested twice because of the Bábís. The Persian Kurds decided to exterminate the Bábí community, numbering about 30 or 40 believers.

That night, all the Bábí stood guard around the Most Great House to protect Bahá'u'lláh. As was His habit, Bahá'í left His house in the afternoon, went to Ṣáliḥ's coffee-house, east of the bridge, then headed to 'Abdu'lláh's to the west, which was frequented by Kurds and Persians. Outside 'Abdu'lláh's, Bahá'u'lláh told one of His companions: “We have been threatened with death. We have no fear, We are ready for them. Here is Our head.” Bahá'u'lláh spoke with such authority that those who heard Him were struck dumb. After spending three hours in the coffee-house, Bahá'u'lláh walked home, undisturbed, and there was no further verbal abuse in the marketplace. Everything had returned to normal.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 125-126.

'Umar Páshá (Michel Lattas) in 1854 during the Crimean war with his officers, four years before he encounters Bahá'u'lláh in Baghdád. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

'Umar Páshá was a high-ranking Austrian-Croatian military officer, whose birth name was Michel Lattas, and he was appointed Governor of Baghdád between 1858 and 1859. 'Umar Páshá was unkind and ruled with an iron fist, detaining masses of expatriated Persians in Karbilá and hauling them to the capital, forcing them to wear Ottoman military uniforms, and pay large sums of money to be released.

It was during his one-year governorship that Mírzá Riḍá (a relative of Siyyid Muḥammad-i-Iṣfahání) and Mírzá 'Alíy-i-Nayrízí plotted to injure Bahá'u'lláh. Without Bahá'u'lláh's permission, several Bábís set upon the two men in a bazaar, killing Mírzá Riḍá and severely injuring Mírzá 'Alíy-i-Nayrízí, who managed to drag himself to the Government House.

'Umar Páshá was so infuriated by the attack that he ordered cannons trained on the Most Great House. When he was told this was impossible, 'Umar Páshá ordered that Bahá'u'lláh come in person. A prominent Sunní cleric bluntly told the Governor that this was even more impossible: you did not summon Bahá'u'lláh in that way. His statement silenced 'Umar Páshá and he sent Mírzá 'Alíy-i-Nayrízí to Bahá'u'lláh, letting him fend for himself.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 127-128 and Addendum V, pages 482-483 for biographical information.

Two manuscript pages of the Qayyúmu'l-Asmá' (Maintainer of Names) also known as Tafsír Súriy-i-Yúṣuf (Commentary on the SúriyYúṣuf), by the Báb which Áqá Siyyid Ismá'íl-i-Zavári'í copied by hand and reviewed with Nabíl in the story below. Source: British Library.

Áqá Siyyid Ismá'íl-i-Zavári'í was a learned man and master of calligraphy. While he was in Baghdád in 1859/1860, he copied the Báb’s Qayyúmu'l-Asmá' by hand, then reviewed it with Nabíl at Bahá'u'lláh’s request, over a period of 18 days.

Áqá Siyyid Ismá'íl was so devoted to Bahá'u'lláh that every night around midnight, he would remove his turban and use it to sweep the street in front of the Most Great House. He would then gather up the sweepings in his cloak and toss them into the river. To Áqá Siyyid Ismá'íl, the earth and the dust on Bahá'u'lláh’s street had been blessed by His footsteps and should not be stepped on by anything unclean.

Once, Áqá Siyyid Ismá'íl had accompanied Bahá'u'lláh to a friend’s house, and laid out in front of them were plates of fruits and sweets. When Bahá'u'lláh gave the Siyyid some sweets, he asked for spiritual food, and Bahá'u'lláh told him: “That has been given to you.” From the moment Bahá'u'lláh spoke those words, Áqá Siyyid Ismá'íl felt his soul becoming aware of otherworldly thoughts.

One night, while they were in the bírúní, Bahá'u'lláh asked Áqá Siyyid Ismá'íl for a candle, and the Siyyid asked himself if Bahá'u'lláh’s true countenance as a Manifestation of God could be unveiled to a mere human. As soon as the thought had crossed his mind, Bahá'u'lláh called out to him: "Áqá Siyyid Ismá'íl, look!" When the Siyyid looked into Bahá'u'lláh’s face, he saw what no word could ever describe. It felt to him as if a hundred thousand seas, vast and sunlit, billowed upon Bahá'u'lláh’s Blessed Face.

After what he had witnessed, Áqá Siyyid Ismá'íl could not stay in the physical world, and he slit his throat, but when the believers brought Bahá'u'lláh the news, His reply was that he had not killed himself, but rather offered himself up as a sacrifice: “No one has killed him. Through seventy thousand veils of light We showed him the glory of God to an extent smaller than a needle’s eye; therefore, he could not more bear the burden of his life and has offered himself as a sacrifice.”

From that moment on, Áqá Siyyid Ismá'íl-i-Zavári'í became known as Dhabíḥ (the Sacrifice) and Bahá'u'lláh sang his praises, extolling him as “The Beloved and the Pride of the Martyrs.”

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 132-133.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 2: Adrianople 1863-1868, page 112.

Faizi, A Flame of Fire: The Story of the Tablet of Aḥmad Part II, Published in Bahá'í News number 433, April 1967.

1932 photograph of the Katah bridge of the River Tigris in Baghdád, taken by the American Colon (Jerusalem). Source: Library of Congress.

Ḥájí Ḥasan-i-Turk was not a learned man but he loved Bahá'u'lláh deeply. He had first met Bahá'u'lláh in Kirmánsháh, and had come to Baghdád several times. A very quiet man, he had begun writing a commentary on the Qayyúmu'l-Asmá,' but most of the time he never spoke. Someone commented on his silence to Bahá'u'lláh who simply observed his time to speak would come soon.

Suddenly, one day, Ḥájí Ḥasan had the worst proclamation idea in the entire world. He asked for Bahá'u'lláh’s permission to stand on a bridge and proclaim the Bábí Faith to all who could hear, with his dagger drawn. Bahá'u'lláh firmly but very kindly told him: “Ḥájí, put aside your dagger. The Faith of God has to be given with amity and love to receptive souls. It does not need daggers and swords.”

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 134.

Nabíl-i-Akbar, an erudite teacher of the Faith and Apostle of Bahá'u'lláh (not to be confused with Nabíl-i-'Aẓ'ám, the eminent historian and author of The Dawn-Breakers). Source: Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 1: Baghdád 1853 - 1863, page 175, from Bahaipedia.

Mullá Muḥammad-i-Qá'iní, later surnamed by Bahá'u'lláh Nabíl-i-Akbar, was widely acknowledged as one of the most learned men of Persia. Six years after his declaration, he traveled to Baghdád for the purpose of meeting Bahá'u'lláh. Bahá'u'lláh welcomed Nabíl-i-Akbar warmly and bestowed on him the honor of staying in the bírúní as His guest.

One afternoon, Nabíl saw a highly-respected Bábí named Mullá Ṣádiq kneel to Bahá'u'lláh as He entered the bírúní. Bahá'u'lláh reprimanded Mullá Ṣádiq for kneeling, but Nabíl-i-Akbar was confused as to why a man of Mullá Ṣádiq’s station would kneel in the first place. Mullá Ṣádiq was in a state of spiritual bliss and prayed that Nabíl-i-Akbar might one day see the truth.

After this incident, the more closely Nabíl-i-Akbar watched Bahá'u'lláh, the more he began feeling superior to Him. Nabíl-i-Akbar started behaving arrogantly, taking the seat of honor and speaking without letting others speak. One day, Bahá'u'lláh was serving tea to His guests when a question was asked. Nabíl-i-Akbar began answering, but Bahá'u'lláh kept making comments on the subject, and after a while, He took over. Bahá'u'lláh’s explanations were so profound, Nabíl-i-Akbar was overtaken by fear while he was spellbound. His eyes were opened.

In another meeting in Kázimayn, a few kilometers away, Bahá'u'lláh spoke about the mysteries and the origin of creation, and new worlds, filled with fresh meaning, opened up to Nabíl. Every word out of Bahá'u'lláh’s mouth was a gem to him, and anything else he had heard or studied in his life seemed like children’s play in comparison. Nabíl-i-Akbar could not contain his curiosity and wrote to Bahá'u'lláh asking Him about His station. 'Abdu'l-Bahá delivered the letter to His Father, and the next day Bahá'u'lláh responded with a Tablet that ended Nabíl-i-Akbar’s search for truth. He had recognized the station of Bahá'u'lláh.

Nabíl-i-Akbar wrote a second letter to Bahá'u'lláh humbly acknowledging Him as the Supreme Manifestation of God and begging Him to guide his steps in service. Bahá'u'lláh asked Nabíl-i-Akbar to go teach the Faith in Persia, which he did.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 1: Baghdád 1853 - 1863, pages 92-95.

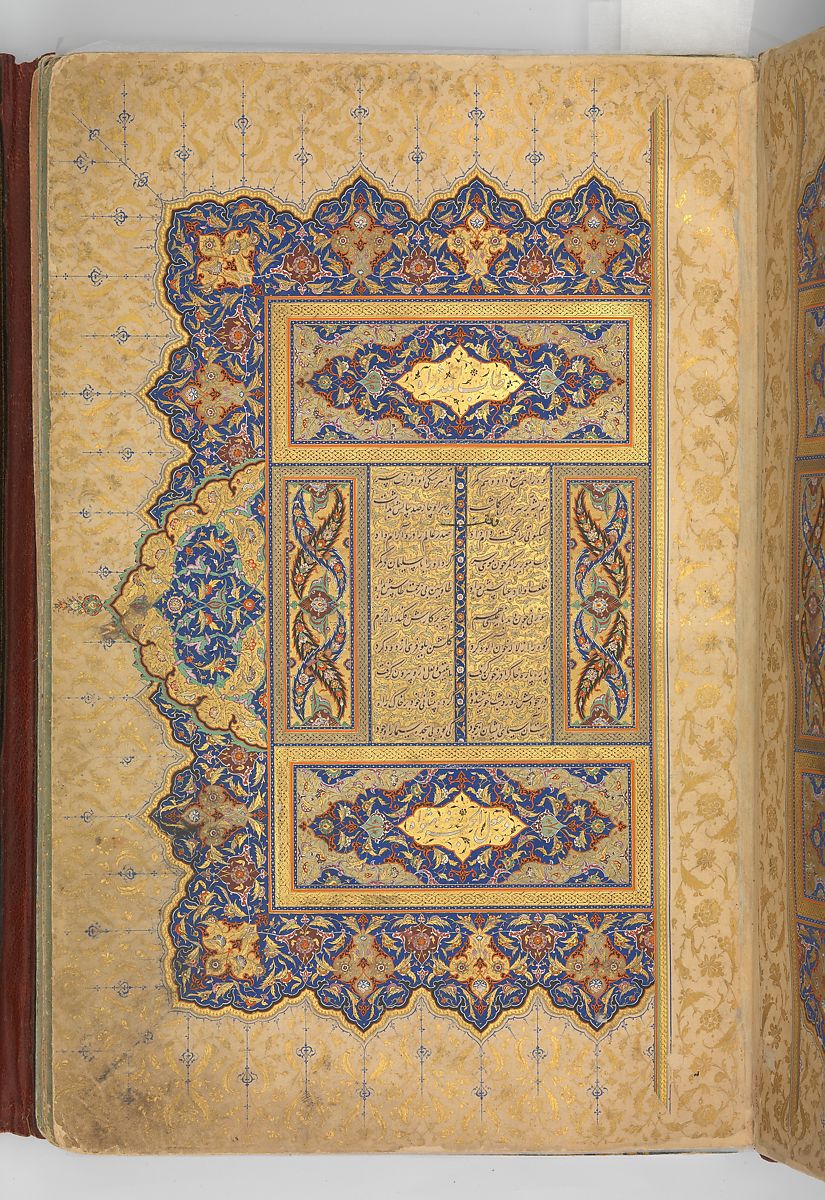

An illuminated page from the manuscript of The Conference of Birds, by Aṭṭár of Nishapúr, which describes the seven stages of a seeker's journey towards God. Calligrapher: Sulṭán 'Alí al-Mashhádí; Illuminator: Zayn al-'Ábidín al-Tabrízí; Text date: 1487; Illumination date: ca. 1600. Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Some years after returning from Kurdistán, Bahá'u'lláh revealed His greatest mystical treatise, called the Seven Valleys, in answer to questions posed to Him by Shaykh Muḥyi’d-Dín of Khániqayn.

In the Seven Valleys, Bahá'u'lláh describes the seven stages the true seeker’s soul hast to traverse from the physical worlds to the spiritual realms of nearness to God. The Ṣúfís were already familiar with the seven stages of this journey as described by Farídu'd-Dín-i-'Aṭṭár, also known as 'Aṭṭár of Nishapur, a twelfth-century Ṣúfí mystic, but Bahá'u'lláh clarifies the profound meaning and significance of each of the stages.

In order, these seven stages are The Valley of Search, The Valley of Love, The Valley of Knowledge, the Valley of Contentment, The Valley of Wonderment, and The Valley of True Poverty and Absolute Nothingness.

Partial Inventory ID: BH00047

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 1: Baghdád 1853 - 1863, pages 96-103.

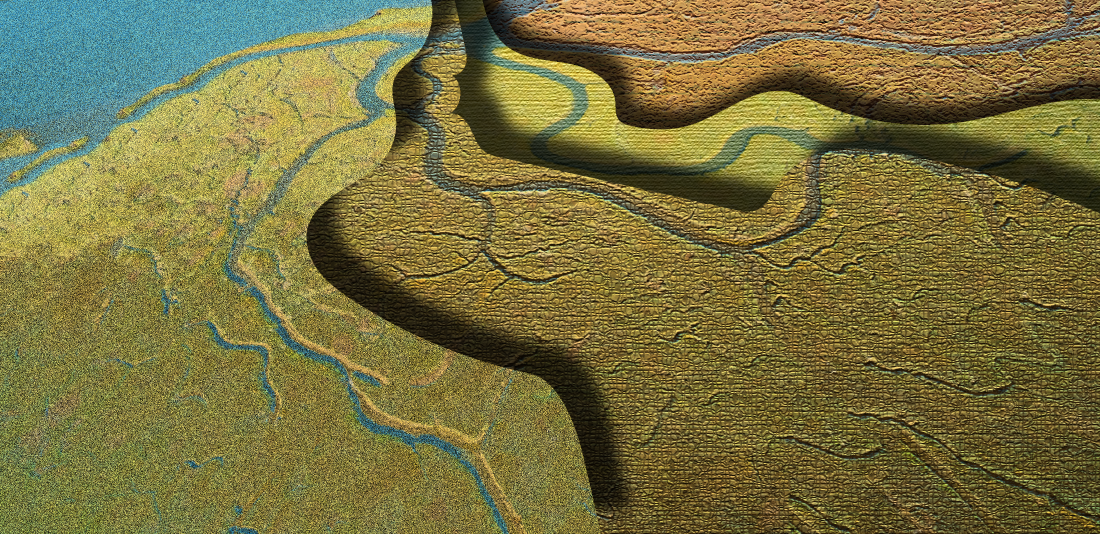

Abstract representation of the four paths to God expounded upon by Bahá'u'lláh in the Four Valleys, as four different estuaries leading into one river. © Violetta Zein.

The Four Valleys was revealed for Shaykh 'Abdu'r-Rahmán-i-Karkúkí, a learned Ṣúfí and leader of the Qádiríyyih Order. Shaykh 'Abdu'r-Rahmán was a devoted admirer of Bahá'u'lláh, having met Him in Sulaymáníyyih and sat at His feet, listening to Him discourse and he had corresponded with Bahá'u'lláh since that time.

A mystical work similar to the Seven Valleys in describing the journey of the spiritual traveler to his ultimate goal, the Four Valleys addresses interpretations of religious doctrines and scripture, speaks about mysticism, knowledge, and divine creation, exhorting men to education, goodly character and divine virtues.

Bahá'u'lláh's approach in the Four Valleys is somewhat different from the Seven Valleys, as He divides spiritual wayfarers into four categories: those who journey to God through strict obedience to religious laws, those who use logic and reason, those who journey purely through the love of God, and those who combine the three approaches of obedience, reason, and inspiration, with this last group considered the highest and purest form of mystic union.

Partial Inventory ID: BH00306

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 1: Baghdád 1853 - 1863, page 104.

Wikipedia: The Four Valleys.

1840 engraving of Hamadán by Eugène Flandin from Voyage en Perse avec Flandin. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Mullá Báqír had studied theology in Najaf where he became an ardent Bábí, and later met Bahá'u'lláh in Baghdád. He crossed paths with an angry Shaykhí who was virulently opposed to the Bábí Faith and hurled insults at the Báb and Bábís in front of Mullá Báqír, who attacked him with a curved knife in frustration. Mullá Báqír fled to Persia, but the Shaykhí found him in Hamadán and denounced him to the Governor. When they searched Mullá Báqír, they found a Tablet from Bahá'u'lláh reprimanding him for his reckless act.

After Mullá Báqír had served his sentence, he returned to Baghdád but Bahá'u'lláh did not receive him as He first had. The young man’s attack on the Shaykhí had very serious repercussions on the Bábí community of Baghdád, and Bahá'u'lláh instructed most of the Bábís to leave the city.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 135-136.

Sulṭán ‘Abdu’l-Majíd (1823 - 1861). Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The Persian government had repeatedly asked Sulṭán ‘Abdu’l-Majíd to remand Bahá'u'lláh into their custody or expel Him from the Ottoman Empire, but the Sulṭán had been so impressed by the favorable reports on Bahá'u'lláh’s integrity and behavior from successive Governors of Baghdád, that he consistently refused to do Naṣiri'd-Dín Sháh’s bidding.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Muṣṭafá Núrí Páshá, former Ottoman Governor of 'Iráq from 1860 - 1861, featured in the story below, he died in 1897, and was one of the oldest Páshás at the time of his passing. Image source: Wikimedia Commons.

Muṣṭafá Núrí Páshá was the Ottoman governor of ‘Iráq from 1860 to 1861. He was close to Sulṭán ‘Abdu’l-Majid and had a man named Riḍá Páshá dismissed from the Sulṭán’s court. When Riḍá Páshá regained influence, he returned the favor and had Muṣṭafá Núrí dismissed on fabricated charges and placed under house arrest, replacing him with a high-ranking military officer, Aḥmad Páshá, who was in his pocket.

Aḥmad Páshá surrounded Muṣṭafá Núrí Páshá’s home, cutting him off from outside contact. One of his friends, ‘Abdu’lláh Páshá of Sulaymáníyyih, turned to Bahá'u'lláh, who received him kindly and reassured him, saying: “Go and tell the Vali from Us to put his trust wholly in God, and repeat every day, nineteen times, these two verses: ‘He who puts his trust in God, God will suffice him’ and ‘He who fears God, God will send him relief.’” Bahá'u'lláh advised ‘Abdu’lláh Páshá to appeal directly to the new Governor, Aḥmad Páshá: “When he sees you appealing to him in the right way, he will grant you permission to visit your friend.”

Bahá'u'lláh’s wise counsel yielded positive results. Aḥmad Páshá was impressed with ‘Abdu’lláh Páshá’s faithfulness, and allowed him to visit Muṣṭafá Núrí Páshá, and he was able to convey Bahá'u'lláh’s message. A few days later, they received news of Sulṭán ‘Abdu’l-Majid’s death on 14 August 1861. Muṣṭafá Núrí Páshá was reinstated as Governor and his name cleared after a full investigation. Grateful to Bahá'u'lláh’s help, Muṣṭafá Núrí Páshá remained devoted to Him until he was replaced by Námiq Páshá.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 136-137.

In an homage to the story below about two wealthy Baghdád residents, a 1914 photograph of the home of wealthy Jewish homes in north Baghdád, on the banks of the Tigris. The round boat in the foreground is a quffah. Source: Library of Congress.

Bahá'u'lláh’s fame had grown exponentially in Baghdád. He was held in high esteem by notables of the city, and His integrity was widely known. Sometime before 1861, two very prominent and wealthy Persian citizens of Baghdád became so devoted to Bahá'u'lláh, that they not only became Bábís, but Bahá'u'lláh managed the fair and equitable settlement of their substantial estates after their death. These two episodes agitated the enemies of the Faith, jealous and angry with such high and public marks of honor bestowed on the leader of the Bábís.

Ḥájí Háshim-i-'Aṭṭár, a distinguished and wealthy Persian in Baghdád, organized a feast in Bahá'u'lláh’s honor that was so magnificent it was reported to both Naṣiri'd-Dín Sháh and Sulṭán ‘Abdu’l-Majíd. He passed away soon after the feast, but after his death, the provisions of his will were not respected and his widow and children were robbed of their inheritance. When Bahá'u'lláh was asked to intervene, he reprimanded the culprits, who set aside a share for Ḥájí Háshim’s family, and Bahá'u'lláh appointed a trustworthy custodian to manage their estate.

Ḥájí Mírzá Hádí, was a former minister for Fatḥ-‘Alí Sháh, who had fled to Baghdád and started a new life. He was a famously generous man, a gracious host, and a successful jeweler. Towards the end of his life, Ḥájí Mírzá Hádí became deeply devoted to Bahá'u'lláh, entering His presence with great humility. When he passed away, a corrupt judge and some crooked mujtahids tried to steal his inheritance, and the jeweler’s children came to Bahá'u'lláh for help. At first, Bahá'u'lláh refused to get involved, but at their pleading, He delegated 'Abdu'l-Bahá to resolve the divvying up of Ḥájí Mírzá Hádí’s inheritance, who resolved the thorny situation in a single day, as Bahá'u'lláh had instructed.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 140-141.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Memorials of the Faithful.

Note: The stories of the inheritance of these two wealthy Persians are conservatively four times the length of this section. To read them in full, which I heartily encourage you to do, please refer to the two references cited above.

THE DISHONORABLE CONSUL AND THE SCHEMING SHAYKH © Violetta Zein.

Bahá'u'lláh’s rising notoriety in Baghdád exacerbated the hatred and anger of His fanatical enemies. A conflagration was inevitable, and the spark was provided by two jealous and dark-hearted individuals, Shaykh ‘Abdu’l-Ḥusayn, a cunning and troublemaking disgraced Persian priest, and Mírzá Buzurg Khán-i-Qazvíní, the new Persian Consul, who arrived in Baghdád in July 1860.

Shaykh ‘Abdu’l-Ḥusayn was devoured by his jealousy for Bahá'u'lláh, and had an unfortunate talent for stirring mischief between the Arabs and Persians. So despicable was Shaykh ‘Abdu’l-Ḥusayn, that Bahá'u'lláh referred to him as the “scoundrel,” the “schemer,” the “wicked one,” who “drew the sword of his self against the face of God,” “in whose soul Satan hath whispered,” and “from whose impiety Satan flies,” the “depraved one,” “from whom originated and to whom will return all infidelity, cruelty and crime.”

Mírzá Buzurg Khán was a dishonorable and insincere man, a heavy drinker, who arrived in Baghdád determined to crush the Bábís. Bahá'u'lláh sent Mírzá Músá to visit the new Consul, but one day, when Mírzá Buzurg Khán boasted he could deal with Bahá'u'lláh however he pleased, Mírzá Músá laid out for him all of his intrigues and wicked actions, to which the Consul replied, insincerely: “The past is past. Should He [Bahá'u'lláh] consider me with favour in future, I shall be of service to Him.”

After Mírzá Buzurg Khán’s arrival, he soon allied himself with Shaykh ‘Abdu’l-Ḥusayn doing the Shaykh’s bidding during a nine-month concerted campaign of opposition to Bahá'u'lláh and the Bábís between 1860 and 1861.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 136-137, and 140.

NINE MONTHS: CIRCULATION OF DREAMS: "Shaykh ‘Abdu’l-Ḥusayn began, through the sedulous circulation of dreams which he first invented and then interpreted, to excite the passions of a superstitious and highly inflammable population." (Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By). © Violetta Zein.

The first thing Shaykh ‘Abdu’l-Ḥusayn and Mírzá Buzurg Khán tried was to get Bahá'u'lláh and the Bábís extradited back to Persia by grossly misrepresenting the truth, but the local authorities had great affection for Bahá'u'lláh and would not countenance their plan.

Shaykh ‘Abdu’l-Ḥusayn then began widely and diligently spreading interpretations of invented dreams regarding Bahá'u'lláh to a highly superstitious, gullible, and volatile population. In one dream, he was standing with the Sháh below verses of the Qur’án inscribed in Latin, an act of sacrilege perpetrated by the Bábís. In another fake dream, a Bábí caught up with him while they were riding horses and sprayed blood on him from a bottle, indicating he would be congratulated by the Sháh for his efforts in exterminating the Bábís but that he would also be murdered.

A man who was close to both the Shaykh and Bahá'u'lláh, asked Him to interpret the dreams, and Bahá'u'lláh said the first one indicated the Bábí Faith had the same origin as Islám but renewed, and as for the second dream, the Shaykh could rest assured that no Bábí would murder him and that he would not be called to Ṭihrán for honors.

Shaykh ‘Abdu’l-Ḥusayn had greatly underestimated the gullibility of the people of Baghdád. There was a general lack of response from people, and his strategy proved ineffective. Bahá'u'lláh sent note to the Shaykh to abandon the theatrics and seek a meeting with Him, but he simply continued plotting.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 141-142.

NINE MONTHS: AN ORDER TO KILL: "The consul-general had even gone so far as to hire a ruffian, a Turk, named Riḍá, for the sum of one hundred túmáns, provide him with a horse and with two pistols, and order him to seek out and kill Bahá’u’lláh." (Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By). © Violetta Zein.

Mírzá Buzurg Khán, tried to wield his influence and inciting the people of Baghdád to attack Bahá'u'lláh in public, in the hopes the Bábís would retaliate and give him leverage to extradite Bahá'u'lláh back to Persia. Bahá'u'lláh’s followers were worried for Him, but He ignored their pleadings and continued to walk the streets of Baghdád as He always had. At times, Bahá'u'lláh would approach those who had been ready to attack Him, encouraged them in their intentions and joked with them. Confused and dismayed, His opponents abandoned their scheme.

When his plan to incite an uprising against Bahá'u'lláh failed, Mírzá Buzurg Khán hired an assassin to kill Bahá'u'lláh, an Ottoman thug called Riḍa, paid him one hundred túmáns, equipped him with a horse and two pistols, and assured him he would be protected.

Riḍá the hitman made two unsuccessful attempts, though it is unclear which came first. Once, Riḍá ambushed Bahá'u'lláh, pistol in hand, but when Bahá'u'lláh approached him, he dropped his pistol. Bahá'u'lláh told Mírzá Músá: "Pick up his pistol and give it to him, and show him the way to his house; he seems to have lost his way."

For his second attempt, Riḍá tried to assassinate Bahá'u'lláh in the public bath, but when He confronted Him, he realized he couldn’t kill Him. While Bahá'u'lláh was standing up to these efforts to exterminate the Bábí Faith, Mírzá Yaḥyá, the nominee of the Báb was in Baṣrah, 450 kilometers (279 miles) away, living under a fake name and selling shoes and slippers.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 148.

NINE MONTHS: HOLY WAR: "Upon being informed of the purpose for which they had been summoned, [the concourse of shaykhs, mullás and mujtahids summoned by Shaykh ‘Abdu’l-Ḥusayn] determined to declare a holy war against the colony of exiles, and by launching a sudden and general assault on it to destroy the Faith at its heart." (Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By). © Violetta Zein.

Shaykh ‘Abdu’l-Ḥusayn was still focusing his energies on getting Bahá'u'lláh extradited back to Ṭihrán and imprisoned. To this end, Shaykh ‘Abdu’l-Ḥusayn embarked on a misinformation campaign, sending long, almost daily report to Naṣiri'd-Dín Sháh’s entourage. The Shaykh exaggerated Bahá'u'lláh’s prestige, painted a portrait of Him as a leader who had earned the allegiance of 10,000 troops of ‘Iráqí nomads ready to fight at a day’s notice, and accused Him of plotting to overthrow the Sháh.

Shaykh ‘Abdu’l-Ḥusayn had applied enough pressure on the authorities in Ṭihrán that he was granted a unilateral mandate urging the Persian ‘ulamás and officials to assist in any way he needed. He wasted no time in wielding his new authority and immediately convened a gathering in Káẓimayn. Eager to gain favor with the Sháh, shaykhs, mullás and mujtahids from Najaf and Karbilá promptly responded, and together decided to wage a holy war against the Bábí Faith and Bahá'u'lláh.

They were shocked when the leading mujtahid among them refused to pronounce the sentence. Shaykh Murtaḍáy-i-Anṣárí, was famous for his tolerance, his wisdom and his unwavering sense of justice, and claimed that he did not know enough about Bábí beliefs to pass the sentence, and had never witnessed Bábís behaving in ways contrary to the Qur’án. He ignored his colleagues’ rebukes, sent his regrets to Bahá'u'lláh for what had happened, expressed his devout wish for His protection, and promptly returned to Najaf.

'Abdu'l-Bahá called the kind mujtahid an “illustrious and erudite doctor, the noble and celebrated scholar, the seal of seekers after truth.” And Bahá'u'lláh would later praise Shaykh Murtaḍáy-i-Anṣárí, counting him among “those doctors who have indeed drunk of the cup of renunciation,” and “never interfered with Him.”

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

A 1890 Century photograph by Antoin Sevrugin depicting a gathering of Persian Mullás, offered as an illustration for the delegation of Persian divines requesting a miracle from Bahá'u'lláh in the story below. Source: The Smithsonian Museum, from the exhibition: Sailors and Daughters: Early Photography & the Indian Ocean, Photo used in accordance with the Smithsonian's Museum of African Art's copyright policy.

Shaykh Murtaḍáy-i-Anṣárí’s refusal to wage holy war against Bahá'u'lláh frustrated their plans, but the assembled Muslims refocused their hostility and delegated the learned and devout Ḥájí Mullá Ḥasan-i-‘Ammú, a man known for his wisdom and integrity, to submit questions to Bahá’u’lláh.

Ḥájí Mullá Ḥasan was completely satisfied with Bahá'u'lláh’s answers, and he wrote to Him confirming the ‘ulamás recognized the vastness of His knowledge but asked Him to perform a miracle as proof of the truth of His mission, in order to put the matter completely to rest.

Bahá’u’lláh replied they had no right to ask this of Him, as only God should test His creatures but stipulated that the ‘ulamás had to unanimously agree on the miracle they wished Him to perform, the group to come to a unanimous agreement on which miracle they wished Him to perform, “and write that, after the performance of this miracle they will no longer entertain doubts about Me, and that all will acknowledge and confess the truth of My Cause.” The ‘ulamás had to put down in writing that no doubt would remain for them after Bahá'u'lláh performed the requested miracle. The ‘ulamás’ messenger was so moved by Bahá'u'lláh’s courageous response that he kissed His knee before leaving to deliver the message.

Three days later, Bahá'u'lláh was informed that the ‘ulamás had not been able to agree on a miracle and decided to drop the matter, to which Bahá'u'lláh reportedly said: “We have through this all-satisfying, all-embracing message which We sent, revealed and vindicated the miracles of all the Prophets…” The event between the ‘ulamás and Bahá'u'lláh was widely reported, reaching even the Persian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Mírzá Sa‘íd Khán.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 144-145.

NINE MONTHS: MOB: "And when the next night, about four hours after sunset, the mourners appeared in the street, beating their breasts, Baha'u'llah requested His attendants to open the door and let them come in." (H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 149). © Violetta Zein.

During these tense nine months, Bahá'u'lláh’s followers were on high alert, patrolling outside the Most Great House night after night to protect Bahá'u'lláh and His family. One night, A friend of the Faith came to the house to warn them an attack was being mounted for the next night, with a mob disguised as mourners.

The Bábís began preparing for the attack, but Bahá'u'lláh told them there would be no need for any action. The following night, when the would-be mourners arrived, Bahá'u'lláh invited them into the Most Great House, saying “They are our guests.”

Bahá'u'lláh served His new friends rose-water sherbet and tea. They had come as His enemies and left as His friends, admitting that they had had a change of heart after experiencing Bahá'u'lláh’s kindness, and as they left, they shouted out: “May God curse your enemies!”

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 149.

An abstract interpretation of "incandescent as a candle," on a tiled background created out of a small portion of page illuminations from a 16th century folio entitled "Dancing Dervishes" from the Sháh Jahán. Source: The Met. © Violetta Zein.

In His Persian tablet Shikkar-Shikan-Shavand (With Greater Sweetness), revealed during this trying time, Bahá'u'lláh anticipates future dangers, with enemies poised for attack, in beautiful poetic language, while fearlessly declaring He will never waver, submit to threats or be daunted by turmoil, and that no calamity can quench His ardor in the path of God: “We are incandescent as a candle…We have burnt all the veils, We have lighted the fire of love…We shall not run away, We shall not endeavour to repel the stranger, We pray for calamity…What doth a soul celestial care if the physical frame is destroyed; indeed, this body is for it a prison…Until the time ordained cometh no one hath power over Us, and when the ordained time cometh it will find Our whole being longing for it…”

In Shikkar-Shikan-Shavand, Bahá'u'lláh alludes to Shaykh ‘Abdu’l-Ḥusayn and Mírzá Buzurg Khán's attempts to get Bahá'u'lláh and the Bábís extradited, and condemns their actions, foretelling their eventual failure. After this Tablet was revealed, Bahá'u'lláh ordered several copies sent to religious and secular authorities in Baghdád, and all those who received it were astounded by Bahá'u'lláh’s faith and courage.

Partial Inventory ID: BH00746

Provisional translation of Shikkar-Shikan-Shavand by Shahrokh Mondjazeb.

Steven Phelps, The Writings of Bahá'u'lláh in Routledge World: The World of the Bahá'í Faith, First Edition, Edited By Robert H. Stockman, page 56.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 149.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 1: Baghdád 1853 - 1863, page 147-150.

Bahaipedia: Shikkar-Shikan-Shavand.

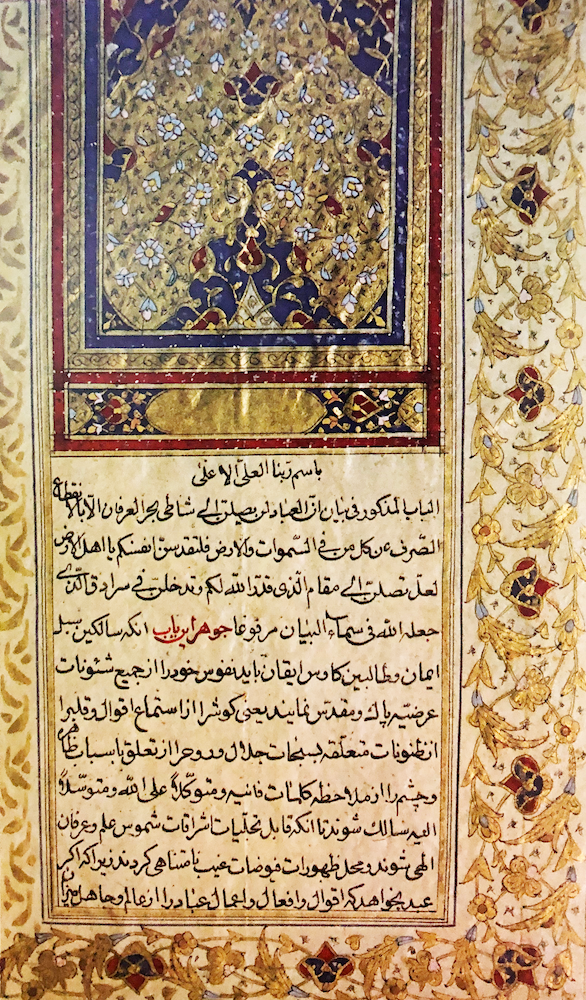

Opening page of the Kitáb-i-Íqán from a manuscript date 1871 in the handwriting of Áqá Mírzá Áqáy-i-Rikáb-Sáz, the first Bahá'í Martyr of Shíráz. Source: Frontispiece of H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory.

The Kitáb-i-Íqán (The Book of Certitude) is without a doubt the greatest emanation of Bahá'u'lláh’s pen in Baghdád, revealed in answer to four questions from the Báb’s maternal uncle, Ḥájí Mírzá Siyyid Muḥammad.

Ḥájí Mírzá Siyyid Muḥammad could not accept that his Nephew, the Báb, was the promised Qá'im and, while visiting Bahá'u'lláh in Baghdád, he begged Him to clarify the truth of the Báb’s message. He made a list of the questions that were puzzling him, and the traditions conflicting with his nephew's station, and brought them to Bahá'u'lláh.

The entirety of the 200-page Kitáb-i-Íqán was revealed in Persian in the space of 48 hours around mid-January 1861, fully dispelled every doubt in Ḥájí Mírzá Siyyid Muḥammad’s mind. In the early days of the Faith, the book was known as Risáliy-i-Khál (Epistle to the Uncle), but Bahá'u'lláh later designated it the Kitáb-i-Íqán.

In this matchless example of Persian prose, Bahá'u'lláh proclaims the existence of one unknowable, inaccessible God, the source of all Revelation, and expounds on progressive revelation and the oneness of all Divine Messengers, among many other themes. Bahá'u'lláh speaks about past Messengers of God, recounting their lives, sufferings, messages, and commonalities between them.

Bahá'u'lláh sheds light on obscure passages and terms in the New Testament, the Qur’án, and hadiths, outlines the prerequisites for seekers of truth, demonstrates the significance of the Báb’s Revelation and the heroism of His disciples. With the Kitáb-i-Íqán, Bahá'u'lláh unveiled the meaning of words which according to Daniel 12:4 had been shut and sealed until the time of the end: “But thou, O Daniel, shut up the words, and seal the book, even to the time of the end: many shall run to and fro, and knowledge shall be increased."

Partial Inventory ID: BH00002

*For the date of revelation of the Kitáb-i-Íqán, see Baha'i Calendar: This Month in History: January 1861: Baha’u’llah reveals theKitáb-i-Íqán.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 1: Baghdád 1853 - 1863, pages 153-174.

Prophecy from Daniel: The Bible, King James Version: Daniel 12:4.

Questions of Haji Mirza Siyyid Ali Muhammad occasioning the Revelation of the Kitáb-i-Íqán by Ḥájí Mírzá Siyyid ‘Alí Muḥammad, translated by Denis MacEoin. June 1997.

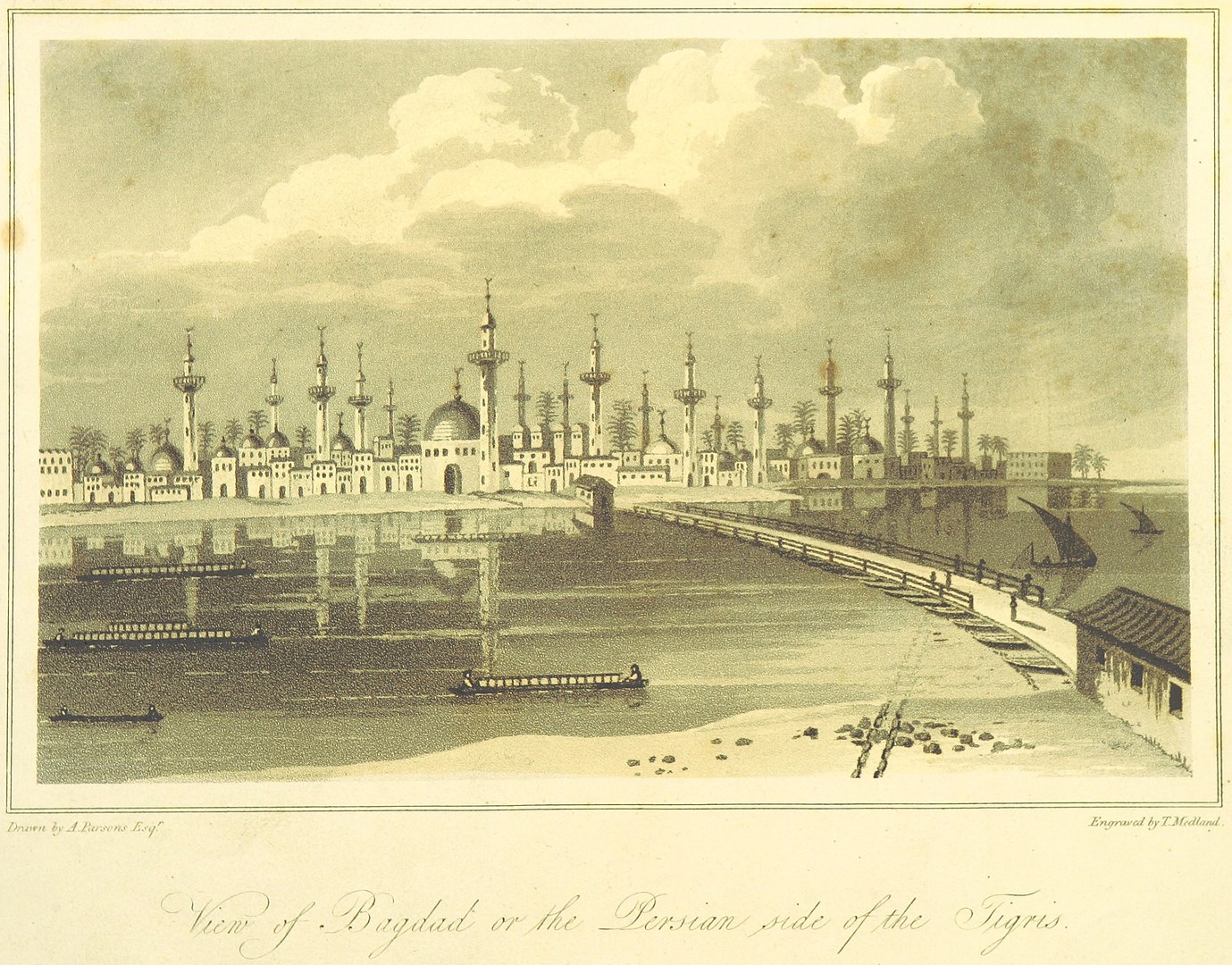

1808 engraving of Baghdád from the Persian side of the River Tigris, from Abraham Parsons' Travels in Asia and Africa, etc. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

It was during this tense period that Bahá'u'lláh decided His followers should apply for Ottoman citizenship in order to benefit from the protection of the Ottoman authorities. Námiq Páshá to Governor of Baghdád, was delighted by this decision and for three weeks, a believer who was competent in legal matters, took the Bábís two by two to the Government House until all the Persians were naturalized. When they learned of this, Bahá'u'lláh’s virulent enemies, Shaykh ‘Abdu’l-Ḥusayn and Mírzá Buzurg Khán, were dismayed.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 150.

Although this is not Mazra'iy-i-Vashshásh, this photograph of the Diyala River in Baghdad, 'Iráq, is offered as a mental inspiration. Bahá'u'lláh dearly loved and often frequented the countryside adjacent to Baghdad, and this photograph can help us imagine the scenery He may have laid eyes on. Photograph by Ali Al Obaidi. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Knowing His beloved Brother's love for nature, Mírzá Músá arranged to rent a small farm named Mazra'iy-i-Vashshásh, about three kilometers (two miles) south of Baghdád. The farm was irrigated with water from the River Tigris, and a shelter was built for Bahá'u'lláh's comfort. Bahá'u'lláh liked to stay in the beautiful surroundings of Mazra'iy-i-Vashshásh until sunset, and sometimes a large tent was pitched in the middle of the farm, which also a favorite retreat for the Holy Family. This was where the believers spent their last Naw-Rúz in Baghdád with Bahá'u'lláh, and where Bahá'u'lláh would reveal the Tablet of the Holy Mariner.

One day, a devoted believer by the name of Mírzá Maḥmud-i-Káshání heard Bahá'u'lláh speak to a number of believers in this garden about the exalted station of 'Abdu'l-Bahá, then a teenager between the ages of 12 and 19. 'Abdu'l-Bahá had already started being known as Áqá, the Master. In Persian, Áqá is equivalent to "Mister" in English when it used before the name of a person, like Áqá Ján, but used alone, it means "Master." That day, Bahá'u'lláh overheard someone referring to a believer as “the Áqá” and immediately set everyone straight with a commanding tone, saying: “Who is the Áqá? There is only one Áqá, and He is the Most Great Branch ['Abdu'l-Bahá].”

Even before His Declaration, before any of the countless Tablets Bahá'u'lláh would reveal about 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s station, and 28 years before He named Him the Center of the Covenant in the Kitáb-i-‘Ahd, Bahá'u'lláh had begun laying the foundations for the unanimous acknowledgement and understanding in the Bábí community of 'Abdu'l-Bahá’s peerless station.

'Alí -Akbar Furútan, Memories of Bahá'u'lláh, pages 23-24.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Covenant of Bahá'u'lláh, Chapter 9: The Relationship of Bahá'u'lláh and Abdu'l-Bahá.

In homage to a story below about Bahá'u'lláh's bakery, a 1932 photograph of a young girl selling bread in Baghdád some six decades later. Source: Library of Congress.

During these last years in Baghdád, Bahá'u'lláh often visited a farm outside the city called Mazra'iy-i-Vashshásh, and when He returned, Nabíl would wait for Him on the street of the Most Great House.

Bahá'u'lláh would often stop by the house of Nabúkí, on the opposite side of the street as the Most Great House, where Nabíl and several other Bábís lived, including a merchant from Shíráz and a carpenter. Nearby, a house Bahá'u'lláh also often visited was the house of Shatir-Riḍá, which housed Bahá'u'lláh's bakery. He had set up the bakery with a grinding mill Bahá'u'lláh had purchased, and the two brothers supplied all the Bábís of Baghdád with all the bread they needed, free of charge.

The father of the two bakers was the ninety-year-old Áqá Muḥammad-Ṣádiq who came from a town near Yazd. Many of his stories about the behavior of Muslim divines made Bahá'u'lláh smile, which made the old man very happy, as he would raise his hands in thanksgiving for the privilege of having brought joy to Bahá'u'lláh.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 150.

Ustád Muḥammad-'Alíy-i-Salmání, known as the Barber, from the frontispiece of his memoirs, My Memories of Bahá'u'lláh.

In a time when there was no running water in homes, the public bathhouse was an important part of everyone’s life. During Bahá'u'lláh’s last year in Baghdád, around 1862, Ustád Muḥammad-'Alíy-i-Salmání decided to serve as Bahá'u'lláh’s own private barber. He learned from the barber in the public bathhouse how Bahá'u'lláh liked His hair and beard styled. Bahá'u'lláh was particular about His beard, wearing it in a style worn by nobles of an earlier time. The various soaps used in the bathhouse were from Aleppo, a region in Syria famous for the most ancient soap in the world, known as ghar (meaning laurel) or Aleppo soap, and made from only three ingredients: pure olive oil, lye (a product made from wood ash), and laurel oil.

Ustád Muḥammad-'Alíy-i-Salmání, the Barber, My Memories of Bahá'u'lláh, pages 18-19.

Wikipedia: Aleppo soap.

Map showing the comparative distance between Shíráz, the birthplace of the Bábí Faith, Baghdád, where Bahá'u'lláh is living at the time of this story, and Díyárbakr, where the Faith of the Báb has reached. © Violetta Zein.

1900 photograph of Díyárbakr, taken by Oskar Mann. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

While Bahá'u'lláh lived in Baghdád, He received the well-known Ílkhání, ‘Alí-Qulí Khán, who, repenting from life of sin had devoted himself to Bahá'u'lláh. An eminent Bábí, Siyyid Javád-i-Ṭabáṭabá’í, had interceded on his behalf to Bahá'u'lláh, and Bahá'u'lláh had replied: “Because he has chosen you as intercessor, I will hide away his sins, and I will take steps to bring him comfort and peace of mind.”

The Ílkhání had been vastly rich but was now destitute and ruined, hounded by so many creditors that he didn’t dare set foot outside. Bahá'u'lláh directed him to ‘Umar Páshá, the Governor of Baghdád, to obtain a letter of recommendation for Constantinople.

When Ílkhání reached Díyárbakr, 640 kilometers (400 miles) northwest of Baghdád, he wrote a letter of introduction to Bahá'u'lláh for two Armenian merchants addressing the letter “To His Eminence Bahá’u’lláh, Leader of the Bábís.” The Armenian merchants presented their letter of introduction to Bahá'u'lláh, explaining to Him that the Ílkhání had taught them the Bábí Faith.

Later, when Bahá'u'lláh entered the andarúní, the family apartments, He cried out to His brother Mírzá Músá, smiling and triumphant: “Kalím, Kalím! The fame of the Cause of God has reached as far as Díyárbakr!”

‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Memorials of the Faithful.

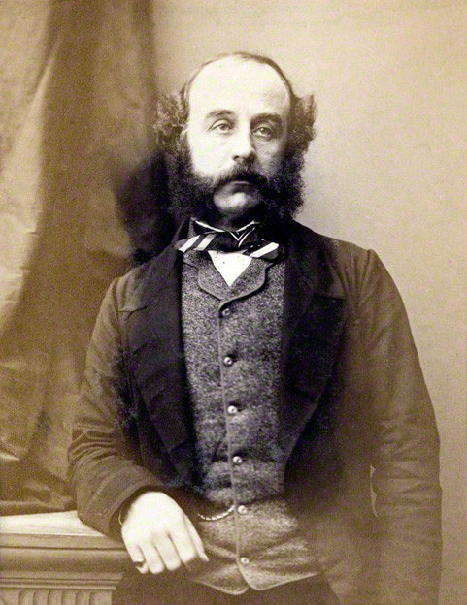

Portrait photograph of Arnold Borrowes Kemball by Camille Silvy taken 6 December 1860. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The British consul general in Baghdád, Colonel Sir Arnold Burrows Kemball, began a correspondence with Bahá'u'lláh and offered Him British citizenship and safe passage to India or any other destination He wished. He called on Bahá'u'lláh in person, perhaps the first Westerner ever to meet Bahá'u'lláh, and offered to convey a message to Queen Victoria, but Bahá'u'lláh declined all his offers and chose to remain in the Ottoman Empire.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Wikipedia: Arnold Borrowes Kemball.

Námiq-Páshá (1804 - 1892). Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Sometime in 1862-1863, Námiq-Páshá, the governor of Baghdád, called on Bahá'u'lláh personally to pay his respects. He had long been impressed with the marks of esteem and worship in which Bahá'u'lláh was held, and with Bahá'u'lláh’s conquest of the hearts and souls of His many visitors.

Námiq-Páshá considered Bahá'u'lláh one of the “Lights of the Age” and held Him in such high regard that, when Bahá'u'lláh delegated 'Abdu'l-Bahá and Mírzá Músá to visit the Governor, he gave them such an elaborate and ceremonious welcome that his Deputy-Governor stated no notable of Baghdád had ever been so well-received.

Not long after, Námiq-Páshá could not bring himself to carry the news of His second banishment to Bahá'u'lláh. He ignored five successive orders from the Ottoman Prime Minister ‘Alí Páshá, and delayed informing Bahá'u'lláh as long as possible.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Wikipedia: Mehmed Namık Pasha.

Abstract interpretation of the dark days ahead for Bahá'u'lláh, so sorrowful, they grieved the Manifestations of God in His dream. © Violetta Zein.

During His last years in Baghdád, Bahá'u'lláh began speaking about an upcoming period of turmoil and trials, and His sadness greatly affected those around Him. At this time, Bahá'u'lláh had had a spiritually-powerful premonitory dream about the Prophets and Messengers of God seated around Him, loudly weeping. When Bahá'u'lláh asked the Holy Ones the reason of Their lamentation, they replied: “We weep for Thee, O Most Great Mystery, O Tabernacle of Immortality!” So intensely did they weep, that Bahá'u'lláh wept with them, and the Concourse on High then addressed Him, saying: “…Erelong shalt Thou behold with Thine own eyes what no Prophet hath beheld.… Be patient, be patient,” and they kept addressing Bahá'u'lláh in this manner until dawn.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

Mírzá Sa'íd Khán-i-Anṣárí (1815/1816 - 1884), Mu'taminu'l Mulk. Educated as an 'ulamá, he became Foreign Minister after being the Amir Niẓam's private secretary. He was Foreign Minister for 20 years. Three years after his death, his son brought to the court one thousand unopened and unread letters from Persian and European diplomats. Bio from H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 482. Source of image: Wikimedia Commons. Ḥájí Mírzá Ḥusayn Khán (1827/1828 - 1881) Through his career he would earn the titles Mushíru'd-Dawlih and Sipahsálár-i-A'ẓam. Persian Consul in Bombay and Tiflis, he became a Minister in Constantinople, then Prime Minister, Minister of war. He was Governor of Khurásán when he died. Bio from H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, pages 472-473. Source of image: Wikimedia Commons.

After Shaykh ‘Abdu’l-Ḥusayn and Mírzá Buzurg Khán's nine-month campaign of opposition against Bahá'u'lláh in 1860 - 1861, Mírzá Buzurg Khán continued his activities from Persia, and the two sovereigns, Náṣiri’d-Dín Sháh and Sulṭán ‘Abdu’l-‘Azíz found themselves flooded with false and alarming reports misrepresenting Bahá'u'lláh as an active, hostile enemy, and constantly harassed to remove Him from Baghdád.

The Persian Foreign Minister in Baghdád, Mírzá Sa‘íd Khán and the Persian Ambassador in Constantinople, Mírzá Ḥusayn Khán started communicating about Bahá'u'lláh, and Mírzá Sa‘íd Khán poisoned the Ambassador’s mind, calling the Bábí Faith a “misguided and detestable sect,” deploring Bahá'u'lláh had been released from the Síyáh-Chál, and accusing Him of “secretly corrupting and misleading foolish persons and ignorant weaklings.”

Mírzá Sa‘íd Khán’s grounds for exiling Bahá'u'lláh were that He posed a direct threat to the security of Persia, His significant influence in Baghdád located too close to both Persia and the centers of Shí‘ah pilgrimage in ‘Iráq, and quoted a celebrated verse saying Bahá'u'lláh was like the ashes beneath the glow of the fire, wanting to burst into a blaze.

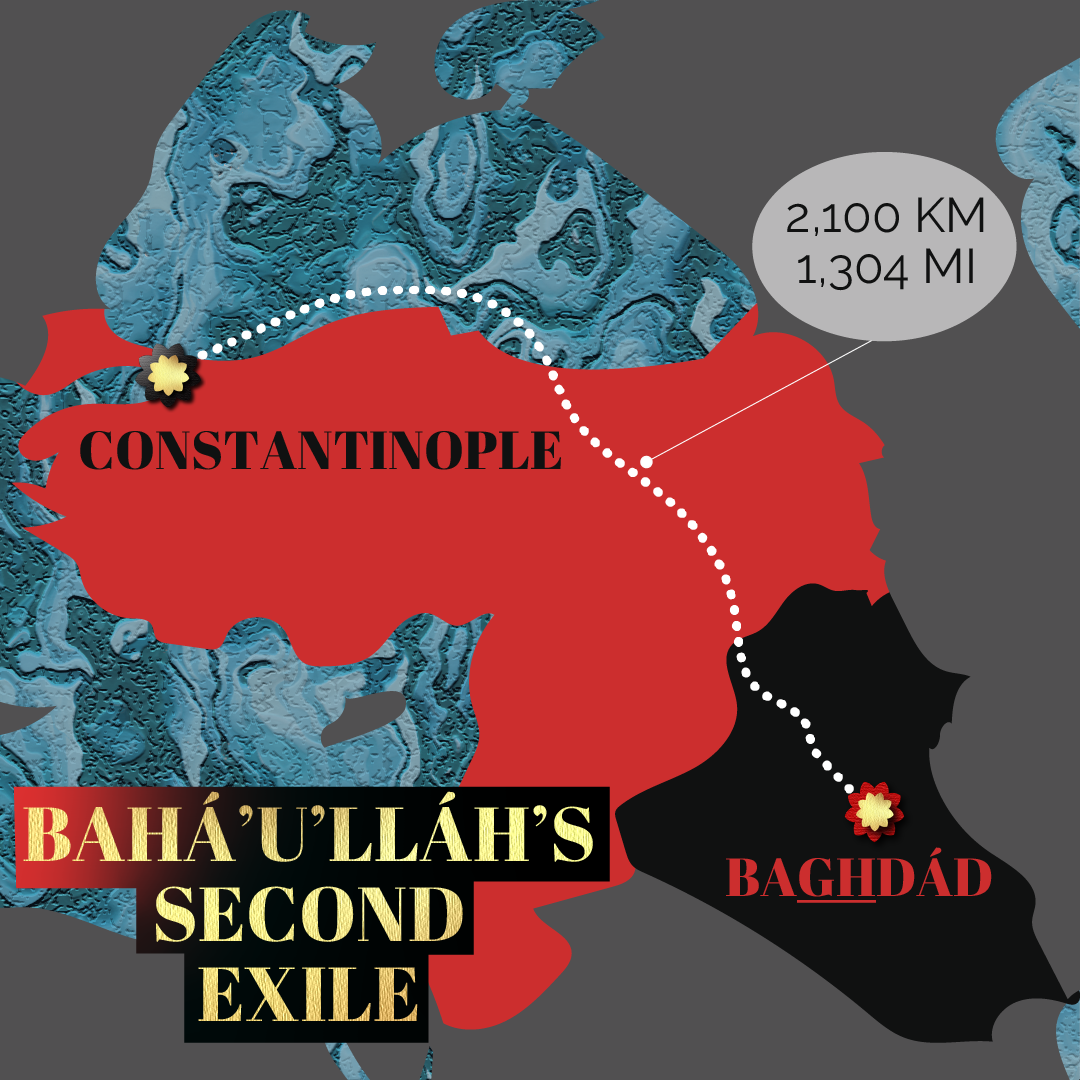

Mírzá Ḥusayn Khán was a very well connected man in Constantinople. He was a close friend of ‘Alí Páshá, the Grand Vizir of Sulṭán ‘Abdu’l-‘Azíz, and of the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Fu’ád Páshá, whom he had been asked to approach for this matter. In the end and after applying considerable pressure on the Ottoman ministers, Mírzá Ḥusayn Khán secured the sanction he wanted from Sulṭán ‘Abdu’l-‘Azíz: the exile of Bahá'u'lláh and His followers to Constantinople.

Shoghi Effendi, God Passes By.

As there are no photos of Mazra'iy-i-Vashshásh, here is an homage to the last Naw-Rúz of Bahá'u'lláh in the countryside of Baghdád with a contemporary view of Baghdád island and Tigris river by photographer Hassny Adel. It is easy to imagine the peaceful farm Bahá'u'lláh loved so much in the abundant greenery and farms of the "fertile crescent." Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Bahá'u'lláh celebrated His last Naw-Rúz with the Bábís in Baghdád in Mazra'iy-i-Vashshásh, the farm Mírzá Músá had rented for Him, which He loved visiting, especially in the beginning of spring, when the weather was mild, making it pleasant to enjoy the beautiful scenery of the countryside. Bahá'u'lláh and other Bábís all pitched their tents in the open countryside, and it was a happy occasion, followed by joyful days. Five days later, Bahá'u'lláh revealed the momentous Tablet of the Holy Mariner.

H.M. Balyuzi, Bahá'u'lláh: The King of Glory, page 154.

Adib Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh Volume 1: Baghdád 1853 - 1863, page 228.

An artistic interpretation of three partial verses from the Tablet of the Holy Mariner: "Bid thine ark of eternity appear before the Celestial Concourse…Launch it upon the ancient sea…Unmoor it, then, that it may sail upon the ocean of glory..” © Violetta Zein.